Enzyme Kinetics and Thermodynamics: Bridging Fundamental Principles to Drug Discovery Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Enzyme Kinetics and Thermodynamics: Bridging Fundamental Principles to Drug Discovery Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of enzyme catalysis, the Michaelis-Menten framework, and the critical relationship between kinetics and reaction thermodynamics. The scope then progresses to cover advanced methodological frameworks for building thermodynamically consistent models, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing enzymatic activity, and finally, rigorous approaches for validating kinetic parameters and comparing inhibitor mechanisms. By synthesizing classical theory with modern computational and evolutionary perspectives, this review serves as a vital resource for leveraging enzymology in therapeutic discovery and optimization.

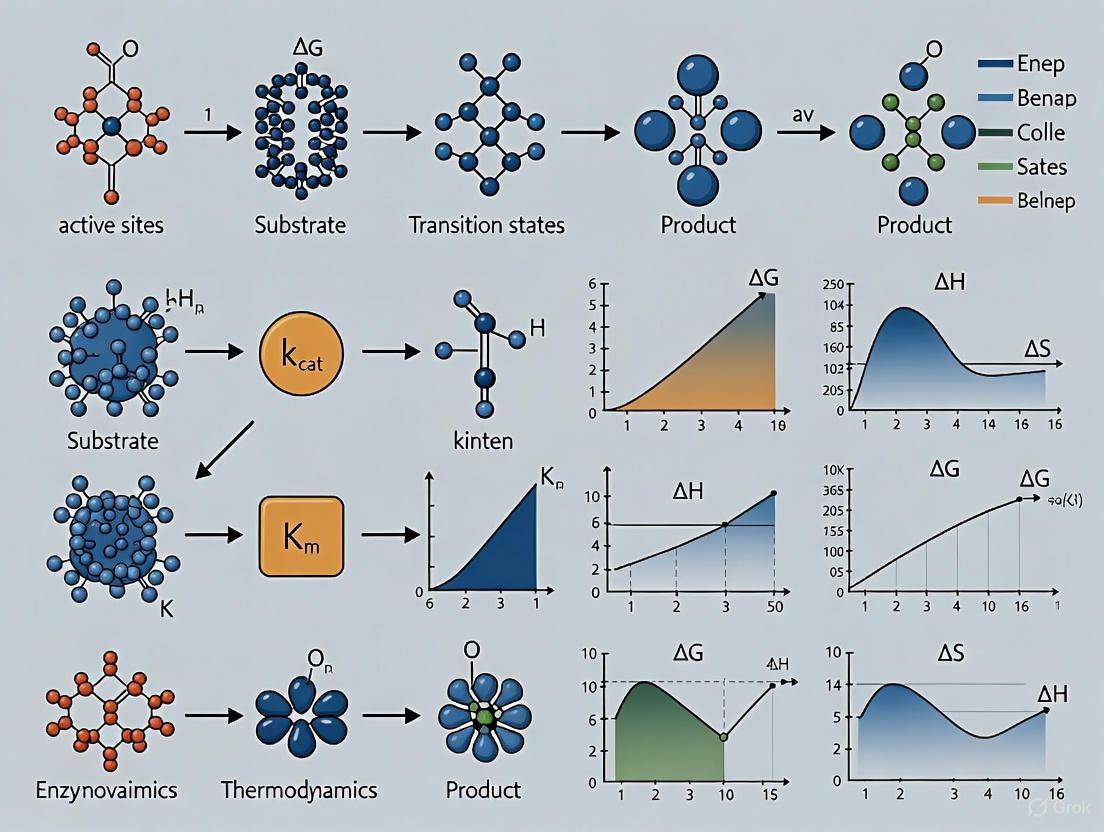

The Core Principles: Unraveling the Link Between Enzyme Kinetics and Thermodynamics

Enzymes serve as biological catalysts that profoundly accelerate biochemical reaction rates by lowering the activation energy barrier, while rigorously maintaining the thermodynamic equilibrium between substrates and products. This whitepaper examines the fundamental principles governing enzyme catalysis through the integrated lenses of kinetics and thermodynamics, synthesizing classical models with contemporary research findings. We explore how enzymes achieve remarkable rate enhancements exceeding 10^17-fold through transition state stabilization, precise substrate orientation, and covalent catalysis mechanisms, without altering reaction equilibria. Recent advances quantifying the relationship between thermodynamic driving forces and enzyme efficiency reveal critical implications for metabolic engineering and drug development. This analysis provides researchers with both theoretical frameworks and practical methodologies for investigating enzyme function, emphasizing the inseparable connection between catalytic mechanisms and cellular resource allocation.

Enzymes represent nature's primary catalytic machinery, accelerating biochemical reactions by factors of 10^6 to 10^17 compared to uncatalyzed rates while operating under mild physiological conditions [1]. These protein catalysts achieve extraordinary rate enhancements through selective stabilization of high-energy transition states, thereby reducing the activation energy barrier that substrates must overcome to form products [2]. A fundamental characteristic of enzymatic catalysis is that while kinetics are dramatically accelerated, the thermodynamic equilibrium position remains unchanged—enzymes equally accelerate both forward and reverse reactions according to the principle of microscopic reversibility [1].

The energy landscape of enzyme-catalyzed reactions reveals the physical basis for catalytic efficiency. In uncatalyzed reactions, substrates must overcome a significant energy barrier (activation energy) to reach the transition state before proceeding to products. Enzymes provide an alternative reaction pathway with a substantially lower energy barrier through multiple coordinated mechanisms including approximation, orientation, covalent catalysis, and acid-base catalysis [1]. Current research continues to elucidate how enzyme structure dictates function, with recent evidence demonstrating that thermodynamic parameters fundamentally constrain catalytic performance and cellular resource allocation [3] [4]. These findings have profound implications for understanding metabolic evolution and designing therapeutic enzyme inhibitors.

Fundamental Thermodynamic and Kinetic Frameworks

Thermodynamic Foundations of Enzyme Catalysis

Biochemical thermodynamics governs enzyme-catalyzed reactions through transformed Gibbs energy (G'), which incorporates pH as an independent variable alongside temperature and ionic strength [5]. This framework reveals that while enzymes dramatically accelerate reaction rates, they do not alter the overall equilibrium constant (K_eq) between substrates and products [6] [1]. The equilibrium position remains determined solely by the free energy difference (ΔG) between reactants and products, following the fundamental laws of thermodynamics.

The energy diagram below illustrates the critical relationship between activation energy and reaction rate in enzyme-catalyzed systems:

Energy Diagram Title: Enzyme Reduction of Activation Energy

This diagram visualizes the central principle of enzyme catalysis: enzymes lower the activation energy barrier (Ea) without changing the overall free energy (ΔG) of the reaction. The enzyme-catalyzed pathway (blue) demonstrates a significantly reduced energy barrier compared to the uncatalyzed reaction (red), enabling more substrate molecules to overcome this barrier per unit time while maintaining identical starting and ending energy states.

Michaelis-Menten Kinetics and Steady-State Assumptions

The Michaelis-Menten model provides the fundamental framework for quantifying enzyme kinetics through the relationship between substrate concentration and reaction velocity [7] [8]. This model introduces two critical kinetic parameters: Vmax (maximum reaction rate when enzyme active sites are saturated) and Km (Michaelis constant, representing the substrate concentration at half V_max) [8]. The basic model assumes the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex (ES) that subsequently converts to product:

Mechanism Title: Enzyme Catalysis Reaction Pathway

The Michaelis-Menten equation, ( v0 = \frac{V{max}[S]}{Km + [S]} ), mathematically describes the hyperbolic relationship between initial reaction velocity (v₀) and substrate concentration ([S]) [8]. Derivation of this equation employs either the rapid-equilibrium assumption (where E, S, and ES maintain equilibrium) or the more general steady-state assumption (where [ES] remains constant over time) [6]. The Km value provides insight into enzyme-substrate affinity, with lower Km values indicating higher affinity, while kcat (turnover number) represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per active site per unit time [8].

Table 1: Fundamental Kinetic Parameters in Enzyme Catalysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis Constant | K_m | Substrate concentration at ½ V_max | Measure of enzyme-substrate affinity | M (mol/L) |

| Maximum Velocity | V_max | Maximum reaction rate at enzyme saturation | Measure of catalytic efficiency | M/s |

| Turnover Number | k_cat | Number of reactions per active site per second | intrinsic catalytic efficiency | s⁻¹ |

| Specificity Constant | kcat/Km | Measure of catalytic efficiency at low [S] | Determines enzyme selectivity for competing substrates | M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

Experimental Methodologies in Enzyme Kinetics

Quantitative Enzyme Assay Protocols

Accurate determination of enzyme kinetic parameters requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and precise measurement of initial reaction rates. The following protocol outlines a standardized approach for obtaining Michaelis-Menten parameters:

Initial Rate Determination Protocol:

- Reaction Mixture Preparation: Prepare a master reaction buffer containing appropriate pH buffer, essential cofactors, and salts. Maintain constant temperature using a circulating water bath (±0.1°C).

- Enzyme Dilution Series: Prepare serial dilutions of purified enzyme in stabilization buffer (often containing BSA or glycerol). Keep on ice to maintain activity.

- Substrate Concentration Series: Prepare substrate solutions spanning concentrations from 0.2× to 5× the estimated K_m value.

- Reaction Initiation: Start reactions by adding enzyme to substrate solution (final volume 0.1-1.0 mL). Mix rapidly and thoroughly.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Monitor product formation or substrate disappearance continuously for the first 5-10% of reaction completion. Use appropriate detection methods (spectrophotometry, fluorimetry, radioactivity, etc.).

- Data Collection: Record initial linear rate for each substrate concentration. Perform measurements in triplicate with appropriate controls (no enzyme, no substrate).

- Parameter Calculation: Fit [S] vs. v₀ data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression to determine Km and Vmax values.

For continuous assays, integrated rate equations can be applied to time-course data, particularly for reactions where substrate depletion becomes significant [6]. Recent advances incorporate computational simulations to model enzyme-catalyzed reactions and visualize progress curves under varying conditions, enabling more accurate parameter estimation [6].

Thermodynamic Profiling of Enzyme Reactions

Quantifying the thermodynamic constraints on enzyme catalysis requires determination of Gibbs free energy changes (ΔG) for individual reaction steps. The following methodology enables comprehensive thermodynamic profiling:

Thermodynamic Parameter Determination:

- Equilibrium Constant Measurement: Allow enzyme-catalyzed reactions to proceed to completion under defined conditions. Measure final concentrations of substrates and products using HPLC, NMR, or enzymatic coupling assays.

- Reaction Quench-Flow Techniques: For rapid reactions, use stopped-flow or quench-flow apparatus to measure reaction progress on millisecond timescales.

- Calorimetric Analysis: Employ isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to directly measure enthalpy changes (ΔH) during substrate binding and catalysis.

- Isotope Tracing Studies: Use ¹³C or ²H metabolic flux analysis (MFA) combined with computational estimation to determine in vivo ΔG values for metabolic reactions [3].

- Data Integration: Combine equilibrium concentrations with calorimetric data to calculate standard transformed Gibbs energies (ΔG'°), accounting for experimental pH and ionic strength [5].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Kinetics Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Buffering Systems | Tris-HCl, HEPES, Phosphate buffers | Maintain constant pH optimal for enzyme activity during assays |

| Cofactor Solutions | NAD+/NADH, ATP/Mg²+, Coenzyme A | Provide essential cosubstrates and cofactors for enzymatic reactions |

| Stabilizing Agents | Glycerol, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Maintain enzyme stability and prevent inactivation during assays |

| Detection Reagents | Chromogenic substrates, Luciferin/luciferase, Fluorescent dyes | Enable quantification of reaction rates through signal generation |

| Proteomic Standards | Isotopically labeled reference peptides (AQUA) | Allow absolute quantification of enzyme concentrations via mass spectrometry [3] |

Current Research and Advanced Concepts

Thermodynamic Constraints on Cellular Enzyme Burden

Recent research has quantified how thermodynamic parameters influence the metabolic efficiency of enzyme systems in living cells. A 2025 study integrating absolute enzyme concentrations with in vivo metabolic fluxes demonstrated that thermodynamic driving force directly determines cellular enzyme burden [3]. This groundbreaking work compared three bacterial species utilizing distinct glycolytic pathways with varying thermodynamic profiles:

Table 3: Thermodynamic Efficiency of Glycolytic Pathways in Bacteria

| Organism | Glycolytic Pathway | Thermodynamic Favorability | Relative Enzyme Protein Required | Key Thermodynamic Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zymomonas mobilis | Entner-Doudoroff (ED) | Highest | 1× (reference) | Strong thermodynamic driving forces; minimal reverse fluxes |

| Escherichia coli | Embden-Meyerhof-Parnas (EMP) | Intermediate | ~2-3× | Moderate thermodynamic constraints |

| Clostridium thermocellum | PP_i-dependent EMP | Lowest | ~4× | High enzyme demand due to near-equilibrium reactions |

The study revealed that the highly favorable ED pathway in Z. mobilis requires only one-fourth the enzymatic protein to sustain equivalent flux compared to the thermodynamically constrained PP_i-dependent glycolytic pathway in C. thermocellum [3]. This provides direct experimental evidence that reactions operating near equilibrium (with nearly equal forward and reverse fluxes) incur substantially higher enzyme costs due to inefficient enzyme utilization. These findings have profound implications for metabolic engineering, suggesting that pathway thermodynamics should be optimized to minimize protein burden while maintaining desired flux.

Scaling Relationships Between Enzyme Kinetics and Energy Dissipation

Emerging research explores fundamental connections between enzyme kinetic parameters and thermodynamic dissipation through power-law scaling relationships. A 2025 analysis of 75 enzyme-catalyzed reactions demonstrated scale-invariant dissipation underlying enzyme catalytic performance [4]. The study identified a log-log power law relationship between dissipation (as quantified in irreversible thermodynamics) and enzyme efficiency (kcat/Km):

[ \log{10}\left(\frac{\text{dissipation}}{RT}\right) = a + b \cdot \log{10}\left(\frac{k{cat}}{KM}\right) ]

This relationship connects physical parameters from irreversible thermodynamics with biological performance parameters, supporting the evolution-coupling hypothesis that links physical and biological evolutionary processes [4]. The research further distinguished between "specialist" enzymes (optimized for specific substrates with high kcat/Km values) and "generalist" enzymes (with broader substrate range but lower catalytic efficiency), revealing different scaling exponents between these categories.

Mechanistic Convergence in Functionally Analogous Enzymes

Quantitative analysis of functionally analogous enzymes (non-homologous enzymes catalyzing similar reactions) reveals unexpected diversity in catalytic mechanisms. A comprehensive study of 95 enzyme pairs with identical Enzyme Commission (EC) classifications found that only 44% showed significant similarity in overall bond changes during catalysis [9]. Even more strikingly, only 33% of these pairs had converged on similar stepwise mechanisms despite catalyzing statistically similar overall reactions.

The workflow below illustrates the experimental approach for comparing catalytic mechanisms across enzyme families:

Analysis Title: Enzyme Mechanism Comparison Workflow

This research demonstrates that the EC classification system often fails to capture significant mechanistic differences between enzymes and suggests that quantitative measurement of bond changes could refine enzyme classification and functional annotation [9]. These findings are particularly relevant for drug development, where understanding mechanistic differences between homologous human and pathogen enzymes can enable selective inhibitor design.

Applications in Drug Development and Metabolic Engineering

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms and Therapeutic Targeting

Understanding enzyme catalytic mechanisms provides the foundation for rational drug design targeting pathogenic enzymes. Different inhibition modalities produce distinct effects on kinetic parameters, as summarized below:

Table 4: Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms and Kinetic Effects

| Inhibition Type | Mechanism of Action | Effect on K_m | Effect on V_max | Therapeutic Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive | Inhibitor binds active site, competing with substrate | Increases | No change | Statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors) |

| Non-competitive | Inhibitor binds allosteric site, affecting catalysis | No change | Decreases | Protease inhibitors for HIV treatment |

| Uncompetitive | Inhibitor binds only to enzyme-substrate complex | Decreases | Decreases | Methotrexate (dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor) |

| Mixed | Inhibitor binds both enzyme and ES complex with different affinities | Increases or decreases | Decreases | Various kinase inhibitors |

The quantitative analysis of inhibitor effects typically employs Lineweaver-Burk plots (1/v vs. 1/[S]) to distinguish inhibition mechanisms through characteristic pattern changes [8]. Modern drug discovery integrates these classical kinetic approaches with structural biology and computational modeling to design highly specific therapeutic agents.

Engineering Enzymes for Industrial Applications

Recent advances in understanding enzyme catalysis enable engineering of customized enzymes for industrial processes. The successful elucidation of the acetyl-CoA synthase (ACS) mechanism through synthetic model systems illustrates this approach [10]. Researchers created a functional synthetic model using a specialized ligand (iPr₃tacn) that cages nickel atoms, slowing reaction rates sufficiently to characterize previously elusive intermediates, including the rare Ni(methyl)(CO) species [10].

This mechanistic understanding facilitates the development of nickel-based catalysts for carbon capture and utilization, potentially replacing expensive precious metals (e.g., rhodium in Monsanto's acetic acid process) with earth-abundant alternatives [10]. Similarly, insights from thermodynamic profiling of native metabolic pathways guide the engineering of synthetic pathways with reduced enzyme burden and enhanced flux capacity [3].

Enzymes exemplify nature's mastery of catalytic principles, achieving extraordinary rate enhancements through transition state stabilization while respecting fundamental thermodynamic constraints. The integrated perspective presented in this whitepaper demonstrates that enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics are inseparable determinants of biological function, from molecular mechanisms to cellular resource allocation. Current research continues to reveal unexpected relationships between energy dissipation, catalytic efficiency, and evolutionary adaptation, providing new conceptual frameworks for understanding enzyme function.

The quantitative methodologies and experimental approaches detailed herein provide researchers with powerful tools for investigating enzyme mechanisms, inhibiting pathogenic enzymes, and engineering novel catalysts. As thermodynamic profiling and mechanistic analysis techniques continue to advance, they will undoubtedly yield new insights into nature's catalytic strategies and enable innovative applications in therapeutics, biotechnology, and sustainable chemistry.

The Michaelis-Menten equation stands as a cornerstone of enzymology, providing a quantitative framework to describe the kinetics of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. This technical guide deconstructs the fundamental parameters of the equation—kcat, KM, and Vmax—within the context of modern enzyme thermodynamics and kinetics research. We explore the intricate relationship between these kinetic constants, the thermodynamic principles governing their optimization, and their critical importance in drug development and biotechnology. By integrating theoretical frameworks with practical experimental protocols and advanced analysis techniques, this review serves as a comprehensive resource for researchers and scientists seeking to deepen their understanding of enzyme function and catalytic efficiency.

Enzyme kinetics is the study of the rates of enzyme-catalyzed reactions and the conditions that affect them. Enzymes are biological catalysts that increase the rate of chemical reactions without being consumed or permanently altered in the process. They achieve this remarkable efficiency by providing an alternative reaction pathway with a lower activation energy (Ea)—the minimum energy input required for a reaction to proceed [8]. The catalytic activity of enzymes is essential for virtually all biological processes, as without them, many biochemical reactions would proceed too slowly to sustain life [8].

The early 20th century witnessed foundational developments in enzyme kinetics, culminating in 1913 when Leonor Michaelis and Maud Menten proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics that remains fundamental to the field today [11] [12]. Their work built upon earlier observations by Victor Henri, who recognized that enzyme reactions involved binding interactions between enzymes and substrates [12]. Michaelis and Menten investigated the kinetics of invertase, an enzyme that catalyzes the hydrolysis of sucrose into glucose and fructose, and developed a mathematical model that could explain the characteristic dependence of reaction velocity on substrate concentration [12]. This model, now known as Michaelis-Menten kinetics, has proven applicable not only to enzyme-substrate interactions but also to antigen-antibody binding, DNA-DNA hybridization, protein-protein interactions, and various other biochemical processes [12].

The Michaelis-Menten Model and Equation

Fundamental Reaction Mechanism

The Michaelis-Menten model describes a minimal enzyme-catalyzed reaction involving the transformation of a single substrate into a single product. The reaction scheme proceeds through the formation of an enzyme-substrate complex, which then decomposes to yield the product and regenerate the free enzyme. The complete mechanism can be represented as follows [12]:

E + S ⇌ ES → E + P

Where E represents the free enzyme, S is the substrate, ES is the enzyme-substrate complex, and P is the product. The rate constants k₁ and k₋₁ govern the forward and reverse reactions for the formation of the ES complex, while k₂ (often denoted as kcat) represents the catalytic rate constant for the conversion of the complex to product and free enzyme [12].

The Michaelis-Menten Equation

Through mathematical derivation based on either the rapid equilibrium assumption or the steady-state approximation, the Michaelis-Menten equation expresses the initial reaction velocity (v) as a function of substrate concentration [S]:

v = (Vmax × [S]) / (KM + [S]) [8] [12]

Where:

- v is the initial reaction velocity

- Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity

- [S] is the substrate concentration

- KM is the Michaelis constant

This equation describes a hyperbolic relationship between substrate concentration and reaction rate, which can be graphically represented in a Michaelis-Menten plot [11]. At low substrate concentrations ([S] << KM), the reaction rate increases approximately linearly with substrate concentration (first-order kinetics). At high substrate concentrations ([S] >> KM), the rate approaches Vmax asymptotically and becomes independent of substrate concentration (zero-order kinetics) [8] [12].

Figure 1: Michaelis-Menten Enzyme Reaction Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the fundamental steps in enzyme catalysis according to the Michaelis-Menten model, showing the relationship between enzyme (E), substrate (S), enzyme-substrate complex (ES), and product (P), along with their respective rate constants.

Deconstructing the Kinetic Parameters

Vmax: Maximum Reaction Velocity

Vmax represents the maximum rate of an enzyme-catalyzed reaction when all available enzyme active sites are saturated with substrate [11] [13]. Conceptually, it reflects the enzyme's "top speed" under optimal substrate conditions [13]. When every active site is occupied, the enzyme operates at full capacity, and adding more substrate cannot increase the reaction rate further [11]. Mathematically, Vmax is defined as:

Vmax = kcat × [E]₀

Where [E]₀ is the total enzyme concentration and kcat is the catalytic rate constant (turnover number) [12]. The value of Vmax is dependent on enzyme concentration and provides insight into the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme when substrate is not limiting.

KM: Michaelis Constant

The Michaelis constant (KM) is defined as the substrate concentration at which the reaction rate is half of Vmax [11] [8]. It is a composite constant derived from the individual rate constants of the enzymatic reaction:

KM = (k₋₁ + kcat)/k₁ [12]

KM serves as an inverse measure of the enzyme's affinity for its substrate—a lower KM value indicates higher substrate affinity, meaning the enzyme requires a lower substrate concentration to reach half of its maximum velocity [11] [8]. This relationship makes KM a crucial parameter for understanding how efficiently an enzyme can function at physiological substrate concentrations.

kcat: Catalytic Constant (Turnover Number)

The kcat value, also known as the turnover number, represents the maximum number of substrate molecules converted to product per enzyme active site per unit time [11]. It is a first-order rate constant with units of reciprocal time (s⁻¹) and reflects the intrinsic catalytic efficiency of the enzyme when saturated with substrate [12]. kcat defines the rate-limiting step of the catalytic cycle, typically the conversion of ES complex to E + P [8]. Higher kcat values indicate more efficient enzymes capable of processing more substrate molecules per second.

Catalytic Efficiency: kcat/KM

The specificity constant, expressed as kcat/KM, is a second-order rate constant that measures the overall catalytic efficiency of an enzyme toward a particular substrate [11] [12]. It incorporates both binding affinity (KM) and catalytic rate (kcat) into a single parameter. The higher the kcat/KM value, the more efficient the enzyme is at converting substrate to product, particularly at low substrate concentrations [12]. This parameter becomes especially important when comparing an enzyme's activity toward different substrates or when evaluating the effectiveness of enzyme variants in protein engineering [12].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation | Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum Velocity | Vmax | Maximum reaction rate at enzyme saturation | Enzyme's "top speed" at full capacity | concentration/time |

| Michaelis Constant | KM | Substrate concentration at Vmax/2 | Inverse measure of substrate affinity | concentration |

| Turnover Number | kcat | Number of substrate molecules turned over per site per second | Intrinsic catalytic efficiency | time⁻¹ |

| Catalytic Efficiency | kcat/KM | Ratio of catalytic constant to Michaelis constant | Overall efficiency for a specific substrate | concentration⁻¹·time⁻¹ |

Table 2: Representative Enzyme Kinetic Parameters [12]

| Enzyme | KM (M) | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chymotrypsin | 1.5 × 10⁻² | 0.14 | 9.3 |

| Pepsin | 3.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.50 | 1.7 × 10³ |

| tRNA synthetase | 9.0 × 10⁻⁴ | 7.6 | 8.4 × 10³ |

| Ribonuclease | 7.9 × 10⁻³ | 7.9 × 10² | 1.0 × 10⁵ |

| Carbonic anhydrase | 2.6 × 10⁻² | 4.0 × 10⁵ | 1.5 × 10⁷ |

| Fumarase | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 8.0 × 10² | 1.6 × 10⁸ |

Thermodynamic Principles and Relationship to Kinetic Parameters

Thermodynamic Basis of Enzyme Catalysis

Enzymes function by lowering the activation energy (Ea) required for a reaction to proceed, without altering the overall equilibrium or thermodynamics of the reaction [8] [14]. They achieve this by stabilizing the transition state—the high-energy intermediate through which the reaction must pass [8]. The active site of an enzyme is complementary not to the substrate itself, but to the transition state, which has higher free energy than both the substrate and product [8]. This transition state stabilization reduces the activation energy barrier, allowing more substrate molecules to reach the transition state and be converted to product within a given time frame [8].

Two principal models describe how enzymes interact with their substrates. The lock-and-key model proposes that the enzyme's active site is pre-formed to perfectly fit the substrate [8]. The more widely accepted induced-fit model suggests that the enzyme undergoes conformational changes upon substrate binding to optimize its fit with the transition state [8] [14]. This conformational adjustment better orients catalytic residues and the substrate, thereby enhancing transition state stabilization and facilitating the chemical transformation [14].

Thermodynamic Optimization of Kinetic Parameters

Recent research has revealed fundamental thermodynamic principles governing the optimization of enzymatic activity. A key finding demonstrates that tuning the Michaelis constant (KM) to match the physiological substrate concentration ([S]) enhances enzymatic activity [15]. This optimization principle (KM = [S]) emerges from thermodynamic constraints under the assumption that thermodynamically favorable reactions have higher rate constants, with the total driving force being fixed [15].

This relationship can be understood through thermodynamic modeling that incorporates the Brønsted (Bell)-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) relationship, which models activation barriers as functions of driving force [15]. The BEP relationship suggests that thermodynamically unfavorable elementary reactions have larger activation barriers [15]. When applied to enzyme kinetics, this principle reveals that the distribution of the total free energy change (ΔGT) between the initial enzyme-substrate binding step (ΔG1) and the subsequent catalytic step (ΔG2) determines the overall catalytic efficiency [15]. Bioinformatic analysis of approximately 1000 wild-type enzymes confirms that KM values and in vivo substrate concentrations are consistent across diverse enzymes, suggesting that natural selection follows the principle of KM = [S] [15].

Figure 2: Energy Diagram Comparing Catalyzed and Uncatalyzed Reactions. This diagram illustrates how enzymes lower the activation energy (ΔG‡) barrier without changing the overall free energy (ΔG) of the reaction. The blue line represents the uncatalyzed pathway, while the red line shows the enzyme-catalyzed pathway with a lower energy transition state.

Experimental Determination of Kinetic Parameters

Standard Kinetic Assay Protocol

The reliable determination of Michaelis-Menten parameters requires carefully controlled experimental conditions and rigorous methodology. A comprehensive enzyme characterization pipeline typically includes the following steps [16]:

- Protein Expression and Purification: Produce soluble, active enzyme at sufficient yield and purity for kinetic assays.

- Pre-test Colorimetric Assay: Perform rapid, high-throughput screening for enzymatic activity using appropriate indicators.

- Fluoride Ion Measurement: For dehalogenases and similar enzymes, directly measure released ions to confirm reaction quantitatively.

- Linear Phase Determination: Identify the time window where product formation is linear and the enzyme concentration range where initial velocity (V₀) is proportional to enzyme concentration ([E]).

- Michaelis-Menten Kinetics: Measure initial velocities at multiple substrate concentrations and fit data to the Michaelis-Menten equation using nonlinear regression.

For the formal kinetic characterization, researchers should use enzyme at a chosen concentration ([E]) with a substrate series (e.g., 0.1-20 mM; recommended points: 0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 15 mM) in triplicate assays [16]. Initial rates should be measured within the previously determined linear time window. The resulting V₀ versus [S] data are then fitted to the Michaelis-Menten equation to obtain KM and Vmax, from which kcat can be calculated as kcat = Vmax/[E]total [16].

Advanced Methodologies

While traditional spectrophotometric methods remain widely used, several advanced techniques offer enhanced capabilities for kinetic parameter determination:

Real-time Quantitative NMR (qNMR): This approach enables following enzymatic conversion of substrate to product in real-time by continuous collection of spectra [17]. When combined with progress curve analysis and the Lambert-W function (a closed-form solution to the time-dependent substrate/product kinetics), qNMR can estimate KM and Vmax from a single experiment [17]. This method has been successfully applied to studies of acetylcholinesterase, β-Galactosidase, and invertase [17].

Orthogonal Validation Methods:

- Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS): Provides chemical identification of substrate depletion and specific degradation products to confirm reaction pathways [16].

- Stopped-flow Spectrophotometry: Allows measurement of very fast initial rates for rapid enzymatic reactions [16].

- ¹⁹F-NMR: Enables direct observation of fluorine-containing species and structural characterization of transformation products [16].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Kinetics Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Purified Enzyme | Catalytic component of study | Must be soluble, active, and at sufficient concentration/purity |

| Substrate Series | Variable concentration points for kinetic analysis | Should cover range below and above expected KM |

| Buffer Components | Maintain optimal pH for enzymatic activity | Choice depends on enzyme pH optimum; Tris, phosphate common |

| Colorimetric Probes (e.g., phenol red) | High-throughput activity screening | pH-sensitive indicators for reactions liberating acids/bases |

| Ion-Selective Electrode | Direct measurement of released ions | Requires calibration with standard solutions |

| TISAB Solution | Stabilizes ionic strength, complexes interfering metals | Essential for fluoride ion measurement assays |

| LC-MS/MS System | Orthogonal validation of substrate depletion and product formation | Requires reference standards for quantification |

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Proper statistical analysis is crucial for reliable kinetic parameter estimation. Researchers should:

- Perform experiments in triplicate to assess reproducibility

- Report mean ± standard deviation (n ≥ 3)

- Evaluate residuals and confidence intervals from nonlinear fits

- Include appropriate controls: substrate alone, enzyme blanks, spiked recovery samples

- Use specialized software (e.g., GraphPad Prism) for robust curve fitting [16]

Success in kinetic characterization is indicated by reproduction of literature values for well-characterized enzymes within approximately 2-fold, with confidence intervals excluding zero and coefficient of variation (CV) < 20% [16].

Figure 3: Experimental Workflow for Enzyme Kinetic Characterization. This diagram outlines the key stages in determining Michaelis-Menten parameters, from initial preparation through data collection to final analysis and validation.

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

Enzyme Inhibition Mechanisms in Pharmaceutical Development

Understanding Michaelis-Menten parameters is crucial in drug discovery, particularly in the design and characterization of enzyme inhibitors. Different types of inhibition display distinct effects on KM and Vmax, enabling researchers to elucidate inhibitor mechanisms [13]:

Competitive Inhibition: Inhibitors compete with the substrate for the active site, increasing the apparent KM value without affecting Vmax [13]. This occurs because sufficient substrate can outcompete the inhibitor at high concentrations. Competitive inhibition is analogous to "musical chairs" where substrate and inhibitor vie for the same binding site [13].

Noncompetitive Inhibition: Inhibitors bind allosterically to both free enzyme and the ES complex, reducing Vmax without altering KM [13]. This type of inhibition decreases the enzyme's catalytic capacity while maintaining its substrate affinity.

Uncompetitive Inhibition: Inhibitors bind exclusively to the ES complex, decreasing both Vmax and KM [13]. This mechanism "locks" the substrate in place, effectively increasing apparent affinity while reducing catalytic turnover.

Mixed Inhibition: Inhibitors bind to both free enzyme and ES complex but with different affinities, decreasing Vmax while either increasing or decreasing KM depending on binding preferences [13].

Rational Enzyme Engineering and Optimization

The principles of Michaelis-Menten kinetics guide enzyme engineering efforts in biotechnology. By understanding the relationship between kinetic parameters and catalytic efficiency, researchers can develop strategies to optimize enzymes for industrial processes. The thermodynamic principle that tuning KM to match operational substrate concentrations enhances activity provides a concrete guideline for enzyme optimization [15]. This approach is particularly valuable in metabolic engineering, bioremediation, and the development of biocatalysts for chemical synthesis [15].

In applied contexts, enzyme kinetic characterization enables data-driven decisions about enzyme immobilization, bioreactor design, and process optimization [16]. For example, enzymes with high kcat and low KM values are prioritized for immobilization and reactor tests with a focus on stability, while those with low kcat but low KM may benefit from active-site mutations to improve catalysis [16].

The Michaelis-Menten equation and its parameters—kcat, KM, and Vmax—provide a fundamental framework for understanding enzyme catalysis that remains as relevant today as when it was first introduced over a century ago. Through continued refinement of experimental methods and deeper thermodynamic insights, researchers have expanded the application of these kinetic principles from basic enzymology to drug discovery, biotechnology, and systems biology. The recent recognition that natural enzymes appear optimized such that KM matches physiological substrate concentrations offers a powerful design principle for engineering novel catalysts [15]. As new analytical techniques emerge and our understanding of enzyme thermodynamics deepens, the nuanced interpretation of these kinetic parameters will continue to drive innovations across biochemical research and therapeutic development.

The derivation of the Michaelis-Menten equation, a cornerstone of enzymology, rests upon critical simplifying assumptions that make the complex mathematics of enzyme catalysis tractable. The two primary frameworks—the rapid equilibrium assumption and the more general steady-state assumption—represent fundamentally different approaches to modeling enzyme behavior. While both yield the familiar hyperbolic equation relating substrate concentration to reaction velocity, their underlying mechanisms and conditions for validity differ significantly. Understanding these distinctions is not merely academic; it directly impacts experimental design, parameter estimation accuracy, and model selection in pharmaceutical development and metabolic engineering.

For over a century, the Michaelis-Menten equation has provided the principal framework for quantifying enzyme activity through parameters ( KM ) (Michaelis constant) and ( k{cat} ) (catalytic constant). The canonical form, ( v = \frac{V{max}[S]}{KM + [S]} ), describes the dependence of reaction velocity (( v )) on substrate concentration (( [S] )) [18] [15]. However, this equation can be derived via two distinct logical pathways, each with specific constraints. The rapid equilibrium (or quasi-equilibrium) assumption posits that the initial substrate binding step (E + S ⇌ ES) reaches equilibrium rapidly compared to the subsequent catalytic step (ES → E + P) [6]. In contrast, the steady-state assumption, developed by Briggs and Haldane, proposes that the concentration of the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) remains constant over time, regardless of whether the binding step has reached equilibrium [18]. This distinction becomes critically important when moving beyond idealized in vitro conditions to model enzyme behavior in complex biological systems like intracellular environments, where enzyme concentrations can approach or exceed ( K_M ) values.

Theoretical Foundations and Mathematical Derivations

The Rapid Equilibrium Assumption

Under the rapid equilibrium assumption, the enzyme (E), substrate (S), and enzyme-substrate complex (ES) are considered to be in instantaneous equilibrium. The dissociation constant for the ES complex, ( KS ), is defined as ( KS = \frac{[E][S]}{[ES]} ). Using the enzyme conservation equation (( [E]T = [E] + [ES] )), one can solve for [ES], yielding ( [ES] = \frac{[E]T[S]}{KS + [S]} ) [6]. Since the reaction velocity is given by ( v = k{cat}[ES] ), substitution produces the familiar Michaelis-Menten equation: ( v = \frac{k{cat}[E]T[S]}{KS + [S]} = \frac{V{max}[S]}{KS + [S]} ). In this derivation, the Michaelis constant ( KM ) is literally identical to the dissociation constant ( K_S ), providing a direct thermodynamic measure of substrate binding affinity. This derivation is mathematically straightforward but relies on the potentially restrictive assumption that the catalytic step is rate-limiting and sufficiently slow to allow the binding equilibrium to be maintained throughout the reaction.

The Steady-State Assumption

The steady-state approach, formalized by Briggs and Haldane, relaxes the requirement for a pre-equilibrium. It instead assumes that shortly after the reaction initiates, the concentration of the ES complex becomes constant, so ( \frac{d[ES]}{dt} = 0 ) [18]. For the basic mechanism ( E + S \overset{kf}{\underset{kr}{\rightleftharpoons}} ES \overset{k{cat}}{\rightarrow} E + P ), applying the steady-state condition to [ES] leads to the expression ( KM = \frac{kr + k{cat}}{kf} ). The resulting equation is identical in form to the rapid equilibrium derivation: ( v = \frac{k{cat}[E]T[S]}{KM + [S]} ). However, the definition of ( KM ) is now a kinetic, not a thermodynamic, constant. It reflects the combined processes of dissociation and catalysis. Only when ( k{cat} \ll kr ) does ( KM ) approximate the true dissociation constant ( K_S ). This makes the steady-state approximation applicable to a wider range of enzymes, particularly those where the chemical transformation step is not unequivocally rate-limiting.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Assumptions and Parameter Definitions

| Feature | Rapid Equilibrium Assumption | Steady-State Assumption |

|---|---|---|

| Core Premise | E + S ⇌ ES equilibrium established rapidly | [ES] constant after reaction initiation |

| Rate-Limiting Step | Catalytic step (ES → E + P) | Not specified; can be any step |

| Definition of ( K_M ) | ( KM = KS = \frac{kr}{kf} ) (Dissociation constant) | ( KM = \frac{kr + k{cat}}{kf} ) (Kinetic constant) |

| Mathematical Complexity | Simpler derivation | More complex derivation |

| Range of Validity | Narrower; requires ( k{cat} \ll kr ) | Broader; applicable when ( \frac{[E]T}{[S]T + K_M} \ll 1 ) [18] |

| Interpretation of ( K_M ) | Pure measure of substrate binding affinity | Apparent affinity influenced by binding and catalysis |

Validity Conditions and Modern Extensions

The validity of the standard Michaelis-Menten equation (derived from either assumption) is formally bounded by the condition ( \frac{[E]T}{KM + [S]T} \ll 1 ) [18]. Violations occur in vivo, where high enzyme concentrations are common, leading to significant underestimation of ( KM ) and ( k{cat} ) if the classical model is used. To address this, the total quasi-steady-state approximation (tQSSA) was developed. The tQSSA model uses a more complex rate equation that remains accurate even when enzyme concentration is not negligible compared to substrate and ( KM ) [18]. This model is particularly valuable for analyzing progress curve data and for predicting in vivo enzyme activity from in vitro parameters. Bayesian inference methods based on the tQSSA model have been shown to provide unbiased estimates of kinetic parameters for diverse enzymes like chymotrypsin, fumarase, and urease, regardless of the initial enzyme-to-substrate ratio [18].

Diagram 1: Kinetic Model Selection Workflow

Experimental Protocols and Data Analysis

Progress Curve Assay and Parameter Estimation

The progress curve assay, which fits the entire time-course of product formation, uses data more efficiently than the initial velocity assay and requires fewer experiments to estimate parameters [18]. The protocol involves:

- Reaction Initiation: Combine enzyme and substrate at a defined temperature and pH, ensuring rapid mixing. The reaction mixture should include all necessary cofactors and be buffered appropriately.

- Time-Course Monitoring: Continuously monitor the accumulation of product (or depletion of substrate) using a suitable method (e.g., spectrophotometry, fluorimetry, HPLC). Data points should be densely collected, especially in the early phase of the reaction.

- Data Fitting with Integrated Rate Equations: Fit the progress curve data to the integrated form of the chosen kinetic model, not just the initial rates.

- Computational Parameter Estimation: Use nonlinear regression algorithms (e.g., in R, Python, or specialized software like NONMEM) to obtain best-fit estimates for ( k{cat} ) and ( KM ). Bayesian inference approaches are particularly effective as they provide probability distributions for the parameters, quantifying estimation uncertainty [18] [19].

Comparing Estimation Methods

Various statistical methods exist for estimating ( V{max} ) and ( KM ) from kinetic data. Traditional linearization methods (e.g., Lineweaver-Burk, Eadie-Hofstee) are simple but often violate the assumptions of linear regression, such as homoscedasticity of errors. Modern nonlinear regression techniques applied directly to the untransformed data or to the full progress curve provide superior accuracy and precision [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Kinetic Parameter Estimation Methods

| Estimation Method | Description | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lineweaver-Burk (LB) | Linear plot of ( 1/v ) vs. ( 1/[S] ) | Simple visualization of ( KM ) and ( V{max} ) | Prone to error propagation; poor statistical properties [19] |

| Eadie-Hofstee (EH) | Linear plot of ( v ) vs. ( v/[S] ) | Better error distribution than LB | Still less reliable than nonlinear methods [19] |

| Nonlinear Regression (NL) | Direct fit of ( v ) vs. ( [S] ) to Michaelis-Menten equation | Accurate; honors error structure of data | Requires computational software |

| Progress Curve (NM) | Nonlinear fit of ( [S] ) or ( [P] ) vs. time data | Uses data more efficiently; fewer experiments required | Requires accurate initial conditions and model [18] [19] |

Diagram 2: Generalized Reversible Enzyme Mechanism

Successful experimental analysis of enzyme kinetics requires careful selection of reagents and computational tools.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Kinetic Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Enzyme | The catalyst of interest; source of kinetic behavior. | Requires precise concentration determination (e.g., A280, Bradford assay); purity critical to avoid confounding activities. |

| Authentic Substrate Standard | The molecule transformed in the reaction. | Purity must be verified; solubility in assay buffer is a key factor. |

| Cofactors (e.g., NADH, Mg²⁺) | Essential non-protein components for many enzymes. | Must be added at physiologically relevant concentrations; stability can be an issue. |

| Spectrophotometric Assay Kits | Enable continuous monitoring of product formation/substrate depletion. | Choice depends on chromophore/fluorophore properties (e.g., absorbance max, extinction coefficient). |

| Stopped-Flow Apparatus | For rapid mixing and data collection on millisecond timescales. | Essential for studying very fast reactions and obtaining true initial velocities. |

| Bayesian Inference Software | For robust parameter estimation and uncertainty quantification from progress curves. | Packages like Stan, PyMC, or specialized MATLAB toolboxes implement tQSSA-based fitting [18]. |

| Curated Kinetic Databases (BRENDA, SABIO-RK) | Source of prior knowledge for parameter initialization and comparison. | Contains thousands of ( k{cat} ) and ( KM ) values but requires careful curation [20]. |

Applications in Drug Development and Systems Biology

The choice between steady-state and more advanced kinetic models has profound implications in applied fields. In drug development, accurate characterization of enzyme-inhibitor interactions is vital. The classical model of inhibition (competitive, non-competitive, uncompetitive) is built upon the rapid-equilibrium or steady-state framework. However, these models often fail to distinguish between inhibitor binding and its functional effect, leading to the over-complication of modifier kinetics [21]. Simplified, universal modifier equations that more directly relate to binding curves are now emerging as powerful alternatives for characterizing both inhibitors and activators [21].

In systems biology and metabolic engineering, the goal is to build predictive models of cellular metabolism. These models require accurate in vivo kinetic parameters. The standard Michaelis-Menten equation often performs poorly for this task because intracellular environments frequently violate the low enzyme concentration assumption [18]. The tQSSA and related approximations provide a more solid foundation for predicting enzyme activity in vivo and for inferring kinetic parameters from omics data [18] [20]. Furthermore, machine learning frameworks like CatPred are now being developed to predict in vitro kinetic parameters (( k{cat} ), ( KM ), ( Ki )) from enzyme sequence and structure, helping to initialize and parameterize large-scale kinetic models of metabolism [20]. A key thermodynamic principle emerging from kinetic studies is that natural selection appears to tune an enzyme's ( KM ) to be close to the prevailing in vivo substrate concentration (( K_M \approx [S] )), a point that maximizes enzyme activity under thermodynamic constraints [15].

The distinction between the rapid equilibrium and steady-state assumptions is fundamental to a rigorous understanding of enzyme kinetics. While the resulting rate equations are identical in form, the interpretation of the parameters and the conditions for model validity differ substantially. Moving beyond the classical Michaelis-Menten framework towards more general models like the tQSSA is essential for accurate parameter estimation, especially in contexts where enzyme concentrations are high. The integration of robust experimental protocols, sophisticated computational fitting methods, and modern thermodynamic insights provides a powerful toolkit for researchers aiming to understand and engineer enzymatic activity in both basic research and applied pharmaceutical contexts. As the field advances, the synergy between careful experimental kinetics, advanced theoretical models, and emerging machine learning tools will continue to refine our ability to predict and control enzyme behavior.

Enzyme catalysis is fundamentally governed by thermodynamics and the spatial-temporal dynamics of the free energy landscape (FEL). The FEL provides a quantitative framework for understanding enzyme turnover, defining the probabilities of populating various conformational states along the reaction coordinate. The Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) serves as the central thermodynamic parameter dictating reaction spontaneity and catalytic efficiency. This whitepaper delineates the integration of FEL analysis with classical Michaelis-Menten kinetics, explores advanced experimental and computational methodologies for probing enzymatic thermodynamics, and discusses applications in rational enzyme engineering and drug development. By establishing a quantitative link between molecular-level motions and macroscopic kinetic parameters, this overview provides researchers with a foundational guide for interrogating and manipulating enzymatic function.

Enzyme kinetics has traditionally been framed by the Michaelis-Menten model, which provides essential parameters (k{cat}) and (Km) for quantifying catalytic efficiency. However, a comprehensive understanding of enzyme function requires moving beyond this static depiction to a dynamic thermodynamic model where the protein scaffold exhibits substantial motion over broad timescales [22]. The Free Energy Landscape (FEL) formalizes this concept, defining the conformational space accessible to an enzyme during catalysis and providing the link between atomic-scale flexibility and turnover rate [22]. Within this framework, the Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG) represents the "backbone" of enzyme thermodynamics, determining the direction and extent of chemical reactions. The general Gibbs free energy equation is expressed as (G = H - TS), where (H) is enthalpy, (T) is temperature, and (S) is entropy [23] [24]. For biochemical reactions, the change in free energy, ( \Delta G = \Delta H - T \Delta S ), dictates spontaneity: a negative ΔG indicates a thermodynamically favorable (exergonic) process, while a positive ΔG signifies a non-spontaneous (endergonic) one that requires energy input [23] [24]. This review synthesizes current understanding of how FELs and ΔG collectively govern enzyme kinetics, enabling researchers to deconstruct catalytic mechanisms and strategically engineer enzymes with enhanced properties.

Fundamental Thermodynamic Principles in Enzyme Kinetics

The Free Energy Landscape (FEL) and Enzyme Dynamics

The Free Energy Landscape represents the potential energy surface of an enzyme as a function of its conformational coordinates. Rather than existing in a single rigid structure, enzymes sample numerous conformational substates, with the FEL defining the relative probabilities and energy barriers between these states [22]. Catalytic efficiency is maximized when the FEL is optimized to reduce energy barriers along the reaction coordinate while maintaining specificity. Key thermodynamic parameters that define the FEL include:

- Activation Free Energy ((ΔG^‡)): The energy barrier between the enzyme-substrate complex and the transition state, directly determining the reaction rate according to transition state theory.

- Reaction Free Energy ((ΔG_{rxn})): The overall energy difference between substrates and products, dictoning reaction equilibrium.

- Change in Heat Capacity ((ΔC_p)): A critical parameter linked to the FEL that affects enzymatic activity, particularly in response to temperature changes [22].

- Isobaric Expansivity: Another key thermodynamic parameter identified in FEL analysis that influences enzyme turnover [22].

Restricting the FEL has emerged as a powerful strategy in rational enzyme engineering, particularly for altering thermal activity profiles [22]. Computational approaches can predict how mutations will affect the FEL, enabling targeted manipulation of enzymatic properties.

Integration of ΔG with Michaelis-Menten Kinetics

The classical Michaelis-Menten equation ( v = \frac{k{cat}[S][ET]}{K_m + [S]} ) describes reaction velocity but lacks explicit thermodynamic parameters. However, fundamental connections exist between kinetic and thermodynamic frameworks:

- (Km) and Substrate Affinity: While not a direct measure of binding affinity, (Km) relates to the enzyme-substrate interaction energy. Recent research demonstrates that tuning (Km) to match physiological substrate concentrations ([S]) enhances enzymatic activity, suggesting (Km = [S]) as an optimization principle [15].

- (k{cat}) and Activation Energy: The turnover number (k{cat}) reflects the activation free energy barrier ((ΔG^‡)) for the rate-limiting step, following the Arrhenius relationship.

- Thermodynamic Constraints on Parameter Optimization: Increasing (k{cat}) often comes at the expense of higher (Km), creating an optimization challenge. This trade-off is constrained by the fixed total free energy difference ((ΔG_T)) between substrate and product [15].

Table 1: Fundamental Thermodynamic Parameters in Enzyme Kinetics

| Parameter | Symbol | Thermodynamic Relationship | Kinetic Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔG | ΔG = ΔH - TΔS | Determines reaction spontaneity and equilibrium |

| Activation Free Energy | ΔG^‡ | ΔG^‡ = -RT ln(kcat/k) | Energy barrier for catalysis; directly impacts kcat |

| Michaelis Constant | Km | Km ≈ g1(1+K) [15] | Complex function of rate constants; relates to substrate affinity |

| Total Driving Force | ΔGT | ΔGT = ΔG1 + ΔG2 [15] | Fixed free energy difference between substrate and product |

Advanced Methodologies for Probing Enzymatic Thermodynamics

Experimental Approaches for FEL Analysis

Comprehensive thermodynamic analysis requires specialized experimental techniques that probe the FEL and its relationship to enzyme function:

- Combined Pressure and Temperature Kinetics: Simultaneously varying pressure and temperature enables researchers to extract the complete suite of thermodynamic parameters defining the FEL, particularly the isobaric expansivity and change in heat capacity for enzyme catalysis [22].

- Red Edge Excitation Shift (REES) Spectroscopy: This technique provides information on protein conformational flexibility and dynamics, offering insights into the shape and characteristics of the FEL [22].

- Viscosity Studies: Modifying solvent viscosity affects protein conformational sampling, allowing researchers to investigate the relationship between molecular motion and catalytic efficiency [22].

- mRNA-Display-Based Kinetic Measurements (DOMEK): This ultra-high-throughput method enables simultaneous determination of (k{cat}/Km) values for hundreds of thousands of peptide substrates, providing massive datasets for understanding substrate specificity and catalytic promiscuity [25].

Table 2: Key Experimental Methods for Thermodynamic Analysis of Enzymes

| Method | Key Measured Parameters | Applications in FEL Analysis | Throughput |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pressure-Temperature Kinetics | ΔCp, isobaric expansivity | Links FEL to enzyme turnover under different conditions | Low |

| DOMEK [25] | kcat/Km for >200,000 substrates | Maps substrate fitness landscapes; reveals sequence-activity relationships | Very High |

| Structure-Oriented Kinetics Dataset (SKiD) [26] | kcat, Km with 3D structural data | Correlates kinetic parameters with enzyme-substrate complex structures | Medium |

| Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi Analysis [15] | Relationship between ΔG and activation barriers | Quantifies trade-offs between reaction steps under fixed ΔGT | Low |

Computational and Bioinformatics Approaches

Computational methods provide essential tools for modeling FELs and predicting thermodynamic parameters:

- All-Atom Flexibility Calculations: Molecular dynamics simulations can model enzyme flexibility and conformational sampling, providing atomic-level insights into the FEL [22].

- Brønsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) Relationship: This empirical principle models activation barriers as a function of thermodynamic driving forces, enabling prediction of rate constants from free energy changes [15]. The relationship follows ( Ea = Ea^0 + αΔG ), where α represents the sensitivity of the activation barrier to the driving force.

- Bioinformatic Analysis of Natural Enzymes: Large-scale analysis of approximately 1000 wild-type enzymes reveals that natural systems often follow the principle (K_m = [S]), where the Michaelis constant is optimized to match in vivo substrate concentrations [15]. This optimization emerges from evolutionary pressure to maximize catalytic efficiency within thermodynamic constraints.

Data Integration and Visualization in Thermodynamic Studies

Structured Kinetic Databases

The integration of kinetic and structural data enables comprehensive analysis of enzymatic thermodynamics:

- SKiD (Structure-oriented Kinetics Dataset): This resource integrates experimentally measured (k{cat}) and (Km) values with three-dimensional structural data of enzyme-substrate complexes, enabling correlation of kinetic parameters with specific molecular interactions [26].

- BRENDA and SABIO-RK: These databases provide curated enzyme kinetic parameters extracted from scientific literature, serving as essential references for thermodynamic analysis [26].

- Data Curation Challenges: Issues include ambiguous reporting in literature, requiring manual verification and standardization. The STRENDA (Standards for Reporting Enzymology Data) commission addresses these challenges by establishing guidelines for unambiguous data reporting [26].

Experimental Workflow for Thermodynamic Profiling

The following diagram illustrates a integrated experimental-computational workflow for comprehensive thermodynamic analysis of enzymes:

Thermodynamic Optimization in Enzyme Engineering and Drug Development

Rational Engineering Based on FEL Manipulation

The strategic manipulation of Free Energy Landscapes provides powerful approaches for engineering improved enzymes:

- Thermal Activity Optimization: Restricting the FEL through protein engineering can alter temperature-activity profiles, enabling customization of enzymes for specific industrial processes [22].

- Substrate Affinity Tuning: The thermodynamic principle (K_m = [S]) provides a concrete guideline for enhancing enzymatic activity by optimizing the Michaelis constant to match operational substrate concentrations [15].

- Driving Force Allocation: When the total free energy change (ΔGT) for a reaction is fixed, optimal activity is achieved by strategically distributing this driving force between the substrate binding (E + S → ES) and catalytic (ES → E + P) steps [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Thermodynamic Studies of Enzymes

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| mRNA-Display Libraries | Generation of diverse peptide substrates for high-throughput kinetics | DOMEK method for measuring kcat/Km for >200,000 substrates [25] |

| Pressure-Temperature Cells | Simultaneous control of pressure and temperature for thermodynamic profiling | Determination of ΔCp and isobaric expansivity [22] |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Introduction of specific amino acid changes to probe FEL effects | Testing impact of specific mutations on conformational sampling [22] |

| Viscogenicity Modulators | Alter solvent viscosity to probe role of protein dynamics in catalysis | Viscosity studies to investigate FEL restrictions [22] |

| Structure-Kinetics Databases (SKiD) | Resource for correlating 3D structures with kinetic parameters | Mapping enzyme-substrate interactions to thermodynamic parameters [26] |

The thermodynamic backbone of enzyme catalysis, comprising the Free Energy Landscape and Gibbs free energy, provides the fundamental framework for understanding and manipulating enzymatic activity. The FEL concept transforms our perspective from static structural representations to dynamic energy surfaces that define catalytic efficiency. Through advanced experimental methodologies like pressure-temperature kinetics and high-throughput DOMEK analysis, combined with computational approaches and structured database resources, researchers can now quantitatively link molecular motions to kinetic parameters. The optimization principle (K_m = [S]), emerging from thermodynamic constraints under fixed total driving force, offers a concrete guideline for both natural evolution and rational enzyme engineering. As these thermodynamic principles become increasingly integrated with structural knowledge and kinetic data, they empower researchers to strategically design enzymes with enhanced properties for therapeutic and industrial applications, advancing the frontiers of biocatalysis and drug development.

The Haldane relationship represents a fundamental bridge between the kinetic parameters of enzyme-catalyzed reactions and their thermodynamic equilibrium properties. This principle establishes mathematically rigorous constraints between the Michaelis constants for forward and reverse reactions and the apparent equilibrium constant, ensuring internal consistency in enzymatic mechanisms. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding Haldane relationships is essential for proper kinetic model parameterization, deciphering regulatory mechanisms, and predicting metabolic flux distributions. This technical guide examines the theoretical foundation, experimental validation, and practical application of Haldane relationships in enzymology research, with particular emphasis on their critical role in maintaining thermodynamic consistency while enabling efficient sampling of kinetic parameter spaces.

Enzyme kinetics investigates the rates of enzyme-catalyzed chemical reactions, traditionally described for single-substrate mechanisms by the Michaelis-Menten equation [27]. This classical model introduces parameters such as kcat (turnover number) and KM (Michaelis constant), which quantify enzymatic efficiency and substrate affinity respectively. However, these kinetic parameters do not exist in isolation from thermodynamic principles. The Haldane relationship formalizes the intrinsic connection between enzyme kinetics and thermodynamics by expressing the apparent equilibrium constant (K'eq) of the overall reaction as a function of the kinetic parameters for both forward and reverse directions [28].

Biochemical thermodynamics governs the direction and extent of chemical reactions, with the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG) determining reaction spontaneity. For any enzyme-catalyzed reaction S ⇌ P, the overall thermodynamic driving force is fixed under given conditions, while kinetic parameters describe how rapidly the system approaches equilibrium. The fundamental insight of Haldane relationships is that despite kinetic parameters depending solely on the properties of the enzymatic site, their combination through Haldane equations must yield the apparent equilibrium constant, which is independent of the enzyme's properties [28]. This creates essential constraints for parameterizing kinetic models and interpreting experimental data.

Theoretical Foundation of the Haldane Relationship

Basic Mathematical Formulation

For a reversible single-substrate, single-product enzymatic reaction following the Michaelis-Menten mechanism, the Haldane relationship takes the form:

K'eq = (Vmaxf × KPr) / (Vmaxr × KSf)

Where:

- K'eq is the apparent equilibrium constant ([P]eq/[S]eq)

- Vmaxf and Vmaxr are the maximum velocities for forward and reverse reactions

- KSf is the Michaelis constant for the substrate in the forward direction

- KPr is the Michaelis constant for the product in the reverse direction

This fundamental relationship emerges directly from the principle of microscopic reversibility, which states that the forward pathway through the reaction mechanism must be thermodynamically equivalent to the reverse pathway [29]. For more complex reactions involving multiple substrates and products, the Haldane relationship expands to include all relevant Michaelis constants while maintaining the same fundamental constraint between kinetic parameters and thermodynamics.

Relationship to Free Energy Landscapes

The Haldane relationship reflects how enzymes distribute the total available thermodynamic driving force (ΔGT) between different steps in their catalytic cycle. As illustrated in recent thermodynamic analyses, enzymes face a fundamental trade-off: making the enzyme-substrate complex (ES) too stable (low ΔG1) decreases the driving force available for the catalytic step (ES → EP), potentially reducing kcat [15]. This relationship is quantitatively captured by the Bronsted-Evans-Polanyi (BEP) principle, which linearly correlates activation barriers with reaction driving forces [15].

Table 1: Fundamental Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters in Enzyme Catalysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Relationship to Haldane Equation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Gibbs Free Energy | ΔGT | Free energy difference between substrate and product | Fixed for given reaction conditions |

| ES Formation Free Energy | ΔG1 | Free energy for E + S → ES formation | Affects substrate KM |

| Catalytic Step Free Energy | ΔG2 | Free energy for ES → EP conversion | Affects kcat |

| Apparent Equilibrium Constant | K'eq | [P]eq/[S]eq at equilibrium | Constrained by Haldane relationship |

| Forward Maximum Velocity | Vmaxf | kcatf × [ET] | Measured kinetic parameter |

| Reverse Maximum Velocity | Vmaxr | kcatr × [ET] | Measured kinetic parameter |

Experimental Determination and Methodologies

Kinetic Assays for Parameter Estimation

Accurate experimental determination of Haldane relationships requires careful measurement of initial reaction rates under conditions where substrate and product concentrations do not significantly change during the assay period [27]. For comprehensive characterization, both forward and reverse reactions must be studied independently:

Initial Rate Measurements: Enzyme activity is measured while varying substrate concentrations while maintaining products at negligible levels (forward reaction), and vice versa (reverse reaction). For reactions where equilibrium strongly favors one direction, the unfavorable direction may require coupling to an auxiliary enzyme system to maintain low product concentrations [27].

Progress Curve Analysis: When initial rate measurements are challenging, the complete time course of the reaction can be fitted to integrated rate equations. This approach is particularly valuable for fast reactions or when the initial rate period is too brief to measure accurately [27]. Advanced methods include using the Lambert W function or logistic transformations to solve the integrated rate equations [30].

Thermodynamic Consistency Validation

Once kinetic parameters are obtained, researchers must verify they satisfy the Haldane relationship with the independently measured equilibrium constant. Discrepancies typically indicate either experimental error or an incorrect assumed mechanism. The following experimental workflow ensures proper validation:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for Haldane relationship validation

Computational Approaches and Thermodynamically Consistent Parameterization

Challenges in Kinetic Modeling

Traditional parameterization of enzymatic rate equations often results in thermodynamically inconsistent models that violate the Haldane relationships. This occurs particularly when kinetic parameters are estimated independently for different reaction directions or when simplified approximate expressions are used [29]. The General Reaction Assembly and Sampling Platform (GRASP) addresses these challenges by explicitly incorporating thermodynamic constraints during parameterization [29].

GRASP integrates the generalized Monod-Wyman-Changeux (MWC) model for allosteric regulation with elementary reaction formalism, enabling consistent parameterization of complex enzymatic mechanisms while maintaining thermodynamic feasibility [29]. This approach decomposes reaction velocity into independent catalytic and regulatory functions, with Haldane relationships ensuring microscopic reversibility across all elementary steps.

Efficient Sampling of Kinetic Parameter Spaces

Computational sampling of kinetic parameters must respect the constraints imposed by Haldane relationships. The following methodology enables efficient exploration of thermodynamically consistent parameter spaces:

- Define Reference State: Establish a reference reaction flux and thermodynamic affinity (ΔGT) based on experimental data

- Formulate Constraints: Implement Haldane relationships as equality constraints between kinetic parameters

- Sample Parameter Space: Use Monte Carlo techniques to uniformly sample feasible parameter combinations

- Validate Consistency: Verify that all sampled parameter sets satisfy fundamental thermodynamic principles

Table 2: Computational Sampling Parameters for Thermodynamically Consistent Kinetics

| Parameter Type | Sampling Method | Constraints | Implementation in GRASP |

|---|---|---|---|

| Elementary Rate Constants | Uniform logarithmic sampling | Must satisfy microscopic reversibility for all cycles | Enforced via Haldane relationships |

| Allosteric Constants | Uniform sampling within biophysical limits | Must be consistent with conformational equilibria | MWC model with thermodynamic constraints |

| Michaelis Constants | Derived from elementary rate constants | Related to Vmax values via Haldane | Calculated from sampled elementary parameters |

| Thermodynamic Affinities | Fixed based on experimental data | Determines relationship between forward/reverse parameters | Used as reference point for sampling |

Research Reagent Solutions for Haldane Relationship Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Kinetic and Thermodynamic Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Purification Systems | Affinity tags, chromatography resins | Obtain highly purified enzyme for kinetic assays |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | NAD+/NADH recycling enzymes, ATP regeneration systems | Maintain constant concentration of cofactors during assays |

| Coupled Enzyme Systems | Auxiliary dehydrogenases, ATPases | Measure reactions with unfavorable equilibrium by coupling to detectable signal |

| Isotopically Labeled Substrates | ^13C, ^15N, ^2H labeled metabolites | Track reaction progress using NMR or mass spectrometry |

| Rapid Kinetics Equipment | Stopped-flow, quenched-flow instruments | Measure rapid initial rates for fast enzymes |

| Buffers and Stabilizers | pH buffers, glycerol, protease inhibitors | Maintain enzyme activity and stability during assays |

Applications in Drug Development and Biotechnology

Enzyme Inhibitor Design and Validation

Haldane relationships provide critical constraints for evaluating enzyme inhibitors in drug discovery. For competitive inhibitors, the measured inhibition constant (Ki) must be consistent with the thermodynamic cycle involving substrate and product binding. Discrepancies may indicate allosteric mechanisms or non-competitive inhibition patterns. Furthermore, the Haldane relationship helps distinguish between true transition state analogs (which affect both forward and reverse reactions proportionally) and simple substrate analogs [31].

In neurological disorders, drugs targeting enzymes like acetylcholinesterase (AChE) and monoamine oxidase (MAO) must be evaluated considering the complete kinetic mechanism, including Haldane constraints [31]. For example, irreversible MAO inhibitors affect both reaction directions simultaneously, consistent with the covalent modification of the enzymatic site.

Metabolic Engineering and Biotechnology

Understanding the thermodynamic constraints imposed by Haldane relationships enables more effective metabolic engineering strategies. By analyzing the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of enzyme collections, researchers have discovered that natural enzymes often exhibit Michaelis constants (KM) closely matching their in vivo substrate concentrations (KM = [S]), a relationship that maximizes enzymatic activity under physiological conditions [15]. This principle guides enzyme selection and optimization for biosynthetic pathways.

In industrial biotechnology, Haldane relationships inform enzyme engineering strategies by identifying which kinetic parameters can be independently optimized and which are linked through thermodynamic constraints. For example, increasing kcat often comes at the expense of higher KM due to the trade-off governed by the total available driving force [15].

Advanced Considerations and Research Frontiers

Complex Kinetic Mechanisms

The basic Haldane relationship extends to more complex enzymatic mechanisms, including:

- Multi-Substrate Reactions: For enzymes with multiple substrates and products, the Haldane relationship incorporates all relevant Michaelis constants while maintaining the connection to the overall equilibrium constant [27]

- Allosteric Regulation: The MWC model for allosteric enzymes introduces additional parameters for tense and relaxed states, with Haldane relationships applying separately to each conformational state [29]

- Inhibition Mechanisms: For substrate inhibition described by Haldane-Radić kinetics, additional parameters quantify the efficiency of ternary complex (SES) hydrolysis relative to the binary complex (ES) [30]

Temperature, pH, and Ionic Strength Effects

Haldane relationships remain valid under varying conditions of temperature, pH, and ionic strength, though individual kinetic parameters may change significantly. Remarkably, the effects of these conditions on the enzymatic site must cancel in the Haldane relation, as the apparent equilibrium constant depends only on the properties of substrates and products in solution [28]. This provides a powerful consistency check for kinetic studies across different experimental conditions.

The Haldane relationship represents an essential connection between the kinetic behavior of enzymes and the fundamental thermodynamics of the reactions they catalyze. For researchers in enzymology, drug discovery, and metabolic engineering, proper application of Haldane relationships ensures kinetic models are thermodynamically consistent and biologically relevant. Contemporary computational frameworks like GRASP now enable efficient parameterization of complex enzymatic mechanisms while respecting these fundamental constraints, opening new possibilities for predictive metabolic modeling and rational enzyme design. As kinetic modeling continues to advance, the Haldane relationship remains a cornerstone principle guiding the integration of kinetic and thermodynamic information in biochemical research.