Combatting Enzyme Deactivation in Organic Solvents: Molecular Insights, Stabilization Strategies, and Clinical Implications

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the challenge of enzyme deactivation in non-aqueous environments.

Combatting Enzyme Deactivation in Organic Solvents: Molecular Insights, Stabilization Strategies, and Clinical Implications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the challenge of enzyme deactivation in non-aqueous environments. It explores the fundamental molecular mechanisms of solvent-induced inactivation, details a wide array of established and emerging stabilization methodologies—from protein engineering to novel solvent systems like ionic liquids, and presents robust troubleshooting and validation frameworks. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with practical application guidelines and advanced analytical techniques, this review aims to equip scientists with the tools to design more efficient and stable biocatalytic processes for pharmaceutical synthesis and biomedical research.

The Molecular Battlefield: Understanding How Organic Solvents Deactivate Enzymes

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the primary mechanisms by which organic solvents inactivate enzymes? Organic solvents inactivate enzymes through two primary, interconnected mechanisms. First, they can cause structural denaturation by penetrating the enzyme's hydrophobic core, leading to the destabilization and eventual decomposition of secondary structures, with β-structures being more prone to destabilization than helixes [1]. Second, polar solvents can strip essential water molecules from the enzyme's surface, a process critical for maintaining its active catalytic conformation. This water stripping is nearly immediate upon exposure and its extent correlates with the solvent's polarity and its capacity to dissolve water [2].

Q2: Why does my enzyme remain active in pure hexane but lose all function in a 50/50 hexane-water mixture? This observation relates to the concentration-dependence of non-polar solvent effects. Molecular dynamics simulations have shown that low concentrations of non-polar solvents like hexane can cause more enzyme instability than higher percentages. This is because at low concentrations, hexane can diffuse into the enzyme's hydrophobic core, causing a collapse of the structure. In pure hexane, the lack of water may lead to "surface denaturation," but the enzyme's core can remain more stable, especially if it was thoroughly dehydrated beforehand. The presence of some water in the mixture facilitates the solvent's penetration and disruptive effect [1].

Q3: How can I determine if activity loss is due to structural unfolding or just essential water loss? You can distinguish between these mechanisms through a combination of biophysical characterization:

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy: Compare the far-UV and near-UV CD spectra of the enzyme before and after solvent exposure. Significant changes in far-UV CD indicate alterations in secondary structure (unfolding), while changes in near-UV CD reflect perturbations in tertiary structure [3].

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: This can detect subtle changes in secondary structure composition. A high spectral correlation coefficient (SCC >0.9) between pre- and post-incubation samples suggests minimal structural perturbation [3].

- Activity Recovery Test: Re-lyophilize the inactivated enzyme from an aqueous buffer. If activity is restored, the inactivation was likely due to reversible processes like water stripping or subtle conformational shifts rather than irreversible denaturation [3].

Q4: My enzyme is inactive in organic solvent but shows no major structural changes. What could be the cause? This common scenario points to subtle active-site perturbations rather than global unfolding. Research on subtilisin Carlsberg showed that activity can plunge without apparent secondary or tertiary structural changes, a constant number of active sites, or morphological aggregation. The mechanism likely involves rearrangement of internal water molecules critical for the enzyme's dielectric properties, minor distortions around the active site that affect substrate binding (increased Kₘ), or rearrangement of counter-ions. These changes reduce catalytic efficiency (Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ) without gross structural damage [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing and Preventing Inactivation

Table 1: Solvent-Induced Inactivation Mechanisms and Diagnostic Features

| Inactivation Mechanism | Key Diagnostic Features | Affected Enzyme Functions | Reversibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Denaturation [1] | - Decreased ellipticity in Far-UV CD spectra- Reduced FTIR spectral correlation coefficient- Loss of tertiary structure (Near-UV CD changes) | Global loss of catalytic function and structural integrity | Often irreversible |

| Essential Water Stripping [4] [2] | - Immediate activity loss in polar solvents- Activity restored upon rehydration/re-lyophilization- No major structural changes detected by CD/FTIR | Loss of catalytic activity while active sites remain titratable | Highly reversible |

| Active-Site Perturbation [3] | - Increased apparent Michaelis constant (Kₘ)- Decreased Vₘₐₓ/Kₘ- Active-site titration unchanged- No global structural changes | Reduced catalytic efficiency and substrate binding | Partially reversible |

| Cofactor Dissociation [5] | - Greater instability of holo- vs. apo-enzyme- Loss of cofactor-specific spectroscopic signals | Loss of activity in cofactor-dependent enzymes | Reversible upon cofactor re-addition |

Table 2: Enzyme Stability in Common Organic Co-Solvents

| Organic Solvent | Log P | Tolerance Threshold (v/v) | Primary Inactivation Mechanism | Stabilization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isopropanol | 0.05 | 15% [5] | Local unfolding, water stripping | Enzyme engineering of flexible loops [5] |

| Acetonitrile | -0.33 | 10% [5] | Water stripping, local dielectric changes | Control water activity, use stabilizers |

| n-Butanol | 0.88 | 6% [5] | Hydrophobic core penetration, unfolding | Immobilization on hydrophobic supports |

| Tetrahydrofuran | 0.67 | <5% [5] | Significant water stripping, structural distortion | Chemical modification with PEG |

| Ethyl Acetate | 0.23 | Forms biphasic system [5] | Partitioning of essential water | Use in biphasic systems with buffer |

| Methanol | -0.76 | Concentration-dependent [1] | Extensive water stripping, secondary structure decomposition | Lyophilization with cyclodextrin additives [3] |

| Hexane | 3.50 | Stable in pure solvent [1] | Surface denaturation in pure solvent; core collapse at low concentrations | Control water content precisely |

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Investigation

Protocol 1: Assessing Structural Denaturation via Spectroscopy

Objective: To determine whether organic solvent exposure causes secondary and tertiary structural changes in enzymes.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (lyophilized powder)

- Anhydrous organic solvent (e.g., 1,4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran)

- Hydrated salt pairs (e.g., BaBr₂ hydrates) for water activity control

- Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectrometer

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectrometer with quartz cuvettes

Method:

- Prepare enzyme samples: Divide lyophilized enzyme powder into two aliquots.

- Solvent incubation: Suspend one aliquot in anhydrous organic solvent at controlled water activity (using hydrated salt pairs). Incubate at 45°C for 4 days with gentle agitation.

- FTIR analysis:

- Record FTIR spectra of both incubated and control enzyme powders.

- Analyze the amide I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹) for secondary structure composition.

- Calculate the Spectral Correlation Coefficient (SCC) by comparing the second derivative spectra of incubated vs. control samples. An SCC >0.9 indicates minimal structural change [3].

- CD spectroscopy:

- Acquire far-UV (190-250 nm) and near-UV (250-320 nm) CD spectra of suspended enzyme particles.

- Compare ellipticity values before and after incubation. Significant reduction suggests structural unfolding.

- Apply absorption flattening correction for particulate samples if needed [3].

Interpretation: Concurrent changes in both FTIR and CD spectra indicate structural denaturation. Isolated changes in catalytic activity with preserved structure suggest water stripping or subtle active-site perturbations.

Protocol 2: Differentiating Water Stripping from Denaturation

Objective: To determine whether activity loss stems from essential water removal or irreversible structural damage.

Materials:

- Tritiated water (T₂O)

- Lyophilizer

- Organic solvents with varying polarity (e.g., methanol, hexane)

- Liquid scintillation counter

- Standard activity assay reagents

Method:

- Enzyme labeling:

- Exchange enzyme-bound H₂O with T₂O by incubating the aqueous enzyme solution with tritiated water.

- Rapidly freeze and lyophilize the labeled enzyme to retain tritiated water bound to the protein surface [2].

- Solvent exposure:

- Suspend tritiated enzymes in various organic solvents with different polarities (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, hexane).

- Incubate with shaking for predetermined intervals (5 min to several hours).

- T₂O desorption measurement:

- Separate the solvent from enzyme by centrifugation.

- Measure tritium content in the solvent using liquid scintillation counting.

- Calculate the percentage of bound T₂O desorbed into each solvent [2].

- Activity correlation:

- Run parallel activity assays on enzyme samples after solvent exposure.

- Correlate the extent of water desorption with activity loss.

Interpretation: Polar solvents like methanol typically desorb 56-62% of bound water with immediate activity loss, while non-polar solvents like hexane desorb only 0.4-2% with minimal activity impact. A strong correlation between water desorption and activity loss confirms water stripping as the primary mechanism [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Investigating Enzyme Inactivation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Application Example | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrated Salt Pairs | Control water activity (a𝓌) in organic solvents | Maintaining constant a𝓌 during stability studies | [3] |

| Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MβCD) | Enzyme stabilizer during lyophilization | Co-lyophilization with subtilisin Carlsberg to reduce inactivation | [3] |

| Tritiated Water (T₂O) | Radiolabel tracer for bound water | Quantifying water stripping from enzymes in organic solvents | [2] |

| Spin-Label Probes | EPR spectroscopy to probe active site flexibility | Monitoring conformational changes in organic solvents | [3] |

| Cross-Linked Enzyme Crystals | Structurally rigid enzyme preparation | Distinguishing between structural and dynamic inactivation mechanisms | [3] |

| Polyethylene Glycol | Chemical modifier for enzyme solubilization | Enhancing enzyme stability and activity in organic solvents | [3] |

| Magnetic MOF Supports | Advanced immobilization matrices | Enzyme stabilization with 85% sugar yield in biomass conversion | [6] |

Mechanistic Pathways of Enzyme Inactivation

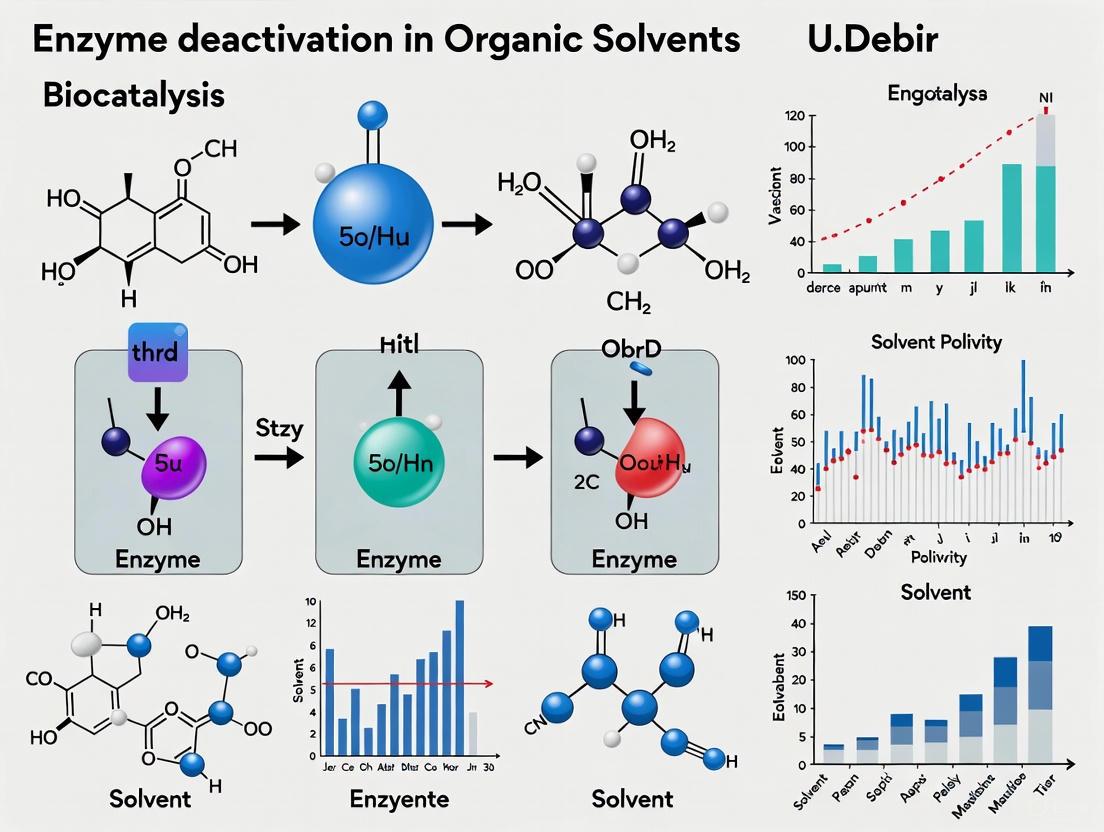

The following diagrams illustrate the primary pathways through which organic solvents inactivate enzymes, integrating structural denaturation and essential water stripping mechanisms.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Enzyme Issues in Organic Solvents

Q1: Why does my enzyme show little to no activity in an organic solvent?

Several factors can cause a severe loss of enzyme activity in organic solvents.

- Water Stripping: Polar solvents (e.g., DMSO, DMF, Acetone) strip the essential bound water from the enzyme's surface, which is crucial for maintaining its active conformation and flexibility [7] [8]. This is the most common cause of deactivation in polar media.

- Solvent Penetration: Polar solvent molecules can penetrate the enzyme's active site, disrupting the hydrogen-bonding network critical for catalysis [8] [9]. For instance, molecular dynamics simulations show DMSO molecules replacing water in the active site of glucose oxidase, preventing substrate binding [9].

- Excessive Rigidity: Non-polar solvents (e.g., hexane, toluene) can make the enzyme structure too rigid, limiting the conformational dynamics needed for substrate binding and catalysis [7] [8].

Q2: How does the choice of solvent affect my enzyme's stability and reaction efficiency?

The hydrophobicity of the solvent, measured by its log P value, is a key predictor of enzyme performance.

- High log P (> 4, Hydrophobic): Solvents like octane and toluene tend to preserve enzyme activity and stability. They do not strip essential water and cause less structural disruption [10] [7].

- Low log P (< 1, Hydrophilic): Solvents like DMSO and acetonitrile are often denaturing. They aggressively strip water and can penetrate the enzyme structure, leading to inactivation and aggregation [7] [9].

- Enhanced Stability in Non-polars: In non-polar solvents, enzymes are protected from hydrolysis and microbial contamination, and often display significantly enhanced thermostability [11] [7].

Q3: I see unexpected reaction products or reduced specificity. Could the solvent be the cause?

Yes, the solvent environment can alter enzyme specificity and lead to side reactions.

- Altered Selectivity: The unique microenvironment created by an organic solvent can change an enzyme's enantioselectivity and regioselectivity by affecting the binding affinity for different substrates [7].

- Promotion of Side Reactions: In aqueous systems, hydrolases (like lipases and proteases) catalyze hydrolysis. In anhydrous organic solvents, the equilibrium shifts, allowing the same enzymes to catalyze synthetic reactions like esterification and transesterification [7].

Q4: How can I recover enzyme activity after exposure to an inhibitory solvent?

Activity recovery depends on the deactivation mechanism.

- For Water Stripping: Re-hydration of the enzyme powder prior to use or controlling the water activity (aw) of the reaction mixture can restore flexibility and activity [7].

- For Solvent-Induced Aggregation: Using immobilization techniques or chemical modification with polyethylene glycol (PEG) can prevent intermolecular aggregation and maintain activity [11] [8].

- Post-Exposure Washing: Gently washing the enzyme with a hydrophobic solvent (e.g., n-hexane) after exposure to a polar solvent can sometimes help remove bound polar molecules and restore partial activity [12].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What is the single most important solvent property to check first? A: The log P (octanol-water partition coefficient). A log P value above 4 generally indicates a hydrophobic solvent that is likely to maintain enzyme activity, while a log P below 2 indicates a hydrophilic solvent that often denatures enzymes [10] [7].

Q: Can enzymes ever show higher activity in organic solvents than in water? A: Yes, in specific cases. Some enzymes, like certain lipases and proteases, exhibit "superactivity" in organic solvents due to highly rigid structures that optimize the active site orientation. Furthermore, a recently discovered protease from Halobiforma sp. showed enhanced activity in polar solvents like DMF and DMSO [13]. This demonstrates that enzyme-solvent interactions are complex and not universally predictable.

Q: Is enzyme inactivation in organic solvents always permanent? A: Not necessarily. Studies on lipases have shown that activity loss in organic solvents can be rapid but sometimes reaches a stable, residual level of activity. The initial rapid inactivation is often not due to irreversible unfolding but to local active-site effects that may be reversible upon re-hydration or solvent exchange [11].

Q: Besides log P, what other solvent properties should I consider? A: The functional groups and molecular structure of the solvent are also critical. For example, small polar solvents like acetone and acetonitrile can more easily penetrate the enzyme's active site than larger molecules, causing more significant inhibition [7]. The solvent's ability to form hydrogen bonds with the enzyme is another key denaturing factor.

Data Presentation: Quantitative Effects of Solvents

Table 1: Correlation Between Solvent Log P and Relative Enzyme Activity

This table summarizes the general trend of how solvent polarity affects the activity of various enzymes, such as lipases and proteases.

| Solvent | Log P Value | Polarity Class | Observed Effect on Enzyme Activity | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO, DMF | -1.3 to -0.8 | Polar Hydrophilic | Severe Deactivation | Strips essential water; penetrates and disrupts active site [7] [9] |

| Acetone | -0.23 | Polar Hydrophilic | Significant Deactivation | Strips bound water, reducing enzyme flexibility [10] |

| Ethanol | -0.18 | Polar Hydrophilic | Moderate to Severe Deactivation | Competes for water, can denature protein structure [9] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | 0.49 | Moderately Polar | Partial Deactivation | Removes some essential hydration water [10] |

| Toluene | 2.5 | Non-Polar Hydrophobic | Moderate to High Activity | Preserves bound water layer; maintains activity [10] [8] |

| Octane | 4.5 | Non-Polar Hydrophobic | High Activity | Optimal for maintaining native conformation and activity [10] |

Table 2: Experimental Results: Solvent Impact on Specific Enzymes

This table provides concrete data from published studies on different enzymes.

| Enzyme | Solvent | Key Experimental Finding | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. antarctica Lipase B (CALB) | Acetonitrile (log P: -0.33) | Protein structure change, disruption of key hydrogen bonds in active site | [12] |

| C. antarctica Lipase B (CALB) | Toluene (log P: 2.5) | Preservation of active site hydrogen bonds; increased biodiesel yield | [12] |

| Subtilisin Carlsberg | Octane (log P: 4.5) | Catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) is 10.6% of aqueous buffer, but stability is 645x higher | [7] |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | Dichloromethane (ε=8.9) | ~60-80% retention of catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) | [9] |

| Glucose Oxidase (GOx) | DMSO (ε=47.2) | Near-total loss of catalytic efficiency due to active site coordination | [9] |

| Protease (Halobiforma sp.) | DMF, DMSO | Enhanced activity observed, defying the typical log P trend | [13] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing Enzyme Activity and Stability in a Panel of Solvents

Objective: To systematically evaluate the effect of different organic solvents on the activity and storage stability of a given enzyme.

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (lyophilized powder is typical)

- Selected organic solvents covering a range of log P values (e.g., Hexane, Toluene, THF, Acetonitrile, DMSO)

- Substrate and reagents for activity assay

- Incubation vials with septa

- Shaking incubator

Method:

- Solvent Exposure: Dispense 1-mL aliquots of each anhydrous organic solvent into separate vials. Add a measured quantity (e.g., 1-10 mg) of the dry enzyme powder to each vial. Seal tightly to prevent moisture absorption.

- Incubation: Incubate the vials at a constant temperature (e.g., 30°C or 37°C) with gentle shaking for a predetermined time (e.g., 1, 6, 24 hours).

- Activity Assay:

- After incubation, separate the enzyme from the solvent by filtration or gentle centrifugation.

- Option A (Direct in-solvent assay): If the enzyme is immobilized and the assay is feasible in the solvent, add substrate solution directly to the solvent slurry and monitor product formation.

- Option B (Re-hydration assay): For a more standard measure, evaporate the solvent completely from the enzyme under vacuum. Re-suspend the enzyme in a standard aqueous assay buffer and immediately measure the initial reaction rate using your standard protocol. This measures the residual activity after solvent exposure.

- Data Analysis: Express the measured activity as a percentage of the activity of a control enzyme (not exposed to solvent or exposed only to a reference solvent like octane). Plot residual activity vs. solvent log P to visualize the correlation.

Protocol 2: Measuring the Effect of Water Activity (aw) Control

Objective: To demonstrate that adding controlled amounts of water can recover activity lost in polar organic solvents.

Materials:

- Enzyme preparation

- Anhydrous solvent (e.g., Acetonitrile)

- Salt-saturated solutions for aw control (e.g., LiCl for aw ~0.11, Mg(NO3)2 for aw ~0.52, NaCl for aw ~0.75) [7]

Method:

- Prepare separate reaction mixtures containing the enzyme and substrate in anhydrous acetonitrile.

- Place each reaction vial inside a larger sealed container (desiccator) alongside an open beaker containing one of the salt-saturated solutions. This creates an atmosphere with a defined water activity.

- Allow the system to equilibrate for several hours.

- Initiate the reaction and measure the initial velocity.

- You will typically observe a bell-shaped curve of activity versus aw, with an optimum usually below aw 0.7, confirming that a specific hydration level is required for optimal function in organic media [7].

Visualization of Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for troubleshooting enzyme activity in organic solvents, as detailed in this guide.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Enzyme-in-Solvent Research

| Item | Function & Application | Key Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Immobilized Enzyme Preparations (e.g., Novozym 435) | Heterogeneous biocatalysis in organic solvents. | Immobilization on a solid support (e.g., resin) enhances stability, prevents aggregation, and simplifies recovery/reuse [11] [8]. |

| Molecular Sieves (3Å or 4Å) | Control of water activity (aw) in reaction mixtures. | Added directly to the reaction to scavenge trace water, maintaining a low-water environment crucial for synthetic reactions (e.g., esterification) [7]. |

| Salt Hydrate Pairs (e.g., NaOAc/NaOAc·3H₂O) | Precise buffering of water activity (aw). | Provides a constant and defined aw in the reaction vessel, allowing for reproducible optimization of enzyme hydration [7]. |

| PEG-Modified Enzymes | Solubilization and stabilization in organic solvents. | Covalent attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains creates a hydrophilic shell around the enzyme, preserving essential water and improving activity in non-aqueous media [11]. |

| Solvent Selection Guide (Based on Log P) | Initial solvent screening for new reactions. | Using a panel of solvents with log P values from -2 to 5 allows for rapid identification of a suitable, non-denaturing reaction medium [10] [7]. |

FAQs: Core Mechanisms and Principles

Q1: How do organic solvents trigger enzyme inactivation? Organic solvents can cause enzyme inactivation through two primary mechanisms: interfacial inactivation and inactivation by dissolved solvent molecules.

- Interfacial Inactivation: This occurs at the boundary between the aqueous enzyme solution and the organic solvent. The enzyme molecules adsorb to this interface, leading to their unfolding and deactivation. The extent of damage is proportional to the total interfacial area exposed. Solvents that create interfaces with lower interfacial tension (often more polar solvents like decyl alcohol) typically cause less severe inactivation compared to highly non-polar solvents like alkanes [14].

- Dissolved Solvent Inactivation: Even solvent molecules dissolved in the aqueous phase can inactivate enzymes. This is a first-order process where the dissolved solvent molecules directly perturb the enzyme's structure or dynamics over time [15].

Q2: Can solvents affect enzymes without changing their structure? Yes, research indicates that solvents can significantly disrupt enzyme function by altering conformational dynamics without causing major structural changes. A study on Ribonuclease A (RNase A) showed that a single mutation (A109G), which removes a single methyl group, did not perturb the enzyme's three-dimensional structure. However, it significantly enhanced conformational dynamics on nano- to milli-second timescales, leading to major ligand repositioning and altered function [16]. Similarly, subtilisin Carlsberg lost activity in 1,4-dioxane without showing apparent secondary or tertiary structural changes [3].

Q3: What is the relationship between solvent properties and inactivation severity? For interfacial inactivation, the functional group and resulting interfacial tension are critical. For a set of solvents with similar hydrophobicity (log P ~4.0), inactivation of chymotrypsin was much less severe with amphiphilic solvents (e.g., decyl alcohol) than with non-polar alkanes (e.g., heptane) [14]. This suggests that a more polar interface is less denaturing to an enzyme adsorbing from the aqueous phase.

Q4: Does solvent exposure always lead to a permanent loss of enzyme activity? Not always. For some enzymes, the activity loss upon exposure to organic solvents is reversible. For example, subtilisin Carlsberg inactivated in organic solvent could regain its activity upon re-lyophilization from an aqueous buffer, indicating that the process did not involve irreversible denaturation or autolysis [3].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid enzyme inactivation in two-phase systems | Extensive interfacial inactivation due to high solvent-water interfacial area and/or use of a non-polar solvent [14] [15]. | Reduce interfacial area (e.g., slower stirring). Use a more polar solvent (e.g., decyl alcohol over heptane) to lower interfacial tension [14]. Add stabilizing additives like methyl-β-cyclodextrin [3]. |

| Gradual activity loss over time in organic solvent | Inactivation by dissolved solvent molecules altering the enzyme's dielectric environment or dynamics [15] [3]. | Pre-hydrate the enzyme to a critical water activity. Use solvents with minimal solubility in the aqueous phase. Chemically modify the enzyme (e.g., PEGylation) to enhance stability [3]. |

| Altered substrate specificity or binding affinity in solvent | Solvent-induced shift in the enzyme's conformational equilibrium, favoring states with different dynamic properties and ligand affinities [17] [16]. | Characterize conformational dynamics (e.g., via smFRET or NMR). Optimize solvent conditions to favor the catalytically competent conformation. |

| Low catalytic efficiency (V~max~/K~M~) after solvent exposure | Subtle, reversible structural changes around the active site or rearrangement of water molecules, affecting the dielectric environment without gross structural denaturation [3]. | Active-site titration to confirm the number of functional enzymes. Use techniques like FTIR and CD to rule out major structural changes and focus on dynamic investigations [3]. |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies

Protocol: Quantifying Interfacial Inactivation

This protocol uses a bubble column apparatus to measure inactivation specifically due to the solvent-water interface [14] [15].

- Principle: Solvent droplets are passed through an enzyme solution in a column. The amount of enzyme inactivated is proportional to the total interfacial area exposed [15].

- Procedure:

- Apparatus Setup: Use a glass bubble column. Introduce the organic solvent at the bottom to form droplets that rise through the aqueous enzyme solution.

- Control Experiment: Measure inactivation caused by dissolved solvent molecules alone by vigorously mixing the enzyme and solvent, then allowing the phases to separate completely before assaying the aqueous phase.

- Interfacial Inactivation: Pass a known volume of solvent (e.g., hexane) through the enzyme solution. The total interfacial area (A) can be calculated from the number and size of the droplets.

- Activity Assay: Sample the enzyme solution at intervals and measure residual activity.

- Data Analysis: The rate of interfacial inactivation is expressed as the amount of enzyme inactivated per unit area (e.g., μkat m⁻²). It should be proportional to the interfacial area, not just time [15].

Protocol: Probing Conformational Dynamics with smFRET

Single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET) can track domain motions in real-time [17].

- Principle: A protein is site-specifically labeled with a donor and an acceptor fluorophore. Changes in the distance between the two domains cause changes in FRET efficiency.

- Procedure:

- Enzyme Labeling: Use a cysteine-free mutant of the target enzyme (e.g., adenylate kinase). Introduce two cysteines at specific positions in the moving domains (e.g., A73C in CORE and V142C in LID domain). Label with donor (e.g., Cy3) and acceptor (e.g., Cy5) dyes [17].

- Sample Preparation: For freely diffusing molecules, use extremely dilute enzyme solutions in buffered conditions with or without solvent/denaturant.

- Data Acquisition: Use a confocal microscope or TIRF setup. Illuminate with lasers and collect fluorescence bursts as single molecules diffuse through the detection volume.

- Data Analysis: Calculate FRET efficiency (E) for each burst. Build FRET efficiency histograms to identify populations of open (low E) and closed (high E) conformations. Analyze changes in these populations and transition rates under different solvent conditions [17].

Protocol: Assessing Structural Integrity via FTIR and CD

Use these techniques to rule out major structural denaturation as the cause of activity loss [3].

- Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR):

- Purpose: Probe secondary structure changes.

- Method: Prepare enzyme as a lyophilized powder or KBr pellet. Acquire spectra in the amide I region (1600-1700 cm⁻¹). Analyze the second derivative spectra and calculate the similarity correlation coefficient (SCC) by comparing the spectrum of the incubated sample to that of the fresh, native enzyme. A high SCC (>0.9) indicates minimal secondary structure change [3].

- Circular Dichroism (CD):

- Purpose: Probe both secondary (far-UV) and tertiary (near-UV) structure.

- Method:

- Far-UV CD (190-250 nm): Use a short pathlength cell (0.1 mm) with enzyme in aqueous buffer to assess secondary structure.

- Near-UV CD (250-320 nm): Use a longer pathlength cell (10 mm) with enzyme powder or suspension. This is sensitive to the asymmetric environment of aromatic side chains, reporting on tertiary structure. Minimal changes in the near-UV CD spectrum after solvent incubation suggest an intact tertiary structure [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key reagents used in the featured studies to investigate and mitigate solvent effects.

| Research Reagent | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| Urea (at sub-denaturing concentrations) | Used as a mechanistic probe to perturb the conformational equilibrium of adenylate kinase, revealing how dynamics regulate activity and substrate inhibition [17]. |

| Methyl-β-Cyclodextrin (MβCD) | An additive co-lyophilized with subtilisin Carlsberg to improve enzyme stability and reduce activity loss in organic solvents like 1,4-dioxane [3]. |

| smFRET Dye Pair (e.g., Cy3/Cy5) | Site-specific labels for single-molecule FRET spectroscopy that enable direct observation of domain motions (e.g., opening/closing) in enzymes like adenylate kinase under various conditions [17]. |

| Decyl Alcohol | An amphiphilic organic solvent used in studies of interfacial inactivation. It causes less severe inactivation compared to non-polar solvents of similar log P due to its lower interfacial tension [14]. |

| Hydrated Salt Pairs (e.g., BaBr₂) | Used to maintain a constant water activity (a~w~) in organic solvent systems, allowing researchers to separate the effects of dehydration from the direct effects of the solvent [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my enzyme's activity drop significantly when I transfer it from an aqueous buffer to an organic solvent? The drastic drop in activity, often four to five orders of magnitude, is primarily due to the loss of essential water molecules from the enzyme's surface and active site [18] [19]. Organic solvents, especially polar ones, can strip away this crucial hydration layer, which is necessary for maintaining the enzyme's flexible, catalytically active state. This leads to reduced conformational dynamics and can disrupt the enzyme's ability to properly bind substrates and facilitate catalysis [19] [20].

Q2: What is the difference between a "structural" and an "essential" hydration shell? The structural hydration shell refers to the broader layer of water molecules surrounding the protein, which contributes to overall stability. The essential hydration shell (or "crucial water") consists of a small number of water molecules bound to specific sites on the enzyme, often within the active site, that are critical for catalytic function [19]. These essential water molecules facilitate dynamics, stabilize transition states, and maintain the correct polarity of the active site. Their loss leads to a direct and disproportionate decrease in activity [20].

Q3: I measured a high melting temperature (Tm) for my enzyme. Why does it still perform poorly in organic solvent? The melting temperature (Tm) measures global structural stability but does not correlate directly with catalytic activity in organic solvents [21]. An enzyme can remain folded (high Tm) yet be catalytically inactive because the essential hydration shell around its active site has been disrupted. A more informative parameter is cU50T, the solvent concentration required for 50% unfolding at a specific temperature T, which has been shown to better indicate the point where activity drops most sharply [21].

Q4: How does prolonged storage in organic solvents further reduce my enzyme's initial activity? Studies on subtilisin Carlsberg show that during prolonged exposure, the organic solvent can gradually penetrate and alter the active site's microenvironment. The polarity of the active site shifts to resemble that of the bulk organic solvent, suggesting that essential water molecules are being replaced [20]. This can force substrates to bind in less catalytically favorable conformations, reducing Vmax and KM over time, even if the enzyme's overall structure appears intact [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Problems and Solutions

Problem: Low Catalytic Activity in Organic Solvent

- Potential Cause 1: Loss of essential hydration shell.

- Solution: Control the system's water activity (aw). Pre-equilibrate the enzyme and solvent with salt hydrate solutions that provide a defined water activity, ensuring the enzyme retains its essential water molecules [22].

- Potential Cause 2: Reduced enzyme flexibility.

- Solution: Use salt activation. Lyophilize the enzyme in the presence of potassium salts (e.g., KCl) or crown ethers. This has been shown to enhance activity by orders of magnitude by maintaining a more flexible and hydrated protein structure during transfer to the organic medium [19].

Problem: Enzyme Inactivation During Storage or Reuse

- Potential Cause: Slow structural deterioration and active site changes.

- Solution: Implement enzyme immobilization. Covalently binding the enzyme to a solid support (e.g., mesoporous silica or functionalized polymers) or cross-linking it can rigidify the structure, prevent unfolding, and minimize undesirable interactions with the solvent, thereby improving storage and operational stability [23].

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Solvent Batches

- Potential Cause: Variations in trace water content.

- Solution: Meticulously control and document the water content of your organic solvents. Use anhydrous solvents from sealed containers and measure water content via Karl Fischer titration for reproducible reaction conditions [20].

Quantitative Data on Enzyme Stability in Solvents

The following table summarizes key stability parameters for a selection of ene-reductases (EREDs) in different organic co-solvents, demonstrating how stability rankings can diverge based on the chosen metric [21].

Table 1: Stability Parameters for Selected Ene-Reductases (EREDs) in Organic Co-solvents

| Enzyme | Native Tm in Buffer (°C) | ∆Tm in 20% (v/v) n-Propanol (°C) | cU5025°C for n-Propanol (% v/v) | Relative Activity in 15% n-Propanol (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TsOYE | >90 | ~ -25 | ~32 | >80 |

| XenA | 49.0 ± 0.0 | ~ -12 | ~22 | ~50 |

| NerA | 40.7 ± 0.3 | ~ -5 | ~18 | ~10 |

Data adapted from Nature Communications (2024) [21]. This study highlights that while TsOYE has the highest native Tm and suffers the largest absolute ∆Tm, it also has the highest cU50 and retains the most activity, whereas NerA, with the lowest native Tm, is the least stable and active according to all metrics.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Salt-Activated Lyophilization for Enhanced Activity [19]

- Preparation: Dissolve the purified enzyme in a low-concentration buffer (e.g., 5-10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0).

- Additive: Add a kosmotropic salt like potassium chloride (KCl) to a final concentration of 10-100 mM.

- Lyophilization: Flash-freeze the solution in liquid nitrogen and lyophilize for at least 48 hours.

- Storage: Store the resulting lyophilized powder in a desiccator at -20°C until use.

- Application: Suspend the pre-weighed, salt-activated powder directly into the anhydrous organic solvent for catalysis.

Protocol 2: Measuring Active Site Polarity via Fluorescence Spectroscopy [20]

- Labeling: Chemically modify a serine protease (e.g., Subtilisin Carlsberg) at its active site serine with a dansyl fluorophore to create a catalytically inactive, fluorescently labeled probe (Ser221-D).

- Solubilization: For studies in organic solvents, chemically modify the enzyme with polyethylene glycol (PEG, 5 kDa) to ensure solubility.

- Measurement: Dissolve the labeled enzyme in the organic solvent of choice. Record the fluorescence emission spectrum (excitation ~330-370 nm).

- Analysis: Monitor the emission maximum (λmax) over time. A shift in λmax toward longer wavelengths indicates a more polar environment, showing that the solvent is penetrating the active site and replacing essential water molecules.

Logical Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the logical process for troubleshooting enzyme activity in organic solvents, based on the principles of hydration shell management.

Troubleshooting Enzyme Activity

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Investigating Hydration Effects

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experimentation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Salt Hydrates (e.g., Na₂HPO₄·12H₂O) | To pre-set and control water activity (aw) in reaction mixtures [22]. | Different salts provide a range of fixed aw values for creating hydration isotherms. |

| Kosmotropic Salts (KCl, (NH₄)₂SO₄) | Added before lyophilization to "salt-activate" enzymes, helping retain essential water and boost activity [19]. | Also known as "lyoprotectants"; they stabilize the enzyme's hydration shell during dehydration. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Chemical modifier to solubilize enzymes in organic solvents for spectroscopic studies [20]. | PEGylation allows for direct analysis (e.g., fluorescence, NMR) of enzymes in solvent, rather than in suspension. |

| Hydrophobic Solvents (e.g., Hexane) | Low-polarity reaction media that strip less water from the enzyme's essential hydration shell [19] [24]. | Log P is a useful predictor; higher Log P solvents (>2) are generally less denaturing. |

| Fluorescent Probes (e.g., Dansyl Fluoride) | Covalently labels the active site to report on local polarity and hydration via emission shift [20]. | The probe must bind specifically without disrupting the global protein structure. |

For researchers in drug development and industrial biocatalysis, the deactivation of enzymes in organic solvents represents a significant bottleneck. These solvents, while often essential for dissolving hydrophobic substrates, can strip essential water molecules from enzymes, disrupt their tertiary structure, and lead to rapid loss of catalytic function [25]. This technical support center draws upon the unique adaptations of extremophiles—organisms thriving in Earth's most hostile environments—to provide actionable solutions for overcoming these challenges. The extraordinary stability of extremophilic enzymes (extremozymes) in non-aqueous conditions offers a blueprint for designing more robust biocatalytic processes, enabling advancements in pharmaceutical synthesis and green chemistry [26] [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do enzymes typically lose activity in organic solvents? Enzyme deactivation occurs through several mechanisms: (1) Conformational changes: Solvents, especially polar ones, can penetrate and disrupt the enzyme's native structure. (2) Stripping of essential water: Water molecules act as a lubricant for protein dynamics; their removal reduces flexibility and activity. (3) Competitive inhibition: Solvent molecules can directly block the active site. (4) Alteration of substrate solubility: This can limit substrate access to the enzyme [25] [1]. The denaturation process often begins with the diffusion of the solvent into the enzyme's hydrophobic core, leading to the destabilization of secondary structures, with beta-sheets being more vulnerable than alpha-helices [1].

Q2: What structural features make extremophilic enzymes so solvent-tolerant? Extremozymes have evolved unique structural adaptations that confer stability:

- Dense Hydrophobic Cores: A tightly packed interior, stabilized by strong hydrophobic forces, resists penetration by solvent molecules [1].

- Increased Surface Charge: Halophilic (salt-loving) enzymes, for instance, possess more acidic surfaces with negative charges. This promotes higher hydration, forming a protective water shield that prevents aggregation and denaturation in harsh conditions [28] [26].

- Rigid Structures: Thermostable enzymes from thermophiles often have more rigid, compact structures, achieved through a higher number of ionic networks, hydrogen bonds, and disulfide bridges, which also confer resistance to chemical denaturants and organic solvents [28].

- Unique Amino Acid Composition: Adaptations can include a specific pattern of amino acids that favor stability over flexibility under extreme conditions [26].

Q3: How can I quickly assess if an enzyme is stable in my solvent system? A combination of Ion Mobility Spectrometry-Mass Spectrometry (IMS-MS) and standard activity assays provides a powerful and rapid screening method. IMS-MS can directly monitor changes in protein folding and cofactor binding in the presence of cosolvents like acetonitrile. The results from IMS-MS, which show the population of native vs. unfolded states, strongly correlate with activity data from spectrophotometric assays (e.g., monitoring NADPH oxidation), allowing you to rationalize activity loss based on structural changes [29].

Q4: Can I engineer a mesophilic enzyme to be as stable as an extremozyme? Yes, protein engineering is a highly effective strategy. By integrating structural insights from naturally solvent-tolerant extremozymes, you can enhance the stability of conventional enzymes. Key approaches include:

- Rational Design: Introducing point mutations to strengthen hydrophobic packing, increase salt bridges on the protein surface, or reduce flexible loop regions [25].

- Directed Evolution: Creating mutant libraries and screening them for activity in the presence of organic solvents to identify variants with enhanced stability [25].

- Consensus Design: Engineering enzymes based on conserved sequences found in stable extremophilic homologs [27].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Enzyme Instability in Organic Solvents

| Problem | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Methods | Evidence-Based Solutions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rapid activity loss | Solvent stripping essential water; conformational unfolding. | IMS-MS to detect unfolding; activity assays over time [29]. | - Use a buffered solution instead of unbuffered water [29].- Optimize water activity (aw) in the reaction medium [25].- Switch to a solvent with a higher log P (>4) [25]. |

| Irreversible deactivation at high solvent concentrations | Permanent denaturation; collapse of the hydrophobic core; solvent penetration. | Long-term stability assays; Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation studies [1]. | - Source enzymes from polyextremophiles (e.g., thermophilic and halophilic organisms) [26].- Employ enzyme immobilization to restrict conformational mobility and create a protective microenvironment [30] [25]. |

| Poor performance in mixed-solvent systems | Polymer support deswelling; enzyme leaching; reduced electron transfer (in bioelectrocatalysis). | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) of immobilized enzyme; electrochemical impedance spectroscopy. | - Tune the composition of osmium-based redox polymers to minimize deswelling [30].- Use porous electrode materials to enhance surface area and enzyme loading [30]. |

| Cofactor dissociation | Solvent-induced loosening of the protein structure. | IMS-MS to check for loss of non-covalently bound cofactors (e.g., FMN, NADPH) [29]. | - Use a buffered system, which has been shown to help retain the FMN cofactor even at high solvent concentrations [29].- Consider engineering the cofactor-binding site for stronger interaction. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Assessing Enzyme Stability via IMS-MS and Activity Assay

This protocol, adapted from research on an ene reductase, provides a methodology for correlating structural integrity with catalytic function [29].

Workflow Diagram: Evaluating Enzyme-Solvent Compatibility

Materials:

- Purified enzyme (e.g., ene reductase from Gluconobacter oxydans)

- Organic cosolvent (e.g., Acetonitrile, Methanol)

- Ammonium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.2-7.2)

- Nano-ESI-Quadrupole-Ion Mobility Spectrometry-OA-TOF Mass Spectrometer

- Spectrophotometer (for measuring absorbance at 340 nm)

- Substrate (e.g., Citral) and Cofactor (e.g., NADPH)

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate the purified enzyme (10 µM) in both buffered (0.1 M ammonium acetate) and unbuffered aqueous solutions with varying percentages of the organic cosolvent (e.g., 0% to 35% v/v).

- IMS-MS Analysis: Analyze each mixture using native nano-ESI-IMS-MS. Key parameters: nitrogen as drift gas, wave velocity of 500 m/s, wave height of 25 V.

- Data Interpretation: Examine the mobilogram for the presence of different folding states (native, partially unfolded, denatured) and check the mass spectra for the presence or absence of the non-covalently bound cofactor (e.g., FMN).

- Activity Assay: In parallel, under identical solvent conditions, perform a standard spectrophotometric activity assay. For oxidoreductases, monitor the oxidation of NADPH by the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm.

- Correlation: Correlate the structural information from IMS-MS with the residual activity data from the spectrophotometric assay to determine the solvent tolerance threshold of your enzyme.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Stability via Immobilization and Engineering

This protocol synthesizes strategies validated in recent high-impact studies [30] [25].

Materials:

- Engineered solvent-tolerant enzyme (e.g., Bilirubin Oxidase from Bacillus pumilus)

- Fine-tuned osmium-based redox polymer

- Cross-linker (e.g., Poly(ethylene glycol) 400 diglycidyl ether, PEGDGE)

- Porous gold electrode or other solid support (e.g., functionalized carbon nanotubes, magnetic nanoparticles)

Procedure:

- Enzyme Selection/Engineering: Select an enzyme known for intrinsic stability (e.g., from thermophiles). For enhanced performance, use a variant engineered for solvent tolerance via rational design or directed evolution [25].

- Immobilization:

- Mix the enzyme with a specifically tuned redox polymer. The osmium complex concentration should be optimized to prevent deswelling of the polymer in organic solvents [30].

- Add a cross-linker like PEGDGE to form a stable hydrogel matrix on the electrode/support surface.

- Characterization: Test the operational stability (half-life) of the immobilized enzyme system in your target organic solvent (e.g., 12.5 M methanol). The combination of a robust enzyme, a fine-tuned polymer, and a porous support has been shown to achieve unprecedented half-lives exceeding 8 days in harsh solvents [30].

Table 2: Quantitative Stability of Engineered Biocatalytic Systems in Organic Solvents

| Enzyme | Source Organism | Solvent Condition | Key Stabilization Strategy | Achieved Stability | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirubin Oxidase (BOD) | Bacillus pumilus (engineered) | 12.5 M Methanol | Engineered enzyme + tuned osmium redox polymer + porous gold electrode | Half-life > 8 days | [30] |

| Bilirubin Oxidase (BOD) | Bacillus pumilus | 7.5 M Methanol | Not specified (baseline) | Irreversible activity loss | [30] |

| Ene Reductase | Gluconobacter oxydans | 25% v/v Acetonitrile (Buffered) | Use of 0.1 M Ammonium Acetate Buffer (pH 6.2) | High residual activity | [29] |

| Ene Reductase | Gluconobacter oxydans | 25% v/v Acetonitrile (Unbuffered) | None | Significant activity loss | [29] |

| Lipase | N/A | Pure Hexane | Natural structural adaptation (multiple helixes) | Higher stability than in water | [1] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Solvent-Stable Biocatalysis Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Rationale | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Osmium-based Redox Polymers | Mediate electron transfer in bioelectrocatalysis; can be "tuned" to minimize deswelling in solvents. | Creating stable bioelectrodes for fuel cells or biosynthesis in mixed-solvent systems [30]. |

| Porous Gold Electrodes | Provide high surface area for enzyme immobilization, enhancing loading and stability. | Used as a support for immobilizing Bilirubin Oxidase, contributing to record operational life [30]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) Diglycidyl Ether | A cross-linker for creating robust hydrogel matrices that entrap and stabilize enzymes. | Cross-linking enzymes with redox polymers on electrode surfaces [30]. |

| Ammonium Acetate Buffer | A volatile buffer compatible with MS analysis; crucial for maintaining enzyme structure and cofactor binding in cosolvents. | Used in IMS-MS studies to demonstrate enhanced enzyme stability in acetonitrile/water mixtures [29]. |

| Engineered Bilirubin Oxidase (BOD-Bp) | A model solvent-tolerant, thermostable copper enzyme for oxidizing various substrates. | Serves as a benchmark system for developing O2-reducing biocathodes in organic solvents [30]. |

Practical Strategies for Enzyme Stabilization in Non-Aqueous Systems

In the pursuit of sustainable industrial biocatalysis, enzymes often face a significant challenge: deactivation and instability in organic solvents. These solvents, while beneficial for shifting reaction equilibria toward synthesis and dissolving hydrophobic substrates, can strip essential water from enzymes, cause structural rigidification, and lead to a catastrophic loss of activity. Enzyme immobilization provides a powerful strategy to create robust biocatalysts capable of withstanding these harsh conditions. This technical support center focuses on three prominent techniques—Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs), Sol-Gel Encapsulation, and Solid Supports—providing researchers and development professionals with practical troubleshooting guides and detailed protocols to overcome deactivation in organic media, a core challenge in modern biocatalysis for drug development and fine chemical synthesis.

The selection of an appropriate immobilization method is a critical first step in designing a stable biocatalyst. The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and challenges of the three primary techniques discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key Immobilization Techniques

| Technique | Key Principle | Best For | Key Advantages | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLEAs (Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates) [31] [32] | Carrier-free precipitation of enzymes followed by cross-linking with a bifunctional agent like glutaraldehyde. | Enzymes with sufficient surface lysine residues; multi-enzyme cascade reactions (combi-CLEAs); processes where carrier cost is prohibitive. | High enzyme loading, no expensive support, potential for 10x increased stability [31], easy combi-CLEA formation for one-pot syntheses [31]. | Can have poor mechanical stability, potential for mass transfer limitations, activity loss if cross-linking is too harsh [32]. |

| Sol-Gel Encapsulation [33] [34] | Entrapment of enzymes within a porous, inorganic silica matrix formed via hydrolysis and condensation of silane precursors. | Creating a tunable protective microenvironment; enzymes in supercritical CO₂ or non-aqueous media; high operational stability requirements. | Tunable hydrophobicity/hydrophilicity, protects from denaturation and shear forces, high stability and reusability (e.g., 99% activity after 10 cycles) [34]. | Diffusion limitations for large substrates, potential for enzyme leaching if pore size is too large, shrinkage of gel during drying [33]. |

| Solid Supports (Adsorption) [35] [36] | Physical attachment of enzymes to a solid carrier via hydrophobic interactions, salt linkages, or van der Waals forces. | A quick, simple, and reversible immobilization; enzymes that are sensitive to covalent modification. | Simple procedure, minimal conformational changes, wide variety of available supports (e.g., Accurel, mesoporous silica) [35]. | Enzyme leakage from support, especially in aqueous media or with polarity changes; low stability at low enzyme loadings [36]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

CLEA-Specific Issues

Problem: My CLEAs are disintegrating or show poor mechanical stability during stirring.

- Cause & Solution: This is a common drawback of carrier-free CLEAs. The solution is to incorporate a physical support to improve mechanical properties.

- Magnetic CLEAs: Add amino-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) during the precipitation step. The enzymes co-precipitate and cross-link around the nanoparticles, creating a robust, magnetically separable biocatalyst [32]. This also dramatically eases recovery and eliminates the need for centrifugation or filtration.

- Protein Feeders: If your enzyme solution has low protein concentration, add a protein feeder like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) before cross-linking. BSA provides additional protein mass and reactive groups for the cross-linker, forming a more stable and handleable aggregate [31] [32].

Problem: I am observing a significant loss of enzymatic activity after CLEA formation.

- Cause 1: Over-cross-linking. Excessive glutaraldehyde can block the active site or cause excessive conformational rigidification.

- Cause 2: Improprecipitant. Different enzymes have different surface properties and will precipitate best with specific agents.

- Solution: Systematically screen different precipitants such as ethanol, acetone, polyethylene glycol (PEG), or ammonium sulfate to identify the one that gives the highest immobilization yield and activity recovery [31].

Sol-Gel Encapsulation Issues

Problem: The activity of my sol-gel encapsulated enzyme is very low, suggesting mass transfer limitations.

- Cause: The sol-gel matrix may be too dense, preventing efficient diffusion of substrate and product.

- Solution: Use organically modified silanes (ORMOSILs) like n-butyltrimethoxysilane (BTMS) or glycidoxypropyl-trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) as co-precursors with traditional tetramethoxysilane (TMOS). These modify the matrix's hydrophobicity and pore structure, reducing diffusion constraints. Studies show a TMOS/BTMS combination in a 1:5 ratio can yield the highest specific activity for some enzymes [33] [34].

- Additives: Incorporate additives like polyethylene glycol (PEG), crown ethers, or porous solid supports (e.g., Celite) during the gelation process. These can react with residual silanol groups and create a more open pore structure, remarkably enhancing enzyme activity and operational stability [33].

Problem: My enzyme is leaching from the sol-gel matrix during reaction or washing.

- Cause: The pore sizes of the gel network are too large, allowing the enzyme to escape.

- Solution: Optimize the hydrolysis and condensation conditions (e.g., water-to-silane ratio, catalyst type and concentration, aging time). A slower, more controlled gelation process often leads to a more robust and defined pore structure. Using precursors with epoxy functional groups (e.g., GPTMS) can also provide potential for weak covalent interactions with the enzyme, further reducing leaching [34].

General Performance Issues

Problem: The immobilized enzyme loses activity rapidly in organic solvents.

- Cause: The enzyme's essential water layer is stripped away, or the support/environment is not compatible.

- Solution for Solid Supports: Use highly hydrophobic supports like polypropylene (Accurel EP-100) or octyl-agarose. These supports help to maintain the essential water layer around the enzyme molecule, crucial for its activity in non-aqueous media [35].

- Solution for All Techniques: Add stabilizers like proteins (BSA, gelatin) or PEG during the immobilization process. These additives can protect the enzyme during the immobilization process and in the organic solvent, significantly improving activity retention [36] [37].

Problem: I need to run a multi-step synthesis, but using separate enzymes is inefficient.

- Solution: Develop a Combi-CLEA or Co-immobilized System. Co-immobilize all required enzymes into a single CLEA (combi-CLEA) or onto a single solid support. This creates a multi-functional biocatalyst that can perform sequential biotransformations in one pot, reducing process steps, cycle times, and waste. This has been successfully demonstrated for cellulase/hemicellulase mixtures and protease/carbohydrase cocktails [31] [32].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Preparation of Magnetic Combi-CLEAs

This protocol is adapted from studies on magnetic combi-CLEAs of cellulase and hemicellulase, ideal for creating robust, recyclable biocatalysts for hydrolytic or synthetic cascades [32].

Table 2: Key Reagents for Magnetic Combi-CLEA Preparation

| Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Iron (II, III) Oxide Nanopowder | Core magnetic material for easy separation with an external magnet. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent to functionalize magnetic nanoparticles with amine groups, providing a surface for enzyme binding. |

| Enzyme Cocktail (e.g., Pectinex Ultra Clear) | The enzyme or mixture of enzymes to be immobilized. Contains the protein for the biocatalytic process. |

| Glutaraldehyde (25%) | Bifunctional cross-linking agent. Forms covalent bonds between amine groups on the enzyme and the functionalized nanoparticles, creating the stable aggregate. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein feeder. Used if the enzyme protein concentration is low to facilitate aggregation and improve CLEA stability. |

| Ethanol | Precipitating agent. Causes the enzymes to aggregate out of solution onto the magnetic nanoparticles. |

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Method:

- Functionalization of MNPs: Suspend 150 mg of Iron oxide nanopowder in 30 mL of toluene. Add 0.306 mL of APTES and reflux the mixture for 24 hours under inert atmosphere. Recover the amine-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs) with a magnet, and wash thoroughly with toluene and ethanol to remove unbound APTES [32].

- Enzyme Precipitation: Re-disperse the functionalized MNPs in a suitable aqueous buffer containing your enzyme(s). While stirring, slowly add cold ethanol as a precipitant to a final concentration of ~70-80% (v/v). Continue stirring for 1-2 hours to allow the enzymes to co-precipitate and adsorb onto the MNP surface. If the protein concentration is low, add BSA (e.g., 1-5 mg per 100 mg of enzyme) at this stage [32].

- Cross-Linking: Add glutaraldehyde dropwise to the suspension to a final concentration of 50-100 mM. Continue cross-linking for 2-4 hours with mild stirring at 4-25°C.

- Recovery and Washing: Recover the magnetic combi-CLEAs using a strong neodymium magnet. Decant the supernatant and wash the resulting pellets thoroughly with buffer and then with a water-miscible organic solvent (e.g., isopropanol) to remove unreacted cross-linker and non-covalently bound protein.

- Storage: Store the final magnetic CLEAs in a suitable buffer at 4°C or in a lyophilized state.

Protocol: Optimized Sol-Gel Encapsulation of Lipase

This protocol is based on research for the immobilization of Candida antarctica Lipase B (CalB) using epoxy-functionalized silanes, resulting in biocatalysts with exceptional operational stability for ester synthesis in non-aqueous media [34].

Table 3: Key Reagents for Optimized Sol-Gel Encapsulation

| Reagent | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Tetramethoxysilane (TMOS) | Primary silane precursor; forms the rigid, inorganic silica backbone of the matrix. |

| Glycidoxypropyl-trimethoxysilane (GPTMS) | Organically modified silane (ORMOSIL) with an epoxy functional group. Tunes hydrophobicity, reduces shrinkage, and can provide mild covalent interaction with the enzyme. |

| Enzyme (e.g., CalB Lipase) | The biocatalyst to be encapsulated. |

| Sodium Fluoride (NaF) | Basic catalyst used to initiate the hydrolysis and condensation reactions of the silanes. |

Workflow Diagram:

Step-by-Step Method:

- Pre-hydrolysis of Silanes: Mix the silane precursors TMOS and GPTMS in a molar ratio of 1:1 to 1:5. Add a minimal amount of water and 1M NaF solution as a catalyst. Sonicate or stir the mixture vigorously until it becomes clear and monophasic (typically 5-10 minutes). This step pre-hydrolyzes the alkoxy groups [34].

- Addition of Enzyme: Cool the hydrolyzed silane mixture on ice. Slowly add a cold aqueous solution of your enzyme (e.g., 25 g of lipase per mole of total silane) to the silane mixture under gentle stirring. Avoid creating excessive foam [34].

- Gelation and Aging: Pour the final mixture into a suitable mold (e.g., a multi-well plate or a shallow dish). The gel will form within minutes to hours. Once set, cover the gel and allow it to age at 4°C for 24-48 hours. This aging process strengthens the silica network.

- Drying and Comminution: After aging, carefully break the gel into small particles. Dry the particles under ambient conditions or via lyophilization to form the final xerogel biocatalyst.

- Conditioning: Before the first use, wash the sol-gel particles with a buffer and then with the reaction medium (e.g., a dry organic solvent) to equilibrate the catalyst and remove any weakly bound enzyme.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent / Material | Core Function in Immobilization |

|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde | The most common bifunctional cross-linker for CLEAs; forms Schiff bases with lysine residues on enzyme surfaces, creating covalent linkages [31] [35]. |

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A protein feeder; used as an inert protein to augment low enzyme concentrations, facilitating better precipitation and cross-linking in CLEA formation [31] [32]. |

| Organically Modified Silanes (ORMOSILs) | Silane precursors (e.g., GPTMS, BTMS) used in sol-gel to tailor matrix properties like porosity, hydrophobicity, and functionality, optimizing the enzyme microenvironment [33] [34]. |

| Amino-Functionalized Magnetic Nanoparticles | A solid support that provides a high-surface-area, magnetically separable base for immobilizing enzymes via adsorption or cross-linking, simplifying biocatalyst recovery [32]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | A versatile additive; acts as a precipitant for CLEAs, a stabilizer during immobilization to protect activity, and a pore-forming agent in sol-gel matrices [31] [36] [37]. |

| Hydrophobic Carriers (Accurel, Octyl-Agarose) | Macro/mesoporous polymer supports for adsorption; their hydrophobic surface helps to stabilize the enzyme's active conformation, particularly for lipases and in non-aqueous media [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What are the primary strategies for improving enzyme stability in organic solvents, and how do I choose?

Directed evolution and rational design are the two primary strategies. Your choice depends on the structural knowledge of your enzyme and available resources.

- Directed Evolution is a powerful, unbiased approach that mimics natural evolution. It involves creating a diverse library of mutant genes, expressing them, and screening for improved solvent resistance. This method is ideal when the structural basis for stability is unknown [38] [39].

- Rational Design requires a known protein structure and understanding of stability mechanisms. It uses computational tools (e.g., FoldX) to predict stabilizing point mutations [40] [41].

- Semi-Rational Approaches combine both. For example, after a random mutagenesis round identifies "hotspot" residues, you can perform site-saturation mutagenesis to exhaustively explore all possible amino acids at those positions [42] [43].

Troubleshooting: If your rational design attempts consistently yield destabilizing mutations, switch to a directed evolution approach. It does not require a priori structural knowledge and can identify non-intuitive, beneficial mutations [39].

FAQ 2: My enzyme's activity drops significantly in organic solvents, even though stability seems high. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue where the enzyme's rigid structure in organic solvents limits its catalytic flexibility.

- Problem: The mutations you've introduced may be over-stabilizing the enzyme in a conformation that is not catalytically optimal. While stability is increased, the dynamic motions required for substrate binding and turnover are hindered [38].

- Solution: Screen for both stability and activity simultaneously. Do not select variants based on stability alone (e.g., after heat or solvent incubation). Always perform a functional activity assay under your desired reaction conditions. This ensures you isolate mutants that are both stable and functional [43].

FAQ 3: I am not finding any improved variants after screening my mutant library. What are the potential causes?

This can result from issues with your library diversity or screening method.

- Low Library Quality: The mutagenesis method may not have generated enough diversity. Error-prone PCR, for instance, has an amino acid bias and may not access all 19 possible substitutions at a given residue [39].

- Insufficient Screening Throughput: You may be screening too few clones to find the rare beneficial mutants. If your library has 10^6 variants, but you only screen 1,000, you likely missed the best hits.

- Ineffective Selection Pressure: The conditions used for screening (e.g., solvent concentration, temperature, time) may be too harsh, inactivating all variants, or too mild, failing to distinguish improved ones.

Troubleshooting:

- Increase Diversity: Use a combination of mutagenesis methods. Follow an error-prone PCR round with a recombination method like DNA shuffling to combine beneficial mutations [39].

- Optimize Screening: Use a tiered screening approach. First, use a high-throughput plate-based assay (e.g., clarity halo on milk-agar plates [38]) to quickly narrow down thousands of clones. Then, take the best hits into a microtiter plate for quantitative activity assays under more relevant solvent conditions [39].

- Titrate Selection Pressure: Perform a pilot screen with a gradient of solvent concentrations to find the "sweet spot" that kills the wild-type but allows the best mutants to survive.

FAQ 4: Computational tools predicted a highly stabilizing mutation, but my experimental results show the protein is less stable and aggregates. Why?

A primary reason is that computational tools often prioritize gains in thermodynamic stability, sometimes at the cost of solubility.

- Problem: Stabilizing mutations, particularly those that increase surface hydrophobicity, can promote protein aggregation. Tools like FoldX and Rosetta may correctly predict a mutation that strengthens the protein's core but fail to account for the new residue's propensity to cause intermolecular clumping [40].

- Solution:

- Analyze Mutation Location: If the mutation is on the protein surface, it is riskier for solubility. Consider reverting to a more hydrophilic amino acid.

- Use a Meta-Predictor: Combine the results of multiple computational tools (a meta-predictor) to get a more reliable forecast [40].

- Check for APR: Run your protein sequence through aggregation-prediction algorithms (e.g., TANGO) to see if the mutation creates or enhances an aggregation-prone region [44].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Directed Evolution via Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) and Plate-Based Screening

This is a foundational method for generating and screening diverse mutant libraries [38] [39].

1. Library Generation via Error-Prone PCR

- Objective: To introduce random mutations throughout the gene of interest.

- Reagents: Target plasmid DNA, Taq DNA Polymerase (non-proofreading), unbalanced dNTPs (e.g., higher dGTP, dATP), MgCl₂, MnCl₂.

- Procedure: a. Set up a standard PCR reaction but with modified conditions to reduce fidelity: * MgCl₂: 7 mM * MnCl₂: 0.5 mM (This is a key mutagenic agent) * dNTPs: Use a 10-fold excess of two dNTPs (e.g., dGTP and dATP) over the other two. b. Run PCR for 25-30 cycles. c. Purify the mutated PCR product and clone it into an expression vector. d. Transform into a suitable expression host (e.g., E. coli) to create your mutant library. Aim for a library size of at least 10^4 - 10^5 clones [39].

2. Primary Screening for Solvent Resistance

- Objective: To rapidly identify clones with improved solvent stability from thousands of colonies.

- Reagents: Skim milk agar plates, organic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile, acetone).

- Procedure: a. Plate the transformed library onto skim milk agar plates and incubate until colonies appear. b. Replicate the plates. One set (control) is incubated without solvent. The other set is overlaid with or exposed to vapors of a sub-lethal concentration of organic solvent (e.g., 25% v/v acetonitrile). c. Incubate. Colonies producing solvent-resistant proteases will form larger clear halos (due to caseinolysis) on the solvent-treated plates compared to the control [38]. d. Pick the clones with the largest halo-to-colony size ratio for further analysis.

3. Secondary Screening in Microtiter Plates

- Objective: To quantitatively measure the stability and activity of selected hits.

- Reagents: 96-well deep-well plates, culture media, lysis buffer, reaction buffer, colorimetric/fluorometric substrate, organic solvent.

- Procedure: a. Inoculate selected clones into deep-well plates containing culture media and express the enzymes. b. Lyse cells and collect crude enzyme extracts. c. Aliquot each extract into two parts. Incubate one part with solvent (e.g., 25-50% v/v), and the other with buffer alone. d. After a set time, assay the residual activity of both aliquots using a specific substrate. e. Calculate the residual activity (%) for each variant. Mutants with significantly higher residual activity than the wild-type are your lead hits [38].

Protocol 2: Site-Saturation Mutagenesis of Hotspot Residues

This semi-rational protocol is used for in-depth optimization after initial beneficial residues have been identified [42] [43].

1. Design and Library Construction

- Objective: To create a library where a specific amino acid position is randomized to all 19 other possibilities.

- Reagents: Plasmid DNA, high-fidelity DNA polymerase, primers containing an NNK degenerate codon (N = A/T/G/C; K = G/T).

- Procedure: a. Design forward and reverse primers that anneal to your target site. The codon you wish to mutate should be replaced with an "NNK" sequence, which encodes all 20 amino acids. b. Perform the mutagenesis PCR (e.g., using a method like QuikChange). c. Digest the PCR product with DpnI to remove the methylated parental template. d. Transform the mutated plasmid into E. coli to create the library.

2. Screening and Analysis

- Follow the same secondary screening procedure outlined in Protocol 1 (Microtiter Plate Screening) to evaluate the activity and stability of all 20 variants at the chosen position. This allows you to find the optimal amino acid for that specific site in your protein.

Key Experimental Data

Table 1: Solvent-Resistant Metalloprotease PT121 Mutants from Directed Evolution

This table summarizes quantitative data from a directed evolution study on a metalloprotease, showing how specific mutations enhanced solvent resistance [38].

| Mutant Name | Mutation(s) | Organic Solvent | Half-Life (Improvement vs. Wild-Type) | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H224F | Histidine to Phenylalanine at residue 224 | Acetonitrile / Acetone | Increased by 1.2-3.5 fold | Higher affinity than wild-type | Single point mutation enhancing stability and affinity. |

| T46Y/H224F | Tyrosine at 46, Phenylalanine at 224 | Acetonitrile / Acetone | Significantly increased | Excellent caseinolytic activity | Combined mutant showed synergistic improvement in stability and activity. Superior in peptide synthesis. |

| T46Y/H224Y | Tyrosine at 46, Tyrosine at 224 | Acetonitrile / Acetone | Significantly increased | Excellent caseinolytic activity | Combined mutant showed synergistic improvement in stability and activity. Superior in peptide synthesis. |

| F56V | Valine at 56 | Acetonitrile / Acetone | Lower than wild-type | Not reported | Disruption of a disulphide bond led to decreased stability, highlighting the importance of structural bridges. |

Table 2: Comparison of Computational Tools for Predicting Protein Stability

This table compares commonly used tools, highlighting that a combination (meta-predictor) often yields the best results [40].

| Tool Name | Underlying Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages / Caveats |

|---|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Empirical Force Field | Fast; user-friendly; widely used for rational design. | Can favor stabilizing mutations that increase surface hydrophobicity, potentially reducing solubility [40] [41]. |

| Rosetta (ddG) | Physical & Empirical Force Field | High accuracy for buried residues; sophisticated. | Computationally intensive; performance can vary. |

| PoPMuSiC | Statistical Potentials | Good for predicting changes in buried residues. | Less reliable for surface-exposed mutations. |

| Meta-Predictor | Combination of multiple tools | Highest accuracy and reliability; mitigates individual tool weaknesses [40]. | Requires access to multiple tools or a pre-built platform. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Essential materials and their functions for setting up directed evolution experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | A non-proofreading polymerase essential for error-prone PCR to introduce random mutations [39]. |

| Manganese Chloride (MnCl₂) | Key component in epPCR to reduce polymerase fidelity and increase mutation rate [39]. |

| NNK Degenerate Primers | Primers for site-saturation mutagenesis; the NNK codon allows for the incorporation of all 20 amino acids at a targeted residue [42]. |

| Skim Milk Agar Plates | Used for high-throughput primary screening of protease libraries. Active clones produce clear halos around colonies [38]. |

| Colorimetric/Fluorometric Substrates | Used in microtiter plate assays to quantitatively measure enzyme activity of different variants after exposure to solvents [39]. |

| Partially Hydrophobic Silica Nanospheres | Solid emulsifiers for creating stable Pickering emulsions, useful for advanced immobilization and compartmentalized screening or catalysis [45]. |

Workflow and Strategy Diagrams

Directed Evolution Workflow

Computational Screening Logic

The following table summarizes the two primary chemical modification strategies for stabilizing enzymes in organic solvents, detailing their core principles, advantages, and key challenges.

| Feature | PEGylation | Surface Lipid Coating |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Covalent attachment of polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains to enzyme surface [46] [47] | Physical adsorption or integration of lipids onto/into the enzyme's surface [46] [48] |

| Primary Effect on Enzyme | Creates a hydrophilic "stealth" layer and increases molecular size [46] [49] | Creates a hydrophobic protective shell or integrates into a lipid nanocarrier [46] |