Extremozymes in Drug Discovery: Sourcing Next-Generation Biocatalysts from Nature's Extremes

This article explores the burgeoning field of extremophile enzymology and its profound implications for biomedical research and drug development.

Extremozymes in Drug Discovery: Sourcing Next-Generation Biocatalysts from Nature's Extremes

Abstract

This article explores the burgeoning field of extremophile enzymology and its profound implications for biomedical research and drug development. It provides a comprehensive analysis of the unique structural and functional adaptations of extremozymes that enable their stability under extreme conditions, making them superior biocatalysts. The content details advanced discovery methodologies, including metagenomics and synthetic biology, for accessing this untapped enzymatic reservoir. It further addresses key challenges in bioprocessing and optimization, such as heterologous expression and yield improvement, while offering a comparative evaluation of extremozymes against conventional enzymes. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current breakthroughs and future trajectories, highlighting how extremozymes are poised to overcome persistent hurdles in pharmaceutical manufacturing, from creating novel therapeutics to enabling more efficient and sustainable industrial bioprocesses.

Life at the Edge: Understanding Extremophiles and Their Unique Enzymatic Toolkit

Extremophiles are organisms that not only survive but thrive in extreme environments—habitats characterized by physical and chemical conditions once considered incompatible with life [1] [2]. These limits include extreme temperature, pressure, radiation, salinity, and pH levels [2]. The term "extremophile," derived from Latin extremus meaning 'extreme' and Ancient Greek philía meaning 'love,' was coined by MacElroy in 1974 [3] [4]. The study of these organisms has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of life's boundaries, revealing that approximately 75% of our planet hosts conditions considered extreme by human standards [1].

From a biotechnological perspective, extremophiles represent a cornerstone for innovation, particularly in enzyme sourcing and application. Their unique biological mechanisms, refined through evolution under harsh conditions, offer robust tools for industrial processes, pharmaceuticals, and environmental management [5] [6]. The resilience of extremophile-derived biomolecules, especially extremozymes, provides significant advantages in catalysis under conditions where conventional proteins would denature and fail [4] [7]. This guide provides a comprehensive taxonomic and methodological framework for extremophiles, contextualized within the critical endeavor of sourcing novel enzymes from these resilient organisms.

A Detailed Taxonomic Classification of Extremophiles

Extremophiles are classified based on the specific environmental parameter to which they are primarily adapted. Many organisms fall under multiple categories and are classified as polyextremophiles, such as Thermococcus barophilus, which is both thermophilic and piezophilic [2]. The following taxonomy outlines the major categories, their defining conditions, and representative examples.

Table 1: Taxonomic Classification of Major Extremophile Types

| Extremophile Type | Defining Environment | Optimal Growth Conditions | Representative Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | High temperature | >45°C [2] | Thermus aquaticus [8], Pyrococcus furiosus [6] |

| Hyperthermophile | Very high temperature | >80°C [2] | Pyrolobus fumarii (106-113°C) [3], Methanopyrus kandleri (up to 122°C) [6] [3] |

| Psychrophile | Low temperature | ≤15°C [2] | Psychrobacter sp. [1] [6] |

| Halophile | High salinity | ≥50 g/L dissolved salts [2] | Halorubrum lacusprofundi [8], Dunaliella salina [1] |

| Acidophile | Low pH | pH ≤3.0 [2] | Picrophilus oshimae (pH 0.06) [3] [2] |

| Alkaliphile | High pH | pH ≥9.0 [2] | Natronobacterium [2] |

| Piezophile (Barophile) | High pressure | >10 MPa [2] | Pyrococcus sp. [2], Thermococcus barophilus [2] |

| Radioresistant | High ionizing/UV radiation | 1,500-6,000 Gy [2] | Deinococcus radiodurans [4] [8], Rubrobacter [2] |

| Xerophile | Low water availability | Water activity (a_w) <0.8 [2] | Chroococcidiopsis [2] |

The diversity of extremophiles spans across all three domains of life: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya [1] [8]. While a large proportion, particularly the hyperthermophiles, belong to the Archaea, eukaryotic extremophiles such as the algae Dunaliella salina (halophile) and the fungus Thermomyces lanuginosus (thermophile) also exist [1] [3]. The cellular and molecular adaptations that enable this survival are the primary source of their biotechnological value.

Cellular and Molecular Adaptation Mechanisms

Extremophiles have evolved sophisticated biochemical, structural, and genomic adaptations to withstand environmental extremes. These mechanisms directly inform the search for stable enzymes, as they confer the robustness desired for industrial processes.

Thermal Adaptations

- Thermophiles and Hyperthermilles: Enhance protein stability through increased hydrophobic interactions, salt bridges, and disulfide bonds [6] [8]. Their proteins often feature shorter loops, more compact structures, and a higher proportion of charged and aromatic amino acids [6]. Genomically, they can display higher G+C content in tRNA and DNA, contributing to nucleic acid stability [6].

- Psychrophiles: Maintain protein flexibility and increased entropy at low temperatures by incorporating smaller, less bulky amino acid residues like glycine, reducing ion pairs and hydrophobic interactions [6] [8]. They produce antifreeze proteins (AFPs) that bind to ice crystals and inhibit their growth, preventing cellular damage [1] [8].

Osmotic and Ionic Stress Adaptations

- Halophiles utilize two primary strategies: they accumulate high internal concentrations of potassium ions to balance external osmotic pressure, or they synthesize and accumulate compatible solutes (e.g., glycerol, betaine) to protect cellular structures without interfering with enzymatic function [3] [8]. Their enzymes often have a high surface charge density of acidic amino acids to maintain solubility and function in high-salt conditions [7].

Pressure and Radiation Resistance

- Piezophiles produce an abundance of polyunsaturated fatty acids to maintain membrane fluidity at high pressure. They also accumulate piezolytes, such as trimethylamine oxide (TMAO), which stabilize cellular proteins against pressure-induced denaturation [8].

- Radioresistant organisms like Deinococcus radiodurans possess extremely efficient DNA repair mechanisms and express cellular detoxifying genes to mitigate oxidative damage. Some synthesize novel proteins that are intrinsically resistant to oxidative damage and small-molecule proteome shields [4] [8].

These adaptation mechanisms are encoded in the organism's genome. Recent machine learning analyses of over 700 extremophile genomes have revealed that adaptations to extreme temperature or pH imprint discernible patterns in their DNA. This "environmental genomic signature" can sometimes be stronger than the phylogenetic signal of ancestry, indicating a new dimension for discovering extremophilic traits [9].

Methodologies for Isolation, Screening, and Enzyme Characterization

The discovery of novel extremozymes requires a combination of traditional microbiological techniques and advanced molecular approaches. The following protocols provide a framework for the isolation and functional characterization of enzymes from extremophiles.

Sample Collection and Strain Isolation

- Source Environments: Target extreme habitats such as hot springs, deep-sea sediments, polar ice, hypersaline lakes, and acidic mines [5] [6]. For example, the Chilca salterns in Peru yielded a halotolerant Bacillus subtilis strain producing a novel L-asparaginase [5].

- In-Situ Conditions: Maintain in-situ conditions during sampling where possible. For deep-sea piezophiles, use pressure-retaining samplers. For anaerobes, use pre-reduced media and anaerobic chambers [6].

- Enrichment and Cultivation: Inoculate samples into selective media designed to mimic the physicochemical parameters of the source environment (e.g., temperature, pH, salinity, specific energy sources). Use serial dilutions and solid media to isolate pure colonies [6] [3]. Culture-dependent methods remain crucial for studying microbial physiology and metabolic pathways [6].

Functional Screening for Enzyme Activity

- Culture-Dependent Screening: Grow isolates on solid media containing substrate analogues to detect enzyme production. For example, screen for proteases on casein-containing media (clear zones indicate hydrolysis) or lipases on tributyrin agar [7]. A psychrophilic Psychrobacter sp. from Antarctica was isolated and found to produce cold-active lipases and proteases using such methods [7].

- Metagenomic Screening (Culture-Independent): Extract total DNA directly from environmental samples. Construct metagenomic libraries in bacterial hosts (e.g., Escherichia coli) and screen clones for desired enzymatic activities under challenging conditions (e.g., high temperature, extreme pH) [4] [7]. This approach allows access to the genetic potential of the vast majority of uncultured microbes [7].

Gene Identification and Heterologous Expression

- Sequence-Based Mining: Use known enzyme sequences as queries to search (meta)genomic databases for novel homologs. Machine learning techniques can predict enzymatic properties like optimal temperature and pH based on sequence features [7].

- Heterologous Expression: Clone the identified gene into an expression vector (e.g., pET series) and transform into a suitable host like E. coli or Komagataella pastoris for high-yield protein production [5] [7]. For example, the L-asparaginase from Bacillus subtilis CH11 was successfully expressed in E. coli [5].

Biochemical Characterization of Extremozymes

Once an enzyme is purified, a standard set of experiments determines its biotechnological potential:

- Optimal Temperature and Thermostability: Assay activity across a temperature gradient. Determine the half-life at the optimal temperature by incubating the enzyme and measuring residual activity over time. The L-asparaginase from B. subtilis CH11 had an optimum of 60°C and a half-life of nearly four hours at this temperature [5].

- Optimal pH and Stability: Assay activity across a pH range using different buffer systems.

- Effect of Additives: Test the influence of metal ions, detergents, chelating agents, and organic solvents on enzyme activity. The B. subtilis L-asparaginase was significantly enhanced by K⁺ and Ca²⁺ ions [5].

- Kinetic Parameters: Determine the Michaelis-Menten constants (Kₘ and Vₘₐₓ) to assess substrate affinity and catalytic efficiency.

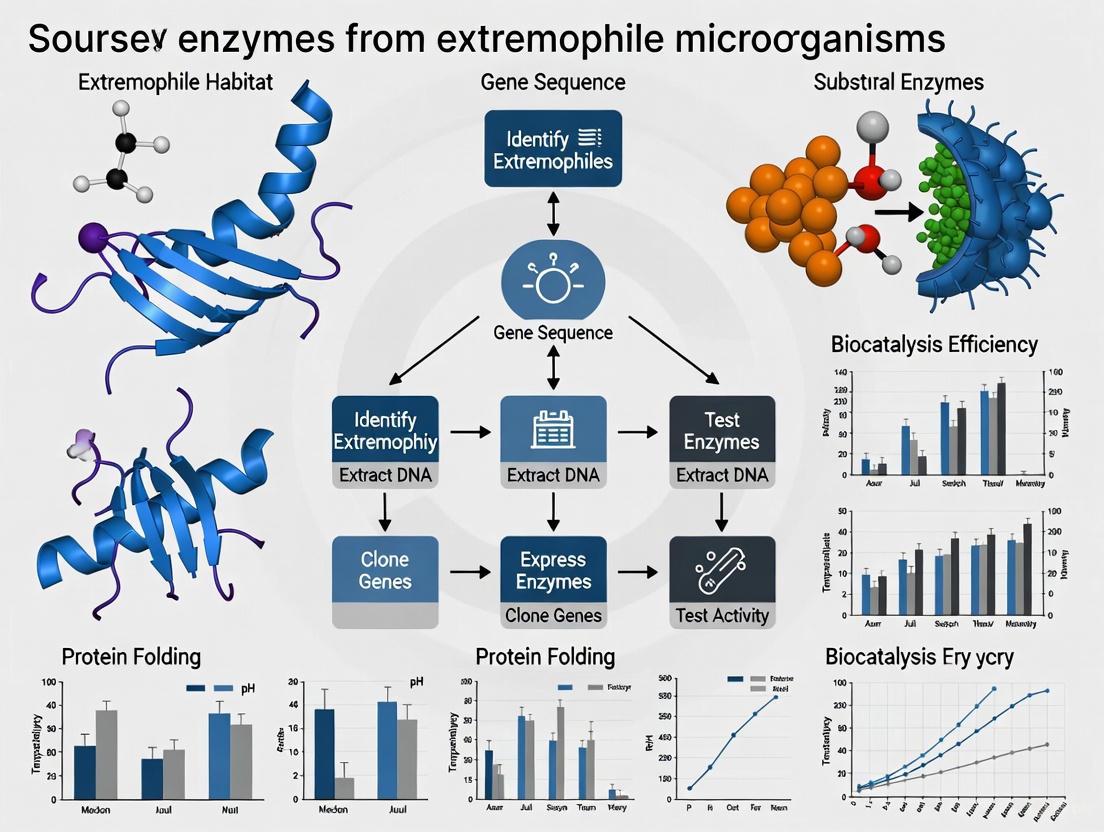

Diagram 1: A generalized workflow for the discovery and development of novel enzymes from extremophiles, integrating both culture-dependent and culture-independent approaches.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Extremophile Enzyme Research

The experimental pursuit of extremozymes requires specialized reagents and materials designed to maintain extreme conditions and assay functionality.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extremophile Enzyme Workflows

| Reagent / Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized Growth Media | To isolate and cultivate extremophiles by mimicking native physicochemical parameters. | Anaerobic media for piezophiles; high-salt media for halophiles (e.g., containing 50-250 g/L NaCl); low/high pH media for acidophiles/alkaliphiles [6] [3]. |

| Expression Vectors & Hosts | For heterologous expression and production of extremozymes. | Vectors: pET series for E. coli. Hosts: E. coli BL21(DE3) for general use; Halobacterium sp. NRC-1 for halophilic proteins [5] [7]. |

| Activity Assay Substrates | To detect and quantify enzymatic activity under various conditions. | p-Nitrophenyl derivatives (e.g., pNP-acetate for esterases); azocasein for proteases; chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates for specific hydrolases [7]. |

| Stability Enhancers | To maintain enzyme activity during purification and storage. | Reducing agents (e.g., DTT); metal ions (K⁺, Ca²⁺); compatible solutes (e.g., betaine, glycerol) [5]. |

| Detergents & Solvents | To test enzyme stability for industrial applications. | Ionic (SDS) and non-ionic (Tween) detergents; organic solvents (isopropanol, cyclohexane) [7]. |

Biotechnological Applications of Extremophiles and Extremozymes

The unique properties of extremophiles and their biomolecules have led to groundbreaking applications across multiple industries, with enzymes being the most significant commercial output.

Industrial and Pharmaceutical Enzymes

- Thermostable DNA Polymerases: The Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus revolutionized PCR technology, creating a market worth over $2 billion [3] [8]. Other thermostable polymerases like Pfu from Pyrococcus furiosus and Vent from Thermococcus litoralis offer higher fidelity [3].

- L-Asparaginase: A type II L-asparaginase from the halotolerant Bacillus subtilis CH11, isolated from the Chilca salterns in Peru, shows remarkable thermal stability (optimal activity at pH 9.0 and 60°C) and is used in cancer therapy and the food industry [5] [4].

- Detergent Enzymes: Proteases, lipases, and amylases from alkaliphiles and thermophiles are incorporated into detergents for their activity in high-pH and hot water conditions [4] [7]. A cold-active protease from Psychrobacter sp. is suitable for cold-washing products [7].

Bioremediation and Bioenergy

Extremophiles are deployed to degrade pollutants in environments where conventional microbes perish.

- Hydrocarbon Degradation: Thermophilic microbial communities possess enzymes capable of degrading hydrocarbons, indicating potential for remediating oil spills in various environments [6].

- Waste Processing: The enzyme proteolysin from Coprothermobacter proteolyticus operates in a wide pH and high-temperature range, making it suitable for remedying organic solid wastes [8].

- Biofuel Production: Extremophiles are exploited for biohydrogen and biobutanol production, leveraging their unique metabolic pathways that function under process-relevant extreme conditions [3].

Astrobiology and the Limits of Life

The study of extremophiles directly informs the search for extraterrestrial life. Organisms from environments analogous to those on other moons and planets serve as models for potential extraterrestrial life forms [5] [1]. For instance, thermophilic bacteria from Yellowstone are studied as analogs for potential life on Europa, and microbes from the hyper-arid Atacama Desert inform the search for life on Mars [6] [2]. Research has shown that certain extremophiles can survive the hyperacceleration of cosmic environments, the radiation levels on Mars, and the conditions of space, expanding the potential for habitability elsewhere in the universe [2].

Diagram 2: The logical relationship between environmental stress, the molecular adaptation mechanisms evolved in extremophiles, and the resulting enzyme properties that are valuable for biotechnological applications.

The taxonomy of extremophiles outlines a map of life's resilience, charting organisms that have evolved to occupy every conceivable niche on Earth. This systematic understanding is more than an academic exercise; it is a critical guide for sourcing novel enzymes with unparalleled stability and functionality. The continued exploration of extreme environments, coupled with advancements in genomics, metagenomics, and synthetic biology, promises to unlock a vast reservoir of untapped biocatalysts. These extremozymes hold the key to addressing pressing global challenges in sustainable industry, medicine, and environmental management, pushing the boundaries of biotechnology into ever more demanding and rewarding territories.

Extremozymes, the enzymes produced by extremophile microorganisms, exhibit remarkable structural stability and catalytic functionality under conditions that denature most proteins. These enzymes have evolved unique biochemical adaptations—including specific amino acid compositional biases, distinct structural flexibilities, and enhanced molecular bonding networks—that enable them to defy denaturation in extreme temperatures, pH levels, salinity, and pressure. The study of these survival strategies not only expands our understanding of protein biochemistry but also unlocks significant potential for biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications. This whitepaper examines the molecular mechanisms governing extremozyme resilience and provides technical guidance for their investigation and utilization within enzyme sourcing research.

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in ecological niches previously considered incompatible with life, including scorching hydrothermal vents, highly acidic or alkaline lakes, hypersaline waters, and frozen deserts [4]. These remarkable microorganisms, primarily from the domains Archaea and Bacteria, have evolved specialized enzymes known as extremozymes that maintain stability and functionality under extreme physicochemical stresses [10]. The intrinsic properties of extremozymes have revolutionized our approach to industrial biocatalysis, particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing where harsh process conditions often denature conventional enzymes.

From a commercial perspective, the global enzyme market is substantial and continues to grow, expected to reach approximately $7 billion, with extremophiles representing a significant untapped resource for novel biocatalysts [4] [11]. Landmark successes such as Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus have demonstrated the transformative potential of extremozymes in biotechnology [4] [10]. This whitepaper explores the biochemical strategies extremozymes employ to resist denaturation, framed within the broader context of sourcing enzymes from extremophile microorganisms for research and drug development.

Molecular Mechanisms of Stability and Activity

Extremozymes defy denaturation through sophisticated structural and chemical adaptations that vary significantly based on the environmental challenges they have evolved to withstand.

Thermal Adaptation Strategies

The thermal stability of extremozymes demonstrates a fundamental trade-off between activity and stability, with psychrophilic (cold-adapted) and thermophilic (heat-adapted) enzymes employing opposing strategies.

Table 1: Characteristic Temperature Parameters of Enzymes from Temperature-Adapted Organisms

| Organism Type | Mean Optimum Temperature (Topt) °C | Mean Melting Temperature (Tm) °C | Mean Temperature Gap (Tg) °C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Psychrophilic | 32.97 ± 2.16 | 55.02 ± 2.25 | 22.05 |

| Mesophilic | 55.03 ± 2.52 | 62.37 ± 2.02 | 7.34 |

| Thermophilic | 78.03 ± 2.25 | 86.77 ± 2.38 | 8.74 |

Data derived from meta-analysis of existing studies on temperature-adapted enzymes [12]

Psychrophilic enzymes exhibit a significantly larger gap between their optimum and melting temperatures (Tg) compared to mesophilic and thermophilic enzymes, suggesting their active sites are more thermolabile than the rest of the protein structure to maintain flexibility for catalysis at low temperatures [12]. This adaptation is achieved through:

- Decreased hydrophobic interactions and reduced proline and arginine content in rigid loop structures [13]

- Increased surface charge and decreased core hydrophobicity [11]

- Weakened intramolecular bonds including hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and aromatic interactions [13]

In contrast, thermophilic enzymes enhance their rigidity through:

- Increased proline content in loops that restricts conformational freedom [13]

- Enhanced arginine content which forms multiple hydrogen bonds to backbone carbonyl oxygens [13]

- Extended networks of salt bridges and hydrogen bonds [13]

- Oligomerization and chaperone assistance for additional stability [13]

Structural Adaptations to Other Extremes

Beyond temperature, extremozymes exhibit specialized adaptations to other environmental challenges:

- Halophilic enzymes in high-salinity environments feature elevated acidic amino acid content on their surfaces, allowing coordinated binding of water molecules and ions to maintain solvation and functionality [4] [1]

- Acidophilic and alkaliphilic enzymes maintain internal pH neutrality through specialized proton pumps and feature surface architectures resistant to pH-induced denaturation [10] [1]

- Barophilic enzymes from high-pressure environments possess reduced void volumes and specialized structural folds that resist compression [4] [1]

Experimental Approaches for Extremozyme Research

The study of extremozymes requires specialized methodologies to overcome challenges in cultivation, characterization, and production.

Discovery and Isolation Workflow

Diagram 1: Extremozyme Discovery Workflow

Key Methodological Protocols

Metagenomic Mining of Unculturable Extremophiles

Many extremophiles resist laboratory cultivation, necessitating culture-independent approaches [4]. This protocol involves:

- Environmental DNA Extraction: Sample collection from extreme habitats followed by direct DNA extraction using commercial kits modified for difficult matrices [4] [5]

- Sequencing and Assembly: High-throughput sequencing (Illumina, PacBio) followed by bioinformatic assembly and annotation [4]

- Functional Screening: Construction of metagenomic expression libraries in suitable hosts (e.g., E. coli) followed by activity-based screening under simulated extreme conditions [4] [5]

- Sequence-Based Screening: Identification of candidate genes via homology to known extremozymes or conserved domains [4]

Biochemical Characterization of Stability Parameters

Comprehensive characterization of extremozyme stability requires multi-faceted approaches:

Thermal Stability Assay

- Monitor enzyme activity at various temperatures to determine Topt

- Use differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) or circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to determine Tm

- Calculate Tg (Tg = Tm - Topt) as a key stability-activity parameter [12]

Structural Analysis

Kinetic Parameter Determination

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extremozyme Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Expression Systems | E. coli BL21, Bacillus subtilis, Pichia pastoris | Heterologous production of extremozymes | Codon optimization often required for high yield [5] |

| Stability Assay Kits | Thermofluor, Differential Scanning Calorimetry | Protein stability measurement | Use with extreme pH/ionic strength buffers [12] |

| Chromatography Media | His-tag affinity, Ion exchange, Hydrophobic interaction | Protein purification | High-salt or extreme pH buffers maintain stability [5] |

| Activity Assays | Fluorogenic/Chromogenic substrates | Enzyme kinetics determination | Adapt for extreme conditions (temperature, pH) [12] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | Rosetta, HoTMuSiC, PoPMuSiC | Stability prediction and design | Predict ΔΔGf and ΔTm of mutations [12] [14] |

Technological Applications and Future Directions

The unique properties of extremozymes have enabled significant advances across multiple industries, particularly pharmaceuticals:

- Therapeutic Enzymes: L-asparaginase from halotolerant Bacillus subtilis exhibits remarkable thermal stability (optimal activity at pH 9.0 and 60°C with a half-life of nearly four hours) for cancer treatment [4] [5]

- Antibiotic Development: Novel antimicrobial peptides from deep-sea thermophiles disrupt bacterial membranes through pore-forming mechanisms, bypassing existing resistance pathways [4]

- Biocatalysis: Thermophilic and halophilic enzymes enable green chemistry approaches under industrial conditions that traditionally required organic solvents [4] [11]

Future research directions focus on leveraging synthetic biology and computational design to enhance extremozyme functionality:

Diagram 2: Enzyme Engineering Pipeline

The integration of computational design with directed evolution has yielded remarkable successes, such as the development of formolase enzymes for carbon fixation pathways and Diels-Alderases for stereoselective cycloadditions [14]. These approaches are particularly valuable for designing extremozymes with enhanced stability or novel functions not found in nature.

Extremozymes represent nature's solution to biochemical challenges once considered insurmountable. Their ability to defy denaturation stems from precise molecular adaptations that balance stability and flexibility, activity and resilience. As our understanding of these mechanisms deepens through advanced genomic, structural, and computational approaches, the potential for leveraging extremozymes in pharmaceutical research and industrial biotechnology expands exponentially. The continued exploration of Earth's extreme environments, coupled with innovative engineering strategies, promises to unlock new generations of biocatalysts that will drive sustainable drug development and manufacturing processes.

The pursuit of sustainable and efficient biocatalysts has positioned extremophiles—organisms thriving in extreme environments—as a cornerstone of modern biotechnology. This whitepaper frames the exploration of extremozymes within the broader thesis that the unique biochemical adaptations of extremophile microorganisms are an unparalleled resource for advancing biomedical science. Enzymes derived from these resilient organisms, known as extremozymes, exhibit exceptional stability and functionality under harsh conditions that would denature their mesophilic counterparts [15] [16]. Their intrinsic robustness translates directly into advantages for industrial and therapeutic applications, including longer shelf lives, the ability to function under non-standard process conditions, and novel catalytic activities [4] [17].

This guide provides an in-depth technical analysis of three major classes of biomedically-relevant extremozymes: polymerases, proteases, and L-asparaginases. It summarizes their unique biochemical properties, details experimental protocols for their discovery and characterization, and presents a curated toolkit for researchers, thereby offering a comprehensive resource for scientists and drug development professionals engaged in harnessing these powerful biological catalysts.

Extremophiles are classified based on the specific environmental challenges they overcome. Table 1 outlines the major categories of extremophiles and the corresponding adaptive strategies that inform the discovery of novel extremozymes [1] [4].

Table 1: Major Types of Extremophiles and Their Adaptive Strategies

| Type of Extremophile | Defining Environment | Key Adaptive Mechanisms | Relevant Extremozyme Classes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | High temperatures (>45-80°C) [17] | Increased protein rigidity, charged surface residues, dense hydrophobic core [15] [16] | Polymerases, Proteases |

| Psychrophile | Low temperatures (<20°C) [17] | Enhanced protein flexibility, reduced hydrophobic interactions, surface loop modifications [1] [16] | L-Asparaginases, Proteases |

| Halophile | High salinity (>3.5% NaCl) [1] | Abundant acidic surface residues, production of compatible solutes [1] [4] | L-Asparaginases |

| Acidophile/Alkaliphile | Extreme pH (<5 or >9) [1] | Buffered active sites, specialized proton pumps, altered surface charge [1] [17] | Proteases |

| Piezophile | High pressure | Structural modifications to resist compression [1] [17] | Polymerases, Proteases |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the discovery and development of novel extremozymes, from initial sampling to a commercial enzyme product.

Major Classes of Biomedically-Relevant Extremozymes

Polymerases

DNA polymerases from extremophiles have revolutionized molecular biology. Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus is the paradigmatic example, enabling the automation of PCR due to its thermostability [4]. Current research focuses on discovering and engineering novel thermostable and salt-tolerant polymerases to advance diagnostic and sequencing technologies.

Representative Example: A study by Sun et al. combined droplet-based microfluidics with conventional site-directed mutagenesis to screen for polymerase mutants with enhanced salt tolerance [15]. The most promising variant, SZ_A, demonstrated not only improved salt tolerance but also increased processivity and exonuclease deficiency, making it particularly suitable for advanced nanopore sequencing applications [15].

Experimental Protocol for Salt-Tolerant Polymerase Engineering:

- Gene Library Construction: Create a library of polymerase mutant genes via site-directed mutagenesis, focusing on substituting regular sites with conserved amino acids [15].

- Microfluidic Compartmentalization: Encapsulate individual mutant genes and a fluorescent reporter assay for polymerase activity within water-in-oil droplets. This allows for high-throughput, single-cell analysis [15].

- High-Throughput Screening: Sort the droplets based on fluorescence intensity, which correlates with enzymatic activity under high-salt conditions, to identify lead variants [15].

- Characterization: Express, purify, and biochemically characterize the lead variant (e.g., SZ_A) to confirm improved salt tolerance, processivity, and fidelity [15].

Proteases

Extremophilic proteases are characterized by their stability and activity under harsh conditions such as high temperatures, extreme pH, and the presence of reducing agents. They are invaluable in industries ranging from detergents to pharmaceuticals.

Representative Example: Røyseth et al. characterized globupain, a novel C11 protease from uncultivated Archaeoglobales in the Soria Moria hydrothermal vent system [15]. This enzyme exhibits high thermostability and optimal activity under low pH and high reducing conditions, underscoring its potential for specialized biotechnological applications [15].

Experimental Protocol for Novel Protease Characterization:

- Gene Identification: Mine metagenomic databases (e.g., MEROPS-MPRO) to identify novel protease gene sequences from extreme environments [15].

- Recombinant Expression: Clone the gene into an expression vector (e.g., pET series) and express it recombinantly in E. coli [15] [18].

- Zymogen Activation: Generate and purify mutant variants to probe the function of the zymogen and the activation mechanism. For globupain, 13 mutant variants were evaluated [15].

- Biochemical Assay: Assess protease activity using specific substrates (e.g., casein or synthetic peptides) across a range of pH and temperatures. Measure kinetic parameters (KM, kcat) and stability under various denaturing conditions [15].

L-Asparaginases

L-Asparaginases (L-ASNase, EC 3.5.1.1) are a critical class of biomedical extremozymes. Their anti-leukemic action is based on hydrolyzing circulating L-asparagine in the blood, selectively starving malignant lymphoblastic cells that cannot synthesize this amino acid [19] [20]. Research focuses on finding isoforms with high substrate affinity, low glutaminase activity (to reduce side effects), and enhanced stability under physiological conditions [21] [20].

Representative Examples:

- Psychrophilic L-ASNase from Pseudomonas sp. PCH199: Isolated from Himalayan soil, this periplasmic enzyme is active over a wide pH range and is remarkably stable at 37°C, retaining 100% activity for over 200 minutes—a key pharmacological advantage. It demonstrated significant cytotoxicity against K562 blood cancer cells (IC50 0.309 U/mL) [19].

- Class 3 L-ASNases from Rhizobium etli: The ReAIV and ReAV isoforms represent a novel structural class. ReAIV is constitutive and thermostable (optimal activity at 45-55°C), while ReAV is inducible and thermolabile. Both are zinc-metalloenzymes, with Zn²⁺ boosting their activity by 32% and 56%, respectively [22].

Experimental Protocol for L-ASNase Cytotoxicity Assessment:

- Enzyme Production & Purification: Isolate the enzyme from the native host or produce it recombinantly. Optimize production using Response Surface Methodology. Purify using chromatographic techniques or an osmotic shock method for periplasmic extracts [19].

- Activity & Kinetic Assay: Measure L-ASNase activity spectrophotometrically by quantifying ammonia release with Nessler's reagent. Perform assays in optimal buffer (e.g., 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) at 37°C to determine kinetic parameters (KM, Vmax) [19].

- Cell Culture Assay: Culture target cancer cell lines (e.g., K562 leukemic cells) and normal control cell lines (e.g., IEC-6) under standard conditions [19].

- Cytotoxicity & Apoptosis Assay: Incubate cells with purified L-ASNase for 24-48 hours. Determine the IC50 value using a cell viability assay (e.g., MTT). Assess apoptotic morphological changes in nuclei via DAPI staining [19].

Table 2: Biochemical Properties of Selected Biomedical Extremozymes

| Enzyme | Source Organism | Optimal Activity | Key Biochemical Properties | Biomedical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SZ_A Polymerase | Engineered variant | High Salt Conditions | Enhanced salt tolerance, processivity, exonuclease-deficient [15] | Nanopore sequencing, molecular diagnostics |

| Globupain (Protease) | Archaeoglobales (Archaea) | Low pH, High Reducing Conditions | High thermostability, C11 protease family [15] | Industrial catalysis under denaturing conditions |

| L-ASNase PCH199 | Pseudomonas sp. PCH199 | pH 8.5, 60°C | KM = 0.164 mM, Stable at 37°C, Cytotoxic (IC50 0.309 U/mL) [19] | Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia (ALL) treatment |

| L-ASNase ReAIV | Rhizobium etli | 45-55°C | KM = 1.5 mM, kcat = 770 s⁻¹, Zinc-activated (KD = 1.2 μM) [22] | Potential ALL therapeutic, model for enzyme engineering |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the experimental workflows for extremozyme research, as cited in the literature.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extremozyme R&D

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Usage in Context |

|---|---|---|

| pET Expression Vectors | Heterologous protein expression in E. coli with IPTG-inducible T5/T7 promoters [18] | Cloning and overexpression of recombinant catalase, laccase, and amine-transaminase [18]. |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | Robust, genetically defined host for recombinant protein production [21] | Expression host for ten different recombinant L-ASNases for comparative study [21]. |

| Ni-NTA HisTrap Column | Affinity chromatography for purifying recombinant His-tagged proteins [21] | Purification of recombinant L-ASNases [21]. |

| Nessler's Reagent | Spectrophotometric detection of ammonia for L-ASNase activity assays [19] | Quantitative estimation of L-ASNase activity by measuring ammonia liberation from L-asparagine [19]. |

| Response Surface Methodology (RSM) | Statistical optimization of culture conditions for enhanced enzyme production [19] | Optimizing L-ASNase production from Pseudomonas sp. PCH199 at flask scale [19]. |

| Droplet-Based Microfluidics | High-throughput screening platform for enzyme variants [15] | Screening a library of polymerase mutants for enhanced salt tolerance [15]. |

Technical Considerations and Future Directions

While the potential of extremozymes is vast, their path from discovery to application presents challenges. A major hurdle is that an estimated 99% of microorganisms are unculturable using standard techniques, creating significant "microbial dark matter" [17]. Solutions include culture-independent metagenomic approaches and advanced bioinformatics to mine sequencing data for novel genes [18] [17].

Furthermore, producing extremozymes from their native hosts is often difficult due to low biomass yields and slow growth rates [17]. The primary solution is heterologous expression in mesophilic workhorses like E. coli. However, this can lead to issues such as improper folding, inclusion body formation, and an inability to incorporate essential metal cofactors [17]. Co-expression of molecular chaperones and refolding strategies are critical to overcoming these obstacles [17].

The future of the field lies in interdisciplinary strategies. Directed evolution and rational protein design are being used to enhance the stability and efficiency of existing extremozymes [15]. The integration of CRISPR-based pathway engineering and machine learning for predicting protein structure and function will further accelerate the discovery and optimization of these powerful biocatalysts [4] [20]. As these technologies mature, extremozymes will play an increasingly pivotal role in providing innovative, sustainable solutions to challenges in biomedicine and beyond.

Extremophiles represent nature's ultimate survivors, thriving in ecological niches previously considered incompatible with life, from scorching hydrothermal vents and highly acidic lakes to hypersaline waters and frozen Antarctic deserts [4] [5]. These remarkable organisms have evolved unique biochemical adaptations that enable their proteins to maintain structural integrity and functional activity under extreme conditions that would rapidly denature most conventional proteins [23] [24]. The study of extremophile adaptations provides invaluable insights into the fundamental determinants of protein stability, offering a blueprint for engineering robust enzymes for pharmaceutical applications, industrial processes, and sustainable technologies [25] [26].

The resilience of extremophile-derived proteins, known as extremozymes, stems from sophisticated evolutionary adaptations at molecular levels, including strategic amino acid substitutions, enhanced structural rigidity, and specialized stabilization mechanisms [24] [27]. Understanding these mechanisms is particularly valuable for drug development professionals seeking to create more stable therapeutic proteins, improve enzyme-based manufacturing processes, and develop novel biocatalysts for synthesizing pharmaceutical intermediates [4] [28]. This whitepaper examines the principal adaptations that confer exceptional stability to extremophile proteins, details methodologies for studying these remarkable molecules, and explores their growing impact on biotechnological and pharmaceutical applications.

Extremophile Diversity and Habitat Specificity

Extremophiles are classified based on the specific environmental challenges they have conquered, with each group exhibiting distinct adaptive strategies at the protein level [4] [10]. Thermophiles and hyperthermophiles thrive at elevated temperatures (45°C-122°C), with proteins engineered to resist thermal denaturation through strengthened molecular interactions [10] [28]. Psychrophiles inhabit permanently cold environments (-12°C to 10°C) and produce enzymes with enhanced structural flexibility to maintain catalytic efficiency at low temperatures [23] [10]. Halophiles require high salt concentrations (5-30%) for growth and possess predominantly acidic proteomes that remain soluble and functional under saline conditions [23] [27]. Acidophiles and alkaliphiles flourish at extreme pH values (0-3 or 9-12, respectively), with specialized mechanisms to maintain internal pH homeostasis while developing proteins that resist pH-induced denaturation [23] [10]. Additionally, poly-extremophiles can simultaneously withstand multiple environmental stresses, representing particularly valuable sources of robust enzymes for industrial applications [10].

Table 1: Classification of Extremophiles and Their Habitat Conditions

| Extremophile Type | Growth Conditions | Representative Species | Key Protein Adaptations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophile | 45°C-80°C | Pyrococcus furiosus | Increased salt bridges, hydrophobic core packing |

| Hyperthermophile | >80°C (up to 122°C) | Methanopyrus kandleri | Enhanced ionic networks, oligomerization |

| Psychrophile | -12°C to 10°C | Psychromonas ingrahamii | Increased structural flexibility, reduced hydrophobic core |

| Halophile | 5-30% salt concentration | Halorhodospira halophila | Acidic surface residues, high surface hydration |

| Acidophile | pH 0-3 | Picrophilus oshimae | Dense surface charge networks, acid-resistant folds |

| Alkaliphile | pH 9-12 | Bacillus alkaliphilus | Strategic deamidation avoidance, surface charge shielding |

Molecular Mechanisms of Protein Stabilization in Extreme Environments

Amino Acid Composition and Structural Plasticity

Comparative genomic and structural analyses reveal that extremophilic proteins exhibit statistically significant differences in amino acid composition compared to their mesophilic counterparts [27]. Thermophilic proteins display a marked preference for small nonpolar amino acids (glycine, alanine, valine) that enable tighter core packing and reduce conformational entropy costs upon folding [24] [27]. Additionally, thermostable proteins show increased frequencies of charged residues (arginine, glutamic acid) that facilitate the formation of stabilizing salt bridges across protein domains [27]. Psychrophilic enzymes, in contrast, often contain higher proportions of neutral polar residues (asparagine, serine) and reduced arginine content, conferring the structural flexibility necessary for catalysis at low thermal energies [23] [27].

Halophilic proteins employ a distinct strategy characterized by a highly acidic surface with abundant aspartic and glutamic acid residues, creating a hydrated shield that prevents aggregation and precipitation at high ionic strength [23] [27]. This adaptation results in a significantly lower isoelectric point (pI) compared to non-halophilic orthologs, with statistical analysis showing a significant difference (p < 0.0091) in this parameter [27]. Alkaliphilic proteins, meanwhile, minimize labile residues such as asparagine and glutamine that are susceptible to deamidation at high pH, while incorporating strategic arginine residues that maintain positive surface charges under alkaline conditions [27].

Table 2: Amino Acid Composition Trends in Extremophile Proteins

| Amino Acid | Thermophiles | Psychrophiles | Halophiles | Acidophiles | Alkaliphiles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alanine | ↑↑ | → | ↑ | ↑ | → |

| Glycine | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | → |

| Valine | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑ | → | ↑ |

| Isoleucine | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Arginine | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↓ | → | ↑↑ |

| Lysine | ↓ | → | ↓↓ | ↓ | → |

| Aspartic Acid | → | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ |

| Glutamic Acid | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↓ |

| Serine | ↓ | ↑↑ | ↓ | ↓ | → |

| Asparagine | ↓ | ↑ | ↓↓ | ↓ | ↓↓ |

| Cysteine | ↓ | → | ↓ | ↓ | → |

Key: ↑↑ = Strong increase; ↑ = Moderate increase; → = Neutral/no clear trend; ↓ = Moderate decrease; ↓↓ = Strong decrease

Structural and Physicochemical Determinants of Stability

The exceptional stability of extremophile proteins arises from a complex interplay of structural and physicochemical factors that have been fine-tuned through evolutionary selection. Salt bridges (ionic interactions between positively and negatively charged residues) play a particularly crucial role in thermostabilization, with hyperthermophilic proteins containing significantly more salt bridges than their mesophilic counterparts [24] [27]. These electrostatic networks provide enhanced rigidity without compromising functional flexibility, creating a "structural homeostasis" that resists thermal perturbation [27].

Hydrophobic core optimization represents another key stabilization strategy, particularly in thermophiles [24] [27]. Statistical analyses reveal that thermostable proteins exhibit approximately 45-59% hydrophobicity in their core regions, achieved through increased aliphatic residue content and enhanced packing density [27]. This compact interior minimizes solvent-accessible surface area and creates an energetically unfavorable environment for unfolding. Similarly, hydrogen bonding networks are often enhanced in extremophilic proteins, with thermostable enzymes frequently containing additional main-chain and side-chain hydrogen bonds that collectively contribute to thermal resistance [24].

Psychrophilic proteins have evolved opposite adaptations, with reduced hydrophobic interactions, fewer salt bridges, and increased surface flexibility that maintain activity at temperatures where excessive rigidity would impede necessary conformational changes for catalysis [23]. These structural modifications lower the activation energy required for enzymatic function in cold environments, demonstrating how protein stability mechanisms are precisely calibrated to environmental conditions [23] [27].

Experimental Methodologies for Studying Extremophile Proteins

Metagenomic Discovery Pipelines

Traditional cultivation-based approaches for studying extremophiles are often limited, as many resistant microorganisms cannot be grown under laboratory conditions [29] [28]. Metagenomic sequencing has revolutionized extremophile bioprospecting by enabling direct analysis of genetic material from environmental samples without the need for cultivation [5] [29] [28]. This approach involves extracting total DNA from extreme environments, sequencing the collective metagenome, and computationally identifying putative extremozyme genes through homology searching and functional prediction [29].

A recent advanced computational pipeline demonstrates the power of this approach for sustainable enzyme discovery [29]. This methodology integrates traditional bioinformatic techniques with modern structural prediction algorithms to identify novel enzymes from existing metagenomic datasets, minimizing the need for additional environmental sampling [29]. As a proof of concept, this pipeline identified 11 candidate β-galactosidases from deep-sea hydrothermal vent metagenomes, with 10 showing in vitro activity and one (βGal_UW07) exhibiting exceptional thermostability and pH resistance [29].

Structure-Function Characterization Techniques

Once identified, extremophile proteins undergo rigorous biochemical characterization to quantify their stability parameters and elucidate structure-function relationships. Thermal stability assays measure residual activity after incubation at elevated temperatures, with extremozymes like the hyperthermophilic 3-quinuclidinone reductase (SbQR) maintaining optimal activity at ≥95°C [28]. Spectroscopic techniques including circular dichroism (CD) and fluorescence spectroscopy monitor structural integrity under denaturing conditions, while X-ray crystallography provides atomic-resolution structures that reveal stabilization mechanisms such as salt bridge networks and hydrophobic core packing [24] [27].

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations complement experimental approaches by modeling protein behavior at different temperatures, revealing how extremophile proteins maintain their folded state under conditions that destabilize mesophilic orthologs [28] [27]. These simulations have demonstrated that thermophilic proteins exhibit reduced structural fluctuation at high temperatures and more extensive hydrogen bonding networks compared to their mesophilic counterparts [27]. For halophilic proteins, MD simulations visualize how surface hydration and electrostatic interactions prevent aggregation in high-salt environments [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Extremophile Protein Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Metagenomic Libraries | DNA resources from extreme environments | Gene discovery without cultivation [29] |

| Heterologous Expression Systems | Production of extremozymes in model hosts | E. coli BL21 for SbQR expression [28] |

| Specialized Vectors | Plasmid systems for protein production | pGEX-6p-1 GST-fusion system [28] |

| Thermostable Polymerases | PCR amplification of extremophile genes | Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus [23] [4] |

| Chromatography Media | Protein purification under various conditions | Immobilized metal affinity chromatography [28] |

| Extremophile Culture Collections | Reference organisms for comparative studies | DSMZ and ATCC extremophile strains [10] |

| Specialized Growth Media | Cultivation of extremophiles | High-salt or pH-adjusted media [10] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Industrial Biotechnology

The unique properties of extremophile-derived proteins have enabled significant advances across multiple biotechnological domains, particularly in pharmaceutical manufacturing and industrial biocatalysis. Thermostable DNA polymerases such as Taq polymerase from Thermus aquaticus have revolutionized molecular biology by enabling the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), with sales exceeding $1 billion annually [23] [4]. L-asparaginases from halotolerant Bacillus subtilis strains exhibit remarkable thermal stability (optimal activity at pH 9.0 and 60°C with a half-life of nearly four hours), making them valuable for cancer therapy and food processing applications [5].

Recent discoveries highlight the growing pharmaceutical relevance of extremozymes. The hyperthermophilic 3-quinuclidinone reductase (SbQR) from hot spring metagenomes represents the first known hyperthermophilic enzyme in its class, displaying strict stereoselectivity for producing (R)-3-quinuclidinol—a key intermediate in drugs for obstructive pulmonary disease, urinary incontinence, and Parkinson's disease [28]. Similarly, uricase from Thermoactinospora rubra (TrUox) exhibits high catalytic efficiency at neutral pH and remarkable thermostability, maintaining activity after 4 days at 50°C, making it a promising candidate for therapeutic applications in hyperuricemia treatment [25].

Beyond pharmaceuticals, extremozymes have significant applications in environmental bioremediation. Cadmium-resistant strains of Bacillus cereus capable of sequestering multiple heavy metals offer immediate potential for cleaning contaminated soils and waters [25]. The discovery of biosurfactants from thermophilic Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains, with antimicrobial activity enhanced under varying salt conditions, demonstrates how extreme environments modulate supramolecular structures and bioactivity for environmental and therapeutic applications [25].

The study of extremophile adaptations has fundamentally advanced our understanding of protein stability, revealing nature's sophisticated strategies for maintaining structural and functional integrity under environmental extremes. These insights are increasingly valuable for addressing contemporary challenges in pharmaceutical development, industrial biotechnology, and environmental sustainability. As genetic, computational, and bioprospecting tools continue to advance, the translation of extremophilic adaptations into practical applications is accelerating [25] [26].

Future research directions will likely focus on integrating multi-omics approaches with advanced cultivation methods to explore the ecological roles and biotechnological potential of newly discovered extremophiles [4]. The development of genetic tools for extremophilic archaea and bacteria will enable more sophisticated manipulation of these organisms and their pathways [26]. Additionally, computational pipelines that leverage existing metagenomic datasets will facilitate sustainable bioprospecting while minimizing environmental impact [29]. As these technologies mature, extremophiles will continue to provide innovative solutions to global challenges in health, industry, and environmental sustainability, while revealing fundamental truths about life's remarkable capacity to adapt and thrive at the very boundaries of existence.

From Discovery to Drug Development: Methodologies and Biomedical Applications of Extremozymes

Less than 1% of environmental microorganisms can be cultivated using standard laboratory techniques, creating a significant "cultivation barrier" that has historically limited our access to nature's enzymatic diversity [30]. This is particularly problematic in the context of extremophile microorganisms, which thrive under conditions of high temperature, salinity, pressure, or pH, and represent a unique source of robust enzymes (extremozymes) with exceptional stability and activity under harsh industrial conditions [31] [32]. Metagenomics, defined as the direct analysis of microbial genomes within environmental samples, bypasses this cultivation requirement by allowing researchers to access the genetic material of entire microbial communities regardless of their cultivability [30]. This technical guide examines integrated metagenomic and function-based pipelines specifically framed within enzyme discovery from extremophiles, providing researchers with advanced methodologies to unlock this untapped reservoir of biocatalytic potential for drug development and industrial applications.

Metagenomic Approaches: Core Methodologies and Workflows

Metagenomic enzyme discovery comprises two complementary approaches: sequence-based metagenomics (which identifies genes based on homology to known sequences) and function-based metagenomics (which identifies genes through expression and phenotypic detection of desired activities) [30]. The following sections detail the experimental protocols and computational workflows for implementing these methodologies.

Sequence-Based Metagenomics: A Computational Pipeline

Sequence-based metagenomics relies on the extraction, sequencing, and in silico analysis of environmental DNA to identify novel enzyme-encoding genes based on sequence similarity and conserved motifs.

Table 1: Key Steps in Sequence-Based Metagenomic Analysis

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Reagents/Tools | Application to Extremophiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample Collection | Collect biomass from extreme environments (thermal vents, hypersaline lakes, acidic mines) using environment-specific sterilized samplers | RNAlater, liquid nitrogen, sterile containers | Target environments matching desired enzyme stability (e.g., thermophiles for heat-stable enzymes) |

| DNA Extraction | Use commercial kits with modifications for difficult-to-lyse cells (extended bead-beating, enzymatic lysis) | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit, lysozyme, proteinase K, SDS | Critical step for extremophiles with robust cell walls; requires optimization for different extremes |

| Library Construction & Sequencing | Fragment DNA, size-select, and prepare libraries for next-generation sequencing (NGS) | Illumina platforms, PacBio, fragmentation enzymes, adapters | High GC-content common in thermophiles requires specialized library prep protocols |

| Bioinformatic Analysis | Assemble contigs, predict genes, and perform homology searches against enzyme databases | QIIME 2, FastQC, Trimmomatic, BLAST+, HMMER | Use specialized databases (e.g., CAZy, MEROPS) with extremophile sequences |

| Gene Annotation | Identify open reading frames and annotate based on conserved domains and motifs | Pfam, InterPro, COG, KEGG | Focus on catalytic domains known for stability in extreme conditions |

The sequence-based workflow enables researchers to rapidly screen vast metagenomic datasets for potentially novel extremozymes. For example, this approach has successfully identified novel extremophilic lipases and esterases from metagenomic libraries of tidal flat sediments and other extreme environments [32]. These enzymes exhibit robust functional properties including thermostability, organic solvent resistance, and activity at extreme pH values—attributes highly desirable for industrial applications and drug development pipelines.

Function-Based Metagenomics: Activity-Driven Screening

Function-based metagenomics focuses on direct phenotypic detection of desired enzymatic activities following heterologous expression of metagenomic DNA, enabling discovery of completely novel enzymes without prior sequence knowledge.

Table 2: Function-Based Screening Approaches for Extremozyme Discovery

| Screening Method | Mechanism | Detection Principle | Advantages for Extremozymes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate-Induced Gene Expression (SIGEX) | Catabolic genes activated by substrate presence induce GFP expression | FACS sorting of GFP-positive cells | High-throughput screening for metabolic pathways active in extreme conditions |

| Metabolite-Regulated Expression (METREX) | Detection of quorum-sensing molecules or metabolites | HPLC-MS, biosensor systems | Identifies enzymes producing or modifying signaling molecules in extremophiles |

| Activity-Based Probing | Molecular probes bind to enzymes performing specific functions | Fluorescently-labeled probes + cell sorting | Direct identification of lignocellulose-degrading microbes in complex communities [33] |

| Plate-Based Assays | Expression of metagenomic DNA in suitable host on selective media | Chromogenic/fluorogenic substrates, zone-of-clearing | Simple implementation for hydrolytic enzymes (lipases, proteases, cellulases) |

The function-based approach was successfully implemented in a recent pipeline developed at Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, where researchers combined molecular probes with cell isolation methods to identify lignocellulose-eating microbes within a complex community [33]. This pipeline enabled the identification of a specific population of cells that metabolize lignocellulose—a key plant-derived microbial food source—from among millions of cells, demonstrating how targeted function-based approaches can link individual microbes with specific activities.

Figure 1: Function-Based Metagenomic Discovery Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from environmental sample collection to industrial application of novel enzymes.

Advanced Bioinformatics and Computational Tools

The complexity of metagenomic data necessitates sophisticated bioinformatic tools for meaningful analysis. Recent advances have produced specialized workflows and algorithms specifically designed for enzyme discovery from complex microbial communities.

Cloud-Based Dockerized Workflows for Metagenomic Analysis

Modern bioinformatics approaches utilize containerized workflows to ensure reproducibility and accessibility. One such workflow, designed for biofilm metagenomics analysis, splits the analytical process into five submodules [34]:

- Concept Inventory and Workflow Introduction - Foundational knowledge and project setup

- Metagenome Data Preparation and QC - Quality control using FastQC, MultiQC, and Trimmomatic

- Microbiome Analysis - Taxonomic profiling with QIIME 2

- Biomarker Discovery - Functional potential prediction with PICRUSt2

- Microbiome Community Analysis - Advanced statistical analysis and visualization

This containerized approach allows researchers with minimal bioinformatics expertise to implement sophisticated analyses while maintaining reproducibility and adherence to FAIR (Findability, Accessibility, Interoperability, and Reusability) data principles [34].

Computational Inference of Enzyme Activity

Beyond identification of enzyme-encoding genes, computational tools can now infer enzyme activities from post-translational modification (PTM) profiling data. The JUMPsem program uses structural equation modeling (SEM) to infer enzyme activity from phosphoproteome, ubiquitinome, and acetylome data [35]. This approach:

- Estimates latent variables (enzyme activities) that cannot be directly measured

- Accounts for interactions among enzymes within biological systems

- Incorporates measurement errors in observed variables

- Can establish novel enzyme-substrate relationships through motif sequence searching

For extremophile research, such computational approaches enable researchers to predict enzyme functionality directly from sequencing data, prioritizing the most promising candidates for heterologous expression and characterization.

Figure 2: Computational Enzyme Activity Inference with JUMPsem. This diagram shows how the JUMPsem program integrates multiple data sources to infer enzyme activities and discover novel relationships.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of metagenomic discovery pipelines requires specific reagents and computational resources. The following table catalogs essential materials for establishing these workflows in a research setting.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Metagenomic Enzyme Discovery

| Category | Specific Product/Kit | Function in Workflow | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit | High-quality metagenomic DNA extraction from environmental samples | Optimal for soil and sediment samples; modified protocols for extreme environments |

| Library Construction | Illumina DNA Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing libraries from metagenomic DNA | Compatible with low-input samples; essential for maximizing sequence coverage |

| Cloning Vectors | pCC1FOS, pET expression systems | Construction of metagenomic libraries and heterologous expression | Fosmid vectors for large insert sizes; expression vectors for functional screening |

| Expression Hosts | E. coli strains (BL21, Rosetta) | Heterologous expression of metagenomic DNA | Codon-optimized strains critical for extremozyme expression |

| Screening Substrates | Chromogenic/fluorogenic substrate analogs | Detection of enzymatic activity in functional screens | Estrogen substrates for lipases/esterases; AZCL-polysaccharides for glycosidases |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QIIME 2, Trimmomatic, BLAST+ | Data processing, taxonomic profiling, sequence analysis | Essential for sequence-based discovery; containerized versions ensure reproducibility |

| Cloud Platforms | Google Cloud Platform, AWS | Computational resources for data-intensive analyses | Enables scaling of bioinformatic analyses without local infrastructure |

Applications in Extremophile Enzyme Discovery

Metagenomic approaches have proven particularly valuable for discovering novel enzymes from extremophilic microorganisms, with significant implications for pharmaceutical development and industrial biotechnology.

Mining Extreme Environments

Extremophilic fungi and other microorganisms from harsh environments represent a promising source of novel enzymes for agricultural and pharmaceutical applications [31]. These extremotolerant and extremophilic fungi offer unique attributes including:

- Ubiquity across diverse extreme habitats

- Morphological diversity (filamentous, yeasts, polymorphic)

- Endurance in harsh environments (high salinity, temperature, pH)

- Enhanced plant growth promotion under stress conditions

Research has demonstrated the potential of extremophilic fungi in alleviating salinity, drought, and other abiotic stresses in crops, highlighting their dual application in agriculture and enzyme production [31].

Industrial and Therapeutic Applications

Enzymes discovered through metagenomic approaches from extremophiles have diverse applications:

- Thermostable polymer-degrading enzymes for biomass conversion

- Organic solvent-tolerant lipases and esterases for pharmaceutical synthesis

- Alkaline proteases for detergent formulations

- Cold-adapted enzymes for food processing and bioremediation

The robustness of extremozymes—specifically their stability at extreme temperatures, pH values, and salinity levels—makes them particularly attractive for industrial processes where conventional enzymes would rapidly denature [32]. Additionally, their novel structures and mechanisms provide insights for engineering improved biocatalysts for pharmaceutical applications.

Metagenomic and function-based discovery pipelines have fundamentally transformed our approach to enzyme discovery from extremophilic microorganisms. By breaking the cultivation barrier, these methodologies provide access to the vast functional potential of uncultured microbial diversity, enabling identification of novel biocatalysts with properties tailored for pharmaceutical development and industrial applications.

Future advancements in this field will likely focus on integration of multi-omics data (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, metabolomics) for more comprehensive functional insights, machine learning approaches for predictive enzyme discovery, and single-cell metagenomics to resolve complex community structures at higher resolution. Furthermore, the continued development of user-friendly, cloud-based bioinformatics platforms will democratize access to these powerful methodologies, enabling broader adoption across the research community.

As climate change and environmental sustainability concerns intensify, the demand for robust, efficient biocatalysts will continue to grow. Metagenomic approaches applied to extremophile communities represent a critical pathway for sustainable discovery of novel enzymes, aligning with United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and offering solutions for global challenges in food security, health, and environmental management.

The discovery of Taq DNA polymerase from the thermophilic bacterium Thermus aquaticus marked a pivotal moment in molecular biology, catalyzing the PCR revolution that transformed genetic research and diagnostic medicine. This whitepaper examines Taq polymerase's legacy as a paradigm for extremophile-derived enzyme utilization and explores the new generation of engineered DNA polymerases emerging from exotic microorganisms. We provide a technical analysis of how protein engineering is expanding polymerase functionality for advanced diagnostic applications, including quantitative multiplex reverse transcription-PCR, allele-specific detection, and next-generation DNA assembly. Within the broader context of extremophile enzyme research, we demonstrate how these biological adaptations continue to drive innovation in molecular diagnostics and therapeutic development.

Extremophiles—organisms thriving in extreme environments—have revolutionized biotechnology by providing enzymes with extraordinary stability and functionality under conditions that denature conventional proteins [4]. The classification of extremophiles includes thermophiles (high temperatures), psychrophiles (freezing temperatures), acidophiles/alkaliphiles (extreme pH), halophiles (high salinity), and piezophiles (high pressure) [4] [36] [10]. These organisms have evolved unique biochemical adaptations, producing specialized enzymes known as extremozymes that maintain activity under harsh conditions [36] [37].

The most successful example of an extremophile-derived enzyme is Taq DNA polymerase from Thermus aquaticus, isolated from Yellowstone National Park's hot springs [4] [10]. Its thermostability (withstanding temperatures up to 95°C) made automated PCR possible, fundamentally advancing molecular biology and diagnostics [38]. This established a paradigm for bioprospecting in extreme environments, which has yielded numerous commercially valuable enzymes with applications across pharmaceuticals, bioremediation, and bioenergy [4] [39].

The Taq Polymerase Legacy: From Basic Research to Molecular Diagnostics

Thermus aquaticus DNA polymerase I represents a foundational enzyme in molecular biology with a well-characterized structure-function relationship. The enzyme comprises three functional domains: an N-terminal 5'-3' exonuclease domain (residues 1-291), a 3'-5' exonuclease domain (residues 292-423), and a C-terminal polymerase domain that catalyzes DNA synthesis [40]. Unlike some bacterial polymerases, Taq lacks key motifs for proofreading activity, which explains its relatively lower fidelity compared to proofreading enzymes [40].

The intrinsic properties of Taq polymerase have driven its widespread adoption in research and diagnostics:

- Thermostability: Withstands repeated heating to 95°C during PCR cycling

- Processivity: Efficiently synthesizes DNA fragments under PCR conditions

- Reverse transcriptase activity: Demonstrated capability to catalyze RNA-to-DNA conversion under specific conditions [38]

- 5' nuclease activity: Enables hydrolysis probe-based detection methods like TaqMan assays [38]

These characteristics made Taq polymerase indispensable for real-time PCR, pathogen detection, genotyping, and gene expression analysis, forming the technical foundation for modern molecular diagnostics.

Engineering the Next Generation: Advanced DNA Polymerase Variants

Engineered Taq Variants with Enhanced Capabilities

Recent protein engineering approaches have substantially expanded Taq polymerase's functionality beyond its wild-type properties. The table below summarizes key engineered Taq variants and their enhanced characteristics:

Table 1: Engineered Taq Polymerase Variants and Their Applications

| Variant Name | Key Mutations | Enhanced Properties | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RT-Taq [38] | L459M, S515R, I638F, M747K | Reverse transcription activity, thermostability up to 95°C | Single-enzyme RT-PCR, multiplex RNA detection |

| TM-Taq [41] | E507K, R536K/L, R660V | Improved mismatch discrimination | Allele-specific PCR, ultra-sensitive mutation detection |

| Mut_RT [38] | N483K, E507K, K540Y, V586G, I614K | Enhanced reverse transcription efficiency | One-tube RT-PCR, molecular diagnostics |

These engineered variants address specific limitations of wild-type Taq polymerase. For instance, RT-Taq variants combine reverse transcription and DNA amplification capabilities in a single enzyme, eliminating the need for separate viral reverse transcriptases in RT-PCR applications [38]. The TM-Taq (triple mutant) variant exhibits significantly improved allele discrimination, enabling detection of mutant alleles with frequencies as low as 0.0001% in plasmid DNA and 0.01% in genomic DNA, crucial for cancer mutation detection and liquid biopsy applications [41].

Novel Polymerases from Diverse Extremophiles

Beyond Taq engineering, researchers are exploring DNA polymerases from other extremophiles with unique properties:

Table 2: Novel Extremophile-Derived DNA Polymerases

| Polymerase | Source Organism | Extremophile Type | Unique Properties | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neq2X7 [42] | Nanoarchaeum equitans | Hyperthermophile | High processivity, dUTP tolerance, fusion with Sso7d DNA-binding domain | USER cloning, long-range PCR, inhibitor-resistant diagnostics |

| PfuX7 [42] | Pyrococcus furiosus | Hyperthermophile | Proofreading (3'-5' exonuclease) activity, engineered uracil binding pocket | High-fidelity PCR, DNA assembly |

| L-asparaginase [5] | Bacillus subtilis CH11 | Halotolerant | Thermal stability (optimal at pH 9.0 and 60°C), 4-hour half-life at 60°C | Cancer therapy, food processing |

The Neq2X7 polymerase exemplifies how fusion strategies can enhance enzyme performance. By incorporating the Sso7d DNA-binding domain from Sulfolobus solfataricus, researchers created a polymerase with significantly increased processivity capable of amplifying long, GC-rich templates and functioning in the presence of PCR inhibitors [42]. This polymerase shows an eight-fold increase in activity compared to its non-fusion counterpart and can perform PCR with dramatically reduced extension times (15 seconds/kb versus 1 minute/kb for conventional polymerases) [42].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Polymerase Engineering and Validation

Protein Engineering via Site-Directed Mutagenesis

The development of novel polymerase variants typically employs overlap extension PCR for site-directed mutagenesis [41]. The standard protocol involves:

- Primer Design: Create mutagenic primers containing desired nucleotide changes, flanked by 15-20 base pairs of homologous sequence

- Primary PCR: Generate overlapping DNA fragments using mutagenic primers and flanking primers

- Fragment Purification: Clean amplified products using gel electrophoresis or PCR purification kits

- Fusion PCR: Combine fragments in a second PCR reaction with external primers to generate full-length products

- Cloning: Insert amplified products into expression vectors (e.g., pET-28a(+) for E. coli expression)

- Sequence Verification: Confirm incorporation of desired mutations via Sanger sequencing [41]

For combinatorial library generation, as described for RT-active Taq variants, all possible mutation combinations are synthesized in equimolar amounts, cloned en masse, and transformed into expression hosts with oversampling (≥10× library size) to ensure >99% variant coverage [38].

High-Throughput Screening for RT-PCR Activity

Screening for reverse transcription-PCR activity employs:

- Cell Lysate Preparation: Direct use of heat-treated E. coli expression culture lysates

- Real-Time RT-PCR Assay: Implementation using previously established methods for SARS-CoV-2 RNA detection

- Activity Metrics: Evaluation based on amplification efficiency, Ct values, and endpoint fluorescence using intercalating dyes (SYBR Green I) or hydrolysis probes (TaqMan chemistry) [38]

Fidelity Assessment via Nucleotide Imbalance Assay

Polymerase error rates are quantified using:

- Magnification via Nucleotide Imbalance: Estimation of error rates through biased dNTP pools

- Sequence Verification: Comparison of amplified product sequences to original templates

- Calculation: Error rates expressed as mutations per base pair per duplication (e.g., Neq2X7: <2×10⁻⁵ bp⁻¹) [42]

Technical Workflow: Engineering DNA Polymerases

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for engineering and validating novel DNA polymerase variants:

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Materials for Polymerase Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for DNA Polymerase Engineering and Application

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Expression Vectors | pET-28a(+), pGDR11 | Heterologous protein expression in E. coli |

| Host Strains | E. coli BL21(DE3), Rosetta2(DE3) | Recombinant protein production |

| Detection Chemistries | SYBR Green I, TaqMan probes (FAM/BHQ1) | Real-time monitoring of amplification |

| Selection Markers | Kanamycin, ampicillin resistance | Selective growth of transformants |

| Purification Systems | 6xHis-tag, nickel-NTA chromatography | Protein purification |

| Mutagenesis Kits | Overlap extension PCR reagents | Site-directed mutagenesis |

| Activity Assays | Fluorescence-based polymerase assays | Enzyme kinetics and characterization |

Current Applications and Future Perspectives in Molecular Diagnostics

Engineered DNA polymerases are revolutionizing molecular diagnostics through:

Advanced Diagnostic Applications

- Quantitative Multiplex RT-PCR: Novel Taq variants enable simultaneous detection of up to four RNA targets in a single reaction with a detection limit of 20 copies, eliminating need for separate reverse transcriptase enzymes [38]

- Ultra-Sensitive Mutation Detection: TM-Taq polymerase achieves detection of mutant allele frequencies as low as 0.01% in genomic DNA, enabling non-invasive cancer detection via liquid biopsy [41]

- Rapid Pathogen Detection: High-processivity enzymes like Neq2X7 reduce PCR extension times to 15 seconds/kb, enabling development of rapid diagnostics (<30 minute protocols) [42]

Integration with Emerging Technologies

The unique properties of engineered extremophile-derived polymerases facilitate their integration with cutting-edge diagnostic platforms:

- Point-of-Care Diagnostics: Thermostable enzymes maintain functionality under field conditions without cold chain requirements

- Next-Generation Sequencing: Specialized polymerases enable novel sequencing chemistries and improved read lengths

- CRISPR-Based Detection: Polymerases with enhanced reverse transcriptase activity improve RNA target conversion for CRISPR diagnostic systems

Future developments will likely focus on engineering polymerases with expanded substrate specificity for direct incorporation of modified nucleotides, enhanced resistance to clinical sample inhibitors, and programmable specificities for targeted amplification. The continued exploration of extreme environments will undoubtedly yield new polymerase scaffolds with novel properties, further advancing diagnostic capabilities.

The legacy of Taq polymerase extends far beyond its revolutionary impact on PCR technology. It established extremophiles as invaluable resources for biotechnology and demonstrated the power of protein engineering to enhance natural enzyme capabilities. The current generation of engineered DNA polymerases—with capabilities ranging from sophisticated multiplex pathogen detection to ultra-sensitive mutation identification—represents the maturation of this approach. As extremophile research continues to uncover novel biological adaptations, and protein engineering methodologies become increasingly sophisticated, the next revolution in molecular diagnostics will undoubtedly build upon this foundation of harnessing and enhancing nature's most resilient enzymes.