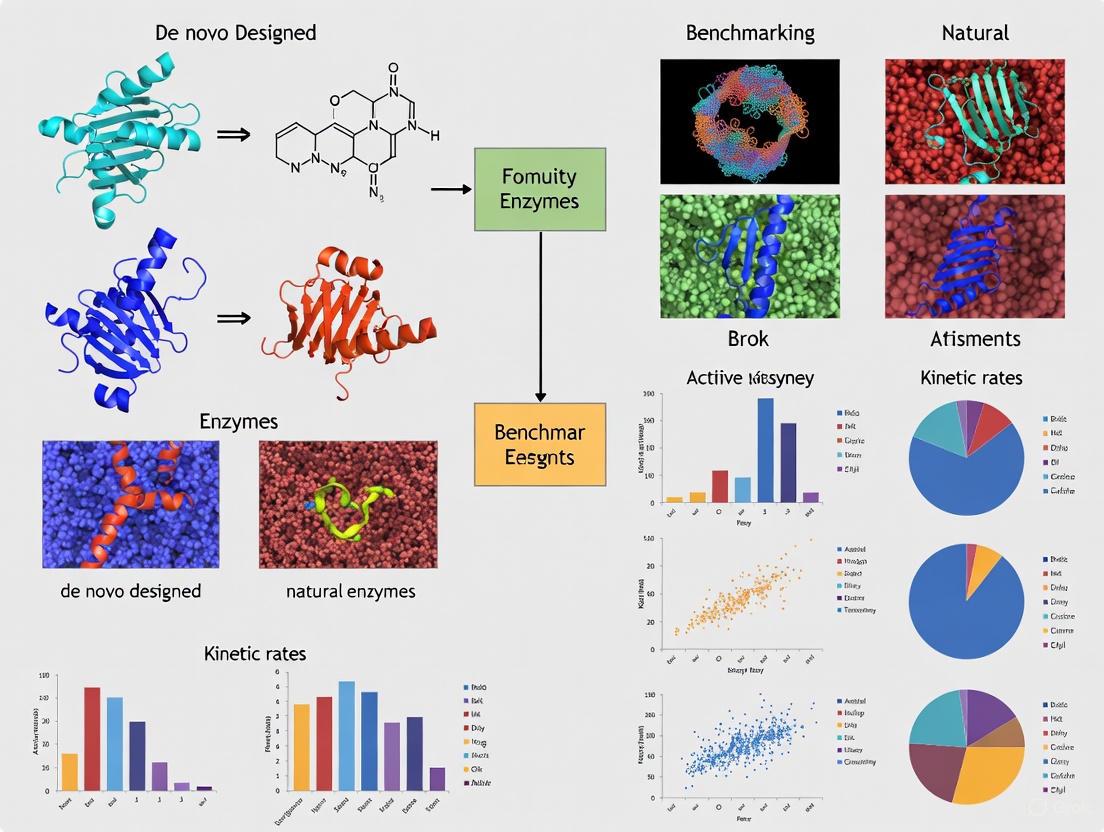

Benchmarking De Novo Designed Enzymes: Evaluating AI-Generated Proteins Against Natural Counterparts

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and critical challenges in benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against their natural counterparts.

Benchmarking De Novo Designed Enzymes: Evaluating AI-Generated Proteins Against Natural Counterparts

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current state and critical challenges in benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against their natural counterparts. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of enzyme design benchmarks, examines cutting-edge methodological frameworks and their real-world applications, details strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing design pipelines, and synthesizes the latest validation protocols and comparative performance metrics. By integrating insights from recent high-impact studies and emerging benchmarks, this review serves as a strategic guide for developing robust evaluation standards that can reliably predict the experimental success and functional efficacy of computationally designed enzymes, thereby accelerating their translation into biomedical and industrial applications.

The Imperative for Benchmarking in De Novo Enzyme Design

The grand challenge of computational protein engineering lies in developing models that can accurately characterize and generate protein sequences for arbitrary functions, a task complicated by the intricate relationship between a protein's amino acid sequence and its resulting biological activity [1]. Despite significant advancements, the field has been hampered by a triad of obstacles: a lack of standardized benchmarking opportunities, a scarcity of large, complex protein function datasets, and limited access to experimental validation for computationally designed proteins [1]. This comparison guide examines the current landscape of benchmarking frameworks and experimental methodologies that aim to translate protein sequence into predictable function, providing researchers with objective performance comparisons of emerging technologies against established alternatives.

The critical need for robust benchmarking is underscored by the rapid growth of the protein engineering market, projected to grow from $4.11 billion in 2024 to $8.33 billion by 2029, driven by demand for protein-based drugs and AI-driven design tools [2]. This expansion highlights the economic and therapeutic imperative to overcome persistent bottlenecks in de novo enzyme design, where designed enzymes often exhibit catalytic efficiencies several orders of magnitude below natural counterparts despite extensive computational optimization [3] [4].

Benchmarking Frameworks: Standardizing Evaluation

Established Benchmarking Platforms

Table 1: Key Protein Engineering Benchmarks and Their Characteristics

| Benchmark Name | Primary Focus | Key Metrics | Datasets Included | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Engineering Tournament [1] | Predictive & generative modeling | Biophysical property prediction, sequence design success | 6 multi-objective datasets (e.g., α-Amylase, Imine reductase) | Partner-provided (International Flavors and Fragrances) |

| PDFBench [5] [6] | Function-guided design | Plausibility, foldability, language alignment, novelty, diversity | SwissTest, MolinstTest (640K description-sequence pairs) | In silico validation only |

| FLIP Benchmark [7] | Fitness landscape prediction | Accuracy, calibration, coverage, uncertainty quantification | GB1, AAV, Meltome landscapes | Various published experiments |

The Protein Engineering Tournament represents a pioneering approach to benchmarking, structured as a fully remote competition with distinct predictive and generative rounds [1]. In the predictive round, teams develop models to predict biophysical properties from sequences, while the generative round challenges participants to design novel sequences that maximize specified properties, with experimental characterization provided through partnerships with industrial entities like International Flavors and Fragrances. This framework addresses critical gaps by providing never-before-seen datasets for predictive modeling and experimental validation for generative designs, creating a transparent platform for benchmarking protein modeling methods [1].

PDFBench, the first comprehensive benchmark for function-guided de novo protein design, introduces standardized evaluation across two key settings: description-guided design (using natural language functional descriptions) and keyword-guided design (using functional keywords) [5] [6]. Its comprehensive evaluation encompasses 16 metrics across six dimensions: plausibility, foldability, language alignment, similarity, novelty, and diversity, enabling more reliable comparisons between state-of-the-art models like ESM3, Chroma, and ProDVa [6].

Uncertainty Quantification in Protein Engineering

Robust uncertainty quantification (UQ) is crucial for protein engineering applications, particularly when guiding experimental efforts through Bayesian optimization or active learning. A comprehensive benchmark evaluating seven UQ methods—including Bayesian ridge regression, Gaussian processes, and multiple convolutional neural network-based approaches—revealed that no single method consistently outperforms others across all protein landscapes and domain shift regimes [7]. Performance is highly dependent on the specific landscape, task, and protein representation, with ensembles and evidential methods often showing advantages in certain scenarios but exhibiting significant variability across different train-test splits designed to mimic real-world data collection scenarios [7].

Experimental Platforms for Functional Validation

High-Throughput Experimental Characterization

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Functional Characterization of Designed Proteins

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Measured Properties | Throughput | Key Insights Generated |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biophysical Assays | Thermal shift assays, Circular dichroism | Thermostability, secondary structure | Medium | Structural integrity, folding properties |

| Kinetic Characterization | Enzyme activity assays, substrate profiling | kcat, KM, catalytic efficiency | Low | Catalytic proficiency, mechanism |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM | Atomic structure, active site geometry | Low | Structure-function relationships |

| Deep Mutational Scanning | Variant libraries, NGS | Functional landscapes for thousands of variants | High | Sequence-function relationships |

Advanced experimental platforms enable medium-to-high throughput characterization of designed proteins. For example, the Protein Engineering Tournament partnered with International Flavors and Fragrances to provide automated expression and characterization of generated protein sequences, measuring key biophysical properties including expression levels, specific activity, and thermostability across diverse enzyme classes including aminotransferases, α-amylases, and xylanases [1]. This approach demonstrates how industrial-academic partnerships can overcome the experimental bottleneck that typically hinders computational method development.

Recent investigations into distal mutations in designed Kemp eliminases illustrate the power of integrated experimental approaches. Combining enzyme kinetics, X-ray crystallography, and molecular dynamics simulations revealed that while active-site mutations create preorganized catalytic sites for efficient chemical transformation, distal mutations enhance catalysis by facilitating substrate binding and product release through tuning structural dynamics [4]. This nuanced understanding emerged from systematic comparisons of Core variants (active-site mutations) and Shell variants (distal mutations) across multiple designed enzyme lineages.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Benchmarking De Novo Enzymes

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Kemp elimination substrates (e.g., 5-nitrobenzisoxazole) | Reaction-specific chemical probes | Quantifying catalytic efficiency of de novo Kemp eliminases [3] [4] |

| Transition state analogues (e.g., 6-nitrobenzotriazole) | Structural and mechanistic probes | X-ray crystallography to assess active site organization [4] |

| TIM barrel protein scaffolds | Versatile structural frameworks | Common scaffold for computational designs of novel enzymes [3] |

| Directed evolution libraries | Diversity generation for enzyme optimization | Improving initial computational designs through iterative mutation and selection [3] |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database | Curated protein sequence and functional data | Training and benchmarking data for predictive models [5] |

Case Study: Learning from Natural Evolution

Statistical Energy Correlations in Kemp Eliminases

The benchmarking of de novo designed Kemp eliminases against natural enzyme principles provides profound insights into the sequence-function relationship. Research has demonstrated that the catalytic power of laboratory-evolved Kemp eliminases strongly correlates with the statistical energy (EMaxEnt) inferred from their natural homologous sequences using the maximum entropy model [3]. Surprisingly, EMaxEnt shows a significant positive correlation with catalytic power (Pearson correlation = 0.81 with log(kcat/KM)), indicating that directed evolution drives designed enzymes toward sequences that would be less probable in nature but enhance the target abiological reaction [3].

This relationship reveals a fundamental stability-activity trade-off in enzyme engineering. Directed evolution of Kemp eliminases tends to decrease stability (increasing EMaxEnt) while enhancing catalytic power, whereas single mutations in catalytic-active remote regions can enhance activity while decreasing EMaxEnt (improving stability) [3]. These findings connect the emergence of new enzymatic functions to the natural evolution of the scaffold used in the design, providing valuable guidance for computational enzyme design strategies.

Diagram Title: Optimization Pathway for De Novo Kemp Eliminases

RFdiffusion: A Generative Framework for De Novo Design

The RFdiffusion method represents a transformative advance in generative protein design, enabling creation of novel protein structures and functions beyond evolutionary constraints [8]. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks, RFdiffusion functions as a generative model of protein backbones that achieves outstanding performance across diverse design challenges including unconditional protein monomer design, protein binder design, symmetric oligomer design, and enzyme active site scaffolding [8].

Experimental characterization of hundreds of RFdiffusion-designed symmetric assemblies, metal-binding proteins, and protein binders confirmed the accuracy of this approach, with a cryo-EM structure of a designed binder in complex with influenza haemagglutinin nearly identical to the design model [8]. This demonstrates the remarkable capability of modern diffusion models to generate functional proteins from simple molecular specifications, potentially revolutionizing our approach to de novo protein design.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Benchmarking of Design Methods

Table 4: Performance Comparison of Protein Design Methods Across Benchmarks

| Method | Design Strategy | Therapeutic Relevance | Experimental Success Rate | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [8] | Structure-based diffusion | High (binder design demonstrated) | High (hundreds validated) | Exceptional structural accuracy, diverse applications | Requires subsequent sequence design (e.g., ProteinMPNN) |

| ESM3 [6] | Multimodal generative | Presumed high | Under characterization | Unified sequence-structure-function generation | Limited public access, training data not fully disclosed |

| Protein Engineering Tournament Winners [1] | Varied (ensemble, hybrid) | Varied across teams | Medium (depends on specific challenge) | Proven experimental validation | Method-specific performance variations |

| Chroma [6] | Diffusion with physics | Medium | Limited public data | Programmable design via composable conditioners | Less comprehensive evaluation |

The Protein Engineering Tournament revealed significant variation in method performance across different design challenges. In the pilot tournament, the Marks Lab won the zero-shot prediction track, while Exazyme and Nimbus shared first place in the supervised prediction track, with Nimbus achieving top combined performance across both tracks [1]. This outcome highlights how method performance is context-dependent, with different approaches excelling under different challenge parameters and dataset conditions.

RFdiffusion has demonstrated exceptional capabilities in de novo protein monomer generation, creating elaborate protein structures with little overall structural similarity to training set structures, indicating substantial generalization beyond the Protein Data Bank [8]. Designed proteins ranging from 200-600 residues exhibited high structural accuracy in both AlphaFold2 and ESMFold predictions, with experimental characterization confirming stable folding and designed secondary structure content [8].

Functional Efficiency Gaps: Designed vs Natural Enzymes

Despite these advances, a significant performance gap remains between de novo designed enzymes and natural counterparts. Original computational designs of Kemp eliminases typically exhibit modest catalytic efficiencies (kcat/KM ≤ 102 M-1 s-1), necessitating directed evolution to enhance activity by several orders of magnitude [4]. While directed evolution successfully improves catalytic efficiency, the best evolved Kemp eliminases still operate several orders of magnitude below the diffusion limit and below the efficiency of many natural enzymes [3].

This performance gap underscores the complexity of the sequence-function relationship and the current limitations in our ability to fully encode catalytic proficiency into initial designs. The integration of distal mutations identified through directed evolution provides critical enhancements to catalytic efficiency by facilitating aspects of the catalytic cycle beyond chemical transformation, including substrate binding and product release [4].

The field of protein engineering is rapidly evolving toward integrated computational-experimental workflows that leverage advanced benchmarking frameworks like the Protein Engineering Tournament and PDFBench. Future progress will likely depend on closing the loop between computational design and experimental characterization, enabling iterative model improvement through carefully curated experimental data [1] [9].

The emerging capability to design functional proteins de novo using frameworks like RFdiffusion [8] suggests a future where protein engineers can more readily create custom enzymes and therapeutics tailored to specific applications. However, robust benchmarking against natural counterparts remains essential to accurately gauge progress and identify the most promising approaches [10] [5].

As the field advances, the integration of AI-driven protein design with high-throughput experimental validation and multi-omics profiling will likely accelerate progress, potentially enabling the development of a modular toolkit for synthetic biology that ranges from de novo functional protein modules to fully synthetic cellular systems [9]. Through continued refinement of benchmarking standards and experimental methodologies, the grand challenge of moving predictively from sequence to function in protein engineering appears increasingly within reach.

Diagram Title: Protein Engineering Benchmarking Cycle

The field of de novo enzyme design is advancing rapidly, with artificial intelligence (AI) now enabling the creation of proteins with new shapes and molecular functions from scratch, without starting from natural proteins [11]. However, as these methods transition from producing new structures to achieving complex molecular functions, a critical challenge emerges: the lack of standardized evaluation frameworks. This benchmarking gap makes it difficult to objectively compare de novo designed enzymes against their natural counterparts, assess true progress, and reliably predict experimental success. Current evaluation practices are fragmented, with researchers often relying on inconsistent metrics, contaminated datasets, and methodologies that fail to capture the nuanced functional requirements of enzymatic activity [12] [13] [14]. This article analyzes the current limitations in benchmarking for computational enzyme design and provides a framework for standardized evaluation that can yield more meaningful, reproducible, and clinically relevant comparisons.

The Current State: Systemic Flaws in Evaluation Practices

Pervasive Limitations in Existing Benchmarks

The evaluation ecosystem for computational enzyme design suffers from several interconnected flaws that undermine the reliability and relevance of reported results:

Data Contamination: Public benchmarks frequently leak into training datasets, enabling models to memorize test items rather than demonstrating genuine generalization. This transforms benchmarking from a test of comprehension into a memorization exercise, significantly inflating performance metrics without corresponding advances in true capability [12] [13]. In computational biology, this manifests as benchmark datasets being used to train and validate methods on non-independent data, creating overoptimistic performance estimates [15].

Ignoring Functional Conservation: Many protein generation methods either ignore functional sites or select them randomly during generation, resulting in poor catalytic function and high false positive rates [14]. While general protein design has progressed significantly, these approaches often neglect the strict substrate-specific binding requirements and evolutionarily conserved functional sites essential for enzymatic activity [14] [11].

Absence of High-Quality Benchmarks: Existing enzyme design benchmarks are often synthetic with limited experimental grounding and lack evaluation protocols tailored to enzyme families [14]. Since enzymes are classified by their chemical reactions (EC numbers) rather than structure, meaningful evaluation demands benchmarks designed around enzyme families and their functional roles, which have been largely unavailable until recently [14].

Consequences of Standardization Gaps

The absence of standardized evaluation creates a distorted landscape where leaderboard positions can be manufactured, scientific signal is drowned out by noise, and community trust is eroded [13]. For drug development professionals, this translates to:

- Inability to accurately assess which computational methods are most suitable for specific design challenges

- Difficulty reproducing published results in independent laboratory settings

- Wasted resources on pursuing design approaches that perform well on benchmarks but fail in experimental validation

- Slowed innovation due to the lack of clear directional signals from evaluation metrics

Toward Robust Evaluation: Experimental Protocols and Metrics

Essential Metrics for Comprehensive Assessment

A robust benchmarking strategy for de novo enzymes must incorporate multiple dimensions of evaluation, spanning structural, functional, and practical considerations. The table below outlines key metric categories and their significance:

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation & Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Metrics | Designability, RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation), structural validity | Assesses whether generated protein structures are physically plausible and adopt intended folds [14]. |

| Functional Metrics | Catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM), EC number match rate, binding affinity | Measures how well the enzyme performs its intended chemical function [14] [11]. |

| Practical Metrics | Residue efficiency, thermostability, expression yield | Evaluates properties relevant to real-world applications and experimental feasibility [14]. |

| Specificity Metrics | Substrate specificity, reaction selectivity | Determines precision of molecular recognition and minimal off-target activity [11]. |

Standardized Experimental Workflow

A comprehensive benchmarking pipeline for de novo designed enzymes should integrate computational and experimental validation in a sequential manner. The following diagram illustrates this integrated workflow:

This workflow emphasizes the critical connection between computational design and experimental validation, ensuring that benchmarking reflects real-world performance. The process begins with curated datasets like EnzyBind, which provides 11,100 experimentally validated enzyme-substrate pairs with precise pocket structures [14]. Functional site annotation through multiple sequence alignment (MSA) identifies evolutionarily conserved regions critical for catalysis [14]. After model training and generation, in silico validation assesses structural plausibility before progressing to resource-intensive experimental steps.

Implementing Effective Benchmarking Strategies

Designing Custom Evaluation Frameworks

For researchers addressing specific enzymatic functions, generic benchmarks often fall short. Designing custom evaluation frameworks involves:

Creating Task-Specific Test Sets: Curate challenging examples that genuinely test your model's capabilities, reflecting actual application requirements rather than general capabilities. Effective approaches include manual curation of 10-15 high-quality examples, synthetic generation using existing LLMs for scale, and leveraging real user data for authentic test cases [12].

Combining Quantitative and Qualitative Metrics: Blend different evaluation approaches for comprehensive assessment. Develop custom metrics tailored to application requirements (e.g., factual accuracy for specific catalytic activities), connect model performance directly to business objectives rather than abstract technical metrics, and integrate human labeling, user feedback, and automated evaluation for balanced assessment [12].

Implementing LLM-as-Judge Methodologies: Employ language models to evaluate other LLMs' outputs using custom rubrics. This approach can achieve up to 85% alignment with human judgment—higher than the agreement among humans themselves (81%) [12].

Addressing Data Contamination and Bias

To ensure benchmarking integrity, researchers must implement safeguards against common pitfalls:

Data Hygiene Practices: Maintain strict separation between training, validation, and test datasets. For enzyme design, this means ensuring that benchmark structures and substrates are excluded from training data [13] [16].

Dynamic Benchmarking: Implement "live" benchmarks with fresh, unpublished test items produced on a rolling basis, preventing overfitting and test-set memorization [13] [16]. This approach is particularly valuable for enzyme design, where new catalytic functions and substrates continually emerge.

Cross-Validation Strategies: Employ multiple dataset testing and statistical validation techniques like bootstrap resampling to confirm that performance differences are statistically significant rather than artifacts of specific dataset characteristics [15] [17].

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Design Benchmarking

Successful benchmarking requires specific tools and resources. The table below details essential research reagents and their applications in evaluating de novo designed enzymes:

| Reagent/Resource | Function & Application | Key Features & Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| EnzyBind Dataset [14] | Provides experimentally validated enzyme-substrate complexes for training and evaluation | Contains 11,100 complexes with precise pocket structures; covers six catalytic types; includes functional site annotations via MSA |

| PDBBind Database [14] | Source of protein-ligand complexes for benchmarking | General database requiring curation for enzyme-specific applications; can be processed with RDKit library |

| MAFFT Software [14] | Multiple sequence alignment for functional site identification | Identifies evolutionarily conserved regions across enzymes with same EC number; critical for functional annotation |

| EnzyControl Framework [14] | Substrate-aware enzyme backbone generation | Integrates functional site conservation and substrate conditioning via EnzyAdapter; two-stage training improves stability |

| Specialized Benchmarks (MMLU, ARC, BigBench) [12] | Evaluate reasoning capabilities relevant to enzyme design | Test biological knowledge, scientific reasoning, and complex problem-solving abilities underlying design decisions |

| Dynamic Evaluation Platforms (PeerBench) [13] | Prevent data contamination through sealed execution | Community-governed evaluation with rolling test renewal; delayed transparency prevents gaming |

Future Directions in Enzyme Design Benchmarking

Emerging Standards and Methodologies

The field is evolving toward more rigorous and biologically relevant evaluation practices:

Integration of Engineering Principles: Next-generation benchmarking will incorporate principles of tunability, controllability, and modularity directly into evaluation criteria, reflecting the need for de novo proteins that can be precisely adjusted for specific applications [11].

Community-Governed Evaluation: Initiatives like PeerBench propose a complementary, certificate-grade evaluation layer with improved security and credibility through sealed execution, item banking with rolling renewal, and delayed transparency [13].

Functional-First Assessment: Moving beyond structural metrics toward functional capability benchmarks that evaluate whether designed enzymes can perform specific chemical transformations with efficiency and selectivity matching or exceeding natural counterparts [11].

Strategic Approach to Benchmarking

Addressing the benchmarking gap requires a systematic approach that aligns evaluation with ultimate application goals:

This strategic framework emphasizes that effective benchmarking is not merely about achieving high scores on standardized tests, but about ensuring that de novo designed enzymes meet the complex requirements of real-world applications. By defining appropriate metrics, implementing rigorous validation, and maintaining methodological transparency, researchers can bridge the current benchmarking gap and accelerate progress in computational enzyme design.

The benchmarking gap in computational enzyme design represents both a challenge and an opportunity for researchers and drug development professionals. By adopting standardized evaluation frameworks that integrate computational and experimental validation, focusing on functionally relevant metrics, and implementing safeguards against data contamination, the field can transition from isolated demonstrations of capability to robust, reproducible advances in protein design. As methods continue to improve, addressing these benchmarking limitations will be essential for realizing the full potential of de novo enzyme design in creating powerful new tools for biotechnology, medicine, and synthetic biology.

The grand challenge of computational protein engineering is the development of models that can accurately characterize and generate protein sequences for arbitrary functions. However, progress in this field has been notably hampered by three fundamental obstacles: the lack of standardized benchmarking opportunities, the scarcity of large and diverse protein function datasets, and limited access to experimental protein characterization [18] [1]. These limitations are particularly acute in the realm of de novo enzyme design, where computationally designed proteins must be rigorously evaluated against their natural counterparts to assess their functional viability.

In response to these challenges, the scientific community has initiated the Protein Engineering Tournament—a fully remote, open science competition designed to foster the development and evaluation of computational approaches in protein engineering [18]. This tournament represents a paradigm shift in how the field benchmarks progress, creating a transparent platform for comparing diverse methodologies while generating valuable experimental data for the broader research community. By framing de novo designed enzymes within this benchmarking context, researchers can systematically quantify the performance gap between computational designs and naturally evolved proteins, thereby accelerating methodological improvements.

The Protein Engineering Tournament: Structure and Implementation

Tournament Architecture and Design

The Protein Engineering Tournament employs a structured, two-round format that systematically evaluates both predictive and generative modeling capabilities [1] [19]. This bifurcated approach recognizes the distinct challenges inherent in predicting protein function from sequence versus designing novel sequences with desired functions.

The tournament begins with a predictive round where participants develop computational models to predict biophysical properties from provided protein sequences [1]. This round is further divided into two tracks: a zero-shot track that challenges participants to make predictions without prior training data, testing the intrinsic robustness and generalizability of their algorithms; and a supervised track where teams train their models on provided datasets before predicting withheld properties [1]. This dual-track approach benchmarks methods across different real-world scenarios that researchers face when working with proteins of varying characterization levels.

The subsequent generative round challenges teams to design novel protein sequences that maximize or satisfy specific biophysical properties [19]. Unlike the predictive round, which tests analytical capabilities, this phase tests creative design abilities. The most significant innovation is that submitted sequences are experimentally characterized using automated methods, providing ground-truth validation of computational predictions [18]. This closed-loop design, where digital designs meet physical validation, bridges the critical gap between in silico models and real-world protein function.

Experimental Workflow and Validation

The experimental workflow that supports the tournament represents a sophisticated pipeline for high-throughput protein characterization. The process begins with sequence design by participants, followed by DNA synthesis of the proposed variants [20]. The proteins are then expressed in appropriate systems, and multiple biophysical properties are measured through standardized assays [1]. Finally, the collected data is analyzed and open-sourced, creating new public datasets for continued benchmarking.

The diagram below illustrates this integrated computational-experimental workflow:

Key Research Reagents and Experimental Solutions

The Protein Engineering Tournament relies on a sophisticated infrastructure of research reagents and experimental solutions to enable high-throughput characterization of de novo designed proteins. The table below details the essential components of this experimental framework:

| Research Reagent/Resource | Function in Tournament | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-objective Datasets [1] | Provide benchmarking data for predictive and generative rounds | Enable model training and validation across diverse protein functions |

| Automated Characterization Platforms [18] | High-throughput measurement of biophysical properties | Enable rapid screening of expression, stability, and activity |

| DNA Synthesis Services [20] | Bridge computational designs and physical proteins | Convert digital sequences to DNA for protein expression |

| Cloud Science Labs [21] | Provide remote, reproducible experimental infrastructure | Democratize access to characterization capabilities |

| Standardized Assays [1] | Consistent measurement of enzyme properties | Ensure comparable results across different designs |

Benchmarking De Novo Designed Enzymes: Experimental Protocols and Data

Performance Metrics for Enzyme Evaluation

The tournament employs rigorous experimental protocols to benchmark de novo designed enzymes against natural counterparts. These protocols measure multiple biophysical properties that collectively define functional efficiency. For enzymatic proteins, key performance indicators include specific activity (catalytic efficiency), thermostability (resistance to thermal denaturation), and expression level (soluble yield in host systems) [1]. These metrics provide a comprehensive profile of enzyme functionality under conditions relevant to both natural and industrial environments.

The experimental characterization follows standardized workflows for each property. Specific activity is typically measured using spectrophotometric or fluorometric assays that monitor substrate conversion over time [1]. Thermostability is assessed through thermal denaturation curves, often using differential scanning fluorimetry, which measures melting temperature (Tm) [1]. Expression level is quantified by expressing proteins in standardized systems (e.g., E. coli) and measuring soluble protein yield via chromatographic or electrophoretic methods [1]. This multi-faceted approach ensures that de novo designs are evaluated across the same parameters as natural enzymes.

Comparative Performance Data: Pilot Tournament Results

The pilot Protein Engineering Tournament generated valuable comparative data through six multi-objective datasets covering diverse enzyme classes including α-amylase, aminotransferase, imine reductase, alkaline phosphatase, β-glucosidase, and xylanase [1]. The table below summarizes the experimental data collected for benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against natural counterparts:

| Enzyme Target | Experimental Measurements | Data Points | Benchmarking Focus |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-Amylase [1] | Expression, Specific Activity, Thermostability | 28,266 | Multi-property optimization |

| Aminotransferase [1] | Activity across 3 substrates | 441 | Substrate promiscuity |

| Imine Reductase [1] | Fold Improvement Over Positive control (FIOP) | 4,517 | Catalytic efficiency |

| Alkaline Phosphatase [1] | Activity against 3 substrates with different limitations | 3,123 | Substrate specificity and binding |

| β-Glucosidase B [1] | Activity and Melting Point | 912 | Stability-activity tradeoffs |

| Xylanase [1] | Expression Level | 201 | Expressibility and solubility |

This comprehensive dataset enables direct comparison between de novo designed variants and natural enzyme benchmarks across multiple performance dimensions. The α-amylase dataset is particularly valuable as it captures the complex trade-offs between activity, stability, and expression that enzyme engineers must balance [1].

Case Study: PETase Engineering for Plastic Degradation

Real-World Application and Experimental Design

The 2025 Protein Engineering Tournament exemplifies how this benchmarking initiative addresses pressing global challenges through the design of plastic-eating enzymes [20]. This case study focuses on PETase, an enzyme that degrades polyethylene terephthalate (PET) plastic into reusable monomers, offering a promising solution for enzymatic recycling [20]. The tournament challenges participants to engineer PETase variants that can withstand the harsh conditions of industrial recycling processes while maintaining high catalytic activity against solid plastic substrates.

The experimental design for benchmarking PETase variants incorporates real-world operational constraints. Enzymes are evaluated for thermal stability at elevated temperatures typical of industrial processes, pH tolerance across the range encountered in recycling workflows, and activity against solid PET substrates rather than simplified soluble analogs [20]. This rigorous experimental framework ensures that computational designs are benchmarked against performance requirements that matter for practical application, moving beyond idealized laboratory conditions.

Research Reagents for PETase Characterization

The PETase tournament employs specialized research reagents to enable accurate benchmarking. Twist Bioscience provides variant libraries and gene fragments to build a first-of-its-kind functional dataset for PETase [20]. EvolutionaryScale offers participants access to state-of-the-art protein language models, while Modal Labs provides computational infrastructure for running intensive parallelized model testing [20]. This combination of biological and computational resources creates a level playing field where teams compete based on algorithmic innovation rather than resource availability.

Significance and Future Directions

Protein Engineering Tournaments represent a transformative approach to benchmarking in computational protein design. By creating standardized evaluation frameworks and generating open-access datasets, these initiatives accelerate progress in de novo enzyme design [19]. The tournament model has demonstrated its viability through the pilot event and is now scaling to address larger challenges with the 2025 PETase competition [20].

The open science aspect of these tournaments is particularly significant for establishing transparent benchmarking standards. By making all datasets, experimental protocols, and methods publicly available after each tournament, the initiative creates a cumulative knowledge commons that benefits the entire research community [18] [19]. This approach enables researchers to build upon previous results systematically, avoiding redundant effort and facilitating direct comparison of new methods against established benchmarks.

For the field of de novo enzyme design, these tournaments provide crucial experimental validation of computational methods. As noted in research on de novo proteins, while computational predictions can suggest structural viability, experimental characterization remains essential to confirm that designs adopt stable folds and perform their intended functions [22]. The integration of high-throughput experimental validation within the tournament framework thus bridges a critical gap between computational prediction and biological reality, establishing a robust foundation for benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against their natural counterparts.

The field of de novo enzyme design has progressed remarkably, transitioning from theoretical concept to practical application with enzymes capable of catalyzing new-to-nature reactions. However, the absence of standardized evaluation frameworks has hindered meaningful comparison between methodologies and a clear understanding of their relative strengths and weaknesses. This guide establishes a comprehensive benchmarking framework centered on three core objectives: assessing sequence plausibility (how natural the designed sequence appears), structural fidelity (how well the designed structure matches the intended fold), and functional alignment (how effectively the designed enzyme performs its intended catalytic role). By applying this framework, researchers can objectively compare diverse design strategies, identify areas for improvement, and accelerate the development of efficient biocatalysts for applications in therapeutics, biocatalysis, and sustainable manufacturing.

The PDFBench benchmark, a recent innovation, systematically addresses this gap by evaluating protein design models across multiple dimensions, ensuring fair comparisons and providing key insights for future research [6]. This guide leverages such emerging standards to provide a structured approach for comparing de novo designed enzymes against natural counterparts and other designed variants.

Comparative Performance Analysis of Design Methodologies

A rigorous benchmarking process involves evaluating designed enzymes against a suite of computational and experimental metrics. The table below summarizes core metrics and typical performance ranges observed in state-of-the-art design tools, providing a baseline for comparison.

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics for De Novo Enzyme Design

| Evaluation Dimension | Specific Metric | Measurement Purpose | Typical Benchmarking Range / Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Plausibility | Perplexity (PPL) [6] | Measures how "surprised" a language model is by a sequence; lower scores indicate more native-like sequences. | Correlates with structural reliability (e.g., Pearson correlation of 0.76 with pLDDT) [6]. |

| Sequence Recovery [23] | Percentage of residues in a native structure that a design method can recover when redesigning the sequence. | Used to assess the native-likeness of sequences designed for known backbones. | |

| Structural Fidelity | pLDDT (predicted LDDT) [23] | AI-predicted local distance difference test; measures confidence in local structure (0-100). | High values (>80) indicate well-folded, confident local predictions [6]. |

| Predicted Aligned Error (PAE) [6] | AI-predicted error between residues; assesses global fold confidence and domain packing. | Lower scores indicate higher confidence in the overall topology and fold [6]. | |

| RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | Measures the average distance between atoms of a predicted structure and a reference (e.g., design model or native structure). | Used to quantify the accuracy of structure prediction for designs or the geometric deviation from idealized models [23]. | |

| Functional Alignment | Retrieval Accuracy [6] | Assesses if a generated protein's predicted function matches the input specification. | Highly sensitive to the retrieval strategy used for evaluation [6]. |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Key experimental kinetic parameter measuring an enzyme's overall ability to convert substrate to product. | Designed enzymes often start low (e.g., ≤ 102 M⁻¹s⁻¹) and are improved orders of magnitude by directed evolution [4]. | |

| Novelty & Diversity [6] | Measures how distinct generated proteins are from known natural sequences and from each other. | Prevents the design of proteins that are merely replicas of existing natural ones. |

Structural Fidelity: The Challenge of Idealized Geometries

A significant challenge in de novo design is the tendency of AI-based methods to produce proteins with highly idealized, rigid geometries, which often lack the nuanced structural variations necessary for complex functions like catalysis [23]. This bias is also reflected in structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2, which systematically favor these idealized forms, potentially overestimating the quality of designs that diverge from perfect symmetry [23].

Experimental Protocol for Assessing Structural Fidelity:

- Backbone Generation: Use methods like RFdiffusion or LUCS to generate protein backbones based on a target fold [23].

- Sequence Design: Use a sequence design tool (e.g., ProteinMPNN) to generate amino acid sequences for the designed backbones [23].

- Structure Prediction: Employ a structure prediction network (e.g., AlphaFold2, ESMFold) to predict the 3D structure of the designed sequences [23].

- Structural Comparison: Calculate the RMSD between the AI-predicted structure and the original design model. A low RMSD indicates high structural fidelity, while a high RMSD may indicate a bias in the predictor or an unstable design [23].

Figure 1: Workflow for assessing the structural fidelity of a de novo designed enzyme.

Functional Alignment: From Scaffold to Active Catalyst

Designing a stable scaffold is only the first step; incorporating functional activity is a greater challenge. Directed evolution often remains essential to boost the low catalytic efficiencies of initial designs [4]. Studies on de novo Kemp eliminases reveal that mutations distant from the active site ("Shell" mutations) play a critical role in facilitating the catalytic cycle by tuning structural dynamics to aid substrate binding and product release [4].

Table 2: Analysis of Kemp Eliminase Variants Through Directed Evolution

| Variant Type | Definition | Impact on Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Primary Functional Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designed | Original computational design, often with essential catalytic residues. | Baseline (e.g., ≤ 10² M⁻¹s⁻¹) [4]. | Creates the basic active site architecture. |

| Core | Contains mutations within or directly contacting the active site. | 90 to 1500-fold increase over Designed [4]. | Pre-organizes the active site for efficient chemical transformation [4]. |

| Shell | Contains mutations far from the active site (distal mutations). | Generally modest alone (e.g., 4-fold), but crucial when combined with Core [4]. | Facilitates substrate binding and product release by modulating structural dynamics [4]. |

| Evolved | Contains both Core and Shell mutations from directed evolution. | Several orders of magnitude higher than Designed [4]. | Combines pre-organized chemistry with optimized catalytic cycle dynamics. |

Experimental Protocol for Kinetic Characterization:

- Protein Expression and Purification: Clone the gene encoding the designed enzyme into a suitable expression vector. Express the protein in a host system (e.g., E. coli) and purify it using chromatography techniques (e.g., affinity, size exclusion) [4].

- Enzyme Kinetics Assay: Measure the initial rate of the reaction (v0) at varying substrate concentrations ([S]) under specified conditions (pH, temperature).

- Data Analysis: Plot v0 against [S] and fit the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 = (Vmax * [S]) / (KM + [S])). Derive the kinetic parameters kcat (turnover number) and KM (Michaelis constant), which are used to calculate catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Experimental Materials

Success in designing and benchmarking de novo enzymes relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Design and Validation

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application | Relevance to Benchmarking Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| ProteinMPNN [23] | A graph neural network for designing amino acid sequences that stabilize a given protein backbone. | Sequence Plausibility: Generates novel, foldable sequences for target structures. |

| AlphaFold2/3 [23] | Deep learning system for predicting a protein's 3D structure from its amino acid sequence. | Structural Fidelity: Used as an in silico filter to assess if a designed sequence will adopt the intended fold. |

| ESMFold [23] | A language-based protein structure prediction model that operates quickly without multiple sequence alignments. | Structural Fidelity: Provides rapid structural validation of designed sequences. |

| Transition State Analogue(e.g., 6NBT for Kemp eliminases) [4] | A stable molecule that mimics the geometry and electronics of a reaction's transition state. | Functional Alignment: Used in X-ray crystallography to verify the active site is pre-organized for catalysis. |

| 6-Nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) [4] | A specific transition state analogue for the Kemp elimination reaction. | Functional Alignment: Essential for experimental validation of Kemp eliminase active site geometry and binding [4]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software(e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Functional Alignment: Reveals dynamics, flexibility, and mechanisms like substrate access and product release [4]. |

| SwissTest Dataset [6] | A curated benchmark dataset for keyword-guided protein design with strict time cutoffs to prevent data leakage. | All Objectives: Provides a fair and standardized test set for evaluating and comparing different design models. |

The systematic benchmarking of de novo enzymes across sequence, structure, and function is no longer a luxury but a necessity for the field's maturation. The comparative data and protocols outlined in this guide provide a roadmap for researchers to critically evaluate their designs. The integration of AI-powered tools like EZSpecificity for predicting substrate specificity [24] and the fine-tuning of structure prediction models on diverse, non-idealized scaffolds [23] represent the next frontier. Furthermore, the growing emphasis on sustainability in industrial processes is a major driver for enzyme engineering [25] [26]. As the field evolves, benchmarking efforts must expand to include metrics for stability under non-biological conditions, substrate promiscuity, and performance in industrial-relevant environments. By adopting a rigorous and standardized approach to assessment, the scientific community can deconvolute the complex contributions to enzyme function, leading to more predictive design and, ultimately, the creation of powerful new biocatalysts.

Frameworks and Metrics for Evaluating Designed Enzymes

The field of enzyme engineering is being transformed by de novo protein design, where novel proteins are created from scratch to perform specific functions. A critical component of this progress is the development of robust benchmarks that allow researchers to compare methods, validate results, and drive innovation. This guide provides an objective comparison of three major benchmarking platforms—PDFBench, 'Align to Innovate', and ReactZyme—which represent the cutting edge in evaluating computational protein design. Framed within broader research on benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against natural counterparts, this analysis examines each platform's experimental protocols, performance metrics, and applicability to real-world enzyme engineering challenges, providing researchers with the necessary context to select appropriate tools for their specific projects.

The three benchmark platforms address complementary aspects of protein design evaluation, each with distinct methodological approaches and application focus areas.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Protein Design Benchmarks

| Feature | PDFBench | 'Align to Innovate' | ReactZyme |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Focus | De novo protein design from functional descriptions | Enzyme engineering and optimization | Enzyme-reaction prediction |

| Task Types | Description-guided and keyword-guided design | Property prediction and generative design | Reaction retrieval and prediction |

| Data Sources | SwissProtCLAP, Mol-Instructions, novel SwissTest | Experimental data from 4 enzyme families | SwissProt and Rhea databases |

| Evaluation Approach | Computational metrics against reference datasets | Both in silico prediction and in vitro experimental validation | Computational retrieval accuracy |

| Key Innovation | Unified evaluation framework with correlation analysis | Fully automated GenAI platform with real-world validation | Reaction-based enzyme annotation |

PDFBench establishes itself as the first comprehensive benchmark specifically for function-guided de novo protein design, addressing a significant gap in the field where methods were previously assessed using inconsistent metric subsets [27]. The platform supports two distinct tasks: description-guided design (using textual functional descriptions as input) and keyword-guided design (using function keywords and domain locations as input) [5]. Its comprehensive evaluation covers 22 metrics across sequence plausibility, structural fidelity, and language-protein alignment, providing a multifaceted assessment framework [5].

The 'Align to Innovate' benchmark takes a more application-oriented approach, focusing specifically on enzyme engineering scenarios that closely mimic real-world challenges [28]. Unlike purely computational benchmarks, it incorporates experimental validation through a tournament structure that connects computational modeling directly to high-throughput experimentation [29]. This creates tight feedback loops between computation and experiments, setting shared goals for generative protein design across the research community [29].

ReactZyme addresses a different but complementary aspect of enzyme informatics—predicting which reactions specific enzymes catalyze [30]. It introduces a novel approach to annotating enzymes based on their catalyzed reactions rather than traditional protein family classifications, providing more detailed insights into specific reactions and adaptability to newly discovered reactions [30]. By framing enzyme-reaction prediction as a retrieval problem, it aims to rank enzymes by their catalytic ability for specific reactions, facilitating both enzyme discovery and function annotation [30].

Performance Metrics and Experimental Data

Each platform employs distinct evaluation methodologies and metrics tailored to their specific objectives, with varying levels of experimental validation.

Table 2: Performance Metrics and Experimental Results

| Platform | Key Metrics | Reported Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDFBench | 22 metrics across: sequence plausibility, structural fidelity, language-protein alignment, novelty, diversity | Evaluation of 8 state-of-the-art models; specific results not yet detailed in available sources | Computational evaluation only using standardized test sets |

| 'Align to Innovate' | Spearman rank correlation for enzyme property prediction | β-glucosidase B: Spearman 0.36 (best result); outperformed competitors (0.08 to -0.3); tied/beat first place in 5/5 cases | In vitro experimental validation of designed enzymes |

| ReactZyme | Retrieval accuracy for enzyme-reaction pairs | Based on largest enzyme-reaction dataset to date (from SwissProt and Rhea) | Computational validation against known enzyme-reaction pairs |

The 'Align to Innovate' benchmark provides the most concrete performance data, with Cradle's models achieving a Spearman rank of 0.36 on the challenging β-glucosidase B enzyme, substantially outperforming competitors whose scores ranged from 0.08 to -0.3 [28]. According to the platform's developers, a Spearman rank of at least 0.4 is required for a model to be considered useful, and at least 0.7 to be considered "good" in the context of AI for protein engineering [28]. The benchmark evaluated performance across four enzyme families: alkaline phosphatase, α-amylase, β-glucosidase B, and imine reductase [28].

PDFBench takes a more comprehensive approach to metrics, compiling 22 different evaluation criteria but without yet providing specific performance data for the evaluated models in the available sources [27] [5]. The platform analyzes inter-metric correlations to explore relationships between four categories of metrics and offers guidelines for metric selection [10]. This approach aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of evaluation criteria beyond single-score comparisons.

ReactZyme leverages the largest enzyme-reaction dataset to date, derived from SwissProt and Rhea databases with entries up to January 2024 [30]. While specific accuracy figures aren't provided in the available sources, the benchmark is recognized at the 38th Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS 2024) Track on Datasets and Benchmarks, indicating peer recognition of its methodological rigor [30].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The benchmarking platforms employ distinct experimental workflows, each with specialized processes for data preparation, model training, and evaluation.

PDFBench Methodology

PDFBench employs a structured approach to dataset construction and model evaluation. For the description-guided task, it compiles 640K description-sequence pairs from SwissProtCLAP (441K pairs from UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot) and Mol-Instructions (196K protein-oriented instructions) [5]. For keyword-guided design, it creates a novel dataset containing 554K keyword-sequence pairs from CAMEO using InterPro annotations [5]. The test set for description-guided design uses the Mol-Instructions test subset, while the training combines remaining data with SwissProtCLAP to form SwissMolinst [5]. Evaluation encompasses 13-16 metrics assessing sequence, structure, and language alignment, with specific attention to novelty and diversity of designed proteins [27] [5].

PDFBench Experimental Workflow: The benchmark integrates multiple data sources to evaluate protein design models through description-guided and keyword-guided tasks, employing comprehensive metrics across sequence, structure, and alignment dimensions with correlation analysis.

'Align to Innovate' Experimental Protocol

The 'Align to Innovate' tournament follows a rigorous two-phase experimental design that incorporates both computational and wet-lab validation [29]. The process begins with a predictive phase where participants predict functional properties of protein sequences, with these predictions scored against experimental data [29]. Top teams from the predictive round then advance to the generative phase, where they design new protein sequences with desired traits [29]. These designs are synthesized, tested in vitro, and ranked based on experimental performance [29].

Cradle's implementation of this benchmark utilizes automated pipelines that begin by running MMseqs to retrieve and align homologous sequences, then fine-tune a foundation model on this evolutionary context [28]. The automated pipeline forks to create both 'generator' models (fine-tuned via preference-based optimization on in-domain training labels) and 'predictor' models (fine-tuned using ranking losses to obtain an ensemble) [28]. This approach enables fully automated GenAI protein engineering without requiring human intervention [28].

ReactZyme Methodology

ReactZyme formulates enzyme-reaction prediction as a retrieval problem, aiming to rank enzymes by their catalytic ability for specific reactions [30]. The benchmark employs machine learning algorithms to analyze enzyme reaction datasets derived from SwissProt and Rhea databases [30]. This approach enables recruitment of proteins for novel reactions and prediction of reactions in novel proteins, facilitating both enzyme discovery and function annotation [30]. The methodology is designed to provide a more refined view on enzyme functionality compared to traditional classifications based on protein family or expert-derived reaction classes [30].

Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of protein design benchmarks requires specific computational tools and data resources that constitute the essential research reagents for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Protein Design Benchmarking

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Platform Usage |

|---|---|---|---|

| SwissProtCLAP | Dataset | Provides 441K description-sequence pairs from UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | PDFBench: Training data for description-guided design |

| Mol-Instructions | Dataset | Diverse, high-quality instruction dataset with 196K protein design pairs | PDFBench: Test set for description-guided task |

| CAMEO/InterPro | Dataset | Protein structure and function annotations | PDFBench: Source for 554K keyword-sequence pairs |

| MMseqs2 | Software Tool | Rapid sequence search and clustering of large datasets | 'Align to Innovate': Retrieval and alignment of homologous sequences |

| Rhea Database | Database | Expert-curated biochemical reactions with EC annotations | ReactZyme: Source of enzyme reaction data for prediction tasks |

| Spearman Rank | Statistical Metric | Measures ability to correctly order protein sequences by property | 'Align to Innovate': Primary evaluation metric for enzyme properties |

| Foundation Models | AI Model | Pre-trained protein language models adapted for specific tasks | All platforms: Base models fine-tuned for specific design objectives |

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

Each benchmarking platform offers distinct advantages for different aspects of de novo enzyme design research, with varying strengths in experimental validation, metric comprehensiveness, and practical applicability.

Platform Strengths and Limitations

PDFBench provides the most comprehensive evaluation framework for purely computational protein design, with its extensive metric collection and correlation analysis addressing the critical need for standardized comparison [27] [10]. However, it currently lacks experimental validation, focusing exclusively on in silico performance [5]. This makes it highly valuable for methodological development but less conclusive for real-world application predictions.

The 'Align to Innovate' benchmark offers the strongest experimental validation through its tournament structure that incorporates wet-lab testing of designed enzymes [29]. The demonstrated performance of Cradle's automated models—achieving state-of-the-art results with zero human intervention—shows the practical maturity of AI-driven protein engineering [28]. However, its focus on specific enzyme families may limit generalizability across all protein types.

ReactZyme addresses a fundamentally different but complementary problem of reaction prediction rather than protein design [30]. Its novel annotation approach based on catalyzed reactions provides greater adaptability to newly discovered reactions compared to traditional classification systems [30]. This makes it particularly valuable for enzyme function prediction and discovery applications.

Selection Guidelines for Research Applications

For de novo enzyme design methodology development: PDFBench provides the most comprehensive computational evaluation framework, particularly for text-guided and keyword-guided design approaches [27] [5].

For real-world enzyme engineering with experimental validation: 'Align to Innovate' offers the most direct path from computational design to experimental testing, with proven success in optimizing enzyme properties [28] [29].

For enzyme function annotation and reaction prediction: ReactZyme provides specialized benchmarking for predicting which reactions specific enzymes catalyze, supporting enzyme discovery applications [30].

For automated protein engineering pipelines: 'Align to Innovate' demonstrates state-of-the-art performance with fully automated GenAI systems, significantly reducing human intervention requirements [28].

The continuing evolution of these benchmarks, particularly with the integration of experimental validation as demonstrated by 'Align to Innovate', represents a crucial advancement toward reliable de novo enzyme design that can successfully transition from computational models to real-world applications with predictable performance characteristics.

The field of de novo protein design is undergoing a revolutionary shift, moving beyond the constraints of natural evolutionary templates to create entirely novel proteins with customized functions [9] [31]. This paradigm, heavily propelled by artificial intelligence (AI), enables the computational creation of functional protein modules with atom-level precision, opening vast possibilities in therapeutic development, enzyme engineering, and synthetic biology [9] [32]. However, the power to design from first principles brings a critical challenge: the need for robust, standardized methods to evaluate these novel designs, particularly when the target is a complex function like enzymatic catalysis.

Function-guided protein design tasks are primarily categorized into two distinct approaches: description-guided design, which uses rich textual descriptions of protein function as input, and keyword-guided design, which employs specific functional keywords or domain annotations [5]. Assessing these methods requires more than just measuring structural correctness; it demands a comprehensive evaluation of how well the generated protein performs its intended task. This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of these two approaches, framing them within the broader research objective of benchmarking de novo designed enzymes against their natural counterparts. We synthesize current evaluation methodologies, present quantitative performance data, and detail the experimental protocols needed to assess design success, providing researchers with a practical toolkit for rigorous protein design validation.

Comparative Analysis: Input Modalities and Their Applications

The choice between description-guided and keyword-guided design significantly impacts the design process, the type of proteins generated, and the applicable evaluation strategies. The table below outlines the core characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Description-Guided and Keyword-Guided Design

| Feature | Description-Guided Design | Keyword-Guided Design |

|---|---|---|

| Input Format | Natural language text describing overall protein function [5] | Structured keywords (e.g., family, domain) with optional location tuples [5] |

| Input Example | "An enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of ester bonds in lipids." | K={("Hydrolase", 15-85), ("Lipase", 120-200)} |

| Flexibility | High; allows for creative, complex functional specifications [5] | Moderate; precise and structured, but constrained by predefined vocabularies [5] |

| Primary Task | Generate novel protein sequence (P) conditioned on text (t): (p(P \mid t)) [5] | Generate novel protein sequence (P) conditioned on keywords (K): (p(P \mid K)) [5] |

| Ideal Use Case | Exploring novel functions not perfectly described by existing keywords; broad functional ideation. | Engineering proteins with specific, well-defined functional domains and motifs; incorporating known catalytic sites. |

The relationship between these tasks and their evaluation within a benchmarking framework is structured as follows:

Performance Benchmarking: A Quantitative Comparison

The introduction of unified benchmarks like PDFBench has enabled fair and comprehensive comparisons between different protein design approaches [5] [27] [10]. PDFBench evaluates models across 22 distinct metrics covering sequence plausibility, structural fidelity, and language-protein alignment, in addition to measures of novelty and diversity [5]. The following table summarizes the typical performance profile of description-guided versus keyword-guided methods on key quantitative metrics.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison on PDFBench Metrics

| Evaluation Metric | Evaluation Dimension | Description-Guided Design | Keyword-Guided Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Perplexity | Sequence Plausibility | Moderate to High | Generally Lower |

| Structure-based F1 | Structural Fidelity | Variable, depends on description specificity | Typically Higher |

| scRMSD (Å) | Structural Fidelity | Higher (more deviation) | Lower (closer to native) |

| Designability | Structural Fidelity | Moderate | Higher [14] |

| Language-Protein Alignment | Functional Alignment | Directly optimized | Indirectly measured |

| Novelty & Diversity | Functional Potential | Higher | Moderate |

| EC Number Match Rate | Functional Accuracy | Moderate | Higher [14] |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Functional Performance | Can be lower without structural precision | Can be 13%+ higher with substrate-aware design [14] |

Performance data indicates that keyword-guided methods often hold an advantage in generating structurally sound and designable proteins, likely due to the more explicit structural constraints provided by functional keywords and location information [5] [14]. For instance, enzyme-specific models like EnzyControl, which conditions generation on annotated catalytic sites and substrates, demonstrate marked improvements, achieving up to a 13% relative increase in designability and 13% improvement in catalytic efficiency over baseline models [14]. This highlights the strength of keyword-guided approaches for applications requiring high structural fidelity and precise function, such as enzyme engineering.

Conversely, description-guided design excels in exploring a broader and more novel functional space, as natural language can describe complex functions without being tethered to a predefined ontological vocabulary [5]. The trade-off often involves a potential decrease in structural metrics like scRMSD (side-chain root-mean-square deviation), as the model must infer structural implications from text.

Experimental Protocols for Functional Validation

Rigorous experimental validation is paramount to establishing the functional credibility of a de novo designed protein, especially when benchmarking against natural enzymes. The following workflow details a multi-stage protocol for this purpose.

Protocol Details and Data Interpretation

In Silico Design & Screening: Candidate proteins are generated using state-of-the-art models. The resulting sequences are then filtered using protein structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to ensure they adopt stable, folded conformations. Promising candidates proceed to computational analysis of stability and dynamics through Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, which can reveal how distal mutations influence functional properties like product release [4].

Physicochemical Characterization: Selected designs are experimentally expressed and purified. Key metrics at this stage include purity (assessed by SDS-PAGE) and secondary structure content (verified by Circular Dichroism spectroscopy). This confirms that the protein is properly folded and monodisperse.

In Vitro Functional Assays: For enzymatic designs, steady-state kinetics assays are essential. Measurements of (KM) (Michaelis constant), (k{cat}) (turnover number), and catalytic efficiency (k{cat}/KM) provide a direct quantitative comparison to natural enzymes. For example, studies on de novo Kemp eliminases use these kinetics to distinguish the contributions of active-site (Core) versus distal (Shell) mutations [4].

High-Resolution Structural Analysis: The gold standard for validation is determining the atomic structure via X-ray crystallography. This confirms whether the designed protein adopts the intended fold and, if co-crystallized with a substrate or transition-state analogue, validates the geometry of the active site. Comparing bound and unbound structures can also reveal if the active site is preorganized for catalysis, a key feature of efficient enzymes [4].

Advancing research in this field requires a suite of computational and experimental resources. The following table catalogs key reagents, datasets, and software platforms that constitute the essential toolkit for researchers benchmarking de novo designed enzymes.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Protein Design Benchmarking

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Relevance to Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDFBench [5] [27] | Computational Benchmark | Standardized evaluation of function-guided design models. | Provides 22 metrics for fair comparison across description and keyword-guided tasks. |

| SwissProtCLAP [5] | Dataset (Description-Guided) | Curated description-sequence pairs from UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot. | Training and evaluation data for description-guided models. |

| EnzyBind [14] | Dataset (Enzyme-Specific) | Experimentally validated enzyme-substrate pairs with MSA-annotated functional sites. | Enables substrate-aware enzyme design and functional benchmarking. |

| AlphaFold2 [31] | Software Tool | High-accuracy protein structure prediction. | Rapid in silico validation of designed protein folds. |

| Rosetta [11] | Software Suite | Physics-based modeling for protein design and refinement. | Complementary refinement of AI-generated designs and energy calculations. |

| 6-Nitrobenzotriazole (6NBT) [4] | Chemical Reagent | Transition-state analogue for Kemp elimination reaction. | Used in crystallography and binding studies to validate active sites of designed Kemp eliminases. |

| FrameFlow [14] | Software Tool (Motif-Scaffolding) | Generative model for protein backbone generation. | Serves as a base model for enzyme-specific methods like EnzyControl. |

The strategic choice between description-guided and keyword-guided protein design is not a matter of declaring one superior, but of aligning the method with the research goal. Description-guided design offers a powerful pathway to functional novelty and exploration, leveraging the flexibility of natural language to venture into uncharted regions of the protein functional universe. In contrast, keyword-guided design provides a structured approach for achieving high structural fidelity and precise function, making it particularly suited for engineering tasks like enzyme design where specific, well-defined functional motifs are critical.

The ongoing development of comprehensive benchmarks like PDFBench and specialized enzymatic datasets like EnzyBind is critical for providing the fair, multi-faceted evaluations needed to drive the field forward [5] [14]. As AI-driven design continues to mature, the integration of these approaches—perhaps using rich descriptions for initial ideation and precise keywords for functional refinement—will likely push the boundaries of what is possible. This will enable the robust creation of de novo enzymes that not only match but potentially surpass their natural counterparts, fully unlocking the promise of computational protein design for therapeutic and biotechnological advancement.

The field of de novo enzyme design has matured, moving from theoretical proof-of-concept to the creation of artificial enzymes that catalyze abiotic reactions, such as an artificial metathase for olefin metathesis in living cells [33]. As these designs increase in complexity, the need for robust, multi-faceted computational metrics to benchmark them against their natural counterparts becomes critical. Reliable benchmarking is the cornerstone of progress, allowing researchers to quantify advancements, identify shortcomings, and guide subsequent design iterations. This guide objectively compares the performance of different classes of computational metrics—sequence-based, structure-based, and the emerging class of language-model-based scores—within the specific context of evaluating de novo designed enzymes. The integration of these metrics provides a holistic framework for assessing how well a computational design mimics the sophisticated functional properties of natural enzymes, bridging the gap between in silico models and in vivo functionality.

A Comparative Framework of Computational Metrics

The evaluation of proteins, whether natural or de novo designed, relies on a hierarchy of metrics that probe different levels of organization, from the primary sequence to the tertiary structure and its functional dynamics. The table below summarizes the core classes of metrics, their foundational principles, and their primary applications in benchmarking.

Table 1: Core Classes of Computational Metrics for Protein Benchmarking

| Metric Class | Foundational Principle | Key Metrics & Tools | Primary Application in Benchmarking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based | Quantifies similarity based on amino acid identity and substitution likelihoods. | BLAST, PSI-BLAST, CLUSTAL, Percentage Identity. | Identifying homologous natural proteins; assessing evolutionary distance and gross functional potential. |

| Structure-Based | Quantifies similarity based on the three-dimensional arrangement of atoms. | TM-score, RMSD, TM-align, Dali, DeepBLAST. | Assessing the fidelity of a designed protein's fold against a target; evaluating structural novelty. |

| Language-Model-Based | Leverages deep learning on sequence databases to infer structural and functional properties. | TM-Vec, DeepBLAST, ESMFold, Protein Language Model (pLM) Embeddings. | Remote homology detection; predicting structural similarity and functional sites directly from sequence. |

Sequence-Based Metrics: The First Line of Inquiry

Sequence-based methods are the most established and widely used for initial protein comparison. They operate on the principle that evolutionary relatedness and functional similarity are reflected in sequence conservation.

- Methodology: Tools like BLAST use heuristics to find regions of local similarity, scoring alignments based on substitution matrices (e.g., BLOSUM62) which encode the likelihood of one amino acid replacing another over evolutionary time [34]. Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) tools like CLUSTAL and MAFFT extend this by progressively aligning sequences based on a guide tree to identify conserved residues and motifs [35].

- Experimental Application: In a benchmark study comparing 1,800 putative de novo proteins from human and fly to synthetic random sequences, initial bioinformatic predictions showed remarkably similar distributions of biophysical properties like intrinsic disorder and aggregation propensity when amino acid composition and length were matched [22]. This highlights that sequence composition can be a major determinant of predicted properties, but also reveals the limitation of pure sequence-based analysis, as experimental validation later showed differences in solubility.

Structure-Based Metrics: The Gold Standard for Fold Assessment

When the three-dimensional structure is available, structure-based metrics provide a more direct and informative comparison than sequence alone, as structure is more conserved through evolution.

- Methodology: