De Novo Enzyme Design: Overcoming Core Challenges in Computational Protein Engineering

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current challenges and solutions in de novo enzyme design.

De Novo Enzyme Design: Overcoming Core Challenges in Computational Protein Engineering

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current challenges and solutions in de novo enzyme design. Targeting researchers and biotech professionals, it explores the foundational principles of computational enzyme engineering, details cutting-edge methodologies like deep learning and generative models, and addresses critical troubleshooting steps for optimizing activity and stability. It further examines rigorous validation frameworks and comparative analyses against natural enzymes. The synthesis offers a strategic roadmap for advancing the field toward robust biomedical and industrial applications.

The De Novo Enzyme Design Paradigm: Core Principles and Persistent Hurdles

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My designed enzyme shows excellent in silico binding affinity but negligible catalytic activity in vitro. What are the primary failure points? A: This is a classic manifestation of the energy landscape problem. The in silico model likely identified a low-energy conformation that is not the catalytically competent one, or the landscape is too flat, leading to non-productive binding.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Transition State Stabilization: Re-run QM/MM calculations focusing specifically on the reaction coordinate and transition state geometry. The designed active site may pre-organize ground states but not the transition state.

- Analyze Conformational Dynamics: Perform microsecond-scale molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to check if the designed enzyme samples the intended active site conformation >95% of the simulation time. Look for rogue side-chain rotamers or backbone fluctuations that collapse the active site.

- Check Electrostatic Pre-organization: Use software like

APBSto calculate and visualize the electrostatic potential surface of your designed model versus a natural enzyme analog. Misaligned fields drastically reduce catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM).

Q2: During RosettaDesign, my protein sequence is converging to a hydrophobic "ball" with no functional pocket. How can I guide it towards a foldable, functional structure? A: This indicates that your energy function is dominated by the "hydrophobic collapse" term, overriding functional constraints.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Increase Restraint Weights: Dramatically increase the weight of your catalytic site distance (e.g.,

AtomPairConstraint) and geometry restraints (AngleConstraint,DihedralConstraint). This forces the algorithm to satisfy functional geometry during folding. - Use a Fragment Library from a Structural Analog: Instead of generic fragments, use a fragment library generated from the PDB structure of a remote homolog or a topologically similar scaffold. This biases sampling towards relevant backbone conformations.

- Apply Negative Design: Introduce a

SiteConstraintthat disfavors the burial of polar atoms intended to be solvent-exposed in the active site, preventing its collapse.

- Increase Restraint Weights: Dramatically increase the weight of your catalytic site distance (e.g.,

Q3: My de novo enzyme passes all computational checks but aggregates during expression and purification. What are the best experimental remediation strategies? A: Aggregation suggests the computational model identified a deep energy minimum that is not the soluble, monomeric state, or that kinetic traps exist during folding in vivo.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Screen Expression Conditions: Use a factorial design to screen temperature (18°C, 25°C, 30°C), inducer concentration (IPTG from 0.1 to 1.0 mM), and rich vs. minimal media.

- Employ Fusion Tags & Cleavage: Express the enzyme as a fusion with solubility-enhancing tags (e.g., MBP, GST, SUMO). Include a protease cleavage site (e.g., TEV, HRV 3C) for tag removal post-purification.

- Incorporate Stability Paints: Use Rosetta's

FastDesignwith a heavily weightedscore3orbeta_nov16score function for 2-3 design/relax cycles focusing only on surface residues to improve solubility without altering the core or active site.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Computational Validation of Active Site Pre-organization via Molecular Dynamics Purpose: To assess the stability and conformational sampling of a designed enzyme's active site over time. Methodology:

- System Preparation: Using the designed PDB file, protonate the structure at pH 7.0 with

PDB2PQRorH++. Solvate in a cubic TIP3P water box with a 10 Å buffer. Add ions (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) to neutralize charge. - Energy Minimization: Perform 5,000 steps of steepest descent minimization to remove steric clashes.

- Equilibration: Run a two-stage NVT and NPT equilibration for 100 ps each, gradually heating the system to 300 K and stabilizing pressure at 1 bar.

- Production MD: Run an unrestrained production simulation for 500 ns to 1 µs. Use a 2-fs integration time step. Save frames every 10 ps.

- Analysis: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the active site residue backbone and side-chain heavy atoms. Compute the radius of gyration (Rg). Use a clustering algorithm (e.g., GROMOS) to identify dominant conformational states. Quantify the percentage of simulation time where key catalytic distances (e.g., H-bond donor-acceptor) are within functional range (<3.2 Å).

Protocol 2: Experimental Kinetic Characterization of De Novo Enzymes Purpose: To determine the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) and compare it to computational predictions. Methodology:

- Assay Development: Establish a continuous spectrophotometric or fluorometric assay for the target reaction. Identify a wavelength where substrate and product have a differential extinction coefficient.

- Enzyme Purification: Purify the His-tagged enzyme via Ni-NTA affinity chromatography. Elute with an imidazole gradient (20-500 mM). Desalt into assay buffer (e.g., 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl) using a PD-10 column.

- Initial Velocity Measurements: For a fixed, low enzyme concentration (e.g., 10-100 nM), measure initial velocity (v0) across a range of substrate concentrations (typically from 0.2x to 5x the estimated KM). Perform each measurement in triplicate.

- Data Fitting: Fit the Michaelis-Menten equation (v0 = (Vmax * [S]) / (KM + [S])) to the averaged data using non-linear regression (e.g., in Prism, GraphPad). Extract kcat (Vmax / [E]total) and KM.

- Control Experiments: Run substrate-only and enzyme-only controls. Perform a linearity check with time and enzyme concentration to ensure steady-state conditions.

Table 1: Common Computational Metrics and Their Target Values for Validated Designs

| Metric | Tool/Method | Target Value for Success | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ddG (Folding) | Rosetta ddg_monomer |

≤ -15 REU (Rosetta Energy Units) | Predicts stable folding. More negative is better. |

| Catalytic Site RMSD | MD Simulation Clustering | ≤ 1.0 Å from design model in >70% of frames | Active site maintains designed geometry. |

| Pocket Hydrophobicity | fpocket or PyMOL Cavity |

Negative average hydrophobicity score | Favors polar/charged substrate binding. |

| Transition State Energy | QM/MM (e.g., Gaussian/AMBER) | Lower than reaction in water by ≥ 10 kcal/mol | Indicates significant rate enhancement. |

| Packstat Score | Rosetta packstat |

≥ 0.65 | Indicates well-packed, native-like core. |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Outcomes for Low-Activity Designs

| Problem Identified | Remediation Strategy | Typical Improvement (Fold Δ in kcat/KM) |

|---|---|---|

| Misaligned catalytic residues | Fixed-backbone sequence redesign focused on active site | 10 - 100x |

| Poor substrate binding | Iterative docking & hydrophobic pocket redesign | 5 - 50x |

| High conformational entropy | Introduction of distal stabilizing mutations (from FoldIt) | 2 - 20x |

| Aggregation | Surface entropy reduction or fusion tag strategy | Enables measurement (from 0 to measurable) |

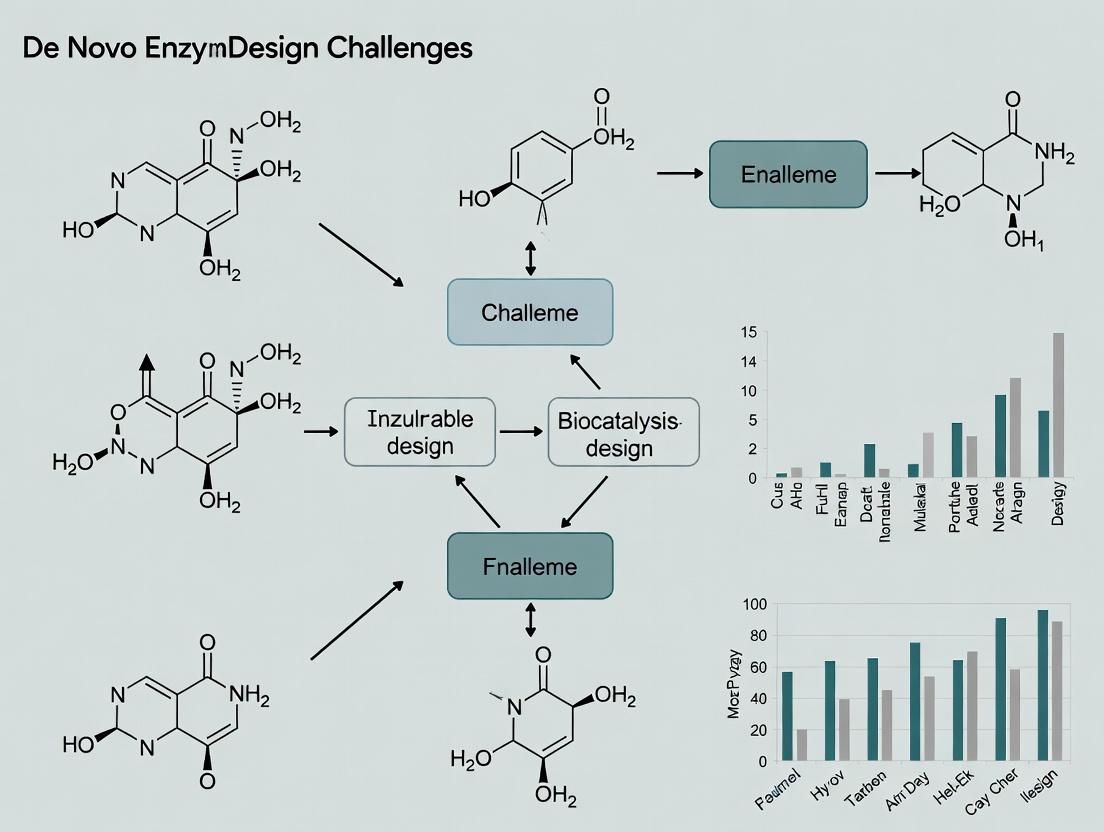

Diagrams

Diagram 1: De Novo Enzyme Design & Validation Workflow

Diagram 2: Key Energy Landscapes in Enzyme Design

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for De Novo Enzyme Design & Testing

| Item | Function in Research | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Assembly Mix | For error-free assembly of synthetic genes encoding designed enzymes. | NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix (NEB #E2621) |

| Expression Vector with Cleavable Tag | Enables high-yield soluble expression and facile purification. | pET-28a(+) with TEV protease site (Novagen #69864) |

| Affinity Purification Resin | One-step purification of tagged enzymes. | Ni-NTA Superflow Cartridge (Qiagen #30731) |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Column | Polishing step to remove aggregates and obtain monodisperse enzyme. | HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg (Cytiva #28989333) |

| Fluorogenic Substrate Analogue | Enables sensitive, continuous activity assays for kinetic characterization. | Custom synthesis from companies like Sigma-Aldrich or Enzo. |

| Thermal Shift Dye | Measures protein melting temperature (Tm) to assess stability. | SYPRO Orange Protein Gel Stain (Invitrogen #S6650) |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates folding and dynamics to explore energy landscapes. | GROMACS 2023 (Open Source), AMBER22. |

Technical Support Center

FAQs & Troubleshooting

Q1: My computationally designed enzyme shows high predicted activity in QM/MM simulations but negligible activity in the wet lab assay. What are the primary culprits? A: This common discrepancy often stems from incomplete modeling. The catalytic triad (or analogous motif) is necessary but insufficient. Key troubleshooting areas include:

- Protein Dynamics: Your static model may not account for essential conformational sampling. The transition state may be accessible only through a rare, high-energy protein motion not captured in short simulations.

- Electrostatic Preorganization: The designed active site may not optimally stabilize the transition state's charge distribution. Check the electrostatic potential maps around your modeled transition state.

- Substrate Transport/Product Release: You may have perfectly modeled the chemical step but neglected how the substrate enters or the product leaves a deeply buried active site, causing kinetic bottlenecks.

Q2: When integrating machine-learned force fields with traditional QM methods, my calculations become intractable. How can I streamline this workflow? A: The issue is the scaling of QM region size. Adopt a multi-scale, adaptive approach.

- Use the ML force field for extensive equilibrium MD to identify critical reactive configurations.

- For these snapshot configurations, perform careful QM region selection. Systematically test if key residues beyond the first shell perturb the reaction barrier (>1-2 kcal/mol).

- Implement an adaptive partitioning scheme where residues switch between MM and QM descriptions based on distance or energy criteria during a QM/MM MD simulation.

Q3: My de novo enzyme shows promiscuous activity against my target substrate and similar analogs. How can I refine specificity? A: Promiscuity indicates a broadly permissive active site. To engineer specificity:

- Analyze Binding Modes: Run MD simulations of the top competing substrates. Create a comparative table of interaction fingerprints (H-bonds, π-stacks, hydrophobic contacts).

- Introduce Negative Design: Incorporate residues that create steric clashes or unfavorable electrostatic interactions with the most common off-target features, while maintaining compatibility with your true substrate.

- Optimize Transition State Complementarity: Specificity is often greatest at the transition state. Ensure your design maximizes shape and electrostatic complementarity specifically to the transition state of your desired reaction, not just the ground state substrate.

Experimental Protocol: Validating Computational Designs with Stopped-Flow Kinetics

Objective: To determine the pre-steady-state kinetic parameters (k_obs, burst amplitude) of a designed enzyme, distinguishing the chemical step from substrate binding/product release.

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation:

- Purify designed enzyme to homogeneity (SEC, >95% purity). Concentrate to high-μM range in assay buffer.

- Prepare substrate solution in identical buffer, ensuring solubility. Include a fluorescent probe or chromophore for detection.

Instrument Setup:

- Equilibrate stopped-flow instrument at desired temperature (e.g., 25°C).

- Use appropriate filters/monochromators for your detection method (e.g., fluorescence emission at 450 nm for a coumarin product).

- Perform 3-5 mixing shots of buffer alone to establish baseline stability.

Data Acquisition:

- Load syringes: Syringe A with enzyme (e.g., 50 μM), Syringe B with substrate (e.g., 2-10x varied concentration over KM).

- Perform rapid mixing (dead time ~1-2 ms) and record signal trajectory for 5-10 half-lives.

- Repeat each condition 5-7 times for averaging.

Data Analysis:

- Fit individual traces to a single or double exponential equation.

- Plot observed rate constant (kobs) vs. substrate concentration. Fit to a hyperbolic equation: kobs = (kcat * [S]) / (KM + [S]) + k_off.

- The y-intercept provides information on the reverse/product release rate (koff). The maximal kobs approximates k_cat.

Quantitative Data Summary: Common Pitfalls in Enzyme Design Validation

Table 1: Discrepancies Between Calculated and Measured Enzyme Parameters

| Parameter | Computational Prediction | Typical Experimental Range (Initial Designs) | Common Cause of Discrepancy |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔG‡ (kcal/mol) | 15-18 | >22 (or no activity) | Missing protein reorganization energy, imperfect TS stabilization. |

| k_cat (s⁻¹) | 1-10 | 10⁻³ to 10⁻¹ | Over-optimized active site rigidity, inefficient proton relays. |

| K_M (mM) | 0.1-1.0 | 5-50 (or no binding) | Incorrect modeling of substrate desolvation, lack of conformational selection. |

| Thermal Stability (Tm, °C) | ΔTm < ±2 | ΔTm -10 to -20 °C | Introduction of catalytic residues destabilizes core packing. |

Visualization: Multi-Scale Enzyme Design & Validation Workflow

Diagram Title: Multi-Scale De Novo Enzyme Design Pipeline

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Computational & Experimental Enzyme Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| CHARMM36/AMBER ff19SB Force Field | High-accuracy molecular mechanics force field for protein MD simulations; essential for sampling conformational dynamics. |

| ORCA or Gaussian Software | Quantum chemistry packages for calculating transition state geometries and partial charges with high-level DFT methods (e.g., ωB97X-D/def2-TZVP). |

| RosettaEnzymes Suite | A specialized set of tools within Rosetta for active site design, including catalytic residue placement and transition state grafting. |

| Stopped-Flow Spectrometer | Instrument for measuring pre-steady-state kinetics (millisecond timescale), crucial for isolating the chemical step from binding events. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column (e.g., Superdex 75) | For final polishing purification of designed enzymes, removing aggregates that can confound kinetic assays. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Probe Substrate | Synthetic substrate that yields a measurable optical signal (fluorescence/absorbance) upon enzymatic turnover; enables high-sensitivity activity screening. |

| Deuterium Oxide (D₂O) | Solvent for kinetic isotope effect (KIE) experiments; a primary experimental probe for verifying a designed proton-transfer mechanism. |

| Thermal Shift Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | For fast, low-consumption thermal denaturation assays to quickly assess the impact of design mutations on protein stability (ΔTm). |

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) & Troubleshooting Guides

Q1: My designed enzyme shows excellent thermostability in differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) but has negligible catalytic activity. What are the primary causes and solutions?

A: This is a classic manifestation of the stability-activity trade-off. Over-stabilization, particularly of the active site region, can rigidify dynamic motions essential for substrate binding, catalysis, and product release.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Analyze Flexibility: Perform molecular dynamics (MD) simulations on your stable variant. Compare backbone and side-chain RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) profiles to a functional natural homolog. Look for regions that have become overly rigid.

- Targeted Loosening: Identify 2-3 key residues in loops or hinges near the active site that contribute to excessive rigidity. Use site-saturation mutagenesis or computational design (e.g., using Rosetta

FlexRelax) to introduce smaller or more flexible amino acids (e.g., Gly, Ala, Ser). - Activity Screening: Employ a high-throughput activity screen (e.g., using a fluorescent or colorimetric substrate) on the new library to identify variants that have regained activity while maintaining sufficient stability.

Q2: During directed evolution for enhanced activity, my enzyme variants keep losing stability and aggregating. How can I maintain a stability baseline?

A: This is the inverse of Q1. Selection pressure for activity alone often selects for destabilizing, flexible mutations.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Dual Selection: Couple your activity screen with a quick stability assay. For example, perform the activity assay both with and without a pre-incubation step at a moderate temperature (e.g., 45°C for 10 minutes). Only variants retaining >70% activity post-incubation are advanced.

- Use Stability-Informed Design: Incorporate computational stability metrics (like

ddGcalculated with Rosetta or FoldX) into your variant filtering process before experimental testing. Prioritize designs predicted to be neutral or stabilizing. - Employ Consensus/Ancestral Design: As a starting scaffold, use a consensus sequence derived from a deep multiple sequence alignment or a computationally inferred ancestral node, which often have higher innate stability than modern proteins.

Q3: What quantitative metrics should I track to formally characterize this trade-off in my enzyme designs?

A: You must collect paired data points for stability and activity. The table below summarizes key metrics:

| Metric Category | Specific Metric | Experimental Protocol Brief | Ideal Instrument/Kit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stability | Melting Temperature (Tm) | DSF Protocol: Dilute protein to 0.2 mg/mL in assay buffer. Add 5X SYPRO Orange dye. Heat from 25°C to 95°C at 1°C/min in a real-time PCR machine. Tm is the inflection point of the fluorescence vs. temperature curve. | Real-time PCR system with FRET channel. |

| Stability | Aggregation Onset (Tagg) | Static Light Scattering (SLS): Monitor scattered light at 350 nm while ramping temperature identically to DSF. Tagg is the temperature where signal increases exponentially. | Fluorometer with temperature-controlled Peltier and multi-wavelength detection. |

| Stability | ΔG of Folding (ΔGf) | Chemical Denaturation: Use Guanidine HCl or Urea. Monitor unfolding via intrinsic fluorescence (Trp) or CD at 222nm. Fit data to a two-state unfolding model to calculate ΔGf in water. | Spectrofluorometer or Circular Dichroism spectropolarimeter. |

| Activity | Turnover Number (kcat) | Initial Rate Kinetics: Perform reactions under saturating [S] >> KM. Plot product formed vs. time (initial linear phase). kcat = Vmax / [Enzyme]. | Plate reader or UV-Vis spectrophotometer. |

| Activity | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) | Determine KM via Michaelis-Menten kinetics across varying [S]. kcat/KM is the second-order rate constant for the enzyme acting on low [S]. | Plate reader or UV-Vis spectrophotometer. |

Q4: Are there computational strategies to design enzymes that balance stability and activity from the outset?

A: Yes, multi-objective optimization is key. Instead of maximizing one property, you search for Pareto-optimal sequences.

- Troubleshooting/Design Protocol:

- Run Pareto Optimization: Use a protein design software suite (e.g., Rosetta's

MPI_christmas_treeorPROSSserver) that allows you to specify both stability (ddG) and catalytic site geometry (constraints,catalytic_tripletscore) as competing objectives. - Generate the Pareto Frontier: The output will be a set of sequences representing the best possible compromises—where you cannot improve activity without losing stability, and vice versa.

- Experimental Validation: Select 3-5 diverse sequences from this frontier for experimental expression and characterization using the metrics in the table above.

- Run Pareto Optimization: Use a protein design software suite (e.g., Rosetta's

Visualizations

Diagram Title: The Iterative Design Cycle for Balancing Stability and Activity

Diagram Title: Pareto Frontier Visualizing Optimal Stability-Activity Compromises

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Stability-Activity Research |

|---|---|

| SYPRO Orange Dye | Environment-sensitive fluorescent dye used in DSF to monitor protein unfolding as a function of temperature, providing Tm. |

| Guandinium HCl (GdnHCl) | Chemical denaturant used in equilibrium unfolding experiments to determine the free energy of folding (ΔGf). |

| His-Tag Purification Resin (Ni-NTA) | For rapid, standardized purification of designed enzyme variants to ensure consistent sample quality for characterization. |

| Fluorogenic/Chromogenic Substrate | Enables high-throughput kinetic screening of enzyme activity in plate reader formats (e.g., para-Nitrophenyl esters for esterases). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Essential for constructing targeted point mutations to test hypotheses about specific residues in the trade-off. |

| Thermostable Polymerase (for PCR) | Critical for gene amplification and library construction during directed evolution cycles. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column | Assesses monodispersity and aggregation state of variants, a direct measure of stability in solution. |

| Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) Plate Reader | Rapidly measures hydrodynamic radius and polydispersity, identifying aggregation-prone variants early in screening. |

Current Limitations of Force Fields and Physical Scoring Functions

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My designed enzyme shows stable folding in silico but aggregates or misfolds in vitro. What are the likely force field culprits and how can I troubleshoot this? A: This is a classic manifestation of limitations in protein force fields, particularly in solvent-solute interactions and long-range electrostatics. The primary culprits are often:

- Inaccurate Solvation Free Energies: Many force fields (e.g., traditional AMBER, CHARMM) have calibrated torsional parameters but less accurate hydration free energies for side chains, leading to incorrect exposure/burial propensity.

- Overly Coarse-Grained van der Waals (vdW) Parameters: vdW terms may not capture delicate packing interactions crucial for native-state stability, favoring collapsed but non-native states.

- Fixed-Charge Models: They cannot model polarization effects, critical for accurately simulating charged active sites or interactions with cofactors.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Solvent Accessibility Analysis: Compare the per-residue solvent-accessible surface area (SASA) of your in silico fold with a structural homolog using

gmx sasa(GROMACS) orVMD. Major discrepancies (>20% for core residues) indicate solvation errors. - Alchemical Free Energy Perturbation (FEP): Perform a short, targeted FEP simulation to compute the solvation free energy of a key suspect side chain (e.g., a buried charged residue) using a more advanced method (explicit solvent with polarizable force field, like AMOEBA) as a benchmark. A discrepancy > 1.5 kcal/mol from the experimental value confirms the issue.

- Parameter Refinement: Use the ForceBalance tool to refit torsional or vdW parameters for the problematic residues against quantum mechanical (QM) energy surfaces and experimental solvation data.

Q2: My scoring function ranks catalytically inactive designs with high geometric complementarity higher than designs with partially optimal but potentially active site geometries. How can I adjust my protocol?

A: This highlights the "energy gap" problem. Physical scoring functions (e.g., Rosetta's ref2015, Talaris) are often dominated by van der Waals packing and hydrogen bonding terms, which favor tight binding over transition-state stabilization.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Decouple Interaction Terms: Decompose your total score into components (e.g.,

fa_atr,fa_rep,hbond_sc,elec). Use Rosetta'sper_residue_energiesor PyRosetta. Designs with excessivefa_rep(clashes) might be inactive, but also check for a lack of stabilizingelecterms in the active site. - Introduce QM-Based Weighting: Re-score your design ensemble using a hybrid score:

Total_Score = w1*Rosetta_Score + w2*QM_Energy. Calculate the QM energy (using DFT with a modest basis set like B3LYP/6-31G*) for only the catalytic residues and substrate pose. Re-rank based on this composite score. Start with weightsw1=0.7, w2=0.3. - Explicit Transition State Stabilization: Instead of the ground state substrate, perform docking and scoring with a transition state (TS) analog. Use the

enzdesmodule in Rosetta with constraints derived from QM calculations on the TS geometry.

Q3: I observe significant conformational drift in my designed enzyme's active site during molecular dynamics (MD) equilibration, ruining pre-catalytic alignment. Is this a sampling or force field issue? A: It is likely both, but force field inaccuracy is a primary driver. Insufficient torsional barriers or incorrect charge distributions can cause loss of critical hydrogen bonds or salt bridges.

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Enhanced Sampling Diagnostics: Run a short (50ns) Gaussian Accelerated Molecular Dynamics (GaMD) simulation to enhance sampling. Use the

cpptrajtool to calculate the root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) of active site residue side-chain dihedrals. Dihedrals with RMSF > 60° are unstable. - QM/MM Validation: Select snapshots where the active site is intact and where it's degraded. Perform QM/MM single-point energy calculations (using ONIOM with QM region = catalytic residues/substrate). If the force field incorrectly predicts the degraded pose to be within 2-3 kcal/mol of the intact pose, it lacks discriminatory power.

- Apply Restraints: Implement backbone

NMR-styledistance and angle restraints on the catalytic geometry derived from your original design for the initial 100-200ns of production MD, gradually releasing them to assess inherent stability.

Table 1: Common Force Fields and Their Documented Limitations in Enzyme Design Contexts

| Force Field | Primary Use Case | Key Limitation (Quantified) | Impact on De Novo Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMBER ff14SB | Protein MD simulations | Under-stabilizes α-helices by ~0.5 kcal/mol/residue vs. expt. May over-stabilize compact states. | Can bias helical bundle designs towards non-native compaction. |

| CHARMM36m | Proteins, membranes, IDPs | Improved torsions over CHARMM22*, but salt bridge distances can be 0.1-0.2Å shorter than QM benchmarks. | May over-stabilize charged clusters, mis-positioning catalytic residues. |

| OPLS-AA/M | Ligand binding, proteins | Hydration free energy errors for certain side chains can exceed 2 kcal/mol. | Incorrect prediction of surface vs. core residue preference. |

| GAFF | Small molecule ligands | Torsional parameter inaccuracies lead to RMSD errors > 30° for drug-like fragments vs. QM. | Poor prediction of substrate or cofactor pose in active site. |

| Rosetta ref2015 | Protein design/scoring | Over-reliance on fa_atr term; weight of elec term may be underestimated. |

Favors tight packing over correct electrostatics for catalysis. |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Scoring Function Components

| Scoring Component | Target for Optimization | Typical Error Margin | Experimental Benchmark Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals Packing | Burial of hydrophobic surface area | ± 0.8 Å in side-chain centroid distances | High-resolution X-ray crystallography (<1.0 Å) |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Distance (2.8Å) and angle (180°) | ± 0.3 Å, ± 40° | Neutron diffraction, NMR J-couplings |

| Solvation (GB/SA) | Transfer free energy of peptides | RMSE of ~1.1 kcal/mol | Calorimetric measurement of unfolding ΔG |

| Electrostatics (PB/GB) | pKa shift of catalytic residues | Average absolute error of 1.5 pKa units | NMR titration, pH-rate profiles |

| Torsional Strain | Side-chain rotamer population | χ1 rotamer population error ~15% | Rotamer libraries from PDB |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Validating Force Field Accuracy for Active Site Geometries via QM/MM Objective: To determine if a classical MD force field maintains a pre-organized catalytic geometry.

- System Preparation: Obtain your designed enzyme model. Parameterize the substrate/TS analog using ANTE-CHAMBER (GAFF2) with HF/6-31G* RESP charges. Solvate the system in a TIP3P water box (10Å padding). Neutralize with ions.

- Equilibration: Perform 2500 steps of steepest descent minimization, followed by 100 ps NVT and 1 ns NPT equilibration using a 2 fs timestep and constraints on heavy atoms of the protein-ligand complex.

- QM/MM Setup: Use

sander(AMBER) orQsite(Schrödinger). Define the QM region to include all residues within 5Å of the substrate and the substrate itself. Use DFT (B3LYP/6-31G*) for the QM region. The MM region uses the standard protein force field. - Sampling & Analysis: Run 10 ns of QM/MM MD. Every 100 ps, extract the snapshot and calculate (a) key catalytic distances (e.g., H-bond donor-acceptor), (b) Mulliken charges on key atoms. Compare the average and fluctuation of these values to a 100 ns classical MD simulation of the same system. A deviation > 2σ indicates force field failure.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Scoring Function Discrimination with Deep Mutational Scanning Data Objective: To evaluate if a scoring function can recapitulate experimental fitness landscapes.

- Data Acquisition: Download a deep mutational scanning (DMS) dataset for a natural enzyme (e.g., from the EMPIRIC database). It should provide fitness scores for single-point mutants.

- Computational Saturation Mutagenesis: Using your design model as a scaffold, generate all 19 single-point mutants at each position in the active site shell (≤8Å from substrate). Generate 50 structural decoys per mutant using backrub sampling (Rosetta

BackrubMover). - Scoring & Correlation: Score each mutant's lowest-energy model and the average of the decoy ensemble. Calculate a ΔΔGscore = Score(mutant) - Score(wild-type). Plot computational ΔΔGscore against experimental log(fitness). Calculate the Pearson correlation coefficient (r) and Spearman's rank (ρ). A robust function should have ρ > 0.5 for active site residues.

Visualizations

Title: Troubleshooting Misfolding in Enzyme Designs

Title: The Scoring Function Energy Gap Problem

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function in Addressing Force Field Limitations |

|---|---|

| ForceBalance Software | Open-source tool for systematic optimization of force field parameters against QM and experimental target data. |

| AMOEBA Force Field | A polarizable force field that models electronic polarization, critical for accurate electrostatics in enzyme active sites. |

| CHARMM Drude Preprocessor | Tool for implementing the polarizable Drude oscillator model into protein-ligand systems. |

Rosetta qs_calc Module |

Enables quantum mechanical (semi-empirical) scoring of protein designs within the Rosetta suite. |

OpenMM AMOEBA Plugin |

Allows for GPU-accelerated MD simulations using the AMOEBA polarizable force field for enhanced sampling. |

GROMACS phbuilder Tool |

Automates constant-pH MD simulation setup to dynamically titrate residues and probe charge state effects. |

| AlphaFold2 Protein Structure DB | Provides high-accuracy structural models for natural homologs, serving as benchmarks for design stability metrics. |

| MolProbity Server | Validates designed structures against geometric constraints (clashscore, rotamer outliers) derived from high-resolution crystal structures. |

Cutting-Edge Methodologies: AI, Generative Models, and High-Throughput Workflows

Leveraging Deep Learning for Protein Structure Prediction (AlphaFold2, RFdiffusion, ESM2)

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: AlphaFold2 Colab notebook fails with a "CUDA out of memory" error. What steps can I take? A: This is common when predicting structures for large protein complexes or long sequences.

- Immediate Action: Reduce the

max_template_dateparameter to limit the number of templates used. For de novo enzyme design, consider predicting individual domains separately. - Protocol Adjustment: Use the AlphaFold2

--db_presetflag set toreduced_dbsfor faster, less memory-intensive predictions during initial screening. - Hardware Solution: The full AlphaFold2 model requires >16GB GPU RAM. For sequences >1,500 residues, use a GPU with 32GB+ RAM (e.g., NVIDIA A100, V100 32GB).

Q2: RFdiffusion generates structures that do not match my intended functional site geometry. How can I improve design precision? A: This indicates inadequate constraint specification.

- Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Verify Inverse Folding: Run ProteinMPNN on the output to check if the designed sequence can refold into the structure.

- Strengthen Constraints: Increase the weight of

contigmap_protocolconstraints (e.g.,contigs,inpaint_seq). Use explicithotspot_resfixation for catalytic residues. - Iterative Refinement: Use the suboptimal output as a seed in a new RFdiffusion run with stricter constraints, employing the

--inference.num_designsflag to generate a larger pool (e.g., 100+) for screening.

Q3: ESM2 embeddings for my enzyme variant show poor correlation with experimental activity. What might be wrong? A: This often stems from misaligned sequences or using the base model without fine-tuning.

- Methodology Check:

- Ensure your multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is correct. Gaps or misalignments corrupt the evolutionary signal.

- The base ESM2 model captures general syntax. For enzyme function, you must fine-tune on a relevant labeled dataset (e.g., thermostability, kcat). Use a simple regression head and train with a small, high-quality dataset.

- Use the

esm2_t36_3B_UR50Dmodel or larger; the 8M parameter model is insufficient for functional prediction.

Q4: When combining these tools for de novo design, my computational pipeline is too slow. How can I optimize it? A: Implement a staged, filtering approach.

- Optimized Workflow Protocol:

- Stage 1 (Rapid Generation): Use RFdiffusion with

--inference.num_designs 50and fast relax only. - Stage 2 (Folding Validation): Run AlphaFold2 (with

reduced_dbs) only on the top 10 designs from Stage 1, selected by ProteinMPNN confidence or simple geometric metrics. - Stage 3 (Function Prediction): Compute ESM2 embeddings (Layer 36) only for designs where the AF2 prediction (pLDDT > 85) matches the RFdiffusion design (TM-score > 0.6).

- Stage 1 (Rapid Generation): Use RFdiffusion with

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: De Novo Active Site Scaffolding with RFdiffusion

- Define Motif: Specify the 3D coordinates and residue identities (e.g., catalytic triad) in a

.pdbfile. - Run Command:

python scripts/run_inference.pyinference.output_prefix=outputinference.input_pdb=input_motif.pdb'contigmap.contigs=[A/100-150/A/10-40/A/100-150]'inference.num_designs=200 - Post-process: Relax all outputs using the Rosetta

fastrelaxprotocol. - Filter: Select designs with ProteinMPNN sequence recovery > 30% and no clashes in the active site.

Protocol 2: Fine-tuning ESM2 for Enzyme Thermostability Prediction

- Prepare Data: Curate a dataset of enzyme variants with labeled melting temperatures (Tm).

- Extract Embeddings: Use the

esm-extracttool to get per-residue embeddings from theesm2_t33_650M_UR50Dmodel. - Pool Features: Apply mean pooling over sequence length to get a fixed-length feature vector per variant.

- Train Model: Add a 2-layer MLP regressor. Train with Mean Squared Error loss, 10-fold cross-validation.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Featured Tools

| Tool | Primary Function | Key Metric (Typical Range) | Computational Cost (GPU hrs/design) | Ideal Use Case in Enzyme Design |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | pLDDT (0-100, >90 high conf.) | 0.5 - 2.0 | Validating de novo designs, predicting wild-type folds. |

| RFdiffusion | Structure Generation | scRMSD to motif (<1.5Å good) | 0.1 - 0.5 | De novo backbone generation around functional motifs. |

| ESM2 | Sequence Representation | Variant Effect Prediction (Spearman ρ) | < 0.01 (inference) | Predicting stability/function from sequence, ranking designs. |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence Design | Sequence Recovery (%) | < 0.05 | Fixing sequences onto RFdiffusion/AlphaFold2 structures. |

Visualizations

Title: De Novo Enzyme Design Workflow

Title: AlphaFold2 Simplified Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools & Resources

| Item | Function/Description | Key Parameter/Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 (ColabFold) | Protein structure prediction from sequence. | Use --template_mode flag to control template bias for de novo designs. |

| RFdiffusion | Conditional protein backbone generation. | contigmap_protocol is critical for defining motif positions and lengths. |

| ESM2 Models | Protein language model for sequence embeddings. | Layer 33 or 36 embeddings are most informative for downstream tasks. |

| ProteinMPNN | Fast, robust inverse folding for sequence design. | --sampling_temp controls sequence diversity (0.1 for low, 0.3 for high). |

| PyRosetta | Macromolecular modeling suite. | Essential for fastrelax and detailed energy evaluations. |

| HH-suite3 | Sensitive MSA generation for AlphaFold2/ESMfold. | Database choice (uniclust30, BFD) affects speed and coverage. |

| PDB (RCSB) | Repository of experimental protein structures. | Source for functional motif templates and benchmarking. |

| ChimeraX | Molecular visualization and analysis. | Used for validating and comparing 3D structural outputs. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Handling Low-Confidence AI-Generated Protein Structures

- Issue: The generated protein backbones exhibit poor stereochemical quality (e.g., high Ramachandran outliers, clashes) despite high model confidence scores.

- Root Cause: This is often due to overfitting in the generative model's training data or the exploration of highly novel, undersampled regions of fold space where physical constraints are poorly learned.

- Steps:

- Filter by MSA Depth: Use the model's internal metric for the depth of the implied multiple sequence alignment (pseudo-MSAs). Discard designs with very low depth.

- Apply Rosetta Relax: Subject all generated structures to an all-atom energy minimization protocol (e.g., FastRelax) with constraints on the backbone to fix local geometry.

- Run in Silico Folding: Use a high-performance protein folding engine (like AlphaFold2 or OpenFold) on the designed sequence. A low pLDDT score (<70) for the core region indicates an unstable fold.

- Iterative Refinement: Use the folding engine's predicted aligned error (PAE) map to identify unstable domains. Return these regions to the generative model for constrained redesign.

Guide 2: Poor Experimental Expression or Solubility of Novel Folds

- Issue: AI-designed proteins express in E. coli but are entirely insoluble or form inclusion bodies.

- Root Cause: The hydrophobic core may be imperfectly packed, or surface electrostatics may promote aggregation. De novo designs lack evolutionary optimization for host machinery.

- Steps:

- Analyze Surface Hydrophobicity: Calculate the hydrophobicity of the designed surface (e.g., using Rosetta's

hpnetscore). Patches of high hydrophobicity are aggregation triggers. - Check Charge Distribution: Ensure a relatively even distribution of positive and negative charges. Use computational tools like PDB2PQR to optimize surface charges near physiological pH.

- Employ Fusion Tags: Use highly soluble fusion tags (e.g., SUMO, Trx, MBP) at the N-terminus and include a cleavage site for tag removal after purification.

- Screen Expression Conditions: Test lower temperature induction (18°C), different E. coli strains (e.g., Shuffle T7 for disulfide bonds, Lemo21(DE3) for tuning expression), and auto-induction media.

- Analyze Surface Hydrophobicity: Calculate the hydrophobicity of the designed surface (e.g., using Rosetta's

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: We are using RFdiffusion for de novo backbone generation. The outputs are diverse, but how do we bias the generation toward a desired functional site geometry (e.g., a catalytic triad)?

A: Use RFdiffusion's conditional inpainting and motif-scaffolding capabilities.

- Prepare the Motif: Define the functional site residues (e.g., Ser-His-Asp) and fix their backbone atom coordinates in a PDB file.

- Set Conditional Generation Parameters: Run diffusion with

contigmap.contigsdefining your fixed motif and the variable scaffold region. Useinpaint_seqto specify which sequence positions are fixed (your motif) and which are designable. - Iterate and Filter: Generate hundreds of scaffolds. Filter using the model's confidence scores (interface scores) and then compute the Rosetta

ddGof binding for your substrate docked into the generated site.

Q2: When using ProteinMPNN for sequence design on a novel fold, the recovered sequences vary wildly in nature. What parameters control sequence diversity and how can we ensure the fold is "designable"?

A: ProteinMPNN offers key temperature and sampling parameters.

temperature: Lower values (e.g., 0.1) produce conservative, low-entropy sequences. Higher values (e.g., 0.3) increase diversity but may reduce fold stability.sampling_argument: Usesample_sequence(notmax_sequence) to explore diversity.- Validation Protocol: Always follow up MPNN sequences with:

- AlphaFold2 Prediction: Fold the sequence de novo. A high pLDDT and strong structural match (TM-score >0.8) to your target backbone validates designability.

- Rosetta Energy Calculations: Calculate the

total_scoreandpackstat(packing statistic) of the designed sequence on the backbone.packstatshould be >0.65 for well-packed cores.

Q3: Our AlphaFold2 models of novel designs show high confidence (pLDDT >85) but experimental circular dichroism (CD) spectra show minimal secondary structure. What's happening?

A: This indicates a potential "hallucination" where the model is overconfident on a non-viable sequence, or the protein is unstructured in vitro.

- Check 1: Predicted Aligned Error (PAE): Examine the PAE matrix. High confidence with a diffuse, high-error PAE (no clear domain structure) is a hallmark of a confident but nonsensical prediction.

- Check 2: In-Context Folding: Run AlphaFold2's multimer mode with a homomer configuration (e.g., dimer). Sometimes de novo designs only stabilize upon oligomerization.

- Action: Experimental Optimization: Re-design using the failed sequence/structure as a negative example in a subsequent training or fine-tuning cycle of your generative model.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Major Generative Protein Design Tools (2023-2024)

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Metric (Success Rate) | Typical Runtime (GPU) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | Backbone Generation | ~10-40% experimental fold accuracy (TM-score >0.7) | 1-5 mins/design | Nature 2023 |

| Chroma | Conditional Generation | ~20% yield of stable, soluble designs | ~30 secs/design | BioRxiv 2023 |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence Design | ~50% recovery of native-like sequences on natural folds | <1 sec/design | Science 2022 |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure Prediction | pLDDT >90 (Very High) correlates with design success | 3-10 mins/seq | Nature 2021 |

| ESMFold | Structure Prediction | Faster inference, good for high-throughput pre-screening | ~1 min/seq | Science 2022 |

Table 2: Experimental Validation Outcomes for *De Novo Designed Enzymes (2020-2024)*

| Study Focus | Design Method | Initial Library Size | Experimental Hit Rate (Soluble/Stable) | Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/KM) vs. Natural | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retro-Aldolase | Rosetta + Iterative AF2 | ~100 designs | ~15% | ~10^3 lower | Substrate positioning |

| Kemp Eliminase | RFdiffusion + MPNN | ~200 designs | ~25% | ~10^4 lower | Pre-organizing active site |

| Hydrolase | Chroma (Conditional) | ~150 designs | ~20% | ~10^5 lower | Transition state stabilization |

Experimental Protocol: Validating a Novel AI-Generated Protein Fold

Objective: To express, purify, and perform biophysical characterization of a de novo generated protein.

Materials:

- E. coli BL21(DE3) or Shuffle T7 cells

- pET series expression vector with N-terminal His-tag

- LB or TB auto-induction media

- Lysis Buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 20 mM Imidazole, 1 mg/mL Lysozyme, protease inhibitor.

- Ni-NTA Agarose resin

- Elution Buffer: 50 mM Tris pH 8.0, 500 mM NaCl, 250 mM Imidazole.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) column (e.g., HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg)

- SEC Buffer: 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl.

- CD spectrometer, Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) instrument.

Methodology:

- Gene Synthesis & Cloning: Codon-optimize the AI-generated sequence for E. coli and synthesize the gene. Clone into expression vector via Gibson assembly.

- Small-Scale Expression Test: Transform 5 E. coli strains. Induce 1 mL cultures at 18°C for 18h. Pellet, lyse with BugBuster, and analyze soluble/insoluble fractions by SDS-PAGE.

- Large-Scale Expression & Purification: Inoculate 1L of auto-induction media with the best strain. Grow at 37°C to OD600 ~0.6, then shift to 18°C for 24h. Pellet cells.

- Immobilized Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC): Resuspend pellet in Lysis Buffer. Sonicate and clarify lysate. Incubate supernatant with Ni-NTA resin for 1h. Wash with 10 column volumes of Lysis Buffer. Elute with Elution Buffer.

- Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC): Concentrate IMAC eluate, inject onto SEC column pre-equilibrated with SEC Buffer. Collect the major symmetric peak. Analyze purity by SDS-PAGE.

- Biophysical Characterization:

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Measure far-UV CD spectrum (190-260 nm). Estimate secondary structure content.

- Thermal Denaturation: Monitor CD signal at 222 nm while ramping temperature (20-95°C). Calculate Tm.

- Analytical SEC: Re-run a sample to confirm monodispersity and rule out aggregation.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: AI-Driven Novel Protein Design and Validation Workflow

Diagram Title: Thesis Context: AI Potential vs. Experimental Hurdles

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Novel Protein Design Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Codon-Optimized Gene Fragments | Ensures high expression yield in the chosen expression host (e.g., E. coli). Avoids rare codons. | Twist Bioscience gBlocks, IDT Gene Fragments. >80% GC content recommended. |

| T7-Compatible Expression Cells | For pET vector systems. Specialty strains improve solubility or disulfide bond formation. | NEB Shuffle T7 (cytoplasmic disulfides), Agilent Rosetta2 (rare tRNAs), Merck Lemo21(DE3) (tuned expression). |

| Affinity Chromatography Resin | One-step purification via engineered tag. Essential for high-throughput screening of multiple designs. | Cytiva HisTrap Excel (Ni-NTA), Thermo Fisher High Capacity Streptavidin Agarose (for Strep-tag). |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) Column | Critical polishing step to isolate monodisperse, correctly folded protein and remove aggregates. | Cytiva HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg (for proteins ~3-70 kDa). |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Buffer Kit | Low-UV transparent buffers are essential for accurate secondary structure measurement. | Hellma Suprasil Quartz cuvettes (0.1 cm path length), 20 mM Potassium Phosphate buffer pH 7.5. |

| Thermal Shift Dye | High-throughput screening of protein stability by monitoring unfolding with temperature. | Thermo Fisher Protein Thermal Shift Dye, Roche SYPRO Orange. Used in qPCR machines. |

| Protease for Tag Removal | Cleaves off solubility/affinity tags to assess the intrinsic stability of the de novo fold. | Human Rhinovirus 3C Protease (PreScission), TEV protease, SUMO proteases. |

Active Site and Transition State Modeling with Quantum Mechanics/Molecular Mechanics (QM/MM)

1. Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My QM/MM simulation of an enzyme's catalytic step results in an unrealistic energy barrier (too high or too low). What are the primary causes? A: This is often due to an inadequate QM region or an incorrect protonation state.

- Check 1: Ensure your QM region includes all residues and cofactors directly involved in bond-breaking/forming, as well as any within ~4-5 Å that can electrostatically influence the event. Expanding the QM region by 1-2 key residues often corrects aberrant barriers.

- Check 2: Verify the protonation states of all titratable residues (especially in the active site) at your simulation's pH using a tool like PROPKA, followed by manual inspection for hydrogen-bonding networks.

- Check 3: Confirm the initial geometry of your modeled transition state (TS) is reasonable. Perform a relaxed potential energy surface scan along the reaction coordinate to locate the TS region before attempting refinement.

Q2: During QM/MM geometry optimization, the system diverges or the active site structure becomes distorted. How can I stabilize the optimization? A: This indicates instability at the QM/MM boundary or conflicting forces.

- Solution: Use a more robust optimization algorithm and stepwise protocol. First, heavily restrain the protein backbone and QM/MM linker atoms, optimizing only the QM region and key side chains. Then, gradually release these restraints in subsequent optimization stages. Ensure your MM force field parameters for the QM/MM boundary (link atoms, capping hydrogens) are applied consistently.

Q3: How do I choose between additive and subtractive QM/MM schemes (e.g., ONIOM vs. Electrostatic Embedding) for modeling enzymatic reactions? A: The choice depends on the role of long-range protein electrostatics.

| Scheme | Method | Best For | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subtractive (ONIOM) | QM energy + (MM full - MM model) | Reactions where the environment's effect is predominantly steric or short-range. Computationally efficient. | Neglects polarization of the QM region by the MM environment's electric field. |

| Electrostatic Embedding (Additive) | QM Hamiltonian includes MM point charges. | Most enzymatic reactions, where the protein's electrostatic field stabilizes charges in the TS. Essential for proton transfer. | Risk of "overpolarization" if MM charges are too close to the QM region; requires careful treatment of the boundary. |

Q4: My calculated reaction energy profile disagrees with experimental kinetics data. What systematic validations should I perform? A: Follow this validation workflow:

Title: QM/MM Energy Profile Validation Workflow

2. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Setting Up a QM/MM Simulation for a Hydrolysis Reaction

- Step 1 – System Preparation: Obtain an enzyme structure (PDB). Use molecular dynamics (MD) software (e.g., AMBER, GROMACS) to add missing residues, solvate the system in a water box, and add ions to neutralize. Perform MM minimization and equilibration.

- Step 2 – QM Region Selection: Select all substrate atoms, catalytic residues (e.g., Asp, His, Ser for hydrolases), metal ions if present, and key water molecules. Define covalent boundaries with link atoms (typically hydrogen).

- Step 3 – QM/MM Calculation Setup: In a package like CP2K, ORCA, or Gaussian/AMBER, specify: QM method (e.g., DFT with B3LYP/6-31G), MM force field (e.g., CHARMM36), electrostatic embedding, and the total charge/multiplicity of the QM region.

- Step 4 – Reaction Path Mapping: Generate initial structures for reactant, product, and guessed TS. Use QM/MM constrained optimizations or potential energy surface scans along a defined reaction coordinate (e.g., breaking bond distance). Refine the TS using QM/MM nudged elastic band or transition state optimization algorithms.

Protocol 2: Calculating the Activation Energy (ΔG‡)

- Step 1 – Geometry Optimization: Fully optimize the reactant complex (RC) and transition state (TS) using QM/MM. Verify the TS has one imaginary frequency corresponding to the reaction coordinate.

- Step 2 – Frequency Calculations: Perform QM/MM frequency calculations on the RC and TS in the internal coordinates of the QM region. This yields the zero-point energy and thermodynamic corrections.

- Step 3 – Free Energy Perturbation (Optional): For higher accuracy, use QM/MM free energy perturbation or umbrella sampling to account for entropic contributions and dynamic fluctuations not captured in a single optimized structure.

- Step 4 – Energy Calculation: The electronic activation energy is ΔE‡ = E(QM/MM, TS) - E(QM/MM, RC). Add thermodynamic corrections to obtain ΔG‡.

3. The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Software | Function in QM/MM Modeling | Example/Tool |

|---|---|---|

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Runs computationally intensive QM calculations. Essential for >500 atom QM regions or dynamics. | Local cluster, cloud-based HPC (AWS, Azure). |

| QM Software | Performs the quantum mechanical energy and force calculations. | CP2K, ORCA, Gaussian, TeraChem. |

| MM/MD Software | Handles system setup, classical dynamics, and integrates QM/MM calls. | AMBER, GROMACS, CHARMM, NAMD. |

| Integrated QM/MM Packages | Streamlined environment for combined calculations. | Q-Chem/CHARMM, AMBER/TeraChem. |

| Visualization & Analysis | Visualizes structures, reaction paths, and analyzes trajectories. | VMD, PyMOL, Jupyter Notebooks with MDAnalysis. |

| Force Field Parameters for Non-Standard Residues | Provides MM parameters for novel substrates, cofactors, or intermediates. | CGenFF, ACPYPE, antechamber. |

| pKa Prediction Tool | Estimates protonation states of residues for system preparation. | PROPKA, H++. |

| Transition State Guess Generator | Helps create an initial TS structure from RC and PC. | AFIR, ESOpt. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: My designed enzyme shows no detectable activity in the wet-lab assay. What are the primary computational checks?

- A: First, verify the catalytic residue geometry in your designed model using the

rosetta_scriptsapplication with theCatalyticTriadAngleandDistancefilters. Angles should be within 20° and distances within 0.5 Å of the target values from the catalytic motif specification. Second, runFastRelaxwith a high constraint weight (-coord_cst_weight 10) to see if the active site collapses without constraints, indicating a poorly packed design. Third, use theInterfaceAnalyzermover to ensure your substrate binding interface has favorable dG_separated (typically < -5.0 REU) and a buried surface area (> 800 Ų).

- A: First, verify the catalytic residue geometry in your designed model using the

Q2: The RosettaEnzyDesign protocol is producing sequences with excessive charged residues (D/E/K/R) in the active site, leading to aggregation. How can I bias against this?

- A: This is a known issue in the

EnzDesMonte Carlo sequence design phase. Modify the.resfileor the RosettaScripts XML to use theLayerDesignmover in conjunction withEnzDes. Constrain the core and boundary layers to have a maximum net charge. Alternatively, use theaa_compositionframework to add aNetChargeConstraint(e.g.,max_net_charge 1) specifically to the designable residues in the active site pocket.

- A: This is a known issue in the

Q3: When using the FuzzyLogicTaskOperation for multi-state design, my results are inconsistent between runs. What could be wrong?

- A: FuzzyLogic requires careful setup. 1) Ensure all input structures for the different states (e.g., apo, holo, transition state) are pre-aligned to a common reference frame. 2) Check that the residue selectors (

<ResidueSelectors>) for each state are correctly identifying the equivalent positions across all input PDBs. A mismatch here causes undefined behavior. 3) Verify the logical expression in theFuzzyLogictag uses the correct state names and Boolean operators. Use the-run:show_simulation_informationflag for verbose output on state assignments.

- A: FuzzyLogic requires careful setup. 1) Ensure all input structures for the different states (e.g., apo, holo, transition state) are pre-aligned to a common reference frame. 2) Check that the residue selectors (

Q4: Performance bottlenecks with the newer deep learning-based sequence scoring functions (e.g., ProteinMPNN, ESM-IF1). How to integrate them efficiently?

- A: Direct on-the-fly scoring is computationally prohibitive. The recommended protocol is a two-stage funnel:

- Stage 1 (Rosetta-Only): Generate a large decoy set (10,000-50,000) using traditional Rosetta enzyme design with relaxed energy functions (

beta_nov16_cart). - Stage 2 (DL Filtering): Extract the unique sequences from the decoy set. Use an external script (e.g., with PyRosetta or the standalone ProteinMPNN) to score these sequences in the context of the fixed backbone. Filter and rank based on the DL model's log-likelihood scores.

- Stage 1 (Rosetta-Only): Generate a large decoy set (10,000-50,000) using traditional Rosetta enzyme design with relaxed energy functions (

- See the workflow diagram "Hybrid Rosetta-DL Enzyme Design Funnel" below.

- A: Direct on-the-fly scoring is computationally prohibitive. The recommended protocol is a two-stage funnel:

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard RosettaEnzyDesign Workflow for De Novo Catalytic Site Installation.

- Step 1 – Preparation: Obtain a scaffold protein PDB. Define the catalytic residues and constraints using a

.cstfile. Example constraint for a nucleophile (distance & angle): - Step 2 – Motif Graffing: Use the

EnzGraftmover to sample placements of the catalytic motif onto the scaffold. - Step 3 – Sequence Design: Run the

EnzDesprotocol in RosettaScripts, which performs coupled side-chain packing, minimization, and sequence design under the defined constraints. Use-ex1 -ex2and a high-extrachi_cutoff. - Step 4 – Refinement & Filtering: Subject the top 1000 models by total score to

FastRelaxwith constraints. Filter using theConstraintScore(should be < 1.0 REU) andpackstat(should be > 0.6). - Step 5 – In-silico Affinity Assessment: Dock the native substrate into the designed active site using

RosettaLigandorFlexPepDockand calculate the binding energy (dG_separated).

- Step 1 – Preparation: Obtain a scaffold protein PDB. Define the catalytic residues and constraints using a

Protocol 2: Integrating ProteinMPNN for Sequence Optimization.

- Step 1 – Generate Backbone Ensemble: Create 1000-5000 designed backbones using Protocol 1, Steps 1-3, but with a minimal alphabet (e.g., ALA, VAL, ILE, LEU) to fix backbone conformation.

- Step 2 – Extract Fixed Backbones & Positions: Prepare a list of PDBs and a corresponding mask file indicating which residues are fixed (0) and which are designable (1).

Step 3 – Run ProteinMPNN: Execute ProteinMPNN in deterministic mode to generate 8 sequences per backbone.

Step 4 – Rosetta Refinement & Selection: Fold the ProteinMPNN-generated sequences back onto their parent backbones using

FastRelax, then select based on Rosetta energy and constraint satisfaction.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Recent Algorithmic Modules in Rosetta Enzyme Design

| Algorithm/Module | Primary Function | Key Metric Improved | Typical Performance Gain/Output | Common Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EnzDes (Classic) | Coupled backbone/sequence design with constraints. | Catalytic geometry accuracy. | 60-80% of designs pass geometric filters in silico. | Installing known catalytic motifs into scaffolds. |

| FuzzyLogic | Multi-state aware sequence design. | Functional specificity, stability. | Can increase sequence selection for holo-state by 2-5x over single-state. | Designing for conformational selection or preventing unwanted binding. |

| ProteinMPNN | Deep learning-based sequence generation. | Native-likeness, foldability. | >90% expressed solubly vs. ~70% with Rosetta-alone; ~5-10°C higher Tm on average. | Final sequence optimization after active site design. |

| ESM-IF1 | Inverse folding for scaffold mining. | Scaffold novelty & compatibility. | Can identify non-homologous scaffolds (<20% ID) for motifs in databases. | Finding new protein folds to host a desired active site. |

Visualizations

Hybrid Rosetta-DL Enzyme Design Funnel

Fuzzy Logic Multi-State Design Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Rosetta Enzyme Design & Validation

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | Core modeling & design platform. | Source from https://www.rosettacommons.org. Requires compilation. "Enzyme Design" (enzdes) and "RosettaScripts" are critical modules. |

| PyRosetta | Python interface to Rosetta. | Enables custom scripting and pipeline integration with DL tools. Educational license available. |

| ProteinMPNN | Deep learning for sequence design. | GitHub: /dauparas/ProteinMPNN. Used for final sequence optimization on fixed backbones. |

| AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold | Structure prediction validation. | Run designed sequences through AF2 to check for backbone conformational drift from the design model. |

| Transition State Analog (TSA) | Defining geometric constraints. | Critical experimental reagent. Its crystal structure or modeled coordinates are used to generate the catalytic constraint (.cst) file. |

| High-Throughput Cloning Kit | Wet-lab validation. | e.g., Gibson Assembly or Golden Gate kits for rapid library construction of designed variants. |

| Thermofluor (DSF) Assay Kit | Stability screening. | e.g., SYPRO Orange dye. Initial high-throughput check for properly folded designs. |

| Continuous Enzymatic Assay Substrate | Activity measurement. | Fluorogenic or chromogenic substrate specific to the target reaction (e.g., 4-Nitrophenyl acetate for esterases). |

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers implementing the integrated Build and Test cycle within a de novo enzyme design project, addressing common experimental challenges.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Q1: After computational design, my initial purified enzyme shows no detectable activity in the standard assay. What are the first steps to diagnose this? A: This is a common entry point for directed evolution. Follow this diagnostic cascade:

- Verify Protein Expression & Solubility: Run an SDS-PAGE gel of both the whole cell lysate and soluble fraction. No band may indicate expression failure.

- Confirm Proper Folding: Perform circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy and compare the spectrum to the computationally predicted secondary structure.

- Check Assay Conditions: Ensure the assay pH, temperature, and buffer components are compatible with your designed active site (e.g., metal cofactor requirement).

- Proceed to Saturation Mutagenesis: If the protein is soluble and folded, target the top 5-10 active site residues for low-stringency saturation mutagenesis (e.g., using NNK codon libraries) to introduce functional diversity.

Q2: My designed enzyme has low activity. During directed evolution, library diversity after selection is extremely low, indicating a fitness bottleneck. How can I overcome this? A: This suggests your selection pressure is too high, killing all variants. Implement a tiered screening approach:

- Primary Screen: Use a low-stringency, high-throughput survival or colorimetric screen (e.g., on agar plates) to isolate a pool of functional variants.

- Secondary Screen: Use a medium-throughput kinetic assay (e.g., in 96-well plates) of the primary hits to rank them by activity.

- Tertiary Validation: Purify top variants from secondary screen for detailed kinetic characterization. Adjust your primary screen to allow ~0.1-1% of the library to survive.

Q3: I am using machine learning models to predict beneficial mutations, but iterative cycles are not improving activity beyond a low plateau. What might be wrong? A: The training data for your model is likely inadequate.

- Action: Generate a more diverse training set by incorporating "negative" data (variants with worse activity) and sequence-function data from intermediate rounds, not just final best hits.

- Protocol: Create a focused combinatorial library based on the top 20 predicted single mutants. Use a Golden Gate or USER assembly strategy to build the library, ensuring even coverage. Screen this library to generate a robust dataset for model retraining.

Q4: How do I balance exploration (broad mutagenesis) and exploitation (fine-tuning) during the directed evolution phases? A: Structure your Build and Test cycles with defined goals, as summarized in the table below.

| Cycle Phase | Computational Design Focus | Directed Evolution Strategy | Typical Library Size | Goal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1: Scaffold Exploration | Generate diverse backbone scaffolds (e.g., using RFdiffusion). | Error-Prone PCR (low mutation rate, ~1-3 mutations/kb) on entire gene. | 10^6 - 10^8 | Identify any functional scaffold from design pool. |

| Cycle 2: Active Site Optimization | Identify hot-spot residues for mutagenesis from MD simulations. | Saturation Mutagenesis (NNK) at 3-5 predicted key positions. | 10^4 - 10^5 | Establish a baseline active enzyme (kcat/KM > 1 M⁻¹s⁻¹). |

| Cycle 3: Functional Fine-Tuning | Predict beneficial combinations (e.g., using Pytorch-based models). | Combinatorial Library of 5-7 beneficial single mutants. | 10^5 - 10^6 | Improve efficiency (kcat/KM > 10^3 M⁻¹s⁻¹). |

| Cycle N: Stability & Robustness | Identify stabilizing mutations (ΔΔG calculation). | Site-directed mutagenesis or focused library at non-active site positions. | 10^2 - 10^3 | Enhance thermostability (Tm increase > 10°C). |

Q5: My evolved enzyme is highly active but aggregates during purification at high concentration. How can I fix this without losing activity? A: This is a stability issue. Introduce a stability screening step post-activity selection.

- Protocol: Thermostability Pre-screening. After selecting active variants from a library, subject the cell lysates to a mild heat challenge (e.g., 50°C for 10 minutes). Centrifuge to pellet aggregated protein. Use the supernatant in your activity assay. This co-selects for soluble, stable variants.

- Computational Redesign: Use tools like Rosetta ddg_monomer to predict stabilizing mutations on the surface of your best active variant. Construct a small library targeting these positions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Build & Test Cycle |

|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Oligonucleotides | Encodes all 20 amino acids with only one stop codon (TAG) for efficient saturation mutagenesis. |

| Golden Gate Assembly Mix | Enables seamless, scarless assembly of multiple DNA fragments for combinatorial library construction. |

| Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Used for accurate gene amplification during library construction and variant QC. |

| Error-Prone PCR Kit (with adjusted Mn2+) | Generates random mutations across the gene for initial exploration rounds. Mn2+ concentration modulates mutation rate. |

| HisTrap HP Column | Standardized purification of His-tagged designed/evolved enzymes for kinetic assays. |

| Thermofluor Dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) | High-throughput measurement of protein melting temperature (Tm) for stability screening. |

| Chromogenic/ Fluorogenic Substrate Analog | Enables direct high-throughput screening of enzyme activity in colonies or lysates. |

Experimental Workflow & Protocol Diagrams

Title: The Iterative Build and Test Cycle Workflow

Title: Diagnostic Flow for Inactive Designed Enzymes

From In Silico to In Vitro: Debugging and Enhancing Designed Enzymes

Diagnosing and Remedying Poor Expression and Solubility

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Q1: My designed enzyme expresses predominantly in inclusion bodies. What are the primary factors to check first?

A: The shift from soluble protein to inclusion bodies is often due to intracellular aggregation caused by rapid protein folding kinetics in a non-native environment. Key factors to check are:

- Expression Temperature: High temperatures (e.g., 37°C) accelerate transcription/translation but can overwhelm folding chaperones. Lowering to 18-25°C is often the first and most effective remedy.

- Inducer Concentration: Over-expression from high IPTG concentrations (e.g., >0.5 mM) floods the cell. Use lower concentrations (0.01-0.1 mM) or auto-induction media.

- Sequence Analysis: Check for rare codons (especially at the N-terminus) that can cause ribosomal stalling, and look for patches of hydrophobic surface or low-complexity regions that promote aggregation.

Q2: What are the most effective in silico tools to predict solubility before I even begin cloning?

A: Several tools use machine learning trained on experimental datasets. Use a consensus approach from the following:

| Tool Name | Basis of Prediction | Typical Output Metric | Reference/Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| PROSO II | Protein sequence features | Probability of being soluble | (PubMed: 21936953) |

| CamSol | Physicochemical properties & intrinsic solubility profile | Intrinsic solubility score & designed variant suggestions | (PubMed: 25475831) |

| DeepSol | Deep learning on one-hot encoded sequences | Binary classification (Soluble/Insoluble) | (PubMed: 31504629) |

| AGGRESCAN | Inherent aggregation-prone regions | "Hot spot" map & aggregation propensity score | (PubMed: 18045434) |

Q3: I have an insoluble protein. What are my primary options for rescuing it, and in what order should I attempt them?

A: Follow a logical, tiered experimental workflow:

- Modify Expression Conditions: Lower temperature & inducer concentration; use a richer growth medium; try different E. coli strains (e.g., origami for disulfides, rosetta for rare codons).

- Use Fusion Tags: Fuse protein to highly soluble partners (e.g., MBP, GST, SUMO, NusA) at the N-terminus. This often improves solubility and can aid purification.

- Co-express with Chaperones: Use plasmids encoding GroEL/ES or DnaK/DnaJ/GrpE chaperone systems to assist folding.

- Refold from Inclusion Bodies: Isolate inclusion bodies, denature with 6-8 M Urea/Guanidine-HCl, and refold by gradual dilution or dialysis.

- Redesign via Mutagenesis: Use computational tools (like CamSol) to identify and mutate aggregation-prone regions, often by surface entropy reduction or introducing solubilizing point mutations.

Q4: What is a standard protocol for testing expression and solubility in small-scale?

A:

- Culture: Inoculate 5 mL cultures of your expression strain. Include an empty vector control.

- Induce: Grow to mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8), induce with optimized IPTG concentration.

- Express: Incubate post-induction at your test temperature (e.g., 18°C) for 16-20 hours.

- Harvest: Pellet 1 mL of culture. Resuspend pellet in 100 µL of Lysis Buffer (e.g., PBS with 1 mg/mL lysozyme, benzonase, and protease inhibitors).

- Lyse: Use sonication or freeze-thaw cycles.

- Fractionate: Centrifuge at >15,000 x g for 20 min. Carefully separate the supernatant (soluble fraction). Resuspend the pellet (insoluble fraction) in 100 µL of Lysis Buffer + 1% SDS.

- Analyze: Run equal proportions of total lysate, supernatant, and pellet fractions on SDS-PAGE.

Q5: Are there specific fusion tags recommended for difficult-to-express enzymes in de novo design?

A: Yes. The choice can impact the enzyme's activity.

- MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein): Often the first choice. It is highly soluble, can improve folding, and is purified via amylose resin. A TEV or Factor Xa cleavage site allows removal.

- SUMO (Small Ubiquitin-like Modifier): Very soluble and has the advantage of being cleavable by highly specific SUMO proteases, often leaving no residual amino acids.

- Trx (Thioredoxin): Helps with proteins prone to disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm.

- NusA: A large, very soluble tag that can significantly enhance solubility.

- Strategy: Clone your target gene into a vector with multiple tags in a polycistronic format (e.g., pET MBP/SUMO vectors) to test which works best.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Solubility/Expression Work |

|---|---|

| E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS | Expression host; T7 RNA polymerase under lacUV5 control; pLysS provides low-level T7 lysozyme to suppress basal expression. |

| E. coli SHuffle T7 | Expression host engineered for disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm, crucial for some designed enzymes. |

| Autoinduction Media (e.g., Overnight Express) | Allows high-density growth before induction via lactose, minimizing user handling and often improving solubility. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (e.g., PMSF, EDTA-free) | Prevents proteolytic degradation of expressed protein during lysis and purification. |

| Lysozyme & Benzonase Nuclease | Enzymatic lysis of bacterial cells and degradation of genomic DNA to reduce viscosity. |

| Detergents (e.g., CHAPS, Triton X-114) | Added to lysis buffers (typically 1%) to mildly solubilize membrane-associated aggregates. |

| Urea & Guanidine Hydrochloride | Chaotropic agents for denaturing and solubilizing proteins from inclusion bodies. |

| ArcticExpress (DE3) Competent Cells | Co-express chaperonin Cpn60 from a psychrophilic bacterium, aiding folding of complex proteins at low temps. |

Experimental & Diagnostic Workflows

Workflow for Remedying Poor Solubility

Diagnostic Solubility Fractionation Flow

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: Why is the catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km) of my designed enzyme significantly lower than predicted despite good active site geometry?

- Likely Cause: Poor substrate access to the active site due to inefficient dynamics or gating. The designed scaffold may be too rigid, preventing necessary conformational changes for substrate binding or product release.

- Solution: Implement molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze tunnels and gatekeeper residues. Consider introducing flexibility via directed evolution or rational design focusing on loop regions near the active site entrance.

FAQ 2: During directed evolution for higher kcat, my variants show improved activity but also dramatically increased Km. What is happening and how can I fix it?

- Likely Cause: Mutations are optimizing chemical steps (increasing kcat) but compromising substrate binding, often by distorting the optimal pre-catalytic pose or blocking access. This decouples the parameters.

- Solution: Screen or select under conditions of low substrate concentration to maintain selection pressure on Km. Use computational double-mutant cycles to find mutations that improve transition state stabilization without harming binding.

FAQ 3: How can I experimentally probe if slow conformational dynamics are rate-limiting my enzyme's kcat?

- Likely Cause: The rate-limiting step is not the chemical transformation but a physical rearrangement of the enzyme (e.g., loop closure, hinge motion).

- Solution: Employ stopped-flow fluorescence with environmentally sensitive probes or tryptophan mutants positioned at dynamic regions. Monitor pre-steady-state bursts. Also, measure reaction rates across a temperature range (Arrhenius plot) to identify a breakpoint indicative of a change in the rate-limiting step.

FAQ 4: My designed enzyme has a buried active site with no clear substrate tunnel. What strategies can create an access pathway?

- Likely Cause: De novo designs often produce overly packed cores. Natural enzymes use defined substrate access tunnels.