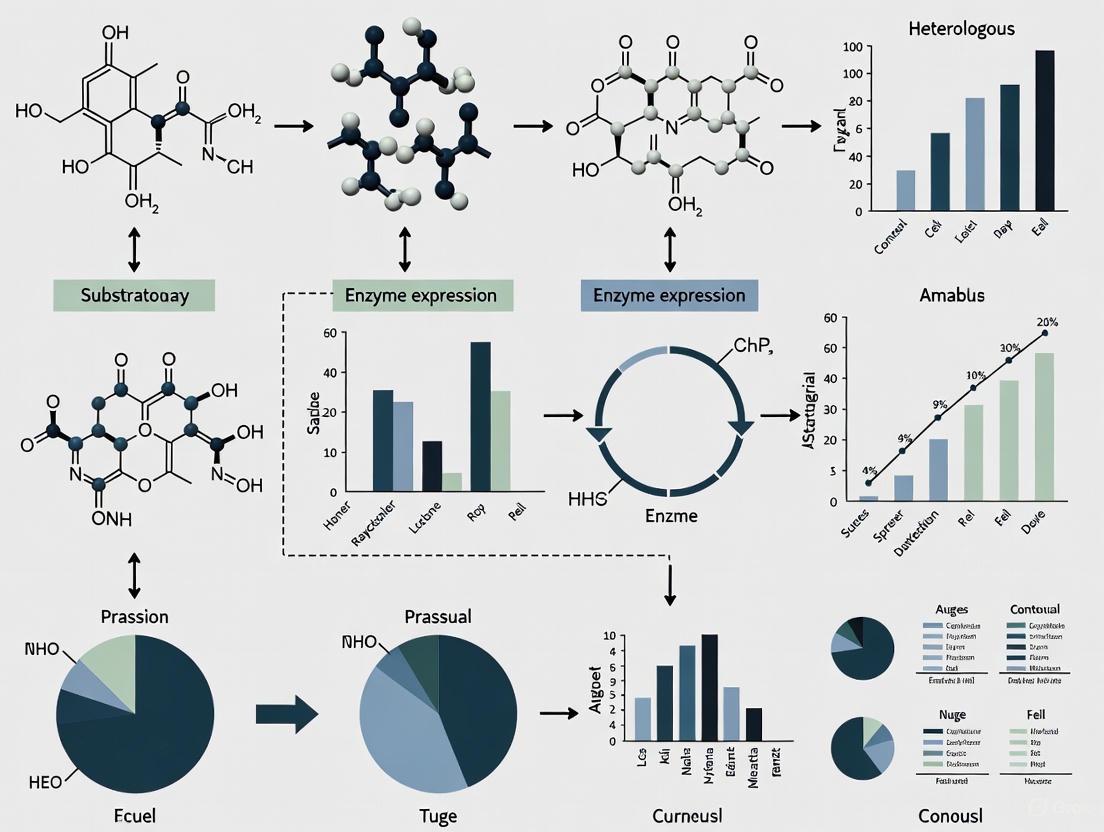

Advanced Strategies for Improving Heterologous Enzyme Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a systematic review of contemporary strategies for enhancing heterologous enzyme expression, addressing critical challenges from foundational concepts to advanced optimization.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Heterologous Enzyme Expression: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a systematic review of contemporary strategies for enhancing heterologous enzyme expression, addressing critical challenges from foundational concepts to advanced optimization. It explores host system selection spanning prokaryotic and eukaryotic platforms, genetic engineering techniques including CRISPR/Cas9 and codon optimization, and secretory pathway engineering. The content covers practical troubleshooting methodologies for common expression failures and outlines rigorous validation frameworks for comparing system performance. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource integrates the latest advances in synthetic biology, multi-omics approaches, and machine learning to enable successful recombinant enzyme production for biomedical and industrial applications.

Understanding Heterologous Expression Systems and Core Challenges

Defining Heterologous Enzyme Expression and Its Biomedical Significance

Heterologous enzyme expression refers to the production of a target enzyme in a host organism that does not naturally synthesize it. This is achieved through recombinant DNA technology, where the gene encoding the enzyme of interest is transferred into a suitable microbial host such as bacteria, yeast, or filamentous fungi. In biomedical contexts, this technology enables the large-scale production of therapeutic enzymes, diagnostic proteins, and vaccine components that would otherwise be difficult or expensive to obtain from their native sources [1] [2].

The global market for biopharmaceutical proteins is approaching $400 billion annually, while the industrial enzyme sector was valued at approximately $7.1 billion in 2023 and is projected to surpass $11 billion by 2028. This growth is driven by increasing demand in food processing, biofuels, and pharmaceutical manufacturing [1]. Microbial expression systems provide scalable and versatile platforms for producing recombinant proteins, offering advantages in yield, cost-efficiency, and environmental sustainability compared to conventional methods [3].

Key Host Systems for Heterologous Enzyme Expression

Different host organisms offer distinct advantages and limitations for heterologous enzyme production. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of commonly used expression systems.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Heterologous Expression Systems

| Host System | Advantages | Limitations | Biomedical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | Rapid growth, easy genetic manipulation, high scalability [1] | Limited post-translational modifications, protein misfolding [1] | Non-glycosylated therapeutic proteins, research enzymes [4] |

| S. cerevisiae | GRAS status, eukaryotic PTMs, protein secretion, well-established tools [5] | Hyperglycosylation, metabolic burden [6] [5] | Vaccine production, therapeutic hormones, industrial enzymes [5] |

| K. phaffii | High protein secretion, controlled glycosylation, strong promoters [6] | More complex culture requirements than S. cerevisiae | High-yield enzyme production (e.g., glucose oxidase) [6] |

| Aspergillus spp. | Exceptional protein secretion, GRAS status, extensive PTMs [1] [7] | High background endogenous proteins, proteolytic degradation [1] | Industrial enzymes, therapeutic proteins, organic acids [7] |

Troubleshooting Common Expression Problems

Low or No Expression

Problem: The target enzyme shows minimal or no detectable expression in the host system.

Solutions:

- Verify construct integrity: Sequence the entire expression cassette to confirm the absence of unintended stop codons or mutations [8].

- Enhance transcription: Use strong, inducible promoters (e.g., PAOX1 in K. phaffii, Tet-on in A. niger) to drive gene expression [1] [6].

- Optimize codon usage: Replace rare codons with host-preferred counterparts to improve translation efficiency [5]. For E. coli, use strains supplemented with rare tRNAs (e.g., Rosetta) [8] [4].

- Increase gene copy number: Integrate multiple copies of the expression cassette into the host genome [6] [5].

Protein Insolubility and Misfolding

Problem: The expressed enzyme forms inclusion bodies or aggregates rather than functional soluble protein.

Solutions:

- Reduce expression rate: Lower induction temperature (15-20°C) or decrease inducer concentration to slow protein synthesis and facilitate proper folding [8] [4].

- Co-express chaperones: Co-produce folding helper proteins (e.g., GroEL, DnaK, ClpB) to assist proper protein folding [8] [4].

- Use fusion tags: Fuse target enzymes with solubility-enhancing partners like maltose-binding protein (MBP) or thioredoxin [8] [4].

- Employ specialized strains: For disulfide bond-containing proteins, use E. coli SHuffle strains with oxidative cytoplasm and disulfide bond isomerase (DsbC) [4].

Inefficient Secretion

Problem: The enzyme fails to secrete efficiently into the culture supernatant, remaining intracellular.

Solutions:

- Signal peptide optimization: Screen or engineer optimal signal peptides for the specific target enzyme. Replace native signal peptides with validated alternatives (e.g., Ost1-αMF in K. phaffii) [6] [9].

- Engineer secretion pathways: Overexpress key components of the secretory machinery, such as COPI vesicle trafficking components (e.g., Cvc2 in A. niger), which enhanced pectate lyase production by 18% [1].

- Reduce extracellular proteolysis: Disrupt major extracellular protease genes (e.g., PepA in A. niger) to minimize target protein degradation [1].

Incorrect Post-Translational Modifications

Problem: The enzyme exhibits improper glycosylation or other PTMs affecting activity or stability.

Solutions:

- Humanize glycosylation patterns: Engineer yeast strains to produce human-like N-glycans by eliminating hypermannosylation and introducing human glycosylation enzymes [5].

- Select appropriate hosts: Use eukaryotic hosts (yeast, filamentous fungi) for enzymes requiring eukaryotic-specific modifications [1] [7].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for Common Heterologous Expression Problems

| Problem | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Methods | Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low/No Expression | Poor transcription, rare codons, mRNA instability | Northern blot, qPCR, sequencing | Stronger promoters, codon optimization, increase gene copies [8] [5] |

| Protein Insolubility | Rapid expression, insufficient chaperones, missing PTMs | SDS-PAGE solubility assay, centrifugation | Lower temperature, fusion tags, chaperone co-expression [8] [4] |

| Inefficient Secretion | Incompatible signal peptide, secretion bottlenecks | Intracellular vs extracellular activity assays | Signal peptide screening, vesicle trafficking engineering [1] [9] |

| Reduced Enzyme Activity | Incorrect folding, improper PTMs, inactive aggregates | Specific activity assays, Western blot | Glycoengineering, disulfide bond enhancing strains [4] [5] |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Signal Peptide Screening Protocol

Objective: Identify optimal signal peptides for efficient enzyme secretion.

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Create a diverse library of signal peptide variants through error-prone PCR or synthetic design [9].

- Reporter Fusion: Fuse signal peptide variants to a reporter protein (e.g., Gaussia luciferase) for rapid secretion screening [9].

- High-Throughput Screening: Express library in 96-well format and measure reporter activity in supernatants using luminometry [9].

- Validation: Transfer best-performing signal peptides to full-length enzyme constructs and quantify expression yields [9].

This approach identified a signal peptide variant that provided a 13.9-fold improvement in unspecific peroxygenase (UPO) expression in S. cerevisiae compared to the wild-type signal sequence [9].

Multi-Copy Integration in Aspergillus niger

Objective: Achieve high-level enzyme expression through genomic integration of multiple gene copies.

Methodology:

- Chassis Strain Engineering: Start with industrial A. niger strain AnN1 containing 20 copies of glucoamylase gene [1].

- CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Deletion: Delete 13 glucoamylase gene copies to create low-background strain AnN2 with 61% reduced extracellular protein [1].

- Target Gene Integration: Integrate heterologous enzyme genes into the vacated high-expression loci using CRISPR/Cas9 with homologous recombination [1].

- Screening and Validation: Select transformants and quantify enzyme expression in shake-flask cultures (48-72 hours) [1].

This platform successfully expressed diverse proteins including glucose oxidase (AnGoxM), thermostable pectate lyase (MtPlyA), bacterial triose phosphate isomerase (TPI), and medicinal protein LZ8, with yields ranging from 110.8 to 416.8 mg/L in 50 mL shake-flasks [1].

Combinatorial Optimization in Komagataella phaffii

Objective: Maximize enzyme production through coordinated genetic enhancements.

Methodology:

- Strain Construction: Clone target enzyme (e.g., glucose oxidase from A. cristatus) into expression vector [6].

- Promoter Enhancement: Replace standard promoter with strengthened variant (PAOXM) [6].

- Signal peptide Engineering: Substitute native signal peptide with optimized sequence (Ost1-αMF) [6].

- Gene Dosage Optimization: Integrate multiple copies of expression cassette (3 copies for cGOD) [6].

- Secretory Pathway Engineering: Co-express key secretory components (e.g., chaperones, vesicle trafficking regulators) [6].

This combined approach increased extracellular glucose oxidase activity to 967 U/mL in shake flasks and 11,655 U/mL in 15L bioreactor cultivation [6].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Heterologous Enzyme Expression

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Hosts | E. coli BL21(DE3), S. cerevisiae INVSc1, K. phaffii X33, A. niger AnN2 | Provide cellular machinery for transcription, translation, and protein processing [1] [6] [4] |

| Expression Vectors | pESC-TRP (S. cerevisiae), pPICZ (K. phaffii), pCI (mammalian) | Carry expression cassettes with promoters, selectable markers, and integration sites [6] [10] [9] |

| Specialized Strains | SHuffle (E. coli), Lemo21(DE3) (E. coli), R24 (HEK293T with calreticulin knockdown) | Enable disulfide bond formation, toxic protein expression, or difficult receptor surface localization [10] [4] |

| Signal Peptides | α-mating factor (S. cerevisiae), Ost1-αMF (K. phaffii), native and evolved variants | Direct protein secretion through recognition by signal recognition particle [6] [9] |

| Promoters | PAOX1 (K. phaffii), PGAP (K. phaffii), PgpdA (A. niger), Tet-on (A. niger) | Regulate transcription initiation strength and inducibility [1] [6] [7] |

| Selection Markers | Antibiotic resistance (bacteria), auxotrophic markers (yeast/fungi), puromycin (mammalian) | Enable selection and maintenance of expression constructs in host cells [1] [10] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the first step when encountering complete failure of heterologous expression?

A: Begin by thoroughly verifying your expression construct through complete sequencing of the expression cassette. Unexpected mutations, incorrect coding sequences, or regulatory element defects are common causes of failure. Additionally, employ sensitive detection methods beyond SDS-PAGE/Coomassie staining, such as Western blotting or enzymatic activity assays, as your protein might be expressed at low but detectable levels [8].

Q2: How can I improve secretion of heterologous enzymes in fungal systems?

A: Implement a multi-pronged approach: (1) Screen multiple signal peptides using high-throughput methods like Gaussia luciferase fusions; (2) Engineer the secretory pathway by overexpressing key components such as COPI vesicle trafficking proteins; (3) Reduce extracellular proteolysis by disrupting major protease genes; (4) Optimize cultivation conditions including pH control and feeding strategies [1] [6] [9].

Q3: What strategies are most effective for expressing disulfide bond-rich enzymes?

A: For prokaryotic expression, use specialized strains like SHuffle E. coli that promote disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm through a more oxidizing environment and co-expression of disulfide bond isomerase DsbC. For eukaryotic expression, leverage the natural secretory pathway in yeast or filamentous fungi where oxidative folding occurs naturally in the endoplasmic reticulum [4].

Q4: How can I address codon bias issues in heterologous expression?

A: Two primary approaches exist: (1) Use host strains supplemented with rare tRNAs (e.g., Rosetta for E. coli); (2) Perform comprehensive codon optimization of the entire coding sequence, replacing rare codons with host-preferred alternatives while considering factors beyond simple frequency, including mRNA secondary structure and translational pausing [8] [4] [5].

Q5: What are the key advantages of Aspergillus systems for industrial enzyme production?

A: Aspergillus species, particularly A. niger, offer exceptional protein secretion capacity (up to 30 g/L for native enzymes), GRAS status, strong synthetic biology tools including CRISPR/Cas9, and the ability to perform eukaryotic post-translational modifications. Recent engineering of chassis strains with reduced background protein secretion further enhances their utility for heterologous enzyme production [1] [7].

Workflow and Pathway Diagrams

Platform Comparison: Key Characteristics of Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Expression Systems

Table 1: Systematic Comparison of Common Heterologous Protein Expression Platforms

| Feature | E. coli (Prokaryotic) | Yeast (e.g., S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris) | Filamentous Fungi (e.g., Aspergillus niger) |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Advantages | Rapid growth, high yield, easy genetic manipulation, low cost [11] [12] | Eukaryotic PTMs, GRAS status, high-density fermentation, good secretion [11] [5] | Extremely high secretion capacity, GRAS status, robust industrial fermentation [11] [13] |

| Key Limitations | Lack of complex PTMs, formation of inclusion bodies, endotoxin production [11] [12] | Hyper-glycosylation (high mannose), lower secretion than fungi, Crabtree effect (S. cerevisiae) [11] [5] | Complex morphology, dense cell walls, high native protease activity [11] [13] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | Limited to none; no glycosylation, disulfide bond formation can be error-prone [11] | N- and O-glycosylation (differs from mammalian), disulfide bond formation, phosphorylation [11] [5] | Glycosylation, disulfide bond formation, but may have fungal-type glycosylation patterns [11] |

| Typical Protein Localization | Intracellular (often as insoluble inclusion bodies), periplasmic, or rarely extracellular [12] | Primarily secreted to the extracellular medium, intracellular [5] | Highly efficient secretion to the extracellular medium [13] |

| Ideal Protein Types | Non-glycosylated proteins, enzymes for industrial use, antibody fragments [12] | Glycosylated proteins, complex eukaryotic proteins, vaccines, therapeutic hormones [11] [5] | Industrial enzymes (e.g., cellulases, amylases), high-volume protein production [13] [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: How do I decide between a prokaryotic and eukaryotic system for my therapeutic enzyme?

The choice hinges primarily on your protein's structural complexity and intended application.

- Choose E. coli if: Your protein is simple, does not require glycosylation for stability or function, and is intended for non-injectable uses (due to potential endotoxin contamination) [11] [12]. It is the fastest and most cost-effective option for research and industrial production of such proteins.

- Choose a Yeast System if: Your protein requires eukaryotic folding, disulfide bond formation, or glycosylation, but mammalian-system cost is prohibitive. Yeasts like P. pastoris offer high-density cultivation and efficient secretion [11] [5]. They are well-suited for vaccines and some therapeutic proteins, though glycosylation must be carefully evaluated.

- Choose Filamentous Fungi like A. niger if: Your primary goal is the high-volume, low-cost production of an industrial enzyme. These systems excel at secreting vast amounts of protein into the culture broth, simplifying downstream processing [13] [12].

FAQ 2: I see no protein expression in my host. What are the first steps to diagnose the problem?

Follow this systematic troubleshooting workflow to identify the issue.

Troubleshooting workflow for failed heterologous protein expression.

Detailed Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify the DNA Construct: Always sequence the entire expression cassette (promoter, gene, terminator) in your vector to ensure no base-pair errors, accidental stop codons, or mutations have been introduced [8].

- Check Transcription Levels: Use sensitive methods like RT-qPCR to confirm that mRNA is being produced from your construct. A lack of mRNA points to a problem with the promoter or transcription initiation [14].

- Confirm Translation and Protein Location:

- Assay: Use a Western blot instead of relying solely on SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining, as it is far more sensitive and specific [8].

- Location: Perform cell fractionation. After lysing the cells, centrifuge the lysate. The supernatant contains soluble protein, while the pellet contains insoluble aggregates (inclusion bodies). The presence of your protein in the pellet indicates a folding problem [8].

- Address Insoluble Expression: If your protein is in inclusion bodies, you can either:

- Refold the protein in vitro after denaturing and purifying the aggregates.

- Promote soluble expression in vivo by slowing down the production rate. Lower the growth temperature (e.g., to 25-30°C) or reduce the concentration of the inducer (e.g., IPTG) [8]. This gives the cellular machinery more time to fold the protein correctly.

- Optimize the System:

- Try a Different Promoter: Secondary structures in the mRNA can hinder translation; switching promoters can resolve this [8].

- Co-express Chaperones: Overexpress host chaperone proteins (e.g., GroEL/GroES in E. coli) to assist with the folding of complex heterologous proteins [8].

- Fix Codon Usage: Check the codon adaptation index (CAI) of your gene. Replace codons that are rare in your expression host with more frequent synonyms, either via whole-gene synthesis or by using host strains engineered to supply rare tRNAs (e.g., E. coli Rosetta strains) [14] [8] [5].

FAQ 3: My protein is expressed but is inactive. What could be wrong?

Inactive protein often points to problems with folding or post-translational modifications.

- Misfolding and Inclusion Bodies: This is the most common cause in E. coli. Follow the steps in FAQ 2 to check for and mitigate insoluble expression [8] [12].

- Lack of Essential PTMs: If your enzyme requires specific glycosylation, disulfide bonds, or phosphorylation for activity, a prokaryotic host like E. coli will be incapable of producing the active form. In this case, switching to a eukaryotic host (yeast, fungi) is necessary [11].

- Incorrect Disulfide Bond Formation: In E. coli, use engineered strains like Origami that enhance disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm by mutations in the thioredoxin and glutathione reductase pathways [8].

- Protein Truncation: For large, multi-domain proteins like cellulases, proteolytic cleavage can occur in the linker regions between domains, leading to loss of function. Using protease-deficient host strains and checking the full-length integrity of your protein on a Western blot can diagnose this issue [12].

Advanced Methodologies for Enhanced Expression

Experimental Protocol: Codon Optimization and Evaluation

Codon optimization is a critical first step to ensure efficient translation. The following protocol, adapted from studies on polyketide synthase expression, provides a robust methodology [14].

Objective: To design, synthesize, and evaluate codon-optimized gene variants for improved heterologous protein expression.

Materials:

- DNA Synthesis Services or site-directed mutagenesis kit for gene synthesis.

- Expression Vectors suitable for your target host (E. coli, yeast, etc.).

- Host Strains: Standard expression strain (e.g., E. coli BL21) and specialized strains if needed (e.g., Rosetta for rare tRNAs).

- Equipment: PCR machine, gel electrophoresis, Western blot apparatus, and spectrophotometer.

Methodology:

- Codon Variant Design: Use computational tools to generate several codon-optimized versions of your target gene. Key strategies include:

- Use Best Codon (UBC): Replaces all codons with the single most frequent codon for each amino acid in the host.

- Match Codon Usage (MCU): Designs a sequence where the frequency of codons matches the overall codon usage table of the host.

- Codon Harmonization (HRCA): Attempts to match the codon usage frequency of the native host of the gene with that of the expression host, potentially preserving natural translation kinetics [14].

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize the native and optimized gene variants and clone them into your expression vector, ensuring all other elements (promoter, RBS, terminator) are identical.

- Host Transformation: Transform the constructs into your selected expression host.

- Expression Analysis:

- Transcript Level: Use RT-qPCR to measure mRNA levels. This confirms that optimization did not negatively impact transcription.

- Protein Level: Use SDS-PAGE and quantitative Western blotting to compare protein expression yields between variants.

- Functional Assay: Perform an enzyme activity assay to confirm the optimized protein is not only expressed but also functional [14].

Advanced Strategy: Combinatorial Optimization of Expression Elements

For multi-gene pathways or to fine-tune expression without a priori knowledge, combinatorial methods are highly effective. The GEMbLeR (Gene Expression Modification by LoxPsym-Cre Recombination) system in yeast is a state-of-the-art example [15].

Principle: This technology uses the Cre recombinase to shuffle predefined promoter and terminator modules that are flanked by orthogonal LoxPsym sites and integrated at the genomic locus of each pathway gene.

Workflow:

- Strain Construction: Replace the native promoter and terminator of your target gene(s) with a "GEM" module containing multiple different promoter/terminator sequences separated by LoxPsym sites.

- Library Generation: Induce the expression of Cre recombinase in the population. This causes stochastic inversion, excision, and duplication events within the GEM modules, creating a vast library of strains where each member has a unique combination of promoter and terminator strengths for the target genes.

- High-Throughput Screening: Screen this library for your desired phenotype, such as high production of a fluorescent reporter or a valuable compound like astaxanthin. A single round of GEMbLeR has been shown to more than double production titers [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents for Troubleshooting Heterologous Expression

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Host Strains | Engineered to overcome specific expression hurdles. | E. coli Rosetta: Supplies rare tRNAs for codons poorly represented in E. coli [8]. E. coli Origami: Promotes disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm [8]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Co-expression of folding assistants to improve solubility. | Takara's Chaperone Plasmid Set; co-expression of GroEL/GroES to prevent aggregation of complex proteins [8]. |

| Fusion Tags | Enhance solubility and simplify purification. | MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein), Trx (Thioredoxin); fused to the N- or C-terminus of target proteins to drive soluble expression [8]. |

| Codon Optimization Software | In silico design of optimized gene sequences for a chosen host. | BaseBuddy: A free online tool that offers customizable codon optimization with up-to-date usage tables [14]. DNA Chisel: An open-source Python toolkit for flexible codon optimization strategies [14]. |

| Alternative Inducers | Fine-tune expression kinetics to reduce metabolic burden. | Molecula's Inducer: An IPTG alternative reported to allow for slower, more controlled induction, potentially improving folding [8]. |

Quantitative Data on Production Bottlenecks

The table below summarizes key bottlenecks and their quantitative impact on recombinant protein production, as identified in recent studies.

| Bottleneck Category | Specific Factor | Quantitative Impact / Correlation | Experimental System | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transcriptional / mRNA | Transgene mRNA Abundance | Explains <1% of variance in secretion titer [16] | CHO cells expressing 2135 human secretome proteins [16] | [16] |

| Protein-Specific Features | Molecular Weight (MW) | Ranked as the most important predictor in ML models [16] | CHO cells; analysis of 218 protein features [16] | [16] |

| Protein-Specific Features | Cysteine Composition & Disulfide Bonds | Among top 10 most important predictors in all models [16] | CHO cells; analysis of 218 protein features [16] | [16] |

| Protein-Specific Features | N-linked Glycosylation | A key predictor of secretion variability [16] | CHO cells; analysis of 218 protein features [16] | [16] |

| Host Cell Physiology | Ubiquitin-Proteasome & ER-Associated Degradation (ERAD) | Pathway enriched in low-producing cells [16] | RNA-Seq of 95 CHO cultures [16] | [16] |

| Host Cell Physiology | Lipid Metabolism & Oxidative Stress Response | Pathways upregulated in high-producing cells [16] | RNA-Seq of 95 CHO cultures [16] | [16] |

| Secretion Pathway | Vesicle Trafficking (COPI component Cvc2) | Overexpression enhanced pectate lyase (MtPlyA) production by 18% [1] | Aspergillus niger chassis strain [1] | [1] |

| Overall Model | Combination of 218 Protein Features | Account for ~15% of secretion variability [16] | Machine learning analysis on CHO cell data [16] | [16] |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Combinatorial Strategy for Enhancing GOD Expression inKomagataella phaffii

This protocol outlines a multi-pronged approach that significantly boosted glucose oxidase (GOD) production [6].

- Gene Identification and Cloning: Identify the gene of interest (e.g., the cGOD gene from Aspergillus cristatus). Clone the gene into an expression vector for K. phaffii [6].

- Expression Cassette Optimization:

- Promoter Enhancement: Replace the standard alcohol oxidase promoter (PAOX1) with a stronger, modified version (PAOXM).

- Signal Peptide Engineering: Substitute the native signal peptide with a more efficient one (e.g., the Ost1 pre-region fused to the α-mating factor pro-region).

- Gene Copy Number Amplification: Generate strains with multiple integrated copies of the optimized expression cassette [6].

- Secretory Pathway Engineering: Co-express key components of the secretory pathway, such as the translation factor eIF4G and the transcription factor HAC1, to alleviate endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and enhance protein folding capacity [6].

- Bioreactor Scale-Up:

- Shake Flask Culture: Initially cultivate the engineered strain in shake flasks to assess expression. The described protocol achieved 967 U/mL of extracellular cGOD activity at this stage.

- High-Density Fermentation: Transfer the production to a controlled fed-batch fermenter (e.g., 15 L scale). Under optimized conditions, the protocol achieved a final enzyme activity of 11,655 U/mL [6].

Protocol 2: Construction of a High-YieldingAspergillus nigerChassis Strain

This protocol uses CRISPR/Cas9 to create a cleaner genetic background for heterologous protein expression in the filamentous fungus A. niger [1].

- Parent Strain Selection: Start with an industrial production strain (e.g., AnN1) with a known, robust secretion machinery [1].

- CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Gene Deletion:

- Targeting High-Copy Native Genes: Design gRNAs to target and delete multiple copies of a highly expressed native gene (e.g., 13 out of 20 copies of the TeGlaA glucoamylase gene). This reduces background protein secretion.

- Protease Gene Disruption: Simultaneously disrupt a gene encoding a major extracellular protease (PepA) to minimize degradation of the heterologous protein [1].

- Validation of Chassis Strain (AnN2): Characterize the resulting strain. The protocol reported a 61% reduction in total extracellular protein and significantly reduced glucoamylase activity, confirming a cleaner background [1].

- Site-Specific Gene Integration: Integrate the target heterologous gene (e.g., a glucose oxidase AnGoxM or a pectate lyase MtPlyA) into the high-expression loci previously occupied by the deleted native genes. This yielded target protein levels ranging from 110.8 to 416.8 mg/L in shake-flask cultures [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My recombinant protein is being expressed in E. coli but is entirely insoluble. What are my primary strategies to improve solubility?

- A1: Insolubility often leads to inclusion body formation. You can:

- Reduce Expression Temperature: Lower the induction temperature (e.g., to 25-30°C) to slow down protein synthesis and favor correct folding [17].

- Use Fusion Tags: Utilize tags like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) or Thioredoxin (Trx) that enhance solubility [17].

- Switch Expression Systems: If the protein requires complex folding or post-translational modifications, consider switching to a eukaryotic system like yeast or mammalian cells [17].

- Employ Solubility-Enhancing Strains: Use engineered E. coli strains that express molecular chaperones (e.g., GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ) to assist with folding [18].

Q2: I have confirmed high mRNA levels for my transgene, but the final protein titer is still low. What could be the issue?

- A2: This is a common bottleneck. Recent research in CHO cells shows that mRNA abundance can explain less than 1% of the variation in secreted protein titer, indicating post-transcriptional limitations [16]. Your issue likely lies in:

- Inefficient Secretion: The protein may be misfolded, leading to degradation via the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. This pathway is often enriched in low-producing cells [16].

- Protein-Specific Features: Intrinsic properties of your protein, such as high molecular weight, high cysteine content (requiring disulfide bonds), or complex glycosylation patterns, can severely limit secretion efficiency [16].

- Host Cell Physiology: Engineering the host to upregulate beneficial pathways like lipid metabolism and oxidative stress response has been correlated with high production [16].

Q3: How can I choose the best signal peptide for secreting my recombinant protein in a bacterial system?

- A3: There is no universal signal peptide. The optimal choice depends on the target protein and the bacterial host [19]. The most effective approach is empirical screening:

- Library Screening: Screen a diverse library of signal peptides (e.g., both Sec and Tat pathway-specific peptides) fused to your protein of interest [19].

- Bioinformatic Prediction: Use prediction tools like SignalP or Phobius to identify potential native signal peptides or to guide library design [19].

- Optimization: The signal peptide can be further optimized via site-directed or random mutagenesis to improve its performance in your specific context [19].

Q4: My purified recombinant protein is unstable and loses activity quickly. How can I improve its stability?

- A4: Protein instability can be addressed by:

- Optimizing Storage Conditions: Store the protein at low temperatures (-80°C) in stabilizing buffers. Add stabilizing agents like glycerol, sucrose, or certain salts. Always include protease inhibitors in lysis and storage buffers to prevent degradation [17].

- Controlling pH and Ionic Strength: The buffer's pH and salt concentration can profoundly impact stability. Test a range of conditions to find the optimal one [17].

- Utilizing Fusion Proteins: Certain tags, besides aiding purification, can also enhance the stability of the fused protein [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists essential tools and reagents used in the featured experiments for optimizing recombinant protein production.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 System | A genome editing tool that allows for precise deletion or insertion of genes. | Engineering chassis strains by deleting native protease genes or integrating heterologous genes into high-expression loci [1]. |

| Signal Peptide Library | A collection of different Sec- or Tat-specific signal peptides for empirical testing. | Screening for the most efficient signal peptide to secrete a specific target protein in a chosen bacterial host [19]. |

| Chaperone Co-expression Plasmids | Plasmids encoding protein-folding assistants like GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ. | Improving the solubility and correct folding of recombinant proteins expressed in E. coli [18]. |

| Secretory Pathway Factors (e.g., HAC1, eIF4G) | Genes involved in the unfolded protein response (UPR) and vesicle trafficking. | Co-expression to expand ER folding capacity and enhance secretion efficiency in eukaryotic hosts like yeast [6]. |

| Affinity Purification Tags (His-tag, GST-tag) | Short amino acid sequences fused to the protein for purification using chromatography. | Enabling one-step purification of the recombinant protein from complex cell lysates [17]. |

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Protein Secretory Pathway in Eukaryotic Cells

Experimental Workflow for Strain Improvement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My target protein is not expressing, or the yield is very low. What could be the general causes? Low or absent expression is a common hurdle in heterologous expression. The causes can be broadly categorized into issues with the host cell's genetic machinery and problems related to the inherent properties of the target protein itself. Genetic instability of the plasmid or target gene can prevent expression, while the toxicity of the protein to the host, such as the formation of toxic oligomers or disruption of membrane integrity, can inhibit cell growth and protein production [20] [21]. Furthermore, improper protein folding and aggregation into insoluble inclusion bodies is a frequent cause of low yield of functional protein [22].

Q2: What specific genetic mutations can cause protein aggregation and toxicity?

Recent research has identified specific genetic mutations that lead to the production of toxic, aggregation-prone proteins. For instance, a novel genetic mutation in the CASP8 gene, characterized by a GGGAGA repeat expansion, was found to produce toxic proteins with long chains of glycine and arginine (polyGR) [23]. These toxic proteins were present in over 50% of the Alzheimer's disease brains studied and are distinct from the well-known amyloid-beta and tau pathologies. Carriers of this mutation have a 2.2-fold increased risk of developing late-onset Alzheimer's [23].

Q3: How can I optimize membrane protein production in a yeast expression system? Membrane proteins are notoriously difficult to produce. A key strategy is the careful titration of the promoter strength. A 2025 study demonstrated that using very low concentrations of the inducer galactose (e.g., 0.003% for UCP1, 300 times lower than usual) in the S. cerevisiae GAL10 promoter system dramatically increased the solubilization efficiency of recombinant membrane proteins from yeast membranes [24]. This approach reduces the metabolic burden and toxicity associated with overexpression, suppressing the formation of aggregates and facilitating subsequent purification steps [24].

Q4: How does general cellular stress contribute to expression failure? Cellular stress can exacerbate the production of toxic proteins. Studies on repeat expansion disorders, which share features with protein aggregation diseases, have shown that various types of stress can increase the production of aberrant proteins [23]. Furthermore, when a cell's quality control systems, like the proteasome or chaperone networks, are overwhelmed by misfolded or aggregated proteins, it leads to a failure in maintaining protein homeostasis, further compounding expression problems and potentially leading to cell death [20].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Low Solubility of Recombinant Membrane Proteins

Problem: The target membrane protein is expressed but is largely insoluble and cannot be effectively extracted from the membrane fraction for purification.

Solution: Implement a promoter titration strategy to fine-tune expression levels, preventing overload and aggregation.

Experimental Protocol (Based on Yeast Expression System) [24]:

- Vector and Host: Use an expression plasmid with a galactose-inducible promoter (e.g., GAL10-CYC1) and a compatible Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain.

- Culture and Induction:

- Grow the culture in a suitable medium (e.g., S-lactate medium) to the desired OD~600~.

- Instead of using a standard, high concentration of galactose (e.g., 1-2%), test a range of very low concentrations (e.g., from 0.001% to 0.05%).

- Induce expression for a defined period (e.g., 4-16 hours).

- Membrane Preparation and Solubilization:

- Harvest cells and isolate the crude mitochondrial/membrane fraction.

- Solubilize the membrane proteins using a mild detergent (e.g., DDM, LMNG) at a defined detergent-to-protein ratio (e.g., 10:1 w:w).

- Centrifuge to separate the solubilized fraction (supernatant) from the insoluble pellet.

- Analysis: Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting to determine the proportion of the target protein that has been successfully solubilized.

Expected Outcome: The following table summarizes the quantitative improvements in solubilization efficiency achievable through promoter titration, as demonstrated for the mitochondrial uncoupling protein UCP1 [24]:

Table 1: Effect of Galactose Induction Concentration on UCP1 Solubilization

| Galactose Concentration | UCP1 Production Level | Solubilization Efficiency with DDM | Key Observation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1% (Standard) | High | ~3% | Protein forms aggregates; poor extraction. |

| 0.05% | High | Enhanced (vs. 1%) | Improved extraction with multiple detergents. |

| 0.003% (Optimal) | Moderate | 70% (Maximum threshold) | Optimal for homogenous, active protein purification. |

Guide 2: Mitigating Cellular Toxicity from Protein Aggregates

Problem: Expression of the target protein causes severe cellular toxicity, leading to poor cell growth or death, resulting in no yield.

Solution: Utilize fusion tags that enhance secretion and consider the specific toxic mechanisms of protein aggregates.

Experimental Protocol (Secretion Expression in E. coli) [21]:

- Construct Design: Fuse the gene of your target protein (e.g., a lipolytic enzyme) to a mediator protein known to facilitate secretion, such as the fast-folding fluorescent protein mScarlet3. The fusion can be at either the N- or C-terminus.

- Transformation and Expression:

- Transform the construct into an appropriate E. coli host (e.g., BL21(DE3)).

- Grow the culture and induce with a low concentration of IPTG (e.g., 0.5 mM) at a lower temperature (e.g., 18°C) for an extended period (e.g., 24 h).

- Protein Recovery: Collect the culture medium (extracellular fraction) and the cell pellet separately. Analyze both to confirm secretion of the fusion protein.

- Mechanism Insight: Understand that toxicity often comes from soluble oligomers or "protofibrils" rather than mature fibrils [20]. These prefibrillar aggregates can disrupt cell membranes, inactivate essential proteins, and overwhelm the cellular quality control systems [20]. Secretion bypasses intracellular accumulation and its associated toxicity.

Expected Outcome: The fusion strategy can significantly reduce intracellular toxicity by directing the protein out of the cell. For example, the mScarlet3-LipHu6 fusion achieved a specific activity of 669,151.75 U/mmol, successfully mitigating the toxicity associated with intracellular production [21].

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Signaling Pathway of DNA Bridge-Induced Genetic Instability

The following diagram illustrates the molecular mechanism by which persistent DNA bridges during cell division lead to genetic instability, a process relevant to understanding cellular stress responses during recombinant expression.

Diagram: DNA Bridge Resolution Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Optimizing Membrane Protein Expression

This workflow outlines the step-by-step protocol for using promoter titration to achieve high yields of soluble, functional membrane proteins.

Diagram: Membrane Protein Optimization Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Heterologous Expression Optimization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| S. cerevisiae GAL10-CYC Promoter | A strong, inducible promoter system for controlled protein expression in yeast. | Titrating expression levels of membrane proteins like UCP1 to maximize solubilization yield [24]. |

| mScarlet3 Fluorescent Protein | A fast-folding, monomeric red fluorescent protein used as a fusion tag to mediate secretion. | Facilitating the secretion of toxic proteins (e.g., lipase LipHu6) in E. coli to reduce intracellular toxicity and simplify purification [21]. |

| Mild Detergents (DDM, LMNG) | Amphipathic molecules used to solubilize and extract membrane proteins from lipid bilayers while preserving their native structure. | Solubilizing functional mitochondrial uncoupling protein (UCP1) from yeast membranes for purification and reconstitution [24]. |

| Micro-HEP Platform | A microbial heterologous expression platform using engineered E. coli and Streptomyces for efficient expression of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs). | Heterologous production of natural products like xiamenmycin and griseorhodins by integrating multiple copies of their BGCs into a optimized chassis strain [25]. |

| Redα/Redβ/Redγ Recombineering System | A λ phage-derived system that enables highly efficient genetic modifications in E. coli using short homology arms. | Cloning and modifying large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) within the Micro-HEP platform prior to conjugative transfer [25]. |

Recent Advances in Synthetic Biology and Genetic Tool Development

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs for Heterologous Enzyme Expression

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

This section addresses frequent challenges in heterologous enzyme expression experiments, offering targeted solutions to improve your research outcomes.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Cloning and Transformation Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Few or no transformants [26] | Cells are not viable | Transform an uncut plasmid to check viability; use high-efficiency commercially available competent cells if needed. [26] |

| DNA fragment is toxic to cells | Incubate plates at a lower temperature (25–30°C); use a strain with tighter transcriptional control (e.g., NEB 5-alpha F´ Iq). [26] | |

| Construct is too large | Use competent cell strains designed for large constructs (e.g., NEB 10-beta); for very large constructs (>10 kb), use electroporation. [26] | |

| Inefficient ligation | Ensure one fragment has a 5´ phosphate; vary vector-to-insert molar ratio (1:1 to 1:10); use fresh ligation buffer (ATP degrades); clean up DNA to remove contaminants. [26] | |

| Colonies contain the wrong construct [26] | Recombination of the plasmid | Use a recA– strain such as NEB 5-alpha or NEB 10-beta. [26] |

| Internal restriction site present | Analyze the insert sequence for internal recognition sites using a tool like NEBcutter. [26] | |

| DNA fragment is toxic | Incubate at lower temperatures; use a tightly controlled expression strain. [26] | |

| No PCR product or low yield [27] | Poor template integrity/quantity | Evaluate template integrity by gel; increase template amount; use a polymerase with high sensitivity. [27] |

| Complex targets (GC-rich) | Use a polymerase with high processivity; add PCR co-solvents (e.g., DMSO); increase denaturation time/temperature. [27] | |

| Suboptimal primer design/annealing | Review primer design for specificity; optimize annealing temperature in 1–2°C increments. [27] | |

| Non-specific PCR amplification [27] | Excess DNA template/polymerase | Lower the quantity of input DNA; review and decrease the amount of polymerase used. [27] |

| Low annealing temperature | Increase the annealing temperature; use a hot-start DNA polymerase to improve specificity. [27] | |

| Excess Mg2+ concentration | Review and lower the Mg2+ concentration to prevent nonspecific products. [27] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Protein Expression Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low expression yield [28] | Inefficient translation or protein folding | Optimize codon usage to match the host organism; use strategic host strain engineering (e.g., E. coli, B. subtilis, P. pastoris). [28] |

| Metabolic burden on host cells | Engineer host metabolism to reduce burden; use inducible promoters for tighter control. [28] | |

| Suboptimal experimental design | Utilize AI tools like CRISPR-GPT to analyze data, predict pitfalls, and optimize design. [29] | |

| Enzyme inactivity [28] | Improper folding or inclusion body formation | Explore different host systems (e.g., P. pastoris for eukaryotic proteins); use molecular chaperones to aid folding. [28] |

| Lack of essential post-translational modifications | Choose a host system compatible with the enzyme's native requirements (e.g., yeast for glycosylation). [28] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What recent advances can help me design better heterologous expression experiments? A1: Artificial intelligence is now a powerful co-pilot for experimental design. Tools like CRISPR-GPT can help you generate designs, analyze data, and troubleshoot flaws by leveraging years of published scientific data. It can predict off-target effects and suggest robust experimental approaches, significantly flattening the learning curve, especially for complex systems [29]. Furthermore, new precision gene-editing tools like MIT's engineered prime editors (vPE) drastically reduce errors during genetic modifications, which is crucial for creating stable production strains [30].

Q2: How can I control the expression of my gene of interest with high precision? A2: Beyond traditional inducible promoters, new "gene-switch" technologies offer refined control. The recently developed Cyclone system allows you to turn a target gene on or off using the non-toxic antiviral drug acyclovir. This tool is highly versatile, can dial activity from 0% to over 300% of normal levels, and leaves RNA and protein products intact, making it ideal for both research and future therapeutic applications [31].

Q3: What are the key molecular strategies for optimizing heterologous enzyme production? A3: Successful optimization often involves a multi-faceted approach [28]:

- Transcriptional Regulation: Use synthetic promoters and engineering transcription factors to boost mRNA levels.

- Codon Optimization: Tailor the gene's codon usage to your specific host organism (e.g., E. coli, P. pastoris) for efficient translation.

- Host Strain Engineering: Genetically modify the host to improve protein folding, reduce metabolic burden, and eliminate protease activity.

- In silico Design: Use computational tools for rational design before moving to the lab.

Q4: My cloning efficiency is low. What are the critical controls I should run? A4: Running the right controls is essential for diagnosing the problem [26]:

- Uncut vector: Checks cell viability and transformation efficiency.

- Cut vector: Determines background from undigested plasmid (should be <1% of control #1).

- Vector-only ligation: Should yield few colonies, confirming the vector cannot re-ligate.

- Single-enzyme digest & re-ligation: The ends should be compatible and re-ligate efficiently, resulting in many colonies.

Experimental Protocols for Advanced Genetic Engineering

Protocol 1: Utilizing an AI Assistant for CRISPR Experiment Design

This protocol outlines how to use AI tools, such as CRISPR-GPT, to plan gene-editing experiments for metabolic engineering in heterologous hosts [29].

- Initiate Conversation: Access the AI agent through its text interface.

- Define Goal: Provide your experimental objective (e.g., "I plan to knockout gene X in E. coli to improve precursor flux for L-ASNase production").

- Input Context: Include relevant information such as the host organism, target gene sequence, and desired outcome.

- Receive Design: The AI will generate a step-by-step experimental plan, suggesting guide RNAs, Cas9 variants, and donor DNA templates if needed.

- Troubleshoot: The AI will highlight potential problems encountered in similar past experiments and suggest optimizations for efficiency and specificity.

- Execute and Validate: Follow the designed protocol and validate edits via sequencing and functional assays.

Protocol 2: Implementing High-Fidelity Prime Editing with vPE

This protocol uses the vPE system for introducing precise, low-error mutations to optimize enzyme sequences in heterologous hosts [30].

- Design Prime Editing Guide RNA (pegRNA): Design the pegRNA to contain the desired edit and a primer binding site.

- Assemble vPE Complex: The vPE system uses a mutated Cas9 protein (with high-fidelity mutations) complexed with the pegRNA and an engineered reverse transcriptase.

- Deliver to Cells: Deliver the vPE machinery into your host cells (e.g., via electroporation or transfection).

- Editing Reaction: The vPE system nicks the target DNA strand and uses the pegRNA as a template for reverse transcription, writing the new sequence into the genome.

- Validate Editing: Screen clones and sequence the target locus to confirm the precise edit and assess the low off-target rate.

The workflow for this advanced gene-editing protocol is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Synthetic Biology Workflows

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [27] | Reduces errors during PCR amplification, crucial for downstream cloning and sequencing. | Amplifying enzyme genes for cloning with high sequence fidelity. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase [27] | Prevents non-specific amplification and primer-dimer formation by requiring heat activation. | Improving specificity and yield in PCR for gene construction. |

| Monarch Spin PCR & DNA Cleanup Kit [26] | Purifies DNA to remove contaminants like salts, EDTA, or enzymes that inhibit downstream steps. | Cleaning up restriction digests or ligation reactions before transformation. |

| Competent E. coli Strains [26] | Specialized strains for different needs: recA- (reduce recombination), McrA-/McrBC- (for methylated DNA), high-efficiency (for large constructs). | Stable propagation of plasmids containing toxic genes or large inserts. |

| T4 DNA Ligase [26] | Joins DNA fragments by catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation. | Ligation of inserts into plasmid vectors during clone construction. |

| BioXp System / Gibson Assembly [32] | Automated synthetic biology workstation and related method for seamless DNA assembly. | Rapid assembly of multiple DNA fragments, such as metabolic pathways, without reliance on restriction sites. |

Genetic Engineering and Host System Optimization Techniques

Promoter Engineering and Transcriptial Regulation Strategies

Foundational Concepts: Promoters and Transcriptional Regulation

What are the core components of a promoter, and how do they influence gene expression?

Promoters are DNA sequences located upstream of gene coding regions that control both the initiation and intensity of transcription. In eukaryotic systems like Saccharomyces cerevisiae, promoters consist of two primary components:

Regulatory Components: These include upstream activating sequences (UAS) or upstream repressing sequences (URS), typically located 100-1400 bp upstream of the core promoter. These regions contain transcription factor binding sites (TFBS) that activate or inhibit transcription by binding specific transcription factors (TFs). Changes in the number and location of these regulatory components significantly affect gene expression levels [33].

Core Components: This is the minimal region required to initiate transcription, determining both the direction and start site of transcription. Approximately 20% of S. cerevisiae core promoters contain a TATA box located 40-120 bp upstream of the transcription start site (TSS). The TATA box serves as the binding site for TATA-binding protein (TBP), representing the first step for RNA polymerase II to initiate transcription. The sequence around the TSS, sometimes called the initiator (INR), also plays a prominent role in transcription initiation, particularly for promoters lacking a TATA box [33].

How do transcription factors regulate gene expression?

Transcription factors (TFs) are proteins that control gene expression by binding to specific DNA sequences (TFBS) and regulating transcriptional activity. Most TFs contain at least two core structural domains:

DNA Binding Domain (DBD): Responsible for specifically recognizing and binding to TFBS, often containing structural motifs like helix-turn-helix (HTH), helix-loop-helix, zinc finger, or leucine zipper [34].

Effector Domain (ED): Serves as the regulatory domain involved in signal sensing, capable of binding various intracellular metabolites (CoA, NADPH, pyruvate, etc.) or responding to external environmental changes (pH, temperature, light, dissolved gases) [34].

TFs regulate transcription through several mechanisms. Activating TFs may recruit RNA polymerase to promoters or improve the spatial conformational adaptation of promoter DNA to RNA polymerase. Repressing TFs may block RNA polymerase access or recruit repressive complexes. The binding or dissociation of TFs to DNA is often triggered by specific effector molecules or environmental signals [34].

Troubleshooting Guides for Common Experimental Challenges

Problem: Low Heterologous Protein Expression

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Strategies to Enhance Heterologous Protein Expression

| Problem Area | Potential Solution | Specific Approach | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transcription Level | Promoter Engineering | Use strong constitutive promoters (pTDH3, pPGK1, pADH1 in yeast; T7, tac in E. coli) or inducible systems | Increase transcription initiation and mRNA yield [33] [35] |

| Increase Gene Copy Number | Use high-copy number plasmids (YEp in yeast) or genomic integration at multiple loci | Higher gene dosage and potentially increased expression [5] | |

| Translation Level | Codon Optimization | Replace rare codons with host-preferred synonyms; optimize GC content; avoid base repeats | Improved translation efficiency and accuracy [5] |

| tRNA Supplementation | Use expression strains supplemented with rare tRNAs | Overcome codon bias in heterologous genes [36] | |

| Protein Stability | Fusion Tags | Utilize solubility-enhancing tags (maltose-binding protein, glutathione-S-transferase) | Improved folding characteristics and reduced proteolysis [35] [36] |

| Compartment Targeting | Target proteins to periplasm (E. coli) or use secretory pathways (yeast) | Enhanced disulfide bond formation and reduced degradation [35] |

Experimental Protocol: Codon Optimization

- Analyze the codon adaptation index (CAI) of your heterologous gene using online tools

- Identify rare codons (those with frequency <10% in your host organism)

- Replace rare codons with preferred synonyms while maintaining amino acid sequence

- Avoid creating secondary mRNA structures that might impede translation

- Synthesize the optimized gene and clone into your expression vector

- Validate expression compared to non-optimized control [5]

Problem: Metabolic Burden and Cellular Toxicity

Potential Causes and Solutions:

Table: Strategies to Reduce Metabolic Burden

| Strategy | Methodology | Applicable Hosts | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Inducible Systems | Use regulated promoters (e.g., tetR, PBAD, alcohol-oxidase) | All microbial hosts | Timing and concentration of inducer critical [37] |

| Dynamic Regulation | Implement feedback-regulated systems | Yeast, E. coli, methylotrophs | Requires understanding of metabolic pathways [34] |

| Genomic Integration | Replace plasmid-based systems with chromosomal integration | Yeast, specialized bacteria | Lower copy number but improved stability [5] |

| Pathway Balancing | Use promoters of different strengths for various pathway genes | All engineered hosts | Requires systematic optimization [33] |

Experimental Protocol: Dynamic Regulation Using TF-Based Systems

- Identify a transcription factor responsive to your metabolic of interest

- Characterize the TF binding sites and regulated promoters

- Engineer synthetic promoters containing relevant TFBS

- Construct circuits where toxic pathway expression is downregulated by metabolic sensors

- Validate dynamic control in bioreactor studies [34]

Problem: Inefficient Protein Secretion

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Signal Sequence Issues: Test different native and heterologous signal sequences (e.g., α-mating factor in yeast, PelB or OmpA in E. coli)

- Secretory Pathway Capacity: Co-express chaperones (BiP, PDI in eukaryotes; Skp, FkpA in bacteria) to assist folding

- Proteolytic Degradation: Use protease-deficient strains (e.g., BL21 for E. coli; S. cerevisiae pep4 mutant)

- Cellular Stress: Reduce expression temperature (15-25°C) to slow processes and improve folding [5] [36]

Experimental Protocol: Signal Sequence Screening

- Clone your target gene with 3-5 different signal sequences

- Transform into appropriate host strain

- Conduct small-scale expression cultures

- Measure protein levels in both cell lysate and culture supernatant

- Select the most efficient signal sequence for scale-up [5]

Advanced Engineering Strategies

Promoter Engineering Techniques

Table: Promoter Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Expression

| Strategy | Methodology | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hybrid Promoters | Combine regulatory elements from different natural promoters | Create novel expression characteristics | May require extensive screening [33] |

| Mutation Libraries | Error-prone PCR or synthetic promoter generation | Generate promoters with varied strengths | High-throughput screening needed [37] |

| TFBS Engineering | Modify type, number, or arrangement of TFBS | Fine-tune regulation patterns | Requires detailed TF characterization [34] |

| Synthetic Systems | Implement orthogonal regulatory circuits | Reduce host interference | Increased genetic complexity [38] |

Host-Specific Considerations

Different expression hosts present unique advantages and challenges for heterologous protein expression:

S. cerevisiae:

- Advantages: GRAS status, eukaryotic protein processing, well-characterized genetics

- Strong constitutive promoters: pTDH3, pPGK1, pADH1, pTEF1 [33] [5]

- Inducible systems: GAL1/10 (galactose), MET25 (methionine), CUP1 (copper)

E. coli:

- Advantages: Rapid growth, high yields, extensive toolkit

- Strong promoters: T7, tac, trc, araBAD [35]

- Optimization strategies: Codon usage, fusion tags, compartment targeting [39] [35]

Methylotrophic Yeasts (P. pastoris):

- Advantages: Strong inducible promoters, high density cultivation

- Key promoters: PAOX1 (methanol-inducible), PGAP (constitutive) [37]

Filamentous Fungi (T. reesei):

- Advantages: Exceptional protein secretion capacity

- Engineered promoters: Pcbh1 with repressor replacement [38]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Promoter Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET (E. coli), pRS (yeast), pPIC (P. pastoris) | Backbone for gene expression with selectable markers [35] |

| Promoter Libraries | Constitutive and inducible promoter sets | Screening optimal expression conditions [33] [37] |

| Transcription Factor Tools | TF expression plasmids, reporter constructs | Characterizing TF-DNA interactions [34] |

| Codon Optimization Services | Gene synthesis with host-specific codon bias | Improving translation efficiency [5] |

| Protease-Deficient Strains | E. coli BL21, S. cerevisiae pep4Δ | Reducing target protein degradation [36] |

| Chaperone Plasmids | GroEL/S, DnaK/DnaJ, BiP/PDI co-expression | Enhancing proper protein folding [35] |

| Secretion Enhancers | Signal sequence libraries, secretory pathway components | Improving protein translocation [5] |

Visual Guide: Promoter Engineering Workflow

Promoter Engineering Decision Workflow

Visual Guide: Transcription Factor Mechanism

Transcription Factor Regulatory Mechanism

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I choose between constitutive and inducible promoters for my application?

The choice depends on your specific needs. Use constitutive promoters (pGAP, pTEF1, pTDH3) when continuous expression is desired and the protein isn't toxic to the host. Choose inducible systems (GAL, AOX, tet) when:

- The expressed protein is toxic to the host

- You need to separate growth and production phases

- You require precise temporal control over expression [33] [37]

Q2: What are the most effective strategies for optimizing promoter strength?

Systematic approaches work best:

- Start with native promoter characterization

- Create hybrid promoters by combining strong UAS elements with core promoters

- Use mutagenesis (error-prone PCR) to generate variant libraries

- Implement high-throughput screening (FACS, microtiter plates)

- Validate top performers in bioreactor conditions [33] [37]

Q3: How can I reduce metabolic burden in high-expression systems?

- Use genomic integration instead of high-copy plasmids

- Implement dynamic regulation that ties expression to growth phase

- Balance pathway expression using promoters of different strengths

- Optimize induction timing and concentration

- Use nutrient-limited feeding strategies in fermentation [34] [5]

Q4: What host system is most suitable for complex eukaryotic proteins?

S. cerevisiae often works well for complex eukaryotic proteins because it provides:

- Eukaryotic protein folding machinery

- Post-translational modifications

- Secretion capability

- GRAS status for therapeutic applications For proteins requiring specific glycosylation patterns, consider engineered yeast strains with humanized glycosylation pathways [5].

Q5: How can I troubleshoot poor protein secretion?

Systematically address potential bottlenecks:

- Verify signal sequence functionality with positive controls

- Assess endoplasmic reticulum capacity (unfolded protein response)

- Monitor protein degradation in culture supernatant

- Optimize cultivation conditions (temperature, pH, feeding)

- Co-express foldases and chaperones [5] [36]

Codon optimization is an essential technique in synthetic biology and biopharmaceutical production that enhances recombinant protein expression by fine-tuning genetic sequences. This process aligns the codon usage of a target gene with the preferred codons of a specific host organism, leveraging the degeneracy of the genetic code where multiple synonymous codons can encode the same amino acid [40] [41]. The primary goal is to enhance translational efficiency and achieve higher protein yields, which is crucial for producing enzymes, therapeutic proteins, and other valuable biologics [40] [42].

Different organisms exhibit distinct codon usage preferences, meaning they may favor specific codons for the same amino acid. When a gene from one organism is introduced into another, mismatched codon usage can lead to inefficient translation, reduced expression levels, or non-functional proteins [41]. By strategically modifying the nucleotide sequence to replace rare or less-favored codons with those preferred by the host, researchers can significantly improve protein production outcomes [40] [41].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: How do I choose the right codon optimization tool for my host organism?

The selection of an appropriate optimization tool depends heavily on your specific host organism and the protein you wish to express. Different tools employ varying algorithms and optimization strategies, which can produce divergent results [40].

- Consider Host-Specific Bias: Tools like JCat, OPTIMIZER, ATGme, and GeneOptimizer demonstrate strong alignment with genome-wide and highly expressed gene-level codon usage in common hosts like E. coli, S. cerevisiae, and CHO cells [40].

- Multi-Parameter Approach: Avoid tools that rely on a single metric like CAI. Instead, select tools that integrate multiple parameters, including Codon Adaptation Index (CAI), GC content, mRNA secondary structure stability (ΔG), and codon-pair bias (CPB) [40].

- Experimental Validation: Computational predictions don't always translate to experimental success. Tools like TISIGNER and IDT employ different optimization strategies that may work better for specific protein classes [40].

Troubleshooting Tip: If you experience low protein yields with one optimization tool, try generating sequences with alternative tools that use different algorithmic approaches and compare expression outcomes empirically.

FAQ 2: My codon-optimized gene shows high CAI but low protein expression. What could be wrong?

A high CAI indicates good alignment with host codon preference but doesn't guarantee successful expression. Several other factors could be limiting your protein production [40] [42].

- Check mRNA Secondary Structure: Overly stable secondary structures, especially near the 5' end, can impede ribosome binding and translation initiation. Use tools like RNAFold to calculate minimum folding energy (ΔG) [40].

- Review GC Content: Extremely high or low GC content can adversely affect mRNA stability and translation. Optimal ranges vary by organism (e.g., increased GC enhances stability in E. coli, while A/T-rich codons minimize secondary structure in S. cerevisiae) [40].

- Investigate Protein Folding: Too-rapid translation driven by exclusively using optimal codons may prevent proper protein folding, leading to aggregation and insolubility. Consider introducing strategic "slow" codons that can facilitate co-translational folding [42].

- Verify Actual tRNA Abundance: The "rare codon" assumption may be flawed, as wobble pairing and tRNA modifications enable a single tRNA to recognize multiple codons. The number of tRNA genes doesn't necessarily correlate directly with functional tRNA levels [42].

Troubleshooting Tip: Use a tool like RiboDecode that incorporates ribosome profiling data (Ribo-seq) to predict translation levels more accurately, as it considers cellular context beyond simple codon frequency [43].

FAQ 3: How can I address protein insolubility issues related to codon optimization?

Protein insolubility often results from improper folding, which can be exacerbated by non-optimal translation kinetics [8] [42].

- Slow Down Translation: Reduce growth temperature or inducer concentration to decrease the rate of protein synthesis, allowing the cellular folding machinery to keep up [8].

- Employ Chaperone Co-Expression: Co-express molecular chaperones (e.g., using Takara's Chaperone Plasmid Set) or heat-shock the culture before induction to enhance folding capacity [8].

- Utilize Fusion Tags: Fuse your target protein to highly soluble partners like maltose-binding protein or thioredoxin to improve solubility. Test both N and C-terminal fusions [8].

- Consider Codon Harmonization: Instead of maximizing codon optimality throughout the entire sequence, preserve the natural translation rhythm of the original organism, which may include strategically placed slower-translating regions important for proper folding [42].

Troubleshooting Tip: After lysis, centrifuge to separate soluble and insoluble fractions. Re-suspend the pellet in fresh buffer to the same volume as the supernatant to accurately determine what proportion of your protein is insoluble [8].

FAQ 4: What advanced strategies can I use for difficult-to-express proteins?

When standard optimization approaches fail, consider these advanced strategies:

- Deep Learning Approaches: Newer frameworks like RiboDecode use deep learning trained on ribosome profiling data to explore a vast sequence space beyond what rule-based algorithms can access, often yielding superior results [43].

- Codon Language Models: Models like CaLM (codon adaptation language model) leverage information in cDNA sequences that is lost when considering only amino acid sequences, providing stronger signals for predicting expression success [44].

- Host Engineering: Switch to specialized expression strains like E. coli Rosetta (supplements rare tRNAs) or SHuffle (enhances disulfide bond formation) [8] [45].

- Alternative Expression Systems: If repeated optimization in microbial systems fails, consider switching to eukaryotic hosts like Pichia pastoris, insect cells, or mammalian cell lines that may provide better folding environments for complex proteins [8] [46].

Troubleshooting Tip: Always verify your DNA construct by sequencing the entire expression cassette to ensure no unintended mutations have been introduced during the optimization and synthesis process [8].

Codon Optimization Tools and Parameters

Comparison of Widely Used Codon Optimization Tools

Table 1: Features of selected codon optimization tools and key parameters they incorporate

| Tool Name | Key Optimization Strategy | CAI | GC Content | mRNA Structure | Codon Pair Bias | Host Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JCat | Mimics host codon bias | ✓ | ✓ | [ ] | ✓ | E. coli, yeast, more |

| OPTIMIZER | Proportional codon usage | ✓ | ✓ | [ ] | [ ] | Multiple species |

| ATGme | Multi-parameter optimization | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | E. coli, CHO, more |

| GeneOptimizer | Iterative algorithm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | Multiple species |

| TISIGNER | Alternative strategy | ✓ | [ ] | ✓ | [ ] | Specialized focus |

| IDT Tool | Commercial algorithm | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | [ ] | Multiple species |

| RiboDecode | Deep learning/Ribo-seq | (implicit) | (implicit) | ✓ | (implicit) | Human, mammalian |

Key Parameters in Codon Optimization

Table 2: Essential parameters to consider in codon optimization and their impact on protein expression

| Parameter | Description | Optimal Range/Considerations | Impact on Expression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Codon Adaptation Index (CAI) | Measures similarity of codon usage to highly expressed host genes | 0.8-1.0 (higher indicates better alignment) | Primary indicator of translational efficiency |

| GC Content | Percentage of guanine and cytosine nucleotides in sequence | Varies by host: ~50-60% for E. coli, moderate for CHO cells | Affects mRNA stability and secondary structure |

| mRNA Secondary Structure (ΔG) | Stability of RNA folding measured by Gibbs free energy | Less stable 5' end facilitates ribosome binding | Critical for translation initiation efficiency |

| Codon Pair Bias (CPB) | Non-random pairing preference of adjacent codons | Matches host genome patterns | Influences translational accuracy and efficiency |

| tRNA Abundance | Cellular availability of corresponding tRNAs | Should match codon frequency | Determines translation elongation rate |

| Rare Codon Frequency | Occurrence of infrequently used codons | Minimize but not eliminate entirely | May cause ribosome stalling and truncation |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating Codon Optimization Effectiveness

Purpose: To systematically assess the impact of different codon optimization algorithms on protein expression levels.

Materials:

- DNA synthesis services or gene fragments with varied optimization approaches

- Appropriate expression host (e.g., E. coli SHuffle for disulfide-rich proteins)

- Expression vector with strong promoter (e.g., pET, pBAD series)

- Western blot equipment or activity assay reagents

- RNA structure prediction tools (RNAFold, UNAFold)

Procedure:

- Sequence Design: Generate 3-5 variant sequences of your target gene using different optimization tools (e.g., JCat, OPTIMIZER, and a deep learning approach like RiboDecode).

- Parameter Calculation: For each variant, compute key parameters including CAI, GC content, and minimum folding energy (MFE) using computational tools.

- Gene Synthesis and Cloning: Synthesize the variants and clone into your expression vector, maintaining identical promoter and terminator regions.

- Small-Scale Expression: Transform expression host and induce protein expression in small cultures (5-10 mL).

- Analysis:

- Measure cell density (OD600) before and after induction

- Lyse cells and separate soluble/insoluble fractions

- Analyze total expression by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining

- Quantify functional protein by activity assay or western blot

- Correlation Analysis: Compare expression outcomes with computational parameters to identify which metrics best predict success.

Troubleshooting: If all variants show poor expression, consider testing different expression hosts (e.g., switching from E. coli to yeast) or adding solubility tags to your target protein.

Protocol: Troubleshooting Low Protein Yields

Purpose: To systematically identify and address causes of low protein expression from codon-optimized genes.

Materials:

- Sequencing primers for expression cassette verification

- Centrifuge for soluble/insoluble fractionation

- Specialized expression strains (e.g., Rosetta, Origami)

- Chaperone plasmid sets

- Fusion tag vectors (MBP, GST, Trx)

Procedure:

- Verify Construct Integrity:

- Sequence the entire expression cassette

- Confirm correct ribosomal binding site and start codon

- Check for unintended mutations introduced during synthesis

Assess Protein Localization:

- Perform small-scale culture and induction

- Lyse cells and separate soluble/insoluble fractions by centrifugation

- Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE

Optimize Expression Conditions:

- Test different induction temperatures (18-37°C)

- Titrate inducer concentration (0.01-1 mM IPTG)

- Vary induction time (2-16 hours)

Enhance Folding Capacity:

- Co-express chaperone proteins (GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ)

- Use strains engineered for disulfide bond formation (SHuffle, Origami)

- Add fusion tags to improve solubility

Validate mRNA Levels:

- Extract mRNA and quantify transcript levels by RT-qPCR

- Compare with protein levels to distinguish translational vs. transcriptional issues

Interpretation: If mRNA is present but protein is not detected, the issue is likely translational or related to rapid degradation. If protein is insoluble, focus on folding enhancement strategies.

Workflow Visualization

Codon Optimization and Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents and resources for codon optimization experiments

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Products/Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Expression Strains | Supplement rare tRNAs or enhance folding | E. coli Rosetta, SHuffle, Origami |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets | Co-express folding chaperones | Takara Chaperone Plasmid Set |

| Fusion Tag Vectors | Improve solubility and purification | MBP, GST, Trx fusion systems |

| Gene Synthesis Services | Obtain codon-optimized sequences | IDT, Genewiz, Twist Bioscience |

| Codon Optimization Tools | Computational sequence design | JCat, OPTIMIZER, RiboDecode, IDT Tool |

| mRNA Structure Prediction | Analyze secondary structure impact | RNAFold, UNAFold, RNAstructure |

| Ribosome Profiling Data | Translation efficiency insights | Ribo-seq datasets (GEO repository) |