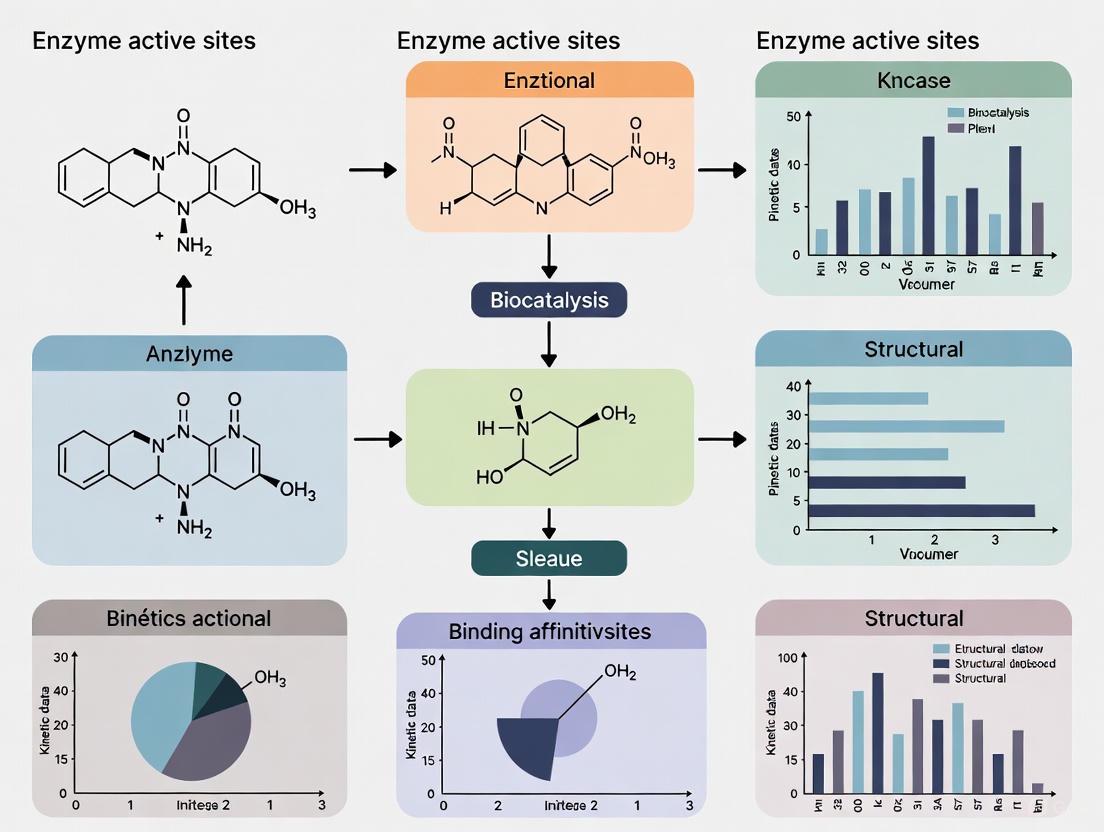

Rational Design of Enzyme Active Sites: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational design strategies for engineering enzyme active sites, a critical methodology for creating tailored biocatalysts.

Rational Design of Enzyme Active Sites: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of rational design strategies for engineering enzyme active sites, a critical methodology for creating tailored biocatalysts. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles linking enzyme structure to function, details key computational and experimental methodologies, and addresses persistent challenges in the field. The content highlights recent transformative advances, including fully computational design of high-efficiency enzymes and AI-driven approaches, which are achieving catalytic parameters comparable to natural enzymes. By synthesizing insights from foundational exploration to validation techniques, this review serves as a guide for leveraging rational design to develop novel therapeutics and sustainable biocatalytic processes.

The Blueprint of Catalysis: Understanding Enzyme Structure-Function Relationships

The "lock-and-key" principle, proposed by Emil Fischer over a century ago, established the foundational concept of molecular complementarity in enzyme catalysis. While this principle correctly introduced the geometric basis for specificity, our contemporary understanding recognizes that enzyme active sites are not rigid, static locks. Modern enzymology reveals that active site architecture is a dynamic and chemically sophisticated environment where precise atomic positioning, electrostatic preorganization, and conformational plasticity collectively govern substrate selection and transition state stabilization. The architectural principles governing these sites extend far beyond simple shape complementarity to include electric field alignment and the population of near-attack conformations, which are essential for achieving the extraordinary rate enhancements and specificity characteristic of biological catalysts [1] [2].

Within the context of rational enzyme design, elucidating these architectural determinants is paramount for engineering enzymes with tailored specificities for therapeutic and industrial applications. This Application Note explores the key architectural features dictating enzyme specificity and provides detailed protocols for their computational analysis and experimental manipulation, enabling researchers to move beyond the classical lock-and-key paradigm toward a dynamic, mechanism-informed design strategy.

Application Notes: Key Architectural Determinants of Specificity

The specificity of an enzyme is an emergent property resulting from the interplay of multiple structural and dynamic factors within its active site architecture. The table below summarizes these key determinants and their functional impact.

Table 1: Key Architectural Determinants of Enzyme Specificity and Engineering Applications

| Architectural Determinant | Functional Role in Specificity | Rational Design Application | Experimental Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometric Complementarity | Provides steric exclusion and optimal substrate positioning relative to catalytic residues. | Cavity reshaping via site-saturation mutagenesis to accommodate non-native substrates [1]. | High-throughput microfluidic enzyme kinetics [3]. |

| Electrostatic Preorganization | Stabilizes transition states and reactive intermediates through oriented electric fields and dipoles; crucial for charge separation/redistribution [1]. | Computational redesign of active site electrostatics to alter catalytic rate or substrate preference. | Vibrational Stark Shift spectroscopy to measure electric fields [1]. |

| Near-Attack Conformation (NAC) Population | Measures the fraction of enzyme-substrate complex conformations that are geometrically poised for catalysis [2]. | Using NAC parameters (distances, angles) as proxies for activity in high-throughput mutant screening [2]. | Molecular dynamics simulations coupled with activity assays. |

| Dynamic Loop Regions | Control substrate access and product egress; conformational rearrangements often essential for catalysis [3]. | Loop swapping or engineering to alter substrate scope, enantioselectivity, or stability [4]. | NMR-guided directed evolution and stability-activity trade-off analysis [3] [5]. |

| Allosteric Networks | Long-range communication via residue interaction networks can fine-tune active site properties and enable feedback regulation [3]. | Introducing distal mutations to modulate activity or stability (e.g., iCASE strategy) [5]. | Deep mutational scanning to map fitness landscapes [3]. |

Quantitative Insights from Machine Learning-Guided Engineering

Recent advances integrate these architectural principles with machine learning (ML) to enable predictive engineering. For instance, an ML-guided platform was used to engineer amide synthetase (McbA) activity. By evaluating 1,217 enzyme variants across 10,953 unique reactions, researchers built a model that predicted variants with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for synthesizing nine pharmaceutical compounds [6]. This demonstrates the power of quantitative, data-driven approaches in deciphering the complex sequence-structure-function relationships that govern specificity.

Table 2: Performance Summary of Machine Learning-Guided Engineering of Amide Synthetase (McbA)

| Target Compound | Wild-Type Conversion | Best ML-Predicted Variant Improvement (Fold) |

|---|---|---|

| Moclobemide | ~12% | Not Specified |

| Metoclopramide | ~3% | Not Specified |

| Cinchocaine | ~2% | Not Specified |

| Range across 9 pharmaceuticals | Trace to ~12% | 1.6 to 42-fold increase in activity |

Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for the computational analysis and experimental engineering of active site architecture.

Protocol 1: Computational Prediction of Specificity-Determining Residues Using NAC4ED

The NAC4ED platform employs a "near-attack conformation" strategy to efficiently screen for mutants with enhanced activity or altered specificity by evaluating the population of reactive conformations, bypassing computationally expensive transition-state calculations [2].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for NAC4ED Protocol

| Reagent / Software | Function / Specification | Source / Example |

|---|---|---|

| NAC4ED Web Server | High-throughput automated mutant screening platform. | http://lujialab.org.cn/software/ [2] |

| Wild-Type Enzyme Structure | Initial 3D model for the mutagenesis pipeline (PDB format). | PDB Database (e.g., PDB: 6SQ8 for McbA [6]) |

| Substrate Molecular Structure | Ligand file for docking simulations. | Molecular Databases (e.g., PubChem) |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | For simulating enzyme-ligand complex dynamics. | GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD |

| Rosetta Software Suite | For protein structure modeling and energy calculations. | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ [7] |

Procedure:

- Model Construction (Mutation Module)

- Input the wild-type enzyme structure (e.g., PDB format).

- Define the target active site residues for mutagenesis. The platform will automatically generate the 3D structures of the specified single or multiple point mutants.

Complex Structure Acquisition (Docking Module)

- Prepare the substrate molecule: generate a 3D structure and minimize its energy using chemical informatics tools.

- Define the NAC parameters: based on the catalytic mechanism, identify the two atoms that will form a new bond and the key bond angle in the transition state. For example, for a nucleophilic attack, this would be the distance between the nucleophile and the electrophile.

- Input the substrate and NAC parameters into NAC4ED. The platform will perform molecular docking to generate the enzyme-substrate complex structures for each mutant.

Conformational Sampling (Dynamics Simulation Module)

- For each mutant complex, run a molecular dynamics (MD) simulation (e.g., 50-100 ns) to sample conformational space.

- Ensure simulations are performed in an appropriate solvent model and with physiological ionic strength.

Evaluation Analysis (Evaluation Analysis Module)

- Trajectory Analysis: For each frame of the MD trajectory, calculate the defined NAC distance and angle.

- NAC Population Calculation: A conformation is classified as an NAC if the distance between the critical atoms is less than the sum of their van der Waals radii and the angle is close to that of the transition state. The population is calculated as: ( P = N{\text{active}} / (N{\text{active}} + N_{\text{inactive}}) ), where ( N ) is the number of frames [2].

- Variant Ranking: Rank all tested mutants based on their NAC population. A higher NAC population correlates with a lower activation barrier and higher catalytic activity. This prioritized list guides experimental validation.

The following workflow diagram outlines the key steps and decision points in the NAC4ED protocol:

Protocol 2: Machine-Learning Guided Engineering of Substrate Specificity

This protocol leverages cell-free expression systems and ML to rapidly map sequence-function relationships and engineer substrate specificity, as demonstrated for amide synthetases [6].

Procedure:

- Library Design and Build

- Hot Spot Identification: Guided by a crystal structure, select 60-80 residues enclosing the active site and substrate access tunnels.

- Cell-Free DNA Assembly: For each target position, use primer-containing nucleotide mismasks in a PCR-based, site-saturation mutagenesis workflow. Digest the parent plasmid with DpnI, perform intramolecular Gibson assembly to form a mutated plasmid, and PCR-amplify linear DNA expression templates (LETs). This enables the construction of sequence-defined libraries (e.g., 1216 single-point mutants) in a day without transformation [6].

High-Throughput Testing

- Cell-Free Protein Expression (CFE): Use the LETs in a CFE system to synthesize mutant proteins directly in a 96-well plate format.

- Functional Assay: Under industrially relevant conditions (e.g., low enzyme loading, high substrate concentration), assay all variants for the desired activity (e.g., amide bond formation). Collect quantitative conversion data for each variant.

Machine Learning Model Training and Prediction

- Data Compilation: Compile a dataset where each mutant sequence is linked to its functional output (fitness).

- Model Training: Train supervised ML models (e.g., augmented ridge regression) using the sequence-function data. These models can incorporate evolutionary signals from homologous sequences for zero-shot predictions.

- Variant Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the fitness of higher-order mutants (e.g., double, triple mutants) not present in the initial library. Select the top predicted variants for experimental validation.

Experimental Validation

- Express and purify the ML-predicted top-performing variants using a standard heterologous expression system (e.g., E. coli).

- Characterize enzyme kinetics (Km, kcat) and specificity under rigorous conditions to confirm the model's predictions.

The iterative workflow for this protocol is visualized below, integrating both computational and experimental stages:

The catalytic prowess of enzymes, the workhorse proteins that orchestrate the vast repertoire of chemical reactions in living organisms, stems from their precisely organized active sites. These specialized regions facilitate the transformation of substrates into products with remarkable efficiency and specificity under physiological conditions. Understanding catalytic mechanisms requires decoding two fundamental components: the key amino acid residues that perform chemical transformations and the essential cofactors that extend the catalytic capabilities beyond the limitations of the standard 20 amino acids. Within the context of rational enzyme design, this knowledge enables researchers to predictably manipulate catalytic activity, selectivity, and stability for applications ranging from industrial biocatalysis to therapeutic development [8].

Enzyme active sites represent highly complementary three-dimensional environments tailored to recognize specific substrates and stabilize transition states through a combination of polar residues that form hydrogen bonds and non-hydrogen bonding interactions that create solvent-excluded templates of the substrate's van der Waals surface [9]. The sophisticated interplay between these components enables enzymes to achieve extraordinary rate accelerations, often exceeding 10^10-fold compared to uncatalyzed reactions [9]. This application note examines the fundamental principles governing enzyme catalysis, presents experimental and computational methodologies for mechanistic investigation, and discusses applications in drug discovery and enzyme engineering, providing researchers with practical frameworks for studying and manipulating catalytic mechanisms.

Fundamental Components of Enzyme Catalysis

Catalytic Amino Acid Residues and Their Functions

The catalytic toolkit of enzymes relies disproportionately on a small subset of polar amino acid residues, despite the availability of 20 standard amino acids for protein construction. Analysis of mechanism-aware databases such as MACiE (Mechanism, Annotation, and Classification in Enzymes) reveals that histidine, cysteine, aspartate, glutamate, arginine, and lysine constitute the most frequently employed catalytic residues, with histidine participating in approximately 43% of all known enzymatic reaction steps [8]. These residues provide diverse reactive groups that promote catalysis through acid-base chemistry, nucleophilic attack, covalent catalysis, and electrostatic stabilization of transition states.

The exceptional catalytic frequency of histidine stems from its mid-range pKa (~6-7) for the imidazole side chain, allowing it to function as both an acid and base under physiological pH conditions. Cysteine, with its highly nucleophilic thiol group, participates in covalent catalysis across numerous enzyme classes, including proteases, phosphatases, and acyltransferases. Acidic residues (aspartate and glutamate) typically serve as Brønsted acids or electrostatic stabilizers, while basic residues (arginine and lysine) often function in anion binding and charge stabilization [8]. Tyrosine, serine, threonine appear less frequently as catalytic residues but play essential roles in specific enzyme classes, such as serine hydrolases and kinases [8].

Table 1: Frequency and Catalytic Functions of Key Amino Acid Residues

| Amino Acid | Relative Catalytic Frequency | Primary Catalytic Functions | Representative Enzyme Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Histidine | High (~43%) | Acid-base catalysis, Nucleophilic activation, Proton shuttle | Serine proteases, Phosphotransferases |

| Cysteine | High | Covalent catalysis, Nucleophilic attack, Redox reactions | Thioredoxins, Cysteine proteases, Dehydrogenases |

| Aspartate | High | Acid-base catalysis, Electrostatic stabilization, Metal binding | Aspartic proteases, ATPases, Dehydrogenases |

| Glutamate | High | Acid-base catalysis, Electrostatic stabilization, Metal binding | Glutamate dehydrogenases, Hydrolases, Lyases |

| Arginine | Moderate | Cation-π interactions, Charge stabilization, Anion binding | Nitric oxide synthases, Kinases, Dehydrogenases |

| Lysine | Moderate | Schiff base formation, Nucleophilic attack, Charge stabilization | Aldolases, Decarboxylases, Synthases |

| Serine | Moderate | Nucleophilic attack, Hydrogen bonding, Oxygen nucleophile | Serine proteases, Esterases, β-Lactamases |

| Threonine | Low | Nucleophilic attack, Hydrogen bonding, Metal ligand | Proteasomes, Methionine synthase |

| Tyrosine | Low | Electron transfer, Radical intermediation, Hydrogen bonding | Ribonucleotide reductase, Photosystem II |

Beyond their direct chemical roles, active site residues create precisely engineered microenvironments that enhance their reactivity. For instance, charge stabilization networks can significantly lower the pKa of catalytic residues, while hydrophobic exclusion can create local dielectric environments that strengthen electrostatic interactions. The spatial arrangement of these residues, achieved through the precise folding of the protein scaffold, positions functional groups for optimal interaction with the substrate and stabilization of the reaction's transition state [10].

Essential Cofactors in Enzyme Catalysis

Cofactors represent essential non-protein chemical compounds that extend the catalytic repertoire of enzymes beyond the capabilities of standard amino acid side chains. These molecules can be broadly categorized into metal ions and organic coenzymes, both of which are required in the active site for catalytic activity in approximately one-third of all known enzymes [11]. Organic coenzymes, often derived from vitamins, function as transient carriers of specific functional groups or electrons during catalytic cycles, while metal ions frequently participate in substrate activation, electrostatic stabilization, and redox chemistry.

The CoFactor database documents 27 major organic enzyme cofactors that serve essential roles in biocatalysis, including NAD+/NADP+, FAD/FMN, thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), pyridoxal phosphate (PLP), and coenzyme A [11]. These cofactors significantly expand the chemical capabilities of enzyme active sites, enabling challenging transformations such as redox reactions, decarboxylations, and group transfers that would be difficult or impossible using only amino acid functional groups. Cofactors may bind loosely to enzymes (as cosubstrates) or tightly as prosthetic groups, with enzymes lacking their required cofactors termed apoenzymes and functional complexes termed holoenzymes [12].

Table 2: Major Organic Cofactors and Their Catalytic Functions

| Cofactor | Vitamin Precursor | Primary Catalytic Functions | Representative Enzyme Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAD+/NADP+ | Niacin (B3) | Hydride transfer, Redox reactions | Dehydrogenases, Reductases |

| FAD/FMN | Riboflavin (B2) | Electron transfer, Redox reactions | Oxidases, Dehydrogenases |

| Thiamine Pyrophosphate (TPP) | Thiamine (B1) | Decarboxylation, Aldehyde transfer | Decarboxylases, Transketolases |

| Pyridoxal Phosphate (PLP) | Pyridoxine (B6) | Transamination, Decarboxylation, Racemization | Aminotransferases, Decarboxylases |

| Coenzyme A | Pantothenic acid (B5) | Acyl group transfer | Transferases, Synthetases |

| Biotin | Biotin (B7) | CO₂ transfer, Carboxylation | Carboxylases, Transcarboxylases |

| Tetrahydrofolate | Folate (B9) | One-carbon unit transfer | Methyltransferases, Synthetases |

| Cobalamin | Cobalamin (B12) | Alkyl transfer, Rearrangements | Mutases, Methyltransferases |

Metal ion cofactors, including iron, magnesium, manganese, zinc, copper, and molybdenum, participate in diverse catalytic functions ranging from Lewis acid catalysis to electron transfer. Particularly sophisticated metal-based mechanisms include the two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism (TCM), where two metal ions (either identical or distinct) positioned approximately 3.8 Å apart work synergistically to activate substrates, orient reaction partners, and stabilize transition states in enzymes such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerases, HIV-1 integrase, and various phosphodiesterases [13]. The strategic incorporation of metal clusters and two-metal-ion systems represents a remarkable evolutionary innovation for catalyzing challenging biochemical transformations, particularly phosphoryl and nucleotidyl transfers [13].

Methodologies for Investigating Catalytic Mechanisms

Experimental Approaches for Mechanistic Analysis

Site-Directed Mutagenesis and Functional Analysis

Site-directed mutagenesis serves as a fundamental experimental approach for elucidating the functional contributions of specific amino acid residues in enzyme catalysis. The protocol involves systematically replacing target residues with alternative amino acids (typically alanine for side chain removal or conservative substitutions for functional group modulation) and quantitatively measuring the effects on catalytic parameters. The following standardized protocol provides a framework for conducting and interpreting mutagenesis studies:

Protocol: Site-Directed Mutagenesis for Catalytic Mechanism Analysis

Target Identification: Select candidate residues based on structural data (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM), sequence conservation analysis, or computational predictions of functional importance.

Mutant Design: Design primer pairs containing the desired codon changes using software such as PrimerX or QuikChange. Preferentially target residues implicated in direct catalysis (nucleophiles, acid-base catalysts) versus those involved primarily in substrate binding or structural maintenance.

Plasmid Amplification: Perform PCR amplification of the plasmid containing the wild-type gene using high-fidelity DNA polymerase (e.g., PfuUltra) with phosphorylated primers.

Template Digestion: Digest the parental DNA template with DpnI restriction enzyme (specific for methylated DNA) at 37°C for 1-2 hours to eliminate background wild-type plasmids.

Transformation and Selection: Transform the digested product into competent E. coli cells (e.g., DH5α), plate on selective media, and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Sequence Verification: Isolate plasmid DNA from resulting colonies and verify mutations by Sanger sequencing of the entire gene to confirm intended changes and exclude unintended mutations.

Protein Expression and Purification: Express and purify mutant proteins using standardized protocols (e.g., affinity chromatography followed by size exclusion chromatography) with strict attention to maintaining consistent purification conditions across variants.

Kinetic Characterization: Determine kinetic parameters (kcat, KM, kcat/KM) under saturating substrate conditions using appropriate assay methods (spectrophotometric, fluorometric, or HPLC-based). Include complementary assays to probe specific catalytic steps when possible.

Structural Integrity Assessment: Confirm proper folding of mutant proteins using circular dichroism spectroscopy, thermal shift assays, or size exclusion chromatography to distinguish between catalytic defects and global structural perturbations.

Data Interpretation: Interpret kinetic results in the context of the proposed catalytic mechanism, recognizing that dramatic reductions in kcat/KM (≥10²-fold) typically indicate direct catalytic involvement, while more modest effects may suggest peripheral roles in substrate binding or positioning.

This methodology revealed surprising insights into the mutability of non-hydrogen bonding contacts in the E. coli glucokinase active site, where simultaneous replacement of six shape-determining residues with glycine reduced catalytic efficiency by only 200-fold despite the enzyme's total rate enhancement exceeding 10¹⁰ [9]. Such findings challenge simplistic assumptions about the relationship between structural complementarity and catalytic power.

High-Throughput Mutagenesis and Kinetic Characterization

Advanced platforms such as HT-MEK (High-Throughput Microfluidic Enzyme Kinetics) enable rapid functional characterization of thousands of enzyme variants, providing unprecedented insights into the quantitative contributions of individual residues to catalysis [14]. This approach combines large-scale mutagenesis with microfluidics to measure kinetic parameters and folding stability in parallel, distinguishing between mutations that directly affect chemical catalysis versus those that primarily impact protein stability.

Protocol: HT-MEK for Comprehensive Mutational Analysis

Variant Library Construction: Generate comprehensive mutant libraries using degenerate oligonucleotides or solid-phase parallel synthesis to create single-site variants across the entire protein sequence.

Microfluidic Device Preparation: Fabricate or acquire HT-MEK chips containing nanoliter-scale reaction chambers with integrated valves for fluid control.

Protein Immobilization: Immobilize GFP-tagged enzyme variants within individual chambers via anti-GFP antibodies to enable controlled washing and assay conditions.

Multiparameter Kinetic Assays: Perform sequential kinetic measurements under multiple substrate concentrations and conditions using fluorescence-based detection to determine kcat, KM, and Ki values.

Folding Stability Assessment: Measure variant stability using chemical or thermal denaturation protocols within the microfluidic device to distinguish properly folded variants with impaired catalysis from those with global stability defects.

Data Integration and Analysis: Integrate kinetic and stability data to generate comprehensive functional maps, identifying residues that participate directly in catalysis versus those involved in allosteric regulation or structural maintenance.

Application of HT-MEK to the bacterial phosphatase PafA revealed that over 70% of mutations, including many distant from the active site, diminished enzymatic activity, with approximately one-third of these defects attributable to persistent misfolding rather than direct catalytic impairment [14]. This technology provides a powerful approach for dissecting the complex relationship between protein sequence, structure, and function at unprecedented scale and resolution.

Computational Approaches for Mechanism Analysis

Computational methods provide complementary tools for investigating catalytic mechanisms, offering atomic-level insights into reaction pathways and dynamics that are often challenging to capture experimentally. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as particularly powerful approaches for studying the dynamic behavior of enzyme active sites during catalysis, revealing conformational changes, allosteric communication, and transient intermediate states [15].

Molecular Dynamics Simulation Protocol for Catalytic Mechanism Investigation

System Preparation: Obtain initial coordinates from experimental structures (Protein Data Bank), add missing residues and hydrogen atoms, assign protonation states consistent with physiological pH, and parameterize cofactors and substrates.

Force Field Selection: Choose appropriate force fields (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB) with specialized parameters for non-standard residues, cofactors, and metal ions.

Solvation and Electrostatics: Solvate the system in a water box (e.g., TIP3P model) with dimensions extending at least 10 Å from the protein surface, add counterions to neutralize system charge, and implement particle mesh Ewald (PME) method for long-range electrostatics.

Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent and conjugate gradient minimization to relieve steric clashes and optimize hydrogen bonding networks.

System Equilibration: Conduct gradual equilibration in stages: (1) restraint on protein heavy atoms (100-500 ps), (2) restraint on protein backbone atoms (100-500 ps), (3) unrestrained equilibration (1-5 ns) until system properties (temperature, pressure, energy) stabilize.

Production Simulation: Run unrestrained MD simulations for timescales sufficient to capture relevant conformational changes and catalytic events (typically 100 ns to 1 μs for enzyme active site dynamics), saving coordinates at appropriate intervals (1-100 ps).

Enhanced Sampling (Optional): Apply advanced sampling techniques such as metadynamics, umbrella sampling, or accelerated MD when investigating rare events or constructing free energy landscapes for catalytic steps.

Trajectory Analysis: Analyze simulations for root-mean-square deviations, active site geometries, hydrogen bonding patterns, distance measurements between key atoms, and collective motions using tools such as MDAnalysis, VMD, or GROMACS utilities.

MD simulations have proven particularly valuable for identifying cryptic allosteric sites and elucidating dynamic aspects of catalytic mechanisms that remain inaccessible to static structural methods. For example, MD simulations of branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase (BCKDK) revealed allosteric sites not apparent in X-ray crystal structures, enabling targeted drug discovery efforts [15]. Similarly, simulations of thrombin elucidated conformational changes induced by antagonist binding, providing insights into allosteric regulation mechanisms [15].

Computational Workflow for MD Simulations

Applications in Drug Discovery and Enzyme Engineering

Targeting Enzyme Catalytic Mechanisms for Therapeutic Intervention

The strategic targeting of essential enzyme catalytic mechanisms provides powerful approaches for therapeutic intervention, particularly against pathogenic organisms that rely on metabolic pathways absent in humans. The aspartate biosynthetic pathway represents a compelling example, as this essential route for producing lysine, methionine, threonine, and isoleucine is present in plants and microbes but absent in mammals, enabling selective antimicrobial development [16]. Within this pathway, aspartate β-semialdehyde dehydrogenase (ASADH) catalyzes an early branch point reaction and has emerged as a promising target for antibiotic development.

Structural and mechanistic studies reveal that microbial ASADHs can be divided into three distinct branches (Gram-negative bacteria, Gram-positive bacteria, and archaea/fungi) with significant structural variations in their coenzyme binding loops and dimer interfaces, despite conservation of essential active site residues [16]. These differences enable the potential development of species-specific ASADH inhibitors that selectively target pathogens without affecting beneficial microorganisms. For example, the ASADH from Gram-positive Streptococcus pneumoniae exhibits less than 25% sequence identity with Gram-negative enzymes and lacks the helical subdomain present in E. coli ASADH, creating opportunities for selective inhibitor design [16].

Table 3: Enzyme Targets in Antimicrobial Drug Discovery

| Target Enzyme | Pathway | Organisms | Unique Features | Therapeutic Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASADH | Aspartate biosynthetic pathway | Bacteria, Fungi | Absent in mammals; structural variations between microbial classes | Species-specific inhibitors targeting cofactor binding pocket |

| β-Lactamases | Antibiotic resistance | Drug-resistant bacteria | Multiple unrelated families with different catalytic mechanisms | Mechanism-based inactivators; allosteric modulators |

| BCKDK | Branched-chain amino acid metabolism | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | Cryptic allosteric sites identified through MD simulations | Allosteric inhibitors disrupting kinase activity |

| RNA-dependent RNA polymerase | Viral replication | Hepatitis C virus, SARS-CoV-2 | Two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism | Nucleoside analogs; metal-binding inhibitors |

| HIV-1 integrase | Viral integration | HIV | Two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism | Metal-chelating inhibitors (e.g., Raltegravir) |

The two-metal-ion catalytic mechanism (TCM) employed by numerous metalloenzymes represents another prominent target for therapeutic development. Enzymes such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (HCV, SARS-CoV-2), HIV-1 integrase, influenza cap-dependent endonuclease, and various phosphodiesterases utilize two closely spaced metal ions (typically Mg²⁺ or Mn²⁺) to coordinate and activate substrates during catalysis [13]. Successful therapeutic strategies have included nucleoside analogs that incorporate into growing nucleic acid chains, prodrugs activated by target enzymes, and metal-binding groups that disrupt the essential metal ion clusters, as demonstrated by approved treatments for hepatitis C, COVID-19, and AIDS [13].

Engineering Novel Catalytic Function

The rational design and directed evolution of artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs) represents a frontier in enzyme engineering, combining the catalytic versatility of transition metal complexes with the selectivity and evolvability of protein scaffolds. Recent advances include the construction of dual-cofactor ArMs that incorporate both a transition metal cofactor and an organic or peptide-based cofactor within a single protein scaffold to enable synergistic catalysis [17].

Protocol: Construction of Dual-Cofactor Artificial Metalloenzymes

Scaffold Selection: Choose a stable, well-characterized protein scaffold with known structural data and tolerance to engineering. Streptavidin, with its high affinity for biotin and homotetrameric structure, serves as an excellent platform for creating symmetrical cofactor binding sites.

Primary Cofactor Incorporation: Design and synthesize a biotinylated transition metal complex (e.g., biotin-pendant nickel complex) that anchors with high affinity to the streptavidin vestibule. Characterize binding affinity using isothermal titration calorimetry or surface plasmon resonance.

Secondary Cofactor Installation: Utilize solid-phase peptide synthesis to generate peptide-based cofactors containing catalytic motifs (e.g., imidazole groups for base catalysis, thiols for nucleophilic catalysis) with N-terminal conjugation handles for site-specific attachment to the protein scaffold.

Site-Directed Incorporation: Employ cysteine-maleimide chemistry or unnatural amino acid incorporation to site-specifically conjugate the peptide cofactor to positions邻近 to the transition metal cofactor within the streptavidin tetramer, creating a defined catalytic pocket with both functionalities.

Chemeogenetic Optimization: Implement iterative cycles of rational design and directed evolution to optimize the spatial arrangement and cooperation between cofactors. Focus mutations on residues surrounding both cofactors to fine-tune the active site geometry and electrostatic environment.

Mechanistic Characterization: Employ kinetic analysis, structural methods (X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM), and computational simulations to elucidate the synergistic mechanism and identify rate-limiting steps for further optimization.

This approach has enabled the development of ArMs that catalyze challenging asymmetric transformations such as Michael additions with high enantioselectivity, providing routes to valuable chiral building blocks that complement traditional synthetic methods [17]. The modular nature of this strategy facilitates the creation of ArM libraries with varying metal centers and peptide cofactors, expanding the scope of accessible abiotic reactions.

Engineering Workflow for Artificial Metalloenzymes

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Catalytic Mechanism Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Molecular Biology | Introduction of specific amino acid changes | Functional analysis of catalytic residues (e.g., QuikChange, Q5) |

| High-Throughput Microfluidics (HT-MEK) | Instrumentation | Parallel kinetic analysis of enzyme variants | Comprehensive mutational scanning, folding-activity relationships |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Computational Tools | Simulation of enzyme dynamics and catalysis | Mechanism elucidation, allosteric pathway identification (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) |

| MACiE Database | Bioinformatics | Curated enzyme mechanism database | Mechanism comparison, catalytic motif identification, evolutionary analysis |

| CoFactor Database | Bioinformatics | Organic cofactor structure and function | Cofactor diversity analysis, conformational variation studies |

| Artificial Metalloenzyme Components | Synthetic Biology | Modular parts for engineered enzymes | Creation of novel biocatalysts (e.g., biotinylated metal complexes, streptavidin variants) |

| Metadynamics Algorithms | Computational Tools | Enhanced sampling of conformational space | Free energy calculations, rare event sampling (e.g., Plumed) |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Substrates | Analytical Chemistry | Tracing reaction pathways and mechanisms | Kinetic isotope effects, intermediate identification |

| Rapid Kinetics Instruments | Instrumentation | Monitoring fast enzymatic reactions | Pre-steady-state kinetics, transient state characterization (e.g., stopped-flow, quench-flow) |

| Crystallization Screening Kits | Structural Biology | Obtaining enzyme-ligand complex structures | Active site architecture determination, inhibitor binding modes |

Decoding the intricate relationships between enzyme structure, catalytic mechanism, and function provides the fundamental knowledge required for rational manipulation of enzymatic activity. The integrated application of experimental methodologies such as site-directed mutagenesis and high-throughput kinetics with computational approaches including molecular dynamics simulations and enhanced sampling techniques enables researchers to move beyond static structural descriptions to dynamic mechanistic understanding. These insights directly enable innovative therapeutic strategies targeting essential pathogen enzymes and engineering novel biocatalysts for synthetic applications. As these methodologies continue to advance, particularly in the realms of single-molecule enzymology, quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) simulations, and machine learning-assisted enzyme design, researchers will gain increasingly sophisticated tools for deciphering and engineering the remarkable catalytic capabilities of enzymes.

In the rational design of enzyme active sites, achieving the catalytic proficiency of natural enzymes remains a formidable challenge. While computational design has produced novel enzymes, such as Kemp eliminases, their initial catalytic efficiencies often fall orders of magnitude short of their natural counterparts [18]. A key differentiator of natural enzymes is the presence of evolutionarily conserved motifs—critical clusters of amino acids that are preserved across species due to their fundamental role in structure and function. Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA) serves as a primary bioinformatics technique for uncovering these motifs, providing a window into millions of years of evolutionary optimization [19]. This Application Note details practical protocols for using MSA to mine conserved motifs, providing a data-driven strategy to inform and enhance the rational design of enzyme active sites.

The following table catalogs key reagents, software, and data resources essential for conducting MSA-based conserved motif discovery.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MSA and Motif Discovery

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in MSA/Motif Discovery | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| NCBI MSA Viewer | Software Tool | Web-based visualization of alignments from BLAST or custom files [20]. | Integrated with NCBI databases; allows setting anchor sequences and calculating percent identity [20] [21]. |

| Jalview | Software Tool | Desktop alignment editing, visualization, and analysis [22]. | Open-source; can generate phylogenetic trees and Principal Component Analysis plots; links to 3D structure viewers [23] [22]. |

| M-Coffee | Software Tool | Meta-alignment method that combines results from multiple aligners [19]. | Improves alignment quality by generating a consensus from different tools like MUSCLE and MAFFT [19]. |

| ESM2 (Evolutionary Scale Model) | Computational Model | Protein language model that predicts evolutionary constraints from single sequences [24]. | Identifies mutation-resistant residues in intrinsically disordered regions without needing multiple sequence alignments [24]. |

| FuncLib | Software Tool | Computational design of stable and diverse enzyme variants [25]. | Uses evolutionary data and Rosetta to design mutant libraries with focused diversity [25]. |

| Non-Redundant Protein Database | Data Resource | Source of diverse protein sequences for constructing alignments. | Found within NCBI and UniProt; crucial for capturing broad evolutionary relationships. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Data Resource | Repository of 3D protein structures [26]. | Used to validate and visualize the structural context of discovered motifs. |

Workflow for Mining Conserved Motifs via MSA

The process of extracting biologically meaningful conserved motifs from sequences involves a structured workflow, from data collection to functional validation. The diagram below outlines the key stages and decision points.

Figure 1: A workflow for mining conserved motifs from multiple sequence alignments.

Protocol: MSA-Based Identification of Conserved Active Site Motifs

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for identifying conserved motifs relevant to enzyme active sites, using the NCBI MSA Viewer [20].

Data Collection and Alignment

- Sequence Retrieval: Begin with a query protein sequence of interest. Use BLASTP against the non-redundant protein database to identify homologous sequences. Filter results to include a diverse yet evolutionarily relevant set of sequences (e.g., from different taxonomic families).

- Alignment Generation: Submit the collected sequences to a multiple sequence alignment program. MUSCLE, MAFFT, or ClustalOmega can be used. For critical projects, generate several independent alignments using different algorithms and parameters.

Alignment Post-Processing and Quality Control

- Meta-Alignment: To improve accuracy, use a meta-alignment tool like M-Coffee. Provide the alignments from step 1.2 as input. M-Coffee constructs a consistency library from all input alignments and produces a consensus alignment, which often has higher quality than any single input [19].

- Realigner Application (Optional): For further refinement, use a realigner tool like RASCAL. This tool employs horizontal partitioning strategies (e.g., single-type partitioning) to iteratively remove and realign sequences against a profile of the remaining sequences, correcting local mis-alignments [19].

Visualization and Motif Identification in NCBI MSA Viewer

- Upload and Navigate: Upload the final, post-processed alignment file (in FASTA format) to the NCBI MSA Viewer [20]. Use the Panorama view at the top to get an overview of conservation along the entire sequence. Red regions indicate high mismatch frequencies, while gray indicates consensus.

- Set an Anchor Sequence: Hover over the row containing your query enzyme sequence, right-click, and select "Set as anchor." This action locks your sequence of interest as the top row, and all conservation calculations and mismatches will be reported relative to it [20].

- Identify the Conserved Motif:

- Visually scan the alignment for columns with few or no mismatches, indicating perfect conservation.

- Use the "Show consensus" option (available after unsetting the anchor) to display a consensus row. The consensus sequence is calculated as the residue found in ≥70% of sequences, using IUPAC ambiguity codes if needed [20].

- Enable the "Percent Identity" column via the "Columns" settings dialog. This quantitatively shows, for each sequence, the percentage of residues that match the anchor/consensus sequence, highlighting the most conserved sequences in your set [20].

- A conserved motif is typically a run of several perfectly or highly conserved columns interspersed with less conserved positions.

Connecting Conserved Motifs to Enzyme Design

The conserved motifs discovered through MSA are not merely academic; they provide a blueprint for engineering efficient enzymes.

Protocol: From Motif to Mutagenesis in Rational Design

- Map Motif to Structure: Retrieve the 3D structure of your enzyme (or a close homolog) from the PDB. Using visualization software (e.g., PyMOL, Chimera), map the amino acid positions of the discovered motif onto the structure. Determine if the motif constitutes the known active site or a potential distal regulatory site.

- Incorporate into Computational Design: Use the conserved motif as a positional constraint in computational design tools.

- In Rosetta-driven design, the motif residues can be fixed during the sequence design process to ensure the preservation of critical catalytic or structural elements [25].

- Tools like FuncLib use evolutionary information from homologous proteins to suggest mutation sites. A discovered conserved motif can be used to validate or prioritize the residues that FuncLib suggests should remain unchanged, leading to a focused, high-quality mutant library [25].

- Experimental Validation: Clone the gene encoding your wild-type and designed variants. Perform site-directed mutagenesis to create control mutants where critical residues in the conserved motif are altered. Purify the proteins and compare their catalytic efficiency ((k{cat}/KM)) and thermal stability to the wild-type and designed variants. This step confirms the functional importance of the motif [18].

Advanced Integration: Protein Language Models

A recent advancement complements MSA by using protein language models (pLMs) like ESM2. These models, trained on millions of sequences, can predict evolutionary constraints from a single sequence, bypassing the need for explicit MSA. This is particularly powerful for analyzing intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which are difficult to align but can contain conserved motifs critical for functions like phase separation [24].

Table 2: Comparison of MSA and Protein Language Models for Motif Discovery

| Feature | Traditional MSA Approach | Protein Language Model (e.g., ESM2) |

|---|---|---|

| Data Input | Requires a large, diverse set of homologous sequences. | Requires only a single protein sequence. |

| Principle | Identifies conservation via explicit cross-species comparison. | Identifies evolutionary constraints learned from sequence statistics across UniProt. |

| Best For | Structured domains with clear homologs. | Disordered regions, orphan sequences, or as a rapid initial scan. |

| Advantages | Intuitive, visual, and directly linked to phylogeny. | Fast, avoids alignment artifacts, captures deeper correlations. |

| Limitations | Quality depends on homolog availability and alignment accuracy. | A "black box"; harder to interpret the source of constraint. |

Application Protocol: Run your enzyme sequence through the ESM2 model to obtain a per-residue mutational tolerance score. Residues with low mutational tolerance are predicted to be evolutionarily constrained. Correlate these positions with the conserved columns identified from your MSA. The convergence of both methods provides exceptionally high confidence for targeting these residues in design [24].

Multiple Sequence Alignment remains a cornerstone technique for decoding the evolutionary lessons embedded in protein sequences. By following the detailed protocols outlined herein—from rigorous alignment post-processing and visualization to the integration of cutting-edge protein language models—researchers can reliably identify conserved motifs that are critical for enzyme function. Applying these evolutionarily-derived constraints to rational design platforms, such as FuncLib and Rosetta, provides a powerful strategy to bridge the efficiency gap between designed and natural enzymes, ultimately enabling the creation of more stable and efficient biocatalysts for industrial and therapeutic applications.

The classical view of enzymes as rigid molecular locks, where static structures perfectly complement transition states, has been fundamentally revised. Contemporary research reveals that enzymes are inherently dynamic machines, whose catalytic efficiency is profoundly influenced by their constant structural motions [27] [28]. Rather than merely providing a passive scaffold, proteins actively harness environmental energy through conformational fluctuations, converting thermal noise into productive chemical work [27]. This paradigm shift reconceptualizes enzymes as dynamic energy converters, where structural flexibility is not incidental but central to function.

Proteins in solution undergo continuous deformation from collisions with water molecules, generating potential energy that can be focused toward catalytic sites [28]. These dynamics occur across multiple timescales, from fast bond vibrations (picoseconds) to slower domain movements and protein folding events (hours) [29]. The resulting conformational ensembles—multiple structural states sampled by a single enzyme—directly modulate substrate binding, transition state stabilization, and product release [30] [31]. This dynamic view provides a more comprehensive framework for understanding biological catalysis and enables innovative strategies in enzyme engineering and drug development.

Theoretical Foundations: Molecular Mechanisms of Dynamic Catalysis

Energy Conversion Through Protein Dynamics

The dynamic energy conversion model posits that enzymes utilize thermal energy from their environment to drive catalysis through three fundamental mechanisms:

- Energy Absorption: Proteins constantly absorb kinetic energy through collisions with solvent molecules (Brownian motion), occurring at frequencies of 10⁹–10¹² times per second [28]. This provides a continuous energy input that maintains structural dynamics essential for function.

- Energy Storage and Transduction: Secondary structural elements, particularly α-helices and β-sheets, act as sophisticated energy transduction elements [27]. Their regular hydrogen-bonding patterns and structural rigidity enable efficient storage of potential energy through bending and stretching modes [28].

- Energy Utilization at Active Sites: The stored potential energy is directed to catalytic centers, where it contributes to reducing activation barriers (typically by 20–40 kJ/mol in enzymatic reactions) by facilitating bond strain, transition state stabilization, and necessary conformational changes [28].

This model explains why excessive rigidity often diminishes catalytic activity and accounts for the temperature dependence of enzyme function through its relationship to molecular motion frequency [28].

Allosteric Communication and Conformational Landscapes

Allosteric regulation represents a quintessential example of dynamics-mediated control, where ligand binding at sites distal from the active site modulates enzyme activity through propagated conformational changes [15]. Advanced computational analyses reveal that allosteric proteins exist as ensembles of pre-existing conformational states, with effector binding shifting the equilibrium between these states rather than inducing entirely new conformations [15].

Studies on the Hsp90 chaperone system demonstrate how diverse regulatory inputs—including point mutations, cochaperone binding, and macromolecular crowding—can produce similar thermodynamic outcomes (stabilizing closed conformations) through distinct dynamic mechanisms [31]. Single-molecule FRET experiments revealed that while these modulations similarly shifted Hsp90's conformational equilibrium toward closed states, they exhibited fundamentally different underlying kinetics and transition pathways [31]. This illustrates how enzymes fine-tune function through conformational flexibility, employing diverse dynamic strategies to achieve similar functional outcomes.

Experimental Approaches: Capturing Enzymes in Motion

Methodologies for Studying Enzyme Dynamics

Table 1: Experimental Techniques for Characterizing Enzyme Dynamics

| Technique | Spatiotemporal Resolution | Key Applications | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-molecule FRET | ~1-10 nm, ms-s timescale [31] | Real-time conformational kinetics, population distributions | Hsp90 alternates between open/closed states even without ATP; different regulators shift equilibrium via distinct kinetic pathways [31] |

| Cryo-EM with Heterogeneity Analysis | ~3-4 Å, multiple conformations from single samples [30] | Visualization of conformational ensembles, rare states | Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme (ACE) samples open, intermediate, and closed states; N-domain more flexible than C-domain [30] |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Atomic detail, fs-µs timescale [15] [28] | Atomic-level trajectory analysis, hidden state identification | Reveals cryptic allosteric sites in BCKDK; maps energy landscapes and conformational transitions [15] |

| Enhanced Sampling Methods | Accelerated exploration of rare events [15] | Free energy calculations, transition pathway mapping | Metadynamics and umbrella sampling identify hidden allosteric pockets and conformational transitions [15] |

Application Note: Protocol for Mapping Conformational Landscapes via Cryo-EM

Objective: To characterize the conformational ensemble of a multi-domain enzyme and identify distinct functional states.

Background: Cryo-EM with advanced computational analysis enables visualization of multiple conformational states from a single sample by preserving enzymes in vitreous ice, capturing native structural heterogeneity [30].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Cry-EM Conformational Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Soluble enzyme construct | Maintains native dynamics while facilitating grid preparation | Soluble ACE homodimer used to study domain movements [30] |

| Vitrified ice grids | Preserves native protein conformations without crystalline artifacts | QUANTIFOIL grids with ultra-thin carbon support [30] |

| Reference datasets | Enable accurate particle picking and 3D reconstruction | EMPIAR-XXXXX dataset for initial model generation |

| 3D variability analysis software | Resolves continuous conformational changes from particle images | CryoSPARC's 3DVA tool for analyzing domain movements [30] |

| Molecular dynamics simulations | Provides atomic-level insights into transitions between observed states | GROMACS/AMBER for simulating opening/closing transitions [30] |

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation and Grid Freezing:

- Express and purify the soluble enzyme construct (e.g., ACE-N and ACE-C domains)

- Apply 3-4 μL of enzyme solution (0.5-2 mg/mL) to glow-discharged cryo-EM grids

- Blot and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot (2-6 second blot time, 100% humidity)

- Confirm ice quality by screening grids for appropriate thickness and homogeneity

Data Collection:

- Collect ~3,000-8,000 micrographs using a 300 keV cryo-electron microscope

- Use defocus range of -0.8 to -2.5 μm and total exposure dose of ~40-60 e⁻/Ų

- Implement multi-shot acquisition strategy with beam-image shift

Image Processing and Heterogeneity Analysis:

- Perform motion correction and CTF estimation for all micrographs

- Pick ~500,000-2,000,000 particles using template-based or neural network approaches

- Conduct multiple rounds of 2D and 3D classification to remove poor-quality particles

- Generate an initial 3D reconstruction using homogeneous particle subsets

- Apply 3D variability analysis to resolve continuous conformational changes

- Use masked classification focused on flexible regions to isolate distinct states

Model Building and Refinement:

- Build atomic models into each major conformational state

- Conduct molecular dynamics simulations to analyze transitions between states

- Calculate inter-domain distances and angles to quantify conformational differences

Troubleshooting:

- For preferred orientation, use graphene oxide grids or add detergents during grid preparation

- If conformational states remain unresolved, apply higher regularization parameters in 3DVA

- When flexible regions appear poorly resolved, use localized reconstruction with soft masks

Figure 1: Cryo-EM Workflow for Conformational Analysis

Computational Protocols for Dynamic Analysis

Application Note: Identifying Allosteric Sites via Molecular Dynamics

Objective: To identify cryptic allosteric sites and analyze allosteric communication pathways using molecular dynamics simulations.

Background: MD simulations provide atomic-level insights into enzyme dynamics on timescales relevant to catalysis and allosteric regulation, revealing conformational states inaccessible to static structural methods [15].

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Obtain initial coordinates from PDB or AlphaFold2 prediction

- Solvate the enzyme in a water box (e.g., TIP3P model) with 10-15 Å padding

- Add ions to neutralize system and achieve physiological salt concentration (150 mM NaCl)

- Perform energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm (5000 steps maximum)

Equilibration Protocol:

- Conduct 100 ps NVT equilibration with position restraints on protein heavy atoms (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²)

- Perform 100 ps NPT equilibration with semi-isotropic pressure coupling and maintained position restraints

- Gradually release position restraints in 2-3 stages with reduced force constants

Production Simulation:

- Run unrestrained MD for 100 ns-1 μs using 2-fs time steps

- Maintain temperature at 300 K using Nosé-Hoover thermostat

- Control pressure at 1 bar using Parrinello-Rahman barostat

- Employ particle mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics

Enhanced Sampling (Optional):

- Apply metadynamics to accelerate sampling of specific collective variables (e.g., domain distances, dihedral angles)

- Use variational enhanced sampling (VES) for optimizing bias potentials

- Implement replica exchange MD (REMD) for improved conformational sampling

Trajectory Analysis:

- Calculate root mean square deviation (RMSD) and fluctuation (RMSF) to identify flexible regions

- Perform principal component analysis (PCA) to extract essential dynamics

- Use dynamic cross-correlation analysis to identify coupled motions

- Apply community network analysis to map allosteric pathways

- Utilize pocket detection algorithms (e.g., MDpocket) to identify transient cavities

Key Analysis Tools: GROMACS/AMBER for simulations, MDTraj for analysis, PyEMMA for Markov state models, Carma for vibrational analysis.

Figure 2: MD Workflow for Allosteric Site Discovery

Machine Learning-Guided Engineering of Dynamic Enzymes

Objective: To engineer enzyme variants with enhanced catalytic activity by combining high-throughput screening with machine learning prediction.

Background: ML models trained on sequence-function data can predict higher-order mutants with improved activity, dramatically reducing the experimental screening burden [32].

Procedure:

- Library Design and Construction:

- Select target residues (e.g., active site, substrate tunnels within 10 Å of docked substrates)

- Generate site-saturation mutagenesis libraries using cell-free DNA assembly

- Use primer-based mutagenesis with DpnI digestion of parent plasmid

- Amplify linear expression templates (LETs) for cell-free expression

High-Throughput Screening:

- Express enzyme variants using cell-free protein synthesis (CFE)

- Perform functional assays directly in expression mixture

- Use low enzyme loading (∼1 μM) and high substrate concentration (25 mM) to approximate industrial conditions

- Measure conversion rates via HPLC, MS, or absorbance assays

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Collect sequence-function data for 1,000+ variants

- Use site-specific one-hot encodings as feature vectors

- Train augmented ridge regression models with evolutionary zero-shot predictors

- Validate models using cross-validation and holdout test sets

Prediction and Validation:

- Predict fitness of higher-order mutants (double, triple mutants)

- Synthesize and test top-predicted variants

- Iterate with additional rounds of design-build-test-learn cycles

Case Study Application: Engineering amide synthetases (McbA) for pharmaceutical synthesis demonstrated 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity across nine compounds using this approach [32].

Applications in Rational Enzyme Design

Targeting Conformational Ensembles in Drug Discovery

The recognition of enzyme dynamics has profound implications for pharmaceutical development. Allosteric drugs targeting dynamic sites offer enhanced specificity and reduced off-target effects compared to traditional active-site inhibitors [15]. Computational methodologies now enable systematic identification and characterization of allosteric sites, with successful applications to therapeutic targets including Sirtuin 6 (SIRT6) and MAPK/ERK kinase (MEK) [15].

Table 3: Quantitative Improvements in Engineered Enzymes via Dynamic Design

| Enzyme/System | Engineering Approach | Catalytic Improvement | Key Dynamic Insight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Designed serine hydrolases | AI-driven de novo design with catalytic preorganization assessment | Efficient ester bond cleavage exceeding prior designs | Close match between designed and experimental structures (<1 Å deviation) [33] |

| Amide synthetase (McbA) | ML-guided engineering based on sequence-function landscapes | 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for pharmaceutical synthesis | Residue interactions governing substrate tunnel dynamics [32] |

| Hsp90 chaperone | Conformational confinement through mutations and crowding | ~4-fold ATPase amplification via stabilized closed states | Long-range communication between C-terminal mutation and N-terminal active site [31] |

| Redox-active MOF-enzyme platforms | Rational MOF design to mediate electron transfer | 100% current retention over 54 hours vs. complete loss in adsorbed systems | Enhanced durability through dynamic complex stabilization [34] |

Engineering Dynamic Enzyme-Material Hybrids

Rational design of enzyme-support systems that accommodate and leverage protein dynamics represents an emerging frontier. The development of redox-active metal-organic frameworks (raMOFs) for mediated electron transfer demonstrates how dynamic interfaces can dramatically enhance operational stability [34]. A cobalt-based raMOF incorporating 1,2-naphthoquinone-4-sulfonate mediators maintained 100% current density over 54 hours, far exceeding the stability of directly adsorbed mediators [34]. This illustrates the importance of designing support systems that complement enzyme dynamics rather than restricting essential motions.

The paradigm of enzymes as dynamic energy converters has transformed our fundamental understanding of biological catalysis and opened new frontiers in enzyme engineering. By viewing catalytic efficiency as an emergent property of conformational ensembles rather than static structures, researchers can now design interventions that fine-tune protein dynamics to achieve desired functional outcomes [31] [28].

Future advances will likely focus on several key areas: improved computational methods for predicting long-timescale dynamics, experimental techniques for characterizing high-energy states, and integrated frameworks that connect molecular motions to catalytic outcomes across multiple timescales. The integration of machine learning with biophysical experimentation promises to accelerate the exploration of sequence-dynamics-function relationships [32], while continued development of dynamic structural biology methods will provide unprecedented views of enzymes in action [30].

For researchers engaged in rational enzyme design, these developments suggest a strategic shift from targeting single structures to manipulating conformational landscapes, from rigid immobilization to dynamic interfacing, and from static active-site optimization to allosteric network engineering. By embracing the dynamic nature of enzymes, the next generation of biocatalysts can be engineered with precision that matches the sophisticated molecular machines found in nature.

Computational and Experimental Tools for Active Site Engineering

Site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) stands as a cornerstone technique in molecular biology, enabling researchers to make precise, targeted changes to DNA sequences. Within rational enzyme design, SDM provides the critical experimental link between in silico predictions and functional validation, allowing scientists to test hypotheses about active site residues, catalytic mechanisms, and structure-function relationships. By systematically altering specific amino acids in enzyme active sites, researchers can probe the molecular determinants of catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and stability. This targeted approach contrasts with random mutagenesis methods, offering unparalleled precision for elucidating enzyme mechanism and engineering improved biocatalysts for industrial, pharmaceutical, and research applications. The integration of computational design strategies with robust experimental mutagenesis protocols has dramatically accelerated the pace of enzyme engineering, making it possible to create novel enzymes with tailored properties for specific biotechnological needs.

Key Principles and Quantitative Foundations

Chemical and Molecular Basis of Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Site-directed mutagenesis relies on the fundamental principles of DNA replication and enzymatic manipulation. The core process involves using synthetic oligonucleotide primers containing desired mutations to amplify target DNA sequences via PCR. The method capitalizes on the ability of DNA polymerase to extend these primers, incorporating the mutation into the newly synthesized strand. Following amplification, the methylated parental DNA template is selectively digested using DpnI restriction enzyme, which cleaves only at methylated sites, leaving the newly synthesized, unmethylated mutant strands intact for subsequent transformation and expression [35] [36] [37].

This technique enables various types of precise genetic modifications:

- Point mutations: Single amino acid substitutions to probe active site residues

- Insertions: Adding sequences to introduce novel functional elements

- Deletions: Removing sequences to simplify structure or eliminate competing functions

Quantitative Insights from Large-Scale Mutagenesis Studies

Large-scale analyses of mutagenesis data provide empirical guidance for rational enzyme design. A comprehensive study of 34,373 mutations across 14 proteins revealed significant variation in how different amino acid substitutions impact protein function [38].

Table 1: Amino Acid Substitution Tolerance and Representativeness

| Amino Acid | Tolerance Ranking | Representativeness | Utility for Interface Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methionine | Most tolerated | Moderate | Limited |

| Proline | Least tolerated | Low | Moderate |

| Histidine | Moderate | Highest | Limited |

| Asparagine | Moderate | High | High |

| Aspartic Acid | Low | Low | Highest |

| Glutamic Acid | Low | Low | Highest |

| Alanine | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate |

The study found that histidine and asparagine substitutions best recapitulated the effects of other substitutions, even when wild-type amino acid identity or structural context was considered. Conversely, highly disruptive substitutions like aspartic acid and glutamic acid demonstrated the greatest discriminatory power for identifying ligand-binding interface positions—a critical consideration for enzyme active site engineering [38].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Standard Site-Directed Mutagenesis Protocol

The following protocol adapts and synthesizes established methodologies from multiple sources [35] [36] [37], optimized for engineering enzyme active sites.

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Site-Directed Mutagenesis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function/Purpose | Specific Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Template DNA | Target for mutation | 25 ng/μL in sterile buffer |

| High-fidelity DNA Polymerase | PCR amplification | Q5 Hot Start, KOD Xtreme, or PfuTurbo |

| Mutagenic Primers | Introduce mutation | 12-18 bases flanking mutation on both sides |

| dNTP Mix | Nucleotide substrates for PCR | 2 mM concentration |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digest parental template | Selective cleavage of methylated DNA |

| Competent E. coli Cells | Transformation | High-efficiency DH5α or NEB 5-alpha |

| SOC Medium | Outgrowth after transformation | Enhanced recovery vs. LB medium |

| Agar Plates with Antibiotic | Selection | Appropriate for plasmid resistance |

Primer Design Considerations

Effective primer design is the most critical factor for successful mutagenesis [35]:

- Primers should contain the desired mutation in the center

- 12-18 complementary bases should flank both sides of the mutation

- Forward and reverse primers should have similar melting temperatures

- For Q5-based protocols, standard primers can be used without phosphorylation

- Primers longer than 40-50 nucleotides should be PAGE-purified to minimize synthesis errors

- Online tools like NEBaseChanger can calculate optimal annealing temperatures accounting for mismatched nucleotides [35]

Step-by-Step Protocol

PCR Amplification

- Set up reaction mixture on ice:

- 25 μL of 2X reaction buffer

- 10 μL autoclaved water (volume adjustable based on template concentration)

- 10 μL dNTPs (2 mM)

- 2 μL template DNA (25 ng/μL)

- 1 μL forward primer

- 1 μL reverse primer

- 1 μL high-fidelity DNA polymerase (added last)

- Total reaction volume: 50 μL

- PCR conditions [37]:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: Tm of primers -5°C for 30 seconds

- Extension: 68°C for 1 minute per kb of plasmid length

- Repeat steps 2-4 for 18-30 cycles

- Final extension: 68°C for 5 minutes

- Set up reaction mixture on ice:

DpnI Digestion

- Add 5 μL CutSmart Buffer directly to PCR product

- Add 1 μL DpnI restriction enzyme

- Mix gently by brief centrifugation

- Incubate at 37°C for 15 minutes to 1 hour [37]

Transformation

- Thaw competent cells on ice for 5-10 minutes

- Add entire PCR product to competent cells

- Mix by gentle tapping (no vortexing or pipetting)

- Incubate on ice for 10-15 minutes

- Heat shock at 42°C for 40-45 seconds

- Immediately return to ice for 2 minutes

- Add 500 μL SOC medium

- Incubate at 37°C with shaking (250 rpm) for 1 hour

Selection and Screening

- Spread transformation mixture on agar plates with appropriate antibiotic

- Incubate at 37°C for 16-18 hours

- Select multiple colonies for screening

- Verify mutations by sequencing before further use

Figure 1: Site-Directed Mutagenesis Experimental Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in a standard SDM protocol, from primer design through verification of the final mutant construct.

Advanced Applications in Enzyme Engineering

Modern enzyme engineering leverages SDM within sophisticated computational-design frameworks:

Structure-Based Design: Identifying key active site residues through analysis of catalytic mechanisms and binding pocket architecture [39]

Sequence-Based Design: Utilizing homology modeling and deep learning-based structure prediction when crystal structures are unavailable [39]

Data-Driven Machine Learning Approaches: Leveraging large datasets to predict mutation effects and guide library design [39] [40]

The integration of these computational approaches with SDM has enabled remarkable achievements in enzyme engineering, including the development of enzymes with novel catalytic activities, improved stability, and altered substrate specificity [39].

Integration with Rational Enzyme Design Strategies

Computational-Guided Mutagenesis for Enzyme Optimization

Rational enzyme design employs computational strategies to identify target residues for mutagenesis, dramatically reducing experimental screening efforts:

Figure 2: Computational-Experimental Integration for Enzyme Design. This diagram illustrates the iterative cycle of computational prediction and experimental validation that accelerates rational enzyme engineering.

Structure-based computational design relies on detailed structural information to identify residues critical for catalysis, substrate binding, or protein stability. This approach has successfully guided the engineering of enzyme activity, specificity, and stability by targeting specific positions within active sites or allosteric networks [39].

Sequence-based methods leverage evolutionary information and homology modeling to identify functionally important residues, particularly valuable when high-resolution structures are unavailable. These approaches include:

- Consensus design based on sequence alignments of homologous enzymes

- Statistical coupling analysis to identify co-evolving residues

- Phylogenetic analysis to trace functional diversification [39]

Machine learning approaches represent the cutting edge of enzyme design, with models like ProDomino enabling prediction of domain insertion sites and allosteric regulation patterns [40]. These data-driven methods can generalize beyond known protein families, accelerating the creation of novel enzyme functions.

Practical Considerations for Enzyme Active Site Engineering

When applying SDM to enzyme active site engineering:

Conservation Analysis: Target residues that are evolutionarily conserved across homologs often play critical functional roles

Mechanistic Understanding: Base mutations on established catalytic mechanisms to avoid non-productive changes

Structural Constraints: Consider steric and electrostatic effects when introducing substitutions

Multivariate Optimization: Recognize that combinations of mutations may have non-additive effects due to epistasis

High-Throughput Screening: Implement efficient screening methods to characterize mutant libraries, especially when exploring multiple positions

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Common challenges in site-directed mutagenesis and their solutions:

- Low mutation efficiency: Verify primer design, increase template quality, optimize annealing temperature

- Primer-dimer formation: Reduce primer concentration, redesign primers with less complementarity

- No transformants: Check competent cell efficiency, verify antibiotic selection, confirm complete DpnI digestion

- Unexpected mutations: Use high-fidelity polymerases, sequence entire gene for unwanted substitutions

- Poor plasmid yield: Increase outgrowth time, use high-quality SOC medium, optimize transformation protocol

For enzyme engineering applications, always verify mutations by sequencing the entire target region and confirm functional effects through appropriate biochemical assays to ensure observed phenotypic changes result from intended modifications rather than unintended mutations.

The Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit and similar commercial systems can significantly streamline the process, providing optimized protocols, high-fidelity polymerases, and efficient circularization methods that reduce hands-on time to less than 2 hours for most applications [41].

Leveraging Steric Hindrance and Remodeling Interaction Networks to Control Activity and Selectivity

The rational design of enzyme active sites represents a frontier in biocatalysis, enabling the precise engineering of proteins for applications in synthetic chemistry, therapeutics, and industrial bioprocessing. Two powerful and complementary strategies in this domain are the manipulation of steric hindrance and the remodeling of interaction networks. Steric hindrance engineering strategically introduces or removes bulky residues near the active site to physically control substrate access, product release, or intermediate stabilization, thereby directly influencing activity and stereoselectivity. Conversely, interaction network remodeling involves reprogramming the intricate web of non-covalent bonds—including hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and van der Waals forces—within the catalytic environment to alter transition state stabilization, substrate orientation, and conformational dynamics. Framed within the broader context of rational enzyme design research, this article provides detailed application notes and protocols for implementing these strategies, supported by contemporary case studies and quantitative data.

Core Principles and Experimental Approaches

Strategic Framework for Active Site Engineering

The selection between steric hindrance and interaction network remodeling is guided by the specific catalytic property targeted for improvement. The following table outlines the primary applications and design considerations for each strategy.

Table 1: Strategic Framework for Enzyme Engineering

| Engineering Strategy | Primary Application | Typical Target Sites | Key Design Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Steric Hindrance | Controlling substrate specificity; enhancing enantioselectivity; blocking undesirable side reactions | Substrate binding pocket; substrate access channels; near the catalytic residues | Size and stereochemistry of introduced side chains; potential for creating overly restrictive barriers that abolish activity |

| Remodeling Interaction Networks | Improving catalytic activity (kcat); altering cofactor specificity; stabilizing transition states; fine-tuning substrate positioning | First- and second-shell residues surrounding the substrate; residues involved in proton relay networks | Energetics of hydrogen bonding; charge complementarity; maintaining optimal catalytic base/acid geometry |

Workflow for Rational Enzyme Design