Enzyme Immobilization Supports: A Comparative Analysis of Efficiency for Advanced Biocatalysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the efficiency of various enzyme immobilization supports, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences.

Enzyme Immobilization Supports: A Comparative Analysis of Efficiency for Advanced Biocatalysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the efficiency of various enzyme immobilization supports, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical sciences. It explores the fundamental principles of immobilization, evaluates traditional and novel nanomaterial-based supports, and details their methodological applications in biosensing and biotransformation. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to overcome common challenges like enzyme leaching and mass transfer limitations. Finally, it establishes a framework for the validation and comparative assessment of support efficiency, synthesizing key performance indicators to guide the selection of optimal immobilization systems for robust and sustainable biocatalytic processes.

Understanding Enzyme Immobilization: Principles, Supports, and Strategic Importance

Enzyme immobilization has evolved into a fundamental engineering strategy within industrial biocatalysis, directly addressing the core limitations that hinder the widespread application of biological catalysts. In their free form, enzymes often exhibit low stability under industrial conditions, sensitivity to environmental factors like pH and temperature, and difficulties in recovery and reuse, which collectively increase operational costs and limit process efficiency [1] [2]. Immobilization, defined as the confinement of an enzyme to a solid support or within a distinct phase, provides a powerful solution to these challenges [1].

The primary impetus for immobilization stems from its ability to significantly enhance operational stability, facilitate easy separation and reusability of biocatalysts, and ultimately reduce the overall cost of enzymatic processes, making them commercially viable [3] [4]. This is particularly crucial in sectors like pharmaceuticals, food processing, and bioenergy, where precision, sustainability, and cost-effectiveness are paramount. By converting enzymes into a heterogeneous catalyst form, immobilization bridges the gap between the exceptional catalytic efficiency of enzymes and the rigorous demands of industrial manufacturing, enabling their use in continuous flow reactors and repeated batch operations [1] [4]. This guide objectively compares the performance of various enzyme immobilization supports and methodologies, providing experimental data and protocols to inform research and development.

Core Advantages: Why Immobilize Enzymes?

The transition from free to immobilized enzymes is driven by three interconnected advantages that directly impact process efficiency and economics.

Enhanced Stability and Robustness

Immobilization significantly improves an enzyme's resistance to denaturation caused by exposure to harsh conditions such as extreme pH, high temperatures, organic solvents, and impurities [3]. This stabilization occurs through multiple mechanisms. Multipoint covalent bonding, for instance, rigidifies the enzyme's structure, preventing unfolding and denaturation [3]. A recent study demonstrated that chitinase immobilized on sodium alginate-modified rice husk beads (SA-mRHP) exhibited superior pH, temperature, and storage stability compared to its free counterpart [5]. Such enhanced durability allows enzymes to function effectively over longer periods and in more challenging reaction environments.

Reusability and Simplified Downstream Processing

A key economic driver for immobilization is enzyme reusability. By localizing enzymes on a solid support, they can be easily separated from reaction mixtures—containing substrates and products—via simple filtration or centrifugation [3] [1]. This capability for multiple reaction cycles drastically reduces enzyme consumption and cost per unit of product. For example, immobilized SmChiA on SA-mRHP beads demonstrated remarkable durability, maintaining full activity after 22 reuse cycles, a feat impossible for free enzymes [5]. Furthermore, this easy separation minimizes product contamination by the enzyme, simplifying downstream purification processes [3].

Improved Cost-Effectiveness of Industrial Processes

The combined benefits of enhanced stability and reusability directly translate to superior cost-effectiveness. Although immobilization adds an initial cost for support materials and processing, this is offset by reduced enzyme consumption, lower catalyst replacement frequency, and the potential for continuous processing [4]. Immobilization reduces the need for extensive downstream processing, making enzymatic processes more reliable and efficient [1]. In biorefineries, immobilization has been shown to reduce biocatalyst costs by more than 60% through enhanced durability, positioning it as a cornerstone for sustainable industrial biotechnology [4].

Comparative Analysis of Immobilization Supports and Techniques

The performance of an immobilized enzyme is profoundly influenced by the choice of support material and the immobilization technique. The table below provides a structured comparison of common support types, their inherent properties, and performance outcomes.

Table 1: Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Supports and Techniques

| Support Material / Technique | Key Characteristics | Immobilization Method | Reported Performance Data | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate-Modified Rice Husk Beads (SA-mRHP) [5] | Biodegradable, biocompatible, cost-effective; modified with citric acid to increase carboxylic groups. | Covalent binding using EDAC crosslinker. | - Retained full activity after 22 reuse cycles.- Higher stability over free enzyme across pH/temperature.- ( Km ): 3.33 mg/mL; ( V{max} ): 4.32 U/mg protein/min. | High enzyme loading, low-cost support, excellent operational stability. | Requires chemical activation; potential for mass transfer limitations. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) [6] | Green support, structural stability, non-toxic, large surface area, sourced from waste. | Covalent binding via APTES silanization & glutaraldehyde activation. | Promising stability and reusability over multiple reaction cycles for LbTDC and TsRTA enzymes. | Fulfills circular economy principles, biocompatible, easily modified. | Relatively complex derivatization process. |

| Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [7] | Carrier-free; enzymes precipitated and cross-linked with bifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde). | Cross-linking. | - 10x more stable than free enzymes under same conditions.- ~60% activity retained after 7 cycles (HRP example). | High enzyme concentration, no expensive carrier, good stability. | Potential activity loss during precipitation; diffusion limitations. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [7] | Porous crystalline polymers; tunable pore environments, high surface area. | Pore adsorption, in-situ encapsulation. | Encapsulates more biocatalyst per support unit mass than other nanoparticles. | Prevents enzyme deactivation under hostile conditions; enhances mass transfer. | Synthesis complexity; potential cost concerns. |

| Adsorption on Inorganic Carriers (e.g., Silicas, Titania) [3] | High surface area, eco-friendly, good water-holding capacity. | Physical adsorption via weak forces (van der Waals, hydrogen bonds). | Simple and fast immobilization; high activity retention due to no chemical modification. | Simple, reversible, low-cost, preserves native enzyme structure. | Enzyme leakage due to weak binding (e.g., at high ionic strength). |

The selection of an optimal support is highly application-specific. Inorganic carriers like silicas and natural polymers like alginate and chitosan are prized for their cost-effectiveness and biocompatibility [3] [8]. In contrast, advanced materials like Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) and carrier-free systems like CLEAs offer unique advantages in stability and enzyme loading, albeit sometimes with greater synthetic complexity or cost [7].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Support Preparation and Evaluation

To ensure reproducibility and enable objective comparison between different immobilization strategies, detailed experimental protocols are essential. The following workflow and descriptions outline key methodologies.

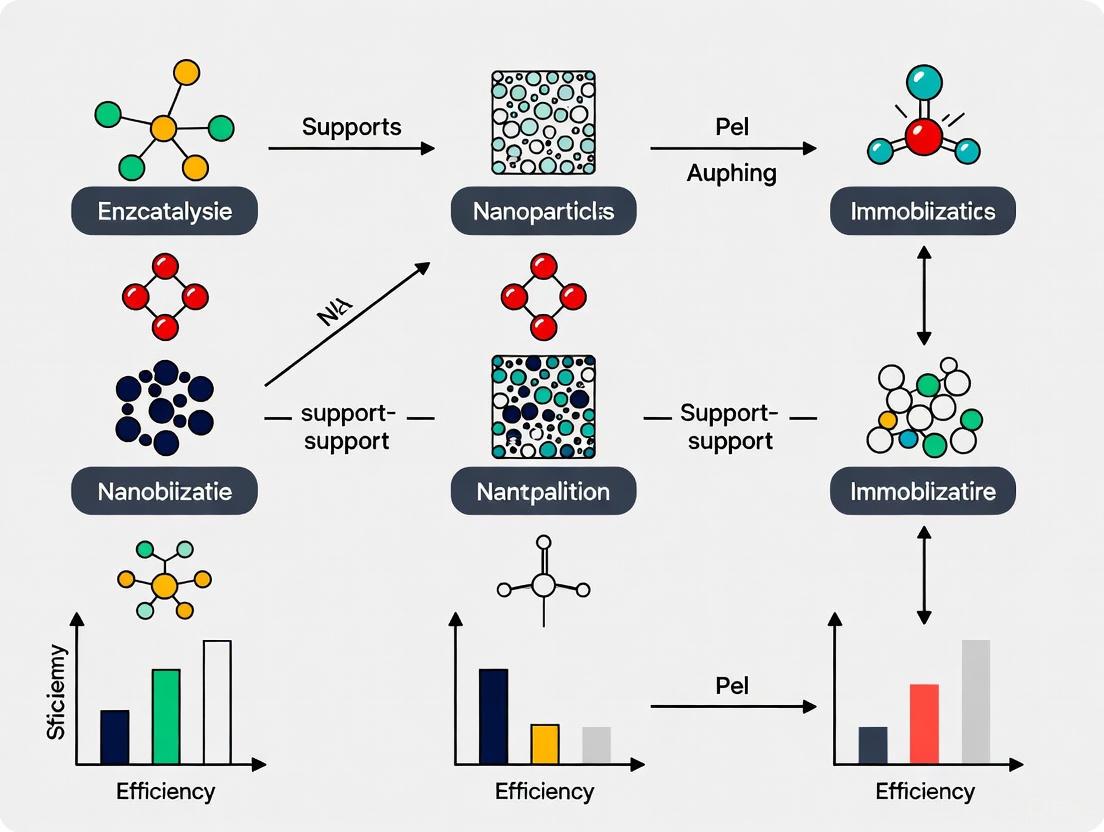

Diagram 1: Immobilized Enzyme Experiment Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key stages in preparing, creating, and testing an immobilized biocatalyst, from support preparation to final performance evaluation.

Support Preparation and Modification Protocol

The preparation of the support matrix is a critical first step in creating an effective immobilized biocatalyst.

- Material Sourcing and Pre-processing: Rice husk powder (RHP), a byproduct of rice milling, can be used as a low-cost support material. It is typically sieved to a uniform particle size (e.g., 300 μm) [5].

- Chemical Modification with Citric Acid (CA): To enhance the surface functionality and increase active sites for enzyme binding, RHP is modified with citric acid. The protocol involves:

- Mixing 5 g of RHP with a specific amount of citric acid (dissolved in minimal water) under continuous stirring until a homogeneous paste forms.

- The paste is dried in a petri dish at 60°C for 2 hours.

- The dried material is then incubated at 120°C for 12 hours.

- After incubation, the mixture is diluted with distilled water and vacuum-filtered to separate the modified RHP (mRHP), which is then thoroughly washed to remove unreacted citric acid [5].

- Bead Formation with Sodium Alginate (SA): The mRHP is combined with sodium alginate (SA) at various concentrations (e.g., 25%, 50%, and 100% of SA weight). This mixture is then added dropwise into a calcium chloride (CaCl₂) solution using a syringe, leading to ionotropic gelation and the formation of stable, spherical beads [5].

Enzyme Immobilization via Covalent Binding

Covalent binding is a widely used method to prevent enzyme leakage, a common drawback of simple adsorption.

- Support Activation: The SA-mRHP beads are activated using a crosslinker such as 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDAC). EDAC facilitates the formation of amide bonds between carboxylic groups on the modified support and amino groups on the enzyme surface [5].

- Immobilization Process: The purified enzyme solution is incubated with the activated beads under optimal conditions of pH and temperature for a specified period (e.g., 5 hours). The beads are then collected and thoroughly washed with buffer to remove any unbound enzyme, leaving the enzyme covalently attached to the support [5].

Characterization and Performance Evaluation

Rigorous characterization and testing are mandatory to validate the immobilization success and assess the biocatalyst's performance.

- Physical and Chemical Characterization: Techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) are used to examine the surface morphology and porosity of the support before and after immobilization. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) confirms the successful formation of covalent bonds by identifying new functional groups (e.g., amide bonds) [5].

- Activity and Kinetic Assays: Enzyme activity is determined using specific spectrophotometric assays. For chitinase, the release of p-nitrophenol is monitored at 410 nm. Kinetic parameters, such as the Michaelis constant ((Km)) and maximum reaction rate ((V{max})), are determined for both free and immobilized enzymes to evaluate changes in substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency [5].

- Stability and Reusability Tests:

- pH and Temperature Stability: The activity of free and immobilized enzymes is measured across a range of pH values and temperatures to assess stability enhancements [5].

- Storage Stability: The biocatalysts are stored under defined conditions, and their residual activity is measured over time.

- Operational Stability: The immobilized enzyme is subjected to repeated reaction cycles. After each cycle, the beads are recovered by filtration, washed, and reintroduced into a fresh reaction mixture. The retention of activity over multiple cycles (e.g., 22 cycles) is a key metric for reusability [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful enzyme immobilization research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key items and their functions.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate (SA) [5] [8] | Natural anionic polysaccharide; forms hydrogels with divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺) for entrapment or as a base for composite beads. | Formation of SA-mRHP composite beads for covalent enzyme attachment [5]. |

| Chitosan [3] [8] | Natural biopolymer derived from chitin; abundant amine groups enable direct enzyme binding or easy chemical modification. | Used as a biocompatible support for adsorption or covalent immobilization. |

| Hydroxyapatite (HAP) [6] | Green, ceramic-like support material; non-toxic, structurally stable, and can be sourced from waste. | Covalent immobilization of enzymes like transaminases and decarboxylases after derivatization [6]. |

| 1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide (EDAC) [5] | Carbodiimide crosslinker; activates carboxylic groups for formation of amide bonds with enzyme amine groups. | Covalent immobilization of chitinase onto SA-mRHP beads [5]. |

| Glutaraldehyde [3] [6] [7] | Bifunctional crosslinker; reacts with amine groups, used for activation of aminated supports or creating CLEAs. | Activation of aminated HAP support [6]; cross-linking enzyme aggregates (CLEAs) [7]. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) [6] | Silane coupling agent; introduces primary amine groups onto inorganic surfaces (e.g., HAP, silica) for further functionalization. | Surface amination of Hydroxyapatite prior to glutaraldehyde activation [6]. |

| Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [7] | A carrier-free immobilization technology; involves precipitating enzymes and cross-linking them into stable aggregates. | Creating robust, reusable biocatalysts from crude enzyme preparations [7]. |

The strategic decision to immobilize enzymes is fundamentally driven by the compelling need to enhance catalyst stability, enable reuse, and improve cost-effectiveness in industrial processes. As demonstrated by the comparative data, the performance of an immobilized enzyme is highly dependent on the synergistic combination of the support material and the immobilization technique. While traditional supports like alginate and chitosan offer cost-effective and biocompatible solutions, advanced materials like COFs and carrier-free CLEAs push the boundaries of stability and efficiency.

The choice of an optimal system is not universal; it must be tailored to the specific enzyme, process constraints, and economic considerations. Future advancements will likely involve the integration of artificial intelligence for rational design, the development of smart nanomaterials, and a stronger emphasis on green and sustainable support materials aligned with circular economy principles [7] [8]. By providing a clear framework for comparing different immobilization strategies, this guide aims to assist researchers and industry professionals in selecting and optimizing biocatalysts that unlock the full potential of enzymes for sustainable industrial applications.

Enzyme immobilization represents a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, transforming soluble biological catalysts into reusable, stable, and easily separable forms for industrial applications. The strategic confinement of enzymes to solid supports enables their continuous operation in bioreactors, simplifies downstream processing, and significantly enhances their resistance to environmental denaturation [9] [10]. As biotechnological industries increasingly prioritize sustainability and cost-effectiveness, the selection of an appropriate immobilization technique—covalent binding, adsorption, entrapment, or encapsulation—has become paramount for process optimization. Each method presents distinct advantages and limitations, influencing enzyme activity, stability, loading capacity, and operational longevity [11] [12]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these core techniques, underpinned by experimental data, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting optimal strategies for specific applications.

Core Techniques of Enzyme Immobilization

Fundamental Mechanisms and Characteristics

Enzyme immobilization techniques are broadly classified based on the nature of the interaction between the enzyme and the support matrix. The four primary methods—covalent binding, adsorption, entrapment, and encapsulation—each employ distinct mechanisms and are suitable for different operational contexts.

Covalent Binding involves the formation of stable, irreversible covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme surface (e.g., amino, carboxyl, or thiol groups) and reactive groups on the support material. This method typically utilizes activating agents such as glutaraldehyde or cyanogen bromide (CNBr) to facilitate the linkage [9] [13]. The resulting multipoint attachment confers exceptional stability, minimizing enzyme leakage even in harsh reaction media. However, the chemical modifications involved can sometimes lead to conformational changes and a potential reduction in catalytic activity due to active site obstruction or altered enzyme flexibility [12].

Adsorption relies on weak, non-covalent interactions—including hydrophobic forces, ionic bonding, and van der Waals forces—to attach enzymes to a carrier surface. Supports such as activated carbon, silica gel, octyl-agarose, or ion-exchange resins are commonly employed [9] [11]. This method is notably simple, cost-effective, and preserves high enzyme activity as it avoids harsh chemical treatments. Its principal drawback is the susceptibility to enzyme leakage (desorption) triggered by changes in pH, ionic strength, temperature, or the presence of substrates or products [12].

Entrapment physically confines enzymes within the interstitial spaces of a porous polymer network or gel, such as calcium alginate, collagen, κ-carrageenan, or polyacrylamide [9] [11]. The matrix acts as a sieve, allowing substrates and products to diffuse while retaining the larger enzyme molecules. This method effectively shields the enzyme from microbial degradation and direct exposure to unfavorable microenvironments. A significant challenge, however, is diffusional limitation, which can hinder mass transfer and reduce the apparent reaction rate, particularly with macromolecular substrates [9].

Encapsulation is a specific form of entrapment where enzymes are enclosed within semi-permeable membranes, such as in liposomes or microcapsules [9]. This creates a protective micro-environment that closely mimics cellular conditions, often leading to high activity retention. Similar to entrapment, the success of encapsulation is highly dependent on the mass transfer rates of substrates and products across the membrane barrier.

Comparative Analysis of Immobilization Techniques

The table below synthesizes the core characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of each immobilization method, providing a clear framework for initial evaluation.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Enzyme Immobilization Techniques

| Technique | Mechanism of Binding | Support Material Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Binding | Strong covalent bonds [9] | CNBr-Agarose, Glutaraldehyde-activated supports, Chitosan, Epoxy-functionalized polymers [9] | High operational stability; Minimal enzyme leakage; Excellent reusability [12] | Risk of enzyme denaturation; Complex procedure; Potential activity loss [12] |

| Adsorption | Weak physical forces (Hydrophobic, Ionic) [9] | Activated Carbon, Silica Gel, Octyl-Agarose, Polypropylene-based Accurel EP-100 [9] | Simple & inexpensive; High activity retention; Reversible [11] [12] | Enzyme leakage under shifting conditions [12] |

| Entrapment | Physical confinement in a porous network [9] | Calcium Alginate, Polyacrylamide, Gelatin, κ-Carrageenan [9] [11] | Protects from harsh environments; Broad applicability [11] | Diffusional limitations; Reduced reaction rates; Enzyme loss upon matrix rupture [12] |

| Encapsulation | Membrane enclosure [9] | Liposomes, Microcapsules [9] | Creates protective microenvironment; High activity retention | Severe diffusional limitations; Scalability challenges |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The theoretical advantages and disadvantages of each method must be validated through empirical data. The following table compiles key performance metrics from experimental studies, offering a direct comparison of efficiency and stability across different techniques and support materials.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Immobilized Enzymes

| Enzyme | Support Material | Immobilization Technique | Retained Activity (%) | Operational Stability (Half-life/Reuse Cycles) | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Candida rugosa Lipase | Poly(3-hydroxybutyrate-co-hydroxyvalerate) | Adsorption | ~94% (after 4h at 50°C) | 12 cycles | Biodegradable support with high residual activity and reusability. | [9] |

| Various Enzymes (e.g., Gs-Lys6DH, He-P5C) | Agarose vs. Methacrylate | Covalent (Epoxy/Co²⁺) | ~60-100% (Agarose); ~30-70% (Methacrylate) | Similar thermal stability on both supports | Hydrophilic agarose consistently showed ~2-fold higher recovered activity than hydrophobic methacrylate. | [14] |

| Glucose Oxidase | Silicon (with Epoxysilane) | Covalent Binding | High loading | High durability | Covalent methods on silicon provided high surface loading and durability for biosensor applications. | [13] |

| Lipase | Octyl-agarose & Octadecyl-sepabeads | Adsorption | High yield | Tenfold greater stability than free enzyme | Hydrophobicity of support enhanced affinity and stability. | [9] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) & other enzymes | Agarose vs. Methacrylate | Covalent (Glyoxyl) | Higher on Agarose | Not specified | Hydrophilic nature of agarose enhances intraparticle mass transport. | [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical "scientist's toolkit," this section outlines standard protocols for key immobilization techniques, as cited in the literature.

Covalent Binding on Epoxy-Activated Supports

This protocol is adapted from studies comparing agarose and methacrylate supports [14].

- Support Activation: The porous support (e.g., epoxy-agarose or epoxy-methacrylate) is used as provided commercially.

- Enzyme Binding: The enzyme is dissolved in a suitable buffer (e.g., 1 M potassium phosphate pH 7.0-8.5). A high ionic strength buffer is used to promote initial physical adsorption before covalent attachment.

- Incubation: The enzyme solution is mixed with the support and incubated for a prolonged period (typically 12-24 hours) at 25°C under gentle agitation to facilitate covalent coupling.

- Washing: After incubation, the immobilized enzyme is filtered and thoroughly washed with the same buffer and then with distilled water to remove any unbound enzyme.

- Blocking (Optional): Remaining epoxy groups may be deactivated by incubation with a quenching agent like 1 M glycine solution.

Adsorption on Hydrophobic Carriers

A protocol for adsorbing lipases onto hydrophobic supports is described [9].

- Support Preparation: Hydrophobic granules (e.g., octyl-agarose or polypropylene-based Accurel EP-100) are equilibrated in a low ionic strength buffer.

- Enzyme Adsorption: The enzyme solution is added to the support and incubated for a specific time (e.g., 1-2 hours) at room temperature with mild stirring. Hydrophobic interactions drive the enzyme to the support surface.

- Separation and Washing: The immobilized enzyme is separated by filtration or centrifugation and washed with buffer to remove loosely associated enzyme molecules.

Entrapment in Calcium Alginate Beads

A common entrapment method uses calcium alginate [11].

- Gel Preparation: A sodium alginate solution (2-4% w/v) is prepared in water or buffer.

- Enzyme Mixing: The enzyme is added to the sodium alginate solution and mixed thoroughly to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

- Droplet Formation: The enzyme-alginate mixture is extruded dropwise using a syringe or peristaltic pump into a cold, stirred solution of calcium chloride (50-100 mM).

- Gelation: Instantaneously, the sodium alginate droplets gel upon contact with Ca²⁺ ions, forming stable, spherical beads with the enzyme entrapped within the matrix.

- Curing and Washing: The beads are cured in the calcium chloride solution for 30 minutes to ensure complete gelation, then washed with buffer or water.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and their functions, forming a essential toolkit for conducting enzyme immobilization experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function in Immobilization | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Agarose Microbeads | Hydrophilic, porous support for covalent binding and adsorption [14] | Sepharose, Cross-linked agarose |

| Methacrylate Resins | Hydrophobic polymer support for covalent and adsorptive immobilization [14] | Relizyme, Sepabeads |

| Glutaraldehyde | Bifunctional cross-linker for covalent attachment to aminated supports [9] | 25% Aqueous solution |

| Cyanogen Bromide (CNBr) | Activating agent for hydroxylated supports (e.g., agarose, sepharose) [9] | CNBr-activated Sepharose |

| Calcium Alginate | Natural polymer for gel formation in entrapment [11] | Sodium Alginate (from seaweed) |

| Silica-Based Materials | Inorganic support with high surface area for adsorption and covalent binding [9] [12] | Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (SBA-15, MCM-41), Silica Gel |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Superparamagnetic support enabling easy catalyst recovery via magnetic separation [12] | Fe₃O₄ (Magnetite) nanoparticles |

Logical Workflow for Technique Selection

The decision-making process for selecting an optimal immobilization strategy involves evaluating the enzyme's characteristics, process requirements, and economic constraints. The following diagram maps the logical relationships between these factors and the four core techniques.

Diagram 1: Immobilization Technique Selection

The choice between covalent binding, adsorption, entrapment, and encapsulation is not a one-size-fits-all solution but a strategic decision based on a careful trade-off between stability, activity, cost, and process requirements. Covalent binding excels in applications demanding extreme operational stability and minimal enzyme leakage, such as in continuous-flow pharmaceutical synthesis [14] [12]. Adsorption offers a rapid, economical solution for single-batch reactions where mild conditions can be maintained and some enzyme loss is acceptable [9]. Entrapment and encapsulation are ideal for protecting fragile enzymes in harsh environments or when dealing with large, robust substrates, though they suffer from mass transfer constraints [9] [11].

Emerging trends point toward the rational design of hybrid and nano-supports. Nanomaterials, with their high surface area and unique properties, are pushing the boundaries of immobilization efficiency [12] [15]. Furthermore, the comparative analysis between classic materials like agarose and methacrylate provides a critical heuristic: support hydrophilicity can be a dominant factor in determining retained activity, with hydrophilic agarose often outperforming its hydrophobic counterpart [14]. For researchers in drug development and industrial biocatalysis, this guide underscores that an optimal immobilization strategy is achieved by aligning the fundamental principles of enzyme-support interactions with the specific economic and technical goals of the intended application.

The strategic selection of a support material is a critical determinant in the success of enzyme immobilization, directly influencing biocatalytic performance, operational stability, and economic viability. Immobilization addresses inherent limitations of free enzymes—such as poor stability, difficult recovery, and limited reusability—making them suitable for industrial applications in pharmaceuticals, fine chemicals, and biosensing [1] [16]. The evolution from traditional macro-supports to advanced nanomaterials represents a paradigm shift, leveraging the unique properties of nano-scale matrices to overcome the constraints of their predecessors. This guide provides a systematic comparison of enzyme immobilization supports, from classical carriers to next-generation nanomaterials, presenting objective performance data and detailed experimental methodologies to inform research and development in biocatalysis.

Classical Immobilization Supports and Techniques

Classical immobilization techniques are characterized by their well-established protocols and use of conventional, often micro- or macro-scale, support materials.

The five primary classical immobilization techniques are adsorption, covalent binding, encapsulation, entrapment, and cross-linking [16]. Each method operates on a distinct principle for enzyme fixation:

- Adsorption: Relies on weak physical forces (e.g., van der Waals, ionic, hydrophobic bonds) between the enzyme and the support surface. It is simple and cost-effective but often suffers from enzyme leakage due to weak binding [16] [1].

- Covalent Binding: Involves forming strong covalent bonds between functional groups on the enzyme (e.g., amino, carboxylic) and a chemically activated support. This method prevents enzyme leakage but risks activity loss if the reaction involves amino acids critical for catalysis [16].

- Encapsulation: Confines enzymes within a semi-permeable membrane or vesicle, allowing substrate and product diffusion while retaining the enzyme [1].

- Entrapment: Encloses enzymes within a porous polymer network or gel matrix, such as alginate or polyacrylamide, which protects the enzyme but can introduce mass transfer limitations [1] [17].

- Cross-Linking: Connects enzyme molecules to each other using bifunctional reagents (e.g., glutaraldehyde) to create carrier-free aggregates. While stable, these can suffer from reduced activity and challenges in handling [1].

Traditional Support Materials

Traditional supports are selected based on their chemical and physical properties. Table 1 summarizes common categories and examples.

Table 1: Categories of Traditional Support Materials

| Category | Examples | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Inorganic Carriers [16] | Silicas, Titania, Hydroxyapatite | High mechanical strength, thermal stability, defined porosity. |

| Natural Organic Polymers [16] | Chitin, Chitosan, Alginate, Cellulose | Biocompatible, biodegradable, often possess functional groups for modification. |

| Synthetic Polymers [17] [18] | Polyacrylamide, Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA), Poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) | Tunable properties, robustness, and controllable degradation profiles. |

The Rise of Nanomaterial Supports

Nanomaterials have emerged as superior supports due to their high surface area-to-volume ratio, which allows for greater enzyme loading, reduced mass transfer resistance, and enhanced catalytic efficiency [19] [20].

Types of Nanomaterial Supports

Table 2 compares the major classes of nanomaterials used for enzyme immobilization.

Table 2: Comparison of Nanomaterial Supports for Enzyme Immobilization

| Nanomaterial Type | Specific Examples | Advantages | Disadvantages/Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based [20] [19] | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Fullerenes | Large surface area; excellent electrical and thermal conductivity; easily functionalized. | Potential toxicity concerns; dispersion challenges in aqueous solutions. |

| Metallic & Metal Oxide [20] [19] | Gold Nanoparticles, Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄), Silver Nanoparticles | Tunable optoelectrical properties; superparamagnetism (e.g., Fe₃O₄) enables easy separation [19]. | Susceptibility to oxidation and aggregation without proper coating. |

| Polymeric [20] [17] | PLGA-PEG, Chitosan NPs, Polymeric Nanogels (e.g., Zwitterionic) | High biocompatibility and biodegradability; ability to encapsulate and protect enzymes [17] [21]. | Can be costly; may contain solvent residues from synthesis [20]. |

| Organic-Inorganic Hybrids [20] | Hybrid Nanoflowers (e.g., enzyme-Cu₃(PO₄)₂) | Unique flower-like structure offers immense surface area; synergistic stabilization of enzymes. | Synthesis mechanism and long-term stability can require further investigation. |

Comparative Performance Analysis

The transition to nanomaterials is driven by measurable improvements in key performance metrics compared to traditional supports.

Quantitative Comparison of Key Metrics

Table 3 summarizes experimental data highlighting the performance differences between traditional and nanomaterial supports.

Table 3: Experimental Performance Data of Different Support Types

| Support Material & Technique | Enzyme | Key Performance Findings | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Epoxy Methyl Acrylate (Traditional) [22] | Not Specified | TD-NMR quantified enzyme loading within pores; adsorption curves aligned with photometric data. | Validation of a novel quantification method (TD-NMR relaxometry). |

| PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles (Nano) [17] [18] | Catalase | 30s sonication DE nanoparticles provided the greatest enzymatic activity protection in degradative conditions. | Comparison of double emulsion (DE) and nanoprecipitation (NPPT) formulation methods. |

| Zwitterionic Nanogel (Nano) [21] | β-Galactosidase (β-gal) | Covalent immobilization with a spacer arm dramatically increased retained enzyme activity versus direct immobilization. Hybrid nanogel-enzymes showed superior stability against heat, organic solvents, and proteolysis. | Evaluation of spacer (BDDE) impact on activity and stability. |

| Covalent Binding on Functionalized CNTs (Nano) [19] | Nitrilase (3wuy) | Computational studies showed optimal substrate positioning in the active site; multiple noncovalent interactions (e.g., pi-pi) facilitated efficient catalytic conversion. | In silico analysis of enzyme-substrate interactions post-immobilization. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical toolkit, this section outlines key experimental protocols cited in the comparison tables.

Protocol 1: Formulating Enzyme-Loaded PLGA-PEG Nanoparticles via Double Emulsion

This protocol is adapted from studies optimizing the encapsulation of catalase in PLGA-PEG nanoparticles for neurotherapeutic applications [17] [18].

- Objective: To formulate enzyme-loaded polymeric nanoparticles that maximize enzymatic activity loading and protection.

- Materials:

- Polymer: PLGA (45k, LA:GA 50:50) copolymerized with PEG (5k).

- Enzyme: Catalase from bovine liver.

- Solvents: Dichloromethane (DCM) or Trichloromethane (TCM/Chloroform).

- Surfactants: Cholic/deoxycholic acid (CHA) sodium salt or Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA).

- Aqueous Buffer: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Equipment: Sonic Dismembrator Ultrasonic Processor, centrifuge.

- Methodology:

- Primary Emulsion (w1/o): Dissolve 1 mg of catalase in 100 μL PBS. Combine with 100 μL of 1 wt% surfactant (CHA or PVA). Add this aqueous phase to 25 mg of PLGA-PEG polymer dissolved in 1 mL of organic solvent (DCM or TCM). Emulsify using a probe sonicator at 30% amplitude with 1s on:1s off pulses for 30 seconds.

- Secondary Emulsion (w1/o/w2): Add the primary emulsion to 4 mL of a 3% CHA or 5% PVA solution in deionized water. Perform a second sonication at 20% amplitude with 1s on:1s off pulses for 30 seconds.

- Solvent Evaporation & Collection: Pour the final emulsion into a beaker containing 25 mL of PBS stirred at 500 rpm for 3 hours to allow the organic solvent to evaporate. Collect the nanoparticles via centrifugation (100,000 RCF for 1 hour). Wash the pellet with PBS and resuspend in 1 mL of PBS for storage at 4°C.

- Critical Notes: Sonication time is a critical parameter; 30s was identified as optimal for balancing enzyme activity and nanoparticle size. Replacing DCM with TCM can mitigate toxicity in sensitive biological environments [17] [18].

Protocol 2: Covalent Immobilization with a Spacer Arm on Zwitterionic Nanogels

This protocol details the method for enhancing enzyme activity and stability using spacers, as demonstrated with β-galactosidase [21].

- Objective: To covalently immobilize an enzyme onto a zwitterionic polymer nanogel while minimizing activity loss via a spacer arm.

- Materials:

- Nanogel: Poly(MPC-co-MNHS) (PMS) synthesized via RAFT polymerization.

- Enzyme: β-Galactosidase.

- Spacer: 1,4-Butanediol diglycidyl ether (BDDE).

- Coupling Agent: Ethylenediamine (EDA).

- Buffers: Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4) and Borate Buffer (pH 8.5).

- Equipment: Centrifuge, dialysis membrane (MWCO 14 kDa).

- Methodology:

- Support Activation: React 100 mg of PMS copolymer with 10 μL of ethylenediamine (EDA) in 10 mL PBS to create amine-functionalized nanogels (PMS-NH₂). Purify via dialysis and freeze-dry.

- Enzyme Modification: Interact 10 mg/mL of β-gal with 5% (v/v) BDDE in PBS buffer for 4 hours to introduce epoxy groups onto the enzyme (β-gal-BDDE). Purify by dialysis and freeze-dry.

- Conjugation: Dissolve PMS-NH₂ (10 mg/mL) and β-gal-BDDE (1 mg/mL) in PBS buffer and react at room temperature overnight.

- Collection: Separate the hybrid nanogel-enzymes (BNG) from unbound enzyme by centrifugation (14,000 rpm for 15 minutes).

- Critical Notes: Immobilization with the spacer (BDDE) was shown to reduce structural changes in β-gal and dramatically increase retained activity compared to direct immobilization, though with a slight trade-off in stability [21].

Logical Workflow and Material Toolkit

Experimental Selection Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting an appropriate immobilization strategy based on application requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4 lists key reagents and their functions for immobilization experiments, as derived from the cited protocols.

Table 4: Essential Reagent Toolkit for Enzyme Immobilization Research

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| PLGA-PEG Copolymer [17] [18] | Biodegradable polymer matrix for encapsulation; PEG provides "stealth" properties and biocompatibility. | Forming the core-shell structure of nanoparticles for enzyme delivery. |

| Zwitterionic Polymer (e.g., PMS) [21] | Hydrogel nanogel carrier; phosphorylcholine groups provide high biocompatibility and anti-biofouling properties. | Creating a hydrated, stable microenvironment for enzymes to enhance stability. |

| Glutaraldehyde [16] [19] | Bifunctional crosslinker for covalent immobilization; reacts with amine groups on enzymes and supports. | Activating aminated supports or creating cross-linked enzyme aggregates (CLEAs). |

| Cholic Acid / PVA [17] [18] | Surfactants used in emulsion formulations to stabilize the interface between aqueous and organic phases. | Stabilizing w/o and w/o/w emulsions during double emulsion nanoparticle synthesis. |

| Spacer Arms (e.g., BDDE, EDA) [21] | Molecular linkers placed between the support and enzyme to reduce steric hindrance. | Improving retained enzyme activity in covalent immobilization on nanogels. |

The landscape of enzyme immobilization supports is diverse, spanning from well-characterized traditional materials to sophisticated nanomaterials. Traditional carriers like porous polymers and inorganic oxides offer cost-effectiveness and operational simplicity, making them suitable for many large-scale industrial processes. However, the data demonstrates that nanomaterial supports—including polymeric nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and hybrid nanoflowers—consistently provide superior performance in terms of enzyme loading, catalytic efficiency, stability under harsh conditions, and reusability. The choice of an optimal support is highly application-dependent. Researchers must balance factors such as the required catalytic lifetime, process cost, enzyme characteristics, and the need for easy separation. The ongoing integration of material science with biotechnology, exemplified by the design of smart carriers like zwitterionic nanogels, continues to push the boundaries of what is possible with immobilized enzymes, paving the way for more efficient and sustainable biocatalytic processes.

The selection of an appropriate support matrix is a critical determinant in the success of enzyme immobilization, directly influencing catalytic efficiency, operational stability, and economic viability. This process, which confines enzymes to a distinct phase from substrates and products, enhances enzyme stability, facilitates recovery and reuse, and improves performance under industrial conditions [9]. The fundamental division in support materials lies between inorganic supports, such as ceramics, silica, and metal oxides, and organic supports, including natural and synthetic polymers [3].

The choice between these material classes involves navigating a complex trade-off between their inherent physicochemical properties. Inorganic supports typically offer superior mechanical robustness and thermal stability, whereas organic supports often excel in biocompatibility and ease of functionalization [23] [24]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these material families, focusing on the key performance metrics of porosity, biocompatibility, and mechanical stability, framed within the broader thesis of optimizing enzyme immobilization efficiency for industrial and biomedical applications.

Comparative Analysis of Fundamental Properties

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of inorganic and organic supports, providing a high-level overview for researchers.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Inorganic and Organic Supports for Enzyme Immobilization

| Property | Inorganic Supports | Organic Supports |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Materials | Mesoporous silica, porous glass, hydroxyapatite (HaP), metal oxides (e.g., TiO₂), magnetic nanoparticles [23] [24] | Natural polymers (chitosan, alginate, collagen), synthetic polymers (epoxy resins, polyacrylates), hydrogels [23] [3] |

| Primary Immobilization Interactions | Adsorption via hydrogen bonding, ionic interaction, hydrophobic forces [3] | Covalent binding, affinity interactions, physical entrapment [9] [25] |

| Typical Porosity | Well-defined pore structures (micro- and mesoporous); tunable pore sizes [25] [24] | Variable porosity; often less ordered; can form highly hydrated gel networks [9] [25] |

| Mechanical Stability | High compressive strength, rigid, and durable [23] | Softer, more flexible; mechanical properties can be tunable [23] |

| Thermal & pH Stability | Generally high stability across a broad range of temperatures and pH [24] | May be susceptible to degradation under extreme pH or temperature [3] |

| Biocompatibility | Generally good; materials like HaP are highly bioactive [26] | Typically excellent; natural polymers are often inherently biocompatible [23] |

| Cost & Scalability | Cost of synthesis for advanced materials (e.g., MOFs) can be high [3] | Natural polymers are often cost-effective and renewable [3] |

Deep Dive into Performance Metrics

Porosity and Surface Area

Porosity is paramount as it dictates the enzyme loading capacity and influences mass transfer efficiency of substrates and products.

Inorganic Supports: This class is renowned for its highly structured and tunable porosity. Materials like Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) and Crystalline Porous Organic Frameworks (CPOFs), including Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs), offer exceptionally high surface areas and uniform pore size distributions [25] [24]. This allows for precise size-selective immobilization and high enzyme loading. The rigid pore structure prevents leaching and can protect enzymes from denaturation [25].

Organic Supports: Porosity in organic matrices is often more variable. Hydrogels possess a highly porous, hydrated structure that can reduce diffusion limitations for substrates [25]. However, these pores may be less defined and more susceptible to swelling or collapse under changing conditions. Polymer networks and electrospun nanofibers provide high surface area-to-volume ratios, but the porosity is generally less ordered than in their inorganic counterparts [9] [23].

Table 2: Experimental Data on Porosity and Performance

| Support Material | Specific Surface Area (m²/g) | Pore Size (nm) | Reported Enzyme Loading | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent Organic Framework (COF) [25] | High (exact value not specified) | Mesoporous | High trypsin immobilization | The hollow spherical, mesoporous structure enabled high loading and stability. |

| Mesoporous Silica (MCM-41) [25] | High | Mesoporous | Not Specified | Encapsulated enzymes showed excellent catalytic stability and no activity loss after three uses. |

| Hydrogel (Alginate-Gelatin) [9] | N/A (Macroporous gel) | N/A | Prevented enzyme leakage | The highly porous, macroporous structure reduced substrate transfer limitations. |

Biocompatibility

Biocompatibility is critical for biomedical applications such as drug delivery, biosensing, and implantable devices.

Inorganic Supports: Many inorganic materials demonstrate excellent biocompatibility. Hydroxyapatite (HaP) is a prime example, being a natural component of bone. Composite scaffolds based on HaP show enhanced bioactivity, forming a robust HaP layer in simulated body fluid and supporting high viability of human fibroblast cells [26]. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and related materials like Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs) are also noted for good biocompatibility, though concerns regarding long-term metal ion toxicity and metabolism require careful consideration [25].

Organic Supports: This class generally holds an advantage in biocompatibility, particularly for natural polymers. Chitosan, collagen, and alginate are biologically derived, biodegradable, and present low immunogenicity, making them ideal for therapeutic applications [23] [3]. Their hydrophilic and hydrated nature mimics the native cellular environment, minimizing adverse immune responses. Synthetic polymers can be engineered for biocompatibility, though their degradation by-products must be evaluated [23].

Mechanical and Chemical Stability

Operational longevity under industrial conditions (e.g., shear forces, solvents, temperature) is a key advantage of immobilization.

Inorganic Supports: They are the clear leaders in mechanical robustness. Materials like silica, hydroxyapatite, and ceramics offer high compressive strength, rigidity, and resistance to organic solvents [23] [24]. This makes them suitable for continuous flow reactors and applications involving significant physical stress. They also exhibit outstanding thermal stability, maintaining structural integrity at high temperatures where many organic polymers would degrade [24].

Organic Supports: While generally less rigid, their mechanical properties are highly tunable. By cross-linking or forming composites, their strength and elasticity can be enhanced. For instance, incorporating graphene into poly-ε-caprolactone (PCL) nanofibers significantly increased the elastic modulus of the scaffold [23]. However, they may be more susceptible to chemical degradation, such as the hydrolysis of ester bonds in some polyesters or swelling in specific solvents, which can compromise long-term stability [23].

Table 3: Experimental Data on Mechanical and Chemical Stability

| Support Material | Experimental Test | Key Result on Stability |

|---|---|---|

| MgTiO3-HaP Composite Scaffold [26] | Heat treatment at 1200°C | Formation of the MgTiO3 phase crucial for improved mechanical properties. |

| Polypropylene-based Granules (Accurel EP-100) [9] | Biocatalysis in organic solvent | Adsorbed lipase showed high stability and enantiomeric ratios; smaller particle sizes increased reaction rates. |

| Inorganic-Organic Hybrid Metamaterial (CIOHM) [27] | Uniaxial compression testing | Exhibited switchable stiffness and elasticity, with toughness an order of magnitude higher than traditional calcium phosphate cement. |

| Candida rugosa lipase on biodegradable polymer [9] | Operational reusability | Retained 94% residual activity at 50°C after 4 hours and could be reused for 12 cycles. |

Experimental Protocols for Immobilization and Analysis

To ensure reproducibility in comparative studies, standardized protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for common immobilization techniques and subsequent analysis.

Principle: The enzyme is physically adsorbed onto the support surface via weak forces (hydrophobic, ionic, van der Waals).

- Support Preparation: Activate 1.0 g of mesoporous silica (e.g., MCM-41) by drying in an oven at 105°C for 2 hours to remove moisture.

- Enzyme Solution Preparation: Dissolve the target enzyme (e.g., 50 mg of trypsin) in a suitable buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0).

- Immobilization: Add the activated silica to the enzyme solution. Incubate the mixture with gentle shaking (e.g., 150 rpm) at 4°C for 4-6 hours to allow for adsorption.

- Washing and Recovery: Separate the solid support by centrifugation (e.g., 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes). Wash the pellet multiple times with the same buffer to remove any unbound enzyme.

- Storage: The immobilized enzyme can be stored wet at 4°C or lyophilized for long-term storage.

Principle: The enzyme is irreversibly bound to the support via strong covalent bonds, often using a cross-linker.

- Support Activation: Suspend 1.0 g of chitosan beads in a 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde solution in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Stir for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Washing: Thoroughly wash the activated beads with the same buffer to remove excess glutaraldehyde.

- Enzyme Binding: Add the activated beads to the enzyme solution (e.g., 50 mg of enzyme in 50 mL of phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). Incubate with gentle agitation for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Quenching and Final Wash: To block any remaining active groups, add a quenching agent (e.g., 1 M glycine) and incubate for 1 more hour. Wash the final immobilized enzyme preparation extensively with buffer to remove any loosely bound material.

- Activity Assay: Compare the enzymatic activity of the initial free enzyme solution, the washings, and the final immobilized preparation using a standard assay (e.g., MTT assay for cell viability or a specific substrate conversion assay). Calculate immobilization yield and efficiency.

- Thermal Stability: Incubate both free and immobilized enzymes at elevated temperatures (e.g., 50-70°C) for set time intervals. Measure residual activity to determine half-life and deactivation constants.

- Reusability: Use the immobilized enzyme in consecutive batch reactions. After each cycle, recover the catalyst by filtration/centrifugation, wash, and reassay. Track the loss of activity over multiple cycles (e.g., 10 cycles).

- Biocompatibility (for biomedical applications): Perform in vitro cell viability assays, such as the MTT assay with human fibroblast cells, as described for HaP-based scaffolds [26].

Visualization of Support-Enzyme Interactions and Properties

The following diagrams illustrate the structural relationships and property trade-offs between inorganic and organic supports.

Diagram 1: Structural comparison of inorganic and organic supports, highlighting their distinct immobilization mechanisms and characteristic advantages (blue) versus limitations (red).

Diagram 2: A decision pathway for selecting between inorganic and organic supports based on application priorities.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Reagents for Enzyme Immobilization Research

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Glutaraldehyde [3] | Bifunctional crosslinker for covalent immobilization on amine-containing supports. | Activating chitosan, sepharose, or other polymers for stable enzyme attachment. |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) [9] [24] | High-surface-area inorganic support for adsorption-based immobilization. | Studying enzyme loading capacity, stability in organic solvents, and reusability. |

| Chitosan [3] | A natural, biocompatible, and biodegradable polymer support. | Developing immobilized enzymes for biomedical or food-grade applications. |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) [25] | Crystalline porous organic supports with tunable pore chemistry. | Investigating high-loading, stable immobilization with minimal enzyme leaching. |

| Simulated Body Fluid (SBF) [26] | Buffer solution mimicking blood plasma ion concentration. | Evaluating bioactivity and biodegradability of supports for implantable devices. |

| Epoxy-Activated Supports [24] | Supports for covalent immobilization without a pre-activation step. | One-step, stable enzyme binding under mild conditions. |

The dichotomy between inorganic and organic supports is not a matter of superiority, but of application-specific suitability. Inorganic supports excel in environments demanding robust mechanical strength, high thermal stability, and well-defined nanoscale porosity. Their rigid structures are ideal for continuous industrial bioprocesses and harsh reaction conditions. Conversely, organic supports offer unparalleled biocompatibility, tunable mechanical properties, and a hydrated microenvironment that often better preserves native enzyme conformation, making them the preferred choice for biomedical, diagnostic, and food-grade applications.

The future of enzyme immobilization lies in hybrid and advanced composite materials that transcend this traditional binary. Emerging materials like inorganic-organic hybrid metamaterials demonstrate switchable stiffness and elasticity, offering the best of both worlds [27]. Similarly, the integration of crystalline porous organic frameworks (CPOFs) provides a metal-free, highly tunable platform with exceptional potential for biomedical applications [25]. The ongoing research focus should be on the rational design of these next-generation supports, leveraging the distinct advantages of both inorganic and organic components to create tailored solutions for the evolving demands of biocatalysis.

In the pursuit of sustainable biocatalytic processes for pharmaceutical and industrial applications, enzyme immobilization has emerged as a critical technology. It enhances enzyme stability, facilitates reuse, and reduces operational costs. Among the various supporting matrices, natural polymers—chitosan, alginate, and cellulose—have garnered significant attention from researchers and drug development professionals. These biopolymers are sourced from renewable resources, are inherently biodegradable and biocompatible, and possess functional groups that enable gentle yet effective enzyme attachment. Their versatility allows them to be fabricated into diverse forms such as beads, membranes, fibers, and hydrogels, catering to specific biocatalytic requirements.

The selection of an appropriate immobilization support is paramount, as it directly influences the catalytic efficiency, operational stability, and overall economics of the process. This guide provides a comparative analysis of chitosan, alginate, and cellulose, drawing on recent experimental data to objectively evaluate their performance as enzyme immobilization matrices. By synthesizing key findings on immobilization efficiency, stability under operational conditions, and reusability, this article aims to inform the rational design of more efficient and sustainable biocatalytic systems for advanced research and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Biopolymer Properties and Performance

The efficacy of a biopolymer as an immobilization support is determined by a combination of its intrinsic structural properties and the resulting performance in biocatalytic applications. The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics of chitosan, alginate, and cellulose that are most relevant to their use in enzyme immobilization.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Selected Biopolymers for Enzyme Immobilization

| Biopolymer | Source | Chemical Structure Features | Key Functional Groups | Primary Immobilization Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Crustacean shells, fungi | Linear copolymer of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine [28] | Primary amine (-NH₂), hydroxyl (-OH) [8] | Covalent binding, adsorption, affinity bonding |

| Alginate | Brown algae | Linear copolymer of β-D-mannuronate and α-L-guluronate [29] [28] | Carboxylate (-COO⁻), hydroxyl (-OH) [8] | Entrapment, ionic cross-linking (e.g., with Ca²⁺) |

| Cellulose | Plants, bacteria, algae | Linear chain of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units [30] | Hydroxyl (-OH) [8] | Adsorption, covalent binding (after activation) |

Beyond their basic chemistry, the practical performance of these biopolymers in immobilizing enzymes has been extensively tested. The following table consolidates quantitative experimental data from recent studies, providing a direct comparison of their effectiveness.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison for Enzyme Immobilization

| Biopolymer & Form | Enzyme Immobilized | Immobilization Efficiency/ Yield | Operational Stability (Retained Activity) | Reusability (Cycles) | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chitosan-Cellulase Nanohybrid on Alginate Beads | Cellulase | Not Specified | Enhanced pH & thermal stability | Effective recycling demonstrated | Novel nanohybrid synthesis minimized enzyme leaching. | [31] |

| Calcium Alginate Beads | Cellulase | 92.11% | Optimal activity at pH 8 & 50°C | 5 | High immobilization efficiency, but Km increased to 72.28 mg/mL. | [32] |

| Agar (Cellulose Derivative) Cubes | Cellulase | 97.63% | Optimal activity at pH 4 & 60°C | 5 | Highest efficiency, lowest Km (13.08 mg/mL) among methods. | [32] |

| Chitosan-Bacterial Cellulose (CS-BC) Scaffold | (Scaffold for cell culture) | (Not applicable) | Excellent cell attachment & metabolic activity | (Not applicable) | Composite showed enhanced mechanical strength and biocompatibility. | [30] |

Interpretation of Comparative Data

The data reveals a clear trade-off between immobilization efficiency and the potential impact on enzyme kinetics. Agar, a derivative of cellulose, demonstrated the highest immobilization efficiency (97.63%) and the most favorable substrate affinity (lowest Km), suggesting minimal obstruction of the enzyme's active site [32]. This makes cellulose-based matrices particularly attractive for applications where catalytic efficiency is critical.

Conversely, while calcium alginate beads achieved high immobilization efficiency (92.11%), they resulted in a significantly higher Km value, indicating a reduced affinity for the substrate, potentially due to diffusional limitations within the gel matrix [32]. The chitosan-cellulase nanohybrid approach highlights an innovative strategy to combat enzyme leaching, a common drawback of entrapment methods, by pre-forming a stable complex before immobilization on alginate beads [31].

Furthermore, the synergy between biopolymers is a powerful tool for material design. The chitosan-bacterial cellulose (CS-BC) composite scaffold exemplifies this, combining the mechanical robustness of bacterial cellulose with the beneficial biological properties of chitosan to create a superior support structure [30]. This principle can be effectively translated from tissue engineering to the design of robust biocatalysts.

Experimental Protocols for Enzyme Immobilization

To ensure reproducibility and provide a practical guide for researchers, detailed methodologies for immobilizing enzymes on these biopolymers are outlined below. These protocols are adapted from recent studies and can be modified based on specific enzyme and application requirements.

Protocol 1: Cellulase Immobilization via Alginate Entrapment

This protocol describes the entrapment of cellulase within calcium alginate beads, a widely used method due to its simplicity and mild conditions [32].

- Materials: Sodium alginate powder, cellulase enzyme (e.g., from Aspergillus sp.), calcium chloride (CaCl₂), distilled water, sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.8).

- Methodology:

- Dissolve sodium alginate in distilled water at concentrations of 1-3% (w/v) with continuous stirring and heating to 75°C to form a homogeneous solution [29].

- Cool the alginate solution to room temperature. Gently mix the cellulase enzyme solution (diluted 1:5 with distilled water) into the alginate solution at a 1:5 (v/v) ratio.

- Allow the alginate-enzyme mixture to rest for 30 minutes to remove air bubbles.

- Using a syringe or pipette, slowly drip the mixture into a chilled 0.2 M CaCl₂ solution. The droplets will instantaneously form gel beads upon contact.

- Allow the beads to cure in the CaCl₂ solution at 4°C for 1-2 hours to enhance mechanical strength.

- Collect the beads by filtration and wash them twice with 50 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 4.8) to remove any surface-adsorbed enzyme.

- The immobilized beads can be stored in buffer at 4°C until use [32].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of a Chitosan-Cellulase Nanohybrid

This advanced protocol involves the synthesis of a chitosan-enzyme nanohybrid prior to immobilization, which significantly reduces enzyme leakage [31].

- Materials: Chitosan powder (degree of deacetylation >85%), cellulase enzyme, acetic acid, sodium alginate, calcium chloride (CaCl₂).

- Methodology:

- Prepare a chitosan solution by dissolving chitosan powder in a 1% (v/v) acetic acid solution.

- Synthesize the chitosan-cellulase (Ch-Ce) nanohybrid by adding the cellulase solution to the chitosan solution under conditions that promote self-assembly and encapsulation of the enzyme by chitosan polymers. The specific parameters (pH, concentration, mixing ratio) are optimized for the target enzyme.

- Characterize the resulting nanohybrid using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and particle size analysis, which typically show spherical nanoparticles with sizes ranging from 26-51 nm and average particle sizes of 164–342 nm [31].

- Immobilize the synthesized nanohybrid by mixing it with a sodium alginate solution.

- Drip the alginate-nanohybrid mixture into a CaCl₂ solution to form composite beads, following steps similar to Protocol 1.

- The resulting beads exhibit enhanced stability against pH and temperature changes due to the stable nanohybrid structure [31].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key steps and decision points in these immobilization protocols.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation in enzyme immobilization requires a specific set of reagents and materials. The table below lists key items and their functions to aid in laboratory preparation.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Biopolymer-Based Enzyme Immobilization

| Reagent/Material | Function and Application Note |

|---|---|

| Sodium Alginate | The sodium salt of alginic acid; used as the precursor for forming gel beads via ionic cross-linking with divalent cations like Ca²⁺ [32]. |

| Chitosan | A cationic polysaccharide; used for covalent enzyme binding, adsorption, or synthesis of nanohybrids. Its amine groups are key functional sites [31] [8]. |

| Cellulase Enzyme | A model hydrolytic enzyme complex used in many immobilization studies; its activity is easily measured using standard assays with substrates like carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) [32]. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) | A cross-linking agent; its Ca²⁺ ions ionically bridge guluronate blocks in alginate, leading to the formation of a stable "egg-box" gel structure [32]. |

| Acetic Acid | Solvent for dissolving chitosan. Typically used as a 1-2% (v/v) aqueous solution to protonate amine groups and render chitosan soluble [29] [31]. |

| Sodium Citrate Buffer | Used for washing and storing immobilized beads. Citrate ions can chelate Ca²⁺, so its concentration and pH must be carefully controlled to avoid bead dissolution [32]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A common homobifunctional cross-linker; used to covalently stabilize enzymes on supports like chitosan by reacting with amine groups [31] [8]. |

| Carboxymethyl Cellulose (CMC) | A soluble cellulose derivative; serves as a substrate for measuring cellulase activity in standard assays (e.g., DNS method) [32]. |

Chitosan, alginate, and cellulose each offer a unique profile of advantages and limitations as enzyme immobilization supports. Alginate excels in simplicity and efficiency for entrapment, chitosan provides versatile chemistry for covalent attachment and advanced nanohybrid formation, and cellulose (and its derivatives) offers robust, efficient matrices with high substrate affinity. The choice among them is not a matter of identifying a single superior option, but rather of matching the polymer's properties to the specific requirements of the enzymatic reaction, including the need for stability, reusability, and minimal activity loss.

The future of biocatalysis lies in the intelligent design of hybrid and composite materials that leverage the strengths of individual biopolymers while mitigating their weaknesses. The experimental data and protocols provided herein offer a foundation for researchers and drug development professionals to make informed decisions and advance the development of efficient, sustainable, and economically viable immobilized enzyme systems.

Enzyme immobilization represents a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, transforming soluble biological catalysts into reusable, robust systems suitable for industrial applications. The drive to compare the efficiency of various immobilization supports necessitates a deep understanding of four critical performance metrics: activity retention, stability, reusability, and loading capacity. These parameters collectively determine the economic viability and practical feasibility of an immobilized enzyme system, guiding researchers in selecting optimal supports for specific applications from drug synthesis to environmental bioremediation [3] [2].

Activity retention measures the catalytic power preserved after immobilization, while stability quantifies the enzyme's resistance to operational stresses like temperature and pH fluctuations. Reusability reflects the number of catalytic cycles a preparation can endure, directly impacting long-term costs, and loading capacity defines the amount of enzyme a support can effectively bind. Together, these metrics form a multidimensional efficiency profile, enabling objective comparison between diverse support materials ranging from traditional polymers to cutting-edge nanomaterials [12] [8]. This guide systematically compares these metrics across support types, providing standardized experimental frameworks for their determination to empower data-driven decisions in immobilization strategy selection.

Core Efficiency Metrics and Their Significance

Quantitative Comparison of Support Performance

The following table synthesizes experimental data for key support categories, highlighting their characteristic performance across the four critical efficiency metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Efficiency Metrics of Common Immobilization Supports

| Support Material | Typical Activity Retention (%) | Stability Enhancement (Half-life Increase) | Reusability (Cycles with >80% Activity) | Loading Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | 70 - 90% [12] | Significant (2-3 fold) [12] | >10 cycles [12] | High (large surface area) [12] |

| Alginate-Based Beads | Varies with method [5] | Improved vs. free enzyme [5] | ~22 cycles demonstrated [5] | Good; enhanced with modifiers (e.g., RHP) [5] |

| Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | High due to tuned microenvironments [7] | High under harsh conditions [7] | High, due to strong covalent binding [7] | Very High (high surface area) [7] |

| Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) | Can be high, but depends on cross-linker [7] | Highly stable to pH, temperature, solvents [7] | Excellent (e.g., ~60% after 7 cycles [7]) | Highest (carrier-free) [7] |

| Agarose Beads | Can be tailored (e.g., 3x higher activity possible) [33] | Varies with loading and conditions (e.g., Ca²⁺ stabilizes) [33] | Good, but depends on binding strength | High, but overloaded beads less stable [33] |

Detailed Metric Definitions and Experimental Protocols

Activity Retention quantifies the percentage of initial catalytic activity preserved after the immobilization process. It is a direct indicator of the immobilization method's gentleness and its success in maintaining the enzyme's native conformation. Low activity retention can result from enzyme denaturation, diffusion limitations, or obstruction of the active site.

- Experimental Protocol for Measurement:

- Assay Free Enzyme Activity: Under standardized conditions (e.g., specific pH, temperature, substrate concentration), measure the initial reaction rate (Vfree) of the free enzyme. This typically involves monitoring product formation per unit time.

- Assay Immobilized Enzyme Activity: Using the exact same reaction conditions and the same total amount of enzyme, measure the initial reaction rate (Vimmob) of the immobilized preparation.

- Calculate Percentage: Activity Retention (%) = (Vimmob / Vfree) × 100% [33].

Stability encompasses an immobilized enzyme's resilience to environmental stressors, including thermal, pH, and operational denaturation. Enhanced stability is a primary benefit of immobilization, often achieved through multi-point attachment that restricts denaturing unfolding.

- Experimental Protocol for Measurement (Thermal Stability):

- Incubate Samples: Expose both free and immobilized enzyme preparations to an elevated temperature (e.g., 50°C or 60°C) for a set period.

- Sample Periodically: At predetermined time intervals, withdraw aliquots and immediately cool them on ice.

- Measure Residual Activity: Assay the remaining activity of each sample under standard conditions.

- Determine Half-life: Plot residual activity (%) versus incubation time. The time at which 50% of the initial activity is lost is the half-life (t₁/₂). The fold-increase in t₁/₂ for the immobilized enzyme versus the free enzyme quantifies stability enhancement [34].

Reusability is a critical economic metric, defining an immobilized enzyme's ability to be recovered and reused in multiple reaction cycles without significant activity loss. It is primarily limited by enzyme leaching, inactivation, or physical loss of the support during recovery.

- Experimental Protocol for Measurement:

- Perform a Batch Reaction: Conduct a standard catalytic reaction with the immobilized enzyme.

- Recover the Biocatalyst: After the reaction, separate the immobilized enzyme from the products and reaction mixture (e.g., by filtration, centrifugation, or magnetic separation for MNPs).

- Wash and Reuse: Wash the recovered biocatalyst and introduce it into a fresh reaction mixture.

- Monitor Activity Decay: Repeat steps 1-3, measuring the activity in each cycle. Reusability is reported as the number of cycles completed before activity falls below a set threshold (e.g., 50% or 80% of its initial value) [12] [5].

Loading Capacity defines the maximum amount of enzyme that can be effectively bound per unit mass (or volume) of the support material. A high loading capacity is desirable to create highly active biocatalysts with a small support footprint.

- Experimental Protocol for Measurement:

- Immobilization in Controlled Conditions: Incubate a known mass of support with a known concentration and volume of enzyme solution.

- Quantify Unbound Enzyme: After immobilization, separate the support and measure the protein concentration remaining in the supernatant (e.g., using the Bradford or Lowry assay).

- Calculate Bound Protein: Loading Capacity (mg enzyme / g support) = (Total protein added - Protein in supernatant) / Mass of support used [12].

Figure 1: Experimental Workflow for Evaluating Immobilization Supports. This diagram outlines the logical sequence for systematically comparing the efficiency of different enzyme immobilization supports, from defining objectives to the final selection based on quantified metrics.

Case Studies and Experimental Data

Case Study 1: Covalent Immobilization of Chitinase on Alginate Beads

A 2025 study immobilized recombinant chitinase A (SmChiA) onto sodium alginate beads modified with rice husk powder (mRHP) via carbodiimide-mediated covalent binding [5].

Performance Metrics:

- Reusability: The immobilized SmChiA demonstrated exceptional operational stability, maintaining full activity for 22 reuse cycles, a key advantage for continuous industrial processing.

- Stability: The immobilized enzyme showed significantly improved pH and temperature stability compared to its free counterpart.

- Loading & Activity: Optimization achieved a 1.75 U/mL enzyme solution loading on beads with 50% mRHP, resulting in a biocatalyst with high decolorization efficiency for synthetic dyes [5].

Protocol Highlights:

- Support Preparation: RHP was modified with citric acid to increase carboxylic groups. mRHP was mixed with sodium alginate and cross-linked with CaCl₂ to form beads.

- Activation & Immobilization: Bead carboxylic groups were activated with EDAC (1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide), facilitating amide bond formation with enzyme amine groups.

- Activity Assay: Enzyme activity was determined spectrophotometrically by monitoring the release of p-nitrophenol from a substrate [5].

Case Study 2: Site-Specific Immobilization of β-Agarase on Magnetic Nanoparticles

This study compared immobilizing β-agarase via different functional groups (amino vs. carboxyl) onto streptavidin-coated magnetic nanoparticles (SA@MNPs) using the high-affinity biotin-streptavidin (BT/SA) system [34].

Performance Metrics:

- Activity Retention: Both methods achieved high activity retention, but the amino-activated immobilization showed better catalytic efficiency.

- Stability: The amino-activated immobilized enzyme (β-agarase-NH-BT-SA@MNPs) exhibited superior thermal stability, with a half-life at 50°C that was 2.33 times longer than the carboxyl-activated version.

- Reusability: The oriented immobilization afforded by this method likely contributes to excellent reusability, though a specific cycle count was not provided in the excerpt [34].

Protocol Highlights:

- Enzyme Activation: Amino groups were biotinylated using N-Succinimidyl 6-Biotinamidohexanoate (NSBH). Carboxyl groups were activated with EDC/NHS to react with biotin-C5-amine.

- Immobilization: The biotinylated enzymes were bound to SA@MNPs via the strong BT/SA interaction.

- Oriented Immobilization: This method provides a controlled, site-specific attachment, minimizing active site obstruction and conformational distortion [34].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Immobilization Protocols

| Reagent / Material | Function in Immobilization Protocol | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Carbodiimides (e.g., EDAC) | Activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation with amine groups. | Covalent immobilization on alginate beads [5]. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A bifunctional cross-linker that reacts with amine groups. | Forming Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates (CLEAs) [7]. |

| Biotin/Streptavidin System | Provides a very high-affinity, oriented binding pair for immobilization. | Site-specific attachment of β-agarase to MNPs [34]. |

| Sodium Alginate | A natural polymer that forms gel beads with divalent cations (e.g., Ca²⁺). | Matrix for entrapment and as a base for covalent attachment [5] [35]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs) | Superparamagnetic support allowing easy separation via external magnetic field. | Facilitating catalyst recovery and reusability [12] [34]. |

The objective comparison of immobilization supports through defined efficiency metrics reveals a clear trade-off: no single support excels universally across all parameters. Traditional supports like alginate offer cost-effectiveness and good performance, particularly for encapsulation. In contrast, advanced materials like MNPs and COFs provide superior control, stability, and reusability, making them powerful tools for high-value applications like pharmaceutical synthesis [12] [7]. The choice of support is inherently application-specific, dictated by the required balance between activity, durability, and cost.

Future advancements are leaning toward intelligent design.