Directed Evolution vs. Rational Design: A Strategic Guide for Protein Engineering in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of directed evolution and rational design, the two dominant strategies in protein engineering.

Directed Evolution vs. Rational Design: A Strategic Guide for Protein Engineering in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of directed evolution and rational design, the two dominant strategies in protein engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, methodological workflows, and practical applications of each approach. By examining their respective advantages, limitations, and troubleshooting strategies, this guide offers a framework for selecting and integrating these methods. Furthermore, it highlights how emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and machine learning are converging these strategies to accelerate the development of novel biologics, enzymes, and gene therapies, ultimately shaping the future of biomedical research and therapeutic discovery.

Core Principles: Understanding the Philosophies of Rational Design and Directed Evolution

In the quest to tailor proteins for applications ranging from therapeutic drug development to industrial biocatalysis, two dominant engineering philosophies have emerged: rational design and directed evolution. Rational design operates as a precise architectural process, where scientists use detailed knowledge of protein structure and function to make specific, planned changes to an amino acid sequence [1]. In contrast, directed evolution mimics natural selection in laboratory settings, creating diverse libraries of protein variants through random mutagenesis and selecting those with desirable traits over iterative rounds [2] [3]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these methodologies, examining their strategic advantages, practical limitations, and optimal applications within research and development workflows. By synthesizing current experimental data and protocols, we aim to equip scientists with the evidence necessary to select the appropriate engineering strategy for their specific protein optimization challenges.

Core Principles and Methodologies

The Rational Design Workflow

Rational design requires a foundational understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships. This approach functions like architectural engineering, leveraging computational models and structural biology data to predict how specific mutations will alter protein performance. The typical workflow involves:

- Structural Analysis: Researchers first obtain high-resolution structural data through X-ray crystallography, NMR, or cryo-EM, identifying key residues involved in catalytic activity, substrate binding, or protein stability.

- Computational Modeling: Using molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulations, and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) calculations, engineers simulate the effects of targeted amino acid substitutions [4].

- Focused Library Construction: Unlike the vast libraries of directed evolution, rational design typically creates small, focused libraries by performing site-saturation mutagenesis at specific, predetermined positions [4].

- Functional Validation: The limited number of designed variants undergoes functional screening to confirm predicted improvements in stability, activity, or specificity.

The profound advantage of rational design lies in its precision and efficiency when sufficient structural and mechanistic knowledge exists. It enables direct testing of hypotheses about protein function and can achieve significant functional improvements with minimal screening effort [4].

The Directed Evolution Workflow

Directed evolution harnesses Darwinian principles of mutation and selection, compressing evolutionary timescales into laboratory-accessible timeframes. This approach received formal recognition with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Frances H. Arnold for establishing it as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology [2]. The iterative cycle consists of two fundamental steps:

- Genetic Diversification: Creating library diversity through random mutagenesis (e.g., error-prone PCR) or recombination-based methods (e.g., DNA shuffling) [2] [3].

- Phenotype Selection: Identifying improved variants through high-throughput screening or selection systems that link desired function to host survival or detectable signals [2].

The strategic advantage of directed evolution is its ability to discover non-intuitive solutions and improve protein functions without requiring detailed structural knowledge or complete understanding of catalytic mechanisms [2].

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison

| Aspect | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Requirement | High (structure, mechanism) | Low to moderate |

| Library Size | Small, focused (10-10,000 variants) | Very large (10^4-10^12 variants) |

| Mutation Strategy | Targeted, specific residues | Random, genome-wide |

| Computational Demand | High (modeling, simulation) | Lower (focus on screening) |

| Theoretical Basis | First-principles, physical chemistry | Empirical, evolutionary principles |

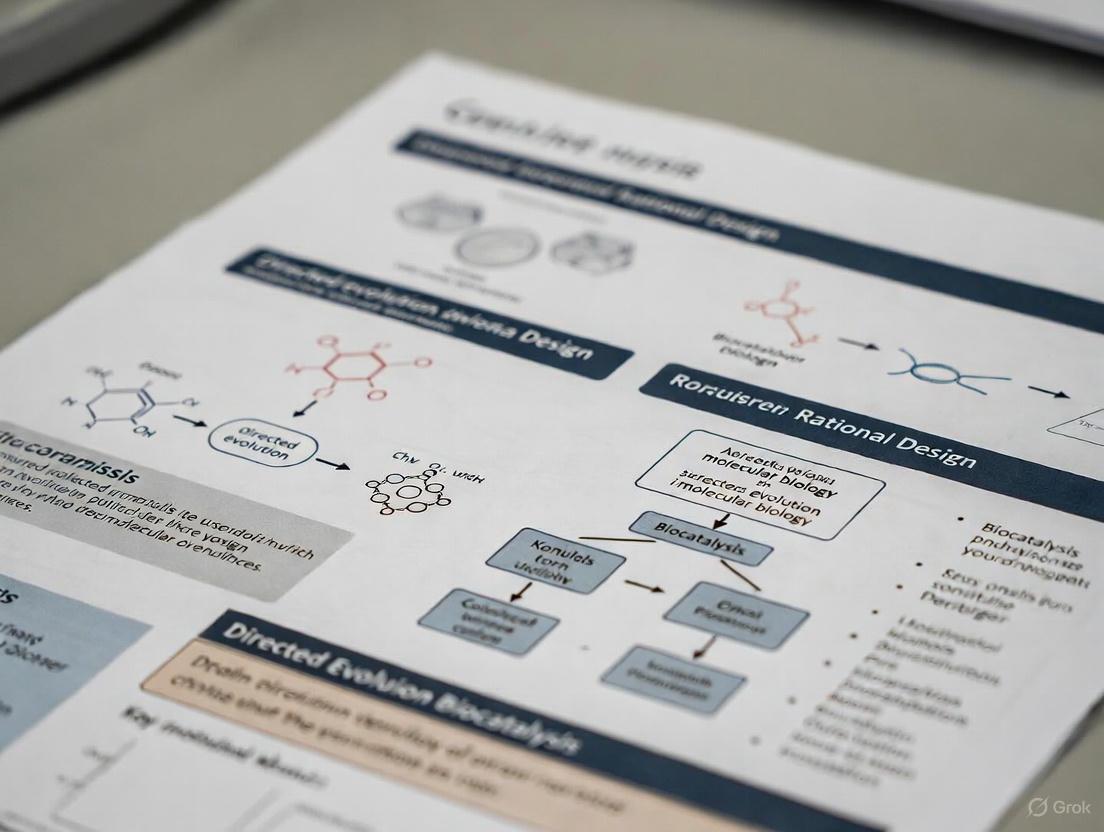

Figure 1: Comparative workflows of Rational Design (blue) and Directed Evolution (red). Rational design follows a linear, knowledge-driven path, while directed evolution employs an iterative, empirical cycle of diversification and selection.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Quantitative Success Metrics

Direct comparison of rational design and directed evolution reveals distinct performance profiles across various engineering objectives. The following table synthesizes experimental data from multiple protein engineering studies:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison

| Engineering Objective | Rational Design Success | Directed Evolution Success | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostability Enhancement | ~5-15°C increase [4] | ~10-25°C increase [2] | Directed evolution often achieves greater stability gains through accumulation of multiple stabilizing mutations |

| Substrate Specificity | 10-600-fold change [4] | 100-10,000-fold change [2] | Directed evolution more effective for dramatic specificity switches |

| Enantioselectivity | Moderate improvements (20-fold) [4] | Significant improvements (up to 400-fold) [3] | Non-intuitive mutations from directed evolution often crucial for stereoselectivity |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | 2-32-fold improvement [4] | 10-10,000-fold improvement [2] [3] | Directed evolution better at optimizing complex catalytic parameters |

| Non-Natural Function | Limited success with de novo design [4] | Successful creation of novel activities [5] | Directed evolution excels at importing non-biological functions |

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Engineering Haloalkane Dehalogenase (DhaA) Activity

A semi-rational approach combining both methodologies demonstrated how hybrid strategies can overcome limitations of either approach alone. Researchers first used random mutagenesis and DNA shuffling to identify beneficial mutations, then employed molecular dynamics simulations to discover that these mutations improved product release through access tunnels rather than directly affecting the active site [4].

Experimental Protocol:

- Initial Directed Evolution: Error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling generated initial improved variants

- Computational Analysis: Molecular dynamics simulations identified tunnel residues affecting product release

- Focused Library Construction: Site-saturation mutagenesis at five key tunnel residues

- Screening: ~2500 variants screened for enhanced dehalogenase activity

- Result: 32-fold improved activity through restricted water access to active site [4]

Case Study 2: Optimizing Cyclopropanation in Protoglobin

A recent study demonstrated machine learning-assisted directed evolution to optimize five epistatic residues in the active site of a protoglobin for non-native cyclopropanation activity [5]. This approach addressed a key limitation of traditional directed evolution: epistatic interactions that make mutation effects non-additive.

Experimental Protocol:

- Design Space Definition: Five active-site residues (W56, Y57, L59, Q60, F89) identified

- Initial Library: Variants generated through PCR-based mutagenesis with NNK degenerate codons

- Active Learning Loop:

- Batch screening of variants for cyclopropanation yield and selectivity

- Machine learning model training on sequence-fitness data

- Bayesian optimization to select next variant batch

- Result: After three rounds (~0.01% of design space explored), yield improved from 12% to 93% with high diastereoselectivity [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Successful protein engineering requires specialized reagents and methodologies tailored to each approach. The following toolkit details essential resources for implementing rational design and directed evolution campaigns:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Engineering

| Reagent/Method | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kits | Comprehensive exploration of all 20 amino acids at targeted positions | Rational design, semi-rational approaches |

| Error-Prone PCR Kits | Introduction of random mutations across entire gene | Directed evolution library generation |

| DNA Shuffling Reagents | Recombination of beneficial mutations from multiple parents | Directed evolution diversity generation |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulation of protein dynamics and mutation effects | Rational design prediction and validation |

| 3DM/HotSpot Wizard | Evolutionary analysis for identifying mutable positions | Semi-rational library design |

| Microtiter Plate Screening | Medium-throughput functional assessment | Both approaches (lower-throughput for rational) |

| FACS-based Screening | Ultra-high-throughput cell sorting | Directed evolution (10^7-10^9 variants) |

| Phage/Yeast Display | In vitro selection for binding interactions | Directed evolution of molecular recognition |

| CETSA Assays | Target engagement validation in physiological conditions | Confirmatory testing for both approaches |

Integrated and Emerging Approaches

The Rise of Semi-Rational Design

The historical dichotomy between rational design and directed evolution is increasingly bridged by semi-rational approaches that leverage the strengths of both philosophies. These methods utilize evolutionary information, structural insights, and computational predictive algorithms to create small, high-quality libraries focused on promising regions of sequence space [4]. By preselecting target sites and limiting amino acid diversity based on bioinformatic analysis, semi-rational design achieves higher functional content in smaller libraries, reducing screening burdens while maintaining exploration efficacy.

Key semi-rational methodologies include:

- Sequence-Based Design: Using multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis to identify evolutionarily allowed substitutions at functional hotspots [4]

- Structure-Guided Design: Targeting residues in specific structural contexts like active site access tunnels or allosteric networks [4]

- Computational Library Design: Employing machine learning algorithms and molecular simulations to predict functionally rich sequence space [6]

Machine Learning Revolution

Machine learning has emerged as a transformative technology that enhances both rational and evolutionary approaches. Recent advances demonstrate that machine learning-assisted directed evolution (MLDE) can dramatically improve the efficiency of navigating complex fitness landscapes, particularly those characterized by epistatic interactions [6] [5].

Table 4: Machine Learning Applications in Protein Engineering

| ML Approach | Mechanism | Advantages | Demonstrated Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLDE | Supervised learning on sequence-fitness data to predict high-fitness variants | Broader sequence space exploration in single round | Outperforms DE on 16/16 combinatorial landscapes [6] |

| Active Learning-assisted DE | Iterative model retraining with uncertainty quantification to guide exploration | Efficient navigation of epistatic landscapes | 8-fold yield improvement in challenging cyclopropanation [5] |

| Zero-Shot Predictors | Fitness prediction using evolutionary data or physical principles without experimental training | Guides initial library design | Enriches functional variants in training sets [6] |

| Language Models | Protein sequence representation learning from evolutionary-scale databases | Captures complex sequence-function relationships | Improves prediction accuracy for fitness landscapes [5] |

Strategic Implementation Guidelines

Approach Selection Framework

Choosing between rational design and directed evolution requires careful consideration of project constraints and knowledge context. The following guidelines support strategic decision-making:

Apply Rational Design When:

- High-resolution structural data is available for target protein

- Specific molecular interactions need precise manipulation

- The engineering goal involves well-understood mechanistic changes

- Resources for high-throughput screening are limited

- Computational expertise and infrastructure are accessible

Prefer Directed Evolution When:

- Structural information is limited or unreliable

- The objective involves complex or multiple protein traits

- Non-intuitive solutions may be required for functional optimization

- High-throughput screening capabilities are established

- Epistatic interactions are suspected to be important

Adopt Semi-Rational or ML-Assisted Approaches When:

- Some structural or evolutionary information is available

- The target protein exhibits significant epistasis

- Combining the exploration power of evolution with design efficiency

- Access to computational resources and experimental automation exists

The most successful modern protein engineering campaigns often employ an integrated strategy, beginning with computational analysis to identify promising regions of sequence space, creating focused libraries based on these insights, and using directed evolution to refine and optimize initial designs [4] [6] [5]. This synergistic approach leverages the architectural precision of rational design with the exploratory power of directed evolution, maximizing the probability of discovering highly optimized protein variants for therapeutic, industrial, and research applications.

In the realm of biotechnology, directed evolution stands as a powerful method for optimizing proteins and enzymes, deliberately mimicking the principles of natural selection in a laboratory setting to achieve desired functions [7]. This approach represents a form of meta-engineering, where scientists design the evolutionary process itself rather than the final product directly [8]. Unlike rational design, which requires extensive prior knowledge of protein structure and function, directed evolution operates through iterative cycles of diversification and selection, allowing beneficial mutations to accumulate without necessarily predicting them in advance [1]. This article provides a comparative guide between directed evolution and rational design, examining their core methodologies, experimental protocols, and applications, with a particular focus on the data and workflows relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Core Principles and Methodological Comparison

The Conceptual Framework of Directed Evolution

Directed evolution is fundamentally an iterative bio-engineering process. It begins with a gene of interest and subjects it to random mutagenesis, creating a vast library of genetic variants [7] [9]. This library is then expressed, and the resulting protein variants are screened for an enhanced or novel function. The best-performing variants are selected, and their genes serve as the template for the next round of mutation and selection, effectively climbing the fitness landscape in a stepwise manner [5]. The success of this method hinges on the quality and size of the mutant library and the efficiency of the high-throughput screening or selection process used to identify improvements [7] [10].

Contrasting Rational Design and Directed Evolution

The choice between directed evolution and rational design is often dictated by the depth of available protein knowledge and the complexity of the desired functional change. The table below summarizes the core distinctions.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Directed Evolution and Rational Design

| Feature | Directed Evolution | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Mimics natural evolution; random mutagenesis coupled with selection [1] | Requires detailed structural/functional knowledge for targeted changes [7] |

| Knowledge Dependency | Does not require prior structural knowledge [9] | Relies on extensive structural, functional, and mechanistic data [7] |

| Methodological Approach | Library creation (e.g., error-prone PCR), high-throughput screening [7] | Site-directed mutagenesis based on computational models [7] |

| Handling of Epistasis | Can navigate complex, epistatic fitness landscapes through experimentation [5] | Challenging to predict epistatic effects accurately [7] |

| Exploratory Power | High throughput; explores sequence space broadly but can be resource-intensive [1] [8] | Lower throughput; highly focused exploration based on prior knowledge [8] |

| Best Use Cases | Optimizing complex traits, exploring new functions, when structural data is lacking [1] [9] | Making specific, precise alterations (e.g., catalytic residue swaps) [7] |

Hybrid and Advanced Approaches

To leverage the strengths of both methods, researchers often adopt hybrid strategies. Semi-rational design combines elements of both by using computational or bioinformatic analysis to identify promising regions of a protein to mutate, then creating focused, high-quality libraries for screening [7] [10]. This approach reduces library size and screening effort while increasing the likelihood of success.

Furthermore, the field is rapidly advancing with the integration of machine learning (ML). ML models can analyze high-throughput screening data to predict sequence-function relationships, guiding library design and identifying beneficial mutations more efficiently. A notable example is Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE), which uses iterative machine learning and uncertainty quantification to optimize proteins more efficiently, especially in rugged fitness landscapes with significant epistasis [5].

Experimental Protocols and Data

A Standard Directed Evolution Workflow

A typical directed evolution campaign involves repeated cycles of the following steps [7] [9]:

- Library Generation: Creating genetic diversity through methods like error-prone PCR (EP-PCR) to introduce random mutations throughout the gene [7].

- Expression and Screening: Expressing the mutant library in a host system (e.g., E. coli, S. cerevisiae) and screening for the desired function using a high-throughput assay.

- Selection: Identifying the top-performing variants from the screen.

- Gene Recovery and Reiteration: Isolating the genes from the best variants and using them as templates for the next round of evolution.

This workflow is depicted in the following diagram.

Detailed Protocol: A Novel Directed Evolution Approach for β-glucosidase

A 2025 study provides a concrete example of an advanced directed evolution protocol designed to co-evolve β-glucosidase (16BGL) for both enhanced activity and organic acid tolerance [9]. The study initially found that both rational design and traditional directed evolution (error-prone PCR) failed to produce the desired improvements, highlighting the need for more sophisticated methods.

Methodology: SEP and DDS The researchers developed a combined approach of Segmental Error-prone PCR (SEP) and Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS):

- Segmental Error-prone PCR (SEP): The target gene (16bgl) was divided into four segments. Error-prone PCR was performed on each segment separately to introduce mutations, ensuring an even distribution of mutations across the entire gene and minimizing the number of deleterious mutations.

- Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS): The mutated segments from SEP were assembled into full-length genes using a primerless overlap extension PCR. This step recombines beneficial mutations from different segments.

- In Vivo Recombination in S. cerevisiae: The assembled genes were then cloned into a yeast expression vector and transformed into S. cerevisiae. The high innate recombination efficiency of yeast further shuffles the mutant sequences, increasing library diversity.

Key Results The SEP-DDS method successfully generated a variant, 16BGL-3M, with three amino acid substitutions (N386D, G467E, and S541D). This variant showed significant improvements over the wild-type enzyme [9]:

- Specific activity increased by 1.5-fold.

- Tolerance to formic acid (15 mg/mL) increased by 2.1-fold.

- The kinetic parameter ( k{cat}/Km ) was enhanced by 1.6-fold.

This case study demonstrates how novel directed evolution techniques can successfully optimize multiple enzyme properties simultaneously, a task that proved insurmountable for rational design and traditional evolution in this instance.

Protocol: Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE)

A 2025 study introduced ALDE to address the challenge of epistasis (non-additive interactions between mutations) in directed evolution [5]. The workflow was applied to optimize five epistatic residues in the active site of a protoglobin (ParPgb) for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction.

Methodology:

- Define Design Space: Five key active-site residues were selected, defining a sequence space of ( 20^5 ) (3.2 million) possible variants.

- Initial Library Construction: An initial library of mutants was generated via PCR-based mutagenesis and screened to gather initial sequence-fitness data.

- Machine Learning Model Training: The collected data was used to train a supervised ML model to predict fitness from sequence.

- Variant Proposal and Acquisition: An acquisition function used the trained model to rank all sequences in the design space. The top N proposed variants were selected for the next round of testing.

- Iterative Cycling: The newly tested variants provided additional labeled data to retrain and improve the ML model in the next cycle.

Key Results: In just three rounds of ALDE (exploring only ~0.01% of the design space), the researchers optimized the enzyme's function. The yield of the desired cyclopropane product increased dramatically from 12% to 93%, with high diastereoselectivity (14:1) [5]. This demonstrates the power of integrating machine learning to efficiently navigate complex fitness landscapes where standard directed evolution struggles.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful directed evolution relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions used in the featured experiments [9] [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (EP-PCR) Kit | Introduces random mutations throughout the gene during amplification using manganese ions or unbalanced dNTP concentrations [7] [9]. |

| Segmental EP-PCR (SEP) Reagents | A variation where the gene is segmented before EP-PCR to ensure even mutation distribution and reduce deleterious mutations [9]. |

| Yeast Expression Vector (e.g., pYAT22) | Plasmid for constitutive secretion and expression of the target enzyme in S. cerevisiae; includes promoters, signal peptides, and selection markers [9]. |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae Host Strain | Eukaryotic expression host prized for high recombination efficiency, post-translational modifications, and secretory expression [9]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay | A critical method (e.g., based on fluorescence, absorbance, or chromatography) for rapidly testing thousands of variants for the desired function [7] [5]. |

| Machine Learning Model (ALDE) | Computational tool that learns sequence-function relationships from data to propose beneficial variants, drastically reducing screening effort [5]. |

Comparative Analysis and Research Applications

Performance in Key Research Areas

The utility of directed evolution and rational design is best illustrated by their performance in real-world applications. The table below compares their outcomes across different biotechnological domains.

Table 3: Comparison of Applications and Outcomes in Protein Engineering

| Application Area | Engineering Method | Specific Example & Mutagenesis | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Industrial Enzymes | Directed Evolution | β-glucosidase (16BGL) via SEP-DDS [9] | 1.5x higher activity & 2.1x higher acid tolerance |

| Gene Therapy (AAV Capsids) | Rational Design / Directed Evolution / ML | AAV capsids engineered via rational design & directed evolution [11] [12] | Improved transduction efficiency, reduced immunogenicity |

| Therapeutics (Insulin) | Rational Design | Insulin via site-directed mutagenesis [7] | Generation of fast-acting monomeric insulin |

| Non-Native Biocatalysis | Active Learning-Assisted DE | ParPgb protoglobin via ALDE for cyclopropanation [5] | Yield increased from 12% to 93% with high selectivity |

| Agriculture | Directed Evolution | 5-enolpyruvyl-shikimate-3-phosphate synthase via EP-PCR [7] | Enhanced kinetics & herbicide tolerance (glyphosate) |

The Evolving Synergy in Advanced Applications

In cutting-edge fields like gene therapy, the distinction between directed evolution and rational design is blurring into a powerful synergy. For example, engineering the capsid of Adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors—a critical step for effective and safe gene delivery—now routinely integrates multiple approaches [11] [12]:

- Rational design leverages structural insights to make specific changes.

- Directed evolution allows for the unbiased selection of superior capsid variants from large random libraries.

- Machine learning analyzes high-throughput screening data to build predictive models that accelerate the discovery of novel capsids with improved tissue targeting, reduced immunogenicity, and higher transduction efficiency.

This integrated framework represents the future of protein engineering, where computational and experimental methods are combined to solve complex biological challenges more efficiently.

In the quest to engineer biological systems, two methodologies have emerged as the foundational pillars of protein engineering: rational design and directed evolution. While they originate from different philosophical approaches—one a product of calculated design and the other of empirical selection—they are not mutually exclusive. Instead, they form a continuous spectrum, a unifying framework we term the "Evolutionary Design Spectrum." This guide provides an objective comparison for researchers and drug development professionals, detailing the performance, applications, and experimental protocols of these core methodologies. The field is increasingly moving toward hybrid approaches that integrate the precision of rational design with the explorative power of directed evolution, a synergy further accelerated by machine learning and artificial intelligence [11] [13] [1].

Core Methodology Comparison

The following table summarizes the fundamental characteristics, advantages, and limitations of rational design and directed evolution.

Table 1: Core Methodological Comparison of Rational Design and Directed Evolution

| Feature | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Principle | Structure-based computational design [1] | Iterative laboratory mimicry of natural evolution [14] [2] |

| Knowledge Requirement | High: Requires detailed 3D protein structure and mechanism [13] [1] | Low: Can proceed without prior structural or mechanistic knowledge [2] |

| Typical Workflow | In silico modeling → Target mutagenesis → Experimental validation | Library creation → High-throughput screening/selection → Iteration [14] [2] |

| Key Strength | High precision; ability to create novel folds and functions [13] | Discovers non-intuitive, synergistic mutations; bypasses limited predictability [2] |

| Primary Limitation | Limited by accuracy of structural models and force fields [13] | High-throughput screening is a major bottleneck [15] [2] |

| Best Suited For | Engineering well-characterized proteins; designing novel active sites | Optimizing complex traits (e.g., stability, activity) under industrial conditions [15] |

Quantitative Performance Data

The commercial and practical impact of these approaches is reflected in market data and application areas. The table below presents a quantitative comparison based on industry forecasts and usage.

Table 2: Market Share and Application Analysis

| Parameter | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Projected Market Share (2035) | ~53% (Largest share) [16] | Segment of Rational Designing, Directed Evolution, and Semi-Rational Designing [16] |

| Market CAGR (2024-2035) | ~15% [16] | Part of overall protein engineering market (CAGR ~14.1%) [16] |

| Dominant Application | Therapeutics (78% of market share) [16] | Therapeutics (78% of market share) [16] |

| Key Protein Type | Antibodies (48% market share) [16] | Enzymes [15] [17] |

| Notable Successes | De novo protein design (e.g., Top7) [13] | Evolved subtilisin E (256x activity in organic solvent) [14] |

Experimental Protocols in Practice

Protocol 1: Directed Evolution via Error-Prone PCR

This is a classic directed evolution protocol for enhancing protein stability or function without structural information [14] [2].

- Diversity Generation (Error-Prone PCR): The gene of interest is amplified using a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) under conditions that reduce fidelity. This is achieved by using a non-proofreading polymerase (e.g., Taq polymerase), biasing dNTP concentrations, and adding manganese ions (Mn²⁺) to introduce random mutations at a rate of 1-5 mutations per kilobase [2].

- Library Construction: The mutated PCR products are cloned into an expression vector and transformed into a host organism (e.g., E. coli) to create a library of variant clones.

- High-Throughput Screening: Individual clones are expressed, and their proteins are screened for the desired trait. For example, to improve thermostability, the protein library may be heated to a denaturing temperature before assaying for residual catalytic activity. Screening is often done in 96- or 384-well microtiter plates using colorimetric or fluorometric assays [2].

- Iteration: The genes from the top-performing variants are isolated and used as templates for subsequent rounds of mutagenesis and screening, often under increasingly stringent conditions (e.g., higher temperature), to accumulate beneficial mutations [2].

Protocol 2: Rational Design via Structure-Based Modeling

This protocol is used when a protein's structure is known, allowing for targeted improvements [13] [1].

- Structural Analysis: Obtain a high-resolution 3D structure of the target protein via X-ray crystallography or cryo-EM, or generate a predictive model using tools like AlphaFold [15]. Analyze the structure to identify key residues involved in substrate binding, catalysis, or structural stability.

- In Silico Design: Using computational software (e.g., Rosetta), design specific amino acid substitutions predicted to enhance the target property. For instance, to improve stability, one might introduce residues that form salt bridges or improve hydrophobic core packing [13].

- Targeted Mutagenesis: Instead of random mutation, use site-directed mutagenesis or site-saturation mutagenesis to generate a small, focused library of variants at the predetermined residues [2].

- Experimental Validation: Express and purify the designed variants and characterize them using biochemical assays to validate the computational predictions.

Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the core iterative process of a directed evolution campaign, highlighting its empirical nature.

The following diagram contrasts the linear, knowledge-driven path of rational design with the iterative, empirical cycle of directed evolution, positioning semi-rational design as a bridge between them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | A optimized reagent system (e.g., non-proofreading polymerase, Mn²⁺) for introducing random mutations into a gene during amplification [2]. |

| DNase I | Enzyme used in DNA shuffling to randomly fragment a pool of homologous genes, facilitating in vitro recombination to create chimeric variants [14] [2]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Reagents for performing precise, targeted mutations in a plasmid, essential for both rational design and semi-rational saturation mutagenesis [2]. |

| Cell-Free Gene Expression System | A machinery for synthesizing proteins without using living cells, enabling rapid production and testing of protein variants in a high-throughput manner [17]. |

| AlphaFold / Rosetta | Computational platforms for protein structure prediction (AlphaFold) and de novo protein design or energy minimization (Rosetta) [13] [15]. |

| Phage Display System | A selection-based platform where protein variants are displayed on the surface of bacteriophages, allowing for isolation of binders from large libraries [14]. |

The historical dichotomy between rational design and directed evolution is giving way to a more integrated and powerful paradigm. The future of protein engineering lies in the hybridization of this evolutionary design spectrum, leveraging the precision of structure-based design with the explorative power of evolution, all accelerated by machine learning. Modern approaches use machine learning models trained on high-throughput screening data to predict beneficial mutations and guide subsequent library design, dramatically reducing experimental burden [11] [13] [17]. As AI-driven tools continue to mature, they promise to further unify these approaches, enabling the systematic exploration of the vast protein functional universe and delivering bespoke biomolecules for advances in medicine, sustainability, and biotechnology [13].

The evolution of biological engineering from classical strain improvement to modern directed evolution represents a fundamental shift in our ability to harness biological systems for human applications. Classical strain engineering relied heavily on random mutagenesis and phenotypic screening without knowledge of the underlying genetic mechanisms, whereas modern directed evolution employs sophisticated laboratory techniques to emulate natural evolution in a targeted, accelerated fashion. This transition has transformed protein engineering, metabolic engineering, and therapeutic development, enabling researchers to tailor biocatalysts, pathways, and entire organisms with unprecedented precision.

This progression mirrors a broader philosophical framework in biological engineering. As recent perspectives suggest, all design approaches can be considered evolutionary—they combine variation and selection iteratively, differing primarily in their exploratory power and how they leverage prior knowledge [8]. This understanding unifies seemingly disparate engineering approaches, placing them on a continuous evolutionary design spectrum where methods are characterized by their throughput and generational count.

Historical Progression of Engineering Methods

Classical Strain Engineering (Mid-20th Century)

The earliest forms of biological engineering predated understanding of molecular genetics. Classical strain engineering emerged in the mid-20th century when researchers began utilizing chemical mutagens to induce mutations in microorganisms.

- Chemical Mutagenesis: Early work involved exposing organisms to chemical mutagens to induce random mutations throughout the genome. A seminal 1964 study used chemical mutagenesis to induce a xylitol utilization phenotype in Aerobacter aerogenes, representing one of the first deliberate attempts to engineer new biological functions in the laboratory [14].

- Experimental Evolution: Parallel developments included in vitro evolution experiments, such as Sol Spiegelman's work reconstructing RNA replication in test tubes to observe evolutionary principles under different selective pressures [14].

- Limitations: These early methods provided no control over mutation targeting and required laborious screening processes with limited throughput.

Foundation of Modern Directed Evolution (1990s)

The 1990s witnessed the emergence of modern directed evolution as a formal discipline, characterized by iterative cycles of diversification and selection applied to specific biomolecular targets.

- Error-Prone PCR: A landmark 1994 study demonstrated the power of repeated rounds of PCR-driven random mutagenesis to enhance protein properties, evolving subtilisin E to exhibit 256-fold higher activity in dimethylformamide through three sequential rounds [14].

- DNA Shuffling: Developed by Willem Stemmer, this method mimicked natural recombination by fragmenting and reassembling genes from different parents. Application to β-lactamase produced mutants with 32,000-fold increased resistance to cefotaxime—dramatically outperforming non-recombinogenic methods [14].

- In Vitro Selection Methods: Techniques like phage display enabled enrichment of specific peptides with desired binding properties from large libraries, proving particularly valuable for antibody engineering [14].

Semi-Rational and Computational Design (2000s-Present)

The recognition that purely random approaches sampled only a tiny fraction of possible sequence space drove the development of semi-rational strategies that leverage biological knowledge and computational power.

- Knowledge-Based Library Design: These approaches utilize information on protein sequence, structure, and function to preselect promising target sites and limited amino acid diversity, creating smaller, higher-quality libraries [10] [4].

- Computational Tools: Methods like HotSpot Wizard and 3DM analysis combine evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments with structural data to identify functional hotspots and guide library design [4].

- Machine Learning Integration: Computational analysis of high-throughput screening data enables predictive algorithms that accelerate the discovery of improved variants [11].

Table 1: Historical Timeline of Key Methodological Developments

| Time Period | Dominant Methodology | Key Innovations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1980s | Classical Strain Engineering | Chemical mutagens, adaptive evolution | Xylitol utilization in bacteria [14] |

| 1990s | Modern Directed Evolution | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling | Subtilisin E enhancement [14] |

| 2000s | Recombination Techniques | StEP, family shuffling | Thermostable enzymes [14] |

| 2010s-Present | Semi-Rational & Computational Design | Structure-guided design, machine learning | AAV capsid engineering [11] |

Comparative Analysis: Directed Evolution vs. Rational Design

Fundamental Philosophical Differences

The distinction between directed evolution and rational design represents one of the central tensions in modern biological engineering, though they are increasingly recognized as complementary points on an evolutionary design spectrum [8].

- Directed Evolution emulates natural evolutionary processes through iterative generation of molecular diversity followed by screening or selection for desired properties, requiring no detailed structural knowledge [14].

- Rational Design relies on comprehensive understanding of structure-function relationships to make precise, targeted modifications [18].

- Semi-Rational Approaches have emerged as a hybrid strategy, using evolutionary information and structural insights to design smaller, smarter libraries [10] [4].

Practical Methodological Comparison

The practical implementation of these approaches differs significantly in their requirements, strengths, and limitations, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Methodological Comparison of Protein Engineering Approaches

| Aspect | Directed Evolution | Semi-Rational Design | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Required Prior Knowledge | Minimal; no structural information needed | Moderate; sequence/structure data helpful | Extensive; detailed mechanistic understanding essential |

| Library Size | Very large (10^6-10^12 members) | Small to moderate (<1000 to 10^4 members) | Minimal (often <10 variants) |

| Screening Throughput | Must be very high | Moderate to high | Can be low |

| Typical Iterations | Multiple rounds (3-10+) | Fewer rounds (1-3) | Often single implementation |

| Development Time | Weeks to months | Weeks | Can be rapid if knowledge exists |

| Key Limitations | Vast sequence space undersampled | Dependent on quality of prior knowledge | Limited by current structural prediction capabilities |

| Representative Tools | Error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling | 3DM, HotSpot Wizard [4] | Molecular dynamics, Rosetta [4] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Directed Evolution Protocol

The core directed evolution workflow follows an iterative cycle of diversity generation and screening, typically requiring multiple rounds to achieve significant improvements.

Library Construction: Generate genetic diversity through:

Screening/Selection: Identify improved variants through:

Hit Characterization: Sequence and characterize top performers to understand mutation effects

Iteration: Use best variants as templates for subsequent rounds

The following diagram illustrates this iterative process:

Semi-Rational Design Workflow

Semi-rational approaches incorporate knowledge-based filtering to reduce library size while maintaining functional diversity, as exemplified by tools like HotSpot Wizard and 3DM analysis [4].

- Target Identification: Select protein system and define engineering goals

- Sequence Analysis: Perform multiple sequence alignments and phylogenetic analysis to identify evolutionarily variable positions [4]

- Structure Analysis: Map variable positions to three-dimensional structure, focusing on regions near active sites, substrate access tunnels, or domain interfaces [4]

- Library Design: Restrict diversity to structurally and evolutionarily informed positions using:

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis: At individual hot spots

- Focused Combinatorial Libraries: Combining promising mutations

- Screening & Characterization: Evaluate smaller libraries with moderate-throughput methods

The relationship between these methodologies and their historical development can be visualized as follows:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of directed evolution and protein engineering requires specific reagents and tools. The following table catalogs essential resources referenced in the literature.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Protein Engineering

| Reagent/Tool | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Molecular Biology Reagent | Introduces random mutations throughout gene | Early directed evolution rounds [14] |

| DNase I | Enzyme | Fragments genes for DNA shuffling | Creating chimeric libraries from homologs [14] |

| HotSpot Wizard | Computational Tool | Identifies mutable positions from sequence/structure data | Focused library design [4] |

| 3DM Database | Bioinformatics Resource | Superfamily analysis for evolutionary guidance | Identifying allowed substitutions [4] |

| Rosetta Software | Computational Suite | Protein structure prediction and design | De novo enzyme design [4] |

| Phage Display System | Selection Platform | Library screening based on binding affinity | Antibody engineering [14] |

| Unnatural Amino Acids | Chemical Reagents | Expand genetic code for novel functionality | Incorporating novel chemistries [14] |

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Emerging Technologies and Applications

The field continues to evolve rapidly, with several recent developments pushing the boundaries of what's possible in biological engineering.

- Machine Learning Integration: Computational analysis of high-throughput screening data enables predictive algorithms that dramatically accelerate the discovery of improved variants, particularly in AAV capsid engineering for gene therapy [11].

- In Cell Evolution Systems: Platforms like PROTEUS enable evolution of molecules directly in mammalian cells rather than bacterial systems, potentially accelerating development of human therapeutics [19].

- DNA-Encoded Libraries: DEL technology has evolved from empirical screening to rational, precision-oriented strategies incorporating fragment-based approaches and covalent warheads [20].

- Automated Continuous Evolution: Systems that combine continuous mutagenesis with automated screening significantly reduce hands-on time and increase evolutionary throughput [19].

Conceptual Framework: The Evolutionary Design Spectrum

A unifying perspective emerging in the field posits that all design processes—from traditional design to directed evolution—follow a similar cyclic process and exist within an evolutionary design spectrum [8]. This framework characterizes methodologies by:

- Throughput: How many design variants can be tested simultaneously

- Generation Count: How many iterative cycles are employed

- Exploratory Power: The product of throughput and generation count

- Knowledge Leverage: How effectively the method exploits prior information

This conceptual model helps reconcile seemingly opposed engineering approaches and provides a valuable framework for selecting appropriate methods for specific biological design challenges.

The journey from classical strain engineering to modern directed evolution represents more than just technical progress—it reflects a fundamental evolution in how we approach biological design. The distinction between directed evolution and rational design has blurred with the emergence of semi-rational and computational approaches that leverage the strengths of both philosophies. Current research increasingly operates within a unified evolutionary design paradigm that recognizes all engineering approaches as existing on a spectrum of iterative variation and selection.

Future advances will likely continue to integrate multidisciplinary approaches, further breaking down barriers between traditional engineering disciplines. As machine learning algorithms become more sophisticated and structural databases expand, the line between designed and evolved biological systems will continue to fade, opening new possibilities for engineering biology to address pressing challenges in medicine, energy, and sustainability.

Methodologies in Action: Techniques, Workflows, and Real-World Applications

In the ongoing methodological comparison between rational design and directed evolution for protein engineering, rational design stands out for its hypothesis-driven approach. This paradigm leverages precise tools to understand and manipulate protein structure and function, contrasting with the extensive screening used in directed evolution [21] [1]. This guide focuses on two core technical toolkits within rational design: site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) and computational modeling, providing a detailed comparison of their methodologies, applications, and performance.

Defining the Rational Design Paradigm

Rational design is a knowledge-based protein engineering strategy that relies on detailed understanding of a protein's three-dimensional structure, functional mechanisms, and catalytic activity to make targeted, predictive changes [21] [22]. This approach operates on a design-based paradigm where computational models and structural data are used to predict the outcomes of protein modifications before experimental validation [21]. This contrasts with directed evolution, which mimics natural selection by generating vast libraries of random mutants and screening for desired traits without requiring prior structural knowledge [1] [4]. While directed evolution is powerful for exploring unknown sequence spaces, rational design offers precision and deeper insights into protein structure-function relationships, making it ideal when specific alterations are needed to enhance stability, specificity, or catalytic activity [1] [22].

Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Experimental Workflow and Protocols

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) is a foundational experimental technique in rational design, allowing researchers to introduce precise, pre-determined changes into a DNA sequence. It is the primary method for testing hypotheses generated from computational models or structural analyses.

Core Experimental Protocol

The following workflow details a high-efficiency method for site-directed mutagenesis, particularly effective for large plasmids [23].

Step 1: Primer Design

- Design two pairs of partially complementary primers: one pair are "mutation-assisting primers" (MAFP and MARP) that bind to a known vector sequence, and the other pair are "mutation primers" (MFP and MRP) containing the desired mutation [23].

- Primers should be 33-35 base pairs long with a GC content of 45-65%. The overlapping region between complementary primers should be 15-20 bp, with the mutation site located within this overlap [23].

Step 2: PCR Amplification

- Perform two separate PCR reactions using a high-fidelity DNA polymerase capable of amplifying large fragments (e.g., Phanta Max Master Mix or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase) [23].

- PCR I: Uses primers MAFP and MRP.

- PCR II: Uses primers MARP and MFP.

- These reactions produce two overlapping DNA fragments that collectively represent the entire plasmid.

Step 3: Purification and Ligation

- Purify the PCR products from both reactions using a gel extraction kit [23].

- Mix the fragments at a 1:1 molar ratio (with a minimum of 30 ng of each fragment) and perform recombinational ligation using an enzyme mix such as Exnase II [23].

Step 4: Transformation and Verification

- Transform the ligated product into competent E. coli cells [24].

- Isolve plasmids from resulting colonies and verify the mutation by DNA sequencing. It is typically not necessary to sequence the entire plasmid [24].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential Reagents for Site-Directed Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Products/Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies target DNA with minimal error rates. Essential for large plasmid amplification. | Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (NEB), Phanta Max Master Mix (Vazyme) [23]. |

| Specialized Primers | Designed to introduce specific mutations and facilitate recombinational ligation. | Should be 33-35 bp; PAGE-purified for sequences >40-50 nt to avoid synthesis errors [24]. |

| Cloning Kit | Provides optimized enzymes for fragment assembly and ligation. | Exnase II kit, Quick-Change Kit (Thermo Scientific) [23]. |

| Competent E. coli | Host cells for plasmid propagation after mutagenesis. | Chemically competent cells suitable for cloning; electroporation requires prior salt removal [24]. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests the methylated template plasmid post-PCR to reduce background. | Selective digestion of parent plasmids propagated in E. coli [24]. |

Computational Modeling: Algorithms and Workflows

Computational protein design (CPD) employs physics-based energy functions and search algorithms to identify amino acid sequences that fold into target structures and perform desired functions.

Core Computational Workflow

The process for de novo active-site design exemplifies the integration of various computational tools to create novel enzymes.

Step 1: Active Site and Scaffold Identification

- The process begins with accurate modeling of the chemical reaction's transition state, often requiring Quantum Mechanical (QM) calculations to understand the forces and geometry needed for catalysis [21].

- Protein scaffolds are then screened to identify those with structural features compatible with hosting the designed active site and transition state [21].

Step 2: Sequence and Conformation Optimization

- Using fixed-backbone or flexible-backbone algorithms, the identities and conformations of amino acid side chains are optimized to stabilize the transition state and the overall protein fold [21].

- Powerful search algorithms like Dead End Elimination and the K* algorithm are used to navigate the vast conformational space and find optimal sequences [21].

Step 3: Design Ranking and Validation

- Final designs are ranked based on calculated transition state binding energy and the geometry of the catalytic residues [21].

- Top-ranking designs are synthesized experimentally and tested for activity.

Key Computational Tools and Performance

Table 2: Key Computational Tools for Rational Protein Design

| Computational Tool/Method | Primary Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ROSETTA | De novo protein design & structure prediction; identifies sequences stabilizing backbone geometry. | Design of novel enzymes for retro-aldol reaction and Kemp elimination [21]. |

| K* Algorithm | Flexible backbone design with rotamer library; estimates conformational entropy. | Redesign of gramicidin S synthetase A for altered substrate specificity (600-fold shift for Phe→Leu) [4]. |

| Molecular Docking | Predicts ligand binding orientation & affinity in a target site. | Study of antitubulin anti-cancer agents & estrogen receptor binding domains [25]. |

| DEZYMER/ORBIT | Early protein design software for constructing novel sequences for a target backbone. | Used in the design of metalloprotein active sites in thioredoxin scaffolds [21]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulates physical atom movements over time; assesses complex stability & dynamics. | Identified key residues in haloalkane dehalogenase access tunnels, leading to 32-fold activity improvement [4]. |

Performance Comparison and Synergistic Applications

Comparative Analysis of Key Metrics

Table 3: Performance Comparison Between Core Rational Design Techniques

| Performance Metric | Site-Directed Mutagenesis | Computational Protein Design |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Objective | Test hypotheses by introducing specific, pre-determined mutations. | De novo design of proteins & active sites or re-engineer existing ones. |

| Key Strength | Direct experimental validation; highly precise at the DNA level. | Ability to explore vast sequence spaces in silico and generate novel proteins. |

| Throughput | Low to medium (requires cloning and sequencing for each variant). | High in silico, but relies on experimental testing of top designs. |

| Typical Library Size | One to several variants. | Dozens to hundreds of in silico designs, with a handful synthesized. |

| Success Rate | High for introducing the mutation; functional success varies. | Can be low, but provides fundamental insights even from failures [21]. |

| Reported Efficacy | Successful mutagenesis of plasmids up to 17.3 kb [23]. | >10⁷-fold activity increase in designing organophosphate hydrolase [21]. |

| Resource Intensity | Laboratory-intensive (PCR, cloning, sequencing). | Computationally intensive, requiring significant processing power. |

Synergistic Use in Semi-Rational Design

The combination of computational modeling and SDM forms the basis of semi-rational design, which creates small, high-quality libraries with a high frequency of improved variants [4]. For example:

- Sequence-Based Redesign: Tools like the HotSpot Wizard and 3DM database analyze evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments to identify mutable "hotspot" residues. Researchers then use SDM to create focused libraries. This approach yielded esterase variants with 200-fold improved activity and 20-fold enhanced enantioselectivity from a library of only ~500 variants [4].

- Structure-Based Redesign: Molecular dynamics simulations can identify residues that influence catalytic activity without being part of the active site, such as those lining substrate access tunnels. SDM of these residues in a haloalkane dehalogenase resulted in a 32-fold improvement in activity by restricting water access [4].

Site-directed mutagenesis and computational modeling are complementary pillars of the rational design toolkit. SDM provides the essential experimental pathway for validating precise genetic alterations, while computational modeling vastly expands the design space for creating novel proteins and enzymes. When used individually, SDM excels at hypothesis-driven, targeted changes, whereas computational methods empower the de novo creation of function. Their most powerful application, however, lies in their integration within a semi-rational framework. This synergy leverages computational power to intelligently reduce the experimental screening burden, leading to more efficient engineering of proteins with tailored properties for therapeutics, biotechnology, and basic research.

Directed evolution stands as a powerful methodology in protein engineering, mimicking the principles of natural selection to optimize enzymes and biomolecules for specific applications. Unlike rational design, which relies on detailed structural knowledge to make precise, calculated mutations, directed evolution explores sequence-function relationships through iterative diversification and selection, often yielding improvements that are difficult to predict computationally [1] [3]. At the heart of every successful directed evolution campaign lies a critical first step: the generation of genetic diversity. The quality, depth, and character of the initial mutant library profoundly influence the potential for discovering variants with enhanced properties.

Among the numerous techniques developed for creating diversity, error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling have emerged as two foundational strategies. Error-prone PCR introduces random point mutations throughout a gene, mimicking the slow accumulation of single nucleotide changes. In contrast, DNA shuffling recombines fragments from related DNA sequences, accelerating evolution by exchanging blocks of mutations and functional domains, akin to sexual recombination in nature [26]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two methods, equipping researchers with the data and protocols needed to select the optimal diversity-generation engine for their projects.

Methodological Comparison: Error-Prone PCR vs. DNA Shuffling

The choice between error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling depends on the project's goals, the availability of starting sequences, and the desired type of diversity. The table below summarizes the core principles, advantages, and limitations of each technique.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Error-Prone PCR and DNA Shuffling

| Feature | Error-Prone PCR | DNA Shuffling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Introduces random point mutations during PCR amplification using low-fidelity conditions [27]. | Fragments and reassembles related genes, allowing recombination of beneficial mutations [3] [26]. |

| Type of Diversity | Primarily point mutations (A→G, C→T, etc.) [28]. | Recombination of larger sequence blocks; can also include point mutations [28]. |

| Best Suited For | Optimizing a single gene; exploring local sequence space around a parent sequence. | Rapidly improving function by mixing beneficial mutations from multiple homologs or variants [26]. |

| Key Advantage | Simple to perform; does not require prior knowledge or related sequences [3]. | Dramatically accelerates evolution by combining mutations; can lead to synergistic effects [26]. |

| Primary Limitation | Explores a limited sequence space; beneficial mutations may be isolated and not combined efficiently. | Requires multiple homologous parent sequences for effective shuffling [28]. |

Performance Analysis: Quantitative Experimental Data

The ultimate test of any diversity-generation method is its performance in real-world protein engineering campaigns. The following table compiles experimental data from published studies, highlighting the efficacy of both error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling in enhancing key enzyme properties.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data from Protein Engineering Studies

| Protein / Enzyme | Method Used | Key Mutations/Recombinations | Experimental Outcome | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| D-lactonohydrolase | Error-prone PCR + DNA shuffling | Mutant E-861 with A352C, G721A mutations after 3 rounds of epPCR and 1 round of shuffling [29]. | 5.5-fold higher activity than wild-type; stability at low pH significantly improved (75% vs 40% activity retention at pH 6.0) [29]. | Sheng Wu Gong Cheng Xue Bao. 2005 |

| Glycolyl-CoA Carboxylase | Error-prone PCR | Not specified in search results. | Not specified in search results. | PMC. 2023 [3] |

| β-Lactamase | DNA Shuffling (Family Shuffling) | Recombination of multiple homologous sequences. | Accelerated evolution of novel function and specificity compared to point mutagenesis alone [26]. | Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2000 [26] |

| Various Enzymes (Lipases, Proteases, Peroxidases) | DNA Shuffling | Recombination of natural diversity from homologs. | Successfully evolved increased thermostability, altered pH activity, resistance to organic solvents, and altered substrate specificity for industrial applications [26]. | Current Opinion in Chemical Biology. 2000 [26] |

Case Study: The Superiority of DNA Shuffling

Research indicates that DNA shuffling, particularly when applied to a family of homologous genes, can be far more effective than methods based on point mutation alone. One landmark study demonstrated that shuffling just three genes could yield a 540-fold improvement in activity, a level of enhancement that would be exceptionally difficult to achieve through sequential rounds of error-prone PCR [26]. This performance advantage stems from the method's ability to recombine beneficial mutations that arise in different lineages, simultaneously purging deleterious mutations and exploring a much broader and richer functional sequence space.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Error-Prone PCR

This protocol generates a library of random point mutations in a target gene.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Template DNA: The gene of interest in a plasmid vector.

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers that flank the cloning site of the target gene.

- Low-Fidelity Polymerase: Taq polymerase is commonly used due to its lack of proofreading activity [27].

- Error-Prone Buffer: A modified PCR buffer. This can include manganese ions (Mn²⁺), which is known to reduce the fidelity of the polymerase by promoting misincorporation of nucleotides [27].

- Unbalanced dNTPs: Using an unequal mixture of dATP, dTTP, dGTP, and dCTP can further increase the error rate.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 50 µL PCR reaction mixture containing:

- 10-100 ng of template DNA.

- 0.5 µM each of the forward and reverse primers.

- 1x specialized error-prone PCR buffer (often containing MnCl₂).

- An unbalanced dNTP mix (e.g., 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dGTP, 1 mM dCTP, 1 mM dTTP).

- 2.5 units of Taq polymerase.

- Thermocycling: Run the following PCR program:

- Initial Denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes.

- Amplification (25-30 cycles):

- Denature: 95°C for 30 seconds.

- Anneal: 50-60°C (primer-specific) for 30 seconds.

- Extend: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of the gene.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 minutes.

- Purification: Purify the resulting PCR product using a standard PCR purification kit.

- Cloning: Digest the purified product and the expression vector with the appropriate restriction enzymes. Ligate the mutated gene insert into the vector.

- Transformation: Transform the ligated DNA into a competent host strain (e.g., E. coli) to create the mutant library for screening.

Protocol 2: DNA Shuffling

This protocol recombines multiple parent genes to create a chimeric library.

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Parental DNA Sequences: Multiple related genes (homologs or pre-evolved variants) to be shuffled.

- DNase I: An enzyme to randomly fragment the parental DNA.

- PCR Reagents: Including a high-fidelity DNA polymerase, primers, and dNTPs.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Fragmentation: Combine the purified parental DNA sequences and digest with DNase I in the presence of Mn²⁺ to generate random fragments of 50-200 base pairs.

- Purification: Gel-purify the fragments to remove any undigested DNA or very small fragments.

- Reassembly PCR: In a PCR tube without primers, the fragments are subjected to a thermocycling program designed to allow them to anneal based on sequence homology and be extended by the DNA polymerase. This self-priming elongation reassembles the fragments into full-length chimeric genes.

- Program: 40-50 cycles of: 94°C for 30 seconds (denaturation), 50-60°C for 30 seconds (annealing), and 72°C for 1 minute (extension).

- Amplification: Use a standard PCR with outer primers to amplify the full-length, reassembled genes.

- Cloning and Transformation: Clone the final PCR product into an expression vector and transform into a host cell to create the library for screening.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the key procedural differences between error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling, highlighting the iterative "Design-Make-Test-Analyze" cycle central to directed evolution.

Figure 1: Directed evolution workflow comparing error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling paths.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of directed evolution experiments requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details key solutions for generating and screening diversity.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Fidelity Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Catalyzes DNA amplification with a higher inherent error rate, introducing point mutations during PCR [27]. | Standard error-prone PCR protocol to create a random mutant library from a single parent gene. |

| DNase I | Enzymatically cleaves DNA into random fragments for the initial step of DNA shuffling [28]. | Fragmenting a pool of homologous parent genes prior to their recombination. |

| Specialized epPCR Kits | Commercial kits providing optimized buffers (with Mn²⁺) and nucleotide mixes to maximize and control mutation rates. | Generating a high-quality, diverse library with a predictable mutation frequency. |

| Yeast/Bacterial Display Systems | High-throughput screening platforms that link the displayed protein (phenotype) to its genetic code (genotype) [3] [27]. | Screening antibody mutant libraries for improved antigen binding using flow cytometry. |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | A platform for validating direct target engagement of drug candidates in intact cells, providing physiologically relevant confirmation of binding [30]. | Confirming that an evolved enzyme or therapeutic protein engages its intended target within a cellular environment. |

Both error-prone PCR and DNA shuffling are powerful, well-established engines for generating diversity in directed evolution. The choice is not a matter of which is universally superior, but which is most appropriate for the specific research context. Error-prone PCR offers a straightforward, accessible entry point for optimizing a single gene when no structural data or homologs are available. In contrast, DNA shuffling leverages the power of recombination to accelerate evolution dramatically, often leading to orders-of-magnitude greater improvements, but requires multiple starting sequences.

For the modern researcher, the most powerful strategy often involves a hybrid approach. Initial rounds of error-prone PCR can identify beneficial "hotspots," which can then be recombined and optimized using DNA shuffling or more targeted saturation mutagenesis. Furthermore, the integration of machine learning with these experimental methods is now creating a new paradigm, where high-throughput screening data from directed evolution guides computational models to predict even more effective variants, pushing the boundaries of protein engineering ever further [11].

In the context of modern protein engineering, which is primarily built upon the twin pillars of rational design and directed evolution, the ability to efficiently link genotype (the genetic code) to phenotype (the observable function) is paramount [31] [1]. While rational design uses detailed knowledge of protein structure to make precise, planned changes, directed evolution mimics natural selection in the laboratory through iterative rounds of diversification and selection to discover improved protein variants [1]. The success of directed evolution, in particular, is critically dependent on the methods used to analyze vast mutant libraries, making High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and Selection the indispensable engines of this approach [32] [31].

This guide provides an objective comparison of HTS and Selection methods. HTS refers to the process of evaluating each individual variant for a desired property, while Selection automatically eliminates non-functional variants by applying a selective pressure that allows only the desired ones to survive or propagate [32]. The choice between these strategies significantly impacts the throughput, cost, and ultimate success of a directed evolution campaign, and often determines its compatibility with different phenotypic assays.

Core Concepts and Definitions

High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

Screening involves the individual assessment of each protein variant within a library for a specific, measurable activity or property. Because every variant is tested, screening reduces the chance of missing a desired mutant but inherently limits the throughput to the capacity of the assay technology [32]. HTS methods often rely on colorimetric, fluorometric, or luminescent outputs to report on enzyme activity [32] [33]. A classic example is the use of microtiter plates (e.g., 96-well or 384-well formats), where robotic systems and plate readers automate the process of adding reaction components and measuring signals such as UV-vis absorbance or fluorescence [32].

Selection

In contrast, selection methods apply a conditional survival advantage to the host organism (e.g., bacteria or yeast) such that only cells harboring the functional protein of interest can proliferate or survive. This "rejective to the unwanted" feature makes selection intrinsically high-throughput, enabling the evaluation of extremely large libraries (often exceeding 10^11 members) without the need to handle each variant individually [32]. Common selection strategies are often based on complementing an essential gene or providing resistance to an antibiotic or toxin.

The Framework of Directed Evolution

Both HTS and Selection are core components of the directed evolution cycle. The process begins by introducing genetic diversity into a population of organisms, typically through random mutagenesis or gene recombination, to create a library of gene variants [31]. This library is then subjected to a screening or selection process designed to identify the tiny fraction of organisms that produce proteins with the desired trait. The genes from these "hits" are then isolated and used as the template for the next round of diversification, in an iterative process that hones the protein's function [31].

Comparative Analysis: Screening vs. Selection

The following table summarizes the key operational differences between Screening and Selection methods.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Screening and Selection

| Feature | High-Throughput Screening (HTS) | Selection |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Evaluate every individual variant for a desired property [32]. | Apply selective pressure to automatically eliminate non-functional variants [32]. |

| Throughput | Lower than selection; limited by assay speed (e.g., (10^4)-(10^6) variants) [32]. | Very high; can access library sizes >(10^{11}) variants [32] [34]. |

| Key Advantage | Reduced chance of missing desired mutants; can quantify performance and rank variants [32]. | Extreme throughput; less resource-intensive for very large libraries [32]. |

| Primary Limitation | Throughput is a major bottleneck in directed evolution [32]. | Requires a direct link between protein function and host cell survival/propagation [32]. |

| Typical Readout | Fluorescence, luminescence, colorimetric absorption [32] [33]. | Cell growth, survival, or reporter-based propagation (e.g., phage) [32] [34]. |

Performance and Application in Directed Evolution

The choice between screening and selection has profound implications for the scale and outcome of a directed evolution project. The table below compares the performance of specific methodologies, highlighting their compatibility with different directed evolution goals.

Table 2: Comparison of Method Performance in Directed Evolution

| Method | Category | Typical Library Size | Key Application | Enrichment Factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates [32] | Screening | (10^2)-(10^4) | Enzyme activity assays with colorimetric/fluorometric readouts. | Not applicable (individual assessment) |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [32] | Screening | (10^6)-(10^8) | Sorting based on cell-surface display or intracellular fluorescence. | Up to 5,000-fold per round [32] |

| In Vitro Compartmentalization (IVTC) [32] | Screening/Selection | (10^8)-(10^{10}) | Cell-free expression and assays in water-in-oil emulsion droplets. | Enables screening of large libraries [32] |

| Plasmid Display [32] | Selection | >(10^{11}) | Physical linkage of protein to its encoding DNA for binding selection. | High, due to intrinsic linkage |

| mRNA Display [34] | Selection | (10^{13})-(10^{14}) | In vitro covalent linkage of protein to its encoding mRNA. | Extremely high, due to largest library sizes |

Key Insights from Experimental Data:

- Throughput vs. Control: Selection methods consistently achieve orders-of-magnitude higher throughput. For instance, mRNA display can handle libraries of up to (10^{14}) individual members, a size that is intractable for any screening method [34]. However, screening provides a level of quantitative control that selection often lacks, allowing researchers to rank variants by performance rather than just identifying survivors.

- Assay Flexibility and Compartmentalization: Screening methods like IVTC and FACS offer a powerful compromise. IVTC uses man-made compartments (e.g., water-in-oil emulsions) to create independent reactors for cell-free protein synthesis and enzyme reaction [32]. This circumvents the regulatory networks of in vivo systems and avoids the limitation of cellular transformation efficiency, allowing for larger library sizes than many other screening platforms [32]. FACS, when combined with methods like yeast surface display, can screen libraries of up to (10^9) clones and achieve enrichments of 6,000-fold for active clones in a single round [32].

- Directing Evolution for Complex Phenotypes: For engineering traits like substrate specificity, organic solvent resistance, or thermostability, the compatibility of the HTS or selection method with the phenotypic assay is the most critical factor [32]. While in vitro protein assays are quick to establish, they can suffer from poor translation to a cellular environment [33]. Phenotypic screens in live cells, though more resource-intensive, provide invaluable data on the overall effects of a molecule in a therapeutically relevant context [33].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Bead Display (A Screening Platform)

The ORBIT (Open-ended Random Bead Identification of Targets) bead display system is a representative screening platform that links genotype to phenotype by co-localizing peptides and their encoding DNA on the surface of beads [35].

Methodology:

- Library Construction: A DNA library encoding random peptides (e.g., 9 or 15 amino acids) fused to a carrier protein (e.g., beta-2-microglobulin) and a streptavidin-binding peptide (SBP) tag is generated.