Directed Evolution in Enzyme Engineering: Methodologies, Applications, and AI-Driven Future

Directed evolution stands as a cornerstone of modern protein engineering, enabling the rapid development of tailored biocatalysts without requiring exhaustive prior knowledge of protein structure.

Directed Evolution in Enzyme Engineering: Methodologies, Applications, and AI-Driven Future

Abstract

Directed evolution stands as a cornerstone of modern protein engineering, enabling the rapid development of tailored biocatalysts without requiring exhaustive prior knowledge of protein structure. This article provides a comprehensive overview for researchers and drug development professionals, covering the foundational principles of directed evolution and its powerful imitation of natural selection. It delves into contemporary methodologies, from classical error-prone PCR to advanced continuous evolution systems like MutaT7 and PACE, highlighting their applications in creating enzymes with enhanced stability, specificity, and novel functions. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects and optimization strategies, including the integration of machine learning and high-throughput screening to navigate complex fitness landscapes. Finally, it examines validation techniques and comparative analyses of different platforms, offering a synthesized perspective on future directions where automation and computational design are poised to revolutionize biocatalyst development for biomedical and industrial applications.

The Principles and Power of Directed Evolution: Harnessing Natural Selection in the Laboratory

Directed evolution is a powerful protein engineering tool that mimics the process of natural evolution in a controlled laboratory setting to optimize biomolecules for human-defined applications. Since the first in vitro evolution experiments by Sol Spiegelman in the 1960s, the methodology has developed into a sophisticated approach for generating enzymes, antibodies, and other proteins with improved or novel functions [1]. This process operates on the fundamental principle of exploring protein fitness landscapes—conceptual mappings of amino acid sequences to functional efficacy—to identify variants with enhanced properties [2] [3]. For researchers in enzyme engineering and drug development, directed evolution provides a practical pathway to optimize complex phenotypes without requiring complete understanding of underlying sequence-structure-function relationships.

Core Principles and Methodological Framework

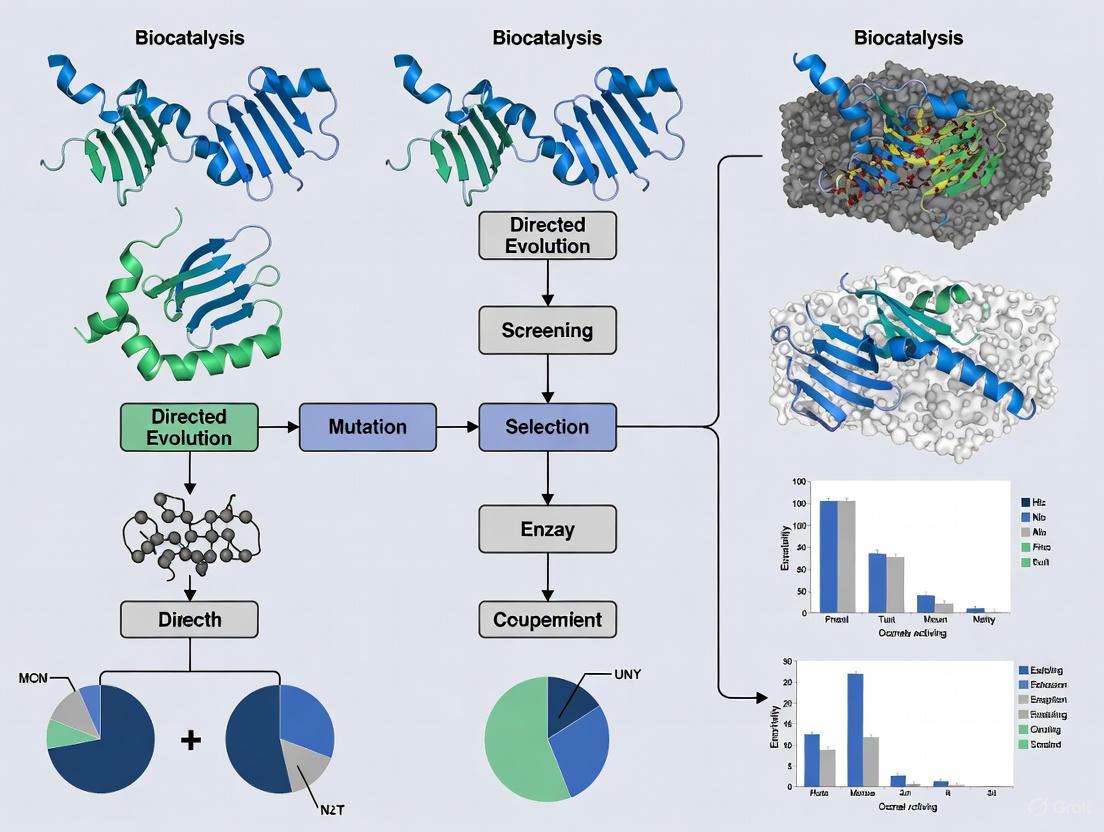

The directed evolution workflow consists of two complementary steps repeated iteratively: genetic diversification (creating a library of variants) and phenotype selection or screening (identifying improved variants) [1]. This process can be conceptualized as an adaptive walk across a protein fitness landscape, where each cycle of mutation and selection moves the population toward higher fitness peaks [3].

The Directed Evolution Cycle

The fundamental steps include:

- Library Generation: Introducing genetic diversity into a parent sequence

- Expression: Producing the encoded protein variants

- Screening/Selection: Assessing function to isolate improved variants

- Amplification: Using improved variants as templates for subsequent cycles

This iterative process continues until the desired functionality is achieved, allowing researchers to accumulate beneficial mutations while filtering out deleterious changes.

Key Techniques and Methodologies

Genetic Diversification Strategies

Multiple molecular biology techniques exist for creating genetic diversity, each with distinct advantages and applications:

Table 1: Genetic Diversification Techniques in Directed Evolution

| Technique | Purpose | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-prone PCR | Insertion of point mutations across whole sequence | Easy to perform; No prior knowledge of key positions required | Reduced sampling of mutagenesis space; Mutagenesis bias | Subtilisin E; Glycolyl-CoA carboxylase [1] |

| DNA Shuffling | Random sequence recombination | Recombination advantages; Can combine beneficial mutations | High homology between parental sequences required | Thymidine kinase; Non-canonical esterase [1] |

| RAISE | Insertion of random short insertions and deletions | Enables random indels across sequence | Indels limited to few nucleotides; Frameshifts introduced | β-Lactamase [1] |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Focused mutagenesis of specific positions | In-depth exploration of chosen positions; Enables smart library design | Only a few positions mutated; Libraries can become very large | Widely applied to enzyme evolution [1] |

| Orthogonal Replication Systems | In vivo random mutagenesis | Mutagenesis restricted to target sequence | Mutation frequency relatively low; Target size limitations | β-Lactamase; Dihydrofolate reductase [1] |

| TRINS | Insertion of random tandem repeats | Mimics duplications in natural evolution | Frameshifts introduced | β-Lactamase [1] |

Screening and Selection Platforms

Identifying improved variants from libraries requires robust screening or selection methods:

Table 2: Screening and Selection Methods in Directed Evolution

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colorimetric/Fluorimetric Analysis | Detection of spectral changes in colonies/cultures | Moderate | Variants with altered spectral properties; Fluorescent proteins [1] |

| FACS-Based Methods | Fluorescence-activated cell sorting | High throughput | Properties linked to fluorescence changes; Sortase; Cre recombinase [1] |

| Display Techniques (Phage, Yeast) | Physical linkage of genotype to phenotype | High throughput | Biomolecules with binding properties; Antibodies; Binding proteins [1] |

| Plate-Based Automated Assays | Automated enzymatic activity measurements | Moderate | Broad enzyme applications; Lipase; Laccase [1] |

| MS-Based Methods | Mass spectrometric detection of substrates/products | High throughput | Does not rely on specific properties; Fatty acid synthase; Cytochrome P411 [1] |

| QUEST | Substrate/ligand-based selection | High throughput | Scytalone dehydratase; Arabinose isomerase [1] |

Advanced Methodologies and Recent Innovations

Machine Learning-Enhanced Directed Evolution

Traditional directed evolution faces limitations from epistasis (non-additive effects of mutations), which can trap experiments at local fitness optima. Active Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) addresses this challenge by integrating machine learning with experimental workflows [2]. ALDE employs iterative cycles of data collection, model training, and variant prioritization using uncertainty quantification to navigate complex fitness landscapes more efficiently than greedy hill-climbing approaches. In one application, ALDE optimized five epistatic residues in a protoglobin active site for a non-native cyclopropanation reaction, improving product yield from 12% to 93% in just three rounds while exploring only ~0.01% of the design space [2].

Continuous Evolution Systems

Recent advances have enabled continuous directed evolution platforms that operate without discrete rounds of mutagenesis and selection. The OrthoRep system in yeast and PACE (Phage-Assisted Continuous Evolution) in bacteria allow for continuous protein evolution under constant selection pressure [4]. These systems utilize orthogonal DNA polymerases with elevated error rates or mutagenesis plasmids tunably expressed via chemical inducers to achieve hypermutation of target genes [5] [4].

Inducible Directed Evolution (IDE) for Complex Phenotypes

Inducible Directed Evolution (IDE) enables evolution of large DNA sequences (up to 85kb) by combining an intracellular mutagenesis plasmid with P1 phage transfer [5]. The mutagenesis plasmid contains a tunable operon (danQ926, dam, seqA, emrR, ugi, and cda1) that, when induced, represses DNA repair mechanisms, leading to higher mutation rates specifically in the pathway of interest [5].

Automated and Autonomous Laboratories

The integration of robotics and artificial intelligence has enabled the development of fully automated laboratories for programmable protein evolution. The iAutoEvoLab platform combines automated liquid handling, high-throughput screening, and machine learning-guided experimental design to enable continuous, scalable protein evolution with minimal human intervention [4]. Such systems can operate autonomously for extended periods (approximately one month) and have successfully evolved functional proteins from inactive precursors, including a T7 RNA polymerase fusion protein with mRNA capping properties [4].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Active Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (ALDE) Protocol

Application: Optimizing epistatic residues in enzyme active sites where traditional directed evolution fails due to rugged fitness landscapes [2].

Materials:

- Parental gene or plasmid

- PCR reagents for site-saturation mutagenesis

- Expression system (e.g., E. coli)

- Activity assay reagents

- Computational resources for machine learning

Procedure:

Define Combinatorial Design Space: Select k residues for simultaneous mutagenesis (20^k possible variants).

Initial Library Construction and Screening:

- Perform simultaneous mutagenesis at all k positions using NNK degenerate codons

- Screen an initial random library (typically hundreds of variants)

- Quantitatively measure fitness for each screened variant

Machine Learning Iteration Cycle:

- Train a supervised ML model on collected sequence-fitness data

- Apply acquisition function to rank all sequences in design space

- Select top N variants for subsequent experimental screening

- Repeat for multiple rounds (typically 3-5 cycles)

Validation: Characterize top-performing variants in detail

Technical Notes: Choice of protein sequence encoding, model type, and acquisition function significantly impacts ALDE performance. Frequentist uncertainty quantification often outperforms Bayesian approaches in high-dimensional settings [2].

Inducible Directed Evolution (IDE) Protocol for Large Pathways

Application: Evolving complex phenotypes encoded by multigene pathways (up to 85kb) while avoiding genomic hitchhiker mutations [5].

Materials:

- P1 phagemid (PM) backbone

- Mutagenesis plasmid (MP) with mutagenic operon

- E. coli diversification strain

- Chemical inducers (e.g., anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride)

- LB broth with appropriate antibiotics

- Electroporation equipment

Procedure:

Phagemid Construction:

- Clone pathway of interest into P1 phagemid backbone

- Transform into diversification strain containing MP

Mutagenesis Induction:

- Grow diversification strain to mid-log phase

- Add chemical inducer to express mutagenic operon

- Incubate for desired mutation rate (typically 1-3 days)

Phage Production and Infection:

- Induce P1 lytic cycle to package mutagenized phagemid

- Harvest phage particles by filtration and chloroform treatment

- Infect fresh screening/selection strain with phage lysate

Screening and Selection:

- Plate infected cells and screen for improved phenotypes

- Israte improved variants for characterization or further cycles

Technical Notes: IDE decouples mutagenesis from screening, avoids inefficient transformation steps, and prevents off-target genomic mutations. The mutation rate can be tuned by inducer concentration and induction time [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Mutagenesis Plasmids | Enable targeted hypermutation | OrthoRep systems; IDE MP with danQ926, dam, seqA, emrR, ugi, cda1 operon [5] [4] |

| Phage Vectors | DNA shuttling between cells | P1 phage (85-100kb capacity); M13 phage (<5kb capacity) [5] |

| Degenerate Codons | Creating diverse mutant libraries | NNK codons (32 codons, all 20 amino acids); NNG/C; tailored reduced-code sets [2] |

| Error-Prone PCR Reagents | Introducing random point mutations | Mutazyme II; Taq polymerase with unbalanced dNTPs; Mn²⁺-supplemented buffers [1] |

| High-Fidelity PCR Systems | Library construction without additional mutations | Q5 Hot Start High-Fidelity Master Mix; Phusion DNA Polymerase [5] |

| Chemical Inducers | Tunable control of mutagenesis rates | Anhydrotetracycline hydrochloride; L-Arabinose; IPTG [5] |

| Selection Agents | Applying evolutionary pressure | Antibiotics; Toxic substrate analogs; Essential nutrient limitation [3] |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | High-throughput screening | Fluorogenic substrates; Antibody conjugates; Viability dyes [1] |

Critical Experimental Considerations

Library Design and Coverage

Effective directed evolution requires careful consideration of library size and diversity. For traditional methods, library coverage should significantly exceed the theoretical diversity to ensure representation of all variants. However, with smart library design and ML assistance, efficient exploration of sequence space is possible with dramatically reduced screening efforts [2]. Next-generation sequencing coverage requirements differ from genomic studies, with relatively lower coverage sufficient for identifying significantly enriched mutants [3].

Selection Parameter Optimization

Selection conditions profoundly impact directed evolution outcomes. Factors including cofactor concentration, substrate availability, reaction time, and temperature create evolutionary pressures that shape outcomes [3]. Implementing Design of Experiments (DoE) approaches to screen and benchmark selection parameters using small pilot libraries can optimize conditions before committing to large-scale experiments [3].

Balancing Exploration and Exploitation

The fundamental trade-off in directed evolution involves balancing exploration of novel sequence space with exploitation of known beneficial mutations. Active learning approaches address this through acquisition functions that explicitly manage this balance, while traditional methods typically rely on greedy exploitation with occasional exploration through recombination [2].

Directed evolution has matured from simple random mutagenesis screens to sophisticated, computationally enhanced platforms that efficiently navigate protein fitness landscapes. By mimicking Darwinian principles on accelerated timescales, these methods enable the optimization of complex biomolecular functions that challenge rational design approaches. The integration of machine learning, continuous evolution systems, and automated laboratories represents the current state of the art, offering unprecedented capabilities for enzyme engineering and therapeutic development. As these methodologies continue to advance, they expand the scope of addressable research questions and practical applications in biotechnology and medicine.

The journey from Spiegelman's pioneering RNA evolution experiments to today's sophisticated protein engineering represents a fundamental paradigm shift in biotechnology. Spiegelman's work in the 1960s demonstrated that molecular evolution could be directed in a test tube, using Qβ replicase to evolve RNA molecules optimized for replication [6]. This foundational concept laid the groundwork for the modern discipline of directed evolution, which has since matured into a transformative protein engineering technology that harnesses the principles of Darwinian evolution—iterative cycles of genetic diversification and selection—within a laboratory setting [6]. The profound impact of this approach was formally recognized with the 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded to Frances H. Arnold for establishing directed evolution as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology and industrial biocatalysis [6].

This evolution from simple nucleic acid systems to complex protein engineering reflects a strategic transition from exploring basic evolutionary principles to addressing pressing industrial and therapeutic challenges. Where Spiegelman's work asked whether evolution could be simplified and accelerated in a test tube, modern protein engineering answers with sophisticated solutions for enzyme optimization, therapeutic protein development, and sustainable biocatalysis—advances made possible by integrating cutting-edge computational tools, high-throughput screening, and artificial intelligence with the foundational principles of molecular evolution [6] [7].

The Directed Evolution Cycle: Methodology and Workflow

Core Principles of Laboratory Evolution

At its core, directed evolution functions as a two-part iterative engine that drives a protein population toward a desired functional goal by intentionally accelerating mutation rates and applying user-defined selection pressures [6]. This process compresses geological timescales of natural evolution into weeks or months through intentional acceleration of mutation rates coupled with unambiguous, user-defined selection pressure [6]. The success of any directed evolution campaign hinges on two critical factors: the quality and diversity of the initial library and the power of the screening method used to identify improved variants from a population dominated by neutral or deleterious mutations [6].

dot Evolutionary Cycle Diagram

Diagram 1: The iterative directed evolution cycle for protein engineering.

Methodologies for Generating Genetic Diversity

The creation of diverse gene variant libraries defines the boundaries of explorable sequence space and directly constrains potential evolutionary outcomes [6]. Several methods have been developed to introduce genetic variation, each with distinct advantages and biases that shape evolutionary trajectories [6].

Random Mutagenesis Techniques:

- Error-Prone PCR (epPCR): A modified PCR protocol that intentionally reduces DNA polymerase fidelity through polymerase selection, dNTP imbalance, and manganese ion addition, typically yielding 1–5 base mutations per kilobase [6].

- Limitations: Not truly random due to DNA polymerase bias favoring transition mutations over transversions, potentially restricting accessible sequence space [6].

Recombination-Based Methods:

- DNA Shuffling (Sexual PCR): Homologous genes are fragmented using DNaseI and reassembled through primerless PCR, resulting in crossovers that create chimeric genes with novel mutation combinations [6].

- Family Shuffling: Applies DNA shuffling to homologous genes from different species, accessing nature's standing variation to significantly accelerate functional improvement compared to single-gene approaches [6].

Focused and Semi-Rational Approaches:

- Site-Saturation Mutagenesis: Comprehensively explores all 19 possible amino acid substitutions at targeted positions, enabling deep interrogation of residue roles identified from prior rounds or structural models [6].

- Strategic Combination: Sequential application of methods (epPCR → DNA shuffling → saturation mutagenesis) ensures thorough exploration of promising fitness landscape regions while minimizing evolutionary dead ends [6].

Advanced Continuous Evolution Systems

Recent technological advances have established continuous evolution platforms that significantly accelerate protein engineering campaigns:

- EcORep (E.coli Orthogonal Replicon): Utilizes a special DNA replicon in E. coli with high mutation rates, enabling continuous mutagenesis and enrichment of variants with improved activity over time [8].

- PACE (Phage-assisted Continuous Evolution): Links enzyme function directly to bacteriophage propagation, where only phages carrying active recombinases can reproduce, creating continuous evolution pressure [8].

Quantitative Landscape of Modern Protein Engineering

Market Growth and Economic Impact

The protein engineering market has experienced substantial growth, demonstrating the field's expanding commercial and therapeutic significance.

Table 1: Protein Engineering Market Size and Projections

| Market Segment | 2024 Market Value | Projected 2033/2034 Value | CAGR | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Protein Engineering Market [9] | USD 3.6 Billion | USD 8.2 Billion (2033) | 9.5% (2025-2033) | AI-driven automation, therapeutic protein demand |

| Protein Design & Engineering Market [10] | USD 6.4 Billion | USD 25.1 Billion (2034) | 15.0% (2025-2034) | Chronic disease prevalence, recombinant DNA technology |

| Protein Engineering in Biotechnology [11] | USD 3.52 Million (2023) | USD 10.10 Million (2032) | 16.25% (2019-2033) | Precision medicine, sustainable biotechnology |

Technology and Application Segmentation

The protein engineering landscape encompasses diverse technologies and applications, with rational design and monoclonal antibodies currently dominating their respective segments.

Table 2: Protein Engineering Market Segmentation (2024)

| Segmentation Basis | Dominant Segment | Market Share | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Technology [9] | Rational Protein Design | Largest share | Computational modeling, AI-driven protein optimization, antibody engineering |

| Protein Type [9] | Monoclonal Antibodies | 24.5% | Targeted cancer therapies, autoimmune disease treatment |

| Product & Services [9] | Instruments | 53.2% | Protein characterization, structural analysis, high-throughput screening |

| End User [9] | Pharmaceutical & Biotechnology Companies | 45.3% | Therapeutic protein development, biologics manufacturing |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful directed evolution campaigns require specialized reagents and systems to enable library creation, host expression, and functional screening.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Directed Evolution

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations throughout gene sequence | Creating initial diversity libraries from parent gene [6] |

| DNase I | Fragments genes for DNA shuffling protocols | Recombination-based mutagenesis for combining beneficial mutations [6] |

| Saturation Mutagenesis Kit | Systematically explores all amino acid possibilities at targeted positions | Deep interrogation of key residues identified in preliminary screens [6] |

| Bridge RNA (bRNA) | Guides recombination by binding genomic target and donor DNA | Precise gene replacement in bridge recombinase systems [8] |

| Specialized Expression Vectors | Enables protein expression in host systems (E. coli, S. cerevisiae, P. pastoris) | Heterologous protein expression with appropriate post-translational modifications [12] |

| Fluorescent/Colorimetric Substrates | Enables high-throughput screening of enzyme activity | Microtiter plate-based screening of variant libraries [6] |

| Phage Display System | Links genotype to phenotype for selection-based screening | Continuous evolution platforms like PACE [8] |

Integrated Computational-Experimental Workflows

Physics-Based Modeling in Enzyme Engineering

Molecular modeling techniques have become indispensable complements to experimental directed evolution, particularly for addressing enzyme properties difficult to optimize through screening alone [7]. Molecular mechanics (MM) and quantum mechanics (QM) methods can theoretically measure experimentally-relevant functions for arbitrary systems with atom-resolved structures, regardless of enzyme origin or preferred operational conditions [7].

Key applications include:

- Electrostatic pre-organization: Engineering electric fields to stabilize transition states and enhance catalytic efficiency [7]

- Substrate access engineering: Modifying tunnel architectures to control reactant diffusion and product release [7]

- pH optimum modulation: Altering surface charge distributions to shift enzymatic activity to non-biological conditions [7]

Machine Learning-Enhanced Evolution

Machine learning now accelerates directed evolution by predicting sequence-function relationships, enabling more intelligent library design and reducing experimental screening burdens [7] [12]. Deep mutational learning (DML) approaches explore thousands of sequence variations in silico to identify promising candidates before experimental validation [8].

dot Computational-Experimental Integration

Diagram 2: Integrated computational-experimental workflow for modern protein engineering.

Application Notes: Practical Implementation for Enzyme Engineering

Case Study: Co-evolution of β-Glucosidase Activity and Acid Tolerance

Background: Lignocellulose degradation for biofuel production requires enzymes tolerant to inhibitory compounds like formic acid generated during biomass pretreatment. Wild-type Penicillium oxalicum 16 β-glucosidase (16BGL) shows excellent thermostability but suffers significant inhibition at 15 mg/mL formic acid [12].

Challenge: Simultaneously enhance enzymatic activity and organic acid tolerance without prior structural knowledge.

Solution: Implementation of a novel SEP (Segmental Error-prone PCR) and DDS (Directed DNA Shuffling) approach:

- Gene Segmentation: 16bgl divided into 400-500 bp segments with 20-30 bp overlapping regions

- Parallel Mutagenesis: Each segment subjected to independent error-prone PCR

- Directed Recombination: Mutated segments assembled via overlap extension PCR using S. cerevisiae homologous recombination

- Screening: Variants screened for both hydrolysis activity and formic acid tolerance

Results: This approach generated variants with significantly improved performance compared to traditional methods, demonstrating robust enhancement of multiple functionalities simultaneously [12].

Protocol: Segmental Error-Prone PCR with Directed DNA Shuffling

Materials:

- Target gene (16bgl or gene of interest) divided into segments with overlapping regions

- Error-prone PCR reagents: Taq polymerase (non-proofreading), unbalanced dNTPs, Mn²⁺

- S. cerevisiae strain with high recombination efficiency (e.g., BY4741)

- Expression vector with constitutive promoter (e.g., pYAT22 with TEF1 promoter)

- Screening substrates (pNPG for β-glucosidase, formic acid for tolerance selection)

Procedure:

Segment Amplification:

- Perform separate error-prone PCR reactions for each gene segment

- Use Mn²⁺ concentration of 0.2-0.5 mM to control mutation rate (target: 1-3 mutations/segment)

- Verify fragment size and yield by agarose gel electrophoresis

Library Assembly:

- Combine purified mutated segments with linearized expression vector

- Transform into S. cerevisiae using lithium acetate method

- Exploit yeast homologous recombination for in vivo assembly

- Plate on appropriate selective medium and incubate 48-72 hours

Dual-Activity Screening:

- Pick individual colonies into 96-well deep plates containing growth medium

- Culture with shaking for 48-72 hours at 30°C

- Transfer supernatant to assay plates containing both activity substrate and inhibitory compound

- Identify clones showing improved activity under inhibitory conditions

Validation and Iteration:

- Sequence improved variants to identify beneficial mutations

- Use best performers as templates for subsequent evolution rounds

- Combine beneficial mutations through additional shuffling cycles

Technical Notes:

- SEP ensures even mutation distribution across entire gene sequence

- DDS minimizes reverse mutations common in traditional DNA shuffling

- S. cerevisiae expression enables proper folding and post-translational modifications for eukaryotic enzymes

- Dual-parameter screening essential for co-evolution of multiple traits [12]

Future Perspectives and Emerging Applications

The field of protein engineering continues to evolve with several emerging trends shaping its future trajectory:

- AI-Driven Protein Design: Machine learning algorithms now predict protein structure and function with increasing accuracy, enabling de novo design of proteins with customized properties [7] [11]

- Therapeutic Enzyme Engineering: Development of enzymes for gene therapy applications, including bridge recombinases for precise gene replacement strategies to treat genetic disorders like Alpha-1 Antitrypsin Deficiency [8]

- Sustainable Biocatalysis: Engineering enzymes for green chemistry applications, including biomass conversion, biodegradation of environmental pollutants, and sustainable manufacturing processes [7] [11]

- Microfluidic High-Throughput Screening: Emerging platforms enabling ultra-high-throughput screening of protein variant libraries, dramatically accelerating the evolution cycle [11]

The transition from Spiegelman's simple RNA evolution systems to today's integrated computational-experimental protein engineering platforms represents remarkable progress in our ability to harness evolutionary principles for biotechnology. Where early work demonstrated the fundamental feasibility of test-tube evolution, modern approaches now deliver customized protein solutions addressing critical challenges in therapeutics, industrial catalysis, and sustainability. As computational power grows and our understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships deepens, protein engineering continues to expand its capabilities, promising increasingly sophisticated biological designs for the future.

Directed evolution stands as a cornerstone methodology in enzyme engineering, enabling researchers to mimic natural selection in laboratory settings to tailor biocatalysts for industrial, therapeutic, and research applications. This approach relies on the recursive application of a core cycle comprising mutagenesis, selection, and amplification to navigate the vast sequence space of proteins and identify variants with enhanced properties. The efficiency of this process is critically dependent on the ability to generate diverse variant libraries and to couple their functional performance to a high-throughput screen or selectable output. This application note details established and emerging protocols for implementing this core cycle, providing a framework for the directed evolution of enzymes, with a specific focus on challenging targets such as hydrocarbon-producing enzymes. The content is structured to serve as a practical guide for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in advancing biocatalyst design.

The design of a directed evolution campaign requires careful consideration of library size, mutation rates, and the probability of discovering improved variants. The table below summarizes key quantitative parameters from recent studies.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Directed Evolution Campaigns

| Parameter | Representative Value or Range | Context and Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Beneficial Mutation Rate | ~1% of all single-site mutations [13] | Highlights the challenge of library design; the vast majority of mutations are neutral or deleterious. |

| Theoretical Library Size | 5,757 single amino acid substitutions (for a 303-residue enzyme) [13] | The total possible diversity for a single enzyme scaffold, underscoring the need for smart library design. |

| Filtered Library Size | ~30% of all possible single-site mutations (approx. 1,800 variants) [13] | Example of using computational stability predictions (ΔΔG < -0.5 REU) to reduce screening burden without losing beneficial mutations. |

| Coverage in Oligo Pools | >50% of targeted mutations [13] | Acceptable coverage level when using complex gene libraries synthesized from oligo pools. |

| Catalytic Improvement | >450-fold activity increase in 5 rounds [13] | Demonstrates the potential for rapid optimization using computationally guided evolution. |

| Catalytic Efficiency (kcat/Km) | 1.7 × 10⁵ M⁻¹ s⁻¹ (for an evolved Kemp eliminase) [13] | Example of a high-efficiency enzyme achievable through directed evolution. |

Experimental Protocols for the Core Cycle

Mutagenesis and Library Construction

Objective: To generate a comprehensive yet tractable library of gene variants encoding the target enzyme.

Protocol 1: Saturation Mutagenesis with PALS-C Cloning [14]

This protocol is ideal for introducing small-sized variants (e.g., single amino acid substitutions) across a gene of interest to create an allelic series.

- Library Design: Define the target residues for saturation mutagenesis. This can be all residues in the gene, a subset based on structural data (e.g., within 6 Å of the active site), or residues predicted by bioinformatic tools.

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: Synthesize a pool of oligonucleotides designed to introduce the desired mutations during the cloning process.

- PALS-C Cloning: Utilize the Programmed Allelic Series with Common procedures (PALS-C) cloning method to introduce the variant oligonucleotide pool into a plasmid containing the gene of interest.

- Transformation: Transform the resulting variant plasmid pool into a competent E. coli strain for propagation. The transformed cells constitute the variant library ready for selection.

Protocol 2: Segmental Error-prone PCR (SEP) and Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS) [12]

This method combines random mutagenesis with homologous recombination to evolve large genes and incorporate multiple beneficial mutations.

- Gene Segmentation: Divide the target gene into several overlapping segments.

- Error-prone PCR: Perform error-prone PCR on each segment separately to introduce random mutations within each segment.

- Directed DNA Shuffling (DDS): Mix the mutated segments with a linearized plasmid vector containing homologous ends. Co-transform this mixture into S. cerevisiae, which leverages its high homologous recombination efficiency to assemble the full-length, shuffled gene variant into the vector in vivo.

- Plasmid Recovery: Isolve the plasmid library from the yeast pool and transform into E. coli for amplification and storage.

Selection and Screening

Objective: To identify variant enzymes with the desired functional enhancement from the mutant library.

Protocol 3: Functional Signaling and FACS [14]

This protocol is applicable when enzyme function can be coupled to a fluorescent signal.

- Cell Line Preparation: Establish a cell line platform that expresses the target enzyme in a manner where its activity induces a measurable fluorescent signal (e.g., via a coupled signaling pathway).

- Library Delivery: Deliver the variant plasmid pool into the engineered cell line using an efficient method like nucleofection.

- Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS): After an appropriate incubation period, analyze and sort the cell population using FACS. Cells exhibiting fluorescence intensity above a predetermined threshold (indicating high enzyme activity) are collected.

- Variant Recovery: Isolate plasmids from the sorted cell population for sequence analysis and amplification.

Protocol 4: Growth-Coupled Continuous Evolution [4]

This method links enzyme function directly to host cell survival, enabling autonomous evolution over many generations.

- Genetic Circuit Engineering: Engineer the host organism (e.g., yeast or bacteria) so that the desired enzyme activity is essential for growth or provides a strong selective advantage. This can be achieved using orthogonal replication systems (e.g., OrthoRep) or synthetic genetic circuits (e.g., NIMPLY logic).

- Library Introduction: Introduce the mutant library into the engineered host.

- Continuous Culture: Propagate the culture over an extended period under selective conditions. Variants with improved function will outcompete others and dominate the population.

- Variant Isolation: Periodically sample the culture and isolate the dominant genotypes for characterization.

Amplification and Analysis

Objective: To propagate selected hits and quantitatively characterize their improved properties.

Protocol 5: Next-Generation Sequencing and Functional Score Generation [14]

- Amplification: Use the plasmid population recovered from the selection step to transform E. coli for bulk amplification or to generate clonal isolates.

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Subject the amplified plasmid pool to NGS to determine the full sequence diversity and enrichment of specific variants.

- Functional Scoring: Analyze the NGS data (from pre-selection and post-selection libraries) to calculate an enrichment score for each variant. This score serves as a quantitative metric of functional performance.

- Hit Validation: Clonally isolate top-ranked variants and characterize their biochemical properties (e.g., kcat, Km, thermostability) using standard enzymatic assays to confirm improvement.

Diagram 1: Core directed evolution cycle workflow.

Research Reagent Solutions

A successful directed evolution project relies on a toolkit of specialized reagents and platforms. The following table catalogues essential solutions referenced in the protocols.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Protocol / Context |

|---|---|---|

| PALS-C Cloning System | Introduces small-sized genetic variants into a gene of interest in a programmable manner. | Saturation Mutagenesis [14] |

| OrthoRep System | An orthogonal DNA polymerase-plasmid pair in yeast that enables continuous in vivo mutagenesis and evolution. | Continuous & Automated Evolution [4] |

| NIMPLY Genetic Circuit | A synthetic genetic circuit that can implement a NOT logic function, useful for selecting against unwanted activities and enhancing selectivity. | Selection for Specificity [4] |

| Computational Stability Filter (e.g., Rosetta ΔΔG) | Predicts changes in protein folding free energy upon mutation to filter out destabilizing variants prior to library construction. | Library Design [13] |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | Enables high-throughput, function-based sorting of single cells from large variant libraries (>10⁶ cells). | High-Throughput Screening [14] |

| HotSpot Wizard | A bioinformatic tool that analyzes sequence, structure, and evolutionary data to identify residues for mutagenesis. | Semi-Rational Library Design [13] |

The core cycle of mutagenesis, selection, and amplification provides a robust and powerful framework for engineering novel enzymes. The protocols detailed herein, ranging from targeted saturation mutagenesis to fully automated continuous evolution platforms, offer researchers a suite of tools to address diverse enzyme engineering challenges. The integration of computational design and filtering at the library construction stage, coupled with highly sensitive screening or selection methods, dramatically accelerates the evolution of desired enzymatic functions. As these methodologies continue to mature, they will undoubtedly expand the scope of directed evolution, enabling the creation of bespoke biocatalysts for an ever-widening array of applications in biotechnology and medicine.

In the field of enzyme engineering, the development of biocatalysts tailored for industrial applications, therapeutic development, and sustainable technologies relies on two powerful, yet philosophically distinct methodologies: rational design and directed evolution [15] [16]. Rational design represents a knowledge-based approach where scientists, like architects, use detailed understanding of protein structure and function to implement specific, predictive changes [15] [17]. In contrast, directed evolution mimics natural selection in laboratory settings, employing iterative rounds of random mutagenesis and screening to discover improved enzyme variants without requiring prior mechanistic knowledge [1] [18]. The 2018 Nobel Prize in Chemistry awarded for the directed evolution of enzymes underscores the transformative impact of these technologies [6]. This analysis examines the advantages, limitations, and practical applications of both approaches within enzyme engineering research, providing structured comparisons and detailed protocols to guide methodological selection and implementation.

Core Principles and Methodological Comparison

Fundamental Philosophies and Technical Execution

Rational design operates on the principle that detailed knowledge of enzyme structure, mechanism, and sequence-structure-function relationships enables precise, targeted improvements. This approach requires high-quality structural data (from X-ray crystallography or NMR) or reliable computational models (from AlphaFold or Rosetta), combined with molecular modeling and dynamics simulations to predict the effects of mutations before experimental validation [17] [19]. Key techniques include site-directed mutagenesis for specific amino acid substitutions and structure-based computational design algorithms that calculate optimal mutations to enhance properties like stability or substrate specificity [17] [20].

Directed evolution, conversely, embraces a "test-and-learn" philosophy that harnesses Darwinian principles of mutation and selection without requiring exhaustive prior structural knowledge [18] [6]. This methodology involves creating genetic diversity through random mutagenesis or recombination, followed by high-throughput screening or selection to identify improved variants, which then serve as templates for subsequent evolution rounds [1] [6]. The power of directed evolution lies in its ability to explore vast sequence spaces and identify beneficial mutations that would be difficult to predict computationally, including cooperative effects between distant residues [18] [20].

Comparative Analysis of Advantages and Limitations

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of rational design and directed evolution approaches

| Aspect | Rational Design | Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge Requirements | Requires detailed 3D structural information, mechanistic understanding, and computational modeling [15] [17] | Requires no prior structural knowledge; operates effectively with sequence information alone [15] [6] |

| Methodological Approach | Targeted, specific mutations based on structural and functional hypotheses [17] [19] | Random mutagenesis and screening/selection without predefined mutation targets [1] [18] |

| Library Size | Small, focused libraries (often < 100 variants) [17] [20] | Very large libraries (10⁴–10¹⁴ variants) requiring high-throughput handling [1] [6] |

| Time Investment | Less time-consuming for initial designs; reduced screening burden [15] [19] | Time-intensive iterative cycles; extensive screening/selection requirements [15] [17] |

| Resource Requirements | Specialized computational resources and structural biology expertise [17] [20] | High-throughput screening infrastructure and specialized assays [1] [6] |

| Risk of Failure | High if structural models are inaccurate or mechanism is incompletely understood [16] [17] | Lower; empirical screening identifies functional variants despite knowledge gaps [15] [18] |

| Discovery Potential | Limited to predictable improvements based on existing knowledge [15] [20] | High potential for discovering novel, non-intuitive solutions and functional combinations [18] [6] |

| Optimal Application Scenarios | Well-characterized enzymes, specific property enhancements (e.g., single residue changes) [17] [19] | Poorly characterized systems, complex multi-property optimization, novel function creation [15] [21] |

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Rational Design Workflow Protocol

Step 1: Structural and Sequence Analysis

- Obtain high-resolution protein structure through X-ray crystallography or NMR, or generate a reliable homology model using AlphaFold2 or Rosetta [17] [21]

- Perform multiple sequence alignment with homologous enzymes to identify evolutionarily conserved and variable regions [17] [20]

- Analyze active site architecture, substrate binding pockets, and protein flexibility through B-factor analysis [17]

Step 2: Computational Modeling and In Silico Design

- Identify target residues for mutation based on structural analysis (e.g., substrate channel residues for altering specificity, surface residues for improving stability) [17] [20]

- Use molecular dynamics simulations to predict the structural impact of proposed mutations and calculate binding energies for substrate-enzyme complexes [20]

- Generate a focused library of 10-50 rationally designed variants using site-directed mutagenesis primers [17]

Step 3: Experimental Validation

- Express and purify designed variants using standard protein expression systems (E. coli, yeast, or HEK293 cells) [1]

- Characterize enzyme activity, specificity, and stability using appropriate biochemical assays [17]

- For successful designs, determine crystal structures to verify computational predictions and guide further optimization [17]

Directed Evolution Workflow Protocol

Step 1: Diversity Generation

- Random Mutagenesis: Use error-prone PCR (epPCR) with Mn²⁺ and nucleotide imbalances to achieve 1-5 mutations per kilobase [1] [6]. Optimize mutation rate to balance diversity and protein functionality.

- Recombination Methods: Implement DNA shuffling or StEP (Staggered Extension Process) to recombine beneficial mutations from multiple parent sequences [18] [6]. This approach is particularly valuable after initial rounds of evolution.

- Saturation Mutagenesis: For semi-rational approaches, target specific residues identified as "hotspots" through previous evolution rounds or structural analysis [1] [20].

Step 2: Library Screening and Selection

- Selection Methods: Develop growth-coupled selection systems where desired enzyme activity confers survival advantage [1] [21]. For hydrocarbon-producing enzymes, this may involve linking production to detectable metabolites or resistance markers.

- High-Throughput Screening: Implement microtiter plate-based assays (96- or 384-well) with colorimetric or fluorometric readouts [1] [6]. For intracellular enzymes, use FACS (Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting) with fluorescent substrates or products [1].

- Quality Control: Sequence top-performing variants to identify beneficial mutations and eliminate duplicates before subsequent evolution rounds [6].

Step 3: Iterative Optimization

- Use best-performing variants from each round as templates for subsequent diversification [18] [6]

- Gradually increase selection pressure (e.g., higher temperature, altered pH, stricter substrate specificity) over multiple generations [6]

- Typically require 3-8 evolution rounds to achieve significant improvements [18]

- After final round, characterize top variants kinetically and structurally to understand molecular basis of improvements [1]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 2: Key research reagents and solutions for enzyme engineering approaches

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Directed Evolution | Rational Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Introduces random mutations during gene amplification | Essential [1] [6] | Not typically used |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit | Creates specific, targeted point mutations | Used in later stages for combination | Essential [17] [19] |

| Phusion or Taq Polymerase | DNA amplification; Taq used for epPCR due to lower fidelity | Essential [6] | Standard PCR |

| Mn²⁺ and Unbalanced dNTPs | Critical components for reducing fidelity in error-prone PCR | Essential [6] | Not used |

| DNase I | Fragments DNA for recombination in DNA shuffling | Essential for recombination [18] | Not used |

| Microtiter Plates (96/384-well) | High-throughput screening of variant libraries | Essential [1] [6] | Limited use |

| Fluorescent Substrates/Reporters | Enable high-throughput screening via FACS or plate readers | Essential [1] [6] | For validation |

| E. coli Expression Strains | Standard host for protein variant expression | Standard [1] | Standard [17] |

| Chromatography Systems | Protein purification for biochemical characterization | For validation [1] | Essential [17] |

| Crystallization Screens | Obtaining structural data for computational design | Occasionally for analysis | Essential [17] |

Emerging Trends and Integrated Approaches

Semi-Rational Design: Bridging the Methodological Divide

The distinction between rational design and directed evolution has blurred with the emergence of semi-rational approaches that leverage the strengths of both methodologies [20] [21]. These integrated strategies use computational and bioinformatic analyses to identify promising target regions or residues, then employ focused randomization at these sites to create smaller, higher-quality libraries [20]. Key semi-rational techniques include:

- CASTing (Combinatorial Active Site Saturation Test): Systematically targets residues around the active site with saturation mutagenesis to alter substrate specificity and enantioselectivity [17] [20]

- Structure-Guided Consensus Approach: Identifies evolutionarily conserved residues through multiple sequence alignments and reverts non-consensus amino acids to consensus to enhance thermostability [17]

- SCHEMA Structure-Guided Recombination: Computational algorithm that estimates disruption caused by recombining amino acid residues in chimeric proteins, enabling shuffling of sequences with low similarity [17]

- B-Factor Iterative Test (B-Fit): Targets positions with high flexibility (high B-factors) in crystal structures for saturation mutagenesis to improve stability [17]

The Impact of Computational Advances

Recent breakthroughs in computational structural biology have significantly influenced both rational and evolutionary approaches [16] [21]. AlphaFold and RoseTTAFold have dramatically improved access to reliable protein structure predictions, reducing dependence on experimental crystallography for rational design [21]. Machine learning algorithms now analyze high-throughput screening data to identify patterns and predict beneficial mutations, accelerating the directed evolution cycle [16] [20]. Autonomous protein engineering platforms like SAMPLE (Self-driving Autonomous Machines for Protein Landscape Exploration) combine AI-driven protein design with robotic experimentation systems, creating closed-loop optimization platforms that continuously learn from experimental results [19].

Both directed evolution and rational design represent powerful, complementary approaches in the enzyme engineering toolkit. Directed evolution excels at navigating complex fitness landscapes without requiring detailed structural knowledge, often discovering non-intuitive solutions [18] [6]. Rational design offers precision and efficiency for well-characterized systems where structure-function relationships are sufficiently understood [17] [19]. The future of enzyme engineering lies in the continued integration of these approaches, leveraging computational advances, machine learning, and high-throughput automation to create increasingly sophisticated biocatalysts for pharmaceutical applications, sustainable energy production, and industrial biotechnology [16] [20] [21]. Researchers should select their approach based on the specific enzyme system, available structural information, and desired properties, while remaining open to hybrid strategies that maximize the benefits of both methodologies.

Directed evolution stands as one of the most powerful tools in modern protein engineering, enabling researchers to tailor enzymes for specific applications in biotechnology, therapeutics, and sustainable chemistry [22] [1]. This process mimics natural evolution in laboratory settings through iterative rounds of genetic diversification and artificial selection or screening to discover proteins with enhanced or entirely new functions [22]. The conceptual framework that underpins our understanding of how proteins adapt during directed evolution is the fitness landscape—a multidimensional representation of the relationship between protein sequence and functional fitness [22] [23].

First introduced by Sewall Wright in 1932, fitness landscapes provide a powerful metaphor for visualizing evolution as a navigational challenge across a topographic surface [23] [24]. In this representation, each point on the landscape corresponds to a specific protein sequence, with elevation representing its fitness value—how well the protein performs the desired function under defined conditions [22]. Evolutionary optimization then becomes a process of "uphill climbing" across this landscape, with the goal of reaching the highest peaks corresponding to sequences with optimal function [25]. While the original concept visualized genotypic space as a hypercube with fitness as height, modern interpretations recognize three distinct characterizations: genotype-to-fitness landscapes, allele frequency-to-fitness landscapes, and phenotype-to-fitness landscapes [23].

The true power of the fitness landscape concept lies in its ability to rationalize the strategic challenges of directed evolution. The sequence space for even a modest-sized protein is astronomically large—for a 100-amino acid protein, there are 20¹⁰⁰ (∼10¹³⁰) possible sequences, far more than the number of atoms in the universe [22]. Fitness landscapes provide a conceptual framework for developing efficient search strategies to navigate this vast space, helping researchers understand why some evolutionary paths succeed while others lead to dead ends [22] [25].

Theoretical Framework: Characterizing Landscape Topography

Landscape Ruggedness and Evolutionary Trajectories

The structure of a fitness landscape profoundly influences the efficiency and outcome of directed evolution campaigns [22]. Landscapes vary considerably in their topography, which can be envisioned along a spectrum from smooth, single-peaked "Fujiyama" landscapes to highly rugged, multi-peaked "Badlands" landscapes [22]. Smooth landscapes feature gradual, incremental fitness changes between neighboring sequences, offering many accessible uphill paths that enable relatively straightforward optimization through the accumulation of small, beneficial mutations [22] [25]. In contrast, rugged landscapes contain numerous local fitness optima separated by valleys of lower fitness, creating evolutionary traps where populations can become stranded on suboptimal peaks [22] [23].

The ruggedness of a landscape is primarily determined by the prevalence of epistatic interactions—situations where the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations in the sequence [22]. When epistasis is minimal, landscapes tend to be smooth and easily navigable. However, when strong epistatic interactions occur, the landscape becomes rugged, and evolutionary trajectories may require temporarily deleterious mutations or multiple simultaneous changes to escape local optima and access higher fitness regions [22] [25]. Empirical studies of evolutionary pathways have demonstrated that many directed evolution campaigns successfully navigate these landscapes through simple adaptive walks involving sequential beneficial mutations, often without requiring complex epistatic jumps [25].

High-Dimensional Considerations and Visualization Challenges

While the terrestrial landscape analogy provides intuitive understanding, it suffers from significant limitations when applied to real protein sequences. The genotypic space of proteins is inherently high-dimensional, with each amino acid position representing a potential dimension [24]. This high-dimensionality creates topological properties fundamentally different from the intuitive three-dimensional landscapes we can easily visualize [24]. In sufficiently high-dimensional spaces, even randomly assigned fitness values tend to create interconnected networks of high-fitness sequences, reducing the problem of isolated peaks that characterizes low-dimensional landscapes [24].

Advanced visualization techniques have been developed to create more accurate low-dimensional representations of fitness landscapes. These methods plot genotypes in a manner that reflects the ease or difficulty of evolving from one genotype to another, considering the fitnesses of intermediate genotypes [24]. Such representations position genotypes connected by neutral paths close together, while separating those divided by fitness valleys, even if their mutational distance is small [24]. This approach provides a more evolutionarily relevant visualization that highlights the major features of the fitness landscape as experienced by an evolving population.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Fitness Landscape Types

| Feature | Smooth Landscape | Rugged Landscape |

|---|---|---|

| Topography | Single peak, gradual slopes | Multiple peaks separated by valleys |

| Epistasis | Minimal or absent | Prevalent and strong |

| Evolutionary Paths | Many accessible uphill paths | Limited paths, often requiring temporary fitness losses |

| Local Optima | Rare | Common |

| Predictability | Highly predictable trajectories | Difficult to predict optimal paths |

| Experimental Approach | Straightforward iterative improvement | Requires sophisticated library design and exploration strategies |

Dynamic Fitness Seascapes

An important extension of the traditional fitness landscape concept recognizes that selection pressures are often not static but change over time, giving rise to fitness seascapes [23]. In real-world applications, enzymes must frequently function in changing environments, such as shifting pH, temperature, or substrate availability [23]. Fitness seascapes model these dynamic adaptive surfaces whose peaks and valleys change over time due to factors including environmental changes, drug exposure cycles, immune surveillance, and co-evolutionary interactions with other species [23]. This concept is particularly relevant for therapeutic enzyme engineering, where factors such as drug cycling and evolving host environments create moving targets for optimization [23].

Practical Application: Navigating Landscapes in Enzyme Engineering

Library Design Strategies for Landscape Exploration

The fundamental challenge in directed evolution is efficiently exploring the vast sequence space to identify functional improvements. Different library generation strategies offer distinct approaches to navigating fitness landscapes, each with advantages for specific landscape topographies.

Random Mutagenesis through error-prone PCR (epPCR) introduces mutations throughout the entire gene, providing broad exploration of the local landscape region [1] [6]. This approach is particularly valuable in early stages when little is known about the sequence-function relationship or when targeting unpredictable regions distant from the active site [6]. However, epPCR has inherent biases—it favors transition over transversion mutations and can only access approximately 5-6 of the 19 possible alternative amino acids at any given position due to genetic code degeneracy [6].

Recombination-based methods such as DNA shuffling mimic natural sexual recombination by breaking multiple parent genes into fragments and reassembling them into chimeric sequences [1] [6]. This approach is highly effective for combining beneficial mutations from different lineages and exploring new regions of the fitness landscape through crossover events [6]. Family shuffling, which recombines homologous genes from different species, leverages nature's evolutionary innovation to access functionally relevant sequence space more efficiently than mutating a single gene [6].

Focused mutagenesis strategies, including site-saturation mutagenesis, target specific regions or residues informed by structural knowledge or previous evolutionary rounds [1] [6]. This semi-rational approach creates smaller, higher-quality libraries that intensively explore promising "hotspots" in the landscape, dramatically increasing the efficiency of finding improvements [6]. These targeted methods are particularly valuable for navigating rugged landscapes where random exploration would be inefficient.

Table 2: Library Generation Methods for Fitness Landscape Exploration

| Method | Mechanism | Landscape Exploration | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | Random point mutations via low-fidelity amplification | Broad local exploration | Easy to perform; no prior knowledge needed | Mutational bias; limited amino acid coverage |

| DNA Shuffling | Recombination of gene fragments | Exploration through combination | Mimics natural recombination; combines beneficial mutations | Requires sequence homology (>70-75%) |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Targeted exploration of specific residues | Focused deep exploration | High-quality libraries; excellent for optimization | Requires prior knowledge of important positions |

| Orthogonal Mutagenesis Systems | In vivo mutagenesis of target sequences | Continuous exploration | Can be coupled with selection; automated evolution | Lower mutation frequency; size limitations |

Advanced Navigation with Artificial Intelligence

Recent advances integrate artificial intelligence with biofoundry automation to create autonomous enzyme engineering platforms that efficiently navigate fitness landscapes [26]. These systems combine protein language models (such as ESM-2) with epistasis models and machine learning to design intelligent mutant libraries that maximize the discovery of improved variants [26]. The AI models predict variant fitness from sequence data, enabling prioritization of promising regions in the vast sequence space [26].

In practice, these platforms have demonstrated remarkable efficiency, engineering enzymes with 16- to 26-fold improvements in activity in just four rounds over four weeks while requiring construction and characterization of fewer than 500 variants for each enzyme [26]. This represents a significant acceleration compared to traditional directed evolution, achieved through more intelligent navigation of the fitness landscape guided by machine learning predictions.

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution Campaign

Phase 1: Library Design and Construction

Objective: Create a diverse mutant library targeting regions of the fitness landscape with high probability of functional improvements.

Materials:

- Template gene encoding wild-type enzyme

- Oligonucleotides for amplification and mutagenesis

- High-fidelity and error-prone DNA polymerases

- dNTP mixture, Mg²⁺, and Mn²⁺ solutions

- DpnI restriction enzyme

- Competent expression cells (E. coli or other host)

- Transformation reagents

Procedure:

Initial Library Design:

- For unexplored landscapes: Use protein language models (ESM-2) to identify positions with high mutational tolerance and potential functional impact [26].

- For landscapes with some characterization: Employ epistasis models (EVmutation) focusing on co-evolutionary patterns in homologs [26].

- Generate initial library of 150-200 variants combining predictions from both models [26].

Library Construction via HiFi Assembly:

- Perform mutagenesis PCR using optimized high-fidelity assembly methods that eliminate need for intermediate sequence verification [26].

- Use the following reaction mixture:

- Thermal cycler conditions:

- Digest template with DpnI (1 U/μL, 37°C for 1 hour) to reduce background [26].

- Transform into competent expression cells via high-efficiency transformation (96-well format) [26].

- Plate on selective media and incubate overnight at 37°C.

Sequence Verification:

- Randomly pick and sequence 5-10% of clones to verify mutagenesis accuracy (expected >95% correct) [26].

- Proceed with correct clones without full library sequencing to maintain workflow continuity.

Phase 2: High-Throughput Screening

Objective: Identify improved variants from the mutant library through quantitative fitness assessment.

Materials:

- 96-well or 384-well microtiter plates

- Cell lysis reagents (lysozyme, detergents)

- Enzyme substrates (colorimetric/fluorometric)

- Plate readers (absorbance/fluorescence)

- Automated liquid handling systems

- Robotic colony pickers

Procedure:

Protein Expression:

- Inoculate individual colonies into deep-well plates containing expression media.

- Grow cultures to mid-log phase (OD₆₀₀ ≈ 0.6-0.8) at 37°C with shaking.

- Induce protein expression with appropriate inducer (e.g., 0.1-1 mM IPTG for lac-based systems).

- Incubate overnight at appropriate temperature (typically 25-30°C for proper folding).

Cell Lysis and Protein Preparation:

- Harvest cells by centrifugation (3000 × g, 10 min).

- Resuspend pellets in lysis buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mg/mL lysozyme, 0.1% Triton X-100).

- Incubate 30-60 min at 37°C with shaking.

- Clarify lysates by centrifugation (4000 × g, 20 min).

Activity Screening:

- Transfer clarified lysates to assay plates.

- Add appropriate substrates at optimized concentrations.

- Monitor product formation continuously or at fixed timepoints using plate readers.

- For thermostability assessments: Include heat challenge step (e.g., 55-65°C for 10-30 min) prior to activity measurement [6].

- Normalize activity measurements to total protein concentration.

Data Analysis:

- Calculate fold-improvement relative to wild-type enzyme for each variant.

- Identify top performers (typically 5-10% of library) showing significant improvement in target property.

- Select best variants for next round based on both absolute performance and diversity of mutations.

Phase 3: Iterative Optimization and Analysis

Objective: Accumulate beneficial mutations through successive generations while maintaining library diversity.

Procedure:

Gene Recovery and Recombination:

- Isolate plasmid DNA from top-performing variants.

- Use DNA shuffling or related methods to recombine beneficial mutations:

- Amplify full-length chimeric genes using outer primers.

Iterative Rounds:

- Repeat library construction and screening for 3-5 rounds or until performance plateaus.

- Increase selection stringency gradually (e.g., higher temperature, lower substrate concentration).

- In later rounds, incorporate site-saturation mutagenesis at identified hotspot positions.

Landscape Analysis:

- Sequence all improved variants to map mutations.

- Construct fitness landscape models based on sequence-function data.

- Identify epistatic interactions and evolutionary paths.

- Use insights to inform future engineering campaigns on related enzymes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fitness Landscape Exploration

| Reagent/Category | Function | Examples & Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Diversification Enzymes | Generate genetic diversity | Error-prone polymerases (Taq, Mutazyme II), DNaseI for shuffling, Restriction enzymes (DpnI) |

| Expression Systems | Protein production | Competent E. coli strains (BL21, XL1-Blue), Expression vectors (pET, pBAD), Induction reagents (IPTG, arabinose) |

| Screening Reagents | Fitness assessment | Colorimetric substrates (pNPP, ONPG), Fluorogenic substrates (MUG, AMC derivatives), Lysis buffers, Coupled assay components |

| Automation Equipment | High-throughput processing | Robotic liquid handlers, Automated colony pickers, Multi-mode plate readers, PCR thermocyclers |

| AI/ML Tools | Landscape navigation | Protein language models (ESM-2), Epistasis models (EVmutation), Fitness prediction algorithms, Data analysis pipelines |

| Selection Materials | In vivo enrichment | Antibiotics for selection, Specialized growth media, Reporter strains, Fluorescent activation systems |

The fitness landscape concept provides both a theoretical framework and practical guidance for optimizing enzyme engineering campaigns. By understanding landscape topography—recognizing smooth regions amenable to simple adaptive walks versus rugged territories requiring sophisticated navigation strategies—researchers can design more efficient directed evolution experiments. The integration of AI-powered design with automated biofoundry execution represents the cutting edge of fitness landscape exploration, enabling intelligent navigation of sequence space that dramatically accelerates the discovery of improved enzymes [26].

As the field advances, the dynamic nature of fitness "seascapes" presents both challenges and opportunities for enzyme engineering in real-world applications where environmental conditions fluctuate [23]. Future developments will likely focus on predictive landscape modeling that can anticipate evolutionary trajectories and identify optimal paths to desired functions, further reducing the time and resources required to engineer enzymes for biomedical, industrial, and sustainability applications.

A Toolkit for Innovation: Modern Directed Evolution Methods and Their Transformative Applications

Directed evolution stands as a powerful methodology in enzyme engineering, enabling researchers to optimize enzyme properties such as thermostability, substrate specificity, enantioselectivity, and activity under non-physiological conditions without requiring comprehensive structural knowledge [27] [28]. This approach mimics natural evolution through iterative cycles of gene mutagenesis, expression, and screening to identify improved enzyme variants. The foundation of any successful directed evolution campaign lies in the creation of high-quality mutant libraries that explore productive regions of sequence space. The quality and design of these libraries significantly influence the efficiency of identifying enhanced variants, as screening capacity often represents the primary bottleneck in directed evolution pipelines [27].

Library generation techniques can be broadly categorized into random and targeted approaches. Random mutagenesis methods, such as error-prone PCR (epPCR) and DNA shuffling, introduce mutations throughout the gene sequence, making them particularly valuable when structural information is limited or when seeking to improve globally determined properties like thermostability [28]. In contrast, targeted approaches such as saturation mutagenesis focus genetic diversity on specific residues or regions, typically identified through structural analysis or sequence-function relationships, thereby creating "smarter" libraries with reduced screening burdens [27] [29]. The selection of an appropriate library generation strategy depends on multiple factors, including the availability of structural information, the targeted enzyme property, and the available screening capacity. This application note provides detailed protocols and implementation guidelines for three fundamental library generation techniques—error-prone PCR, DNA shuffling, and saturation mutagenesis—within the context of directed evolution for enzyme engineering.

Error-Prone PCR (epPCR)

Principle and Applications

Error-prone PCR (epPCR) constitutes a fundamental random mutagenesis technique that introduces base substitutions throughout an entire gene sequence during PCR amplification under conditions that reduce polymerase fidelity [28] [30]. By leveraging "sloppy" PCR conditions, epPCR generates libraries with point mutations broadly distributed across the target gene, making it particularly valuable for exploring sequence space when structural information is unavailable or when targeting properties influenced by multiple distributed residues [31]. This method has demonstrated success in optimizing various enzyme properties, including the expansion of substrate range and enhancement of activity under non-physiological conditions.

The technique functions by increasing the natural error rate of DNA polymerase through several biochemical manipulations: elevated magnesium concentrations (which stabilize non-complementary base pairs), addition of manganese ions (which further reduce fidelity), use of unbalanced dNTP concentrations, and increased concentrations of error-prone polymerases such as Taq polymerase [32] [30]. Despite its utility, epPCR exhibits significant limitations, including biased mutational spectra favoring transitions (AG, CT) over transversions, limited capacity to generate insertion-deletion mutations (indels), and an inability to produce contiguous mutations within a single codon due to the low probability of multiple base changes occurring at the same position [30]. Additionally, the genetic code's degeneracy means that not all amino acid substitutions are equally accessible through single-base changes, creating inherent biases in the resulting mutant libraries.

Protocol for Error-Prone PCR

Materials and Reagents:

- Template DNA (10-50 ng)

- Taq DNA polymerase or specialized error-prone polymerase (e.g., Genemorph II)

- 10× reaction buffer (commercial or prepared)

- MgCl₂ (25 mM stock)

- MnCl₂ (10 mM stock)

- dNTP mix (commercially available or prepared from individual dNTPs)

- Forward and reverse primers flanking the gene of interest

- PCR purification kit

- Standard agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: Prepare a 50 μL PCR reaction containing:

- 1× reaction buffer

- 100-200 μM of each dNTP

- 3-7 mM MgCl₂ (exact concentration depends on desired mutation rate)

- 0.1-0.5 mM MnCl₂ (optional, for increased mutation frequency)

- 0.5 μM forward primer

- 0.5 μM reverse primer

- 1-2 U/μL Taq DNA polymerase

- 10-50 ng template DNA

Thermal Cycling: Perform PCR amplification using the following cycling parameters:

- Initial denaturation: 95°C for 2 minutes

- 25-35 cycles of:

- Denaturation: 95°C for 30 seconds

- Annealing: 50-60°C for 30 seconds (optimize based on primer Tm)

- Extension: 72°C for 1 minute per kb of template

- Final extension: 72°C for 5-10 minutes

Product Purification: Purify the PCR product using a commercial PCR purification kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Library Construction: Clone the purified PCR product into an appropriate expression vector using standard molecular biology techniques (restriction digestion/ligation or recombination-based cloning).

Critical Parameters:

- Mutation Rate Control: Adjust Mg²⁺ and Mn²⁺ concentrations to achieve desired mutation frequency (typically 1-10 amino acid substitutions per gene).

- Template Quality: Use high-quality, minimal-length template DNA to avoid amplification of non-target regions.

- Cycle Number Optimization: Balance between sufficient product yield and excessive mutation accumulation that could lead to non-functional variants.

Workflow Visualization

DNA Shuffling

Principle and Applications

DNA shuffling represents a more advanced random mutagenesis technique that facilitates in vitro homologous recombination of related DNA sequences, allowing the creation of chimeric genes that combine beneficial mutations from multiple parent sequences [31]. This method extends beyond simple point mutagenesis by enabling the reassortment of mutations throughout the gene, potentially overcoming negative epistasis (where combinations of mutations exhibit non-additive effects) and exploring broader regions of sequence space. DNA shuffling has proven particularly effective in optimizing complex enzyme properties influenced by distributed residues and in engineering metabolic pathways where multiple genes require coordinated optimization.

The fundamental process involves fragmenting a pool of related DNA sequences with DNase I, then reassembling them into full-length chimeric genes through a series of thermocycling steps in the presence of DNA polymerase but without added primers [31]. During the reassembly process, fragments from different parent sequences prime one another based on sequence homology, resulting in crossovers that create novel combinations of mutations. Variants with improved function can then be identified through screening or selection. This method offers significant advantages over purely random mutagenesis approaches by efficiently exploring combinatorial mutation space and potentially accelerating the discovery of synergistic mutation combinations.

Protocol for DNA Shuffling

Materials and Reagents:

- Parent DNA sequences (200-500 ng total)

- DNase I (1 U/μL)

- DNase I reaction buffer

- Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA, 0.5 M, pH 8.0)

- DNA polymerase with proofreading capability (e.g., Pfu, KOD)

- dNTP mix (10 mM each)

- Primers flanking the gene of interest

- Agarose gel electrophoresis equipment

- Gel extraction kit

- PCR purification kit

Procedure:

- DNA Fragmentation:

- Combine 200-500 ng of parent DNA sequences in a 1.5 mL microcentrifuge tube.

- Add 1× DNase I reaction buffer and 0.1-0.5 U DNase I.

- Incubate at 15-25°C for 10-30 minutes to generate random fragments of 50-200 bp.

- Stop the reaction by adding EDTA to 10 mM and heating at 75°C for 10 minutes.

- Purify DNA fragments using a PCR purification kit.

Reassembly PCR:

- Set up a 50 μL reassembly reaction containing:

- 100-200 ng purified DNA fragments

- 0.2 mM dNTPs

- 1× DNA polymerase buffer

- 1-2 U/μL DNA polymerase

- Perform reassembly without primers using the following cycling conditions:

- Initial denaturation: 94°C for 2 minutes