Bridging the Annotation Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Computational Enzyme Predictions for Biomedical Research

The exponential growth of genomic data has far outpaced experimental characterization, leaving public databases rife with erroneous enzyme annotations that misdirect research and drug discovery.

Bridging the Annotation Gap: A Comprehensive Guide to Validating Computational Enzyme Predictions for Biomedical Research

Abstract

The exponential growth of genomic data has far outpaced experimental characterization, leaving public databases rife with erroneous enzyme annotations that misdirect research and drug discovery. This article provides a critical roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals to navigate this challenge. It explores the severe scope of the misannotation crisis, evaluates cutting-edge computational tools from machine learning to generative models, outlines robust experimental frameworks for validation, and establishes benchmarks for comparing methodological performance. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application and troubleshooting guidance, this resource aims to empower scientists to critically assess computational predictions and implement rigorous, integrated validation pipelines that enhance the reliability of enzymatic data in biomedical research.

The Misannotation Crisis: Unveiling the Scale of Erroneous Enzyme Annotations

Automated functional annotation based on sequence similarity is a fundamental practice in genomics, yet its inherent pitfalls pose a significant challenge to research and drug development. This guide provides an objective comparison of the primary annotation methods—automated sequence alignment and experimental validation—by synthesizing current data and experimental protocols. The analysis reveals that even high-confidence similarity thresholds can result in startlingly high error rates, with one study inferring a 78% misannotation rate within a specific enzyme class [1]. This article details the quantitative evidence of these errors, compares the performance of computational and experimental approaches, and provides a toolkit of validation protocols and reagents essential for researchers aiming to ensure the reliability of their functional annotations.

The exponential growth of genomic data has created a massive annotation gap. Public protein databases contain hundreds of millions of entries, but the proportion that has been experimentally characterized is vanishingly small—only about 0.3% of entries in the UniProt/TrEMBL database are manually annotated and reviewed [1]. To bridge this gap, researchers and databases heavily rely on automated annotation methods that transfer putative functions from characterized sequences to new ones based on statistical similarity [2]. While this approach enables the processing of data at scale, it carries a fundamental risk: the widespread propagation of errors when annotations are transferred without sufficient evidence or validation. This problem is particularly acute in the field of enzymology, where incorrect Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers can misdirect entire research projects, lead to flawed metabolic models, and ultimately hamper drug discovery efforts. This article objectively compares the current annotation landscape, providing researchers with the data and methodologies needed to critically assess functional predictions.

Quantitative Evidence of Widespread Misannotation

The scale of the misannotation problem is not merely theoretical; it is being rigorously documented through computational and experimental studies. The data presented below demonstrate that error rates are substantial, even when sequences share significant similarity.

Table 1: Documented Misannotation Rates in Enzymes

| Study Focus | Reported Misannotation Rate | Key Findings | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases (EC 1.1.3.15) | 78% (inferred from experiment) | Of 122 representative sequences tested, at least 78% were misannotated. Only 22.5% contained the expected protein domain. | [1] |

| General Enzyme Function Conservation | >70% | Less than 30% of enzyme pairs with >50% sequence identity had entirely identical EC numbers. Errors occurred even with BLAST E-values below 10⁻⁵⁰. | [3] |

| BRENDA Database Analysis | ~18% | Nearly 18% of all sequences in enzyme classes shared no similarity or domain architecture with experimentally characterized representatives. | [1] |

The experimental investigation into EC 1.1.3.15 revealed that the majority of misannotated sequences contained non-canonical protein domains entirely different from those in known, characterized S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases [1]. This indicates that simple similarity searches can connect sequences based on short, insignificant regions, leading to fundamentally incorrect functional assignments. Furthermore, the problem is self-perpetuating; as new sequences are annotated based on these erroneous entries, the misannotation spreads throughout databases [1].

Comparative Analysis: Automated Annotation vs. Experimental Validation

To understand the root of the problem, it is crucial to compare the methodologies and performance of automated annotation tools against the gold standard of experimental validation.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Annotation Methods

| Aspect | Automated Annotation (Sequence-Similarity Based) | Experimental Validation (High-Throughput Screening) |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput | Very High | Medium to High |

| Speed | Rapid (minutes to hours) | Slow (days to weeks) |

| Primary Methodology | Transfer of annotation via BLAST, PSI-BLAST, or tools like PANNZER2 based on sequence alignment [2] [4]. | Recombinant expression, purification, and in vitro activity assays [5] [1]. |

| Key Advantage | Enables annotation of massive datasets at low cost. | Provides direct, empirical evidence of function. |

| Key Limitation | Prone to error propagation; cannot confirm actual catalytic activity. | Lower throughput, requires specialized equipment and expertise. |

| Reliability for Critical Applications | Low to Moderate. Requires expert oversight and confirmation [6]. | High. Considered the benchmark for accuracy. |

| Handling of VUS (Variants of Uncertain Significance) | Performs poorly; tools show significant limitations with VUS interpretation [6]. | Essential for definitive classification. |

A core finding from recent evaluations of automated variant interpretation tools is that while they demonstrate high accuracy for clearly pathogenic or benign variants, they show significant limitations with variants of uncertain significance (VUS) [6]. This underscores that automation, while useful for clear-cut cases, struggles with the nuanced interpretations that often constitute the frontier of research. Expert oversight remains indispensable when using these tools in a clinical or research context [6].

Experimental Protocols for Validating Enzyme Function

To address annotation uncertainty, researchers must employ experimental validation. The following workflow and detailed protocol describe a robust method for high-throughput functional screening of putative enzymes.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol is adapted from high-throughput studies that successfully identified misannotation in enzyme classes [5] [1].

Step 1: Sequence Selection & Domain Architecture Analysis Select a diverse set of representative sequences from the enzyme class of interest, ensuring coverage of different taxonomic groups and similarity levels. In parallel, computationally analyze the Pfam domain architecture of each sequence. This pre-screen can immediately flag sequences lacking the critical catalytic domains found in experimentally characterized enzymes [1].

Step 2: Gene Cloning & Recombinant Expression Clone the genes into a suitable expression vector (e.g., pET series) and transform into an expression host like E. coli. A key consideration is sequence truncation: carefully define the boundaries of the mature protein to avoid removing essential regions (e.g., dimer interfaces) or including signal peptides that can interfere with heterologous expression, a noted pitfall in early screening rounds [5]. Induce protein expression and harvest the cells.

Step 3: Protein Purification Purify the recombinant proteins using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag purification). Assess the purity and concentration via SDS-PAGE and spectrophotometry. The goal is to obtain a purified, soluble protein fraction for testing.

Step 4: In Vitro Functional Assay Develop a specific, sensitive assay for the predicted catalytic activity. For oxidases like EC 1.1.3.15, this can be a spectrophotometric assay that measures the production of a colored product (e.g., a 2-oxoacid) over time [1]. Include appropriate controls:

- Negative Control: Assay buffer without the enzyme.

- Positive Control: A well-characterized enzyme with the same predicted activity. Test the purified proteins against the predicted substrate and, if possible, a panel of related substrates to check for potential alternative activities.

Step 5: Data Analysis & Validation An enzyme is considered "experimentally successful" if it can be expressed and folded in the host system and demonstrates activity significantly above background in the in vitro assay [5]. Sequences that fail this test are strong candidates for misannotation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful validation of enzyme function relies on a set of key reagents and computational tools. The following table details essential components for a functional annotation pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Annotation & Validation

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevance to Annotation Validation |

|---|---|---|

| pET Expression Vectors | High-level protein expression in E. coli. | Standardized system for recombinant production of uncharacterized sequences for functional testing. |

| Affinity Chromatography Resins (e.g., Ni-NTA) | Purification of recombinant His-tagged proteins. | Enables rapid purification of multiple putative enzymes for high-throughput activity screening. |

| Spectrophotometer / Microplate Reader | Kinetic measurement of enzyme activity. | Essential for running quantitative in vitro assays (e.g., measuring oxidation of substrates). |

| Phobius | Prediction of signal peptides and transmembrane domains. | Pre-experiment tool to prevent expression failures by ensuring correct sequence truncation [5]. |

| Pfam Database | Database of protein families and domains. | Critical for checking if a putatively annotated sequence contains the expected functional domains [1]. |

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme resource. | Source of known enzymatic reactions, substrates, and characterized sequences for positive controls and rule definition. |

| PANNZER2 / Blast2GO | Automated functional annotation tools. | Represents the class of tools whose predictions require experimental validation; useful for generating initial hypotheses [2] [4]. |

The reliance on automated, sequence-similarity-based annotation is an undeniable bottleneck in genomics, leading to a documented misannotation rate that can exceed 70% for some enzyme classes. As this comparison has shown, computational tools are powerful for generating hypotheses but are not a substitute for experimental validation, especially for variants of uncertain significance.

The future of accurate functional annotation lies in integrating robust computational methods with high-throughput experimental screening. Advances in AI and machine learning are beginning to incorporate multiple lines of evidence beyond simple sequence alignment, such as protein structure and genomic context, which may improve predictions [7]. Furthermore, the development of high-throughput experimental platforms makes it increasingly feasible to validate predictions on a family-wide scale [5] [1]. For researchers in drug development and basic science, a critical and evidence-based approach to functional annotations is not just best practice—it is a necessity to ensure the integrity and reproducibility of their work.

The exponential growth of genomic sequence data has vastly outpaced the capacity for experimental protein characterization, making computational annotation a cornerstone of modern biology. However, the reliability of these automated annotations remains a critical concern for researchers in basic science and drug development. As of 2024, the UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot database contains only 0.64% of manually annotated enzyme sequences amidst 43.48 million total enzyme sequences, creating substantial reliance on computational function transfer [8]. This dependency creates a propagation pipeline where initial misannotations perpetuate throughout databases, potentially compromising metabolic models, drug target identification, and engineering applications. A large-scale community-based assessment (CAFA) revealed that nearly 40% of computational enzyme annotations are erroneous [8], highlighting the systemic nature of this problem. This guide examines a definitive case study quantifying misannotation rates, explores experimental validation methodologies, and objectively compares computational tools that aim to address these critical challenges.

The EC 1.1.3.15 Case Study: Experimental Revelation of Widespread Misannotation

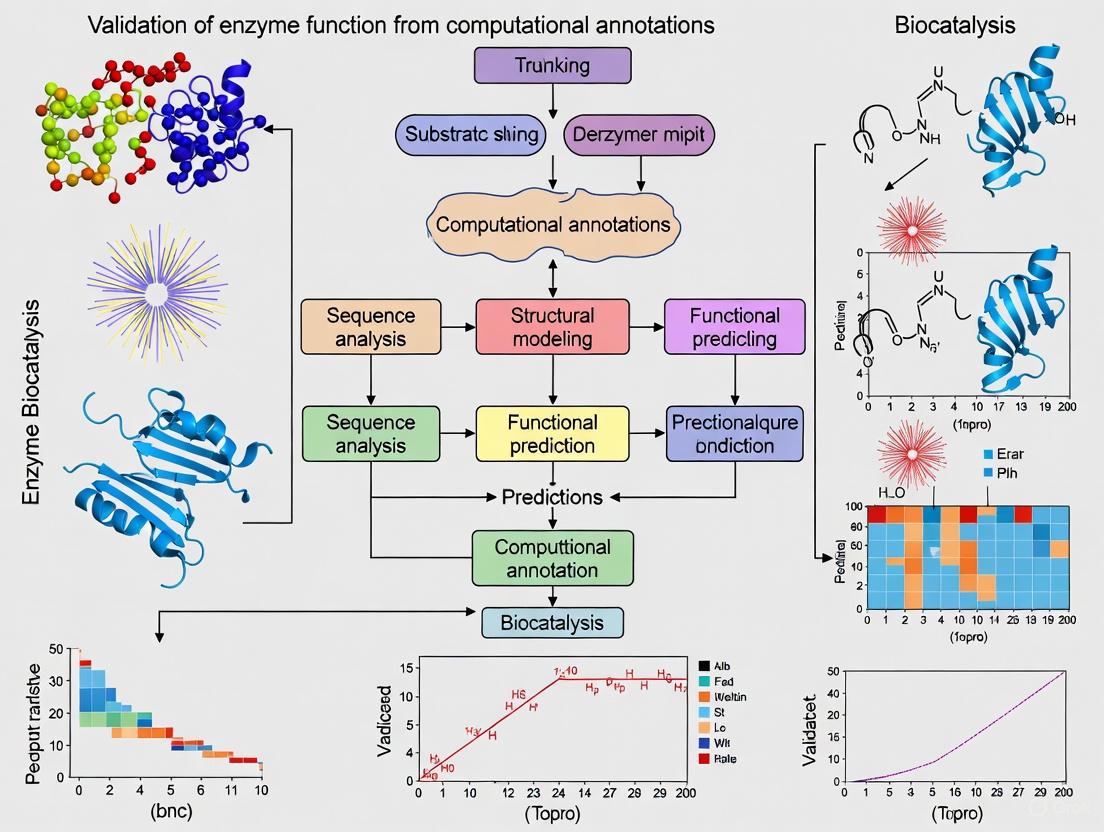

A landmark 2021 investigation conducted an experimental validation of annotations for the S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase enzyme class (EC 1.1.3.15), selected as a proof-of-concept model [9] [1]. This class catalyzes the oxidation of S-2-hydroxyacids like glycolate or lactate to 2-oxoacids using oxygen as an electron acceptor, with importance in photorespiration, fatty acid oxidation, and human health [1]. Researchers employed a high-throughput experimental platform to systematically verify predicted functions through a multi-stage validation workflow (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for validating enzyme function annotations

Pre-Experimental Bioinformatics Analysis

Before experimental validation, computational analysis of the 1,058 unique sequences annotated to EC 1.1.3.15 revealed concerning patterns:

- Limited characterized diversity: Only 17 sequences had experimental evidence, with 14 of eukaryotic origin, indicating severe characterization bias [1].

- Low sequence similarity: 79% of sequences shared less than 25% sequence identity with any characterized S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase [9] [1].

- Non-canonical domain architectures: Only 22.5% contained the expected FMN-dependent dehydrogenase domain (PF01070), while others contained divergent domains including FAD-binding and 2Fe-2S binding domains [1].

Table 1: Pre-experimental Sequence Analysis of EC 1.1.3.15

| Analysis Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Characterized Sequences | 17/1058 (1.6%) | Extreme reliance on computational annotation |

| Sequence Identity to Characterized | 79% <25% identity | Low similarity for reliable homology transfer |

| Canonical Domain Presence | 22.5% with FMN_dh domain | Majority lack essential functional domains |

| Taxonomic Distribution | >90% bacterial | Limited diversity of characterized sequences |

Experimental Findings and Misannotation Quantification

Functional screening of the 65 soluble proteins provided definitive evidence of widespread misannotation:

- Overall misannotation rate: At least 78% of sequences in the enzyme class were misannotated [9] [1].

- Alternative activities: Researchers confirmed four distinct alternative enzymatic activities among the misannotated sequences [1].

- Temporal pattern: Misannotation within the enzyme class increased over time, demonstrating error propagation [1].

- Broader implications: Computational analysis extended to all enzyme classes in BRENDA revealed that nearly 18% of all sequences were annotated to enzyme classes while sharing no similarity or domain architecture with experimentally characterized representatives [9].

Table 2: Experimental Validation Results for EC 1.1.3.15

| Experimental Metric | Result | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Selected Representatives | 122 sequences | Covered diversity of sequence space |

| Soluble Proteins | 65/122 (53%) | Archaeal/eukaryotic less soluble |

| Misannotation Rate | ≥78% | Experimental confirmation of error rate |

| Alternative Activities | 4 confirmed | Misannotations represent real functional diversity |

| BRENDA-wide Problem | ~18% of sequences | Misannotation affects even well-studied classes |

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Function Validation

High-Throughput Functional Screening Methodology

The experimental platform employed for validating EC 1.1.3.15 annotations provides a template for systematic enzyme function verification:

Gene Selection and Synthesis: Selected 122 representative sequences covering the diversity of EC 1.1.3.15 sequence space, with consideration of taxonomic origin, domain architecture, and similarity clusters [1].

Recombinant Expression: Cloned and expressed genes in Escherichia coli using high-throughput protocols. Achieved soluble expression for 65 proteins (53%), with archaeal and eukaryotic proteins proportionally less soluble [9].

Activity Assay: Screened soluble proteins for S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase activity using the Amplex Red peroxide detection assay [9]. This fluorometric method detects hydrogen peroxide production, a byproduct of the oxidase reaction.

Alternative Activity Identification: For misannotated sequences, employed broader substrate profiling to identify correct functions, discovering four alternative activities [1].

Computational Validation Methods

Complementary bioinformatic analyses provide orthogonal validation:

- Domain Architecture Analysis: Used Pfam to identify functional domains; canonical FMN-dependent dehydrogenase domain (PF01070) expected for genuine S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases [1].

- Sequence Similarity Networks: Visualized functional relationships and identified non-isofunctional subgroups [10].

- Active Site Analysis: Compared active site residues with characterized enzymes to identify functionally critical conservation [10].

Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Function Validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Amplex Red Peroxide Detection | Fluorometric detection of H₂O₂ production | Oxidase activity screening [9] |

| BRENDA Database | Comprehensive enzyme function resource | Reference for EC classifications [9] |

| Pfam Database | Protein domain family annotation | Identifying canonical functional domains [1] |

| UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot | Manually curated protein database | High-quality reference sequences [8] |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Custom DNA sequence production | Expressing diverse enzyme variants [1] |

| Solubility Screening | Assessing recombinant protein expression | Filtering functional candidates [9] |

Next-Generation Computational Tools: Performance Comparison

To address annotation challenges, new machine learning tools have emerged with different architectural approaches and performance characteristics (Table 4).

Table 4: Comparison of Enzyme Function Prediction Tools

| Tool | Approach | Input Data | Key Advantages | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOLVE [8] | Ensemble (RF, LightGBM, DT) with focal loss | Primary sequence (6-mer tokens) | Interpretable via Shapley analyses; distinguishes enzymes/non-enzymes | Optimized for class imbalance; high accuracy across EC levels |

| CLEAN-Contact [11] | Contrastive learning + contact maps | Sequence + structure (contact maps) | Integrates sequence and structure information | 16.22% higher precision than CLEAN on New-3927 dataset |

| EZSpecificity [12] | SE(3)-equivariant GNN | 3D enzyme structures | Specificity prediction from active site geometry | 91.7% accuracy vs. 58.3% for previous model on halogenases |

| ProteInfer [11] | Convolutional neural network | Primary sequence | End-to-end prediction from sequence | Lower precision than CLEAN-Contact in benchmarks |

| DeepEC [11] | Neural networks | Primary sequence | Specialized for EC number prediction | Lower performance on rare EC numbers |

Performance Benchmarking Insights

Independent evaluations reveal significant performance variations:

- CLEAN-Contact demonstrates 2.0- to 2.5-fold improvement in precision compared to DeepEC, ECPred, and ProteInfer on the Price-1497 dataset [11].

- SOLVE effectively handles class imbalance through focal loss penalty and provides interpretability via Shapley analysis identifying functional motifs [8].

- EZSpecificity shows remarkable accuracy (91.7%) in identifying single potential reactive substrates for halogenases, significantly outperforming previous methods (58.3%) [12].

- Current ML models still mostly fail to make novel predictions and can make basic logic errors that human annotators avoid, underscoring the need for uncertainty quantification [10].

Implications for Research and Development

Impact on Biological Research and Drug Development

The high misannotation rates have profound implications:

- Metabolic Modeling: Incorrect enzyme annotations compromise genome-scale metabolic models, affecting predictions of metabolic capabilities [11].

- Drug Target Identification: Human HAO1 (a genuine EC 1.1.3.15 enzyme) is a target for primary hyperoxaluria; misannotations could divert research efforts [1].

- Enzyme Engineering: Reliable function prediction is crucial for designing microbial cell factories for medicine, biomanufacturing, and bioremediation [11].

- Microbiome Studies: Gut microbiota enzymes require accurate annotation, as alterations are associated with inflammatory bowel disease and obesity [8].

Recommendations for Researchers

To enhance annotation reliability in research workflows:

- Experimental Validation: Prioritize functional assays for high-value targets, using the described high-throughput platform as a template.

- Tool Selection: Choose computational tools based on specific needs: SOLVE for interpretable sequence-based prediction, CLEAN-Contact for maximum accuracy, EZSpecificity for substrate specificity predictions.

- Multi-Method Consensus: Employ multiple prediction tools and be skeptical of low-confidence annotations, particularly for rare EC numbers.

- Domain Architecture Verification: Always check for canonical functional domains when assigning enzyme functions.

- Consideration of Paralog Complexity: Account for non-isofunctional paralogous groups, a common source of misannotation [10].

The 78% misannotation rate in EC 1.1.3.15 serves as a powerful reminder of the fundamental challenges in enzyme bioinformatics. While next-generation computational tools show promising improvements in accuracy, the gold standard remains experimental validation. Researchers must approach computational annotations with appropriate skepticism, implement robust validation strategies, and stay informed of rapidly evolving prediction technologies to ensure biological conclusions and therapeutic applications rest on firm functional foundations.

Incorrect enzyme functional annotations represent a critical and widespread challenge in biochemical research and drug discovery. These errors, stemming largely from automated sequence-based annotation transfer, lead to significant resource waste, project delays, and increased safety risks in pharmaceutical development. Recent studies reveal that approximately 78% of sequences in some enzyme classes may be misannotated, with nearly 18% of all enzyme sequences in major databases sharing no similarity to experimentally characterized representatives [1] [9]. This comprehensive analysis examines the tangible consequences of these annotations and provides experimental frameworks for validation, offering researchers practical solutions to mitigate risks in their projects.

The Scale and Scope of the Misannotation Problem

Quantitative Evidence of Widespread Misannotation

The problem of enzyme misannotation is not isolated but systemic across biological databases. Experimental validation efforts reveal alarming statistics about annotation reliability:

Table 1: Documented Enzyme Misannotation Rates Across Studies

| Study Focus | Misannotation Rate | Sample Size | Primary Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases (EC 1.1.3.15) | 78% | 122 sequences | High-throughput experimental screening [1] |

| All enzyme classes in BRENDA | 18% of sequences lack similarity to characterized representatives | Entire database analysis | Computational analysis of domain architecture & similarity [9] |

| Bacterial sequences in EC 1.1.3.15 | 79% share <25% sequence identity to characterized sequences | 1,058 sequences | Sequence identity analysis [9] |

The misannotation problem extends beyond single enzyme families. Computational analysis of the BRENDA database reveals that nearly one-fifth of all annotated sequences lack meaningful similarity to experimentally characterized representatives, suggesting systematic issues in annotation pipelines [9]. This problem has practical consequences: researchers may spend months studying proteins with completely incorrect functional assignments, derailing projects before they even begin.

Root Causes of Erroneous Annotations

Understanding the origins of misannotation is crucial for developing solutions. The primary drivers include:

- Automated annotation transfer: Most proteins have functions assigned automatically through sequence similarity to curated entries, with only 0.3% of UniProt/TrEMBL entries manually reviewed [1] [9]

- Convergent evolution limitations: Proteins with similar functions may have low sequence similarity, while those with different functions can share high sequence similarity [13]

- Non-canonical domain architectures: In the S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase class, only 22.5% of sequences contained the canonical FMN-dependent dehydrogenase domain, with the majority having divergent domain structures [9]

- Taxonomic bias: Characterized sequence diversity is limited, with 14 of 17 characterized enzymes in EC 1.1.3.15 being of eukaryotic origin, creating representation gaps [9]

Direct Consequences for Drug Discovery and Development

Impact on Pharmacological Profiling and Safety Assessment

In drug discovery, incorrect enzyme annotations directly impact safety assessment and compound optimization. Recent analysis of pharmacological profiling practices reveals systematic underrepresentation of nonkinase enzymes in safety panels [14]:

Table 2: Enzyme Representation in Pharmacological Profiling

| Profiling Aspect | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme inclusion rate | ~25% of studies included no enzymes in selectivity profiling | Critical safety gaps for compounds targeting non-enzyme targets [14] |

| Overall enzyme representation | Only 11% of targets in pharmacological screens are enzymes | Disconnect from therapeutic reality, as enzymes comprise ~33% of FDA-approved drug targets [14] |

| Hit rate significance | Enzymes have comparable or higher hit rates in selectivity screens | Undetected off-target effects pose clinical safety risks [14] |

This underrepresentation creates significant safety gaps. When investigational molecules target non-enzyme targets, the proportion of enzymes in selectivity screens falls below average, creating blind spots for off-target effects [14]. Given that enzymes constitute the largest pharmacological target class for FDA-approved drugs (approximately one-third of all targets), this discrepancy is particularly concerning [14].

Economic and Timeline Consequences

The downstream effects of misannotation carry substantial economic impacts:

- Late-stage failures: Toxicity observed in clinical trials accounts for 30% of drug candidate failures [14]

- Resource misallocation: Projects pursuing incorrectly annotated targets waste significant R&D resources before errors are detected

- Extended timelines: The need for later target validation and correction of erroneous pathways delays project milestones

The recent FDA analysis of Investigational New Drug applications confirms that enzymes are tested less frequently than other molecular targets despite having comparable or higher hit rates in selectivity screens, indicating a systematic blind spot in current safety assessment practices [14].

Experimental Validation Frameworks

High-Throughput Experimental Validation

To address the misannotation crisis, researchers have developed robust experimental frameworks for validation. A comprehensive approach for validating S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase annotations demonstrates a scalable methodology [1] [9]:

Figure 1: Experimental Validation Workflow for enzyme function.

This experimental pipeline successfully identified that 78% of sequences annotated as S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases were misannotated, with four distinct alternative activities confirmed among the misannotated sequences [1] [9]. The methodology highlights that approximately 53% of expressed proteins were soluble, with archaeal and eukaryotic proteins showing proportionally lower solubility than bacterial counterparts [9].

Computational Validation Metrics

For computationally generated enzymes, recent research has established benchmarking frameworks to evaluate sequence functionality before experimental validation. The Computational Metrics for Protein Sequence Selection (COMPSS) framework improves the rate of experimental success by 50-150% by combining multiple evaluation metrics [5]:

Table 3: Computational Metrics for Predicting Enzyme Functionality

| Metric Category | Examples | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-based | Sequence identity, BLOSUM62 scores | Detects general sequence properties | Ignores epistatic interactions, position equality [5] |

| Alignment-free | Protein language model likelihoods | Fast computation, no homology requirement | May miss structural constraints [5] |

| Structure-based | Rosetta scores, AlphaFold2 confidence | Captures atomic-level function determinants | Computationally expensive for large sets [5] |

Experimental validation of over 500 natural and generated sequences demonstrated that only 19% of tested sequences were active, highlighting the critical need for improved computational filters before experimental investment [5]. Key failure modes included problematic signal peptides, transmembrane domains, and disruptive truncations at protein interaction interfaces [5].

AI and Advanced Computational Solutions

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Approaches

Artificial intelligence methods are increasingly addressing the limitations of traditional sequence-similarity approaches:

- Conventional machine learning: Algorithms like k-Nearest Neighbors (kNN), Support Vector Machines (SVM), and Random Forests using features from amino acid compositions and physicochemical properties [13]

- Deep neural networks: Complex architectures that learn patterns directly from raw amino acid sequences without extensive feature engineering [13]

- Transformer-based models: Leveraging self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies in protein sequences [13]

These methods overcome critical limitations of traditional approaches, particularly in handling cases where convergent evolution creates proteins with similar functions but low sequence similarity, or where divergent evolution results in proteins with different functions but high sequence similarity [13].

Experimental Validation of AI-Generated Enzymes

Rigorous evaluation of AI-generated enzymes reveals both promise and limitations. Assessment of sequences produced by three contrasting generative models (ancestral sequence reconstruction, generative adversarial networks, and protein language models) showed varying success rates [5]:

- Ancestral sequence reconstruction: Generated 9 of 18 active copper superoxide dismutases and 10 of 18 active malate dehydrogenases

- Generative adversarial networks: Only 2 of 18 active copper superoxide dismutases and 0 of 18 active malate dehydrogenases

- Language models: 0 of 18 active sequences for both enzyme families

These results highlight that while computational generation can produce novel sequences, robust experimental validation remains essential, as model performance varies significantly by approach [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents for Enzyme Validation Studies

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant expression systems (E. coli) | Heterologous protein production | High-throughput expression of 122 candidate sequences [9] |

| Amplex Red peroxide detection | Fluorometric activity detection | Screening for S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase activity [9] |

| Phobius prediction tool | Signal peptide and transmembrane domain identification | Filtering out sequences with problematic domains [5] |

| BRENDA Database | Reference enzyme functional data | Benchmarking against experimentally characterized sequences [1] [9] |

| UniProt/TrEMBL | Comprehensive sequence database | Source of diverse sequences for analysis [1] [9] |

| Pfam domain architecture analysis | Protein domain identification | Detecting non-canonical domain arrangements [9] |

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction | Residue confidence scoring for structure-based metrics [5] |

Incorrect enzyme annotations represent a critical vulnerability in biomedical research and drug discovery pipelines, with demonstrated potential to derail projects through misdirected resources, safety oversights, and late-stage failures. The documented 78% misannotation rate in some enzyme classes, coupled with the systematic underrepresentation of enzymes in pharmacological profiling, creates perfect conditions for project failure [14] [1] [9].

Moving forward, the field requires:

- Integrated validation pipelines that combine computational pre-screening with medium-throughput experimental verification

- Expanded pharmacological profiling panels that better represent enzyme targets, particularly nonkinase enzymes

- Database curation initiatives to address systematic annotation errors

- Improved AI models with demonstrated experimental validation

By adopting rigorous validation frameworks and recognizing the limitations of current annotations, researchers can mitigate these risks and build more reliable drug discovery pipelines. The consequences of incorrect annotations are too significant to ignore, affecting everything from basic research conclusions to clinical trial outcomes and patient safety.

The exponential growth of genomic data has profoundly transformed biological research, yet this abundance of sequence information presents a significant challenge: the reliability of functional annotations. With nearly 185 million entries in the UniProt/TrEMBL protein database and only 0.3% manually annotated and reviewed in Swiss-Prot, the vast majority of proteins have their function assigned through automated methods [1] [9]. This over-reliance on computational inference has led to a crisis of misannotation that permeates public databases and compromises research validity. A groundbreaking experimental investigation into a single enzyme class (EC 1.1.3.15) revealed that at least 78% of sequences were incorrectly annotated, with the majority containing non-canonical protein domains and lacking predicted activity [1] [9]. This startling finding underscores the critical limitation of sequence-based annotation and highlights the urgent need for approaches that integrate domain architecture and three-dimensional active site structure for accurate functional validation.

The pervasiveness of this problem extends across enzyme classes, with a computational analysis of the BRENDA database indicating that nearly 18% of all sequences are annotated to enzyme classes while sharing no similarity or domain architecture to experimentally characterized representatives [1] [9]. This misannotation crisis affects even well-studied enzyme classes of industrial and medical relevance, potentially leading research astray and hampering drug discovery efforts. As we move further into the structural genomics era, with initiatives like the AlphaFold Database releasing over 214 million predicted structures [15], the scientific community faces both unprecedented opportunities and formidable challenges in bridging the gap between sequence data and biological function.

Experimental Evidence: Quantifying the Misannotation Crisis

Case Study: Systematic Misannotation in EC 1.1.3.15

A rigorous experimental investigation of the S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase enzyme class (EC 1.1.3.15) provides compelling evidence for the misannotation crisis. Researchers selected 122 representative sequences spanning the diversity of this enzyme class for experimental validation [1] [9]. Through high-throughput synthesis, cloning, and recombinant expression in Escherichia coli, they obtained 65 soluble proteins (53% solubility rate) for functional characterization [9]. The experimental workflow involved testing each soluble protein for S-2-hydroxy acid oxidase activity using the Amplex Red peroxide detection system, which provides a sensitive spectrophotometric readout of enzymatic function.

The results revealed a startling discrepancy between computational predictions and experimental evidence. While all selected sequences were annotated as EC 1.1.3.15 enzymes, the majority lacked the predicted activity. Analysis of sequence similarity and domain architecture provided crucial insights into the root causes of misannotation. Notably, 79% of sequences annotated as EC 1.1.3.15 shared less than 25% sequence identity with the closest experimentally characterized representative [1] [9]. Even more telling was the domain architecture analysis, which showed that only 22.5% of the 1,058 sequences in this enzyme class contained the canonical FMN-dependent dehydrogenase domain (FMN_dh, PF01070) characteristic of genuine 2-hydroxy acid oxidases [1] [9]. The majority were predicted to contain non-canonical domains, including FAD binding domains characteristic of entirely different oxidoreductase families, cysteine-rich domains, and 2Fe-2S binding domains, suggesting fundamentally different biochemical functions.

Beyond a Single Enzyme Class: The Broader Implications

The misannotation problem identified in EC 1.1.3.15 is not an isolated case but rather representative of a systemic issue affecting functional databases. Experimental confirmation of four alternative enzymatic activities among the misannotated sequences demonstrates how erroneous annotations can obscure true biological function and hinder the discovery of novel enzymatic activities [1] [9]. Furthermore, the study documented that misannotation within this enzyme class has increased over time, suggesting that the problem is compounding as automated annotation pipelines process ever-larger datasets without sufficient experimental validation [1].

This misannotation crisis has real-world consequences for biotechnology and medicine. Enzymes in the EC 1.1.3.15 class play crucial roles in various biological processes and applications: plant glycolate oxidases are essential for photorespiration, mammalian hydroxyacid oxidases participate in glycine synthesis and fatty acid oxidation, and bacterial lactate oxidases are used in clinical biosensors for lactate monitoring in healthcare and sports medicine [1] [9]. Human HAO1 has been proposed as a therapeutic target for treating primary hyperoxaluria, a metabolic disorder causing renal decline [1] [9]. Inaccurate annotations of such medically relevant proteins could significantly impede drug discovery efforts and the development of diagnostic tools.

Table 1: Experimental Validation of EC 1.1.3.15 Annotations

| Analysis Parameter | Finding | Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Sequences tested | 122 representative sequences | Comprehensive coverage of sequence diversity |

| Solubility rate | 65 soluble proteins (53%) | Representative functional testing |

| Misannotation rate | ≥78% of sequences | Widespread incorrect functional assignments |

| Sequence similarity | 79% with <25% identity to characterized enzymes | Limited basis for homology-based transfer |

| Domain architecture | Only 22.5% contain canonical FMN-dependent dehydrogenase domain | Fundamental structural mismatch with annotation |

| Alternative activities | 4 confirmed among misannotated sequences | True functions being obscured by incorrect annotations |

Computational Methods: From Sequence to Structure

Limitations of Sequence-Based Annotation

Traditional automated annotation methods primarily rely on sequence similarity to infer function, an approach that fails to account for the complex relationship between sequence, structure, and function. The fundamental assumption that sequence similarity implies functional similarity breaks down at lower identity levels, particularly below the "twilight zone" of 25% sequence identity where structural and functional divergence becomes common [1]. This limitation is exacerbated by the exponential growth of sequence databases, which outpaces the capacity for experimental characterization and creates a propagation cycle where misannotations beget further misannotations.

Recent research has demonstrated that even advanced generative protein sequence models struggle to predict functional enzymes reliably. In a comprehensive evaluation of computational metrics for predicting in vitro enzyme activity, researchers expressed and purified over 500 natural and generated sequences with 70-90% identity to natural sequences [5]. The initial round of "naive" generation resulted in mostly inactive sequences, with only 19% of experimentally tested sequences showing activity above background levels [5]. This poor performance highlights the limitations of sequence-centric approaches and underscores the need for structural validation, particularly for distinguishing functional enzymes from non-functional counterparts with similar sequences.

Structural Alignment and Comparison Tools

The emergence of massive structural databases has driven the development of advanced structural alignment algorithms capable of efficiently comparing three-dimensional protein structures. Traditional structural alignment methods like DALI and CE provided accurate comparisons but required several seconds per structure pair, making them impractical for large-scale analyses [15]. More recent approaches have focused on improving computational efficiency while maintaining accuracy through innovative strategies.

The SARST2 algorithm represents a significant advancement in structural alignment technology, employing a filter-and-refine strategy that integrates primary, secondary, and tertiary structural features with evolutionary statistics [15]. This method utilizes machine learning with decision trees and artificial neural networks to rapidly filter out non-homologous structures before performing more computationally intensive detailed alignments. In benchmark evaluations, SARST2 achieved an impressive 96.3% accuracy in retrieving family-level homologs, outperforming other state-of-the-art methods including FAST (95.3%), TM-align (94.1%), and Foldseek (95.9%) [15]. Notably, SARST2 completed searches of the massive AlphaFold Database significantly faster than both BLAST and Foldseek while using substantially less memory, enabling researchers to perform large-scale structural comparisons on ordinary personal computers [15].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Structural Alignment Methods

| Method | Accuracy | Speed | Memory Efficiency | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SARST2 | 96.3% | Fastest | Highest | Integrated filter-and-refine strategy with machine learning |

| Foldseek | 95.9% | Fast | Moderate | 3Di structural strings from deep learning |

| FAST | 95.3% | Moderate | Moderate | Pioneering rapid structural alignment |

| TM-align | 94.1% | Moderate | Moderate | Widely used for topology-based alignment |

| BLAST | 89.8% | Slow (sequence-based) | Low | Sequence-only comparison |

Integrated Workflows: Combining Computational and Experimental Approaches

The COMPSS Framework for Predicting Enzyme Functionality

The development of the Composite Metrics for Protein Sequence Selection (COMPSS) framework represents a significant step forward in predicting enzyme functionality from sequence and structural features. Through three rounds of iterative experimentation and computational refinement, researchers established a composite computational metric that improved the rate of experimental success by 50-150% compared to naive selection methods [5]. This framework evaluates sequences using a combination of alignment-based, alignment-free, and structure-supported metrics to account for various factors that influence protein folding and function.

The COMPSS framework was rigorously validated using two enzyme families—malate dehydrogenase (MDH) and copper superoxide dismutase (CuSOD)—selected for their substantial sequence diversity, physiological significance, and complex multimeric structures [5]. The evaluation included sequences generated by three contrasting generative models: ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR), generative adversarial networks (GANs), and protein language models (ESM-MSA) [5]. This comprehensive approach demonstrated that no single metric could reliably predict function, but an appropriately weighted combination could significantly enhance the selection of functional sequences for experimental testing.

High-Throughput Experimental Validation Platforms

Advanced experimental platforms are essential for validating computational predictions at scale. The high-throughput pipeline used for characterizing EC 1.1.3.15 enzymes exemplifies this approach, incorporating gene synthesis, cloning, recombinant expression in E. coli, solubility assessment, and enzymatic activity assays [1] [9]. This systematic workflow enables rapid functional screening of hundreds of sequences, generating crucial experimental data to benchmark and refine computational predictions.

For structural characterization, integrative approaches combine multiple experimental techniques to elucidate the hierarchical organization of protein structures:

- Primary structure: Determined through classical sequencing techniques (Edman degradation, dansyl chloride assays) complemented by modern mass spectrometry-based peptide mapping and emerging nanopore-based sequencing technologies [16]

- Secondary structure: Probed using circular dichroism spectroscopy to quantify α-helical and β-sheet content, monitor conformational transitions, and evaluate thermostability [16]

- Tertiary structure: Resolved through high-resolution methods including X-ray crystallography, nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy, and cryo-electron microscopy, often complemented by computational predictions [16]

This multi-level structural analysis provides crucial insights into active-site geometry, protein-protein interactions, and functional divergence within protein superfamilies, enabling researchers to move beyond sequence-based annotations to understand the structural determinants of function.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for validating enzyme function, combining computational analysis with experimental validation.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Enzyme Validation

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Enzyme Function Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| Amplex Red Peroxide Detection | Spectrophotometric detection of peroxide production | Functional assay for oxidase activity [1] [9] |

| ESM-MSA Transformer | Protein language model for sequence generation | Generating novel sequences for functional testing [5] |

| ProteinGAN | Generative adversarial network for protein sequence design | Creating diverse sequences beyond natural variation [5] |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Statistical phylogenetic model | Resurrecting ancient sequences with enhanced stability [5] |

| SARST2 Structural Aligner | Rapid structural alignment against massive databases | Identifying structural homologs and functional domains [15] |

| Circular Dichroism Spectroscopy | Secondary structure quantification | Assessing proper protein folding and stability [16] |

| AlphaFold2 | AI-based structure prediction | Generating 3D models for active site analysis [5] [15] |

The validation of enzyme function requires moving beyond sequence-based assumptions to incorporate domain architecture and three-dimensional active site structure. Experimental evidence demonstrates that 78% of sequences in at least one enzyme class are misannotated when relying solely on sequence similarity [1] [9], highlighting the critical importance of structural validation. The development of integrated computational and experimental workflows, such as the COMPSS framework [5] and advanced structural alignment tools like SARST2 [15], provides researchers with powerful methodologies for accurate functional annotation.

As structural databases continue to expand, with initiatives like the AlphaFold Database now containing over 214 million predicted structures [15], the research community has unprecedented resources for structural and functional analysis. By leveraging these resources alongside high-throughput experimental validation platforms, researchers can overcome the limitations of traditional annotation methods and advance our understanding of the complex relationship between protein structure and function. This integrated approach is essential for accelerating drug discovery, understanding disease mechanisms, and harnessing the full potential of genomic data for biomedical innovation.

Computational Arsenal: From AI-Driven Prediction to Generative Design

The accurate computational annotation of enzyme function represents a critical challenge at the intersection of bioinformatics and drug development. With the UniProt/TrEMBL database containing nearly 185 million entries and only 0.3% manually annotated and reviewed, the research community heavily relies on automated function prediction, which can result in significant error rates [1]. Experimental validation of the S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase enzyme class (EC 1.1.3.15) revealed that at least 78% of sequences were misannotated, highlighting the severity of this problem [1]. This validation crisis in enzyme annotation has created an urgent need for more sophisticated computational approaches that can reliably predict enzyme function before costly experimental verification.

Cross-attention graph neural networks (GNNs) have emerged as a powerful framework for addressing this challenge by simultaneously modeling multiple data modalities and relationships. These architectures extend beyond conventional GNNs by incorporating attention mechanisms that enable dynamic weighting of features from different sources—such as node features, topological information, and relational data—allowing for more nuanced and specific predictions of enzyme function and activity [17] [18].

Cross-Attention GNN Architectures for Biological Prediction

Graph Topology Attention Networks (GTAT)

The Graph Topology Attention Networks (GTAT) framework enhances graph representation learning by explicitly incorporating topological information through cross-attention mechanisms. GTAT operates through two sequential processes: first, it extracts topology features from the graph structure and encodes them into topology representations using Graphlet Degree Vectors (GDV), which capture the distribution of nodes in specific orbits of small connected subgraphs [17]. Second, it processes both node and topology representations through cross-attention GNN layers, allowing the model to dynamically adjust the influence of node features and topological information [17].

This architecture specifically addresses limitations of previous GNN approaches that failed to adequately integrate richer topological features beyond basic information like node degrees or edges. By treating node feature representations and extracted topology representations as separate modalities, GTAT achieves more robust expression of graph structures [17]. Experimental results demonstrate that this approach mitigates over-smoothing issues and increases robustness against noisy data, both critical factors in biological network inference [17].

Cross-Attention for Gene Regulatory Networks (XATGRN)

The Cross-Attention Complex Dual Graph Embedding Model (XATGRN) addresses the specific challenge of inferring gene regulatory networks with skewed degree distribution, where some genes regulate multiple others (high out-degree) while others are regulated by multiple factors (high in-degree) [18]. This architecture employs a cross-attention mechanism to focus on the most informative features within bulk gene expression profiles of regulator and target genes, enhancing the model's representational power for predicting regulatory relationships and their directionality [18].

XATGRN utilizes a fusion module based on Cross-Attention Network (CAN) that processes gene expression data for regulator gene R and target gene T to generate queries, keys, and values for the cross-attention mechanism [18]. The model retains half of each gene's original self-attention embedding and half of its cross-attention embedding, enabling it to handle intrinsic features of each gene while capturing complex regulatory interactions between them [18].

Configuration Cross-Attention for Tensor Compilers (TGraph)

While not directly applied to biological prediction, the TGraph architecture demonstrates the versatility of cross-attention GNNs for complex optimization problems. TGraph employs cross-configuration attention that enables explicit comparison between different configurations within the same batch, transforming the problem from individual prediction to learned ranking [19]. This approach has shown significant performance improvements, increasing mean Kendall's τ across layout collections from 29.8% to 67.4% compared to reliable baselines [19].

Performance Comparison: Cross-Attention GNNs vs. Alternative Approaches

Table 1: Performance comparison of graph neural network architectures across different domains

| Model Architecture | Application Domain | Key Metric | Performance | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GTAT (Graph Topology Attention) | General Graph Representation | Classification Accuracy | Outperforms state-of-the-art methods on various benchmark datasets | [17] |

| XATGRN | Gene Regulatory Network Inference | Regulatory Relationship Prediction | Consistently outperforms state-of-the-art methods across various datasets | [18] |

| MPNN | Chemical Reaction Yield Prediction | R² Value | 0.75 (Highest among GNN architectures tested) | [20] |

| GAT/GATv2 | Chemical Reaction Yield Prediction | R² Value | Lower than MPNN | [20] |

| Traditional Heuristic Compilers | Tensor Program Optimization | Kendall's τ | 29.8% | [19] |

| TGraph (Cross-Attention) | Tensor Program Optimization | Kendall's τ | 67.4% | [19] |

Table 2: Experimental results for enzyme function prediction and validation

| Study Focus | Experimental System | Key Finding | Impact | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Annotation Accuracy | S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases (EC 1.1.3.15) | 78% misannotation rate in enzyme class | Highlights critical need for improved prediction methods | [1] |

| Computational Filter Development | Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) & Copper superoxide dismutase (CuSOD) | Improved experimental success rate by 50-150% | Demonstrates value of computational pre-screening | [5] |

| Generative Model Comparison | Ancestral sequence reconstruction, GAN, Protein Language Model | ASR generated 9/18 (CuSOD) and 10/18 (MDH) active enzymes | Establishes benchmark for generative protein models | [5] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Enzyme Function Validation Workflow

Experimental validation of computational predictions follows a rigorous multi-stage process. For enzyme function validation, this typically involves: (1) selecting representative sequences from the enzyme class; (2) synthesizing, cloning, and recombinantly expressing proteins in systems like Escherichia coli; (3) assessing protein solubility and stability; and (4) testing predicted activity through specific biochemical assays [1]. For S-2-hydroxyacid oxidases, the Amplex Red peroxide detection system serves as a key assay method, detecting hydrogen peroxide production as a byproduct of the oxidase reaction [1].

The COMPSS (Composite Metrics for Protein Sequence Selection) framework provides a structured approach for evaluating computational metrics for predicting enzyme activity. This involves multiple rounds of experimentation, starting with naive generation and progressively refining metrics based on experimental outcomes [5]. Critical parameters assessed include alignment-based metrics (sequence identity, BLOSUM62 scores), alignment-free methods (protein language model likelihoods), and structure-supported metrics (Rosetta-based scores, AlphaFold2 confidence scores) [5].

Cross-Attention GNN Implementation

Implementing cross-attention GNNs for biological prediction requires specific architectural considerations. The GTAT framework utilizes the Orbit Counting Algorithm (OCRA) to compute Graphlet Degree Vectors with time complexities of O(n·d³) and O(n·d⁴) for graphlets with up to four and five nodes respectively, where n is the number of nodes and d is the maximum node degree [17]. The topology representations are then normalized and processed through a multilayer perceptron before being input into the graph cross-attention layers [17].

For XATGRN, the cross-attention mechanism is implemented through projection matrices that map gene expression data for regulator and target genes into query, key, and value representations [18]. The model employs multi-head self-attention and cross-attention mechanisms, with each gene retaining half of its original self-attention embedding and half of its cross-attention embedding to balance intrinsic features and interaction patterns [18].

Diagram 1: Cross-attention mechanism for integrating node features and topology information in GTAT architecture

Performance Evaluation Metrics

Evaluation of enzyme function predictors utilizes multiple complementary metrics. For classification tasks, standard metrics include accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score. The diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) serves as a combined indicator of sensitivity and specificity, providing a single metric for comparing predictive accuracy across different biomarkers or prediction methods [21]. Hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic curves (HSROCs) account for threshold effects when summarizing overall diagnostic performance [21].

In ranking tasks such as configuration optimization, Kendall's τ correlation coefficient measures the ordinal association between predicted and actual rankings, with TGraph achieving 67.4% compared to 29.8% for traditional heuristic approaches [19]. For regression tasks including chemical reaction yield prediction, R² values quantify the proportion of variance explained by the model, with MPNN achieving 0.75 in comparative studies of GNN architectures [20].

Table 3: Key research reagents and computational resources for cross-attention GNN implementation

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Purpose | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Validation Systems | Escherichia coli expression system | Recombinant protein production | Heterologous enzyme expression for activity testing [5] |

| Amplex Red Peroxide Assay | Detection of oxidase activity | Validation of S-2-hydroxyacid oxidase function [1] | |

| Computational Datasets | BRENDA Enzyme Database | Comprehensive enzyme functional data | Source of enzyme sequences and classifications [1] |

| TpuGraphs Dataset | Runtime measurements of computational graphs | Benchmarking configuration optimization models [19] | |

| GNN Implementation Frameworks | Graphlet Degree Vectors (GDV) | Topological feature extraction | Node topology representation in GTAT [17] |

| Orbit Counting Algorithm (OCRA) | Graphlet enumeration | Computation of GDV with reduced complexity [17] | |

| Cross-Attention Network (CAN) | Multi-modal feature fusion | Integration of regulator-target gene interactions [18] | |

| Performance Assessment Tools | Diagnostic Odds Ratio (DOR) | Combined sensitivity/specificity metric | Evaluation of prediction accuracy [21] |

| Hierarchical SROC (HSROC) | Threshold-independent performance analysis | Summary of predictive performance across studies [21] | |

| Kendall's τ | Rank correlation coefficient | Assessment of configuration ranking accuracy [19] |

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for computational prediction and experimental validation of enzyme function

Cross-attention graph neural networks represent a significant advancement in computational enzyme function prediction, addressing critical limitations of previous approaches through their ability to integrate multiple data modalities and dynamically weight feature importance. The demonstrated success of architectures like GTAT and XATGRN across diverse biological prediction tasks, coupled with the rigorous experimental validation of computational predictions, points toward a future where in silico enzyme annotation achieves substantially higher accuracy rates.

As these methods continue to evolve, integrating additional data sources such as protein structures from AlphaFold2, metabolic pathway context, and chemical reaction data will further enhance their predictive power. For researchers and drug development professionals, these advancements translate to more reliable pre-screening of enzyme candidates, reduced experimental costs, and accelerated discovery pipelines. The cross-attention paradigm, with its flexibility and performance advantages, is poised to become a cornerstone of computational enzyme function prediction in the coming years.

The engineering of novel enzymes represents a frontier in synthetic biology, with applications ranging from sustainable chemistry and biomanufacturing to therapeutic drug design [22]. While generative artificial intelligence (AI) and protein language models (pLMs) have demonstrated remarkable capability in sampling novel protein sequences, a significant challenge remains: predicting whether these computationally generated sequences will fold into stable structures and exhibit the desired catalytic function [5]. The assumption that novel sequences drawn from a distribution similar to natural proteins will be functional does not always hold true, with experimental studies revealing that initial "naive" generation can result in a majority (over 80%) of inactive sequences [5]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current computational models and evaluation frameworks, focusing on their performance in generating and identifying functional enzyme sequences, to serve as a benchmark for researchers navigating this complex landscape.

Comparative Analysis of Generative Models and Evaluation Metrics

The performance of AI-generated enzymes is highly dependent on the choice of generative model and the computational metrics used for evaluation. Below, we compare prominent approaches based on experimental validation studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Generative Models for Enzyme Design

| Generative Model | Model Type | Reported Experimental Success Rate | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR) [5] | Phylogeny-based Statistical Model | ~50-55% (MDH & CuSOD) [5] | High stability; successful resurrection of ancient functions [5] | Constrained by evolutionary history; limited novel sequence exploration [5] |

| Generative Adversarial Network (ProteinGAN) [5] | Deep Neural Network (GAN) | ~0-11% (MDH & CuSOD) [5] | Potential to explore novel sequence spaces [5] | High rate of non-functional sequences; requires robust filtering [5] |

| Protein Language Model (ESM-MSA/ESM-2) [5] [23] | Transformer-based Language Model | ~55-60% (when combined with epistasis model) [23] | Learns evolutionary patterns from massive datasets; powerful for variant prediction [24] [23] | Can produce homogeneous outputs without careful fine-tuning [24] |

| Fully Computational Workflow (Rosetta) [25] | Physical & Knowledge-Based Design | High (for designed Kemp eliminases) [25] | Can create novel active sites and achieve natural-level efficiency without screening [25] | Applied primarily to well-defined model reactions |

Evaluation Metrics: From Simple Filters to Composite Scores

Selecting the right computational metrics is critical for predicting enzyme function before costly experimental work. A landmark study systematically evaluated 20 diverse metrics, leading to the development of the COMposite Metrics for Protein Sequence Selection (COMPSS) framework [5]. This filter integrates alignment-based, alignment-free, and structure-based metrics, and was shown to improve the rate of experimental success by 50% to 150% [5].

Table 2: Key Computational Metrics for Evaluating Generated Enzyme Sequences

| Metric Category | Example Metrics | Principle | Performance in Predicting Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alignment-Based [5] | Sequence Identity, BLOSUM62 Score | Relies on homology to natural sequences | Good for general properties but misses epistatic interactions; moderate predictive power alone [5] |

| Alignment-Free [5] | Protein Language Model Likelihoods (e.g., from ESM) | Fast, model-internal scoring; captures co-evolutionary signals | Sensitive to pathogenic mutations; high predictive potential when combined [5] [26] |

| Structure-Based [5] | AlphaFold2 Confidence (pLDDT), Rosetta Energy Scores | Uses predicted or designed atomic structures | Captures functional constraints but can be computationally expensive; high value in composite scores [5] |

| Specialized Prediction Models [8] | SOLVE, CLEAN, DeepEC | Machine learning models trained to predict EC number or fitness from sequence | SOLVE showed high accuracy in enzyme vs. non-enzyme classification and EC number prediction [8] |

Diagram 1: The COMPSS multi-filter workflow for selecting functional enzymes.

Experimental Protocols for Validating AI-Generated Enzymes

Rigorous experimental validation is the ultimate benchmark for any computationally generated enzyme. The following protocols are standardized in the field.

Protein Expression, Purification, and In Vitro Assay

A standard workflow for validating generated sequences involves cloning the genes into expression vectors (typically in E. coli), expressing and purifying the proteins, and testing their activity in vitro [5]. A protein is considered "experimentally successful" if it can be expressed and folded solubly and demonstrates activity significantly above background in a relevant biochemical assay [5]. Key considerations include:

- Avoiding Overtruncation: For enzymes like CuSOD, truncations that remove residues critical for multimerization (e.g., at dimer interfaces) can destroy activity [5].

- Signal Peptide Handling: For proteins from certain kingdoms (e.g., bacterial CuSOD), predicting and truncating signal peptides is essential for correct expression in heterologous systems like E. coli [5].

High-Throughput Characterization in Autonomous Platforms

Cutting-edge research now integrates AI with fully automated biofoundries. One platform, leveraging the Illinois Biological Foundry (iBioFAB), automates the entire Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle [23]. This includes:

- Design: Using a pLM (ESM-2) and an epistasis model (EVmutation) to design initial variant libraries.

- Build: Employing a high-fidelity assembly mutagenesis method to construct variant libraries with ~95% accuracy without intermediate sequencing [23].

- Test: Fully automated modules for transformation, colony picking, protein expression, and enzyme assays.

- Learn: Using the collected data to train machine learning models for the next design cycle. This approach has successfully engineered enzymes with 16- to 26-fold improvements in activity within four weeks [23].

Diagram 2: Autonomous enzyme engineering DBTL cycle.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for AI-Driven Enzyme Engineering

| Item Name | Function/Application | Relevant Study/Model |

|---|---|---|

| ESM-2 (650M/35M parameters) [24] [23] | Core protein language model for sequence understanding, fitness prediction, and variant generation. | BIT-LLM PROTEUS [24], Autonomous Engineering Platform [23] |

| EVmutation [23] | Epistasis model identifying co-evolutionary constraints in protein families for library design. | Autonomous Engineering Platform [23] |

| AlphaFold2/3 [22] | High-accuracy protein structure prediction; used for structural evaluation of designed enzymes. | Structure-based metrics [5], Enzyme discovery [22] |

| UniProtKB / ProteinGym [24] [26] | Curated protein sequence databases and benchmarks for model training and evaluation. | SOLVE [8], ESM training [26], BIT-LLM [24] |

| COMPSS Framework [5] | A composite computational filter integrating multiple metrics to select functional sequences. | Experimental benchmarking of generative models [5] |

| Rosetta Software Suite [25] | A comprehensive toolkit for de novo enzyme design and energy-based scoring. | High-efficiency Kemp eliminase design [25] |

The field of AI-powered enzyme generation is rapidly evolving from a trial-and-error process to a disciplined engineering science. The experimental data clearly shows that while no single model is universally superior, integrated approaches that combine the strengths of generative pLMs (like ESM-2), evolutionary principles (like ASR), and robust multi-metric evaluation frameworks (like COMPSS) significantly increase the probability of experimental success [5] [23]. Future progress hinges on several key trends: a shift from single-modal to multimodal models that integrate sequence, structure, and dynamic information; the development of intelligent agents capable of autonomously running DBTL cycles; and moving beyond static structure prediction toward the dynamic simulation of enzyme function [27]. For researchers, the critical takeaway is that successful enzyme design now depends on a synergistic pipeline—combining powerful generative models with rigorous, multi-faceted computational screening and, where possible, leveraging automation to accelerate experimental validation.

In the field of functional proteomics, a significant challenge persists: directly measuring enzyme activity remains difficult and often indirect, creating a critical gap in our understanding of cellular signaling networks. While high-throughput proteomics can readily quantify protein abundance, enzyme activity cannot be simply inferred from these levels alone, as it is dynamically regulated through mechanisms such as post-translational modifications (PTMs). This limitation is particularly problematic because dysregulated enzyme activity lies at the heart of numerous complex diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative disorders. The inability to efficiently map this activity on a proteome-wide scale has hindered both basic biological discovery and the development of targeted therapies.

Traditional methods for measuring enzyme activity are typically low-throughput and cannot capture the system-wide dynamics of signaling networks. This creates a pressing need for computational tools capable of bridging this gap by inferring activity from the downstream molecular footprints enzymes leave on their substrates. PTM data, especially from phosphoproteomics experiments, contains a rich source of information about the upstream enzymatic activities that created these modification patterns. Recently, innovative computational tools have emerged to decipher these patterns, offering researchers the ability to reconstruct signaling network activity from standard proteomics data. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these tools, focusing on their methodologies, performance, and practical application for validating enzyme function.

Computational Tools for Activity Inference: A Comparative Analysis

Several computational approaches have been developed to infer enzyme activity from PTM data, particularly phosphoproteomics. These tools vary in their underlying algorithms, the types of enzymes they can analyze, and their analytical capabilities. The following table summarizes the key features of major tools in this domain.

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Tools for Inferring Enzyme Activity from PTM Data

| Tool Name | Supported Enzymes | Core Methodology | Input Data | Unique Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JUMPsem [28] | Kinases, E3 Ubiquitin Ligases, HATs | Structural Equation Model (SEM) | Quantitative PTM (e.g., phospho-, ubiquitin-, acetyl-) data | Integrates public enzyme-substrate data; motif search to expand networks; handles multiple PTM types. [28] | Does not fully account for complex cross-talk between different enzymes in signaling networks. [28] |

| KEA3 [29] | Kinases | Kinase Enrichment Analysis | List of proteins or phosphorylated proteins | Upstream kinase prediction from protein lists; uses curated kinase-substrate interactions from multiple sources. [29] | Limited to kinase activity; inference based on enrichment rather than direct quantitative modeling. |

| IKAP [28] | Kinases | Not Specified | Phosphoproteomics data | Established tool for kinase activity estimation. [28] | Outperformed by JUMPsem in precision benchmarks; specific methodology not detailed. [28] |

| KSEA [28] | Kinases | Kinase Substrate Enrichment Analysis | Phosphoproteomics data | Established method for inferring kinase activity from phosphoproteomics data. [28] | Does not appear to incorporate network context or motif discovery like JUMPsem. |

| PhosphoRS (via IsobarPTM) [30] | (PTM Localization) | Localization probability scoring | MS/MS spectra | Validates PTM site localization, which is critical for accurate activity inference. [30] | Not a direct activity inference tool; focuses on prerequisite step of confident PTM site mapping. |

In-Depth Tool Profile: JUMPsem

JUMPsem is a relatively new and innovative tool designed to overcome the limitations of existing methods. It is implemented as a modular and scalable R package and is also accessible via a user-friendly R/Shiny application, making it available to both computational biologists and wet-lab scientists [28]. Its analytical process is logically structured into three key phases:

- Data Integration and Curation: The tool begins by constructing an enzyme-substrate relationship network. It pulls known relationships from public databases and can significantly expand this network (by an average of 14.7% for kinases) using an integrated motif search strategy to predict novel substrate sites [28].

- Activity Inference via Structural Modeling: The core of its functionality uses a Structural Equation Model (SEM). This algorithm integrates the curated enzyme-substrate relationships with the quantitative PTM data from mass spectrometry to compute an inferred activity score for each enzyme [28].

- Output and Visualization: The final output includes tables of inferred enzyme activities and enzyme-substrate affinity. These results can be easily visualized and explored within the accompanying Shiny app, facilitating biological interpretation [28].

Performance and Benchmarking

In direct comparative analyses, JUMPsem has demonstrated superior performance. When researchers compared it against established tools like IKAP and KSEA using human acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cell line phosphoproteomics data, JUMPsem not only recapitulated the kinase activity patterns identified by the other tools but also discovered two unique kinase activity clusters that the others missed [28]. Furthermore, a quantitative performance assessment using benchmark datasets revealed that JUMPsem achieved slightly higher precision than IKAP across various thresholds [28].

Its utility extends beyond phosphorylation. Applied to ubiquitomics and acetylomics datasets, JUMPsem successfully identified E3 ubiquitin ligases and histone acetyltransferases (HATs) with significantly altered activity under different stress conditions and across breast cancer tumor samples, respectively [28]. This demonstrates its versatility as a general-purpose tool for enzyme activity inference.

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

Implementing these computational tools effectively requires a foundation in standardized experimental and bioinformatics protocols. The following workflow diagram and detailed methodology outline the process from sample preparation to biological insight.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for inferring enzyme activity from PTM data.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

The successful application of tools like JUMPsem relies on a multi-stage process, each with critical steps:

Sample Preparation and LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Protein Extraction and Digestion: Cells or tissues are lysed under denaturing conditions. Proteins are extracted, reduced, alkylated, and digested into peptides using a protease like trypsin.