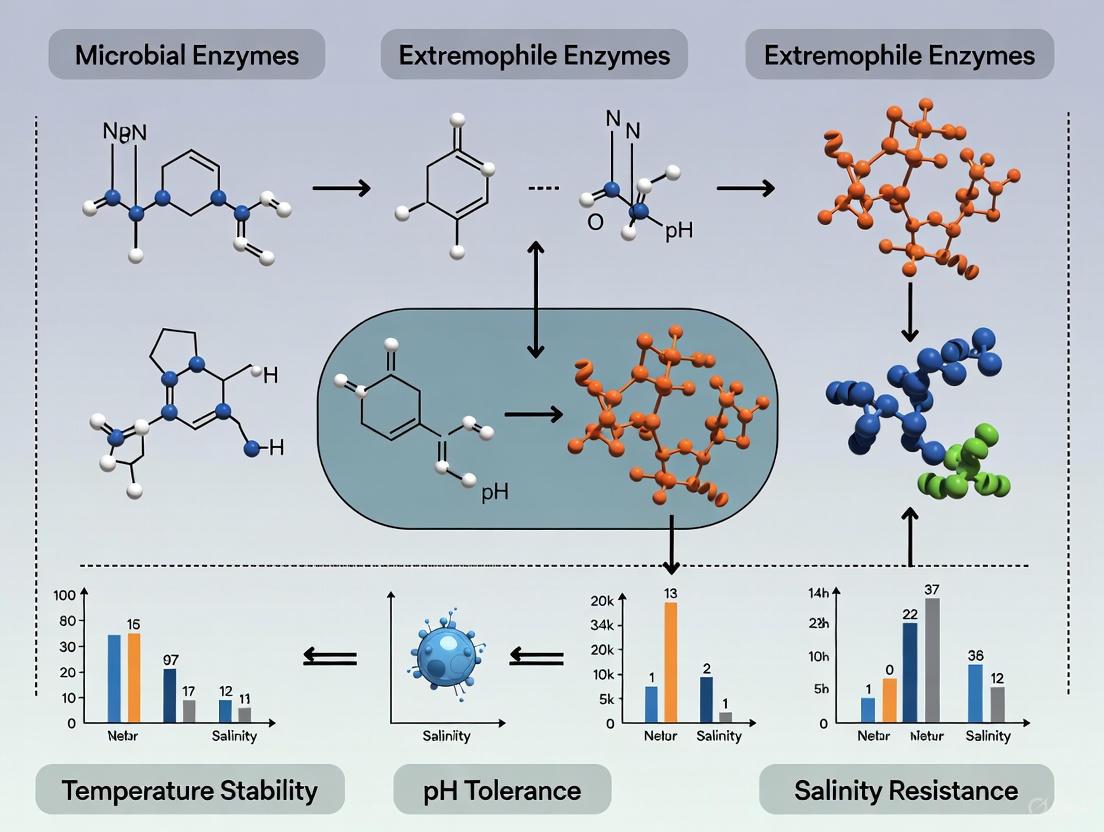

Extremozymes vs. Conventional Microbial Enzymes: A Comparative Analysis of Stability for Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the structural stability and functional resilience of extremophile-derived enzymes (extremozymes) against their conventional microbial counterparts.

Extremozymes vs. Conventional Microbial Enzymes: A Comparative Analysis of Stability for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of the structural stability and functional resilience of extremophile-derived enzymes (extremozymes) against their conventional microbial counterparts. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational biochemical adaptations, details advanced methodologies for discovery and production, addresses key challenges in bioprocessing, and validates performance through direct comparative studies. The synthesis underscores the immense potential of extremozymes to overcome limitations in industrial biocatalysis and pharmaceutical manufacturing, offering robust, efficient, and sustainable solutions for demanding processes.

Defining Stability: Structural and Functional Adaptations in Microbial and Extremophile Enzymes

Enzyme stability is a fundamental property determining the efficacy, shelf-life, and economic viability of biocatalysts in industrial and pharmaceutical processes. It refers to an enzyme's ability to maintain its structural integrity and catalytic function under a variety of challenging conditions, including extreme temperatures, pH fluctuations, organic solvents, and mechanical shear [1]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and enhancing enzyme stability is paramount for developing efficient bioprocesses and therapeutic enzymes.

The study of enzyme stability has been profoundly advanced by investigating organisms that thrive in extreme environments, known as extremophiles. These organisms have evolved unique molecular adaptations that allow their enzymes, termed extremozymes, to function under conditions that would denature most proteins [2] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of stability mechanisms between traditional microbial enzymes and extremozymes, offering a structured framework for selecting and engineering biocatalysts tailored to specific application needs.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Enzyme Stability

The stability of an enzyme is governed by a network of intramolecular interactions and structural features that maintain its native, catalytically active conformation. These mechanisms differ significantly between enzymes derived from mesophilic microorganisms and those from extremophiles.

Molecular Determinants of Stability

- Hydrophobic Interactions: In thermophiles, increased hydrophobic core packing reduces water accessibility and enhances thermostability. In contrast, psychrophiles exhibit weaker hydrophobicity to maintain flexibility at low temperatures [2].

- Hydrogen Bonding & Salt Bridges: Thermophilic enzymes contain a higher number of charged residues (Glu, Arg, Lys) that form intricate networks of salt bridges and hydrogen bonds, stabilizing the protein structure at high temperatures [2] [4]. Psychrophilic enzymes minimize these interactions to reduce rigidity [2].

- Amino Acid Composition: Biases in amino acid usage significantly influence stability. Thermophiles show preferences for aromatic and charged residues, while psychrophiles increase glycine content to enhance backbone flexibility [2].

- Structural Compactness: Thermophilic proteins often feature shorter surface loops, reduced surface-to-volume ratios, and increased secondary structure stabilization [2]. Piezophiles (pressure-adapted) incorporate larger volume cavities in their structures to accommodate compression [4].

Membrane and Cofactor Adaptations

Beyond the protein itself, stability is influenced by cellular components. Thermophiles utilize ether-linked lipids in their membranes for enhanced heat resistance, while psychrophiles increase unsaturated fatty acids to maintain membrane fluidity in cold environments [2] [3]. Some alkaliphiles employ specialized cytochrome c and surface proteins to maintain proton homeostasis crucial for function at high pH [4].

Comparative Analysis: Microbial vs. Extremophile Enzymes

The table below summarizes key stability characteristics and molecular adaptations of enzymes from different biological sources.

Table 1: Comparative Stability Profiles of Microbial and Extremophile Enzymes

| Enzyme Source | Optimal Temp Range | Structural Features | Molecular Adaptations | Industrial Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychrophiles (Cold-adapted) | <15-20°C [4] | Heat-labile, flexible active sites, less compact structures [2] | Weaker hydrophobicity, fewer salt bridges/H-bonds, more glycine, unsaturated membrane lipids [2] [3] | Food processing, environmental bioremediation, biotechnology [3] |

| Mesophiles (Traditional microbes) | 20-45°C [2] | Moderate structural rigidity, standard active site accessibility | Standard amino acid composition, typical H-bond/salt bridge density | Detergents, baking, brewing, dairy processing [5] |

| Thermophiles (Heat-adapted) | 60->80°C [4] | Compact structures, shortened loops, increased secondary structure [2] | Enhanced hydrophobic packing, additional salt bridges/H-bonds, charged/aromatic residues, ether-linked lipids [2] [4] | PCR (Taq polymerase), starch processing, biofuel production [2] [6] |

| Halophiles (Salt-adapted) | Varies | Highly acidic, negatively charged surfaces [1] | Enriched surface acidic residues (Asp, Glu), solute accumulation for osmotic balance [1] | Biocatalysis in organic media, biosensors, cosmetic formulations [6] [1] |

| Piezophiles (Pressure-adapted) | Varies | Larger volume cavities, pressure-resistant folding [4] | Polar/ hydrophilic amino acid substitutions, specialized chaperones [4] | High-pressure bioreactors, deep-sea biotechnology [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Enzyme Stability

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for quantitatively comparing enzyme stability across different conditions and enzyme types. Below are key methodologies cited in current research.

Thermostability Assessment

Melting Temperature (Tₘ) Determination

- Objective: To determine the temperature at which 50% of the enzyme population becomes unfolded [7].

- Protocol:

- Prepare purified enzyme solution in appropriate buffer.

- Use differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) or fluorimetry-based thermal shift assays.

- Apply a controlled temperature ramp (e.g., 1°C per minute) while monitoring unfolding.

- Plot the unfolding curve and calculate Tₘ as the inflection point.

- Data Interpretation: Higher Tₘ values indicate greater intrinsic thermostability. The magnitude of thermal shift (ΔTₘ) upon substrate binding can reveal stabilization effects, with smaller enzymes often showing more substantial ΔTₘ [7].

Thermal Inactivation Half-Life

- Objective: To measure the time-dependent loss of activity at a specific temperature.

- Protocol:

- Incubate enzyme samples at constant elevated temperature.

- Withdraw aliquots at regular time intervals and measure residual activity under standard assay conditions.

- Plot log(residual activity) versus time.

- Calculate half-life (t₁/₂) from the inactivation rate constant.

- Data Interpretation: Longer half-lives indicate superior operational stability for industrial processes requiring prolonged catalysis [1].

Stability Under Other Stress Conditions

pH Stability Profile

- Protocol: Incubate enzymes in buffers of varying pH for a fixed duration, then measure residual activity at optimal pH [1].

- Output: pH range retaining >80% activity indicates functional pH breadth.

Solvent Tolerance

- Protocol: Incubate enzymes with various organic solvents (e.g., dimethylformamide, methanol) and measure residual activity after exposure [1].

- Output: Higher residual activity indicates suitability for non-aqueous biocatalysis.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a comprehensive enzyme stability assessment, integrating the protocols described above.

Diagram 1: Enzyme Stability Assessment Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful research into enzyme stability requires specific reagents and tools. The following table details essential solutions and their functions in stability experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Stability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Stability Assessment | Example Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable Markers (e.g., Taq Polymerase) | Positive controls for high-temperature stability assays; benchmark for engineering efforts [6]. | Validating thermal cycler performance, comparing thermostability of novel isolates. |

| Buffering Systems (e.g., phosphate, Tris, citrate buffers across pH range) | Maintain specific pH conditions during stability challenges; determine pH activity/stability profiles [1]. | Assessing enzyme functionality in acidic (e.g., food) or alkaline (e.g., detergent) processes. |

| Chaotropic Agents (e.g., Urea, Guanidine HCl) | Induce controlled protein unfolding; measure conformational stability via denaturation curves [1]. | Determining the free energy of unfolding (ΔG) and comparing structural rigidity. |

| Organic Solvents (e.g., DMSO, methanol, hexane) | Assess stability and activity in non-aqueous environments relevant to industrial synthesis [1]. | Screening enzymes for biocatalysis in organic media for pharmaceutical intermediate synthesis. |

| Protease Inhibitors (e.g., PMSF, EDTA) | Protect enzymes from proteolytic degradation during purification and storage, preventing misleading stability data [7]. | Maintaining enzyme integrity in crude extracts or during long-term stability studies. |

| Immobilization Supports (e.g., chitosan, silica, epoxy-activated resins) | Enhance operational stability by rigidifying enzyme structure and enabling reuse [1]. | Developing reusable biocatalysts for continuous flow reactors in API manufacturing. |

| Spectrophotometric Assay Kits (e.g., based on pNA, CDNB, or other chromogenic substrates) | Enable rapid, high-throughput measurement of residual enzyme activity after stability challenges [1]. | Screening large libraries of enzyme variants for improved stability in directed evolution campaigns. |

Emerging Strategies for Enhancing Enzyme Stability

Enzyme Engineering and Miniaturization

Rational design and directed evolution represent powerful approaches for improving enzyme stability. Rational design focuses on introducing specific mutations to enhance stabilizing interactions, such as adding salt bridges, disulfide bonds, or optimizing surface charge [1]. Directed evolution mimics natural selection in the laboratory by generating diverse mutant libraries and screening for variants with enhanced stability under desired conditions [1].

A promising strategy is enzyme miniaturization, which involves creating smaller, catalytically active versions of enzymes. Smaller enzymes often demonstrate superior expression yields, faster folding kinetics, reduced misfolding propensity, and potentially enhanced thermostability due to the removal of flexible, non-essential loops that can initiate unfolding [7].

Bioinformatics and AI-Driven Discovery

Advanced computational methods are revolutionizing stability prediction and engineering. Machine learning models trained on protein sequences and structures can now predict mutation effects on stability and function [1]. Tools like EZSpecificity use graph neural networks to accurately predict enzyme-substrate interactions, aiding in the design of enzymes with tailored stability and specificity [8]. Furthermore, metagenomic mining of unculturable extremophiles directly from environmental DNA provides access to a vast reservoir of novel, stable enzymes without the need for laboratory cultivation [3] [6].

Enzyme stability is a multifaceted property dictated by complex molecular interactions. The comparative analysis presented in this guide underscores that extremophile enzymes offer unparalleled stability under extreme conditions, providing valuable blueprints for engineering more robust biocatalysts. However, traditional microbial enzymes remain indispensable for applications under moderate conditions due to their catalytic efficiency and ease of production.

Future advancements will increasingly rely on integrating structural biology insights with AI-driven tools and high-throughput experimental validation. This multidisciplinary approach will accelerate the development of next-generation enzymes with tailor-made stability properties, ultimately driving innovation across industrial and pharmaceutical sectors.

Microbial enzymes are fundamental biocatalysts that accelerate biochemical reactions across numerous industries, including pharmaceuticals, food processing, detergents, and biofuel production [9]. Their commercial success hinges on stability and functional integrity under process-specific conditions. Conventional microbial enzymes, typically sourced from mesophilic microorganisms (growing at 20–45°C), exhibit optimal performance within narrow ranges of temperature, pH, and solvent concentration [10]. Beyond these ranges, they face significant stability challenges that can limit their industrial efficacy.

The growing demand for sustainable bioprocesses has intensified the need for robust enzymes, shifting research focus toward understanding and enhancing the stability profiles of conventional microbial enzymes under stressful industrial conditions [9]. This review systematically compares the stability and limitations of these enzymes, providing a structured analysis of experimental data, stabilization methodologies, and strategic recommendations for industry applications.

Defining Stability and Stress Conditions for Microbial Enzymes

Enzyme stability refers to an enzyme's ability to resist denaturation and maintain its catalytic function when exposed to various deterrents such as extreme pH, organic solvents, high salt concentrations, and thermal stress [11]. Denaturation involves the loss of the enzyme's native secondary, tertiary, or quaternary structure through the application of external stressors, leading to inactivation [11].

For conventional microbial enzymes, common industrial stress conditions include:

- Temperature Stress: Exposure to temperatures significantly higher than their optimal range (typically above 45-50°C) can cause unfolding and aggregation [10].

- pH Stress: Operating in highly acidic (pH < 5) or alkaline (pH > 9) environments can alter charged amino acid residues, disrupting the active site and protein structure [9].

- Chemical Stress: Contact with organic solvents, heavy metals, or denaturing agents can interfere with hydrophobic interactions and hydrogen bonding [12].

- Oxidative Stress: Presence of oxidizing agents can damage susceptible amino acids like cysteine and methionine [13].

Comparative Stability Profiles: Quantitative Analysis

The following tables summarize typical stability profiles of conventional microbial enzymes under various stress conditions, based on experimental data.

Table 1: Thermal Inactivation Parameters of Conventional Microbial Enzymes

| Enzyme Class | Microbial Source | Optimal Temp (°C) | Half-life at 50°C | Inactivation Temp (°C) | Key Stabilizing Factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease | Bacillus licheniformis | 50-60 | ~30 min | ~65 | Ca²⁺ ions, high substrate concentration |

| Lipase | Pseudomonas alcaligenes | 37-45 | < 60 min | ~55 | Interfacial activation, lid structure |

| α-Amylase | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens | 70 | ~15 min | ~80 | Ca²⁺ ions, chloride ions |

| Cellulase | Trichoderma reesei | 40-50 | ~20 min | ~60 | Glycosylation, substrate binding |

Table 2: Stability of Conventional Enzymes Under pH and Solvent Stress

| Enzyme Class | Optimal pH Range | Activity Retention at pH 5 (%) | Activity Retention at pH 9 (%) | Activity in 20% Organic Solvent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protease (Neutral) | 6.5-7.5 | < 30 | < 40 | < 50 |

| Lipase | 7.0-9.0 | < 20 | > 80 | > 70 |

| α-Amylase | 5.5-6.5 | > 70 | < 25 | < 40 |

| Laccase (Fungal) | 4.0-5.0 | > 80 | < 20 | < 35 |

Molecular Mechanisms of Instability and Denaturation

The stability limitations of conventional microbial enzymes stem from their structural sensitivity to environmental extremes. Under thermal stress, the kinetic energy overwhelms the weak forces—hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces—that maintain the protein's tertiary structure [10]. This leads to unfolding, exposure of hydrophobic regions, and often irreversible aggregation.

Under pH stress, alterations in the ionization state of amino acid side chains disrupt salt bridges and electrostatic networks essential for structural integrity. For instance, acidophiles maintain stability at low pH through a high content of acidic residues on their surface, while conventional enzymes lack such adaptations [14]. In organic solvents, the desolvation of the enzyme molecule and disruption of essential water layers lead to significant rigidity loss and decreased catalytic efficiency [11].

Diagram: Structural Denaturation Pathways of Conventional Enzymes Under Stress

Methodologies for Assessing Enzyme Stability

Experimental Protocols for Stability Characterization

Standardized experimental protocols are essential for generating comparable stability data. The following methodologies are widely employed:

Thermal Stability Assay:

- Prepare enzyme solution in appropriate buffer at optimal pH.

- Aliquot samples into thin-walled PCR tubes.

- Incubate samples at target temperatures (e.g., 40°C, 50°C, 60°C, 70°C) in thermal cyclers or water baths.

- Withdraw aliquots at predetermined time intervals (0, 5, 15, 30, 60 minutes).

- Immediately cool samples on ice and measure residual activity using standard assays.

- Calculate half-life (t₁/₂) and deactivation rate constants from activity decay curves [9].

pH Stability Profile:

- Prepare buffer systems covering pH range 3.0-10.0.

- Incubate enzyme in each buffer for fixed duration (typically 1 hour) at 25°C.

- Measure residual activity under standard conditions.

- Determine optimal pH and stability range from activity profile [11].

Solvent Tolerance Assay:

- Prepare enzyme solutions containing 10-30% (v/v) organic solvents (e.g., methanol, acetonitrile, DMSO).

- Incubate with shaking for 4-24 hours at 25°C.

- Measure residual activity compared to solvent-free control.

- Assess structural integrity via circular dichroism or fluorescence spectroscopy [15].

Diagram: Workflow for Comprehensive Enzyme Stability Assessment

Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Enzyme Stability Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Stability Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Buffer Systems | phosphate, Tris-HCl, citrate, glycine | Maintain specific pH during stress tests |

| Thermal Stabilizers | glycerol, sorbitol, Ca²⁺ ions | Protect against thermal denaturation |

| Solvent Additives | polyols, sugars, proline | Counteract solvent-induced denaturation |

| Activity Assay Reagents | chromogenic substrates (pNPP, casein), DNS | Quantify residual enzymatic activity |

| Structural Probes | ANS, Sypro Orange | Detect unfolding and hydrophobic exposure |

| Immobilization Carriers | chitosan, silica nanoparticles, Eupergit C | Provide stabilization via rigid support |

Strategies for Enhancing Enzyme Stability

Immobilization Techniques

Immobilization represents a primary physical method for stabilizing conventional enzymes by restricting their mobility through binding to a solid substrate [11]. This approach significantly enhances resistance to temperature, pH, solvents, and impurities while enabling enzyme reusability and simplified separation from reaction mixtures [11].

The five principal immobilization techniques include:

- Adsorption: Reversible binding via weak forces (salt linkage, hydrogen bonds, ionic bonds) to supports like silica, chitosan, or cellulose [11].

- Covalent Binding: Formation of stable covalent bonds between enzyme functional groups and activated carriers like agarose or Eupergit C [11].

- Encapsulation: Entrapment within polymer matrices or microcapsules [11].

- Cross-linking: Creating intermolecular bonds between enzyme molecules using linkers like glutaraldehyde [11].

- Entrapment: Physical confinement in polymeric networks [11].

Chemical Modification and Engineering Approaches

Protein engineering strategies have demonstrated remarkable success in enhancing enzyme stability:

- Rational Design: Site-directed mutagenesis to target specific amino acid substitutions that enhance stability, requiring detailed 3D structural information [9].

- Directed Evolution: Iterative rounds of random mutagenesis and screening to select variants with improved stability under stress conditions [9].

- Chemical Modification: Covalent attachment of stabilizing polymers (e.g., polyethylene glycol) or carbohydrates to enzyme surfaces [11].

- Additive Incorporation: Use of co-solvents, osmolytes, and compatible solutes to stabilize enzymes in suboptimal environments [15].

The stability profiles of conventional microbial enzymes reveal significant limitations under industrial stress conditions, particularly when compared to extremozymes from thermophiles, psychrophiles, and halophiles [14]. While conventional enzymes typically exhibit half-lives of minutes at elevated temperatures and significant activity loss under pH or solvent stress, extremozymes can maintain functionality for hours or days under similar conditions [14].

This stability gap underscores the importance of strategic enzyme selection based on process requirements. For applications involving moderate conditions, conventional enzymes remain cost-effective solutions. However, for processes requiring extreme temperatures, pH, or solvent tolerance, extremozymes or engineered variants offer superior performance despite potentially higher initial costs [9] [14].

Future research directions should focus on integrating multi-omics approaches with advanced protein engineering to develop next-generation enzymes that combine the catalytic efficiency of conventional enzymes with the robustness of extremozymes [14]. Such advances will significantly expand the application scope of microbial enzymes in sustainable industrial processes.

Extremophiles are organisms that thrive in ecological niches characterized by conditions once considered incompatible with life, redefining our understanding of life's resilience and adaptability [16] [6]. These remarkable organisms inhabit environments with extreme temperatures, pH levels, salinity, pressure, and radiation, utilizing unique biochemical adaptations to not only survive but flourish where conventional life would perish [6] [17]. The study of extremophiles has gained significant scientific interest since the discovery of Thermus aquaticus from Yellowstone National Park's hot springs in the 1960s, fundamentally reshaping our perspective on life's boundaries and evolutionary origins [18] [17].

From a comparative enzymology perspective, extremophiles represent a fascinating subject for investigating protein stability and function under physical-chemical extremes. Their enzymes, known as extremozymes, exhibit exceptional stability and catalytic efficiency under conditions that would rapidly denature or inactivate their conventional counterparts from mesophilic organisms [16] [14]. This review systematically compares the adaptive strategies and enzymatic machinery of extremophiles across niche types, with particular emphasis on experimental approaches for quantifying stability parameters that inform both fundamental biology and biotechnological applications in drug development and industrial processes.

Comparative Analysis of Extremophile Niches and Adaptive Strategies

Extremophiles are classified based on the specific environmental parameters of their ecological niches. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of major extremophile categories, their niche characteristics, and corresponding adaptive mechanisms at cellular and molecular levels.

Table 1: Extremophile Classification, Niche Characteristics, and Adaptive Strategies

| Extremophile Type | Niche Characteristics | Representative Species | Key Adaptive Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermophiles | Temperatures exceeding 40°C up to 122°C [16] [18] | Methanopyrus kandleri (122°C) [18] | Thermostable enzymes with reinforced salt bridges, hydrophobic interactions, hydrogen bonding [17] |

| Psychrophiles | Temperatures below -17°C [16] | Psychromonas ingrahamii (-12°C) [18] | Cold-adapted enzymes with structural flexibility; antifreeze proteins [16] [17] |

| Acidophiles | pH below 5 [16] | Picrophilus oshimae (pH 0) [18] | Reinforced membrane composition; proton export machinery [18] |

| Alkaliphiles | pH above 9 [16] | Bacillus alkaliphilus (pH 9.5-10.5) [18] | Specialized membrane transporters; cytoplasmic acidification mechanisms |

| Halophiles | Salt concentrations >3.5% [16] | Halorhodospira halophila (13% NaCl) [18] | Compatible solute synthesis; ion homeostasis; specialized membrane composition [17] |

| Piezophiles | High-pressure environments [16] | Moritella yayanosii (100 MPa) [18] | Piezolyte production; membrane fluidity modulation via unsaturated fatty acids [17] |

| Radiophiles | Radiation levels exceeding natural background [16] | Deinococcus radiodurans [6] | Efficient DNA repair mechanisms; oxidative damage protection proteins [6] [17] |

Many extremophiles are polyextremophiles, adapted to multiple simultaneous stresses [14] [17]. For example, Saccharolobus solfataricus (formerly Sulfolobus solfataricus) thrives at 80°C and pH 2.0-4.0, requiring adaptations for both high temperature and extreme acidity [18]. These complex niche requirements drive the evolution of sophisticated, integrated adaptation mechanisms that confer stability across several physicochemical parameters simultaneously.

Experimental Methodologies for Assessing Enzyme Stability

The comparative analysis of enzyme stability between conventional microbial enzymes and extremozymes requires specialized experimental protocols designed to measure functional integrity under extreme conditions. Below are detailed methodologies for key stability assays cited in extremophile enzyme research.

Thermal Stability Profiling

Objective: Quantify enzyme thermostability by measuring residual activity after exposure to elevated temperatures. Protocol:

- Prepare enzyme solution in appropriate buffer at pH optimum

- Aliquot samples into thin-walled PCR tubes

- Perform heat challenge in thermal cycler: incubate at temperature range from 50°C to 100°C for time intervals (15-120 minutes)

- Immediately cool samples on ice for 10 minutes

- Measure residual enzymatic activity using standard assay conditions

- Calculate half-life (t½) at each temperature from activity decay curves Applications: Particularly essential for characterizing thermozymes from organisms like Pyrococcus furiosus (optimal growth at 100°C) [18] and comparing them to mesophilic counterparts.

pH Tolerance Assessment

Objective: Determine enzymatic activity and stability across pH spectrum. Protocol:

- Prepare buffer systems covering pH range 1.0-12.0 (e.g., glycine-HCl, citrate, phosphate, Tris, glycine-NaOH)

- Incubate enzyme in each buffer for 1 hour at 4°C

- Measure initial activity under respective pH conditions

- For stability assessment, return aliquots to optimal pH and measure recovered activity

- Plot activity vs. pH to determine optimal range and stability profile Applications: Critical for characterizing acidophiles (e.g., Picrophilus oshimae, pH 0) and alkaliphiles (e.g., Bacillus alkaliphilus, pH 10.5) [18].

Halostability Measurement

Objective: Quantify enzyme function and stability at high salt concentrations. Protocol:

- Prepare reaction mixtures with NaCl concentrations ranging from 0-5 M

- Measure enzyme activity at each salt concentration

- For stability assessment, pre-incubate enzyme in different NaCl concentrations for 24 hours

- Measure residual activity under optimal assay conditions

- Compare kinetics parameters (Km, Vmax) at various salt concentrations Applications: Essential for studying halophiles like Halorhodospira halophila which thrives at 13% NaCl [18].

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for systematic characterization of extremophile enzyme stability:

Quantitative Comparison of Enzyme Stability Parameters

The exceptional utility of extremozymes in biotechnology and industrial processes stems from their quantified stability advantages over conventional enzymes. The table below summarizes comparative experimental data highlighting these differences across stability parameters.

Table 2: Comparative Stability Parameters of Microbial vs. Extremophile Enzymes

| Enzyme Type | Source Organism | Optimal Activity Temperature | Thermal Half-life (at 90°C) | pH Stability Range | Salt Tolerance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Protease | Bacillus subtilis (mesophile) | 37-45°C | <5 minutes | 5.5-8.5 | Low (<0.5 M NaCl) |

| Thermostable Protease | Thermus aquaticus | 70-80°C | >60 minutes [17] | 6.0-9.0 | Moderate (1-2 M NaCl) |

| Thermostable Polymerase | Pyrococcus furiosus | 100°C [18] | >4 hours [18] | 6.5-8.0 | Low-Moderate |

| Cold-adapted Lipase | Psychromonas ingrahamii | 4-15°C [18] | N/A (thermolabile) | 7.0-9.0 | High (2-3 M NaCl) [14] |

| Halotolerant Esterase | Halorhodospira halophila | 37-45°C | <30 minutes | 7.5-10.5 | Extreme (4-5 M NaCl) [18] |

| Acidophilic Amylase | Saccharolobus solfataricus | 80°C [18] | >90 minutes | 2.0-4.0 [18] | Low (<0.5 M NaCl) |

Structural analysis reveals the molecular basis for these stability differences. Thermozymes exhibit strengthened hydrophobic cores, increased salt bridge networks, and enhanced hydrogen bonding compared to their mesophilic counterparts [17]. Psychrophilic enzymes achieve cold activity through reduced proline/arginine content, fewer salt bridges, and increased surface hydrophilicity that provides structural flexibility at low temperatures [14]. Halophilic enzymes display high surface acidity with abundant aspartic and glutamic acid residues that coordinate hydrated salt ions, maintaining solvation and function at near-saturating salt concentrations [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Research into extremophile enzymes requires specialized reagents and materials designed to maintain enzyme integrity and facilitate activity measurements under extreme conditions. The following table details key solutions and their applications in extremophile enzymology.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Extremophile Enzyme Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Thermostable Enzyme Substrates (e.g., p-nitroaniline-linked peptides) | Colorimetric activity detection at high temperatures | Measuring protease activity in thermophiles like Pyrococcus furiosus at 100°C [18] |

| Specialized Buffer Systems (e.g., HEPES, MES, CHES) | Maintain precise pH under extreme conditions | pH stability profiling across range 1.0-12.0 for acidophiles/alkaliphiles |

| Osmoprotectants (e.g., betaine, trehalose) | Stabilize enzymes during freezing/thawing | Preserving activity in psychrophilic enzyme preparations |

| Halostability Buffers (with 0-5 M NaCl/KCl) | Maintain ionic strength for halophile function | Characterizing salt-dependent activity in halophiles like Halorhodospira halophila [18] |

| Chaotrope Resistance Agents (e.g., sorbitol, glycerol) | Protect against chemical denaturants | Assessing enzyme stability in industrial process conditions |

| Piezophilic Culture Chambers | Maintain high-pressure conditions | Studying enzymes from piezophiles like Moritella yayanosii (100 MPa) [18] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between extremophile niches, their enzyme adaptations, and resulting biotechnological applications:

The systematic comparison of extremophiles and their enzymes reveals a remarkable continuum of biological adaptation to environmental extremes. From thermal springs approaching 122°C to hypersaline lakes and acidic geothermal fields, these organisms have evolved enzymatic machinery with precisely calibrated stability parameters that enable life at the physical-chemical limits. The quantitative data and experimental methodologies presented herein provide researchers with standardized approaches for comparative enzymology in extreme conditions.

For drug development professionals, extremozymes offer more than just process advantages; they represent sources of novel catalytic mechanisms and structural scaffolds with potential therapeutic applications. The continued exploration of Earth's most challenging environments through metagenomic and single-cell genomic approaches promises to reveal even more extraordinary enzymatic diversity with applications spanning medicine, biotechnology, and industrial catalysis [6] [18]. As climate change alters global ecosystems, understanding these limits of life becomes increasingly crucial for developing resilient biotechnological solutions in a rapidly changing world.

The study of extremophiles—organisms that thrive in conditions once deemed incompatible with life—has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of protein stability and function. Among these remarkable organisms, thermophiles and psychrophiles represent two evolutionary extremes, inhabiting environments characterized by persistently high or low temperatures, respectively. Their enzymes, known as extremozymes, have undergone specialized adaptations to maintain activity and structural integrity under these challenging conditions. For thermophiles, the imperative is to resist denaturation and unfolding at high temperatures, achieved through enhanced structural rigidity. In contrast, psychrophiles face the opposite challenge: maintaining catalytic flexibility and dynamics at temperatures that would typically render mesophilic proteins inert. This guide provides a detailed, evidence-based comparison of the molecular strategies employed by these extremophiles, framing the discussion within broader research on comparative enzyme stability and providing actionable experimental data and protocols for researchers in biotechnology and drug development.

Structural & Molecular Basis of Adaptation

The distinct thermal challenges faced by thermophiles and psychrophiles have driven the evolution of unique structural solutions at the molecular level. The table below summarizes the key adaptive traits observed in proteins from these organisms.

Table 1: Molecular Adaptations in Thermophilic and Psychrophilic Proteins

| Adaptive Trait | Thermophilic Proteins | Psychrophilic Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Amino Acid Propensity | Increased Arg, Tyr; Decreased Cys, Ser [19] [20] | More small residues (e.g., Gly); Reduced bulky hydrophobic cores [21] |

| Secondary Structure | Higher fraction of residues in α-helices; Avoids Pro in helices [19] | Reduced helical content; Longer surface loops [21] |

| Stabilizing Interactions | Increased salt bridges & side-chain H-bonds; Dense ionic networks [22] [19] | Fewer salt bridges & H-bonds; Weakened intramolecular interactions [21] |

| Hydrophobic Core | Increased packing density; More aromatic clusters [22] [21] | Reduced packing density; Fewer aromatic clusters [21] |

| Overall Structural Rigidity | High; reinforced by networks of charges [22] | Low; maintains flexibility at low temperatures [23] [21] |

These molecular differences are not random but form a coherent adaptive strategy. Thermophilic proteins enhance rigidity through a multi-faceted approach: charged residues like arginine and glutamate form intricate networks of salt bridges that cross-link different structural elements, while a compact hydrophobic core and more extensive hydrogen bonding provide internal stability [22] [19]. Psychrophiles, conversely, employ a strategy of structural loosening. They reduce the number and strength of stabilizing interactions, possess a less compact core, and incorporate more small residues like glycine, which collectively increase backbone flexibility and allow functional motion at low energy costs [21].

Visualizing the Key Structural Differences

The following diagram synthesizes the core structural concepts from the research, illustrating the network-based stabilization in thermophiles versus the reduced interaction strategy in psychrophiles.

Experimental Data & Quantitative Comparisons

Empirical data is crucial for understanding the functional outcomes of these structural adaptations. The following table quantifies key biophysical and functional parameters, drawing from direct experimental measurements and analyses.

Table 2: Experimental Data on Protein Stability and Dynamics

| Parameter | Thermophiles | Psychrophiles | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Temperature (Tm) | Can exceed 100°C [23] | Can be 20-30°C below mesophiles [23] | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) |

| Optimal Activity Range | Often 70°C - 120°C [21] | Often < 20°C [21] | Enzyme kinetics assay |

| Protein Diffusion Coefficient (DG) | Lower at respective physiological temps (e.g., ~1.5 Ų/ns for A. aeolicus at 370K) [23] | Higher at respective physiological temps (e.g., ~1.8 Ų/ns for P. arcticus at 317K) [23] | Quasi-elastic Neutron Scattering (QENS) |

| Dynamic Arrest Temperature | Coincides with cell death temperature [23] | Decoupled from cell death; occurs ~22°C above [23] | QENS & Molecular Dynamics (MD) |

| Catalytic Activity (kcat) | Often lower at mesophilic temps | Significantly higher at low temps (0-10°C) | Spectrophotometric assays |

A critical finding from recent research is the different relationship between protein dynamics and cell viability in these extremophiles. In thermophiles like Aquifex aeolicus, a sharp slowdown in protein diffusion—a dynamic arrest caused by the unfolding of a small fraction of the proteome—occurs precisely at the organism's cell death temperature (~370K) [23]. This suggests that the loss of proteome solubility and dynamics is a key factor in thermal death for these organisms. In stark contrast, the psychrophile Psychrobacter arcticus experiences this same dynamic arrest at a temperature (~317K) far above its cell death temperature (~295K) [23]. This indicates that psychrophiles do not die from a gelling of their cytoplasm, but likely from the loss of specific, critical enzymatic functions at low temperatures, underscoring a fundamental decoupling between proteome stability and viability.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To facilitate reproducibility and further research, this section outlines key methodologies used to generate the comparative data discussed in this guide.

Protocol 1: X-Ray Crystallography for Structural Determination

This protocol is used to solve high-resolution structures of extremozymes, enabling atomic-level analysis of stabilizing features like salt bridges and hydrophobic packing [24].

- 1. Protein Expression and Purification: Clone the target gene into an appropriate expression vector (e.g., for E. coli). Express the protein and purify it using chromatography methods (e.g., affinity, size exclusion) to homogeneity.

- 2. Crystallization: Screen for crystallization conditions using robotic systems and commercial screens. Optimize hits to grow large, single crystals suitable for diffraction.

- 3. Data Collection: Flash-cool the crystal in liquid nitrogen. Collect X-ray diffraction data at a synchrotron source. For example, the structure of a thermophilic malate dehydrogenase (1GV1) was determined at 2.50 Å resolution [24].

- 4. Structure Solution and Refinement: Solve the phase problem using molecular replacement or other phasing methods. Iteratively refine the model using programs like CNS, building the structure and optimizing its fit to the electron density map. Key refinement statistics to report include R-value Work and R-value Free [24].

Protocol 2: Quasi-Elastic Neutron Scattering (QENS) for Protein Dynamics

QENS measures the diffusive motion of proteins within the crowded cellular environment, providing insights into cytoplasmic fluidity and rigidity [23].

- 1. Sample Preparation: Grow bacterial cells (e.g., P. arcticus, A. aeolicus) to mid-log phase. To highlight the signal from proteins, the cells are typically transferred into a D₂O-based buffer, as deuterium reduces the neutron scattering signal from the solvent.

- 2. Data Acquisition: Load the sample into a sealed cell compatible with the neutron spectrometer. Experiments are performed on instruments like the IN16B spectrometer at the Institute Laue Langevin. Data is collected over a defined temperature range (e.g., from 200K to 370K) that encompasses the organism's physiological and lethal temperatures.

- 3. Data Analysis: The obtained spectra, the incoherent dynamic structure factor S(Q,E), are fitted with a model that decomposes the dynamics into global diffusion (translational and rotational motion of the whole protein) and local diffusion (internal motions). The global diffusion coefficient (DG) is a key output parameter, revealing how freely proteins move in the cytoplasm [23].

Workflow for Comparative Stability Analysis

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for a research project aimed at comparing the stability of extremophile enzymes, integrating the protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

This section catalogs essential materials and tools derived from the search results that are pivotal for research in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Taq DNA Polymerase | High-temperature DNA amplification (PCR) [25] [6] | Derived from Thermus aquaticus; Thermostable [25] |

| Halomonas bluephagenesis | Halophilic chassis for open, non-sterile fermentation [25] | Engineered to produce bioplastics (PHA) [25] |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Gene editing in extremophile chassis [25] [6] | Enables precise genomic modifications in non-model organisms [25] |

| Porousin Promoter Library | Regulating gene expression in halophiles [25] | A constitutive promoter library for Halomonas [25] |

| Specialized Growth Media | Cultivation of extremophiles under specific conditions [21] | High-salt for halophiles; specific pH for acidophiles/alkaliphiles [26] |

| L-Asparaginase | Food processing & cancer treatment [6] | Sourced from halotolerant Bacillus strains [6] |

The comparative analysis of thermophilic and psychrophilic proteins reveals two elegant, opposing solutions to the problem of environmental extreme: the reinforcement of structural rigidity versus the optimization of catalytic flexibility. These molecular blueprints, characterized by distinct amino acid usage, stabilizing interaction networks, and dynamic properties, are not merely academic curiosities. They provide a rich repository of design rules and components for biotechnology. Understanding these principles enables researchers to engineer enzymes with tailored stability, develop robust microbial chassis for industrial processes, and explore novel mechanisms for drug development where enzyme stability or flexibility is a critical factor. The continued integration of structural biology, biophysical dynamics, and synthetic biology will undoubtedly unlock further transformative applications inspired by life at the edge.

Genomic and Metabolic Adaptations Supporting Enzyme Function in Extreme Conditions

The study of extremophilic organisms—those thriving in conditions once considered inhospitable to life—has fundamentally reshaped our understanding of biological adaptability. Thermophiles and psychrophiles, adapted to high (55-80°C) and low (<15°C) temperatures respectively, represent remarkable case studies in evolutionary adaptation [27] [14]. These organisms possess specialized enzymatic machinery, known as extremozymes, that catalyze chemical reactions under conditions that would denature or inactivate their mesophilic counterparts [14]. The genomic and metabolic adaptations underlying these capabilities are not merely academic curiosities; they offer blueprints for biotechnological innovation, with applications spanning pharmaceutical development, industrial biocatalysis, and sustainable manufacturing [14] [28]. This review systematically compares the genomic foundations and metabolic network properties of extremophiles against mesophilic reference points, providing researchers with a structured framework for understanding enzyme stability-activity tradeoffs across the thermal spectrum.

Genomic Blueprints of Thermal Adaptation

Genome Architecture and Composition

Comparative genomic analyses reveal distinct evolutionary strategies in thermophiles and psychrophiles. Psychrophiles generally possess significantly larger genomes and more coding sequences (CDS) than thermophiles, suggesting a genetic repertoire for environmental sensing and metabolic flexibility in cold environments [27]. Conversely, thermophiles exhibit relatively compact genomes with limited variation in size, reflecting selective pressures for efficiency and stability at elevated temperatures [27].

A fundamental distinction lies in nucleotide composition. Thermophiles consistently demonstrate higher genomic G+C content, particularly at the first codon position, which enhances DNA stability through additional hydrogen bonding [27]. Psychrophiles, by contrast, favor A+T-rich codons, which reduce energy requirements for transcription and translation while potentially maintaining DNA flexibility at low temperatures [27].

Table 1: Comparative Genomic Features of Temperature-Adapted Microorganisms

| Genomic Feature | Thermophiles | Psychrophiles | Mesophiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average Genome Size | Smaller | Significantly Larger | Highly Variable |

| Number of Genes (CDS) | Fewer | Significantly More | Variable |

| Genomic G+C Content | Higher | Lower | Intermediate |

| Codon Preference | G+C-rich (GGC, GCG, GCC) | A+T-rich (TTA, AAA, ATT) | Balanced |

| Amino Acid Enrichment | Tyrosine (Y), Glutamate (E), Leucine (L) | Threonine (T), Methionine (M), Phenylalanine (F) | Mixed |

The distinct thermal niches of extremophiles are reflected in their proteomic compositions. Nearly two-thirds (13/20) of amino acids show significantly different abundance patterns when comparing extremophiles to mesophiles [27]. Thermophiles exhibit significant enrichment of tyrosine (Y), glutamate (E), and leucine (L), which contribute to increased hydrophobic interactions and salt bridges that stabilize protein structures at high temperatures [27]. Psychrophiles display increased abundance of threonine (T), methionine (M), phenylalanine (F), serine (S), and tyrosine (Y), which promote molecular flexibility and maintain catalytic activity at low temperatures [27] [14].

These compositional differences directly impact enzyme structure-function relationships. Psychrophilic enzymes often feature reced hydrogen bonding, fewer salt bridges, and reduced use of proline and arginine in loop regions, all contributing to enhanced molecular flexibility in cold environments [14]. Thermophilic enzymes counter thermal denaturation through increased hydrophobic interactions, additional disulfide bonds, and more compact oligomeric states [14].

Metabolic Network Adaptations

Metabolic Network Architecture

Genome-scale metabolic modeling reveals distinctive network properties adapted to extreme thermal environments. Psychrophiles, despite their larger genomes, maintain the lowest number of exchange reactions (for nutrient transport and waste excretion), significantly fewer than mesophiles [27]. This suggests reduced environmental interaction or more autonomous metabolic networks in cold-adapted organisms.

Both thermophiles and psychrophiles exhibit significantly fewer exchange reactions compared to mesophiles, indicating that extremophiles generally have more constrained interactions with their external environment compared to mesophilic organisms [27]. This metabolic "self-sufficiency" may represent a fundamental adaptation to environments where nutrient availability is limited or unpredictable.

Table 2: Metabolic Network Properties Across Thermal Adaptation Classes

| Metabolic Property | Thermophiles | Psychrophiles | Mesophiles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Metabolic Reactions | Lower | Highest | Intermediate |

| Exchange Reactions | Significantly Reduced | Lowest | Highest |

| Nutrient Import | Intermediate | Significantly Reduced | High |

| Metabolite Export | Significantly Reduced | Intermediate | High |

| Predicted Growth Rates | Lower | Higher | Variable |

Specialized Metabolic Pathways and Biochemical Reactions

Extremophiles employ specialized metabolic strategies tailored to their thermal niches. Psychrophiles maintain higher growth rates in their native environments, supported by metabolic networks that facilitate rapid nutrient assimilation and energy generation despite thermodynamic constraints [27]. Both extremophile groups exhibit distinct active metabolic reactions enriched with unique biochemical processes essential for coping with environmental stressors [27].

At the protein level, psychrophiles produce ice-binding proteins (IBPs) including antifreeze proteins that lower the freezing point of body fluids and prevent ice crystal formation [28]. Thermophiles invest in elaborate chaperone systems and heat shock proteins that prevent protein aggregation and facilitate refolding under thermal stress [28]. These specialized adaptations represent significant metabolic investments that are reflected in their respective network architectures.

Experimental Approaches for Investigating Extremozyme Adaptations

Enzyme Proximity Sequencing (EP-Seq)

Enzyme Proximity Sequencing (EP-Seq) represents a cutting-edge deep mutational scanning method that simultaneously resolves both stability and activity phenotypes for thousands of enzyme variants [29]. This approach leverages peroxidase-mediated radical labeling with single-cell fidelity to dissect the effects of mutations on folding stability and catalytic activity in a single experiment.

The core workflow involves two parallel branches:

- Expression Analysis: Enzyme variants are displayed on yeast surfaces, stained with fluorescent antibodies, and sorted via FACS into bins based on expression levels, which serve as a proxy for folding stability.

- Activity Analysis: A horseradish peroxidase-mediated phenoxyl radical coupling reaction converts oxidase activity into a fluorescent label on the cell wall, enabling sorting based on catalytic function.

Following sorting, next-generation sequencing of both branches enables computational determination of fitness scores for both expression (stability) and activity for each variant [29]. This powerful approach has revealed fundamental biophysical principles, including activity-based constraints that limit folding stability during natural evolution and identified distant "hotspot" regions where mutations can improve catalytic activity without sacrificing stability [29].

Multi-Omics Integration for Extremophile Characterization

Advanced multi-omics approaches provide comprehensive insights into extremophile adaptation by integrating complementary data layers [14] [28]. A representative workflow includes:

- Metagenomic Sequencing: 16S rRNA marker gene analysis or shotgun metagenomics for community profiling and functional gene identification.

- Metatranscriptomics: RNA-Seq analysis to identify actively expressed genes and regulatory responses to environmental conditions.

- Metaproteomics: Mass spectrometry-based protein identification and quantification to validate enzymatic expression and post-translational modifications.

This integrated approach was successfully applied to Thermus filiformis, revealing temperature-dependent physiological changes and identifying numerous thermostable enzymes with biotechnological potential, including amylases, pyrophosphatases, glucosidases, and galactosidases [14]. Such multi-omics frameworks enable researchers to move beyond gene catalogs to understand functional enzymatic adaptations in extreme environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for Extremophile Enzyme Studies

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| ModelSEED Platform | Genome-scale metabolic network reconstruction | Creating metabolic models from genomic data [27] |

| Yeast Surface Display | Protein expression and stability screening | Displaying enzyme variants for EP-Seq [29] |

| Horseradish Peroxidase (HRP) | Proximity labeling catalyst | Converting enzyme activity to fluorescent signal [29] |

| Tyramide-488 | Fluorescent labeling reagent | Activity-dependent cell staining in EP-Seq [29] |

| Illumina NovaSeq 6000 | High-throughput sequencing | Variant identification in DMS studies [29] |

| FACS Systems | Cell sorting based on fluorescence | Separating variants by expression/activity [29] |

| Site Saturation Mutagenesis | Comprehensive variant library generation | Creating mutant libraries for DMS [29] |

The comparative analysis of genomic and metabolic adaptations in extremophiles reveals fundamental design principles for enzyme function under thermal stress. Thermophiles achieve stability through G+C-rich genomes, compact metabolic networks, and amino acid compositions that favor rigid protein cores, while psychrophiles leverage A+T-rich codons, extensive genetic repertoires, and flexible enzyme architectures for cold activity. These contrasting strategies illustrate the evolutionary trade-offs between stability and activity that constrain natural enzyme evolution.

For pharmaceutical and industrial applications, these insights enable rational engineering of biocatalysts with tailored stability-activity profiles. The experimental frameworks outlined—particularly EP-Seq and multi-omics integration—provide roadmap methodologies for systematic enzyme characterization and engineering. As extremophile research continues to unveil nature's solutions to environmental challenges, the translation of these principles to biotechnology promises more robust, efficient, and specialized enzymes for drug development, biocatalysis, and sustainable manufacturing.

From Discovery to Application: Harnessing Extremozymes in Biomedicine and Industry

The pursuit of novel enzymes, particularly those from extremophiles (extremozymes), is a critical frontier in biotechnology and drug development [30] [18]. These enzymes function in conditions that are inhospitable to most life, and their stability offers immense potential for industrial catalysis, including in pharmaceutical synthesis [14] [30]. Accessing this resource, however, hinges on advanced discovery techniques. For decades, culture-based methods were the cornerstone of microbiology. More recently, metagenomic mining has emerged as a powerful, culture-independent approach [31] [32]. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two paradigms, framing them within ongoing research on the comparative stability of microbial versus extremophile enzymes. We summarize experimental data, detail protocols, and provide key resources to inform the strategies of researchers and scientists.

Principle and Workflow Comparison

The fundamental distinction between these techniques lies in their requirement for microbial cultivation.

- Culture-Based Methods rely on isolating and growing microorganisms in the laboratory on specific nutrient media. Once isolated, enzymes can be purified and characterized from these cultures [32].

- Metagenomic Mining bypasses the cultivation step entirely. It involves directly extracting environmental DNA (eDNA) from a sample, sequencing it, and using computational tools to identify and predict the functions of enzyme-encoding genes [31] [32].

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for each discovery pipeline.

Diagram: Enzyme Discovery Workflows

Performance and Application Analysis

The choice between culture-based and metagenomic methods involves trade-offs in scope, sensitivity, and functional output. The table below summarizes their comparative performance based on published studies.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Culture-Based and Metagenomic Discovery Techniques

| Feature | Culture-Based Methods | Metagenomic Mining |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Isolation and growth of microorganisms in the lab [32]. | Direct extraction and analysis of DNA from environmental samples [31] [32]. |

| Theoretical Coverage | Targets only the culturable minority (~1% of microbes) [30] [32]. | Provides access to the entire microbial community, including the uncultured majority [31] [32]. |

| Functional Output | Provides direct evidence of enzyme activity and allows for experimental characterization of stability and function [32]. | Predicts function from genetic sequence; requires heterologous expression for experimental validation [31]. |

| Key Limitations | Misses vast microbial diversity; labor-intensive and slow [33] [32]. | Does not prove enzyme function or stability directly; high computational cost; gene expression challenges [31] [32]. |

| Pathogen Detection (Sensitivity) | Gold standard for confirming viable pathogens but can be slow (e.g., 15-28 hours for positive culture) [34]. | High sensitivity; can detect pathogens at abundances as low as 0.01% and is less affected by prior antibiotic use [34] [35]. |

| Best Applications | Functional validation, physiological studies, and obtaining stable enzyme-producing strains for industrial scale-up [32] [36]. | Biodiversity exploration, discovery of novel gene sequences from uncultured hosts, and rapid pathogen screening [31] [34]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, this section outlines standard protocols for both techniques as applied in recent research.

Culture-Based Protocol for Pathogen Isolation

This protocol is adapted from a study detecting foodborne pathogens in Malaysian produce [33].

- Sample Homogenization: A 10 g sample is added to 270 mL of a 0.85% saline solution in a stomacher bag and homogenized for 2 minutes.

- Selective Enrichment: The homogenate is added to specific enrichment broths (e.g., Buffered Peptone Water for Salmonella) and incubated under optimal conditions for the target pathogen (e.g., 37°C for 24 hours).

- Plating and Isolation: The enriched broth is serially diluted in a 0.85% saline solution. The dilutions are plated onto selective agar media (e.g., XLD agar for Salmonella) using the spread plate method and incubated.

- Colony PCR Confirmation: Presumptive positive colonies are picked, and DNA is extracted via a boiled-cell method (heating at 100°C for 10 min). Conventional PCR with species-specific primers is used for final confirmation.

Shotgun Metagenomics Protocol for Microbiome Analysis

This protocol is synthesized from studies on oil reservoir microbiota and foodborne pathogens [33] [36].

- Genomic DNA (gDNA) Extraction: gDNA is extracted directly from the environmental or clinical sample using commercial kits (e.g., Nucleospin Food Kit). The extraction includes steps to lyse cells and purify the DNA, often with modifications to improve yield from complex matrices.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: The extracted gDNA is fragmented, and adapters are ligated to create a sequencing library. The library is then subjected to high-throughput shotgun sequencing on a platform such as Illumina.

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Quality Control & Assembly: Raw sequence reads are quality-filtered and trimmed. High-quality reads are assembled de novo into longer contigs.

- Binning & Taxonomic Profiling: Contigs are binned into Metagenome-Assembled Genomes (MAGs) based on sequence composition and abundance. Taxonomic classifiers like Kraken2/Bracken are used to determine microbial community composition [35].

- Functional Annotation: Genes are predicted within the contigs and MAGs. These are annotated against databases (e.g., KEGG, NCBI-NR) to identify putative enzymes, antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs), and virulence factors.

Case Study: Integrated Analysis of Petroleum Reservoirs

A study on high-salinity petroleum reservoirs in Tatarstan demonstrates the power of combining both methods [36].

- Metagenomic Analysis: 16S rRNA sequencing and reconstruction of 75 MAGs revealed a community dominated by sulfidogenic bacteria (e.g., Desulfobacterota) and fermentative bacteria (e.g., Halanaerobiaeota), along with methanogenic archaea (Methanohalophilus).

- Culture-Based Validation: Researchers isolated 20 pure cultures, including genera like Halanaerobium and Geotoga.

- Integrated Finding: The isolated fermentative bacteria were confirmed to produce oil-displacing metabolites (acids, alcohols, gases), highlighting their biotechnological potential for microbial enhanced oil recovery (MEOR). However, metagenomic data also showed that these metabolites could stimulate sulfidogenic bacteria, which cause corrosion. This integrated approach was crucial for designing an MEOR strategy that enhances recovery while suppressing corrosive side effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Kits for Enzyme Discovery Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Selective Agar Media | Supports the growth of specific microbial taxa while inhibiting others. | Isolating Listeria spp. from food samples using selective agars [33]. |

| Nucleospin Food Kit | Extracts high-quality genomic DNA from complex biological samples like food. | Preparing DNA for shotgun metagenomic sequencing of foodborne pathogens [33]. |

| Kraken2/Bracken | A system for fast, sensitive taxonomic classification of metagenomic sequences and abundance estimation. | Identifying and quantifying pathogens in simulated food metagenomes down to 0.01% abundance [35]. |

| Heterologous Expression Hosts | Surrogate organisms (e.g., E. coli) used to express and produce proteins from cloned foreign genes. | Producing and characterizing a novel esterase discovered from a compost metagenome [31]. |

Both culture-based and metagenomic techniques are indispensable for modern enzyme discovery. Culture-based methods provide the undeniable advantage of direct functional validation and access to viable isolates, which remain crucial for understanding physiology and scaling production. In contrast, metagenomic mining offers an unparalleled view of microbial diversity, enabling the discovery of novel genes from the vast uncultured majority. For research focused on the stability and function of extremophile enzymes, a synergistic approach is most powerful. Metagenomics can guide the targeted cultivation of elusive organisms and rapidly identify promising genetic targets, while traditional culturing remains essential for the experimental characterization that confirms an enzyme's stability and industrial potential.

The term "microbial dark matter" (MDM) describes the enormous fraction of microorganisms that refuse to grow in standard laboratory cultures, representing an estimated >95% of prokaryotic lineages in environments like marine sediments and hydrothermal vents [37]. This vast, unexplored biological terrain constitutes a hidden reservoir of novel enzymes, metabolic pathways, and biochemical functions with immense potential for biotechnology and drug development [14] [38]. Overcoming the challenge of MDM requires advanced, culture-independent techniques that can link genetic potential to biological function, enabling researchers to tap into this untapped resource for discovering robust industrial enzymes, including those from extremophiles [37] [39].

Two primary methodological paradigms have emerged to illuminate this microbial dark matter: single-cell genomics (SCG), which isolates and sequences the DNA of individual cells, and function-based screening, which directly assays metagenomic libraries for desired enzymatic activities [40] [41]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these core approaches, detailing their respective workflows, capabilities, and limitations. It is framed within a broader thesis on the comparative stability of enzymes, with a specific focus on the unique value of extremophile-derived enzymes, known for their extraordinary stability under industrial harsh conditions [14] [39].

Comparative Workflows: Two Pathways to Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the core workflows for single-cell genomics and function-based metagenomic screening, highlighting their distinct pathways from environmental sample to functional discovery.

Single-Cell Genomics: Illuminating Genomic Blueprints

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Single-cell genomics enables researchers to access the genetic material of individual uncultured cells directly from environmental samples. The standard workflow, as derived from the search results, involves several critical steps [40] [42]:

- Sample Preparation and Preservation: Environmental samples (e.g., biofilm, sludge, sediment) are collected and preserved to maintain cellular integrity, often using fixatives like ethanol or glutaraldehyde.

- Single-Cell Isolation: This is a crucial step where individual cells are separated from the complex community. While Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) is most common, a novel label-free single-cell dispensing system offers advantages. This microfluidic printer captures cells in picoliter droplets, assesses cell number and morphology via automated light microscopy, and deposits single cells into wells with minimal stress [42].

- Cell Lysis and Whole Genome Amplification: The membrane of the isolated cell is chemically or enzymatically lysed. The minimal genomic DNA is then amplified using methods like Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) to generate sufficient material for sequencing [40].

- Screening and Sequencing: Amplified genomes are often screened using 16S rRNA gene PCR to phylogenetically identify the captured cell. Subsequently, library preparation (e.g., with Illumina Nextera XT) and sequencing are performed to generate a Single Amplified Genome (SAG) [40] [42].

Performance and Key Experimental Data

Recent studies demonstrate the power of SCG in capturing novel microbial diversity. The table below summarizes quantitative data from a key study that utilized the novel single-cell dispensing approach [42].

Table 1: Genome Recovery Success Rates for Single-Cell Genomics

| Metric | Performance Data | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Recovery Rate | 81.5% (717 out of 880 sorted cells) | Label-free single-cell dispensing from wastewater [42] |

| 16S rRNA Analysis Success | 50.1% of amplified cells (359 out of 717) | Successful phylogenetic identification post-amplification [42] |

| Novel SAGs Recovered | 27 Single Amplified Genomes | Representing 15 novel Patescibacteria/CPR species, genera, and families [42] |

| Complementarity to Metagenomics | High (Recovery of lineages missed by MAGs) | Phylogenetically distinct SAGs were not captured by genome-resolved metagenomics of the same sample [42] |

Function-Based Screening: Direct Discovery of Novel Enzymes

Core Methodology and Experimental Protocol

Function-based metagenomic screening bypasses sequencing and directly tests for desired enzymatic activities, enabling the discovery of entirely novel genes with no similarity to known sequences [41]. The general workflow is as follows [41] [37]:

- Metagenomic Library Construction: Total environmental DNA is extracted and fragmented. These fragments are cloned into suitable expression vectors (plasmids, fosmids, or cosmids) and introduced into a surrogate host, typically Escherichia coli.

- Activity-Based Screening: The library of clones is subjected to an assay designed to detect the target activity. This is the core of the functional approach.

- Hit Identification and Validation: Clones exhibiting a positive signal in the assay are selected. The metagenomic insert is sequenced to identify the gene responsible for the activity, which is then characterized biochemically.

The screening step employs various strategies, each with specific protocols and detection methods:

- Agar Plate Screening: The simplest and most common method. Clones are grown on agar plates containing a substrate that produces a visual change upon enzymatic activity.

- Microtiter Plate Screening: A higher-throughput method where clones are grown in microtiter plates, and activity is measured spectrophotometrically or fluorometrically (e.g., using p-nitrophenyl derivatives) [41].

- Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (uHTS): Advanced methods like FACS-based screening and droplet-based microfluidics are used to screen libraries of immense size (e.g., >10^9 clones). These systems encapsulate single cells in water-in-oil droplets together with a fluorescent substrate, enabling the sorting of millions of cells per hour based on activity [41].

Performance and Key Experimental Data

Function-based screening has successfully identified a wide range of novel enzymes from diverse environments. The data below highlights its application and effectiveness.

Table 2: Representative Enzymes Discovered via Function-Based Screening

| Target Enzyme | Detection Method/Substrate | Source Environment | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Protease | Phenotypical detection / 1% skim-milk | Goat skin, desert sands, forest soil | Discovery of novel proteases active against insoluble protein substrates [41] |

| Esterase/Lipase | Phenotypical detection / 1% Tributyrin | Marine mud, sponge, alluvial soil | Identification of esterases and lipases with activity in high-salt or low-temperature conditions [41] |

| γ-Lactamase | Ninhydrin stain on filter overlay | Sulfolobus solfataricus (thermophile) | Discovery of a thermostable enzyme critical for synthesizing the anti-HIV drug Abacavir [39] |

| L-Aminoacylase | -- | Thermococcus litoralis (thermophile) | Identification of a thermostable enzyme with broad substrate specificity for unnatural amino acids [39] |

Comparative Analysis: Strengths, Limitations, and Synergy

The following table provides a direct comparison of the two methodologies, contextualizing their performance and utility for researchers.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Single-Cell Genomics and Function-Based Screening

| Aspect | Single-Cell Genomics (SCG) | Function-Based Screening |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Single Amplified Genomes (SAGs) - Genomic context of individual cells [42] | Novel enzyme genes with confirmed activity [41] |

| Key Strength | Accesses rare biosphere and cell-cell associations; provides full genomic context [42] | Discovers completely novel enzymes without prior sequence knowledge (functional dark matter) [41] [43] |

| Major Limitation | Genome amplification can be incomplete/biased; high cost [44] | Low hit rates; dependent on successful expression in a heterologous host [41] [37] |

| Throughput | Medium (hundreds to thousands of cells per run) [42] | Very High (millions of clones with uHTS) [41] |

| Ideal for Research on | Microbial ecology, evolution, and uncovering novel phyla (e.g., Patescibacteria) [42] [44] | Industrial enzyme discovery, particularly for biocatalysis and therapeutics [41] [39] |

| Role in Stability Research | Identifies genetic adaptations (e.g., in extremophiles) that confer stability at the genomic level [14] | Directly tests the stability and function of discovered enzymes under process-like conditions (e.g., high T, pH) [39] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of these advanced methodologies relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below lists key solutions for researchers embarking on MDM exploration.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microbial Dark Matter Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Relevant Context |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) | High-throughput, staining-based sorting of single cells from environmental samples for SCG [40] | Standard method for single-cell isolation; can cause cell stress [42] |

| Microfluidic Single-Cell Dispenser | Label-free, image-based isolation of single cells, minimizing stress for downstream genomics or cultivation [42] | An alternative to FACS; allows morphological selection [42] |

| Multiple Displacement Amplification (MDA) Kit | Isothermal whole-genome amplification of minute DNA amounts from a single cell [40] | Critical for SCG to generate sufficient DNA for sequencing from one cell [40] [42] |

| Fosmids / Cosmids | Large-insert cloning vectors for constructing metagenomic libraries, capturing large gene clusters [41] [37] | Essential for function-based screening to maintain large DNA fragments and operons [41] |

| Activity-Specific Substrates (e.g., AZCL-casein, Tributyrin) | Chromogenic or fluorogenic substrates used in agar or microtiter plate assays to detect enzymatic activity [41] | Enable visual detection of enzyme hits in functional metagenomic screens [41] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Preparation of sequencing-ready libraries from amplified genomic DNA for Illumina platforms [40] | Standardized protocol for sequencing SAGs and other low-input samples [40] |

Single-cell genomics and function-based metagenomic screening are powerful, complementary technologies in the campaign to overcome the challenge of microbial dark matter. SCG excels at revealing the genomic blueprint and ecological context of uncultured organisms, including extremophiles whose genetic adaptations hint at the stability of their encoded enzymes [14] [42]. In contrast, function-based screening directly uncovers novel enzymatic activities, even from genes with no known homologs, providing a direct path to robust biocatalysts like extremozymes that are already functional under industrial process conditions [41] [39].

For researchers focused on the comparative stability of microbial versus extremophile enzymes, a synergistic approach is most powerful. SCG can identify extremophile lineages and their unique genetic signatures, while functional screening can validate the stability and catalytic prowess of the enzymes these genes encode. By integrating these methodologies, the scientific community can systematically illuminate microbial dark matter, transforming it from a biological enigma into a boundless resource for drug development and industrial biotechnology.

The increasing demand for industrial enzymes that can withstand harsh process conditions—such as extreme temperatures, pH, and organic solvents—has driven significant interest in extremozymes derived from microorganisms inhabiting Earth's most challenging environments [3] [45]. These enzymes, native to extremophiles, offer superior activity and stability under non-standard conditions compared to their mesophilic counterparts, making them highly desirable for applications in biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and bioremediation [46]. However, a major challenge impedes their widespread adoption: the difficulty of cultivating the source extremophilic organisms on an industrial scale due to their fastidious growth requirements and low biomass yields [45].

Heterologous expression in mesophilic hosts presents a powerful solution to this bottleneck. This strategy involves cloning the extremozyme-encoding gene from the extremophile into a robust, easily cultivated mesophilic host such as Escherichia coli or Bacillus subtilis, enabling large-scale production of the enzyme under standard laboratory and industrial conditions [46]. This guide objectively compares the leading mesophilic host systems for extremozyme production, providing experimental data and methodologies to inform researchers and drug development professionals in their selection of an appropriate expression platform.

Comparing Mesophilic Host Systems for Extremozyme Production

The success of heterologous expression hinges on selecting an appropriate host-vector system. The table below compares the key characteristics of the most commonly employed mesophilic hosts for extremozyme production.

Table 1: Comparison of Mesophilic Host Systems for Heterologous Extremozyme Production

| Host System | Optimal Expression Vector Features | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal for Extremozyme Types |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | Vectors with T5/lac promoter [46], pUC origin (high copy) [47], RSF origin (stable medium copy) [47]. | Rapid growth, high transformation efficiency, well-characterized genetics, high protein yields [46]. | Improper folding of complex proteins, formation of inclusion bodies, lack of post-translational modifications [48]. | Thermophilic enzymes [48], psychrophilic catalases [46], amine-transaminases [46]. |