Mining Metagenomic Libraries for Novel Biocatalysts: A Guide for Discovery and Application in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging metagenomics to discover novel biocatalysts.

Mining Metagenomic Libraries for Novel Biocatalysts: A Guide for Discovery and Application in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals on leveraging metagenomics to discover novel biocatalysts. It covers the foundational rationale of accessing the vast metabolic potential of unculturable microorganisms, details current methodological approaches for functional and sequence-based screening, and offers practical troubleshooting for common technical challenges. The content further explores the validation of discovered enzymes and their comparative advantages, highlighting their direct application in creating sustainable processes for pharmaceutical synthesis, bioremediation, and the development of new antimicrobials like endolysins.

The Untapped Reservoir: Why Metagenomics is Revolutionizing Biocatalyst Discovery

The field of microbiology has long been constrained by a fundamental limitation: the inability to cultivate the vast majority of microbial life in laboratory settings. Current estimates indicate that more than 99% of prokaryotes in most environments cannot be cultured using standard laboratory techniques [1] [2] [3]. This phenomenon, often termed the "great plate count anomaly," represents a significant bottleneck in microbial research, leaving an immense reservoir of genetic and metabolic diversity—often referred to as "microbial dark matter"—largely unexplored [4] [5]. This limitation has profound implications for understanding global biogeochemical cycles, ecosystem functioning, and the discovery of novel bioactive compounds.

The challenge extends beyond academic curiosity. With the escalating threat of global antimicrobial resistance, there is an urgent need for new therapeutics with novel mechanisms of action, many of which are believed to reside within these uncultured microorganisms [5]. Furthermore, the overwhelming functional potential of uncultured microbes represents an untapped resource for biocatalysis, offering enzymes with unique properties suitable for industrial processes under mild and environmentally friendly conditions [6].

This whitepaper examines the innovative strategies developed to overcome the cultivation bottleneck, with a specific focus on accessing the genetic and metabolic potential of uncultured microorganisms for the discovery of novel biocatalysts. We explore both cultivation-dependent and independent approaches, their methodological frameworks, and their integration into a cohesive strategy for bioprospecting.

Understanding the Cultivation Challenge

The inability to culture most microorganisms stems from a complex interplay of factors that are difficult to replicate in artificial laboratory environments. These include:

- Fastidious Nutritional Requirements: Many uncultured microbes have highly specific nutrient needs that remain uncharacterized. Some rely on specific growth factors such as zincmethylphyrins, coproporphyrins, or short-chain fatty acids that are seldom included in standard media [5].

- Obligate Symbiotic Relationships: Numerous microorganisms exist in obligate symbiotic associations with other species, depending on metabolic byproducts or physical interactions that cannot be replicated in axenic culture [4] [5].

- Environmental Subtleties: Natural habitats feature complex physicochemical gradients (pH, temperature, oxygen availability, pressure) and spatial structures that are challenging to reproduce [5] [7].

- Microbial Social Dynamics: Both interspecies (symbiosis, competition, cross-feeding) and intraspecific interactions (quorum sensing, cooperation) profoundly affect microbial growth but are disrupted during isolation attempts [5].

- Low Abundance and Slow Growth: Many environmental microbes are adapted to low nutrient concentrations (oligotrophs) and grow slowly, making them susceptible to being outcompeted by fast-growing copiotrophs in enrichment cultures [4].

Table 1: Cultivation Success Rates Across Different Environments

| Environment | Estimated Species Richness | Cultivation Success Rate | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | >3,000 species/gram | <1% | Hyper-diversity, unknown growth requirements |

| Sargasso Sea | ~300 species/sample | Low (61% assembly rate but limited by contaminants) | Low biomass, contamination |

| Acid Mine Drainage | ~6 dominant species | High (85% sequence assembly rate) | Low diversity enables better genomic recovery |

| Freshwater Lakes | Variable (40-72% of genera detected) | 12.6% viability via advanced methods | Oligotrophic adaptations, genome streamlining |

| Human Gut | Hundreds of species | Biased toward fast-growing copiotrophs | Anaerobic requirements, complex symbioses |

Advanced Cultivation Techniques

High-Throughput Dilution-to-Extinction Cultivation

Recent innovations in cultivation methodologies have begun to chip away at the microbial dark matter. Dilution-to-extinction cultivation in sterilized environmental water or defined artificial media has proven particularly successful for isolating abundant aquatic oligotrophs [4]. This approach involves serially diluting environmental samples to the point where individual wells contain approximately one cell, then incubating for extended periods (6-8 weeks) under conditions that mimic the native environment.

A landmark 2025 study applied this approach to samples from 14 Central European lakes using defined media that mimic natural conditions [4]. The research yielded 627 axenic strains, including representatives from 15 genera among the 30 most abundant freshwater bacteria. These cultures represented up to 72% of genera detected in the original samples and included many slowly growing, genome-streamlined oligotrophs that are notoriously underrepresented in public repositories [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Advanced Microbial Cultivation

| Reagent/Medium | Composition | Application | Key Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Defined Media (med2/med3) | Carbohydrates, organic acids, catalase, vitamins in µM concentrations | Freshwater oligotroph isolation | Mimics natural carbon concentrations in lakes |

| MM-med Medium | Methanol, methylamine, vitamins | Methylotroph isolation | Selective for bacteria utilizing C1 compounds |

| PDMS Magnetic Capsules | Polydimethylsiloxane, iron oxide nanoparticles, controlled porosity | In situ cultivation | Semi-permeable membrane allows nutrient/waste exchange while containing cells |

| Diffusion Chambers | Semi-permeable membranes mounted between environmental samples | Uncultured soil bacteria | Allows chemical exchange with natural environment while containing cells |

| Continuous-Flow Cell Systems | Controlled nutrient delivery, waste removal | Fastidious microbes, syntrophic communities | Maintains chemical gradients and removes inhibitory metabolites |

In Situ Cultivation and Co-culture Approaches

Perhaps the most innovative cultivation strategies involve maintaining microorganisms in their natural environments while still enabling researchers to retrieve them. A groundbreaking 2025 approach uses tiny magnetic capsules to overcome the cultivation bottleneck [8]. Researchers created semipermeable, magnetic polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) spheres that encapsulate microbial cells while allowing nutrients and waste products to diffuse freely.

The process involves flowing three liquids together to spontaneously form layered, semipermeable spheres at a rate of approximately 6,000 per minute [8]. These "nanoculture bubbles" contain culture medium encased in a layer of PDMS and iron oxide nanoparticles, allowing them to be retrieved from complex environments using magnets. This technology enables microbes to grow in their native soil or ocean water habitats while being contained for later collection, effectively eliminating the competition problem that plagues traditional methods.

Other innovative approaches include:

- Diffusion chambers: Devices with semi-permeable membranes that allow chemical exchange with the natural environment while containing the target microorganisms [5].

- Co-culture systems: Intentional cultivation of multiple species together to replicate essential microbial interactions [5].

- Microfluidic cultivation devices: Miniaturized systems that enable high-throughput cultivation under controlled conditions [5].

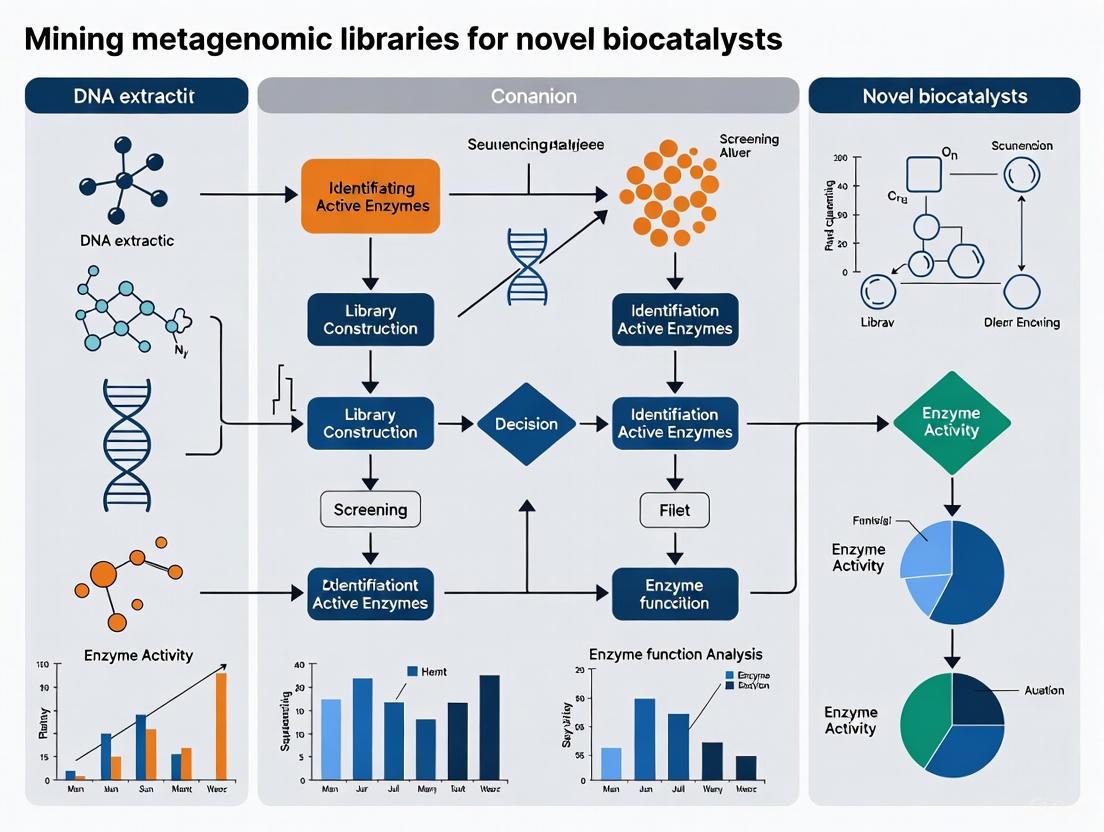

Figure 1: Integrated workflow combining advanced cultivation with metagenomic screening for biocatalyst discovery

Metagenomics: Bypassing Cultivation Entirely

Metagenomic Workflows and Methodologies

Metagenomics represents a paradigm shift in microbial studies, enabling researchers to access genetic information directly from environmental samples without the need for cultivation [1] [2]. The standard metagenomic workflow involves several key steps:

- Environmental Sampling: Careful collection of samples from diverse habitats, with attention to preserving nucleic acid integrity and representing in situ conditions.

- DNA Extraction: Liberation and purification of DNA from environmental samples, often complicated by co-purification of inhibitory substances like polyphenolic compounds [2].

- Library Construction: Cloning of environmental DNA (eDNA) into cultivable host organisms (typically Escherichia coli) to create metagenomic libraries [2] [3].

- Sequencing and Assembly: High-throughput sequencing followed by computational assembly of sequence reads into contigs or scaffolds, with varying success rates depending on community complexity [1].

The application of this approach ranges from simple communities like acid mine drainage biofilms (with only 3 bacterial and 3 archaeal lineages) to highly complex environments like agricultural soils (containing >3,000 species) [1]. The assembly success reflects this complexity, with 85% of sequence reads assembling into scaffolds in the simple acid mine community compared to less than 1% in Minnesota farm soil [1].

Screening Strategies for Biocatalyst Discovery

Metagenomic libraries can be screened for novel biocatalysts using two primary approaches: function-based screening and sequence-based screening [6] [3].

Function-based screening relies on heterologous expression of eDNA in a model host to yield a detectable phenotype. This approach includes:

- Direct activity assays: Libraries are plated on media containing substrates for enzymes of interest, with positive clones identified through zones of clearance or color changes [3].

- Reporter systems and complementation: Using engineered host strains that produce detectable signals when specific metabolic functions are present [3].

- Substrate-induced gene expression (SIGEX): This product-responsive reporter assay screens metagenomic libraries for enzyme-encoding genes [3].

Sequence-based screening utilizes known sequence homology to identify novel genes and includes:

- PCR amplification using degenerate primers designed from conserved regions of known enzyme families [3].

- Hybridization-based screening with probes targeting specific gene sequences.

- Bioinformatic mining of metagenomic sequencing data using tools like BLAST to identify genes of interest [6].

Figure 2: Metagenomic screening approaches for novel biocatalyst discovery

Computational Tools for Metagenomic Analysis

The computational analysis of metagenomic data presents significant challenges due to the volume and complexity of the data. Tools like METABOLIC (METabolic And BiogeOchemistry anaLyses In miCrobes) have been developed to profile metabolic and biogeochemical traits in microbial communities based on genomic data [9]. METABOLIC integrates annotations from multiple databases (KEGG, TIGRfam, Pfam), incorporates protein motif validation, and determines the presence or absence of metabolic pathways based on KEGG modules [9].

This software enables researchers to move beyond simple annotation to understanding community-scale metabolic networks, microbial interactions, and contributions to biogeochemical cycling—all critical for putting biocatalyst discovery in ecological context.

Success Stories and Applications

Novel Biocatalysts from Metagenomic Studies

Metagenomic approaches have yielded numerous industrially relevant enzymes with unique properties. Success stories include:

- Lipases and esterases with novel substrate specificities and stability under extreme conditions [6] [3].

- Glycosyl hydrolases for biomass degradation with high activity against recalcitrant substrates [3].

- Nitrilases for enantioselective production of carboxylic acid derivatives, important for pharmaceutical synthesis [2].

- Alkaline proteases with applications in detergents and waste processing [3].

The probability of uncovering novel sequences through metagenomics is significantly higher than from searches in cultivated microbes, as this approach accesses the immense diversity of uncultured microorganisms [2].

Natural Product Discovery

Beyond discrete enzymes, metagenomics has enabled the discovery of complete biosynthetic pathways for novel natural products. Notable examples include:

- Novel glycopeptide antibiotics related to vancomycin identified using degenerate primers for conserved oxidative coupling enzymes [3].

- Cyanobactins, ribosomally synthesized cyclic peptides with cytotoxic activities, discovered from uncultured cyanobacterial symbionts [3].

- Type II polyketides, including antimicrobial and anticancer agents, identified by targeting conserved ketosynthase genes [3].

- The anticancer agent ET-743 (trabectedin), whose biosynthetic cluster was recovered from uncultured tunicate bacterial symbionts [3].

Table 3: Representative Natural Products Discovered via Metagenomic Approaches

| Natural Product | Source Environment | Bioactivity | Discovery Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patellamide | Marine sponge symbionts | Cytotoxic | Metagenomic library construction and heterologous expression |

| Novel Glycopeptides | Soil | Antibacterial (anti-Gram-positive) | PCR targeting conserved OxyC sequences |

| ET-743 | Tunicate symbionts | Anticancer | Metagenomic library screening based on structural similarities |

| Trans-AT Polyketides | Marine environments | Various pharmacological activities | Phylogenetic targeting of trans-AT ketosynthase domains |

| Bisucaberin | Deep sea metagenome | Siderophore activity | Heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene cluster |

Integrated Approaches and Future Directions

The most powerful strategies for accessing uncultured microbes combine multiple complementary approaches. Integrated workflows that couple advanced cultivation techniques with metagenomic analysis provide the most comprehensive access to microbial dark matter [4] [5].

The proteogenomic approach demonstrates this integration powerfully. In the acid mine drainage biofilm study, researchers combined metagenomic sequencing with shotgun mass spectrometry of community proteins [1]. This enabled them to link peptide sequences to approximately 49% of the open reading frames from the dominant genomes and identify Cyt579, a novel acid-stable iron-oxidizing cytochrome that mediates the rate-limiting step in acid production [1].

Future directions in the field include:

- Single-cell genomics: Isolation and genomic analysis of individual microbial cells from complex environments, bypassing both cultivation and assembly challenges [3].

- CRISPR-based genome editing: Direct manipulation of uncultured organisms in their native environments [5].

- Synthetic biology: Reconstruction of complete biosynthetic pathways in heterologous hosts [5] [3].

- Machine learning approaches: Prediction of growth requirements and culture conditions based on genomic features [6].

- Microbial community engineering: Designing synthetic consortia that support the growth of fastidious uncultured organisms [5].

Advances in sequencing technologies, bioinformatics prediction tools, heterologous expression methods, and synthetic biology will continue to enhance our ability to access and utilize the genetic potential of uncultured microorganisms [3].

The "cultivation bottleneck" no longer represents an impenetrable barrier to exploring the microbial world. Through innovative cultivation strategies, metagenomic approaches, and integrated methodologies, researchers are progressively accessing the genetic and metabolic diversity of the previously uncultured 99% of microbes. These advances are transforming our understanding of microbial ecology and evolution while simultaneously opening up new frontiers for biocatalyst and natural product discovery.

As these technologies continue to mature and become more accessible, we can anticipate a new era of microbial research—one that fully embraces the complexity and diversity of the microbial world and harnesses this knowledge to address pressing challenges in medicine, industry, and environmental sustainability.

The term metagenome refers to the collective genetic content of all microorganisms found within a specific environmental sample [10]. This concept underpins the field of metagenomics, which involves the direct extraction, sequencing, and analysis of DNA from environmental sources like soil, seawater, or marine sediments, bypassing the need for laboratory cultivation of individual species [11] [12]. Traditional microbial cultivation methods can access less than 1% of the bacterial and archaeal species in a typical sample, leaving the vast majority of microbial diversity unexplored [11]. Metagenomics has revolutionized microbial ecology and evolutionary biology by providing unprecedented access to this previously hidden reservoir of genes, metabolic pathways, and functional capabilities [10] [11].

The application of metagenomics is particularly powerful for discovering novel biocatalysts—enzymes with potential uses in industrial chemistry, pharmaceuticals, and biofuels [13]. These enzymes, often derived from uncultured microorganisms, are exquisitely selective and catalyze reactions with unparalleled chiral and positional selectivities, offering 'green' solutions for chemical synthesis [13]. Marine environments, for instance, are a rich reservoir of highly diverse and unique biocatalysts, and metagenomics provides the key to unlocking this potential [12].

Methodological Approaches in Metagenomics

Sequencing Technologies and Workflow

Metagenomic studies rely on high-throughput DNA sequencing technologies to decode the genetic material within a sample. The field has moved from early clone library construction to advanced shotgun sequencing, where DNA is randomly sheared into fragments, sequenced, and then computationally reassembled into consensus sequences [10] [11]. The choice of sequencing technology involves trade-offs between read length, throughput, and cost.

- Short-Read Sequencing (Illumina): Provides high throughput and accuracy but generates shorter reads (typically 400-700 bp), which can complicate genome assembly [11].

- Long-Read Sequencing (PacBio, Oxford Nanopore): Generates significantly longer reads (thousands to millions of base pairs), simplifying the assembly process, particularly in repetitive genomic regions [11].

A critical consideration is sequencing depth—the number of times each base is read. Higher depth leads to greater resolution, more complete genomes, and a higher probability of discovering genes from low-abundance community members [11]. The following diagram illustrates the core workflow for generating and analyzing metagenomic data.

Bioinformatics and Data Analysis

The data generated from metagenomic sequencing is both enormous and complex, often representing fragments from thousands of species [11]. A primary bioinformatics challenge is binning, the process of assigning sequences to their taxonomic groups. This can be achieved through:

- Composition-based binning: Uses inherent sequence characteristics like GC content, codon usage, or tetranucleotide frequency to cluster sequences [10] [11].

- Similarity-based binning: Relies on comparing sequences to annotated references in databases, offering higher accuracy but requiring greater computational resources [10].

Sequences are assembled into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs), which provide a genomic context for discovered genes and enable the deduction of metabolic pathways [10] [11]. Comparing metagenomes and MAGs over time allows researchers to track evolutionary changes, such as single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), and identify genomic targets of selection [10].

Mining Metagenomic Libraries for Novel Biocatalysts

Strategies for Biocatalyst Discovery

Three primary strategies are employed to discover novel enzymes from metagenomic libraries, each with distinct advantages and limitations [13].

Table 1: Strategies for Mining Biocatalysts from Metagenomic Libraries

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology-Driven Screening [13] | Uses probes or degenerate primers to target genes with sequence similarity to known enzymes. | Straightforward if conserved motifs are known. | Artificially limits discovery to known enzyme classes; cannot find novel protein folds. |

| Activity-Based Screening [13] [12] | Clones are screened for expression of a desired enzymatic activity using high-throughput assays. | Guarantees discovery of active enzymes; can reveal entirely novel protein families. | Requires functional gene expression in a host (e.g., E. coli); development of assays can be complex. |

| Substrate-Induced Gene Expression (SIGEX) [13] | Selects for clones where catabolic gene expression is induced by a specific substrate, using fluorescence-activated cell sorting. | Highly efficient for finding catabolic pathways; automates screening. | Limited to substrate-inducible genes and promoters. |

Activity-based screening is considered a particularly "robust" strategy because it is not biased by prior sequence knowledge and directly confirms the desired catalytic function [13]. The process of constructing and screening a metagenomic library is detailed below.

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Successful mining of metagenomic libraries depends on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table outlines essential components of the "scientist's toolkit" for this field.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Library Mining

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) [11] | Vectors for cloning large DNA fragments (often >100 kbp), helping to capture large gene clusters and operons. |

| Fluorescent Substrates [13] | Used in high-throughput activity-based screens; enzyme activity produces a detectable fluorescent signal. |

| Degenerate Primers [13] | Designed to target conserved enzyme regions; allow PCR amplification of related but unknown gene variants. |

| Expression Hosts (e.g., E. coli) [13] [12] | Heterologous host for expressing genes cloned from the metagenomic library. |

| Agar Plates with Indicator Substrates [13] | Solid media for initial activity screening (e.g., cellulose for cellulases); activity is visualized by zone of clearance. |

Metagenomics has fundamentally altered the approach to discovering microbial diversity and novel biocatalysts. By moving beyond the constraints of cultivation, it provides a direct path to the genetic wealth of entire microbial communities [10] [11]. Future progress will be driven by advancements in long-read sequencing technologies, which improve genome assembly from complex samples [11], and the integration of complementary 'omics' approaches. Metatranscriptomics and metaproteomics offer insights into the functional dynamics of microbial communities by revealing which genes are actively expressed and translated into proteins, thereby guiding the discovery of truly relevant biocatalysts under specific conditions [10].

In conclusion, the continuous mining of genomes and metagenomic libraries is an established and robust strategy for expanding the enzymatic repertoire required for biotechnological applications [13]. As the cost of sequencing continues to decline and bioinformatic tools become more powerful, metagenomics will undoubtedly remain a cornerstone technique for uncovering the next generation of novel biocatalysts from the vast, untapped resource of microbial genetic diversity.

The pursuit of superior enzyme traits represents a critical frontier in industrial biotechnology, driven by growing demands for biocatalysts that remain functional under process-specific extreme conditions. Enzymes sourced from conventional organisms often prove inadequate for industrial applications requiring thermostability, pH tolerance, halotolerance, or resistance to organic solvents. Extremophilic microorganisms thriving in hostile habitats—from deep-sea hydrothermal vents to polar ice sheets—have evolved sophisticated molecular adaptations that confer exceptional stability and specificity to their enzymatic machinery [14] [15]. This technical guide examines how mining the metagenomic libraries constructed from these extreme environments provides an unparalleled resource for discovering novel biocatalysts with pre-optimized industrial traits, framing this exploration within the broader thesis that uncultured microbial diversity represents the next frontier for biocatalyst development.

The fundamental challenge in industrial enzymology lies in the fact that natural enzymes are rarely optimized for anthropogenic applications. As a result, industrial processes frequently must accommodate suboptimal catalysts rather than utilizing ideal biocatalysts designed for specific process parameters [16]. Metagenomics bypasses the limitation of microbial unculturability—a significant constraint given that less than 1% of environmental microorganisms can be cultivated using standard methodologies [16]. By directly extracting and cloning environmental DNA, researchers can access the genetic resources of entire microbial communities without requiring laboratory cultivation of constituent organisms [13]. When applied to extreme environments, this approach enables researchers to tap into evolutionary solutions refined over billions of years of adaptation to conditions that mirror industrial requirements.

Key Enzyme Traits from Extreme Environments

Enzymes sourced from extremophiles exhibit specialized structural and functional adaptations that make them particularly valuable for industrial applications. The table below summarizes the key stability traits, their industrial relevance, and exemplary extremophile sources.

Table 1: Key Enzyme Traits from Extreme Environments and Their Industrial Applications

| Trait | Molecular Determinants | Industrial Applications | Extremophile Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermostability | Increased hydrophobic cores, ionic networks, dense packing, shortened surface loops [15] | Biofuel production, starch processing, sugar syrup manufacturing [16] | Methanopyrus kandleri (122°C), Pyrococcus yayanosii (deep-sea vents) [15] |

| pH Tolerance | Specialized surface charge distributions, buffer-like amino acid clusters, stable salt bridges [14] | Food processing, pharmaceutical synthesis, effluent treatment [16] | Acidophiles (pH ~0.5), Alkaliphiles (pH ~14) [15] |

| Halotolerance | Acidic surface residue enrichment, solvation shell maintenance, osmolytes production [14] | Food fermentation, wastewater treatment, biocatalysis in ionic liquids [14] | Halobacterium salinarum (4.5M NaCl) [15] |

| Solvent Resistance | Rigid hydrophobic cores, reduced solvent accessibility, enhanced substrate binding pockets [14] | Pharmaceutical synthesis, chemical production, biodiesel manufacturing [16] | Organic solvent-tolerant microbes [14] |

| Piezostability | Reduced cavity volumes, specific amino acid substitutions, enhanced subunit interactions [15] | High-pressure bioreactors, deep-sea bioprocessing, superfluid systems [15] | Obligate piezophiles from Mariana Trench (1100 bar) [15] |

The molecular insights underlying these stability traits provide a roadmap for rational enzyme engineering. Thermophilic enzymes frequently exhibit increased hydrophobic interactions within their cores, enhanced secondary structure stabilization through additional ion pairs and hydrogen bonds, and reduced entropy of unfolding through superior packing density [15]. Halotolerant enzymes often display acidic residue enrichment on their surfaces, maintaining hydration shells and functionality in low-water-activity environments [14]. Piezophilic enzymes typically feature reduced cavity volumes and specific amino acid substitutions that counteract pressure-induced denaturation [15]. Understanding these structural principles enables researchers to prioritize certain enzyme classes or phylogenetic groups during metagenomic screening campaigns.

Metagenomic Workflow for Enzyme Discovery

The process of discovering novel biocatalysts from extreme environments involves a systematic workflow from environmental sampling to enzyme characterization, with multiple decision points influencing the success rate of identification.

Figure 1: Metagenomic workflow for enzyme discovery from extreme environments, showing key stages and decision points that influence screening outcomes.

Experimental Protocols for Key Stages

Environmental Sample Collection and DNA Extraction

Protocol: Environmental Sampling from Extreme Habitats

- Sample Collection: Collect soil, sediment, or water samples using sterile equipment. For thermal features, use heat-tolerant sampling devices. Maintain in-situ conditions during transport using insulated containers [16] [13].

- Biomass Concentration: Filter aqueous samples through 0.22μm membranes or centrifugate at 4,000×g for 15 minutes. For solid samples, use differential centrifugation after suspension in appropriate buffers [17].

- DNA Extraction: Employ commercial DNA extraction kits with modifications for extreme environmental samples:

- Add enhanced mechanical lysis step using bead beating (Lysing Matrix E, MP Biomedicals) for 45 seconds at 6 m/s [17].

- Include additional enzymatic lysis with lysozyme (10 mg/mL, 37°C for 30 minutes) and proteinase K (0.1 mg/mL, 56°C for 60 minutes).

- Implement purification steps to remove humic acids and other PCR inhibitors using gel electrophoresis and column-based clean-up [17].

- DNA Quantification and Quality Assessment: Use fluorometric methods (e.g., Qubit dsDNA HS Assay) and confirm integrity via agarose gel electrophoresis. A260/A280 ratios should be 1.8-2.0 [17].

Metagenomic Library Construction

Protocol: Library Construction with Fosmid Vectors

- DNA Fragmentation: Perform partial digestion with Sau3AI to generate 30-40 kb fragments. Optimize enzyme concentration and incubation time to maximize target size range [16].

- Vector Preparation: Digest pCC1FOS or similar fosmid vector with BamHI. Dephosphorylate with calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase to prevent self-ligation [16].

- Ligation and Packaging: Ligate insert and vector DNA at 3:1 molar ratio using T4 DNA ligase (16°C, 16 hours). Package using MaxPlax Lambda Packaging Extracts following manufacturer's protocol [16].

- Host Transformation: Transduce EPI300-T1R E. coli cells with packaged library. Plate on LB agar with 12.5 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Incubate at 37°C for 18-24 hours [16].

- Library Quality Assessment: Pick random clones to verify insert size by fosmid isolation and restriction digestion. Sequence clone ends to confirm diversity. Aim for library sizes exceeding 10^9 clones to ensure adequate coverage of complex metagenomes [16] [13].

Activity-Based Screening

Protocol: Function-Based Screening for Hydrolases

- Replica Plating: Transfer library clones to indicator plates containing substrate of interest:

- High-Throughput Screening: For soluble products, use microtiter plate-based assays with fluorescent or chromogenic substrates (e.g., p-nitrophenyl derivatives for esterases) [18].

- Hit Verification: Isolate positive clones and reconfirm activity through secondary screening. Eliminate false positives through sequence verification of inserts [16] [13].

Molecular Adaptations of Extremophilic Enzymes

Extremophilic enzymes exhibit specialized structural adaptations that confer stability under harsh conditions. Understanding these molecular mechanisms provides valuable insights for both discovery and engineering efforts.

Figure 2: Molecular adaptation pathways of extremophilic enzymes, showing how specific structural modifications confer functional benefits under extreme conditions.

The molecular adaptations depicted above manifest through quantifiable structural parameters. Thermophilic enzymes typically display a higher arginine-to-lysine ratio, as arginine forms more stable salt bridges; increased proline content in loops to reduce unfolding entropy; and a higher fraction of hydrophobic residues participating in core formation [15]. Piezophilic enzymes exhibit distinctive adaptations including reduced cavity volumes (decreased by 15-25% compared to mesophilic counterparts), enhanced secondary structure stability through additional hydrogen bonding networks, and specific amino acid substitutions that favor compact folded states [15]. Halotolerant enzymes frequently show acidic residue enrichment on their surfaces (up to 25% increase in aspartic and glutamic acids), allowing for maintenance of hydration shells in low-water-activity environments through coordinated water molecules [14]. These molecular signatures provide bioinformatic handles for prioritizing candidate genes from metagenomic datasets.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Successful mining of metagenomic libraries for novel biocatalysts requires specialized reagents, vectors, and analytical platforms. The following table details essential components of the extremophile enzyme discovery pipeline.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Enzyme Discovery

| Category | Specific Product/Platform | Application Notes | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | MPure Bacterial DNA Kit (MP Biomedicals) with Lysing Matrix E | Enhanced lysis for difficult environmental samples | Includes mechanical and enzymatic lysis steps; effective for gram-positive bacteria [17] |

| Polymerase | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity 2× Master Mix (NEB) | Metagenomic library amplification and verification | High fidelity (280× Taq); reduced amplification bias [17] |

| Cloning Vectors | pCC1FOS Fosmid Vector | Large-insert metagenomic library construction | Copy number inducible; maintains 30-40 kb inserts [16] |

| Expression Hosts | EPI300-T1R E. coli Strain | Primary fosmid library host | High transformation efficiency; inducible copy number [16] |

| Alternative Hosts | Streptomyces lividans, Rhizobium leguminosarum | Expression of GC-rich or phylogenetically distant genes | Broader promoter recognition; specialized post-translational modifications [16] |

| Sequencing Platforms | PacBio Sequel II System | Full-length 16S rRNA gene sequencing and amplicon validation | Circular consensus sequencing; >99.9% single-molecule accuracy [19] |

| Screening Assays | p-Nitrophenyl substrate series (Sigma-Aldrich) | Hydrolase activity detection in high-throughput format | Chromogenic release (400-410 nm); quantifiable kinetic data [18] |

| Analytical Tools | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Detection of novel reaction products and pathways | Untargeted analysis; complex reaction mixture resolution [18] |

The selection of appropriate reagents and platforms significantly impacts screening outcomes. For example, the choice between fosmid and plasmid vectors determines insert size and consequently the complexity of enzymatic pathways that can be captured [16]. Small-insert libraries (8-10 kb) in plasmid vectors are optimal for single-gene expression, while large-insert fosmid libraries (30-40 kb) enable capture of complete operons and multi-enzyme pathways [16]. Similarly, the selection of expression hosts substantially influences the detectable fraction of metagenomic diversity; while E. coli remains the most common host, alternative hosts such as Streptomyces spp. or Rhizobium leguminosarum have demonstrated the ability to express genes refractory to expression in E. coli, expanding the discoverable enzyme space [16] [13].

Emerging Approaches and Future Directions

The field of metagenomic enzyme discovery is rapidly evolving through integration of computational and synthetic biology approaches. Artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms are increasingly employed to predict enzyme function from sequence data, prioritizing candidates for experimental characterization [14]. Sequence-based mining of metagenomic data now leverages conserved catalytic residues and structural motifs to identify novel enzyme families, while activity-based screening continues to yield unexpected catalysts with no sequence homology to known enzymes [13].

Advanced screening methodologies are addressing the critical bottleneck in metagenomic analysis. Substrate-induced gene expression screening (SIGEX) uses fluorescence-activated cell sorting to identify clones harboring catabolic genes induced by target substrates [13]. Meanwhile, microfluidics-based screening platforms enable ultra-high-throughput analysis of enzyme activities at picoliter scales, dramatically increasing screening efficiency [18]. These technological advances, combined with the systematic exploration of Earth's most extreme environments, promise to unlock a wealth of novel biocatalysts with precisely tuned properties for industrial applications.

The integration of synthetic biology with metagenomic screening represents a particularly promising direction. Engineering host strains with enhanced capabilities for heterologous expression—through chromosome integration of rare tRNA genes, modification of secretion pathways, or implementation of broad-specificity transcriptional regulators—can significantly increase the hit rate from metagenomic libraries [16]. As these methodologies mature, mining the metagenomic resource for superior enzyme traits will increasingly yield biocatalysts with the stability, specificity, and activity required for transformative industrial applications.

The vast majority of the Earth's microbial diversity remains unexplored due to a fundamental limitation in microbiology: it is estimated that up to 99% of bacteria in the environment cannot be readily cultured in laboratory conditions [3] [20]. This uncultured microbial majority represents an immense reservoir of potentially useful biocatalysts and natural products that have never been characterized. Metagenomics provides a culture-independent solution to this problem by enabling researchers to access the genomic potential of entire microbial communities directly from environmental samples. This approach involves extracting environmental DNA (eDNA) directly from samples and cloning this genetic material into culturable host organisms for expression and screening [3]. The field has evolved substantially from its beginnings, driven by advances in sequencing technologies and bioinformatics, transforming into a mature technology for discovering novel enzymes and biosynthetic pathways with applications across chemical, pharmaceutical, and industrial sectors [21] [6].

The strategic importance of metagenomics in biocatalysis continues to grow as industries commit to more sustainable manufacturing processes. Biocatalysis offers significant advantages over traditional chemical methods, including reactions conducted in aqueous media under mild conditions, high regio- and enantio-selectivity, and reduced environmental footprint [6]. Metagenome mining has proven particularly valuable for rapidly expanding the toolkit of promiscuous enzymes needed for new transformations, often without requiring initial protein engineering steps. When engineering is necessary, metagenomic candidates frequently provide superior starting points compared to previously known enzymes, as they originate from natural selection pressures in native environments [6]. This review comprehensively examines the methodologies, discoveries, and industrial applications stemming from metagenomic explorations of natural product pathways, with particular focus on the workflow from environmental sample to commercially viable biocatalyst.

Methodological Approaches for Biocatalyst Discovery

Metagenomic Library Construction and Screening Strategies

The process of discovering novel biocatalysts through metagenomics follows a structured workflow that begins with environmental sampling and culminates in the identification of promising enzyme candidates. The initial critical step involves sample processing and DNA extraction from diverse environments, which can range from ordinary soils to extreme habitats like hot springs or deep-sea vents [6]. These extreme environments are particularly valuable sourcing locations, as they often yield enzymes with superior stability and activity under process conditions that would denature most conventional biocatalysts [6]. The extracted environmental DNA is then sequenced using next-generation sequencing platforms, with the resulting data processed through elaborate bioinformatics tools and software for analyzing large metagenomic datasets [6].

Two primary screening approaches have been established for interrogating metagenomic libraries: sequence-based screening and functional screening [3] [6]. Sequence-based screening relies on known sequences of target gene families, searching based on homology or conserved motifs. This method uses computational tools to identify hits from conserved regions of target proteins, narrowing the search for metagenomic enzymes [6]. In contrast, functional screening does not require prior sequence knowledge and directly tests for desired enzymatic activities, often leading to the discovery of more novel gene sequences in any given sample [6]. Functional screening can be further divided into several methodologies:

- Simple direct readout assays: Libraries are plated on media containing a substrate for an enzyme of interest, and clones producing the desired enzyme are identified by formation of a clear halo or color change [3].

- Reporter gene assays: These utilize product-induced gene expression (PIGEX) where the production of a metabolite of interest activates a promoter controlling a reporter gene, enabling fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of active clones [3].

- Complementation assays: These employ host strains with deletions in specific metabolic pathways, where the metagenomic DNA complements the mutation and allows growth on selective media [3].

The following diagram illustrates the core metagenomic workflow for biocatalyst discovery from environmental samples to enzyme identification:

Functional Metaproteomics as a Discovery Tool

A complementary approach to traditional metagenomic screening is functional metaproteomics, which combines activity-based screening with metagenome-based protein identification. This method enables the direct discovery of biocatalytic activity in the proteome of an environmental sample without the bias of sequence-based hypotheses. A demonstrated workflow involves separating proteins from an environmental sample using two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, followed by an in-gel activity assay using fluorogenic substrates like para-methylumbelliferyl butyrate (pMUB) [20]. Lipolytic enzymes present in the gel hydrolyze pMUB and release a fluorescent dye detectable under ultraviolet light, identifying active protein spots that can be excised, tryptically digested, and analyzed by mass spectrometry [20].

The power of this approach lies in its connection to metagenomic data. A customized protein database created from sequenced metagenomic DNA from the same sample enables identification of the active enzymes through mass spectrometric analysis. This method proved successful in identifying novel esterases from oil-contaminated soil samples, including the discovery and subsequent heterologous expression of ML-005, a previously uncharacterized esterase with activity toward short- and medium-chain length esters [20]. The functional metaproteomics approach maintains the immediacy of activity-based screening while harnessing the phylogenetic diversity of environmental samples.

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Functional Screening Protocol for Hydrolase Discovery:

- Sample Preparation: Collect environmental samples (e.g., oil-contaminated soil) and extract proteins using appropriate extraction buffers. Maintain samples at 4°C throughout processing to prevent protein degradation [20].

- Electrophoresis Separation: Separate 600μg of protein sample by two-dimensional polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The first dimension separates proteins by isoelectric point, while the second dimension separates by molecular weight [20].

- In-Gel Activity Assay: After electrophoresis, refold proteins in the gel and incubate with fluorogenic substrate (e.g., 0.1mM para-methylumbelliferyl butyrate in 50mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). Detect active spots under ultraviolet light at 365nm [20].

- Protein Identification: Excise active protein spots, digest with trypsin, and analyze by mass spectrometry. Search fragmentation spectra against a customized metagenome database derived from the same environmental sample [20].

- Heterologous Expression: Synthesize DNA sequences coding for identified enzymes and clone into expression vectors (e.g., pET-based systems with T7-promoters). Express in suitable hosts like Escherichia coli BL21 and validate activity through enzyme assays with appropriate substrates [20].

Sequence-Based Screening Protocol:

- DNA Extraction and Sequencing: Extract high-molecular-weight DNA from environmental samples using standardized kits. Sequence using next-generation platforms (Illumina, PacBio) aiming for Phred scores >35 indicating base call accuracy >99.99% [20].

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Assemble raw sequencing data using software such as SPAdes. Annotate assembled metagenome using PROKKA, which identifies coding sequences and transfers annotations from hierarchical data sources [6].

- Homology Screening: Use BLAST searches with known enzyme sequences as queries to identify homologs in the metagenomic database. Focus on conserved catalytic motifs and domains characteristic of the enzyme family of interest [3] [6].

- Gene Cloning and Expression: Amplify candidate genes using PCR with designed primers and clone into expression vectors. Screen for activity in crude lysates or purified protein preparations [3].

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Biocatalyst Discovery

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorogenic Substrates | Detection of enzyme activity in functional screens | para-methylumbelliferyl butyrate (pMUB) for lipases/esterases [20] |

| Metagenomic Libraries | Source of novel genetic material for screening | Soil, marine, or extreme environment-derived DNA clones in bacterial hosts [3] |

| Expression Vectors | Heterologous production of candidate enzymes | pET vectors (T7 promoter), pBR322-based (tac promoter) with His-tags [20] |

| Host Strains | Expression of metagenomic DNA | Escherichia coli BL21 for protein production, specialized strains for pathway expression [20] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Analysis of sequence data and identification of candidates | SPAdes (assembly), PROKKA (annotation), BLAST (homology searches) [6] [20] |

| Activity Assay Reagents | Validation and characterization of enzyme function | p-nitrophenyl esters with varying chain lengths for esterase/lipase characterization [20] |

Discovered Biocatalyst Classes and Their Industrial Applications

Metagenomic approaches have yielded numerous industrially valuable enzymes with diverse applications. Hydrolases represent one of the most successfully discovered classes, with lipases and esterases being particularly prominent. These enzymes catalyze the hydrolysis of ester bonds and have applications in detergents, food processing, and biofuel production. The metagenomically discovered esterase ML-005, identified through functional metaproteomics, demonstrates high activity toward short-chain (C4) and medium-chain (C8) esters, classifying it as an esterase with potential applications in flavor compound synthesis and bioconversions [20]. Other significant hydrolase discoveries include proteases with applications in the laundry industry, where alkaline proteases active under harsh detergent conditions have been identified through metagenomic mining of alkaline environments [3].

Glycosyl hydrolases including cellulases, amylases, and pectinases have been discovered from metagenomic libraries derived from various environments. For example, novel cellulase genes have been identified from metagenomic libraries of compost soils, with potential applications in biomass degradation for biofuel production [3]. Similarly, oxidoreductases such as laccases and peroxidases have been found through functional screening of soil metagenomic libraries, with applications in pulp bleaching, dye decolorization, and bioremediation [22]. The expansion of available enzyme classes through metagenomic mining continues to provide industrial biocatalysis with new tools for sustainable manufacturing processes.

Small Molecule Products from Biosynthetic Pathways

Beyond single enzymes, metagenomics provides access to complete biosynthetic pathways for valuable small molecules. Nonribosomal peptides and polyketides represent two major classes of bioactive compounds that have been successfully discovered through metagenomic approaches. These complex molecules are synthesized by modular enzyme complexes—nonribosomal peptide synthetases (NRPS) and polyketide synthases (PKS)—which have been targeted through homology-based screening of metagenomic libraries [3].

Several notable successes exemplify this approach:

Glycopeptide Antibiotics: Using degenerate primers based on OxyC, a conserved oxidative coupling enzyme found in vancomycin and teicoplanin-like glycopeptide gene clusters, researchers have identified and recovered multiple predicted glycopeptide-encoding gene clusters from soil metagenomic libraries [3]. This approach demonstrates how key conserved enzymes in biosynthetic pathways can serve as entry points for discovering new members of clinically relevant antibiotic families.

Cyanobactins: These ribosomally produced cyclic peptides, frequently displaying cytotoxic activities, have been discovered through metagenomic analysis of uncultured cyanobacterial symbionts associated with marine sponges. The biosynthetic gene clusters for cyanobactins like patellamide were cloned and heterologously expressed from metagenomic libraries, enabling production and characterization of these compounds without cultivating the original producer organisms [3].

Type II Polyketides: A structurally diverse collection of aromatic small molecules, including antimicrobial and anticancer agents (e.g., tetracycline and doxorubicin), arise from iterative Type II polyketide synthases. These pathways have been discovered through PCR screening for the conserved ketosynthase genes that form the minimal PKS required for polyketide chain assembly [3].

ET-743 Anticancer Agent: The biosynthetic cluster for the anticancer agent ET-743 was recovered from a metagenomic library of uncultured tunicate bacterial symbionts. This discovery was guided by parallels between ET-743 and other tetrahydroisoquinoline structures, leading researchers to hypothesize a bacterial origin encoded by a non-ribosomal peptide synthase system [3].

The following diagram illustrates the primary screening methodologies and their application in discovering different biocatalyst types:

Industrial Performance and Key Metrics

The translation of metagenomically discovered biocatalysts to industrial applications requires meeting specific performance metrics that determine economic viability. Industrial biocatalysis demands high space-time-yield (STY), typically exceeding 16 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹ for commercial processes, along with high substrate loadings (>160 g L⁻¹) and low catalyst consumption (<1 g L⁻¹) [21]. Through enzyme engineering and process optimization, metagenomically discovered enzymes can achieve these targets, as demonstrated by Codexis' development of a ketoreductase for pharmaceutical synthesis that progressed from an initial STY of 3.3 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹ to a final STY of 20 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹ [21].

The economic advantages of enzymatic processes often extend beyond the reaction itself to include downstream processing benefits. A notable example is the enzymatic synthesis of emollient esters (e.g., myristyl myristate) developed by Evonik, where an immobilized lipase operating at 60-80°C replaced a chemical process running at >180°C [21]. While the enzyme itself was relatively expensive, the milder operating conditions prevented formation of smelly and colored by-products, eliminating the need for costly deodorization and bleaching steps required in the chemical process [21]. This case highlights how considering the entire process rather than just the transformation step can make enzymatic routes economically attractive despite higher catalyst costs.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Industrial Biocatalysis Applications

| Application | Key Performance Indicators | Achieved Metrics | Economic/Business Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide Production | Space-time-yield (STY), Product titer | STY: >0.1 kg L⁻¹ h⁻¹, Product concentration: >500 g L⁻¹ [21] | Large-scale industrial process using nitrile hydratase from Rhodococcus rhodochrous J1 [21] |

| Pharmaceutical Synthesis (KRED) | Substrate loading, Catalyst loading, STY | Substrate: 160 g L⁻¹, Catalyst: 0.9 g L⁻¹, STY: 20 g L⁻¹ h⁻¹ [21] | Efficient production of chiral alcohols for APIs; meets commercial targets [21] |

| Emollient Ester Synthesis | Energy consumption, By-product formation, Downstream processing | Temperature: 60-80°C (vs. >180°C for chemical process), minimal by-products [21] | Eliminates need for deodorization and bleaching steps; overall cost savings despite enzyme cost [21] |

| Esterase ML-005 | Substrate specificity, Reaction validation | Activity toward C4 and C8 esters, no activity toward C16 esters [20] | Potential application in flavor compound synthesis and bioconversions [20] |

Future Perspectives and Emerging Technologies

The future of metagenomic biocatalyst discovery is being shaped by several emerging technologies that address current limitations and expand the scope of discoverable enzymes. Single-cell genomics represents a powerful complementary approach, where individual bacterial cells are isolated from complex microbial communities and subjected to multiple displacement amplification (MDA) to obtain sufficient genomic DNA for sequencing [3]. This method has been used successfully to isolate and sequence single cells of Lyngbya bouillonii from cyanobacterial filaments containing symbiotic bacteria, leading to the identification of novel secondary metabolite pathways [3]. The combination of single-cell genomics with metagenomic data provides a more comprehensive view of microbial community functional potential.

Advances in sequencing technologies and bioinformatics tools continue to accelerate the discovery process. The significant reduction in sequencing costs has transformed microbial ecology studies by simplifying genome elucidation and enabling more comprehensive metagenomic analyses [6]. However, the exploration of these data remains computationally demanding and typically requires expertise in bioinformatics tools for processing large sequence sets [6]. The emergence of machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches promises to further streamline enzyme discovery and engineering, though these methods still require substantial data collection to generate reliable models [6].

The Nagoya Protocol on "Access to Genetic Resources and the Fair and Equitable Sharing of Benefits Arising from their Utilization (ABS)" represents an important regulatory framework with significant implications for metagenomic biocatalyst discovery [6]. Implemented in 2014, this protocol aims to prevent biopiracy by ensuring fair and equitable benefits from the use of genetic resources between countries. However, grey areas remain regarding collaborative working and publishing information to online databases, particularly concerning whether regulations cover only physical organisms or also digital sequence information (DSI) [6]. Researchers engaged in metagenomic discovery must remain aware of these legal and ethical considerations when sourcing environmental samples from different geographical locations.

Future developments will likely focus on improving heterologous expression systems for more efficient screening of metagenomic libraries, developing better bioinformatic tools for predicting enzyme function from sequence data, and integrating metagenomic discovery with directed evolution to optimize identified catalysts for industrial applications. As these technologies mature, metagenomic mining will continue to expand the toolbox of available biocatalysts, driving innovation in sustainable industrial processes and pharmaceutical development.

From Sample to Sequence: Methodologies for Mining and Applying Novel Enzymes

The pursuit of novel biocatalysts from uncultured microorganisms is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology, supporting the development of new enzymes for applications in pharmaceutical synthesis, industrial biotechnology, and bio-based sustainable manufacturing [6] [16]. Metagenomics enables researchers to access the vast genetic reservoir of environmental microorganisms, over 99% of which resist standard laboratory cultivation techniques [23] [16]. This technical guide provides an in-depth overview of the critical workflow for constructing metagenomic libraries from environmental samples, framed within the context of mining for novel biocatalysts. We detail standardized methodologies for environmental sampling, nucleic acid isolation, and library construction, providing researchers with a robust framework for biocatalyst discovery.

Sample Collection and Processing

Strategic Sampling and Preservation

The initial sampling strategy must consider the ecological context of the desired biocatalytic activity. Samples from environments with high substrate exposure (e.g., soil contaminated with cooking oil for lipase discovery) often enrich for microorganisms possessing the target activity [20]. To ensure representative sampling of the microbial community:

- Sample Volume and Replication: Collect from multiple points within a sampling site and combine to create a composite sample. Gather 6-10 technical replicates to account for heterogeneity and serve as controls [24].

- Sterile Technique: Use sterile disposable tools or thoroughly sterilize equipment between samples to prevent cross-contamination [24].

- Immediate Processing: Process samples immediately after collection when possible. Alternatively, flash-freeze samples in liquid nitrogen and store at -80°C to preserve nucleic acid integrity [25]. Freeze-thaw cycles should be minimized as they can significantly reduce DNA yield [26].

Sample Pre-processing

Various pre-processing techniques can enhance DNA extraction efficiency and quality:

- Debris Removal: For soil and sediment samples, remove large particulate matter using a mesh sieve or coffee filter [24].

- Microbial Concentration: For aquatic samples, filter through membranes (e.g., 0.45 μm cellulose nitrate or 0.7-1.2 μm glass microfiber) to concentrate microbial biomass [24].

- Host DNA Depletion: When targeting microbial communities associated with host organisms (e.g., gut microbiomes), implement physical fractionation or selective lysis to minimize host DNA contamination [27].

Table 1: Common Filtration Methods for Liquid Samples

| Filter Material | Pore Size | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|

| Cellulose Nitrate | 0.45 μm | Capturing a wide range of microbes of various sizes [24] |

| Glass Microfiber (GF/F) | 0.7 μm | Target microbes of 0.6-0.8 μm; rapid flow rate [24] |

| Glass Microfiber | 1.2 μm | Samples with high concentrations of particulate/gelatinous substances [24] |

Metagenomic DNA Isolation

The primary goal of DNA extraction is to obtain high-molecular-weight (HMW), high-purity DNA that accurately represents the total microbial community. The choice of extraction method significantly impacts DNA yield, fragment length, and community representation [27].

Extraction Methodologies

Two principal approaches exist for environmental DNA extraction:

- Direct Lysis: Cells are lysed directly within the environmental matrix. This method typically yields higher DNA quantities but co-extracts humic substances and other enzymatic inhibitors, giving the DNA a brownish coloration [23] [27]. Direct lysis may also recover extracellular DNA.

- Indirect Lysis: Microbial cells are first separated from the environmental matrix (e.g., via centrifugation or filtration) before lysis. This method yields purer DNA with fewer contaminants but may underrepresent species that adhere strongly to particles [27].

Bead-beating is highly recommended for complete cell lysis, particularly for robust Gram-positive bacteria and spores, as it recovers more diverse microbial DNA compared to purely enzymatic or chemical lysis [24].

Technical Protocols

Direct Lysis Method (for soil samples) [23]:

- Mix 50 g of environmental sample with 135 ml of DNA extraction buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 100 mM sodium EDTA, 100 mM sodium phosphate, 1.5 M NaCl, 1% CTAB).

- Add 1 ml of proteinase K (10 mg/ml) and incubate with shaking at 37°C for 30 min.

- Add 15 ml of 20% SDS and incubate at 65°C for 2 hours with gentle inversion every 20 min.

- Centrifuge and collect supernatant.

- Combine supernatants from multiple extraction cycles and mix with an equal volume of chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (24:1).

- Precipitate DNA from the aqueous phase with 0.6 volumes of isopropanol.

- Purify the crude DNA from co-extracted humic acids using commercial purification kits (e.g., Wizard Plus Minipreps DNA Purification System).

Critical Cleanup Techniques: Humic acid contamination can inhibit downstream enzymatic reactions. Effective purification methods include:

- Guanidinium Thiocyanate-Phenol-Chloroform extraction [24]

- Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) extraction [24] [25]

- Commercial kits specifically designed for environmental samples (e.g., FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil) [24]

DNA Quality Assessment and Quantification

Accurate quantification and quality assessment are essential for successful library construction:

- Spectrophotometry: Measure absorbance at A260/A280 and A230/A260 ratios. Ideal A260/A280 should exceed 1.7 for DNA, and A230/A260 indicates potential contamination from guanidine salts or other impurities [24].

- Fluorometric Quantitation: Use dye-based methods (e.g., Qubit) for more accurate DNA concentration measurements as they are less affected by contaminants [26].

- Fragment Analysis: Verify DNA integrity and fragment size using agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8%) or advanced systems (e.g., BioAnalyzer) [26] [25]. High-quality DNA should show a dominant band above 10-23 kb [26].

Table 2: DNA Extraction Kit Performance Comparison [26]

| Extraction Kit | Average DNA Yield | Key Characteristics | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mag-Bind Universal Metagenomics Kit (OM) | Higher | Higher mapping rates, more genes detected | Most sample types, especially when yield is critical |

| DNeasy PowerSoil Kit (QP) | Lower | Robust performance, widely used | Standard soil samples |

Library Construction and Quality Control

Library construction involves fragmenting the environmental DNA, attaching platform-specific adapters, and preparing the library for sequencing. The chosen strategy depends on the target of the biocatalyst discovery campaign [16].

Vector and Host Selection

- Small-insert libraries (plasmids, lambda phage): Ideal for screening single genes or small operons (inserts up to 8 kb). Most genes are under the control of vector promoters, facilitating heterologous expression in the host [23] [16].

- Large-insert libraries (fosmids, cosmids, BACs): Essential for capturing large biosynthetic gene clusters or multi-enzyme assemblies (inserts up to 40 kb). Fosmids use the F-plasmid origin and are maintained in E. coli with high stability [16].

Escherichia coli remains the predominant host for metagenomic library construction due to well-established genetic tools, high transformation efficiency, and extensive experience with heterologous expression [23] [16]. However, only ~40% of enzymatic activities may be detected in E. coli due to differences in gene expression and protein folding between prokaryotic taxa [16]. Alternative hosts such as Streptomyces spp., Rhizobium leguminosarum, and other Proteobacteria can expand the range of detectable activities [16].

Library Preparation Workflow

A standard library preparation workflow includes:

- DNA Fragmentation: Achieved mechanically (e.g., acoustic shearing) or enzymatically to create uniformly sized fragments. The shearing speed and duration can be adjusted to obtain the desired insert size [24].

- Size Selection: Perform sucrose density gradient centrifugation or use bead-based size selection to isolate fragments of the desired length (e.g., >2 kb) [23].

- Adapter Ligation: Use DNA ligase to attach platform-specific adapters containing barcodes for sample multiplexing.

- Library Amplification: Employ a proofreading polymerase for limited-cycle PCR to amplify the library, minimizing errors that could inflate diversity estimates [24]. The KAPA Hyper Prep Kit has demonstrated superior performance in detecting more genes compared to transposase-based methods [26].

- Quality Control: Assess the final library concentration via qPCR and fragment size distribution using a BioAnalyzer System [24].

Library Size and Input Considerations

- Library Size: For functional screening, create libraries with 10^3 to >10^5 clones to maximize diversity while maintaining practical screening capacity [28].

- DNA Input: While 250 ng is a common starting amount, studies show no significant difference in metagenomic profiling between 50 ng and 250 ng inputs for library preparation, enabling work with low-yield samples [26].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Metagenomic Library Construction

| Reagent/Kit | Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| FastDNA SPIN Kit for Soil | DNA isolation from environmental samples | Effective removal of humic acids; includes lysing matrix tubes [24] |

| Mag-Bind Universal Metagenomics Kit | High-yield DNA extraction | Omega Bio-tek kit that outperforms others in yield and gene detection [26] |

| KAPA Hyper Prep Kit | High-throughput library construction | Produces libraries with higher detected gene numbers vs. transposase methods [26] |

| SurePRIME DNA Polymerase | "Hot-start" PCR amplification | High-fidelity polymerase suitable for contaminated templates [24] |

| pBluescript SK+ | Cloning vector for small-insert libraries | Used with E. coli DH5α for maintaining environmental DNA inserts [23] |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow from sample collection to biocatalyst discovery:

A robust workflow for environmental sampling, DNA extraction, and library construction is fundamental to successful biocatalyst discovery from metagenomic libraries. Methodological choices at each stage—from selecting an environment with high enzymatic potential to optimizing DNA extraction and library construction protocols—significantly impact the diversity and quality of the resulting biocatalyst collection. By implementing standardized, reproducible methods and employing appropriate quality controls, researchers can maximize their chances of discovering novel enzymes with valuable applications in biotechnology and drug development. The integration of synthetic biology approaches, alternative expression hosts, and functional screening methods will continue to expand our access to the vast catalytic potential of uncultured microorganisms.

The relentless pursuit of novel enzymes for industrial, therapeutic, and environmental applications has pushed the boundaries of traditional microbiology. Conventional cultivation methods fail to access the vast majority of microbial diversity, with over 99% of microorganisms in most environments remaining unculturable [13] [29]. This limitation has propelled metagenomics—the direct analysis of genetic material recovered from environmental samples—to the forefront of biocatalyst discovery. Within this field, two principal strategies have emerged: functional screening and sequence-based mining. These approaches represent fundamentally different philosophies in the hunt for novel enzymes, each with distinct advantages, limitations, and technological requirements. This guide provides a comprehensive technical comparison of these methodologies, framed within the context of mining metagenomic libraries for novel biocatalysts, to equip researchers with the knowledge needed to select and implement the optimal strategy for their specific research objectives.

The significance of this field is underscored by the immense biotechnological potential locked within uncultured microorganisms. A single gram of soil may contain up to 10^8 different biocatalysts, highlighting the vast inventory of biological functions accessible through metagenomic approaches [16]. Effectively mining this resource is crucial for developing greener industrial processes, novel therapeutic agents, and solutions for environmental sustainability.

Core Principles and Fundamental Differences

Functional Screening: Activity-Driven Discovery

Functional screening is a phenotype-based approach that identifies clones expressing desired enzymatic activities through direct biochemical assays. This method involves extracting environmental DNA, cloning it into a surrogate host (typically Escherichia coli), and screening the resulting metagenomic libraries for specific catalytic functions [30] [31]. The core strength of this approach lies in its ability to discover entirely novel enzymes without prior sequence knowledge, including those with no homology to known protein families [32] [13]. This makes it particularly valuable for exploring uncharted sequence space and identifying new structure-function relationships.

A key advantage of functional screening is that it provides direct confirmation of enzyme activity and can yield immediate insights into substrate specificity and kinetic parameters [33]. Furthermore, it identifies complete, functional genes rather than partial fragments, facilitating subsequent biochemical characterization [32]. However, this approach is often limited by biased gene expression in heterologous hosts, where genetic elements from environmental microbes may not be properly recognized by the host's transcriptional and translational machinery [30] [16]. Additionally, functional screening is typically labor-intensive, time-consuming, and low-throughput compared to sequence-based methods, often requiring the screening of thousands to hundreds of thousands of clones to identify rare activities [31].

Sequence-Based Mining: Homology-Driven Discovery

Sequence-based mining relies on the identification of candidate genes through their similarity to known sequences. This approach utilizes either hybridization with oligonucleotide probes or PCR amplification with degenerate primers designed from conserved regions of already characterized enzymes [30] [31]. With the advent of high-throughput sequencing technologies, this strategy has evolved to include in silico screening of metagenomic datasets using bioinformatic tools to identify genes of interest based on sequence homology [13] [31].

The principal advantage of sequence-based approaches is their high throughput and scalability; millions of sequences can be rapidly analyzed computationally once metagenomic data is generated [31]. This method is particularly effective for identifying novel variants of well-characterized enzyme families, expanding the functional diversity within known protein lineages. However, sequence-based mining is inherently limited by its dependence on existing sequence databases, making it unable to discover enzymes with entirely novel folds or catalytic mechanisms that share no significant sequence similarity with known proteins [13] [30]. Another significant limitation is that it identifies candidate genes based on sequence alone, requiring subsequent cloning and expression to confirm actual enzymatic activity [32].

Table 1: Core Characteristics Comparison

| Parameter | Functional Screening | Sequence-Based Mining |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of Discovery | Enzyme activity | Sequence homology |

| Dependence on Prior Knowledge | Low | High |

| Novelty of Discoveries | Novel folds & mechanisms | Novel variants of known families |

| Throughput | Low to medium | High to very high |

| Key Limitation | Host-dependent expression bias | Limited to known sequence space |

| Direct Activity Confirmation | Yes | No (requires expression) |

| Typical Hit Rate | ~0.26% (for various hydrolases) [33] | Varies by enzyme family |

Methodological Deep Dive: Experimental Protocols

Functional Screening Workflow

Library Construction

Functional screening begins with the extraction of high-quality environmental DNA from complex samples such as soil, compost, marine sediments, or animal guts [34] [29]. The DNA is then fragmented and cloned into suitable expression vectors. For individual genes or small operons, small-insert libraries (plasmids, λ-phage; inserts up to 8 kb) are preferred as they place cloned genes under the control of strong vector promoters [16]. For larger gene clusters or pathway mining, large-insert libraries (fosmids, cosmids; inserts up to 40 kb) are constructed [34] [32] [16]. The choice of vector and host significantly impacts screening success, with E. coli being the most common but not always optimal host for expressing genes from diverse phylogenetic origins [16].

High-Throughput Screening Assays

Advanced screening methodologies have dramatically improved the throughput and sensitivity of functional screens. Multiplexed assays using fluorogenic and chromogenic substrates enable simultaneous screening of thousands of clones for multiple activities [33]. For example, one developed platform can screen 12,160 clones for 14 different enzymatic activities in a total of 170,240 reactions, significantly accelerating the discovery process [33].

Solid media assays remain popular for their simplicity and scalability, where clones are plated on agar containing substrate indicators. For instance, esculin-containing media can identify β-glucosidase activity through the formation of dark halos around positive clones [34]. However, solution-based assays offer superior quantification and sensitivity, particularly when coupled with automated liquid handling systems [33].

Innovative methods continue to emerge, including functional metaproteomics that combines 2D gel electrophoresis with zymography to directly detect active enzymes from environmental samples, followed by identification via mass spectrometry and metagenome database mining [20]. This approach bypasses cloning biases and directly links activity to protein sequence.

Sequence-Based Mining Workflow

Metagenome Sequencing and Assembly

Sequence-based approaches begin with metagenomic DNA extraction, followed by high-throughput sequencing using platforms such as Illumina, PacBio, or Oxford Nanopore [34] [31]. The resulting sequences are assembled into contigs using tools like SPAdes, and open reading frames are predicted with programs such as Prodigal [20] [31]. For targeted sequencing of specific gene families, PCR amplification with degenerate primers designed from conserved regions remains a valuable approach [30].

In Silico Screening and Annotation

The predicted protein sequences are then searched against curated databases such as CAZy (for carbohydrate-active enzymes) or MEROPS (for proteases) using tools like BLAST, HMMER, or DIAMOND [34] [31]. Advanced machine learning approaches are increasingly being employed to predict enzyme function based on sequence-derived features, while structural modeling with tools like AlphaFold2 provides insights into catalytic mechanisms and substrate specificity [31]. Genomic context analysis, such as identifying genes located within polysaccharide utilization loci, can further support functional predictions [31].

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making process for selecting between these two fundamental approaches:

Comparative Analysis: Performance and Applications

Efficiency and Success Rates