Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: A Sustainable Strategy for Modern Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of chemoenzymatic synthesis for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs).

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients: A Sustainable Strategy for Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of chemoenzymatic synthesis for Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). It explores the foundational principles that make biocatalytic strategies a sustainable and selective alternative to traditional chemical methods. The scope extends to state-of-the-art methodologies, including enzyme discovery, engineering, and the design of multi-enzymatic cascades, illustrated with successful industrial case studies like ipatasertib and molnupiravir. The article also addresses key challenges in biocatalyst compatibility and stability, offering troubleshooting and optimization strategies rooted in protein engineering and computational design. Finally, it presents a comparative analysis of chemoenzymatic versus purely chemical routes, validating the approach through metrics of efficiency, cost, and environmental impact, and discusses future directions for this transformative technology in biomedical research.

The Rise of Biocatalysis: Foundational Principles and Strategic Advantages in API Synthesis

Chemoenzymatic synthesis represents a powerful hybrid methodology that strategically integrates enzymatic transformations with traditional chemical synthesis in a single synthetic sequence [1] [2]. This approach capitalizes on the complementary strengths of both catalytic worlds: the exceptional selectivity (stereo-, chemo-, and regio-), mild reaction conditions, and environmentally friendly profile of biocatalysts, combined with the broad substrate scope and well-established versatility of chemical methods [1] [3]. In the pharmaceutical industry, this synergy has enabled more efficient and sustainable manufacturing routes to complex molecules, including Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs), addressing long-standing challenges in synthetic efficiency and process sustainability [1].

The fundamental advantage of chemoenzymatic strategies lies in their ability to streamline synthetic routes. Enzymatic steps often eliminate the need for protecting groups and can simplify technology by shortening synthetic sequences and reducing reliance on specialized chemical equipment [1]. Furthermore, biocatalytic methods typically operate under mild conditions (ambient temperature and pressure, neutral pH) with superior atom economy, minimizing waste generation and environmental impact compared to traditional catalytic strategies that often require harsh conditions and involve toxic metals [1].

Key Applications in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Synthesis of mRNA Vaccine Components

The chemoenzymatic synthesis of pseudouridine-5′-triphosphate (ΨTP) and its N1-methylated derivative (m1ΨTP) exemplifies the power of this approach for producing critical pharmaceutical building blocks. These compounds are essential cost-driving components of mRNA vaccines, with m1ΨTP representing the second highest cost in mRNA vaccine manufacturing [4].

A recent integrated chemoenzymatic approach demonstrated a highly efficient route to m1ΨTP, combining a biocatalytic cascade for C–C bond formation with chemical methylation and enzymatic phosphorylation [4]. The process achieved m1ΨTP production in up to 68% overall yield from uridine at a concentration of approximately 50 mg/mL and a scale of ~200 mg of isolated product, showcasing the scalability of this methodology [4].

Table 1: Key Enzymes in the Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of m1ΨTP

| Enzyme | Source | Reaction Catalyzed | Key Activity |

|---|---|---|---|

| UMP Kinase | Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Phosphorylation of ΨMP to ΨDP | ~100 U/mg with ΨMP; 0.3 U/mg with m1ΨMP |

| Acetate Kinase (AcK) | Escherichia coli | Phosphorylation of ΨDP/m1ΨDP to ΨTP/m1ΨTP | 40 U/mg (ΨDP); 200 U/mg (m1ΨDP) |

| C–Glycosidase | Various | ΨMP formation from ribose-5-phosphate and uracil | Key C–C bond formation |

The experimental workflow for m1ΨTP synthesis involves three main stages:

- Biocatalytic Cascade Rearrangement: Uridine is converted to ΨMP using a multi-enzyme cascade, achieving excellent yields (95%) at high substrate concentrations (~1 mol/L) [4].

- Chemical Methylation: ΨMP is selectively protected and methylated at the N1 position using dimethyl sulfate, demonstrating the strategic integration of chemical synthesis where no efficient biocatalytic alternative exists [4].

- Enzyme Cascade Phosphorylation: The methylated intermediate (m1ΨMP) is converted to the final triphosphate (m1ΨTP) using a kinase cascade with ATP regeneration from acetyl phosphate, driven by the discovered promiscuous activities of UMPK and AcK [4].

This chemoenzymatic route offered significantly improved process metrics compared to purely chemical synthesis, including enhanced reaction efficiency and sustainability [4].

Synthesis of Natural Products and APIs

Chemoenzymatic approaches have revolutionized the synthesis of complex natural products and their analogs, enabling access to chiral building blocks and late-stage intermediates that are challenging to produce by conventional methods [2]. Notable applications include:

- Precise Oxyfunctionalization: Iron-dependent enzymes such as dioxygenases and cytochrome P450 monooxygenases enable selective C–H activation and oxidation of inert positions on terpene scaffolds and other complex structures [2]. For example, engineered P450BM3 variants have been used for early-stage hydroxylation in the synthesis of meroterpenoids like polysin [2].

- Convergent Coupling Reactions: Enzymes such as P450 monooxygenases and laccases have been employed for selective heterodimerization and homodimerization reactions, forming carbon-carbon and carbon-oxygen bonds with excellent stereocontrol [2]. This approach has been successfully applied in the synthesis of naseseazine alkaloids and lignans [2].

- Dynamic Kinetic Resolutions: Thermostable amino acid transferases have been used to prepare enantioenriched β-methylated amino acids through dynamic kinetic resolution, providing access to building blocks with vicinal stereocenters for natural product synthesis [2].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Chemoenzymatic vs. Traditional Synthesis

| Parameter | Traditional Chemical Synthesis | Chemoenzymatic Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Step Count | Often high (e.g., 7 steps for sporothriolide) [5] | Fewer steps, more direct routes [5] |

| Overall Yield | Moderate (e.g., 21% for sporothriolide) [5] | Typically higher yields |

| Stereoselectivity | Requires extensive catalyst screening | Innate, often >99% ee [1] |

| Environmental Impact | High carbon intensity, toxic waste | Reduced waste, milder conditions [1] |

| Structural Complexity | Handles diverse scaffolds | Efficient for complex chiral centers |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of m1ΨTP

Principle: This protocol describes the integrated chemoenzymatic synthesis of m1ΨTP from uridine, combining enzymatic cascade reactions for C–C bond formation and phosphorylation with chemical methylation [4].

Materials:

- Uridine (starting material, ≥98%)

- Recombinant enzymes: C–glycosidase, UMP kinase (from S. cerevisiae), Acetate kinase (from E. coli)

- Dimethyl sulfate (methylating agent)

- ATP and acetyl phosphate (phosphate donors)

- Immobilized lipase (for protection strategies)

- Standard laboratory equipment: bioreactor, HPLC system, LC-MS

Procedure:

Enzymatic Synthesis of ΨMP from Uridine:

- Dissolve uridine (1 mol/L) in appropriate aqueous buffer.

- Add the multi-enzyme cascade system (C–glycosidase and auxiliary enzymes).

- Incubate at 30-37°C with agitation until reaction completion (monitor by HPLC).

- Recover ΨMP by filtration to remove enzymes (yield: ~95%) [4].

Chemical Methylation of ΨMP to m1ΨMP:

- Protect the ΨMP using acetonide protection strategy.

- Dissolve protected ΨMP in appropriate organic solvent.

- Add dimethyl sulfate (1.2 equiv) slowly with stirring under controlled temperature.

- Quench the reaction and deprotect to obtain m1ΨMP.

- Purify by chromatography or crystallization.

Enzymatic Phosphorylation of m1ΨMP to m1ΨTP:

- Dissolve m1ΨMP (50 mg/mL) in phosphorylation buffer.

- Add UMP kinase (S. cerevisiae), acetate kinase (E. coli), ATP, and acetyl phosphate.

- Incubate at 30°C with monitoring of phosphate transfer.

- After completion, recover m1ΨTP by precipitation or chromatography.

- Overall isolated yield: ~68% from uridine at 200 mg scale [4].

Analytical Methods:

- Monitor reactions by HPLC and LC-MS.

- Characterize final product by ¹H NMR, ³¹P NMR, and mass spectrometry.

- Confirm purity >95% by analytical HPLC.

Protocol: Dynamic Kinetic Resolution for Chiral Amine Synthesis

Principle: This protocol describes the synthesis of chiral amines via imine reductases (IREDs) using a kinetic resolution approach, applicable to API intermediates such as cinacalcet analogs [1].

Materials:

- Imine reductase enzymes (e.g., IR-G02 variant)

- Amine substrates (bulky secondary and tertiary amines)

- Co-factor regeneration system (glucose dehydrogenase/NADPH)

- Standard bioreactor setup with pH and temperature control

Procedure:

Reaction Setup:

- Prepare buffer solution (pH 7.0-7.5) containing amine substrate (100 g/L).

- Add imine reductase (IRED) and co-factor regeneration system.

Biocatalytic Reaction:

- Incubate at 30°C with continuous monitoring of conversion.

- Maintain pH throughout the reaction.

Product Recovery:

- Terminate reaction at ~48% conversion for kinetic resolution.

- Extract product and separate enantiomers.

- Recover chiral amine with >99% enantiomeric excess [1].

Computational Tools for Synthesis Planning

Recent advances in computational synthesis planning have significantly enhanced our ability to design efficient chemoenzymatic routes. These tools help researchers navigate the vast reaction space of combined enzymatic and chemical transformations.

Table 3: Computational Tools for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Planning

| Tool Name | Strategy | Key Features | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| minChemBio [6] | Transition minimization | Minimizes transitions between chemical and biological reactions | Synthesis of 2,5-furandicarboxylic acid from glucose |

| ACERetro [7] | Asynchronous search algorithm | Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore) to prioritize reaction types | Route design for ethambutol and Epidiolex |

| SPScore Framework [7] | Unified step-by-step and bypass | MLP-trained scoring function based on molecular fingerprints | Retrospective analysis of published routes |

The SPScore framework, trained on 437,781 organic reactions (from USPTO) and 37,939 enzymatic reactions (from ECREACT), demonstrates particular utility for pharmaceutical applications. It employs molecular fingerprints (ECFP4, MAP4) with a multilayer perceptron model to evaluate the synthetic potential of molecules through either enzymatic or organic reactions, effectively guiding retrosynthetic planning [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of chemoenzymatic synthesis requires careful selection of enzymes, reagents, and materials. The following table outlines key components for developing chemoenzymatic processes.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidoreductases | Imine reductases (IREDs), Ketoreductases (KReds) | Asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines and alcohols |

| Transferases | Glycosyltransferases, Methyltransferases | Sugar transfer, methylation reactions |

| Hydrolases | Lipases (Candida rugosa, Eversa Transform 2.0) | Hydrolysis, esterification, transesterification |

| Lyases | Aromatic prenyltransferases, Asparaginyl ligases | C–C bond formation, bioconjugation |

| Co-factors | NAD(P)H, ATP, Acetyl phosphate | Energy transfer, redox reactions, phosphorylation |

| Reaction Engineering | Immobilized enzymes, Flow reactors | Process intensification, enzyme reuse |

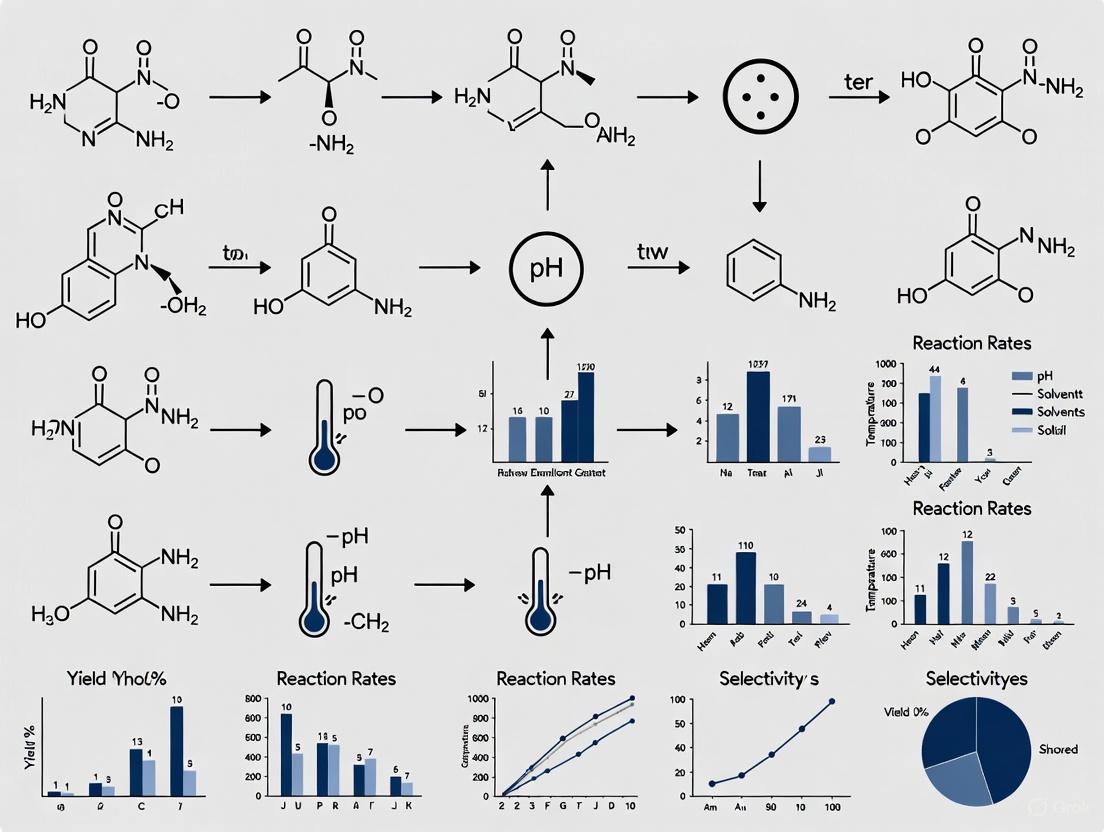

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow and experimental process for developing a chemoenzymatic synthesis, integrating both computational planning and laboratory execution.

Diagram 1: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Workflow

Chemoenzymatic synthesis represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical manufacturing, successfully bridging the gap between chemical and biological catalysis. By leveraging the complementary strengths of both approaches—the exceptional selectivity and sustainability of enzymatic transformations with the versatility and broad substrate scope of chemical methods—this strategy enables more efficient, sustainable, and cost-effective routes to complex pharmaceutical targets. The continued advancement of enzyme engineering, computational planning tools, and process integration methodologies will further expand the capabilities of chemoenzymatic synthesis, solidifying its role as a cornerstone technology in modern pharmaceutical development.

Chemoenzymatic synthesis, which integrates enzymatic and traditional chemical transformations, has emerged as a powerful paradigm in modern organic synthesis, particularly for the construction of complex Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs). This approach strategically leverages the complementary strengths of both biocatalytic and chemocatalytic methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, the core advantages translate into tangible benefits: the ability to access stereochemically complex intermediates with high purity, reduce the environmental footprint of synthetic processes, and develop more efficient and economical routes to target molecules. This document details these advantages through specific application notes and experimental protocols, providing a practical framework for implementation in API research.

Core Advantages and Supporting Data

The integration of enzymatic steps into synthetic pathways offers distinct and measurable benefits over traditional chemical methods. The data below quantitatively summarizes these core advantages, providing a clear comparison for research scientists.

Table 1: Quantitative Advantages of Chemoenzymatic Synthesis in API Development

| Advantage | Traditional Chemical Approach | Chemoenzymatic Approach | Key Quantitative Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Superior Selectivity | Often requires protecting groups, chiral auxiliaries, or resolution; may yield racemic mixtures or diastereomers. | Highly stereoselective transformations without extensive protection/deprotection. | E.g., Synthesis of an ipatasertib precursor with ≥98% conversion and 99.7% diastereomeric excess [1]. |

| Mild Reaction Conditions | Frequently employs strong acids/bases, high temperatures/pressures, and heavy metal catalysts. | Typically performed in aqueous buffers at neutral pH, ambient temperature and pressure. | E.g., Operational stability of engineered glycoside-3-oxidase increased 10-fold under process conditions [8]. |

| Enhanced Sustainability | High E-factor*; use of volatile organic solvents; significant energy input. | Reduced step-count; biodegradable catalysts (enzymes); lower energy consumption. | E.g., Synthesis of molnupiravir was shortened by 70% with a sevenfold higher yield [7]. |

| Streamlined Synthesis | Longer synthetic routes with multiple isolation and purification steps. | Concise routes, often in one-pot cascades, minimizing intermediates. | E.g., Novel D-allose route achieved 81% overall yield, avoiding laborious purification [8]. |

Note: E-factor is defined as the ratio of the mass of waste generated to the mass of product obtained.

Application Note: Synthesis of an Ipatasertib Precursor

Objective: To achieve the highly stereoselective reduction of a ketone intermediate to the corresponding (R,R)-trans alcohol, a key building block for the API Ipatasertib, a potent protein kinase B (Akt) inhibitor [1].

Experimental Protocol

Materials:

- Ketone Substrate: 100 g L⁻¹ concentration in reaction buffer.

- Biocatalyst: Engineered ketoreductase (KRED) from Sporidiobolus salmonicolor (10-amino acid substituted variant).

- Cofactor: NADPH (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate).

- Buffer: 50 mM Potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0.

- Co-solvent: Isopropanol (20% v/v) for substrate solubility and cofactor regeneration.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable bioreactor, charge the potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Add the ketone substrate and isopropanol, stirring until the substrate is fully dissolved.

- Enzyme and Cofactor Addition: Add the engineered KRED to a final concentration of 5 g L⁻¹ and NADPH to a final concentration of 0.2 mM.

- Biocatalytic Reduction: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30°C with constant agitation (200 rpm) for 30 hours. Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or GC.

- Work-up: After 30 hours, extract the product using ethyl acetate (3 x 200 mL). Combine the organic layers and dry over anhydrous sodium sulfate.

- Purification: Concentrate the organic extract under reduced pressure. Purify the crude product using silica gel column chromatography (eluent: hexane/ethyl acetate) to isolate the desired (R,R)-trans alcohol.

Analysis: The final product is analyzed by chiral HPLC to determine diastereomeric excess (de) and conversion yield. The protocol typically achieves ≥98% conversion and a diastereomeric excess of 99.7% (R,R-trans) [1].

Workflow and Reagent Solutions

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for the chemoenzymatic reduction process.

Diagram 1: Chemoenzymatic reduction workflow for Ipatasertib precursor.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Ketoreductase Protocol

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered KRED | Biocatalyst for stereoselective reduction. | Variant with 64-fold higher kcat than wild-type; improved robustness [1]. |

| NADPH | Cofactor; hydride donor for the reduction. | Catalytic quantity sufficient; system regenerated via isopropanol oxidation. |

| Isopropanol (IPA) | Co-solvent & cosubstrate. | Enhances substrate solubility and serves as sacrificial substrate for cofactor regeneration. |

| Potassium Phosphate Buffer | Reaction medium. | Maintains optimal pH (7.0) for enzymatic activity and stability. |

Application Note: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of D-Allose

Objective: To develop a regio- and stereoselective synthesis of the rare sugar D-allose, a potential API with applications as a non-caloric sweetener and therapeutic agent, using an engineered glycoside-3-oxidase (G3Ox) [8].

Experimental Protocol

Materials:

- Substrate: 1-O-benzyl-D-glucoside.

- Biocatalyst: Engineered glycoside-3-oxidase (PsG3Ox) from Pseudomonas sp.

- Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl buffer, pH 7.5.

- Reducing Agent: Sodium borohydride (NaBH₄).

- Deprotection Reagent: Hydrogen (H₂) and Palladium on carbon (Pd/C, 10% w/w) catalyst.

Procedure:

- Enzymatic Oxidation: Dissolve 1-O-benzyl-D-glucoside (10 mM) in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.5). Add the engineered PsG3Ox and incubate at 30°C with agitation for 4-6 hours. Monitor the oxidation (formation of the 3-keto derivative) by TLC or HPLC.

- Stereoselective Chemical Reduction: Upon completion of the oxidation, cool the reaction mixture to 0°C. Slowly add a slight excess of sodium borohydride (1.2 equiv) with stirring. Maintain the temperature at 0°C for 1 hour to ensure stereoselective reduction to the D-allose derivative.

- Quenching and Isolation: Carefully quench the excess NaBH₄ by adding acetone. Extract the product with ethyl acetate, dry the organic phase over Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under vacuum.

- Deprotection: Dissolve the crude product in methanol. Add a catalytic amount of Pd/C (10% w/w) and subject the mixture to a hydrogen atmosphere (1-2 bar H₂) for 12 hours. Filter the reaction mixture through a celite pad to remove the catalyst.

- Purification: Concentrate the filtrate and purify the product via recrystallization from ethanol/water to obtain pure D-allose.

Analysis: The identity and purity of D-allose are confirmed by [1H/13C] NMR and specific rotation analysis. This chemo-enzymatic process achieves an overall yield of 81%, avoiding complex protection/deprotection strategies and laborious purifications [8].

Workflow and Reagent Solutions

The synthetic route for D-allose is outlined below, highlighting the integration of enzymatic and chemical steps.

Diagram 2: Chemoenzymatic synthesis workflow for D-allose.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for D-Allose Synthesis

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered G3Ox | Biocatalyst for regioselective C3 oxidation. | Variant with 20-fold improved catalytic activity for D-Glc from directed evolution [8]. |

| 1-O-Benzyl-D-glucoside | Substrate. | C1 protection ensures exclusive oxidation at the C3 position. |

| Sodium Borohydride (NaBH₄) | Chemical reducing agent. | Provides a cis-reduction, yielding the desired D-allose stereochemistry. |

| Palladium on Carbon (Pd/C) | Heterogeneous catalyst. | Catalyzes the hydrogenolytic cleavage of the benzyl protecting group. |

Computational Tools in Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

The adoption of computational tools is becoming integral to advancing chemoenzymatic strategies. These tools aid in enzyme engineering, reaction prediction, and synthesis planning, thereby accelerating API development.

Computer-Aided Synthesis Planning (CASP): Tools like ACERetro, guided by a Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore), can efficiently plan hybrid synthesis routes by evaluating whether an enzymatic or organic reaction is more promising for a given molecule. This has been shown to find hybrid routes for 46% more molecules compared to previous state-of-the-art tools [7].

Protein Engineering via Computational Design: Computational strategies, such as stabilizing mutation scanning combined with Rosetta-based protein design, have successfully improved enzyme properties. For instance, this approach enabled the engineering of a diterpene glycosyltransferase (UGT76G1) with a 9 °C increase in melting temperature (Tm) and a 2.5-fold increase in product yield [1].

The integration of enzymatic transformations into the synthetic pathways of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) represents a paradigm shift in modern pharmaceutical research and development. Chemoenzymatic synthesis, which strategically combines the precision of biocatalysis with the versatility of traditional organic chemistry, offers compelling advantages for constructing complex drug molecules. These hybrid approaches leverage the excellent selectivity and mild reaction conditions of enzymes to address long-standing synthetic challenges, often simplifying routes by eliminating protecting group strategies and reducing environmental impact [9]. This article outlines four key conceptual frameworks for the successful integration of enzymes into API synthesis, providing detailed application notes and experimental protocols to guide researchers in implementing these strategies.

Framework 1: Computational Retrosynthesis Planning

Conceptual Basis

Computer-aided synthesis planning (CASP) represents a transformative approach for designing efficient chemoenzymatic routes by heuristically navigating the vast space of possible enzymatic and organic reactions. These tools leverage algorithms to identify optimal pathways that capitalize on the complementary strengths of both catalytic worlds—primarily the broad substrate scope of chemical reactions and the exceptional stereoselectivity of enzymatic transformations [7]. The core innovation in this domain is the development of scoring systems, such as the Synthetic Potential Score (SPScore), which evaluates whether a molecule is more promisingly synthesized through enzymatic or organic reactions based on molecular structure and historical reaction data [7].

Application Protocol

- Tool Selection: Implement computational tools like ACERetro or minChemBio that integrate both chemical and enzymatic reaction databases. These platforms use mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) or asynchronous search algorithms to identify pathways with minimal transitions between chemical and biological steps, thereby reducing costly purification processes [7] [10].

- Route Optimization: Apply the SPScore-guided synthesis route optimization workflow: (1) Compute SPScores for each molecule in an existing or predicted route to identify steps with significant deviation between predicted and actual reaction types; (2) Search for alternative reaction types for the identified steps; (3) Append promising results to create an optimized hybrid route [7].

- Feasibility Assessment: Utilize auxiliary tools like dGPredictor to evaluate the thermodynamic feasibility of proposed enzymatic steps, estimating standard Gibbs energy change at physiologically relevant conditions (pH 7.0, ionic strength 0.1 M) [10].

Experimental Implementation

The following diagram illustrates the computational workflow for chemoenzymatic synthesis planning:

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Retrosynthesis Tools

| Tool Name | Algorithm Type | Reaction Databases | Success Rate (%) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ACERetro | Asynchronous search | USPTO (chemical), ECREACT (enzymatic) | 46% more molecules than previous tools | Unified step-by-step and bypass strategies |

| minChemBio | Mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) | USPTO, MetaNetX | Case-dependent (2-24 solutions per target) | Minimizes transitions between chemical and biological steps |

| ASKCOS | Monte Carlo Tree Search | Reaxys, USPTO | Not specifically reported | Broad chemical reaction coverage |

| RetroBioCat | AND-OR Tree Search | Expert-curated enzymatic rules | Not specifically reported | Specialized in biocatalytic transformations |

Framework 2: Late-Stage Functionalization of Complex Intermediates

Conceptual Basis

This framework employs enzymes for the precise regio- and stereoselective modification of advanced synthetic intermediates that are challenging to functionalize using traditional chemical methods. The approach is particularly valuable for introducing hydroxyl groups, performing oxidative rearrangements, or installing chiral centers in complex molecular architectures with precision difficult to achieve chemically [11]. Notably, cytochrome P450 monooxygenases and Fe(II)/2-oxoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases have demonstrated remarkable capabilities for functionalizing inert C-H bonds in synthetic intermediates with predictable stereochemical outcomes [11].

Application Protocol

- Enzyme Selection: Identify candidate enzymes based on known biosynthetic pathways or substrate similarity. For example, Fe(II)/2OG-dependent dioxygenases like Bsc9 catalyze oxidative allylic rearrangements in diterpene natural products such as cotylenol and brassicicenes [11].

- Reaction Optimization: Screen homologous enzymes and employ directed evolution to enhance activity toward non-natural substrates. In the synthesis of cotylenol, researchers identified a homolog MoBsc9 from Magnaporthe oryzae with improved activity toward the synthetic intermediate [11].

- Process Development: Scale up the enzymatic reaction using immobilized enzyme preparations or whole-cell biocatalysts to enhance stability and facilitate catalyst recycling.

Experimental Implementation

Protocol: Enzymatic Late-Stage Oxidation of a Synthetic Diterpene Scaffold

Materials:

- Synthetic diterpene substrate (21, 100 mg)

- Purified Bsc9 dioxygenase or homolog (20 mg)

- Fe(II) sulfate (10 mM)

- 2-oxoglutarate (5 mM)

- Ascorbate (2 mM)

- Tris-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5)

- Ethyl acetate

- Anhydrous magnesium sulfate

Procedure:

- Prepare the reaction mixture by dissolving the substrate (21) in Tris-HCl buffer (10 mL) with gentle heating if necessary.

- Add Fe(II) sulfate (100 μL of 1M stock), 2-oxoglutarate (500 μL of 100 mM stock), and ascorbate (200 μL of 100 mM stock) to the solution.

- Initiate the reaction by adding the purified Bsc9 enzyme (20 mg) and incubate at 30°C with shaking at 150 rpm.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS over 12-24 hours.

- Terminate the reaction by extracting three times with equal volumes of ethyl acetate.

- Combine organic layers, dry over anhydrous magnesium sulfate, filter, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purify the product (22) using flash chromatography (silica gel, hexane/ethyl acetate gradient).

Expected Outcome: The protocol typically achieves approximately 20% yield of the oxidized product (22) with 50% conversion, demonstrating the diastereocontrolled hydroxylation at C3 with concurrent double bond transposition [11].

Framework 3: Modular Pathway Design with Minimal Transitions

Conceptual Basis

This framework focuses on designing synthetic routes that minimize transitions between chemical and enzymatic steps, thereby reducing purification requirements and improving overall process efficiency. The approach recognizes that separation and purification steps account for a significant portion of synthetic costs, particularly when switching between chemical and biological reaction environments [10]. Optimal pathway design maintains reaction compatibility through careful solvent selection, intermediate design, and reaction sequence optimization.

Application Protocol

- Pathway Analysis: Use tools like minChemBio to identify pathways with minimal modality transitions while maintaining reasonable overall yields [10].

- Solvent Engineering: Develop compatible solvent systems that maintain enzyme activity while solubilizing organic compounds. Co-solvent systems like aqueous DMSO or methanol are often effective.

- One-Pot Reactions: Design multi-step sequences that proceed without intermediate isolation, particularly for chemoenzymatic cascades where the product of a chemical reaction serves directly as substrate for an enzymatic transformation.

Experimental Implementation

Case Study: Synthesis of 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid (FDCA) from Glucose

- Pathway Design: minChemBio identified 23 distinct chemo-enzymatic pathways from glucose to FDCA, prioritizing routes with minimal transitions between chemical and enzymatic steps [10].

Implementation Strategy:

- Begin with enzymatic steps to convert glucose to 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) using engineered microbial systems.

- Transition to chemical oxidation of HMF to FDCA using supported metal catalysts.

- Alternatively, employ a fully enzymatic pathway using oxidase enzymes if the reaction kinetics and yields are favorable.

Process Metrics: The optimal pathway reduced transitions by 40% compared to conventional approaches, significantly lowering estimated production costs [10].

The following diagram illustrates the minimal transitions pathway design:

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Chemoenzymatic Synthesis

| Reagent/Enzyme Class | Specific Examples | Function in API Synthesis | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Imine Reductases (IREDs) | IR-G02 variant | Asymmetric synthesis of chiral amines | Wide substrate range; used in cinacalcet analog synthesis (>99% ee) [9] |

| Ketoreductases (KREDs) | Engineered KR from Sporidiobolus salmonicolor | Diastereoselective reduction for ipatasertib synthesis | 64-fold higher apparent kcat vs wild-type; 99.7% de [9] |

| Fe(II)/2OG-dependent Dioxygenases | Bsc9, MoBsc9 | Oxidative allylic rearrangement | Regio- and stereocontrolled C-H activation; requires Fe(II), 2-oxoglutarate cofactors [11] |

| Transaminases | Not specified | Amine introduction from ketone precursors | PLP-dependent; useful for chiral amine synthesis |

| P450 Monooxygenases | Engineered P450s from directed evolution | Late-stage C-H functionalization | Used in synthesis of nigelladine A, mitrephorone A [11] |

| Asparaginyl Ligases | Engineered variants | Site-specific bioconjugation | Appreciable activity across wide pH range [9] |

Framework 4: Industrial Biocatalytic Process Integration

Conceptual Basis

This framework addresses the practical challenges of implementing enzymatic steps in industrial API synthesis, focusing on enzyme robustness, scalability, and economic viability. Key considerations include enzyme immobilization for reusability, compatibility with industrial process conditions, and integration with continuous flow systems to enhance productivity and control [9] [12]. The approach leverages advances in protein engineering, media engineering, and reactor design to transform promising laboratory biocatalysis into industrially viable processes [9].

Application Protocol

- Enzyme Engineering: Employ computational design and directed evolution to enhance enzyme stability, activity, and solvent tolerance. For example, computational design of diterpene glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 increased Tm by 9°C and reduced byproduct formation [9].

- Immobilization Strategies: Develop customized immobilization protocols using carrier-based or carrier-free methods (cross-linked enzyme aggregates) to enhance enzyme stability and enable continuous processing.

- Process Intensification: Implement continuous flow bioreactors to improve mass transfer, reaction control, and productivity compared to batch systems [12].

Experimental Implementation

Protocol: Continuous Flow Chemoenzymatic Synthesis in Packed Bed Reactors

Reactor Setup:

- Enzyme immobilization: Covalently immobilize ketoreductase (KRED) onto functionalized silica beads.

- Reactor configuration: Pack the immobilized enzyme into a jacketed column (10 cm length, 1 cm diameter).

- System integration: Connect the enzymatic reactor in series with a preceding chemical step reactor.

Process Parameters:

- Flow rate: 0.5-2.0 mL/min

- Temperature: 30-35°C

- Substrate concentration: 50-100 g/L

- Co-factor recycling: Employ a co-immobilized NADPH recycling system

Operation:

- Equilibrate the system with reaction buffer until stable flow and temperature are achieved.

- Introduce substrate solution continuously using a precision HPLC pump.

- Monitor output stream by inline UV spectroscopy or periodic LC-MS analysis.

- Collect product fractions for downstream processing.

Performance Metrics: Continuous operation for >200 hours with <10% activity loss, diastereomeric excess maintained at >99%, productivity of 5 g/L/h [12].

The strategic integration of enzymes into API synthesis represents a maturing field with demonstrated potential to transform pharmaceutical manufacturing. The four frameworks presented—computational retrosynthesis planning, late-stage functionalization, modular pathway design, and industrial process integration—provide complementary approaches for harnessing the power of biocatalysis in drug synthesis. As enzyme discovery, engineering, and process technologies continue to advance, chemoenzymatic approaches will increasingly become the standard for efficient and sustainable API manufacturing. Successful implementation requires interdisciplinary collaboration between synthetic chemists, enzymologists, and process engineers to navigate the unique challenges and opportunities presented by these hybrid synthetic strategies.

Application Notes

The integration of biocatalysis into active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) synthesis has become a cornerstone of modern, sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. Ketoreductases (KREDs), transaminases (ATAs), and imine reductases (IREDs) represent three pivotal enzyme classes that enable highly efficient and stereoselective synthesis of chiral building blocks, overcoming limitations of traditional chemical methods [3]. Their compatibility with chemoenzymatic cascades allows for the design of streamlined, one-pot synthetic routes, reducing waste and purification steps [13].

Ketoreductases (KREDs)

KREDs are NAD(P)H-dependent oxidoreductases that catalyze the asymmetric reduction of prochiral ketones to enantiopure alcohols, which are invaluable chiral intermediates.

- Industrial Scalability: KRED processes are demonstrated at pilot and production scales. A key application is the synthesis of (R)-Tetrahydrothiophene-3-ol, a chiral precursor to the antibacterial prodrug sulopenem. Starting from tetrahydrothiophene-3-one, an engineered KRED achieves the transformation in a single step with 99.3% enantiomeric excess (e.e.) at a 100 kg scale [14].

- Bridged and Cyclic Ketones: KREDs exhibit exceptional selectivity across a wide range of cyclic ketones, including five-, six-, and seven-membered rings, and bridged ring systems. The reduction of 4,4-dimethoxytetrahydro-2H-pyran-3-one to its corresponding (R)-α-hydroxyketal proceeds with >99% e.e. using only 0.1 weight% enzyme, demonstrating high productivity [14].

- Emerging Applications: Recent studies have repurposed KREDs for novel reactions under photoexcitation conditions. Specifically, KREDs can catalyze the radical hydrodehalogenation of α-bromolactones, leveraging excited-state nicotinamide cofactors to enact a stereodetermining hydrogen atom transfer, thus expanding the functional group tolerance and reaction scope of these enzymes [14].

Transaminases (ATAs)

ATAs (EC 2.6.1.) are pyridoxal phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes that transfer an amino group from an amino donor to a prochiral ketone or aldehyde, yielding enantiomerically pure amines and amino acids [13].

- Synthesis of Non-Canonical Amino Acids (NcAAs): ATAs are critical for producing NcAAs, which are essential building blocks in pharmaceuticals. Integrating NcAAs into peptide-based drugs enhances their metabolic stability, bioavailability, and biological activity. For instance, the global market for Sitagliptin, a drug reliant on a chiral amine intermediate, is projected to reach \$60.09 billion by 2031, highlighting the economic significance of efficient synthetic routes [13].

- Cascade Reactions: ATAs are effectively employed in (chemo-)enzymatic cascades. A prominent example is the one-pot synthesis of cathine, which combines an (S)-selective lyase with an (S)-selective ATA. This cascade drives the reaction to completion by removing equilibrium constraints, resulting in the product with >97% e.e. [13]. Cascade systems also address the challenge of cofactor regeneration. KREDs are often used in popular NAD(P)H regeneration cascades. The co-product NAD(P)+ from the KRED reaction is recycled back to NAD(P)H by a second enzyme, such as glucose dehydrogenase, at the expense of a cheap sacrificial substrate like glucose [13].

Imine Reductases (IREDs)

IREDs are NAD(P)H-dependent enzymes that catalyze the asymmetric reduction of cyclic imines to chiral amines. A subset, sometimes called reductive aminases (RedAms), can catalyze the direct reductive amination of ketones with amines, forming carbon-nitrogen bonds in a single step [15] [16].

- Reductive Amination for API Synthesis: IREDs are extremely attractive for reductive amination, one of the most frequently employed reactions in API synthesis, as they perform the transformation with high efficiency and stereoselectivity under mild conditions [17]. They can access secondary and tertiary amines that are challenging to synthesize by other enzymatic methods. Their application has been scaled up to kg and ton scales in the pharmaceutical sector [15].

- Substrate Scope and Engineering: The versatility of IRED-catalyzed reductive amination was historically limited to small, hydrophobic amines. However, enzyme discovery and engineering have expanded their scope. For example, IR77 from Ensifer adhaerens can couple cyclohexanone with bulky bicyclic amines like isoindoline and octahydrocyclopenta(c)pyrrole, scaffolds found in pharmaceuticals such as the diuretic clorexolone [15]. Rational design of IR77, leading to the A208N mutant, improved activity and stability, enabling preparative-scale amination in isolated yields of up to 93% [15].

- Diverse Enzyme Sources: The repertoire of IREDs is being expanded by mining genetically divergent biosynthetic pathways. This functional genomics approach has uncovered new enzyme families for imine reduction in previously unannotated sequence space, providing more biocatalytic tools for synthetic applications [17]. Furthermore, the distinction between "ketoreductases" and "imine reductases" can be fluid. Promiscuous Short-Chain Dehydrogenases/Reductases (SDRs) known for keto-reduction have been rationally engineered to possess imine-reducing activity, demonstrating the functional plasticity of these enzyme families [18].

Table 1: Key Applications of Enzymes in API Synthesis

| Enzyme Class | Reaction Catalyzed | Key Application | Scale Demonstrated | Stereoselectivity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ketoreductase (KRED) | Ketone → Chiral Alcohol | (R)-Tetrahydrothiophene-3-ol for Sulopenem [14] | 100 kg | >99% e.e. |

| Transaminase (ATA) | Ketone → Chiral Amine/Amino Acid | Synthesis of Non-Canonical Amino Acids (NcAAs) [13] | Industrial (e.g., Sitagliptin precursor) [13] | >97% e.e. |

| Imine Reductase (IRED) | Imine → Chiral Amine / Reductive Amination | Reductive amination of cyclohexanone with bulky amines [15] | kg to ton scale [15] | >99% e.e. [16] |

Table 2: Comparative Performance of IREDs in Reductive Amination

| IRED / RedAm | Ketone Substrate | Amine Substrate | Conversion/Yield | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IR77 (wild-type) | Cyclohexanone | Benzylamine | 78% Conversion [15] | [15] |

| IR77 (wild-type) | Cyclohexanone | Pyrrolidine | 97% Conversion [15] | [15] |

| IR77 (A208N mutant) | Cyclohexanone | Isoindoline | 93% Isolated Yield [15] | [15] |

| IR-G36 (engineered) | N-Boc-3-piperidinone | 2-Phenylethylamine | 98% Conversion, >99% e.e. [15] | [15] |

| Metagenomic IREDs | α-Ketoesters | Various Amines | High conversion, excellent e.e. [16] | [16] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: KRED-Catalyzed Synthesis of (R)-Tetrahydrothiophene-3-ol

Objective: To produce (R)-Tetrahydrothiophene-3-ol from tetrahydrothiophene-3-one using an engineered ketoreductase on a gram to kilogram scale [14].

Materials:

- Enzyme: Engineered KRED variant (e.g., Codexis KRED)

- Substrate: Tetrahydrothiophene-3-one

- Cofactor: NADPH (catalytic amount)

- Cofactor Regeneration System: Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) and Glucose

- Buffer: Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0)

- Solvent: Water or aqueous/organic biphasic system as required

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable bioreactor, charge the potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0).

- Substrate Addition: Add tetrahydrothiophene-3-one to a final concentration of 100 g/L.

- Enzyme and Cofactor Addition:

- Add the engineered KRED (loading optimized for desired reaction rate, typically 1-5 g/L).

- Add a catalytic amount of NADPH (e.g., 0.1-0.5 mM).

- Add Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) and an excess of glucose (e.g., 1.2 equiv relative to ketone) for continuous NADPH regeneration [14].

- Reaction Conditions:

- Maintain the reaction temperature at 30°C.

- Agitate the mixture sufficiently to ensure mixing and mass transfer.

- Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or GC until completion (>99% conversion).

- Work-up and Isolation:

- Upon completion, separate the aqueous layer if a biphasic system is used.

- Extract the product with a suitable organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Dry the combined organic layers over anhydrous sodium sulfate.

- Concentrate the solution under reduced pressure to obtain the crude product.

- Purify further by distillation or crystallization if necessary. The protocol has been successfully demonstrated at a 100 kg scale [14].

Protocol 2: ATA-Catalyzed Synthesis of Chiral Amines in a Cascade

Objective: To synthesize cathine in a one-pot cascade using an (S)-selective lyase and an (S)-selective amine transaminase (ATA) [13].

Materials:

- Enzymes: (S)-selective benzaldehyde lyase from Acetobacter pasteurianus, (S)-selective ATA from Chromobacterium violaceum

- Substrates: Pyruvate, Benzaldehyde

- Amino Donor: e.g., Isopropylamine

- Cofactor: Pyridoxal Phosphate (PLP, 0.1 mM)

- Buffer: Tris-HCl or phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare the reaction mixture in a single pot with the buffer (100 mM, pH 7.5).

- Cofactor Addition: Add PLP to a final concentration of 0.1 mM.

- Substrate Addition:

- Add pyruvate and benzaldehyde (e.g., 50 mM each).

- Add the amino donor isopropylamine (e.g., 1.5-2.0 equiv).

- Enzyme Addition:

- Initiate the cascade by simultaneously adding the (S)-selective benzaldehyde lyase and the (S)-selective ATA.

- Use appropriate enzyme loadings, typically determined experimentally (e.g., 1-5 mg/mL of each enzyme).

- Reaction Conditions:

- Incubate at 30-37°C with shaking.

- Monitor the reaction by chiral HPLC or GC until completion.

- Reaction Driving Force: The lyase-ATA cascade drives the reaction to completion by converting the undesired (R)-PAC intermediate back to benzaldehyde and acetaldehyde, shifting the equilibrium and allowing for high yields and enantiomeric excess (>97% e.e.) [13].

- Work-up and Isolation:

- Quench the reaction by adjusting the pH or denaturing enzymes with heat or solvent.

- Extract the product (cathine) with an organic solvent.

- Purify the product using standard techniques like flash chromatography.

Protocol 3: IRED-Catalyzed Reductive Amination with Bulky Amines

Objective: To perform the reductive amination of cyclohexanone with the bulky amine isoindoline using engineered IRED IR77-A208N on a preparative scale [15].

Materials:

- Enzyme: Purified IRED IR77-A208N mutant

- Substrates: Cyclohexanone, Isoindoline

- Cofactor: NADPH (catalytic amount)

- Cofactor Regeneration System: Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) and Glucose

- Buffer: Potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0)

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a reaction vessel, add the potassium phosphate buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0).

- Substrate Addition:

- Add cyclohexanone to a final concentration of 50 mM.

- Add isoindoline (1.2 equiv, 60 mM). The use of a slight excess of amine favors imine formation.

- Enzyme and Cofactor Addition:

- Add purified IR77-A208N enzyme (loading optimized for activity, e.g., 1-5 mg/mL).

- Add a catalytic amount of NADPH (e.g., 0.2 mM).

- Add GDH and an excess of glucose (e.g., 5 equiv relative to ketone) for cofactor regeneration.

- Reaction Conditions:

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking for 24-48 hours.

- Monitor reaction progress by GC or LC-MS.

- Work-up and Isolation:

- After confirmation of high conversion, extract the reaction mixture with tert-butyl methyl ether (TBME) or ethyl acetate.

- Dry the organic phase over anhydrous sodium sulfate and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purify the crude product by flash chromatography or recrystallization to obtain the pure secondary amine product. This protocol has been shown to provide isolated yields up to 93% [15].

Visualization of Workflows

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis Planning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the SPScore-guided asynchronous search algorithm (ACERetro) for designing hybrid chemoenzymatic synthesis routes [7].

SPScore-Guided Synthesis Planning

Integrated KRED Cofactor Regeneration Cascade

This diagram shows the enzymatic cascade for ketone reduction coupled with NADPH regeneration, a common and critical system for efficient biocatalysis [13].

KRED Cofactor Recycling System

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Biocatalytic API Synthesis

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered KRED | Stereoselective reduction of ketones to chiral alcohols. | Synthesis of (R)-Tetrahydrothiophene-3-ol, a sulopenem precursor [14]. |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Regenerates NAD(P)H from NAD(P)+ using glucose as a sacrificial substrate. | Integrated cofactor recycling in KRED and IRED reactions [14] [13]. |

| NAD(P)H Cofactor | Serves as the hydride source in reductase-catalyzed reductions. | Catalytic amount required for initiating KRED and IRED reactions [14] [15]. |

| Amine Transaminase (ATA) | Transfers an amino group to a prochiral ketone, producing chiral amines. | Synthesis of non-canonical amino acids and chiral amine pharmacophores [13]. |

| Pyridoxal Phosphate (PLP) | Essential cofactor for transaminases; acts as an electron sink. | Must be supplemented for ATA-catalyzed reactions [13]. |

| Imine Reductase (IRED) | Catalyzes the reduction of imines or direct reductive amination. | One-pot synthesis of N-substituted α-amino esters from α-ketoesters [16]. |

| Glucose | Inexpensive sacrificial substrate for cofactor regeneration systems. | Serves as the electron donor for GDH in NAD(P)H recycling cascades [14] [13]. |

From Discovery to Manufacturing: Methodologies and Industrial Applications in API Synthesis

The integration of biocatalytic strategies into the synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) represents a paradigm shift towards more sustainable and efficient drug manufacturing processes. Chemoenzymatic synthesis leverages the exceptional chemo-, regio-, and stereoselectivity of enzymes to construct complex chiral molecules, often outperforming traditional synthetic catalysts [19] [1]. This approach enables synthetic routes that are shorter, generate less toxic waste, and avoid the need for extensive protecting group strategies, thereby improving cost-efficiency [19] [1]. The field is currently experiencing a third wave of biocatalysis, where enzymes are tailored to fit industrial process conditions rather than building processes around the needs of the biocatalyst [20].

For pharmaceutical researchers and development professionals, the biocatalytic toolbox has become indispensable for preparing enantiopure intermediates under mild reaction conditions (ambient temperature and pressure, neutral pH) [19]. Enzymatic methods are particularly crucial for manufacturing chiral drugs, where the chemical and optical purity of APIs are paramount factors for therapeutic activity and safety [19]. Recent advances in enzyme discovery, protein engineering, and reaction engineering have dramatically expanded the repertoire of biocatalytic transformations available for API synthesis, moving this technology from purely academic exploration to industrially viable manufacturing processes [1] [20].

Advances in Enzyme Discovery Methodologies

Computational and AI-Driven Enzyme Discovery

The discovery of novel biocatalysts has been revolutionized by artificial intelligence and computational methods that can predict enzyme function and identify valuable catalysts from vast sequence databases.

Deep Learning for Kinetic Parameter Prediction: The CataPro model represents a significant advancement in predicting enzyme kinetic parameters ((k{cat}), (Km), and (k{cat}/Km)) using deep learning [21]. This framework utilizes pre-trained protein language models (ProtT5-XL-UniRef50) for enzyme sequence representation and combines molecular fingerprints (MolT5 embeddings and MACCS keys) for substrate characterization [21]. CataPro demonstrates enhanced accuracy and generalization ability on unbiased datasets, enabling more reliable prediction of catalytic efficiency before experimental validation [21].

Structure-Based Discovery with AlphaFold: AI-driven structure prediction tools have dramatically accelerated enzyme discovery. AlphaFold2 accurately predicts three-dimensional protein structures from amino acid sequences, enabling rapid modeling of previously uncharacterized enzymes [22]. The recent introduction of AlphaFold3 extends these capabilities to predict protein-ligand interactions, providing crucial insights into enzyme-substrate relationships, particularly for non-natural substrates relevant to pharmaceutical synthesis [22].

Genome and Metagenome Mining: Bioinformatics tools enable the systematic exploration of natural enzyme diversity without the need for cultivation. Software packages such as antiSMASH identify biosynthetic gene clusters, while EnzymeMiner automates the search for soluble enzymes with desired activities across diverse organisms [22]. These approaches leverage the evolutionary optimization that natural enzymes have undergone over millions of years, providing an excellent starting point for further engineering [22].

Table 1: Computational Tools for Enzyme Discovery

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in API Synthesis | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CataPro [21] | Prediction of enzyme kinetic parameters | Identify enzymes with high catalytic efficiency for specific substrates | Combines protein language models with molecular fingerprints |

| AlphaFold2/3 [22] | Protein structure and protein-ligand interaction prediction | Understand substrate binding and guide enzyme engineering | High-accuracy structure prediction without experimental data |

| antiSMASH [22] | Identification of biosynthetic gene clusters | Discover novel enzymes from natural product pathways | Predicts functionalities based on gene cluster similarities |

| EnzymeMiner [22] | Automated search for soluble enzymes | Find stable, expressible enzyme candidates | Filters based on user-defined criteria (activity, stability) |

High-Throughput Experimental Discovery

Complementary to computational approaches, experimental methods enable the functional identification of novel enzymatic activities.

Sequence-Function Relationships: Rational enzyme selection from sequence databases can be guided by analyzing sequence-function relationships. For example, screening 4-phenol oxidoreductases from 292 sequences based on first-shell residue properties within the catalytic pocket has successfully identified enzymes with desired functionalities [1]. The computational tool A2CA can guide this selection process by correlating sequence features with catalytic properties [1].

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR): This phylogenetic approach predicts ancestral enzyme sequences from multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic trees [1]. Ancestral enzymes often exhibit enhanced thermostability and broader substrate promiscuity, making them valuable starting points for engineering campaigns. For instance, a hyper-thermostable ancestral L-amino acid oxidase (HTAncLAAO2) was designed for the chemoenzymatic synthesis of D-tryptophan from L-tryptophan at preparative scale [19] [1].

Enzyme Engineering Strategies for Optimized Biocatalysts

Computational Design and Engineering

Computational methods enable the rational engineering of enzyme properties to meet the rigorous demands of industrial API synthesis.

Stability Enhancement through Computational Design: Improving enzyme thermostability is critical for industrial applications. A computational design strategy combining stabilizing mutation scanning with Rosetta-based protein design successfully engineered a variant of diterpene glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 with a 9°C increase in melting temperature and a 2.5-fold product yield increase [1]. This enhanced stability is crucial for the industrial production of steviol glucosides as natural sweet-tasting compounds [1].

Machine Learning-Guided Engineering: Machine learning algorithms can efficiently navigate the vast sequence space to identify beneficial mutations. In the engineering of a ketoreductase for ipatasertib synthesis, machine learning-aided enzyme engineering enabled the design of smaller, more focused mutant libraries for screening [1]. This approach resulted in a variant with ten amino acid substitutions exhibiting a 64-fold higher apparent (k_{cat}) and robust performance under process conditions, achieving ≥98% conversion and 99.7% diastereomeric excess for the alcohol intermediate [1].

Mechanistic Investigation for Engineering: Quantum chemical calculations provide insights into enzymatic mechanisms that guide engineering efforts. For norcoclaurine synthase from Thalictrum flavum (TfNCS), computational studies revealed the rate-limiting step and differential energy barriers for reactions with different enantiomers of α-methylphenylacetaldehyde, identifying key residues responsible for stereospecificity in the Pictet-Spengler reaction [19] [1].

Directed Evolution and High-Throughput Screening

Despite advances in computational design, experimental evolution remains a powerful tool for optimizing enzyme performance.

Gene Diversification Methods: Creating genetic diversity is the first step in directed evolution. Error-prone PCR (epPCR) introduces random mutations using low-fidelity DNA polymerases, with mutation frequencies adjustable through experimental conditions (e.g., magnesium levels, manganese addition, unbalanced dNTP concentrations) [22]. Mutazyme polymerase can counterbalance the mutation bias introduced by Taq polymerase, creating more diverse mutant libraries [22].

High-Throughput Screening Platforms: Advanced screening methods are essential for evaluating mutant libraries. Microfluidic screening platforms represent the cutting edge, capable of analyzing approximately 2,000 variants per second—roughly one million times faster than conventional plate screening [23]. Such ultra-high-throughput methods were instrumental in engineering a computationally designed retro-aldolase through 13 rounds of evolution, achieving a 3×10^7-fold rate enhancement and making the artificial enzyme competitive with natural catalysts [23].

Increasing-Molecule-Volume Screening: Specialized screening approaches can address specific engineering challenges. For imine reductases (IREDs), an increasing-molecule-volume screening method identified enzymes with preference for bulky amine substrates, enabling the gram-scale synthesis of a cinacalcet API analog with >99% enantiomeric excess [1].

Table 2: Key Engineering Strategies for Pharmaceutical Biocatalysts

| Engineering Strategy | Key Methodology | Pharmaceutical Application Example | Performance Enhancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Stability Design [1] | Rosetta-based protein design with mutation scanning | Diterpene glycosyltransferase UGT76G1 for steviol glucosides | 9°C increase in Tm, 2.5× yield increase |

| Machine Learning-Guided Engineering [1] | ML-aided library design combined with mutational scanning | Ketoreductase for ipatasertib intermediate synthesis | 64× higher kcat, 99.7% de |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction [1] | Phylogenetic prediction of ancestral sequences | L-amino acid oxidase for D-tryptophan production | Enhanced thermostability and activity |

| Structure-Guided Engineering [19] [1] | Crystal structure analysis to guide mutations | α-Oxoamine synthase (ThAOS) for expanded substrate range | Acceptance of simplified N-acetylcysteamine thioesters |

| Directed Evolution with HTS [23] | Microfluidic screening of mutant libraries | Retro-aldolase for C-C bond formation | 3×10^7-fold rate enhancement |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Objective: Enhance activity and diastereoselectivity of a ketoreductase from Sporidiobolus salmonicolor for the synthesis of an alcohol intermediate in ipatasertib manufacturing.

Materials and Reagents:

- Wild-type ketoreductase gene from S. salmonicolor

- Site-directed mutagenesis kit

- Expression vector and host (e.g., pET vector in E. coli)

- LB media and appropriate antibiotics

- IPTG for induction

- Substrate: prochiral ketone (100 g/L stock solution)

- Cofactor: NADPH or NADH

- Analytical HPLC with chiral column

- Plate reader for initial activity screening

Procedure:

- Library Creation: Use mutational scanning to identify beneficial mutation sites. Apply machine learning algorithms to design focused mutant libraries covering 10-20 positions.

- Expression and Screening: Express variant libraries in 96-well format. Induce with 0.1 mM IPTG at 16°C for 16-20 hours.

- Primary Activity Assay: Perform whole-cell biotransformations with 10 g/L ketone substrate. Monitor conversion via HPLC or GC.

- Hit Validation: Scale up promising variants (≥80% conversion) for detailed kinetic characterization.

- Process Optimization: Evaluate best variant under process conditions: 100 g/L ketone substrate, 30 h reaction time, determine diastereomeric excess by chiral HPLC.

- Scale-up: Implement optimal variant in final biocatalytic process, targeting ≥98% conversion and ≥99.7% diastereomeric excess (R,R-trans).

Objective: Total synthesis of spirosorbicillinols A-C through chemoenzymatic Diels-Alder cycloaddition.

Materials and Reagents:

- Sorbicillin

- Oxidoreductase SorbC or chemical oxidant (bis(trifluoroacetoxy)iodo)benzene

- Scytolide or epi-scytolide dienophile

- Shikimic acid or quinic acid as chiral starting materials

- Dimethyl diazomalonate

- Rhodium acetate catalyst

- Eschenmoser's salt

- Dess-Martin periodinane

- Sodium triacetoxyborohydride

- Appropriate organic solvents (THF, methanol, dichloromethane)

- NMR solvents for structural verification

Procedure:

- Sorbicillinol Generation: Convert sorbicillin to sorbicillinol using either:

- Dienophile Synthesis: Prepare scytolide from shikimic acid through 7-9 step chemical synthesis involving protection, rhodium-catalyzed condensation, and lactonization.

- Diels-Alder Cycloaddition: Combine sorbicillinol and scytolide dienophile in appropriate solvent. Monitor reaction by TLC or LC-MS.

- Product Separation: Isulate endo and exo cycloaddition products using preparative HPLC or column chromatography.

- Structural Verification: Characterize spirosorbicillinols A-C by NMR and optical rotation comparison to natural products.

Application in Pharmaceutical Synthesis: Case Studies

Synthesis of Chiral Amines via Imine Reductases

Chiral amines are crucial building blocks for numerous pharmaceuticals, and imine reductases (IREDs) have emerged as powerful biocatalysts for their asymmetric synthesis.

Industrial Challenge: Traditional chemical synthesis of chiral amines often relies on metal-catalyzed asymmetric hydrogenation, which can suffer from limited stereoselectivity and the need for precious metal catalysts [20]. Additionally, the structural diversity of pharmaceutical amines, especially secondary and tertiary amines, requires a flexible biocatalytic approach [20].

Biocatalytic Solution: Imine reductases identified from Actinomycetes exhibit remarkable promiscuity toward bulky amine substrates [19]. Using an increasing-molecule-volume screening method, researchers identified IRED-G02 with broad substrate range, capable of synthesizing over 135 secondary and tertiary amines [1].

Pharmaceutical Application: This IRED platform enabled the gram-scale synthesis of a cinacalcet API analog using a kinetic resolution approach with >99% enantiomeric excess and 48% conversion [1]. The ability to efficiently produce structurally diverse chiral amines significantly expands the toolbox for manufacturing amine-containing pharmaceuticals.

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Spirosorbicillinols

The spirosorbicillinols represent a class of fungal natural products with bioactive potential, whose synthesis showcases the power of combining chemical and enzymatic methods.

Synthetic Challenge: These complex molecules feature a characteristic bicyclo[2.2.2]octane backbone that is challenging to construct with the correct stereochemistry using purely chemical methods [24].

Chemoenzymatic Solution: A convergent synthesis combines enzymatic generation of the highly reactive sorbicillinol diene with chemically synthesized scytolide-derived dienophiles [24]. The key Diels-Alder cycloaddition proceeds efficiently to form the core structure.

Result: This approach provided unifying access to all natural spirosorbicillinols and unnatural diastereomers, enabling further biological evaluation of these compounds [24]. The successful synthesis demonstrates how enzymatic and chemical steps can be seamlessly integrated to access complex natural product scaffolds relevant to pharmaceutical discovery.

Synthesis of D-Allose via Engineered Glycoside-3-Oxidase

Rare sugars like D-allose possess valuable biological activities but are challenging to synthesize with traditional methods.

Industrial Challenge: Conventional chemical synthesis of D-allose requires multiple protection-deprotection steps, leading to low overall yields and cumbersome purification [25].

Biocatalytic Solution: A bacterial glycoside-3-oxidase was engineered through seven rounds of directed evolution, resulting in a 20-fold increase in catalytic activity for D-glucose and 10-fold enhanced operational stability [25].

Chemoenzymatic Process: The optimized process uses engineered oxidase for regioselective oxidation of 1-O-benzyl-D-glucoside at C3, followed by stereoselective chemical reduction and deprotection to yield D-allose with 81% overall yield [25]. This efficient route avoids laborious purification and complicated protection strategies, demonstrating the power of combining enzymatic selectivity with chemical synthesis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Discovery and Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Key Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| CataPro Software | Predicts enzyme kinetic parameters ((k{cat}), (Km)) | Prioritize enzyme candidates from metagenomic libraries | [21] |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Protein structure and ligand interaction prediction | Guide enzyme engineering without crystal structures | [22] |

| Unnatural Amino Acids | Expand catalytic functionality | Incorporate N δ-methyl histidine for enhanced hydrolysis activity | [23] |

| Glycoside-3-oxidase (Engineered) | Regioselective oxidation of sugars | Synthesize D-allose via chemoenzymatic route | [25] |

| Imine Reductases (IREDs) | Reductive amination for chiral amine synthesis | Produce cinacalcet analog with >99% ee | [19] [1] |

| SorbC Oxidoreductase | Oxidative dearomatization of sorbicillin | Generate sorbicillinol for Diels-Alder cyclization | [24] |

| RetroBioCat Software | Biochemical pathway design | Plan chemo-enzymatic routes to target molecules | [10] |

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

Diagram Title: Integrated Workflow for Pharmaceutical Biocatalyst Development

Diagram Title: Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of D-Allose

The synthesis of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients (APIs) is increasingly leveraging the power of cascade reactions, which combine multiple catalytic cycles in a single vessel. One-pot multi-enzyme and chemoenzymatic systems integrate the exceptional selectivity and mild reaction conditions of biocatalysis with the broad synthetic scope of traditional chemistry [3] [7]. This approach minimizes purification steps, reduces environmental impact, and can access complex molecular architectures that are challenging to produce by conventional methods. Within API research, these strategies are pivotal for streamlining the synthesis of chiral intermediates, functionalized scaffolds, and complex natural product-derived therapeutics, often leading to shortened synthetic routes and improved overall yields [3] [26]. This Application Note provides detailed protocols and key considerations for the implementation of these cascade systems, framed within the context of modern pharmaceutical development.

One-Pot Multi-Enzyme Cascade Synthesis of Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs)

Non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) are vital building blocks for pharmaceutical peptides, prodrugs, and biomaterials. The following protocol details a modular multi-enzyme cascade for the synthesis of triazole-functionalized ncAAs from glycerol, an abundant and sustainable feedstock [27].

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To synthesize a triazole-functionalized ncAA (e.g., Triazole-l-alanine) from glycerol in a one-pot, multi-enzyme system.

Principle: The pathway is partitioned into three functional modules that operate concurrently: Module I oxidizes glycerol to D-glycerate; Module II converts D-glycerate to O-phospho-L-serine (OPS) with cofactor regeneration; and Module III utilizes a key engineered enzyme, O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS), to catalyze C–N bond formation between an OPS-derived intermediate and a non-natural nucleophile (1,2,4-triazole) [27].

Table 1: Reagents and Enzymes for ncAA Synthesis

| Component | Function | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Glycerol | Low-cost, sustainable substrate | Commercially available |

| Alditol Oxidase (AldO) | Oxidizes glycerol to D-glycerate | Streptomyces coelicolor or other microbial sources |

| Catalase | Degrades H₂O₂ byproduct, protects other enzymes | Bovine liver or microbial |

| D-glycerate-3-kinase (G3K) | Phosphorylates D-glycerate | Methylorubrum extorquens |

| Phosphoserine Aminotransferase (PSAT) | Catalyzes transamination to form OPS | E. coli |

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) | Key enzyme for C–N bond formation; uses α-aminoacrylate intermediate | Engineered variant from archaea (e.g., Aeropyrum pernix) |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) | Regenerates ATP from polyphosphate | E. coli or Klebsiella pneumoniae |

| 1,2,4-Triazole | Nucleophile for side-chain functionalization | Commercially available |

| NAD+/NADH, PLP | Essential cofactors | Commercially available |

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a final volume of 10 mL, combine the following in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0):

- Glycerol (100 mM)

- Nucleophile (1,2,4-triazole, 40 mM)

- MgCl₂ (10 mM, as a cofactor for kinases)

- Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate (PLP, 0.1 mM)

- NAD⁺ (0.5 mM)

- Polyphosphate (20 mM, for ATP regeneration)

- Sodium phosphate (10 mM, for OPS synthesis)

- 2-Oxoglutarate (5 mM) and L-Glutamate (5 mM, for amino donor regeneration)

Enzyme Addition: Introduce the clarified lysates or purified enzymes to the reaction mixture. The recommended proportions (by volume) are:

- Module I: AldO lysate (5%), Catalase lysate (2%)

- Module II: G3K lysate (5%), PGDH lysate (5%), PSAT lysate (5%), PPK lysate (5%)

- Module III: Engineered OPSS lysate (10%)

Reaction Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30-37°C with constant agitation (200 rpm) for 24-48 hours. Monitor reaction progress by HPLC or LC-MS.

Product Isolation: After confirmation of high conversion, terminate the reaction by heat treatment (75°C for 10 min). Centrifuge to remove precipitated proteins. The ncAA can be purified from the supernatant using ion-exchange chromatography or preparative HPLC. Lyophilize the pure fractions to obtain the product as a solid.

Key Optimization Note: The catalytic efficiency of the key enzyme OPSS was enhanced 5.6-fold through directed evolution, which was critical for achieving high product titers [27]. This system has been demonstrated to be scalable to a 2-liter reaction volume.

The workflow for this multi-enzyme cascade is as follows:

Chemoenzymatic Synthesis of Tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) Alkaloids

Tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) alkaloids are a prominent class of bioactive compounds with applications as analgesics, antitussives, and potential therapeutics for cancer and neurodegenerative diseases [26]. This protocol describes a chemoenzymatic cascade for the regioselective methylation of THIQs, a key diversification step in optimizing their pharmacological properties.

Experimental Protocol

Objective: To perform a one-pot, multi-step synthesis and regioselective methylation of a THIQ alkaloid, incorporating in situ cofactor regeneration for S-adenosylmethionine (SAM).

Principle: The cascade begins with a Pictet–Spengler reaction catalyzed by norcoclaurine synthase (NCS) to form the THIQ core. Subsequently, methyltransferases (MTs) are used to regioselectively methylate the scaffold. A critical cofactor regeneration system is employed to circumvent the high cost of SAM, using methionine adenosyltransferase (MAT) and methylthioadenosine nucleosidase (MTAN) [26].

Table 2: Key Reagents for THIQ Synthesis and Diversification

| Reagent/Enzyme | Function | Role in API Synthesis |

|---|---|---|

| Norcoclaurine Synthase (NCS) | Catalyzes Pictet–Spengler reaction to form THIQ core from dopamine and aldehyde | Creates chiral scaffold with high enantiopurity for drug candidates. |

| Catechol-O-Methyltransferase (e.g., RnCOMT) | Transfers methyl group from SAM to hydroxyl(s) on THIQ core | Improves metabolic stability, alters bioavailability, and diversifies lead compounds. |

| Methionine Adenosyltransferase (MAT) | Generates SAM from ATP and L-methionine | Regenerates expensive cofactor in situ, making process cost-effective for larger scales. |

| Methylthioadenosine Nucleosidase (MTAN) | Cleaves inhibitory byproduct S-adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) | Prevents product inhibition and drives methylation equilibrium toward completion. |

| Dopamine | Substrate for core scaffold formation | Natural precursor; commercially available building block. |

| Aldehyde Derivative | Substrate for core scaffold formation | Varies R-group on final THIQ, enabling library synthesis. |

| L-Methionine & ATP | Substrates for SAM regeneration | Low-cost, stable alternatives to direct SAM addition. |

Procedure:

- Pictet–Spengler Reaction: In a single pot, combine dopamine (5-20 mM) and the desired aldehyde substrate (e.g., 4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, 25-100 mM) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5). Initiate the reaction by adding a clarified lysate of Thalictrum flavum NCS (TfNCS, 10% v/v). Incubate at 30°C with shaking until HPLC analysis confirms full consumption of dopamine (typically 2-4 hours). It is critical to consume all dopamine before methylation to prevent its methylation as a side reaction.

Methylation with Cofactor Regeneration: To the same pot, add without purification:

- ATP (5 mM)

- L-Methionine (10 mM)

- Clarified lysate of the selected methyltransferase (e.g., RnCOMT or MxSafC, 10% v/v)

- Clarified lysates of E. coli MAT (EcMAT, 10% v/v) and E. coli MTAN (EcMTAN, 2.5% v/v)

Reaction Monitoring and Completion: Incubate the reaction at 30°C with shaking. Monitor the formation of methylated products by HPLC. The reaction is typically complete within 90 minutes to 6 hours, depending on the THIQ substrate and MT used.

Product Isolation: Quench the reaction by acidification (e.g., with 1M HCl) or heat treatment. Centrifuge to remove precipitated protein. The methylated THIQ product can be purified from the supernatant using solid-phase extraction or preparative HPLC. Characterize the product by NMR and MS to confirm regioselectivity and purity.

Key Findings: The regioselectivity of the methylation is highly dependent on the THIQ substrate structure. For instance, RnCOMT preferentially methylates the 6-OH position for THIQs with certain side chains (e.g., (S)-1, (S)-6), but switches to favor the 7-OH position for others (e.g., 9, 10). MxSafC can exhibit the opposite preference, allowing for strategic diversification [26]. Using this cascade, methylated THIQs were isolated with good yields and high regioselectivities.

The synthetic pathway and enzyme cascade are illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of cascade reactions relies on the availability and understanding of key reagents and materials. The following table catalogs essential solutions for the development of one-pot multi-enzyme and chemoenzymatic systems in API research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Cascade Reactions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Cascade Systems | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Maintains steady-state concentrations of expensive cofactors (e.g., ATP, NAD(P)H, SAM), drastically reducing process costs. | ATP: Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK). NAD+: Glucose/GluDH or formate/FDH. SAM: MAT/MTAN system is essential for scalable MT reactions [26]. |

| Engineered Enzyme Panels | Provides variants with enhanced activity, stability, or altered substrate specificity for non-natural substrates. | Directed evolution of OPSS increased catalytic efficiency 5.6-fold for C-N bond formation [27]. |

| Clarified Lysates | Crude cell extracts containing the desired enzymes; often used to simplify preparation and reduce costs versus purified enzymes. | Successfully used in THIQ methylation cascades, showing regioselectivities comparable to purified enzymes and streamlining the process [26]. |

| Stable Nucleophiles & Electrophiles | Serve as non-natural substrates for enzyme-catalyzed bond formation (e.g., C-S, C-Se, C-N). | Azide-, alkenyl-, and sulfur-containing compounds (e.g., 1,2,4-triazole, allyl mercaptan) for diversifying molecular scaffolds [27]. |