Multi-Enzyme Cascade Reactions: Design, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the design and application of multi-enzyme cascade reactions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Multi-Enzyme Cascade Reactions: Design, Optimization, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the design and application of multi-enzyme cascade reactions for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of enzyme cascades, including their ability to minimize purification steps, shift unfavorable equilibria, and handle unstable intermediates. The content covers advanced methodological strategies such as modular pathway design, enzyme scaffolding, and cofactor regeneration, illustrated with recent applications in synthesizing non-canonical amino acids, rare sugars, and pharmaceutical precursors. It details systematic troubleshooting and optimization approaches to overcome incompatibility challenges and enhance cascade performance. Finally, the article presents validation frameworks and comparative analyses of cascade efficiency, offering a holistic resource for implementing these powerful biocatalytic systems in biomedical research and industrial biomanufacturing.

The Fundamentals of Multi-Enzyme Cascades: Principles and Potentials

Defining Multi-Enzyme Cascade Reactions and Core Mechanisms

Multi-enzyme cascade reactions represent an advanced biocatalytic strategy wherein two or more enzymes are integrated to perform consecutive transformations in a single reaction vessel. These systems mirror the efficiency of natural metabolic pathways, enabling the synthesis of complex molecules from simple, inexpensive precursors without the need for intermediate isolation [1]. The core mechanism hinges on the seamless transfer of reaction intermediates between enzymatic active sites, a process that can be significantly enhanced through strategic spatial organization of the enzymes [2] [3]. By leveraging techniques such as enzyme co-immobilization and scaffold-free assembly, these cascades achieve high atomic economy, minimize waste generation, and improve overall reaction kinetics, making them exceptionally valuable for sustainable chemical synthesis and pharmaceutical development [4] [1].

The design of these systems is a cornerstone of modern synthetic biology and biocatalysis research, framed within a broader thesis of optimizing metabolic flux and reaction efficiency. For researchers and drug development professionals, mastering these mechanisms is key to developing greener, cost-effective routes for producing high-value compounds, including non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs), pharmaceutical intermediates, and sugar alcohols [4] [5].

Table 1: Defining Characteristics of Multi-Enzyme Cascade Systems

| Characteristic | Conventional Multi-Step Processes | Multi-Enzyme Cascade Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Reaction Vessels | Multiple vessels required for each step | Single pot for all reactions |

| Intermediate Handling | Requires purification and isolation between steps | No intermediate purification needed |

| Atomic Economy | Often lower due to protection/deprotection steps | Typically high (>75% reported in ncAA synthesis) [4] |

| Byproduct Generation | Higher, due to separate workup for each step | Minimized (water reported as the sole byproduct in some systems) [4] |

| Thermodynamic Control | Challenging to manage equilibrium for each step | Unfavorable equilibria can be overcome by coupling reactions [1] |

Core Mechanisms and Quantitative Performance

The enhanced performance of multi-enzyme cascades is governed by several interdependent core mechanisms. Spatial Compartmentalization is a foundational principle, where enzymes are strategically positioned in close proximity to facilitate the direct channeling of intermediates from one active site to the next. This proximity minimizes diffusion delays, reduces the loss of unstable intermediates, and protects the pathway from cross-talk within complex cellular environments [2]. Cofactor Regeneration is another critical mechanism, particularly for oxidoreductase-dependent cascades. Instead of adding stoichiometric amounts of expensive cofactors like NAD(P)H, integrated enzyme systems regenerate these molecules in situ, making processes commercially viable and sustainable [6].

Quantitative data from recent studies underscores the efficiency gains achieved through these mechanisms. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from established cascade systems.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Selected Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Target Product | Cascade Enzymes | Key Metric | Reported Performance | Source/System |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) | AldO, G3K, PGDH, PSAT, OPSS | Production Scale | Gram- to decagram-scale in a 2 L reactor [4] | Glycerol-based cascade [4] |

| Sorbitol | S6PDH-M4, S6PDP, GDH | Product Yield | 82.6 mM from 200 mM F6P (41% conversion) [5] | In vitro system from F6P [5] |

| 2′3′-cGAMP | ScADK, AjPPK2, SmPPK2, thscGAS | Overall Molar Yield | 0.08 mol 2′3′-cGAMP per mol adenosine [1] | ATP synthesis coupled cascade [1] |

| SHCHC (Menaquinone pathway) | MenD, MenH | Rate Enhancement | ~40% more product vs. free enzyme mixture [3] | RIAD/RIDD enzyme assembly [3] |

| Carotenoids | Idi, CrtE | Production Increase | 5.7-fold increase in E. coli [3] | In vivo scaffold-free assembly [3] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Establishing a Scaffold-Free Enzyme Assembly In Vitro

This protocol details the formation of a multienzyme complex using the RIAD and RIDD peptide tags, as demonstrated for the menaquinone biosynthetic enzymes MenD and MenH [3].

- Step 1: Genetic Construction. Fuse the RIAD or RIDD peptide tag to the C-terminus of the target enzymes (e.g., MenD, MenH) using a flexible linker, typically (GGGGS)₃. Construct variants with one or two tags as needed (e.g., MenD-RA, MenD-RA2, MenH-RD).

- Step 2: Protein Expression and Purification.

- Transform expression plasmids (e.g., pET-28a) into a suitable E. coli strain like BL21(DE3).

- Grow cultures in TB medium with appropriate antibiotics at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.6-0.8.

- Induce protein expression with 0.2-0.5 mM IPTG and incubate at 16°C for 18-24 hours.

- Harvest cells by centrifugation, resuspend in lysis buffer (e.g., 10-50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5), and disrupt via sonication.

- Clarify the lysate by centrifugation and purify the tagged enzymes using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA resin).

- Step 3: Enzyme Assembly.

- Mix the purified RIAD- and RIDD-tagged enzymes in the desired stoichiometry in an appropriate assay buffer.

- The strong affinity (K_D ≈ 1.2 nM) between RIAD and RIDD drives spontaneous self-assembly into complexes.

- Confirm assembly using techniques such as native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC).

- Step 4: Activity Assay.

- Set up reactions containing the assembled complex, substrates, and necessary cofactors.

- For the MenD-MenH cascade, include MenF to generate isochorismate in situ.

- Quantify the final product (e.g., SHCHC) using HPLC or spectrophotometric methods and compare the initial rates and yields against a control mixture of non-assembled enzymes.

Protocol 2: Developing a One-Pot Cascade for Metabolite Synthesis from Glycerol

This protocol outlines the creation of a modular multi-enzyme system for synthesizing non-canonical amino acids from glycerol, a low-cost and sustainable feedstock [4].

- Step 1: Pathway Design and Module Division.

- Module I (Glycerol Oxidation): Utilize alditol oxidase (AldO) to convert glycerol to D-glycerate. Include catalase to decompose the H₂O₂ byproduct.

- Module II (OPS Synthesis): Employ a sequence of D-glycerate-3-kinase (G3K), D-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH), and phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT) to transform D-glycerate into O-phospho-L-serine (OPS). Integrate an ATP regeneration system using polyphosphate kinase (PPK).

- Module III (ncAA Synthesis): Use a engineered O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) to catalyze the nucleophilic addition of diverse reagents (thiols, azoles) to the aminoacrylate intermediate, forming the target ncAAs.

- Step 2: Enzyme Preparation and Optimization.

- Identify and engineer key enzymes for enhanced activity and stability. For example, directed evolution of OPSS increased its catalytic efficiency by 5.6-fold [4].

- Express and purify each enzyme as described in Protocol 1, Step 2.

- Step 3: Cascade Integration and Scaling.

- Combine all enzyme modules, cofactors (PLP, NAD⁺), and substrates (glycerol, nucleophiles) in a single pot.

- Systematically optimize reaction conditions (pH, temperature, enzyme ratios) and enzyme concentrations to balance flux and prevent intermediate accumulation.

- Scale the reaction from gram to decagram scales, demonstrating viability in reactor systems up to 2 liters.

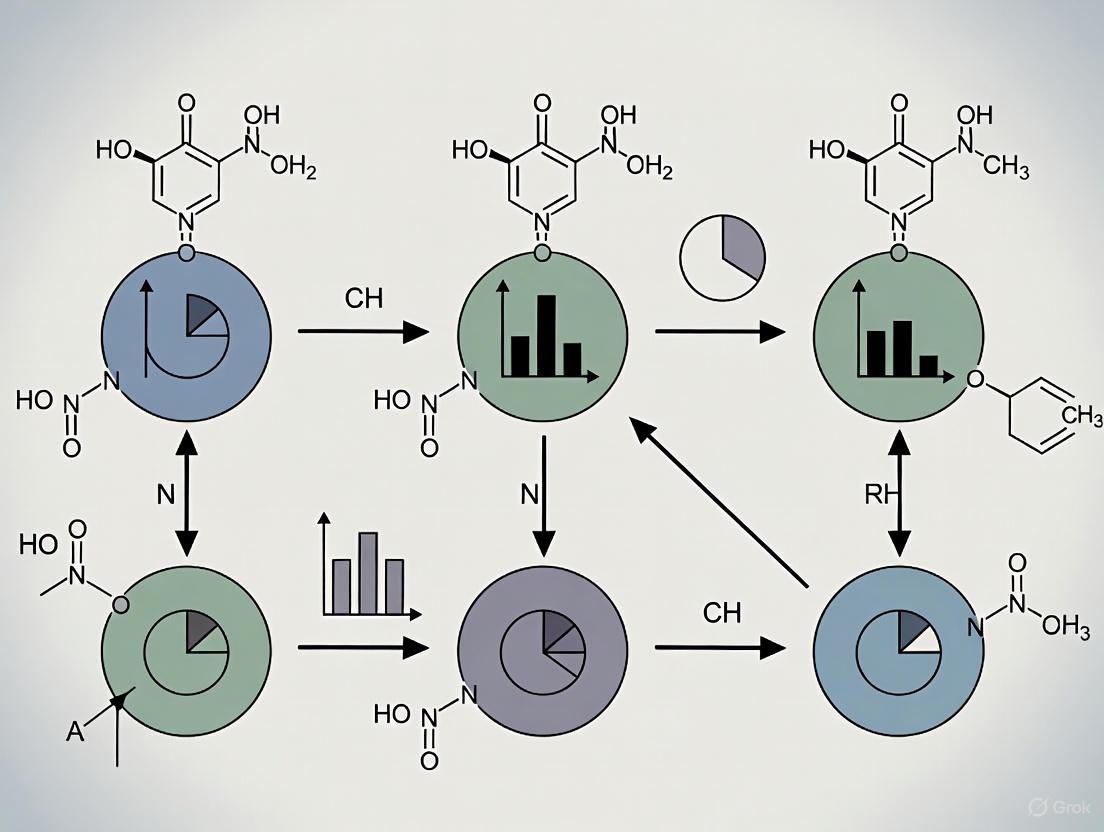

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: Modular pathway for ncAA synthesis from glycerol.

Diagram 2: Assembly process for scaffold-free enzyme complexes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Multi-Enzyme Cascade Development

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| RIAD & RIDD Peptide Tags | A pair of short, high-affinity peptides (18 aa and 44 aa) for scaffold-free enzyme assembly. | Creating multienzyme complexes like MenD-MenH for enhanced metabolic flux [3]. |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK2) | Regenerates ATP from ADP and inexpensive polyphosphate (polyP). | Maintaining ATP levels in cascades for OPS and 2′3′-cGAMP synthesis [4] [1]. |

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) | A promiscuous PLP-dependent enzyme that catalyzes C–S, C–Se, and C–N bond formation. | Synthesizing diverse non-canonical amino acids from OPS and nucleophiles [4]. |

| Glycerol | A low-cost, sustainable substrate derived from biodiesel production. | Serves as the starting carbon source for ncAA synthesis cascades [4]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Enzymatic or chemical methods to recycle NAD(P)H/NAD(P)+. | Enabling sustainable oxidoreductase cascades without stoichiometric cofactor use [6]. |

Multi-enzyme cascade reactions represent a paradigm shift in biocatalytic process design, mirroring the efficiency of natural metabolic pathways. These systems integrate multiple enzymatic transformations into a single vessel, offering profound advantages over traditional stepwise synthesis. For researchers in drug development and synthetic biology, the strategic implementation of cascades directly addresses critical challenges in the synthesis of complex molecules, including pharmaceutically relevant compounds such as statin precursors, non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs), and immune-signaling molecules like 2′3′-cGAMP [1] [4] [7].

The core benefits driving their adoption are threefold:

- Minimized Purification: Elimination of intermediate isolation simplifies processes and drastically reduces waste.

- Shifted Equilibria: Coupling thermodynamically favorable and unfavorable reactions drives conversion toward the desired product.

- Unstable Intermediate Handling: Reactive intermediates are consumed in situ, preventing degradation and enabling synthetic routes that are otherwise unfeasible.

This Application Note provides quantitative data, validated protocols, and design frameworks to facilitate the integration of these advantageous systems into your research.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent, high-impact studies utilizing multi-enzyme cascades, demonstrating their efficacy across various synthetic targets.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Representative Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Target Product | Cascade Components | Key Advantage Demonstrated | Reported Yield / Conversion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Statin Side Chain Precursor (Phenylacetamide-lactol) | Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ADH), DERA Aldolase, NADH Oxidase (NOX) | Shifted Equilibria (via cofactor recycling); Unstable Intermediate Handling (aldehyde) | 75% yield (optimized) | [7] |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs, 22 examples) | Alditol Oxidase, Catalase, Kinases, Dehydrogenases, O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) | Minimized Purification (one-pot); Shifted Equilibria (thermodynamically favorable pathway) | Gram to decagram scale; Atomic economy >75% | [4] |

| 2′3′-cGAMP (Immune-signaling molecule) | ScADK, AjPPK2, SmPPK2, cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS) | Minimized Purification (ATP intermediate); Cofactor Regeneration (ATP from polyphosphate) | 0.08 mol 2′3′-cGAMP / mol Adenosine | [1] |

| Bifunctional Compounds from Fatty Alcohols | Long-Chain Alcohol Oxidase (LCAO), ω-Transaminase (ω-Ta) | Unstable Intermediate Handling (aldehyde); Cofactor Regeneration | 71% conversion | [8] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Synthesis of a Statin Side Chain Precursor via a Three-Enzyme Cascade

This protocol outlines the optimized fed-batch synthesis for the key lactol intermediate, based on kinetic modeling to manage unstable acetaldehyde and achieve high yield [7].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function in the Cascade |

|---|---|

| Alcohol Dehydrogenase (ADH) | Oxidizes the primary alcohol substrate (N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-2-phenylacetamide) to the corresponding aldehyde intermediate. |

| DERA Aldolase | Catalyzes the sequential aldol addition of two acetaldehyde molecules to the aldehyde intermediate. |

| NADH Oxidase (NOX) | Regenerates the NAD+ cofactor from NADH, coupling regeneration to the oxidative reaction and shifting equilibrium. |

| NAD+ | Cofactor for the ADH-catalyzed oxidation. |

| Acetaldehyde | Substrate for the DERA-catalyzed aldol addition steps. |

| Triethanolamine HCl Buffer | Reaction buffer maintaining optimal pH for the enzyme system. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable reactor, combine the alcohol substrate (N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-2-phenylacetamide, 50 mM), NAD+ (0.5 mM), and ADH, DERA, and NOX enzymes in a 1:2:1 mass ratio in 100 mM triethanolamine-HCl buffer, pH 7.5.

- Fed-Batch Operation: Initiate the reaction. Use a syringe pump to feed acetaldehyde into the reactor at a controlled rate of 0.75 mmol/L·h. This slow addition is critical to prevent enzyme inhibition and side-reactions caused by high local concentrations of acetaldehyde.

- Process Monitoring: Maintain the reaction at 30°C with mild agitation. Monitor the consumption of the starting alcohol and the formation of the lactol product (N-(2-((2S,4S,6S)-4,6-dihydroxytetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)ethyl)-2-phenylacetamide) via HPLC.

- Reaction Termination and Work-up: After 8 hours, or when HPLC indicates maximal product formation, stop the reaction by removing the enzymes via ultrafiltration (10 kDa MWCO).

- Product Isolation: Concentrate the filtrate under reduced pressure and purify the lactol product using preparative HPLC.

Protocol: Multi-Enzyme Cascade for ncAAs from Glycerol

This modular, gram-scale protocol leverages a "plug-and-play" strategy to synthesize diverse non-canonical amino acids from the sustainable substrate glycerol [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function in the Cascade |

|---|---|

| Alditol Oxidase (AldO) | Oxidizes glycerol to D-glyceraldehyde. |

| Catalase | Degrades H2O2 produced by AldO, protecting other enzymes from oxidative damage. |

| d-Glycerate-3-kinase (G3K), d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH), Phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT) | Module converting D-glycerate to O-phospho-L-serine (OPS). |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) | Regenerates ATP from polyphosphate for the kinase steps. |

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) | Key enzyme that catalyzes nucleophilic substitution with various thiols, selenols, or azoles to form ncAAs. |

| Nucleophile | "Plug-and-play" reagent (e.g., allyl mercaptan, potassium thiophenolate, 1,2,4-triazole) that defines the ncAA side chain. |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Module Preparation: The cascade is conceptually divided into three modules. Module I (Oxidation): AldO and catalase. Module II (OPS Synthesis): G3K, PGDH, PSAT, PPK, and glutamate dehydrogenase for cofactor regeneration. Module III (ncAA Synthesis): The evolved OPSS enzyme.

- One-Pot Reaction Assembly: Combine all enzymes from Modules I, II, and III in a single pot. Add glycerol (100 mM), polyphosphate (for ATP regeneration), NAD+, L-glutamate, and the selected nucleophile (e.g., 150 mM potassium thiophenolate) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5).

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30-37°C with shaking for 12-24 hours.

- Scale-Up: This system has been demonstrated at a 2-liter scale. For larger scales, maintain efficient mixing and oxygen transfer for the oxidase component.

- Product Recovery: Terminate the reaction by centrifugation or filtration. The ncAAs can be purified from the aqueous reaction mixture using techniques such as ion-exchange chromatography or crystallization.

Conceptual and Pathway Diagrams

Statin Synthesis Pathway

Modular ncAA Synthesis

Discussion for Industrial Application

The case studies presented herein validate multi-enzyme cascades as a cornerstone for sustainable pharmaceutical development. The synthesis of the statin precursor showcases sophisticated reaction engineering, where kinetic modeling informed a fed-batch strategy to master unstable intermediates, pushing yield to 75% [7]. This directly translates to reduced E-factors and process intensification.

The ncAA production platform demonstrates unparalleled modularity and atom economy [4]. By leveraging an evolved OPSS enzyme and a "plug-and-play" nucleophile approach, a single standardized platform can generate a diverse library of high-value building blocks from glycerol. This modular design, with water as the sole byproduct, exemplifies the green chemistry principles crucial for modern manufacturing.

Underpinning these successes are advanced co-immobilization and engineering strategies. Spatial organization of enzymes, such as within Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) or on synthetic scaffolds, creates substrate channels that enhance local intermediate concentration and overall catalytic flux [2] [9]. Furthermore, the use of polyphosphate kinases (PPK2) for in situ ATP regeneration from inexpensive polyphosphate makes ATP-dependent cascades economically viable [1] [4]. These technologies collectively address the historical bottlenecks of cascade reactions—incompatible reaction conditions and inefficient mass transfer—paving the way for their broader industrial adoption.

This application note details the practical implementation of biomimetic multi-enzyme cascades, drawing inspiration from natural metabolic pathways and enzyme complexes (metabolons). We provide a detailed protocol for establishing a four-enzyme cascade to synthesize 2′3′-cGAMP, a cyclic dinucleotide with pharmaceutical relevance, from inexpensive adenosine and GTP. The document includes optimized experimental methodologies, quantitative performance data, and visualization of core concepts to aid researchers in designing efficient in vitro synthetic pathways for complex molecule production.

In nature, metabolic pathways achieve high efficiency through the organization of enzymes into supramolecular complexes known as metabolons. These complexes facilitate the channeling of intermediates between active sites, minimizing diffusion into the bulk solution and thereby increasing pathway flux, protecting unstable intermediates, and dealing with unfavorable thermodynamics [10]. The term "metabolon" denotes a "supramolecular complex of sequential metabolic enzymes and cellular structural elements," a concept first introduced by Srere [10]. Synthetic biology seeks to emulate these natural paradigms by constructing artificial multi-enzyme cascades. These cascades offer significant advantages for the synthesis of complex molecules, including the elimination of intermediate purification, handling of unstable intermediates, and shifting reaction equilibria through coupled reactions [1]. The design principles derived from natural metabolons are particularly relevant for the synthesis of high-value compounds such as pharmaceuticals and nutraceuticals [10]. This note frames these concepts within the broader context of multi-enzyme cascade reaction design, providing a validated protocol for a therapeutically relevant cascade.

Theoretical Background and Key Principles

Substrate Channeling in Natural Metabolons

The functional significance of natural enzyme complexes lies in their capacity for substrate channeling, defined as the movement of an intermediate between the active sites of successive enzymes with a significantly reduced probability of escape into the bulk cytoplasmic solution [10]. Channeling can occur through direct tunneling of intermediates or electrostatic guidance. In less organized metabolons, "probabilistic" channeling can occur within a large enzyme cluster, where the localized high enzyme concentration increases the probability that a substrate binds to an active site before it diffuses away [10]. Demonstrating channeling in vivo is technically challenging, with isotopic dilution experiments serving as a key method for its validation [10].

Design Principles for Synthetic Cascades

When engineering synthetic cascades, several principles must be considered:

- Balanced Flux: Enzyme concentrations must be adjusted to each other to achieve a balanced flux through the reaction cascade without the accumulation of intermediates [1].

- Cofactor Regeneration: A key limitation of enzyme cascades is the stoichiometric consumption of expensive cofactors like ATP. Integrating efficient cofactor regeneration systems is therefore critical for economic viability [1].

- Condition Compatibility: A suitable pH, temperature, and buffer must be identified in which all enzymes in the cascade maintain sufficient activity [1].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between natural paradigms and the design of synthetic enzyme cascades.

Featured Protocol: Four-Enzyme Cascade for 2′3′-cGAMP Synthesis

This protocol describes the synthesis of 2′3′-cyclic GMP-AMP (2′3′-cGAMP), a molecule of interest in cancer immunotherapy and vaccine adjuvants [1], from adenosine and GTP. The cascade integrates an ATP regeneration cycle with the final synthesis step catalyzed by cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS). The ATP regeneration sub-cascade consists of three enzymes: adenosine kinase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScADK), a polyphosphate kinase from Acinetobacter johnsonii (AjPPK2), and a polyphosphate kinase from Sinorhizobium meliloti (SmPPK2) [1]. This setup demonstrates the efficient use of an inexpensive nucleoside (adenosine) and phosphate donor (polyphosphate) for the synthesis of a valuable nucleotide product.

The experimental workflow for the entire process, from enzyme preparation to the final cascade reaction, is depicted below.

Detailed Experimental Methodology

Recombinant Enzyme Expression

- Expression Strains: E. coli BL21 (DE3) strains harboring the plasmids pET28a-ScADK, pET28a-AjPPK2, pET28a-SmPPK2, and pET28a-SUMOthscGAS (for truncated human cGAS) are used [1].

- Culture Medium: For kinases, use LB medium (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) supplemented with 50 mg/L kanamycin. For thscGAS, use 2xYT medium (16 g/L tryptone, 10 g/L yeast extract, 5 g/L NaCl) with 50 mg/L kanamycin and 25 mg/L chloramphenicol for strains containing the pLysS plasmid [1].

- Induction and Harvesting: Inoculate main cultures to an OD600 of 0.05 (kinases) or 0.1 (thscGAS) and incubate at 37°C, 200 rpm. Induce with 0.5 mM IPTG when OD600 reaches 1.0. Subsequently, incubate at 20°C for 11 hours (thscGAS) or overnight (kinases). Harvest cells by centrifugation (4,700 × g, 25 min, 4°C) and store pellets at -20°C [1].

Enzyme Purification

- Lysis Buffer:

- Kinases: 40 mM TRIS-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 10% (v/v) glycerol, pH 8.0.

- thscGAS: 50 mM TRIS-HCl, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 1 mM TCEP, pH 8.0.

- Cell Lysis: Resuspend cell pellets in lysis buffer and disrupt by sonication on ice (5 cycles of 30 s, with 0.5 s pulse and 1 s pause, at 10% amplitude) [1].

- Clarification and Purification: Clarify the lysate by centrifugation (43,000 × g, 20 min, 4°C). Purify the His-tagged enzymes using immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) under standard conditions [1].

Multi-Enzyme Cascade Reaction

- Reaction Setup: Assemble the cascade reaction in a suitable buffer (e.g., TRIS-HCl). The following table provides the optimized reaction composition and the function of each component.

Table 1: Optimized Reaction Composition for 2′3′-cGAMP Synthesis

| Component | Concentration | Function / Role in Cascade |

|---|---|---|

| Adenosine | 5 mM | Primary substrate for ATP regeneration cascade. |

| GTP | 5 mM | Substrate for cGAS. |

| Polyphosphate (PolyP) | 10 mM (as phosphate) | Inexpensive phosphate donor for ATP regeneration. |

| MgCl₂ | 10 mM | Essential cofactor for kinase activities. |

| ScADK | 0.1 µM | Phosphorylates adenosine to AMP using ATP. |

| AjPPK2 | 0.5 µM | Phosphorylates AMP to ADP using polyP. |

| SmPPK2 | 0.5 µM | Phosphorylates ADP to ATP using polyP. |

| thscGAS | 0.05 µM | Synthesizes 2′3′-cGAMP from ATP and GTP. |

| TRIS-HCl Buffer | 40 mM, pH 8.0 | Maintains optimal enzymatic pH. |

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction mixture at 30°C for a duration of 2 to 24 hours. Monitor product formation over time [1].

- Termination and Analysis: Terminate the reaction by heat inactivation or acid quenching. Analyze the formation of 2′3′-cGAMP and intermediates using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) or liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) [1].

Performance Data and Optimization

Iterative optimization of substrate, cofactor, and enzyme concentrations is critical for cascade performance. The established protocol achieves a final yield of 0.08 mole 2′3′-cGAMP per mole adenosine, which is comparable to traditional chemical synthesis methods [1]. The synthesis rates achieved with the cascade are comparable to the maximal reaction rate achieved when using ATP directly in single-step reactions [1].

Table 2: Key Optimization Parameters and Outcomes

| Parameter Varied | Optimal Condition | Impact on Yield / Rate |

|---|---|---|

| Adenosine Concentration | 5 mM | Higher concentrations did not significantly increase final product yield. |

| Enzyme Ratio (ScADK:AjPPK2:SmPPK2:thscGAS) | 2:10:10:1 (molar ratio) | Prevented accumulation of AMP/ADP intermediates; balanced flux to final product. |

| Polyphosphate Concentration | 10 mM (as Pi) | Ensured non-limiting phosphate donor for ATP regeneration. |

| Reaction Temperature | 30°C | Balanced stability and activity of all four enzymes. |

| Final 2′3′-cGAMP Concentration | ~0.4 mM (from 5 mM Adenosine) | Achieved with optimized parameters above. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required to establish the featured multi-enzyme cascade.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Plasmids | Harbors gene for recombinant enzyme expression. | pET28a vector with T7 promoter system for high-yield expression in E. coli [1]. |

| Expression Host | chassis for recombinant protein production. | E. coli BL21 (DE3), suitable for protein expression from pET vectors [1]. |

| Adenosine | Inexpensive starting material for ATP synthesis. | Substrate for ScADK in the ATP regeneration cascade [1]. |

| Guanosine Triphosphate (GTP) | Substrate for final product synthesis. | Required by cGAS for 2′3′-cGAMP production [1]. |

| Polyphosphate (PolyP) | Low-cost phosphate donor. | Replaces expensive phosphorylated donors (e.g., PEP) for ATP regeneration via PPK2 enzymes [1]. |

| Imidazole | Component of purification buffers. | Used for elution of His-tagged proteins during IMAC purification [1]. |

| Kanamycin | Selection antibiotic for plasmid maintenance. | Added to growth media for strains carrying pET28a-derived plasmids [1]. |

| Isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Inducer of protein expression. | Used to induce T7 RNA polymerase-driven gene expression in E. coli BL21(DE3) [1]. |

Applications and Future Outlook

The successful implementation of this cascade demonstrates the potential of learning from natural metabolic pathways to design efficient synthetic routes. Artificial multi-enzyme cascades are increasingly used for the synthesis of various natural products, including those derived from amino acids, fatty acids, and simple chemicals, often achieving high yields and excellent enantioselectivity [11]. Future developments in this field will likely focus on improving the compatibility of enzymes within cascades through engineering, developing more efficient cofactor regeneration systems, and exploring the integration of cascades into industrial production processes for pharmaceuticals and fine chemicals [11]. The principles outlined here provide a framework for researchers to design and optimize novel cascade reactions for diverse applications.

The design of efficient multi-enzyme cascade reactions presents a formidable challenge in biocatalysis and synthetic biology, with pathway thermodynamics representing a critical determinant of success. Favorable pathway energetics are not merely advantageous but essential for achieving high product yields and industrially viable reaction rates in complex enzymatic systems. This Application Note provides a structured framework for researchers to analyze, calculate, and optimize the thermodynamic parameters of multi-enzyme cascades, enabling the forward design of efficient biocatalytic systems for pharmaceutical and fine chemical production.

The fundamental importance of thermodynamics is exemplified in the development of a cascade for non-canonical amino acid (ncAA) synthesis from glycerol, where designers explicitly confirmed that the Gibbs free energy (ΔG'°) change of the entire pathway under physiological conditions was negative, ensuring the reaction sequence was thermodynamically favorable for efficient production [4]. Such systematic consideration of energetics separates successful cascades from those failing to achieve theoretical conversion yields.

Quantitative Thermodynamic Analysis of Representative Cascades

Experimental characterization of established enzyme cascades provides valuable reference data for predicting the thermodynamic feasibility of novel pathways. The following table summarizes key thermodynamic and performance parameters from published multi-enzyme systems:

Table 1: Thermodynamic and Performance Parameters of Characterized Enzyme Cascades

| Cascade Objective | Pathway Components | Key Thermodynamic Feature | Experimental Yield/Conversion | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ncAA synthesis from glycerol | 3 modules, 7+ enzymes | Negative ΔG'° under physiological conditions [4] | Gram to decagram scale production [4] | [4] |

| Dihydroxyacetone phosphate (DHAP) production | 10 enzymes from glycolysis | Integrated ATP/NAD recycling loops [12] | Model-enabled forward design [12] | [12] |

| D-Tagatose biosynthesis | β-Galactosidase, L-AI, auxiliary enzymes | Driven by intermediate conversion to overcome equilibrium limitations [13] | 23.73% conversion in dual-enzyme system [13] | [13] |

| 2′3′-cGAMP synthesis | 4-enzyme cascade with ATP regeneration | Coupled with polyphosphate-driven ATP regeneration [1] | 0.08 mol 2′3′-cGAMP per mol adenosine [1] | [1] |

Analysis of these systems reveals that successful implementations share common thermodynamic strategies: (1) incorporating cofactor regeneration subsystems to drive otherwise unfavorable reactions [1] [12], (2) designing pathways with fundamentally favorable overall Gibbs free energy [4], and (3) employing additional enzymes to consume inhibitory intermediates that shift unfavorable equilibria [13].

Protocol for Thermodynamic Pathway Evaluation

This protocol provides a systematic methodology for evaluating the thermodynamic feasibility of proposed multi-enzyme cascade reactions prior to experimental implementation.

Gibbs Free Energy Calculation

The thermodynamic driving force of a biocatalytic pathway is determined by calculating the standard Gibbs free energy change (ΔG'°) for each reaction step and the overall cascade.

Materials:

- Reaction Scheme: Complete balanced equations for all enzymatic steps

- Thermodynamic Reference Data: Experimentally determined standard Gibbs free energies of formation (ΔfG'°) for all reactants and products

- Calculation Software: Environment such as eQuilibrator (https://equilibrator.weizmann.ac.il/) or custom spreadsheet

Procedure:

- Define Stoichiometry: Write balanced biochemical equations for each enzymatic transformation at physiological pH (typically 7.0).

- Compile Reference Data: Obtain ΔfG'° values for all metabolites from biochemical thermodynamics databases.

- Calculate Step Energetics: For each reaction step, calculate ΔG'° = ΣΔfG'°(products) - ΣΔfG'°(reactants).

- Determine Pathway Sum: Calculate overall pathway ΔG'° by summing ΔG'° values for all individual steps.

- Identify Thermodynamic Bottlenecks: Flag any reaction steps with significantly positive ΔG'° values (> +10 kJ/mol) as potential bottlenecks.

Interpretation: A pathway with a strongly negative overall ΔG'° is thermodynamically favorable. However, individual steps with positive ΔG'° require special design considerations, such as coupling to favorable reactions or product removal strategies.

Experimental Validation Using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC provides direct experimental measurement of reaction enthalpy and equilibrium constants, enabling validation of calculated thermodynamic parameters.

Materials:

- Microcalorimeter: Such as Malvern MicroCal PEAQ-ITC

- Enzyme Solutions: Purified enzymes for each cascade step

- Substrate Solutions: Prepared in appropriate reaction buffer

- Dialysis Equipment: For buffer matching

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze all enzyme and substrate solutions against identical reaction buffer to ensure perfect chemical matching.

- Instrument Calibration: Perform standard electrical and chemical calibration tests according to manufacturer protocols.

- Titration Experiment: Fill sample cell with initial substrate solution and syringe with enzyme solution. Program instrument to perform sequential injections with adequate spacing between injections.

- Data Collection: Measure heat flow over time following each injection until baseline stabilization.

- Data Analysis: Fit integrated heat data to appropriate binding model to determine enthalpy change (ΔH), binding constant (Kb), and stoichiometry (n).

- Parameter Calculation: Calculate ΔG'° = -RTlnKb and ΔS'° = (ΔH - ΔG'°)/T.

The thermodynamic parameters obtained through ITC provide experimental validation of computationally predicted energetics and identify potential allosteric regulation not apparent from database values [12].

Implementation Workflow and Visualization

The following workflow illustrates the systematic approach to ensuring thermodynamic feasibility in cascade design:

Systematic Workflow for Thermodynamic Optimization

This workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of thermodynamic optimization, where bottlenecks identified through calculation inform targeted engineering strategies before experimental implementation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of thermodynamically optimized cascades requires specific reagent systems as highlighted in the following table:

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Thermodynamic Optimization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Thermodynamic Optimization | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Regeneration Systems | Polyphosphate Kinases (PPK) [4] [1], Glucose Dehydrogenase [14] | Regenerate ATP/NAD(P)H to drive thermodynamically unfavorable reactions | Essential for kinase-dependent cascades and redox reactions [1] |

| Energy-rich Substrates | Acetyl phosphate, Phosphoenolpyruvate [1] | Provide thermodynamic driving force through high-energy phosphate bonds | ATP regeneration in synthetic cascades |

| Enzyme Immobilization Systems | Metal-Organic Frameworks (ZIF-8) [15] | Enhance enzyme stability and enable spatial organization of cascade components | Improving operational stability in multi-enzyme systems |

| Analytical Standards | Isotopically-labeled metabolites | Enable accurate quantification in complex mixtures via mass spectrometry | Essential for parameterizing kinetic models [12] |

These reagent solutions address the most common thermodynamic challenges in cascade design, particularly the maintenance of cofactor homeostasis and enzyme stability under operational conditions.

Concluding Remarks

Thermodynamic analysis provides the fundamental foundation for designing efficient multi-enzyme cascade reactions with predictable performance characteristics. By integrating computational predictions of Gibbs free energy with experimental validation and targeted optimization strategies, researchers can overcome the thermodynamic barriers that frequently limit cascade efficiency. The methodologies outlined in this Application Note enable a rational approach to cascade design, moving beyond trial-and-error experimentation toward predictable engineering of complex biocatalytic systems for pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis. As the field advances, the integration of more sophisticated thermodynamic databases and predictive algorithms will further enhance our ability to design cascades with optimal energetic properties.

Exploring Enzyme Promiscuity for Expanded Synthetic Capabilities

Enzyme promiscuity, the ability of enzymes to catalyze alternative reactions beyond their primary physiological function, has emerged as a pivotal resource for engineering novel multi-enzyme cascades [16] [17]. This phenomenon provides a versatile toolkit for synthetic biologists seeking to develop efficient biosynthetic pathways for pharmaceutical and fine chemical production. Enzyme promiscuity is generally classified into three distinct categories: catalytic promiscuity (the ability to catalyze chemically distinct transformations), substrate promiscuity (the ability to utilize a range of different substrates for the same chemical reaction), and condition promiscuity (the ability to function under non-physiological conditions) [16] [18]. The strategic exploitation of these promiscuous activities enables researchers to construct complex reaction networks that bypass traditional synthetic challenges, including the need for intermediate purification, protection/deprotection steps, and functional group interconversions [19].

Within metabolic engineering, the inherent promiscuity of enzymes creates both opportunities and challenges. While it serves as an evolutionary starting point for new catalytic functions and enables the assembly of novel pathways, it can also lead to metabolic cross-talk, yield losses, and the production of undesired by-products [20] [21]. Understanding and harnessing this promiscuity is therefore critical for the rational design of efficient cascade systems. This application note provides a structured framework for identifying, quantifying, and implementing promiscuous enzymatic activities in multi-enzyme cascade reactions, with specific protocols and analytical tools to support researchers in drug development and synthetic biology.

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Enzyme Promiscuity

| Promiscuity Type | Definition | Key Characteristics | Applications in Cascades |

|---|---|---|---|

| Catalytic Promiscuity | Ability to catalyze chemically distinct transformations with different transition states [16] | - Altered bond formation/cleavage mechanisms- Often lower efficiency than native activity- Can be enhanced through protein engineering | - Creating new-to-nature reactions- Diversifying molecular scaffolds- Introducing non-biological functionality |

| Substrate Promiscuity | Capacity to process a range of structurally related substrates using the same catalytic mechanism [16] [18] | - Broad substrate specificity- Flexible active site architecture- Varying catalytic efficiencies for different substrates | - Pathway branching- Analog production- Library generation from common intermediates |

| Condition Promiscuity | Retention of activity under non-physiological conditions (e.g., organic solvents, extreme pH/temperature) [16] | - Stability in harsh environments- Altered specificity in non-aqueous media- Compatible with diverse reaction chemistries | - Coupling incompatible reaction steps- Shifting thermodynamic equilibria- Enabling one-pot synthesis strategies |

Quantitative Assessment of Promiscuous Activities

Experimental Measurement and Kinetic Analysis

The systematic quantification of promiscuous activities is fundamental to their successful implementation in cascade systems. Kinetic parameters (kcat, KM, kcat/KM) for both native and promiscuous reactions must be determined under standardized conditions to assess potential cascade feasibility [16] [22]. For substrate promiscuity, establishing substrate specificity profiles against structurally diverse compound libraries reveals the scope and limitations of an enzyme's versatility [23]. High-throughput screening methods using pooled gene knockout collections complemented by overexpression libraries (e.g., the ASKA collection for E. coli) can efficiently identify promiscuous activities that rescue metabolic deficiencies or confer resistance to toxic compounds [17].

A particularly informative metric for comparing promiscuity across enzyme families is the promiscuity index (J-value), which quantifies the ability of enzymes to metabolize a range of substrates without preference for any specific one [22]. This index ranges from 0 (perfect specificity) to 1 (no substrate preference), with dedicated drug-metabolizing enzymes typically exhibiting J-values >0.7 compared to <0.6 for substrate-specific homologs [22]. When characterizing promiscuous activities, researchers should prioritize enzymes from extremophiles as they provide stable templates for engineering, with metagenomics expanding the availability of such robust biocatalysts [16].

Table 2: Representative Promiscuity Indices and Kinetic Parameters for Selected Enzyme Classes

| Enzyme Class | Native Reaction | Promiscuous Activity | kcat (s⁻¹) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Promiscuity Index (J) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphotriesterase (PTE) | P–O bond hydrolysis | Arylesterase (C–O hydrolysis) [17] | 0.05-2.4 | 0.8-15.2 | ~10³-10⁵ | 0.72 [22] |

| Human Serum Paraoxonase (PON1) | Lacton hydrolysis | Phosphotriesterase activity [17] | 0.1-1.8 | 1.2-8.5 | ~10²-10⁴ | 0.75 [22] |

| Methane Monooxygenase | Methane hydroxylation | 150+ substrate hydroxylations [18] | Varies by substrate | Varies by substrate | ~10⁴-10⁶ | 0.81 (estimated) |

| HAD Superfamily Phosphatases | Phosphoester hydrolysis | Multiple phosphorylated metabolites [23] | 0.5-25.3 | 0.05-3.2 | ~10³-10⁵ | 0.70-0.85 [23] |

Structural and Mechanistic Basis of Promiscuity

The structural underpinnings of enzyme promiscuity provide critical insights for rational design. Key factors enabling promiscuous activities include:

Active site flexibility and conformational diversity: Particularly the mobility of active site loops, allows accommodation of structurally distinct substrates [16]. For example, in isopropylmalate isomerase, flexibility of an active site loop enables recognition of both hydrophobic and hydrophilic substrates [16].

Hydrophobic binding interactions: Unlike specific H-bonds or electrostatic interactions, hydrophobic bonds depend less on structural complementarity and more on desolvation, making them particularly amenable to promiscuous substrate recognition [16].

Cofactor exploitation and metal ion exchange: The incorporation or exchange of cofactors can dramatically alter enzyme specificity [16]. Introducing copper ions into thermolysin and aminopeptidase induced oxidase activities in these hydrolytic enzymes, while replacing Zn²⁺ with Mn²⁺ in carbonic anhydrase introduced peroxidase and enantioselective epoxidation activities [16].

Ligand binding mechanisms: Drug-metabolizing enzymes uniquely exploit both conformational selection (CS) for substrate recruitment and induced fit (IF) for substrate retention to optimize their promiscuity [22].

Application Protocols for Cascade Reaction Development

Protocol 1: Establishing an α-Ketoglutarate Production Cascade

This protocol details the implementation of a five-step enzymatic cascade for α-ketoglutarate production through the oxidative pathway of C6 uronic acids, leveraging native enzyme promiscuity for efficient conversion [19].

Materials and Reagents

- D-glucuronic acid (substrate)

- Uronate dehydrogenase (UDH) from Agrobacterium tumefaciens

- Glucarate dehydratase (GlucD) from Azospirillum brasilense

- 2-Keto-3-deoxy-D-glucarate (KDG) aldolase (KDGA) from Sulfolobus solfataricus

- α-Ketoacid dehydrogenase (KdgD) from Azospirillum brasilense

- NAD⁺ cofactor

- Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0)

- Oxygen supply system

Experimental Procedure

Reactor Setup: Configure a bubble column reactor with controlled aeration (kLa = 1.2-15 min⁻¹) and temperature maintenance at 25°C [19].

Initial Reaction Conditions: Prepare the reaction mixture containing:

- Potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0)

- D-glucuronic acid (10-50 mM)

- NAD⁺ (1-5 mM)

- Enzyme cocktail with optimized ratios:

- UDH (0.5-2.0 U/mL)

- GlucD (0.2-1.0 U/mL)

- KDGA (0.5-2.5 U/mL)

- KdgD (0.3-1.5 U/mL) [19]

Process Optimization via Multi-Objective Dynamic Optimization:

- Utilize kinetic modeling to identify Pareto-optimal process schedules balancing space-time yield, enzyme consumption, and cofactor consumption [19].

- Implement optimized dosing schedules for substrates and enzymes based on model predictions.

- Monitor reaction progress via HPLC or LC-MS for intermediate and product quantification.

Analytical Methods:

- Quantify α-ketoglutarate production using reverse-phase HPLC with UV detection at 210 nm.

- Monitor cofactor regeneration by measuring NAD⁺/NADH ratios spectrophotometrically at 340 nm.

- Track intermediate accumulation to identify cascade bottlenecks.

Expected Outcomes: This optimized cascade achieves high space-time yield with minimal enzyme consumption through balanced flux distribution. The multi-objective optimization approach typically identifies process conditions that improve multiple performance metrics simultaneously, such as a 30% reduction in enzyme consumption with only marginal decrease in space-time yield [19].

Protocol 2: ATP Regeneration Cascade for 2′3′-cGAMP Synthesis

This protocol establishes a four-enzyme cascade coupling ATP regeneration from adenosine with 2′3′-cGAMP synthesis, demonstrating how promiscuous kinase activities can be harnessed for complex nucleotide analog production [1].

Materials and Reagents

- Adenosine and GTP (substrates)

- Adenosine kinase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (ScADK)

- Polyphosphate kinase from Acinetobacter johnsonii (AjPPK2)

- Polyphosphate kinase from Sinorhizobium meliloti (SmPPK2)

- Truncated human cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (thscGAS)

- Polyphosphate (polyP₆₀, phosphate donor)

- Magnesium chloride (10 mM)

- TRIS-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0)

Experimental Procedure

Enzyme Preparation:

- Express and purify all enzymes using affinity chromatography with His-tag systems.

- Determine specific activities for each enzyme individually before cascade assembly.

- Adjust enzyme stocks to standardized concentrations in TRIS-HCl buffer.

Cascade Assembly and Optimization:

- Prepare master reaction mixture containing:

- TRIS-HCl buffer (50 mM, pH 8.0)

- Magnesium chloride (10 mM)

- Adenosine (5-20 mM)

- GTP (5-15 mM)

- Polyphosphate (20-40 mM)

- Add enzymes in optimized stoichiometric ratios:

- ScADK (0.1-0.5 mg/mL)

- AjPPK2 (0.2-0.8 mg/mL)

- SmPPK2 (0.3-1.0 mg/mL)

- thscGAS (0.4-1.2 mg/mL) [1]

- Prepare master reaction mixture containing:

Iterative Optimization:

- Systematically vary substrate, cofactor, and enzyme concentrations to balance flux through the cascade.

- Monitor ATP intermediate levels to ensure steady-state concentration without accumulation.

- Adjust enzyme ratios to prevent kinetic bottlenecks, particularly at the ADP→ATP conversion step.

Product Characterization:

- Quantify 2′3′-cGAMP formation using HPLC with tandem mass spectrometry.

- Calculate cascade efficiency as mole 2′3′-cGAMP per mole adenosine (target: 0.08 mol/mol) [1].

- Verify product identity by comparison with authentic standards.

Technical Notes: The cascade successfully demonstrates ATP-dependent synthesis from cheaper nucleosides, with final 2′3′-cGAMP synthesis rates comparable to single-step reactions with purified ATP. The polyphosphate-driven ATP regeneration system significantly reduces cost compared to traditional phosphoenolpyruvate/pyruvate kinase systems [1].

Visualization of Conceptual Relationships

Enzyme Promiscuity Framework for Cascade Design

Enzyme Cascade for cGAMP Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Investigating Enzyme Promiscuity in Cascade Systems

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Promiscuity Screening Libraries | Phosphorylated metabolite libraries (80+ compounds) [23]; Acyl-CoA substrate panels [23] | Profiling substrate ambiguity ranges; Identifying potential cross-reactivities | Library diversity should reflect potential metabolic intermediates; Concentration ranges must cover physiological and non-physiological levels |

| Cofactor Variants | Mn²⁺, Cu²⁺, Co²⁺ metal ion substitutions [16]; Alternative nucleotide triphosphates | Altering enzyme specificity; Inducing novel catalytic activities | Metal ion compatibility with buffer systems; Cofactor stability under reaction conditions |

| Stable Enzyme Templates | Enzymes from extremophiles; Metagenomic-derived catalysts [16] | Providing robust scaffolds for engineering; Maintaining activity in non-standard conditions | Compatibility with mesophilic enzyme partners in cascades; Potential need for codon optimization |

| Directed Evolution Systems | Error-prone PCR kits; Site-saturation mutagenesis libraries; CRISPR-enabled genome editing [18] | Enhancing promiscuous activities; Optimizing catalytic efficiency for new substrates | High-throughput screening capability required; Selection pressure must favor desired promiscuity |

| Analytical Tools for Cascade Monitoring | LC-MS/MS; Real-time NMR; Microfluidic droplet screens [20] | Quantifying multiple metabolites simultaneously; Identifying side products; Detecting pathway bottlenecks | Method sensitivity must accommodate low-yield promiscuous activities; Rapid sampling prevents metabolic flux artifacts |

| Computational Prediction Tools | AlphaFold 3 for structure prediction [18]; CADEE for computer-aided directed evolution [18]; Genome-scale metabolic models [20] | Predicting substrate binding modes; Identifying potential promiscuity hotspots; Forecasting evolutionary trajectories | Integration with experimental validation; Consideration of enzyme dynamics beyond static structures |

Advanced Cascade Design and Pharmaceutical Applications

The design of multi-enzyme cascade reactions represents a paradigm shift in synthetic biology and biocatalysis, enabling the efficient and sustainable production of complex molecules. These cascades mimic natural metabolic pathways by integrating multiple enzymatic steps into a unified system, often achieving superior atom economy, regio- and stereoselectivity under mild reaction conditions. The development of such systems requires a meticulous design process that begins with retrosynthetic analysis to deconstruct target molecules into simpler precursors, followed by the practical assembly of compatible enzyme modules. This approach has recently been successfully demonstrated in the synthesis of valuable compounds such as non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) from glycerol and D-tagatose from lactose [4] [13].

The core advantage of modular pathway design lies in its ability to overcome thermodynamic constraints, minimize intermediate isolation, and prevent the degradation of unstable intermediates through substrate channeling. Furthermore, the integration of cofactor regeneration systems addresses the economic challenges associated with stoichiometric use of expensive cofactors like ATP, making these cascades viable for industrial-scale applications [1]. This application note provides a detailed protocol for the implementation of a modular multi-enzyme cascade, from computational design to experimental validation, complete with quantitative data and visualization of critical workflows.

Retrosynthetic Analysis for Cascade Design

Retrosynthetic analysis is a foundational strategy for planning the synthesis of complex molecules by working backward from the target compound to identify simpler precursor molecules and feasible reaction steps. In the context of enzyme cascade design, this process involves deconstructing the target molecule into potential biosynthetic intermediates and identifying enzymes that can catalyze each transformation.

Computational Retrosynthetic Tools

Advanced computational tools have been developed to facilitate retrosynthetic planning. The RSGPT model, a generative transformer pre-trained on ten billion data points, represents the state-of-the-art in template-free retrosynthesis prediction, achieving a Top-1 accuracy of 63.4% on benchmark datasets [24]. Another approach utilizes guided reaction networks, which start from a curated set of substrates and apply reaction transforms in a forward-synthesis manner, retaining only the products most structurally similar to the target "parent" molecule to efficiently explore the synthetic space [25]. These computational methods help identify potential disconnections and suitable enzymatic reactions for cascade assembly.

Practical Application to ncAA Synthesis

The power of retrosynthetic analysis is exemplified in the design of a cascade for ncAA production. The target ncAA is deconstructed to identify O-phospho-L-serine (OPS) and various nucleophiles as key precursors. Recognizing the high cost of OPS, a further retrosynthetic step leads to the identification of glycerol as an ideal, sustainable starting material [4]. This analysis directly informs the structure of the three-module cascade described in Section 4.1.

Key Reagents and Research Tools

The successful implementation of a multi-enzyme cascade relies on a toolkit of specialized reagents and enzymes. The table below catalogues essential components for the synthesis of non-canonical amino acids and similar high-value products.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Reagent/Enzyme | Function in Cascade | Key Feature / Rationale for Use |

|---|---|---|

| O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS) [4] | Key catalyst forming C-S, C-Se, and C-N bonds in ncAA side chains. | Broad nucleophile promiscuity; can be improved via directed evolution (5.6-fold increase in efficiency). |

| Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) [4] [26] [1] | Regenerates ATP from polyphosphate (PolyPn). | Enables use of inexpensive PolyPn instead of stoichiometric ATP, crucial for cost-effective scaling. |

| Alditol Oxidase (AldO) [4] | Oxidizes glycerol to D-glycerate in the first module of the ncAA cascade. | Initiates the cascade using a sustainable biodiesel byproduct as the carbon source. |

| Engineered Peptide Pairs (e.g., PB1C/PB2N) [27] | Forms synthetic protein scaffolds for multi-enzyme assembly. | Enhances catalytic efficiency via substrate channeling; improves indigo synthesis in engineered E. coli. |

| d-Glycerate-3-kinase (G3K), d-3-PG dehydrogenase (PGDH), Phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT) [4] | Converts D-glycerate to OPS in the second module of the ncAA cascade. | Forms a critical linear segment to generate the core amino acid precursor. |

| Glutamate Dehydrogenase (gluGDH) [4] | Regenerates NAD+ from NADH. | Maintains redox balance, allowing catalytic use of the expensive NAD+ cofactor. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

This section provides a detailed methodology for establishing and optimizing a multi-enzyme cascade, using the ncAA production system as a primary example.

Protocol: Three-Module ncAA Synthesis from Glycerol

Principle: This cascade converts glycerol into a variety of ncAAs through a series of coordinated enzymatic steps, with water as the sole by-product [4].

Module I: Oxidation of Glycerol to D-Glycerate

- Reaction Setup: In a suitable buffer, combine 100 mM glycerol, 2 U/mL alditol oxidase (AldO), and 500 U/mL catalase.

- Conditions: Incubate at 30°C with continuous oxygenation (e.g., by gentle stirring or sparging).

- Purpose: AldO oxidizes glycerol to D-glycerate. Catalase is included to degrade the resulting H₂O₂, protecting other enzymes in the system from oxidative damage [4].

Module II: Conversion of D-Glycerate to O-Phospho-L-Serine (OPS)

- Reaction Setup: To the output of Module I, add the following to final concentrations:

- 5 mM ATP

- 10 mM L-glutamate

- 5 mM 2-oxoglutarate

- 50 mM polyphosphate (PolyPn)

- Enzyme Mix: 1 U/mL d-glycerate-3-kinase (G3K), 2 U/mL d-3-phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase (PGDH), 1.5 U/mL phosphoserine aminotransferase (PSAT), 5 U/mL polyphosphate kinase (PPK), and 2 U/mL glutamate dehydrogenase (gluGDH).

- Conditions: Incubate at 30-37°C and pH 7.5 for 4-6 hours.

- Purpose: This module transforms D-glycerate into OPS. The ATP consumed by G3K is regenerated by PPK using PolyPn. The gluGDH recycles NAD+ and regenerates L-glutamate from 2-oxoglutarate, ensuring redox balance [4].

Module III: Synthesis of Non-Canonical Amino Acids

- Reaction Setup: To the output of Module II, add a nucleophile of choice (e.g., 50 mM allyl mercaptan, potassium thiophenolate, or 1,2,4-triazole) and 2 U/mL of an evolved O-phospho-L-serine sulfhydrylase (OPSS).

- Conditions: Incubate at 30-37°C and pH 7.5 for 12-24 hours.

- Purpose: OPSS catalyzes the nucleophilic substitution reaction, utilizing the OPS from Module II and the added nucleophile to produce the target ncAA [4].

Scale-Up and Purification: This cascade has been demonstrated at a 2-liter reaction scale. Products can be purified using standard techniques such as ion-exchange chromatography, with recovery rates exceeding 85% and purities over 90% achievable, as demonstrated in similar systems [26].

Quantitative Performance of Enzyme Cascades

Systematic optimization of reaction parameters (e.g., pH, temperature, enzyme, and cofactor concentrations) is critical for high yield. The following table summarizes performance data from recent multi-enzyme cascades.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Representative Multi-Enzyme Cascades

| Target Product | Starting Material | Number of Enzymes | Key Optimized Parameter(s) | Final Yield / Titer |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UDP-GalNAc [26] | Uridine, GalNAc | 6 | MgCl₂, ATP, and PolyPn concentration via DoE | 95% yield, 46.1 mM (28 g/L) |

| Non-Canonical Amino Acids [4] | Glycerol | 7+ | Use of evolved OPSS enzyme | Gram to decagram scale |

| D-Tagatose [13] | Lactose | 2 (Dual-enzyme) | Temperature, pH, enzyme ratio | 23.73% conversion rate |

| 2',3'-cGAMP [1] | Adenosine, GTP | 4 | Balancing ATP synthesis and consumption | 0.08 mol 2',3'-cGAMP / mol adenosine |

Protocol Optimization via Design of Experiments (DoE)

For complex multi-enzyme systems, a systematic optimization approach like Design of Experiments (DoE) is highly recommended over one-factor-at-a-time testing.

Application Example: UDP-GalNAc Synthesis [26]

- Initial Screening: Identify critical factors (e.g., pH, MgCl₂, ATP, PolyPn) and their plausible ranges.

- Experimental Design: Create a statistical model (e.g., a Plackett-Burman or central composite design) to efficiently explore the factor space with a minimal number of experiments.

- Model Fitting & Validation: Execute the experiments, measure the yield, and fit a response surface model to identify optimal conditions.

- Result: The application of a two-round DoE protocol for UDP-GalNAc synthesis led to a 19-fold yield increase, from 5% to 95% [26].

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Visual representations are essential for understanding the logical flow and component relationships in complex cascade designs.

Retrosynthetic Logic for Cascade Design

This diagram illustrates the retrosynthetic thought process for deconstructing a target molecule into simpler precursors, ultimately leading to the identification of a sustainable starting material and the structure of a multi-module cascade.

Multi-Enzyme Cascade Assembly

This diagram details the practical forward-synthesis workflow for a functional multi-enzyme cascade, showing the sequence of enzymatic steps, key intermediates, and cofactor recycling systems.

Spatial organization of multi-enzyme systems is a critical advancement in biocatalysis, directly addressing efficiency challenges in cascade reactions. By mimicking the metabolic channeling observed in cellular environments, where enzymes are strategically clustered for optimal substrate transfer, researchers can significantly enhance reaction rates, improve stability, and minimize loss of unstable intermediates [28]. This document details practical applications and methodologies for implementing protein scaffolds and compartmentalization strategies, providing researchers and drug development professionals with protocols to advance the design of multi-enzyme cascades.

The core principle underpinning these strategies is the substrate channeling effect, where intermediates are directly transferred between consecutive enzymes without dilution into the bulk solution. This proximity minimizes diffusion limitations, protects labile intermediates, and can shift reaction equilibria toward desired products [29]. The following sections explore engineered protein scaffolds and compartmentalization within metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) as two powerful methods to achieve this spatial control.

Engineered Protein Scaffolds

Engineered protein scaffolds provide a biomimetic approach to co-localize enzymes with nanometric precision. These systems typically utilize high-affinity, orthogonal protein-peptide interactions to assemble specific enzymes into well-defined architectures.

TRAP-Based Scaffolding Systems

Tetratricopeptide Repeat Affinity Proteins (TRAPs) are engineered helix-turn-helix motifs that selectively bind to short peptide tags. Their design allows for the spatial organization of multiple enzymes while simultaneously enabling the electrostatic sequestration of cofactors like NADH, increasing local concentration and catalytic efficiency [29].

Table 1: Key Components of a TRAP-Based Scaffolding System for a Bi-Reductive Cascade

| Component | Type | Description and Function |

|---|---|---|

| TRAP1-3 Scaffold | Scaffold Protein | A fusion protein of TRAP1 and TRAP3 domains; serves as the assembly platform [29]. |

| FDH1 | Enzyme | Formate dehydrogenase from Candida boidinii, fused to C-terminal peptide-1 (MEEVV); catalyzes NADH regeneration [29]. |

| AlaDH3 | Enzyme | Alanine dehydrogenase from Bacillus stearothermophilus, fused to C-terminal peptide-3 (MRRVW); produces L-amino acids [29]. |

| Peptide-1 (MEEVV) | Interaction Tag | Cognate peptide for TRAP1 domain; genetically fused to FDH [29]. |

| Peptide-3 (MRRVW) | Interaction Tag | Cognate peptide for TRAP3 domain; genetically fused to AlaDH [29]. |

| NADH | Cofactor | Recyclable cofactor; its local concentration is increased via electrostatic interactions with positively charged residues on the TRAP scaffold surface [29]. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Metrics of TRAP-Scaffolded vs. Free Enzyme Systems

| System Configuration | Relative Specific Productivity | Product Titer (L-Alanine) | Key Enhancement Factor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Enzymes (FDH1 + AlaDH3) | 1.0 (Baseline) | Baseline | - |

| TRAP-Scaffolded System | ~5-fold increase | Increased | Enhanced NADH channeling and local concentration [29]. |

Figure 1: TRAP-Based Multi-Enzyme Assembly. The scaffold brings enzymes into proximity and sequesters cofactors.

Protocol: Assembling a TRAP-Scaffolded Bi-enzyme System

Objective: To assemble formate dehydrogenase (FDH1) and alanine dehydrogenase (AlaDH3) onto a TRAP1-3 scaffold for efficient L-amino acid synthesis with in situ NADH recycling.

Materials:

- Purified TRAP1-3 scaffold protein [29]

- Purified FDH1 enzyme (FDH fused to peptide-1: MEEVV) [29]

- Purified AlaDH3 enzyme (AlaDH fused to peptide-3: MRRVW) [29]

- Reaction Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

- Substrate Solution: 100 mM Sodium formate, 50 mM Pyruvate in reaction buffer

- Cofactor: 2 mM NAD+ in reaction buffer

Procedure:

- Pre-complexation: Mix the TRAP1-3 scaffold, FDH1, and AlaDH3 in a 1:2:2 molar ratio in reaction buffer. Incubate on ice for 30 minutes to allow complex formation via specific TRAP-peptide interactions [29].

- Reaction Initiation: Add the substrate solution and NAD+ cofactor to the pre-complexed enzyme-scaffold mixture to initiate the cascade reaction.

- Incubation: Maintain the reaction at 37°C with constant agitation.

- Analysis: Monitor L-alanine production over time using HPLC or a suitable spectrophotometric assay. Compare initial reaction rates and final product titers against a control reaction with non-scaffolded, free enzymes at the same concentration.

SCAB-Based Scaffolding Systems

SCAffolding Bricks (SCABs) utilize engineered consensus tetratricopeptide repeat (CTPR) domains. These modules can be designed to self-assemble via different mechanisms, such as reversible covalent disulfide bonds or non-covalent metal-driven assembly, providing flexibility in complex stability and formation conditions [30].

Protocol: Multi-enzyme Assembly via SCABs with Metal-Driven Assembly

Objective: To co-assemble SCAB-fused FDH and AlaDH enzymes using metal-coordination for enhanced cascade catalysis.

Materials:

- SCAB-FDH and SCAB-AlaDH fusion proteins [30]

- Assembly Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, containing 100 µM CuSO₄

- Control Buffer: 20 mM HEPES, pH 7.0, without metal ions

Procedure:

- Expression and Purification: Express and purify the SCAB-FDH and SCAB-AlaDH constructs from E. coli.

- Metal-Driven Assembly: Mix the purified SCAB-FDH and SCAB-AlaDH in a 1:1 molar ratio in Assembly Buffer. Incubate at 25°C for 1 hour to allow the engineered histidine residues on the SCAB modules to coordinate with Cu(II) ions and form the supramolecular assembly [30].

- Activity Assay: Assess the activity of the assembled complex using the same reaction conditions described in Protocol 2.1.1.

- Comparison: Perform a parallel reaction where enzymes are mixed in Control Buffer (lacking CuSO₄) to establish a non-assembled control. The metal-assembled system typically shows a significant increase in specific productivity, reported to be up to 3.6-fold higher than free enzymes [30].

Compartmentalization in Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

As an alternative to covalent protein scaffolds, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) offer a highly tunable porous material for enzyme compartmentalization. This approach involves encapsulating multiple enzymes within the crystalline cages of a MOF, providing a protective microenvironment that enhances stability and can concentrate substrates and intermediates [2].

Systematic Immobilization Strategies in MOFs

Table 3: Comparison of Multi-Enzyme Immobilization Strategies in MOFs

| Strategy | Description | Advantages | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Co-immobilization | Enzymes are simultaneously encapsulated within the MOF matrix during synthesis (de novo approach) [2]. | Simple one-pot procedure; provides confined space. | Limited control over enzyme spacing and ratio; can lead to mass transfer limitations [2]. |

| Compartmentalization | Enzymes are immobilized in separate, distinct regions within a hierarchical MOF structure [2]. | Prevents cross-interference; allows for optimization of local environment for each enzyme. | More complex synthesis requiring precise spatial control over MOF growth [2]. |

| Positional Co-immobilization (Layer-by-Layer) | Enzymes are immobilized sequentially in a spatially defined order, e.g., through a step-by-step MOF-building process [2]. | Maximizes proximity for cascade reactions; enables control over intermediate path length. | Synthesis is time-consuming and requires optimization for each enzyme layer [2]. |

Figure 2: Enzyme Compartmentalization in a MOF. The framework protects enzymes and facilitates intermediate transfer.

Protocol: De Novo Co-immobilization of Multi-enzymes in a ZIF-8 MOF

Objective: To encapsulate a two-enzyme cascade (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, GOx and Horseradish Peroxidase, HRP) within a Zeolitic Imidazolate Framework (ZIF-8) in a one-pot synthesis.

Materials:

- Enzyme Mix: 2 mg/mL each of GOx and HRP in a neutral pH buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0)

- Precursor Solution A: 50 mM Zinc acetate (Zn(OAc)₂) in deionized water

- Precursor Solution B: 2-Methylimidazole (2-Melm) in deionized water at a concentration of 1.0 M

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Keep the Enzyme Mix and Precursor Solution A on ice.

- Rapid Mixing: In a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube, rapidly mix 200 µL of the Enzyme Mix with 200 µL of Precursor Solution A. Immediately add 400 µL of Precursor Solution B and vortex vigorously for 10 seconds. The rapid coordination between Zn²⁺ and 2-Melm leads to the instantaneous formation of the ZIF-8 matrix, trapping the enzymes in situ [2].

- Incubation and Harvesting: Allow the mixture to stand at room temperature for 1 hour. Centrifuge the suspension at 10,000 × g for 5 minutes to pellet the enzyme-embedded MOF biocomposites (Enzyme@ZIF-8).

- Washing: Wash the pellet three times with deionized water to remove unencapsulated enzymes and residual reactants.

- Activity Assay: Resuspend the final Enzyme@ZIF-8 composite in a suitable reaction buffer. Measure the cascade activity and compare it to an equivalent amount of free enzymes in solution. Typically, the encapsulated system shows superior stability and reusability over multiple catalytic cycles [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents for Developing Protein Scaffolds and Compartmentalized Systems

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| CTPR/SCAB Domains | Stable, modular protein bricks that can be engineered to self-assemble or bind metals [30]. | Creating tunable, supramolecular protein scaffolds for organizing 2+ enzymes [30]. |

| TRAP Domains & Peptide Tags | Engineered protein-peptide pairs (e.g., TRAP1/Peptide-1) for orthogonal, high-affinity binding [29]. | Precisely assembling specific enzymes onto a linear protein scaffold with controlled stoichiometry [29]. |

| ZIF-8 MOF Precursors | Zinc ions and 2-methylimidazole form a biocompatible, microporous framework under mild conditions [2]. | One-pot de novo encapsulation of enzymes for enhanced stability and co-localization [2]. |

| SpyTag/SpyCatcher System | A protein pair that forms an irreversible isopeptide bond upon mixing [30]. | Covalently and irreversibly linking two enzymes or an enzyme to a scaffold protein [30]. |

| Cohesin-Dockerin Pairs | High-affinity protein-protein interaction pairs derived from natural cellulosomes [29]. | Reversibly assembling enzymes onto a scaffoldin protein, often in a calcium-dependent manner [29]. |

Cofactor regeneration is a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, particularly in the design of efficient multi-enzyme cascade reactions. Oxidoreductases, which represent the largest class of enzymes, depend on the expensive nicotinamide cofactors NAD(H) and NADP(H), while many synthetases require ATP [31]. The practical application of these enzymes in industrial biotechnology is economically viable only with effective in situ regeneration of these cofactors, as their stoichiometric use would be prohibitively costly [32] [31] [33]. Sustainable regeneration systems minimize resource consumption, energy input, and waste generation, aligning with the principles of green chemistry and responsible consumption [32]. This document details established protocols and application notes for recycling ATP and NAD(P)H, framed within the context of developing efficient multi-enzyme cascades for pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis.

NAD(P)H Regeneration Systems

Enzymatic Regeneration via NADH Oxidases

Enzymatic regeneration is the most prevalent method due to its high efficiency and specificity. A prominent approach utilizes H₂O-forming NADH Oxidases (NOX), which catalyze the oxidation of NADH to NAD⁺ with concurrent reduction of O₂ to H₂O. This system is highly favored for its good compatibility with other enzymes in aqueous reaction mixtures and for avoiding the accumulation of damaging H₂O₂ [34].

Table 1: Applications of NADH Oxidase in Rare Sugar Synthesis

| Rare Sugar | Key Enzymes | Cofactor | Maximum Yield | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-tagatose | Galactitol Dehydrogenase (GatDH), NOX | NAD⁺ | Up to 90% | Low-calorie sweetener [34] |

| L-xylulose | Arabinitol Dehydrogenase (ArDH), NOX | NAD⁺ | Up to 93% | Anticancer and cardioprotective agent [34] |

| L-gulose | Mannitol Dehydrogenase (MDH), NOX | NAD⁺ | 5.5 g/L | Anticancer drug precursor [34] |

| L-sorbose | Sorbitol Dehydrogenase (SlDH), NOX | NADPH | Up to 92% | Pharmaceutical intermediate [34] |

Application Note: L-Tagatose Production

Objective: To synthesize the rare sugar L-tagatose from galactitol using a coupled enzyme system with in situ cofactor regeneration. Principle: GatDH oxidizes galactitol to L-tagatose, concurrently reducing NAD⁺ to NADH. The NOX enzyme recycles NADH back to NAD⁺, completing the catalytic cycle. The use of a H₂O-forming NOX prevents enzyme inactivation by reactive oxygen species [34]. Protocol:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a reaction mixture containing 100 mM galactitol, 3 mM NAD⁺, 0.1 mg/mL purified GatDH, and 0.05 mg purified SmNox (a H₂O-forming NOX from Streptococcus mutans) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Incubation: Incubate the reaction at 30°C with constant shaking at 200 rpm for 12 hours.

- Monitoring: Monitor NADH consumption by measuring the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm. Quantify L-tagatose yield via HPLC. Notes: This system has been successfully implemented using combined cross-linked enzyme aggregates (combi-CLEAs) of GatDH and SmNox, which enhance operational stability and facilitate enzyme reuse [34].

Heterogeneous and Electrochemical Regeneration

Alternative regeneration strategies include heterogeneous and electrochemical methods. Heterogeneous systems using solid catalysts can offer advantages in catalyst recovery and reusability [32]. Electrochemical regeneration applies a potential to directly oxidize NADH at an electrode surface, offering a clean driving force without the need for a second substrate [31]. A key challenge is to achieve regioselective oxidation at the 1,4-position of the dihydronicotinamide ring to prevent the formation of inactive isomers.

ATP Regeneration Systems

ATP regeneration is critical for driving energetically unfavorable reactions, such as those catalyzed by kinases and ligases. The most common and efficient method couples the target reaction with a polyphosphate kinase (PPK).

Enzymatic Regeneration via Polyphosphate Kinase

Objective: To regenerate ATP from ADP using inexpensive polyphosphate (PolyPn) as a phosphate donor. Principle: Polyphosphate Kinase (PPK) catalyzes the transfer of a phosphate group from a polyphosphate molecule to ADP, regenerating ATP. This system is highly attractive due to the low cost and high stability of polyphosphate compared to other donors like phosphoenolpyruvate [4].

Protocol: ATP-Dependent Multi-Enzyme Cascade

This protocol is adapted from a system synthesizing O-phospho-L-serine (OPS) from glycerol, which is a key intermediate for non-canonical amino acid production [4]. Research Reagent Solutions: Table 2: Key Reagents for ATP Regeneration Cascade

| Reagent / Enzyme | Function | Source / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Polyphosphate (PolyPn) | Low-cost phosphate donor for ATP regeneration | Commercial food-grade |