Decoding Biocatalysis: From Sequence to Function in Drug Development

This article explores the critical relationship between protein sequence and function in biocatalysis, a field increasingly vital for sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing.

Decoding Biocatalysis: From Sequence to Function in Drug Development

Abstract

This article explores the critical relationship between protein sequence and function in biocatalysis, a field increasingly vital for sustainable pharmaceutical manufacturing. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive analysis spanning foundational concepts, advanced methodologies like machine learning and ancestral sequence reconstruction, practical troubleshooting strategies, and rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this review serves as a strategic guide for leveraging sequence-function relationships to design efficient, stable, and novel biocatalysts for biomedical applications.

The Blueprint of Catalysis: Understanding Sequence-Function Fundamentals

The central dogma of molecular biology, which outlines the flow of genetic information from DNA to RNA to protein, provides the fundamental framework for understanding how protein sequence dictates structure and function. In biocatalysis, this principle translates to a sequence-structure-function relationship that enables researchers to predict and engineer enzymatic activity. This technical guide explores the current understanding of how protein sequences encode structural information that determines catalytic function, with specific emphasis on experimental and computational approaches advancing biocatalyst discovery and optimization. We examine high-throughput experimentation, machine learning methodologies, and structure-function continuum models that are transforming our ability to navigate the vast landscape of protein sequence space for biocatalytic applications.

The foundational principle of structural biology follows the sequence-structure-function paradigm, which states that a protein's sequence determines its structure, which in turn determines its function [1]. In biocatalysis, this paradigm provides the theoretical basis for enzyme discovery and engineering, enabling researchers to potentially predict catalytic function from genetic sequences alone. The application of biocatalysis in synthesis offers streamlined routes toward target molecules, tunable catalyst-controlled selectivity, and processes with improved sustainability [2]. However, biocatalysis implementation often carries substantial risk because identifying an enzyme capable of performing chemistry on a specific intermediate remains challenging [2] [3].

The underexploration of connections between chemical and protein sequence space constrains navigation between these two landscapes [2]. While similar protein sequences often give rise to similar structures and functions, research has revealed that similar protein functions can be achieved by different sequences and different structures [1]. This understanding has prompted a shift in focus across biological disciplines from obtaining structures to putting them into context and from sequence-based to sequence-structure-function-based meta-omics analyses [1].

Fundamental Principles: From Genetic Information to Functional Proteins

The Central Dogma and Protein Synthesis

The classical central molecular biology dogma describes a fundamental colinear and irreversible flow of genetic information within biological systems: information encoded in double-stranded DNA is transcribed into RNA and translated into protein [4]. This differential timing of gene expression determines cell lineage and ultimately produces the enzymatic machinery that catalyzes biochemical reactions. Although this framework remains valid, it has gradually expanded to include more complex interactions, with RNA now recognized as a primary determinant of cellular functional diversity [4].

The Structure-Function Continuum in Enzymes

The traditional binary structure-function relationship has evolved into a structure–function continuum model that incorporates the importance of both conformational flexibility and intrinsic disorder in protein function [5]. This continuum model recognizes that structure, conformational dynamics, and intrinsic disorder seamlessly lead to function, which does not necessarily have a one-to-one relationship with proteoforms arising from the same gene [5]. Enzymes predominantly feature structured regions near their catalytic sites, while regulatory regions often display higher levels of disorder that facilitate molecular interactions and post-translational modifications [5].

Table 1: Protein Structural States and Their Functional Implications in Biocatalysis

| Structural State | Structural Characteristics | Functional Roles in Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Ordered Domains | Stable secondary and tertiary structure; defined active sites | Catalytic activity; substrate binding; cofactor recognition |

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs) | Flexible regions without fixed structure; conformational heterogeneity | Regulatory functions; substrate capture ("fly-casting"); post-translational modification sites |

| Molten Globules | Compact collapsed structures with dynamic side chains | Folding intermediates; functional states in some enzymes |

| Native Coils/Pre-molten Globules | Extended conformations with high solvent accessibility | Large interaction surfaces; promiscuous binding capabilities |

Sequence Determinants of Structure and Function

Protein sequences encode structural information through physicochemical properties, patterns of hydrophobicity, charge distribution, and propensity for secondary structure formation. These sequence features direct folding pathways and determine final tertiary and quaternary structures. In enzymes, specific sequence motifs correspond to catalytic residues, binding pockets, and allosteric regulatory sites. The conservation of these motifs across evolution enables computational identification of potential enzymatic function from sequence alone [6].

Computational Approaches: Predicting Function from Sequence

Machine Learning for Enzyme Function Prediction

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a powerful approach for predicting enzyme function from sequence data. ML models can functionally annotate the staggering number of available protein sequences, which has increased by approximately 20-fold in recent years (from ~123 million in 2018 to >2.4 billion in 2023) [7]. These approaches accelerate the discovery of enzymes with useful activities by filtering natural diversity for properties such as stability, solubility, and catalytic function [7].

The SOLVE (Soft-Voting Optimized Learning for Versatile Enzymes) framework represents an advanced ML approach that uses only tokenized subsequences from primary protein sequences for classification [6]. This interpretable ML method utilizes an ensemble learning framework integrating random forest, light gradient boosting machine, and decision tree models with an optimized weighted strategy. The system distinguishes enzymes from non-enzymes and predicts Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers for both mono- and multi-functional enzymes across all four levels of the EC hierarchy [6].

Table 2: Machine Learning Approaches in Biocatalysis Research

| Method | Primary Approach | Applications in Biocatalysis | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOLVE | Ensemble learning with tokenized subsequences | Enzyme/non-enzyme classification; EC number prediction | High accuracy across EC hierarchy; interpretable results |

| CLEAN | Contrastive learning | Enzyme commission number prediction | Functional annotation of uncharacterized enzymes |

| Protein Language Models | Pattern recognition in sequence databases | Generation of novel biocatalysts; stability prediction | Zero-shot prediction without experimental data |

| AlphaFold | Structural prediction from sequence | Structure-function relationship analysis | Access to structural universe of proteins |

Navigating Sequence-Function Space

Machine learning assists in navigating the protein fitness landscape by training models on experimental data to prioritize which sets of mutations to test in enzyme engineering campaigns [7]. This approach helps analyze complex relationships in large datasets, identifying patterns challenging to detect otherwise. This capability is particularly important because experimental engineering campaigns typically sample only a small fraction of protein sequences and tend to focus on single mutational steps, potentially missing nonadditive effects of accumulating mutations [7].

Challenges in Computational Prediction

Despite promising advances, significant challenges remain in applying machine learning to biocatalysis. Data scarcity and quality represent a persistent bottleneck, as experimental datasets are typically small and can be inconsistent, hindering ML models from learning meaningful patterns [7]. Model transferability and generalization also present difficulties, as ML models trained with data from one protein family using specific substrates and reaction conditions may not generalize well to others [7].

Experimental Methodologies: Connecting Sequence to Function

High-Throughput Biocatalytic Reaction Discovery

Experimental approaches for connecting sequence to function have evolved to include high-throughput experimentation that profiles substrates sampled across chemical space with enzymes representing sequence diversity within a protein family [2]. This methodology involves conducting reactions that systematically explore enzyme-substrate compatibility, generating data to build machine learning models for navigating between sequence and function landscapes.

A representative example is the development of CATNIP (Compatibility Assessment Tool for NHI Enzymes and Substrates), which involved a two-phase effort relying on high-throughput experimentation to populate connections between productive substrate and enzyme pairs [2] [3]. This approach focused on α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes as a test case, selected for their practical advantages, including scalability and valuable oxidative transformations [2].

Library Design and Sequence Selection

To design a library of α-KG-dependent non-heme iron (NHI) enzymes representing sequence diversity, researchers gathered all sequences annotated to have the facial triad of iron-coordinating residues conserved for hydroxylases [2]. Using the Enzyme Function Initiative–Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST), 265,632 unique sequences were associated with this class. After reducing redundancy and removing clusters containing enzymes associated with primary metabolism, a sequence similarity network (SSN) consisting of 27,005 sequences was generated [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for High-Throughput Biocatalysis Research

| Reagent/Resource | Specifications | Experimental Function |

|---|---|---|

| aKGLib1 | 314 enzyme library representing α-KG-dependent NHI enzyme diversity | Protein expression and screening; sequence-structure-function mapping |

| pET-28b(+) Vector | E. coli expression vector with T7 lac promoter | Heterologous protein expression for library members |

| E. coli Expression Strains | BL21(DE3) or similar expression hosts | Recombinant protein production in 96-well format |

| α-Ketoglutarate | Co-substrate for NHI enzymes | Essential reaction component for enzymatic activity |

| Fe(II) Salts | Iron (II) sulfate or chloride | Cofactor supply for non-heme iron enzyme reactions |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | UV-Vis, fluorescence, or LC-MS based detection | Activity assessment across enzyme-substrate combinations |

From this network, 102 sequences were selected from the most populated cluster, 125 uncharacterized sequences from poorly annotated clusters, and 87 additional sequences of enzymes with known or proposed function, resulting in a 314-enzyme library (aKGLib1) [2]. The selected sequences showed an average sequence percent identity of 13.7%, indicating high library sequence diversity [2]. DNA for the library was synthesized and cloned into a pET-28b(+) expression vector, with E. coli cells transformed and overexpression carried out in 96-well-plate format [2].

Experimental Workflow for Sequence-Function Mapping

Protocol: High-Throughput Enzyme Screening for Function Annotation

Objective: To experimentally determine enzyme-substrate compatibility for sequence-function relationship mapping.

Materials:

- aKGLib1 (or equivalent enzyme library)

- pET-28b(+) expression vectors with library genes

- E. coli BL21(DE3) expression cells

- LB media with appropriate antibiotics

- IPTG (isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside) for induction

- Lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, 300 mM NaCl, pH 7.4)

- Substrate library representing chemical diversity

- Reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.4)

- α-Ketoglutarate (2 mM final concentration)

- Fe(II)SO₄ (0.5 mM final concentration)

- Ascorbate (2 mM final concentration)

- 96-well deep well plates for expression

- 96-well assay plates

- Microplate reader or LC-MS for detection

Method:

- Transformation and Expression:

- Transform E. coli BL21(DE3) with library plasmids

- Culture overnight in deep-well plates with antibiotics

- Dilute cultures and grow to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6-0.8)

- Induce protein expression with 0.5 mM IPTG

- Incubate at 18°C for 16-20 hours for protein production

Cell Harvest and Lysis:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (4000 × g, 10 minutes)

- Resuspend cell pellets in lysis buffer

- Lyse cells by sonication or chemical lysis

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation (14000 × g, 20 minutes)

Activity Screening:

- Prepare master mix containing reaction buffer, α-KG, Fe(II), and ascorbate

- Dispense master mix to 96-well assay plates

- Add substrate library compounds (100-500 μM final concentration)

- Initiate reactions by adding clarified lysates

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking for 2-16 hours

- Quench reactions with equal volume of organic solvent

Analysis and Data Processing:

- Analyze reaction mixtures by HPLC, LC-MS, or plate reader assays

- Quantify product formation using standard curves

- Normalize activity to protein concentration

- Classify enzyme-substrate pairs as productive or non-productive

This experimental workflow successfully identified more than 200 biocatalytic reactions and provided the data necessary to build a web-based toolkit for suggesting compatible substrates and enzymes for oxidative biocatalytic transformations [2].

Integration and Future Directions

Bridging Computational and Experimental Approaches

The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a powerful cycle for advancing sequence-function understanding in biocatalysis. Machine learning models generate hypotheses about enzyme function and compatibility, which are then tested experimentally. The resulting experimental data refine and improve the computational models, creating an iterative design-build-test-learn cycle that accelerates biocatalyst development [7].

This integrated approach is particularly valuable for addressing the challenge of limited annotated data. As noted by researchers in the field, "The next major step will be accumulating enough annotated enzyme data to unlock the 'functional universe.' ML should be able to give us tools that can predict enzyme activity, substrate scope, co-factors, optimal environments, etc. with high accuracy" [7].

Expanding Beyond Traditional Sequence-Structure-Function Relationships

Recent research suggests the need to expand beyond the traditional sequence-structure-function paradigm. The structure-function continuum model acknowledges that intrinsic disorder and conformational dynamics play crucial roles in enzyme function, particularly in regulatory processes and molecular interactions [5]. This understanding provides a more nuanced view of how sequence encodes functional information, recognizing that disordered regions and conformational flexibility contribute significantly to catalytic efficiency and regulation.

Additionally, the discovery that similar protein functions can be achieved by different sequences and different structures [1] suggests multiple evolutionary paths to similar functional outcomes. This realization has important implications for enzyme engineering, as it expands the potential sequence space for discovering or designing catalysts with desired functions.

Future Outlook

The field of biocatalysis is poised for continued advancement through deeper understanding of sequence-function relationships. Key areas for future development include:

- Improved functional annotation of the millions of uncharacterized enzyme sequences in databases

- Integration of structural dynamics into function prediction models

- Expansion to diverse enzyme classes beyond the currently well-studied families

- Development of generalized models that transfer learning across enzyme families

- Automated experimental workflows that close the loop between computation and experimentation

As these advances materialize, the central dogma of biocatalysis will continue to evolve, providing increasingly sophisticated frameworks for understanding how sequence dictates structure and function, and ultimately enabling more efficient design of biocatalysts for synthetic applications.

The exploration of sequence-function relationships represents a frontier in biocatalysis research, bridging the gap between protein sequence space and small-molecule chemical space. This technical guide examines contemporary strategies for navigating these vast landscapes, focusing on integrated experimental and computational approaches. We detail the development and application of high-throughput experimentation coupled with machine learning to establish predictive connections between sequence and function, using α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron enzymes as a case study. The challenges of data scarcity, annotation accuracy, and model generalizability are discussed alongside emerging solutions. This whitepramework provides researchers with methodologies to derisk biocatalytic reaction discovery and implementation, ultimately accelerating the development of enzymatic solutions for pharmaceutical synthesis and industrial applications.

The Sequence-Function Paradigm in Biocatalysis

The fundamental challenge in biocatalysis research lies in predicting enzymatic function from protein sequence data. With over 216 million annotated protein sequences available in public databases—a number that doubles approximately every 28 months—only a minuscule fraction of this functional landscape has been experimentally characterized [8]. This sequence-to-function gap constrains our ability to identify enzymes capable of performing specific chemical transformations on non-native substrates, particularly in pharmaceutical synthesis where biocatalysis offers advantages in selectivity, sustainability, and step-count reduction [2] [9].

The disconnect between enzyme discovery and commercial application remains a significant hurdle. While discovery platforms continue to improve in speed and sophistication, the industry still faces challenges in transitioning promising enzymes into high-yield, cost-effective manufacturing processes [10]. Bridging this gap requires integrated platforms that combine enzyme engineering, host strain development, and scalable fermentation from the project outset [10].

Experimental Approaches for Mapping Sequence Space

Library Design and Sequence Selection

Strategic library design begins with comprehensive sequence analysis to capture functional diversity within protein families. The Enzyme Function Initiative-Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST) enables researchers to generate sequence similarity networks (SSNs) that visualize relationships between sequences based on alignment scores [2] [8]. These networks facilitate informed sampling of sequence space by identifying distinct clusters that may correlate with functional variations.

Table 1: Key Bioinformatics Tools for Sequence Space Navigation

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Application in Biocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| EFI-EST | Generation of sequence similarity networks | Family-wide sequence relationship visualization [2] |

| CLEAN | Contrastive learning for enzyme annotation | Enzyme commission number prediction [2] |

| EnzymeMiner | Mining of soluble enzymes | Prediction of heterologous expression success in E. coli [7] |

| AlphaFold | Protein structure prediction | Access to the structural universe of enzymes [7] |

In a landmark study exploring α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron enzymes, researchers initially identified 265,632 unique sequences containing the conserved facial triad of iron-coordinating residues [2]. Through redundancy reduction and removal of clusters associated with primary metabolism, this was refined to 27,005 sequences for network analysis. Strategic sampling selected 314 enzymes representing: (1) 102 sequences from the most populated cluster, (2) 125 uncharacterized sequences from poorly annotated clusters, and (3) 87 enzymes with known or proposed functions [2]. This approach ensured coverage of both characterized and unexplored sequence regions.

High-Throughput Experimental Profiling

Experimental mapping of sequence-function relationships requires high-throughput methodologies to test enzyme libraries against diverse substrates. The BioCatSet1 dataset exemplifies this approach, capturing the reactivity of α-ketoglutarate-dependent NHI enzymes with over 100 substrates [11]. This systematic profiling generated more than 200 novel biocatalytic reactions, dramatically expanding known connections between this enzyme family and chemical space [2].

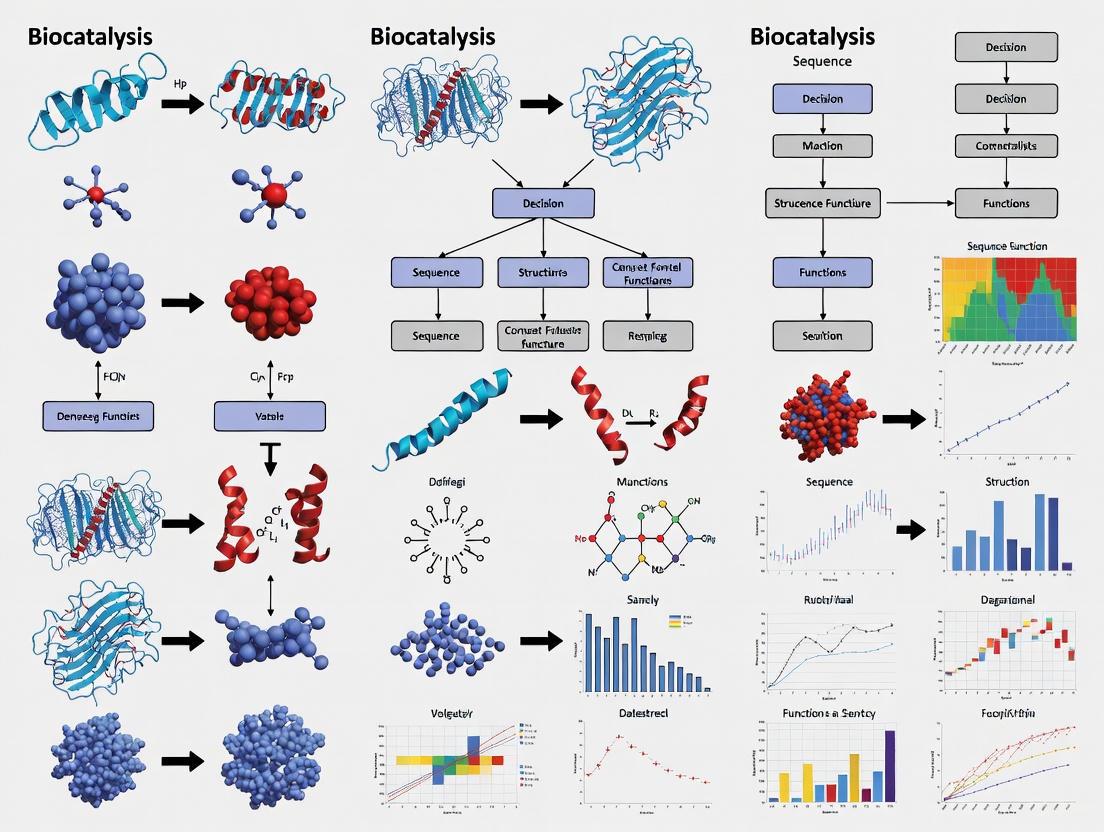

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for mapping sequence-function relationships through high-throughput screening.

Implementation requires robust protein expression systems, with E. coli serving as the primary host for many enzyme classes. In the α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzyme study, researchers achieved successful expression for 78% of library members, as confirmed by SDS-PAGE analysis of crude cell lysates [2]. This expression rate highlights the importance of codon optimization and expression screening in functional library design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequence-Function Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pET-28b(+) vector | Protein expression | Standard vector for heterologous expression in E. coli [2] |

| α-Ketoglutarate | Cofactor | Essential cosubstrate for α-KG-dependent NHI enzymes [2] |

| Ferrous iron | Cofactor | Fe(II) source for non-heme iron enzyme activation [2] |

| MetXtra discovery engine | Enzyme discovery | Proprietary platform for mining metagenomic sequences [10] |

| FireProtDB | Mutation database | Curated database of mutational effects on protein stability [7] |

| SoluProtMutDB | Solubility database | Resource for predicting mutation effects on solubility [7] |

Computational Integration and Machine Learning Approaches

Predictive Model Development

The experimental data generated through high-throughput profiling enables development of predictive machine learning models. The CATNIP (Compatibility Assessment Tool for Non-heme Iron Proteins) workflow exemplifies this approach, providing ranked lists of enzymes most likely to be compatible with a given substrate, or conversely, ranking potential substrates for a given enzyme sequence [2] [11]. This bidirectional predictive capability significantly derisks biocatalytic reaction planning.

Machine learning applications in biocatalysis face distinct challenges, primarily concerning data availability and quality. Experimental datasets are typically small and can be inconsistent, hindering ML models from learning meaningful patterns [7]. This challenge is particularly acute for predicting stereoselectivity, where dedicated databases cataloging enantiomeric excess values are scarce [12]. Potential solutions include implementing optimized strategies for initial data acquisition, adopting high-throughput stereoselectivity assays, and applying transfer learning approaches that leverage knowledge from well-characterized systems [7] [12].

Addressing Data Scarcity through Experimental Design

Systematic experimental design can mitigate data limitations in machine learning applications. Research indicates that sharing scientific data in standardized formats improves datasets used for ML, and importantly, including negative or unexplained results (when accurately confirmed) enhances model training [10]. Multi-task learning approaches that leverage data from related enzyme families can further address data scarcity issues [7].

For stereoselectivity prediction, researchers have proposed standardizing all measurements to relative activation energy differences (ΔΔG≠), which would unify enantiomeric excess (ee) and E values across different studies [12]. Developing hybrid feature sets based on 3D structures and physicochemical properties can capture subtle differences between competing enzyme-substrate enantiomeric complexes, improving model accuracy despite smaller datasets.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Sequence Similarity Network Construction

Purpose: To visualize and analyze relationships within an enzyme family to guide library design.

Procedure:

- Sequence Collection: Retrieve all sequences annotated with conserved functional motifs (e.g., facial triad for NHI enzymes) from public databases like UniProt.

- Network Generation: Input sequences into the EFI-EST web tool to generate a sequence similarity network.

- Threshold Optimization: Adjust alignment score thresholds to balance cluster resolution and connectivity. For initial overview, use lower stringency (e.g., 30-40); for functional correlation, increase stringency (e.g., 75).

- Cluster Analysis: Identify distinct clusters and singletons. Select representative sequences from diverse clusters to maximize functional diversity.

- Functional Annotation Overlay: Integrate available functional annotations to identify sequence-function correlations.

Applications: This protocol enabled researchers to select 314 α-KG-dependent NHI enzymes from 265,632 initial sequences, ensuring coverage of both characterized and unexplored sequence regions [2].

High-Throughput Biocatalytic Screening

Purpose: To experimentally profile enzyme-substrate compatibility across a diverse library.

Procedure:

- Library Expression: Express enzyme library in 96-well format using appropriate expression system (e.g., E. coli with pET-28b(+) vector).

- Lysate Preparation: Lyse cells and clarify lysates by centrifugation. Confirm expression via SDS-PAGE.

- Reaction Setup: In 96-well plates, combine clarified lysate (10-20 μL), substrate (0.1-1 mM in final reaction), α-ketoglutarate (1-5 mM), ferrous iron (0.1-0.5 mM), and buffer (typically 50-100 mM HEPES or phosphate, pH 7.0-8.0).

- Incubation: Shake plates at appropriate temperature (25-37°C) for 2-24 hours.

- Analysis: Quench reactions and analyze by UPLC-HRMS or GC-MS.

- Data Processing: Convert raw analytical data to binary (active/inactive) or quantitative (conversion, yield) metrics for model training.

Applications: This methodology facilitated the discovery of over 200 novel biocatalytic reactions in the α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzyme family, forming the BioCatSet1 dataset used to train CATNIP models [2] [11].

Future Directions and Emerging Opportunities

The integration of artificial intelligence with experimental automation represents the next frontier in sequence space navigation. AI is increasingly used throughout the experimental workflow, including hardware control, signal acquisition and processing, data analysis, and design-build-test-learn cycles [7]. These applications liberate scientists from repetitive manual tasks while optimizing experimental conditions.

Protein language models and generative AI approaches show particular promise for enzyme design. Foundation models like ProtT5, Ankh, and ESM2 can be fine-tuned on specific enzyme families to predict functional properties [7]. The emerging capability to generate novel enzyme sequences with desired functions using inverse folding methods and diffusion models may eventually enable de novo enzyme design, blurring the lines between discovering natural enzymes and creating entirely new biocatalysts [7].

Figure 2: Future integrated workflow combining machine learning with automated experimentation.

For pharmaceutical applications, biocatalysis is expanding to include complex molecules and novel modalities. Enzymatic oligonucleotide synthesis, modification of peptides or antibodies, and late-stage functionalization of drug candidates using unspecific peroxygenases represent emerging applications [10]. These advances, coupled with improved cofactor recycling systems and multi-enzyme cascade development, are steadily expanding the synthetic capabilities of biocatalysis in drug development.

Navigating vast sequence spaces requires integrated experimental and computational strategies that connect protein sequences to catalytic function. High-throughput experimentation generates the foundational data needed to train predictive models, while machine learning approaches enable extrapolation beyond empirically tested sequences and substrates. As these methodologies mature, they will progressively derisk biocatalytic implementation in pharmaceutical synthesis, enabling more efficient, sustainable, and selective routes to target molecules. The continued development of standardized protocols, data sharing practices, and automated workflows will accelerate this sequence-to-function paradigm, unlocking the functional potential hidden within unexplored regions of sequence space.

The exponential growth of genomic sequence data has created an immense reservoir of unexplored protein sequence-function information, with less than 0.3% of sequenced enzymes having experimentally characterized functions [2]. In this post-genomic era, Sequence Similarity Networks (SSNs) have emerged as a powerful computational framework for visualizing and interpreting complex evolutionary relationships within enzyme families, thereby addressing the fundamental challenge of connecting sequence space to functional attributes. SSNs provide an intuitive graph-based representation where nodes represent individual protein sequences and edges connect sequences that share significant sequence similarity, enabling researchers to map the functional landscape of enzyme superfamilies and make data-driven predictions about catalytic function. This technical guide examines the integral role of SSNs within the broader context of sequence-function relationships in biocatalysis research, detailing their construction, interpretation, and application for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to exploit enzymatic diversity for synthetic applications.

The prevailing sequence-structure-function paradigm has historically guided biocatalysis research, positing that similar sequences fold into similar structures that perform similar functions [1]. While this assumption holds true in many cases, modern research increasingly reveals instances where similar functions can be achieved by different sequences and structures, creating a more complex functional landscape than previously appreciated. SSNs have proven particularly valuable in navigating this complexity by revealing subfamily clustering patterns that often correlate with functional specialization, allowing researchers to make functional predictions based on sequence neighborhood relationships rather than relying solely on pairwise sequence identity metrics [2].

Theoretical Foundation: Connecting Sequence Space to Function

Statistical Frameworks for Functional Prediction

The statistical foundation of SSN analysis rests upon established relationships between sequence identity and functional conservation. Seminal research has demonstrated that the confidence threshold for transferring functional annotations between homologous enzymes depends critically on the level of sequence identity and the specificity of the functional descriptor being transferred.

Table 1: Enzyme Function Conservation at Different Sequence Identity Thresholds

| Sequence Identity Range | First Three EC Digits Conservation | All Four EC Digits Conservation | Functional Inference Confidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| >60% | >90% | >90% | High confidence for full annotation |

| 40-60% | >90% | <90% | High for reaction type, lower for substrate specificity |

| <40% | Declines rapidly | Declines rapidly | Caution required for any annotation |

As illustrated in Table 1, the first three digits of Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers, which describe the overall type of enzymatic reaction, remain highly conserved (>90%) down to approximately 40% sequence identity [13]. In contrast, the fourth EC digit, representing substrate specificity, requires >60% sequence identity for confident transfer. This statistical framework provides the theoretical basis for interpreting SSN edges—connections between sequences with identity above these thresholds suggest functional similarity, whereas connections below these thresholds may indicate functional divergence.

Beyond Pairwise Identity: The Role of Network Properties

SSN analysis extends beyond simple pairwise identity metrics by incorporating network topology as an additional predictive feature. The clustering coefficient, node centrality, and community structure within SSNs can reveal evolutionary patterns not apparent from sequence identity alone. Dense clusters often indicate functional conservation and recent divergence, while sparse connections between clusters may represent ancient divergence events or functional innovation. Recent studies have demonstrated that incorporating protein-protein interaction data with sequence similarity can increase the specificity of enzyme function prediction from 80% to 90% at 80% coverage compared to sequence similarity alone [14], highlighting the value of integrative network approaches.

Computational Methodologies for SSN Construction

Workflow for SSN Generation

The construction of biologically meaningful SSNs requires careful execution of sequential computational steps, each with specific methodological considerations that impact the final network topology and interpretability.

Diagram 1: SSN Construction Workflow

Sequence Retrieval and Alignment Strategies

The initial phase of SSN construction requires comprehensive sequence retrieval from publicly available databases such as UniProt, KEGG, and NCBI using tools like BLAST, PSI-BLAST, and EnzymeMiner [15] [2]. For enzyme families, this typically begins with a query sequence containing conserved catalytic residues or structural motifs. The retrieved sequences then undergo multiple sequence alignment using algorithms such as MAFFT, MUSCLE, or Clustal Omega [15], which must balance computational efficiency with alignment accuracy, particularly for divergent sequences. For large enzyme families exceeding 100,000 sequences, heuristic approaches such as representative sampling or pre-clustering may be necessary to manage computational complexity while preserving functional diversity.

Threshold Selection and Network Visualization

The most critical step in SSN construction is threshold selection—determining the alignment score or E-value cutoff that defines edges in the network. This threshold dictates the resolution of the SSN, with more stringent values (higher alignment scores) revealing finer subfamily divisions, while more permissive values reveal broader evolutionary relationships. As demonstrated in studies of the Old Yellow Enzyme family, systematically varying the alignment score threshold (e.g., from 10^-40 to 10^-100) can reveal hierarchical functional organization across >115,000 family members [16]. The resulting networks are typically visualized in Cytoscape or web-based platforms like EFI-EST, with nodes colored according to experimental annotations or phylogenetic provenance to facilitate functional inference.

Table 2: Bioinformatics Tools for SSN Construction and Analysis

| Tool Category | Representative Tools | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Database Search | BLAST, PSI-BLAST, EnzymeMiner, UniProt BLAST | Homology detection, sequence retrieval | Identifying homologous sequences from genomic databases |

| Multiple Sequence Alignment | MAFFT, MUSCLE, Clustal Omega, T-Coffee | Creating sequence alignments | Generating input for distance calculation |

| Phylogenetic Inference | FastTree, RAxML, PhyML, MrBayes | Evolutionary relationship inference | Complementary analysis to SSNs |

| Network Visualization & Analysis | Cytoscape, EFI-EST, ESI-EST | SSN visualization, clustering | Functional subfamily identification |

Practical Implementation: Case Studies in Biocatalysis

Exploring the Old Yellow Enzyme Family

A recent landmark study demonstrated the power of SSNs for functional landscape exploration within the Old Yellow Enzyme (OYE) family, which contains ene reductases valuable for asymmetric hydrogenation in pharmaceutical synthesis [16]. Researchers constructed SSNs for >115,000 OYE family members, using network topology to guide the selection of 118 diverse enzymes for experimental characterization. This systematic approach revealed several significant findings: (1) novel oxidative chemistry widespread among OYE members at ambient conditions; (2) 14 biocatalysts with enhanced activity or altered stereospecificity compared to previously characterized OYEs; and (3) a novel OYE subclass with unusual loop conformation confirmed through crystallography. This case study exemplifies how SSNs can guide targeted experimental characterization to efficiently expand the known functional diversity of enzyme families.

Mapping α-Ketoglutarate-Dependent Enzyme Reactivity

In a comprehensive effort to connect chemical and protein sequence space, researchers employed SSNs to navigate the functional diversity of α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes [2]. Beginning with 265,632 unique sequences containing the conserved facial triad of iron-coordinating residues, the team applied successive filtration steps—removing redundant orthologues (>90% similarity) and clusters associated with primary metabolism—to obtain a manageable yet diverse library of 314 enzymes (aKGLib1). The SSN representation revealed clear sequence-function relationships, with enzymes capable of modifying indolizidine scaffolds clustering together at appropriate alignment thresholds. This strategic sampling of sequence space enabled the discovery of over 200 previously unknown biocatalytic reactions through high-throughput experimentation, providing the training data for machine learning tools that predict compatible enzyme-substrate pairs.

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction via SSNs

SSNs provide critical phylogenetic context for Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction (ASR), an evolution-based protein engineering strategy that infers ancestral sequences to create highly stable enzymes [15]. By identifying appropriate extant sequences spanning the functional diversity of an enzyme family, SSNs enable the reconstruction of ancestral proteins that serve as excellent starting points for engineering campaigns. These ancestral enzymes typically exhibit enhanced thermostability and promiscuity compared to their modern counterparts, making them ideal scaffolds for further optimization. The combination of SSN analysis and ASR represents a powerful framework for enzyme engineering that requires screening of only small libraries (often <10 candidates) compared to the thousands to millions needed for directed evolution.

Experimental Protocols for SSN-Guided Enzyme Characterization

High-Throughput Biocatalytic Screening

Following SSN-guided enzyme selection, researchers must implement robust experimental protocols for functional characterization. For the α-KG-dependent enzyme study [2], the following methodology was employed:

Gene Synthesis and Cloning: DNA for selected library members was synthesized and cloned into a pET-28b(+) expression vector with standardizable tags and promoters to ensure consistent expression levels.

Parallel Protein Expression: E. coli cells were transformed with library plasmids and protein expression was carried out in 96-well deep-well plates with autoinduction media, cultivating at 37°C with shaking until OD600 reached 0.6-0.8, followed by temperature reduction to 18°C and continued incubation for 16-20 hours.

Cell Lysis and Normalization: Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, and one EDTA-free protease inhibitor tablet per 50 mL), and lysed by sonication. Lysates were clarified by centrifugation, and protein concentrations were normalized based on SDS-PAGE analysis.

High-Throughput Reaction Screening: Reactions were assembled in 96-well format with 50-100 µL final volume containing substrate (typically 1-2 mM), α-KG (5 mM), ammonium iron(II) sulfate (1 mM), and ascorbate (10 mM) in appropriate buffer. Reactions were initiated by addition of normalized lysate, incubated with shaking for 4-16 hours, and quenched with acetonitrile.

Product Analysis: Quenched reactions were analyzed by UPLC-MS with photodiode array and mass detection. Product formation was quantified against authentic standards when available, or semi-quantitatively estimated based on UV absorption and extracted ion chromatograms.

Functional Annotation and Validation

For enzymes exhibiting activity in initial screens, detailed functional characterization follows this protocol:

Enzyme Purification: His-tagged enzymes are purified using nickel-affinity chromatography followed by size-exclusion chromatography to obtain homogeneous protein for detailed kinetic analysis.

Steady-State Kinetics: Initial rates of product formation are measured under saturating cofactor conditions while varying substrate concentration. Kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) are determined by fitting data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression.

Substrate Scope Profiling: Purified enzymes are tested against structurally related substrate analogs to define the substrate acceptance range and identify key structural determinants of specificity.

Structural Characterization: Promising enzymes with novel functions are selected for structural determination via X-ray crystallography to elucidate structural features underlying catalytic properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SSN-Guided Enzyme Exploration

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in SSN Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Databases | UniProt, KEGG, NCBI nr | Source of homologous sequences for network construction |

| Cloning Systems | pET-28b(+) vector, T7 expression systems | Heterologous expression of target enzymes in E. coli |

| Expression Hosts | E. coli BL21(DE3), autoinduction media | High-yield protein production for functional screening |

| Chromatography Resins | Ni-NTA agarose, size-exclusion resins | Purification of tagged enzymes for biochemical characterization |

| Cofactor Substrates | α-Ketoglutarate, NADPH, SAM | Essential cosubstrates for enzyme functional assays |

| Analytical Standards | Authentic substrate/product standards | Quantification of enzymatic activity in screening assays |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Integration with Machine Learning Approaches

The combination of SSNs with machine learning algorithms represents the cutting edge of sequence-function prediction. As demonstrated by the CATNIP tool for α-KG-dependent enzymes [2], experimentally determined enzyme-substrate pairs from SSN-guided exploration can train predictive models that navigate between chemical space and protein sequence space. These models can suggest compatible enzyme sequences for a given substrate or rank potential substrates for a given enzyme sequence, effectively derisking biocatalytic reaction planning. Future developments will likely incorporate three-dimensional structural features and molecular dynamics simulations to improve prediction accuracy for highly divergent sequences.

Expanding to Underexplored Enzyme Families

The SSN framework continues to expand into previously underexplored enzyme families, with recent efforts focusing on classes with potential for biocatalytic applications in pharmaceutical synthesis and green chemistry. The discovery of widespread reverse, oxidative chemistry in the Old Yellow Enzyme family [16] highlights how SSN-guided exploration can reveal unexpected catalytic capabilities. As structural databases grow through initiatives like the World Community Grid and AlphaFold [1], integration of predicted structural features with SSN analysis will enable more accurate functional predictions for enzymes with minimal sequence similarity to characterized relatives.

Diagram 2: SSN-ML Integration Cycle

Sequence Similarity Networks have transformed our approach to exploring sequence-function relationships in biocatalysis, providing an intuitive yet powerful framework for navigating the vast landscape of enzymatic diversity. By integrating SSN analysis with high-throughput experimentation and machine learning, researchers can efficiently map functional relationships across enzyme families, identify novel biocatalysts, and predict compatible enzyme-substrate pairs for synthetic applications. As these methodologies continue to mature, SSN-guided exploration will play an increasingly central role in unlocking the full potential of enzymes for pharmaceutical synthesis, green chemistry, and fundamental biological discovery.

For decades, the central dogma of structural biology has followed a linear sequence-structure-function paradigm, wherein a protein's amino acid sequence determines its three-dimensional structure, which in turn dictates its biological function [1]. While this framework has been immensely valuable, it predominantly emphasizes the role of active site residues in direct substrate binding and catalysis. However, contemporary research reveals that this perspective is incomplete. A protein's functional properties are not merely the product of a handful of catalytic residues but emerge from a complex network of interactions throughout the entire protein structure. This network gives rise to epistasis—a phenomenon where the effect of a mutation depends on its genetic background [17]. In the context of biocatalysis, understanding epistasis is fundamental to unraveling sequence-function relationships and engineering enzymes with enhanced or novel activities.

Epistasis in proteins can be categorized into two primary types [17]. Specific epistasis (SE) arises from direct, physical interactions between residues, often those in close proximity within the protein structure. In contrast, global epistasis (GE) emerges from nonlinearities in the genotype-phenotype map, where a mutation's effect is modulated by the overall genetic background without requiring direct contact. Disentangling the contributions of these two phenomena is critical for accurately interpreting deep mutational scanning experiments and for the rational design of biocatalysts. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of global residue interactions and epistasis, framing them within a modern understanding of sequence-function relationships essential for advanced biocatalysis research and drug development.

Theoretical Framework: Defining Global Epistasis

Mathematical Formalism of Global Epistasis

Formally, under a model of global epistasis, each single mutation i has an independent effect λi on a latent additive trait, Λ. This latent trait may correspond to a biophysical property such as protein stability or the energy associated with folding or ligand binding [17]. The observed phenotype, Y (e.g., enzymatic activity, fluorescence, or fitness), is a potentially nonlinear, monotonic function g of Λ.

The relationship is described by the following equations [17]: Λ(x) = Λwt + ∑(i=1)^L λi xi Y(x) = g[Λ(x)]

Here, x ∈ {0,1}^L represents a binary protein sequence of length L, Λwt is the latent trait value for the wild-type sequence, and λi is the additive effect of mutation i. The nonlinear function g captures the global epistasis, transforming the additive latent trait into the observed phenotype. In practice, deviations from this model occur due to specific epistatic effects (λij) between mutation pairs *i* and *j* that directly influence the latent trait, and measurement error (ε) in the observed phenotype [17]:

Λ(x) = Λwt + ∑(i=1)^L λi xi + ∑(j

The central challenge is that the form of the nonlinearity g is generally unknown. Misspecification of g can lead to over- or underestimation of specific epistasis, distorting our understanding of the genotype-phenotype map [17].

Biological Origins of Global Epistasis

Global epistasis is not an abstract mathematical concept but arises from tangible biophysical and biochemical mechanisms. It can be attributed to several causes [17]:

- Thermodynamic Equilibrium: Many proteins exist in an equilibrium between conformational states. Mutations that subtly shift this equilibrium can have nonlinear effects on function, especially if the function is only performed efficiently in one state.

- Assay Detection Limits: Experimental assays often have upper and lower detection limits. Once a mutation (or combination of mutations) pushes the phenotype beyond these limits, further mutations may appear to have no effect, creating a nonlinearity.

- Widespread Specific Epistasis: In some scenarios, global epistasis can emerge as an aggregate effect of many weak, specific interactions distributed throughout the protein structure [17].

Methodological Approaches: Detecting and Quantifying Epistasis

A Rank-Based Framework for Disentangling Epistasis

A powerful semiparametric method for detecting specific epistasis in the presence of global epistasis and measurement noise leverages rank statistics [17]. This approach, known as Resample and Reorder (R&R), is grounded in a key observation: if the genotype-phenotype map is governed solely by global epistasis (with a monotonic function g), then the rank order of mutational effects should be preserved across different genetic backgrounds. Specific epistasis disrupts this preservation of rank order.

The following diagram illustrates the core logical workflow of the R&R method for distinguishing specific from global epistasis using rank-based statistics.

The R&R procedure involves the following key steps [17]:

- Data Input: Begin with a combinatorial deep mutational scanning (DMS) dataset, which assays the phenotypes of thousands to millions of protein variants.

- Rank Difference Calculation: For a given pair of mutations m and n in a specific genetic background i, calculate the difference in their phenotypic ranks, Δrank = rank(Yim) - rank(Y_in).

- Resampling: Account for heteroskedastic measurement noise by resampling the data. This step is crucial as measurement precision often varies across the phenotypic range in sequencing-based assays.

- Null Distribution: Generate a null distribution of Δ_rank under the assumption that no specific epistasis exists (i.e., only global epistasis is present).

- Hypothesis Testing: Compare the observed Δ_rank to the null distribution. A statistically significant deviation indicates the presence of specific epistasis between the mutation pair.

This method is "semiparametric" because it does not require specifying the exact form of the nonlinear function g, only that it is monotonic. It is invariant under monotonic transformations of the data and robust to heteroskedastic noise [17].

Computational Protein Design with Sparse Interaction Graphs

In de novo enzyme design and engineering, accounting for epistasis is a monumental challenge due to the combinatorial complexity of sequence space. Computational protein design often employs sparse residue interaction graphs to make this problem tractable [18].

In this approach, a protein design problem is represented as a graph where nodes are residues and edges represent interactions between them. To reduce computational cost, edges between distant residues (deemed to have negligible interaction energy) are omitted, creating a sparse graph. The lowest-energy sequence identified using this sparse graph is the sparse Global Minimum Energy Conformation (GMEC). However, neglecting these long-range interactions can alter the predicted optimal sequence and conformation, potentially leading to designs that lack the desired function when synthesized and tested [18].

A critical analysis has shown that the differences between the sparse GMEC and the full GMEC (found by considering all pairwise interactions) depend on whether the design involves core, boundary, or surface residues [18]. To reap the benefits of sparse graphs without sacrificing accuracy, provable, ensemble-based algorithms (e.g., based on A* search or dead-end elimination) can be used. These algorithms can efficiently compute both the full and sparse GMEC, often by enumerating a small number of conformations (fewer than 1,000), providing a safeguard against the inaccuracies introduced by oversimplification [18].

Large-Scale Structure-Function Analysis

The dramatic increase in available protein structures, fueled by advances in AI-based prediction like AlphaFold2 and large-scale citizen science projects, enables a new mode of analysis [1]. By predicting structures for hundreds of thousands of microbial protein sequences and annotating them with residue-specific functions using tools like DeepFRI, researchers can map the protein structure-function universe at an unprecedented scale [1].

This approach moves beyond the assumption that similar sequences always yield similar structures and functions. It allows for the exploration of regions in the protein universe where similar functions are achieved by different sequences and structures. Analyzing this data reveals that the structural space is continuous and largely saturated, highlighting the need to shift from a sequence-based to a sequence-structure-function-based analysis paradigm for biocatalysis and drug development [1].

Table 1: Key Experimental and Computational Methods for Analyzing Epistasis

| Method Name | Type | Primary Function | Key Advantage(s) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resample & Reorder (R&R) | Statistical | Detect specific epistasis from DMS data | Agnostic to form of global epistasis; robust to noise | [17] |

| Sparse A*/OSPREY | Algorithmic | Find GMEC in protein design | Provable accuracy; can compute full & sparse GMEC | [18] |

| DeepFRI | Deep Learning | Predict function from structure | Provides residue-specific annotations | [1] |

| Local Descriptor Analysis | Structural | Map local substructures to function | Generates legible rules; discriminates function in versatile folds | [19] |

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Protocol: Deep Mutational Scanning for Epistasis Analysis

This protocol outlines the key steps for conducting a DMS experiment to probe epistasis in a biocatalyst.

I. Library Design and Construction

- Define the Sequence Space: Select a protein gene of interest and identify a set of L target positions for mutagenesis (e.g., active site residues, a distal subunit interface, or a full gene scan).

- Generate Variant Library: Use degenerate oligonucleotides or other synthetic DNA methods (e.g., CRISPR-based editing) to create a comprehensive library of gene variants. For pairwise epistasis studies, this often involves creating all single mutants and many double mutants at the target positions.

- Clone Library: Clone the variant library into an appropriate expression vector compatible with the downstream phenotypic screen or selection.

II. Phenotypic Selection or Screening

- Assay Design: Establish a high-throughput assay that links the protein's function (e.g., catalytic activity for a survival nutrient, antibiotic resistance, fluorescence) to cellular growth or sortability.

- Apply Selection Pressure: Transfer the library of expression clones into a suitable host (e.g., yeast, bacteria) and subject the population to the defined selective pressure. For example, if the enzyme produces a necessary metabolite, grow the cells in media lacking that metabolite.

- Collect Samples: Isolate genomic DNA from the population before selection (initial time point, Ti) and after selection (final time point, Tf).

III. Sequencing and Data Processing

- Amplify and Sequence: Amplify the variant genes from the Ti and Tf populations by PCR and subject them to high-throughput sequencing (e.g., Illumina).

- Count Reads: Map sequencing reads back to the reference gene and count the number of reads for each variant in the Ti and Tf libraries.

- Calculate Enrichment: For each variant x, compute a fitness score or enrichment score. A common method is to calculate the log-ratio of the normalized frequency: Fitness Y^(x) ≈ log( (CountTf(x) / NTf) / (CountTi(x) / NTi) ) where N is the total number of reads in the respective sample.

IV. Data Analysis for Epistasis

- Fit a Phenotypic Model: Model the fitness data. A simple starting point is a linear model:

Y = β_0 + ∑β_i x_i + ∑β_ij x_i x_j. The coefficients β_ij represent the interaction (epistatic) terms. - Account for Global Epistasis: Apply methods like the R&R test [17] to the fitness data to distinguish specific epistasis from the spurious signals generated by an underlying nonlinear genotype-phenotype map.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Epistasis Studies

| Item/Tool | Function/Description | Application in Epistasis Research |

|---|---|---|

| Degenerate Oligonucleotides | Primers containing randomized codons (e.g., NNK) for mutagenesis. | Construction of comprehensive variant libraries for DMS. |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | High-throughput method to sort cells based on optical properties. | Isolating enzyme variants with different activity levels based on a fluorescent reporter. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) | Platforms (e.g., Illumina) for massively parallel DNA sequencing. | Quantifying the abundance of each variant in a library before and after selection. |

| AlphaFold2/AlphaFold3 | Deep learning systems for highly accurate protein structure prediction. | Generating structural models for novel enzyme variants to interpret epistasis structurally. |

| Rosetta & DMPfold | Software suites for de novo and homology-based protein structure prediction. | Predicting structures for proteins with no close homologs; used in large-scale analyses [1]. |

| DeepFRI | Graph neural network for predicting protein function from structure. | Annotating residue-level functions in predicted structural models to infer functional constraints [1]. |

Implications for Biocatalysis and Enzyme Engineering

The integration of global epistasis into the sequence-function paradigm has profound implications for biocatalyst design. Recognizing that functional properties are distributed across the protein architecture allows researchers to move beyond the confines of the active site and consider allosteric networks and dynamic residues as potential engineering targets. This is particularly relevant for designing enzymes to operate in non-natural environments, such as in organic solvents or at elevated temperatures, where the wild-type global network may be suboptimal.

The prevalence of enzyme promiscuity—where enzymes catalyze secondary reactions beside their native one—is a key feature of enzyme superfamilies and is maintained by these global interaction networks [20]. This promiscuity provides the raw material for the evolution of new functions. By mapping epistatic interactions, researchers can better understand the "function connectivity" within superfamilies and identify evolutionary trajectories that are accessible through directed evolution [20].

Furthermore, the rise of intelligent manufacturing and enzymatic total synthesis in biocatalysis relies on the ability to design multi-step enzymatic cascades [21]. The stability and efficiency of each enzyme in the cascade are critical. Understanding and predicting the epistatic effects of mutations intended to improve one property (e.g., solvent tolerance) without disrupting another (e.g., substrate specificity) is essential for avoiding costly and time-consuming trial-and-error optimization. Machine learning (ML) models, trained on DMS and structural data that capture these epistatic relationships, are becoming indispensable tools for navigating the fitness landscape and identifying high-performing biocatalysts [21].

Table 3: Quantitative Analysis of Epistasis from Selected Studies

| Protein/System | Experimental Scale | Key Finding on Epistasis | Impact on Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combinatorial DMS (Example) | ~10^4 - 10^6 variants | Global epistasis can obscure specific interactions; rank-based methods recover known protein contacts. | Critical for accurate interpretation of high-throughput mutagenesis data. | [17] |

| Computational Design (136 problems) | 136 design problems | Sparse interaction graphs (cutoffs) changed the GMEC sequence in 30-50% of cases, varying by residue location (core, surface). | Neglecting long-range interactions can lead to designs with incorrect sequence/stability. | [18] |

| Microbial Protein Universe | ~200,000 structures | The structural space is continuous and saturated; similar functions can be achieved by different sequences/structures. | Highlights need for structure-function analysis beyond simple sequence homology. | [1] |

| Designed Kemp Eliminase | 59 initial designs | 8/59 designed proteins showed activity; subsequent directed evolution improved kcat/Km by 200-fold. | Demonstrates that initial computational designs provide a starting point shaped by epistasis, which evolution optimizes. | [22] |

The study of protein function has decisively moved beyond the examination of isolated active sites. The interplay of global residue interactions, manifesting as specific and global epistasis, is a fundamental determinant of catalytic efficiency, stability, and evolvability. For researchers in biocatalysis and drug development, integrating this complex reality into experimental and computational workflows is no longer optional but necessary for success. The methodologies outlined here—from rank-based statistical tests and provable protein design algorithms to large-scale structure-function mapping—provide a toolkit for navigating this complexity. By embracing a holistic view of the protein that accounts for its intricate internal interaction network, we can accelerate the design of novel biocatalysts for sustainable chemistry and the development of new therapeutics.

The fundamental challenge in leveraging biocatalysis for synthetic applications lies in predicting which enzyme will catalyze a reaction for a given substrate. This connection between protein sequence space and chemical space has remained a significant roadblock, impeding the widespread adoption of enzymatic transformations in fields ranging from drug development to manufacturing [2]. The underexploration of connections between chemical and protein sequence space constrains navigation between these two landscapes. While millions of protein sequences are known, less than 0.3% have experimentally characterized functions, creating a vast gap between sequence information and practical application [2] [8]. This guide examines cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies that are bridging this divide, with a particular focus on machine learning approaches that leverage sequence-function relationships to predict enzyme-substrate compatibility with unprecedented accuracy.

Computational Approaches for Specificity Prediction

Machine Learning Architectures

Recent advances in machine learning have produced sophisticated models capable of predicting enzyme-substrate interactions by learning from structural and sequence data:

EZSpecificity: This cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture analyzes enzyme sequences and structures to predict substrate compatibility. Trained on a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels, it demonstrates remarkable accuracy, achieving 91.7% in identifying single potential reactive substrates compared to 58.3% for previous state-of-the-art models [23] [24]. The model specializes in analyzing the enzyme active site and complicated transition state of the reaction, which are fundamental to understanding specificity [23].

CATNIP: Designed specifically for α-ketoglutarate (α-KG)/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes, this tool predicts compatible enzymes for a given substrate or ranks potential substrates for a given enzyme sequence. The development of this model was enabled by high-throughput experimentation to populate connections between productive substrate and enzyme pairs [2].

Contrastive Learning Models: Tools like CLEAN (Contrastive Learning enabled Enzyme ANnotation) predict enzyme commission numbers from sequences, providing insights into potential reaction types without specifically identifying native substrates [2] [24].

Data Requirements and Training

The performance of these models depends critically on the quality and scope of their training data. EZSpecificity utilized both existing enzymatic data and extensive docking studies for different classes of enzymes to create a large database containing information about enzyme sequences, structures, and conformational changes around substrates [24]. These docking simulations, performed for various enzyme classes, provided millions of data points on atomic-level interactions between enzymes and their substrates, offering the missing structural context needed to build highly accurate predictors [24].

Performance Comparison of Predictive Models

Table 1: Comparative performance of enzyme-substrate prediction tools

| Model Name | Architecture | Enzyme Classes Covered | Key Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network | Multiple classes, validated on halogenases | 91.7% accuracy on halogenase validation set |

| CATNIP | Specialized model for α-KG/Fe(II) enzymes | α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron enzymes | High-throughput experimental validation |

| ESP (Previous SOTA) | Not specified | Multiple classes | 58.3% accuracy on same halogenase validation set |

Experimental Methodologies for Validation

High-Throughput Experimental Profiling

Robust experimental validation is crucial for confirming computational predictions and generating training data. A representative protocol for profiling α-KG-dependent non-heme iron (NHI) enzymes exemplifies this approach [2]:

Library Design and Sequence Selection:

- Utilize the Enzyme Function Initiative–Enzyme Similarity Tool (EFI-EST) to identify all sequences containing the facial triad of iron-coordinating residues conserved for hydroxylases [2].

- Apply sequence similarity network (SSN) analysis to 265,632 unique sequences, reducing to 27,005 sequences by removing redundant orthologues (>90% similarity) and clusters containing primary metabolism enzymes [2].

- Select 314 enzymes for the library (aKGLib1) through strategic sampling: 102 sequences from the most populated cluster, 125 uncharacterized sequences from poorly annotated clusters, and 87 additional sequences with known or proposed function [2].

Protein Expression and Purification:

- Synthesize DNA for the library and clone into pET-28b(+) expression vectors [2].

- Transform E. coli cells with plasmids encoding each library member [2].

- Conduct overexpression in 96-well plate format [2].

- Verify expression using SDS-PAGE analysis of crude cell lysate (successful for 78% of enzymes) [2].

Activity Screening:

- Incubate each enzyme with a diverse panel of substrate candidates [2].

- For oxidative enzymes, include necessary cofactors (e.g., α-ketoglutarate, Fe(II), ascorbate, catalase) [2].

- Analyze reactions using appropriate detection methods (LC-MS, GC-MS, or fluorescence assays) [2].

- Confirm product structures through comparison with authentic standards when available [2].

Sequence-Function Relationship Mapping

Systematic experimental profiling has revealed that enzymes with similar sequences often display related substrate preferences. Visualization tools are essential for interpreting these relationships:

Sequence Similarity Networks (SSNs): Visual tools that group protein sequences based on similarity thresholds, effectively clustering sequences with related functions [8]. For flavin-dependent halogenases, SSNs revealed clustering based on native substrates, with separate groupings for enzymes that halogenate phenols versus those modifying tryptophan substrates [8].

Phylogenetic Trees: Illustrate evolutionary relationships between sequences, distinguishing close relatives from distant ones, though large-scale alignments can be challenging [8].

Multiple Sequence Alignment: Identifies conserved motifs that potentially predict enzyme function or highlight residues important for catalysis [8].

Diagram 1: Sequence to function prediction workflow.

Integrating Computational and Experimental Approaches

The most successful strategies for connecting chemical and protein landscapes combine computational prediction with experimental validation in an iterative cycle. The development of EZSpecificity exemplifies this approach, where machine learning predictions were experimentally validated using eight halogenases and 78 substrates [23] [24]. This validation confirmed the model's superior performance (91.7% accuracy) compared to existing tools [24].

Similarly, the creation of CATNIP for α-KG/Fe(II)-dependent enzymes involved a two-phase approach: high-throughput experimentation to establish substrate-enzyme connections, followed by model development [2]. This strategy derisks the investigation and application of biocatalytic methods by providing validated starting points for synthetic applications.

Table 2: Essential research reagents for enzyme-substrate profiling

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiments |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | pET-28b(+) vector, E. coli expression strains | Heterologous protein production for enzyme library generation |

| Cofactors | α-Ketoglutarate, Fe(II), FAD, NADPH | Essential cosubstrates and cofactors for enzymatic reactions |

| Analytical Tools | LC-MS, GC-MS, fluorometric assays | Detection and quantification of reaction products |

| Bioinformatics Tools | EFI-EST, CLEAN, sequence similarity networks | Sequence analysis, family classification, and function prediction |

| Model Organisms | Palmer Station penguins dataset | Source of biological measurements for comparative analysis |

Applications in Drug Development and Synthetic Biology

Accurate prediction of enzyme-substrate compatibility has transformative potential in pharmaceutical development and synthetic biology. The integration of these approaches enables:

Streamlined Synthetic Routes: Biocatalytic steps have decreased step counts by 33% and more than doubled overall yields in pharmaceutical agent production compared to highest-performing chemical syntheses [2].

Late-Stage Functionalization: Enzymatic catalysis enables selective functionalization of complex intermediates, particularly valuable in discovery chemistry where traditional methods lack selectivity [2].

Enzyme Engineering: Predictive models guide protein engineering campaigns by identifying key residues for modification. For example, engineering a transaminase for sacubitril synthesis involved 26 amino acid substitutions to achieve a 500,000-fold improvement in activity [2].

Diagram 2: Computational prediction to application pipeline.

Future Directions

The field of enzyme-substrate compatibility prediction continues to evolve with several promising research directions:

Expanding Model Scope: Current models like EZSpecificity are being refined with more experimental data and extended to cover additional enzyme classes beyond the initially validated halogenases [24].

Selectivity Prediction: Next-generation tools aim to predict not just whether an enzyme will accept a substrate, but also its regioselectivity and stereoselectivity, helping rule out enzymes with off-target effects [24].

Integration with Retrobiosynthesis: Machine learning-enabled retrobiosynthesis combines pathway prediction with enzyme compatibility assessment to design novel synthetic routes to target molecules [23].

As these computational tools mature and integrate with high-throughput experimental methods, they will progressively illuminate the vast unexplored territory of enzyme sequence space, ultimately making biocatalysis a predictable, derisked strategy for molecular synthesis.

The Modern Biocatalyst Toolkit: AI, Design, and Engineering Strategies

Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models for Function Prediction and Annotation

The paradigm of predicting protein function from sequence represents one of the most significant challenges and opportunities in modern biocatalysis research. The ability to accurately annotate enzyme function computationally would dramatically accelerate the discovery and engineering of biocatalysts for synthetic chemistry, pharmaceutical development, and sustainable manufacturing. Despite the staggering growth of genomic sequencing data—with available protein sequences increasing by approximately 20-fold from 2018 to 2023—the percentage of enzymes with experimentally characterized function remains extremely low, with less than 0.3% of sequenced enzymes having computationally annotated function [2]. This annotation gap severely constrains our ability to tap into the vast catalytic potential encoded in natural biodiversity.

Machine learning and deep learning approaches are increasingly bridging this sequence-function chasm by learning complex patterns from biological data that escape traditional bioinformatics methods. These computational techniques can be broadly categorized into sequence-based models that learn from amino acid sequences directly, and structure-based models that incorporate structural information, often predicted by tools like AlphaFold [25]. The application of these models spans functional annotation, substrate specificity prediction, and guided protein engineering, offering the potential to navigate the complex fitness landscape of protein sequences more effectively than ever before.

Within biocatalysis research, these computational methods are transforming strategy. Rather than relying solely on known reactions and local exploration in chemical space, researchers can now use ML tools to predict compatible enzyme-substrate pairs across diverse protein families [2]. This capability is particularly valuable for planning biocatalytic steps in synthetic routes, which traditionally carries substantial risk if the reaction on a specific substrate is not previously documented. As Buller notes, ML enables researchers to "explore large datasets and analyze the sequence-function relationship of screened enzyme variants," fundamentally changing how we navigate protein fitness landscapes [25].

Machine Learning Approaches for Enzyme Function Prediction

Contrastive Learning for Functional Annotation

Contrastive learning has emerged as a powerful approach for enzyme functional annotation, particularly when dealing with limited labeled data. The CLEAN (Contrastive Learning–Enabled Enzyme Annotation) model represents a significant advancement in this category, using contrastive learning to predict Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers for uncharacterized enzymes [2]. This method learns a semantic space where enzymes with similar functions are positioned closer together, allowing for transfer of functional annotations based on sequence similarity in this learned representation.

Unlike traditional homology-based methods that rely on sequence alignment, contrastive learning models can detect functional similarities even between distantly related enzymes by learning higher-order patterns in sequence data. This capability is particularly valuable for annotating the rapidly expanding universe of protein sequences where traditional methods may fail to identify functional relationships. However, as observed in the characterization of α-ketoglutarate-dependent non-heme iron enzymes, approximately 80% of CLEAN annotations were made with low confidence, highlighting the ongoing challenge of accurate functional prediction for novel enzyme families [2].

Graph Neural Networks for Multi-omics Integration