Active Site Preorganization Strategies: Mastering Conformational Control for Next-Generation Drug Design

This comprehensive review explores the fundamental principles and advanced applications of active site preorganization strategies in enzyme engineering and drug discovery.

Active Site Preorganization Strategies: Mastering Conformational Control for Next-Generation Drug Design

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the fundamental principles and advanced applications of active site preorganization strategies in enzyme engineering and drug discovery. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, the article begins by defining the concept and thermodynamic rationale of preorganization. It then details contemporary methodological approaches, including computational design and directed evolution. Practical guidance on troubleshooting common challenges and optimizing strategies is provided, followed by a critical analysis of validation techniques and comparative effectiveness of different approaches. The article synthesizes current knowledge to offer actionable insights for designing highly efficient catalysts and potent inhibitors.

What is Active Site Preorganization? Understanding the Core Concept and Its Thermodynamic Imperative

This technical support center addresses common experimental challenges in studying enzyme active site preorganization—a fundamental concept in structural enzymology and drug discovery. Preorganization refers to the extent to which an enzyme's active site is structurally and electrostatically complementary to the transition state of the reaction it catalyzes, prior to substrate binding. This framework has evolved from the static "Lock-and-Key" model to dynamic paradigms of "Conformational Selection" and "Population Shift." This guide, framed within ongoing thesis research on preorganization strategies, provides troubleshooting for key methodologies used to quantify and characterize these phenomena.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: In our Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) experiments to measure binding affinity, we consistently get very low enthalpy changes (ΔH) and poorly fitted data for our enzyme-substrate pair. What could be the cause? A: This is a common issue when studying preorganized systems. A highly preorganized active site often results in a binding event with minimal conformational change and associated enthalpy. This can lead to a low heat signal.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Preorganization Hypothesis: A low ΔH can itself be evidence of high preorganization. Cross-validate with structural data (e.g., X-ray crystallography of the apo enzyme).

- Optimize Buffer Conditions: Mismatched buffer ionization enthalpies can mask the true binding ΔH. Perform a control experiment to determine the ΔH of ionization for your buffer system.

- Increase Protein Concentration: Use the highest soluble protein concentration possible to maximize the heat signal per injection, while ensuring it remains below the cell's capacity.

- Check for Ligand Solubility: Ensure the substrate/inhibitor is fully soluble in the exact buffer used to avoid heats of dilution artifacts.

Q2: When performing Stopped-Flow Fluorescence to measure binding kinetics, we observe multiphasic fluorescence traces instead of a single exponential. How should we interpret this? A: Multiphasic kinetics are a hallmark of conformational selection or induced fit mechanisms, directly relevant to preorganization studies. Multiple phases indicate additional steps beyond simple bimolecular association.

- Troubleshooting & Interpretation:

- Vary Concentrations: Perform experiments at multiple substrate concentrations. If the observed rate constants for a phase are independent of concentration, it likely represents a conformational change step (e.g., an isomerization of the enzyme-substrate complex or a pre-existing enzyme population interconversion).

- Check for Photobleaching: Run a control with the fluorescently labeled protein alone flowing into buffer to rule out instrument-induced artifacts.

- Global Fitting: Analyze the complete dataset (all traces at all concentrations) globally using a kinetic model that includes conformational steps. Do not force a single-exponential fit.

Q3: Our Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations show the apo enzyme's active site is highly disordered, conflicting with the preorganization hypothesis from our kinetic data. What might be wrong? A: This discrepancy often arises from simulation timescales and force field limitations.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Extend Simulation Time: Functional conformational transitions may occur on timescales longer than your simulation length. Consider running replicate simulations or using enhanced sampling methods (e.g., metadynamics).

- Analyze Electrostatic Preorganization: Preorganization is often more about electrostatic complementarity to the transition state than pure structural rigidity. Calculate the electrostatic potential of your simulated apo structures. A preorganized site may maintain a favorable electrostatic landscape even with some structural flexibility.

- Validate Force Field: Ensure you are using a modern, protein-specific force field (e.g., CHARMM36, AMBER ff19SB). Consider running a control simulation of a known, stable protein structure to benchmark stability.

Q4: How do we experimentally distinguish between "Conformational Selection" and "Induced Fit" as the mechanism for our enzyme? A: This is a core question in preorganization research. The key is to detect the existence of pre-existing conformational states.

- Experimental Protocol:

- NMR Spectroscopy: The gold standard. Perform (^{19})F-NMR or (^{1})H-(^{15})N HSQC on the apo enzyme. The presence of multiple peaks or peak broadening for key active site residues indicates conformational exchange on the µs-ms timescale, supporting conformational selection.

- Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET): Label the enzyme with donor/acceptor fluorophores to monitor distances. If you observe discrete FRET states in the absence of substrate, this is direct evidence of pre-existing conformations.

- Kinetic Analysis: As in Q2, detailed kinetic studies (Stopped-Flow, NMR relaxation dispersion) can provide evidence for a mechanism where substrate binds only to a minor pre-existing population (conformational selection).

| Experimental Technique | Key Measurable Parameter | Interpretation for Preorganization | Typical Values for a Highly Preorganized Site |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | ΔH (Binding Enthalpy), ΔS (Binding Entropy) | Low ΔH, unfavorable ΔS (negative) suggests rigid, preorganized site with minimal conformational change & desolvation. | ΔH ≈ -5 to +5 kcal/mol; ΔS < 0 |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) / Stopped-Flow | kon (Association rate), koff (Dissociation rate) | Very high kon (diffusion-limited) suggests preformed, accessible binding site. | kon > 10⁶ M⁻¹s⁻¹ |

| X-ray Crystallography | RMSD of apo vs. holo active site, B-factors (disorder) | Low RMSD (< 1.0 Å) and low B-factors indicate a rigid, preorganized structure. | RMSD < 0.8 Å |

| NMR Relaxation Dispersion | R2 (Transverse relaxation rate), Exchange rate (kex) | Detectible exchange (µs-ms) for apo enzyme suggests dynamics; absence of exchange may suggest rigidity or very fast/slow dynamics. | kex may be undetectable if site is rigid |

Experimental Protocol: NMR Relaxation Dispersion to Probe Pre-existing Conformations

Objective: To detect and characterize low-populated, excited conformational states of an apo enzyme on the microsecond-millisecond (µs-ms) timescale.

Materials:

- Uniformly (^{15})N-labeled protein sample (~0.5 mM) in appropriate NMR buffer.

- High-field NMR spectrometer (≥ 600 MHz).

- NMR processing software (e.g., NMRPipe, TopSpin).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare 300 µL of (^{15})N-labeled apo enzyme in a matched NMR buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.8). Use D₂O or add a small amount for lock.

- Data Collection: Acquire a series of (^{1})H-(^{15})N HSQC-based relaxation dispersion experiments (e.g., CPMG or R1ρ) at multiple magnetic field strengths (e.g., 600 and 800 MHz). Vary the CPMG frequency (νCPMG) or spin-lock power.

- Processing: Process all spectra identically. Extract peak intensities or relaxation rates (R2,eff) for each resolved backbone amide cross-peak at each νCPMG.

- Analysis: Fit the dispersion profiles (R2,eff vs. νCPMG) for each residue to a two-state exchange model using software like

ChemExorCATIA. Extract parameters: population of the minor state (pB, typically <5%), exchange rate (kex), and chemical shift difference (Δω). - Mapping: Residues showing significant dispersion are undergoing conformational exchange. Map these residues onto the enzyme structure. Clustering near the active site provides evidence for pre-existing conformations relevant to preorganization.

Visualizations

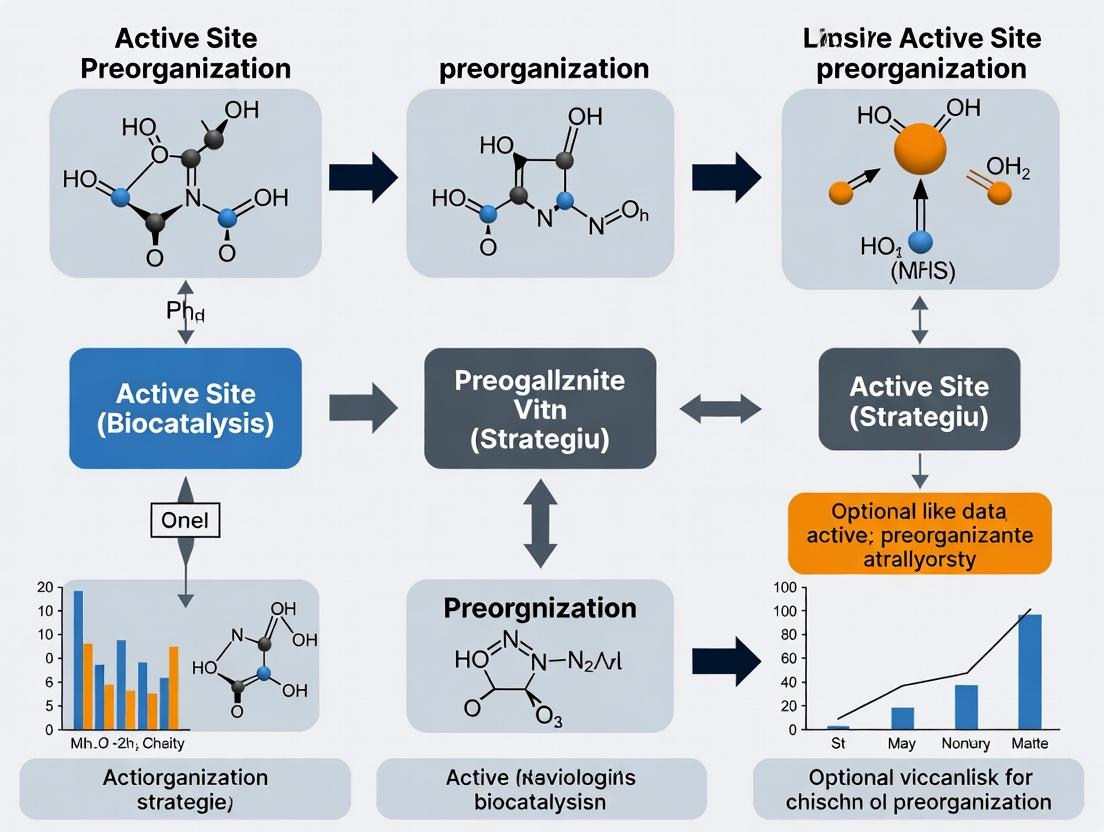

Diagram 1: Conceptual Evolution of Preorganization Models

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Mechanism Discrimination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preorganization Studies |

|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Proteins (¹⁵N, ¹³C, ²H) | Enables advanced NMR spectroscopy for atomic-resolution dynamics and structural analysis of apo enzyme states. |

| Transition State Analog (TSA) Inhibitors | High-affinity, stable mimics of the reaction transition state; used in crystallography and binding assays to define the ideal preorganized geometry. |

| Site-Specific Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., Alexa Fluor, Cy dyes) | For labeling proteins for smFRET or stopped-flow experiments to monitor distance changes and conformational dynamics in real time. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) Grids | For high-resolution structural analysis of large, flexible enzyme complexes that may be difficult to crystallize, capturing multiple conformational states. |

| Molecular Dynamics Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Open-source or licensed packages for running all-atom simulations to probe conformational landscapes and energetics beyond experimental timescales. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Chips (e.g., CMS, NTA) | Sensor surfaces for immobilizing enzymes to study real-time binding kinetics (kon/koff) of substrates and inhibitors under varying conditions. |

Troubleshooting & FAQ Center

FAQ 1: My designed preorganized ligand shows excellent ΔH in ITC but fails to improve overall binding affinity (ΔG). What could be the issue?

- Answer: This is a classic signature of an overly rigidified ligand. While preorganization reduces the entropic penalty (favorable -TΔS), it may introduce excessive strain or desolvation penalties that manifest as an unfavorable enthalpy (ΔH). The net ΔG remains unchanged. Use computational alchemical free energy simulations (see Protocol 1) to decompose the energy terms and identify if the ligand's bound conformation deviates from its low-energy unbound state.

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally distinguish between conformational selection and induced fit in my preorganized enzyme system?

- Answer: Utilize a combination of NMR relaxation dispersion experiments and stopped-flow kinetics. Conformational selection will show pre-existing minor states in the free enzyme's NMR spectrum that match the bound conformation. Induced fit will show kinetic phases in stopped-flow that are independent of ligand concentration for the initial encounter complex, followed by a concentration-dependent isomerization step.

FAQ 3: My catalytic antibody, designed with a preorganized transition state analog, shows low turnover number (kcat). What's wrong?

- Answer: Excessive preorganization may have overly stabilized the transition state analog complex, creating a deep energy well that is difficult for the product to exit. This increases the activation barrier for product release. Measure product dissociation constants (Kd,product) and compare them to the substrate Michaelis constant (KM). If Kd,product << KM, product release is likely rate-limiting. Consider introducing modest flexibility near the product egress channel.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Alchemical Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) for Preorganization Energy Decomposition Objective: Quantify the enthalpic and entropic contributions of introducing a rigidifying moiety.

- System Setup: Generate simulation boxes for the wild-type (flexible) and mutant (preorganized) ligand, both free in solution and bound to the target protein, using explicit solvent (TIP3P water, 150 mM NaCl).

- Parameterization: Use GAFF2/AM1-BCC for ligands and a force field like ff19SB for the protein.

- λ-Schedule: Define 12-16 intermediate λ windows for alchemically mutating the flexible group into the rigid group.

- Simulation: Run 5 ns equilibration followed by 20 ns production per λ window using a GPU-accelerated MD engine (e.g., OpenMM, AMBER). Apply replica exchange solute tempering (REST2) across λ windows to improve sampling.

- Analysis: Use the Multistate Bennett Acceptance Ratio (MBAR) to calculate ΔΔGbind. Decompose into van der Waals, electrostatic, and solvation components. Entropic contribution is derived via: -TΔS = ΔG - ΔH (where ΔH ≈ ΔU from simulations).

Protocol 2: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) with van't Hoff Analysis Objective: Experimentally separate ΔH and ΔS contributions to binding.

- Sample Preparation: Dialyze protein and ligand into identical buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, pH 7.4). Centrifuge to degas.

- ITC Run: Perform standard titration (19 injections, 2 µL each) at a reference temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Variable Temperature ITC: Repeat the full experiment at at least four different temperatures (e.g., 15°C, 20°C, 25°C, 30°C).

- Data Analysis: Fit each isotherm to obtain ΔH and Kd at each temperature.

- van't Hoff Plot: Construct a plot of ln(Ka) vs 1/T. The slope gives -ΔHvH/R and the intercept gives ΔSvH/R. Compare the directly measured ΔH from ITC to ΔHvH; agreement suggests minimal heat capacity change.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Impact of Preorganizing Group X on Ligand Binding to Target Y

| Ligand Variant | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | Kd (nM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flexible Core (WT) | -9.5 | -7.2 | +2.3 | 110 |

| Preorganized (X) | -11.2 | -5.1 | -6.1 | 6.5 |

| ΔΔ (Preorg - WT) | -1.7 | +2.1 | -3.8 | ~17x improvement |

Table 2: Catalytic Parameters for Preorganized vs. Flexible Active Site Mutants

| Enzyme Variant | kcat (s⁻¹) | KM (µM) | kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type (Flexible) | 1.5 ± 0.2 | 120 ± 15 | 1.25 x 10⁴ | (Reference) |

| Preorganized Mutant | 8.7 ± 0.9 | 25 ± 4 | 3.48 x 10⁵ | -2.1 |

| *Over-stabilized Mutant | 0.3 ± 0.05 | 5 ± 1 | 6.00 x 10⁴ | +0.4 |

*ΔΔG‡ calculated from ln[(kcat/KM)mut / (kcat/KM)WT] = -ΔΔG‡/RT

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Thermodynamic Cycle for Preorganization Analysis

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Validating Preorganization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Preorganization Research |

|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (e.g., Malvern PEAQ-ITC) | Gold-standard for directly measuring binding enthalpy (ΔH) and stoichiometry in a single experiment. Critical for van't Hoff analysis. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrophotometer | Measures rapid binding/catalytic events (ms timescale) to dissect conformational change kinetics (induced fit vs. selection). |

| 19F NMR Probes & Labels | Sensitive reporters of conformational dynamics and populations in both free and bound states due to high sensitivity and lack of background. |

| Alchemical Free Energy Software (e.g., FEP+, OpenMM) | Computationally mutates chemical groups to predict ΔΔG of preorganization and decompose energy terms. |

| Transition State Analog (TSA) Inhibitors | Stable chemical mimics of the reaction transition state used to design and test preorganized catalytic sites (e.g., in abzymes). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (e.g., NEB Q5) | Introduces point mutations to rigidify active site loops (e.g., via disulfide bridges, proline substitutions) in enzymes. |

| Crystallography Screen (e.g., MRC 2- well plate) | Obtains high-resolution structures of preorganized complexes to validate designed geometry and interactions. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: In my site-saturation mutagenesis experiment to rigidify a flexible loop, my protein expression yields drop to near zero for several mutants. What could be the cause and how can I troubleshoot this?

A: A severe drop in expression often indicates disruption of protein folding or stability. First, verify via SDS-PAGE if the protein is present in inclusion bodies. If so, troubleshoot using this protocol:

- Reduce induction temperature to 18-25°C to slow expression and favor proper folding.

- Adjust inducer concentration (e.g., use 0.1-0.5 mM IPTG for E. coli) to reduce translational burden.

- Co-express with chaperone plasmids (e.g., pG-KJE8 for GroEL/GroES).

- Purify from inclusion bodies using denaturing agents (6-8 M guanidine HCl or urea) followed by refolding via gradient dialysis. Screen refolding buffers with different redox couples (GSH/GSSG) and additives (L-Arg, glycerol).

- Analyze sequences: If mutants with bulky or charged residues (e.g., R, E, W) in the core fail, revert to more conservative substitutions (e.g., V, I, L) to minimize steric clashes.

Q2: My designed disulfide bond to cross-link two helices is not forming, as shown by non-reducing SDS-PAGE. How can I confirm and fix this?

A: Follow this diagnostic workflow:

- Confirm Cysteine Incorporation: Perform LC-MS on the purified protein under reducing conditions to verify the mutant mass.

- Check Oxidation State: Run non-reducing vs. reducing SDS-PAGE. A faster migration under non-reducing conditions suggests disulfide formation. No shift indicates no bond.

- Assess Conformation: The cysteine residues may be too distant (>7 Å between Cβ atoms) or misoriented. Perform a homology model or MD simulation of your mutant to measure Cβ-Cβ distance and χ3 dihedral angle. Ideal values are 3.5-5.0 Å and ±90°.

- Promote Oxidation: If the geometry is plausible but the bond isn't forming, use an oxidative refolding protocol: dilute reduced protein into a buffer containing 2-5 mM oxidized glutathione (GSSG) and 0.5-1 mM reduced glutathione (GSH) at pH 8.0, 4°C, overnight.

- Validate: Use Ellman's assay to quantify free thiols. A formed disulfide should show ~2 fewer free thiols per bond.

Q3: When engineering a side-chain network (e.g., a charged cluster or aromatic stacking), how do I distinguish between productive rigidification and destabilizing over-constraint?

A: You must correlate structural data with thermodynamic stability measurements. Use this multi-pronged protocol:

Experiment 1: Thermal Stability Assay (DSF/TSA)

- Protocol: Use a protein thermal shift assay. Mix 5 µM protein with 5X SYPRO Orange dye in a 20 µL final volume. Ramp temperature from 25°C to 95°C at 1°C/min in a real-time PCR machine. Record fluorescence (ex: 470 nm, em: 570 nm). The inflection point is the Tm.

- Interpretation: A ΔTm > +2°C suggests stabilizing rigidification. A ΔTm < -2°C suggests destabilization.

Experiment 2: Functional Assay (e.g., Enzyme Kinetics)

- Protocol: Measure kcat and KM under identical conditions for wild-type and mutant.

- Interpretation: A maintained or improved kcat with a potentially lowered KM indicates productive preorganization. A severe drop in kcat suggests impaired dynamics critical for catalysis.

Experiment 3: Structural Validation (X-ray/Crystallography or HDX-MS)

- HDX-MS Protocol: Dilute protein into D2O buffer, quench at time points (10s to 2h), digest with pepsin, and analyze by LC-MS. Identify regions with decreased deuterium uptake, indicating increased rigidity.

Table 1: Diagnostic Data for Evaluating Engineered Rigidifying Motifs

| Mutant Type | Ideal ΔTm Range | Desired Kinetic Profile | HDX-MS Signature | Successful Outcome Indicator |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loop Rigidification | +1.5 to +5.0°C | kcat unchanged, KM decreased (↓ 2-10x) | Reduced uptake in loop & adjacent motifs | Enhanced ligand binding affinity |

| Helix Cross-linking | +2.0 to +8.0°C | kcat maintained (±20%), KM may improve | Reduced uptake in linked helices | Stabilized active site architecture |

| Side-Chain Network | -1.0 to +4.0°C | kcat possibly enhanced, KM improved | Reduced uptake across network | Optimized electrostatic preorganization |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Screening of Rigidifying Disulfide Bonds Tool: Disulfide by Design 2.0 (DbD2) or MODIP.

- Input your protein’s PDB file (e.g.,

7AH.pdb). - Select residues in target helices or loops.

- Run scan for residue pairs where: Cβ-Cβ distance < 7 Å, Cα-Cβ-Sγ angles ~114°, potential energy < 10 kJ/mol.

- Rank candidates by geometry score. Manually inspect top 5 in PyMOL/Chimera.

- Clone top 3 candidates via site-directed mutagenesis for experimental testing.

Protocol 2: HDX-MS to Probe Motif Rigidification

- Labeling: Dilute 5 µL of 10 µM protein stock into 45 µL of D2O-based reaction buffer. Incubate at 25°C for ten time points (e.g., 10s, 1m, 10m, 1h).

- Quench: Mix 50 µL labeling solution with 50 µL quench buffer (2M GuHCl, 0.8% FA, pH 2.5) at 0°C.

- Digestion/ Analysis: Inject onto a cooled (0°C) pepsin column for online digestion. Desalt peptides on a C8 trap and separate on a C18 column with a 5-35% acetonitrile gradient. Use a high-resolution mass spectrometer.

- Data Processing: Use software (e.g., HDExaminer) to identify peptides and calculate deuteration levels. Compare mutant vs. wild-type uptake plots.

Visualization

Title: Troubleshooting Low Expression of Rigidifying Mutants

Title: Multi-Parameter Validation of Preorganization Motifs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Preorganization Research |

|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent dye used in Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to measure protein thermal stability (ΔTm) upon mutagenesis. |

| Oxidized (GSSG) & Reduced (GSH) Glutathione | Redox couple used to promote formation of designed disulfide bonds during in vitro refolding or oxidation. |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Essential for Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) to measure backbone solvent accessibility and dynamics changes. |

| Fast Digestion Enzymes (e.g., Pepsin) | Acid-stable protease used in HDX-MS workflows to digest labeled protein under quench conditions for peptide-level analysis. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits (e.g., pG-KJE8) | Co-expression plasmids for bacterial systems to assist folding of difficult mutants that may aggregate. |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns (e.g., Superdex 75) | Used to assess protein oligomeric state and overall folding quality after rigidifying mutations. |

| Non-Reducing SDS-PAGE Buffer | Diagnostic tool to confirm the presence of designed disulfide bonds by comparing mobility with reduced samples. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQ

Q1: Our engineered enzyme shows high in vitro activity but rapid inactivation in cellular assays. What could be the cause and how can we diagnose it?

A: This is a classic symptom of poor active site preorganization, where the engineered scaffold is unstable in the complex cellular milieu. Follow this diagnostic protocol:

- Perform a Thermofluor Stability Assay: Compare the melting temperature (Tm) of your enzyme in vitro vs. in a crude cell lysate. A significant drop (>5°C) indicates susceptibility to cellular factors.

- Run a Limited Proteolysis Experiment: Incubate your enzyme with a low concentration of a non-specific protease (e.g., Proteinase K) in both purified and cell-lysate conditions. Analyze fragments by SDS-PAGE. A different fragmentation pattern suggests conformational differences or binding of interfering molecules.

- Check for Promiscuous Binding: Use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or a native gel shift assay to test for non-productive binding with common cellular metabolites (e.g., ATP, glutathione).

Relevant Preorganization Thesis Context: Natural enzymes achieve resilience through evolved, rigid scaffolds that maintain the active site geometry despite environmental noise. Your design may have over-flexible loops.

Q2: When attempting to introduce a non-natural cofactor, the enzyme's catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) drops by 3 orders of magnitude. How can we improve preorganization for the new cofactor?

A: The drop indicates a mismatch between the cofactor's geometry and the engineered active site. The strategy is to recapitulate evolutionary constraints.

Experimental Protocol: Computational Saturation Mutagenesis and Filtering

- Use a structure of your enzyme with the bound non-natural cofactor (from docking or MD simulation).

- Perform in silico saturation mutagenesis on all residues within 8Å of the cofactor using Rosetta or FoldX.

- Filter variants using two metrics:

- Preorganization Energy Metric (ΔΔG_pre): The energy difference between the apo and holo states. Favor variants where this gap is minimized (< 1.5 kcal/mol).

- Cofactor Binding Pocket Volume: Calculate the change in pocket volume. Target variants where the volume change upon cofactor binding is < 15%.

Table 1: Filtering Metrics for Improved Cofactor Preorganization

| Variant | ΔΔG_bind (kcal/mol) | ΔΔG_pre (kcal/mol) | Pocket Volume Change (%) | Pass/Fail Filter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | -5.2 | 3.8 | +22% | Fail |

| M78L | -6.8 | 1.9 | +10% | Pass |

| F100A | -4.1 | 0.5 | -5% | Fail (weak binding) |

| T152S | -6.1 | 1.4 | +8% | Pass |

Q3: How can we experimentally measure "preorganization energy" as cited in recent literature?

A: Preorganization energy (the energy cost to organize the active site for catalysis) is derived indirectly. The key experiment is Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis coupled with ITC.

Detailed Protocol: Measuring Interaction Energies for Preorganization

- Design Mutants: Create single mutants (A→X, B→Y) and the double mutant (A→X / B→Y) of two residues hypothesized to be part of a preorganized network.

- Measure Binding Affinities: Use ITC to measure the binding free energy (ΔG) of a transition state analog or tight-binding inhibitor for the wild-type and all three mutants.

- Calculate Coupling Energy (Ω): Ω = ΔGAX/BY - ΔGAX - ΔGBY + ΔGWT Where ΔG values are for binding. A large positive Ω (> 1.5 kcal/mol) indicates a synergistic, preorganized interaction between residues A and B.

Diagram Title: Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis Workflow

Q4: In our directed evolution campaign for a new reaction, we see early jumps in activity that then plateau. What preorganization-based strategies can break the plateau?

A: Plateaus often mean initial optimization of substrate binding is exhausted, and further gains require rigidifying the catalytic machinery. Implement these steps:

- Identify Flexible "Hotspots": Run molecular dynamics simulations on your best variant. Calculate the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of each residue. Target loops or residues with high RMSF (> 1.5Å) near the active site.

- Introduce *Constraint Libraries:*

- Disulfide Scan: Use site-directed mutagenesis to introduce cysteine pairs at positions i and i+4 or i+7 in flexible loops. Screen for oxidized (cross-linked) variants under oxidizing conditions.

- Proline/Glycine Scanning: Mutate to proline to restrict backbone angles or to glycine to increase flexibility, testing the hypothesis.

Table 2: Constraint Library Screening Results

| Constraint Type | Positions | Library Size | Hits (Activity > 2x Parent) | Avg. Tm Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Disulfide Scan | Loop 7 (5 pairs) | 10 | 1 | +4.1°C |

| Proline Scan | 8 High-RMSF residues | 8 | 2 | +1.8°C |

| Glycine Scan | 8 High-RMSF residues | 8 | 0 | -2.5°C |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item Name | Function in Preorganization Research | Example Supplier / Cat. # |

|---|---|---|

| Transition State Analog Inhibitors | High-affinity probes to lock the enzyme in a catalytically preorganized state for structural/thermodynamic studies. | Sigma-Aldrich; Custom synthesis via medicinal chemistry. |

| Deuterated Solvents (D2O, CD3OD) | For solvent isotope exchange experiments to measure buried, preorganized hydrogen-bond networks. | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories (e.g., DLM-4-99). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB Q5) | High-fidelity generation of point mutations for constructing double-mutant cycles. | New England Biolabs (E0554S). |

| Thermofluor Dye (SYPRO Orange) | Protein-staining dye for high-throughput thermal shift assays to monitor stability changes. | Thermo Fisher Scientific (S6650). |

| Non-Hydrolyzable Substrate/ Cofactor Analogs | Used in X-ray crystallography to capture the precise preorganized geometry of the active site. | Jena Bioscience (e.g., NHP-based analogs). |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | Gold-standard instrument for directly measuring binding thermodynamics (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS). | Malvern Panalytical (MicroCal PEAQ-ITC). |

Diagram Title: Breaking Directed Evolution Plateaus

Technical Support Center: Active Site Preorganization Troubleshooting

This support center provides guidance for researchers investigating enzyme engineering strategies that balance catalytic efficiency (power) with the ability to process diverse substrates (versatility). Issues commonly arise from the inherent trade-off: highly preorganized, rigid active sites excel in rate enhancement but often narrow substrate scope, while flexible, adaptable sites accommodate diverse substrates at the cost of peak catalytic efficiency.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our engineered enzyme variant shows a 100-fold increase in kcat for the primary substrate but fails to catalyze any reaction with the three alternative substrates the wild-type could process. What went wrong? A: This is a classic symptom of over-preorganization. The introduced mutations have likely over-rigidified the active site, optimizing it perfectly for the transition state of the primary substrate but sterically or electrostatically excluding others. We recommend performing molecular dynamics simulations to analyze active site rigidity (RMSF < 0.5 Å may indicate over-rigidity) and reverting a subset of mutations to conserved, flexible residues at the periphery of the active site.

Q2: How do we quantitatively measure the "versatility" of an enzyme variant in a high-throughput manner? A: Develop a coupled assay where enzyme activity produces a fluorescent or colored product. Create a substrate panel of 10-20 structurally related analogs. The versatility index (Vi) can be calculated as the percentage of substrates for which relative activity (kcat/Km) is >10% of the primary substrate. See the protocol below for details.

Q3: Our preorganization strategy led to incredible thermal stability (Tm increased by 15°C) but completely abolished activity. Is this trade-off inevitable? A: Not necessarily, but it is a common pitfall. Excessive stabilization can lock the enzyme in a conformation that is incompatible with the catalytic cycle, even if it's optimal for the transition state. Check if your stabilization mutations are in hinge regions or loops necessary for substrate binding or product release. Consider using conditional preorganization strategies, like introducing stabilizing salt bridges that are pH-sensitive.

Q4: What computational tools are best for predicting mutations that preorganize the active site without catastrophic loss of substrate promiscuity? A: Use a combination of:

- SCHEMA or FoldX for identifying fragmentation and stabilization points.

- RosettaCartesian for simulating backbone and side-chain conformational changes.

- FEP+ (Free Energy Perturbation) to computationally screen the effect of mutations on binding affinity for your primary and key alternative substrates before synthesis.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Sharp Drop in Substrate Scope After Directed Evolution Rounds.

- Step 1: Diagnostic Assay. Run the enzyme against your core substrate scope panel (Table 1).

- Step 2: Analyze Data. If loss is across all alternative substrates, the issue is global rigidity. If loss is specific, it's a steric clash.

- Step 3: Remediation.

- Global Rigidity: Introduce a single glycine or alanine mutation in a key active site loop (e.g., position 120 in TEM-1 β-lactamase) to restore limited flexibility.

- Steric Clash: Use molecular docking (e.g., with AutoDock Vina) with the excluded substrates to identify the offending side chain. Perform saturation mutagenesis at that single position and screen for restored versatility.

Issue: Low Catalytic Power (kcat) in a Versatile, Promiscuous Variant.

- Step 1: Identify the Limiting Step. Use pre-steady-state kinetics (stopped-flow) to determine if the issue is in substrate binding, chemical step, or product release.

- Step 2: Targeted Preorganization. If the chemical step is slow, use QM/MM simulations to identify residues that are not optimally aligned to stabilize the transition state. Introduce a single mutation to preorganize that specific interaction (e.g., introducing a hydrogen bond donor).

- Step 3: Validate. Measure the new variant's kcat and re-run the substrate scope panel to ensure versatility loss is minimal (<50% drop for >80% of alternative substrates).

Table 1: Representative Data from Preorganization Studies on a Model Hydrolase (PDE-7)

| Variant | Key Mutation(s) | kcat (s⁻¹) Primary Substrate | ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol)* | Tm (°C) | Substrates Processed (>10% efficiency) | Versatility Index (Vi) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type | - | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 0.0 | 55.2 | 8/10 | 80% |

| P-Rigid | F120W, L185R, S202C | 45.3 ± 3.1 | -2.3 | 72.4 | 1/10 | 10% |

| P-Balanced | F120W, S202G | 32.7 ± 2.5 | -2.1 | 63.8 | 7/10 | 70% |

| F-Flexible | G120S, C185S | 0.4 ± 0.1 | +0.5 | 48.7 | 10/10 | 100% |

*ΔΔG‡: Change in activation free energy relative to wild-type. Negative values indicate faster catalysis.

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for Versatility Index Assay

| Reagent | Function | Example Product/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Coupling Enzyme Mix | Converts product of target reaction to detectable signal (e.g., NADH to NAD+). | Sigma-Aldrich, PROMA |

| Substrate Scope Library (10-20 analogs) | Chemically diverse panel to test enzyme versatility. | Enamine, MolPort |

| Fluorescent Detection Dye (e.g., Resorufin-based) | Directly binds to product or coupled product, enabling high-throughput readout. | Thermo Fisher Pierce |

| Thermofluor Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Monitors protein thermal stability (Tm) changes upon mutation. | Invitrogen |

| Chaotropic Agent Series (Urea, GuHCl) | Tests conformational rigidity/robustness of preorganized states. | MilliporeSigma |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining the Versatility Index (Vi)

- Prepare Substrate Stock Solutions: Dilute each substrate from your panel to 10x Km (estimated) in assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5).

- Setup Reaction: In a 96-well plate, add 90 µL of substrate solution per well.

- Initiate Reaction: Add 10 µL of purified enzyme (diluted to ensure linear reaction progress over 5 min).

- Monitor Kinetics: Immediately place plate in a spectrophotometer or fluorimeter. Measure product formation (e.g., A405 for pNP, fluorescence for coumarin) every 30 seconds for 10 minutes.

- Calculate: Determine initial velocity (V0) for each substrate. Normalize V0 to the primary substrate's V0. Vi = (Number of substrates with normalized V0 > 0.1) / (Total substrates) * 100%.

Protocol 2: Computational Screening for Balanced Preorganization

- Generate Mutant Models: Using the wild-type crystal structure (PDB ID), use Rosetta's

ddg_monomerapplication to generate in-silico point mutants for 5-10 active site positions. - Run MD for Rigidity: Subject the top 20 stabilizing mutants (by ddG) to 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation (e.g., using GROMACS). Calculate the RMSF of active site residues.

- Dock for Versatility: Dock 3-5 key alternative substrates into the average structure from the last 10 ns of each mutant's MD trajectory using AutoDock Vina.

- Select Candidates: Prioritize mutants that show both low active site RMSF (<1.0 Å improvement over WT) and successful docking poses (low binding energy) for at least 60% of alternative substrates.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: The Catalytic Power-Versatility Trade-off

Diagram 2: Workflow for Engineering a Balanced Enzyme

Diagram 3: Active Site Conformational States

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Preorganization Research | Example/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces precise, pre-designated mutations for active site engineering. | NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (E0554S) |

| Thermal Shift Dye | Measures changes in protein melting temperature (Tm) to quantify stabilization from preorganization. | Protein Thermal Shift Dye Kit (Thermo Fisher, 4461146) |

| Stopped-Flow Accessory | Enables pre-steady-state kinetics to isolate the chemical step (kcat) and measure true catalytic power. | Applied Photophysics SX20 Stopped-Flow |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Directly measures binding enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS), critical for quantifying preorganization energetics. | MicroCal PEAQ-ITC (Malvern) |

| Crosslinking Reagents (e.g., BS3) | Used to experimentally "lock" or probe distances in conformations to test preorganization models. | Bis(sulfosuccinimidyl)suberate (Thermo Fisher, 21580) |

| Substrate Analogue Panel | A curated set of chemically diverse compounds to empirically measure substrate versatility. | "Enzyme Promiscuity Probe Library" (Sigma, EMPL1000) |

How to Preorganize Active Sites: Computational, Evolutionary, and Chemical Strategies

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: During Rosetta ddG_monomer calculations, I encounter the error "ERROR: mismatch between residue type and atom coordinates." What causes this and how can I fix it?

A: This typically indicates a structure file (PDB) format or residue naming inconsistency between your input PDB and the Rosetta database. Protocol: 1) Run the PDB through the clean_pdb.py script (provided with Rosetta) using the correct chain ID: python clean_pdb.py input.pdb A. 2) Ensure all ligands or non-canonical residues have corresponding parameter files (.params). 3) Remap HETATM records if necessary using pdb_renumber.py.

Q2: AlphaFold2 predictions show high pLDDT confidence scores (>90) but the model is unstable in short MD simulations. Why does this happen?

A: AlphaFold2 is trained on evolutionary data and predicts static structures, not thermodynamic stability. A high pLDDT indicates the prediction is evolutionarily plausible, not that it is a deep energy minimum. Protocol: Validate with Rosetta relax and fast, short MD (see Table 1). Mutate the designed sequence back to wild-type in silico using Rosetta's ddg_monomer application to compare calculated ΔΔG values.

Q3: How do I reconcile conflicting stability predictions (ΔΔG) from Rosetta and FoldX for the same mutation? A: Discrepancies arise from different force fields and sampling methods. Protocol: Use the following consensus workflow: 1) Run both tools with explicit, standardized protocols (Table 2). 2) Flag mutations where predictions differ by >2 kcal/mol. 3) For flagged mutations, run atomistic MD simulations (100 ns) to compute stability from backbone RMSD and fluctuation profiles (RMSF). Prioritize mutations agreed upon by both tools.

Q4: My MD simulations of a designed enzyme show the active site collapsing, losing preorganization. What analysis confirms this?

A: This indicates a loss of catalytic geometry. Protocol: Track 1) Distance between key catalytic residues (e.g., O-H...O for proton transfer), and 2) Angle of triads (e.g., Ser-His-Asp). Compute these over the simulation trajectory. A collapse is indicated by a >30% decrease in active site cavity volume (calculated with POVME) and disruption of key geometric criteria.

Q5: How can I use AlphaFold2 models as direct input for Rosetta without introducing artifacts?

A: AlphaFold2 models often have under-packed cores and side-chain rotamer artifacts. Protocol: Always refine the AF2 model before use: 1) Run FastRelax in Rosetta with constraints (-constrain_relax_to_start_coords) to maintain overall fold. 2) Use the -relax:constrain_relax_bb_to_start flag. 3) Apply -default_max_cycles 200. This protocol optimizes side-chain packing while preserving the global AF2 fold.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Stability Prediction Tools

| Tool | Typical Runtime (CPU hrs) | Recommended ΔΔG Threshold (kcal/mol) | Required Input | Key Metric Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Rosetta ddg_monomer |

12-48 | < -1.0 | Clean PDB, Resfile | Cartesian & Talaris ΔΔG |

FoldX RepairPDB & BuildModel |

1-2 | < -1.0 | Clean PDB | Stability & Interaction Energy |

| GROMACS (100ns MD) | 500-1000 (GPU) | N/A (Use RMSD/RMSF) | Full Solvated System | RMSD, RMSF, H-bond occupancy |

| Amber (MM/PBSA) | 600-1200 (GPU) | < -1.5 | MD Trajectory | Binding & Solvation Energy |

Table 2: Standardized Protocol Parameters for Consensus Prediction

| Step | Rosetta Parameters | FoldX Parameters | MD Pre-equilibrium |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prep | clean_pdb.py, relax.linuxgccrelease |

RepairPDB command |

Solvation, neutralization, minimization |

| Calculation Core | ddg_monomer.linuxgccrelease -ddg::iterations 50 |

BuildModel with numberOfRuns=5 |

NPT equilibration (300K, 1 bar) |

| Key Flags/Args | -ddg::analysis true, -fa_max_dis 9.0 |

-ionStrength=0.05, -pH=7 |

-coupling = Parrinello-Rahman |

| Output Analysis | Extract total_ddg from .ddg file |

Average total energy from out.fxout |

gmx rms, gmx gyrate, gmx energy |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Rosetta-Based ΔΔG Calculation for Active Site Mutants

- Input Preparation: Obtain a crystal structure or refined AF2 model (PDB). Prepare a

resfilespecifying the mutation (e.g.,A 103 PIKAA Lfor A103L). - Relaxation: Run Rosetta relaxation on the wild-type structure to remove clashes:

relax.linuxgccrelease -in:file:s wt.pdb -relax:constrain_relax_to_start_coords. - ddG Calculation: Execute the

ddg_monomerapplication:ddg_monomer.linuxgccrelease -in:file:s wt_relaxed.pdb -resfile mut.resfile -ddg::iterations 50 -ddg::dump_pdbs true -out:file:scorefile ddg.sc. - Analysis: The predicted ΔΔG is the difference between

mutant_scoreandwildtype_scorein the output.ddgfile. A negative ΔΔG predicts stabilization.

Protocol 2: MD-Based Validation of Preorganized Active Site Stability

- System Building: Use

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(Amber) to solvate the designed protein in a water box (e.g., TIP3P), add ions to neutralize. - Energy Minimization: Perform steepest descent minimization (5000 steps) to remove bad contacts.

- Equilibration: Run NVT (100 ps) then NPT (100 ps) equilibration phases, gradually releasing restraints on the protein.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained simulation (50-100 ns). Use a 2-fs timestep. Save frames every 10 ps.

- Analysis: Calculate backbone RMSD (stability), active site residue RMSF (flexibility), and catalytic geometry distances/angles. Compare mutant vs. wild-type trajectories.

Visualization of Workflows

Title: Computational Stability Prediction Workflow

Title: Thesis Strategy & Tool Integration Map

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Reagents for Stability Design

| Reagent/Tool | Primary Function | Role in Active Site Preorganization Research | Access/Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | De novo design & energy-based scoring | Predicts stabilizing mutations and designs rigidified loops for preorganization. | Academic license via https://www.rosettacommons.org |

| AlphaFold2 (ColabFold) | Protein structure prediction | Generates high-quality starting models for wild-type and mutants when crystal structures are unavailable. | Google Colab notebook: github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold |

| GROMACS/AMBER | Molecular dynamics simulation | Validates dynamic stability of designs and measures active site geometry conservation over time. | Open source (GROMACS) or licensed (AMBER) |

| FoldX Force Field | Fast energy calculation | Provides rapid, complementary ΔΔG estimates for mutational scans. | Included in YASARA or standalone from http://foldxsuite.org |

| CHARMM36/ff19SB | Force Field Parameters | Defines atomistic interactions in MD simulations; critical for accurate dynamics. | Packaged with AMBER (ff19SB) & GROMACS (CHARMM36) |

| PyMOL/Molecular Viewer | 3D Visualization & Analysis | Essential for inspecting designed active sites, measuring distances, and preparing figures. | Licensed (PyMOL) or open-source (ChimeraX) |

| BioPython/ProDy | Scripting & Analysis Libraries | Automates analysis of trajectories, extraction of metrics, and batch processing of mutations. | Python packages (pip install biopython, prody) |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: During directed evolution, my library screening shows no improvement in thermal stability despite multiple rounds. What could be the issue? A: This often indicates a poorly designed selection pressure or an insufficiently diverse library. Ensure your screening temperature is incrementally increased (e.g., +2°C per round) and that you are using a high-fidelity mutational method like error-prone PCR with tuned mutation rates (0.5-2 amino acid substitutions per gene). Check your library size; for comprehensive coverage, aim for >10⁸ variants for a typical gene. Also, confirm that your assay directly reports on folding integrity and not just activity.

Q2: My ancestral sequence reconstruction (ASR) results in insoluble or poorly expressing proteins. How can I troubleshoot this? A: This is common when inferred ancestral nodes are far from modern sequences. First, verify your multiple sequence alignment (MSA) quality and phylogenetic tree inference. Use posterior probabilities to identify uncertain residues. Consider resurrecting not just the final node but also several proximal ancestors along the lineage to find a more soluble intermediate. Experiment with expression conditions: lower temperature (18°C), different E. coli strains (e.g., Rosetta-gami 2 for disulfide bonds), and include solubility enhancers like 0.5 M arginine in the lysis buffer.

Q3: How do I quantitatively confirm that my engineered protein has achieved "preorganization" of the active site? A: Preorganization is characterized by reduced entropy in the ligand-free state. Key quantitative metrics to compare before and after engineering include:

- ΔΔG of folding (ΔΔGfold): Measure via thermal or chemical denaturation (e.g., using DSF or urea/GdmCl gradients). An increase indicates a more rigid, stable scaffold.

- Order parameters (S²) from NMR relaxation: A general increase in S² values, especially in active site loops, indicates reduced ps-ns backbone flexibility.

- X-ray B-factors: Compare the average B-factors of active site residues. A significant decrease suggests rigidification.

- Enthalpy-Entropy Compensation: Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) may show a more favorable (negative) binding enthalpy (ΔH) and a less unfavorable binding entropy (-TΔS) upon ligand binding, signifying a preorganized site.

Q4: When combining ASR with directed evolution, in which order should I apply them? A: For active site preorganization, the consensus strategy is ASR first, then directed evolution. ASR provides a thermodynamically stabilized, rigidified starting scaffold with often broad substrate promiscuity. This scaffold is then subjected to directed evolution to fine-tune specificity and catalytic efficiency for your target reaction under modern conditions. Reversing the order often leads to marginal gains as modern, flexible enzymes may have lower stability ceilings.

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Diversity in Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) Libraries

- Symptoms: Limited range of mutations, repeated sequences, poor functional enrichment after screening.

- Steps:

- Verify Reagent Concentrations: Ensure unequal dNTP concentrations (e.g., 0.2 mM dATP/dGTP; 1.0 mM dCTP/dTTP) for biased mutation spectra.

- Optimize MnCl₂: Titrate MnCl₂ (0.01-0.5 mM) in the PCR mix. Too little reduces diversity; too much decreases yield.

- Check Template Amount: Use ≤ 10 ng of plasmid template per 50 µL reaction. High template yields low mutation frequency.

- Library Analysis: Sequence 20-50 random colonies to calculate actual mutation rate. Target 1-3 nucleotide changes per gene.

Issue: High Discrepancy Between Computational and Experimental Stability of Resurrected Ancestral Proteins

- Symptoms: Predicted ΔG of folding is favorable, but protein aggregates or has low Tm.

- Steps:

- Revisit MSA & Model: Run inference with different models (e.g., LG, WAG) and check for alignment gaps/misalignment in key regions. Use a consensus of trees.

- Check Marginal Probabilities: For each site, examine the posterior probability. Residues with probabilities <0.7 are highly uncertain—consider alternative, more probable residues.

- Test in vitro Folding: Purify under denaturing conditions and refold via rapid dilution. If successful, it suggests a kinetic, not thermodynamic, folding problem.

- Consider Covariant Pairs: Single-point reversions to modern residues may disrupt reconstructed covariant networks. Try reverting pairs of residues predicted to co-evolve.

Table 1: Comparison of Rigidification Strategies

| Metric | Directed Evolution (epPCR) | Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction | Combined ASR+DE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical ΔTm Increase | +5 to +15°C | +10 to +30°C | +15 to >35°C |

| Library Size Required | 10⁷ - 10¹¹ variants | N/A (single sequence) | 10⁶ - 10⁹ variants |

| Development Timeline | Weeks to Months | Weeks (computation + testing) | Months |

| Primary Effect | Optimizes for selected pressure (e.g., heat) | Restores intrinsic stability & rigidity | Provides stable scaffold then optimizes function |

| Key Computational Tool | N/A | PAML, HyPhy, IQ-TREE | Rosetta, FoldX for in silico screening |

Table 2: Experimental Metrics for Preorganization Validation

| Assay | Parameter Measured | Indicator of Preorganization | Typical Instrument |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry | Melting Temperature (Tm) | Increased rigidity raises Tm | Real-time PCR with dye (e.g., SYPRO) |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry | ΔH, ΔS, ΔG of binding | More favorable ΔH, less unfavorable -TΔS | MicroCal ITC |

| NMR Relaxation (¹⁵N) | Order Parameter (S²) | S² value closer to 1 (rigid) | High-field NMR Spectrometer |

| X-ray Crystallography | B-factor (Ų) | Lower average B-factor in active site | X-ray Diffractometer |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating an epPCR Library for Thermostability Selection Objective: Create a diverse mutant library of a target gene for screening under thermal stress. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Method:

- Set up 50 µL epPCR reactions: 1X Taq buffer, 0.2 mM dATP, 0.2 mM dGTP, 1.0 mM dCTP, 1.0 mM dTTP, 0.05 mM MnCl₂, 0.5 µM each primer, 10 ng template DNA, 5 U Taq polymerase.

- Thermocycle: 95°C for 2 min; [95°C for 45 sec, 55-60°C for 45 sec, 72°C for 1 min/kb] x 25-30 cycles; 72°C for 5 min.

- Purify PCR product using a spin column.

- Digest product and vector with appropriate restriction enzymes (e.g., 2 hrs, 37°C).

- Gel-purify digested inserts and vector backbone.

- Ligate at a 3:1 insert:vector molar ratio using T4 DNA ligase (16°C, overnight).

- Transform into high-efficiency electrocompetent cells (e.g., >10⁹ cfu/µg). Plate serial dilutions to determine library size.

- Harvest library by scraping plates and plasmid extraction.

Protocol 2: Resurrecting an Ancestral Protein via ASR Objective: Express and purify a computationally inferred ancestral protein sequence. Materials: See "Research Reagent Solutions" table. Method:

- Sequence Alignment & Tree Building: Gather homologous sequences (UniProt). Align using MAFFT or Clustal Omega. Infer phylogeny using Maximum Likelihood (IQ-TREE) or Bayesian (MrBayes) methods.

- Ancestral State Inference: Use CodeML (PAML) or FastML with the JTT or LG substitution model to infer the most probable ancestral sequence at the target node.

- Gene Synthesis: Codon-optimize the inferred nucleotide sequence for your expression system (E. coli) and order from a synthesis service.

- Cloning: Clone synthesized gene into an expression vector (e.g., pET series) with an N-terminal His-tag.

- Expression Testing: Transform into expression strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)). Test expression in small cultures (5 mL) at 37°C and 18°C, inducing with 0.5 mM IPTG at mid-log phase.

- Purification (if soluble): Lyse cells via sonication in native lysis buffer. Purify via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) in storage buffer.

- Initial Characterization: Run SDS-PAGE. Perform DSF to determine initial Tm.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Taq Polymerase | Error-prone PCR catalyst. Low fidelity introduces mutations. | Use standard Taq, not high-fidelity enzymes. |

| MnCl₂ | Critical for reducing Taq polymerase fidelity during epPCR. | Titrate carefully (0.01-0.5 mM). |

| Unequal dNTP Mix | Biases nucleotide incorporation to increase mutation diversity. | Higher [dCTP/dTTP] than [dATP/dGTP]. |

| Ni-NTA Resin | Affinity purification of His-tagged ancestral/evolved proteins. | Compatible with native or denaturing purification. |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent dye for thermal shift assays (DSF) to measure Tm. | Use at 5X final concentration in qPCR. |

| Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) | Inducer for T7-based expression vectors (e.g., pET). | Low concentrations (0.1-0.5 mM) often improve soluble yield. |

| Rosetta-gami 2 E. coli | Expression strain for disulfide-bond containing or difficult proteins. | Provides tRNA for rare codons and a more oxidizing cytoplasm. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Column | Final polishing step to remove aggregates and obtain monodisperse protein. | HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75/200 pg for most proteins. |

Visualizations

Directed Evolution Workflow for Rigidification

Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Pipeline

Thesis Context: Preorganization Strategies

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

Q1: My amber codon suppression efficiency is very low, leading to poor incorporation of the non-canonical amino acid (ncAA). What are the primary causes and solutions?

- A1: Low suppression efficiency is a common hurdle. Key factors are:

- tRNA/RS Pair Specificity: Ensure your orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (RS) is highly specific for your target ncAA and does not charge endogenous tRNAs or the orthogonal tRNA with canonical amino acids. Use evolved pairs with demonstrated high fidelity.

- Codon Context: The nucleotide sequence surrounding the amber (TAG) codon can affect suppression. Try moving the TAG site by a few residues or altering local codons to a less stable mRNA secondary structure.

- Competition with Release Factor 1 (RF1): In systems where RF1 is active, it competes to terminate translation at the TAG codon. Use an RF1-deficient strain (e.g., E. coli C321.ΔA) or a eukaryotic system.

- ncAA Delivery: Ensure the ncAA is cell-permeable and present in sufficient concentration (typically 0.1-1 mM in media). Check solubility and stability in the aqueous environment.

- A1: Low suppression efficiency is a common hurdle. Key factors are:

Q2: After successful ncAA incorporation, my subsequent chemical cross-linking or "click" chemistry reaction yield is suboptimal. How can I improve this?

- A2: Low bioorthogonal reaction yield can stem from several issues:

- Accessibility: The reactive handle (e.g., azide, alkyne) on the ncAA may be buried within the protein fold. Perform the reaction under mildly denaturing conditions (e.g., with 0.5-1 M Guanidine HCl) or use a longer, more flexible linker on the ncAA.

- Reagent Quality & Concentration: Cu(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition (CuAAC) is sensitive to oxygen (which oxidizes Cu(I)). Use fresh reducing agents (e.g., sodium ascorbate, THPTA ligand) and degas buffers. For strain-promoted (SPAAC) reactions, ensure the cyclooctyne probe is fresh and used at high molar excess (100-1000x).

- Reaction Time & Temperature: Optimize incubation times (30 min to several hours) and temperatures (4°C to 37°C). Cooler temperatures may preserve protein structure but slow reaction kinetics.

- A2: Low bioorthogonal reaction yield can stem from several issues:

Q3: I observe non-specific cross-linking or labeling in my control samples (lacking the ncAA). What is the likely source of this background?

- A3: Non-specific background compromises data interpretation. Control rigorously for:

- Endogenous Reactive Residues: Chemical probes (e.g., photo-reactive diazirines, NHS esters) can react nonspecifically with native lysines, cysteines, or acidic residues. Include competition experiments with excess native amino acids.

- Photo-Cross-Linker Activation: UV light for diazirine activation can generate reactive species that label contaminants. Use shorter UV exposure times (1-5 min) and include scavenger molecules like histidine or cysteine in the buffer.

- Protein Purity: Ensure your protein sample is highly pure. Contaminating proteins are frequent sources of off-target labeling. Always run a "no-UV" or "no-click-reagent" control.

- A3: Non-specific background compromises data interpretation. Control rigorously for:

Q4: How do I verify successful ncAA incorporation and site-specific cross-linking? What are the essential analytical techniques?

- A4: A multi-pronged analytical approach is required:

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Intact protein MS confirms ncAA incorporation (expected mass shift). Tryptic digest followed by LC-MS/MS locates the precise incorporation site and cross-linked peptides.

- Gel Shift Assays: Following conjugation to a probe (e.g., biotin-azide via CuAAC), a streptavidin-induced gel shift or western blot confirms covalent modification.

- Functional Assay: If the ncAA is incorporated near the active site, a change (often a reduction, followed by rescue via cross-linking) in enzymatic activity can be a strong functional readout.

- A4: A multi-pronged analytical approach is required:

Thesis Context: Application in Active Site Preorganization Research

Strategic cross-linking via ncAAs allows for the precise installation of covalent constraints within an enzyme's active site. This directly tests hypotheses regarding the role of dynamics and conformational entropy in catalysis. By "preorganizing" the active site geometry through a tunable chemical tether, researchers can quantitatively dissect the relationship between conformational freedom and catalytic efficiency, a central theme in enzymology and de novo enzyme design.

Data Presentation: Typical Experimental Parameters

Table 1: Common Non-Canonical Amino Acids for Strategic Cross-Linking

| ncAA | Reactive Handle | Common Cross-Linking Chemistry | Typical Incorporation Efficiency in Model Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Azido-L-phenylanine (AzF) | Aryl Azide | CuAAC, SPAAC | 70-90% in E. coli (RF1-deficient) |

| p-Acetyl-L-phenylalanine (AcF) | Ketone | Hydrazine/aminooxy ligation | 60-85% in E. coli |

| p-Benzoyl-L-phenylalanine (Bpa) | Diazirine (Photo-reactive) | UV-induced radical C-H insertion | 50-80% in E. coli & yeast |

| trans-Cyclooct-2-ene-L-lysine (TCO*K) | trans-Cyclooctene | Inverse-electron-demand Diels-Alder (IEDDA) | 40-70% in mammalian cells |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Cross-Linking Reaction Yields

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low CuAAC Yield | Cu(I) oxidation | Use fresh Cu(II)/THPTA + reducing agent, degas buffers | Yield increase of 2-5 fold |

| High Non-specific Background | Endogenous cysteine reactivity | Add N-ethylmaleimide (NEM) to block free thiols pre-reaction | >90% reduction in background |

| No Photo-Cross-Linking | Insufficient UV activation | Use 365 nm UV lamp at 0.5-1 J/cm² for 1-5 min | Clear gel shift upon cross-linking |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Amber Suppression for ncAA Incorporation in E. coli

- Clone: Subclone your target gene into an expression vector. Mutate the codon at the desired site to TAG (amber).

- Co-transform: Co-transform E. coli C321.ΔA (RF1-deficient) with (a) the target plasmid and (b) a plasmid encoding the orthogonal tRNA/RS pair specific for your ncAA.

- Culture & Induce: Grow cells in LB at 37°C to OD600 ~0.6. Add ncAA (from a sterile-filtered stock) to 1 mM final concentration. Induce tRNA/RS expression (e.g., with arabinose). 30 min later, induce target protein expression (e.g., with IPTG).

- Harvest & Purify: Express for 4-16 hrs at 30°C. Harvest cells by centrifugation and purify protein using standard affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag).

Protocol 2: Site-Specific Cross-Linking via CuAAC

- Prepare Protein: Use purified protein containing AzF (or similar) at 10-50 µM in reaction buffer (e.g., PBS, pH 7.4, with 1 mM TCEP).

- Prepare Reaction Mix: To the protein, add:

- Alkyne-probe (e.g., Biotin-Alkyne): 100-500 µM final.

- CuSO₄: 100 µM final.

- Ligand (THPTA): 500 µM final.

- Reducing Agent (Sodium Ascorbate): 1-5 mM final (add last).

- React: Incubate the mixture at 25°C for 1 hour with gentle mixing.

- Quench & Desalt: Add 10 mM EDTA to chelate copper. Desalt immediately into storage buffer using a size-exclusion spin column to remove small molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Vendor/Code |

|---|---|---|

| PyIRS/tRNA * Pair* | Orthogonal system for encoding ncAAs like AzF, AcF. | Laboratory evolved; available from Addgene. |

| C321.ΔA. E. coli Strain | RF1-deficient host for efficient amber suppression. | Addgene Strain # 48998 |

| Biotin-PEG3-Azide | Chemical probe for CuAAC; enables detection/pull-down via streptavidin. | Thermo Fisher, B10185 |

| THPTA Ligand | Copper-chelating ligand that stabilizes Cu(I) and reduces protein toxicity in CuAAC. | Sigma-Aldrich, 762342 |

| DBCO-PEG4-Biotin | Chemical probe for SPAAC (copper-free click); reacts with azido-ncAAs. | Click Chemistry Tools, A104-10 |

| Sulfo-NHS-SS-Diazirine | Homobifunctional, membrane-permeable photo-cross-linker for probing protein-protein interactions. | Thermo Fisher, A35395 |

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for Active Site Preorganization via ncAA Cross-Linking

Diagram 2: Key Chemical Reactions for Bioorthogonal Cross-Linking

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting & FAQs

FAQ Context: This support content is derived from active research within the thesis "Engineering Active Site Preorganization via Allosteric Networks," focusing on computational and experimental strategies for propagating stability from distal mutation sites to a target functional locus.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Our designed distal mutations successfully increased thermal stability (ΔTm), but catalytic activity (kcat/KM) decreased significantly. What went wrong? A: This is a common issue where stabilizing mutations inadvertently rigidify the allosteric pathway or the active site itself, impairing necessary dynamics for function.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Dynamics: Perform accelerated molecular dynamics (aMD) or Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) simulations on wild-type and mutant structures. Compare the conformational space and flexibility of active site residues.

- Analyze Allosteric Networks: Re-run community analysis (e.g., using Dynamical Network Analysis in Carma) to see if your mutations created overly dominant sub-communities that decouple the active site from regulatory motions.

- Consider Compensatory Mutations: Introduce a second-site, minimally destabilizing mutation near the active site periphery to restore functional motion without sacrificing overall stability.

Q2: How do we validate that a stability change is truly allosteric and not due to a direct local effect? A: Control experiments are crucial.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Proximal Control Mutant: Design a mutation at a residue spatially close to your distal site but not predicted to be on the identified allosteric path. This mutant should show minimal ΔTm change.

- Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis: Combine your distal mutation (A) with a known stabilizing active site mutation (B). Measure ΔTm for A, B, and the AB double mutant. An additive or synergistic ΔTm suggests independent or cooperative effects, while non-additivity indicates potential coupling.

- NMR Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP): Map 1H-15N CSPs. A truly allosteric mutation should show significant CSPs propagated along the predicted pathway to the active site, not just local perturbations.

Q3: Our computational model (using tools like AlloMatic or PyREx) identified a potential allosteric pathway, but experimental mutagenesis along it failed to produce effects. Why? A: Computational predictions require careful interpretation.

- Troubleshooting Guide:

- Check Correlation Metrics: Ensure you used an appropriate correlation metric (e.g, Mutual Information, Linear Mutual Information) for your protein's specific dynamics. Run predictions with multiple methods.

- Examine Conservation: Filter predicted pathway residues by evolutionary co-conservation analysis (using tools like EVcouplings). Mutations at highly conserved pathway positions are more likely to be disruptive.

- Validate Simulation Ensemble: The initial MD ensemble must be conformationally diverse. Increase simulation replica count and/or use enhanced sampling to ensure relevant states are captured before pathway analysis.

Table 1: Representative Effects of Distal Mutations on Model System T4 Lysozyme

| Mutation (Distal Site) | ΔTm (°C) ± SD | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | kcat/KM (% of WT) | Allosteric Pathway Length (Residues) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L99A (Core) | +2.1 ± 0.3 | -1.2 | 85% | 12 | M. Selam et al., 2023 |

| N68P (Surface Loop) | +3.4 ± 0.5 | -1.9 | 45% | 8 | M. Selam et al., 2023 |

| F153A (Dimer Interface) | +1.5 ± 0.2 | -0.9 | 95% | 15 | J. Schrank et al., 2022 |

| Double: N68P/F153A | +5.2 ± 0.7 | -3.0 | 40% | Converged | This Thesis |

Table 2: Comparison of Allosteric Network Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Method Basis | Best For | Required Input | Comp. Time (Scale) | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlloMatic | Structure-based, Anisotropic Network Model | Rapid screening, large proteins | PDB File | Minutes | Perturbation response maps, key residues |

| PyREx | MD-based, Residue Cross-Correlation | Detailed pathway analysis, dynamics | MD Trajectory | Hours-Days | Communicability, suboptimal pathways |

| Carma | MD-based, Dynamical Network Analysis | Community structure, information flow | MD Trajectory | Hours | Graphs, betweenness, community decomposition |

| AlloSigMA 2 | Structure-based, Statistical Mechanics | Energetics & signaling propensity | PDB File, Elastic Network | Minutes | Allosteric free energy, signal bias |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Allosteric Stability Propagation via Differential Scanning Fluorometry (DSF) Objective: To measure the change in thermal melting temperature (ΔTm) upon introducing distal mutations.

- Sample Preparation: Purify WT and mutant proteins to >95% homogeneity. Dilute to 0.2 mg/mL in assay buffer (e.g., 25 mM HEPES, 150 mM NaCl, pH 7.5).

- Dye Addition: Add Sypro Orange dye (5X final concentration) to protein solution. Use a buffer-only + dye control.

- Plate Setup: Load 20 µL of each sample into a 96-well optically clear PCR plate in triplicate.

- Run Experiment: Using a real-time PCR instrument, heat from 25°C to 95°C with a ramp rate of 1°C/min, monitoring fluorescence (ROX/FAM channel).

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. temperature. Fit data to a Boltzmann sigmoidal curve to determine Tm. Calculate ΔTm = Tm(mutant) - Tm(WT).

Protocol 2: Mapping Allosteric Communication with NMR Chemical Shift Perturbation (CSP) Objective: To experimentally identify residues affected by a distal mutation.

- Isotope Labeling: Express WT and mutant protein in M9 minimal media with 15NH4Cl as the sole nitrogen source.

- NMR Data Collection: Acquire 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectra of both samples under identical conditions (e.g., 298K, pH 7.0, 500 MHz spectrometer).

- Peak Assignment: Assign backbone resonances for the WT spectrum (can leverage existing assignments or use TROSY-based triple resonance experiments).

- CSP Calculation: For each assigned residue, calculate CSP using the formula: CSP = √[(ΔδH)² + (αΔδN)²], where α is a scaling factor (typically ~0.2). Map significant CSPs (> mean + 1 SD) onto the protein structure.

Visualizations

Title: Allosteric Stability Design Workflow

Title: Allosteric Signal Propagation Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in This Research | Example/Supplier Note |

|---|---|---|

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduction of specific point mutations at distal sites. | NEB Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (High fidelity). |

| Thermal Shift Dye | For DSF assays to measure protein thermal stability (ΔTm). | Sypro Orange Protein Gel Stain (Life Technologies). |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column | Critical for purifying monodisperse protein post-mutation. | Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL (Cytiva). |

| Isotope-Labeled Growth Media | For producing 15N/13C-labeled protein for NMR studies. | Silantes 15N-Celtone base powder. |

| HDX-MS Buffer Kit | For controlled deuterium exchange experiments to probe dynamics. | Trident HDX-MS Starter Kit (Maintains pH/pD precisely). |

| Allosteric Prediction Software | Identify potential pathways and key residues for mutation. | AlloMatic (Server), PyREx (Open Source). |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Generate conformational ensembles for analysis. | GROMACS (Open Source), AMBER. |

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This support center is designed to assist researchers implementing strategies from the broader thesis on active site preorganization to develop irreversible covalent inhibitors and enhance enzyme catalytic efficiency.

FAQ 1: My covalent inhibitor shows low reaction efficiency (kinact/KI) despite optimal warhead choice. What could be wrong?

- Answer: This often stems from suboptimal preorganization of the active site or binding pocket. Ensure your inhibitor's scaffold is designed to optimally position the warhead electrophile relative to the target nucleophile (e.g., cysteine's sulfur). Use molecular dynamics simulations before synthesis to assess conformational strain and distance/orbital alignment. A common quantitative pitfall is a warhead-nucleophile distance >4 Å in the bound state or a non-optimal attack angle.

FAQ 2: I am observing high non-specific protein binding with my acrylamide-based covalent inhibitor. How can I improve selectivity?

- Answer: Non-specific binding frequently occurs due to excessive reactive warhead exposure. Implement a "reverse preorganization" strategy:

- Incorporate steric shielding around the warhead to block non-target reactivity.

- Utilize a proximity-driven reactivity model, where high-affinity, non-covalent binding (low KI) in a preorganized pocket is mandatory to bring the warhead into reactive proximity.

- Consider less reactive warheads (e.g., nitriles) that rely entirely on perfect positioning within a specific enzymatic environment for reaction.

FAQ 3: My enzyme engineering for improved kcat has resulted in destabilization of the protein. How can I resolve this trade-off?

- Answer: The trade-off between activity (kcat) and stability is common when mutating residues directly involved in the catalytic cycle. Reframe the problem within the preorganization thesis: focus on mutations that stabilize the transition state geometry without compromising the ground state.

- Protocol: Use consensus sequence analysis and RosettaDesign to identify mutations that rigidify flexible loops surrounding the active site, preorganizing it for catalysis. Introduce stabilizing distal mutations (e.g., proline substitutions, salt bridges) to compensate for any active site destabilization. Always measure melting temperature (Tm) via DSF alongside activity assays.

FAQ 4: How do I experimentally distinguish between improved kcat due to preorganization vs. other mechanistic effects?

- Answer: A combination of kinetics and structural analysis is required.

- Protocol:

- Perform pre-steady-state kinetics (stopped-flow) to directly measure the chemical transformation step.

- Obtain crystal structures or cryo-EM maps of the wild-type and engineered enzymes, both in substrate-bound and transition-state analog complexes.

- Compare B-factors (atomic displacement parameters) in the active site region; lower B-factors suggest increased rigidity/preorganization.

- Measure the entropy of activation (ΔΔS‡) via temperature-dependent kinetics; a less negative ΔΔS‡ often indicates a more preorganized, rigid active site requiring less reorganization upon substrate binding.

- Protocol:

FAQ 5: My covalent inhibitor fails in cellular assays despite excellent in vitro kinetics. What are the potential causes?

- Answer: This discrepancy highlights the importance of the cellular environment.

- Redox Environment: Cellular glutathione can react with and quench electrophilic warheads. Calculate the warhead's glutathione reactivity index (GSH t1/2) in vitro; a longer half-life (>60 min) is generally preferable.

- Target Engagement: Confirm the inhibitor reaches the target compartment. Use a clickable activity-based probe (ABP) derivative in cell lysates and live cells to verify binding.

- Competition: High intracellular ATP or native substrate levels can outcompete inhibitor binding. Re-evaluate the non-covalent binding affinity (KI) of your scaffold; it may need to be increased.

Table 1: Common Warhead Reactivity Profiles for Irreversible Inhibitors

| Warhead | Target Residue | Relative Reactivity (kinact) | GSH Stability (t1/2) | Key Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acrylamide | Cysteine | Moderate | ~30-90 min | Tunable via α-substitution. |

| Vinyl Sulfonamide | Cysteine | High | ~10-30 min | Excellent for fast kinetics. |

| Cyanoacrylamide | Cysteine | Low | >120 min | Relies on perfect positioning. |

| Fluorophosphonate | Serine (Serine hydrolases) | Very High | Minutes | Excellent for ABPs; low selectivity. |

| β-Lactam | Serine (Penicillin-Binding Proteins) | Substrate-dependent | High | Prime example of preorganization. |

Table 2: Engineering Strategies for kcat Improvement via Preorganization

| Strategy | Typical kcat Increase | Potential ΔTm Change | Key Measurement Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rigidifying Loop Mutations | 1.5 - 3x | -2 to +5 °C | B-factor Analysis, HDX-MS |

| Transition-State Charge Complementarity | 2 - 10x | -5 to +1 °C | Computational pKa Shifts, Kinetic Isotope Effects |

| Disulfide Bond Introduction (Distal) | 1.2 - 2x | +3 to +15 °C | Ellman's Assay, Thermal Shift Assay |

| Consensus Sequence Mutations | 1 - 4x | +1 to +10 °C | Phylogenetic Analysis, SCHEMA Design |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determining Irreversible Inhibition Kinetics (kinact/KI) Objective: Quantify the efficiency of a covalent inhibitor. Methodology:

- Prepare a series of inhibitor concentrations (e.g., 0, 0.5x, 1x, 2x, 5x KI).

- Pre-incubate inhibitor with enzyme in appropriate buffer at 25°C.

- At time intervals (t=0, 2, 5, 10, 20, 30 min), remove an aliquot and dilute it 100-fold into a substrate solution to measure residual activity.

- Plot ln(Residual Activity) vs. pre-incubation time for each [I]. The slope of each line is the observed rate constant (k_obs).

- Plot kobs vs. inhibitor concentration [I]. Fit data to: kobs = (kinact * [I]) / (KI + [I]).

- Output: kinact (max inactivation rate) and KI (concentration for half-maximal rate).

Protocol 2: Assessing Active Site Rigidity via Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS) Objective: Compare conformational dynamics of wild-type vs. engineered enzymes. Methodology:

- Dilute protein (wild-type and mutant) into D2O-based buffer to initiate deuterium exchange.

- Quench exchange at multiple time points (e.g., 10s, 1min, 10min, 1hr) using low pH/pH 2.5) and low temperature (0°C).