Immobilized Enzymes vs. Free Enzymes: A Comprehensive Performance Evaluation for Biomedical and Industrial Applications

This article provides a critical evaluation of immobilized enzyme performance compared to their free counterparts, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Immobilized Enzymes vs. Free Enzymes: A Comprehensive Performance Evaluation for Biomedical and Industrial Applications

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of immobilized enzyme performance compared to their free counterparts, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of enzyme stabilization, analyzes modern immobilization techniques and their applications in biomanufacturing and bioremediation, and addresses key challenges and optimization strategies. By presenting a comparative validation of stability, reusability, and cost-effectiveness across sectors, this review serves as a strategic guide for selecting and implementing immobilized enzyme systems to enhance therapeutic development and sustainable industrial processes.

The Fundamentals of Enzyme Stabilization: Why Immobilization is a Game-Changer

Enzymes, as nature's biocatalysts, play an indispensable role in numerous industrial processes, from pharmaceutical manufacturing to food processing and biofuel production [1]. Their ability to accelerate chemical reactions under mild conditions while generating less hazardous waste makes them environmentally preferable to traditional chemical catalysts [2]. However, the widespread industrial application of enzymes in their free, soluble form faces significant practical and economic challenges that limit their full potential. The core limitations of instability under operational conditions, high production costs, and inability to be reused create substantial barriers to their cost-effective implementation in industrial settings [3] [4].

This comparison guide objectively examines these fundamental challenges of free enzymes while evaluating the performance of immobilized enzyme systems as practical alternatives. By synthesizing current research data and experimental methodologies, we provide a structured framework for researchers and drug development professionals to assess the comparative advantages of different enzyme formulations for their specific applications. The analysis specifically focuses on quantitative performance metrics, experimental validation protocols, and technical implementation considerations relevant to industrial biocatalysis.

Core Challenges of Free Enzymes: A Systematic Analysis

The industrial use of free enzymes presents three interconnected challenges that significantly impact process efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and product quality.

Operational Instability and Denaturation

Free enzymes demonstrate limited stability when exposed to industrial process conditions. They are susceptible to denaturation at elevated temperatures, inactivation in organic solvents, and conformational changes under extreme pH fluctuations [1] [5]. This structural fragility leads to rapid activity loss during operation, requiring strict environmental control or continuous enzyme supplementation to maintain reaction rates [4]. In pharmaceutical applications, where process consistency is paramount, this instability introduces unacceptable variability in reaction kinetics and product quality [3].

Limited Reusability and Recovery Difficulties

Unlike chemical catalysts, free enzymes dissolve completely in reaction mixtures, creating significant challenges for recovery and reuse [3]. This single-use paradigm dramatically increases operational costs, as fresh enzyme must be supplied for each batch [4]. The inability to separate enzymes from products also raises concerns about potential contamination in pharmaceutical intermediates, necessitating additional purification steps that further increase production costs and complexity [6].

High Economic Costs

The combination of instability and non-reusability translates directly to substantially higher production costs [1]. Enzyme synthesis and purification are inherently expensive processes, and when these catalysts cannot be recovered or used repeatedly, the cost per unit of product becomes prohibitive for many large-scale applications [5]. This economic barrier is particularly significant in drug manufacturing, where stringent quality requirements already elevate production expenses [3].

Table 1: Core Challenges of Free Enzymes in Industrial Applications

| Challenge | Impact on Industrial Processes | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Instability | Denaturation at elevated temperatures | Reduced catalytic efficiency, need for precise temperature control |

| pH Sensitivity | Loss of activity outside narrow pH range | Limited operational window, requires buffering systems |

| Organic Solvent Inactivation | Structural damage in non-aqueous media | Restricted to aqueous systems, limiting substrate solubility |

| Inability to Reuse | Single-use paradigm | Continuous enzyme replenishment, high material costs |

| Difficult Recovery | Impossible separation from products | Product contamination, complex downstream processing |

Immobilized Enzymes as a Strategic Solution

Enzyme immobilization addresses the fundamental limitations of free enzymes by physically confining or localizing catalysts to a defined region of space while retaining catalytic activity [7]. This approach creates robust, reusable biocatalytic systems suitable for continuous industrial processes.

Immobilization Methods and Mechanisms

Multiple immobilization techniques have been developed, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications:

- Adsorption: Enzymes are physically attached to solid supports (e.g., silica, activated carbon) through weak forces like van der Waals interactions, hydrogen bonding, or ionic bonds [1] [3]. This method offers simplicity and preserves enzyme activity but may lead to leaching under changing conditions [8].

- Covalent Binding: Enzymes form stable covalent bonds with functionalized support materials [5]. This approach minimizes enzyme leakage and enhances stability but may reduce activity if the binding affects critical active site residues [9].

- Entrapment/Encapsulation: Enzymes are physically confined within porous matrices (e.g., polymer networks, microcapsules) [4]. This method protects enzymes from harsh environments but may introduce diffusion limitations [3].

- Cross-Linking: Enzyme molecules are interconnected using bi-functional reagents to create stable aggregates [5]. This carrier-free approach offers high enzyme loading but requires careful optimization [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Methods

| Method | Advantages | Limitations | Best Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Simple, inexpensive, minimal enzyme modification | Enzyme leaching under operational stress | Batch processes with stable parameters |

| Covalent Binding | Strong attachment, no leakage, high stability | Potential activity loss, complex procedure | Continuous processes requiring durability |

| Entrapment | Protection from harsh environments, high retention | Diffusion limitations, reduced activity | Processes with inhibitors or extreme conditions |

| Cross-Linking | High enzyme loading, no support cost | Activity reduction, optimization complexity | Systems where support introduction is problematic |

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Analysis

Immobilized enzymes demonstrate superior performance across multiple operational parameters compared to their free counterparts. The stabilization effect extends beyond single environmental factors to create more robust catalysts capable of withstanding varied industrial conditions.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Comparison of Free vs. Immobilized Enzymes

| Performance Parameter | Free Enzymes | Immobilized Enzymes | Experimental Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operational Half-life | Hours to days [4] | Days to months [4] | Activity retention over time under process conditions |

| Reusability Cycles | Single use [3] | 5-50+ cycles [9] | Residual activity after multiple batch cycles |

| Temperature Stability | Narrow range [1] | Up to 30-40°C broader range [8] | Optimal temperature and thermal denaturation point |

| pH Tolerance | Typically 2-3 pH units [8] | 3-5 pH units [8] | Activity profile across pH range |

| Storage Stability | Limited (weeks) [4] | Extended (months to years) [4] | Activity retention under storage conditions |

Experimental Protocols for Immobilized Enzyme Evaluation

Adsorption Immobilization Protocol

Materials Required:

- Support Material: Silica nanoparticles, activated carbon, or chitosan beads [1]

- Enzyme Solution: Purified enzyme in appropriate buffer

- Buffer Systems: Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), acetate buffer (pH 5.0)

Methodology:

- Support Preparation: Wash support material (e.g., silica nanoparticles) with buffer and dry at 60°C [5].

- Immobilization: Incubate support with enzyme solution (1-5 mg enzyme/g support) at 25°C for 2-4 hours with gentle agitation [3].

- Washing: Remove unbound enzyme by repeated centrifugation and washing with buffer.

- Activity Assay: Determine immobilized enzyme activity using substrate-specific assays compared to free enzyme controls.

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Enzyme-to-support ratio

- Incubation time and temperature

- pH and ionic strength of immobilization buffer

Covalent Immobilization Protocol

Materials Required:

- Functionalized Support: Amino- or epoxy-activated silica/synthetic polymers [6]

- Cross-linkers: Glutaraldehyde, carbodiimide [5]

- Buffer Systems: Carbonate buffer (pH 9.0-10.0 for epoxy activation)

Methodology:

- Support Activation: Treat support with glutaraldehyde (2-5% v/v) in buffer for 1-2 hours [5].

- Washing: Remove excess cross-linker by thorough washing.

- Enzyme Coupling: Incubate activated support with enzyme solution for 12-24 hours at 4°C [9].

- Blocking: Treat with inert protein (BSA) or amine-containing compounds to block residual active groups.

- Final Washing: Remove all unbound material before activity assessment.

Key Optimization Parameters:

- Cross-linker concentration and activation time

- Coupling pH and duration

- Enzyme loading density

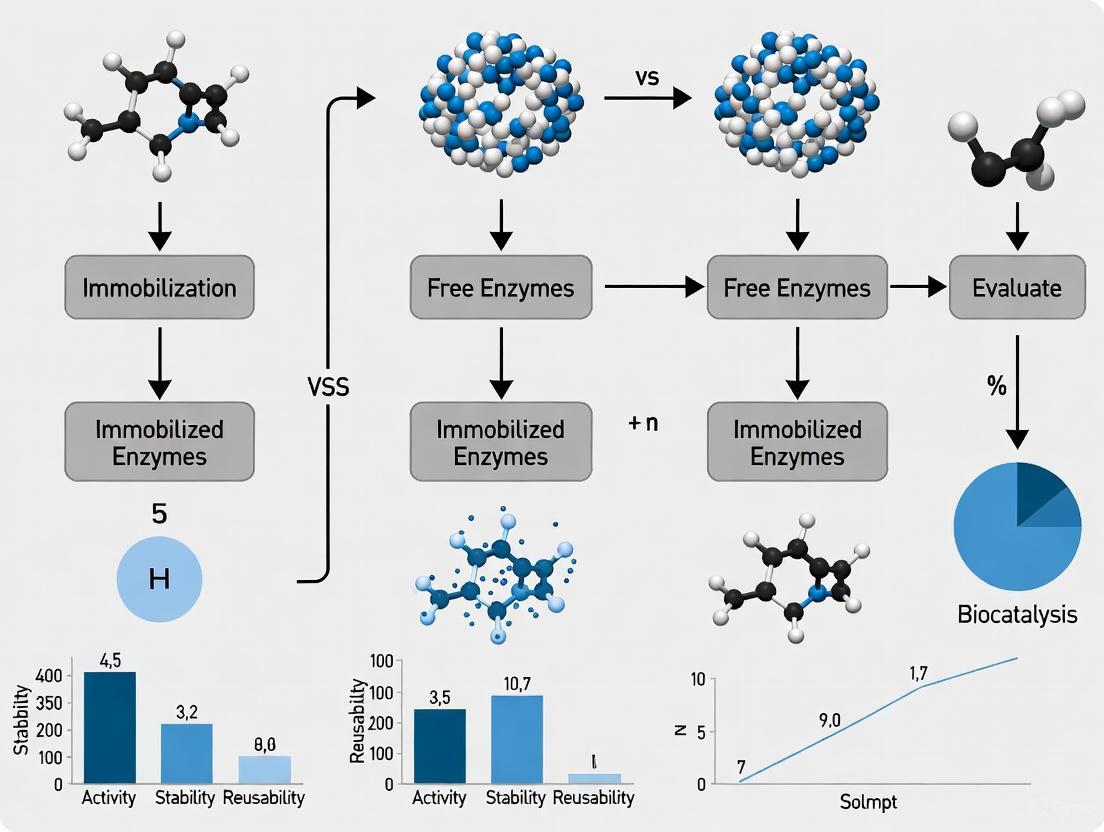

Visualization of Enzyme Immobilization Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Immobilization Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Support Materials | Provide surface for enzyme attachment | Silica nanoparticles (10-100nm), chitosan beads, epoxy-activated resins [6] |

| Activation Reagents | Create reactive groups on support surfaces | Glutaraldehyde (25% solution), carbodiimide, epichlorohydrin [5] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain optimal pH during immobilization | Phosphate (0.1M, pH 7.0), acetate (0.1M, pH 5.0), carbonate (0.1M, pH 10.0) |

| Enzyme Assay Kits | Quantify immobilization efficiency and activity | Bradford protein assay, substrate-specific colorimetric/fluorometric assays |

| Characterization Tools | Analyze immobilized enzyme properties | SEM for morphology, FTIR for chemical bonds, BET for surface area [9] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that immobilized enzyme systems offer significant advantages over free enzymes for industrial applications, particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing and drug development. Through various immobilization techniques, researchers can transform fragile, single-use biocatalysts into robust, reusable systems with enhanced operational stability and significantly reduced production costs [1] [2].

The experimental protocols and performance metrics provided establish a framework for objective evaluation of immobilized enzyme performance in specific applications. While the choice of optimal immobilization strategy depends on the particular enzyme, process conditions, and economic constraints, the fundamental benefits of immobilization—including extended enzyme lifespan, reusability, and improved process control—make these systems essential tools for advancing sustainable biocatalytic processes in the pharmaceutical industry and beyond [4] [6].

As immobilization technologies continue to evolve, particularly with advancements in nanomaterial supports and targeted immobilization methods, the performance gap between free and immobilized enzymes is expected to widen further, offering exciting opportunities for innovation in industrial biocatalysis.

Enzyme immobilization is defined as a technique where enzymes are physically confined or localized in a defined region of space with retention of their catalytic activities, and which can be used repeatedly and continuously [10]. This process restricts the enzyme's movement, either completely or to a small limited region, by attaching it to a solid support or matrix, transforming it from a water-soluble into a water-insoluble form [10]. The foundational concept of enzyme immobilization was first introduced by Nelson and Griffin in 1916 when they observed that invertase (also referred to as convertase) could hydrolyze sucrose after being adsorbed onto charcoal [11] [12]. However, the technology was not widely popularized until the 1960s, with the first significant industrial application being the immobilization of aminoacylases from Aspergillus oryzae for the production of L-amino acids in Japan [13] [10].

The primary impetus for developing immobilized enzymes lies in overcoming the inherent limitations of their free counterparts for industrial applications. While enzymes are powerful biological catalysts offering high specificity and the ability to function under mild conditions, their widespread industrial use is constrained by poor stability under extreme operational conditions (e.g., pH, temperature, solvents), short shelf life, difficulties in recovery and reuse, and high production costs [13] [14] [11]. Immobilization addresses these challenges by engineering biocatalysts with enhanced stability, facilitating easy separation from reaction products, enabling continuous operation, and allowing for multiple reuses, thereby making enzymatic processes more reliable and cost-effective [13] [14].

Core Principles and Methods of Enzyme Immobilization

The fundamental components of any immobilization system are the enzyme, the carrier/support, and the mode of interaction between them [10]. An effective immobilization system must securely anchor the enzyme to prevent unintended release, which could lead to product contamination and catalyst loss [13]. The choice of immobilization technique is critical, as it must be tailored not only to the specific enzyme but also to its intended application; there is no universal strategy that works for all scenarios [13].

Immobilization techniques are broadly categorized as carrier-bound (where the enzyme is attached to a support material) or carrier-free (where enzyme molecules are cross-linked to each other) [13]. These methods can be further classified as reversible (allowing for enzyme detachment) or irreversible [10]. The following sections and Table 1 compare the primary immobilization techniques.

Table 1: Comparison of Classical Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Immobilization Method | Binding Forces/Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common Support Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption [14] [10] | Weak forces (Van der Waals, hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic) | Simple, economical, limited activity loss, reversible, carrier can be regenerated | Enzyme leakage due to weak bonds, sensitive to pH/ionic strength, poor operational stability | Activated charcoal, alumina, silica, ion-exchange resins |

| Covalent Binding [15] [14] | Strong, irreversible covalent bonds between enzyme and support | No enzyme leakage, high stability, easy substrate contact, improved thermal stability | Potential activity loss due to conformational changes, expensive supports/setup, longer incubation time | Agarose, porous glass, chitosan, polymers (Eupergit C) |

| Entrapment [13] [10] | Physical enclosure within a porous polymer matrix | High enzyme loading, protects enzyme from harsh environments, reduces denaturation risk | Mass transfer limitations, possible enzyme leakage with large pore sizes | Polyacrylamide gels, alginate, silica gels, sol-gel matrices |

| Encapsulation [13] [10] | Enclosing enzymes within semi-permeable membrane capsules | Protects sensitive enzymes, maintains native structure, inexpensive for large quantities | Limited to small substrate and product molecules, potential diffusion barriers | Lipid vesicles, polymer membranes, nylon microcapsules |

| Cross-Linking [14] [10] | Intermolecular covalent bonds between enzyme molecules ( Carrier-free) | Very little desorption, high stability, reusable, no carrier cost | Can cause significant activity loss, time-consuming, expensive linkers | Glutaraldehyde, dextran, bis-diazobenzidine (as cross-linkers) |

Covalent Binding: A Deeper Dive

Covalent binding is one of the most widely used techniques due to the stable, irreversible bonds it forms, which prevent enzyme leakage [15] [14]. This method involves creating covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme's surface (e.g., amino groups of lysine, carboxyl groups of aspartic/glutamic acids, or thiol groups of cysteine) and reactive groups on a support material [14]. It is crucial that the functional groups involved in the binding are not essential for the enzyme's catalytic activity to avoid significant activity loss [14].

The process typically involves two steps: first, the activation of the carrier surface using linker molecules like glutaraldehyde or carbodiimide, and second, the coupling of the enzyme to the activated carrier [14]. Carbodiimide chemistry and Schiff base reactions are the two most common covalent techniques, leveraging the prevalence of amino and carboxyl groups on enzyme surfaces [15]. A key advantage is the potential for multipoint covalent bonding, where the enzyme is attached to the support through several residues, often leading to significant stabilization by rigidifying the enzyme's structure [14].

Performance Comparison: Immobilized vs. Free Enzymes

The ultimate value of immobilization is demonstrated through enhanced performance metrics. The following table summarizes experimental data comparing immobilized enzymes to their free counterparts across various applications.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data: Immobilized vs. Free Enzymes

| Enzyme | Immobilization Method & Support | Key Performance Findings vs. Free Enzyme | Application Context | Source/Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trypsin [12] | Covalent Binding (Schiff base) on Boronate Affinity Monolith | Retained 80% of initial activity after 28 days of storage at 4°C. | Proteomics (Protein Digestion) | (Wang et al.) |

| Lipase [16] | Covalent Binding on Magnetic Nanoparticles | Showed a 2.1-fold increase in enzymatic activity. | Biocatalysis | (Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization) |

| Cellulase [16] | Covalent Binding | Retained 73% of its initial activity after immobilization. | Biomass Conversion | (Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization) |

| Alkaline Phosphatase [16] | Entrapment within Silica Matrix | Retained 30% of its activity over a two-month period. | Biocatalysis | (Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization) |

| α-Glucosidase [16] | Entrapment in pHEMA polymer | Maintained 90% of its activity after multiple uses. | Biocatalysis | (Recent Advances in Enzyme Immobilization) |

| Laccase [13] | Entrapment in Alginate Beads | Effective for dye removal from water (Qualitative result). | Environmental Bioremediation | (A Comprehensive Guide...) |

| Horseradish Peroxidase [13] | Encapsulation into Tyramine-Alginate Beads | Improved stability and reusability (Qualitative result). | Biocatalysis | (A Comprehensive Guide...) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, detailed methodologies for key experiments are provided below.

Protocol 1: Covalent Immobilization on Hydroxyapatite (HAP) via APTES-Glutaraldehyde Activation [17] This protocol outlines a widely applicable strategy for covalent immobilization on a green, ceramic support.

- Support Derivatization: Suspend hydroxyapatite (HAP) nanoparticles in a 10% (v/v) solution of (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) in toluene. Heat the mixture under reflux at 110°C for 24 hours under an inert atmosphere.

- Washing: Cool the mixture to room temperature. Recover the amino-functionalized HAP (HAP-NH2) by centrifugation and wash thoroughly with toluene and ethanol to remove any unreacted APTES.

- Activation: Activate the HAP-NH2 support by incubating it with a 2.5% (v/v) aqueous solution of glutaraldehyde for 1 hour at room temperature with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Wash the activated support with distilled water to remove excess glutaraldehyde.

- Enzyme Coupling: Incubate the glutaraldehyde-activated HAP with the target enzyme (e.g., transaminase or decarboxylase) in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0-7.5) for 2-4 hours at 4°C.

- Washing and Storage: Recover the immobilized enzyme by centrifugation and wash extensively with buffer to remove any non-covalently bound enzyme. The prepared biocatalyst can be stored in buffer at 4°C.

Protocol 2: Adsorption Immobilization for Proteomics [12]

- Surface Preparation: A fused silica capillary or microfluidic chip is cleaned sequentially with NaOH, water, and the immobilization buffer.

- Conditioning: The surface is conditioned with the immobilization buffer (e.g., a low-concentration phosphate buffer, pH ~7-8).

- Enzyme Loading: A solution of the enzyme (e.g., Trypsin, dissolved in the same buffer) is perfused through the capillary or chip for a set period (e.g., 30-60 minutes). The pH is chosen to ensure the enzyme and support have opposite charges, facilitating electrostatic adsorption (e.g., for trypsin (pI ~10.3) at pH < pI, it is positively charged and will adsorb to the negatively charged silica surface).

- Washing: Unbound enzyme is flushed out with the immobilization buffer, leaving a layer of adsorbed enzyme on the inner surface.

Visualizing Immobilization Strategies and Performance

The following diagrams illustrate the logical relationships between immobilization goals, techniques, and outcomes.

Diagram 1: Immobilization Strategy Selection. This flowchart outlines the decision-making process for selecting an immobilization technique based on the primary goal of enhancing enzyme stability and reusability, leading to different performance outcomes.

Diagram 2: General Immobilization Workflow. This diagram shows the standard experimental workflow for immobilizing an enzyme, from initial support selection to final performance testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in Immobilization | Typical Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde [14] | A bifunctional cross-linker; forms Schiff bases with amino groups on enzymes and supports, creating stable covalent linkages. | Activation of aminated supports (e.g., chitosan, APTES-functionalized surfaces) for covalent binding; also used in Cross-Linking Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs). |

| Carbodiimide (e.g., EDC) [15] | A coupling reagent that activates carboxyl groups for direct reaction with amino groups, forming amide bonds. | Covalent immobilization of enzymes on carboxylated supports without the need for a pre-activated spacer. |

| APTES [17] | A silane coupling agent; introduces primary amino groups (-NH2) onto inorganic supports like silica, glass, or hydroxyapatite. | Primary functionalization step to create an aminated surface for subsequent activation with glutaraldehyde or other linkers. |

| Chitosan [14] [16] | A natural biopolymer carrier; possesses abundant amine and hydroxyl groups that facilitate direct enzyme binding or easy chemical modification. | Used as a versatile, biodegradable, and low-toxicity support for both adsorption and covalent immobilization. |

| Sodium Alginate [13] [16] | A natural polymer that forms a gel matrix in the presence of divalent cations like calcium (Ca²⁺). | A classic material for the entrapment and encapsulation of enzymes and whole cells via ionotropic gelation. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) [17] | An inorganic, ceramic support material; valued for its structural stability, non-toxicity, and large surface area. | An emerging "green" support for covalent immobilization, often functionalized with APTES and glutaraldehyde. |

The definition of enzyme immobilization encompasses a suite of techniques designed to confine enzymes to a defined space, fundamentally aiming to enhance their suitability for industrial and analytical applications. As demonstrated by the comparative data and protocols, the choice of immobilization method—be it adsorption, covalent binding, entrapment, or cross-linking—profoundly impacts critical performance metrics such as operational stability, reusability, and catalytic activity. While covalent methods often provide superior stability against leaching, physical methods like adsorption offer simplicity and cost-effectiveness. The historical success of immobilized enzymes in producing commodities like L-amino acids and high-fructose corn syrup, combined with ongoing advances in nanomaterial supports and carrier-free strategies, underscores the field's vitality. For researchers evaluating immobilized versus free enzymes, the decision matrix must be guided by the specific application requirements, balancing factors such as the need for stability against the constraints of mass transfer and activity retention to design the optimal biocatalytic system.

In the pursuit of sustainable and efficient industrial biocatalysis, enzyme immobilization has emerged as a powerful strategy to overcome the inherent limitations of free enzymes. While free enzymes are soluble catalysts that diffuse freely in the reaction medium, immobilized enzymes are physically confined or localized to a solid support or matrix while retaining their catalytic activities [7]. This fundamental difference forms the basis for a systematic performance comparison, particularly relevant for researchers and drug development professionals seeking robust biocatalytic solutions. The immobilization of enzymes translates into engineering of the biocatalyst, not merely for confinement, but for significant enhancement of its operational properties [13]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of immobilized enzyme performance against their free counterparts, focusing on the core advantages of enhanced stability, reusability, and reaction control, which are critical for pharmaceutical applications and industrial biotechnology.

Performance Comparison: Immobilized vs. Free Enzymes

The following tables summarize key experimental data and performance metrics from recent studies, providing a direct comparison between immobilized and free enzymes across critical parameters.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Operational Stability and Reusability

| Performance Parameter | Free Enzyme Performance | Immobilized Enzyme Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Stability (Half-life at elevated temperatures) | Rapid deactivation [11] | Enhanced resistance to thermal denaturation [8] | General property observed across multiple enzyme classes [11] [8]. |

| pH Stability (Activity range) | Narrow, optimal range [11] | Wider pH tolerance [8] | General property enabling operation in varied process conditions [11] [8]. |

| Operational Longevity | Single use, degraded post-reaction [4] | Repeated use over multiple cycles [4] | General industrial advantage; reduces enzyme consumption and cost [4]. |

| Reusability | Not reusable, discarded after single batch [18] | >22 full cycles with maintained activity [19] | Recombinant chitinase A immobilized on SA-mRHP beads [19]. |

| Storage Stability | Significant activity loss over time [14] | ~80% activity retained after 28 days at 4°C [12] | Trypsin covalently immobilized on a boronate affinity monolith [12]. |

Table 2: Comparative Kinetic Parameters and Process Efficiency

| Performance Parameter | Free Enzyme Performance | Immobilized Enzyme Performance | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Michaelis Constant (Km) | Standard Km | 2.12 to 2.18 times lower Km value [19] | Immobilized SmChiA, indicating higher substrate affinity [19]. |

| Reaction Time | 6 to 12 hours [12] | As low as 5-10 minutes [12] | Protolytic digestion for mass spectrometry proteomics [12]. |

| Product Separation | Complex purification required [4] | Easy separation from reaction mixture [4] [8] | General industrial advantage; simplifies downstream processing [4] [8]. |

| Activity Retention | 100% (baseline) | May be reduced due to conformational changes or mass transfer limitations [13] [8] | Trade-off for gained stability and reusability [13]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Performance Evaluations

Protocol for Assessing Thermal Stability and Half-Life

Objective: To determine the enhanced thermal stability of an immobilized enzyme by comparing its half-life with that of the free enzyme at an elevated temperature.

- Preparation: Prepare identical activity units (e.g., 1 U/mL) of both free and immobilized enzyme in a suitable buffer.

- Incubation: Incubate both enzyme forms at a constant elevated temperature (e.g., 60°C).

- Sampling: Periodically withdraw samples from the incubation mixture.

- Activity Assay: Immediately cool the samples on ice and measure the residual enzymatic activity under standard assay conditions. For the immobilized enzyme, separate the beads from the reaction mixture after the activity assay by simple filtration before measurement.

- Data Analysis: Plot the residual activity (%) versus time. The half-life (T1/2) is the time at which the enzyme retains 50% of its initial activity. The immobilized recombinant chitinase SmChiA demonstrated superior temperature stability and significantly longer half-lives compared to its free form [19].

Protocol for Determining Reusability

Objective: To evaluate the cost-effectiveness and operational stability of an immobilized enzyme by testing its activity over multiple reaction cycles.

- Initial Reaction: Conduct a standard catalytic reaction with the immobilized enzyme (e.g., dye decolorization or substrate hydrolysis).

- Separation: After the reaction cycle, separate the immobilized enzyme from the product mixture via simple filtration or centrifugation.

- Washing: Wash the immobilized enzyme thoroughly with buffer or water to remove any residual products or substrate.

- Reuse: Re-introduce the washed immobilized enzyme into a fresh reaction mixture with new substrate.

- Repetition and Measurement: Repeat steps 2-4 for multiple cycles. Measure the activity in each cycle and express it as a percentage of the activity in the first cycle. A study showed immobilized SmChiA maintained full activity after 22 reuse cycles [19].

Protocol for Analyzing Reaction Kinetics

Objective: To compare the catalytic efficiency and substrate affinity (Km) of immobilized and free enzymes.

- Substrate Series: Prepare a series of reactions with varying substrate concentrations.

- Reaction: Initiate the reaction by adding a fixed amount of free or immobilized enzyme to each substrate concentration.

- Initial Rate Measurement: Measure the initial velocity (V0) of the reaction for each substrate concentration.

- Plotting: Plot V0 versus substrate concentration ([S]) to create a Michaelis-Menten curve.

- Calculation: Calculate the Km and Vmax values using a Lineweaver-Burk plot or non-linear regression software. A lower Km for the immobilized enzyme, as seen with SmChiA, indicates a higher affinity for the substrate [19].

Visualization of Methodologies and Workflows

Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

Experimental Workflow for Performance Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Enzyme Immobilization and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate (SA) | Natural polymer for entrapment; forms gel beads with divalent cations. [19] | Base matrix for composite beads with rice husk powder. [19] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Cross-linking agent; creates covalent bonds between enzyme and support. [14] | Activation of aminated supports for stable enzyme attachment. [14] |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDAC) | Carbodiimide crosslinker; facilitates amide bond formation. [19] | Covalent immobilization of chitinase onto SA-modified rice husk beads. [19] |

| Silica-based Carriers | Inorganic support for adsorption/covalent binding; high surface area. [14] | Physical adsorption of enzymes like trypsin in microfluidic chips. [12] |

| Agarose-based Supports | Porous, hydrophilic resin for covalent immobilization. [14] | High-quality, sometimes costly carriers for stable enzyme fixation. [14] |

| Chitosan | Natural cationic polymer from chitin; adsorbent or matrix for covalent binding. [14] | Carrier for adsorption-based immobilization; eco-friendly material. [14] |

| Polyacrylamide | Synthetic polymer for entrapment within a gel matrix. [7] | Entrapment of enzymes like alcohol dehydrogenase. [7] |

The comparative data unequivocally demonstrates that immobilized enzymes hold significant advantages over free enzymes in terms of enhanced stability, excellent reusability, and superior reaction control, which are paramount for industrial and pharmaceutical applications. The ability to withstand harsh operational conditions, be reused for dozens of cycles and easily separated from the product stream translates directly into more economical, efficient, and sustainable biocatalytic processes [11] [4] [8]. While potential drawbacks such as a reduction in initial activity or mass transfer limitations must be considered [13], the overall benefits make immobilization a critical tool in biotechnology.

The choice of immobilization method and support material is highly dependent on the specific enzyme and its intended application [13]. For researchers in drug development, this technology offers a pathway to more robust catalysts for the synthesis of pharmaceutical intermediates, active ingredients, and for use in diagnostic biosensors. As enzyme engineering and immobilization technologies continue to advance, the performance gap between immobilized and free enzymes is expected to widen further, solidifying the role of immobilized enzymes as the biocatalyst of choice for the future of sustainable and efficient biomanufacturing.

In the pursuit of sustainable and efficient industrial biocatalysis, enzyme stabilization stands as a critical enabling technology. The inherent limitations of free enzymes—including sensitivity to environmental conditions, short operational lifespans, and difficult recovery—have driven the development of sophisticated stabilization methodologies [5]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the two primary stabilization strategies: immobilization and chemical modification, framed within the broader context of evaluating immobilized enzyme performance versus free enzyme research. For researchers and drug development professionals, selecting an appropriate stabilization strategy involves careful consideration of multiple performance parameters, including stability, reusability, catalytic efficiency, and implementation cost. The following sections present objective experimental data and detailed protocols to inform these critical decisions in bioprocess development.

Core Stabilization Mechanisms

Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

Enzyme immobilization refers to the confinement or localization of enzymes to a solid support or matrix, restricting their mobility while maintaining catalytic activity [5]. This approach enhances enzyme stability and facilitates reuse, significantly reducing operational costs in industrial applications [13]. The stabilization mechanism primarily involves preventing enzyme unfolding and denaturation by creating a stabilized, rigid structure [5].

Figure 1: Classification of major enzyme immobilization techniques, divided into carrier-bound and carrier-free methods.

The five primary immobilization techniques, each with distinct mechanisms and applications, include adsorption, covalent binding, entrapment, encapsulation, and cross-linking [5]. Adsorption, the simplest and most traditional method, relies on weak forces such as hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds, and van der Waals forces to attach enzymes to a support matrix [5]. While this method preserves high enzyme activity due to minimal conformational changes, it suffers from enzyme leakage under shifting pH or ionic strength [5]. Covalent binding forms stable, irreversible complexes through covalent bonds between enzyme functional groups (e.g., amino, carboxylic, or thiol groups) and an activated carrier surface, typically using linkers like glutaraldehyde or carbodiimide [5]. This method prevents enzyme leakage but carries a risk of activity loss if the active site is involved in bonding [5].

Entrapment confines enzymes within a porous polymer network or fiber matrix, while encapsulation encloses them within semi-permeable membranes or vesicles [5] [13]. Both methods protect enzymes from denaturation and the external environment while allowing substrate and product diffusion, though mass transfer limitations can reduce apparent activity [13]. Cross-linking creates carrier-free aggregates by forming covalent bonds between enzyme molecules using bifunctional reagents like glutaraldehyde, producing highly concentrated biocatalysts with excellent stability, though sometimes with reduced activity [13].

Chemical Modification Approaches

Chemical modification enhances enzyme stability by altering surface properties through covalent attachment of soluble polymers or other modifying agents [5]. Unlike immobilization, this approach maintains enzyme solubility while improving resistance to denaturing conditions. The most common strategy involves conjugation with chemically modified polysaccharides, which creates a protective microenvironment around the enzyme [5] [20]. This protective layer stabilizes the enzyme's tertiary structure against thermal agitation, pH fluctuations, and organic solvents, effectively reducing the rate of inactivation [5]. The primary mechanism involves surface charge modification and the introduction of steric hindrance that prevents aggregation and unfolding [5].

Performance Comparison: Stabilized vs. Free Enzymes

Quantitative Stability and Reusability Assessment

Table 1: Comparative performance metrics of immobilized, chemically modified, and free enzymes based on experimental data.

| Enzyme | Stabilization Method | Stability Improvement | Reusability (Cycles) | Activity Retention | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose Oxidase (GOX) | Glutaraldehyde crosslinking on aminated supports | 400-fold stabilization | >10 cycles | >80% after 10 cycles | [21] |

| Glutaryl Acylase (GAC) | Glutaraldehyde crosslinking on aminated supports | Significant stabilization | >10 cycles | >80% after 10 cycles | [21] |

| D-Aminoacid Oxidase (DAAO) | Glutaraldehyde crosslinking on aminated supports | Significant stabilization | >10 cycles | >80% after 10 cycles | [21] |

| Alkaline Protease | Entrapment in mesoporous silica | Not specified | Not specified | 63.5% immobilization yield | [13] |

| Alkaline Protease | Entrapment in zeolite | Not specified | Not specified | 79.77% immobilization yield | [13] |

| Typical Free Enzymes | None | Baseline | Single use | Rapid degradation | [5] |

The experimental data demonstrate that immobilization strategies, particularly cross-linking on aminated supports, can dramatically enhance enzyme stability, with glucose oxidase showing a remarkable 400-fold stabilization compared to its free counterpart [21]. This substantial improvement directly translates to extended operational lifespans and significantly reduced enzyme replacement costs in continuous processes. The reusability of immobilized enzymes—often exceeding 10 cycles while maintaining >80% initial activity—provides a compelling economic advantage over single-use free enzymes [21].

Operational Advantages and Limitations

Table 2: Comparative analysis of practical implementation factors for different stabilization methods.

| Parameter | Free Enzymes | Immobilized Enzymes | Chemically Modified Enzymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability under harsh conditions | Poor | Excellent | Good |

| Ease of separation from products | Difficult | Excellent | Moderate |

| Reusability potential | None | High (5-20+ cycles) | Limited |

| Risk of product contamination | High | Low to moderate | Low |

| Implementation cost | Low (but recurring) | High initial, lower long-term | Moderate |

| Catalytic efficiency | High | Often reduced | Slightly reduced |

| Applicability to continuous processes | Limited | Excellent | Moderate |

| Mass transfer limitations | None | Possible | None |

Immobilized enzymes offer distinct advantages for industrial applications, including excellent stability under harsh process conditions, straightforward separation from reaction mixtures, and high reusability potential [5] [13]. These characteristics make them particularly suitable for continuous manufacturing processes in pharmaceutical production. However, these benefits often come with trade-offs, including potential mass transfer limitations that can reduce apparent catalytic efficiency and higher initial implementation costs due to expensive support materials and complex procedures [5]. Chemically modified enzymes provide an intermediate solution, offering improved stability while maintaining solubility, though with more limited reusability compared to immobilized systems [5].

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Stabilization

Glutaraldehyde Crosslinking on Aminated Supports

This protocol, adapted from studies demonstrating up to 400-fold enzyme stabilization [21], provides a reliable method for creating highly stable immobilized enzyme preparations:

- Support Preparation: Select aminated supports (e.g., aminated silica, chitosan, or synthetic polymers). Wash supports thoroughly with distilled water and equilibrate in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

- Enzyme Adsorption: Incubate the aminated support with enzyme solution (1-5 mg/mL in appropriate buffer) for 2-4 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Crosslinking: Add glutaraldehyde to a final concentration of 0.5-2.0% (v/v) to the enzyme-adsorbed support. Incubate for 1-2 hours at 4°C with gentle agitation.

- Washing: Remove excess glutaraldehyde by extensive washing with buffer. Block any remaining active groups with 1M glycine solution if necessary.

- Storage: Store the crosslinked enzyme preparation in appropriate buffer at 4°C.

Critical parameters for success include optimizing the glutaraldehyde concentration to balance stability enhancement against activity loss and ensuring proper orientation during the initial adsorption phase to minimize active site obstruction [21].

Evaluation of Stabilization Efficiency

A standardized experimental workflow is essential for objectively comparing different stabilization methods:

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for systematic evaluation of enzyme stabilization efficiency.

- Activity Assays: Measure initial activity of free and stabilized enzymes under optimal conditions using appropriate substrates. For glucose oxidase, monitor hydrogen peroxide production spectrophotometrically at 415 nm using o-dianisidine as chromogen [21].

- Thermal Stability: Incubate enzyme preparations at elevated temperatures (e.g., 50-70°C) and withdraw aliquots at timed intervals for residual activity determination.

- pH Stability: Expose enzymes to various pH buffers (pH 3-10) for fixed durations, then measure remaining activity at optimal pH.

- Operational Stability: Conduct repeated batch reactions with immobilized enzymes, measuring activity after each cycle to assess reusability.

- Kinetic Analysis: Determine Km and Vmax values for free and stabilized enzymes to evaluate changes in substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential reagents and materials for enzyme stabilization research.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Aminated supports (e.g., aminated silica, chitosan) | Provides reactive groups for covalent attachment | Chitosan offers biocompatibility and multiple functional groups [5] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Bifunctional crosslinking agent | Forms Schiff bases with amino groups; concentration optimization critical [5] [21] |

| Carbodiimide (e.g., EDC) | Catalyst for carboxyl-amino group coupling | Used for zero-length crosslinking without incorporation of spacer [5] |

| Modified polysaccharides (e.g., dextran, chitosan derivatives) | Polymer matrices for chemical modification | Enhances stability through soluble conjugates [5] |

| Porous silica nanoparticles | High-surface-area support for adsorption | Excellent for adsorption techniques; tunable pore size [5] |

| Alginate beads | Entrapment matrix for enzyme encapsulation | Forms gentle gel network with calcium chloride [13] |

| Protein A/G/L beads | Affinity purification of enzymes with specific tags | Essential for recombinant enzymes with Fc or light chain tags [22] |

| Chromatography media (IEC, SEC) | Purification of enzymes pre/post stabilization | Key for obtaining pure enzyme before stabilization [23] [22] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that both immobilization and chemical modification offer substantial improvements over free enzymes in terms of stability, reusability, and industrial applicability. Immobilization techniques, particularly covalent binding and cross-linking, provide superior performance for continuous processes requiring enzyme reuse, while chemical modification offers a valuable alternative for applications where enzyme solubility must be maintained. The selection of an appropriate stabilization strategy must be guided by specific application requirements, cost considerations, and the physicochemical properties of the target enzyme. Future developments in enzyme stabilization will likely focus on hybrid approaches combining protein engineering with advanced immobilization techniques to create truly robust biocatalytic systems for pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Modern Immobilization Techniques and Their Transformative Applications

Enzyme immobilization has become a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, enabling the transformation of enzymes from soluble, single-use catalysts into robust, reusable biocatalysts. Within the broader context of evaluating immobilized enzyme performance versus free enzymes, this transformation is critical for industrial applications. Free enzymes, while highly active, often suffer from inherent limitations including poor stability under operational conditions, inability to be reused, and difficulty in separating from the reaction mixture [11] [24]. These challenges significantly increase process costs and complicate continuous manufacturing, rendering many enzymatic processes economically unviable at industrial scales.

Immobilization addresses these limitations by conferring enhanced stability, reusability, and operational flexibility [14]. The fundamental principle involves physically confining or localizing enzymes to a distinct space while retaining their catalytic activity, thereby allowing for repeated and continuous use [24]. As the demand for sustainable and green chemical processes grows, the strategic importance of selecting the appropriate immobilization technique intensifies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of four principal methods—adsorption, covalent binding, entrapment, and encapsulation—to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their experimental design and technology selection.

Core Principles of Enzyme Immobilization

Enzyme immobilization techniques can be broadly classified based on the nature of the interaction between the enzyme and the support matrix, and whether a support is used at all. The four methods discussed herein represent the most widely employed strategies in both academic research and industrial practice. Table 1 outlines the fundamental mechanisms, key advantages, and primary limitations of each method.

Table 1: Fundamental Overview of Immobilization Methods

| Immobilization Method | Mechanism of Binding/Confinement | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Weak physical forces (Van der Waals, electrostatic, hydrophobic) [14] [24] | Simple, inexpensive, minimal conformational change, high activity retention, reversible [14] [25] | Enzyme leakage, sensitive to operational conditions (pH, ionic strength) [14] [24] |

| Covalent Binding | Formation of strong covalent bonds between enzyme and activated support [15] [14] | Very stable, no enzyme leakage, high reusability potential [14] | Risk of activity loss due to harsh chemistry, potential denaturation, higher cost [14] |

| Entrapment | Enzyme physically confined within a porous polymer network or gel [25] | No chemical modification, protects enzyme from hostile environments, high loading capacity [25] | Mass transfer limitations, enzyme leakage if pore size is large, diffusion barriers [25] |

| Encapsulation | Enzyme enclosed within a semi-permeable membrane or capsule [25] [26] | High protection of enzyme, suitable for sensitive enzymes and cells [25] | Significant mass transfer resistance, limited substrate/product size, potential leakage [25] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical classification and key characteristics of these four primary immobilization methods, providing a visual summary of the options available to researchers.

Detailed Method Analysis and Comparison

Adsorption

Mechanism and Experimental Protocols

Adsorption relies on weak, non-covalent physical interactions to attach enzymes to a solid support material. The process is typically straightforward: the support is incubated in a solution of the enzyme for a predetermined period, after which the unadsorbed enzyme is removed by washing with buffer [14] [24]. The binding is driven by three main types of forces, which can be exploited selectively:

- Physical Adsorption: Based on van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic interactions. The support is simply soaked in the enzyme solution. A common variant is the Layer-by-Layer (LBL) deposition, where a charged substrate is alternately dipped into solutions of polyelectrolytes and oppositely charged enzymes to build up multilayered thin films [24].

- Electrostatic Binding/Ionic Adsorption: Utilizes ionic and strong polar interactions. The pH of the solution must be adjusted such that the enzyme and the support carry opposite net charges, determined by their isoelectric points [24].

- Hydrophobic Adsorption: Depends on the entropic gain from displacing water molecules from hydrophobic surfaces on both the support and the enzyme. The interaction strength can be modulated by varying pH, temperature, and salt concentration [24].

Performance and Stability Data

Adsorption is valued for its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. A key advantage is the high retention of catalytic activity, often exceeding 90%, because the method avoids harsh chemicals that can denature the enzyme [14]. However, the stability of the immobilized enzyme is highly dependent on the operational environment. Changes in pH, ionic strength, temperature, or the presence of surfactants can easily cause enzyme desorption (leakage) from the support, leading to product contamination and loss of activity over time [14] [24]. This makes adsorbed enzymes less suitable for processes involving rigorous reaction conditions or long-term operations.

Covalent Binding

Mechanism and Experimental Protocols

Covalent binding involves the formation of irreversible covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme's surface (e.g., amino groups of lysine, carboxylic groups of aspartic/glutamic acids, or thiol groups of cysteine) and reactive groups on an activated support matrix [15] [14]. The protocol generally involves two key steps:

- Support Activation: The carrier surface is treated with a bifunctional linker molecule to create electrophilic groups. Glutaraldehyde is one of the most common linkers, forming a so-called self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on the support. Alternatively, carbodiimide chemistry can be used to activate carboxyl groups for subsequent reaction with enzyme amino groups [15] [14].

- Enzyme Coupling: The activated support is incubated with the enzyme solution, leading to the formation of stable covalent linkages. Multipoint covalent attachment, where the enzyme is linked to the support through several residues, is particularly effective as it rigidifies the enzyme structure and enhances its stability [14].

Performance and Stability Data

The primary strength of covalent binding is its exceptional operational stability. The strong covalent bonds prevent enzyme leakage entirely, making this method ideal for applications where product purity is critical [14]. This stability often translates to a significantly higher number of reuse cycles compared to adsorption. The main drawback is the risk of activity loss. If the covalent modification occurs near or within the enzyme's active site, or if the chemical reaction conditions are too harsh, the enzyme can be denatured or its catalytic efficiency reduced [14]. The method also tends to be more expensive due to the cost of activated supports and chemicals.

Entrapment

Mechanism and Experimental Protocols

Entrapment involves physically enclosing enzymes within the interstices of a cross-linked polymer network or gel. The pore size of the matrix is designed to be small enough to prevent the enzyme from leaking out, but large enough to allow substrates and products to diffuse freely [25]. A standard protocol for a widely used method is as follows:

- Alginate Gel Entrapment: Enzymes are mixed with an aqueous solution of sodium alginate. This mixture is then added dropwise into a cold solution of calcium chloride (e.g., 0.1 M). The calcium ions cross-link the alginate polymer chains, instantaneously forming gel beads that trap the enzyme [26]. Other common materials for entrapment include carrageenan, polyacrylamide, and silica via sol-gel processes [25].

Performance and Stability Data

Entrapment offers the significant advantage of not requiring chemical modification of the enzyme, which minimizes the risk of denaturation during the immobilization process [25]. The polymer matrix also acts as a protective barrier, shielding the enzyme from denaturants, proteases, and shear forces in the external environment [25]. The major challenge is mass transfer limitation. The dense polymer network can create significant diffusion barriers for substrates and products, potentially leading to reduced observed reaction rates, especially for large substrate molecules. There is also a persistent risk of enzyme leakage if the pore sizes are not optimally controlled [25].

Encapsulation

Mechanism and Experimental Protocols

Encapsulation is similar to entrapment but typically confines enzymes within a distinct, membrane-bound compartment, such as a capsule, vesicle, or core-shell fiber. A sophisticated example is the core-shell electrospinning technique used for lactase:

- Core-Shell Electrospinning: In this method, an enzyme-containing aqueous solution forms the core, while a non-biodegradable polymer solution (e.g., PVDF-HFP) forms the shell. These two solutions are co-extruded through concentric nozzles under a high-voltage electric field, producing nanofibers where the enzyme is encapsulated within a protective polymer shell. This shield protects the enzyme from harsh conditions, such as during the repasteurization of milk [26].

Another advanced method involves creating a porous "interphase" at the water-oil interface of Pickering emulsion droplets. An enzyme-containing aqueous droplet is emulsified in oil, and a porous, nanometer-thick silica shell is grown at the interface. This creates a cell-like capsule where the enzyme resides in an aqueous environment while being accessible to organic substrates, enabling long-term stabilization (e.g., 800 hours for a lipase in continuous-flow epoxidation) [27].

Performance and Stability Data

Encapsulation provides a high degree of protection for the enzyme, making it suitable for even very sensitive enzymes and whole cells [25]. Systems like the core-shell fibers or porous interphase capsules exhibit remarkable long-term stability and reusability, as demonstrated by the lactase and lipase examples [26] [27]. Similar to entrapment, the primary limitation is mass transfer resistance. The membrane or shell can act as a significant barrier to the diffusion of substrates and products, which may lower overall catalytic efficiency. There is also a potential for enzyme leakage if the membrane integrity is compromised [25].

Comparative Performance Data

To facilitate an objective selection, Table 2 synthesizes key performance metrics for the four immobilization methods based on experimental data from the literature. This comparative overview highlights the inherent trade-offs between stability, activity, and practicality.

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Immobilization Methods

| Method | Binding Strength | Relative Activity Retention | Operational Stability & Reusability | Risk of Enzyme Leakage | Mass Transfer Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Low (Weak forces) | High (≥90% common) [14] | Low (Highly sensitive to conditions) [24] | High [14] | Low |

| Covalent Binding | Very High (Covalent bonds) | Moderate to High (Risk of active site damage) [14] | Very High (No leakage, high reuse cycles) [14] | Very Low [14] | Low to Moderate |

| Entrapment | N/A (Physical confinement) | High (No chemical modification) [25] | Moderate (Protected but can leak) [25] | Moderate [25] | High [25] |

| Encapsulation | N/A (Membrane confinement) | Moderate to High | High (e.g., 800h continuous flow [27]) | Low to Moderate [25] | High [25] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful immobilization requires careful selection of both the method and the supporting materials. The table below lists key reagents and their functions, as cited in the experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | Bifunctional cross-linker for covalent binding | Activates aminated supports (e.g., chitosan, aminated silica) for enzyme coupling [14] |

| Carbodiimide (e.g., EDC) | Activates carboxyl groups for covalent binding | Facilitates bond formation between support -COOH and enzyme -NH₂ groups [15] |

| Sodium Alginate | Polyanionic polymer for entrapment | Forms gel beads with CaCl₂ for gentle enzyme entrapment [26] |

| Chitosan | Polycationic biopolymer for adsorption/covalent binding | Used as a support for electrostatic adsorption or glutaraldehyde-activated covalent binding [14] [26] |

| Silica Nanoparticles | Inorganic support for adsorption/covalent binding | High surface area support; can be functionalized for different immobilization methods [14] |

| Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) | Water-soluble polymer for encapsulation | Used as a core polymer in core-shell electrospinning to host the enzyme [26] |

| Poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) (PVDF-HFP) | Non-biodegradable shell polymer for encapsulation | Forms a protective, mechanically stable shell in core-shell electrospinning [26] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Emerging crystalline porous support for covalent binding | Provide tunable porosity and high surface area for stable enzyme immobilization [28] |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that there is no single "best" immobilization method. The optimal choice is invariably a compromise dictated by the specific application requirements. Adsorption offers simplicity and high initial activity but suffers from stability issues. Covalent binding provides robust stability for repeated use but carries a higher cost and risk of activity loss. Entrapment and Encapsulation excel at protecting the enzyme from harsh environments but often introduce significant mass transfer limitations.

The selection process must be guided by a careful evaluation of the enzyme's characteristics, the nature of the substrate and product, the required operational lifespan, and economic constraints. Future advancements are likely to focus on hybrid strategies and novel materials, such as smart nanoparticles and 3D-printed enzyme supports, which promise to further enhance the stability, efficiency, and range of applications for immobilized enzymes in pharmaceutical and industrial biotechnology [28].

Enzyme immobilization represents a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, enabling the transformation of soluble biological catalysts into reusable, stable, and easily separable forms for industrial applications. The selection of an appropriate support material is arguably the most critical factor in determining the success of any enzyme immobilization strategy, as it directly influences catalytic efficiency, operational stability, and economic viability [29] [30]. Within the broader context of evaluating immobilized enzyme performance versus free enzymes, support materials function not merely as passive anchors but as active contributors that create a specialized microenvironment, profoundly affecting enzyme conformation, substrate accessibility, and resistance to denaturing conditions [14] [16].

Support materials are broadly categorized into three main classes: inorganic carriers, natural polymers, and novel nanomaterials. Each class offers distinct advantages and limitations based on its physicochemical properties, including surface area, porosity, functional group density, hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity balance, and mechanical strength [29] [9] [30]. Inorganic carriers typically provide exceptional mechanical and thermal stability; natural polymers offer superior biocompatibility and functionalization ease; while novel nanomaterials deliver unprecedented surface area-to-volume ratios and unique interfacial phenomena [31] [16] [32]. The rational selection among these options requires a deep understanding of their intrinsic properties and how they interact with specific enzyme molecules. This guide provides a systematic comparison of these support material classes, equipping researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to make informed decisions for diverse biocatalytic applications.

Comparative Analysis of Support Material Classes

The performance of immobilized enzymes is intimately tied to the properties of the support material. The following sections and comparative tables provide a detailed examination of the three primary material classes.

Inorganic Carriers

Inorganic supports are valued for their mechanical robustness, thermal stability, and resistance to microbial degradation and organic solvents [14] [16].

- Mesoporous Silica and Molecular Sieves: These materials feature highly ordered pore structures and large surface areas (often exceeding 500 m²/g), facilitating high enzyme loading. Their surfaces can be functionalized with silanol groups for hydrogen bonding or further modified with organosilanes to introduce specific binding moieties [30] [32]. A key study demonstrated that silanized molecular sieves effectively immobilized enzymes via hydrogen bonding, while biocompatible mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) showed long-term durability in energy applications [30].

- Calcium Carbonate: This material is an emerging, eco-friendly alternative. It is natural, non-toxic, inexpensive, and synthesized via simple scale-up processes. Biomineralized calcium carbonate microspheres (5.5 ± 1.8 μm) have been used to immobilize carboxyl esterase (CE). The enzyme was first adsorbed into the mesopores and then cross-linked with glutaraldehyde, resulting in a preparation that retained 60% of its initial activity after 10 reuse cycles and remained stable for over 30 days [33].

- Other Inorganic Materials: Titania, hydroxyapatite, and porous glass are also commonly used. Their general advantages include high rigidity and porosity under stressful conditions, making them suitable for continuous flow reactors [14] [16].

Table 1: Performance Summary of Inorganic Carriers in Enzyme Immobilization

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Experimental Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mesoporous Silica [30] [16] | High surface area, tunable pore size, thermal stability | pH sensitivity in strong alkaline conditions, cost of some precursors | Used in biocatalysis for energy applications; showed long-term durability and efficiency [30]. |

| Calcium Carbonate [33] | Biocompatible, biodegradable, low-cost, simple synthesis | Relatively lower mechanical strength | Cross-linked carboxyl esterase retained 60% activity after 10 reuses and 30 days storage [33]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) [9] [16] | Easy separation via magnetic field, high surface area, biocompatible | Can aggregate in acidic/oxidative environments, requires surface functionalization | Lipase on MNPs showed a 2.1-fold activity increase; enables facile catalyst recovery [9] [16]. |

Natural Polymers

Natural polymers, or biopolymers, are derived from renewable resources and are prized for their biocompatibility, biodegradability, and abundance of functional groups for enzyme attachment [14] [31] [16].

- Alginate: A water-soluble anionic polysaccharide derived from brown algae, composed of α-L-guluronate (G) and β-D-mannuronate (M) residues. It readily forms hydrogels in the presence of divalent cations like Ca²⁺, making it ideal for enzyme entrapment. Alginate beads have been used to immobilize a wide range of enzymes, including pectinase for juice clarification and lactase for lactose hydrolysis [31] [26]. The main drawback is the relative fragility of the beads, which can be mitigated by forming composite materials with other polymers like gelatin or carrageenan [26].

- Chitosan: Derived from chitin, this polysaccharide is rich in amine and hydroxyl groups, enabling direct enzyme binding without the need for cross-linkers. It is known for its low toxicity, biodegradability, and biocompatibility. Chitosan can be molded into beads, fibers, membranes, and gels, and it has been used to immobilize enzymes such as inulinase and lactase. Protease and lipase immobilized on chitosan nanoparticles exhibited enhanced stability across a broad pH and temperature range [31] [16].

- Other Biopolymers: Cellulose, carrageenan, agarose, and gelatin are also widely used. Cellulose, for instance, possesses modifiable surface hydroxyl groups, while carrageenan forms thermoreversible gels used for entrapping enzymes like lipase, which demonstrated stability in organic solvents [31] [26] [16].

Table 2: Performance Summary of Natural Polymer Carriers in Enzyme Immobilization

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Experimental Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alginate [31] [26] | Mild gelation (Ca²⁺), high biocompatibility, low cost | Gel instability in phosphate buffers, high porosity can cause leakage | Immobilized pectinase in alginate-graphene oxide beads used for efficient juice clarification [31]. |

| Chitosan [31] [16] | Abundant amino groups for binding, antimicrobial properties, versatile morphologies | Soluble in acidic conditions, requires activation in alkaline media for optimal binding | Lipase immobilized on chitosan composites showed broad pH/thermal stability and high reusability [16]. |

| Carrageenan [26] | Forms thermoreversible gels, food-grade material | Weaker mechanical strength, sensitive to ion types and concentrations | Lipase encapsulated in K-carrageenan was stable in pH 6-9 and temperatures up to 50°C in organic solvents [26]. |

Novel Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials have revolutionized enzyme immobilization by providing exceptionally high surface area-to-volume ratios and unique physicochemical properties that can enhance catalytic activity and stability [9] [16] [32].

- Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: This class includes carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene oxide. Their large surface area increases enzyme loading and catalytic efficiency. Functionalization is often required to improve dispersibility and introduce binding sites. Computational studies have shown that functionalized single-walled CNTs can provide structural support while preserving the active site geometry of enzymes like nitrilase, facilitating efficient catalytic conversion [9].

- Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs): Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) is the most widely used MNP due to its cost-effectiveness, biocompatibility, and superparamagnetic properties. The primary advantage is the effortless separation of the biocatalyst from the reaction mixture using an external magnet, simplifying downstream processing and enabling multiple reuse cycles. Lipase immobilized on MNPs has demonstrated significant increases in activity and stability [9] [16].

- Porous Framework Materials: This category represents a cutting-edge frontier and includes:

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Crystalline materials of metal ions and organic linkers with ultrahigh surface areas and tunable porosity. They allow for enzyme attachment on surfaces, diffusion into pores, or in-situ encapsulation via biomimetic mineralization [32].

- Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs): Purely organic, crystalline porous materials with high stability. Their designable structures make them ideal for creating a protective microenvironment for enzymes [32].

- Hydrogen-Bonded Organic Frameworks (HOFs): Metal-free porous materials assembled via hydrogen bonds. They are highly biocompatible and have recently emerged as promising supports for enzyme immobilization [32].

Table 3: Performance Summary of Novel Nanomaterial Carriers in Enzyme Immobilization

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Experimental Performance Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [9] | Extremely high surface area, enhances electronic properties, can boost activity | Potential for enzyme denaturation at pristine surfaces, requires functionalization | Functionalized swCNTs provided structural support to nitrilase, preserving active site and enabling efficient catalysis [9]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) [9] [16] | Superparamagnetism for easy recovery, high enzyme loading, recyclable | Can aggregate or degrade in harsh environments, cost of functionalization | Lipase on MNPs showed a 2.1-fold activity increase and could be reused for multiple cycles with magnetic separation [16]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [32] | Ultrahigh surface area, tunable pore size, versatile functionality | Stability in aqueous solutions can be limited for some types, complex synthesis | In-situ encapsulation protects enzymes from denaturation; used in high-sensitivity biosensors [32]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical framework for researchers, this section outlines standardized protocols for immobilizing enzymes on representative materials from each class.

Protocol 1: Enzyme Entrapment in Alginate Beads

This is a classic and straightforward method for immobilizing enzymes using the natural polymer alginate [31] [26].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve sodium alginate (e.g., 2-4% w/v) in distilled water with gentle heating and stirring to form a homogeneous solution. Allow the solution to cool to room temperature.

- Enzyme Incorporation: Gently mix the enzyme solution (e.g., lactase at 0.01 g/mL) with the sodium alginate solution. Avoid vigorous stirring to prevent enzyme denaturation.

- Bead Formation: Using a peristaltic pump or a syringe with a needle, drop the enzyme-alginate mixture into a gently stirred solution of calcium chloride (0.1 M). The drops will instantaneously form gel beads upon contact with the Ca²⁺ ions.

- Curing and Washing: Allow the beads to cure in the CaCl₂ solution for 30-60 minutes to ensure complete gelation and mechanical strength. Subsequently, collect the beads by filtration or sieving and wash them thoroughly with a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate-buffered saline, PBS) to remove any unentrapped enzyme and residual CaCl₂.

- Storage: The immobilized enzyme beads can be stored in a moist environment or in a small volume of buffer at 4°C until use.

Protocol 2: Adsorption and Cross-linking in Calcium Carbonate Microspheres

This protocol details a two-step process for creating a stable immobilized enzyme system within an inorganic carrier [33].

- Support Synthesis: Synthesize calcium carbonate microspheres by rapidly mixing 200 mM calcium chloride (in a 5:1 water:acetone solvent) with 200 mM ammonium carbonate under vigorous stirring for 10 minutes. Wash the resulting precipitate with ethanol and dry at 60°C.

- Enzyme Adsorption: Add a measured amount of the synthesized calcium carbonate microspheres (e.g., 10 mg) to a solution of the target enzyme (e.g., 1.5 mL of carboxyl esterase at 0.66 mg/mL). Vortex the mixture and then incubate with shaking (200 rpm) for 30-60 minutes to allow the enzyme to adsorb into the mesopores.

- Cross-linking: To prevent enzyme leakage and enhance stability, add a cross-linking agent such as glutaraldehyde (GA) to the suspension. For example, add 1.5 mL of a 1% GA solution to the above mixture and incubate for a fixed period to allow for cross-linking between adsorbed enzyme molecules.

- Washing and Recovery: After cross-linking, separate the microspheres by centrifugation and wash extensively with buffer to remove any unbound GA and non-cross-linked enzyme. The final immobilized enzyme preparation is now ready for use or storage.

Protocol 3: Covalent Immobilization on Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs)

This protocol leverages the easy separation of magnetic carriers and the stability of covalent bonds [9] [16].

- Support Functionalization: Commercially available or synthesized magnetic nanoparticles (e.g., Fe₃O₄) must first be functionalized with reactive groups. A common method is silanization, where MNPs are treated with (3-aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) to introduce surface amine (-NH₂) groups.

- Activation: The functionalized support is then activated using a bifunctional reagent. Glutaraldehyde is a popular choice. The aminated MNPs are incubated with a glutaraldehyde solution (e.g., 2-5% v/v), which reacts with the surface amines, leaving free aldehyde groups exposed.

- Enzyme Coupling: The activated MNPs are separated magnetically, washed to remove excess glutaraldehyde, and then mixed with the enzyme solution. The enzyme's free amino groups (e.g., from lysine residues) will form stable Schiff base linkages with the aldehyde groups on the support. The reaction is typically carried out in a neutral or slightly alkaline buffer for several hours.

- Quenching and Washing: After coupling, any remaining aldehyde groups are often "quenched" by adding a quenching agent like ethanolamine or glycine. The immobilized enzyme is then separated magnetically and washed repeatedly with buffer to remove any non-covalently bound enzyme.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting enzyme immobilization experiments across the different support material classes.

Table 4: The Scientist's Toolkit for Enzyme Immobilization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate | Natural polymer for entrapment; forms gels with divalent cations. | Entrapment of lactase or pectinase for food processing applications [31] [26]. |

| Chitosan | Natural polymer with amine groups for direct binding or cross-linking. | Preparation of beads for immobilizing inulinase or protease [31] [16]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | Bifunctional cross-linker for covalent binding and stabilizing enzyme aggregates. | Cross-linking enzymes adsorbed on calcium carbonate or aminated magnetic nanoparticles [9] [33]. |

| Calcium Chloride | Cross-linking agent for alginate; provides Ca²⁺ ions for gel formation. | Preparation of stable alginate beads for enzyme entrapment [31] [26]. |

| Aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) | Silanizing agent for introducing primary amine groups on inorganic surfaces. | Functionalization of silica nanoparticles or magnetic nanoparticles for covalent enzyme attachment [9] [16]. |

| Metal Salts (e.g., CaCl₂, (NH₄)₂CO₃) | Precursors for the synthesis of inorganic support materials. | Synthesis of biomineralized calcium carbonate microspheres [33]. |

Decision Workflow and Future Perspectives

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate support material based on the specific requirements of the biocatalytic application.