The Hydrophobic Effect in Protein Folding: From Fundamental Driver to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the hydrophobic effect as a central driving force in protein folding, synthesizing foundational principles with current research debates and methodological advances.

The Hydrophobic Effect in Protein Folding: From Fundamental Driver to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of the hydrophobic effect as a central driving force in protein folding, synthesizing foundational principles with current research debates and methodological advances. It examines the historical context and thermodynamic basis of hydrophobicity, critiques the classical 'oil drop' model in light of modern structural data, and discusses the competing roles of backbone solvation and side-chain interactions. The content further details computational methods for predicting hydrophobicity and folding, explores challenges in force field accuracy and sampling, and validates concepts through applications in drug discovery, particularly in targeting protein-protein interactions. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review connects fundamental biophysical principles to therapeutic design, highlighting future directions for the field.

The Hydrophobic Effect: Unraveling the Fundamental Driver of Protein Folding

The hydrophobic effect is widely recognized as a fundamental driving force in protein folding, molecular recognition, and drug design [1] [2]. This in-depth technical guide traces the historical development of this concept from its initial empirical observations in anesthesia to its formalization as a quantitative principle in biochemistry. The journey begins with the seminal work of Meyer and Overton, who first correlated lipid solubility with biological activity, and culminates with Kauzmann's profound insight into the role of "hydrophobic bonds" in stabilizing protein structures [2] [3]. Understanding this historical progression is essential for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to comprehend the physical forces that govern biomolecular interactions and stability. This document frames these developments within the broader context of protein folding research, examining both the classical theories and emerging challenges to established paradigms.

The Meyer-Overton Era: Foundations in Anesthesia Research

Empirical Beginnings and Historical Context

At the turn of the 20th century, Hans Meyer and Charles Overton independently made a crucial discovery that would lay the groundwork for understanding hydrophobic interactions in biological systems. Their research, conducted between 1899 and 1901, demonstrated a striking correlation between the lipophilicity of chemical compounds and their anesthetic potency [2] [4]. This Meyer-Overton rule proposed that the effectiveness of an anesthetic agent was directly proportional to its lipid solubility, suggesting that these substances exerted their effects by interacting with lipid components of biological systems [4]. This represented one of the first quantitative relationships established between a compound's physicochemical properties and its biological activity.

Experimental Basis and Methodological Approaches

The experimental foundation of the Meyer-Overton rule was based on partition coefficient measurements, which quantified how a compound distributes itself between oil and water phases [2]. Although the exact methodologies employed by Meyer and Overton were not explicitly detailed in the search results, their work established the fundamental principle that biological activity could be predicted by a simple physicochemical parameter - the preference of a compound for a nonpolar environment over an aqueous one. This observation was particularly remarkable given that the molecular structures of neuronal membranes and proteins were unknown at the time. Their findings suggested that anesthetic potency was primarily determined by a compound's ability to dissolve in hydrophobic environments, implicitly highlighting the importance of water exclusion in biological interactions.

Table 1: Key Historical Experiments on Hydrophobic Interactions

| Investigator(s) | Time Period | Key Finding | Experimental System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Meyer and Overton | 1899-1901 | Correlation between lipid solubility and anesthetic potency | Oil-water partitioning |

| Frank and Evans | 1945 | "Iceberg" model of water structure around nonpolar solutes | Thermodynamic measurements |

| Kauzmann | 1959 | Concept of "hydrophobic bond" in protein stability | Protein denaturation studies |

| Némethy, Scheraga, and Steinberg | 1960s | Temperature dependence of hydrophobic interactions | Theoretical modeling |

The Iceberg Model and Early Theoretical Frameworks

Following the observations of Meyer and Overton, the mid-20th century saw significant advances in understanding the molecular basis of hydrophobic phenomena. In 1945, Frank and Evans proposed the "iceberg" model to explain the behavior of water in the presence of nonpolar solutes [1] [2]. According to this model, water molecules form structured "cage-like" arrangements around hydrophobic solutes, resembling the clathrate structures found in gas hydrates [1]. This concept provided a physical explanation for the large negative entropy change observed when nonpolar compounds were dissolved in water.

The iceberg model was subsequently extended to proteins by Klotz, who invoked this concept to explain various biochemical phenomena including pKa shifts, molecular volume changes, denaturation processes, and the altered behavior of protein functional groups in aqueous environments [2]. The key thermodynamic implication was that when hydrophobic molecules associate, some of these structured water molecules are released into the bulk solvent, resulting in an entropy increase that drives the association process [2] [5]. This release of constrained water molecules from the solute-solvent interface to the bulk aqueous phase represented an entropically favorable process that could explain the driving force for hydrophobic associations.

Diagram 1: Frank and Evans' "Iceberg" Model of Hydrophobic Hydration. The association of nonpolar solutes reduces the total structured water shell, releasing water molecules to the bulk and increasing entropy.

Kauzmann's Hydrophobic 'Bond': A Paradigm for Protein Folding

Conceptual Foundation and Terminology

In 1959, Walter Kauzmann published his seminal review article that would fundamentally shape the understanding of protein stability for decades to come [2] [3]. Drawing upon the earlier concepts of Frank and Evans, Kauzmann introduced the term "hydrophobic bond" to describe the attractive interactions between nonpolar groups in aqueous solutions [2]. Kauzmann's profound insight was recognizing that the same principles governing the association of simple nonpolar molecules in water could explain the folding and stability of complex protein structures. His hypothesis proposed that dehydration of nonpolar amino acid side chains, followed by their association in the protein interior, was energetically favorable and represented a dominant factor in thermodynamic protein stability [3].

Thermodynamic Basis and Experimental Evidence

Kauzmann's hypothesis was primarily based on free energy transfer measurements of nonpolar hydrocarbons from water into organic solvents [3]. The negative free energy values observed in these transfer experiments were interpreted as mimicking the energetic changes occurring when nonpolar groups buried in the protein interior during folding. Kauzmann emphasized the entropic contribution to this process, relating it to the structural changes in water molecules surrounding nonpolar surfaces [3]. This "classical" view of hydrophobic interactions as entropy-driven became widely accepted and was incorporated into biochemistry textbooks for decades.

The work of Némethy, Scheraga, and Steinberg further supported and refined Kauzmann's concepts by investigating the temperature dependence of hydrophobic interactions [2]. Their research demonstrated that hydrophobic "bonds" were endothermic - strengthening with increasing temperature up to approximately 60°C - in contrast to hydrogen bonds which weaken with rising temperature [2]. This differential temperature dependence suggested a delicate balance of forces in protein stability, with hydrophobic interactions dominating at higher temperatures while hydrogen bonds maintain structure at lower temperatures.

Table 2: Thermodynamic Characterization of Hydrophobic Interactions

| Property | Characteristic | Molecular Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Primarily entropic at room temperature | Release of structured water molecules into bulk |

| Temperature Dependence | Strength increases to ~60°C | Enhanced breakdown of water structure |

| Entropy Change | Positive (ΔS > 0) upon association | Increased freedom of released water molecules |

| Enthalpy Change | Variable, can be positive or negative | Balance between broken and formed water H-bonds |

Critical Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

The experimental foundation supporting Kauzmann's hydrophobic bond concept relied on several key methodological approaches:

Transfer Free Energy Measurements: This involved determining the free energy change for transferring hydrophobic solutes (such as methane or ethane) from water to a nonpolar solvent or to the pure liquid state. The measured values typically ranged between -8 and -12 kJ mol⁻¹ for hydrocarbons like cyclohexane, providing quantitative estimates of the hydrophobic effect [6] [3].

Protein Denaturation Studies: Researchers employed chemical denaturants (urea, guanidinium chloride) or temperature changes to unfold proteins while monitoring structural changes using techniques like circular dichroism, UV spectroscopy, or calorimetry. These studies revealed correlations between nonpolar surface area exposure and denaturation energetics.

Model Compound Studies: Investigations using small peptides or hydrophobic molecules like benzene derivatives measured association constants in aqueous solutions, demonstrating the tendency of nonpolar groups to cluster in water [6].

Evolution from 'Bond' to 'Effect': Semantic and Conceptual Refinement

Terminology Debate and Evolving Understanding

The term "hydrophobic bond" introduced by Kauzmann initially gained traction in the scientific literature, but eventually faced scrutiny as researchers recognized that the phenomenon differed fundamentally from covalent or ionic bonds [2]. The semantic debate centered on whether the association of nonpolar molecules in water resulted from direct attractive forces between the molecules or was instead an indirect effect driven by water reorganization. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, the term gradually shifted to "hydrophobic interaction" or "hydrophobic effect" to better reflect the underlying physical chemistry [2].

This conceptual evolution was significantly advanced by Robert Hermann's theoretical work in the 1970s, which provided a mathematical framework for understanding hydrophobic phenomena based on surface area and solubility relationships [2]. Hermann proposed that the free energy for hydration of a hydrophobic molecule was linearly related to the number of water molecules that could pack around it, establishing quantitative relationships between hydrophobic surface area and aqueous solubility [2].

Quantitative Frameworks and Hydrophobicity Scales

The development of quantitative hydrophobicity scales represented a critical advancement in applying hydrophobic effect principles to protein research. The introduction of the 1-octanol/water partition coefficient (LogP) as a standardized measure of hydrophobicity by Hansch and colleagues provided a universal parameter for predicting molecular behavior in biological systems [2]. This led to the creation of computational methods for estimating LogP values, including:

- Fragment-based methods (e.g., Rekker's method, C-LOGP)

- Atom-based methods (e.g., Ghose-Crippen method)

- Whole molecule approaches (e.g., Molecular Lipophilicity Potential)

These quantitative approaches enabled researchers to predict the hydrophobic character of amino acid side chains and their contribution to protein stability, folding, and molecular recognition events [7] [2].

Modern Computational and Theoretical Approaches

Contemporary Hydrophobicity Scales and Protein Structure Prediction

Modern research has refined our understanding of how hydrophobicity patterns in protein sequences influence tertiary structure. The burial mode model represents a recent phenomenological approach that predicts burial traces in protein domains based on sequence hydrophobicity [7]. This computationally efficient model (requiring less than one second for a 100-300 residue protein on a single CPU) incorporates hydrophobic effect, steric repulsion, and polymeric constraints as key folding drivers [7]. Parameter optimization studies have demonstrated that classic hydrophobicity scales like Kyte-Doolittle are nearly optimal for predicting residue burial using this model [7].

Challenging Classical Views: Emerging Perspectives

Recent research has begun to challenge Kauzmann's classical hydrophobic interaction hypothesis. A 2021 study by Yoshida and colleagues employed liquid-state density functional theory to calculate solvation free energies in protein folding thermodynamics [3]. Their analysis of the GCN4-p1 leucine zipper formation demonstrated that water-mediated interactions were actually unfavorable for the association of nonpolar groups in the native state, while dispersion forces between nonpolar groups were responsible for their association [3].

This direct interaction mechanism contradicts the long-standing view that avoiding exposure of nonpolar groups to water is the primary stabilizing factor in protein folding. Instead, it suggests that intramolecular direct interactions (van der Waals forces and hydrogen bonds) predominantly stabilize folded proteins, with water-mediated interactions often acting destabilizing [3]. This represents a potential paradigm shift in understanding protein folding energetics.

Diagram 2: Paradigm Shift in Understanding Protein Folding Drivers. The classical view emphasizes favorable water-mediated interactions, while emerging evidence points to direct dispersion forces as key stabilizers, with water-mediated interactions often being unfavorable.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methods

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for Studying Hydrophobic Interactions

| Reagent/Method | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1-Octanol/Water System | Standardized system for measuring partition coefficients (LogP) | Universal reference for hydrophobicity quantification |

| Kyte-Doolittle Scale | Hydrophobicity scale for predicting residue burial in proteins | Nearly optimal for burial prediction in phenomenological models |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Atomistic modeling of water behavior near hydrophobic surfaces | Reveals details of water structure and dynamics |

| Liquid-State Density Functional Theory | Ab initio calculation of solvation free energies | Challenges classical views on water-mediated interactions |

| Neutron Scattering | Experimental probe of water structure around solutes | Tests "iceberg" model predictions |

| Bulk Alkanes (methane, cyclohexane) | Model compounds for transfer free energy studies | Provide baseline hydrophobicity measurements |

The historical journey from Meyer and Overton's empirical observations to Kauzmann's conceptualization of the hydrophobic bond represents a foundational narrative in structural biology. This progression demonstrates how simple correlations between lipid solubility and biological activity evolved into a sophisticated understanding of the physical forces governing protein folding and stability. While Kauzmann's hydrophobic bond hypothesis dominated biochemical thinking for decades, recent computational and theoretical advances are challenging this classical view, suggesting a more complex interplay of direct intermolecular forces and water-mediated effects.

For contemporary researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this historical foundation and its ongoing evolution is crucial for interpreting protein behavior and designing molecular interventions. The hydrophobic effect remains a vital concept, but its precise role in protein folding continues to be refined through advanced computational methods and experimental techniques. As research progresses, the integration of these historical insights with emerging paradigms will undoubtedly lead to more accurate models of biomolecular structure and function.

The hydrophobic effect, a fundamental force in aqueous solutions, is primarily an entropic phenomenon driven by the unique properties of water. It describes the tendency of nonpolar substances to aggregate and minimize their contact with water, thereby maximizing the entropy of the surrounding water molecules. This effect is not merely a passive exclusion but an active process governed by the hydrogen-bonding network of water. Within the context of protein folding and biomolecular stability, the hydrophobic effect provides a major thermodynamic driving force for the burial of nonpolar residues, the formation of molten globule states, and the establishment of functional native structures. This whitepaper elucidates the physical chemistry of hydrophobicity, detailing its entropic origin, its dependence on solute size and temperature, and the experimental and computational methodologies employed to quantify its role in directing the folding and function of biological macromolecules.

Hydrophobic interactions are involved in and are believed to be the fundamental driving force of many chemical and biological phenomena in aqueous environments, including molecular recognition, protein folding, and the formation and stability of micelles and biological membranes [1]. The word "hydrophobic" literally means "water-fearing," and the effect describes the segregation of water and nonpolar substances, which maximizes the entropy of water and minimizes the area of contact between water and nonpolar molecules [8]. From a thermodynamic perspective, the hydrophobic effect is defined as the free energy change of water surrounding a solute. A positive free energy change indicates hydrophobicity, whereas a negative free energy change implies hydrophilicity [8].

In biochemistry, the hydrophobic effect is essential to life. It is responsible for the formation of cell membranes and vesicles, the folding of proteins into their native functional three-dimensional structures, the insertion of membrane proteins into lipid bilayers, and the associations between proteins and small molecules [8] [9]. A complete understanding of this effect requires a description of the conformational states of both water and solute molecules across different temperatures, revealing the delicate balance between enthalpy and entropy that dictates solvation behavior [9].

Theoretical Framework: Thermodynamics and Solvation

The Entropic Origin

The classical understanding of the hydrophobic effect is that it is entropy-driven at room temperature. When a nonpolar solute is introduced into water, the water molecules in its immediate vicinity form a structured "cage" or clathrate. The formation of this cage results in a significant loss of translational and rotational entropy for the involved water molecules [8]. The hydrogen bonds between water molecules are reoriented tangentially to the nonpolar surface to minimize the disruption of the bulk hydrogen-bonded network. This structuring leads to a more ordered system and a corresponding decrease in entropy [8] [1].

The aggregation of nonpolar molecules reduces the total surface area exposed to water. This process releases the structured water molecules from the cages back into the bulk solvent, where they experience greater rotational and translational freedom. This release results in a large, favorable increase in the entropy of the system, which is the primary driving force for the hydrophobic effect under standard conditions [8] [1]. The process can be summarized by the fundamental equation of thermodynamics:

ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

Where a positive ΔG indicates hydrophobicity. For the hydrophobic effect, the entropic term (-TΔS) is dominant and favorable for aggregation at room temperature [8] [1].

The Role of Enthalpy and Temperature Dependence

While entropy is the dominant driver at room temperature, the enthalpic component (ΔH) of the hydrophobic effect is also significant and can become dominant under certain conditions. Experimental studies have found that the enthalpic component of transfer energy is favorable, meaning it strengthens water-water hydrogen bonds in the solvation shell [8]. This finding appears counterintuitive but aligns with the observation that hydrophobic interactions can be enthalpy-driven in some binding systems [1] [8].

The hydrophobic effect exhibits a strong temperature dependence. At higher temperatures, when water molecules become more mobile, the energy gain from strengthened hydrogen bonds in the solvation shell decreases along with the entropic component [8]. This temperature dependence is directly responsible for the phenomenon of "cold denaturation" of proteins, where proteins unfold at low temperatures [8] [9]. At lower temperatures, the enthalpic contribution becomes more favorable, stabilizing the unfolded state where more water molecules can interact with the protein backbone and side chains.

The Size Crossover: Small vs. Large Solutes

A critical concept in hydrophobicity is the dependence on solute size. Theoretical and experimental work has revealed a crossover around the 1 nm length scale [1] [9].

- Small Solutes (< 1 nm): For small nonpolar solutes, water molecules can rearrange around the solute without a significant net loss of hydrogen bonds. The hydration free energy scales linearly with the volume of the solute. The water network remains largely intact, forming "iceberg"-like structures around the solute [1].

- Large Solutes (> 1 nm): For large hydrophobic surfaces, water cannot maintain its hydrogen-bonding network at the interface. Hydrogen bonds are broken, resulting in an enthalpic penalty. In this regime, the hydration free energy scales linearly with the surface area of the solute [1] [9].

Proteins present a complex case because their surfaces are mosaics of polar and non-polar residues. Even though proteins are larger than 1 nm, the presence of polar groups allows water at the protein interface to, on average, form the same total number of hydrogen bonds (protein-water + water-water) as bulk water, causing them to effectively behave like small solutes in this respect [9].

Table 1: Thermodynamic Characteristics of Hydrophobic Hydration

| Feature | Small Solutes (<1 nm) | Large Solutes (>1 nm) |

|---|---|---|

| Scaling of Hydration Free Energy | Linear with solute volume | Linear with solute surface area |

| Hydrogen Bonding at Interface | Largely maintained; water can rearrange without breaking H-bonds | Disrupted; H-bonds are broken, leading to an enthalpic penalty |

| Water Ordering | Increased order ("iceberg" model) | Depends on surface chemistry; can be less ordered |

| Dominant Thermodynamic Driver | Entropy (TΔS) | Enthalpy (ΔH) can become significant |

Hydrophobicity in Protein Folding and Stability

A Major Driving Force for Folding

The hydrophobic effect is the principal driving force behind the folding of globular proteins. The process of folding minimizes the number of hydrophobic side chains exposed to water, which stabilizes the folded state [8]. In the native state, proteins typically possess a hydrophobic core in which nonpolar side chains (e.g., valine, leucine, isoleucine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, and methionine) are buried, shielded from the aqueous solvent. Charged and polar side chains are predominantly situated on the solvent-exposed surface, where they can interact with surrounding water molecules [8].

The drive to sequester hydrophobic residues away from water creates a compact, molten globule-like state early in the folding pathway. Subsequent fine-tuning of the structure, including the formation of specific hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts within the core, then optimizes the stability of the native fold [8] [8]. While hydrogen bonds within the protein are crucial for stability and specificity, the initial collapse is governed by the hydrophobic effect [8].

Structural Biology: Hot vs. Cold Denaturation

The temperature dependence of the hydrophobic effect provides a unique window into its mechanism, exemplified by the study of hot and cold denatured states. Research on yeast frataxin, a protein for which both states have been characterized, reveals structural differences that underscore the role of water [9].

- Hot Denatured State (HDS): At high temperatures, the denatured state is more compact and richer in secondary structure (e.g., α-helix content of 10%) than the cold denatured state. The radius of gyration (Rg) is smaller.

- Cold Denatured State (CDS): At low temperatures, the denatured state is more expanded, has less secondary structure (α-helix content of 6%), and has a higher polyproline II content. Its radius of gyration is larger [9].

These differences are linked to the behavior of water. The number of hydrogen bonds per water molecule in the bulk decreases with increasing temperature. Remarkably, the total number of hydrogen bonds per water molecule (water-water + protein-water) is nearly identical for bulk water and water at the protein interface across temperatures. In the cold denatured state, the protein expands to allow water to form more hydrogen bonds with it, stabilizing the expanded state through enthalpic gains. This finding indicates that proteins, due to their heterogeneous surface, can behave like "small" solutes, with water maintaining its hydrogen-bonding capacity at the interface [9].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationships and experimental observations that link the hydrophobic effect to protein denaturation states.

Beyond Thermodynamic Stability: Mechanical Stability

While the hydrophobic effect is a major contributor to the thermodynamic stability of the folded state, its role in mechanical stability—a protein's resistance to being unfolded by force—is different. Steered molecular dynamics simulations have shown that the contribution of hydrophobic interactions to the total resistive force during mechanical unfolding varies between one-fifth and one-third. The rest of the force is attributed primarily to hydrogen bonds [10]. This contrasts with their dominant role in thermodynamic stability and is explained by the steeper free energy dependence of hydrogen bonds on the relative positions of interacting atoms compared to the shallower dependence of hydrophobic interactions [10].

Quantitative Measurement and Prediction

Experimental Methodologies

A range of experimental techniques is used to quantify hydrophobicity and its effects on proteins and other molecules.

- Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC): This is a standard method for separating proteins based on hydrophobicity. Proteins with higher surface hydrophobicity interact more strongly with the hydrophobic stationary phase and have longer retention times. HIC is widely used to assess the hydrophobicity of therapeutic antibodies [11].

- Partition Coefficients (log P): The logarithm of the partition coefficient of a solute between a nonpolar solvent (like n-octanol) and water is a fundamental measure of hydrophobicity. It is empirically calculated and widely used in drug design and medicinal chemistry [1] [12].

- Nile Red Staining: This fluorescence-based assay is used to quantify the hydrophobicity of materials, including polymers. The dye's emission spectrum shifts based on the hydrophobicity of its local environment [12].

- Calorimetry: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) are used to directly measure the enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (TΔS) components of hydrophobic interactions and protein stability [8].

- Spectroscopic Techniques: NMR and vibrational spectroscopy (e.g., Raman, IR) are used to probe the structure and dynamics of water molecules at the interfaces of solutes and proteins [1] [9].

Table 2: Key Experimental Protocols for Assessing Hydrophobicity

| Method | Key Measurement | Application in Research | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) | Protein retention time on a hydrophobic column. | Ranking hydrophobicity of protein mutants (e.g., therapeutic antibodies); protein purification [11]. | Salt concentration modulates effect; requires protein in solution. |

| Partition Coefficient (log P) | Equilibrium concentration ratio in octanol/water. | Quantifying hydrophobicity of small molecules and drug candidates; QSAR modeling [1] [12]. | Gold standard for small molecules; less applicable to large polymers/proteins. |

| Nile Red Staining | Shift in fluorescence emission maximum. | High-throughput screening of polymer hydrophobicity; material science [12]. | Semi-quantitative; requires a calibration curve for different material classes. |

| Calorimetry (ITC/DSC) | Direct measurement of heat change (ΔH). | Decomposing free energy into enthalpic and entropic components of binding or unfolding [8]. | Requires significant sample amounts; instrument sensitivity is critical. |

| Spectroscopy (NMR) | Chemical shifts and relaxation rates of water/protons. | Probing water structure and dynamics at protein interfaces; characterizing denatured states [9]. | Can be technically challenging; provides atomic-level detail. |

Computational and In-Silico Approaches

Computational methods are indispensable for predicting hydrophobicity and understanding its molecular origins.

- Hydrophobicity Scales: These are tables that assign a numerical hydrophobicity value to each amino acid based on experimental data or theoretical calculations. Examples include the Kyte-Doolittle scale, which colors residues from hydrophobic (red, e.g., I, V, L, F) to hydrophilic (blue, e.g., R, K, N) [13]. The performance of these scales in predicting experimental results like HIC retention times varies significantly [11].

- Structure-Based Methods: These methods use the three-dimensional structure of a protein to compute hydrophobicity, often providing more accuracy than sequence-based methods.

- Spatial Aggregation Propensity (SAP): Computes the sum of hydrophobicity values of surface-exposed atoms within a defined radius, identifying hydrophobic patches [11].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: All-atom, explicit-solvent simulations can model the water structure around solutes and proteins, providing deep insight into the hydrophobic effect but at high computational cost [11] [9].

- Quantum Chemical Calculations: These methods compute solvation energies and Abraham parameters from first principles, allowing for the prediction of hydrophobicity (e.g., log P) directly from molecular structure without experimental input [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Hydrophobicity Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Phenyl-Sepharose / Butyl-Sepharose | Hydrophobic stationary phase for HIC. | Separating protein mixtures based on hydrophobicity; higher salt concentrations enhance binding [8] [11]. |

| Ammonium Sulfate / Sodium Chloride | Salts for modulating ionic strength. | Used in HIC buffers to increase the hydrophobic effect (salting-out), promoting binding of proteins to the HIC resin [8] [9]. |

| n-Octanol and Water Partition System | Two-phase solvent system for measuring log P. | Experimental determination of the hydrophobicity of small molecules and drug-like compounds [1] [12]. |

| Nile Red Dye | Environment-sensitive fluorescent probe. | Staining and quantifying the hydrophobicity of polymeric materials or aggregated proteins [12]. |

| Thermostable Proteins (e.g., Yeast Frataxin) | Model systems for studying folding. | Investigating structural details of hot and cold denatured states via NMR and other biophysical techniques [9]. |

| Deuterated Solvents (D₂O) | NMR-active solvent for structural biology. | Probing the dynamics and structure of water molecules at protein interfaces and in bulk solution [9]. |

The hydrophobic effect is a quintessential entropic phenomenon, mediated by the unique and dynamic hydrogen-bonding network of water. Its influence extends from the fundamental driving forces that dictate protein folding and assembly to critical applications in drug development and material science. While the classical view emphasizes its entropic nature, modern research reveals a more nuanced picture, incorporating significant enthalpic contributions, a strong dependence on length scale and temperature, and complex behaviors at biological interfaces. Continued advances in experimental structural biology, such as the characterization of denatured states, and in computational modeling, from molecular dynamics to quantum chemistry, are refining our understanding. This deeper insight is crucial for rationally designing stable biopharmaceuticals, predicting molecular behavior in complex environments, and fundamentally understanding the aqueous foundation of life itself.

The classical "oil drop" model of protein folding, which conceptualizes the protein core as a uniform hydrophobic sphere, has long provided a foundational understanding of protein stability. However, contemporary research reveals that protein cores are far from homogeneous; they are complex, chemically heterogeneous environments whose specific composition dictates folding pathways, final three-dimensional structure, and biological function. This paradigm shift is critical for advancing research in protein folding and the hydrophobic effect, as it moves beyond the notion of hydrophobicity as a singular driving force and toward an integrated view where the precise arrangement of hydrophobic, polar, and aromatic residues determines structural stability and specificity. The fuzzy oil drop (FOD) model represents a significant evolution of this concept, describing the hydrophobic core not as a perfect sphere but as a 3D Gaussian distribution of hydrophobicity, which can be actively influenced by the aqueous environment [14]. This guide synthesizes current evidence demonstrating that the core's heterogeneous chemistry, underpinned by synergistic interactions, is a fundamental principle governing protein behavior, with profound implications for understanding diseases like amyloidosis and for structure-based drug design [14] [15].

Theoretical Frameworks: Modeling the Heterogeneous Core

The Fuzzy Oil Drop (FOD) Model

The FOD model refines the traditional oil drop concept by quantifying the theoretical ideal hydrophobic density within a protein as a three-dimensional Gaussian distribution, centered on the molecule's geometric center. The model then compares this ideal "hydrophobic field" to the observed, empirical distribution of hydrophobicity derived from the protein's atomic structure [14] [15]. The degree of agreement between the theoretical and observed distributions serves as a quantitative measure of how "ideal" a hydrophobic core a protein possesses.

This framework is particularly powerful for analyzing proteins that deviate from the simple model. For instance, it has been used to explain the amyloidogenic potential of proteins like transthyretin. The model reveals a clear relationship between amyloidogenic properties and structural characteristics where the empirical hydrophobic distribution diverges from the theoretical Gaussian, predisposing the protein to form the alternative, band-micelle structures found in amyloid fibrils instead of the soluble, spherical-micelle-like core [14].

Synergy and the Metamorphic Protein Paradigm

The concept of synergy is central to understanding heterogeneous cores. It posits that the protein's final tertiary structure and core structure are an emergent property of the entire polypeptide chain working in concert, rather than just the sum of local interactions [15]. This explains the phenomenon of metamorphic proteins and chameleon sequences, where identical short amino acid sequences can adopt different secondary structures (α-helical in one protein, β-sheet in another) depending on the context of the entire chain [15].

Striking evidence comes from de novo designed proteins. As shown in Table 1, a single point mutation (e.g., L45Y) in a 56-amino-acid chain can trigger a complete structural metamorphosis from a 3α helical fold to a 4β + α fold [15]. This dramatic shift, driven by a minimal sequence change, underscores that the hydrophobic core is not a passive container but a dynamically determined system. The folding pathway and final architecture are a synergistic outcome, where a single mutation can alter the collective interactions of all residues, leading to the construction of a completely different hydrophobic core [15].

Table 1: Impact of Single Mutations on Protein Core Structure and Global Fold in De Novo Proteins

| Protein Name | PDB ID | Mutation(s) | Chain Length | Resulting Structural Form | Core Implication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ga98 | 2LHC | None | 56 aa | 3α | Reference hydrophobic core |

| Gb98 | 2LHD | L45Y | 56 aa | 4β + α | Single mutation triggers alternative core and fold |

| Gb98-T25I | 2LHG | L45Y, T25I | 56 aa | 3α | Compensatory mutation restores original core/fold |

| Gb98-T25I,L20A | 2LHE | L45Y, T25I, L20A | 56 aa | 4β + α | Additional mutation again switches core/fold |

Relative Contribution of Hydrophobic vs. Polar Interactions

The heterogeneity of the core also relates to the balance of different interaction types. While hydrophobic interactions are a primary contributor to thermodynamic stability, their role in mechanical stability is different. Steered molecular dynamics simulations reveal that when a protein is mechanically unfolded, the contribution of hydrophobic interactions to the resistance force is modest (one fifth to one third of the total force), while hydrogen bonds provide the majority of the mechanical resistance [10]. This contrast highlights a critical functional differentiation: the heterogeneous core is optimized not just for thermodynamic stability in the native state, but also for specific mechanical properties, with hydrogen bonds playing a disproportionately important role in resisting mechanical deformation [10].

Experimental Methodologies and Quantitative Analysis

Protocol: Quantifying Core Hydrophobicity with the FOD Model

The following is a detailed methodology for applying the FOD model to analyze a protein structure, as used in recent studies [14] [15].

- Data Acquisition: Obtain the three-dimensional atomic coordinates of the protein of interest from the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

- Theoretical Hydrophobicity Density (T) Calculation:

- Model the protein as a collection of atoms occupying discrete points in space.

- Define a theoretical hydrophobic density field, (\rhot(x, y, z)), using a 3D Gaussian function centered on the protein's geometric center: (\rhot(x, y, z) = \exp\left(-\frac{(x-x0)^2}{2\sigmax^2} - \frac{(y-y0)^2}{2\sigmay^2} - \frac{(z-z0)^2}{2\sigmaz^2}\right)) where (x0, y0, z0) are the coordinates of the center, and (\sigma) values define the spread of the distribution along each axis.

- Normalize the (\rhot) values so that the total sum of theoretical density across the entire protein volume equals 1.

- Empirical Hydrophobicity Density (O) Calculation:

- Assign an intrinsic hydrophobicity value to each amino acid residue in the chain (e.g., from a standardized scale like the Kyte-Doolittle scale).

- Smear this hydrophobicity value over the space occupied by the residue, typically using a Gaussian function centered on the residue's representative atom (e.g., Cα). This generates an empirical density field, (\rhoo(x, y, z)).

- Normalize the (\rhoo) values so that its total sum also equals 1.

- Divergence Calculation:

- Quantify the discrepancy between the theoretical (T) and observed (O) distributions using the Kullback-Leibler divergence: (D{KL}(O||T) = \sumi Oi \log\left(\frac{Oi}{Ti}\right)) where the sum is over all individual grid points (i) in the volume.

- A lower (D{KL}) value indicates a hydrophobic core that is closer to the idealized Gaussian model, while a higher value signifies greater disorder or heterogeneity.

- Analysis: Interpret the results in a biological context. A high divergence value may indicate a protein with a heterogeneous core, potentially prone to conformational changes, ligand binding, or aggregation, as seen in amyloidogenic proteins [14].

Protocol: Simulating Mechanical Unfolding via Steered Molecular Dynamics

This protocol is used to deconstruct the contribution of different interactions within the core to mechanical stability [10].

- System Preparation:

- Obtain the protein's PDB structure. Place it in a simulation box filled with explicit water molecules (e.g., TIP3P model).

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge and achieve a physiologically relevant ionic concentration.

- Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Perform energy minimization (e.g., using steepest descent algorithm) to remove any steric clashes.

- Run an equilibration molecular dynamics (MD) simulation under NVT (constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature) and NPT (constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature) ensembles for hundreds of picoseconds to stabilize the system.

- Steered MD (SMD) Simulation:

- Select two atoms (e.g., the N-terminus and C-terminus) as pulling points.

- Apply a constant velocity pulling force to one atom while restraining the other, effectively stretching the protein. Alternatively, use a constant force protocol.

- Run the SMD simulation for several nanoseconds, recording the positions of all atoms over time.

- Force-Extraction Curve and Interaction Analysis:

- Plot the force exerted on the pulling atom against the extension of the protein to generate a force-extension curve.

- Monitor the rupture events of specific interactions (hydrogen bonds and hydrophobic contacts) by tracking distances between key atoms over time.

- Correlate peaks in the force-extension curve with the simultaneous unraveling of specific interaction types to attribute force contributions.

- Quantification: Calculate the relative contribution of hydrophobic interactions by integrating the force peaks attributed to hydrophobic surface unraveling and comparing it to the total integrated force. Studies using this method have found the hydrophobic contribution to be between 20% and 33% of the total force, with hydrogen bonds being the dominant contributor to mechanical resistance [10].

Quantitative Benchmarks from Structural Bioinformatics

Large-scale comparative analyses, such as those evaluating AlphaFold2 (AF2) predictions against experimental structures, provide indirect but powerful insights into core heterogeneity. AF2 achieves high accuracy in predicting stable, ground-state conformations with proper stereochemistry. However, it shows systematic limitations in capturing the full spectrum of biologically relevant states, particularly in flexible regions and ligand-binding pockets [16].

Table 2: AlphaFold2 Performance Metrics Revealing Limitations in Modeling Heterogeneous Cores

| Analysis Parameter | Finding | Implication for Protein Cores |

|---|---|---|

| Domain Variability | Ligand-binding domains (LBDs) show higher structural variability (CV=29.3%) than DNA-binding domains (CV=17.7%) [16]. | Cores in LBDs are more flexible and context-dependent, defying a single, static oil-drop model. |

| Ligand-Binding Pockets | AF2 systematically underestimates ligand-binding pocket volumes by 8.4% on average [16]. | The precise chemistry and packing of core residues around ligands are difficult to predict from sequence alone, highlighting subtle heterogeneity. |

| Conformational States | AF2 captures only single conformational states in homodimeric receptors where experimental structures show functionally important asymmetry [16]. | Protein cores can adopt different, functionally relevant conformations in identical subunits, a level of heterogeneity not captured by static models. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Protein Folding Model Evolution

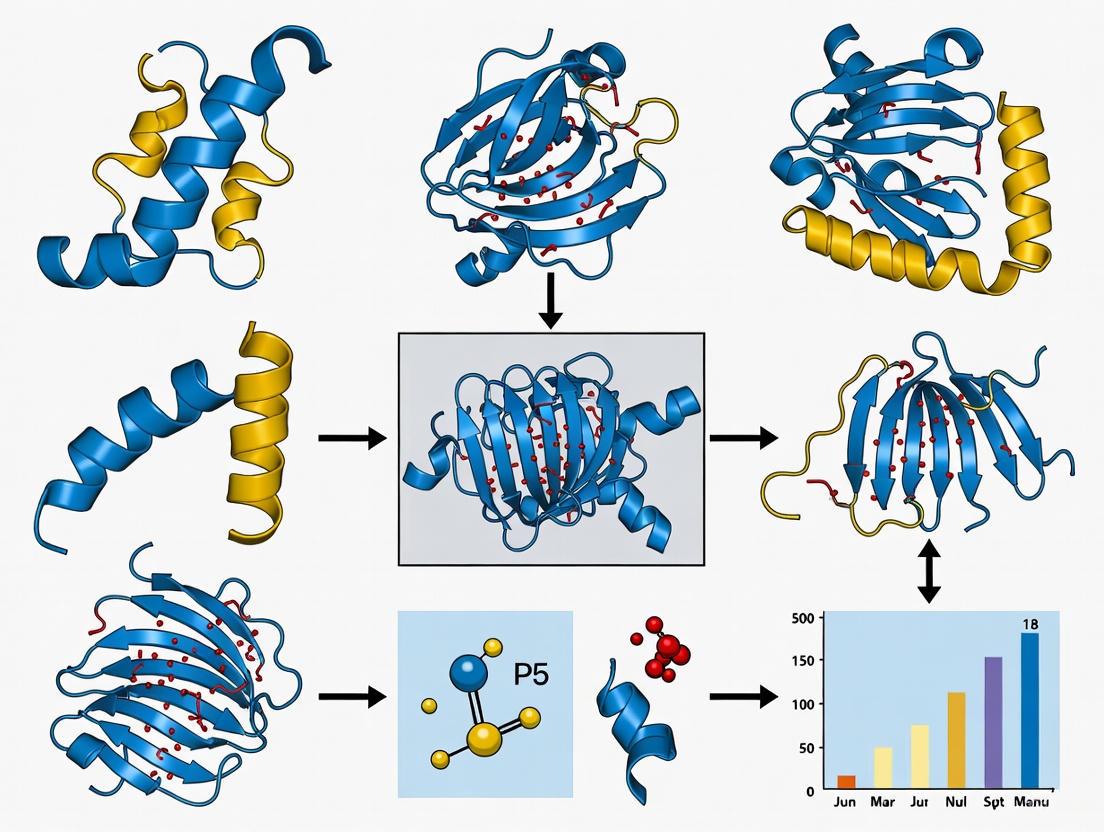

This diagram illustrates the conceptual evolution from the classical oil drop model to the modern fuzzy oil drop and heterogeneous core models.

Hydrophobic Core Analysis Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps for the computational analysis of a protein's hydrophobic core using the FOD model.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Studying Protein Cores

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D protein structures used for analysis and validation. | As of Jan 2025, contains >230,000 structures [16]. Essential for FOD model input. |

| De Novo Designed Proteins | Model systems with minimal sequence differences to study the direct impact of mutations on core formation and fold. | Proteins like Ga98/Gb98 (PDB: 2LHC, 2LHD) reveal metamorphosis via single mutations [15]. |

| AlphaFold2 Database | Source of AI-predicted protein structures for proteins lacking experimental data; benchmark for core variability. | Useful but may underestimate pocket volumes and miss conformational diversity in cores [16]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates protein dynamics and forced unfolding to quantify interaction contributions (e.g., GROMACS, NAMD). | Used in steered MD to show hydrophobic forces contribute 20-33% of mechanical resistance [10]. |

| Hydrophobicity Scales | Standardized values assigning hydrophobicity to each amino acid for empirical density calculation. | e.g., Kyte-Doolittle scale, used in step 3 of the FOD protocol [14] [15]. |

The evidence is clear: the classical oil drop model, while historically valuable, is insufficient to describe the sophisticated reality of protein cores. The core is a heterogeneous, chemically diverse environment whose structure emerges from the synergistic collaboration of the entire polypeptide chain, sensitive to minimal sequence changes and yielding diverse mechanical and thermodynamic properties. The adoption of the fuzzy oil drop model and the study of metamorphic proteins provide the conceptual and quantitative frameworks to understand this heterogeneity. Furthermore, the limitations of powerful AI prediction tools like AlphaFold2 in capturing the full conformational spectrum of binding pockets and flexible domains serve as a critical reminder that the heterogeneous chemistry of the core is a central challenge in computational structural biology [16]. For researchers and drug development professionals, embracing this complexity is paramount. It opens new avenues for structure-based drug design by targeting specific, alternative core conformations, and for understanding the fundamental mechanisms of protein misfolding diseases, where the failure to form a correct, heterogeneous core leads to pathological aggregation.

The role of water in biological processes extends far beyond that of a passive solvent. In phenomena ranging from protein folding to molecular recognition, water acts as an active participant whose properties and behaviors fundamentally dictate thermodynamic outcomes. The theoretical construct known as the hydrophobic effect provides the primary framework for rationalizing how water molecules stabilize the folded state of proteins and facilitate other essential biological processes [17]. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms through which water influences biomolecular folding and stability, with a specific focus on three interconnected concepts: the historical clathrate cage model, the modern understanding of solvent entropy, and the statistical mechanical perspective of cavity creation.

The classic explanation, heavily influenced by Kauzmann's 1959 review, posited that nonpolar side chains cluster together to form a nonpolar core, resembling an organic liquid—the so-called "oil drop model" of protein folding [17]. This view attributed the driving force for hydrophobic association to the entropy gain resulting from the release of ordered water molecules that formed structured "icebergs" or clathrate-like cages around nonpolar solutes. However, advancing research in statistical mechanics and computational modeling has challenged aspects of this traditional view, leading to a more nuanced understanding of how water actively participates in and drives biomolecular organization.

Theoretical Frameworks: From Clathrate Cages to Cavity Creation

The Traditional Clathrate Cage Model

The classic Kauzmann explanation of the hydrophobic effect emerged from observations that the Gibbs free energy change of transfer for hydrocarbon species from organic liquids to water is largely positive and entropy-dominated [17]. This entropy dominance was historically attributed to water's purported ability to form ordered three-dimensional structures—often described as "icebergs" or clathrate cages—around nonpolar species that cannot participate in hydrogen bonding with the solvent network. According to this model, when nonpolar groups associate in water, these structured water molecules are released back into the bulk solvent, gaining translational entropy and thereby providing the thermodynamic driving force for hydrophobic interactions.

However, this traditional view faces several theoretical and experimental challenges. The existence of such extensively ordered structures around nonpolar solutes has never been conclusively demonstrated in liquid water at physiological temperatures [17]. The clathrate cage model represents an appealing but potentially oversimplified conceptualization of what occurs at the molecular level when water interacts with nonpolar surfaces.

Modern Statistical Mechanical Perspective

Contemporary statistical mechanical analysis provides an alternative framework for understanding hydrophobic hydration. According to this perspective, the key concept is cavity creation—the theoretical process of creating a void space in water at a fixed position to host a solute molecule [17]. This construct accounts for the fundamental physical fact that all molecules possess volume and cannot occupy the same space simultaneously.

The process of cavity creation in water carries a significant Gibbs free energy cost (ΔGc) that increases with the liquid's number density [17]. Water, with its exceptionally high number density due to small molecular size, therefore imposes a substantial thermodynamic penalty for cavity creation. The presence of a cavity generates a solvent-excluded volume effect that affects all surrounding water molecules as they undergo continuous translational motion. This exclusion effect reduces the translational entropy of water molecules by restricting their accessible configurational space—a phenomenon particularly pronounced in water due to its high number density.

Table 1: Comparison of Historical and Modern Views of the Hydrophobic Effect

| Aspect | Traditional View (Clathrate Cages) | Modern View (Cavity Creation) |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Release of structured water molecules | Gain in translational entropy of water |

| Molecular Origin | Hydrogen bond reorganization | Excluded volume effects |

| Water Structure | Iceberg-like clusters around nonpolar groups | Liquid water with restricted configurations |

| Entropy Dominance | Due to melting of ordered structures | Due to increased translational freedom |

| Theoretical Basis | Analogous to clathrate compounds | Statistical mechanics of dense liquids |

When a protein folds, the reduction in water-accessible surface area (WASA) reduces the total excluded volume effect, allowing more configurational space for water molecules and thereby increasing their translational entropy [17]. This entropy gain represents the fundamental driving force behind protein folding from the solvent's perspective. The modern view thus maintains that "the gain in translational entropy of water molecules (due to the decrease in water-accessible surface area associated with folding) is the driving force behind protein folding" [17], but through the mechanism of reduced excluded volume rather than the breakdown of clathrate-like structures.

Computational Methodologies for Investigating Hydration

Molecular Dynamics Simulations

Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations have become indispensable tools for studying the behavior of water in biological systems at atomic resolution. MD is a computational technique that evaluates a molecular system's thermodynamic properties and conformational behavior over time by numerically solving Newton's equations of motion for all atoms in the system [18] [19]. In the context of protein folding and hydration, MD simulations typically employ an atomistic "all-atom" approach where the model system consists of a collection of interacting particles represented as atoms, describing both the solute biomolecule and the surrounding solvent water molecules [19].

Modern MD simulations of biomolecular systems are generally performed using the following protocol [18] [20]:

- System Preparation: The protein structure from experimental data is solvated in a water box, with ions added to achieve physiological concentration and neutrality.

- Force Field Selection: Empirical potential energy functions are applied to describe atomic interactions.

- Energy Minimization: The system is relaxed to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: The system is gradually brought to the target temperature and pressure.

- Production Run: The final trajectory is generated for analysis.

For proteins, simulations are typically conducted in the isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensemble using software packages such as GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD [19] [20]. The GROMOS 54a7 force field is commonly employed for modeling biomolecules, with water represented by models such as TIP3P, TIP4P, or SPC [20]. Simulation boxes are typically cubic with periodic boundary conditions applied to minimize edge effects, with system sizes ranging from tens of thousands to millions of atoms depending on the biological question [19].

Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory

Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory provides a powerful methodological framework for analyzing water structure and thermodynamics from MD trajectories. GIST discretizes the analytical expressions of inhomogeneous solvation theory onto a spatial grid, allowing calculation of thermodynamic quantities at each voxel throughout the system [21].

The key equations underlying GIST analysis are:

The solvation free energy: ΔGₛₒₗᵥ = ΔEₛₒₗᵥ - TΔSₛₒₗᵥ [21]

The solvation enthalpy: ΔEₛₒₗᵥ = ΔEₛᵥ + ΔEᵥᵥ [21]

The solvation entropy: ΔSₛₒₗᵥ = ΔSₜᵣₐₙₛ + ΔSₒᵣᵢₑₙₜ [21]

Where ΔEₛᵥ represents solute-water interactions, ΔEᵥᵥ represents water-water interactions, ΔSₜᵣₐₙₛ represents translational entropy, and ΔSₒᵣᵢₑₙₜ represents orientational entropy. This decomposition enables researchers to separately quantify the enthalpic and entropic contributions to hydrophobicity, providing unprecedented insight into the molecular origins of hydrophobic effects [21].

Table 2: Key Properties Calculated from MD Simulations for Hydration Analysis

| Property | Symbol | Description | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solvation Free Energy | ΔGₛₒₗᵥ | Free energy change for transferring solute from gas to water | Measures overall hydrophobicity |

| Solvent Accessible Surface Area | SASA | Surface area accessible to water molecules | Correlates with hydrophobic effect strength |

| Coulombic Energy | - | Electrostatic solute-solvent interactions | Measures polar contributions to solvation |

| Lennard-Jones Energy | LJ | van der Waals solute-solvent interactions | Measures nonpolar contributions |

| Translational Entropy | ΔSₜᵣₐₙₛ | Entropy from water position distribution | Key driver of hydrophobic effect |

| Orientational Entropy | ΔSₒᵣᵢₑₙₜ | Entropy from water orientation distribution | Measures ordering of water molecules |

Experimental Evidence and Case Studies

Water in Protein Folding and Stability

The role of water as an active participant in protein folding finds support in computational studies of specific protein systems. Research on the Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor γ provides a compelling case study. PPARγ is a nuclear receptor with a large, flexible active site characterized by a distinctive ω-loop that confers exceptional flexibility [18]. MD simulations of PPARγ complexed with Rosiglitazone (an anti-diabetic drug) revealed significant flexibility in the ω-loop region, with root mean square fluctuation values between 4-6 Å [18].

When Oleic Acid was introduced as a co-ligand binding to an alternate site, it produced a notable stabilization of the ω-loop, reducing RMSF values to 2-3 Å [18]. This stabilization occurred through allosteric modulation mediated by changes in the hydration environment. HINT-based analysis of the MD trajectories demonstrated that the binding event altered the intramolecular interactions between the flexible ω-loop and helix H3, with water molecules playing a crucial role in transmitting these allosteric effects [18].

Cavitation in Protein-Protein Interactions

Cavitation—the formation of vapor-filled cavities in liquids when pressure falls below the vapor pressure—represents an extreme manifestation of hydrophobic effects with significant implications for protein interactions [22]. In fluid mechanics and engineering, cavitation occurs when the static pressure of a liquid reduces to below the liquid's vapor pressure, leading to the formation of small vapor-filled cavities that collapse violently when subjected to higher pressure, generating shock waves [22].

In biological systems, cavitation phenomena can occur between hydrophobic protein surfaces. Studies of the melittin dimer system have provided direct observation of solvent-mediated hydrophobic protein-protein interactions [23]. When two melittin dimers associate through their hydrophobic contact regions, cavitation can occur between these surfaces. This cavitation was observed even with native electrostatic interactions intact [23]. Subsequent mutations that altered the geometry of the tetramer interface eliminated cavitation, demonstrating the exquisite sensitivity of this phenomenon to surface topography and chemical heterogeneity.

The process of cavitation between hydrophobic surfaces follows a predictable pattern: "When one turns to the molecular details of the mechanism of nonpolar aggregation in water, the picture is still not completely clear. The two limiting scenarios for events such as protein folding and directed self-assembly are [...] In the traditional view, water is gradually reduced within and between the associating regions in a manner that is concerted with their spatial approach. In an alternative cavitation scenario, a thermodynamic instability leads to water evacuation from the intervening space between hydrophobic regions, and the 'hydrophobic collapse' to contact then follows; the processes are sequential." [23]

Hydrophobicity Scales and Their Limitations

Traditional hydrophobicity scales assign a value to each amino acid describing its relative hydrophobic character. While useful for predicting protein secondary structures, membrane regions, and interior-exterior distributions, these scales have significant limitations [21]. They represent averaged hydrophobic character over entire amino acids, lacking spatial resolution to identify heterogeneous regions within binding pockets. Furthermore, conventional scales cannot directly measure entropic contributions to hydration, instead estimating them indirectly from temperature dependence of free energy or as the difference between free energy and enthalpy [21].

Advanced computational approaches now enable more sophisticated characterization of hydrophobicity. Methods combining MD simulations with GIST analysis can directly calculate entropic contributions from the phase space occupied by water molecules, providing both spatial resolution and separation of enthalpic and entropic components [21]. This represents a significant advancement over traditional hydrophobicity scales and offers new insights into the true nature of hydrophobic hydration.

Practical Implications in Drug Discovery and Development

Solubility Prediction and Optimization

Understanding water-solute interactions has direct applications in predicting and optimizing drug solubility—a critical factor in pharmaceutical development. Machine learning analysis of MD-derived properties has identified key descriptors correlating with aqueous solubility, including logP (octanol-water partition coefficient), SASA, Coulombic interactions, Lennard-Jones interactions, estimated solvation free energies, and structural fluctuation parameters [20].

These MD-derived properties demonstrate comparable predictive power for solubility to traditional structural descriptors, with gradient boosting algorithms achieving a predictive R² of 0.87 and RMSE of 0.537 [20]. This integration of MD simulations with machine learning represents a powerful approach for prioritizing compounds with optimal solubility profiles early in drug discovery, potentially reducing resource consumption and improving clinical success rates.

Protein Aggregation in Biopharmaceuticals

The role of water in protein stability has crucial implications for biopharmaceutical development, particularly regarding protein aggregation. Studies have revealed a synergistic effect between cavitation and agitation stresses in promoting antibody aggregation [24]. When vials containing protein solutions are subjected to dropping and shaking stresses—as may occur during shipping—cavitation bubbles form and collapse, generating extremely high local temperatures and pressures that can denature proteins [24].

The aggregation pathway induced by these combined stresses involves cavitation-induced unfolding followed by adsorption of unfolded antibodies to the container interface, then shaking-induced desorption of these adsorbed molecules, ultimately leading to particle formation [24]. This understanding informs stabilization strategies, such as adding nonionic surfactants like polysorbate 80, which lowers surface tension and prevents protein adsorption to interfaces [24].

Table 3: Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Hydration Studies

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation package |

| AMBER | Software | Molecular dynamics simulation and force field |

| GROMOS 54a7 | Force Field | Empirical potential for biomolecular simulations |

| TIP3P/TIP4P | Water Model | Molecular representation of water properties |

| HINT | Scoring Function | Quantifies hydrophobic and polar interactions |

| GIST | Analysis Method | Grid-based solvation thermodynamics |

| Polysorbate 80 | Surfactant | Prevents protein adsorption at interfaces |

| PPARγ-Rosiglitazone | Protein-Ligand System | Model for studying hydration in allosteric modulation |

Water's role as an active participant in biological processes extends far beyond that of a passive solvent. The evolution from the historical clathrate cage model to the modern understanding of cavity creation and solvent entropy represents significant advancement in our conceptual framework. The gain in translational entropy of water molecules, resulting from reduced water-accessible surface area during folding, provides the fundamental driving force for protein stabilization, though through excluded volume effects rather than the breakdown of hypothetical ordered structures.

Computational methodologies, particularly Molecular Dynamics simulations coupled with advanced analysis techniques like Grid Inhomogeneous Solvation Theory, have revolutionized our ability to probe these phenomena at atomic resolution. These approaches enable researchers to decompose the enthalpic and entropic contributions to hydrophobicity, revealing the intricate balance of forces that govern biomolecular folding and recognition.

The practical implications of these insights span from drug design to biopharmaceutical development, informing strategies to optimize solubility, stability, and formulation. As computational power continues to grow and methodologies refine further, our understanding of water's active role in biological systems will undoubtedly deepen, opening new avenues for therapeutic intervention and biomolecular engineering.

For decades, the dominant paradigm in protein folding has emphasized the hydrophobic effect as the primary driving force, with the burial of non-polar side chains considered the fundamental organizing principle. This view posits that proteins fold to sequester hydrophobic residues away from aqueous solvent, forming a stable hydrophobic core. However, emerging research challenges the exclusivity of this narrative, revealing that the complete picture of protein stability and folding kinetics is far more complex. A comprehensive reassessment now points to the critical, and perhaps dominant, contributions of the protein backbone and polar groups—elements largely overlooked in traditional hydrophobicity-centric models.

The limitations of a purely hydrophobic framework become apparent when considering that the hydrophobic effect alone cannot explain the precise structural specificity of the native state or the rapid kinetics of folding. Statistical mechanical analyses indicate that the forces on hydrophilic groups are generally stronger than those on hydrophobic groups, with the magnitude of force on assemblies of hydrophilic groups dependent on their ability to form direct hydrogen bonds [25]. Furthermore, advanced simulation studies quantifying contributions to mechanical stability reveal that hydrophobic interactions account for only one-fifth to one-third of the total resistance to unfolding, with the remainder attributed primarily to hydrogen bonds [10]. This paper synthesizes recent experimental and computational evidence to establish a more balanced model of protein folding that fully incorporates the essential roles of the backbone and polar interactions.

Theoretical Foundation: Re-evaluating the Forces in Protein Folding

Statistical Mechanical Formalism of Folding Forces

A rigorous statistical mechanical framework helps clarify the distinct contributions to protein folding. The total potential of mean force (PMF) or free energy governing folding arises from both direct interatomic forces within the protein and solvent-induced forces. For a protein with configuration RM in a solvent of N water molecules with configuration XN, the partition function of the system is:

[ Q(T,V,N_T;R^M) = C \int e^{-\beta U(R^M,X^N)} dX^N ]

where ( \beta = (k_BT)^{-1} ), and ( U(R^M,X^N) ) represents the total potential energy of the system [25]. The thermodynamic force on any specific group i of the protein is then defined as the gradient of the Helmholtz energy with respect to positional changes of that group:

[ F(Ri) = -\nablai A(T,V,NT;R^M) = \frac{\int e^{-\beta U(R^M,X^N)} [-\nablai U(R^M,X^N)] dX^N}{\int e^{-\beta U(R^M,X^N)} dX^N} ]

This formalism separates forces into two categories: direct forces arising from interactions with other protein atoms, and solvent-induced forces arising from interactions with water molecules. Analysis of these components reveals that hydrophilic groups (HϕI) generally experience stronger forces than hydrophobic groups (HϕO), with the magnitude of force on HϕI assemblies being particularly dependent on their orientation and capacity to form hydrogen bonds [25].

The Hydrogen Bond Inventory Fallacy

The historical underestimation of polar contributions stems partly from the flawed "hydrogen bond inventory" argument, which suggested that intra-protein hydrogen bonds contribute minimally to stability because similar bonds could form with water in the unfolded state [25]. This perspective neglected the fundamental cooperativity of hydrogen bonding in proteins and the precise geometric alignment possible in the native state. Current estimates indicate that an intra-protein hydrogen bond can contribute up to 1.5 kcal/mol to stability, significantly more than previously thought [25].

Table 1: Quantitative Contributions of Different Interactions to Protein Stability

| Interaction Type | Estimated Energy Contribution | Primary Role in Folding |

|---|---|---|

| Intra-protein H-bond | Up to 1.5 kcal/mol [25] | Structural specificity, stability |

| Hydrophobic interaction | Variable, often <1 kcal/mol [25] | Global compaction, core formation |

| Protein-water H-bond | Contributes to net stability | Solvation, unfolded state destabilization |

| Electrostatic | Context-dependent | Directional stabilization, salt bridges |

Experimental Evidence: Quantitative Studies of Force Contributions

Mechanical Unfolding Simulations

Steered molecular dynamics simulations with constant-velocity pulling provide direct quantification of the forces resisting mechanical unfolding. These studies generate force-extension curves that reveal the distinct contribution patterns of different interaction types. For selected protein domains, hydrophobic forces account for only between one fifth and one third of the total force, with the remainder attributed primarily to hydrogen bonds [10].

A crucial finding is the different extension-dependency of these forces: hydrophobic force peaks shift toward larger protein extensions compared to force peaks from hydrogen bonds [10]. This indicates that hydrogen bonds provide early resistance to unfolding, while hydrophobic interactions persist longer during the extension process. The relative importance of hydrogen bonds over hydrophobic interactions in mechanical resistance contrasts with their traditional weighting in thermodynamic stability, highlighting the context-dependent nature of these contributions.

Water-Protein Hydrogen Bonding in Denatured States

Studies of the cold denatured state (CDS) and hot denatured state (HDS) of yeast frataxin provide additional insights into the role of hydration in protein stability. Research shows that water molecules in the bulk and at the protein interface form on average the same number of hydrogen bonds, with interface waters compensating for reduced water-water hydrogen bonds by forming additional protein-water hydrogen bonds [9].

At lower temperatures (272 K), where bulk water molecules form approximately 3.77 hydrogen bonds, the protein adapts by populating polyproline II conformations and becoming more expanded, allowing water to form approximately 83 additional hydrogen bonds with the protein that stabilize the cold denatured state [9]. In contrast, the hot denatured state (323 K) is more compact and richer in secondary structure, particularly α-helices, as water at higher temperatures forms fewer hydrogen bonds (approximately 3.55 per molecule) [9]. These structural adaptations demonstrate how proteins respond to maintain optimal hydrogen bonding with solvent across temperatures.

Table 2: Structural Properties of Cold vs. Hot Denatured States in Yeast Frataxin

| Property | Cold Denatured State (272 K) | Hot Denatured State (323 K) | Native State (298 K) |

|---|---|---|---|

| α-helical content | 6% | 10% | Higher than both denatured states |

| β-sheet content | 0.7% | 1.4% | Higher than both denatured states |

| Polyproline II content | 15% | 5% | Lower than denatured states |

| Radius of gyration | 1.7 nm | 1.6 nm | 1.5 nm |

| Average native contacts (Q) | 0.18 | 0.22 | 1.0 |

| Water H-bonds (bulk) | 3.77 | 3.55 | 3.66 |

Surface Hydrophobic Clusters in Coreless Proteins

The study of disintegrins—cysteine-rich proteins that lack a conventional hydrophobic core—provides exceptional insight into alternative stabilization strategies. These proteins maintain stability and solubility despite exposing hydrophobic residues on their surface through the formation of surface hydrophobic clusters (SHCs) [26].

SHCs are dynamic structural elements where exposed hydrophobic residues are protected by adjacent polar side chains and the shielding effect of protein solvation [26]. NMR CLEANEX experiments measuring water exchange rates (kex) of backbone amide hydrogens reveal that residues near SHCs exhibit higher local stability and protection from water exchange, while residues in the binding cleft show faster exchange with water and lower local stability [26]. This segregation of hydrophobic and solvent-permeable regions on opposite faces of the protein demonstrates how polar interactions and strategic solvation patterns can compensate for the absence of a traditional hydrophobic core.

Methodologies: Experimental Approaches for Studying Polar Contributions

NMR Characterization of Denatured States and Solvent Exchange

Restrained Molecular Dynamics with NMR Chemical Shifts

Purpose: To determine high-resolution structural ensembles of denatured states under various conditions [9].

Procedure:

- Acquire NMR chemical shift data for protein under denaturing conditions (e.g., 272 K for cold denaturation, 323 K for heat denaturation)

- Incorporate experimental chemical shifts as restraints in replica-averaged metadynamics (RAM) simulations

- Enhance conformational sampling through metadynamics while maintaining agreement with experimental data

- Analyze resulting structural ensembles for secondary structure content, radius of gyration, and solvent accessibility

- Calculate hydrogen bonding patterns for water molecules in bulk and at protein interface

Key Parameters: Chemical shift restraints, temperature conditions, simulation convergence criteria [9].

CLEANEX Experiments for Water Exchange Rates

Purpose: To identify protein regions with varying solvent accessibility and protection [26].

Procedure:

- Perform CLEANEX NMR experiments at multiple pH values (e.g., 6.0, 6.5, 7.0, 7.5)

- Measure water exchange rates (kex) of backbone amide hydrogens

- Map residues with fast exchange (kex > 1 s-1) versus protected residues

- Correlate exchange rates with structural features and stability measurements

- Identify surface hydrophobic clusters through segregation analysis of hydrophobic residues

Key Parameters: pH values, mixing times for CLEANEX, temperature, kex threshold for "fast exchange" [26].

Computational Approaches for Force Decomposition

Steered Molecular Dynamics with Constant-Velocity Pulling

Purpose: To decompose forces resisting mechanical unfolding into hydrophobic and hydrogen bonding contributions [10].

Procedure:

- Set up protein system with explicit solvent and appropriate force field

- Apply constant-velocity pulling to terminal residues

- Generate force-extension curves throughout unfolding trajectory

- Monitor hydrophobic surface exposure and hydrogen bond formation during extension

- Quantify force contributions by analyzing energy components and their spatial-temporal distribution

Key Parameters: Pulling velocity, force field parameters, solvation model, analysis methods for hydrophobic versus polar forces [10].

Φ-Value Analysis of Transition States

Purpose: To characterize differences in folding pathways under different conditions [9].

Procedure:

- Perform Φ-value analysis for both cold and hot denaturation processes

- Use Φ-values as restraints in molecular dynamics simulations

- Determine cold transition state (CTS) and hot transition state (HTS)

- Compare structural features of alternative transition states

- Correlate transition state differences with solvent hydrogen bonding capacity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Protein Folding Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds | NMR spectroscopy for structural studies | 15N- and 13C-labeled amino acids for protein expression [9] [26] |

| Chemical Denaturants | Protein unfolding studies, free energy calculations | Urea, guanidinium hydrochloride for denaturation curves [26] |

| Surfactants/Deter gents | Membrane protein studies, unfolding/refolding assays | Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) for surfactant-induced unfolding [27] |

| Molecular Biology Tools | Protein expression and purification | Cloning vectors, expression systems for recombinant protein production |

| NMR Buffer Systems | Maintaining protein stability under varying conditions | pH buffers (e.g., phosphate, Tris) for CLEANEX experiments at multiple pH values [26] |

| Specialized Software | Data analysis, molecular dynamics simulations | Biotite for sequence analysis [28], Gecos for color scheme generation [29], Mol* for visualization [30] |

Implications for Drug Development and Protein Engineering