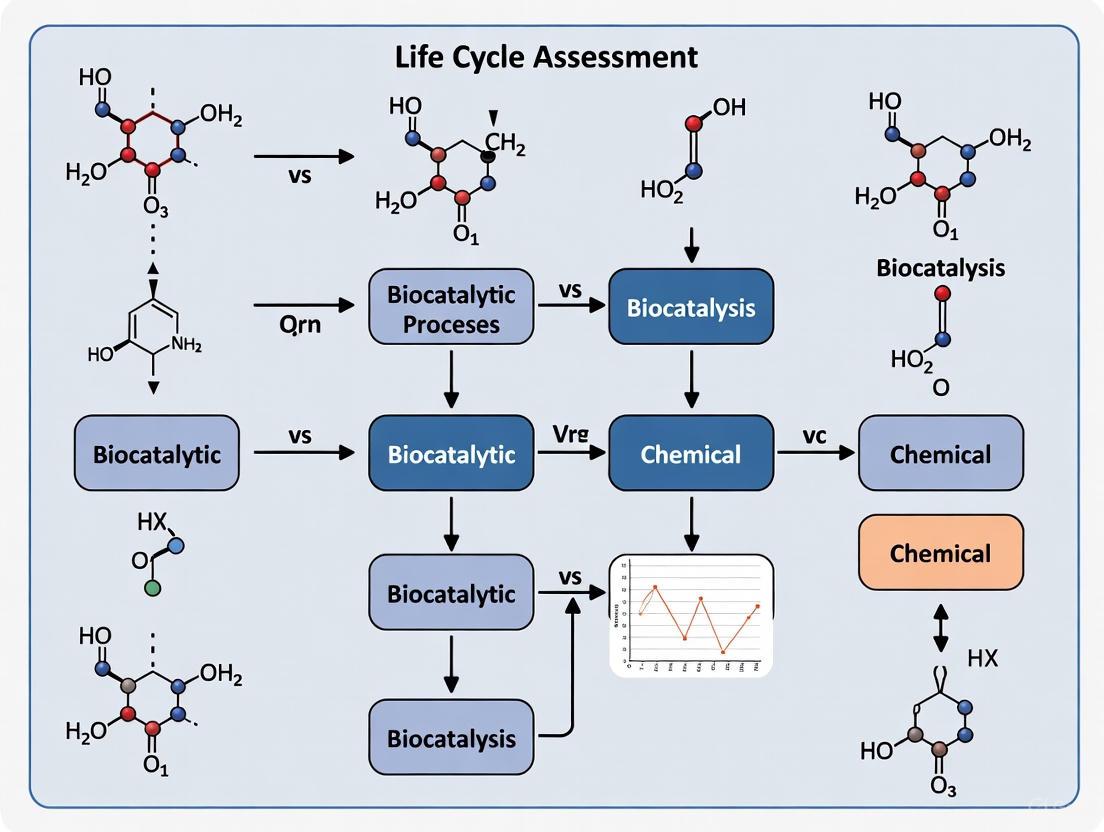

Biocatalytic vs Chemical Processes: A Life Cycle Assessment Guide for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodologies for comparing biocatalytic and chemical manufacturing processes.

Biocatalytic vs Chemical Processes: A Life Cycle Assessment Guide for Sustainable Pharmaceutical Development

Abstract

This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive analysis of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) methodologies for comparing biocatalytic and chemical manufacturing processes. It covers foundational LCA principles and explores the application of LCA in early-stage R&D for route selection. The guide addresses common data challenges and optimization strategies, supported by critical reviews of existing literature and compelling case studies that validate the significant environmental advantages of biocatalysis, such as drastically reduced global warming potential. The synthesis concludes with future directions for standardizing LCA practices in the pharmaceutical industry to advance sustainable drug development.

Life Cycle Assessment and Green Chemistry: Foundational Principles for Sustainable Process Design

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction (cradle) to disposal (grave) [1]. For researchers and professionals in drug development and chemical synthesis, LCA provides a quantitative framework to support environmentally conscious decisions and sustainable process design [1]. The methodology is standardized internationally through the ISO 14040 and ISO 14044 standards, which provide the foundational principles, framework, and detailed requirements for conducting credible and consistent LCA studies [2] [1].

The critical importance of LCA in pharmaceutical and chemical research lies in its ability to reveal hidden environmental trade-offs. A singular focus on a single metric, such as carbon emissions, can lead to oversimplification or unintended consequences in other impact areas [3]. LCA avoids this pitfall by adopting a holistic perspective that encompasses multiple environmental impact categories, from global warming potential to resource depletion and water use [3]. This is particularly valuable in early-stage process development, as demonstrated by a comparative LCA of 2'3'-cyclic GMP-AMP (2'3'-cGAMP) synthesis, which found the biocatalytic route to be superior to the chemical synthesis in all considered environmental categories by at least an order of magnitude [4]. Conducting such assessments at an early development stage, when the choice between synthetic routes is still flexible, provides the greatest opportunity to minimize the ultimate environmental footprint of a product [4].

The ISO 14040/14044 Framework: A Four-Phase Approach

The ISO 14040 and 14044 standards establish a robust, four-phase structure for performing an LCA. This structured approach ensures the assessment is comprehensive, methodologically sound, and its results are interpretable and trustworthy [2] [1]. The following diagram visualizes this iterative framework and the key activities within each phase.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The first phase forms the critical foundation of the entire LCA study. The goal must unambiguously state the intended application, the reasons for carrying out the study, and the intended audience [5] [1]. The scope defines the breadth and depth of the study by specifying the product system, its functional unit—a quantified measure of the system's performance [1]—and the system boundaries that determine which processes are included [5]. For a cradle-to-grave assessment, these boundaries encompass raw material acquisition, processing, manufacturing, distribution, use, and end-of-life management [3]. Clearly outlining what is included and excluded at this stage prevents ambiguity and ensures consistency throughout the assessment [5].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory Analysis (LCI)

The Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) phase is the data collection engine of the LCA. It involves compiling a detailed account of all relevant energy and material inputs (e.g., raw materials, energy) and environmental outputs (e.g., emissions to air, water, and solid waste) throughout the product's life cycle [5] [1]. Data quality is paramount; primary data collected directly from suppliers and operational processes is considered the gold standard [3]. When primary data is unavailable, secondary data from reputable sources like government repositories, industry databases, or peer-reviewed studies can be used, though these sources must be meticulously documented [3]. Transparent documentation of data sources, calculations, and assumptions is mandatory for the study's credibility and regulatory compliance [5].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

The Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA) phase translates the inventory data into meaningful environmental impact metrics. In this phase, the inputs and outputs from the LCI are assigned to selected impact categories (e.g., global warming potential, eutrophication, resource depletion) and modeled using characterization factors to quantify their contributions [5]. For example, greenhouse gases are aggregated and expressed as kilograms of CO₂-equivalents [5]. It is a best practice to avoid focusing on a single metric and instead select multiple impact categories that matter most to the business and stakeholders, providing a nuanced understanding of the product’s environmental profile and avoiding problem-shifting [3].

Phase 4: Life Cycle Interpretation

In the final phase, the findings from the LCI and LCIA are evaluated and synthesized. The aim is to identify significant environmental issues, known as hotspots, check the completeness and sensitivity of the data, and draw conclusions and recommendations consistent with the defined goal and scope [5] [1]. This stage often involves sensitivity analysis to test how the LCA results change when key parameters or assumptions are varied, which helps understand the reliability of the results and identifies the most influential factors affecting the environmental performance [3]. The interpretation should be documented clearly, highlighting major impacts, limitations, and actionable insights for environmental improvement [5].

LCA in Practice: Biocatalytic vs. Chemical Synthesis

A comparative LCA study provides a powerful, real-world illustration of the framework's application in pharmaceutical research, specifically for synthesizing 2'3'-cyclic GMP-AMP (2'3'-cGAMP), a cyclic dinucleotide of interest for cancer immunotherapy [4].

Experimental Protocol and Methodology

The study compared the environmental impacts of biocatalytic and chemical catalytic synthesis routes for producing 200 g of 2'3'-cGAMP, using laboratory-scale data [4]. The methodology adhered to the ISO standard LCA framework.

- Goal and Scope: The goal was to determine the more sustainable production route at an early development stage. The scope was a cradle-to-gate assessment, covering from raw material extraction to the production of the final 200 g product [4].

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): The researchers meticulously collected data on all material and energy inputs (e.g., solvents, reagents, electricity) and emission outputs for both synthesis routes based on laboratory experiments [4].

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): The inventory data was translated into environmental impacts using several standard categories, including global warming potential (GWP). The results for the two routes were calculated and compared for each category [4].

Comparative Environmental Impact Data

The quantitative results from the LCA study are summarized in the table below, which allows for a direct, data-driven comparison of the two synthesis routes.

Table 1: Comparative LCA Results for 200g 2'3'-cGAMP Synthesis [4]

| Impact Category | Unit | Biocatalytic Synthesis | Chemical Synthesis | Ratio (Chemical/Biocatalytic) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (GWP) | kg CO₂ equiv. | 3,055.6 | 56,454.0 | ~18 times higher |

| Other Impact Categories | Various | Lower in all categories | Higher in all categories | At least 10 times higher |

Interpretation and Actionable Insights

The interpretation of the data is clear: the biocatalytic synthesis route was superior to the chemical route in every considered environmental impact category [4]. The most striking finding was the global warming potential, where the chemical route had an impact approximately 18 times greater than the enzymatic route [4]. This significant disparity underscores the value of early-stage LCA in guiding sustainable process development. By identifying the environmental hotspots and quantifying the dramatic difference between the two pathways, the study provides actionable insights for drug development professionals, enabling them to make data-driven decisions that align with broader sustainability goals at a point in the R&D pipeline where changes are most feasible [4].

Conducting a rigorous LCA requires specialized tools for data management, impact calculation, and analysis. The complexity of LCAs makes software essential for automating calculations, ensuring consistency, and providing access to robust, standardized datasets [3]. The following table details key research reagent solutions and software tools that facilitate streamlined LCA formatting and compliance with international standards.

Table 2: Key Tools and Software for LCA Research

| Tool / Software | Type / Category | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| SimaPro | LCA Software | Robust analytics and precise impact assessments for detailed Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) [5]. |

| GaBi Software | LCA Software | Designed for complex supply chain evaluations and precise carbon footprint analyses [5]. |

| OpenLCA | LCA Software | Free, open-source platform with comprehensive modeling and extensive database integration [5]. |

| Primary Data | Data Source | Data collected directly from operational processes and suppliers; considered the gold standard for LCI [3]. |

| Secondary Data | Data Source | Data from industry databases or literature; used to fill gaps when primary data is unavailable [3]. |

| Sensitivity Analysis | Analytical Method | Tests how LCA results change with varied parameters, assessing reliability and identifying key impact drivers [3]. |

The cradle-to-grave framework for Life Cycle Assessment, as defined by ISO 14040 and ISO 14044, provides an indispensable, standardized methodology for quantifying environmental impacts. For researchers and scientists in drug development, this structured approach—encompassing goal definition, inventory analysis, impact assessment, and interpretation—offers a powerful decision-support tool. The comparative case of 2'3'-cGAMP synthesis clearly demonstrates that strategic choices, such as selecting a biocatalytic over a chemical pathway, can reduce environmental impacts by orders of magnitude. Integrating LCA during early-stage research and development is therefore not merely a compliance exercise, but a critical practice for steering pharmaceutical innovation toward a more sustainable future.

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as an indispensable, standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of products and processes throughout their entire life cycle [6]. In the context of green chemistry, it provides the quantitative backbone for sustainable decision-making, moving beyond single metrics to offer a multi-dimensional view of environmental performance [6]. For researchers and drug development professionals comparing biocatalytic and chemical synthesis routes, LCA offers a science-based framework to validate sustainability claims, identify environmental "hotspots," and guide process innovation toward genuinely greener outcomes [6] [7]. The methodology is recognized worldwide by the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, ensuring robustness and consistency in its application [8].

This guide objectively examines the four core phases of LCA—Goal and Scope, Inventory Analysis, Impact Assessment, and Interpretation—with a specific focus on their application in comparing biocatalytic and chemical processes. It integrates experimental data and practical protocols to equip scientists with the tools needed to conduct rigorous, comparative assessments in their own research.

The Four Phases of Life Cycle Assessment

The LCA methodology is built upon four interconnected phases, as defined by ISO 14040/14044. The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and key interactions between these stages.

Phase 1: Goal and Scope Definition

The first phase establishes the foundation and boundaries of the study. The goal must clearly state the intended application, reasons for conducting the study, and the target audience. The scope defines the depth and breadth of the study, specifying the functional unit, system boundaries, and assumptions [6] [8].

- Functional Unit: This is a critical quantitative metric that allows for fair comparison between alternatives. For chemical processes, this is typically expressed as the environmental impact per unit of product (e.g., per 1 kg of an active pharmaceutical ingredient) [4] [9].

- System Boundaries: These define the processes included in the assessment. A cradle-to-gate approach (from raw material extraction to the factory gate) is often used for chemical intermediates, as their downstream use and end-of-life may be variable or identical for compared routes [9]. For a comprehensive analysis, a cradle-to-grave boundary (including use and disposal phases) is necessary [6].

- Approach Selection: The practitioner must also decide between an attributional LCA (describing the environmental impacts of a system as it is) or a consequential LCA (assessing the environmental consequences of a change within the system). The latter is more complex but powerful for decision-making [9].

Phase 2: Life Cycle Inventory (LCI)

The LCI phase is the most data-intensive stage, involving the compilation and quantification of all relevant inputs and outputs associated with the system boundaries [6]. For a comparative LCA of chemical processes, this includes:

- Energy consumption (electricity, heat, steam).

- Material inputs (feedstocks, catalysts, solvents, water).

- Emissions to air, water, and soil.

- Waste generation and by-products [6].

Data sources can include direct measurement from lab-scale or pilot-scale experiments, commercial databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi), and scientific literature. For novel biocatalytic or chemical processes at an early development stage, primary experimental data is crucial [10].

Phase 3: Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

In the LCIA phase, the inventory data is translated into potential environmental impacts using standardized metrics and characterization factors [6]. This step provides a more easily interpretable set of environmental profile indicators. Common impact categories include:

- Global Warming Potential (GWP): Expressed in kg of CO₂ equivalent.

- Eutrophication Potential: Measures water pollution from nutrient runoff.

- Acidification Potential.

- Human and Ecotoxicity.

- Resource Depletion [6].

This multi-category assessment helps avoid problem-shifting, where improving performance in one area inadvertently worsens another [6].

Phase 4: Interpretation

The final phase involves synthesizing the findings from the LCI and LCIA to draw conclusions, explain limitations, and provide actionable recommendations [6]. Key activities include:

- Identification of Hotspots: Pinpointing the life cycle stages or processes responsible for the greatest environmental impacts [7].

- Sensitivity and Uncertainty Analysis: Evaluating how variations in key data or assumptions affect the overall results, which is vital for robust conclusions [10] [9].

- Iterative Refinement: The interpretation phase often feeds back to the earlier phases, leading to a refinement of the goal, scope, or inventory data to improve the study's quality and usefulness [8].

Comparative LCA of Biocatalytic and Chemical Processes: Experimental Data

Comparative LCAs conducted at an early research stage can powerfully guide route selection. The following table summarizes quantitative findings from published LCA studies comparing biocatalytic and chemical synthesis for specific molecules.

Table 1: Comparative LCA Results for Biocatalytic vs. Chemical Synthesis

| Target Molecule | Synthesis Route | Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq) | Key Differentiating Factors | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2'3'-cGAMP (200 g) | Biocatalytic | 3,055.6 | 18 times lower GWP; superior in all impact categories. | [4] |

| Chemical | 56,454.0 | Poor reaction yield identified as major burden. | ||

| Lactones (per kg) | Biocatalytic (Baeyer-Villiger) | 1.65 ± 0.59 | Comparable climate change impact; solvent and enzyme recycling critical. | [10] |

| Chemical (Baeyer-Villiger) | 1.64 ± 0.67 | Impact reduced by 71% with renewable electricity. | ||

| Natural Product Glycosylation | Biocatalytic | Lower endpoint impacts | Lower titers and rates; superior yields. E-factor alone was misleading. | [11] |

| Chemical | Lower E-factor | Higher yields and rates; higher toxicity of reagents and solvents. |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative LCA

To generate the primary data required for a robust LCA, researchers must establish controlled experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines a generalized methodology for generating and using laboratory data in a comparative LCA.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Route Selection and Parallel Development: Select two or more synthetic routes (e.g., traditional chemical catalysis vs. enzymatic biocatalysis) to produce the same target molecule. Develop and optimize each route in parallel at a laboratory scale.

- Controlled Reaction and Data Recording: For each route, run the reaction in a controlled environment (e.g., a stirred-tank bioreactor for biocatalysis; a round-bottom flask with reflux for chemical synthesis). Record all inputs and outputs with high precision. Essential data points include:

- Inputs: Masses of all raw materials, catalysts, and enzymes; volumes of all solvents; energy consumption (e.g., electricity for stirring, heating, cooling, and pressure control; water for cooling).

- Outputs: Mass of the purified final product; masses of all by-products and waste streams.

- Downstream Processing: Include all downstream processing steps, such as extraction, purification (e.g., distillation, chromatography, crystallization), and drying. The energy and materials used in these steps often contribute significantly to the overall life cycle impact.

- Data Normalization: Normalize all collected data relative to the functional unit, for example, "per 1 kg of purified product." This normalized inventory is the direct input for the LCA model.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Model the LCA and perform sensitivity analyses on key parameters. For biocatalysis, this could include enzyme stability (total turnover number) and the number of reuses possible through immobilization [10]. For both routes, the source of electricity (e.g., grid mix vs. renewable) is a critical parameter to test [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials for LCA Studies

The following table details essential materials and their functions in conducting experiments for comparative LCA studies in biocatalysis and chemical synthesis.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Comparative LCA Experiments

| Item | Function in Experimental LCA | Relevance to LCA Inventory |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Enzymes | Biocatalysts for specific reactions (e.g., unspecific peroxygenases/UPOs, ATP-dependent enzymes). | Enzyme production is a key inventory item. Stability and reusability dramatically reduce environmental impact per kg of product [12]. |

| Cofactor Recycling Systems | Regenerates expensive cofactors (e.g., NADH, ATP) in situ for biocatalytic reactions. | Eliminates the need for stoichiometric cofactor addition, drastically reducing material consumption and waste [12]. |

| Immobilization Supports | Solid supports (e.g., resins, beads) for immobilizing enzymes or chemical catalysts. | Enables catalyst recovery and reuse across multiple reaction cycles, a major factor in improving process mass intensity [12]. |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Source of novel enzyme sequences for discovering new biocatalysts. | Discovery phase impact; influences the efficiency and specificity of the eventual industrial process [12]. |

| Green Solvents | Bio-based or less toxic solvents (e.g., Cyrene, 2-MeTHF). | Reduces toxicity impacts and can be derived from renewable resources, lowering the carbon footprint of the solvent inventory [6]. |

| Heterogeneous Chemical Catalysts | Solid catalysts that can be easily separated from the reaction mixture. | Similar to immobilization supports, allows for recycling and reduces metal leaching into waste streams, lowering resource depletion and toxicity impacts [9]. |

Discussion and Future Perspectives

The case studies presented demonstrate that the environmental superiority of biocatalytic over chemical processes is not a foregone conclusion; it is highly context-dependent. While biocatalysis can offer dramatic reductions in greenhouse gas emissions, as seen with 2'3'-cGAMP [4], it can also show nearly identical performance to chemical routes for other molecules, such as lactones [10]. This underscores the critical importance of using LCA rather than assumptions to guide sustainable process development.

A key insight from LCA is that traditional green chemistry metrics like E-factor (environmental factor) can sometimes be misleading. For natural product glycosylation, chemical synthesis had a lower E-factor, yet biocatalysis showed lower impacts on endpoint categories, highlighting that the nature of waste is as important as its quantity [11]. LCA's multi-impact perspective prevents such oversights.

Future advancements in LCA for chemical processes include:

- Prospective LCA (pLCA): This future-oriented approach integrates forecasting and scenario analysis to assess emerging technologies, accounting for expected changes in background systems like the decarbonization of the energy grid [13].

- Industry-Wide Assessments: Moving beyond individual products, industry-wide LCA models can optimize a basket of chemical products simultaneously, avoiding suboptimal decisions that occur when products are assessed in isolation [14].

- Integration of AI and Machine Learning: These tools are being used to predict enzyme function and optimize processes, shortening development timelines and reducing resource-intensive experimentation, which in turn lowers the environmental footprint of R&D [12].

For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering the four core phases of LCA is no longer a niche skill but a essential component of responsible innovation. This guide provides a framework for conducting rigorous comparative assessments between biocatalytic and chemical processes. By defining a clear goal and scope, collecting high-quality inventory data from well-designed experiments, assessing a comprehensive set of environmental impacts, and critically interpreting the results, scientists can make informed, data-driven decisions that genuinely advance the goals of green chemistry and sustainable pharmaceuticals.

Catalysis is a fundamental pillar of modern chemical synthesis, particularly in the pharmaceutical industry where it enables the practical and commercial-scale production of increasingly complex small-molecule active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs). This process is vital for developing cost-efficient, atom-economical methods that minimize environmental impact, aligning with green chemistry principles [15]. Two primary catalytic technologies—biocatalysis and chemical catalysis—have emerged as complementary yet distinct approaches. Biocatalysis utilizes natural catalysts, such as enzymes or whole cells, to speed up chemical transformations. In contrast, chemical catalysis predominantly relies on transition metal complexes to mediate asymmetric transformations, forming multiple bonds and chiral centres in a single step [15] [16]. The choice between these methodologies depends on multiple factors, including the complexity of the molecular structure, the stage of development, and the desired environmental footprint [15]. Within the context of life cycle assessment research, understanding the core concepts, advantages, limitations, and specific performance metrics of each approach is crucial for selecting the most sustainable and efficient process for a given application. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two catalytic strategies, supported by experimental data and standardized protocols for evaluation.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanistic Differences

The core distinction between biocatalysis and chemical catalysis originates from the nature of the catalyst itself, which dictates the mechanism, operating conditions, and resultant selectivity of the chemical transformation.

Biocatalysis: Enzyme-Driven Specificity

Biocatalysis harnesses the power of biological catalysts, primarily enzymes, which are proteins that accelerate chemical reactions within biological systems. The active site of an enzyme is a precisely structured pocket that positions the substrate for catalysis via a network of amino acid residues. This network exploits weak interactions—hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, dipole–dipole, and van der Waals forces—to constrain the substrate in a favourable conformation, stabilizing the transition state and significantly lowering the activation energy barrier [17]. This intricate architecture results in unparalleled rate accelerations and exceptional levels of selectivity. Enzymes typically function under mild or biological conditions (e.g., moderate temperatures and pH, often in water), which helps minimize unwanted side-reactions like decomposition, isomerization, and racemization that often plague traditional chemical methods [15] [16]. A key advantage of biocatalysts is their inherent chirality, as they are composed of L-amino acids. This makes them ideal for producing enantiopure compounds, as they can distinguish between chiral centres in a substrate, a critical requirement for pharmaceutical synthesis [15] [16].

Chemical Catalysis: Transition Metal-Mediated Versatility

Chemical catalysis, particularly homogeneous transition metal catalysis, employs metal complexes (often with chiral ligands) to facilitate reactions. Unlike the complex three-dimensional pocket of an enzyme, the active site of a chemocatalyst is the metal centre, which activates substrates through coordination. The surrounding organic ligands, which can be designed and optimized through synthetic chemistry, impart steric and electronic influences that guide the reactivity and selectivity of the process [15]. These catalysts are often highly versatile and can mediate a wide array of transformations that are challenging for enzymes, such as asymmetric hydrogenation, Jacobsen epoxidation, Buchwald-Hartwig amination, and Suzuki cross-coupling reactions [15]. However, they frequently require harsh conditions (e.g., high temperatures and pressures, organic solvents) and can be sensitive to air and moisture. A significant consideration is the frequent use of precious and sometimes toxic metals, which raises concerns about cost, supply, and environmental impact [15].

Table 1: Core Characteristics and Mechanistic Differences

| Feature | Biocatalysis | Chemical Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Catalyst Type | Enzymes (proteins) or whole cells [16] | Transition metal complexes (e.g., with Rh, Pd, Ru) [15] |

| Active Site | Complex 3D pocket of amino acids [17] | Metal centre with organic ligands [15] |

| Typical Solvent | Often water or aqueous buffers [15] | Mostly organic solvents [15] |

| Typical Conditions | Mild (20-40°C, neutral pH) [16] | Can be harsh (elevated T/P, strong acids/bases) [15] |

| Selectivity Origin | Precisely defined binding pocket [17] | Chiral ligand environment around the metal [15] |

| Metal Content | Metal-free [15] | Relies on precious/toxic metals [15] |

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for a comparative assessment of these two catalytic strategies, which is essential for a life cycle assessment study.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Evaluating catalyst performance requires a multi-faceted approach, as no single metric can fully capture the economic and environmental potential for industrial application. Key performance indicators must be measured under relevant process conditions to enable a fair comparison [18].

Standardized Performance Metrics

For any catalytic process, especially when benchmarking for life cycle assessment, three core metrics are essential for assessing scalability: achievable product concentration (titer), productivity (rate), and catalyst stability [18]. While yield is a common report, high yield alone does not guarantee a viable industrial process if the product concentration is too low (increasing downstream costs) or the catalyst degrades too quickly. The Environmental Factor (E-factor), defined as the total mass of waste produced per mass of product, is a crucial green chemistry metric, though it should be noted that it does not always fully capture the environmental impact of a process, as the nature of the waste is also critical [19].

Table 2: Key Performance and Environmental Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Importance for Scale-Up |

|---|---|---|

| Titer (mM) | Moles of product per liter of reaction volume [19] | Determines reactor size and downstream purification costs [18] |

| Yield (%) | Moles of product per moles of substrate [19] | Measures atom economy and raw material efficiency [19] |

| Rate (mM·h⁻¹) | Product concentration achieved per unit time [19] | Impacts reactor throughput and capital costs [18] |

| E-Factor | Total mass of waste / mass of product [19] | Quantifies process waste generation and environmental footprint [19] |

| Operational Stability | Total turnover number (TTN) or catalyst lifetime [18] | Determines catalyst consumption and contribution to cost of goods [18] |

Comparative Experimental Data

A critical analysis of published data, particularly for natural product glycosylation reactions, reveals a complex performance landscape. The following table synthesizes experimental outcomes from the literature, highlighting the trade-offs between different catalytic systems [19].

Table 3: Experimental Performance Data for Glycosylation Reactions

| Catalytic Method | Typical Yield (%) | Typical Titer (mM) | Typical Rate (mM·h⁻¹) | Reported E-Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Glycosylation | Moderate to High | High | High | Lower [19] |

| Example: Radical-mediated | ||||

| In Vitro Biocatalysis | High | Lower | Lower | Higher [19] |

| Example: Enzyme cascade | ||||

| In Vivo Biocatalysis | High | Variable | Variable | Data Limited [19] |

| Example: Whole-cell |

This data challenges the assumption that biocatalysis is universally "greener." While chemical glycosylation often exhibits a lower E-factor (less mass of waste), a full life cycle impact assessment using the ReCiPe 2016 endpoint methodology showed that biocatalytic approaches can have lower impacts on endpoint categories like ecosystem quality and human health [19]. This underscores that E-factor alone is an insufficient metric for environmental impact and a more comprehensive life cycle assessment is necessary.

Experimental Protocols for Catalyst Evaluation

To generate comparable and reliable data for life cycle assessment, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following sections outline detailed methodologies for evaluating the performance of both biocatalysts and chemocatalysts.

Protocol for Biocatalyst Performance Measurement

This protocol is designed to measure the key metrics of activity, stability, and selectivity for an enzymatic reaction [18].

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare the reaction in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50-100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0-7.5) unless a specific pH optimum is known.

- Use substrate concentrations significantly above the reported KM value to ensure the enzyme operates at maximum velocity (Vmax) conditions. For poorly soluble substrates, introduce a cosolvent (e.g., 5-20% DMSO) or a second organic phase.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the enzyme (crude lysate, purified, or immobilized) and incubate at the specified temperature (e.g., 30°C) with constant agitation.

Activity and Productivity Measurement:

- Withdraw samples at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes).

- Quench the samples immediately (e.g., by acidification or heat denaturation) and analyze the product formation using a calibrated method like HPLC or GC.

- Calculate the initial rate (mM·h⁻¹) from the linear portion of the progress curve. Determine the titer (mM) from the final sample and the yield (%) based on the initial substrate concentration.

Operational Stability Assessment:

- For immobilized or recyclable enzymes, run the reaction for a fixed period (e.g., 4-8 hours).

- Recover the biocatalyst by centrifugation or filtration.

- Wash the catalyst and reintroduce it into a fresh reaction mixture.

- Repeat this process over multiple batches, measuring the activity in each cycle. The total turnover number (TTN) or the number of cycles before 50% activity loss are key stability metrics [18].

Protocol for Chemocatalyst Performance Measurement

This protocol is adapted for a homogeneous transition metal-catalyzed reaction, such as an asymmetric hydrogenation [15].

Reaction Setup:

- Conduct reactions in an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon glovebox) using anhydrous solvents to prevent catalyst decomposition.

- Charge a pressure tube or autoclave with the substrate, catalyst (metal-ligand complex), and solvent.

- Seal the vessel and pressurize with the reactive gas (e.g., H₂ for hydrogenation).

- Place the vessel in a heated block or oil bath at the required temperature with vigorous stirring.

Reaction Monitoring and Analysis:

- After the specified reaction time, cool the vessel and carefully release the pressure.

- Quench the reaction if necessary and take an aliquot for analysis.

- Analyze conversion and enantiomeric excess (e.e.) using chiral HPLC or GC.

- Calculate the yield (%) and turnover frequency (TOF). The catalyst loading (mol%) is a critical parameter for economic calculation.

E-Factor Calculation:

- After the reaction is complete, isolate the product using a standard workup procedure (e.g., extraction, filtration, evaporation).

- Record the masses of all materials used (substrate, catalyst, solvent, workup materials) and the mass of the isolated product.

- Calculate the E-Factor using the formula: E-Factor = (Total mass of inputs - Mass of product) / Mass of product [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The development and optimization of both biocatalytic and chemocatalytic processes rely on a suite of specialized reagents, materials, and analytical tools.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Description | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Chiral Ligand Kits | Libraries of structurally diverse chiral ligands (e.g., BINAP, DuPhos) [15] | Screening for optimal enantioselectivity in chemocatalytic reactions [15] |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enzymes covalently or physically bound to solid supports (e.g., EziG carriers) | Enables biocatalyst recycling, improves stability, and facilitates use in flow reactors [18] |

| Engineered Whole Cells | Microbial hosts (e.g., E. coli, yeast) expressing recombinant enzymes or biosynthetic pathways [20] | Used for in vivo biocatalysis and de novo synthesis of complex molecules [20] |

| Non-Natural Cofactors | Synthetic analogs of natural enzyme cofactors (e.g., NADPH) | Can alter enzyme reactivity or enable non-natural transformations [16] |

| High-Throughput Screening Systems | Automated platforms for parallel reaction set-up and analysis (e.g., using HPLC-MS or colorimetric assays) [20] | Essential for rapid testing of enzyme variants or catalytic conditions during optimization [20] [17] |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Collections of genetic material sourced directly from environmental samples [20] | A resource for discovering novel biocatalysts with unique activities from uncultured microorganisms [20] |

Biocatalysis and chemical catalysis are not competing technologies but rather complementary tools in the synthetic chemist's arsenal. Biocatalysis excels in its unparalleled selectivity and ability to function under mild, environmentally benign conditions, often using water as a solvent and producing minimal heavy metal waste. Its main challenges historically were a limited reaction scope and the need for time-consuming enzyme engineering, though advances in bioinformatics and directed evolution are rapidly closing these gaps [15] [20] [17]. Chemical catalysis offers unparalleled versatility and a vast toolbox of well-established reactions capable of achieving high titers and productivities, though often at the cost of harsher conditions and a higher environmental burden from solvents and metals [15]. The choice between them is not abstract but depends on the specific transformation, the stage of the product's lifecycle, and the capabilities of the manufacturer. A definitive assessment of their relative sustainability requires a sophisticated life cycle assessment that moves beyond simple metrics like E-factor to include endpoint impacts on human health and ecosystem quality [19]. For researchers, the future lies in leveraging the strengths of both—for instance, by designing hybrid chemoenzymatic cascades—to develop efficient, cost-effective, and truly sustainable synthetic routes for the pharmaceutical and fine chemical industries.

The Role of LCA in the EU Chemical Strategy for Sustainability and Safe-and-Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD)

The European Union's Chemical Strategy for Sustainability (CSS) represents a fundamental component of the European Green Deal, aiming to transform the chemical industry into a safe, climate-neutral, and resource-efficient sector [21] [22]. A cornerstone of this strategy is the Safe and Sustainable by Design (SSbD) framework, a voluntary approach designed to integrate safety, circularity, and sustainability considerations throughout the life cycle of chemicals and materials from the earliest development stages [23] [21]. Within this framework, Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) emerges as a critical methodological tool for providing a comprehensive, quantitative evaluation of environmental impacts, thereby enabling informed decision-making that avoids problem-shifting between life cycle stages or environmental impact categories [21] [24]. This article examines the application of LCA in comparing biocatalytic and chemical synthesis processes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured experimental data and protocols to guide sustainable process selection.

LCA Fundamentals and the SSbD Framework

Core Principles of Life Cycle Assessment

Life Cycle Assessment is a systematic methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction ("cradle") to waste treatment ("grave") [24]. The standardized LCA framework, as defined by ISO 14040 standards, comprises four iterative phases:

- Goal and Scope Definition: Specifies the study's purpose, system boundaries, and functional unit, which provides a quantitative basis for comparing alternatives [24].

- Life Cycle Inventory (LCI): Involves the compilation and quantification of all energy, material inputs, and environmental releases throughout the product life cycle [24].

- Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA): Evaluates the potential environmental impacts based on the LCI results, using categorized indicators such as global warming potential or eutrophication potential [24].

- Interpretation: Systematically evaluates the results, checks sensitivity, and draws conclusions based on the findings from the previous phases [24].

Integration of LCA within the SSbD Framework

The integration of LCA within the SSbD framework enables a multidisciplinary assessment that combines expertise from chemistry, chemical engineering, toxicology, ecotoxicology, and sustainability sciences [21] [25]. This approach facilitates early-stage evaluation of novel chemicals and synthesis processes, aligning with the CSS's key action to "boost investment and innovative capacity for the production and use of chemicals that are safe and sustainable by design throughout their lifecycle" [22]. The EU's strategy recognizes that shifting toward chemicals and production technologies requiring less energy is essential for limiting emissions and achieving the Green Deal's objectives [22].

Table: Core Components of LCA within the SSbD Framework

| LCA Phase | SSbD Integration | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Goal & Scope | Defines system boundaries for safety & sustainability | Ensures assessment covers human health, ecosystem impacts, and resource use |

| Life Cycle Inventory | Provides data on material/energy flows | Identifies hotspots in chemical production processes |

| Impact Assessment | Evaluates multiple environmental impact categories | Enables comparison of process alternatives (e.g., biocatalytic vs. chemical) |

| Interpretation | Supports decision-making for sustainable innovation | Guides early-stage R&D toward safer, more sustainable pathways |

Comparative LCA of Biocatalytic vs. Chemical Synthesis: A Case Study of 2'3'-cGAMP

Experimental Protocol for Comparative LCA

A 2023 comparative LCA study exemplifies the rigorous application of this methodology to pharmaceutical synthesis, specifically for the cyclic dinucleotide 2'3'-cyclic GMP-AMP (2'3'-cGAMP), a molecule of interest for cancer immunotherapy [4]. The experimental protocol followed these key stages:

1. Goal and Scope Definition

- Objective: Quantitatively compare the environmental impacts of chemical and biocatalytic synthesis routes for 2'3'-cGAMP at an early development stage.

- Functional Unit: Production of 200 g of 2'3'-cGAMP.

- System Boundaries: Included all material and energy inputs from raw material extraction through synthesis process operations.

2. Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Compilation

- Data Sources: Laboratory-scale experimental data for both synthesis routes.

- Key Parameters: Reaction yields, energy consumption, solvent use, catalyst requirements, and intermediate production.

- Allocation Methods: Mass-based allocation for multi-output processes.

3. Life Cycle Impact Assessment (LCIA)

- Impact Categories: Global warming potential (kg CO₂ equivalent), along with other relevant environmental impact indicators.

- Characterization Models: Standardized models (e.g., IPCC for climate change) to convert inventory data into impact category indicators.

4. Interpretation

- Hotspot Analysis: Identification of process steps with the highest environmental contributions.

- Sensitivity Analysis: Evaluation of how uncertainties in the data affect the overall results.

- Comparative Assertion: Transparent comparison of the two synthesis routes across all impact categories.

Quantitative Results and Comparative Analysis

The LCA results demonstrated a striking environmental advantage for the biocatalytic synthesis route across all impact categories [4]. The data reveal that the biocatalytic process generates significantly lower environmental impacts, particularly for global warming potential where it shows an 18-fold advantage over the chemical synthesis route.

Table: Environmental Impact Comparison for 200g 2'3'-cGAMP Production [4]

| Impact Category | Biocatalytic Synthesis | Chemical Synthesis | Advantage Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq.) | 3,055.6 | 56,454.0 | 18:1 |

| Additional Impact Categories | Significantly lower in all categories | Higher in all categories | At least 10:1 |

The substantially poorer yield associated with chemical synthesis was identified as a primary driver for its elevated environmental footprint, while the biocatalytic route benefited from higher selectivity and milder reaction conditions [4]. This case study underscores the value of conducting LCA at early development stages when process modifications are still feasible, enabling researchers to select the most sustainable pathway before significant resources are committed.

LCA Methodology Workflow: This diagram illustrates the systematic stages of Life Cycle Assessment, from initial goal definition through to sustainable process selection, as applied to comparing chemical synthesis routes.

Advanced LCA Applications in Sustainable Chemical Development

Expanding LCA Beyond Conventional Boundaries

The application of LCA within SSbD is evolving beyond traditional environmental impacts to incorporate chemical footprinting and hazard assessment [21]. Research programs like Mistra SafeChem are developing integrated approaches that combine LCA with:

- In silico hazard screening tools using advanced machine learning and AI-based methods to predict human and ecosystem effects, including mutagenesis, endocrine disruption, and ecotoxicity [21] [25].

- Analytical exposure screening workflows that enable time-efficient assessment of a broad range of chemical classes throughout the product life cycle [25].

- Social and economic dimensions through Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), which integrates environmental, social, and economic indicators in line with the UN Sustainable Development Goals [26].

LCA of Waste-Derived Catalysts and Circular Systems

Emerging research applies LCA to evaluate the sustainability of circular economy approaches in chemical production, particularly the synthesis of heterogeneous catalysts from waste materials [26]. Studies compare conventional catalyst production with innovative routes utilizing:

- Biodegradable waste streams (e.g., eggshells-derived calcium oxide, fruit peel biochar)

- Non-biodegradable waste (e.g., waste oils, industrial sludges)

- Process intensification strategies (e.g., ultrasound-assisted synthesis, microwave reactors)

These LCAs commonly employ the "Recovery-Regeneration-Reusability (RRR)" system boundary to quantify the net environmental benefits of waste valorization, often revealing significant reductions in resource consumption and global warming potential compared to conventional catalysts [26]. The integration of green chemistry principles—such as atom economy, energy efficiency, and waste minimization—further strengthens the LCA framework for assessing circular systems [26].

SSbD Assessment Integration: The Safe and Sustainable by Design framework integrates chemical safety, life cycle assessment, and circularity considerations to develop a comprehensive sustainability profile.

Essential Research Toolkit for LCA Implementation

Successful implementation of LCA for chemical process evaluation requires specialized tools and resources. The following table summarizes key solutions relevant to researchers assessing biocatalytic and chemical synthesis routes.

Table: Research Toolkit for LCA of Chemical Processes

| Tool/Resource | Function/Application | Relevance to SSbD |

|---|---|---|

| In Silico Hazard Tools | Computational prediction of human & ecological toxicity using QSAR and machine learning | Early-stage hazard screening for novel chemicals before synthesis [21] |

| Conformal Prediction Theory | Provides uncertainty parameters and applicability domains for computational models | Enhances reliability of early-stage assessments when experimental data is limited [25] |

| Life Cycle Inventory Databases | Comprehensive data on energy, material & chemical production impacts | Essential background data for LCA of chemical processes [24] |

| Analytical Exposure Screening | High-throughput analysis of chemical exposures in complex matrices | Assesses exposure potential throughout chemical life cycle [25] |

| Chemical Footprinting Methods | Quantifies impacts of chemical emissions on ecosystem & human health | Complements traditional LCA impact categories for chemical-specific assessments [21] |

The integration of Life Cycle Assessment within the EU's Chemical Strategy for Sustainability and the SSbD framework provides a robust scientific foundation for transitioning toward a safer, more sustainable chemical industry. The comparative case study of 2'3'-cGAMP synthesis demonstrates that biocatalytic routes can offer substantial environmental advantages over traditional chemical synthesis, particularly in reducing global warming potential and other impact categories by at least an order of magnitude [4].

For researchers and drug development professionals, the implementation of standardized LCA protocols at early R&D stages enables evidence-based decisions that align with EU sustainability objectives. Future developments in LCA methodology will likely focus on:

- Enhanced integration of hazard and risk assessment within life cycle impact assessment methods [21]

- Standardized approaches for evaluating "cocktail effects" of chemical mixtures throughout product life cycles [22]

- Advanced dynamic modeling to better represent temporal and spatial variations in chemical impacts [26]

- Harmonized digital tools to support the "one substance, one assessment" approach advocated in the CSS [22]

As the chemical industry faces increasing demands to contribute to climate neutrality and chemical safety, LCA emerges as an indispensable tool for quantifying progress, guiding innovation, and achieving the integrated safety and sustainability goals of the European Green Deal.

The pharmaceutical industry faces a critical challenge: its vital role in human health is accompanied by a significant environmental footprint. The sector accounts for approximately 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions and generates over 400,000 tons of waste annually, with around 20% classified as hazardous [27]. These environmental impacts originate from resource-intensive manufacturing processes, particularly during the synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), where traditional chemical methods often prevail. A key metric for assessing environmental efficiency in API manufacturing is the Process Mass Intensity (PMI), which indicates the total mass of inputs (raw materials, solvents, reagents) required to produce a unit mass of the final product [28]. The widely used Environmental Factor (E factor), defined as the mass ratio of waste to product, further highlights this inefficiency, with higher E factors indicating poorer environmental performance [28].

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) has emerged as an indispensable tool for quantifying these impacts and guiding the industry toward sustainable solutions. Unlike simple metrics, LCA provides a comprehensive, cradle-to-grave analysis that evaluates multiple environmental impact categories, including global warming potential, water consumption, and ecotoxicity. This systematic approach is crucial for making informed decisions in drug development and manufacturing. By applying LCA, researchers and process engineers can objectively compare the environmental performance of different synthetic routes, such as traditional chemical synthesis versus emerging biocatalytic processes. This comparative analysis is fundamental to addressing the industry's high waste-to-product ratios and reducing its overall environmental footprint, ultimately aligning public health objectives with planetary health.

The Tool for Assessment: Fundamentals of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA)

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a standardized methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts associated with all stages of a product's life, from raw material extraction through materials processing, manufacture, distribution, use, repair and maintenance, to disposal or recycling. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) provides a framework for LCA in the ISO 14040 and 14044 standards, ensuring consistency and credibility in its application. In the pharmaceutical context, LCA moves beyond single metrics like E factor or PMI to provide a multi-dimensional environmental profile, capturing trade-offs and synergies between different impact categories that might be missed by simpler measures [28].

The practice of LCA involves four interconnected phases, as visualized below.

Figure 1: The Four Phases of Life Cycle Assessment According to ISO Standards

For pharmaceutical applications, the goal and scope definition phase precisely defines the system boundaries, typically employing a "cradle-to-gate" approach that encompasses everything from raw material acquisition to the finished API at the manufacturing plant gate. The life cycle inventory phase involves meticulous data collection on all energy and material inputs and environmental releases associated with the process. This data feeds into the life cycle impact assessment phase, where inputs and outputs are translated into potential environmental impacts across categories such as global warming potential, acidification, eutrophication, and water use. Finally, the interpretation phase analyzes results to support decision-making, often through comparative assessment of alternative processes.

The particular value of LCA in pharmaceutical manufacturing lies in its ability to identify environmental hotspots in complex synthetic pathways and to prevent burden shifting—where solving one environmental problem inadvertently creates another. Studies have demonstrated that LCA can identify environmental hotspots in pharmaceutical processes, leading to impact reductions of up to 30% through targeted optimizations [27]. Furthermore, with over 70% of pharmaceutical companies now reportedly using lifecycle assessments to reduce environmental impacts, LCA is becoming an integral part of corporate sustainability strategy within the sector [27].

Chemical Synthesis: The Conventional High-Impact Approach

Traditional chemical synthesis has long been the cornerstone of pharmaceutical manufacturing, but LCA studies consistently reveal its substantial environmental burden. Conventional API manufacturing is characterized by multi-step synthetic routes that frequently employ hazardous reagents, heavy metal catalysts, and volatile organic solvents. These processes typically operate under high temperature and pressure conditions, driving significant energy consumption and resulting in complex waste streams requiring specialized treatment [29]. The environmental impact is quantifiable: approximately 70% of APIs are still manufactured using processes classified as environmentally hazardous [27].

The core issue lies in the fundamental inefficiency of traditional synthetic chemistry. A typical chemical process for pharmaceutical intermediates might involve protection and deprotection steps, use stoichiometric quantities of reagents that generate inorganic salts as waste, and require energy-intensive purification techniques like chromatography and distillation. These factors collectively contribute to high PMI and E factors. The E factor for pharmaceutical manufacturing can range from 25 to over 100, meaning 25-100 kg of waste are generated per kg of product, dramatically higher than the petrochemical (approximately 0.1) or bulk chemical (1-5) industries [28].

An illuminating case study comes from a comparative LCA of 2',3'-cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP) synthesis, a cyclic dinucleotide of interest for cancer immunotherapy. The study compared traditional chemical synthesis with a biocatalytic alternative, with striking results. The chemical synthesis route exhibited a global warming potential of 56,454 kg CO₂ equivalent per 200g of product—approximately 18 times higher than the biocatalytic route [4]. This massive carbon footprint was accompanied by proportionally high impacts across other categories, including energy demand and resource depletion. The environmental performance was primarily driven by the poor atom economy of the chemical route and the high energy inputs required for reaction conditions and downstream purification.

Table 1: Environmental Impact Comparison of Chemical vs. Biocatalytic cGAMP Synthesis per 200g Product [4]

| Impact Category | Chemical Synthesis | Biocatalytic Synthesis | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq) | 56,454.0 | 3,055.6 | 94.6% |

| Resource Consumption | High | Low | Significant |

| Waste Generation | High | Low | Significant |

Beyond carbon emissions, traditional pharmaceutical synthesis creates problematic waste streams. Organic solvents—many halogenated—often constitute the largest mass input besides water and frequently escape into the atmosphere as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) or require energy-intensive incineration. Heavy metal catalysts like palladium and platinum, while effective, can leach into wastewater and pose toxicity concerns. The cumulative effect of these issues, when quantified through LCA, presents a compelling case for transitioning toward more sustainable manufacturing paradigms.

Biocatalysis: A Sustainable Alternative with Demonstrated Benefits

Biocatalysis utilizes natural catalysts, primarily enzymes or whole cells, to perform chemical transformations of synthetic interest. This approach presents a fundamentally different paradigm with inherent sustainability advantages, as confirmed by numerous LCA studies. Biocatalytic processes typically operate under mild reaction conditions (ambient temperature and pressure near neutral pH), significantly reducing energy demands compared to conventional approaches [29] [30]. Enzymes are also highly selective and efficient, enabling reactions with exceptional stereospecificity that minimize by-product formation and simplify purification—key factors in reducing the overall Process Mass Intensity [17].

The environmental superiority of biocatalysis is demonstrated in the previously mentioned LCA of cGAMP synthesis, where the biocatalytic route showed an 18-fold reduction in global warming potential compared to chemical synthesis [4]. This dramatic improvement stems from multiple factors: the elimination of harsh reagents, reduced purification demands, and the catalytic nature of enzymes, which are effective in small quantities and can often be recycled. Furthermore, enzymes are biodegradable and typically produced from renewable resources, avoiding the persistence concerns associated with metal catalysts and reducing dependence on petrochemical-derived inputs [29].

The application of green chemistry principles, including biocatalysis, in pharmaceutical manufacturing has demonstrated waste reduction of up to 50% [27]. The mechanistic basis for this improvement lies in the fundamental properties of enzymatic catalysis. Enzymes achieve their spectacular rate enhancements and selectivity through precise positioning of substrates in their active sites via multiple weak interactions, including hydrogen bonding, electrostatic, and van der Waals forces [17]. This molecular precision translates directly to improved atom economy—a measure of how efficiently starting materials are incorporated into the final product—with corresponding reductions in waste generation.

Table 2: Fundamental Process Characteristics: Chemical vs. Biocatalytic Synthesis [29]

| Process Characteristic | Traditional Chemical Synthesis | Biocatalytic Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Temperature | Often high (100-300°C) | Typically mild (20-60°C) |

| Pressure | Often high | Typically ambient |

| Solvent | Often organic, volatile, or toxic | Often water, sometimes milder organics |

| Catalyst | Metal complexes, strong acids/bases | Enzymes (catalytic, biodegradable) |

| Selectivity | Moderate, often requires protection groups | High inherent stereoselectivity |

| Waste Profile | High volume, often toxic byproducts | Lower volume, fewer toxic byproducts |

The implementation of biocatalysis extends beyond niche applications to established industrial processes. Notable examples include the biocatalytic synthesis of pregabalin and sitagliptin, where enzymatic steps replaced traditional chemistry, resulting in significant reductions in waste, energy consumption, and cost [28]. In the pregabalin process, a lipase-catalyzed resolution enabled a dramatic reduction in organic solvent use and eliminated the need for cryogenic conditions, while the sitagliptin process employed a transaminase to install the chiral amine center with exceptional enantioselectivity, replacing a metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation that required a rhodium-based catalyst and high pressure equipment [28]. These examples illustrate how LCA-verified biocatalytic processes can deliver both environmental and economic benefits.

Comparative LCA: Experimental Data and Protocols

Rigorous comparative Life Cycle Assessment provides the quantitative evidence base for evaluating the environmental performance of chemical versus biocatalytic pharmaceutical synthesis. The methodology for such comparisons requires standardized protocols to ensure fair and meaningful results. The foundational principle is equivalent functional unit comparison, typically defined as the production of a specified quantity (e.g., 1 kg) of the same target molecule with identical purity and quality specifications [4] [28].

Experimental Design for Comparative LCA

A robust comparative LCA follows a systematic experimental design, as outlined below.

Figure 2: Experimental Workflow for Comparative LCA in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

For the cGAMP case study, researchers conducted a prospective LCA at an early development stage, analyzing the production of 200g of product [4]. The system boundaries included all material and energy inputs from resource extraction, through manufacturing, to waste treatment. Data sources combined primary laboratory measurements of material and energy consumption with secondary data from commercial LCA databases for upstream processes (e.g., solvent production, energy generation). The impact assessment employed standardized methods such as ReCiPe or CML to calculate multiple environmental impact indicators, with global warming potential (kg CO₂ equivalent) serving as a key metric for comparison.

Key Experimental Protocols

The experimental protocols for generating LCA inventory data require meticulous execution:

Material Balance Determination: Precise quantification of all input materials (substrates, reagents, catalysts, solvents) and output materials (product, by-products, waste) for each synthetic step. This is typically performed at laboratory scale with subsequent scale-up modeling.

Energy Profiling: Comprehensive measurement of energy inputs for reaction heating/cooling, mixing, purification (distillation, chromatography), and solvent recovery. This includes both electrical and thermal energy requirements.

Solvent Recovery Analysis: Determination of solvent recycling efficiency through distillation or other recovery methods, as solvent production often constitutes a major environmental impact contributor.

Waste Treatment Modeling: Assessment of environmental impacts associated with waste treatment pathways, including incineration, biological treatment, and hazardous waste disposal.

Enzyme Production Inventory: For biocatalytic processes, inclusion of impacts from enzyme production via fermentation, including nutrient media, energy for sterilization and agitation, and downstream processing.

The cGAMP study exemplified this approach, revealing that the chemical synthesis required extensive purification and protection/deprotection steps, while the biocatalytic route achieved the transformation more directly with fewer steps and milder conditions [4]. The resulting data, summarized in Table 1, provided unambiguous environmental performance comparisons across multiple impact categories.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Implementing and assessing sustainable pharmaceutical synthesis requires specialized reagents, catalysts, and analytical tools. The following table details key research solutions essential for developing and evaluating biocatalytic processes and conducting Life Cycle Assessments.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Sustainable Pharma Development

| Research Solution | Function & Application | Sustainability Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Kits (IREDs, P450s, Transaminases) | Screening for specific biotransformations (e.g., amine synthesis, oxyfunctionalization) | Reduces development time; enables identification of biodegradable catalysts replacing heavy metals [28]. |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enzyme stabilization and reuse in batch or flow systems | Enhances process efficiency and reduces enzyme consumption, lowering production impacts [28]. |

| Bio-Based Solvents (Cyrene, 2-MeTHF) | Replacement of petroleum-derived, hazardous solvents (DMF, DCM) | Renewable feedstocks; reduced toxicity and improved biodegradability [29]. |

| LC-MS/MS Systems | Detection and quantification of pharmaceutical pollutants in environmental samples | Essential for assessing environmental fate and ecotoxicity of APIs and intermediates [31]. |

| LCA Software (SimaPro, GaBi) | Modeling material and energy flows to calculate environmental impacts | Standardized assessment enabling quantitative comparison of process alternatives [4] [28]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Platforms | Rapid evaluation of enzyme variants or reaction conditions | Accelerates development of optimized biocatalytic processes with improved efficiency [17]. |

| Renewable Substrates (Bio-Based Glycerol, Sugars) | Raw materials for fermentation or chemical synthesis | Reduces reliance on fossil fuels and decreases carbon footprint [29]. |

The integration of these tools enables a comprehensive approach to sustainable pharmaceutical process development. For instance, imine reductases (IREDs) have emerged as particularly valuable biocatalysts for synthesizing chiral amines—key structural motifs in many pharmaceuticals—with high enantioselectivity, eliminating the need for chiral auxiliaries or resolution agents [28]. When combined with bio-based solvents and implemented using high-throughput screening, these enzymes facilitate the creation of synthetic routes with significantly improved environmental profiles, which can be quantitatively verified through LCA software.

The application of Life Cycle Assessment in pharmaceutical manufacturing provides incontrovertible evidence of the environmental advantages of biocatalytic processes over traditional chemical synthesis. The documented 18-fold reduction in global warming potential for cGAMP synthesis through biocatalysis, along with significant reductions in resource consumption and waste generation, demonstrates a transformative opportunity for the industry [4]. With the pharmaceutical sector accounting for a notable portion of global carbon emissions and generating hundreds of thousands of tons of waste annually, the widespread adoption of LCA-guided process selection is not merely an academic exercise but an operational imperative [27].

The compelling quantitative data derived from comparative LCAs should inform strategic decisions at the earliest stages of process development. As demonstrated in the cGAMP case study, early-stage LCA application—when route selection is still flexible—can guide researchers toward more sustainable synthesis pathways before significant resources are committed [4]. This proactive approach aligns with the industry's growing sustainability commitments, with over 80% of pharmaceutical companies now implementing sustainability strategies and 60% setting targets to reduce carbon emissions by 2030 [27].

Future progress will require continued innovation in enzyme engineering, process intensification, and renewable energy integration to further diminish the environmental footprint of pharmaceuticals. As biocatalysis evolves through advanced engineering techniques like directed evolution and computational protein design [17], its application scope will expand, offering sustainable alternatives to an ever-wider range of chemical transformations. By embedding LCA into development workflows and prioritizing biocatalytic solutions where advantageous, the pharmaceutical industry can simultaneously advance human health and environmental sustainability, fulfilling its dual mission in the most comprehensive sense.

Implementing LCA in Pharmaceutical R&D: From Methodology to Practical Application

A rigorous Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) is fundamental for objectively evaluating the environmental performance of biocatalytic versus traditional chemical processes. The validity of the entire assessment hinges on two critical initial steps: the proper definition of the functional unit and the system boundaries. This guide provides a structured approach to ensure fair and scientifically sound comparisons.

The Cornerstones of Comparative LCA

The functional unit (FU) and system boundaries provide the foundation for any LCA, ensuring that comparisons are made on a fair and equivalent basis.

Functional Unit: The FU is a quantified description of the function performed by the product system, providing a reference to which all inputs and outputs are normalized. It answers the question, "What are we comparing?" [6]. In chemical synthesis, a common FU is a specified mass of the final product (e.g., 1 kg) that meets required purity standards [4] [32]. This ensures that the environmental impact of producing an equal amount of usable product is compared, regardless of differences in process yield or efficiency.

System Boundaries: System boundaries define which unit processes are included in the assessment. A cradle-to-gate boundary includes everything from raw material extraction (cradle) up to the factory gate where the final product is produced. This is commonly used for comparing industrial synthesis routes [32]. A cradle-to-grave boundary extends further to include the product's use phase and its end-of-life treatment (e.g., disposal or recycling) [6]. The choice between them depends on the LCA's goal; for comparing production methods, cradle-to-gate is often sufficient.

LCA Methodology Workflow

Experimental Protocols for Comparative LCA

Adhering to standardized protocols ensures the reliability and reproducibility of LCA studies. The following methodology, based on the ISO 14044 standard, provides a framework for comparing chemical and biocatalytic routes [32].

Goal and Scope Definition Protocol

- Objective: To compare the environmental impact of chemical (A) and biocatalytic (B) synthesis routes for a target molecule.

- Function: The synthesis and isolation of a specified quantity of product meeting predefined purity criteria.

- Functional Unit: 1 kilogram (kg) of final product, with a defined purity level (e.g., >99.0%).

- System Boundary: Cradle-to-gate, including the production of reactants, catalysts, solvents, and all energy inputs for the synthesis and purification stages. The use phase and end-of-life are excluded.

- Impact Categories: The assessment should include, at minimum, Global Warming Potential (GWP) in kg CO₂ equivalent, Eutrophication Potential, and a resource use indicator such as Cumulative Energy Demand (CED) [6].

Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Data Collection Protocol

Data should be primary, derived from laboratory or pilot-scale experiments, and can be supplemented by data from commercial databases (e.g., Ecoinvent, GaBi) for upstream processes [6] [32].

- Material Inputs: Precisely record the masses of all substrates, catalysts, solvents, and other chemicals used per functional unit.

- Energy Inputs: Monitor and record all direct energy consumption (e.g., electricity for stirring, heating, cooling, refrigeration) for each major process step.

- Outputs and Waste: Quantify the mass of the final product, all by-products, and waste streams generated, including solvents for purification. This data is used to calculate metrics like the E-factor (mass of waste per mass of product) [33] [32].

Quantitative Comparison of Synthesis Routes

The following tables synthesize experimental data from comparative LCA studies, illustrating how defined functional units and system boundaries enable objective evaluation.

Table 1: Environmental Impact Profile for 2'3'-cGAMP Synthesis (200 g)

This data, from a comparative LCA of a cyclic dinucleotide synthesis, demonstrates the profound impact that process choice can have on environmental performance [4].

| Impact Category | Biocatalytic Synthesis | Chemical Synthesis | Ratio (Chemical/Biocatalytic) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq.) | 3,055.6 | 56,454.0 | ~18x higher |

| Other Environmental Impacts | Lower in all categories | Higher in all categories | At least 10x higher |

Table 2: Process Metrics for Lactone Synthesis (per kg product)

This data from a prospective LCA of lactone production shows a more nuanced picture, where impact is closely tied to specific process parameters like energy source and recycling [32].

| Process Metric | Biocatalytic Route | Chemical Route |

|---|---|---|

| Global Warming Potential (kg CO₂ eq.) | 1.65 (±0.59) | 1.64 (±0.67) |

| Key Sensitivity Factors | • Electricity source (71% ↓ with renewables)• Enzyme & solvent recycling | • Type of chemical oxidant• Solvent recycling |

| E-Factor (kg waste/kg product) | Often below 10, sometimes <1 [33] | Typically 25 to over 100 [33] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

This table details essential materials used in the synthesis and assessment of chemical and biocatalytic processes.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for LCA Comparisons

| Item Name | Function / Relevance | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Baeyer-Villiger Monooxygenases (BVMOs) | Biocatalysts that use molecular oxygen for oxidation, replacing peracids [32]. | Enzymatic synthesis of lactones and other esters. |

| Chemical Oxidants (e.g., m-CPBA) | Traditional oxidant for chemical Baeyer-Villiger reactions; generates significant waste [32]. | Chemical synthesis route for lactones. |

| Immobilized Enzymes | Enzymes fixed to a solid support to enhance stability and enable reuse over multiple cycles [34] [33]. | Improving economic and environmental performance of biocatalysis. |

| Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) Databases | Sources of secondary data for upstream processes (e.g., energy generation, solvent production) [6]. | Modeling inputs that are not directly measured in lab-scale experiments. |

| In Silico Hazard Screening Tools | Computational models using QSAR and machine learning to predict human and ecological toxicity [25]. | Early-stage hazard assessment within an LCA or Safe & Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD) framework. |

LCA-Driven Process Development

Defining a precise functional unit and comprehensive, consistent system boundaries is the non-negotiable foundation for a fair LCA. As the data shows, this rigorous approach allows researchers to move beyond perceptions and quantify the true environmental trade-offs between chemical and biocatalytic synthesis, ultimately guiding the development of greener pharmaceutical manufacturing.

A Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) is a crucial component of Life Cycle Assessment (LCA), involving the systematic accounting of all material and energy inputs, products, and environmental releases associated with a product system throughout its life cycle. For the pharmaceutical industry, constructing accurate LCIs presents unique challenges due to complex multi-step syntheses of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) and limited data availability for specialized chemical precursors. The fundamental principle of LCI is to quantify all resource consumption and emission flows across defined system boundaries, which typically include cradle-to-gate (from raw material extraction to API production), gate-to-gate (focusing solely on manufacturing processes), or cradle-to-grave (including use phase and end-of-life) scenarios [35].

Pharmaceutical production generates more waste per unit of product than any other chemical sector, including oil refining and bulk chemical manufacturing [36]. This environmental burden stems from complex synthetic pathways with resource consumption and waste generation that are significantly high compared to the low amounts of final product obtained. The industry's traditional focus on economic considerations during route design and selection has expanded to include sustainability metrics, driving the adoption of LCA methodologies to evaluate environmental impacts holistically [37]. Life cycle assessment adds substantial value beyond traditional green chemistry metrics by providing nuanced insights through indicators that capture influences on human health, ecosystem quality, global warming potential, and natural resource depletion [37].

Methodological Frameworks for Pharmaceutical LCI

Standardized LCI Methodologies