Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Pathways in Engineered Cells: From Biosensor Circuits to Intelligent Biomanufacturing

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic regulation strategies for metabolic pathways in engineered microbial cells, a pivotal advancement in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering.

Dynamic Regulation of Metabolic Pathways in Engineered Cells: From Biosensor Circuits to Intelligent Biomanufacturing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of dynamic regulation strategies for metabolic pathways in engineered microbial cells, a pivotal advancement in synthetic biology and metabolic engineering. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of moving beyond static control to autonomous, real-time metabolic engineering. The scope encompasses the design of genetic circuits using biosensors, CRISPR systems, and quorum sensing, their application in optimizing the production of pharmaceuticals and chemicals, strategies for troubleshooting common pitfalls like metabolic imbalance, and the rigorous validation of these systems against traditional methods. By synthesizing the latest research, this review serves as a guide for implementing dynamic control to build robust, high-performance microbial cell factories for sustainable bioproduction.

The Principles and Evolution of Dynamic Metabolic Control

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why should I consider dynamic control instead of simply overexpressing my pathway of interest? Traditional static overexpression often creates a metabolic burden, redirecting resources away from cell growth and ultimately limiting the final product titer. Dynamic metabolic engineering allows cells to autonomously adjust their metabolic fluxes, managing the trade-off between growth and production. For instance, one study showed that dynamically controlling enzyme levels, as opposed to static knockout, could improve glycerol production by over 30% in a fixed batch time [1].

Q2: My essential gene knockout is lethal. How can dynamic regulation help? Dynamic control allows you to initially express an essential gene to support robust cell growth, then shut it down later to redirect flux toward your desired product. For example, because deleting gltA (citrate synthase) is lethal in E. coli on glucose minimal medium, researchers used a genetic toggle switch to shut off gltA expression after 9 hours of growth, resulting in a more than two-fold improvement in isopropanol yields compared to the wild-type strain [1].

Q3: What are the main components I need to implement a dynamic control system? A functional dynamic control system requires three key components [2]:

- A sensor to detect a specific metabolic state (e.g., a transcriptional regulator that responds to acetyl-phosphate levels).

- A circuit that processes this signal (e.g., a genetic inverter or toggle switch).

- An actuator that executes the control action on the metabolic pathway (e.g., CRISPRi for gene repression or a promoter controlling gene expression).

Q4: I am not getting the expected increase in product titer after implementing a dynamic system. What could be wrong? This is a common challenge. We recommend troubleshooting in the following order:

- Sensor Sensitivity: Verify that your sensor is responding to the intended metabolite within the relevant concentration range in your fermentation conditions.

- Circuit Timing: The timing of the metabolic switch is critical. If it occurs too early, biomass is insufficient; if too late, the production phase is truncated. Use time-course experiments to measure the switch dynamics.

- Actuator Strength: Ensure the actuator (e.g., promoter strength, CRISPRi efficiency) is sufficient to alter the metabolic flux as intended. The required expression level for an enzyme can be strain-dependent and may require combinatorial tuning [1].

Q5: Are there computational tools to help design and model dynamic metabolic control? Yes, several tools can assist you:

- Theoretical modeling: Dynamic Flux Balance Analysis (dFBA) can predict optimal switching times to improve productivity [1].

- Pathway analysis: Software like Pathway Tools (which includes the MetaFlux component) supports the creation and analysis of metabolic flux models [3].

- Machine Learning: For complex pathways, machine learning approaches can predict pathway dynamics from multi-omics time-series data, potentially outperforming classical kinetic models [4].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Low Cell Growth After Implementing Genetic Circuit

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Constitutive Resource Drain. The genetic elements (sensors, circuits) themselves may be placing a constant burden on the host, even before induction.

- Solution: Consider using a tightly regulated circuit that is only activated at the desired time. Also, ensure all genetic parts (e.g., promoters, RBSs) are well-tuned to minimize unnecessary load.

- Cause 2: Leaky Expression from the Actuator. Low-level, unintended expression of your actuator (e.g., early repression of an essential gene) can inhibit growth.

- Solution: Use more stringent promoters or incorporate additional layers of regulation like riboswitches. For CRISPRi, verify the specificity of your gRNA and the absence of basal dCas9 expression.

- Cause 3: Toxicity of Sensor/Actuator Components. Some transcription factors or proteins like dCas9 can be toxic at high levels.

- Solution: Reduce the copy number of the circuit (use a low-copy plasmid or genomic integration) and optimize the expression level of potentially toxic components.

Issue: Dynamic System Fails to Switch or Responds Incorrectly

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause 1: Sensor Not Activated by Intended Metabolite. The intracellular concentration of the trigger metabolite may not reach the sensor's activation threshold.

- Solution: Quantify the intracellular metabolite concentration to confirm it falls within the sensor's dynamic range. You may need to engineer the sensor for different sensitivity or choose a different trigger.

- Cause 2: Signal Delay or Insufficient Signal Strength. The metabolic signal may be too weak or slow to reliably flip the genetic circuit.

- Solution: Incorporate signal amplification modules into your circuit design. Alternatively, use an externally inducible system (e.g., with IPTG) as a proof-of-concept before moving to a fully autonomous one.

- Cause 3: Unanticipated Cross-Talk. Your synthetic circuit might be interacting with the host's native regulatory networks.

- Solution: Perform RNA-seq or ChIP-seq after circuit activation to identify off-target effects. Re-design circuit components (e.g., gRNA sequences, promoter specificity) to minimize cross-talk.

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol 1: Implementing a Quorum Sensing-Controlled Type I CRISPRi (QICi) System

This protocol outlines the steps for using the QICi toolkit for dynamic, cell-density-dependent regulation of metabolic genes in Bacillus subtilis [5].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| PhrQ/RapQ QS System | Core components that sense cell density (acyl-homoserine lactone, AHL) and transduce the signal. |

| Type I CRISPR-Cas System | Acts as the actuator; upon QS activation, it generates a complex that represses transcription of a target gene. |

| Streamlined crRNA Vector | A pre-optimized plasmid for easy insertion of guide RNA sequences targeting your gene of interest (e.g., citZ). |

| Fermentation Medium | For high-titer production, such as in 5-L fed-batch fermentations. |

2. Methodology

Step 1: Clone Target Guide Sequence.

- Design a crRNA sequence complementary to the promoter or coding region of your target metabolic gene (e.g., citZ for citrate synthase).

- Clone this sequence into the streamlined crRNA vector using the provided restriction sites or Golden Gate assembly.

Step 2: Co-transform and Integrate.

- Co-transform the optimized QS component plasmids (PhrQ, RapQ) and the crRNA vector into your production strain of B. subtilis.

- Integrate the system into the genome or maintain it on plasmids, ensuring stable inheritance.

Step 3: Validate System in Shake Flasks.

- Inoculate transformers and grow them while monitoring OD600 (as a proxy for cell density) and your product (e.g., DPA or riboflavin).

- Take samples to measure mRNA levels of the target gene (e.g., via RT-qPCR) to confirm repression occurs at high cell density.

Step 4: Scale-Up to Fed-Batch Fermentation.

- Transfer the validated strain to a bioreactor. The QICi system will autonomously repress the target gene as the culture reaches high density.

- Monitor and harvest the product. The cited study achieved 14.97 g/L of d-pantothenic acid using this method [5].

Protocol 2: Dynamic Regulation Using a Metabolite-Responsive Transcription Factor

This is a generalized protocol for systems that use a native transcriptional regulator (e.g., one that responds to acetyl-phosphate) to control a metabolic enzyme [1].

1. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Sensor Transcription Factor | A protein (e.g., from the Ntr regulon) that changes its DNA-binding state upon binding a key metabolite (e.g., AcP). |

| Promoter Controlled by the TF | The promoter sequence that is activated or repressed by the sensor transcription factor. |

| Gene(s) of Interest | The metabolic enzyme(s) you wish to control dynamically (e.g., pps, idi). |

2. Methodology

Step 1: Identify and Clone the Sensor/Actuator System.

- Identify a transcription factor (TF) that responds to a meaningful metabolic trigger (e.g., acetyl-phosphate for glycolytic flux).

- Clone the promoter sequence controlled by this TF upstream of your metabolic gene(s) of interest, replacing their native promoters.

Step 2: Characterize the Dynamic Response.

- Grow the engineered strain and sample the culture over time.

- Measure the intracellular concentration of the trigger metabolite, the mRNA level of the target gene, and the final product titer (e.g., lycopene).

Step 3: Optimize and Tune.

- If the response is too weak or strong, create a library of promoter variants with different strengths.

- Use high-throughput screening to select clones that achieve the optimal balance between growth and production. The cited example showed an 18-fold improvement in lycopene yield [1].

Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Improvements from Dynamic Metabolic Engineering Strategies

| Controlled Gene / System | Product | Host Organism | Performance Improvement | Key Metric | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucokinase (Glk) via genetic inverter | Gluconate | E. coli | ~30% increase | Titer | [1] |

| Citrate synthase (gltA) via toggle switch | Isopropanol | E. coli | >2-fold improvement | Yield & Titer | [1] |

| Acetyl-Phosphate responsive promoter (pps, idi) | Lycopene | E. coli | 18-fold increase | Yield | [1] |

| Quorum Sensing-CRISPRi (citZ) | d-Pantothenic Acid (DPA) | B. subtilis | 14.97 g/L | Titer (in fed-batch) | [5] |

| Quorum Sensing-CRISPRi (key nodes) | Riboflavin (RF) | B. subtilis | 2.49-fold increase | Production | [5] |

| Theoretical control (Gadkar et al.) | Glycerol | Model | >30% increase | Productivity (in 6h batch) | [1] |

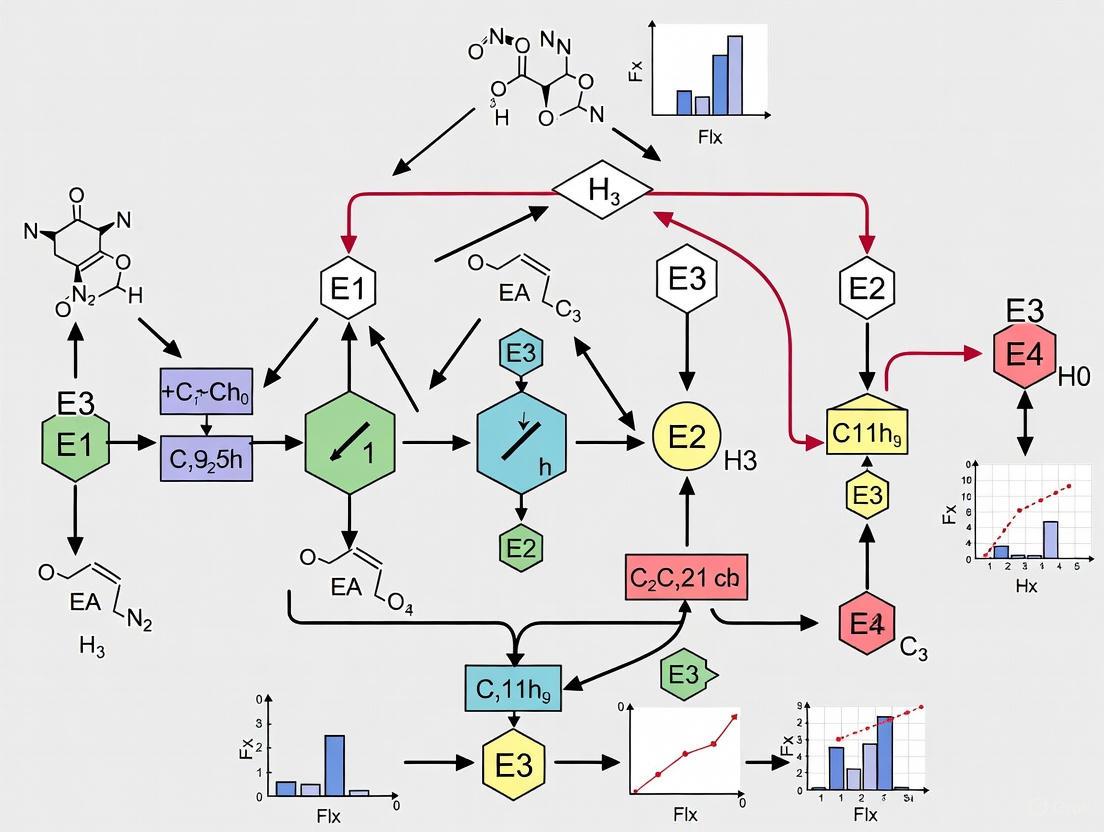

Pathway and Workflow Visualizations

Troubleshooting Guides

Biosensor Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low/No Product Yield [6] | Poor primer design, insufficient cycles, incorrect annealing temperature | Redesign primers; increase cycle number; use temperature gradient to optimize annealing [6]. |

| Non-specific Product [6] | Annealing temperature too low, too much primer, premature replication | Increase annealing temperature incrementally; optimize primer concentration; use hot-start polymerase [6]. |

| Sequence Errors [6] | Low-fidelity polymerase, too many cycles, degraded dNTPs | Use high-fidelity polymerase; reduce cycle number; use fresh, balanced dNTP aliquots [6]. |

| Inaccurate Readings (General Biosensors) [7] | Sensor contamination, faulty calibration, sample interference | Clean sensor with distilled water; calibrate with fresh standard solutions; check sample for interfering substances [7]. |

| Functional Instability (in ELMs) [8] | Host cell death, degradation of genetic components | Optimize host cell vitality and ensure long-term stability of the synthetic gene circuits within the material [8]. |

Genetic Circuit Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Leakiness (Unwanted expression) [9] | Poor promoter specificity, weak transcription factor binding | Engineer transcription factors (e.g., PdhR) for improved sensitivity and reduced baseline expression [9]. |

| Low Dynamic Range [9] | Insufficient signal amplification, inefficient signal transduction | Optimize regulatory components via protein engineering to enhance the ratio between "on" and "off" states [9]. |

| Metabolic Imbalance [9] | Resource competition between circuit and host, toxic intermediate accumulation | Implement dynamic feedback circuits (e.g., metabolite-responsive biosensors) to autonomously regulate flux [9]. |

| Context-Dependent Performance [10] | Interactions with host genome, variable cellular resources | Use orthogonal parts (e.g., CRISPRi, phage repressors) that minimally interfere with native host processes [10]. |

Actuator Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Actuator Not Moving [11] | Incorrect power supply, blown fuse, valve binding | Verify power voltage; check and replace fuses; inspect for mechanical binding [12] [11]. |

| Jerky/Unstable Movement [11] | Mechanical obstructions, worn-out components, improper installation | Remove debris; inspect and replace worn gears or seals; ensure correct alignment [11]. |

| Overheating [11] | Continuous operation, overloading, extreme ambient temperatures | Allow adequate cool-down time; ensure load is within specifications; add external cooling [11]. |

| Unusual Noise [11] | Lack of lubrication, loose or misaligned components | Regularly lubricate moving parts; tighten loose components; replace worn bearings [11]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Biosensors

Q: What are the key characteristics of a biosensor for dynamic metabolic regulation? A: An effective biosensor should have high sensitivity (responds to low metabolite levels), a wide dynamic range (distinguishes between a wide span of concentrations), low leakage (minimal activity in the "off" state), and orthogonality (does not interfere with native host processes) [9].

Q: How can I improve the signal output of my whole-cell biosensor? A: Signal can be enhanced by integrating signal amplification strategies into your genetic circuit design. This can include multi-stage transcriptional cascades or coupling with enzyme-based amplification systems to magnify the detectable output [13].

Genetic Circuits

Q: What are the main classes of regulators used in genetic circuit design? A: The primary classes include:

- DNA-binding proteins (e.g., TetR, LacI homologs): Recruit or block RNA polymerase [10].

- CRISPRi/a: Use a catalytically inactive Cas9 (dCas9) to repress or activate gene transcription [10] [5].

- Invertases (e.g., serine integrases): Permanently flip DNA segments to create memory elements [10].

Q: Why is my genetic circuit behaving differently than expected in the final host? A: Circuit performance is highly sensitive to context, including the host's specific genetic background, growth conditions, and available cellular resources. These factors can alter the effective concentrations of circuit components. Using well-characterized, orthogonal parts and characterizing the circuit in the final application-relevant conditions is crucial [10].

Actuators in Biological Systems

Q: What is a biological actuator, and what does it do? A: In synthetic biology, an actuator is the component that executes a functional output after a biosensor detects a signal. This is often a gene or set of genes that, when expressed, produce a protein that changes the cell's state. Examples include producing a therapeutic protein like an anti-inflammatory cytokine, an enzyme that synthesizes a target compound, or a structural protein that changes the material's properties [8] [9].

Q: The actuator in my engineered living material is not producing the output. What should I check? A: First, verify that the induction signal (e.g., specific chemical, light intensity) is present and at the correct concentration/intensity [8]. Second, check the health of the host cells embedded in the material, as cell death will halt production. Finally, confirm that the actuator gene is correctly integrated into the host genome and that its expression is functional [8].

Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the creation of a biosensor-actuator system that dynamically regulates central metabolism in response to pyruvate levels in E. coli.

1. Principle The transcription factor PdhR naturally represses the pdh operon in the absence of pyruvate. This system is engineered by placing a gene of interest (e.g., for a metabolic enzyme) under the control of the PdhR-responsive promoter (PpdhR). When pyruvate accumulates, it binds PdhR, causing derepression and expression of the actuator gene.

2. Materials

- Strains: E. coli XL1-Blue (for cloning), BW25113 (for production) [9].

- Plasmids: Vector containing the native or engineered PpdhR promoter upstream of a multiple cloning site (MCS).

- Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, kanamycin, chloramphenicol) [9].

- Equipment: Standard molecular biology lab equipment (thermocycler, incubator, spectrophotometer).

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Biosensor Engineering. Perform protein sequence BLAST and site-directed mutagenesis on the native pdhR gene to improve its dynamic properties (sensitivity, leakage) [9].

- Step 2: Circuit Assembly. Clone the engineered pdhR gene and the PpdhR promoter into a plasmid. Insert your target actuator gene (e.g., otsA for trehalose production) into the MCS downstream of PpdhR [9].

- Step 3: Characterization. Transform the constructed plasmid into the production host. Grow cultures and measure actuator output (e.g., fluorescence, product titer) across a range of pyruvate concentrations to generate a dose-response curve and determine dynamic range [9].

- Step 4: Application. Use the characterized strain in a production fermentation. Monitor pyruvate levels and target product formation to validate dynamic pathway regulation [9].

Diagram Title: Pyruvate-Responsive Genetic Circuit Logic

This protocol describes using a cell-density signal (Quorum Sensing) to control a type I CRISPR interference (QICi) system for dynamic metabolic regulation in Bacillus subtilis.

1. Principle As cell density increases, quorum sensing molecules (e.g., PhrQ) accumulate. These molecules inhibit the repressor RapQ, leading to the expression of the CRISPR-associated proteins. A simultaneously expressed crRNA then guides the Cas complex to repress a target metabolic gene (e.g., citZ), redirecting flux toward a desired product.

2. Materials

- Strains: Bacillus subtilis production strain [5].

- Genetic Parts: Genes for the QS components (phrQ, rapQ), type I CRISPR Cas proteins, and expression cassettes for crRNA targeting your gene of interest [5].

- Media: Appropriate fermentation media [5].

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Toolkit Construction. Assemble a modular plasmid system containing the QS module and the CRISPRi module. A streamlined vector for easy crRNA cloning is essential [5].

- Step 2: Component Optimization. Optimize the expression levels of key QS components (PhrQ, RapQ) to maximize the fold-change in CRISPRi repression efficacy at high cell density [5].

- Step 3: Testing. Introduce the QICi system into B. subtilis and measure the repression of a reporter gene linked to the target promoter (e.g., PcitZ) over time in a batch culture [5].

- Step 4: Application. Apply the validated QICi system to dynamically repress a key metabolic node (e.g., citZ for DPA production) during fed-batch fermentation to improve product titers [5].

Diagram Title: Quorum Sensing CRISPRi Metabolic Regulation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Benefit | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Transcription Factors (e.g., PdhR) | Native or engineered proteins that bind specific metabolites and regulate promoter activity. | Core component for building metabolite-responsive biosensors [9]. |

| Orthogonal Promoters | Engineered promoters that respond only to synthetic transcription factors, minimizing crosstalk with the host. | Essential for building predictable, modular genetic circuits in complex cellular environments [10]. |

| CRISPR-dCas9 Systems | Enables programmable repression (CRISPRi) or activation (CRISPRa) of any gene without altering the DNA sequence. | Used for dynamic knockdown of competing metabolic pathways [5]. |

| Hydrogel Matrices (e.g., CsgA, polyacrylamide) | Synthetic materials used to encapsulate and protect engineered living cells, creating robust biosensing platforms. | Used in Engineered Living Materials (ELMs) for environmental monitoring and sustained biosensing [8]. |

| Quorum Sensing Modules | Genetic parts that allow a population of cells to coordinate gene expression based on cell density. | Used to trigger genetic programs, such as CRISPRi, at a specific stage of fermentation [5]. |

Metabolic engineering has enabled the production of a diverse array of valuable chemicals, fuels, and therapeutics using microbial organisms. However, commercial production at industrial scales has often lagged due to the inability of engineered strains to maintain stable performance while meeting stringent titer, rate, and yield (TRY) metrics. These challenges include metabolic burden, improper cofactor balance, accumulation of toxic metabolites, and population heterogeneity in large-scale bioreactors. Dynamic metabolic engineering has emerged as a powerful strategy to address these limitations through genetically encoded control systems that allow cells to autonomously adjust metabolic flux in response to their internal and external environment [14].

This article traces the historical evolution of metabolic engineering through three distinct waves of innovation, culminating in the current era of dynamic regulation. We frame this progression within a technical support context, providing researchers with practical troubleshooting guidance, experimental protocols, and essential resources for implementing dynamic control strategies in their metabolic engineering projects.

The Three Waves of Innovation

Wave 1: Bioprocess and Transgene Optimization

The first wave of innovation focused primarily on extrinsic factors, achieving remarkable improvements in volumetric yield through bioprocess optimization and transgene engineering. These strategies improved protein titer by approximately 100-fold over several decades through media optimization, clonal selection processes, expression vector design, and bioreactor development [15].

Key innovations included high-throughput assays to test genetic elements and media conditions, leveraging tools from robotics to microfluidics. Researchers optimized mRNA copy number, codon usage, and genetic elements to enhance recombinant protein production. This wave established the fundamental toolbox for metabolic engineering but was ultimately limited by its focus on external factors rather than cellular machinery [15].

Table 1: Key Achievements of Wave 1 Innovation

| Innovation Area | Specific Advances | Impact on Production |

|---|---|---|

| Media Optimization | Chemically-defined media formulations | Improved cell density and viability |

| Clonal Selection | High-throughput screening methods | Identification of high-producing clones |

| Expression Vectors | Promoter engineering, codon optimization | Enhanced transgene expression levels |

| Bioprocess Control | Advanced bioreactor designs | Better control over culture conditions |

Wave 2: Targeted Host Cell Engineering

The second wave recognized the limitations of extrinsic optimization and turned toward direct engineering of host cell lines. With the advent of targeted genetic modification technologies, researchers began engineering cellular processes directly associated with protein production, including metabolism and the secretory pathway [15].

This era saw the application of knock-in strategies to study genes that improve protein production, with overexpression of secretory pathway elements helping to identify faulty steps in protein secretion. The development of precise genome editing tools—ZFNs, TALENs, and most significantly CRISPR/Cas9—enabled fine-tuning of cell physiology and precise control over product quality attributes such as glycosylation [15].

Wave 3: Systems-Level Dynamic Control

The third wave represents the current frontier of metabolic engineering: systems-level dynamic control. This approach uses genetically encoded control systems that allow microbes to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to environmental conditions and internal metabolic states [14]. Inspired by natural metabolic control systems, dynamic regulation provides remarkable robustness across different fermentation conditions and improved TRY performance [14].

This wave leverages advances in synthetic biology, systems biology, and control theory to design sophisticated regulatory networks. Key enabling technologies include transcription factor-based biosensors responsive to endogenous and exogenous signals, omics tools for novel promoter discovery, and predictive models for optimizing metabolic networks [16]. The integration of multi-omics data—transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics—with genome-scale models has been particularly transformative, enabling unprecedented insights into cellular pathways influencing production [15].

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Dynamic Regulation Systems

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the main advantages of dynamic metabolic control over traditional constitutive expression?

Dynamic control systems address fundamental challenges in metabolic engineering by automatically adjusting metabolic flux to prevent the accumulation of toxic intermediates, balance cofactor usage, and reduce metabolic burden [14]. Unlike constitutive expression, which forces cells to maintain constant pathway expression regardless of physiological state, dynamic systems can decouple growth and production phases, redirect resources more efficiently, and maintain stability in large-scale bioreactors where environmental heterogeneity can compromise performance [14].

Q2: When should I consider implementing a two-stage process versus continuous metabolic control?

The choice depends on your specific bioprocess objectives and organism. Two-stage processes are particularly beneficial in batch processes where nutrients become limited, as they allow separation of biomass accumulation (stage 1) from product formation (stage 2) [14]. Continuous metabolic control is more suitable for fed-batch and continuous bioprocesses with constant nutritional environments, where maintaining optimal RNA polymerase activity for both growth and production is advantageous [14]. Theoretical modeling suggests that two-stage processes outperform one-stage approaches when glucose uptake rates in the production phase remain above approximately 4 mmol/gDW/h [14].

Q3: How can I identify which metabolic reactions to target for dynamic control in my pathway?

Computational algorithms are available to identify optimal "valves" or control points in metabolic networks. One approach identifies reactions that can be switched between states to achieve near-theoretical maximum yield in different metabolic phases [14]. For many organic products in E. coli, single switchable valves in central metabolism (glycolysis, TCA cycle, oxidative phosphorylation) can effectively decouple production [14]. Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) can also predict maximum theoretical yields and identify potential bottlenecks, though it should be complemented with experimental validation using 13C metabolic flux analysis for precise flux quantification [17].

Q4: What molecular tools are available for implementing dynamic control systems?

A diverse toolbox exists for building dynamic control systems, including:

- Biosensors: Transcription-factor based sensors responsive to metabolites, chemicals, light, temperature, and cell density [16]

- Actuators: Promoters, CRISPRa/i systems, and protein degradation tags

- Genetic circuits: Two-component systems, toggle switches, and oscillators

- Editing tools: CRISPR/Cas9 for precise genome integration of control systems

Recent advances have particularly expanded the repertoire of biosensors for S. cerevisiae, enabling more sophisticated dynamic regulation networks [16].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High Metabolic Burden and Growth Impairment

Observation: Engineered strains grow significantly slower than wild-type, with reduced biomass yield.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Resource competition between heterologous pathway and essential cellular functions.

- Solution: Implement dynamic control to decouple growth and production phases. Use growth-phase responsive promoters or two-stage systems [14].

- Cause: Toxicity from pathway intermediates or products.

- Solution: Incorporate metabolite-responsive biosensors to dynamically regulate flux only when necessary [14].

- Diagnostic Experiment: Measure growth rates and product formation in both constitutive and inducible systems. Perform RNA sequencing to identify stress responses.

Problem: Unstable Production in Scale-Up

Observation: Strains perform well in lab-scale bioreactors but show inconsistent production at larger scales.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Population heterogeneity due to environmental gradients in large bioreactors.

- Solution: Implement autonomous control systems that function at the single-cell level, such as metabolite-responsive genetic circuits [14].

- Cause: Mutational escape leading to non-productive subpopulations.

- Solution: Design dynamic systems with bistable switches exhibiting hysteresis, which maintain the production state even if the inducing signal temporarily decreases [14].

- Diagnostic Experiment: Use flow cytometry to measure population distributions. Track genetic stability through genome sequencing of production and non-production subpopulations.

Problem: Suboptimal Flux Control

Observation: Product titers and yields remain below theoretical maximum despite pathway optimization.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Improperly tuned dynamic response system.

- Solution: Characterize sensor sensitivity and response curves systematically. Modify promoter strength or transcription factor expression to adjust dynamic range [14].

- Cause: Inadequate identification of metabolic valves.

- Solution: Use computational algorithms specifically designed for switchable systems, such as those identifying reactions that can switch between high biomass yield and high product yield states [14].

- Diagnostic Experiment: Perform 13C metabolic flux analysis to quantify intracellular fluxes under different control regimes [17].

Experimental Protocols for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

Protocol: Implementing a Two-Stage Metabolic Switch

Purpose: To decouple cell growth from product formation for improved productivity.

Materials:

- Inducer compound (concentration optimized for your system)

- Appropriate selective media

- Biosensor components (sensor, actuator, and output promoter)

Procedure:

- Design Phase: Identify optimal metabolic valves using computational algorithms (e.g., Venayak et al. 2018 algorithm) [14].

- Strain Construction: Integrate inducible expression system controlling identified valves.

- Characterization Phase:

- Grow cells in appropriate medium under non-inducing conditions (Growth Phase)

- Monitor biomass accumulation (OD600)

- At predetermined transition point (based on biomass, time, or nutrient depletion), add inducer to initiate Production Phase

- Continue monitoring both biomass and product formation

- Optimization: Systematically vary transition point timing to maximize volumetric productivity

Troubleshooting Tips:

- If growth is impaired during production phase, verify that essential metabolism remains functional

- If switching is incomplete, characterize promoter induction kinetics and optimize inducer concentration

- For industrial relevance, test performance in bioreactors with nutrient gradients

Protocol: Metabolic Flux Analysis Using 13C Labeling

Purpose: To quantitatively measure intracellular metabolic fluxes.

Materials:

- 13C-labeled substrate (e.g., [1-13C]glucose)

- Quenching solution (60% aqueous methanol at -40°C)

- Extraction solvent (chloroform:methanol:water mixture)

- GC-MS or LC-MS instrumentation

Procedure:

- Experimental Design: Select appropriate 13C tracer based on pathway of interest.

- Tracer Experiment: Grow cells in minimal medium containing 13C-labeled substrate.

- Sampling and Quenching: Rapidly collect cells and quench metabolism at multiple time points.

- Metabolite Extraction: Extract intracellular metabolites using appropriate solvents.

- Mass Spectrometry Analysis: Measure isotopic labeling patterns in metabolic intermediates.

- Flux Calculation: Use computational software to estimate metabolic fluxes that best fit the measured labeling patterns and extracellular rates [17].

Data Interpretation:

- Compare flux distributions between different strain designs or conditions

- Identify flux limitations or competing pathways

- Validate predictions from computational models like FBA

Table 2: Comparison of Metabolic Flux Analysis Methods

| Method | Principle | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flux Balance Analysis (FBA) | Maximizes objective function (e.g., growth) under stoichiometric constraints | Predicting theoretical yields; Identifying knockout targets | Assumes optimal cellular performance; Poor prediction of engineered strains [17] |

| Metabolic Flux Analysis (MFA) | Fits measured uptake/secretion rates to network model | Quantifying flux under industrial conditions | Requires accurate extracellular measurements [17] |

| 13C Metabolic Flux Analysis (13C-MFA) | Fits isotopic labeling patterns from 13C tracer experiments | Precise flux quantification in central metabolism | Experimentally complex; Limited pathway coverage [17] |

Core Concept: Dynamic Regulation Framework

Dynamic metabolic control systems consist of three core components: sensors that detect metabolic states, processors that determine appropriate responses, and actuators that implement flux adjustments [14]. This framework enables autonomous optimization of metabolic pathways.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Dynamic Metabolic Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Biosensor Components | Transcription-factor based sensors; Riboswitches | Detecting intracellular metabolites and initiating control responses [14] [16] |

| Genetic Editing Tools | CRISPR/Cas9 systems; TALENs; ZFNs | Precise genome integration of dynamic control systems [15] |

| Metabolic Assay Kits | Glucose-6-Phosphate Assay Kit; PEP Assay Kit; ATP Assay Kit | Quantifying metabolite levels and energy charges [17] |

| Flux Analysis Tools | 13C-labeled substrates; Mass spectrometry | Measuring intracellular metabolic fluxes [17] |

| Inducible Systems | Chemical-inducible promoters; Light-sensitive systems; Temperature-sensitive switches | Implementing two-stage processes and external control [14] |

The evolution of metabolic engineering through three distinct waves of innovation has progressively enhanced our ability to engineer microbial cell factories. From initial focus on bioprocess optimization, through targeted genetic modifications, to the current era of systems-level dynamic control, each wave has built upon previous advances while addressing their limitations. Dynamic regulation represents a paradigm shift, moving from static optimization to autonomous, self-regulating systems that maintain optimal performance across varying conditions. As the field continues to advance, integrating more sophisticated biosensors, predictive models, and multi-layer control circuits will further enhance our capability to engineer efficient and robust microbial production systems.

In the field of metabolic engineering, achieving precise dynamic control over metabolic pathways is paramount for optimizing microbial cell factories. Central carbon metabolism presents a particular challenge due to competing pathways that divert key intermediates away from desired products. Pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and NADH emerge as critical metabolic triggers that serve as both indicators of metabolic status and regulators of flux distribution [9]. These molecules sit at the crossroads of major metabolic pathways, making them ideal targets for engineering dynamic control systems in engineered cells [18] [19].

Understanding and manipulating these metabolic triggers enables researchers to overcome the limitations of traditional static regulation methods, which often result in metabolic imbalances, accumulation of intermediates, and reduced cellular viability [9]. By developing biosensors and genetic circuits responsive to these key metabolites, scientists can create self-regulating systems that automatically adjust metabolic fluxes in response to changing intracellular conditions, ultimately leading to more efficient and robust production strains for pharmaceutical and industrial applications.

Troubleshooting Guides

Low Product Yields in Pyruvate-Derived Compound Pathways

Problem: Despite engineering efforts, titers of pyruvate-derived compounds (acetoin, 2,3-butanediol, butanol, L-alanine) remain suboptimal.

Solution: Implement a systematic approach to identify and resolve flux bottlenecks:

Verify pyruvate availability: Measure intracellular pyruvate levels. If low, consider:

Assess cofactor balance: Monitor NADH/NAD+ ratios:

Evaluate pathway-specific issues:

Prevention: Conduct metabolic flux analysis prior to strain engineering to identify native bottlenecks. Implement real-time monitoring using pyruvate-responsive biosensors to maintain optimal pyruvate levels [9].

Inefficient Acetyl-CoA Supply for Biosynthesis

Problem: Acetyl-CoA supply limits production of acetyl-CoA-derived compounds, despite pathway engineering.

Solution: Optimize acetyl-CoA generation from different carbon sources:

Table: Engineering Strategies for Enhanced Acetyl-CoA Supply from Different Carbon Sources

| Carbon Source | Engineering Strategy | Key Genetic Modifications | Theoretical Carbon Recovery | Reported Success |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | Glycolysis optimization | ∆ptsG::glk, ∆galR::zglf, ∆poxB::acs, ∆ldhA, ∆pta | 66.7% | High NAG conversion (98.2%) [21] |

| Acetate | ACK-PTA pathway enhancement | Overexpression of ackA-pta operon | 100% | >80% glutamate conversion [21] |

| Fatty Acids | β-oxidation activation | ∆fadR, constitutive fadD expression | 100% | >80% glutamate conversion [21] |

Additional troubleshooting steps:

- Monitor acetyl-CoA/CoA ratio: High ratios inhibit pyruvate dehydrogenase activity [22] [23]

- Address potential toxicity: For fatty acid utilization, implement controlled feeding strategies to prevent toxicity [21]

- Verify transporter functionality: Ensure efficient uptake of alternative carbon sources [21]

Prevention: Design strains with flexible carbon source utilization capabilities. Implement dynamic regulation to balance acetyl-CoA generation and consumption [9] [21].

NADH/NAD+ Redox Imbalance

Problem: NADH accumulation or deficiency disrupts metabolic flux and cellular health.

Solution: Rebalance cofactor pool through multiple approaches:

For NADH accumulation:

For NADH deficiency:

Diagnostic protocol: Measure NADH/NAD+ ratio and absolute levels at multiple time points during fermentation. Correlate with product formation rates and growth parameters.

Prevention: Incorporate NADH-responsive genetic circuits for autonomous cofactor balancing [9].

Metabolic Burden and Growth Inhibition

Problem: Engineered strains exhibit poor growth or genetic instability due to metabolic burden.

Solution: Implement dynamic control strategies:

- Utilize metabolite-responsive promoters to decouple growth and production phases [9]

- Develop quorum-sensing circuits to activate pathways at high cell density [9]

- Employ CRISPRi for tunable knockdown of competing pathways [9]

Verification: Monitor plasmid retention, growth rates, and expression heterogeneity in populations.

Prevention: Use genomic integration rather than plasmids when possible. Implement automated feedback control in bioreactors.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and NADH particularly effective as metabolic triggers?

These metabolites are ideal as metabolic triggers because they serve as key nodes in central carbon metabolism, with their concentrations reflecting the overall metabolic state of the cell [19]. Pyruvate sits at the junction of glycolysis and the TCA cycle [18] [19]; acetyl-CoA links carbohydrate, fat, and amino acid metabolism [22] [21]; and NADH serves as the primary indicator of redox status [9]. Their levels fluctuate rapidly in response to metabolic changes, making them excellent indicators for dynamic regulation [9].

Q2: How can I monitor these metabolic triggers in real-time during fermentation?

The most advanced approach involves engineering biosensor-based genetic circuits [9]. For pyruvate monitoring, the transcription factor PdhR from E. coli can be engineered into a sensitive biosensor system [9]. For acetyl-CoA, biosensors have been developed using responsive promoters [9]. NADH monitoring can be achieved with engineered transcription factors or NADH-sensitive fluorescent proteins. These biosensors can be linked to reporter genes for real-time monitoring or to regulatory elements for dynamic pathway control [9].

Q3: What are the common pitfalls in engineering pyruvate metabolism?

The most common pitfalls include:

- Creating metabolic bottlenecks by overexpressing pathways without considering cofactor balance [18]

- Inducing redox stress by altering NADH/NAD+ ratios without compensation mechanisms [24]

- Disrupting energy metabolism as pyruvate is crucial for ATP generation [19] [24]

- Triggering regulatory responses as pyruvate metabolism is tightly controlled by allosteric regulation and phosphorylation [19] [23]

Q4: How do I choose between different PDK isoforms for regulating PDC activity?

PDK isoform selection should be based on:

- Tissue/organism specificity: PDK1-4 have different expression patterns and regulatory properties [23] [25]

- Regulatory characteristics: PDK2 has the highest phosphorylation activity on Ser293, while PDK1 specifically phosphorylates Ser232 under acidic conditions [25]

- Response to effectors: Each isoform responds differently to NADH, acetyl-CoA, and pyruvate levels [23] [25]

For metabolic engineering applications, PDK2 is often targeted for improving glucose tolerance, while PDK4 inhibition enhances glucose oxidation [25].

Q5: What engineering strategies work best for enhancing acetyl-CoA supply?

The optimal strategy depends on your carbon source:

Table: Comparison of Acetyl-CoA Engineering Strategies

| Strategy | Mechanism | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDC enhancement | Increased pyruvate to acetyl-CoA conversion | Glucose-based systems | Limited by carbon loss as CO₂ [22] |

| ACS overexpression | Acetate to acetyl-CoA conversion | Acetate-based feedstocks | ATP-intensive [21] |

| ACK-PTA enhancement | Acetate to acetyl-CoA conversion | High-acetate conditions | Higher Km requires acetate accumulation [21] |

| β-oxidation activation | Fatty acid degradation | Lipid/fatty acid feedstocks | Generates abundant NADH/FADH₂ [21] |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Engineering a Pyruvate-Responsive Genetic Circuit

Purpose: To create a dynamic regulation system that responds to intracellular pyruvate levels.

Materials:

- PdhR transcription factor from E. coli [9]

- PdhR-responsive promoter (EcPpdhR) [9]

- Molecular cloning reagents and strains

- Fluorescent reporter proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP)

- Pyruvate analogs for testing response specificity

Procedure:

- Clone the EcPpdhR promoter upstream of your gene of interest

- Co-express PdhR under a constitutive promoter

- Characterize the dynamic range and sensitivity of the circuit using pyruvate analogs

- Optimize circuit components through protein engineering to improve sensitivity and reduce leakage [9]

- Validate the circuit by correlating pyruvate levels with output signal in fermentations

- Implement the circuit for dynamic control of target pathways

Validation: Measure response curves to different pyruvate concentrations. Test specificity against similar metabolites. Verify function in production strains.

Purpose: To enhance acetyl-CoA availability for improved production of acetyl-CoA-derived compounds.

Materials:

- Engineered E. coli strains (e.g., ∆argB, ∆argA for NAG production) [21]

- Alternative carbon sources (acetate, fatty acids)

- N-acetylglutamate synthase from K. setae [21]

- Metabolic inhibitors for pathway validation

- LC-MS for acetyl-CoA quantification

Procedure:

- For glucose-based systems: Implement combined mutations (∆ptsG::glk, ∆galR::zglf, ∆poxB::acs, ∆ldhA, ∆pta) [21]

- For acetate utilization: Engineer the ACK-PTA pathway for efficient acetyl-CoA generation [21]

- For fatty acid utilization: Delete fadR and constitutively express fadD under strong promoters [21]

- Measure acetyl-CoA levels and conversion rates under different conditions

- Correlate acetyl-CoA availability with product formation

- Fine-tune expression using promoter engineering and ribosomal binding site optimization

Validation: Quantify acetyl-CoA pool sizes using LC-MS. Measure carbon conversion rates to target products. Assess growth characteristics and genetic stability.

Metabolic Pathway Visualization

Diagram 1: Central Metabolic Triggers and Pathways. This visualization shows the interconnected roles of pyruvate, acetyl-CoA, and NADH as key regulators in central carbon metabolism. Pyruvate serves as the hub connecting glycolysis to multiple downstream pathways. The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH) regulates flux toward acetyl-CoA and the TCA cycle, while lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and alanine transaminase (ALT) divert pyruvate to alternative fates. NADH generated from the TCA cycle reflects redox status and drives ATP production, creating feedback regulation on metabolic flux.

Diagram 2: Regulatory Control of Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex. This diagram details the complex regulation of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDH/PDC), which controls carbon entry into the TCA cycle. PDH kinases (PDK) inactivate the complex through phosphorylation, while PDH phosphatases (PDP) reverse this inhibition. The regulatory system responds to metabolic triggers including NADH, acetyl-CoA, and pyruvate itself, creating a feedback system that balances energy production with biosynthetic needs.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Research Reagents for Metabolic Trigger Engineering

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biosensor Components | PdhR transcription factor [9] | Pyruvate-responsive genetic circuits | Dynamic range optimization possible through engineering |

| Enzyme Targets | Pyruvate dehydrogenase complex [22] | Controls pyruvate to acetyl-CoA flux | Regulated by phosphorylation/dephosphorylation |

| Regulatory Enzymes | PDK1-4 isoforms [23] [25] | Phosphorylation and inactivation of PDC | Isoform-specific expression and regulation |

| PDP1-2 isoforms [23] | Dephosphorylation and activation of PDC | Ca2+ sensitivity (PDP1) and tissue specificity | |

| Metabolic Modulators | Dichloroacetate (DCA) [25] | PDK inhibitor, shifts metabolism to oxidation | Research tool for studying PDC regulation |

| Pathway Enzymes | N-acetylglutamate synthase (Ks-NAGS) [21] | Acetyl-CoA utilization reporter | High specific activity for efficient conversion |

| Engineering Tools | ACS, ACK-PTA pathway enzymes [21] | Acetyl-CoA generation from acetate | Alternative to glucose-based acetyl-CoA production |

| Analytical Standards | 13C-labeled pyruvate, acetyl-CoA [25] | Metabolic flux analysis | Enables precise tracking of carbon fate |

Table: Performance Metrics of Engineered Strains for Metabolite Production

| Strain | Engineering Strategy | Product | Titer (g/L) | Yield (g/g) | Productivity (g/L/h) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli TBLA-1 | atpA mutation | Pyruvate | 30 | 0.64 | 1.2 | [18] |

| E. coli ALS929 | Multiple deletions (ΔaceEF, Δpfl, etc.) | Pyruvate | 90 | 0.7 | 2.1 | [18] |

| E. coli MG1655 | Reduced aceE expression, Δcra | Pyruvate | 26 | NS | NS | [18] |

| B. subtilis PAR | alsR overexpression | Acetoin | 41.5 | 0.35 | 0.43 | [18] |

| B. subtilis JNA 3-10 BMN | ΔbdhA, ΔyodC | Acetoin | 56.7 | 0.38 | 0.64 | [18] |

| S. cerevisiae YHI030 | ΔPDC, als/ald overexpression | 2,3-BD | 81 | 0.27 | NS | [18] |

| B. subtilis | ALS/ALDC expression, ΔldhA | 2,3-BD | 102.6 | NS | 0.93 | [18] |

| E. coli 0019 | Ks-NAGS expression, acetyl-CoA engineering | NAG | ~28.5* | High conversion | 6.25 mmol/L/h | [21] |

Note: NAG titer calculated from molar concentration (17.89 mM) reported in [21]; NS = Not Specified

Foundational Concepts: Core Control Logics in Dynamic Regulation

What are the fundamental control logics used in dynamic metabolic engineering? Dynamic metabolic engineering utilizes control logics to enable engineered cells to autonomously adjust their metabolic flux in response to changing internal and external conditions [2]. The three primary logics are:

- Feedback Control: A system that measures the actual output (e.g., metabolite concentration) and compares it to a desired setpoint to calculate an error, which is then used to correct the system and minimize that error [26] [27]. It continuously reacts to disturbances after they have affected the system.

- Feedforward Control: A system that predicts the effect of a measured disturbance (e.g., substrate level) before it impacts the output and applies a corrective action in advance [28] [29]. It requires a mathematical model of the process to be effective.

- Oscillatory Systems: Systems that exhibit periodic, self-sustaining cycles. In electronics, they are often created using positive feedback where the output signal is fed back to the input in a way that maintains continuous oscillation [27]. In metabolic engineering, synthetic oscillators can be designed to create rhythmic gene expression, providing a time-based control logic [30].

How do negative and positive feedback differ in function and outcome? The type of feedback is defined by the effect it has on the system's output and stability [26] [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Negative and Positive Feedback

| Feature | Negative Feedback | Positive Feedback |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism | A change in a variable triggers an opposite change [26]. | A change in a variable triggers an amplifying, similar change [26]. |

| System Effect | Reduces gain, promotes stability, and rejects disturbances [27]. | Increases gain, can lead to instability, and drives systems to saturation or oscillation [27]. |

| Common Uses | Homeostasis, amplifiers with stable operation, cruise control [26] [27]. | Bistable switches (e.g., decision-making circuits), oscillators, hysteresis [27]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Implementing Control Logics

FAQ 1: My feedback-controlled system is unstable and oscillates. What could be the cause? Oscillation in a feedback loop often arises from excessive time delays or an overly aggressive controller gain.

- Potential Cause 1: Significant delays between sensing a metabolite and the resulting change in gene expression. The controller's corrective action arrives too late, overshooting the setpoint and causing a cycle of over- and under-correction.

- Solution: Implement a feedforward element if the major disturbance (e.g., substrate influx) can be measured. This allows the system to anticipate and preempt the disturbance, reducing reliance on the slower feedback loop [28] [29]. Alternatively, fine-tune the feedback controller's parameters to be less aggressive.

- Potential Cause 2: Positive feedback is unintentionally dominating the system dynamics.

FAQ 2: When should I choose a feedforward control strategy over feedback for my pathway? Feedforward control is most beneficial when a major, measurable disturbance affects the system and a predictive model is available.

- Choose Feedforward when:

- Stick with or Combine with Feedback when:

- The major disturbances are unmeasurable or unpredictable [29].

- Your model of the process is inaccurate, as feedforward performance is entirely model-dependent [28].

- For robust performance, the best approach is often a combined feedforward-feedback (FF-FB) system, where feedforward handles predictable disturbances and feedback corrects for remaining errors and model inaccuracies [29] [32].

FAQ 3: I am designing a synthetic oscillator for rhythmic control. What is a fundamental design principle? A core principle for creating a genetic oscillator is to incorporate a time-delayed negative feedback loop [30] [27]. The system must have sufficient delay between the expression of a gene and the point at which its product represses its own expression. This delay prevents the system from settling into a steady state and instead causes it to rhythmically oscillate between high and low expression states.

FAQ 4: How can I linearize a non-linear system like a bioreactor for more predictable control? Use a non-linear feedforward controller to cancel out the known non-linearity [32]. For example, if cell growth follows a known non-linear model, the feedforward controller can use the inverse of that model to calculate the substrate feed rate. This effectively "linearizes" the system from the controller's perspective, making it easier for a standard feedback controller (e.g., a PID controller) to manage the now-more-linear process and reject any unmodeled disturbances.

Experimental Protocols & Reagents

Protocol: Implementing a Combined Feedforward-Feedback Controller for a Model Metabolic Pathway

This protocol outlines the steps for designing a control system that regulates the output of a target metabolite in E. coli, where glucose concentration is a key disturbance.

- System Identification & Modeling:

- Characterize the relationship between the disturbance (glucose influx) and the output (metabolite titer). This involves running chemostat experiments at varying glucose feed rates and measuring the resulting steady-state metabolite levels.

- Develop a mathematical model (e.g., a transfer function or a kinetic model) that describes this relationship. This model will form the basis of your feedforward controller [29].

- Feedforward Controller Implementation:

- The perfect feedforward controller is the inverse of the process model identified in Step 1 [29]. Program this control law into your bioreactor's control software.

- Connect a real-time glucose sensor to the controller. The controller will now use the glucose measurement and the inverse model to calculate the required actuator output (e.g., base pump rate for pH adjustment or inducer pump rate for gene expression) to preemptively compensate for glucose fluctuations.

- Feedback Controller Tuning:

- With the feedforward controller active, implement a feedback controller (e.g., a PID controller) that measures the actual metabolite titer (via an off-line analyzer or a proxy sensor).

- The feedback controller's role is to correct for any residual error due to model inaccuracies in the feedforward controller or unmeasured disturbances. Tune the PID parameters (Kp, Ki, Kd) to achieve a stable and responsive correction without oscillation [32].

- System Validation:

- Test the combined system by introducing a known step-change in glucose concentration. Monitor the metabolite titer.

- A well-tuned FF-FB system will show minimal deviation from the setpoint compared to a system using only feedback control, as the feedforward action immediately counters the glucose change.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Control Circuit Implementation

| Research Reagent | Function in Control System | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Constitutive Promoters | Serves as a constant signal source or setpoint generator. | Providing a baseline input to a feedforward controller [30]. |

| Inducible Promoters (e.g., aTc, Ara) | Acts as the system's actuator, receiving the control signal to manipulate pathway flux. | Implementing the controller's output command to regulate gene expression [2]. |

| Transcriptional Repressors (e.g., LacI, TetR) | Functions as the signal processing unit, implementing logic operations like inversion. | Building a negative feedback loop where a metabolite represses its own synthesis [26] [30]. |

| Riboswitches / Allosteric Transcription Factors | Serves as the sensor, detecting the internal state of the cell (e.g., metabolite level). | Translating the concentration of a target metabolite into a regulatory signal for feedback control [2]. |

| Fluorescent Reporter Proteins (e.g., GFP, RFP) | Provides a measurable output for system characterization and controller tuning. | Serving as a proxy to monitor the dynamics of a synthetic circuit in real-time [30]. |

A Toolkit for Implementation: Biosensors, CRISPR, and Quorum Sensing Circuits

The pursuit of advanced microbial cell factories for bioproduction is often constrained by inherent conflicts between cell growth and product synthesis. Static engineering approaches, such as gene knockouts and constitutive pathway overexpression, frequently disrupt cellular homeostasis, leading to redox imbalances and toxic intermediate accumulation [33]. Synthetic genetic circuits have emerged as powerful tools to overcome these limitations by enabling dynamic modulation of gene expression and metabolic flux in response to intracellular conditions [33]. Within this paradigm, metabolite-responsive biosensors represent a groundbreaking technology that allows engineered cells to autonomously regulate their metabolic processes based on the concentrations of key intermediates.

Pyruvate occupies a crucial position in central carbon metabolism, serving as the key node connecting glycolysis with the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle and supplying essential carbon skeletons and energy for both cell growth and product synthesis [33]. The Escherichia coli-derived transcription factor PdhR (Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Complex Regulator) functions as a pyruvate-responsive repressor and has been successfully harnessed for engineering dynamic control systems in both prokaryotic and eukaryotic chassis [33]. This technical resource provides comprehensive guidance for researchers implementing PdhR-based biosensors, with detailed troubleshooting protocols, experimental methodologies, and reagent solutions to address common challenges in metabolic engineering applications.

Technical FAQ: PdhR Biosensor Implementation

Q1: What are the key functional characteristics of the native PdhR protein and its engineered variants?

The PdhR protein is a member of the GntR family of transcription factors that senses intracellular pyruvate levels through direct binding [34]. In its apo form (without pyruvate), PdhR binds to specific palindromic operator sequences known as PdhR boxes (consensus: ATTGGTNNNACCAAT) and represses transcription of target operons [34]. Pyruvate binding induces a conformational change that abolishes DNA binding, thereby derepressing transcription under high pyruvate conditions [34]. This fundamental mechanism has been exploited to create various pyruvate-responsive genetic circuits, with engineered variants showing expanded dynamic range and modified sensitivity through directed evolution and optimization for heterologous hosts [33].

Q2: What specific experimental challenges might researchers encounter when implementing PdhR biosensors in eukaryotic systems?

The implementation of PdhR-based circuits in eukaryotic chassis such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae presents several technical challenges. Eukaryotic cells exhibit strict subcellular compartmentalization, requiring the addition of nuclear localization signals (NLS) to ensure proper translocation of the bacterial transcription factor into the nucleus where it must function [33]. Additionally, transmembrane transport limitations for pyruvate in eukaryotic systems may necessitate engineering of indirect induction systems or modification of pyruvate transport mechanisms to ensure proper biosensor function [33]. Signal cross-talk with endogenous regulatory networks and differences in chromosomal context for integrated circuits further complicate implementation in eukaryotic hosts.

Q3: How can researchers quantify and account for pH sensitivity in fluorescent pyruvate biosensors?

Many single fluorescent protein-based pyruvate sensors, including those derived from PdhR, exhibit significant pH sensitivity that can confound intracellular measurements [35] [36]. This limitation can be addressed through several experimental approaches: (1) conducting parallel measurements with a pH probe to correct for pH-dependent signal changes; (2) utilizing ratiometric measurements by exciting the sensor at its isosbestic point (e.g., 435 nm for PyronicSF) where fluorescence is pH-independent [35]; or (3) employing control experiments with a non-responsive "dead" sensor variant (Dead-PyronicSF) that maintains pH sensitivity but lacks pyruvate response, allowing specific quantification of pH effects [35].

Q4: What factors contribute to metabolic fluctuations that might affect PdhR biosensor readings?

Single-cell analyses have revealed that steplike exposure of starved E. coli cells to glycolytic carbon sources elicits large periodic fluctuations in intracellular pyruvate concentrations with periods of approximately 100 seconds [37]. These metabolic oscillations emerge from the inherent stochasticity and dynamic instability of the metabolic network, particularly biochemical reactions around the pyruvate node, and are consistent with predicted oscillatory dynamics resulting from allosteric enzyme regulation in glycolysis [37]. Such natural fluctuations can propagate to other cellular processes and may lead to temporal heterogeneity in biosensor readings within populations, necessitating appropriate experimental design and data interpretation strategies.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting PdhR Biosensor Performance Issues

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Suboptimal sensor dynamic range; Incorrect subcellular localization; Poor expression | Engineer improved variants [35]; Verify targeting sequences [33]; Optimize expression levels |

| Incomplete Response to Pyruvate | Limited pyruvate transport; Sensor saturation; Incorrect calibration | Assess transporter expression [33]; Verify sensor ( K_D ) [36]; Perform in situ calibration |

| High Background Fluorescence | Sensor mistargeting; Non-specific binding; Cellular autofluorescence | Use organelle-specific markers [35]; Test ligand specificity [36]; Include proper controls |

| Inconsistent Population Response | Metabolic heterogeneity; Cell cycle effects; Stochastic expression | Analyze single cells [37]; Synchronize cultures; Use homogeneous expression systems |

| Poor Dynamic Regulation | Non-optimal promoter strength; Insufficient metabolic push/pull | Engineer promoter libraries [33]; Balance pathway expression [38] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Characteristics of Pyruvate Biosensors

| Biosensor Name | Type | EC₅₀ (μM) | Dynamic Range | Key Applications | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PyronicSF | Single FP (cpGFP) | 480 | ~250% increase | Subcellular pyruvate quantitation; Mitochondrial transport | [35] |

| Green Pegassos | Single FP (GFP) | 70 | 3.3-fold increase | Live cell imaging; Metabolite interplay studies | [36] |

| FRET Sensor | FRET (CFP/YFP) | 400 (in vitro) 6 (cellular) | Ratio change | Single-cell pyruvate dynamics; Metabolic oscillations | [37] |

| Pyronic | FRET | 107 | ~128% increase (1mM pyr) | Cytosolic pyruvate measurements; Organismal studies | [36] |

Experimental Protocols: Key Methodologies for PdhR Biosensor Implementation

Protocol: Mitochondrial Pyruvate Concentration Measurement Using Mito-PyronicSF

Background: The PyronicSF sensor represents a significantly improved GFP-based pyruvate sensor with enhanced dynamic range (~250% fluorescence increase) compared to earlier versions, enabling precise quantification of subcellular pyruvate distributions [35].

Procedure:

- Sensor Expression: Target PyronicSF to the mitochondrial matrix using the destination sequence of cytochrome oxidase subunit VIII. Verify correct targeting by colocalization with mitochondrial markers (e.g., TMRM, mito-mCherry) [35].

- Calibration: Perform a one-point calibration by forcing nominal zero cytosolic pyruvate through MCT-accelerated exchange with extracellular lactate [35].

- Image Acquisition: Acquire fluorescence images using standard 488 nm laser excitation on a confocal microscope. For ratiometric measurements capable of correcting for pH effects, additionally excite at the isosbestic point (435 nm) [35].

- Quantitative Analysis: Calculate mitochondrial pyruvate concentration based on the established dose-response curve of the purified sensor (( K_D ) = 480 μM). For absolute quantification, normalize signals to the zero-pyruvate condition established during calibration [35].

Technical Notes: In cells exhibiting inefficient mitochondrial targeting, a biphasic response to pyruvate loading may be observed, with a rapid cytosolic component followed by slower mitochondrial accumulation. For specific mitochondrial measurements, use only cells without significant cytosolic sensor leakage [35].

Protocol: Implementation of PdhR Genetic Circuit in Eukaryotic Chassis

Background: The functional transfer of prokaryotic transcription factors to eukaryotic systems requires optimization to address challenges including nuclear localization, heterologous DNA binding, and metabolic compartmentalization [33].

Procedure:

- Circuit Design: Clone the PdhR coding sequence downstream of a constitutive yeast promoter. Fuse a nuclear localization signal (NLS) peptide to the PdhR sequence to ensure nuclear import [33].

- Promoter Engineering: Modify native PdhR-regulated promoters (e.g., pdhO site) for functionality in the eukaryotic host while maintaining PdhR recognition specificity [33].

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the engineered circuit into Saccharomyces cerevisiae (e.g., BY4741 background) and select on appropriate dropout media (e.g., SC-Ura) [33].

- Functional Validation: Test pyruvate responsiveness using a GFP reporter gene. Characterize circuit dynamics by measuring fluorescence changes in response to varying pyruvate concentrations in minimal medium [33].

- Application: Implement the validated circuit for dynamic pathway regulation by placing target metabolic genes under control of the PdhR-responsive promoter [33].

Technical Notes: For Pdc-negative S. cerevisiae strains (which accumulate pyruvate), optimize the fermentation medium composition to maintain sensor responsiveness: 20 g/L glucose, 20 g/L amino acids, and appropriate supplements [33].

Protocol: Measurement of MPC Activity Using Mito-PyronicSF

Background: The mitochondrial pyruvate carrier (MPC) plays a critical role in controlling pyruvate flux into mitochondria, and its activity can be quantitatively assessed using targeted pyruvate sensors [35].

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Express mito-PyronicSF in cultured astrocytes or other appropriate cell types. Use lipid transfection or adenoviral transduction for sensor delivery [35].

- Pharmacological Modulation: Expose cells to specific MPC inhibitors: UK-5099 (1-10 μM) or rosiglitazone (10-100 μM) to assess inhibitor sensitivity [35].

- Pyruvate Loading: Apply extracellular pyruvate (1-10 mM) while monitoring fluorescence changes in mitochondrial regions.

- Kinetic Analysis: Quantify the initial rate of pyruvate accumulation in mitochondria following pyruvate application. Compare rates between inhibitor-treated and control conditions.

- Data Interpretation: Calculate percentage inhibition relative to untreated controls. Typical inhibition values are 69% for UK-5099 and 67% for rosiglitazone [35].

Technical Notes: This protocol is amenable to screening for novel MPC modulators. The incomplete inhibition observed with specific MPC blockers may reflect variations in MPC subunit composition or the presence of alternative pyruvate transport routes [35].

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for PdhR Biosensor Studies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for PdhR Biosensor Implementation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| PdhR-Based Sensors | PyronicSF, Green Pegassos, FRET sensor [37] | Pyruvate detection and quantification | Varying ( K_D ) values suit different concentration ranges |

| Expression Systems | pGRP (RFP/GFP vector), pET28(a), pINTts | Sensor expression and reporter assays | Eukaryotic optimization requires NLS tagging [33] |

| MPC Inhibitors | UK-5099, Rosiglitazone | Mitochondrial transport studies | Demonstrate 67-69% inhibition efficacy [35] |

| Reference Sensors | Dead-PyronicSF, pH sensors, Mito-mCherry | Signal normalization and controls | Essential for accounting for pH effects and localization [35] |

| Cell Lines/Strains | HEK293T, HeLa, E. coli MG1655, S. cerevisiae BY4741 | Experimental chassis | Include Pdc-negative yeast for pyruvate accumulation [33] |

| Culture Media | M9 minimal medium, SC dropout media, Modified Ringer's buffer | Controlled cultivation conditions | Specific formulations maintain sensor responsiveness [33] |

Metabolic Pathway Visualization

Figure 1: PdhR Regulatory Network in Central Energy Metabolism. The diagram illustrates how PdhR senses intracellular pyruvate and coordinately regulates the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and respiratory chain components. Under high pyruvate conditions, PdhR undergoes a conformational change that derepresses its target operons, creating a coordinated metabolic response [34].

Figure 2: Implementation Strategy for PdhR-Based Genetic Circuits. This workflow outlines the key steps for implementing functional PdhR biosensors in heterologous hosts, particularly highlighting the additional considerations required for eukaryotic chassis, including nuclear localization signals (NLS), promoter optimization, and addressing subcellular compartmentalization of metabolites [33].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on QS Circuit Fundamentals

Q1: What is the core principle behind using QS for pathway-independent control in metabolic engineering?

Quorum Sensing (QS) is a cell-cell communication process where bacteria produce, secrete, and detect diffusible signaling molecules called autoinducers. The concentration of these molecules correlates with cell density, allowing the population to collectively regulate gene expression [39]. Pathway-independent control leverages this natural mechanism to create genetic circuits that respond to cell density, rather than a specific intracellular metabolite. This allows for dynamic regulation of metabolic fluxes based on the population's growth phase, enabling autonomous switching between "growth mode" and "production mode" without the need for external inducers [40]. This is particularly valuable for controlling essential genes or pathways where static knockout would be lethal [40].

Q2: What are the main types of QS systems, and which is most suitable for a pathway-independent application in E. coli?

The primary types of QS systems are based on their signaling molecules:

- Acyl-Homoserine Lactones (AHLs): Used by Gram-negative bacteria. Systems like LuxI/LuxR or EsaI/EsaR are well-characterized and commonly ported into engineered E. coli [39] [40].

- Autoinducing Peptides (AIPs): Used by Gram-positive bacteria [39].

- Autoinducer 2 (AI-2) and Indole: Used for interspecies communication [39].

For pathway-independent control in the common chassis E. coli, AHL-based systems are the most suitable. Their components are readily engineered, and they function reliably in Gram-negative backgrounds. The Esa system from Pantoea stewartii, for instance, has been successfully used to create a pathway-independent circuit for dynamic metabolic engineering [40].

Q3: Why is a pathway-independent QS circuit sometimes preferable to a pathway-specific one?

Pathway-specific controls rely on sensors for particular intermediates or byproducts, making them difficult to design and limiting their application to that specific pathway [39]. In contrast, pathway-independent QS circuits offer key advantages:

- Broad Applicability: The same core circuit can be used to control different genes and pathways by simply swapping the output gene [40].

- Management of Growth-Production Trade-offs: They autonomously delay production until a high cell density is reached, avoiding premature burdens on cell growth [1] [40].

- Industrial Scalability: As they are auto-inducing, they eliminate the cost and regulatory hurdles associated with adding chemical inducers during large-scale fermentation [40].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting QS Circuit Performance

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Insufficient or no circuit activation | Low signal molecule (AHL) production; poor receiver protein expression; weak promoter driving circuit components. | Systematically strengthen the promoter and RBS for the AHL synthase (e.g., EsaI) and the transcriptional regulator (e.g., EsaR); verify AHL presence using a biosensor strain. | [40] |

| Circuit activates too early or too late | Improper tuning of the AHL accumulation rate relative to the growth rate of the culture. | Fine-tune the expression level of the AHL synthase (EsaI) by constructing a library of promoter-RBS combinations to find the optimal switching cell density. | [40] |

| High basal expression in the "OFF" state | Leaky expression from the QS-controlled promoter; insufficient degradation of the target protein. | Add a degradation tag (e.g., SsrA/LAA tag) to the C-terminus of the target protein to shorten its half-life and ensure rapid clearance after circuit activation. | [40] |

| High metabolic burden & genetic instability | Over-expression of circuit components; plasmid-based expression systems. | Genomically integrate all circuit components to reduce copy number and burden; use well-characterized, low-strength parts for constitutive expression. | [40] |

| Cheater mutations evading population control | Mutations that inactivate the QS circuit arise and are selected for because they avoid growth inhibition. | Implement a paradoxical control architecture where the QS signal stimulates both growth and death, actively selecting against signal-blind cheater mutants. | [41] |

Core Experimental Workflow for Circuit Construction

The diagram below outlines the key steps for building and implementing a pathway-independent QS circuit.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Implementing a QS Circuit

| Item | Function / Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| QS System Parts | Genetic components for signal sending and receiving. | EsaI/EsaR system from Pantoea stewartii: EsaI (AHL synthase), EsaR (transcriptional regulator), PesaS (promoter). A point mutant, EsaRI70V, can be used to create an AHL-repressed system [40]. |

| Tunable Expression Parts | To fine-tune the expression level of circuit components. | Pre-characterized promoter and RBS libraries (e.g., from the BioFAB library) to scan a wide expression space for the AHL synthase and achieve desired switching dynamics [40] [42]. |