De Novo Enzyme Design: Engineering Novel Biocatalysts from Scratch for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of de novo enzyme design, a discipline that creates novel protein catalysts with functions not found in nature.

De Novo Enzyme Design: Engineering Novel Biocatalysts from Scratch for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly advancing field of de novo enzyme design, a discipline that creates novel protein catalysts with functions not found in nature. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational principles driving the need for artificial enzymes, from overcoming the limitations of natural biocatalysts to enabling abiotic reactions like olefin metathesis in living systems. The content delves into the integrated methodological toolkit, combining computational design, artificial intelligence, and directed evolution. It further addresses critical challenges in optimization and troubleshooting, and concludes with a rigorous examination of validation frameworks and comparative analyses of current technologies, highlighting their profound implications for therapeutic development and green chemistry.

Beyond Nature's Blueprint: The Rationale and Core Principles of Designing Enzymes from Scratch

The Catalytic Limitations of Natural Enzymes and the Case for De Novo Design

Natural enzymes, often described as "nature's privileged catalysts," are renowned for their exceptional selectivity and efficiency in accelerating biochemical reactions under mild physiological conditions [1] [2]. These protein catalysts drive virtually all essential biological processes, from cell growth and development to complex material synthesis in living organisms [2]. However, despite their evolutionary optimization for specific biological functions, natural enzymes possess inherent limitations that restrict their utility in industrial, pharmaceutical, and research contexts. These constraints include narrow substrate specificity, instability under non-physiological conditions, and an inability to catalyze "new-to-nature" reactions not found in biological systems [1] [3].

The field of enzyme engineering has emerged to overcome these limitations, with de novo enzyme design representing a paradigm shift from modifying existing enzymes to creating entirely new catalytic proteins from first principles [3]. This approach uses computational and artificial intelligence (AI) methodologies to design novel enzyme sequences and structures tailored for specific applications, bypassing the constraints of natural enzyme evolution [4] [3]. By moving beyond the limitations of natural enzyme scaffolds, de novo design promises to unlock new possibilities in sustainable chemistry, drug development, and biotechnology through the creation of biocatalysts with customized functions, enhanced stability, and novel catalytic mechanisms [1] [2] [3].

Fundamental Limitations of Natural Enzyme Catalysis

Restricted Reaction Scope and Functional Limitations

Natural enzymes have evolved to catalyze a specific set of biochemical reactions essential for life processes, creating significant gaps in their catalytic repertoire for synthetic chemistry applications. This limitation becomes particularly evident in several key areas:

- Lack of efficient natural enzymes for synthetically valuable bond-forming reactions, including carbon-carbon and carbon-silicon bond formation, which are fundamental to pharmaceutical and materials synthesis [1]

- Inability to catalyze abiotic reactions not found in nature, such as the Kemp elimination, Diels-Alder cycloadditions, or olefin metathesis, despite the potential utility of these transformations in synthetic chemistry [5] [6]

- Limited capacity for industrial substrate processing, as natural enzymes typically recognize only specific biological molecules under narrow environmental conditions [1]

Operational Instability Under Non-Physiological Conditions

Natural enzymes function within precise physiological environments, but industrial and pharmaceutical applications often require stability under drastically different conditions:

- Narrow functional ranges for parameters such as temperature, pH, and ionic strength, outside of which enzymatic activity rapidly declines [1] [7]

- Susceptibility to organic solvents used in industrial processes, with most natural enzymes denaturing in solvent concentrations above 10-20% [1]

- Thermolability at elevated temperatures used in industrial processes to increase reaction rates and reduce microbial contamination [8]

- Proteolytic degradation in therapeutic applications, limiting their half-life and efficacy in biological systems [8]

Structural Inefficiencies and Delivery Challenges

The complex architecture of natural enzymes presents practical challenges for various applications:

- Large size and structural redundancy, where much of the protein scaffold may contribute minimally to catalytic function while increasing metabolic costs of synthesis and folding [8]

- Delivery limitations in therapeutic applications, where large enzymes like CRISPR-Cas systems face challenges in efficient delivery to target tissues and cells due to vector payload constraints [8]

- Reduced electron transfer rates in biosensing applications, where increased cofactor-electrode distances in large oxidoreductases compromise detection sensitivity [8]

Table 1: Key Limitations of Natural Enzymes in Industrial and Therapeutic Applications

| Limitation Category | Specific Constraints | Impact on Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Scope | Limited to biological reactions; Cannot catalyze abiotic transformations | Restricts use in synthetic chemistry and new reaction development |

| Environmental Sensitivity | Narrow pH and temperature ranges; Organic solvent intolerance | Limits process conditions in manufacturing; Requires costly stabilization |

| Structural Issues | Large size with redundant elements; Flexible loops and disordered regions | Challenges in therapeutic delivery; Reduced thermal stability; Folding inefficiencies |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Optimized for physiological substrates; Product inhibition issues | Poor performance with non-natural substrates; Low productivity in industrial processes |

The Emergence of De Novo Enzyme Design

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

De novo enzyme design represents a computational approach to creating novel protein sequences and structures from first principles or learned models, rather than modifying existing natural enzymes [3]. This methodology stands in contrast to traditional enzyme engineering approaches such as rational design (targeted mutations based on structure) and directed evolution (iterative rounds of mutation and selection) [2] [3]. The core premise of de novo design is the ability to access entirely novel regions of sequence-structure space, unconstrained by the evolutionary history of natural enzymes [3].

This approach typically begins with a theozyme (theoretical enzyme) - a computational model of the ideal catalytic constellation for a target reaction, often derived from quantum-mechanical calculations of the transition state [4] [6]. Design methods then identify or generate protein scaffolds capable of positioning amino acid side chains to precisely stabilize this transition state, creating an environment optimal for catalysis [6]. The designs are subsequently refined using physics-based energy functions and, increasingly, artificial intelligence methods to ensure stable folding and catalytic competence [4] [3].

Comparative Analysis: Traditional Engineering vs. De Novo Approaches

Table 2: Comparison of Enzyme Engineering Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Principles | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rational Design | Structure-based mutagenesis of natural enzymes; Focus on active site engineering | High precision; Minimal mutations required; Clear structure-function relationships | Limited by natural scaffold constraints; Requires extensive structural knowledge |

| Directed Evolution | Iterative rounds of random mutagenesis and screening/selection for desired traits | No structural knowledge needed; Can discover unexpected solutions; Proven industrial track record | Labor-intensive; Limited exploration of sequence space; Local optimization |

| De Novo Design | Computational creation from first principles; Transition state stabilization in novel scaffolds | Access to novel folds and functions; Not limited by natural enzyme repertoire; Global sequence space exploration | Computational complexity; Challenges in predicting folding and function; Often requires experimental refinement |

Methodological Framework for De Novo Enzyme Design

Computational Workflows and Design Strategies

The de novo design process follows structured computational workflows that integrate multiple methodologies to create functional enzymes. Recent advances have demonstrated complete computational workflows that generate efficient enzymes without requiring extensive experimental optimization [6]. The core strategies include:

- Structure-based design: Utilizes physical energy functions and spatial pattern algorithms to derive stable conformations from 3D structural constraints, often employing frameworks like helical bundle proteins or TIM-barrel folds [3] [6]

- Sequence-based design: Employs deep generative models trained on natural protein sequences to learn co-evolutionary patterns and generate functional sequences from data-driven principles [3]

- Fragment-based backbone generation: Combines structural fragments from natural proteins to create novel backbones with diverse active-site geometries [6]

- Inside-out design: Models the catalytic transition state first, then builds the supporting protein scaffold around this functional core [4]

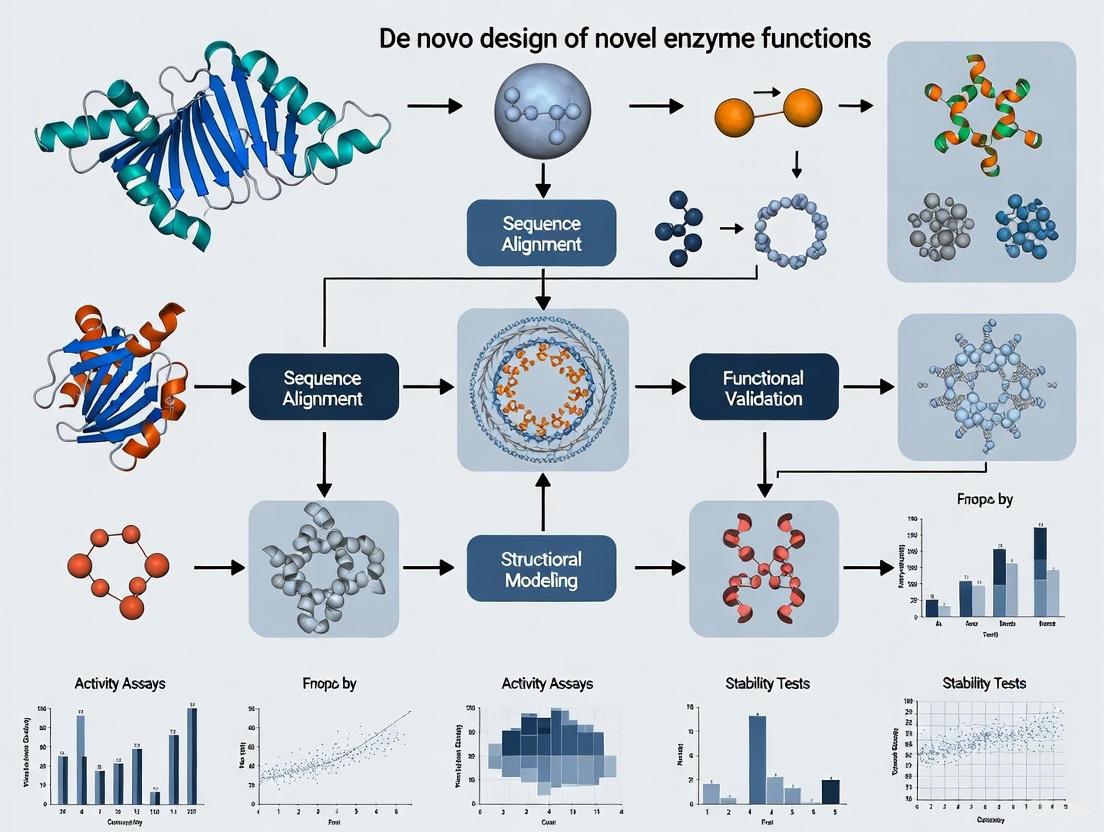

The following diagram illustrates a representative workflow for computational de novo enzyme design:

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

De Novo Design of Kemp Eliminases

The Kemp elimination reaction serves as a benchmark for de novo enzyme design, as no natural enzyme is known to catalyze this proton transfer from carbon [6]. A recently published protocol demonstrates a fully computational workflow for designing high-efficiency Kemp eliminases:

Theozyme Construction: Quantum mechanical calculations define the ideal catalytic constellation, including a carboxylate base (Asp/Glu) for proton abstraction and aromatic residues for π-stacking with the substrate transition state [6]

Backbone Generation: Thousands of TIM-barfold backbones are generated using combinatorial assembly of fragments from natural proteins (e.g., indole-3-glycerol-phosphate synthase family) to create structural diversity in active site regions [6]

Transition State Placement: Geometric matching algorithms position the KE theozyme in each generated backbone, identifying scaffolds with optimal preorganization for catalysis [6]

Active Site Optimization: Rosetta atomistic calculations mutate all active-site positions to optimize interactions with the transition state while maintaining low energy states [6]

Filtering and Selection: A "fuzzy-logic" optimization objective function balances conflicting design criteria (catalytic geometry, desolvation of catalytic base, and overall protein stability) to select top designs [6]

Stability Enhancement: Comprehensive stabilization of the active site and protein core through sequence optimization, often resulting in designs with >100 mutations from any natural protein [6]

This protocol has yielded Kemp eliminases with catalytic efficiencies of 12,700 M⁻¹s⁻¹ and rates of 2.8 s⁻¹, surpassing previous computational designs by two orders of magnitude and approaching the efficiency of natural enzymes [6].

Artificial Metathase Design for Olefin Metathesis

Olefin metathesis represents a powerful carbon-carbon bond formation reaction with no natural enzyme equivalent. The design protocol for artificial metathases involves:

Cofactor Design: Engineering a Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst derivative (Ru1) with polar sulfamide groups to enable supramolecular interactions with the protein scaffold and improve aqueous solubility [5]

Scaffold Selection: Using de novo-designed closed alpha-helical toroidal repeat proteins (dnTRP) as hyperstable scaffolds with engineerable binding pockets [5]

Computational Docking: Using RifGen/RifDock suites to enumerate amino acid rotamers around the cofactor and dock the ligand with interacting residues into protein cavities [5]

Binding Affinity Optimization: Iterative design of hydrophobic contacts (e.g., Phe→Trp mutations at positions F43 and F116) to enhance cofactor binding (KD ≤ 0.2 μM) through supramolecular anchoring [5]

Directed Evolution: Engineering catalytic performance through screening in E. coli cell-free extracts at optimized pH (4.2) with glutathione oxidation using Cu(Gly)₂ [5]

This approach has produced artificial metathases with turnover numbers ≥1,000 for ring-closing metathesis in cytoplasmic environments, demonstrating pronounced biocompatibility and catalytic efficiency [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for De Novo Enzyme Design

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Design Suites | Rosetta Macromolecular Modeling Suite; RifGen/RifDock | Protein structure prediction, design, and ligand docking; Energy-based scoring and optimization |

| AI/ML Platforms | ProteinMPNN; AlphaFold 2/3; ESMFold; Generative Language Models | Protein sequence design; Structure prediction from sequence; Generation of novel protein sequences |

| Expression Systems | E. coli BL21(DE3); Pichia pastoris; Cell-free expression systems | Heterologous protein expression; Rapid screening of design variants |

| Characterization Methods | X-ray crystallography; Native mass spectrometry; Tryptophan fluorescence quenching | Structural validation; Binding affinity measurements (KD); Complex stoichiometry determination |

| Activity Assays | UV-Vis spectroscopy (Kemp elimination); GC-MS (metathesis products); HPLC analysis | Kinetic parameter determination (kcat, KM); Reaction monitoring and product identification |

| Stability Assessment | Differential scanning calorimetry; Circular dichroism; Thermal shift assays | Melting temperature (Tm) determination; Secondary structure analysis; Stability profiling |

Case Studies and Experimental Validation

Breakthrough Designs and Catalytic Performance

Recent advances in de novo enzyme design have yielded several breakthrough catalysts that demonstrate the field's rapid progress:

High-Efficiency Kemp Eliminases: A fully computational design workflow has produced Kemp eliminases with remarkable catalytic parameters, including kcat/KM = 12,700 M⁻¹s⁻¹ and kcat = 2.8 s⁻¹ [6]. These designs featured more than 140 mutations from any natural protein and exhibited exceptional thermal stability (>85°C). Further optimization through computational active-site redesign achieved catalytic efficiencies exceeding 10⁵ M⁻¹s⁻¹ with turnover rates of 30 s⁻¹, matching the performance of natural enzymes and challenging fundamental assumptions about biocatalytic design limitations [6].

Artificial Metathases for Whole-Cell Biocatalysis: De novo-designed artificial metalloenzymes incorporating synthetic ruthenium cofactors have enabled olefin metathesis—a reaction with no natural biological counterpart—within living E. coli cells [5]. These designs combined tailored Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst derivatives with hyperstable de novo protein scaffolds, achieving turnover numbers ≥1,000 for ring-closing metathesis of olefins in cytoplasmic environments. The integration of computational design with directed evolution resulted in variants with excellent catalytic performance and pronounced biocompatibility [5].

Carbon-Silicon Bond Formation: Researchers have developed a workflow converting simple miniature helical bundle proteins into efficient and selective enzymes for forming carbon-silicon bonds, addressing a significant gap in natural enzymatic capabilities [1]. This approach combined de novo protein design with state-of-the-art artificial intelligence methods to create sequences that support non-biological transformations, demonstrating the potential for creating enzymes that operate via mechanisms not previously known in nature [1].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Table 4: Catalytic Performance of Representative De Novo Designed Enzymes

| Enzyme Design | Reaction Type | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Turnover Number (kcat) | Thermal Stability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kemp Eliminase Des27 [6] | Proton transfer | 12,700 M⁻¹s⁻¹ | 2.8 s⁻¹ | >85°C |

| Optimized Kemp Eliminase [6] | Proton transfer | >100,000 M⁻¹s⁻¹ | 30 s⁻¹ | >85°C |

| Artificial Metathase dnTRP_18 [5] | Olefin metathesis | N/R | ≥1,000 | T₅₀ >98°C |

| Previous KE Designs [6] | Proton transfer | 1-420 M⁻¹s⁻¹ | 0.006-0.7 s⁻¹ | Variable |

| Natural Enzymes (median) [6] | Various | ~100,000 M⁻¹s⁻¹ | ~10 s⁻¹ | Variable |

N/R: Not reported in the source material

Advantages and Applications of De Novo Designed Enzymes

Functional and Operational Benefits

De novo designed enzymes offer significant advantages over both natural enzymes and traditional engineered variants:

- Expanded reaction scope: Capacity to catalyze non-biological transformations including carbon-silicon bond formation, olefin metathesis, and Kemp elimination [1] [5] [6]

- Enhanced stability characteristics: Hyperstable designs with T₅₀ >98°C and tolerance to extreme pH conditions (2.6-8.0), far exceeding typical natural enzyme stability ranges [5]

- Organic solvent compatibility: Function in up to 60% organic solvent concentrations, enabling chemistry in environments incompatible with natural enzymes [1]

- Customizable cofactor utilization: Ability to incorporate non-biological cofactors and metal complexes for abiotic catalysis [1] [5]

- Size optimization: Miniature enzyme designs with improved folding efficiency, expressibility, thermostability, and resistance to proteolysis [8]

Industrial and Therapeutic Applications

The unique properties of de novo designed enzymes open new possibilities across multiple domains:

Pharmaceutical Manufacturing:

- Synthesis of complex active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) through biocatalytic routes with improved selectivity and reduced environmental impact [9]

- Enzyme-based therapies for genetic disorders (e.g., acute lymphoblastic leukemia with asparaginase) through engineered specificity and reduced immunogenicity [9]

- Targeted cancer treatments using enzymes designed to selectively activate prodrugs within tumor environments [10] [9]

Sustainable Chemistry:

- Biocatalysts for green chemistry applications operating in water as the "greenest solvent" with reduced energy requirements [1]

- Degradation of environmental pollutants through enzymes with tailored activities for emerging contaminants [2]

- Biosensing platforms with miniature enzymes exhibiting enhanced electron transfer rates for improved detection sensitivity [8]

Advanced Materials and Synthesis:

- Custom catalysts for polymer synthesis and materials design through controlled bond-forming reactions [1]

- Industrial biocatalysis under demanding process conditions incompatible with natural enzymes [3] [8]

Future Directions and Concluding Perspectives

Emerging Trends and Methodological Advances

The field of de novo enzyme design is rapidly evolving, driven by several converging technological developments:

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: Machine learning models, particularly deep generative networks and protein language models, are revolutionizing sequence-structure-function predictions, enabling more accurate design of functional proteins [4] [2] [3]

- Automated Design Workflows: Movement toward general, automated protein design systems that unify sequence generation, structure prediction, and fitness optimization in integrated frameworks [2]

- High-Throughput Characterization: Development of rapid experimental validation methods to generate labeled training data for AI models, creating virtuous cycles of design improvement [2]

- Miniaturization Strategies: Increased focus on designing compact enzymes with improved folding kinetics, stability, and delivery characteristics for therapeutic and diagnostic applications [8]

De novo enzyme design represents a fundamental shift in our approach to creating biological catalysts, moving beyond the constraints of natural enzyme evolution to rationally design proteins with tailored functions. While natural enzymes will continue to serve important roles in biocatalysis, their inherent limitations in reaction scope, stability, and customizability create compelling opportunities for designed alternatives.

The recent success in creating highly efficient enzymes through completely computational workflows [6], combined with the ability to catalyze abiotic reactions in biological environments [5], demonstrates that de novo design has transitioned from theoretical possibility to practical capability. As AI methodologies continue to advance and our understanding of protein folding and catalysis deepens, we can anticipate increasingly sophisticated designs that further blur the distinction between natural and artificial enzymes.

For researchers and drug development professionals, these developments offer unprecedented opportunities to create custom biocatalytic solutions for specific challenges, from sustainable chemical synthesis to targeted therapeutic interventions. The coming years will likely see de novo designed enzymes moving from laboratory demonstrations to broad industrial and clinical application, ultimately fulfilling the promise of tailor-made catalysts designed from first principles.

Defining Artificial Metalloenzymes (ArMs) and New-to-Nature Reactions

Artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs) represent a pioneering class of designer biocatalysts that combine the versatile reactivity of synthetic metallocatalysts with the precise selectivity of protein scaffolds. These hybrid catalysts are not found in nature and are engineered to catalyze both natural reactions with enhanced selectivity and new-to-nature reactions—chemical transformations without precedent in biological systems [11]. The fundamental architecture of an ArM consists of two primary components: a genetically engineerable protein scaffold that provides a defined second coordination sphere, and an artificial catalytic moiety featuring a synthetic metal center that enables novel reactivity [11] [12].

The significance of ArMs extends across multiple disciplines, from synthetic chemistry to pharmaceutical development. They effectively bridge the gap between homogeneous catalysis and enzymatic catalysis, offering the potential to perform reactions in water under mild conditions while maintaining the high activity and broad reaction scope typical of organometallic catalysts [12]. This unique combination addresses longstanding challenges in synthetic chemistry, including the catalytic asymmetric synthesis of complex molecules and the implementation of sustainable chemical processes.

Structural Composition and Assembly Strategies

Fundamental Components

The performance of ArMs derives from the synergistic interaction between their constituent parts. The metal cofactor provides the primary catalytic activity, often enabling reaction mechanisms inaccessible to purely biological systems. These cofactors can range from simple metal ions to sophisticated organometallic complexes. The protein scaffold serves multiple critical functions: it creates a chiral environment to enforce enantioselectivity, enhances catalyst stability through encapsulation, and provides a platform for iterative optimization through protein engineering [11].

The development of ArMs has been accelerated through chemogenetic optimization, a parallel improvement strategy that simultaneously refines both the direct metal surroundings (first coordination sphere) and the protein environment (second coordination sphere) [11]. This approach allows researchers to fine-tune catalytic properties through a combination of synthetic chemistry and molecular biology techniques.

ArM Construction Methodologies

Four principal strategies have been established for assembling functional ArMs, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications:

Table 1: Primary Strategies for Artificial Metalloenzyme Assembly

| Assembly Strategy | Mechanism | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Anchoring | Irreversible chemical bonding between metal complex and protein side chains | Stable conjugation; precise positioning | Cysteine-based linkages; post-translational modifications [11] |

| Supramolecular Anchoring | High-affinity non-covalent interactions | Modular assembly; facile screening | Biotin-streptavidin systems; antibody-antigen recognition [11] [12] |

| Metal Substitution | Replacement of native metal in natural metalloenzyme | Altered electronic/steric properties | Novel catalytic pathways in repurposed natural enzymes [11] [13] |

| Dative Anchoring | Direct coordination of metal by protein amino acid residues | Simple implementation; minimal synthetic modification | Natural amino acid coordination (His, Cys, Glu, Asp) [11] |

A fifth emerging strategy involves the genetic incorporation of metal-chelating unnatural amino acids, which enables precise positioning of metal coordination sites directly within the protein backbone through amber stop codon suppression techniques [11]. This approach provides atomic-level control over the first coordination sphere while maintaining the evolvability of the protein scaffold.

The New-to-Nature Reaction Paradigm

Conceptual Framework

New-to-nature reactions represent chemical transformations that expand beyond the known repertoire of biological catalysis. These reactions leverage reaction mechanisms and catalytic approaches that have not evolved in natural biological systems, effectively creating synthetic metabolic pathways and enabling the production of non-biological compounds [14]. The pursuit of these reactions represents a fundamental shift in biocatalysis, from exploiting nature's existing toolkit to creating entirely new biocatalytic functions.

This paradigm has been particularly powerful in addressing synthetic challenges in pharmaceutical and fine chemical synthesis. For example, the development of an artificial Suzukiase based on biotin-streptavidin technology enables enantioselective Suzuki coupling reactions, a transformation previously restricted to synthetic catalysts [11]. Similarly, ArMs have been engineered to perform olefin metathesis, C-H activation, and cyclopropanation reactions with biological compatibility [11].

Representative Reaction Classes

The reaction scope facilitated by ArMs has expanded dramatically in recent years, encompassing numerous valuable transformations:

Table 2: Categories of New-to-Nature Reactions Catalyzed by Artificial Metalloenzymes

| Reaction Category | Specific Examples | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| Cross-Coupling Reactions | Suzuki reaction [11], Heck reaction [11] | C-C bond formation for pharmaceutical synthesis |

| Carbene/Nitrene Transfer | Cyclopropanation [11], C-H amination [14] | Introduction of stereocenters and strained rings |

| Radical Chemistry | Atom transfer radical cyclization [11], Giese-type radical conjugate addition [15] | Access to challenging radical intermediates under mild conditions |

| Oxidation & Reduction | Asymmetric hydrogenation [11], alcohol oxidation [11] | Selective redox transformations without heavy metal contaminants |

| Multi-Step Cascades | Chemoenzymatic cascades [12] | Streamlined synthesis without intermediate isolation |

The mechanism behind many new-to-nature reactions often involves the generation of highly reactive intermediates, such as metal-carbene or metal-nitrene species, which are subsequently harnessed within the protein scaffold to achieve stereoselective transformations [14]. For instance, engineered cytochrome P450 enzymes can be repurposed to perform abiological carbene transfer reactions that proceed through reactive iron-carbene intermediates, enabling cyclopropanation and other valuable transformations [14].

Experimental Design and Optimization Workflows

Integrated Development Pipeline

The creation of functional ArMs follows an iterative development process that integrates design, assembly, and optimization phases. The workflow typically begins with scaffold selection, where researchers choose appropriate protein frameworks based on structural properties, engineering feasibility, and compatibility with the target reaction. Common scaffolds include streptavidin, multidrug resistance regulators (LmrR), and various β-barrel proteins [11].

Diagram 1: ArM Development Workflow

Following initial assembly, ArMs undergo systematic optimization through directed evolution, a powerful protein engineering approach that mimics natural evolution in laboratory settings. This process involves iterative cycles of mutagenesis and high-throughput screening to identify variants with enhanced activity, selectivity, or stability [14]. The 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Frances H. Arnold recognized the transformative potential of directed evolution for enzyme engineering, including the optimization of ArMs [11].

Key Methodological Approaches

Directed Evolution Protocol

Library Generation: Create genetic diversity through error-prone PCR or DNA shuffling of the gene encoding the protein scaffold [14].

Expression and Assembly: Express variant proteins in suitable host systems (typically E. coli) and reconstitute with the artificial metal cofactor [11].

High-Throughput Screening: Implement rapid assays to evaluate catalytic performance (activity, enantioselectivity) across thousands of variants [14].

Variant Selection: Identify improved clones and use them as templates for subsequent evolution rounds [14].

This methodology enabled the transformation of cytochrome P450 enzymes with trace C-H amination activity into efficient catalysts capable of hundreds to thousands of turnovers with high stereoselectivity [14].

Photobiocatalysis Development

Recent advances have integrated photoredox catalysis with ArM technology:

Cofactor Excitation: Utilize visible light to excite engineered ketoreductase enzymes, enabling radical generation from alkyl halide precursors [15].

Stereocontrol: Leverage the enzyme active site to control radical intermediate stereochemistry, enabling asymmetric transformations [15].

Reaction Optimization: Fine-tune reaction conditions (wavelength, temperature, substrate loading) to maximize yield and selectivity [15].

This approach has enabled challenging reactions such as asymmetric hydrogen atom transfer and hydroalkylation of styrenes, expanding the synthetic utility of flavin-dependent enzymes beyond their natural two-electron redox chemistry [14].

Research Reagents and Toolkits

Essential Research Materials

The development and application of ArMs relies on specialized reagents and tools that facilitate their construction, optimization, and implementation:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Artificial Metalloenzyme Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Scaffolds | Streptavidin variants [11], LmrR [11], Cytochrome P450 [14] | Provides evolvable chiral environment for metal cofactor |

| Metal Cofactors | Biotinylated piano-stool complexes [12], Fe(heme) complexes [11], Cu(phenanthroline) complexes [11] | Imparts novel catalytic activity and reaction mechanisms |

| Genetic Tools | Amber stop codon suppression systems [11], Metallo-CRISPR libraries [16] | Enables incorporation of unnatural amino acids and targeted mutagenesis |

| Analytical Methods | Computational docking tools [16], High-throughput screening assays [17] | Facilitates design and optimization through rapid performance evaluation |

| Specialized Libraries | Metal-binding pharmacophores (MBPs) [16], Fragment libraries [18] | Provides building blocks for inhibitor design and cofactor development |

The increasing integration of machine learning and computational design has dramatically accelerated ArM development:

RFdiffusion, a recently developed protein design tool, enables de novo generation of protein backbones tailored to accommodate specific functional motifs [19]. By fine-tuning the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network on protein structure denoising tasks, researchers can generate novel protein scaffolds optimized for metal cofactor incorporation and catalytic function [19].

Complementary tools like CATNIP (Compatibility Assessment Tool for Non-natural Intermediate Partnerships) help predict productive enzyme-substrate pairs for specific transformations, particularly for α-ketoglutarate/Fe(II)-dependent enzyme systems [17]. This predictive capability reduces the experimental burden associated with identifying starting points for enzyme engineering.

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Therapeutic Development

ArM technology has significant implications for pharmaceutical research and development. Blacksmith Medicines has leveraged metalloenzyme-targeting platforms to develop FG-2101, a novel non-hydroxamate antibiotic that inhibits LpxC—a zinc-dependent metalloenzyme found exclusively in Gram-negative bacteria [16] [18]. This approach addresses the historical challenges associated with targeting metalloenzymes, which represent over 30% of all known enzymes but have proven difficult to drug with conventional small molecules [18].

Sustainable Chemistry and Biomanufacturing

The application of ArMs in industrial biocatalysis offers opportunities for more sustainable manufacturing processes. By enabling efficient chemical synthesis in water under mild conditions, ArMs can reduce energy consumption and waste generation associated with traditional chemical catalysis [15]. Their compatibility with biological systems also facilitates the development of chemoenzymatic cascades, where artificial and natural enzymes work in concert to convert renewable feedstocks into valuable chemicals [12].

Recent advances in intracellular ArM catalysis have demonstrated the potential for implementing new-to-nature reactions within living cells, opening possibilities for synthetic biology and metabolic engineering applications [11] [12]. This capability could enable the microbial production of complex molecules through artificial biosynthetic pathways that incorporate non-biological reaction steps.

Knowledge Gaps and Research Challenges

Despite significant progress, several challenges remain in the field of artificial metalloenzymes. The predictable integration of non-biological cofactors into protein scaffolds continues to require substantial optimization, and the general rules governing second-sphere interactions in ArMs are not fully understood [13]. Additionally, the scalability of ArM-catalyzed processes for industrial applications needs further demonstration, particularly for complex multi-step transformations.

Future research directions will likely focus on expanding the reaction scope of ArMs, improving computational design accuracy, and developing more efficient strategies for optimizing ArM performance. The integration of machine learning approaches with high-throughput experimental validation represents a particularly promising avenue for accelerating the development cycle [14] [19]. As these tools mature, artificial metalloenzymes are poised to become increasingly powerful catalysts for solving challenging problems in synthetic chemistry and biotechnology.

The de novo design of novel enzyme functions represents a frontier in synthetic biology, aiming to create tailored biocatalysts that operate with high efficiency in demanding industrial and therapeutic environments. The success of these designed enzymes hinges on achieving three critical design objectives: thermostability, solvent tolerance, and cofactor compatibility. Thermostability ensures enzymatic integrity and function at elevated temperatures, accelerating reaction rates and preventing aggregation. Solvent tolerance enables functionality in non-aqueous environments essential for industrial biocatalysis where substrate solubility is limited. Cofactor compatibility expands catalytic repertoire by incorporating synthetic metal complexes and abiotic cofactors to catalyze "new-to-nature" reactions. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and computational frameworks for achieving these design objectives, providing researchers with actionable strategies for advancing de novo enzyme design.

Thermostability: Engineering Robust Molecular Scaffolds

Fundamental Principles and Molecular Strategies

Thermostability is crucial for industrial enzyme applications, directly influencing catalytic efficiency, half-life, and operational costs. Enhancing an enzyme's ability to maintain its native conformation under elevated temperatures involves strategic reinforcement of its structural framework through multiple molecular mechanisms [20].

Short-loop engineering has emerged as a powerful strategy for enhancing thermal stability by targeting rigid "sensitive residues" in short-loop regions. This approach involves mutating these residues to hydrophobic amino acids with large side chains to fill internal cavities, thereby enhancing structural integrity [20]. Unlike traditional B-factor strategies that target flexible regions, short-loop engineering focuses on stabilizing inherently rigid areas that may contain destabilizing cavities. The strategy proved effective across multiple enzyme classes, increasing the half-life of lactate dehydrogenase from Pediococcus pentosaceus by 9.5-fold, urate oxidase from Aspergillus flavus by 3.11-fold, and D-lactate dehydrogenase from Klebsiella pneumoniae by 1.43-fold compared to wild-type enzymes [20].

Hydrophobic core packing represents another crucial mechanism, where clustering hydrophobic residues in the protein core minimizes structural voids and enhances stability. Thermophilic proteins naturally employ this strategy, exhibiting a higher proportion of hydrophobic and charged residues that create a densely packed interior [20]. Computational analyses reveal that cavity-filling mutations can reduce void volumes from 265 ų to less than 48 ų, significantly improving structural rigidity without introducing new hydrogen bonds or salt bridges [20].

Secondary stabilization through hydrogen bonding, salt bridges, and disulfide bonds provides additional stabilization. While not the primary focus of cavity-filling strategies, these elements contribute significantly to overall structural integrity, particularly when strategically positioned to restrict structural "wobble" at high temperatures [20].

Experimental Protocols and Assessment Methods

Virtual Saturation Mutagenesis with Free Energy Calculations: This protocol identifies stabilization sites through computational screening:

- Step 1: Identify short-loop regions (typically 3-8 residues) connecting secondary structural elements

- Step 2: Perform virtual saturation mutagenesis using tools like FoldX to calculate unfolding free energy changes (ΔΔG)

- Step 3: Identify "sensitive residues" where mutations yield negative ΔΔG values, indicating stabilization potential

- Step 4: Prioritize residues with small side chains (e.g., alanine) creating cavities for mutation to larger hydrophobic residues (phenylalanine, tyrosine, tryptophan, methionine)

Experimental Validation Pipeline:

- Library Construction: Generate saturation mutagenesis libraries for identified sensitive residues

- Expression Screening: Express variants and assess solubility and folding

- Thermal Stability Assays:

- Determine half-life (t₁/₂) at elevated temperatures

- Measure melting temperature (Tₘ) using differential scanning fluorimetry

- Calculate residual activity after incubation at target temperatures

- Structural Analysis:

- Perform molecular dynamics simulations to assess root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF)

- Analyze cavity volumes pre- and post-mutation

- Identify formation of new stabilizing interactions

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements in Enzyme Thermostability via Short-Loop Engineering

| Enzyme | Source Organism | Mutation | Half-life Improvement (Fold) | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate Dehydrogenase | Pediococcus pentosaceus | A99Y | 9.5 | Cavity filling, enhanced hydrophobic interactions |

| Urate Oxidase | Aspergillus flavus | Not specified | 3.11 | Cavity filling, structural compaction |

| D-Lactate Dehydrogenase | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Not specified | 1.43 | Cavity filling, hydrophobic clustering |

Solvent Tolerance: Designing for Non-Aqueous Environments

Molecular Adaptations for Organic Solvents

Industrial biocatalysis often requires operation in non-aqueous environments where organic solvents are necessary for substrate solubility or product recovery. Solvent tolerance encompasses an enzyme's ability to maintain structural integrity and catalytic activity in the presence of organic solvents, which typically strip essential water molecules, disrupt hydrogen bonds, and cause structural denaturation.

Surface charge engineering enhances solvent tolerance by optimizing surface charge distribution to maintain hydration layers in organic solvents. Introducing charged residues (glutamate, aspartate, lysine, arginine) on the protein surface strengthens protein-solvent interactions and prevents aggregation in low-dielectric environments [21]. Rational design of surface charges can be guided by computational tools that model protein-solvent interactions and identify regions prone to destabilization.

Surface hydrophobization represents a counterintuitive yet effective strategy where increasing surface hydrophobicity improves compatibility with organic solvents. This approach reduces the energetic penalty of transferring the enzyme from aqueous to organic environments and prevents unfavorable interactions at the protein-solvent interface [21]. Strategic mutation of polar surface residues to hydrophobic ones (leucine, valine, isoleucine) can significantly enhance stability in organic media.

Structural rigidification through the introduction of disulfide bonds and proline residues reduces conformational flexibility, minimizing unfolding in dehydrating environments. Computational tools like RosettaDesign can identify potential disulfide bond formation sites that stabilize the native state without compromising catalytic function [19].

Experimental Assessment of Solvent Tolerance

Solvent Stability Assays:

- Incubation Protocol: Incubate enzymes in water-solvent mixtures (e.g., 25% DMSO, 30% methanol, 20% acetonitrile) for predetermined durations

- Activity Measurements: Assess residual activity using standard enzymatic assays compared to aqueous controls

- Structural Integrity:

- Circular dichroism spectroscopy to monitor secondary structural changes

- Fluorescence spectroscopy to analyze tertiary structural alterations

- Dynamic light scattering to detect aggregation

Solvent Tolerance Screening Pipeline:

- Primary Screening: High-throughput assessment of activity in microtiter plates with various solvent conditions

- Secondary Validation: Detailed kinetic analysis (Kₘ, kcat) in optimal solvent systems

- Tertiary Characterization: Long-term stability studies under operational conditions

Table 2: Strategic Approaches for Enhancing Enzyme Solvent Tolerance

| Strategy | Molecular Approach | Experimental Implementation | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface Charge Engineering | Introduce charged residues at solvent-exposed positions | Computational surface analysis followed site-directed mutagenesis | Improved hydration layer maintenance in polar solvents |

| Surface Hydrophobization | Replace polar surface residues with hydrophobic counterparts | Saturation mutagenesis of surface residues followed by solvent screening | Enhanced stability in non-polar organic solvents |

| Structural Rigidification | Introduce disulfide bonds or proline residues at flexible loops | Computational design of stabilizing disulfides with geometric constraints | Reduced conformational flexibility and unfolding in dehydrating environments |

Cofactor Compatibility: Expanding Catalytic Repertoire

Designing Artificial Metalloenzymes

Cofactor compatibility addresses the challenge of incorporating synthetic metal complexes and abiotic cofactors into protein scaffolds to catalyze non-biological reactions. This objective represents the cutting edge of de novo enzyme design, enabling chemical transformations beyond nature's repertoire [5].

The de novo design of artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs) requires creating tailored protein scaffolds that can bind synthetic cofactors while providing an optimal environment for catalysis. Recent breakthroughs include the development of an artificial metathase for ring-closing metathesis reactions in cellular environments [5]. This approach combines computational design with genetic optimization to achieve high binding affinity (K_D ≤ 0.2 μM) between the protein scaffold and cofactor through supramolecular anchoring [5].

Supramolecular anchoring strategies enable precise positioning of metal cofactors within designed protein pockets. Unlike covalent attachment, supramolecular interactions allow for cofactor exchange and tuning of the catalytic environment. The design process involves:

- Identifying complementary interaction surfaces between cofactor and protein

- Engineering hydrophobic pockets for cofactor binding

- Incorporating hydrogen bond donors/acceptors for precise orientation

- Creating steric constraints to shield reactive intermediates

Scaffold selection criteria for ArM design prioritize hyperstable de novo-designed proteins with engineered binding sites rather than repurposing natural scaffolds. These designs offer enhanced tunability and stability, enabling function in complex cellular environments [5]. The closed alpha-helical toroidal repeat proteins (dnTRPs) have proven particularly effective due to their high thermostability (T₅₀ > 98°C) and engineerability [5].

Protocol for Artificial Metathase Design and Optimization

Computational Design Pipeline:

- Step 1: Cofactor Design: Modify synthetic cofactors to include polar motifs for specific interactions with protein scaffolds (e.g., sulfamide groups for hydrogen bonding)

- Step 2: Scaffold Design: Use computational suites (RifGen/RifDock) to enumerate interacting amino acid rotamers and dock ligands into de novo protein cavities

- Step 3: Sequence Optimization: Employ Rosetta FastDesign to optimize hydrophobic contacts and stabilize key hydrogen-bonding residues

- Step 4: Binding Affinity Enhancement: Introduce tryptophan residues near the binding site to enhance hydrophobicity and cofactor affinity

Directed Evolution Protocol:

- Library Generation: Create mutant libraries targeting residues surrounding the cofactor binding pocket

- Screening Conditions: Develop cell-free extract screening systems supplemented with additives (e.g., Cu(Gly)₂) to mitigate glutathione interference

- Performance Assessment: Evaluate variants based on turnover number (TON) and biocompatibility

- Iterative Optimization: Perform multiple rounds of mutation and screening to achieve significant catalytic improvements (≥12-fold enhancement documented) [5]

Table 3: Performance Metrics for Artificial Metathase Design

| Design Stage | Key Parameter | Initial Performance | Optimized Performance | Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Binding | Dissociation Constant (K_D) | 1.95 ± 0.31 μM | ≤0.2 μM | Tryptophan fluorescence quenching |

| Catalytic Efficiency | Turnover Number (TON) | 40 ± 4 | ≥1,000 | Product formation rate in cell-free extracts |

| Thermal Stability | T₅₀ (30 min incubation) | Not applicable | >98°C | Temperature-dependent unfolding |

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflows

AI-Driven De Novo Enzyme Design

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized de novo enzyme design by enabling precise, from-scratch prediction of enzyme structures with tailored functions [4]. Generative AI models have demonstrated remarkable success in creating entirely novel enzyme folds distinct from natural proteins, exemplified by the design of a de novo serine hydrolase with catalytic efficiencies (kcat/Km) up to 2.2 × 10⁵ M⁻¹·s⁻¹ [22].

RFdiffusion represents a groundbreaking approach that fine-tunes the RoseTTAFold structure prediction network for protein structure denoising tasks [19]. This generative model enables unconditional and topology-constrained protein monomer design, protein binder design, symmetric oligomer design, and enzyme active site scaffolding. The method experimentally demonstrated the capacity to design diverse functional proteins from simple molecular specifications, with characterization of hundreds of designed symmetric assemblies, metal-binding proteins, and protein binders confirming design accuracy [19].

Theozyme-Based Design implements an "inside-out" strategy where catalytic sites are designed first by modeling the transition state of the target reaction [22]. Quantum mechanical calculations identify optimal arrangements of catalytic groups to stabilize transition states, creating theoretical enzyme models ("theozymes") that serve as blueprints for subsequent scaffold design. This approach has matured through tools like RosettaMatch, which places theozyme-derived catalytic motifs into protein backbones [22].

Consensus Structure Identification

Complementing theozyme approaches, consensus structure identification employs data-driven strategies to extract conserved geometrical features from natural enzyme families [22]. Analyzing structural databases like the Protein Data Bank reveals conserved spatial relationships and hydrogen-bonding networks associated with catalytic function. This method successfully identifies key catalytic motifs like the serine hydrolase triad (Ser-His-Asp) and associated oxyanion holes, providing evolutionary-validated templates for enzyme design [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for Advanced Enzyme Design

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction & Validation | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold, ESMFold | Protein structure prediction from sequence | Validation of de novo enzyme designs, structural analysis |

| Generative Design Platforms | RFdiffusion, GENzyme, SCUBA-D | De novo protein backbone generation | Creating novel enzyme scaffolds around functional motifs |

| Sequence Design Tools | ProteinMPNN, LigandMPNN | Inverse protein folding for sequence design | Optimizing sequences for target structures and cofactor binding |

| Molecular Modeling & Simulation | Rosetta, FoldX, GROMACS | Energy calculations, docking, dynamics | Virtual mutagenesis, stability predictions, binding affinity |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, Q-Chem | Transition state modeling, theozyme design | Catalytic mechanism analysis, active site optimization |

| Directed Evolution Systems | Cell-free expression, microfluidics | High-throughput screening of enzyme variants | Optimization of initially designed enzymes for enhanced function |

| Biophysical Characterization | SPR, ITC, CD, fluorescence spectroscopy | Binding affinity, structural stability | Validation of cofactor binding, thermal stability assessment |

The integration of advanced computational design with experimental optimization has transformed enzyme engineering from an art to a predictive science. The key objectives of thermostability, solvent tolerance, and cofactor compatibility represent interconnected challenges that must be addressed simultaneously for successful de novo enzyme design. Short-loop engineering and cavity-filling strategies provide robust approaches for enhancing thermostability, while surface engineering techniques enable operation in non-aqueous environments. Most remarkably, the de novo creation of artificial metalloenzymes demonstrates the potential to expand catalytic repertoire beyond natural evolution, enabling abiotic chemistry in biological systems.

Future advances will likely emerge from increasingly sophisticated AI models trained on expanding structural databases, improved quantum mechanical methods for modeling reaction mechanisms, and high-throughput experimental characterization that provides feedback for computational refinement. As these technologies mature, the precise design of enzymes with tailored stability, solvent compatibility, and catalytic functions will accelerate progress in sustainable chemistry, therapeutic development, and synthetic biology.

The field of de novo enzyme design aims to create novel biocatalysts from first principles, expanding the repertoire of biological catalysis to include non-natural reactions. A fundamental challenge in this endeavor is the successful incorporation of artificial metal cofactors—the abiotic catalytic centers that enable new-to-nature functions. The strategy used to anchor these cofactors within protein scaffolds directly determines the stability, activity, and biocompatibility of the resulting artificial metalloenzyme (ArM). Researchers primarily employ three strategic approaches: supramolecular anchoring (utilizing non-covalent interactions), covalent anchoring (forming chemical bonds), and dative anchoring (leveraging metal-coordination bonds) [23]. Within the context of de novo design, where protein scaffolds are computationally conceived rather than naturally evolved, the choice of anchoring strategy profoundly influences the design process, the final catalytic efficiency, and the potential for in-cellulo applications. This technical guide examines these core anchoring strategies, their implementation, and their integration into the broader framework of designing novel enzyme functions.

Supramolecular Anchoring

Principle and Strategic Value

Supramolecular anchoring relies on non-covalent interactions—such as hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic effects, and π-π interactions—to embed a synthetic cofactor within a protein binding pocket [23]. This approach is particularly valuable in de novo design, as it allows designers to treat the cofactor and the protein as two separate modules. The design process can thus focus on creating a pocket with complementary geometry and chemical properties to the cofactor, without the constraints of designing specific covalent attachment points. A key advantage is the potential for cofactor exchange or replacement, facilitating screening and optimization. However, a potential drawback is the risk of cofactor leaching, especially under dilute conditions or in dynamic cellular environments.

Implementation in De Novo Design

A prominent example of this strategy is the creation of an artificial metathase for ring-closing metathesis. Researchers designed a de novo hyper-stable alpha-helical toroidal repeat protein (dnTRP) scaffold to host a tailored Hoveyda-Grubbs ruthenium catalyst (Ru1) [23]. The design process involved computational docking of the Ru1 cofactor into the scaffold's cavity, explicitly designing the binding pocket to provide supramolecular anchoring via:

- Hydrogen bonds between the protein backbone and the polar sulfamide group of the Ru1 cofactor.

- Hydrophobic interactions with the cofactor's mesityl moieties.

This designed supramolecular interface achieved a high binding affinity (KD ≤ 0.2 μM), demonstrating that de novo proteins can be engineered to tightly bind abiotic cofactors without covalent or dative links [23].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Cofactor Anchoring Strategies

| Anchoring Strategy | Interaction Type | Design Complexity | Binding Strength | Risk of Cofactor Leaching | Ease of Cofactor Incorporation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supramolecular | Non-covalent (H-bond, hydrophobic) | High (requires precise pocket design) | Moderate to Strong (nM-μM KD) | Moderate | High |

| Covalent | Covalent bond | Moderate (requires addressable residues) | Strong (Irreversible) | Low | Low to Moderate |

| Dative | Metal coordination | Moderate (requires coordinating residues) | Strong | Low | Moderate |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Binding Affinity via Tryptophan Fluorescence Quenching

Objective: To determine the dissociation constant (KD) for a supramolecularly bound cofactor-protein complex.

- Protein Preparation: Express and purify the de novo designed protein (e.g., dnTRP_18) with a fluorescent residue (e.g., Tryptophan) positioned near the binding pocket.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of protein solutions at a fixed concentration (e.g., 1 μM) in a suitable buffer (e.g., pH 4.2).

- Titration: Titrate increasing concentrations of the cofactor (e.g., Ru1) into the protein solution.

- Fluorescence Measurement: After each addition, measure the fluorescence emission intensity of the tryptophan upon excitation at 295 nm.

- Data Analysis: Plot the measured fluorescence intensity (or quenching efficiency) against the cofactor concentration. Fit the data to a binding isotherm model (e.g., one-site specific binding) to calculate the KD value [23].

Covalent and Dative Anchoring Strategies

Covalent Anchoring

Covalent anchoring involves the formation of irreversible chemical bonds between the protein scaffold and the synthetic cofactor. This is often achieved by reacting engineered cysteine residues (thiol groups) with functional groups like maleimides or iodoacetamides on the cofactor [23]. The primary advantage of this method is the exceptional complex stability it confers, virtually eliminating cofactor leaching and making it suitable for harsh reaction conditions. A significant disadvantage is that the bond formation can be challenging to perform in living cells, and the fixed attachment point may restrict conformational dynamics necessary for optimal catalysis.

Dative Anchoring

Dative anchoring, or metal coordination, utilizes the native ligating atoms of protein side chains (e.g., His, Cys, Asp, Glu) to coordinate directly to a metal center in the cofactor [23]. This strategy mimics the cofactor binding in many natural metalloenzymes. It provides strong, directional binding, though the bond is potentially reversible. The design process involves positioning coordinating residues in the scaffold's active site to match the geometric constraints of the metal cofactor. While this can yield very active ArMs, a major challenge is the potential for mis-metalation in a cellular environment, where endogenous metal ions can compete for the binding site.

Table 2: Comparison of Anchoring Strategy Performance in Artificial Metalloenzymes

| Performance Metric | Supramolecular | Covalent | Dative |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Turnover Number (TON) | ≥ 1,000 [23] | Varies (often high) | Varies (often high) |

| Stability in Complex Media | High (with optimized binding) | Very High | High (subject to metal competition) |

| In Cellulo Compatibility | Demonstrated [23] | Can be challenging | Can be challenging |

| Directed Evolution Friendliness | High (scaffold can be evolved independently) | Moderate | Moderate |

Integration with De Novo Enzyme Design Workflows

The creation of a functional ArM is an iterative process that integrates anchoring strategy with computational design and experimental optimization. The following workflow diagram illustrates the generic pathway for developing an ArM, which can be tailored for any of the three anchoring strategies.

ArM Development Workflow

Computational Design and Experimental Validation

The initial phase involves computational design of the protein scaffold. For supramolecular anchoring, tools like Rosetta and the RifGen/RifDock suite are used to enumerate amino acid rotamers around the cofactor and dock it into de novo scaffolds (e.g., dnTRPs) [23]. The design is evaluated on metrics like interface quality and pocket pre-organization. The selected designs are then expressed, purified, and assembled with the cofactor.

Catalytic performance is tested under relevant conditions. For example, artificial metathases were tested for ring-closing metathesis activity with a diallylsulfonamide substrate [23]. Key analytical methods include:

- Chromatography (e.g., LC-MS/GC): To quantify substrate conversion and product formation.

- Native Mass Spectrometry: To confirm 1:1 cofactor:protein stoichiometry.

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography: To verify complex formation and stability.

Optimization via Directed Evolution

Even with sophisticated computational design, initial ArMs often require optimization. Directed evolution is a powerful method for this, where iterative cycles of mutagenesis and high-throughput screening are used to enhance catalytic performance (e.g., TON, enantioselectivity) and biocompatibility [23] [24]. This process can improve the activity of a designed ArM by more than 12-fold, making it compatible with complex environments like bacterial cytoplasm [23]. Screening can be performed in cell-free extracts (CFE) under optimized conditions, such as adjusted pH and the addition of additives like bis(glycinato)copper(II) to mitigate the effects of cellular metabolites like glutathione [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Developing Artificial Metalloenzymes

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| De Novo Protein Scaffolds | Provides a stable, customizable framework for cofactor binding. | Hyper-stable dnTRP scaffolds for supramolecular anchoring [23]. |

| Hoveyda-Grubbs Catalyst Derivatives | Abiotic cofactor for olefin metathesis reactions. | Ru1 catalyst for artificial metathase design [23]. |

| E. coli Expression Systems | Standard host for recombinant protein production. | Expression of his-tagged dnTRP proteins [23]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | Computational protein design and modeling. | Designing and optimizing cofactor-binding pockets [23] [3]. |

| Cell-Free Extracts (CFE) | Mimics the intracellular environment for screening. | High-throughput screening of ArM variants in a biologically complex medium [23]. |

| Bis(glycinato)copper(II) [Cu(Gly)₂] | Additive to mitigate reducing environments in lysates. | Oxidation of glutathione in CFE to protect ruthenium cofactors [23]. |

The strategic selection of an anchoring method—supramolecular, covalent, or dative—is a foundational decision in the de novo design of artificial metalloenzymes. Supramolecular strategies offer a modular and design-friendly approach that has proven highly successful for creating ArMs functional in living cells. Covalent and dative strategies provide robust stability, though they present different challenges for in-cellulo implementation. The integration of sophisticated computational design, leveraging tools like Rosetta and machine learning, with powerful experimental optimization techniques like directed evolution, creates a robust framework for advancing the field. As computational methods continue to improve, the precision with which cofactor environments can be designed will increase, further enabling the creation of efficient and selective biocatalysts for a wide range of abiotic transformations in both industrial and biomedical contexts.

Artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs) present a promising avenue for abiotic catalysis within living systems. However, their in vivo application is currently limited by critical challenges, particularly in selecting suitable protein scaffolds capable of binding abiotic cofactors and maintaining catalytic activity in complex media. This case study details a pronounced leap in the de novo design and in cellulo engineering of an artificial metathase—an ArM designed for ring-closing metathesis (RCM) for whole-cell biocatalysis. The approach integrates a tailored metal cofactor into a hyper-stable, de novo-designed protein. By combining computational design with genetic optimization, a high binding affinity (KD ≤ 0.2 μM) between the protein scaffold and cofactor was achieved through supramolecular anchoring. Directed evolution of the artificial metathase yielded variants exhibiting excellent catalytic performance (turnover number ≥1,000) and biocompatibility, paving the way for abiological catalysis in living systems [5] [25].

The field of biocatalysis is increasingly attractive for synthetic chemistry due to its benefits in sustainability, step economy, and exquisite selectivity. A frontier in this field is the creation of artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs), which aim to merge the catalytic versatility of synthetic metal complexes with the advantageous performance of enzymes in biological environments [5]. A primary goal is to catalyze "new-to-nature" reactions—transformations with no equivalent in natural biology—within living cells [26].

Olefin metathesis, a reaction for which the 2005 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded, is one such powerful transformation. It enables the rearrangement of carbon-carbon double bonds and is widely used in organic synthesis and materials science [27]. Despite its utility, the application of olefin metathesis in chemical biology has been limited because conventional ruthenium catalysts often suffer from poor biocompatibility, instability in aqueous media, and deactivation by cellular metabolites like glutathione [5].

This case study, framed within a broader thesis on the de novo design of novel enzyme functions, examines a groundbreaking solution to these challenges. It chronicles the rational design and evolution of an artificial metathase, demonstrating the feasibility of performing abiotic catalysis in the complex cytoplasmic environment of E. coli.

Computational De Novo Design of the Host Protein

Design Strategy and Rationale

The design strategy hinged on a synergistic approach: engineering both a synthetic cofactor and a de novo-designed protein scaffold to complement each other [5].

- Cofactor Design: A derivative of the Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst, termed Ru1, was synthesized. A key feature was the incorporation of a polar sulfamide group, intended to improve aqueous solubility and serve as a handle for forming supramolecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds) with the host protein [5].

- Scaffold Selection: De novo-designed closed alpha-helical toroidal repeat proteins (dnTRPs) were selected as the scaffold. These proteins are hyper-stable (T50 > 98°C), highly engineerable, and possess a suitably sized pocket for ligand binding, making them ideal for withstanding the rigors of cytoplasmic catalysis and engineering [5].

Computational Methodology and Workflow

The process for designing the host protein involved a multi-stage computational pipeline [5] [28]:

- Rotamer Interaction Field (RIF) Generation: The

RifGentool was used to enumerate potential interacting amino acid rotamers around the cofactor, Ru1. - Ligand Docking: The

RifDocksuite was employed to dock the Ru1 cofactor along with key interacting residues into the cavities of pre-existing dnTRP scaffolds (e.g., PDB ID: 4YXX). - Sequence Optimization: The docked structures were subjected to protein sequence optimization using Rosetta FastDesign. This step refined hydrophobic contacts with the cofactor and stabilized key H-bonding residues to pre-organize the binding pocket for catalysis.

- Design Selection: The resulting design models were evaluated based on computational metrics describing the protein-cofactor interface and pocket pre-organization. This process yielded 21 initial designs for experimental validation [5].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated computational design workflow:

Experimental Validation and Optimization

Initial Screening and Binding Affinity Improvement

The 17 soluble dnTRPs were purified and assembled into ArMs by treatment with the Ru1 cofactor. Their catalytic performance was assessed using the RCM of diallylsulfonamide (1a) as a model reaction [5].

- Primary Screen: All Ru1·dnTRP complexes outperformed the free Ru1 cofactor (TON 40 ± 4). The best performers, dnTRP10, dnTRP17, and dnTRP_18, achieved TONs of approximately 180-194 [5].

- Lead Selection: dnTRP_18 was selected for further study due to its high activity and robust expression [5].

- Affinity Engineering: To improve the binding affinity, two residues (F43 and F116) lining the binding pocket were individually mutated to tryptophan. The resulting variants, dnTRP18F43W and dnTRP18F116W, showed a nearly tenfold increase in affinity, with KD values of 0.26 ± 0.05 μM and 0.16 ± 0.04 μM, respectively. The dnTRP18F116W variant was designated dnTRP_R0 for subsequent evolution campaigns [5].

Table 1: Key Characterization Data for Lead Artificial Metathase Designs

| Protein Variant | Binding Affinity (KD, μM) | Catalytic Performance (TON) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Ru1 Cofactor | Not Applicable | 40 ± 4 | Baseline activity in buffer |

| Ru1·dnTRP_18 | 1.95 ± 0.31 | 194 ± 6 | Initial lead design |

| Ru1·dnTRP_R0 (F116W) | 0.16 ± 0.04 | ~200 (Parental) | High-affinity variant, used for directed evolution |

| Evolved Ru1·dnTRP | Not Reported | ≥ 1,000 | Post-directed evolution performance |

Directed Evolution in a Cellular Environment

To optimize the ArM for function in biologically relevant conditions, a directed evolution campaign was initiated. A key development was the establishment of a screening system using E. coli cell-free extracts (CFE) to mimic the cytoplasmic environment [5].

- Screening Platform: The CFE system was supplemented with bis(glycinato)copper(II) [Cu(Gly)2], which partially oxidizes glutathione, a key cellular nucleophile that can deactivate the ruthenium cofactor. This step was critical for achieving high TONs (197 ± 7 with Cu(Gly)2 vs. 152 ± 16 without) in the complex media [5].

- Evolution Strategy: Using this screening platform, iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening were performed on the dnTRP_R0 scaffold. This process yielded evolved variants with a ≥12-fold increase in catalytic performance compared to the initial designs, achieving TONs of ≥1,000 [5].

The overall experimental workflow, from initial screening to evolved catalyst, is summarized below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The development and application of the artificial metathase relied on a suite of key reagents and methodologies.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Artificial Metathase Engineering

| Reagent / Tool | Function and Role in the Study |

|---|---|

| Ru1 Cofactor | A tailored Hoveyda-Grubbs type catalyst with a polar sulfamide group; the abiotic catalytic center of the ArM [5]. |

| dnTRP Scaffold | A hyper-stable, de novo-designed alpha-helical repeat protein; provides a stable, engineerable host for the cofactor [5]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | A computational protein design platform; used for sequence optimization and binding pocket design around the Ru1 cofactor [5] [28]. |

| RifGen / RifDock | Computational tools for generating rotamer interaction fields and docking small molecules into protein scaffolds [5] [28]. |

| E. coli Cell-Free Extract (CFE) | A complex lysate used for screening; mimics the cytoplasmic environment to identify variants with robust biocompatibility and activity [5]. |

| Bis(glycinato)copper(II) [Cu(Gly)2] | A glutathione-oxidizing agent; added to screening assays to mitigate catalyst deactivation by cellular nucleophiles [5]. |

This case study exemplifies the power of integrating computational design with directed evolution to create novel biocatalysts. The successful development of an artificial metathase for cytoplasmic olefin metathesis underscores several critical advances:

- Synergistic Design: The concurrent engineering of the cofactor and the protein scaffold led to a system with high intrinsic affinity and activity.

- Stability as a Key Enabler: The use of a hyper-stable de novo scaffold provided a robust platform that could withstand the demands of both evolution and the cellular environment.

- Relevant Screening Conditions: The implementation of a screening system in cell-free extracts was pivotal for optimizing the ArM for performance in a complex, biologically relevant milieu.

This work provides a versatile blueprint for creating and optimizing ArMs for a wide range of abiological reactions, significantly expanding the toolbox for synthetic biology and pharmaceutical development. Future work will likely focus on expanding the reaction scope of de novo-designed ArMs and further improving their catalytic efficiency and specificity through advanced computational models and machine learning approaches [29] [30].

The Designer's Toolkit: Integrated Workflows from Computational Prediction to In Vivo Application

The de novo design of novel enzyme functions represents a paradigm shift in biotechnology, moving beyond the modification of existing natural enzymes to the computational creation of entirely new protein scaffolds from first principles. This approach allows researchers to address fundamental scientific questions and engineer biocatalysts for reactions not found in nature, overcoming the limitations of natural enzymes, which often exhibit narrow operating conditions, limited stability, or insufficient activity for industrial applications [3] [31]. Computational scaffolding is the cornerstone of this process, wherein stable protein backbones are designed in silico to precisely position catalytic residues and cofactors for optimal function.

This technical guide examines the core methodologies—Rosetta, RifDock, and emerging deep-learning tools—for constructing de novo protein scaffolds. It details their underlying principles, provides actionable experimental protocols, and situates them within the broader context of functional enzyme design, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the foundational knowledge to implement these cutting-edge strategies.

Core Principles of Computational Scaffolding

Computational scaffolding aims to create a stable, minimal, and designable protein structure that can host a predefined functional motif. Two primary strategies dominate the field:

- Structure-Based Design: This approach uses physical energy functions and spatial pattern algorithms to derive stable protein conformations from three-dimensional constraints. It relies on principles of energetic stabilization and shape complementarity to build scaffolds de novo [3] [32].

- Sequence-Based Design: This strategy employs deep generative models, trained on large datasets of natural protein sequences and structures, to learn co-evolutionary patterns and generate novel, functional sequences from data-driven principles [3].

A key concept in de novo enzyme design is the "inside-out" strategy, which begins by defining the functional site. A minimal active site model, or theozyme (theoretical enzyme), is constructed using quantum mechanical (QM) calculations to identify the optimal spatial arrangement of catalytic residues for stabilizing the reaction's transition state [22]. The computational challenge is then to design a novel protein scaffold that can fold and structurally support this theozyme with atomic-level precision.

Key Methodologies and Tools

The Rosetta Software Suite

Rosetta is a foundational suite of algorithms for de novo protein design and structure prediction. Its methodologies are grounded in physicochemical principles and fragment-based assembly.

- Fundamental Principles: Rosetta uses a Monte Carlo approach to sample conformational space, guided by a physically derived energy function that favors low-energy, stable states. This function balances terms for van der Waals interactions, solvation, hydrogen bonding, and electrostatics [3].

- Key Protocols:

- Motif Placement (RosettaMatch): The functional motif (theozyme) is positioned into a large library of protein backbone scaffolds. The algorithm identifies locations where the catalytic geometry can be accommodated without steric clashes [22].

- Sequence Design (FastDesign): Once a scaffold and motif placement are selected, Rosetta's FastDesign protocol optimizes the amino acid sequence to stabilize both the overall fold and the functional site. This involves iterative cycles of side-chain repacking and backbone minimization [5].

- Application in Scaffolding: Rosetta has been used to design entire protein folds, such as triosephosphate isomerase (TIM) barrels. By revisiting basic topology principles, researchers used Rosetta to create oval-shaped TIM barrels, which are more suitable for incorporating small-molecule binding sites than naturally occurring circular barrels [32].

The RifDock Platform

RifDock is a specialized tool within the Rosetta ecosystem for high-throughput docking of small molecules into protein scaffolds, crucial for designing artificial metalloenzymes (ArMs).