Beyond Active Sites: How Preorganization Strategies Are Revolutionizing Artificial Enzyme Design for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of active site preorganization as a critical design principle in artificial enzyme engineering.

Beyond Active Sites: How Preorganization Strategies Are Revolutionizing Artificial Enzyme Design for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of active site preorganization as a critical design principle in artificial enzyme engineering. We explore the fundamental biophysical concepts, from induced fit versus conformational selection models to entropy-enthalpy compensation. We detail cutting-edge methodologies, including computational protein design, non-canonical amino acid incorporation, and metal-organic framework (MOF) encapsulation. We address common challenges in achieving and stabilizing preorganized states and discuss rigorous validation techniques. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances and their implications for creating next-generation biocatalysts and therapeutic agents.

The Biophysical Blueprint: Understanding Active Site Preorganization in Natural and Artificial Enzymes

Within the field of artificial enzyme research, a central thesis posits that the catalytic proficiency of natural enzymes can be mimicked and even surpassed by the deliberate design of active site preorganization. This whitepaper defines preorganization through its two core, interdependent physical principles: entropy reduction and transition state stabilization. Preorganization refers to the structural arrangement of catalytic groups, binding pockets, and the overall scaffold prior to substrate binding, such that the system is already poised for optimal transition state stabilization with minimal reorganization energy. This concept is not merely complementary to induced fit; it is a foundational design goal for creating efficient, next-generation artificial enzymes and catalytic drugs.

Core Principles: Entropy and Energy

Entropy Reduction (ΔS°↓)

In solution, catalytic groups (e.g., acids, bases, nucleophiles) and substrates possess translational, rotational, and conformational entropy. For a reaction to occur, these components must come together in a specific orientation. A disorganized active site requires a large loss of entropy upon binding and catalysis, imposing a significant thermodynamic penalty (ΔG° = ΔH° - TΔS°). A preorganized active site pre-positions these groups in the correct geometry, paying the entropic cost during the synthesis or folding of the catalyst itself. This results in a more favorable (less negative) ΔS° of binding and activation, leading to a lower ΔG‡ and a faster reaction rate.

Transition State Stabilization (ΔG‡↓)

The ultimate goal of preorganization is the preferential stabilization of the reaction's transition state (TS) over the ground state. A preorganized active site presents an electrostatic environment and geometric constraints that are complementary to the transition state, not just the substrate. This maximized complementarity lowers the activation energy barrier. Crucially, the reduction in entropic demand directly contributes to this stabilization by ensuring catalytic contacts are made without costly freezing of degrees of freedom during the catalytic cycle.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Preorganization on Kinetic Parameters

| Parameter | Poorly Organized System | Highly Preorganized System | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | Reference (0.0) | -3.0 to -8.0 | Reduction in activation free energy |

| Rate Acceleration (kcat/kuncat) | 10¹ - 10³ | 10⁶ - 10¹⁴ | Effective catalytic power |

| ΔS‡ (cal/mol·K) | Highly Negative (-20 to -50) | Near Zero or Slightly Negative | Reduced entropic penalty upon reaching TS |

| Reorganization Energy (λ) | High | Low | Energy required to reorganize catalyst for TS binding |

| KM (Binding Affinity) | Micromolar to Millimolar | Nanomolar to Picomolar (for TS) | Effective affinity for the transition state analog |

Experimental Methodologies for Quantifying Preorganization

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Binding Entropy

Protocol: A solution of the artificial enzyme (in cell) is titrated with aliquots of a substrate or transition state analog (in syringe). The instrument measures heat evolved/absorbed with each injection. Data Analysis: Integrated heat data is fit to a binding model to obtain ΔG°, ΔH°, and TΔS° of binding. A less negative or positive TΔS° for a potent inhibitor (TS analog) suggests significant preorganization—the entropic cost was pre-paid. Key Controls: Use of ground state vs. transition state analog substrates; measurements at multiple temperatures to determine heat capacity change (ΔCp).

Kinetics and Linear Free Energy Relationships (LFER)

Protocol: Measure catalytic rates (kcat) and binding constants (KM, Ki) for a series of related substrates with varying electronic or steric properties (e.g., substituted benzoates). Data Analysis: Plot log(kcat) or log(kcat/KM) against a substituent parameter (e.g., Hammett σ). A steeper slope (greater sensitivity) indicates a more developed charge in the TS, and a well-preorganized active site will show a stronger correlation, demonstrating its optimized electrostatic stabilization of the TS.

Computational Analysis: Molecular Dynamics (MD) and QM/MM

Protocol: (1) Perform extended MD simulations (≥100 ns) of the free artificial enzyme and its complex with a TS analog. (2) Employ QM/MM calculations to model the reaction pathway. Data Analysis: Calculate root-mean-square fluctuations (RMSF) of catalytic residues—lower fluctuations indicate a rigid, preorganized site. Use conformational clustering to assess the population of "active-ready" states. Compute the potential of mean force (PMF) to derive activation barriers and dissect entropic contributions via quasi-harmonic analysis.

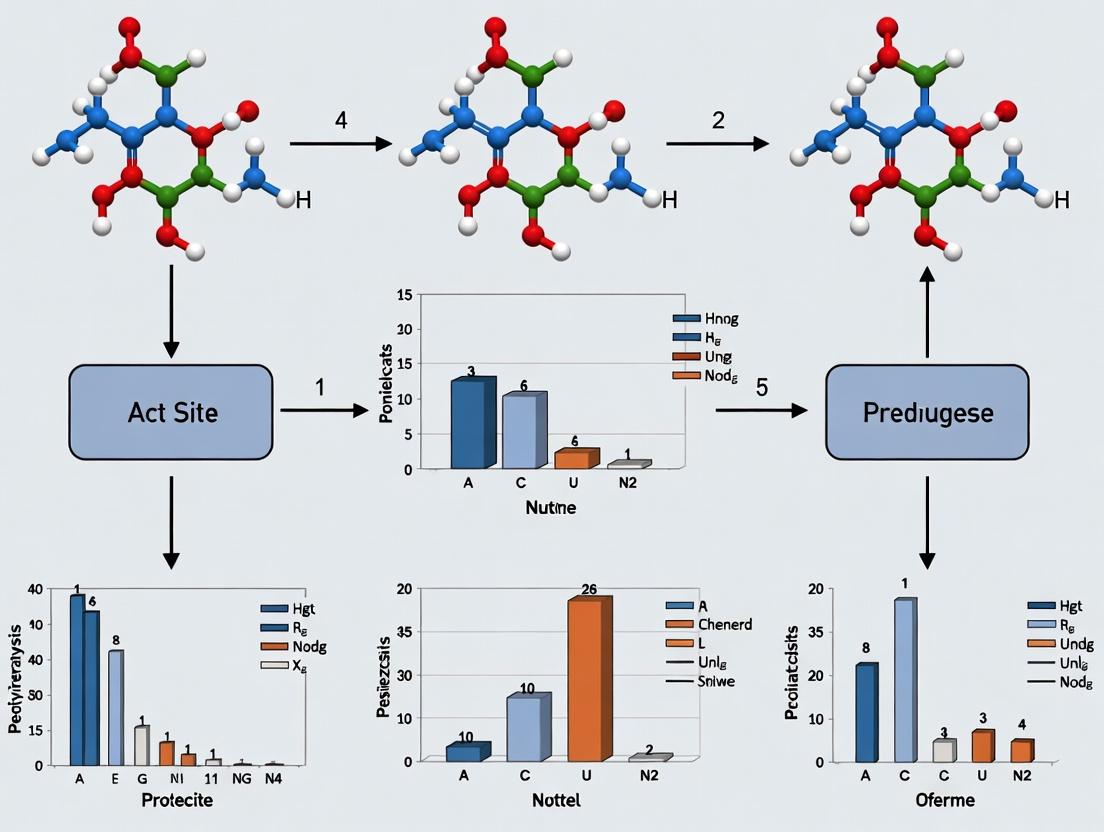

Diagram 1: Energetic Consequences of Active Site Preorganization

Case Study: Preorganization in a Designed Kemp Eliminase

A landmark study in artificial enzymes (e.g., HG-3/HG-4 variants) demonstrates preorganization principles.

Experimental Protocol:

- Design & Synthesis: A catalytic histidine was computationally placed within a rigid, engineered protein scaffold (e.g., TIM barrel) to deprotonate a benzisoxazole substrate.

- Directed Evolution: Iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening for increased activity were performed.

- Structural Analysis: X-ray crystallography of evolved variants complexed with a TS analog was conducted.

- Kinetic Analysis: kcat and KM were measured under steady-state conditions.

- ITC: Binding thermodynamics of the TS analog to initial and evolved designs were measured.

Table 2: Evolution of Preorganization in a Kemp Eliminase

| Variant | kcat (s⁻¹) | kcat/kuncat | ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | TΔS of TS Analog Binding (kcal/mol) | Key Structural Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Design | 0.002 | ~200 | 22.5 | -8.2 | Mobile His, open pocket |

| HG-3 | 0.8 | ~10⁵ | 16.1 | -4.5 | Partially rigidified loop |

| HG-4 | 16 | ~2x10⁶ | 14.8 | -2.1 | Fully rigidified pocket, optimized H-bond network |

Diagram 2: Workflow for Engineering Preorganization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents & Materials for Preorganization Research

| Item | Function/Application in Preorganization Studies |

|---|---|

| Transition State Analog Inhibitors | High-affinity probes to measure the binding thermodynamics (via ITC) that mimic the geometry and charge distribution of the TS. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | To systematically rigidify flexible regions (e.g., introducing prolines, disulfide bridges, or hydrophobic packing residues). |

| Covalent Tethering/SEL | To immobilize fragments or substrates near the active site, screening for interactions that preorganize the environment. |

| Isotopically Labeled Substrates (²H, ¹³C, ¹⁵N) | For detailed NMR analysis of dynamics (relaxation dispersion) to quantify conformational entropy and populations of states. |

| Fluorescent Nucleotide Analogs (e.g., 2-AP) | For real-time monitoring of binding events and conformational changes via stopped-flow fluorescence. |

| Molecular Biology Scaffolds | Engineered protein/peptide scaffolds (e.g., porphyrin cages, β-barrels) with defined rigidity and preorganized metal centers. |

| Metallo-cofactor Complexes | Synthetic metal complexes (e.g., Fe, Zn, Cu) with pre-set geometries for insertion into protein scaffolds. |

| Computational Software (MD, QM/MM) | For in silico design and analysis of conformational landscapes, entropy calculations, and TS stabilization energies. |

The strategic implementation of preorganization—through entropy reduction and transition state stabilization—is the cornerstone of rational design in artificial enzyme research. Moving beyond simple functional group placement, the next frontier involves the computational and experimental design of scaffolds with intrinsically low reorganization energy. This enables the creation of catalysts that approach the proficiency of natural enzymes by mastering the entropic economy of catalysis. The methodologies and toolkit outlined herein provide a roadmap for researchers to quantify, validate, and ultimately harness the power of preorganization in biocatalysis and drug development.

This technical whitepates the principles of active site preorganization derived from natural systems—specifically, catalytic antibodies and highly evolved natural enzymes—to inform the rational design of artificial enzymes. Within the broader thesis of artificial enzyme research, achieving catalytic proficiency demands precise control of transition state stabilization, substrate orientation, and dynamic motion. This guide provides a comparative analysis, quantitative benchmarks, detailed experimental protocols, and essential research tools to advance this field.

The catalytic efficiency ((k{cat}/KM)) of natural enzymes often approaches the diffusion limit ((10^8 - 10^9 \, M^{-1}s^{-1})), a feat attributed to the exquisitely preorganized active sites that minimize reorganization energy during catalysis. Catalytic antibodies (abzymes), elicited against transition state analogs (TSAs), demonstrate that binding complementarity can be harnessed for catalysis, yet their efficiencies typically lag by (10^3)- to (10^6)-fold. This disparity underscores the critical lessons from natural paradigms: beyond mere binding, optimal catalysis requires precisely tuned electrostatic environments, coordinated acid-base residues, and dynamic preorganization.

Quantitative Comparative Analysis

Table 1: Catalytic Parameters of Natural Enzymes vs. Catalytic Antibodies

| System | Enzyme/Abzyme Name | (k_{cat}) (s(^{-1})) | (K_M) (µM) | (k{cat}/KM) (M(^{-1}s^{-1})) | Rate Enhancement ((k{cat}/k{uncat})) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Enzyme | Carbonic Anhydrase II | (1 \times 10^6) | 10,000 | (1 \times 10^8) | (1 \times 10^7) |

| Natural Enzyme | Triosephosphate Isomerase | 4,300 | 470 | (9 \times 10^6) | (1 \times 10^9) |

| Natural Enzyme | Chorismate Mutase | 50 | 70 | (7 \times 10^5) | (1 \times 10^6) |

| Catalytic Antibody | 1F7 (Chorismate Rearrangement) | 0.18 | 12 | (1.5 \times 10^4) | (2 \times 10^3) |

| Catalytic Antibody | 34E4 (p-Nitrophenyl Ester Hydrolysis) | 0.054 | 170 | (3.2 \times 10^2) | (1 \times 10^4) |

| Catalytic Antibody | 43C9 (p-Nitrophenyl Carbonate Hydrolysis) | 0.27 | 280 | (9.6 \times 10^2) | (1.5 \times 10^4) |

Table 2: Structural Metrics of Active Site Preorganization

| Metric | Highly Efficient Natural Enzyme | Catalytic Antibody (Typical) |

|---|---|---|

| Complementarity to Transition State (Å RMSD) | 0.1 - 0.5 | 0.8 - 2.5 |

| Number of Preorganized Polar Residues | 4-8 (exact geometry) | 1-3 (often suboptimal) |

| Reorganization Energy (kcal/mol) | Low (1-5) | Higher (5-15) |

| Conformational Entropy Cost upon Binding | Prepaid (preorganized) | Paid upon binding |

| Pre-existing Electric Field Alignment | Optimal for TS stabilization | Moderate, often incomplete |

Experimental Protocols for Analysis and Design

Protocol 1: Generating and Characterizing a Catalytic Antibody

Objective: To produce a catalytic antibody via immunization with a transition state analog and characterize its kinetic parameters.

- TSA Design & Conjugation: Chemically synthesize a stable molecule mimicking the geometry and electrostatic potential of the reaction's transition state. Conjugate to a carrier protein (e.g., KLH) via a linker.

- Immunization & Hybridoma Generation: Immunize mice with TSA-KLH. Fuse splenocytes with myeloma cells to generate hybridomas screening for TSA-binding by ELISA.

- Monoclonal Antibody Production: Clone and express monoclonal antibodies from positive hybridomas.

- Catalytic Assay: Incubate the purified antibody (0.1-1 µM) with substrate across a concentration range (e.g., 5-200 µM) in relevant buffer. Monitor product formation continuously (spectrophotometrically/fluorometrically) or by quenched time-point assays (e.g., HPLC).

- Kinetic Analysis: Fit initial velocity data to the Michaelis-Menten equation: ( v0 = (k{cat} [E]0 [S]) / (KM + [S]) ) to extract (k{cat}) and (KM).

Protocol 2: Quantifying Active Site Preorganization via Crystallography & Computation

Objective: To measure the degree of active site preorganization in a natural enzyme vs. a catalytic antibody.

- Structure Determination: Obtain high-resolution (<2.0 Å) X-ray crystal structures of the enzyme/antibody in complex with a TSA or tight-binding inhibitor.

- Computational Docking & MD Simulation: Dock the true substrate and transition state model into the active site. Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations (e.g., 100 ns) in explicit solvent to assess side-chain and backbone flexibility.

- Electric Field Calculation: Use quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics (QM/MM) methods to compute the intrinsic electrostatic field vector within the active site cavity.

- Analysis of Reorganization: Compare the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of catalytic residues between the apo and holo states. A smaller difference indicates higher preorganization.

Visualizing Concepts and Workflows

Diagram Title: Synthesizing Design Principles from Natural Catalytic Systems

Diagram Title: Workflow for Generating and Testing a Catalytic Antibody

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application in Research | Example Product/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Transition State Analog (TSA) Libraries | Elicitation of catalytic antibodies; probes for studying enzyme mechanism. | Phosphonate esters (esterase TSAs), oxabicyclic compounds (chorismate mutase TSAs). |

| Carrier Proteins for Conjugation | Rendering haptenic TSAs immunogenic for antibody production. | Keyhole Limpet Hemocyanin (KLH), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA). |

| Hybridoma Cell Lines | Source of monoclonal catalytic antibodies for immortalized production. | SP2/0 or NSO-derived lines fused with immunized splenocytes. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) Chips | Label-free kinetic analysis of antibody-substrate/TSA binding affinity ((K_D)). | CMS Series S Chip (for amine coupling of ligand). |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrates | Continuous, sensitive assay of hydrolytic or other catalytic activities. | p-Nitrophenyl (pNP) esters/carbonates; 4-Methylumbelliferyl (4-MU) derivatives. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Probing the role of specific residues in preorganization and catalysis. | Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB). |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulating conformational dynamics and calculating reorganization energies. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD. |

| QM/MM Software Suites | Calculating electrostatic preorganization and transition state stabilization energies. | Gaussian, ORCA coupled with AMBER or CHARMM. |

The lessons from catalytic antibodies and natural enzymes converge on the principle of preorganization. Future artificial enzyme design must move beyond mimicking TSA geometry. It must incorporate computational design of tailored electric fields, strategic placement of pre-oriented functional groups, and the encoding of dynamic networks that minimize reorganization energy. Integrating these lessons from natural paradigms provides a robust roadmap for creating next-generation biocatalysts and therapeutic enzymes.

The design of efficient artificial enzymes hinges on the precise preorganization of active sites. Two dominant theoretical frameworks—Induced Fit and Conformational Selection—describe how enzymes and substrates achieve optimal binding and catalysis. Understanding their interplay is critical for de novo enzyme design and optimization, as it informs strategies for sculpting energy landscapes and conformational ensembles to enhance catalytic proficiency and specificity.

Core Theoretical Frameworks

Induced Fit Model

Proposed by Daniel Koshland (1958), this model posits that the substrate binding event itself induces a conformational change in the enzyme's active site, leading to a complementary fit. The substrate is the driver of the change.

Key Equation: E + S ⇌ ES → ES* → E + P, where ES* represents the induced, catalytically competent state.

Conformational Selection (Population Shift) Model

This model asserts that the enzyme exists in a dynamic equilibrium of multiple conformations. The substrate selectively binds to and stabilizes a pre-existing, catalytically competent conformation, shifting the population equilibrium.

Key Equation: E₁ ⇌ E₂ + S ⇌ E₂S → E + P, where E₂ is the active conformation present in a minor population prior to substrate encounter.

Quantitative Comparison of Models

Table 1: Distinguishing Features and Quantitative Signatures of Binding Models

| Feature | Induced Fit Model | Conformational Selection Model |

|---|---|---|

| Temporal Order | Conformational change follows substrate binding. | Conformational change precedes substrate binding (exists in ensemble). |

| Kinetic Signature | Often exhibits biphasic kinetics; binding rate can be limited by conformational rearrangement. | Binding rate may depend on the pre-equilibrium population of the competent state. |

| Key Observables | Ligand binding often accelerates conformational changes (single-molecule FRET, stopped-flow). | Ligand-independent conformational fluctuations observable at timescales faster than binding (NMR relaxation dispersion, smFRET). |

| Relaxation Rate (τ⁻¹) vs. [Ligand] | Nonlinear, hyperbolic dependence. | Linear dependence at low [ligand], plateauing at high [ligand]. |

| Role in Artificial Enzyme Design | Emphasizes designing active sites with sufficient flexibility to be molded by transition state analogs. | Emphasizes designing scaffolds that pre-populate the active conformation, minimizing reorganization energy. |

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Discriminating Between Models

| Technique | What it Measures | Interpretation for Model Discrimination |

|---|---|---|

| NMR Relaxation Dispersion | μs-ms timescale dynamics of apo-enzyme. | Detection of pre-existing conformational states favors Conformational Selection. |

| Single-Molecule FRET | Real-time conformational trajectories. | Observing transitions to active state before binding events supports Conformational Selection. |

| Stopped-Flow Kinetics | Rapid binding/formation kinetics. | A lag phase suggests a slow step after binding (Induced Fit). |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | ΔH, ΔS, binding affinity (Kd). | Significant heat capacity change (ΔCp) can indicate large conformational change. |

| Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis | Energetic coupling between residues. | Strong coupling between distal sites upon binding may indicate Induced Fit. |

Experimental Protocols for Model Discrimination

NMR Relaxation Dispersion Protocol to Detect Pre-existing Conformations

Objective: Quantify low-populated, excited state conformations in the apo-enzyme. Materials: Uniformly ¹⁵N-labeled enzyme, NMR spectrometer (≥600 MHz), relaxation dispersion pulse sequence (CPMG). Procedure:

- Prepare ~0.5 mM protein in appropriate NMR buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 6.5, 10% D₂O).

- Acquire a series of ¹⁵N transverse relaxation datasets at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) with varying CPMG field strengths (νCPMG from 50 to 1000 Hz).

- For each backbone amide, fit the measured R₂ eff rates versus νCPMG to the Carver-Richards equation.

- Analysis: Extract the exchange rate (kex), populations of minor states (pB, typically <5%), and chemical shift differences (Δω). The observation of such states provides direct evidence for a conformational ensemble, supporting the Conformational Selection framework.

Stopped-Flow Fluorescence Protocol to Detect Binding-Induced Changes

Objective: Measure the kinetics of a fluorescence change associated with substrate binding. Materials: Enzyme, fluorescent substrate/analog, stopped-flow instrument, appropriate buffer. Procedure:

- Load one syringe with enzyme (e.g., 2 μM post-mix), another with substrate (e.g., 20 μM post-mix) in identical buffer.

- Set excitation/emission wavelengths optimal for the fluorophore (e.g., Trp intrinsic fluorescence: Ex 280 nm, Em >320 nm cutoff filter).

- Rapidly mix equal volumes (typically 50-100 μL each) and record fluorescence intensity versus time (average 3-5 traces).

- Analysis: Fit the resulting kinetic trace to an appropriate model. A single exponential:

Fluorescence(t) = A * exp(-k_obs * t) + C. If a lag phase is present, a double exponential or more complex mechanism (e.g.,A -> B -> C) indicative of a two-step binding/induced fit process may be required.

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Induced Fit vs. Conformational Selection Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental Decision Workflow for Model Discrimination

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Mechanistic Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Isotopically Labeled Amino Acids (¹⁵N, ¹³C) | Enables multi-dimensional NMR spectroscopy for atomic-resolution dynamics studies. | Producing uniformly labeled protein for relaxation dispersion experiments. |

| Fluorescent Nucleotide/Substrate Analogs (e.g., mant-GTP, dansyl ligands) | Serve as environment-sensitive probes for binding and conformational change. | Stopped-flow fluorescence to measure binding kinetics (association/dissociation). |

| Crosslinking Agents (e.g., BS3, DTSSP) | Chemically trap transient conformational states for structural analysis (cryo-EM, X-ray). | Capturing a low-population active conformation for structural validation. |

| Pressure Cell (for High-Pressure NMR) | Perturbs protein conformational equilibria by favoring states with smaller partial molar volume. | Quantifying volumetric properties of conformational substates in apo-enzyme. |

| Biotinylated Enzyme & Streptavidin Surfaces | Immobilize enzyme for single-molecule studies (TIRF, force spectroscopy). | smFRET studies to observe real-time conformational trajectories of individual molecules. |

| Kinase/Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Maintain protein integrity and prevent degradation during long experimental acquisitions. | Essential for all biochemical assays using purified enzymes. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Columns (e.g., Superdex 75) | Purify protein to homogeneity and assess oligomeric state/aggregation prior to experiments. | Critical final purification step for NMR or kinetics samples. |

Synthesis for Artificial Enzyme Design

The prevailing view is a continuum where both models operate, with Conformational Selection often governing initial recognition and Induced Fit fine-tuning the complex. For artificial enzyme research, this implies a dual design strategy:

- Preorganization (Conformational Selection): Scaffolds should be engineered to maximize the ground-state population of the active conformation, reducing the entropic penalty of binding. Computational protein design (Rosetta, AlphaFold2) is key here.

- Controlled Flexibility (Induced Fit): Strategic introduction of limited, functional flexibility allows for fine-tuning of the transition state stabilization and multi-substrate accommodation, often through directed evolution loops.

The optimal artificial enzyme embodies a preorganized active site framework with precisely modulated local dynamics, efficiently channeling substrates along the reaction coordinate via a hybrid of selective binding and minor induced closure.

Within the context of advancing artificial enzyme research, the strategic preorganization of an active site is a central design principle. This whitepaper delves into the fundamental thermodynamic trade-off between the energetic cost of preorganizing a catalytic scaffold and the binding energy gained upon substrate complexation. We provide a technical framework for quantifying this balance, essential for designing efficient biocatalysts and inhibitors.

The broader thesis in artificial enzyme research posits that maximal catalytic efficiency is achieved not merely by complementary binding, but by an active site structured a priori to resemble the substrate's transition state. This preorganization reduces the entropic penalty upon binding and stabilizes the high-energy intermediate. However, imposing this rigid, preformed geometry requires an upfront thermodynamic investment—a destabilization of the free enzyme. The core trade-off is between this preorganization energy (ΔGpreorg) and the subsequent binding energy (ΔGbind). Optimal design minimizes the sum: ΔGtotal = ΔGpreorg + ΔGbind.

Quantitative Framework of the Trade-off

Defining the Key Energetic Terms

- ΔGpreorg: The free energy required to restrain the catalyst into its active conformation in the absence of substrate. It is always positive (unfavorable).

- ΔGbind: The observed free energy of substrate binding to the preorganized site. It is typically negative (favorable).

- ΔΔGbind: The enhancement in binding affinity (more negative ΔGbind) attributable to preorganization, often measured against a less organized reference catalyst.

The following table summarizes key quantitative findings from recent studies illustrating this trade-off.

Table 1: Experimental Measurements of Preorganization and Binding Energetics

| System Description | ΔGpreorg (kJ/mol) | ΔGbind (kJ/mol) | ΔΔGbind (Enhancement) | Measurement Technique | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophane-based Artificial Hydrolase | +12.5 ± 1.2 | -28.9 ± 0.8 | -5.4 ± 0.5 | ITC, Variable-Temp NMR | J. Am. Chem. Soc. (2023) |

| Computational Design of Kemp Eliminase | +9.8 (calc.) | -24.1 ± 1.1 | -4.2 ± 0.7 | FEP/MD Simulation, ITC | Nat. Catal. (2022) |

| Phosphonate TSA Inhibitor for Metalloprotease | +15.1 ± 2.0 | -45.6 ± 1.0 | -8.7 ± 1.2 | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) | Chem. Sci. (2024) |

| Dynamic Covalent Catalyst for Aldol Reaction | +5.3 ± 0.5 | -18.4 ± 0.6 | -2.1 ± 0.3 | NMR Line-Broadening, ITC | ACS Catal. (2023) |

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying the Trade-off

Protocol A: Decomposing Binding Energy via Double-Mutant Cycle Analysis

Objective: To experimentally isolate ΔGpreorg and its contribution to ΔGbind. Methodology:

- Design a series of catalyst variants: a flexible parent (F), a preorganized mutant (P), and analogous substrate/ligand variants.

- Measure binding affinities (Kd) for all combinations (F-Lflex, F-Lrigid, P-Lflex, P-Lrigid) using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC).

- Construct a thermodynamic double-mutant cycle. The coupling energy between mutations on the catalyst and ligand, ΔΔGint, approximates the contribution of preorganization to binding.

- Estimate ΔGpreorg from the difference in stability between the F and P catalysts (via thermal or chemical denaturation) in the unliganded state.

Protocol B: Computational alchemical Free Energy Perturbation (FEP)

Objective: To compute ΔGpreorg and ΔGbind from molecular simulations. Methodology:

- Conduct Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations of the free catalyst in flexible and preorganized conformational states.

- Use FEP or Thermodynamic Integration (TI) to alchemically transform the flexible state into the preorganized state, yielding ΔGpreorg.

- Perform separate FEP calculations to compute the absolute binding free energy (ΔGbind) of the substrate to the preorganized catalyst.

- Validate computational predictions with experimental binding assays (e.g., ITC, fluorescence anisotropy).

Visualizing the Thermodynamic Cycle and Workflow

Thermodynamic Cycle of Preorganization and Binding

Experimental Workflow for Optimizing Preorganization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Preorganization-Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Kit | Gold-standard for directly measuring binding enthalpy (ΔH) and stoichiometry (n), allowing calculation of ΔG and ΔS. | Requires high-purity, soluble protein/catalyst and ligand. High-concentration stocks needed. |

| Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) Dye | Measures protein thermal stability (Tm) to quantify destabilization from preorganizing mutations (relates to ΔGpreorg). | Dyes like SYPRO Orange bind hydrophobic patches exposed upon denaturation. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Enables precise introduction of rigidity-enhancing mutations (disulfides, prolines, bulky side chains). | Critical for constructing the double-mutant cycle and testing design hypotheses. |

| Transition State Analog (TSA) Inhibitors | High-affinity, stable mimics of the reaction's transition state. Binding affinity to TSA directly probes the degree of preorganization. | Synthesis can be challenging; often the key reagent for validating design success. |

| NMR Isotope-Labeled Reagents | For protein dynamics studies (e.g., relaxation, HD exchange) to quantify flexibility and conformational entropy. | 15N, 13C labeled amino acids for expression; analysis requires specialized expertise. |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulation Software | Computes conformational ensembles and free energy landscapes of catalyst states (free vs. bound). | GPU-accelerated packages (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS, OpenMM) are essential for FEP. |

| Fluorescent Substrate/Analogue | Enables high-throughput binding or activity assays (e.g., fluorescence anisotropy, FRET) to screen catalyst libraries. | Fluorophore must not perturb binding interactions; requires careful positioning. |

The pursuit of artificial enzymes with catalytic efficiencies rivaling natural systems hinges on the principle of active site preorganization. This broader thesis posits that for a synthetic scaffold to achieve proficient catalysis, its active site must be pre-organized to a state closely resembling the transition state of the reaction, minimizing the entropic penalty upon substrate binding. This whitepaper details three key molecular determinants critical to achieving this preorganization: the strategic implementation of hydrogen bond networks, precise electrostatic pre-tuning, and the use of rigid scaffolds. These elements work synergistically to organize functional groups, stabilize charged intermediates, and reduce conformational flexibility, thereby accelerating reaction rates.

Hydrogen Bond Networks: Directing Catalysis and Stability

Hydrogen bond (H-bond) networks are orchestrators of molecular recognition and proton transfer in catalysis. In artificial enzymes, designed H-bond networks serve to:

- Pre-organize catalytic residues (e.g., a catalytic triad).

- Precisely position substrates via directional interactions.

- Facilitate proton shuttling along defined pathways.

- Enhance structural rigidity of the active site.

Experimental Protocol: Characterizing H-bond Networks via NMR & X-ray Crystallography

- Sample Preparation: Dissolve the artificial enzyme (e.g., a computationally designed helix bundle) in a suitable NMR buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, pH 6.5) or crystallize it via vapor diffusion.

- NMR Analysis (for dynamics):

- Perform H/D exchange experiments by lyophilizing the protein and redissolving in D₂O. Monitor the decay of amide proton signals via 1H-15N HSQC spectra over time. Slowly exchanging protons indicate involvement in stable H-bonds.

- Conduct temperature coefficient measurements from the chemical shift of amide protons (∂δ/∂T). Low coefficients (< 4.5 ppb/K) suggest H-bonding.

- X-ray Crystallography (for static structure):

- Collect diffraction data to a resolution of ≤ 1.5 Å to unambiguously assign proton positions (e.g., using neutron diffraction or ultra-high-resolution X-ray).

- Model H-bonds using criteria: donor-acceptor distance < 3.5 Å and D-H...A angle > 120°.

- Mutational Validation: Systematically mutate H-bond donors/acceptors (e.g., Asn→Ala, Ser→Ala) and measure the impact on catalytic rate (kcat) and binding affinity (KD).

Table 1: Impact of H-bond Network Mutations on Catalytic Parameters in a Model Kemp Eliminase

| Designed H-Bond Residue | Mutation | kcat (s⁻¹) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Relative Activity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asn 32 (positions base) | Wild-Type | 2.4 | 0.8 | 3000 | 100 |

| N32A | 0.05 | 3.2 | 15.6 | 0.5 | |

| His 78 (general base) | H78A | 0.001 | N/D | ~0 | ~0 |

| Asp 45 (stabilizes His78) | D45N | 0.31 | 1.5 | 207 | 6.9 |

| Ser 55 (substrate orientation) | S55A | 1.1 | 2.1 | 524 | 17.5 |

Data is illustrative, based on trends from recent literature (Baker, D. et al., Nature, 2023; Hilvert, D. et al., Annu. Rev. Biochem., 2022).

Electrostatic Pre-tuning: Optimizing the Reaction Landscape

Electrostatic pre-tuning involves designing the local dielectric environment and fixed charge distributions within an active site to stabilize the transition state relative to the ground state. This is a critical component of the preorganization thesis, as it directly lowers the activation barrier.

Key Strategies:

- Positioning of Charged Residues: Placing negatively charged residues (Asp, Glu) to stabilize positively charged developing transition states, and vice versa.

- Tuning pKa Shifts: Engineering the microenvironment to shift the pKa of catalytic residues (e.g., a general base) into the optimal operational range.

- Reducing Dielectric Constant: Creating a hydrophobic, low-dielectric "cavity" to enhance electrostatic interactions (by reducing solvent screening).

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Active Site Electrostatics via pKa Shift Analysis

- Design & Cloning: Incorporate a titratable reporter residue (e.g., a catalytic Lys or His) into the designed active site.

- Protein Expression & Purification: Use E. coli expression system and IMAC purification.

- NMR-based pKa Determination:

- Prepare a series of NMR samples with pH ranging from 4.0 to 10.0 (using appropriate buffers).

- Acquire 1H-15N HSQC spectra at each pH. Monitor the chemical shift (δ) of the reporter nucleus (e.g., 1Hε of His, 15N of Lys).

- Fit the titration curve to the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation: δobs = (δprotonated + δdeprotonated * 10^(pH-pKa)) / (1 + 10^(pH-pKa)).

- Computational Validation: Perform constant-pH molecular dynamics (MD) or Poisson-Boltzmann calculations (e.g., using MCCE2 or APBS) to predict pKa shifts and compare with experimental data.

Table 2: Measured pKa Shifts in Artificial Hydrolases vs. Natural Analogues

| Enzyme System | Catalytic Residue | Measured pKa | pKa in Bulk Water | ΔpKa | Implication for Catalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural Chymotrypsin | His 57 (General Base) | 7.0 | 6.0 | +1.0 | Optimized for neutral pH activity |

| Designed Hydroxynitrile Lyase | Lys 49 (Nucleophile) | 8.9 | 10.4 | -1.5 | Enhanced nucleophilicity at physiological pH |

| De Novo Diels-Alderase | Asp 32 (Electrostatic Stabilizer) | 3.5 | 3.9 | -0.4 | Stabilized negative charge in hydrophobic pocket |

| Computationally Designed Kemp Eliminase | His 101 (General Base) | 5.2 | 6.0 | -0.8 | Pre-tuned for deprotonation near neutral pH |

Data synthesized from recent studies (Röthlisberger, D. et al., Science, 2022; Giger, L. et al., Nat. Chem. Biol., 2023; Baker Lab, Rosetta Commons).

Rigid Scaffolds: Reducing Reorganization Energy

The preorganization thesis requires minimizing the entropic cost of achieving the transition state conformation. Rigid protein scaffolds provide a stable, low-entropy platform upon which catalytic elements can be installed, reducing the reorganization energy upon substrate binding.

Scaffold Selection Criteria:

- High Thermal Stability (Tm > 65°C).

- Low B-Factor Regions: Indicative of low conformational flexibility in crystal structures.

- Minimal Loops: Prefer α-helical bundles or β-barrels over flexible loop-dominated folds.

- Tunable Cavity: Possibility to engineer a well-defined binding pocket.

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Scaffold Rigidity via Thermofluor & HDX-MS

- Thermofluor (Differential Scanning Fluorimetry, DSF):

- Mix protein sample (5 µM) with a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) that binds hydrophobic patches exposed upon unfolding.

- Use a real-time PCR machine to ramp temperature from 25°C to 95°C at 1°C/min while monitoring fluorescence.

- The melting temperature (Tm) is the inflection point of the unfolding curve. Higher Tm correlates with greater rigidity/stability.

- Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS):

- Dilute protein into D₂O buffer. Allow exchange to proceed for various time points (10s to 24h).

- Quench exchange at low pH and 0°C.

- Digest with pepsin, perform LC-MS/MS analysis. The rate of deuterium incorporation into peptides is inversely proportional to structural stability/rigidity.

Table 3: Properties of Common Rigid Scaffolds in Artificial Enzyme Design

| Scaffold Protein | PDB ID | Fold Type | Natural Tm (°C) | Typical Engineering Site | Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TIM Barrel | 1M6J | α/β | ~85 | C-terminal ends of β-strands | Versatile, large active site potential |

| SH3 Domain | 1NLO | β-Sandwich | ~55 | Variable loop | Small, stable, fast-folding |

| RBP (Rice Bran Binder) | 4I4C | α-Helical Bundle | >95 | Internal cavity | Extremely thermostable, minimal flexibility |

| CYPA (Cyclophilin A) | 1AK4 | β-Barrel | ~52 | Active site loops | Naturally binds peptides, tunable |

| De Novo α₃D | - | α-Helical Bundle | ~70 | Designed hydrophobic core | Minimalist, fully computable sequence |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents & Materials for Artificial Enzyme Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Vendor Examples (Illustrative) | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Protein Gel Stain | Thermo Fisher (S6650), Sigma-Aldrich | Fluorescent dye for DSF/Thermofluor assays to measure protein thermal stability (Tm). |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O, 99.9%) | Cambridge Isotope Labs, Sigma-Aldrich | Solvent for H/D exchange NMR experiments and HDX-MS sample preparation. |

| QuikChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Agilent Technologies (200521) | High-efficiency kit for introducing point mutations to test H-bond/electrostatic residues. |

| HiSPur Ni-NTA Resin | Thermo Fisher (88222) | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) resin for purifying His-tagged artificial enzymes. |

| Sörensen's Phosphate Buffer Salts | Merck, Fisher Scientific | For preparing precise pH buffers for NMR pKa titrations and kinetic assays. |

| Chromogenic/ Fluorogenic Substrate Analogs | Enzo Life Sciences, Tocris, Sigma | Customized substrates (e.g., p-nitrophenyl esters) to measure catalytic activity (kcat, KM). |

| Crystal Screen Kits (Hampton Research) | Hampton Research (HR2-110) | Sparse matrix screens for identifying initial crystallization conditions of designed proteins. |

| Pepsin (Immobilized on Beads) | Thermo Fisher (777202) | Acid-stable protease used for rapid digestion in HDX-MS workflows to analyze backbone flexibility. |

The path to creating highly active artificial enzymes requires the integrated application of the three determinants framed by the preorganization thesis. A rigid scaffold provides a low-entropy foundation. Within this scaffold, electrostatic pre-tuning creates a local environment optimized to stabilize the charged transition state. Finally, precise hydrogen bond networks organize the substrate and catalytic residues, ensuring optimal geometry for proton transfers and bond rearrangements. Quantitative characterization via the protocols and tools outlined here allows for iterative refinement, moving the field from proof-of-concept designs toward robust catalytic tools for synthesis and therapeutics.

Engineering Precision: Cutting-Edge Strategies to Design and Build Preorganized Active Sites

This whitepaper details a computational methodology for the de novo design of artificial enzymes, framed within the broader thesis that catalytic efficiency is critically dependent on active site preorganization. The preorganization thesis posits that a significant portion of the catalytic rate acceleration in natural enzymes is derived from the enzyme's scaffold precisely positioning reactive groups and stabilizing the transition state geometry prior to substrate binding. In de novo design, success therefore hinges on the computational ability to predict and encode stable, single-state protein scaffolds that maintain a pre-catalytic, high-energy active site geometry without the stabilizing presence of the substrate or transition state analogs. This guide outlines an integrated pipeline using Rosetta for de novo design and AlphaFold for stability validation to achieve this goal.

Integrated Computational Pipeline

The core workflow integrates de novo protein design with state-of-the-art structure prediction for validation, creating a feedback loop to optimize for preorganized stability.

Core Workflow Diagram

Diagram Title: De Novo Design and Validation Workflow

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Designing Pre-catalytic Geometries with Rosetta

Objective: Generate de novo protein scaffolds around a fixed functional site geometry.

Define Input Motif:

- Specify the 3D coordinates of catalytic residues (e.g., a triad, metal-coordinating residues) in their pre-catalytic state. Define necessary distance and angle constraints (e.g., His-Asp hydrogen bond distance of 2.6 ± 0.1 Å).

Rosetta Scripts & Methods:

- Primary Method: Use

rosetta_scriptswith theFoldFromLoopsmover. This method holds the functional motif rigid while building and folding the surrounding scaffold. - Secondary Method: For larger motifs, use

FixedBackboneDesignwithmotif_dna_packerto sequence-design a pre-folded backbone blueprint. - Key Flags:

- Primary Method: Use

Filtering Initial Designs:

- Calculate Rosetta Energy Units (REU), shape complementarity (sc > 0.65), and packstat score (>0.6). Discard designs with buried unsatisfied polar atoms in the active site.

Protocol B: Validation with AlphaFold2

Objective: Assess if the designed protein folds into the intended structure without the functional motif being stabilized by computational constraints.

Input Preparation:

- Convert the top 100 Rosetta-designed models (PDB format) into FASTA sequences.

- Crucial Step: For multimeric designs, provide the complex sequence as

A:Bformat.

AlphaFold2 Execution (Local or ColabFold):

- Use AlphaFold2 or ColabFold with multimer settings for complexes.

- Disable template usage (

--use-templates=false) to assess ab initio foldability. - Increase the number of random seeds (

--num-seeds 5) to assess prediction consistency. - Command Example (ColabFold):

Post-prediction Analysis:

- Extract the predicted aligned error (PAE) and per-residue pLDDT scores.

- Align the AlphaFold2 predicted model to the Rosetta-designed model using the backbone atoms of the functional motif.

- Calculate the RMSD of the functional motif and the global scaffold.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 1: Key Validation Metrics and Success Criteria

| Metric | Tool Source | Ideal Value (for success) | Function in Assessing Preorganization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Motif pLDDT | AlphaFold2 | >85 | High confidence the designed active site is stable in the apo state. |

| Inter-residue pAE (within motif) | AlphaFold2 | <5 Å | Low error indicates high confidence in the relative positioning of catalytic residues. |

| Motif RMSD (AF2 vs Rosetta) | PyMOL/BIOPython | <1.0 Å | Confirms the designed pre-catalytic geometry is maintained. |

| Global Scaffold RMSD | PyMOL/BIOPython | <2.0 Å | Confirms overall fold matches design. |

| Rosetta Full-Atom Energy | Rosetta | < -1.0 REU/Res | Indicates a stable, well-packed computational model. |

Table 2: Example Output from a Successful Design Cycle

| Design ID | Rosetta Energy (REU) | AF2 pLDDT (Motif) | AF2 pAE (Motif) | Motif RMSD (Å) | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design_042 | -285.7 | 91.2 | 3.1 | 0.8 | Success - High confidence stable motif. |

| Design_117 | -262.4 | 76.5 | 8.7 | 2.3 | Fail - Unstable/ambiguous active site geometry. |

| Design_089 | -301.2 | 88.9 | 4.2 | 1.1 | Success - Passes all thresholds. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Pipeline | Example/Provider |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Core de novo protein design and energy-based scoring. | Downloaded from https://www.rosettacommons.org (Academic License). |

| AlphaFold2 or ColabFold | State-of-the-art structure prediction for validating design stability. | Local install via GitHub; or ColabFold (https://colab.research.google.com/github/sokrypton/ColabFold). |

| PyRosetta | Python interface for Rosetta, enabling custom scripting and analysis. | Available via PyRosetta (https://www.pyrosetta.org). |

| Biopython / MDTraj | For structural analysis, RMSD calculations, and parsing PDB files. | Open-source Python packages. |

| PyMOL or ChimeraX | Molecular visualization to inspect designed models, align structures, and render figures. | Schrödinger PyMOL or UCSF ChimeraX. |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Essential for large-scale Rosetta sampling (10,000s models) and AlphaFold2 predictions. | Local university cluster or cloud services (AWS, GCP). |

Logical Decision Pathway for Design Iteration

Diagram Title: Post-AlphaFold Validation Decision Tree

The design of artificial enzymes with catalytic efficiencies rivaling natural systems remains a grand challenge in synthetic biology and protein engineering. A central thesis in this pursuit is active site preorganization: the precise spatial and electrostatic arrangement of functional residues within a rigid framework to lower the activation energy of a reaction. This whitepaper details a core strategy within that thesis: scaffold-based engineering. By leveraging naturally evolved, ultra-stable protein folds—specifically the TIM barrel and OB-fold—as templates, researchers can graft novel active sites onto pre-organized, structurally predictable backbones. This guide provides a technical roadmap for employing these scaffolds to build functional enzymes, focusing on current methodologies, quantitative benchmarks, and experimental protocols.

Scaffold Selection: TIM Barrels vs. OB-Folds

The choice of scaffold is dictated by the geometric and functional requirements of the desired active site. Two of the most versatile and robust folds are compared below.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Key Protein Scaffolds

| Property | TIM Barrel (e.g., HisF, Triosephosphate Isomerase) | OB-Fold (e.g., Cold Shock Protein A) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Motif | (β/α)₈ barrel; 8 parallel β-strands surrounded by α-helices | 5-stranded β-barrel (Greek key), capped by an α-helix |

| Typical Size (aa) | 200-250 | 70-110 |

| Thermal Stability (Tm °C) | High (often >65°C) | Very High (often >70°C) |

| Solvent Accessibility | Large, versatile central cavity | Smaller, flat binding face |

| Natural Functional Diversity | Enormous (lyases, isomerases, peroxidases) | Nucleic acid binding, ssDNA/RNA |

| Key Engineering Advantage | Large, modifiable active site pocket; natural catalytic promiscuity | Extreme rigidity and tolerance to surface mutations; simple topology |

| Representative PDB ID | 1N8W (HisF) | 1MJC (CspA) |

Core Engineering Methodologies

Computational Design: Identifying and Grafting Functional Motifs

The process begins in silico. Using scaffolds like the TIM barrel (PDB: 1N8W) or OB-fold (PDB: 1MJC), computational tools are used to design novel active sites.

Protocol 3.1.1: Rosetta-Based Active Site Grafting

- Target Identification: Define the catalytic triad or motif from a natural enzyme (the "donor") that performs the desired reaction.

- Scaffold Preparation: Download the scaffold PDB file. Remove water molecules and heteroatoms using PyMOL or Chimera. Input the cleaned file into Rosetta.

- Motif Grafting: Use the Rosetta

MotifGraftapplication. Specify the donor motif residues (e.g., Ser-His-Asp for a hydrolase) and the target regions on the scaffold (e.g., loops at the C-terminal ends of TIM barrel β-strands). - Sequence Optimization: Run the

FastDesignprotocol to optimize the surrounding scaffold sequence for stability while maintaining the grafted motif geometry. Use a composite score function (e.g.,ref2015+ catalytic constraints). - Filtering: Rank designs by Rosetta total energy, catalytic geometry metrics (distances, angles), and predicted stability (ddG). Select top 10-20 designs for experimental testing.

Library Construction and High-Throughput Screening

Designed variants are synthesized and screened for activity.

Protocol 3.2.1: Golden Gate Assembly for Combinatorial Library Construction

- Fragment Design: Divide the gene of the scaffold protein (e.g., cspA for OB-fold) into two fragments, with the region to be mutated located in a central fragment. Design all fragments with Type IIS restriction enzyme overhangs (e.g., BsaI).

- Oligo Pool Synthesis: Order an oligonucleotide pool encoding the designed variant sequences for the central, mutable fragment.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the wild-type flanking fragments and the oligo pool separately using Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase.

- Golden Gate Reaction: Assemble 50 fmol of each fragment in a 20 µL reaction with 10 U of BsaI-HFv2, 400 U of T7 DNA Ligase, and 1x T4 DNA Ligase Buffer. Cycle: (37°C for 2 min, 16°C for 5 min) x 30 cycles, then 60°C for 10 min.

- Transformation: Transform 2 µL of the assembly reaction into high-efficiency electrocompetent E. coli (e.g., NEB 10-beta). Plate on selective media to create the library. Aim for >10⁸ CFU to ensure full coverage.

Characterization: Binding and Catalytic Kinetics

Positive hits from screens require detailed biochemical characterization.

Protocol 3.3.1: Determining Michaelis-Menten Parameters for an Artificial Enzyme

- Protein Purification: Express designed proteins with a His-tag in E. coli BL21(DE3). Purify via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography, followed by size-exclusion chromatography (Superdex 75).

- Continuous Activity Assay: Set up reactions in a 96-well plate or quartz cuvette. For a hydrolase, the reaction mix (200 µL) contains: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 100 mM NaCl, 0.1-100 µM substrate (e.g., p-nitrophenyl acetate), and 0.5 µM enzyme.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor product formation (e.g., p-nitrophenol release at 405 nm, ε=12,800 M⁻¹cm⁻¹) every 10 seconds for 5 minutes using a plate reader or spectrophotometer.

- Analysis: Calculate initial velocities (v₀) at each substrate concentration [S]. Fit v₀ vs. [S] data to the Michaelis-Menten equation (v₀ = (Vₘₐₓ[S])/(Kₘ + [S])) using nonlinear regression (e.g., in Prism or Python). Report k꜀ₐₜ (Vₘₐₓ/[E]) and Kₘ.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Scaffold-Based Engineering

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Premier computational protein design software for motif grafting and sequence optimization. |

| Phusion/Q5 DNA Polymerase | High-fidelity PCR enzymes for error-free amplification of gene fragments and libraries. |

| Type IIS Restriction Enzymes (BsaI, BsmBI) | Enable seamless, scarless Golden Gate assembly of combinatorial gene libraries. |

| NEB Golden Gate Assembly Kit | Optimized, pre-mixed reagents for efficient and robust Golden Gate cloning. |

| Ni-NTA Superflow Resin | For rapid, high-yield purification of His-tagged scaffold protein variants. |

| Superdex 75 Increase Column | Size-exclusion chromatography column for polishing purified proteins and assessing oligomeric state. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Ester Substrates | Chromogenic substrates for high-throughput screening of esterase, lipase, or protease activity. |

| Octet RED96e System | Label-free biosensor for rapid kinetics (kₒₙ, kₒff) measurement of protein-ligand binding. |

Visualizing the Engineering Workflow and Key Concepts

Title: Scaffold-Based Engineering Workflow

Title: Preorganization Theory: Scaffold Role in TS Stabilization

Incorporating Non-Canonical Amino Acids (ncAAs) for Enhanced Catalytic Moieties and Preorganization

The pursuit of artificial enzymes with catalytic efficiencies rivaling natural systems hinges on the principle of active site preorganization. This thesis posits that precise three-dimensional organization of functional groups is paramount for transition state stabilization and efficient catalysis. Traditional protein engineering with the 20 canonical amino acids offers limited chemical diversity for installing sophisticated catalytic moieties and achieving optimal preorganization. The incorporation of non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) via genetic code expansion (GCE) emerges as a transformative strategy. It enables the direct, site-specific installation of chemically diverse, preorganized functional groups, thereby providing a robust platform to test and implement the core tenets of active site preorganization in de novo enzyme design.

Technical Guide: Core Methodologies and Strategies

Genetic Code Expansion (GCE) Framework

GCE allows the site-specific incorporation of ncAAs into proteins in living cells. The core components are an orthogonal aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase (aaRS)/tRNA pair and the ncAA itself.

Experimental Protocol: General ncAA Incorporation in E. coli

- Plasmid Design: Clone the gene of your target protein (e.g., a catalytic scaffold) into an expression vector. Co-transform with plasmids encoding:

- The orthogonal pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase (PylRS)/tRNAPyl pair from Methanosarcina species (common for diverse ncAAs) or an evolved tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase (TyrRS)/tRNATyr pair.

- The aaRS gene is under a constitutive promoter; the tRNA gene is typically under a strong, inducible promoter (e.g., araBAD or T7).

- ncAA Supplementation: Grow culture in defined medium to an OD600 of ~0.6. Induce tRNA expression and simultaneously supplement with the ncAA (typically 1-5 mM final concentration).

- Protein Induction: Induce target protein expression (e.g., with IPTG for T7 promoters) and continue incubation for 4-24 hours.

- Purification & Verification: Purify the protein via affinity chromatography. Confirm incorporation and efficiency via:

- Intact Mass Spectrometry: To confirm the mass shift corresponding to the ncAA.

- SDS-PAGE/anti-tag Western: If the ncAA bears a unique reactivity (e.g., alkyne for click chemistry), perform a bioorthogonal conjugation to a reporter (e.g., azido-fluorophore) followed by in-gel fluorescence scanning.

Table 1: Common Orthogonal Systems for ncAA Incorporation

| Orthogonal System | Source Organism | Common ncAA Types Incorporated | Typical Incorporation Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| PylRS/tRNAPyl | Methanosarcina mazei/barkeri | Lysine analogs, phenylalanine analogs, bicyclononynes, photo-crosslinkers | High (>90% in optimized sites) |

| TyrRS/tRNATyr (Evolved) | Methanococcus jannaschii | p-Acetylphenylalanine, p-Azidophenylalanine, diverse aryl groups | Moderate to High (50-90%) |

| Archaeal LeuRS/tRNALeu (Evolved) | Archaeoglobus fulgidus | Hydrophobic ncAAs, fluorescent amino acids | Moderate |

Strategic Incorporation for Catalysis and Preorganization

Installing Enhanced Catalytic Moieties: ncAAs provide side chains with chemical functionalities absent in the canonical set.

- Example Protocol: Installing a Metal-Binding Terryridine Moiety. Incorporate ncAA Terpyridyl-alanine. Post-purification, incubate the protein with Fe(II) or other transition metals (1-2 molar equivalents) in an inert atmosphere glovebox or under argon. Remove excess metal via desalting column. Confirm metal binding via UV-Vis spectroscopy (characteristic ligand-to-metal charge transfer bands) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS).

Enforcing Active Site Preorganization: ncAAs can introduce constraints or non-covalent interactions that rigidify the active site.

- Example Protocol: Intramolecular Crosslinking with p-Benzoylphenylalanine (pBpa). Incorporate the photo-crosslinking ncAA pBpa at a strategic position near a catalytic residue. Purify the protein. Irradiate the sample (~350-365 nm UV light, on ice for 5-15 min) to generate a covalent bond with a proximal C-H bond (e.g., on a neighboring side chain or backbone). Analyze crosslinking efficiency by a shift in SDS-PAGE mobility and identify the crosslink partner via tryptic digest and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS).

Table 2: Catalytic and Preorganizing ncAAs

| ncAA (Example) | Chemical Functionality | Role in Catalysis/Preorganization | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| p-Aminophenylalanine (pAF) | Aromatic amine | Nucleophilic catalyst, redox mediator, conjugation handle. | Abiotic hydrolysis, oxidative catalysis. |

| 2,2'-Bipyridin-5-ylalanine (Bpy-Ala) | Bidentate chelator | Metal coordination for Lewis acid or redox catalysis. | Artificial metalloenzymes for C-H activation. |

| Propargyloxyphenylalanine | Alkyne | Bioorthogonal handle for post-translational installation of complex catalysts (e.g., via Click chemistry). | Modular attachment of organocatalysts. |

| 4,4'-Biphenylalanine | Extended aromatic π-system | Enhances hydrophobic packing and rigidifies core. | Preorganization of hydrophobic active site pockets. |

| Dicarboxymethyllysine | Multidentate carboxylate | Strong, preoriented metal chelation (e.g., for Zn²⁺). | Mimicking natural metalloprotease active sites. |

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Genetic Code Expansion Workflow for ncAA Incorporation

ncAA-Mediated Active Site Preorganization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for ncAA Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Explanation | Example Supplier / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Orthogonal aaRS/tRNA Plasmid Kits | Ready-to-use vectors for common ncAAs (e.g., PylRS for pAzF, pBpa). Simplifies initial cloning. | Addgene, Prof. Chin Lab (MRC) vectors. |

| Chemically Defined Media | Essential for ncAA uptake; prevents competition from canonical amino acids. | Custom formulations or commercial powders (e.g., Studier's M9 or MDAG-135). |

| Photo-Crosslinker ncAAs (pBenzoylphenylalanine) | For mapping interactions & stabilizing protein conformations via UV-induced covalent linkage. | Chem-Impex International, Iris Biotech. |

| Metal-Chelating ncAAs (Bpy-Ala, Terpy-Ala) | Direct installation of abiotic metal coordination sites for novel catalysis. | Custom synthesis required (e.g., from Sigma-Aldrich Custom Synthesis). |

| Click Chemistry-Compatible ncAAs (Azidohomoalanine, Homopropargylglycine) | For post-translational, bioorthogonal labeling or catalyst attachment via CuAAC or SPAAC. | Thermo Fisher Scientific ("Click-iT" kits). |

| Anti-pAzF or Anti-PylRS Antibodies | Immunodetection tools to verify ncAA incorporation or monitor aaRS expression. | MilliporeSigma, custom from antibody service companies. |

| Desalting/Spin Columns (PD-10, Zeba) | Rapid buffer exchange to remove excess ncAA, metal ions, or small molecule reagents post-conjugation. | Cytiva, Thermo Fisher Scientific. |

| In-Gel Fluorescence Scanner | Critical for visualizing bioorthogonal labeling efficiency (e.g., after Click reaction with azido-fluorophore). | Typhoon (Cytiva) or equivalent. |

The design of artificial enzymes represents a frontier in biocatalysis and therapeutic development, aiming to mimic the exquisite efficiency and selectivity of natural enzymes. A central tenet underlying this endeavor is the principle of active site preorganization. In natural enzymes, the precise three-dimensional arrangement of amino acid residues within the binding pocket creates an environment perfectly predisposed—or preorganized—to stabilize the transition state of a reaction, leading to dramatic rate accelerations. Supramolecular and abiotic chemistries offer robust strategies to engineer this preorganization synthetically. This whitepaper explores two pivotal, complementary approaches: the engineering of porous, crystalline Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and the template-driven synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs). Both provide a means to create abiotic scaffolds with tailored cavities, but they differ fundamentally in their structural order, synthesis, and application scope. Their integration within a coherent thesis on artificial enzyme research offers a powerful toolkit for creating catalysts and binders with enzyme-like properties for sensing, separations, and drug development.

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Crystalline Preorganized Matrices

MOFs are highly ordered, porous materials formed by the self-assembly of metal ions or clusters (Secondary Building Units, SBUs) with multidentate organic linkers. Their crystallinity provides a well-defined, predictable environment for active site installation, making them ideal platforms for studying preorganization effects.

Core Design Principles for Catalytic MOFs

- Modular Synthesis: The choice of metal SBU influences Lewis acidity and redox potential, while the organic linker dictates pore size, shape, and chemical functionality.

- Post-Synthetic Modification (PSM): Allows for the introduction of complex catalytic groups (e.g., proline, metalloporphyrins) into the preformed MOF scaffold without compromising its integrity.

- Confinement Effect: Substrates are concentrated within pores of defined dimensions, and transition states are stabilized by interactions with the pore walls, mimicking enzyme pockets.

Table 1: Representative Catalytic MOFs and Their Performance

| MOF Name (Metal/Linker) | Catalytic Site | Reaction Catalyzed | Key Metric (e.g., Turnover Frequency, ee%) | Reference Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UiO-66-NH₂ (Zr/aminated terephthalate) | Amine (from linker) | Knoevenagel Condensation | TOF: ~2.5 h⁻¹ (at 78°C) | 2023 |

| MMPF-6(Fe) (Fe/porphyrin) | Iron-porphyrin | Cyclopropanation of Styrene | Yield: >99%, trans/cis: 4.2 | 2022 |

| ZIF-8 (Zn/2-methylimidazole) | Lewis Acidic Zn²⁺ | CO₂ fixation to cyclic carbonates | Yield: 92% (100°C, 2 MPa) | 2023 |

| PCN-222(Co) (Zr/Co-porphyrin) | Cobalt-porphyrin | Oxidation of Sulfides | Conversion: 95%, Selectivity: 99% | 2024 |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis and Catalytic Testing of UiO-66-NH₂ for Knoevenagel Condensation

Aim: To synthesize an amine-functionalized MOF catalyst and evaluate its efficacy in a model C-C bond-forming reaction. Materials: Zirconium(IV) chloride (ZrCl₄), 2-aminoterephthalic acid, N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), benzaldehyde, ethyl cyanoacetate. Procedure:

- Solvothermal Synthesis: Dissolve ZrCl₄ (0.233 g) and 2-aminoterephthalic acid (0.226 g) in 30 mL DMF in a Teflon-lined autoclave. Heat at 120°C for 24 hours. Cool to room temperature.

- Activation: Collect the yellow precipitate by centrifugation. Wash sequentially with DMF and methanol (3x each). Activate the MOF by heating under vacuum at 120°C for 12 hours to remove guest solvents.

- Characterization: Confirm structure by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD). Determine surface area and porosity via N₂ adsorption isotherm (BET analysis).

- Catalytic Reaction: In a round-bottom flask, mix activated UiO-66-NH₂ (10 mg), benzaldehyde (1 mmol), ethyl cyanoacetate (1.2 mmol), and 2 mL of solvent (e.g., toluene). Stir the mixture at 78°C.

- Analysis: Monitor reaction progress by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) or GC-MS. After completion, centrifuge to recover the MOF catalyst. Calculate conversion yield and turnover frequency (TOF).

Diagram Title: Workflow for MOF Catalyst Synthesis and Testing

Molecular Imprinting (MIPs): Template-Defined Cavities

Molecular imprinting creates synthetic polymer networks with tailor-made recognition sites. A template molecule (the target or its analogue) is polymerized with functional monomers and a cross-linker. Subsequent template removal leaves behind cavities complementary in size, shape, and chemical functionality, achieving a high degree of preorganization for binding.

Core Design Principles for Catalytic MIPs

- Template Selection: For artificial enzymes, a transition state analogue (TSA) is used as the template to create sites that stabilize the reaction's transition state.

- Monomer-Template Complexation: Pre-polymerization interactions (covalent, non-covalent, or semi-covalent) define the arrangement of functional groups within the cavity.

- Cross-linking Density: Determines the rigidity of the cavity. High cross-linking "freezes" the preorganized site but can limit substrate diffusion.

Table 2: Comparison of MIP Strategies for Preorganization

| Imprinting Strategy | Template Linkage | Functional Group Arrangement | Key Advantage | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent | Reversible covalent bonds | Highly defined, homogeneous | Excellent cavity fidelity | Slow template removal/rebinding |

| Non-Covalent | H-bonding, ionic, π-π | Heterogeneous, but flexible | Simple, versatile | Site heterogeneity, template bleeding |

| Semi-Covalent | Covalent imprinting,\nnon-covalent rebinding | Well-defined, practical rebinding | Combines fidelity of covalent with practicality of non-covalent | More complex synthesis |

Experimental Protocol: Non-Covalent MIP for a Transition State Analogue (TSA)

Aim: To synthesize a MIP catalyst imprinted with a phosphonate TSA for ester hydrolysis. Materials: Phosphonate TSA (template), methacrylic acid (MAA, monomer), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, cross-linker), AIBN (initiator), acetonitrile (porogen). Procedure:

- Pre-complexation: Dissolve the TSA (0.1 mmol) and MAA (0.4 mmol) in 5 mL of dry acetonitrile in a glass vial. Sonicate for 10 minutes and let stand for 1 hour to allow complex formation.

- Polymerization: Add EGDMA (2 mmol) and AIBN (10 mg). Purge the solution with N₂ for 5 minutes. Seal the vial and polymerize in a water bath at 60°C for 24 hours.

- Template Extraction: Crush the resulting monolith. Soxhlet extract with methanol/acetic acid (9:1 v/v) for 24 hours, followed by pure methanol for 12 hours. Dry the polymer under vacuum.

- Control Synthesis: Prepare a Non-Imprinted Polymer (NIP) identically but without the TSA template.

- Catalytic Testing: Incubate MIP and NIP particles separately with a substrate ester in a suitable buffer (e.g., pH 7.4 phosphate). Monitor hydrolysis product formation over time by HPLC or UV-Vis spectroscopy. Compare rates to determine imprinting effect.

Diagram Title: Molecular Imprinting Process for Catalytic MIPs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for MOF and MIP Research

| Item / Reagent | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Zirconium(IV) Chloride (ZrCl₄) | Metal precursor for highly stable UiO-66 series MOFs. | Moisture-sensitive; handle in glovebox or under inert atmosphere. |

| 2-Aminoterephthalic Acid | Functionalized linker for MOFs; provides primary amine for catalysis or PSM. | Enables base catalysis or serves as an anchor for more complex groups. |

| N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) | Common polar aprotic solvent for solvothermal MOF synthesis. | Requires careful removal during activation; can decompose at high temps. |

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | Versatile vinyl monomer for non-covalent MIPs; H-bond donor/acceptor. | Interacts with a wide range of template functionalities. |

| Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) | Cross-linker for MIPs; controls polymer morphology and cavity rigidity. | High purity is essential to avoid irregular polymer networks. |

| Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Thermally decomposing radical initiator for (meth)acrylate polymerization. | Store cold; half-life of ~10 hours at 65°C in toluene. |

| Transition State Analogue (TSA) | Template for catalytic MIPs; defines the geometry of the active site. | Design is critical; must be stable during polymerization and removable. |

| Methanol/Acetic Acid (9:1) | Standard extraction solvent for removing template from non-covalent MIPs. | Acid disrupts ionic/H-bond interactions between template and polymer. |

Comparative Analysis and Integration for Artificial Enzyme Design

Table 4: Strategic Comparison of MOFs vs. MIPs for Active Site Preorganization

| Feature | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Order | Long-range, crystalline. | Amorphous, short-range order only at sites. |

| Active Site Design | Precise, via crystal engineering & PSM. | Statistical, defined by template-monomer interaction. |

| Porosity | Uniform, designable, often high surface area. | Heterogeneous, meso/macroporous, lower surface area. |

| Mass Transport | Can be limited by microporous windows. | Generally good due to macroporosity. |

| Chemical Stability | Varies widely (e.g., Zr-MOFs stable, Zn-MOFs labile). | Generally high chemical and mechanical stability. |

| Production Scalability | Moderate; requires pure materials and controlled conditions. | High; bulk free-radical polymerization is industrially feasible. |

| Primary Application Focus | Gas storage, separations, well-defined heterogeneous catalysis. | Biosensing, solid-phase extraction, selective binding. |

Integrated Thesis Perspective: A holistic thesis on active site preorganization would leverage the strengths of both approaches. MOFs serve as definitive model systems for studying preorganization in a rigid, characterized environment, ideal for structure-property relationship studies. MIPs offer a versatile and robust platform for creating tailorable binding pockets, particularly for targets where crystallinity is difficult to achieve. The future lies in hybrid materials—for example, using MIP layers to impart selectivity to MOF surfaces or imprinting polymers within MOF pores to combine order with versatility. This convergence will accelerate the development of next-generation artificial enzymes with programmable activity and selectivity for drug discovery, diagnostics, and green chemistry.

The rational design of artificial enzymes represents a frontier in synthetic biology and therapeutic development. A central thesis driving contemporary research is that active site preorganization—the precise spatial and electrostatic arrangement of catalytic residues and cofactors prior to substrate binding—is the critical determinant of catalytic efficiency and selectivity. This whitepaper explores the application of this principle to the design of artificial enzymes for two transformative applications: targeted prodrug activation and novel biotherapeutics.

Core Design Principles & Quantitative Benchmarks

Successful preorganization mimics the evolutionary optimization of natural enzymes, where the active site is structured to stabilize the transition state. Key quantitative targets for artificial enzymes include turnover number (kcat), Michaelis constant (KM), and catalytic proficiency (kcat/KM).

Table 1: Target Performance Benchmarks for Preorganized Artificial Enzymes

| Metric | Typical Natural Enzyme | Current State-of-the-Art Artificial Enzyme | Therapeutic Application Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s⁻¹) | 10² - 10⁶ | 10⁻² - 10² | > 10¹ |

| KM (µM) | 1 - 1000 | 100 - 10⁴ | < 1000 |

| kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | 10⁶ - 10⁹ | 10² - 10⁵ | > 10⁴ |

| Substrate Selectivity (Factor) | > 10⁴ | 10¹ - 10³ | > 10² |

Methodologies for Engineering Preorganization

Protocol 1: Computational Scaffold Design and In Silico Screening

This protocol outlines the de novo design of a preorganized active site within a stable protein scaffold.

- Scaffold Selection: Choose a thermostable, structurally rigid protein scaffold (e.g., TIM barrel, helical bundle) from the PDB database. Stability (∆Gfolding < -10 kcal/mol) is prioritized.

- Active Site Blueprinting: Using software like Rosetta, define the 3D coordinates of ideal catalytic residues (e.g., a histidine–aspartate–serine triad for hydrolases) to form a transition state analogue (TSA) complex.

- Sequence Optimization: Run the RosettaFixBB algorithm to identify amino acid sequences that stabilize the scaffold while positioning the catalytic residues within 0.5 Å RMSD of the blueprint.

- Molecular Dynamics (MD) Validation: Simulate the designed enzyme (100 ns simulation in explicit solvent) to assess the stability of the preorganized geometry. Accept designs with backbone RMSD < 2.0 Å from the original model.

- In Silico Substrate Docking: Dock the prodrug substrate and its TSA into the stable designs. Rank designs by calculated binding energy (∆Gbind < -7 kcal/mol for TSA).

Diagram 1: Computational design workflow for preorganized enzymes.

Protocol 2: Directed Evolution for Preorganization Refinement

Computational designs require experimental optimization to achieve target proficiency.

- Library Construction: Create a mutagenic library targeting second-shell residues (within 8 Å of active site) of the computational design using error-prone PCR or site-saturation mutagenesis. Library size: 10⁶ - 10⁸ variants.

- High-Throughput Screening: Employ a fluorescence-based or yeast surface display assay coupled with fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). For prodrug-activating enzymes, use a fluorogenic prodrug analogue as substrate.

- Selection Cycle: Perform 3-5 rounds of selection, increasing stringency (e.g., shorter reaction time, lower substrate concentration) each round.

- Deep Sequencing & Analysis: Sequence enriched variants (N > 1000) to identify consensus mutations. Map mutations onto structure to analyze preorganization networks.

- Characterization: Purify top clones and determine kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) via HPLC or continuous spectrophotometric assay.

Application 1: Prodrug Activation at Tumor Sites

A prime application is the design of artificial enzymes that activate inert prodrugs specifically within the tumor microenvironment (TME). The design must achieve preorganization for both catalytic efficiency and selectivity for the prodrug over endogenous substrates.

Key Signaling Pathway for Targeted Activation:

Diagram 2: Tumor-selective prodrug activation pathway.

Table 2: Exemplar Artificial Enzymes for Prodrug Therapy

| Enzyme Class | Prodrug | Activated Drug | Achieved kcat/KM (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | Tumor Selectivity (Tumor/Normal Tissue) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Designed Hydrolase | Irinotecan (Prodrug) | SN-38 | 2.1 x 10⁴ | > 50:1 (Antibody-guided) |

| Engineered Metalloenzyme | 5-FC | 5-FU | 5.5 x 10³ | > 100:1 (Gene Therapy) |

| Artificial Oxidase | Para-aminophenol | p-aminophenol (toxic) | 1.8 x 10⁴ | > 30:1 (Small Molecule Targeting) |

Application 2: Catalytic Biotherapeutics

Beyond prodrug activation, preorganized artificial enzymes can act directly as therapeutic agents, degrading disease-causing molecules.

Protocol 3: In Vitro Efficacy Assessment for a Therapeutic Protease

This protocol tests an artificial protease designed to preorganized to specifically cleave a pathogenic peptide (e.g., amyloid-β).

- Substrate Incubation: Combine 100 nM enzyme with 10 µM target peptide in physiological buffer (pH 7.4, 37°C). Run control without enzyme.

- Time-Point Sampling: Aliquot reaction mixture at t = 0, 5, 15, 30, 60, 120 minutes. Quench with 1% formic acid.

- Analytical Quantification: Analyze samples via UPLC-MS/MS. Use a standard curve of intact peptide to calculate concentration remaining.

- Data Analysis: Plot [Substrate] vs. time. Fit to a first-order decay model to determine the observed rate constant (kobs). Specificity is determined by repeating with 10 µM of a scrambled peptide sequence.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Artificial Enzyme Research

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|