Computational Protein Stability Design: Preventing Misfolding and Aggregation for Therapeutics

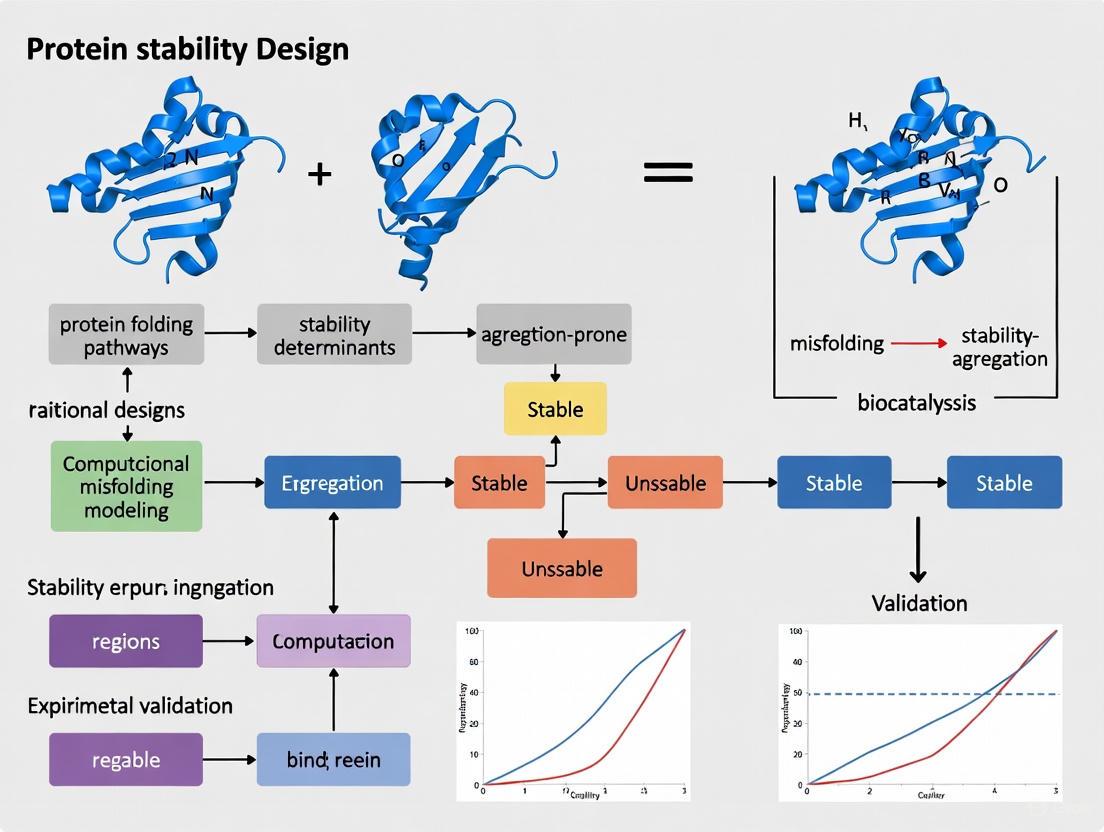

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for designing protein stability to prevent misfolding and aggregation, a key pathological mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases and loss-of-function disorders.

Computational Protein Stability Design: Preventing Misfolding and Aggregation for Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of modern strategies for designing protein stability to prevent misfolding and aggregation, a key pathological mechanism in neurodegenerative diseases and loss-of-function disorders. It explores the foundational principles of protein folding and proteostasis, details cutting-edge computational methodologies from AI-based predictors to physics-based simulations, and addresses critical optimization challenges like the stability-solubility trade-off. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, the content synthesizes validation frameworks and comparative analyses of tools to guide the rational design of stable, functional biologics and therapeutics, highlighting the successful translation of these principles into clinical agents.

The Protein Folding Problem: Linking Misfolding to Disease and Cellular Defenses

FAQs: Core Principles and Experimental Challenges

Q1: What is the fundamental thermodynamic principle linking amino acid sequence to protein structure?

The principle, established by Christian Anfinsen's experiments, states that a protein's native three-dimensional structure is the one in which the Gibbs free energy is minimized for a given amino acid sequence and physiological environment [1]. This native conformation is both thermodynamically stable and kinetically accessible. The sequence encodes the folding pathway by defining an energy landscape that resembles a funnel, guiding the polypeptide chain through a multitude of possible conformations toward the lowest-energy state [1]. The same molecular forces that drive proper folding (hydrophobic effect, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics, and van der Waals interactions) can also promote aggregation when partially unfolded states are exposed [2].

Q2: Why is understanding this principle critical for preventing protein aggregation in biopharmaceuticals?

For therapeutic proteins, even minor populations of misfolded or partially unfolded molecules can form stable, irreversible aggregates [2]. These aggregates pose a significant risk as they can elicit deleterious immune responses in patients, potentially leading to drug tolerance or neutralization of the patient's own endogenous proteins [2] [3]. Controlling aggregation is therefore essential for both the efficacy and safety of protein-based drugs. A mechanistic understanding of sequence-dependent aggregation allows for the rational design of more stable therapeutics with reduced immunogenicity [2].

Q3: What are "aggregation hot spots" and how can they be identified?

Aggregation hot spots are short, stretches of amino acids within a protein sequence that are highly prone to forming strong, stable inter-protein contacts [2]. These sequences are typically hydrophobic, lack charges, and have a high propensity to form beta-sheet structures when paired with adjacent strands [2]. They are often buried within the core of the correctly folded native state but become exposed due to local or partial unfolding events. Computational tools can predict these hot spots by analyzing the intrinsic aggregation propensity of the sequence, which aids in the early design stages of therapeutic proteins [2].

Q4: How do experimental conditions impact the thermodynamic stability of a protein?

A protein's folded state is only marginally stable, and its thermodynamic stability is highly sensitive to its environment [2] [3]. Key factors include:

- pH: Changes can alter the charge state of amino acid side chains, disrupting electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding networks.

- Temperature: Increased thermal energy can promote partial unfolding and increase molecular collisions.

- Ionic Strength: Can shield or disrupt electrostatic interactions critical for folding and solubility.

- Interfaces: Exposure to liquid-air or liquid-solid interfaces can induce denaturation.

- Co-solutes: Excipients can either stabilize the native state or destabilize it.

The table below summarizes the mechanisms of instability caused by key environmental factors.

Table 1: Environmental Challenges to Protein Stability and Underlying Mechanisms

| Environmental Factor | Impact on Protein Stability | Molecular Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| pH Shifts | Charge destabilization, Altered solubility | Modification of ionization states of side chains, disrupting salt bridges and electrostatic interactions [2]. |

| Elevated Temperature | Partial unfolding, Increased aggregation kinetics | Increased kinetic energy overcomes stabilizing weak non-covalent forces, exposing hydrophobic regions [2]. |

| Shear Stress (at interfaces) | Surface-induced denaturation | Unfolding at liquid-air or liquid-solid interfaces, leading to aggregation nucleation [2]. |

| High Protein Concentration | Accelerated aggregation | Increased frequency of molecular collisions, promoting association of partially unfolded species [2]. |

Q5: What are the primary experimental techniques for determining protein structure and stability?

The choice of technique depends on the required resolution, protein size, and the need to study dynamics versus static structure.

Table 2: Key Experimental Techniques for Protein Structure and Stability Analysis

| Technique | Key Application | Throughput | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | High-resolution atomic structure determination | Low | Requires high-quality crystals; possible crystallographic packing artifacts [4]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Solution-state structure and dynamics | Medium | Limited by protein size (~25-50 kDa); requires high concentration [4]. |

| Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM) | Large structures and complexes (e.g., viruses, membranes) | Medium-High | Challenging for small proteins (<50 kDa) [4]. |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) | Secondary structure content and stability (thermal/chemical denaturation) | High | Low-resolution; provides structural overview, not atomic details [1]. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) | Quantitative measurement of thermal stability (Tm and ΔH) | Medium | Requires high protein concentration; can be low-throughput [3]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating Protein Aggregation

Problem: Your therapeutic protein candidate is forming soluble oligomers or visible aggregates during purification or storage.

Investigation & Solution Workflow: The following diagram outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and mitigate aggregation.

Steps:

Analyze Sequence/Structure:

- Action: Use computational tools to identify potential aggregation hot spots and model local stability [2] [5].

- Evidence: Correlate regions of low conformational stability with known proteolytic cleavage sites or hydrogen-deuterium exchange data.

- Solution (Strategy 1 - Engineer Sequence): Implement rational design or directed evolution to introduce stabilizing mutations (e.g., surface entropy reduction, core packing), or disrupt beta-sheet propensity in hot spots without compromising activity [2] [3].

Characterize Solution Conditions:

- Action: Perform a stability screen across a matrix of pH, buffer species, ionic strength, and temperatures. Use techniques like CD, DSC, and size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) to monitor structure and oligomeric state [3].

- Evidence: Identify conditions that maximize the melting temperature (Tm) and minimize the formation of higher molecular weight species.

- Solution (Strategy 2 - Optimize Formulation): Develop the final formulation with optimal pH and include stabilizing excipients such as sugars (e.g., sucrose, trehalose) for preferential exclusion, surfactants (e.g., polysorbate 80) to mitigate interface stress, and antioxidants [3].

Assess Process Stressors:

- Action: Audit the entire production and storage pipeline for stressors like excessive shear (from mixing or pumping), exposure to air-liquid interfaces, freeze-thaw cycles, or metal leachates [2].

- Evidence: Correlate the onset of aggregation with specific unit operations (e.g., after tangential flow filtration).

- Solution (Strategy 3 - Modify Process): Implement process changes such as using lower-shear pumps, adding surfactants early in purification, minimizing bubble formation, and controlling hold times and temperatures [2].

Guide 2: Validating Computational Structure Predictions

Problem: You have used an AI tool like AlphaFold-2 to predict your protein's structure, but need to validate the model experimentally before making drug discovery decisions.

Investigation & Solution Workflow: The following diagram illustrates a multi-technique validation strategy.

Steps:

Low/Medium-Resolution Validation:

- Techniques: Size-exclusion chromatography with multi-angle light scattering (SEC-MALS) to validate oligomeric state; Circular Dichroism (CD) to confirm secondary structure composition; Small-Angle X-ray Scattering (SAXS) to assess overall shape and dimensions [5].

- Interpretation: Does the predicted model have a calculated molecular weight and secondary structure profile that matches experimental data? Does the SAXS-derived envelope fit the predicted model?

High-Resolution Validation (Where Feasible):

- Techniques: X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM, or NMR spectroscopy [4] [5].

- Interpretation: This provides the most direct and conclusive validation. The atomic coordinates of the experimental structure can be superimposed on the predicted model to calculate root-mean-square deviation (RMSD). An all-atom accuracy of ~1.5 Å RMSD is considered highly accurate [5].

Functional Validation (Essential):

- Techniques: Site-directed mutagenesis of predicted active site or binding interface residues, followed by functional activity assays or binding studies (e.g., Surface Plasmon Resonance - SPR) [5].

- Interpretation: If mutations of computationally predicted critical residues ablates function, this provides strong corroborating evidence for the model's accuracy. This is particularly important for assessing the structure of flexible loops or allosteric sites that may be poorly modeled [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Protein Stability and Aggregation Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Stabilizing Excipients | Preferentially hydrate the protein surface, shifting equilibrium toward the folded state. | Sucrose, trehalose, sorbitol used in final formulation to enhance shelf-life [3]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80) | Compete with protein for interfaces, reducing surface-induced denaturation. | Added to protein solutions to prevent aggregation during pumping, filtration, and shipping [3]. |

| Chaotropes (e.g., Urea, GdnHCl) | Denature proteins by disrupting hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. | Used in chemical denaturation experiments to measure protein stability (ΔG) and unfolding transitions [1]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevent proteolytic cleavage that can generate truncated, aggregation-prone species. | Added to lysis and purification buffers to maintain protein integrity during isolation [2]. |

| Reducing Agents (e.g., DTT, TCEP) | Maintain cysteine residues in reduced state, preventing incorrect disulfide bond formation. | Critical for handling proteins in non-native environments where disulfide scrambling can occur [3]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Purify protein based on size, charge, or affinity to isolate monodisperse species. | Size-exclusion chromatography (SEC) is essential for separating and quantifying monomeric protein from aggregates [2]. |

| Stability Screening Kits | Enable high-throughput testing of multiple buffer conditions in small volumes. | Used to rapidly identify optimal pH, salt, and excipient conditions for maximizing stability [3]. |

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guide

This section addresses common experimental challenges in proteostasis research, providing targeted solutions based on the molecular mechanisms of the proteostasis network.

FAQ 1: My protein of interest is aggregating during expression and purification. What are the primary cellular systems that should prevent this, and how can I mimic them in vitro?

- Answer: Aggregation occurs when the cellular proteostasis network is overwhelmed or unavailable in vitro. The key is to replicate the function of molecular chaperones, the core components of this network.

- Primary Cellular Defenses:

- Hsp70 System: Binds to hydrophobic patches on nascent or misfolded chains, preventing inappropriate interactions [6] [7]. The ATP-dependent binding and release cycle facilitates proper folding.

- Small Heat Shock Proteins (sHsps): Act as the first line of defense by binding partially folded proteins and preventing them from forming irreversible aggregates, effectively "storing" them for later refolding [8] [9].

- Hsp90 System: Manages the folding and activation of specific "client" proteins, many of which are involved in signaling [7] [9].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Reduce Expression Stress: Lower the induction temperature (e.g., to 18-25°C) and use a lower inducer concentration (e.g., 0.1-0.5 mM IPTG) to slow down protein synthesis and give the host cell's chaperones more time to function [7].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express your target protein with chaperone systems like Hsp70 (DnaK in E. coli) and its co-chaperones (DnaJ, GrpE) or the GroEL/GroES chaperonin system [7].

- Modify Buffer Conditions In Vitro: Include molecular chaperone mimics in your purification buffers. This can include:

- Non-specific holdases: Add high concentrations of arginine (0.4-0.8 M) or other kosmotropes to suppress protein-protein interactions.

- ATP-regeneration systems: If using purified chaperones like Hsp70, ensure the buffer contains ATP and an ATP-regeneration system (e.g., Creatine Phosphate and Creatine Kinase) to power their folding cycles [6] [9].

- Primary Cellular Defenses:

FAQ 2: How can I experimentally determine if a misfolded protein is being targeted for degradation versus refolding by the proteostasis network?

- Answer: The cell makes a "triage" decision on misfolded proteins, primarily guided by chaperone interactions. You can dissect this pathway using specific inhibitors and tracking methods.

- Experimental Protocol:

- Pulse-Chase Analysis: Metabolically label newly synthesized proteins with a radioactive amino acid (e.g., ^35^S-Methionine) for a short "pulse," then chase with an excess of unlabeled amino acid. Monitor the disappearance of the misfolded protein and the appearance of degradation products over time.

- Inhibitor-Based Pathway Identification:

- For Ubiquitin-Proteasome System (UPS): Treat cells with a proteasome inhibitor like MG-132 or Bortezomib. Accumulation of ubiquitinated forms of your protein (detectable by western blot) indicates it is a UPS substrate [6] [10].

- For Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP): Treat cells with autophagy inhibitors such as Bafilomycin A1 (inhibits lysosomal acidification) or Chloroquine. Stabilization of your protein suggests ALP-mediated degradation [6] [11].

- Monitor Chaperone Association: Use co-immunoprecipitation to check for stable interactions between your protein and specific chaperones. A persistent interaction with Hsp70, especially in the presence of the co-chaperone CHIP (an E3 ubiquitin ligase), strongly suggests targeting to the UPS for degradation [6] [7].

- Experimental Protocol:

FAQ 3: My research focuses on a neurodegenerative disease model with persistent protein aggregates. What are the known cellular mechanisms for dissolving these aggregates, and why might they be failing?

- Answer: Persistent aggregates indicate a failure in the disaggregation and clearance arms of the proteostasis network.

- Cellular Disaggregation Machinery:

- The Metazoan Disaggregase: Unlike yeast and bacteria which use Hsp104, mammalian cells employ a complex of Hsp70, its nucleotide exchange factor Hsp110, and the J-domain protein Hsp40. This complex can use ATP hydrolysis to forcefully unfold and solubilize protein aggregates [6] [8].

- Post-Disaggregation Triage: After solubilization, proteins are either refolded with chaperone assistance or, if refolding fails, ubiquitinated and degraded [8].

- Reasons for Failure:

- Overwhelming Aggregate Load: In diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, the sheer volume of aggregates (e.g., Aβ, α-synuclein) may exceed the capacity of the disaggregation machinery [11] [12].

- Age-Related Decline: The expression and activity of key proteostasis network components, including Hsp70, decline with age, which is the primary risk factor for most neurodegenerative diseases [11] [7].

- Sequestration of Machinery: The aggregates themselves can actively sequester essential chaperones and proteasome components, functionally depleting the cell's ability to respond to proteotoxic stress [11] [7].

- Experimental Approach: Quantify the mRNA and protein levels of key disaggregation components (Hsp70, Hsp110, Hsp40) in your disease model versus controls. A knockdown or knockout of these components in your model should exacerbate the aggregation phenotype, confirming their functional role.

- Cellular Disaggregation Machinery:

FAQ 4: What are the key differences in how the proteostasis network handles cytosolic protein misfolding versus misfolding in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)?

- Answer: While the core principles are similar, the compartments use distinct machineries and signaling pathways.

- Cytosolic Misfolding:

- Endoplasmic Reticulum Misfolding (ERAD):

- Primary Chaperones: BiP (an Hsp70 homolog), Calnexin/Calreticulin (for glycoproteins) [1] [11].

- Degradation Pathway: ER-associated degradation (ERAD). Misfolded proteins are retro-translocated into the cytosol, ubiquitinated, and degraded by the proteasome [1] [11].

- Stress Response: The Unfolded Protein Response (UPR), which has three main sensors (IRE1, PERK, ATF6) that work to reduce protein load and increase folding capacity in the ER [1] [11].

The table below summarizes the quantitative data on proteostasis network associations with major disease classes, highlighting key therapeutic targets.

Table 1: Proteostasis Network Signatures in Human Diseases. Data derived from large-scale pan-disease analysis showing the over-representation of proteostasis network components in disease gene sets [10].

| Disease Category | Fraction of Disease Gene Set Composed of Proteostasis Proteins | Key Over-Represented Pathways | Key Over-Represented Functional Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer | 25% - 36% | UPS, Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP) | UPS E3 Ligases, Transcription Factors |

| Neurodegenerative Diseases | 30% - 35% | UPS, ALP, Extracellular Proteostasis | Molecular Chaperones, UPS Ubiquitin-Binding Proteins |

| Cardiovascular, Autoimmune, Endocrine | 20% - 30% | ALP, Extracellular Proteostasis | Molecular Chaperones, Transcription Factors |

Key Experimental Protocols

This section provides detailed methodologies for critical experiments investigating chaperone function and protein quality control.

Protocol 1: Assessing Protein Disaggregation Activity In Vitro

- Objective: To reconstitute and measure the disaggregation of a model protein aggregate by the Hsp70/Hsp110/Hsp40 chaperone system.

- Background: This protocol tests the function of the core metazoan disaggregation machinery, which is crucial for reversing protein aggregation in neurodegenerative disease models [6] [8].

- Materials:

- Purified chaperones: Hsp70, Hsp110 (NEF), Hsp40 (J-protein).

- Model substrate (e.g., heat-denatured, aggregated Luciferase or GFP).

- ATP-regeneration system (ATP, Creatine Phosphate, Creatine Kinase).

- Reaction buffer (e.g., 40 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.4, 50 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2).

- Thermoshaker and plate reader (for luciferase/GFP activity).

- Methodology:

- Prepare Aggregated Substrate: Denature the model protein (e.g., 2 µM Luciferase) by heating at 42°C for 20-30 minutes. Confirm aggregation by dynamic light scattering or turbidity measurement.

- Set Up Disaggregation Reaction: In a reaction tube, combine:

- Reaction buffer.

- ATP-regeneration system (1-2 mM ATP, 10 mM Creatine Phosphate, 0.1 µM Creatine Kinase).

- Aggregated substrate.

- Chaperone mix (e.g., 2-5 µM Hsp70, 1-2 µM Hsp110, 1-2 µM Hsp40).

- Incubate and Monitor: Incubate the reaction at 30-37°C. For luciferase, take aliquots at regular intervals (e.g., 0, 15, 30, 60, 90, 120 min) and measure recovered enzymatic activity using a luminometer upon adding substrate. For GFP, monitor fluorescence recovery over time.

- Controls: Include essential negative controls: a reaction with no ATP and a reaction missing one key chaperone (e.g., Hsp110).

- Data Analysis: Plot the percentage of recovered activity over time. A successful disaggregation reaction will show a time-dependent increase in signal, dependent on the presence of all chaperones and ATP.

Protocol 2: Differentiating Degradation Pathways for a Misfolded Protein

- Objective: To determine whether a misfolded protein of interest is degraded by the proteasome or via autophagy in living cells.

- Background: Misfolded proteins are triaged for degradation primarily by the UPS or ALP. Identifying the correct pathway is essential for understanding disease mechanisms and designing interventions [6] [10].

- Materials:

- Cell line expressing your protein of interest.

- Cycloheximide (protein synthesis inhibitor).

- Proteasome inhibitor (e.g., MG-132, 10-20 µM).

- Autophagy/Lysosome inhibitor (e.g., Bafilomycin A1, 100 nM).

- Antibodies for your protein and a loading control (e.g., GAPDH, Tubulin).

- Methodology:

- Treat Cells: Split cells into four treatment groups in 6-well plates:

- Group 1 (Control): DMSO vehicle control.

- Group 2 (Proteasome Inhibition): MG-132.

- Group 3 (Autophagy Inhibition): Bafilomycin A1.

- Group 4 (Dual Inhibition): MG-132 + Bafilomycin A1.

- Block New Synthesis: After pre-treating with inhibitors for 1 hour, add Cycloheximide (50-100 µg/mL) to all groups to stop new protein synthesis. This allows you to monitor the decay of the existing protein pool.

- Harvest and Analyze: Harvest cells at specific time points after Cycloheximide addition (e.g., 0, 2, 4, 8 hours). Prepare whole-cell lysates and perform a western blot for your protein of interest.

- Quantify: Quantify the band intensity relative to the loading control and the time-zero point.

- Treat Cells: Split cells into four treatment groups in 6-well plates:

- Data Interpretation:

- If the protein stabilizes (decays slower) only with MG-132, it is primarily a UPS substrate.

- If it stabilizes only with Bafilomycin A1, it is primarily an autophagy substrate.

- If it stabilizes most significantly with dual inhibition, it is likely degraded by both pathways.

Proteostasis Network Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the key signaling pathways that regulate the proteostasis network, central to experimental design in protein stability research.

Cytosolic Heat Shock Response

Chaperone-Mediated Protein Triage

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential reagents for studying molecular chaperones and protein quality control, with explanations of their specific functions in experimental contexts.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Proteostasis Network Studies

| Research Reagent | Function / Mechanism of Action | Key Experimental Use |

|---|---|---|

| MG-132 / Bortezomib | Reversible inhibitors that bind the proteasome's catalytic subunits, blocking chymotryptic activity. | To determine if a protein is degraded by the UPS. Stabilization of the protein upon treatment indicates it is a proteasome substrate [6] [10]. |

| Bafilomycin A1 | A specific vacuolar-type H+-ATPase (V-ATPase) inhibitor. Prevents lysosomal acidification, blocking autophagic degradation. | To inhibit the Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway (ALP). Used to distinguish ALP-dependent degradation from UPS-dependent degradation [6] [11]. |

| Recombinant Chaperone Proteins (Hsp70, Hsp40, Hsp110) | Purified, active human or bacterial chaperones. Function in an ATP-dependent manner to bind, refold, or disaggregate substrate proteins in vitro. | For in vitro reconstitution assays to study the mechanism of protein folding, disaggregation, and the specific roles of individual chaperones in these processes [6] [8] [9]. |

| ATP-Regeneration System | A cocktail of ATP, creatine phosphate, and creatine kinase. The kinase continuously regenerates ATP from ADP using the phosphate donor, maintaining constant ATP levels. | Essential for any in vitro chaperone assay (folding, disaggregation) as most chaperones are ATP-dependent enzymes. Prevents artifact from ATP depletion [9]. |

| HSF1 Activators (e.g., Celastrol) | Small molecules that activate the Heat Shock Transcription Factor 1 (HSF1), leading to upregulated expression of endogenous chaperones like Hsp70. | To test whether boosting the cell's intrinsic proteostasis capacity can alleviate protein misfolding and aggregation in cellular disease models [7]. |

| Clusterin | An extracellular holdase chaperone that binds to a wide range of misfolded proteins, including Aβ and α-synuclein, to prevent their aggregation. | Used in vitro and in cell models to study the suppression of amyloid formation and to investigate the role of extracellular proteostasis in protein aggregation diseases [9]. |

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is fundamental to cellular health. It represents the delicate balance between protein synthesis, folding, trafficking, and degradation that maintains a functional proteome [13]. When this balance is disrupted—through genetic mutations, cellular stress, or aging—proteins may misfold and aggregate, leading to a pathological state known as dysproteostasis [13]. In neurodegenerative diseases and loss-of-function disorders, this aggregation process is not merely a secondary symptom but a primary driver of pathology, contributing to both toxic gain-of-function effects and critical loss of normal cellular activities [14] [15] [16]. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and foundational knowledge for researchers investigating these complex mechanisms, framed within the broader context of designing stable proteins to prevent misfolding and aggregation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs): Core Concepts

1. What is the fundamental link between protein misfolding and aggregation in neurodegenerative diseases?

Proteins fold into specific three-dimensional structures to perform their biological functions. The "thermodynamic hypothesis," established by Christian Anfinsen's work, states that a protein's native structure is determined by its amino acid sequence and represents the most thermodynamically stable conformation under physiological conditions [13]. Misfolding occurs when polypeptides deviate from this correct folding pathway, often due to factors like genetic mutations or oxidative stress [13] [17]. These misfolded proteins can then self-assemble into aggregates. In major neurodegenerative conditions like Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), specific proteins such as amyloid-β, tau, α-synuclein, and TAR DNA-binding protein 43 (TDP-43) form amyloid fibrils that undergo prion-like propagation throughout the nervous system, ultimately inducing neurodegeneration [14].

2. How can protein aggregation simultaneously cause gain-of-function and loss-of-function pathologies?

Aggregation can lead to a dual pathology: a toxic gain-of-function from the aggregated protein itself and a critical loss-of-function due to the depletion of the normal, functional protein.

- Gain-of-Function: The aggregates themselves can be toxic. They may disrupt cellular membranes, impair the function of organelles, and overwhelm the cellular protein quality control systems [17]. For instance, cytoplasmic TDP-43 inclusions recruit essential proteins, sequestering them away from their normal functions [16] [18].

- Loss-of-Function: The aggregation process depletes the pool of functional, soluble protein. In the nucleus, depletion of TDP-43 leads to a loss of its normal role in RNA metabolism, resulting in aberrant cryptic splicing and disrupted gene expression, which is a direct loss-of-function pathology [16] [18]. Similarly, a 2025 study on GGC repeat disorders showed that polyglycine aggregates specifically recruit and deplete the tRNA ligase complex, disrupting essential tRNA processing and mimicking genetic tRNA splicing disorders [19].

3. What are the primary molecular mechanisms by which genetic mutations cause disease through protein aggregation?

Disease-causing mutations in protein-coding regions can be broadly categorized into three molecular mechanisms, each with distinct therapeutic implications [15]:

- Loss-of-Function (LOF): Mutations (e.g., premature stop codons or destabilizing missense changes) lead to a reduction or complete absence of the protein's normal activity. Therapeutic strategies often aim to replace or compensate for the missing function, such as with gene therapy [15].

- Gain-of-Function (GOF): Mutations cause the protein to acquire a new, often toxic, function or increased activity. This includes forming toxic aggregates. Therapies typically involve inhibiting the mutant protein's function using small molecules or gene silencing [15].

- Dominant-Negative (DN): The mutant protein interferes with the function of the wild-type protein, for example, by forming dysfunctional complexes. Therapeutic approaches may involve allele-specific targeting to silence the mutant allele [15]. A 2025 study estimated that dominant-negative and gain-of-function mechanisms account for 48% of phenotypes in dominant genes, highlighting the prevalence of non-LOF mechanisms in aggregation diseases [15].

4. Beyond neurodegeneration, what are some unexpected cellular functions affected by protein aggregation?

Recent research has revealed novel and unexpected pathways disrupted by aggregation. The 2025 study on GGC repeat disorders demonstrated that polyglycine aggregates do not just cause generic cellular stress but can specifically sequester the tRNA ligase complex (tRNA-LC) [19]. This recruitment depletes the cell of functional tRNA-LC, leading to misprocessed tRNAs and disrupting global protein synthesis. This mechanism directly links protein aggregation to RNA processing disorders and explains the selective neuronal vulnerability observed in these diseases [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Common Protein Solubility and Aggregation Issues in Vitro

Problem: Your recombinant protein is forming aggregates or precipitating during expression, purification, or storage.

Solution: A systematic approach to optimize buffer conditions and protein handling.

| Issue Area | Possible Cause | Recommended Action | Theoretical Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffer Conditions | Non-optimal pH or ionic strength leading to instability. | Adjust pH to the protein's stable point (often near its isoelectric point). Modulate ionic strength; add salts like NaCl to shield electrostatic attractions. | Solubility is highly dependent on the protein's net charge and the electrostatic environment [20]. |

| Physical Stress | Exposure to high temperatures, shaking, or air-liquid interfaces. | Work at lower temperatures (4°C). Avoid vigorous shaking; use gentle pipetting. Add non-denaturing detergents for membrane proteins. | Proteins can become unstable and denature at high temperatures or due to surface-induced stresses, initiating the aggregation pathway [21]. |

| Additives | Lack of stabilizing agents in the solution. | Include additives like glycerol, polyethylene glycol (PEG), or amino acids (e.g., arginine). Test different molecular chaperones. | These additives can stabilize proteins by providing a more favorable chemical environment, reducing protein-protein interactions, or actively assisting folding [20]. |

| Protein Sequence | Hydrophobic residues on the protein surface promoting interaction. | Use site-directed mutagenesis to replace surface hydrophobic residues with hydrophilic ones. | This reduces the hydrophobic interactions that are a primary driver of protein aggregation [20]. |

| Expression System | Incorrect folding in a non-optimal host (e.g., E. coli). | Switch expression system (e.g., yeast, insect, or mammalian cells) to obtain necessary post-translational modifications and chaperones. | Different host systems offer varying components of the proteostasis network, which is crucial for proper folding [20]. |

Experimental Protocol: Refolding Proteins from Inclusion Bodies If solubility cannot be achieved and the protein is trapped in inclusion bodies, refolding is a potential solution [20].

- Solubilization: Isolate inclusion bodies and solubilize the aggregated protein using a strong denaturant, such as 6-8 M guanidine hydrochloride or 8 M urea.

- Purification: Purify the denatured protein under denaturing conditions if possible (e.g., using affinity chromatography).

- Refolding: Dilute the denatured protein slowly into a refolding buffer. This buffer should contain:

- A redox system (e.g., reduced/oxidized glutathione) to facilitate disulfide bond formation.

- Stabilizing additives like arginine, glycerol, or PEG.

- A pH and salt concentration optimized for the target protein.

- Concentration and Characterization: Concentrate the refolded protein and thoroughly characterize its activity and monodispersity using techniques like size-exclusion chromatography and circular dichroism.

Guide 2: Selecting Analytical Techniques for Protein Aggregate Characterization

Problem: You need to characterize the size, amount, and type of aggregates in your protein sample, but the available techniques are numerous and varied.

Solution: Employ a combination of orthogonal methods to cover the wide size range and different properties of protein aggregates. The table below summarizes key techniques. No single method can provide a complete picture; a strategic combination is essential [21].

| Method | Principle | Size Range | Key Information | Main Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) | Fluctuations in scattered light due to Brownian motion. | 1 nm - 6 μm | Hydrodynamic size distribution, sample homogeneity. | Does not resolve complex mixtures well; sensitive to dust/large particles. |

| Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) | Sedimentation under high centrifugal force. | ~0.1 nm - 1 μm | Mass and shape information; can separate and quantify species. | Low throughput; requires significant expertise and data analysis. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Size-based separation of molecules in solution. | ~1 - 30 nm (hydrodynamic radius) | Quantification of soluble aggregates (dimers, trimers) relative to monomer. | May not detect large aggregates that stick to the column matrix. |

| Micro-Flow Imaging / Flow Microscopy | Microscopic imaging of particles in a flow cell. | 1 - 400 μm | Concentration, size, and morphology of particles; can differentiate protein from other particles. | Generates large data volumes; emerging technique for subvisible particles. |

| Native Gel Electrophoresis | Separation by size and charge under non-denaturing conditions. | Varies | Identification of soluble oligomeric species. | Semi-quantitative; may not be suitable for very large aggregates. |

The following workflow diagram illustrates a recommended strategy for characterizing protein aggregates throughout product development, from early discovery to quality control, based on guidance from the European Immunogenicity Platform [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Chaperones (e.g., Hsp70, Hsp40, Hsp104) | Assist in proper protein folding, prevent aggregation, refold misfolded proteins, and disaggregate existing aggregates [13] [17]. | Hsp104 is present in yeast and crucial for prion propagation but absent in metazoans, where disaggregation is handled by Hsp70/Hsp40/Hsp110 systems [17]. |

| TDP-43 Low-Complexity Domain Fibrils | Pre-formed amyloid-like fibrils used to seed TDP-43 aggregation in cellular models (e.g., iPSC-derived neurons) to study ALS/FTD pathology [16] [18]. | This model robustly recapitulates both cytoplasmic inclusion formation and nuclear loss-of-function, key hallmarks of TDP-43 proteinopathies. |

| Small Molecule Chaperone Modulators | Pharmacologically manipulate the proteostasis network. For example, small molecule Hsp90 inhibitors have shown success in ameliorating tau and Aβ burden in models of Alzheimer's disease [17]. | The pharmacology of current scaffolds can be challenging, driving research into targeting specific co-chaperones for improved specificity [17]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Systematically replace hydrophobic surface residues with hydrophilic ones to engineer proteins with enhanced solubility and reduced aggregation propensity [20]. | Requires prior structural knowledge to avoid disrupting the protein's active site or core functional domains. |

| tRNA Ligase Complex (tRNA-LC) Components | Key reagents for studying a novel aggregation pathway in GGC repeat disorders, where polyglycine aggregates sequester tRNA-LC, disrupting tRNA processing and leading to neurodegeneration [19]. | Studying this complex provides a direct link between protein aggregation and RNA processing defects, revealing a new therapeutic target. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Q1: My HSP90 inhibition experiment is producing unexpected results in a Hepatovirus model. Could previous assumptions about its necessity be incorrect?

A1: Yes, recent research has overturned the long-held assumption that Hepatitis A virus (HAV) replication is independent of HSP90. If your experiments are not showing an effect, consider the inhibitor concentration and model system.

- Key Evidence: A 2025 study demonstrates that HAV replication is highly dependent on HSP90 chaperone activity, both in human hepatocyte-derived cell lines and in vivo mouse models. The 50% inhibitory concentration (IC50) of the HSP90 inhibitor geldanamycin was found to be very low (8.7-11.8 nM), indicating high potency [22].

- Troubleshooting Tip: Ensure you are using a potent and specific HSP90 inhibitor at an appropriate concentration. The previous hypothesis that HAV's slow translational kinetics made it HSP90-independent has been refuted; it is now considered more dependent on HSP90 than some other picornaviruses [22].

Q2: I am engineering cell factories for therapeutic protein production, but sustained UPR activation is leading to high apoptosis. How can I dynamically control this response to improve yields?

A2: Static overexpression of UPR components often fails due to cellular adaptation and toxicity. Implement a feedback-responsive system that senses proteotoxic stress and modulates the UPR dynamically.

- Recommended Protocol: Engineer sense-and-respond circuits that:

- Expected Outcome: This dynamic control, as demonstrated with tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) and blinatumomab, enhances cell viability and increases the production of functional, secreted protein by aligning UPR modulation with real-time folding demands [23].

Q3: Can modulating the Unfolded Protein Response (UPR) be a viable strategy for treating complex neurodegenerative diseases like ALS/FTD?

A3: Emerging evidence suggests that artificially enforcing a specific arm of the UPR could be a promising pan-therapeutic strategy for diseases characterized by proteostasis failure.

- Experimental Insight: Intracerebroventricular administration of AAVs to express the active, spliced form of XBP1 (XBP1s) in ALS/FTD models improved motor performance, extended lifespan, and reduced protein aggregation. This was effective in models of SOD1, TDP-43, and C9orf72 pathogenesis [24].

- Mechanism: XBP1s is a master transcription factor that upregulates genes involved in ER protein folding, quality control, and degradation. Its overexpression compensates for the suboptimal UPR activation observed in these disease models, improving overall proteostasis [24].

Q4: How can I accurately measure the effects of thousands of mutations on protein folding stability in a high-throughput manner?

A4: Traditional methods are low-throughput. Implement the cDNA display proteolysis method, which can measure thermodynamic folding stability for up to hundreds of thousands of protein variants in a single experiment [25].

- Workflow Summary:

- Create a DNA library of your protein variants.

- Use cell-free cDNA display to create protein-cDNA complexes.

- Incubate with a series of protease concentrations. Folded proteins are protease-resistant.

- Pull down intact proteins and use deep sequencing to quantify survival rates for each sequence.

- Apply a kinetic model to infer thermodynamic folding stability (ΔG) from the sequencing data [25].

- Advantage: This method is fast, accurate, and uniquely scalable, allowing you to uncover the quantitative rules of how sequence encodes stability [25].

Table 1: HSP90 Inhibitors in Antiviral and Neurological Research

| Inhibitor Name | Target | Key Experimental Context | Potency (IC50/Kd) | Key Findings & Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geldanamycin [22] | HSP90 | Hepatitis A Virus (HAV) Replication | 8.7-11.8 nM | Potently blocks HAV replication in vitro and in vivo; more potent for HAV than other picornaviruses [22]. |

| [11C]HSP990 [26] | HSP90 (Brain) | PET Neuroimaging in Neurodegeneration | Kd = 1.6 nM (Human brain homogenate) | Successful PET tracer for quantifying brain Hsp90; shows reduced binding in Alzheimer's model brain tissue [26]. |

| [11C]BIIB021 [26] | HSP90 (Brain) | PET Neuroimaging | Information in source | Exhibits Hsp90-specific binding in rat brain; presence of brain radiometabolites complicates quantification [26]. |

| PU-AD [26] | HSP90 | Therapeutic / Imaging for Alzheimer's | Information in source | Showed promise in preclinical studies; evaluated in clinical trials (withdrawn/terminated) [26]. |

Table 2: High-Throughput Protein Folding Stability Analysis (cDNA Display Proteolysis)

| Parameter | Specification | Relevance for Experimental Design |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput [25] | ~900,000 protein domains per one-week experiment | Enables comprehensive mutational scans and stability landscapes. |

| Cost [25] | ~$2,000 per library (excluding DNA synthesis/sequencing) | Cost-effective for the scale of data generated. |

| Data Accuracy [25] | R = 0.94 (between trypsin & chymotrypsin experiments) | High reproducibility and reliability of inferred ΔG values. |

| Typical Library [25] | All single amino acid variants and selected double mutants of 331 natural and 148 de novo designed domains | Provides a uniform, comprehensive dataset for machine learning and biophysical analysis. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing HSP90 Dependency in Viral Replication Using Inhibitors

This protocol is adapted from research confirming HSP90's critical role in Hepatitis A virus replication [22].

- Cell Culture and Infection: Use relevant host cells (e.g., human hepatocyte-derived cell lines). Infect with the virus of interest at an appropriate multiplicity of infection (MOI).

- Inhibitor Treatment: Prepare a dilution series of a validated HSP90 inhibitor (e.g., geldanamycin). Treat cells with the inhibitor concurrently with or shortly after viral infection. Include a DMSO vehicle control.

- Cytotoxicity Assay: Perform a parallel cytotoxicity assay (e.g., MTT, LDH) to ensure that antiviral effects are not due to general cell death. The IC50 for viral inhibition should be significantly lower than the cytotoxic concentration.

- Replication Quantification:

- For productive infection: Measure viral titers using plaque assays or TCID50 at 24-48 hours post-infection.

- For replication mechanisms: Use subgenomic replicon systems to directly assess the role of HSP90 in RNA amplification independent of capsid assembly [22].

- Downstream Analysis: To probe the mechanism, perform label-free quantitative proteomics to identify which viral proteins (e.g., capsid precursors) interact with HSP90 [22].

Protocol 2: Engineering Feedback-Responsive Cell Factories for Dynamic UPR Control

This protocol outlines the creation of engineered cells that autonomously manage ER stress to enhance recombinant protein production [23].

- Sensor Construction: Create an ER stress sensor by placing a transcriptional regulator (e.g., tTA) under the control of a UPR target promoter, such as the one for the XBP1s-target gene ERdj4 [23].

- Actuator Engineering:

- For Stress Attenuation: Design a circuit where the sensor activates expression of the active transcription factor XBP1s, creating a positive feedback loop to amplify the pro-folding arm of the UPR [23].

- For Apoptosis Delay: Design a separate circuit where the sensor drives expression of a repressor that targets the pro-apoptotic gene CHOP [23].

- Cell Line Generation: Stably integrate these sense-and-respond circuits into your production cell line (e.g., CHO or HEK293).

- Validation and Production:

- Characterization: Induce recombinant protein expression and use fluorescent reporters to monitor the dynamic activation of the sensor and actuator pathways over time.

- Performance Metrics: Compare cell viability, duration of protein production, and final functional titer of the therapeutic protein (e.g., tPA or bispecific antibodies) against control cell lines lacking the dynamic circuits [23].

Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated Cellular Stress Response Pathways

Diagram 2: cDNA Display Proteolysis Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Stress Response Research

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| HSP90 Inhibitors (e.g., Geldanamycin, 17-AAG) [22] [27] | Probing HSP90 function in viral replication, cancer, and neurodegeneration. | Potent, ATP-competitive inhibitors. Used to dissect chaperone-client relationships and as therapeutic leads. |

| UPR Reporter Cell Lines [23] | Quantifying activation of specific UPR branches (IRE1, PERK) in real-time. | Typically use GFP under control of UPR target promoters (e.g., ERdj4 for IRE1, CHOP for PERK). Enable dynamic, single-cell resolution. |

| cDNA Display Proteolysis Kit (Conceptual) [25] | High-throughput measurement of protein folding stability for vast variant libraries. | Components for cell-free translation, protease digestion, and cDNA-protein pull-down. Requires NGS capabilities. |

| AAV-XBP1s Vectors [24] | Gene therapy approach to artificially enforce the adaptive UPR in disease models. | Used to deliver the active XBP1s transcription factor to tissues (e.g., CNS) to improve proteostasis and reduce aggregation. |

| Hsp90 PET Tracers (e.g., [11C]HSP990) [27] [26] | Non-invasive in vivo visualization and quantification of Hsp90 expression in the brain. | Critical for validating target engagement of Hsp90 drugs in the CNS and as potential diagnostic biomarkers for neurodegeneration. |

Computational Arsenal: AI, Physics, and De Novo Design for Stable Proteins

Welcome to the Technical Support Center

This support center is designed for researchers and scientists employing machine learning predictors for protein stability design. The guides and FAQs below will help you troubleshoot specific issues encountered while using RaSP or meta-predictors in experiments aimed at preventing pathogenic protein misfolding and aggregation.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

General Predictor Concepts

Q1: What is the core difference between a meta-predictor and a tool like RaSP?

A meta-predictor integrates the predictions of multiple independent computational tools to form a single, consensus prediction. This approach mitigates the individual biases and limitations of any single tool. For instance, one study combined 11 different tools into a meta-predictor, which demonstrated improved performance and reliability over any individual component [28].

In contrast, RaSP (Rapid Stability Prediction) is a specific, deep learning-based method. It uses a self-supervised 3D convolutional neural network to learn representations of protein structure, which is then fine-tuned in a supervised manner to predict changes in thermodynamic stability (ΔΔG) on an absolute scale [29].

Q2: Why might my predicted stabilizing mutation still cause the protein to aggregate?

This is a common challenge. Computational tools often increase predicted stability by recommending mutations that increase the hydrophobicity of the protein surface. While this can improve stability, it frequently does so at the cost of solubility, leading to aggregation. Analysis of a large mutation dataset confirmed that stabilizing mutations on the protein surface are strongly correlated with increased hydrophobicity [28]. Always check if a predicted stabilizing mutation introduces hydrophobic residues in solvent-exposed areas.

RaSP-Specific Workflow

Q3: What is the typical workflow for running a RaSP analysis, and where do errors most often occur?

The standard workflow and common failure points are outlined below. Errors most frequently occur during the input preparation stage, specifically with incorrect PDB file formatting or selection.

Q4: RaSP is reporting high errors for specific amino acid substitutions. Is this a known issue?

Yes, the accuracy of RaSP is not uniform across all mutation types. The model exhibits larger prediction errors when substituting glycine residues or when changing residues to proline. This is likely due to the unique conformational constraints these amino acids impose [29]. Treat predictions involving these residues with extra caution.

Meta-Predictor Specifics

Q5: Which individual tools are commonly integrated into a stability meta-predictor?

A proven meta-predictor can incorporate a diverse set of tools. The following table lists tools that have been successfully combined, leveraging their complementary strengths for different mutation types [28].

| Tool Name | Underlying Methodology | Key Strengths / Profile |

|---|---|---|

| FoldX | Empirical Force Field | Accurate for mutations increasing hydrophobicity [28] |

| Rosetta-ddG | Empirical & Physical Force Field | Accurate for mutations increasing hydrophobicity [28] |

| EGAD | Physical Force Field | Accurate for mutations increasing hydrophobicity [28] |

| PoPMuSiC | Statistical Potential | Accurate for mutations that reduce or do not change hydrophobicity [28] |

| CUPSAT | Statistical Potential | Accurate for mutations that reduce or do not change hydrophobicity [28] |

| SDM | Statistical Potential | Accurate for mutations that reduce or do not change hydrophobicity [28] |

| DFire | Statistical Potential | Good overall performance, especially on buried residues [28] |

| IMutant3 | Machine Learning/Neural Network | Less reliable for surface-exposed residues [28] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Predictions Contradict Experimental Stability Data

Problem: Your in silico screening identifies mutations predicted to be highly stabilizing, but subsequent experimental characterization (e.g., thermal shift assays) shows they are neutral or even destabilizing.

Solution:

- Verify Structural Context: The accuracy of most predictors, including RaSP and tools within a meta-predictor, is highest for buried residues and lower for surface-exposed ones [28]. Check the location of your mutated residue.

- Check for Functional/Allosteric Residues: A mutation might be structurally stabilizing but disrupt allosteric networks or functional sites. Avoid residues implicated in function, such as active sites or binding pockets. In one case, excluding 21 functional residues was crucial for maintaining the glycan-binding capacity of ThreeFoil while stabilizing it [28].

- Audit Your Input Structure: Ensure the protein structure file (PDB) used for prediction is of high resolution and relevant to your experimental conditions. Mismatches here are a common source of discrepancy.

- Consider the Solubility Trade-off: The mutation may indeed increase thermodynamic stability but cause aggregation, which can be misinterpreted as instability in some assays. Run complementary aggregation predictors or inspect the mutation for increased surface hydrophobicity [28].

Issue 2: Handling the Stability-Solubility Trade-off

Problem: Successfully designed stabilized protein variants show a tendency to aggregate, reducing yield and usability for therapeutic or biotechnological applications.

Solution:

- Post-Prediction Filtering: After generating a list of candidate stabilizing mutations, filter out those that:

- Increase hydrophobicity on the protein surface.

- Reduce net charge or create patches of neutral charge.

- Prioritize Core Mutations: Focus stabilization efforts on residues that are buried in the protein core, as these are less likely to negatively impact solubility [28].

- Iterative Design: Use the stabilized variant as a new backbone and run further prediction rounds, explicitly filtering for solubility. Machine learning models are increasingly being trained to recognize this balance.

Issue 3: RaSP Model Performance and Validation

Problem: You need to understand the expected performance and limitations of the RaSP model to justify its use in your study or a publication.

Solution: Refer to the published benchmarks of RaSP against experimental and computational data. The table below summarizes key performance metrics [29].

| Validation Data Set | RaSP vs. Rosetta Correlation (Pearson ρ) | RaSP vs. Experimental Data Correlation (Pearson ρ) |

|---|---|---|

| RaSP Test Set (10 proteins) | 0.71 - 0.88 | - |

| Myoglobin (1BVC) | 0.91 | 0.71 |

| Lysozyme (1LZ1) | 0.80 | 0.57 |

| Protein G (1PGA) | 0.90 | 0.72 |

| NUDT15 (5BON) | 0.83 | 0.50 |

| PTEN (1D5R) | 0.87 | 0.52 |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material / Resource | Function in Experiment | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Target Protein Structure (PDB file) | Serves as the input for all structure-based prediction tools (RaSP, FoldX, Rosetta). | Use high-resolution (<2.5 Å) crystal structures. Consider the biological relevance of the specific conformation. |

| RaSP Web Server / Code | Provides rapid (sub-second per residue) predictions of ΔΔG for saturation mutagenesis. | Freely available via a web interface or local installation for large-scale analyses [29]. |

| Meta-Predictor Web Server | Combines multiple tools (e.g., FoldX, Rosetta, PoPMuSiC) to generate a consensus stability prediction. | An example implementation is available at meieringlab.uwaterloo.ca/stabilitypredict/ [28]. |

| Thermal Denaturation Assay | Experimentally validates the change in melting temperature (ΔTm) of designed variants. | The gold-standard for measuring changes in thermodynamic stability. Correlate ΔTm with predicted ΔΔG. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Assesses the solubility and aggregation state of stabilized protein variants. | Critical for identifying the stability-solubility trade-off. A stable but aggregated protein will show an altered elution profile. |

Experimental Protocol: Validating Predictor Output

This protocol describes a standard method for experimentally testing computationally predicted stabilizing mutations.

1. Protein Expression and Purification:

- Clone the gene for your wild-type and mutant proteins into an appropriate expression vector.

- Express the proteins in your chosen system (e.g., E. coli).

- Purify the proteins using affinity and size-exclusion chromatography to ensure homogeneity.

2. Thermodynamic Stability Assay (Differential Scanning Fluorimetry - DSF):

- Principle: This high-throughput method measures protein unfolding by monitoring a fluorescent dye that binds to hydrophobic patches exposed upon denaturation.

- Procedure:

- Mix purified protein with a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) in a quantitative PCR plate.

- Gradually increase the temperature (e.g., from 25°C to 95°C) while measuring fluorescence.

- Generate a melt curve for each variant. The midpoint of this curve is the melting temperature (Tm).

- Analysis: A higher Tm for a mutant compared to the wild-type indicates increased stability. The change in Tm (ΔTm) can be correlated with the predicted ΔΔG.

3. Functional and Solubility Validation:

- Activity Assay: Perform a functional assay specific to your protein (e.g., a glycan-binding assay for a lectin) to ensure stabilization did not compromise function [28].

- Aggregation Check: Use SEC-MALS (Multi-Angle Light Scattering) or dynamic light scattering (DLS) to check for soluble aggregates and confirm the monomeric state of the stabilized protein.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between QresFEP-2 and Rosetta ddg, and when should I use each? Both methods predict the effects of mutations on protein stability, but they use different approaches. You should choose based on your project's need for accuracy versus speed. QresFEP-2 is a hybrid-topology free energy perturbation protocol that uses molecular dynamics to provide high-accuracy, physics-based predictions, making it ideal for final candidate validation. In contrast, the Rosetta ddg monomer tool is a faster, semi-empirical method based on the Rosetta energy function, useful for initial screening to enrich a large set of mutations for promising variants [30] [31].

Q2: I am getting positive scores after pre-packing structures for docking in Rosetta. Is this normal? Yes, this can be expected. The pre-packing protocol separates protein partners, repacks them in an isolated state, and then recombines them without further optimization. This can introduce clashes across the interface, leading to positive scores and high Lennard-Jones repulsive and solvation energy terms. This procedure helps minimize native bias before a docking run [32].

Q3: What should I do if my Rosetta run fails with an "ERROR: Conformation: fold_tree nres should match conformation nres" message? This error indicates a mismatch between the number of residues in your protein's internal data and its fold tree, often due to missing residues in your input PDB file compared to a native reference structure. To resolve this, ensure all input PDB files have the same residues. You can remove the extra residues from the larger PDB file or add the missing residues back to the smaller one [32].

Q4: How can FEP simulations help in designing proteins resistant to misfolding and aggregation? Free Energy Perturbation simulations can accurately predict how point mutations affect a protein's folding free energy (ΔΔGfolding). By identifying mutations that lower the free energy of the native state relative to the unfolded state, FEP helps you design more thermostable variants. This enhanced stability reduces the population of partially unfolded states that are prone to form toxic aggregates, a key strategy in combating neurodegenerative diseases [30] [31].

Q5: My Rosetta run produced a "Segfault." What are the first steps to debug this? Segmentation faults are often caused by the software encountering an unexpected system state. First, check that all your input files are correct and in the expected format. Running the calculation in debug mode can convert a segfault into a more informative assertion error. Because segfaults can be complex, please report them to the Rosetta issue tracker on GitHub for developer attention [33].

Troubleshooting Common Errors

Rosetta Input and Configuration Errors

Many common Rosetta errors stem from problems with input files or command-line options. The table below summarizes frequent issues and their solutions.

| Error / Issue | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| ERROR: Value of inactive option accessed [33] | A required command-line option was not provided. | Add the missing option with an appropriate value. |

| ERROR: Conformation: fold_tree nres should match conformation nres [32] | Mismatch in residue counts between input PDB and native complex PDB. | Ensure all PDB files have the same residues; remove extras from the larger file or add missing ones to the smaller file. |

Assertion Error (e.g., ERROR: 0 < seqpos) [33] |

A core assumption of the protocol has been violated (e.g., an invalid residue position). | Check that inputs meet protocol requirements (e.g., correct number of chains, residue numbering). |

| "Segfault" (Segmentation Fault) [33] | Often a Rosetta bug triggered by an unanticipated system state. | Verify all input files. Run in debug mode for a better error message. File a bug report. |

| Positive scores after pre-packing [32] | Side-chain clashes introduced by repacking proteins in isolation. | This is normal and part of reducing native bias before docking. Proceed with the docking protocol. |

| Poor correlation with experimental data | Using a method on a system it wasn't tested for. | Check the protocol's assumptions (e.g., number of chains, presence of ligands, membrane proteins) [33]. |

Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) Specific Errors

When running advanced protocols like QresFEP-2, specific issues can arise related to the alchemical transformations.

| Error / Issue | Probable Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Poor convergence of ΔΔG | Inadequate sampling or a suboptimal perturbation pathway. | Increase simulation time. For QresFEP-2, ensure dynamic restraint settings are appropriate for the mutation [30]. |

| Large outliers in charged mutations | Creation of an unpaired, buried charge, leading to high electrostatic penalty [34]. | Apply an empirical correction for unpaired buried charges or carefully scrutinize the protonation states of surrounding residues. |

| Inaccurate predictions for stabilizing mutations | Limitations in the force field or sampling, particularly for large conformational changes [31]. | Treat predictions for strongly stabilizing mutations with caution and use experimental validation. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Workflow for Combining Rosetta ddg with Alchemical FEP

This integrated workflow is effective for computationally efficient enzyme thermostability engineering, as demonstrated for DuraPETase [31].

Detailed Methodology:

- Generate Mutation Library: Create an in-silico library of single-point mutations focused on residues thought to influence stability.

- Rosetta ddg Monomer Screening: Run the

Rosetta ddg monomerapplication on the entire library. This step uses a master-slave protocol where a single "master" Rosetta process manages many "slave" processes, each of which performs a single mutation and calculates the associated ΔΔG [31].- Purpose: This fast, semi-empirical method enriches the library by filtering out clearly destabilizing mutations, significantly reducing the number of variants that require computationally expensive FEP [31].

- Candidate Selection: Select the top 50-100 mutations with the most negative (stabilizing) predicted ΔΔG values from the Rosetta screen.

- NEQ Alchemical FEP Calculations: Perform rigorous free energy calculations on the selected candidates.

- System Setup: Embed the protein in a water sphere under spherical boundary conditions.

- Transformation: Use a non-equilibrium (NEQ) alchemical FEP method to calculate the relative folding free energy. This involves performing "forward" (wild-type to mutant) and "reverse" (mutant to wild-type) non-equilibrium transitions. The data from these transitions is analyzed using the Crooks Fluctuation Theorem or the Jarzynski equality to obtain the free energy difference [31].

- Experimental Validation: Express and purify the top FEP-predicted stabilized variants. Measure the change in melting temperature (ΔTm) using Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF) to confirm computational predictions [31].

Protocol for Robust Protein-Protein Binding Affinity Prediction with FEP+

This protocol, benchmarked on systems like SARS-CoV-2 RBD binding to ACE2, ensures high accuracy for protein-protein interactions [34].

Detailed Methodology:

- System Preparation:

- Obtain an all-atom structural model from the PDB.

- Add hydrogen atoms and assign the dominant protonation states for all residues at the experimental pH.

- Critically, for any titratable residues (Asp, Glu, His, Lys) involved in a mutation, include alternate protonation states in the setup [34].

- Build Perturbation Map:

- Construct a network graph where nodes represent unique protein variants and edges represent FEP+ perturbations (mutations) between them.

- Ensure the map includes perturbations to and from all relevant alternate protonation states for titratable residues [34].

- Run FEP+ Simulations:

- Run simulations for a extended duration (e.g., 100 ns per edge) to ensure convergence.

- Post-process the simulation data to extract the relative binding free energy (ΔΔG) for each mutation [34].

- Analyze Outliers:

- Identify cases with large absolute errors (e.g., > 2.0 kcal/mol) compared to experimental data.

- Scrutinize these outliers, particularly for the creation of unpaired buried charges. An automated script can be used to detect such cases and apply a single-parameter empirical correction to improve accuracy [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key software and computational resources for running FEP and Rosetta calculations.

| Item | Function / Description | Relevance to Protein Stability |

|---|---|---|

| QresFEP-2 Software [30] | An open-source, hybrid-topology FEP protocol integrated with the Q molecular dynamics software. | Predicts ΔΔGfolding for point mutations with high accuracy and computational efficiency, ideal for protein engineering. |

| Rosetta Software Suite [31] [32] | A comprehensive modeling suite for macromolecular structures. Its ddg_monomer application predicts stability changes. |

Provides fast, initial stability predictions to triage large numbers of mutations before more expensive FEP calculations. |

| FEP+ (Schrödinger) [34] | A commercial, GPU-accelerated implementation of Free Energy Perturbation. | Used for high-accuracy prediction of changes in protein-protein binding affinity and protein thermostability. |

| GROMACS [31] | A molecular dynamics package. Used with pmx for free energy calculations. |

Facilitates NEQ alchemical free energy calculations for protein folding and binding. |

| Boltz-2 [35] | An open-source machine learning tool for predicting protein-ligand complex structure and binding affinity. | Complements FEP by providing faster affinity estimates once a binding pocket is identified. |

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers employing AI-driven de novo protein design, with a specific focus on strategies to prevent misfolding and aggregation, central challenges in developing functional proteins.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My de novo designed protein expresses poorly in a heterologous system. What could be the cause? Poor expression is often a symptom of marginal stability [36]. The protein's native state may not be significantly lower in energy than unfolded or misfolded states, leading to aggregation or degradation. This is common when natural proteins are moved from their native cellular environment, which contains chaperones, to a simplified heterologous system like E. coli [36].

Q2: Why do my designed proteins, which fold correctly in silico, form aggregates in vitro? This is frequently driven by supersaturation [37]. If the cellular concentration of your protein exceeds its intrinsic solubility (its critical concentration), the solution becomes supersaturated, creating a strong thermodynamic driving force for aggregation [37]. Even proteins with well-designed folds can aggregate if their expression levels are too high relative to their solubility. Check your protein's expression levels and consider down-regulating promoters.

Q3: What does "supersaturation" mean in the context of protein aggregation? Supersaturation is a thermodynamic state where the concentration of a protein in solution is higher than its innate solubility limit [37]. In this metastable state, the protein is strongly driven to aggregate, even if it remains soluble for a period due to kinetic barriers. Many proteins associated with neurodegenerative diseases, such as Aβ and α-synuclein, are naturally supersaturated, making them prone to aggregation when cellular quality control declines [37].

Q4: How can AI models help specifically with designing stable proteins? Modern AI strategies combine structure-based calculations with sequence-based guidance to implement both positive design (stabilizing the desired state) and negative design (destabilizing competing, misfolded states) [36]. For example, evolution-guided atomistic design uses the natural diversity of protein sequences to filter out mutations that are rare and potentially destabilizing, then uses atomistic calculations to find stabilizing mutations within this evolutionarily validated space [36].

Q5: What are the most common structural limitations in current de novo design? The field has historically been, and to a large extent remains, limited to designing proteins with simple topologies, most notably α-helix bundles [36]. Designing complex protein structures and sophisticated enzymes, which often require intricate beta-sheets and mixed folds, is a significant and ongoing challenge for the field [36].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below outlines common experimental issues, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low protein yield | Marginal native-state stability; protein misfolding or degradation [36]. | Use stability-design software (e.g., PROSS [36]) to optimize the sequence for higher stability. |

| Protein aggregation | Supersaturated solution; hidden aggregation-prone motifs in the sequence [37]. | Lower expression levels; re-design sequence with tools that predict and reduce aggregation propensity [37]. |

| Loss of function | Over-stabilization altering functional conformational dynamics; inaccurate interface design. | Balance stability with flexibility; use specialized tools (e.g., DeepSCFold [38]) for binding interface design. |

| Failed in silico design | Over-reliance on a single design method; inadequate negative design. | Employ a consensus approach combining multiple AI tools (RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN [39] [40]). |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Stability Optimization of a Protein Sequence

This protocol uses the evolution-guided atomistic design strategy implemented by tools like PROSS [36].

- Input Wild-Type Sequence: Provide the amino acid sequence and, if available, the experimental or predicted 3D structure of your protein of interest.

- Generate Sequence Homologs: Use tools like HHblits [38] or Jackhammer [38] to build a multiple sequence alignment (MSA) from a diverse set of natural homologs.

- Evolutionary Filtering: The algorithm analyzes the MSA to identify a subset of evolutionarily acceptable amino acids at each position, effectively filtering out mutations that are likely to be destabilizing.

- Atomistic Design Calculation: Within this constrained sequence space, perform an atomistic energy calculation to identify mutations that lower the energy of the native state, thereby improving stability.

- Synthesize and Test: Select the top in silico designs for experimental synthesis and characterization of stability and function.

Protocol 2: AI-Driven De Novo Binder Design

This protocol outlines the general workflow for designing a protein binder from scratch [39].

- Define Target: Identify the target molecule (e.g., a virus, a cell surface receptor, a small molecule) and the desired binding epitope if known.

- Generate Scaffold (Hallucination/Diffusion): Use generative AI models like RFdiffusion [40] or Chroma [39] to create de novo protein scaffolds that are structurally complementary to the target. This can be done by conditioning the generation process on the target's structure.

- Sequence Design: Input the generated backbone structure into a protein language model like ProteinMPNN [40] to design a primary amino acid sequence that will fold into that structure.

- In Silico Validation: Use high-accuracy structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2/3 [41] or RoseTTAFold All-Atom [41] to predict the structure of the designed protein both alone and in complex with the target. Assess the quality of the binding interface.

- Iterative Re-design: Based on the prediction, refine the design by repeating steps 2-4 until a promising candidate is generated.

- Experimental Characterization: Produce the designed protein and test its binding affinity and specificity using methods like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or ELISA.

The following diagram illustrates the core iterative cycle of AI-driven design and experimental testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit

The table below lists key computational tools and reagents essential for AI-driven de novo protein design.

| Tool / Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Generative AI model for creating novel protein scaffolds and binders from scratch [40]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Neural network for designing amino acid sequences that fold into a given protein backbone structure [40]. |

| AlphaFold2/3 | Highly accurate structure prediction tools for validating designs and predicting complex structures [41]. |

| RoseTTAFold All-Atom | A tool for modeling complexes containing proteins, nucleic acids, and small molecules [41]. |

| PROSS | A web server for stability optimization of existing proteins using evolution-guided design [36]. |

| DeepSCFold | A specialized pipeline for high-accuracy prediction of protein complex structures, useful for binder design [38]. |

| Chaperones (e.g., GroEL/ES) | Co-expression chaperones can assist with the folding of challenging proteins in heterologous systems [36]. |

| Stability Buffers | Buffers with varying pH, salt, and osmolyte conditions for empirically testing protein stability and solubility. |

Technical Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting TTR Aggregation Kinetics Experiments

Problem: High background noise in Thioflavin T (ThT) fluorescence assays

Potential Cause 1: Spectral interference from compound being tested

- Solution: Include control measurements with the compound alone to check for intrinsic fluorescence. Consider using Congo Red binding assays as a complementary method [42].

Potential Cause 2: Protein aggregation in storage

- Solution: Ensure protein samples are properly stored at -80°C and avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles. Centrifuge protein samples before use to remove pre-formed aggregates [43].

Potential Cause 3: Insufficient washing in filter-based assays

- Solution: Increase number of wash steps or optimize wash buffer composition to reduce non-specific binding [43].

Problem: Inconsistent TTR tetramer dissociation rates

Potential Cause 1: Variations in buffer conditions

- Solution: Precisely control pH (stability decreases as pH drops from 7.4 towards 5.0) and ensure consistent ionic strength across experiments [44].

Potential Cause 2: Insufficient characterization of TTR variants

- Solution: Fully sequence and verify all TTR variants. Over 150 TTR gene variants have been identified with varying penetrance and tissue tropism [44].

Potential Cause 3: Protein degradation during purification

- Solution: Perform all purification steps at 4°C, use protease inhibitors, and confirm protein integrity by mass spectrometry after purification [43].

Troubleshooting Cellular Models of TTR Aggregation

Problem: Low transfection efficiency in neuronal cell models

- Potential Cause: TTR aggregation causing cellular toxicity

- Solution: Use inducible expression systems to control expression timing and duration. Consider titrating down expression levels to reduce acute toxicity [45].

Problem: Inconsistent aggregate formation in cellular models

Potential Cause 1: Overwhelmed protein quality control systems

- Solution: Monitor chaperone expression (HSP70, HSP90) and proteasome activity. Consider temporary inhibition of proteasome to allow aggregate accumulation [45].

Potential Cause 2: Variable cellular stress responses

- Solution: Standardize culture conditions and measure ER stress markers to account for UPR activation in experiments [45].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)