Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Enzyme Thermostability in Biomedical Applications

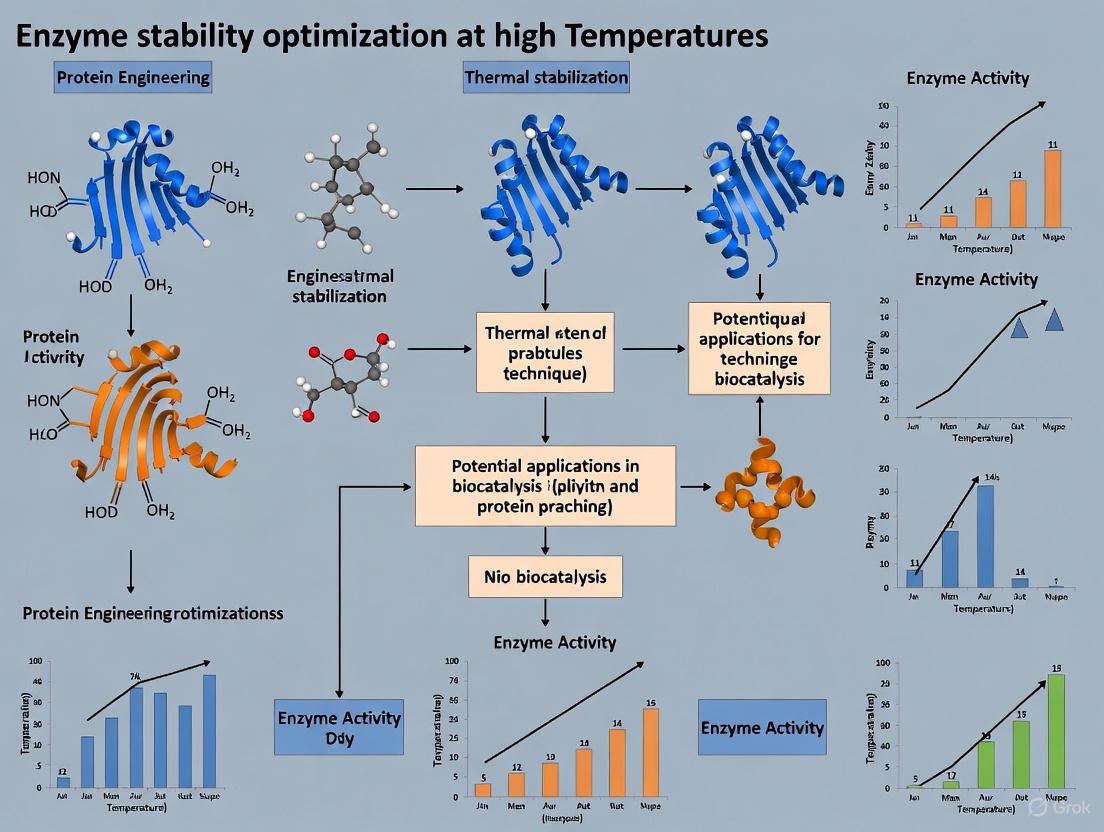

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing enzyme stability at high temperatures.

Advanced Strategies for Optimizing Enzyme Thermostability in Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing enzyme stability at high temperatures. It covers the fundamental principles of enzyme denaturation and degradation, explores advanced methodologies including enzyme engineering and immobilization, addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, and outlines validation frameworks for assessing performance. By integrating foundational science with practical application and future-looking trends, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to develop more robust and effective enzymatic therapeutics and processes.

The Fundamentals of Enzyme Thermostability: Understanding Denaturation and Degradation

Defining Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Stability in Enzymes

Core Concepts and Definitions

What is the fundamental difference between thermodynamic and kinetic stability of an enzyme?

Thermodynamic stability refers to the free energy difference (ΔG) between the folded (native) and unfolded (denatured) states of an enzyme. It describes the inherent preference of the protein to remain in its folded conformation at equilibrium. A higher, more positive ΔG indicates greater thermodynamic stability. In contrast, kinetic stability refers to an enzyme's resistance to irreversible inactivation over time under non-equilibrium conditions. It is governed by the energy barrier that must be overcome for the enzyme to lose its functional structure. An enzyme with high kinetic stability has a high activation energy for unfolding or inactivation, meaning it remains functional for longer periods under challenging conditions [1] [2].

How do these stability types relate to experimental observations in high-temperature applications?

For industrial processes at high temperatures, kinetic stability is often the more critical parameter. It directly determines the functional half-life of the enzyme under operational conditions. An enzyme might be thermodynamically stable (showing no tendency to unfold spontaneously at a given temperature) but still possess low kinetic stability, rapidly losing activity due to local structural fluctuations, aggregation, or chemical degradation at its active site. Research indicates that the active site is often more fragile than the enzyme as a whole, making local rigidity a key target for engineering kinetic stability [2].

Experimental Measurement and Quantification

What are the key experimental parameters for measuring each type of stability?

The following parameters are essential for characterizing enzyme stability:

Table: Key Parameters for Measuring Enzyme Stability

| Stability Type | Key Measurable Parameters | Typical Experimental Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamic Stability | Melting Temperature (Tm), Free Energy of Unfolding (ΔG), Denaturant Concentration at Midpoint Transition (Cm) | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Chemical Denaturation (e.g., with Guanidine HCl or Urea) monitored by Spectroscopy [3] [2] |

| Kinetic Stability | Half-life (t1/2) at a defined temperature, Temperature at which 50% of activity is lost after 15 minutes (T5015), Inactivation Rate Constant (kinact) | Incubation at elevated temperatures with periodic sampling for residual activity assay [2] |

Can you provide a detailed protocol for determining an enzyme's thermal half-life (t1/2)?

Objective: To determine the functional half-life of an enzyme at a specified temperature, a direct measure of its kinetic stability.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme sample

- Appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate or Tris buffer)

- Thermostatic water bath or heating block

- Ice bath

- Reagents for standard activity assay (e.g., substrate, cofactors, detection reagents)

Methodology:

- Pre-incubation: Aliquot the enzyme solution into multiple, identical tubes. Place these tubes in a thermostatic water bath set to the target temperature (e.g., 48°C, 55°C). Ensure the bath temperature is stable before starting.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), remove one tube from the heat source and immediately transfer it to an ice bath to quench the reaction.

- Residual Activity Assay: For each time-point sample, perform a standard activity assay under optimal conditions (e.g., at 37°C). The "0-minute" time point serves as the control representing 100% initial activity.

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of the residual activity (%) versus time. The decay in activity typically follows first-order kinetics. The half-life (t1/2) is calculated from the inactivation rate constant (k) using the formula: t1/2 = ln(2) / k [2].

Experimental Workflow: Measuring Kinetic Stability

Engineering and Optimization Strategies

What are the primary protein engineering strategies for improving kinetic stability?

Research has demonstrated that targeting flexible regions, particularly near the active site, is highly effective.

- Increasing Local Rigidity: A seminal study on Candida antarctica lipase B (CalB) showed that mutating flexible residues (with high B-factors) within 10 Å of the catalytic serine residue dramatically improved kinetic stability. The best mutant, D223G/L278M, exhibited a 13-fold increase in half-life at 48°C and a 12°C higher T5015 compared to the wild-type enzyme. Structural analysis revealed that the mutation formed an extra hydrogen bond network, decreasing fluctuations in the active site at high temperatures [2].

- Short-Loop Engineering: This strategy involves targeting rigid "sensitive residues" in short-loop regions and mutating them to hydrophobic residues with large side chains. This fills cavities and improves stability. Applied to three different enzymes (lactate dehydrogenase, urate oxidase, and D-lactate dehydrogenase), this method increased their half-lives by 1.43 to 9.5 times that of their wild-type counterparts [4].

- Data-Driven and Machine Learning Approaches: The development of high-quality datasets like BRENDA, ThermoMutDB, and ProThermDB enables machine learning models to predict stabilizing mutations. These models can analyze patterns from thousands of protein sequences and stability measurements to guide rational design, significantly reducing the experimental screening load [3] [5].

Strategy Diagram: Engineering Kinetic Stability

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: My enzyme shows a high melting temperature (Tm) but loses activity rapidly at high temperatures. Why is this happening?

This is a classic observation where thermodynamic stability is high, but kinetic stability is low. A high Tm indicates resistance to global unfolding. The rapid activity loss suggests that local, irreversible events are causing inactivation without full unfolding. This could be due to:

- Aggregation of a partially unfolded state.

- Deamidation or oxidation of critical active site residues.

- Local structural distortion in the active site region, which is more flexible and fragile than the global structure [2].

- Solution: Focus on engineering kinetic stability by targeting flexible loops and residues near the active site to increase local rigidity.

FAQ 2: When using B-factors from crystal structures to select mutation sites, my results are inconsistent. What could be wrong?

While B-factors are a useful indicator of residue flexibility, they have limitations.

- Context Matters: B-factors represent mobility in the crystalline state, which may differ from solution dynamics.

- Functional Cruciality: Mutating a highly flexible residue that is essential for catalytic activity (e.g., a residue involved in substrate binding or conformational changes) can impair function even if it improves stability.

- Solution: Integrate B-factor analysis with other methods like molecular dynamics (MD) simulation, which models flexibility in solution. Prioritize residues that are flexible but not directly involved in the catalytic mechanism. The strategy of targeting residues within a specific radius (e.g., 10 Å) of the active site has proven successful [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Databases

This table lists essential resources for enzyme stability research.

Table: Essential Resources for Enzyme Stability Research

| Resource Name | Type/Function | Key Application in Stability Research |

|---|---|---|

| BRENDA Database [3] | Comprehensive Enzyme Database | Provides hand-curated data on enzyme optimal temperatures and stability parameters from published literature. |

| ThermoMutDB [3] | Stability Mutation Database | Allows retrieval of manually collected experimental data on melting temperature (Tm) and free energy changes (ΔΔG) for thousands of mutations. |

| ProThermDB [3] | Thermodynamic Database | Offers an extensive collection of protein thermodynamic stability data from high-throughput experiments. |

| Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis (ISM) [2] | Protein Engineering Technique | A method for systematically creating and screening libraries of mutations at pre-selected residue positions to find stabilizing variants. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software [2] | Computational Tool | Models the physical movements of atoms over time, used to calculate root mean square fluctuation (RMSF) and identify flexible regions for targeted mutagenesis. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Analytical Instrument | Directly measures the heat capacity of an enzyme solution as a function of temperature, used to determine the melting temperature (Tm) and ΔG of unfolding. |

Molecular Mechanisms of Heat-Induced Denaturation and Unfolding

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My enzyme precipitates or aggregates during heat stress experiments. What are the underlying mechanisms and potential solutions?

- Problem: Protein precipitation or aggregation under heat stress.

- Molecular Mechanism: Excessive heat disrupts the delicate balance between protein flexibility and rigidity, causing partial or global unfolding. This exposes hydrophobic regions normally buried in the native core, leading to irreversible aggregation through hydrophobic interactions [6] [7]. The cell's natural defense, orchestrated by heat shock proteins (HSPs) like Hsp70 and Hsp40, may be overwhelmed [8] [7].

- Solutions:

- Stabilize with Additives: Include osmolytes (e.g., glycerol, sorbitol) in your assay buffer to stabilize the protein's hydrated shell.

- Employ Molecular Chaperones: Add recombinant chaperones like Hsp70 or Hsp40 to your reaction mixture. These chaperones use an ATP-dependent mechanism to bind exposed hydrophobic patches on the client protein, preventing aberrant aggregation and facilitating refolding [8].

- Protein Engineering: Identify and rigidify flexible residues on the protein surface through site-directed mutagenesis. Computational tools like molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can pinpoint these destabilizing regions [6].

FAQ 2: Why does my enzyme lose catalytic activity at high temperatures, even if no aggregation is visible?

- Problem: Loss of catalytic activity without visible aggregation.

- Molecular Mechanism: Activity loss can precede global unfolding. Localized, subtle unfolding or increased flexibility in the active site can disrupt the precise alignment of catalytic residues or the structure of the substrate-binding pocket, rendering the enzyme inactive [6]. This is often a consequence of the breakage of weak interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic packing) that maintain the functional conformation.

- Solutions:

- Analyze Binding Pocket Dynamics: Use MD simulation tools (e.g.,

fpocket2) to monitor changes in the volume and geometry of the substrate-binding pocket under different thermal conditions [6]. - Rigidify the Active Site: Employ computational protein engineering (e.g., conformational biasing, free energy perturbation protocols like QresFEP-2) to design mutations that stabilize the active site conformation without compromising catalytic function [9] [6].

- Optimize Cofactors/Ions: Ensure optimal concentrations of essential cofactors or metal ions, which can critically stabilize the active site structure.

- Analyze Binding Pocket Dynamics: Use MD simulation tools (e.g.,

FAQ 3: I am getting inconsistent results when measuring thermal stability across different replicates. What key parameters should I control?

- Problem: Inconsistent thermal stability measurements.

- Molecular Mechanism: Inconsistencies often arise from unaccounted-for experimental variables that perturb the protein's energy landscape, such as subtle pH shifts affecting ionization states, uneven heating rates, or variable protein concentrations.

- Solutions:

- Standardize Heating Protocols: Use equipment with precise temperature control (e.g., thermostatted water baths) and ensure consistent ramp rates if performing thermal denaturation curves [10] [6].

- Meticulous Buffer Preparation: Precisely control pH, ionic strength, and chelating agents, as these factors profoundly influence electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding networks within the protein.

- Monitor Oligomeric State: Use techniques like analytical ultracentrifugation or size-exclusion chromatography to verify the consistent oligomeric state of your enzyme sample, as this can majorly impact stability [9].

Essential Experimental Protocols & Data

Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation for Analyzing Thermal Denaturation

This protocol uses computational methods to probe atomic-level structural changes in proteins under thermal stress [6].

Step 1: System Preparation.

- Obtain or generate a high-resolution 3D structure of your protein (e.g., from PDB or via AlphaFold3 prediction).

- Place the protein in a simulation box (e.g., a cube) with a minimum 1.0 nm distance from the box edge.

- Solvate the system using an explicit water model (e.g., TIP4P).

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize the system's charge.

Step 2: Simulation Setup.

- Use MD software like GROMACS.

- Apply a suitable force field (e.g., Amber99SB).

- Set the desired temperature (e.g., 303 K for native, 333 K for stress) and pressure (e.g., 1 bar) conditions.

- Perform energy minimization (e.g., via steepest descent algorithm) to relieve steric clashes.

Step 3: Production Run and Trajectory Analysis.

- Run simulations for a sufficient duration (e.g., 60 ns per replicate) to capture unfolding events.

- Analyze trajectories using built-in functions to calculate key metrics:

- Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Measures overall structural drift from the starting conformation.

- Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF): Identifies locally flexible or unstable regions.

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Indicates global compaction or expansion.

- Solvent-Accessible Surface Area (SASA): Tracks exposure of hydrophobic core residues.

- Hydrogen Bonds: Monitors the breakage of stabilizing interactions [6].

Experimental Validation of Thermostability

- Method: Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) or Fluorescence-based Thermal Shift Assay.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a purified protein sample in a suitable buffer.

- For Thermal Shift Assays: Add a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) that binds to exposed hydrophobic patches.

- Apply a controlled temperature gradient (e.g., from 25°C to 95°C) while monitoring the signal (heat flow in DSC, fluorescence in Thermal Shift).

- Determine the melting temperature (Tₘ), where 50% of the protein is unfolded. A higher Tₘ indicates greater thermal stability.

Quantitative Data on Protein Stability and Denaturation

Table 1: Key Structural Metrics from MD Simulations of an Enzyme Under Thermal Stress [6]

| Condition | RMSD (nm) | Rg (nm) | SASA (nm²) | Hbond Count | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 303 K / 1 bar | 0.15 ± 0.02 | 1.82 ± 0.01 | 115 ± 2 | 158 ± 5 | Native, stable state. |

| 333 K / 1 bar | 0.38 ± 0.05 | 1.95 ± 0.04 | 145 ± 5 | 132 ± 7 | Global unfolding; increased flexibility and hydrophobic exposure. |

Table 2: Characteristics of Major Heat Shock Proteins Involved in Stress Response [8] [7] [11]

| HSP Family | Primary Function | Role in Heat Stress | Key Regulatory Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hsp70 (HspA) | Prevent aggregation, promote refolding | Binds hydrophobic patches of client proteins; works with Hsp40 in an ATP-dependent cycle. | ATP binding/hydrolysis drives conformational changes for client binding and release. |

| Hsp40 (DNAJ) | Co-chaperone for Hsp70 | Delivers misfolded clients to Hsp70; stimulates Hsp70's ATPase activity. | J-domain interacts with Hsp70. A specific phenylalanine residue in the G/F region initiates client handoff [8]. |

| Hsp90 (HspC) | Maturation of client proteins | Stabilizes and activates specific stress-response signaling proteins. | Dynamic ATP-dependent cycle involving co-chaperones. |

| Small Hsps (HspB) | Prevent aggregation | Act as molecular "holdases," binding unfolding proteins to prevent irreversible aggregation. | ATP-independent; form large oligomeric complexes. |

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Heat Shock Protein Chaperone Pathway

Enzyme Thermostability Engineering Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Kits for Investigating Heat-Induced Denaturation

| Reagent / Kit | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Recombinant Hsp70 & Hsp40 Proteins | Study chaperone-assisted refolding in vitro; as additives to prevent aggregation. | Add to enzyme activity assays under heat stress to measure recovery [8]. |

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Fluorescent probe for Thermal Shift Assays to determine protein melting temperature (Tₘ). | High-throughput screening of ligand binding or mutagenesis effects on stability. |

| GROMACS Software | Open-source MD simulation package for modeling protein dynamics under thermal stress. | Simulate enzyme behavior at high temperatures to identify unfolding hotspots [6]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduce point mutations to rigidify flexible residues identified via MD simulations. | Create stabilized enzyme variants (e.g., QresFEP-2 designed mutants) [9] [6]. |

| ProteoSTAT Protein Aggregation Assay | Quantify and monitor protein aggregation in solution. | Measure the effectiveness of HSPs or stabilizers in suppressing heat-induced aggregation. |

For researchers and scientists focused on optimizing enzyme stability at high temperatures, understanding and mitigating chemical degradative pathways is paramount. Exposure to elevated temperatures, a common condition in industrial biocatalysis and drug development processes, accelerates detrimental chemical modifications in proteins. These modifications—primarily deamidation, oxidation, and succinimide formation—can lead to irreversible loss of enzymatic activity, altered substrate affinity, and increased immunogenicity in therapeutic proteins [12] [13]. This technical support center provides a targeted FAQ and troubleshooting guide to help you identify, quantify, and prevent these degradation events in your experiments, directly supporting the broader research objective of enhancing enzyme thermostability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Deamidation

FAQ 1: What is deamidation and why does it concern my high-temperature enzyme experiments? Deamidation is the non-enzymatic hydrolysis of the side-chain amide group in asparagine (Asn) and, to a lesser extent, glutamine (Gln) residues. This reaction becomes significantly accelerated at high temperatures and neutral to basic pH, leading to a mass increase of +1 Da and the introduction of a negative charge [12] [13]. This can disrupt critical hydrogen bonds and electrostatic interactions within your enzyme, causing loss of activity and stability, which is detrimental to thermostability research.

Troubleshooting: I've observed a loss of enzyme activity after incubation at 75°C. How can I confirm if deamidation is the cause?

- Check for pI Shift: Use isoelectric focusing (IEF). Deamidation adds a negative charge, shifting the protein's pI to a lower pH [12].

- Identify Susceptible Residues: Employ mass spectrometry. Nano reverse-phase HPLC coupled with ESI MS/MS (CID fragmentation) can pinpoint deamidated peptides with high accuracy by detecting the +1 Da mass shift [12].

- Analyze Local Sequence: Identify Asn residues followed by small, flexible residues like glycine (Gly), serine (Ser), or alanine (Ala) in your enzyme's sequence. These "Asn-Gly" motifs are highly deamidation-prone [12] [14].

FAQ 2: Can deamidation be prevented through protein engineering? Yes. Site-saturation mutagenesis (SSM) is a powerful strategy to replace deamidation-susceptible asparagines with more stable residues. Rather than simply substituting with aspartate, SSM allows you to screen a comprehensive library of amino acids at the target position to identify substitutions that not only prevent deamidation but also optimally maintain—or even enhance—enzyme activity and structural stability [12].

Succinimide Formation

FAQ 1: What is the role of the succinimide intermediate in degradation? The succinimide is a cyclic intermediate formed during the deamidation of asparagine and the isomerization of aspartate. Its formation involves nucleophilic attack by the backbone nitrogen on the side chain carbonyl, leading to a mass decrease of -17 Da [12] [14]. This intermediate is typically short-lived and hydrolyzes rapidly to a mixture of aspartic acid (Asp) and iso-aspartic acid (isoAsp). However, in some cases, it can be stabilized, constraining the protein backbone and potentially affecting conformation and function [15] [14].

Troubleshooting: My analytical HIC chromatogram shows unexpected hydrophobic peaks. Could this be a stable succinimide? Very likely. The succinimide intermediate is more hydrophobic than the native Asn or the hydrolyzed Asp/isoAsp products. Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) is an excellent tool for separating and detecting this species [14]. You can confirm its identity by:

- Fraction Collection: Collect the hydrophobic peak.

- Mass Analysis: Perform intact or reduced mass spectrometry on the fraction. A -17 Da mass loss on the heavy or light chain is a clear indicator [14].

- Re-chromatography: Re-inject the fraction. If the succinimide is metastable, you may observe re-equilibration to a mixture of succinimide and Asp/isoAsp species on the column [14].

FAQ 2: Is succinimide formation always detrimental to enzyme stability? Not universally. While typically a degradative pathway, there are exceptional cases, particularly in enzymes from hyperthermophiles, where a stable succinimide is integral to structural stability. For example, in Methanocaldococcus jannaschii glutaminase, a stable succinimide at position 109, shielded from hydrolysis by the adjacent aspartate residue, directly contributes to the enzyme's remarkable stability at 100°C [16] [15]. This highlights that context and structural environment are critical.

Oxidation

FAQ: Which amino acids are most susceptible to oxidation, and what are common oxidants? Methionine (Met) and tryptophan (Trp) are the most oxidation-prone amino acids. Cysteine, tyrosine, and histidine can also be affected. Common oxidants in bioprocessing include atmospheric oxygen, peroxides, light, and metal ions [17] [14]. Oxidation can alter side-chain hydrophobicity, disrupt binding sites, and promote aggregation.

Troubleshooting: How can I protect my enzyme from oxidation during high-temperature assays?

- Use Antioxidants: Include antioxidants like methionine, histidine, or sodium thiosulfate in your storage buffers and reaction mixtures to scavenge reactive oxygen species [17].

- Employ Chelating Agents: Add EDTA or EGTA to chelate metal ions that catalyze oxidation reactions.

- Control Light and Headspace: Store enzymes in amber vials and under an inert atmosphere (e.g., nitrogen or argon) to minimize photo-oxidation and oxidative damage from air.

- Consider Site-Directed Mutagenesis: For critical, highly susceptible residues, consider replacing Met with norleucine or other oxidation-resistant analogues via protein engineering [17].

Quantitative Data on Degradative Pathways

The following tables summarize key kinetic and structural data related to these degradative pathways to aid in your experimental planning and analysis.

Table 1: Deamidation Kinetics of Common Protein Motifs at High Temperature

| Sequence Motif | Relative Deamidation Rate | Primary Products | Key Influencing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asn-Gly | Very High | IsoAsp (∼75%), Asp (∼25%) | pH > 6, temperature > 75°C, flexible loop [12] [14] |

| Asn-Ser | High | IsoAsp, Asp | pH, temperature, solvent accessibility [12] |

| Asn-Ala | Moderate | IsoAsp, Asp | pH, temperature, tertiary structure [12] |

| Asn in rigid α-helix | Slow | IsoAsp, Asp | Structural rigidity, hydrogen bonding, inaccessibility [13] |

Table 2: Analytical Techniques for Monitoring Protein Degradation

| Technique | Parameter Measured | Application in Degradation Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| RP-HPLC / ESI MS/MS | Mass shift (+1 Da for deamidation, -17 Da for succinimide) | Identifies specific sites and extent of deamidation and stable succinimides [12] [14] |

| Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) | Surface hydrophobicity | Separates and quantifies succinimide intermediate (more hydrophobic) from native and deamidated forms [14] |

| Isoelectric Focusing (IEF) | Protein isoelectric point (pI) | Detects charge variants resulting from deamidation (pI shift to lower pH) [12] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) | Binding affinity (KD) | Quantifies functional impact of degradation (e.g., succinimide formation) on antigen/ligand binding [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Identifying Deamidation-Susceptible Residues by Mass Spectrometry

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to identify labile asparagines in a thermostable lipase [12].

Objective: To identify specific asparagine residues susceptible to heat-induced deamidation in your enzyme of interest.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme sample

- Heating block or water bath

- Ammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7.8-8.0)

- Trypsin or Lys-C protease (MS-grade)

- Nano RP-HPLC system coupled to an ESI mass spectrometer with CID fragmentation capability

Method:

- Heat Treatment: Incubate your purified enzyme (in a suitable buffer like phosphate or ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7-8) at a challenging temperature (e.g., 75°C - 90°C) for a set time (e.g., 30-60 minutes). Keep an unheated aliquot as a control.

- Enzymatic Digestion: Denature the heat-treated and control samples. Reduce disulfide bonds and alkylate cysteine residues. Then, digest the protein with trypsin (or another suitable protease) overnight at 37°C.

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: Inject the digested peptides onto the nano RP-HPLC system coupled to the mass spectrometer.

- The HPLC separates the peptides.

- The MS operates in data-dependent acquisition mode, selecting precursor ions for CID fragmentation.

- Data Analysis:

- Search the acquired MS/MS data against your enzyme's sequence using database search software (e.g., Mascot, Sequest).

- Identify deamidated peptides by searching for variable modifications of +0.984 Da on asparagine residues.

- Compare heat-treated and control samples. Peptides showing a significant increase in deamidation only in the heat-treated sample indicate heat-susceptible residues.

Protocol 2: Engineering Thermotolerance by Replacing Labile Asparagines

This protocol outlines a site-saturation mutagenesis approach to stabilize a lipase against deamidation [12].

Objective: To create and screen a variant of your enzyme with improved thermotolerance by replacing deamidation-susceptible asparagines identified in Protocol 1.

Materials:

- Plasmid DNA containing your enzyme's gene

- Site-saturation mutagenesis kit (e.g., using degenerate primers)

- Competent E. coli cells

- Luria-Bertani (LB) agar and broth with appropriate antibiotic

- Indicator plates or assay for enzyme activity (e.g., tributyrin agar for lipases)

- Microplate reader for high-throughput activity screening

Method:

- Mutagenesis Library Construction: Design degenerate primers that randomize the codon for the identified deamidation-susceptible asparagine residue. Perform PCR to generate a library of mutant plasmids where this position encodes all 20 possible amino acids.

- Transformation and Expression: Transform the mutant plasmid library into competent E. coli cells and plate on selective LB agar to obtain individual colonies.

- Primary Screening: Pick hundreds to thousands of colonies and culture in deep-well plates. Induce expression. Perform a high-throughput activity screen (e.g., using a fluorescent or colorimetric substrate in a microplate reader) under non-denaturing conditions to identify active clones.

- Secondary Screening for Thermotability: Take the active clones from the primary screen and subject them to a heat challenge (e.g., incubate lysates at 80°C for 10-30 minutes). Measure the residual activity post-heat treatment.

- Characterization: Isolate the mutant plasmids from clones showing the highest residual activity and identify the amino acid substitution by DNA sequencing. Express and purify the best-performing variants for detailed biochemical characterization, including melting temperature (Tm) and half-life at elevated temperatures.

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Degradation Pathway of Asparagine

This diagram illustrates the complete degradation pathway of an asparagine residue, highlighting the formation of the key succinimide intermediate and its hydrolysis products.

Diagram 1: Asparagine Degradation Pathway.

Experimental Workflow for Enhancing Thermostability

This workflow outlines the integrated experimental strategy, from initial identification of weak spots to the final validation of a stabilized enzyme variant.

Diagram 2: Thermostability Enhancement Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Studying Protein Degradation

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Ammonium Bicarbonate Buffer (pH 8.0) | Standard buffer for enzymatic digestion prior to MS. | Volatile, making it easy to remove by lyophilization. |

| Trypsin, Lys-C (MS-grade) | Proteases for specific digestion of proteins into peptides for MS analysis. | MS-grade ensures high purity and minimizes autolysis. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis Kit | Creates a comprehensive library of all 20 amino acids at a target codon. | Critical for finding optimal substitutions beyond Asp. |

| Tributyrin or Specific Substrate Agar | Indicator plates for rapid, visual primary screening of enzyme activity. | Allows screening of thousands of colonies. |

| Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) Column | Analytical separation of protein variants based on hydrophobicity. | Ideal for detecting stable succinimide intermediates. |

| Methionine / Histidine | Antioxidants added to formulations to mitigate methionine oxidation. | Common excipients in therapeutic protein formulations. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues with Tm and kd Determination

Problem 1: Inconsistent Enzyme Deactivation Kinetics

- Question: Why does my enzyme's residual activity not follow a simple first-order decay, leading to an unreliable deactivation rate constant (kd)?

- Answer: Single-step, first-order deactivation is not universal. Your enzyme may exhibit more complex deactivation behavior.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Model Testing: Fit your time-course residual activity data to various kinetic models beyond the first-order model. Common alternatives include:

- Statistical Analysis: Use statistical criteria (e.g., R², root mean square error) to identify which model best describes your data. The "best" model provides the most reliable estimate for kd [18].

Problem 2: Discrepancy Between Predicted and Experimental Tm

- Question: The melting temperature (Tm) I measured experimentally is significantly different from the value predicted by in silico tools. What could cause this?

- Answer: Discrepancies can arise from both experimental conditions and limitations of predictive models.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Experimental Conditions:

- Buffer Composition: Confirm the pH and ionic strength of your assay buffer. The Tm of an enzyme is highly dependent on its environment [19].

- Cofactors and Ligands: The presence or absence of substrates, cofactors, or inhibitors can dramatically stabilize or destabilize the enzyme's structure, altering the observed Tm.

- Prediction Model Limitations:

- Training Data: Many published Tm prediction models are trained on datasets with limited organism coverage or inherent biases. Always check the model's documentation for its scope and limitations [20].

- Sequence Redundancy: Models trained on redundant datasets (where many sequences are similar) may not generalize well to novel enzymes. Prefer tools built on non-redundant datasets for better accuracy [20].

- Experimental Conditions:

Problem 3: Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Tm Assays

- Question: The signal from my Tm assay (e.g., using a fluorescent dye) is weak and noisy, making the transition point difficult to determine.

- Answer: A weak signal can stem from low protein concentration or suboptimal instrument settings.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Protein Concentration: Ensure your enzyme sample is sufficiently concentrated. For many spectroscopic techniques, a concentration in the range of 0.1-1 mg/mL is typical.

- Parameter Optimization: Use a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach to systematically optimize assay conditions such as dye concentration, scan rate, and gain settings on your instrument. This method is more efficient than testing one factor at a time [21].

- Positive Control: Include a well-characterized control protein with a known Tm in your experiment to verify your assay setup is functioning correctly.

Problem 4: High Variability in kd Measurements Between Replicates

- Question: My calculated deactivation rate constants (kd) have high variability between experimental replicates.

- Answer: This often points to inconsistencies in sample handling or temperature control.

- Investigation & Solution:

- Temperature Equilibration: Ensure your enzyme samples are fully equilibrated to the target inactivation temperature before starting the experiment. Use a calibrated thermometer to verify the temperature in the heating block or water bath.

- Rapid Sampling & Cooling: When withdrawing samples at different time intervals, immediately transfer them to an ice-water bath to quench the deactivation reaction rapidly [18].

- Enzyme Storage and Handling: Always store enzymes at the recommended temperature (-20°C or -70°C) and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. The enzyme should be the last component added to the reaction mix [22] [23].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between Tm and kd?

- Answer: The melting temperature (Tm) is a thermodynamic parameter. It represents the temperature at which 50% of the protein molecules in a sample are unfolded. It is a measure of the inherent thermal stability of the native protein structure. In contrast, the deactivation rate constant (kd) is a kinetic parameter. It describes the speed at which an enzyme loses its catalytic activity at a specific temperature, which may involve processes like irreversible aggregation that follow unfolding.

FAQ 2: Can I use kd to calculate an enzyme's half-life at a given temperature?

- Answer: Yes. If the deactivation follows a first-order kinetic model, the half-life (t{1/2}) is directly calculated from k*d* using the formula: t{1/2} = ln(2) / k_d. This provides a practical metric for estimating an enzyme's operational lifespan under process conditions [19].

FAQ 3: How can I improve the thermostability of my enzyme?

- Answer: Several strategies can be employed:

- Enzyme Engineering: Use directed evolution or rational design (e.g., site-directed mutagenesis) to introduce stabilizing mutations. Machine learning models are now emerging to guide this process by predicting stability-enhancing mutations [3].

- Immobilization: Attaching the enzyme to a solid support can often enhance its thermal stability and allow for reuse [24].

- Additives: Including stabilizers like polyols (e.g., trehalose) or certain salts in the reaction buffer can increase enzyme rigidity under heat stress [24].

- Optimize Reaction Medium: Adjusting pH, substrate concentration, and ionic strength can also improve stability [24].

FAQ 4: Where can I find reliable data on enzyme Tm and stability?

- Answer: Several curated databases are invaluable resources:

- BRENDA: A comprehensive enzyme database containing functional data, including optimal temperatures and stability information collected from the literature [3].

- ThermoMutDB: A database of manually collected thermal stability data for protein mutants, including changes in Tm and Gibbs free energy (ΔΔG) [3].

- ProThermDB: A large database of thermodynamic parameters for wild-type and mutant proteins [3].

The following table summarizes kinetic and thermodynamic parameters from a study on two microbial lipases, providing a concrete example of how Tm and deactivation kinetics are reported and compared [18].

Table 1: Comparative Kinetic and Thermodynamic Stability Parameters for Bacterial and Fungal Lipases

| Parameter | Lipase PS (B. cepacia) | Palatase (R. miehei) | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Best-Fit Kinetic Model | First-order | Weibull Distribution | Model best describing residual activity decay over time. |

| Activation Energy (Ea) | |||

| 34.8 kJ mol⁻¹ | 23.3 kJ mol⁻¹ | Energy required to initiate denaturation. A higher value suggests greater intrinsic stability. | |

| Gibbs Free Energy (ΔG⁺) | |||

| 98.6 – 104.9 kJ mol⁻¹ | 86.0 – 92.1 kJ mol⁻¹ | The free energy change for the transition from native to denatured state. Higher positive values indicate a more stable enzyme. |

Standard Experimental Protocol: Determining kd and Tm

Methodology 1: Determining the Deactivation Rate Constant (kd)

This protocol describes how to determine the kinetic deactivation constant by measuring residual activity over time at a fixed temperature [18].

- Preparation: Dilute the enzyme in an appropriate, non-reactive buffer (e.g., Tris-HCl, phosphate).

- Thermal Inactivation: Aliquot the enzyme solution into multiple, small tubes. Incubate them in a precision-controlled water bath or heating block at the desired temperature (e.g., 40°C, 50°C, 60°C).

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 2, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes), remove a tube and immediately place it in an ice bath to halt thermal inactivation.

- Residual Activity Assay: Measure the remaining enzymatic activity of each chilled sample using a standardized assay (e.g., spectrophotometric assay with a specific substrate).

- Data Analysis: Plot the natural logarithm of residual activity (A/A₀) versus time. For first-order deactivation, this plot will be linear. The slope of the linear regression line is the deactivation rate constant (-kd).

Methodology 2: Determining the Melting Temperature (Tm) via Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF)

This protocol outlines a common, high-throughput method for determining Tm using a real-time PCR instrument.

- Sample Preparation: In a PCR tube or plate, mix:

- Enzyme solution (typical final concentration 0.1-0.5 mg/mL)

- A fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic regions exposed upon unfolding (e.g., SYPRO Orange)

- Assay buffer

- Thermal Ramp: Load the plate into a real-time PCR instrument. Run a thermal ramping protocol, typically from 25°C to 95°C with a gradual increase (e.g., 1°C per minute).

- Fluorescence Monitoring: The instrument monitors the fluorescence of the dye continuously. As the protein unfolds, the dye binds and fluorescence increases.

- Data Analysis: Plot fluorescence versus temperature. The data is fitted to a sigmoidal curve. The Tm is defined as the temperature at the midpoint of the protein unfolding transition, corresponding to the inflection point of the curve.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for investigating enzyme thermostability, integrating both key metrics.

Workflow for Enzyme Thermostability Analysis

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for Thermostability Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable Enzymes | Positive controls for high-temperature assays; benchmarks for engineering. | Lipase PS from B. cepacia [18]. |

| Fluorescent Dyes (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Detection of protein unfolding in DSF (Tm) assays. | Binds hydrophobic patches exposed upon denaturation. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Esters (pNPP) | Chromogenic substrate for activity assays of lipases and esterases. | Hydrolysis releases yellow p-nitrophenol, measurable at 410 nm [18]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Efficiently optimizes multiple assay parameters (pH, buffer, temp) simultaneously. | Speeds up the assay optimization process [21]. |

| Immobilization Supports (e.g., Resins, Beads) | Enhancing enzyme thermal stability and reusability via covalent or physical attachment. | Can extend operational half-life significantly [24]. |

| Machine Learning Tools (e.g., PPTstab) | In silico prediction of protein Tm and design of thermostable variants. | Uses protein sequence to predict stability [20]. |

The Role of Hydrophobic Interactions and Conformational Entropy

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the relative contribution of hydrophobic interactions to overall protein stability? Based on the analysis of 22 proteins ranging from 36 to 534 residues, hydrophobic interactions contribute 60 ± 4% to the overall stability of a protein, while hydrogen bonds contribute 40 ± 4% [25]. The globular conformation of proteins is stabilized predominately by hydrophobic interactions [25].

Q2: How much stability does burying a hydrophobic group add? Experimental Δ(ΔG) values for 148 hydrophobic mutants across 13 proteins indicate that burying a –CH2– group on folding contributes, on average, 1.1 ± 0.5 kcal/mol to protein stability [25]. The stabilization can vary with protein size [25].

Q3: Why are native proteins only marginally stable? The native state of a protein is only marginally stable under physiological conditions due to a balance between large, favorable interactions (like the hydrophobic effect and van der Waals interactions) and a large, unfavorable factor: the loss of chain conformational entropy upon folding [26]. This conformational entropy contributes about 2.4 kcal/mol per residue to protein instability [25].

Q4: Our enzyme is prone to aggregation at high temperatures. What are the main stabilization strategies? Physical instability, such as denaturation and aggregation, is a common failure mode when hydrophobic regions become exposed [27]. Traditional solutions include:

- Optimizing Buffers and Stabilizers: Screening for optimal pH and adding stabilizers like sucrose or trehalose to create a protective hydration shell [27].

- Adding Excipients: Using amino acids like arginine to prevent aggregation, and surfactants like polysorbates to shield the enzyme from interfacial stress [27].

- Lyophilization: Removing water via freeze-drying, though this process introduces its own stresses [27].

- Short-loop Engineering: An advanced strategy that involves mutating rigid "sensitive residues" in short-loop regions to hydrophobic residues with large side chains to fill cavities and improve thermal stability [4].

Q5: How does protein size affect the contribution of hydrophobic interactions? Hydrophobic interactions contribute less to the stability of small proteins compared to large ones. For example, the stabilization per –CH2– group is 0.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mole for the 36-residue villin headpiece subdomain (VHP), but 1.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mol for the 341-residue VlsE protein [25].

Table 1: Energetic Contributions of Hydrophobic Interactions to Protein Stability

| Contribution Factor | Average Energy | Context / Conditions |

|---|---|---|

| Burying a –CH2– group | 1.1 ± 0.5 kcal/mol | Average from 148 mutants in 13 proteins [25] |

| Stabilization in a large protein (VlsE, 341 residues) | 1.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mol per –CH2– | Ile to Val mutants [25] |

| Stabilization in a small protein (VHP, 36 residues) | 0.6 ± 0.3 kcal/mol per –CH2– | Multiple Ala mutants [25] |

| Chain conformational entropy (destabilizing) | ~2.4 kcal/mol per residue | Opposes folding [25] |

| Total hydrophobic contribution to VHP stability | ~40 kcal/mol | Sum from key residues (Phe18, Met13, etc.) [25] |

Table 2: Thermal Stability Enhancements from Short-Loop Engineering [4]

| Enzyme | Source | Half-life Improvement (vs. Wild-type) |

|---|---|---|

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Pediococcus pentosaceus | 9.5 times higher |

| Urate oxidase | Aspergillus flavus | 3.11 times higher |

| D-lactate dehydrogenase | Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1.43 times higher |

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Low Catalytic Efficiency in a Computationally Designed Enzyme

Context: This is a common issue in de novo enzyme design, where initial designs may have low catalytic rates (kcat) and efficiencies (kcat/KM) [28].

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Structural distortions in the designed active site, shifting the catalytic constellation from optimality by a few degrees or tenths of an Ångstrom [28].

- Solution: Implement a more robust computational workflow that allows for backbone flexibility and better positioning of the catalytic theozyme. Using backbone fragments from natural proteins can improve foldability and active-site accuracy [28].

- Cause 2: Low stability of the initial design, limiting its ability to accommodate activity-enhancing mutations [28].

- Solution: Apply protein stabilization calculations (e.g., PROSS) to the entire protein structure to enhance overall stability before optimizing the active site. Highly stable scaffolds (e.g., >85 °C) can support high-efficiency catalysis [28].

- Cause 3: Failure to account for long-range electrostatic interactions or protein dynamics in the design process [28].

- Solution: Use atomistic design methods that can optimize all active-site positions simultaneously, and consider using "fuzzy-logic" optimization to balance conflicting objectives like low system energy and high desolvation of catalytic residues [28].

Problem: Incomplete Restriction Enzyme Digestion Context: While not directly related to hydrophobic interactions, this is a common molecular biology issue when preparing enzyme variants or constructs for stability studies.

Potential Causes and Solutions [29]:

- Cause: Cleavage is blocked by methylation (e.g., Dam, Dcm, or CpG methylation).

- Solution: Check the methylation sensitivity of your enzyme. If sensitive, grow the plasmid in a dam-/dcm- strain.

- Cause: Using the wrong buffer, too few enzyme units, or an overly short incubation time.

- Solution: Use the recommended buffer supplied with the enzyme, at least 3–5 units per μg of DNA, and increase incubation time (1–2 hours is typical).

- Cause: Salt inhibition or contamination from PCR components.

- Solution: Clean up the DNA prior to digestion to remove salts or inhibitors. Ensure the DNA solution is no more than 25% of the total reaction volume.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Conformational Stability by Urea Denaturation This protocol is used to determine the change in conformational stability (Δ(ΔG)) for protein mutants, as described for VHP and VlsE [25].

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of protein solutions with varying concentrations of urea.

- Denaturation Curves: Measure the circular dichroism (CD) signal at 220 nm or 222 nm as a function of urea concentration.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the unfolding curves using the linear extrapolation method (LEM) [25].

- Calculate Stability:

- Fit the data to determine the midpoint of denaturation (Urea₁/₂) and the

m-value(the slope of the ΔG vs. [denaturant] plot). - The free energy of folding in water, ΔG(H₂O), is calculated as the intercept of the plot at 0 M urea.

- For a mutant, the change in stability is calculated as Δ(ΔG) = ΔUrea₁/₂ × average

m-value(of wild-type and mutant) [25].

- Fit the data to determine the midpoint of denaturation (Urea₁/₂) and the

Protocol 2: Short-Loop Engineering for Enhanced Thermal Stability This strategy targets rigid "sensitive residues" in short-loop regions to improve enzyme stability [4].

Workflow:

- Identify Short Loops: Locate short-loop regions in the enzyme's three-dimensional structure.

- Find Sensitive Residues: Identify rigid "sensitive residues" within these loops that are crucial for stability.

- Design Mutations: Mutate these sensitive residues to hydrophobic residues with large side chains (e.g., Leu, Ile, Phe) to fill internal cavities and enhance packing.

- Experimental Validation: Express and purify the mutant enzymes. Measure the half-life at a target temperature and compare it to the wild-type enzyme to quantify improvement [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Protein Stability and Engineering Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Urea / Guanidine HCl | Chemical denaturants used in unfolding experiments to measure conformational stability [25]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer | Instrument used to monitor changes in secondary structure during protein unfolding [25]. |

| dam-/dcm- E. coli Strains | Host strains for propagating plasmid DNA without methylation that could block restriction enzyme digestion [29]. |

| DNA Clean-up Spin Columns | Used to purify DNA after PCR or restriction digest, removing salts, enzymes, or other inhibitors that can interfere with subsequent reactions [29]. |

| High-Fidelity (HF) Restriction Enzymes | Engineered enzymes with reduced star activity (non-specific cutting), useful for reliable cloning [29]. |

| Stabilizing Excipients (e.g., Sucrose, Trehalose, Arginine) | Used in formulation to protect enzyme structure, create a hydration shell, or prevent aggregation [27]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80) | Added to formulations to shield enzymes from interfacial and mechanical stress [27]. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Diagram 1: Strategies for Enhancing Enzyme Thermostability

Diagram 2: Thermodynamic Balance in Protein Folding

Proven Strategies for Enhancement: Engineering and Formulation

Directed Evolution and Rational Design for Improved Thermal Tolerance

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the fundamental trade-off I should be aware of when starting an enzyme thermostability project? A major challenge in enzyme engineering is the stability-activity trade-off, where mutations that enhance thermal stability can sometimes reduce catalytic activity, and vice versa. Advanced strategies like the machine learning-based iCASE focus on balancing this trade-off by using multi-dimensional conformational dynamics to guide mutations that improve both properties simultaneously [30].

Q2: My rationally designed mutant shows excellent thermostability in simulations but poor expression or activity. What could be wrong? This is a common issue. Your design might have over-stabilized rigid regions, hindering the conformational flexibility needed for catalysis. Consider targeting flexible loops rather than the entire protein structure. The short-loop engineering strategy has proven effective by mutating rigid "sensitive residues" in short loops to hydrophobic residues with large side chains, filling cavities and improving stability without compromising function [4]. Also, verify you haven't disrupted critical active site residues or introduced steric clashes not predicted by the model.

Q3: During directed evolution, my library is too large to screen efficiently. How can I focus my efforts? Instead of purely random mutagenesis, adopt a semi-rational approach. Use tools like consensus sequence analysis or computational energy calculations (ΔΔG) to identify evolutionary "hotspots" or unstable regions. Techniques like site-saturation mutagenesis allow you to exhaustively explore key positions, creating smaller, higher-quality libraries with a greater probability of containing improved variants [31].

Q4: What analytical techniques are essential for validating improved thermostability? You should employ a combination of biochemical and biophysical assays:

- Half-life (t₁/₂) at a target temperature: Measures the time an enzyme retains 50% of its initial activity, directly indicating operational stability [32].

- Melting Temperature (Tₘ): The temperature at which 50% of the protein is unfolded. An increase in Tₘ confirms enhanced structural stability [17] [32].

- Optimal Temperature (Tₒₚₜ): The temperature at which enzyme activity is maximal [17].

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations: Provides atomistic insight into reduced flexibility, increased rigidity, and enhanced hydrogen bonding networks in mutants [32].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Low proportion of beneficial mutants in directed evolution libraries.

- Potential Cause: Overly aggressive random mutagenesis leading to a high proportion of non-functional proteins.

- Solution: Tune your error-prone PCR (epPCR) conditions to aim for a low mutation rate (e.g., 1-3 amino acid substitutions per variant). Combine this with DNA shuffling of beneficial mutants from initial rounds to recombine positive mutations and eliminate deleterious ones [31].

Problem: Inconsistent thermostability measurements between assays.

- Potential Cause: Use of a single, potentially unreliable assay.

- Solution: Correlate data from functional assays (e.g., residual activity after heat incubation) with biophysical assays (e.g., differential scanning fluorimetry - DSF, or circular dichroism - CD) to get a comprehensive picture of stability. The Protein Thermal Shift (PTS) assay is a widely used high-throughput method for this purpose [33].

Problem: Rational design predictions are inaccurate.

- Potential Cause: Relying on a single computational tool or a low-quality homology model.

- Solution: Utilize integrated computational approaches. Combine consensus sequence analysis with tools like HoTMuSiC for hotspot mutation scanning and Rosetta for ΔΔG calculations [32] [33]. If a crystal structure is unavailable, ensure your homology model is built on a high-quality template and validated.

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: A Semi-Rational Workflow for Thermostability Enhancement

This protocol integrates consensus analysis and computational design, as demonstrated for Protein-Glutaminase (PG) [32].

Identify Target Residues:

- Perform multiple sequence alignment of homologous enzymes to identify conserved and variable residues.

- Use computational tools (e.g., FoldX, Rosetta) to calculate the wild-type structure's stability and pinpoint unstable regions.

- Select non-conserved residues located in flexible loops or regions with high B-factor values.

Design Mutations:

- For each target residue, use software to predict the change in folding free energy (ΔΔG) for all 19 possible amino acid substitutions.

- Filter for mutations predicted to significantly lower the free energy (negative ΔΔG).

- Manually inspect top candidates to avoid introducing mutations near the active site that could disrupt activity.

Library Construction:

- Use site-directed mutagenesis or saturation mutagenesis at the prioritized residues to create a focused mutant library.

Screening for Thermostability:

- Express and purify the mutant library.

- Perform a high-throughput thermal challenge assay. Incubate enzymes at an elevated temperature (e.g., 60°C) for a set time.

- Measure residual activity and identify variants with significantly higher residual activity than the wild type.

- For promising hits, determine the half-life (t₁/₂) at 60°C and melting temperature (Tₘ).

Diagram 1: Semi-rational design workflow.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Directed Evolution (iCASE Strategy)

This protocol uses the iCASE strategy for simultaneous stability and activity enhancement [30].

Identify High-Fluctuation Regions:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations on the wild-type enzyme.

- Calculate the isothermal compressibility (βT) to identify high-fluctuation regions of the protein.

Calculate Dynamic Squeezing Index (DSI):

- Compute the DSI, an indicator coupled with the active center, for residues in the high-fluctuation regions.

- Select residues with a DSI > 0.8 (top 20%) as candidate sites for mutation.

Predict and Combine Mutations:

- Use Rosetta or similar software to predict the ΔΔG for mutations at candidate sites.

- Screen single-point mutants experimentally for improved activity and stability.

- Combine beneficial single-point mutations to generate combinatorial mutants.

Model Validation and Analysis:

- Employ a dynamic response predictive model (a structure-based supervised machine learning model) to predict enzyme function and fitness.

- Validate the model's predictions with experimental data from the combinatorial mutants.

- Use MD simulations to confirm that stabilized mutants exhibit reduced flexibility and enhanced structural rigidity.

Table 1: Measurable Outcomes of Enzyme Thermostability Engineering

| Enzyme | Strategy | Mutations | Half-life (t₁/₂) Improvement | Melting Temp (Tₘ) Change | Activity Change | Citation Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein-Glutaminase (PG) | Semi-Rational Design | A79S/T97V/S108P/N154D/L156Y | 55.1-fold increase at 60°C (1132.75 min) | 75.21°C | No loss | [32] |

| Xylanase (XY) | Machine Learning (iCASE) | R77F/E145M/T284R | Not Specified | +2.4°C | 3.39-fold increase | [30] |

| Lactate Dehydrogenase | Short-loop Engineering | Not Specified | 9.5-fold increase | Not Specified | Not Specified | [4] |

| Vip3Aa Insecticidal Protein | Rational Design (HoTMuSiC) | N242C | Moderate Improvement | Moderate Improvement | Retained high activity | [33] |

Table 2: Comparison of Major Enzyme Engineering Strategies

| Strategy | Throughput | Requirement for Prior Knowledge | Key Advantage | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Directed Evolution | High | Low | Discovers non-intuitive solutions; no need for structural data | Exploring vast sequence space; when mechanistic knowledge is limited [31] |

| Rational Design | Low | High (3D Structure) | Targeted and efficient; provides mechanistic insight | Making specific, well-informed stabilizations based on structure [17] [33] |

| Semi-Rational Design | Medium | Medium | Balances throughput and efficiency; creates smart libraries | Leveraging evolutionary data or computational predictions [32] [31] |

| Machine Learning (e.g., iCASE) | High (after training) | High (for training data) | Can predict complex stability-activity trade-offs; powerful for epistasis analysis | Multi-property optimization and navigating complex fitness landscapes [30] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Thermostability Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) Kit | Introduces random mutations across the gene sequence during amplification. | Creating large, diverse libraries for the initial rounds of directed evolution [31]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Introduces specific, pre-determined mutations into a plasmid. | Constructing single-point mutants for validation or creating focused semi-rational libraries [31]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Predicts protein structures and energies; used for calculating ΔΔG of mutations. | In silico screening of mutation libraries to prioritize stabilizing variants for experimental testing [32] [30]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS) | Simulates physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Analyzing structural rigidity, flexibility, and hydrogen bonding networks in wild-type vs. mutant enzymes [32]. |

| Thermal Shift Assay Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | Binds to hydrophobic patches exposed upon protein denaturation. | High-throughput determination of melting temperature (Tₘ) via real-time PCR instruments [33]. |

| Consensus Sequence Analysis Tools (e.g., WebLogo) | Identifies conserved amino acids in a protein family from multiple sequence alignments. | Predicting important residues for stability and identifying mutable positions for engineering [32]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Covalent Binding Troubleshooting

Problem: Significant loss of enzyme activity after immobilization

- Potential Cause 1: The covalent reaction involves functional groups essential for catalytic activity.

- Potential Cause 2: Harsh reaction conditions (e.g., extreme pH, aggressive coupling chemicals) denature the enzyme.

- Solution: Optimize the coupling buffer's pH and ionic strength. Consider using milder activating agents or reducing the reaction time [36].

- Potential Cause 3: Uncontrolled multipoint attachment leads to rigidification and conformational distortion of the enzyme's native structure.

- Solution: Use a support material with a controlled density of reactive groups. Employ a spacer arm (e.g., a longer linker) to reduce steric hindrance and provide more mobility for the enzyme [35].

Problem: Enzyme leaching during operation despite covalent binding

- Potential Cause: Insufficient covalent bonds formed between the enzyme and the support, leading to weak attachment.

Entrapment & Encapsulation Troubleshooting

Problem: Low observed reaction rate, suggesting mass transfer limitations

- Potential Cause: The pore size of the entrapping matrix is too small, hindering the diffusion of substrate and product molecules.

- Potential Cause: The matrix is too thick, creating a long diffusion path.

- Solution: Fabricate thinner membranes or smaller gel beads to increase the surface-area-to-volume ratio and reduce the diffusion path length [36].

Problem: Enzyme leakage from the entrapping matrix

- Potential Cause: The pores in the matrix are larger than the enzyme molecules.

- Solution: Adjust the polymerization or gelation conditions to reduce the average pore size. Use a composite matrix or a coating layer (e.g., a polyelectrolyte shell) to create a tighter mesh and physically retain the enzyme [36].

Cross-Linking Troubleshooting

Problem: Formation of insoluble precipitates with low activity (specifically for Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates - CLEAs)

- Potential Cause: The concentration of the cross-linker (e.g., glutaraldehyde) is too high, causing over-cross-linking and excessive rigidity.

- Solution: Titrate the cross-linker concentration to find the optimal level that stabilizes the aggregates without inactivating the enzyme. Consider using alternative cross-linking agents like divinyl sulfone, which may offer different reactivity profiles [39].

- Potential Cause: The precipitant used to form aggregates is too harsh, denaturing the enzyme before cross-linking.

- Solution: Screen different precipitants (e.g., salts, organic solvents, polymers) under mild conditions to find one that achieves aggregation while preserving enzyme activity [39].

Problem: CLEAs exhibit poor mechanical stability and disintegrate in stirred reactors

- Potential Cause: The cross-linking is not robust enough to withstand shear forces.

- Solution: Add a "co-feeder" protein like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or a functional polymer to the enzyme mixture before cross-linking. This creates a more robust composite matrix and improves the mechanical properties of the CLEAs [39].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Which immobilization technique is best for maximizing enzyme stability at high temperatures? A: For high-temperature applications, covalent binding and cross-linking are generally superior. Covalent binding, especially multipoint attachment, rigidifies the enzyme structure, reducing flexibility and unfolding at elevated temperatures [37] [35]. Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) also demonstrate excellent thermostability due to the dense network of covalent bonds that lock the enzyme in its active conformation and protect against thermal denaturation [39].

Q2: We need to re-use our enzyme many times. Which method is most suitable? A: Covalent binding is renowned for its reusability because the strong covalent bonds prevent enzyme leakage into the reaction mixture over multiple cycles [36] [35]. Similarly, magnetic CLEAs can be easily recovered and reused; their magnetic properties allow for simple separation using a magnet, making them ideal for repeated batch operations [39].

Q3: Why is there often a trade-off between immobilization efficiency and retained enzyme activity? A: This trade-off arises because the chemical modifications and conformational constraints imposed by immobilization can affect the enzyme's active site. If the immobilization process involves residues critical for catalysis, or if it causes steric hindrance that blocks substrate access, activity will drop. The key is to optimize the protocol to stabilize the enzyme without compromising its catalytic machinery [30] [36].

Q4: What are the latest advanced support materials for these techniques? A: Research is focused on nano-supports and smart materials:

- Covalent Binding: Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) and green-synthesized nanoparticles offer high surface area, tunable functionality, and biocompatibility for efficient covalent attachment [34] [39].

- Entrapment/Encapsulation: Composite polymers and silica-based sol-gels provide highly controlled microenvironments [36].

- Cross-Linking: The CLEA technology is being advanced with functionalized magnetic particles to create magnetic CLEAs for easy separation [39].

Q5: How can we control the orientation of an enzyme during covalent binding to preserve activity? A: Advanced strategies involve enzyme engineering. You can genetically introduce specific tags (e.g., His-tags, cysteine residues) at specific locations on the enzyme's surface far from the active site. The support is then functionalized with a complementary reactive group, ensuring a uniform and optimal orientation that minimizes active site obstruction [36] [38].

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Comparison of Key Immobilization Techniques

| Feature | Covalent Binding | Entrapment | Cross-Linking (CLEAs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bond Type | Strong, irreversible covalent bonds [37] | Physical confinement within a lattice [36] | Strong, irreversible covalent bonds between enzyme molecules [39] |

| * Enzyme Leaching* | Very low when optimized [35] | Possible if pore size is too large [36] | Very low [39] |

| Activity Retention | Can be low due to chemical modification [35] | Typically high, as no direct chemical modification occurs [36] | Can be low due to over-cross-linking [39] |

| Reusability | Excellent [35] | Good, but limited by mechanical strength and leakage [36] | Excellent [39] |

| Thermostability | High (rigidifies structure) [37] [35] | Moderate (provides a protective microenvironment) [36] | High (creates a dense, stable aggregate) [39] |

| Cost & Complexity | Moderate to high (cost of activated supports) [35] | Low to moderate [36] | Low (carrier-free, uses precipitant and cross-linker) [39] |

| Best For | Continuous processes requiring extreme stability and no leakage [37] [35] | Sensitive enzymes where chemical modification is detrimental [36] | Cost-effective processes where high enzyme loading and stability are key [39] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Examples

| Immobilization Technique | Enzyme Example | Reported Performance Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Covalent Binding on MOFs | Cellulase | 85% sugar yield from biomass at 50% lower energy input vs. thermal methods [40] |

| Covalent Binding on Nanomaterials | Horseradish Peroxidase | ~60% activity retention after 7 reaction cycles in dye degradation [39] |

| Cross-Linking (CLEAs) | Multi-enzyme (Protease, Lipase, Catalase) | Significant activity retention and improved thermal stability after multiple reuses [39] |

| Cross-Linking (CLEAs) | Xylanase (XY) | 3.39-fold increase in specific activity and a 2.4 °C increase in melting temperature (Tm) [30] |

Experimental Protocol: Preparing Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs)

Principle: Enzymes are first precipitated into physical aggregates, which are then stabilized by cross-linking with bifunctional reagents like glutaraldehyde, forming a carrier-free immobilized biocatalyst [39].

Detailed Methodology:

- Aggregation: Dissolve the purified enzyme in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). Slowly add a precipitant (e.g., ammonium sulfate, polyethylene glycol, or a water-miscible organic solvent like tert-butanol) under gentle stirring until the solution becomes turbid, indicating the formation of enzyme aggregates.

- Cross-Linking: Add a glutaraldehyde solution (typically 0.5% - 5.0% v/v final concentration) to the suspension of aggregates. Continue stirring for a defined period (e.g., 2-24 hours) at a controlled temperature (e.g., 4°C).

- Quenching & Washing: Stop the cross-linking reaction by adding an amino-containing reagent (e.g., glycine) to quench unreacted glutaraldehyde. Recover the CLEAs by centrifugation and wash thoroughly with buffer and then with a dilute buffer or water to remove any unbound enzyme and cross-linker residues.

- Storage: The final CLEA product can be stored as a wet paste at 4°C or lyophilized to a dry powder.

Diagram 1: CLEA preparation workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Immobilization

| Reagent / Material | Function in Immobilization |

|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | A bifunctional cross-linker that reacts primarily with lysine amino groups, forming Schiff bases to create covalent links between enzymes and supports or between enzyme molecules in CLEAs [35] [39]. |

| Carbodiimide (e.g., EDC) | A coupling agent that activates carboxylic acid groups on supports or enzymes, facilitating amide bond formation with primary amines without becoming part of the final bond [37]. |

| Sodium Alginate | A natural polymer used for entrapment and encapsulation; it forms a gel matrix in the presence of divalent cations like calcium (Ca²⁺), physically entrapping enzymes [36]. |

| Chitosan | A biocompatible, cationic polysaccharide used as a support for both adsorption and covalent binding; its amino groups can be easily activated with glutaraldehyde [35]. |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) | Inorganic support with high surface area and tunable pore size, ideal for adsorption and covalent binding, minimizing diffusion limitations [34] [35]. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | A class of highly ordered, porous crystalline polymers that provide an excellent platform for covalent immobilization and in-situ encapsulation due to their designable structures and large surface areas [39]. |

Chemical Modification of Amino Acid Residues

FAQs on Chemical Modification for Enzyme Thermostability

1. Why is chemical modification of amino acids a viable strategy for improving enzyme thermostability? Chemical modification allows for the precise alteration of specific amino acid residues on an enzyme's surface or within its active site. By changing the properties of these residues (e.g., by adding stabilizing groups or increasing hydrophobicity), you can rigidify flexible regions that are prone to unfolding at high temperatures, thereby enhancing kinetic thermostability without necessarily altering the genetic code [41] [42].

2. Which amino acid residues are most commonly targeted for selective chemical modification? Cysteine and lysine are the most frequently targeted residues due to their high nucleophilicity, which allows for selective reaction under biologically ambient, aqueous conditions. Cysteine's low natural abundance (<2% in proteins) often allows for site-selective modification, especially if other native cysteines are mutated away. Lysine, while more abundant, is useful for modifications where multiple conjugations are desired [41].

3. I am concerned about enzyme inactivation when modifying residues near the active site. How can this be avoided? Your concern is valid, as modifications near the active center can impair catalysis. A successful strategy, known as Active Center Stabilization (ACS), involves focusing on flexible residues within approximately 10 Å of the catalytic residue. To avoid inactivation, implement a high-throughput screening protocol that selects for mutants with both improved thermostability and retained high catalytic activity. This ensures that only beneficial modifications are identified [42].

4. What are some common limitations of maleimide-based conjugation to cysteine? While maleimides are popular for cysteine modification, the resulting thioether adduct can be unstable. The conjugate can undergo retro-Michael reactions in the presence of competitive thiols or hydrolysis, leading to decomposition and a mixture of protein products over time. This is a critical consideration for long-term stability studies [41].

5. Beyond cysteine and lysine, are there strategies to modify other residue types? Yes, the chemical toolbox has expanded. For example, transition metal-catalysed reactions, such as rhodium-catalysed modification of cysteine with diazo compounds, have been reported. Furthermore, genetic code expansion allows for the incorporation of unnatural amino acids (UAAs) bearing bio-orthogonal functional groups (e.g., azides or ketones), enabling highly selective chemistry that is impossible with the 20 canonical amino acids [41].

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: Low Selectivity or Multiple Modifications

Symptoms: Heterogeneous reaction products, difficulty in purifying a single conjugate, loss of enzymatic activity.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| High abundance of target residue (e.g., multiple surface lysines). | Use a "harder" electrophile (e.g., activated esters, sulfonyl chlorides) that shows higher selectivity for lysine over cysteine, or switch to a residue with lower natural abundance like cysteine. [41] |

| Insufficiently controlled reaction conditions. | Strictly control pH and temperature. Lower pH can favor cysteine protonation, allowing for more selective lysine modification. Always use ambient, aqueous conditions to preserve protein structure. [41] |

| Non-specific binding of reagents. | Ensure reagents are fresh and properly dissolved. Purify the protein before modification to remove contaminants like amines from buffers that can compete in the reaction. |

Problem 2: Reduced Catalytic Activity After Modification

Symptoms: Modified enzyme shows successful conjugation (e.g., by mass spectrometry) but has significantly lower activity.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Modification of a critical active site residue. | Conduct modification in the presence of a substrate or competitive inhibitor to physically block the active site. Alternatively, use structural data (e.g., B-factor analysis) to target flexible residues near, but not in, the active site for stabilization. [42] |

| The modifying group is causing steric hindrance. | Use a smaller modifying group or a flexible linker to connect the bulky moiety (e.g., PEG). Site-directed mutagenesis can be used to introduce a unique cysteine at a more optimal location on the protein surface. [41] |

| Modification triggers conformational changes. | Characterize the modified enzyme's structure using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy or differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to check for unfolding or destabilization. |

Problem 3: Poor Solubility or Aggregation of Modified Enzyme

Symptoms: Protein precipitation during or after the modification reaction.

| Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Introduction of hydrophobic groups. | If the modification adds hydrophobic moieties, consider switching to a more hydrophilic modifier or ensure the reaction mixture is well-buffered and includes mild chaotropes or stabilizing salts. |