From Algorithm to Lab Bench: A Researcher's Guide to Validating Machine Learning Predictions for Enzyme Activity

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously validate machine learning predictions of enzyme activity.

From Algorithm to Lab Bench: A Researcher's Guide to Validating Machine Learning Predictions for Enzyme Activity

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously validate machine learning predictions of enzyme activity. Covering foundational concepts to advanced applications, it explores hybrid methodologies that integrate in silico models with high-throughput experimental data from peptide arrays, cell-free systems, and mass spectrometry. The content addresses critical challenges including data scarcity, model interpretability, and generalization, while presenting comparative analyses of validation techniques and their success rates in predicting substrates for enzymes like methyltransferases and deacetylases. This guide serves as an essential resource for bridging computational predictions with experimental confirmation in enzyme engineering and drug discovery.

The Critical Need for Validation in Machine Learning-Based Enzyme Discovery

Understanding the Validation Gap in Computational Enzyme Function Prediction

The exponential growth of genomic data has created a massive challenge for experimental biology: between 30% and 70% of proteins in any given genome have no experimentally assigned function, a knowledge shortfall termed the protein "unknome" [1]. Computational methods, particularly machine learning (ML), have emerged as powerful tools to address this gap by predicting enzyme functions from sequence and structural data. However, these methods face a critical validation gap—a disconnect between computational predictions and experimentally verified functions that limits their reliability for research and drug development.

This validation gap manifests in several ways: models often fail to predict novel functions not represented in their training data, make logical errors that human experts avoid, and struggle with generalizability across different enzyme families [1]. A large-scale community-based assessment revealed that nearly 40% of computational enzyme annotations are erroneous [2], highlighting the serious nature of this problem. As pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies increasingly rely on computational predictions for enzyme target identification and metabolic pathway engineering, understanding and addressing this validation gap becomes paramount for accelerating drug discovery and development.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Prediction Tools

Performance Metrics Across Prediction Platforms

Table 1: Comparison of enzyme function prediction tools and their performance characteristics

| Tool Name | Primary Methodology | EC Prediction Level | Reported Accuracy | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOLVE [2] | Ensemble learning (RF, LightGBM, DT) | L1-L4 (full EC number) | 89.7% (enzyme vs. non-enzyme) | Limited to 6-mer features due to memory constraints |

| EZSpecificity [3] | Graph neural network with cross-attention | Substrate specificity | 91.7% (experimental validation) | Requires structural information for optimal performance |

| CataPro [4] | Deep learning with protein language models | Kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) | Superior to baseline models | Performance varies with enzyme family |

| ProteInfer [2] | Deep neural networks | EC classes | Not specified | Cannot reliably differentiate enzyme vs. non-enzyme |

| CLEAN [2] | Similarity learning | EC classes | Not specified | Struggles with novel functions |

| DeepEC [2] | Convolutional neural networks | EC classes | Not specified | Limited interpretability |

Table 2: Data requirements and scalability of prediction tools

| Tool | Sequence Data | Structural Data | Substrate Information | Training Set Size | Computational Demand |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SOLVE | Required (primary sequence) | Not required | Not required for EC prediction | 283,902 annotated sequences | Moderate (6-mer tokenization) |

| EZSpecificity | Required | Required for optimal performance | Required (substrate specificity) | Comprehensive enzyme-substrate database | High (3D structure processing) |

| CataPro | Required | Not required | Required (SMILES notation) | Latest BRENDA and SABIO-RK entries | High (language model embeddings) |

| General ML Models [5] | Required | Optional | Molecular descriptors | Varies by implementation | Low to High |

The performance comparison reveals significant variation in accuracy across different prediction tasks. While SOLVE achieves 89.7% accuracy in distinguishing enzymes from non-enzymes and EZSpecificity reaches 91.7% accuracy in identifying reactive substrates, this high performance often comes with specific data requirements and computational costs [2] [3]. The generalization ability of these models remains a concern, as models designed for specific enzyme families typically outperform general models [5].

A critical limitation across most tools is their inability to predict novel functions not represented in training data. Current ML methods largely fail to make novel predictions and frequently make basic logic errors that human annotators avoid by leveraging contextual knowledge [1]. This represents a fundamental validation gap where computational predictions diverge from biologically plausible functions.

Experimental Validation Protocols

Standard Validation Workflow for Enzyme Function Prediction

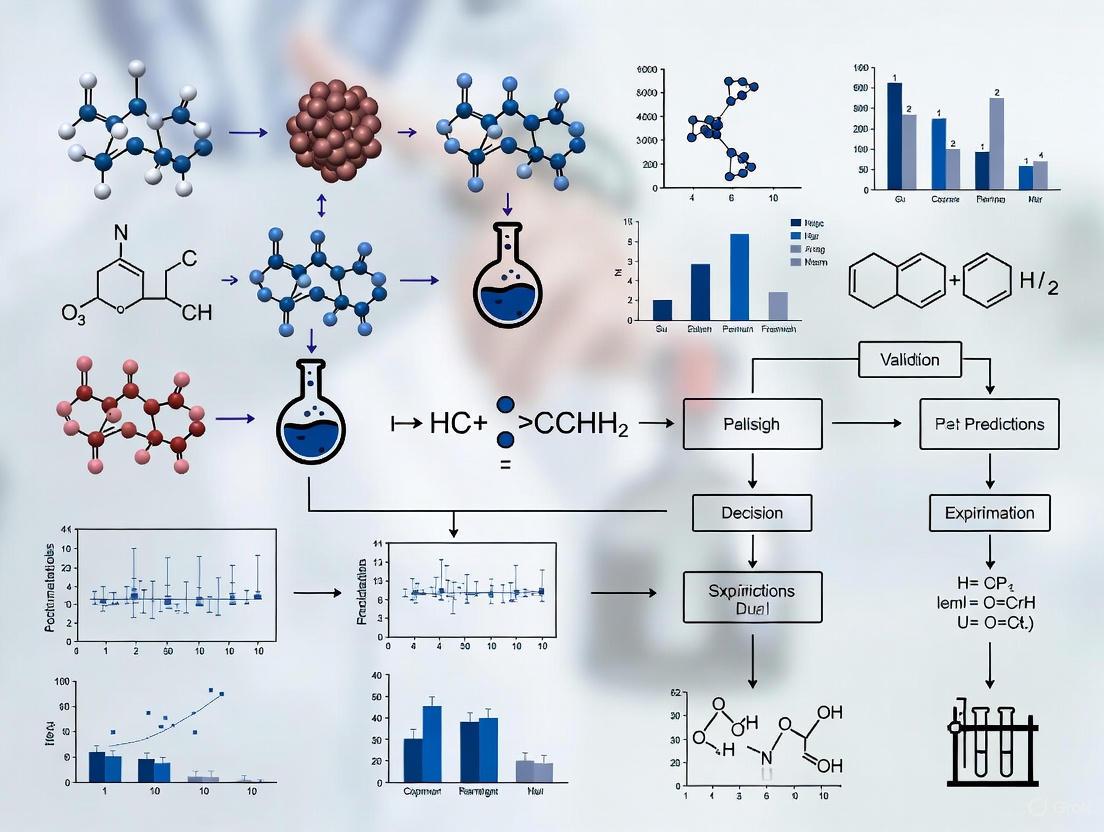

Diagram 1: Experimental validation workflow for computational predictions. This multi-stage process helps bridge the validation gap by progressively testing computational predictions through experimental methods.

EZSpecificity Validation Protocol for Substrate Specificity

The EZSpecificity model employed rigorous experimental validation using halogenases and 78 potential substrates. The protocol included [3]:

- Model Training: Training on a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions at sequence and structural levels

- Prediction Phase: Application to eight halogenase enzymes across 78 substrate candidates

- Experimental Testing: In vitro enzymatic assays to verify predicted reactive substrates

- Performance Assessment: Comparison of predictions against experimental results, achieving 91.7% accuracy in identifying single potential reactive substrates

This validation approach significantly outperformed state-of-the-art models, which achieved only 58.3% accuracy on the same task [3]. The dramatic performance difference highlights how validation specificity must match the prediction task.

CataPro Kinetic Parameter Validation Framework

CataPro addressed the validation gap for kinetic parameters through unbiased dataset construction and experimental confirmation [4]:

Unbiased Dataset Creation:

- Collection of kcat and Km entries from BRENDA and SABIO-RK databases

- Sequence clustering at 0.4 similarity threshold using CD-HIT

- Creation of ten enzyme groups for cross-validation

Model Architecture:

- Enzyme sequence encoding using ProtT5-XL-UniRef50 (1024-dimensional vectors)

- Substrate representation using MolT5 embeddings and MACCS keys fingerprints

- Neural network integration of enzyme and substrate features

Experimental Validation:

- Identification of SsCSO enzyme with 19.53× increased activity over initial enzyme

- Directed evolution to further improve activity by 3.34×

- Demonstration of practical application in enzyme discovery and engineering

Knowledge and Data Limitations

Table 3: Sources of validation gaps in computational enzyme function prediction

| Gap Category | Description | Impact on Prediction Reliability |

|---|---|---|

| Evidence Gap [6] | Contradictory findings between computational predictions and experimental results | Creates uncertainty about which predictions to trust for experimental follow-up |

| Knowledge Gap [6] | Complete lack of information about certain enzyme functions | Prevents validation of novel function predictions beyond training data scope |

| Methodological Gap [6] | Inadequate validation methods for certain prediction types | Leads to overestimation of model performance on real-world tasks |

| Practical-Knowledge Gap [6] | Disconnect between computational and experimental practices | Reduces adoption and utility of predictions for experimentalists |

The validation gap in computational enzyme function prediction stems from multiple sources, with data quality and quantity being fundamental limitations. Current models are constrained by the less than 0.5% to 15% of proteins in UniProtKB that have experimental data linkages [1]. This creates a fundamental knowledge void that affects model training and validation.

Database annotation errors further compound this problem. Error types include [1]:

- Failure to capture literature: Proteins annotated as unknown when functions have been published

- Overannotation of paralogs: Wrong annotation propagation to non-isofunctional paralogous groups

- Curation mistakes: Incorrect data capture or outdated functional annotations

- Experimental mistakes: Published data that has been refuted by other studies

These database issues mean that models are often trained on flawed ground truth data, creating a propagation of errors that widens the validation gap.

Technical Limitations in Model Architecture

Current ML approaches face several technical limitations that contribute to the validation gap:

Sequence Similarity Bias: Models often perform well on sequences similar to training data but fail to generalize to novel folds or distant homologs [1] [4].

Feature Extraction Limitations: Many models rely on simplified feature representations (e.g., k-mer tokenization in SOLVE) that may miss critical structural determinants of function [2].

Explainability Deficits: Many deep learning models function as "black boxes," providing predictions without mechanistic insights that would help experimentalists prioritize validation efforts [1].

The SOLVE framework addresses this last point by incorporating Shapley analysis to identify functional motifs at catalytic and allosteric sites, enhancing model interpretability [2]. This represents an important step toward closing the validation gap through explainable artificial intelligence (XAI).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Databases

Table 4: Essential research reagents and databases for enzyme function prediction and validation

| Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UniProtKB [1] [5] | Database | Protein sequence and functional information | 248+ million structures (569,793 reviewed) | Contains redundant and unreviewed data |

| BRENDA [5] [4] | Database | Enzyme functional and metabolic information | 32+ million sequences, 90,000 enzymes | Slow updates, requires biochemistry expertise |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [5] [2] | Database | 3D structural information | 208,066+ experimental structures | Limited structural coverage of enzyme space |

| PubChem [4] | Database | Chemical compound information | Canonical SMILES for substrates | Variable annotation quality |

| PARROT [7] | Computational Tool | Prediction of enzyme allocation | Minimizes Manhattan distance between reference and alternative conditions | Condition-specific limitations |

| EC Number System [2] | Classification | Hierarchical enzyme function categorization | 7 main classes with 4 specificity levels | Does not capture enzyme promiscuity |

The validation gap in computational enzyme function prediction represents both a significant challenge and opportunity for the research community. While current tools like SOLVE, EZSpecificity, and CataPro show impressive performance in specific domains, their reliability is ultimately constrained by training data limitations, methodological constraints, and insufficient integration with experimental validation pipelines.

Closing this gap requires a multi-faceted approach: (1) developing more sophisticated model architectures that better capture the structural determinants of enzyme function; (2) creating higher-quality, experimentally-validated training datasets; (3) implementing explainable AI techniques to provide mechanistic insights alongside predictions; and (4) establishing standardized validation protocols that rigorously assess model performance on biologically relevant tasks.

For researchers and drug development professionals, this means adopting a critical perspective on computational predictions while recognizing their value as hypothesis-generation tools. The most effective strategy combines computational predictions with experimental validation in an iterative feedback loop, using each to inform and refine the other. As these approaches mature, they hold the potential to dramatically accelerate enzyme discovery and engineering for therapeutic applications.

Predicting enzyme activity using machine learning (ML) represents a frontier at the intersection of computational biology and biochemical research. As catalytic proteins that expedite biochemical reactions within cellular frameworks, enzymes play indispensable roles in health, disease, and industrial biotechnology [2]. The accurate prediction of their functions—traditionally categorized through the four-level Enzyme Commission (EC) number system—remains challenging despite advances in computational methods [2]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates contemporary ML platforms for enzyme function prediction, focusing on their respective approaches to overcoming the central challenges of data scarcity and experimental translation. We analyze performance metrics across multiple prediction tasks, detail experimental validation methodologies, and provide resources to facilitate implementation within research and drug development workflows.

Comparative Analysis of Machine Learning Platforms

ML platforms for enzyme function prediction employ diverse architectures ranging from ensemble methods to sophisticated graph neural networks. The performance of these platforms varies significantly across different prediction tasks, from broad enzyme class identification to specific substrate recognition.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Machine Learning Platforms for Enzyme Function Prediction

| Platform Name | Architecture/Approach | Primary Application | Reported Accuracy/Performance | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Hybrid Approach [8] | Combines ML with peptide array experiments | Identifying PTM sites for specific enzymes (e.g., SET8, SIRT1-7) | 37-43% of proposed PTM sites experimentally validated | Integrates high-throughput experimental data for training |

| EZSpecificity [3] | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network | Predicting enzyme substrate specificity | 91.7% accuracy in identifying single potential reactive substrate | Leverages 3D structural information of enzyme active sites |

| SOLVE [2] | Ensemble (RF, LightGBM, DT) with optimized weighted strategy | Enzyme vs. non-enzyme classification & EC number prediction | High accuracy in L1 (class) to moderate accuracy in L4 (substrate) prediction | Uses only primary sequence; interpretable via Shapley analysis |

| Deep Learning Methods (e.g., DeepEC, CLEAN) [2] | Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) & Transformers | EC number prediction from sequence | Effective for main class prediction, varies at substrate level | High-throughput capability for large-scale annotation |

The performance divergence between platforms highlights a fundamental trade-off between specificity and data requirements. EZSpecificity's remarkable 91.7% accuracy in identifying reactive substrates demonstrates the value of incorporating 3D structural information, while SOLVE achieves commendable performance using only sequence-based features, enhancing its applicability to enzymes without solved structures [3] [2]. The ML-hybrid approach bridges computational and experimental domains by generating enzyme-specific training data through peptide arrays, addressing the critical challenge of limited and non-representative training data [8].

Table 2: Performance Metrics Across Enzyme Prediction Hierarchy Levels for SOLVE [2]

| Prediction Task | Model/Metric | Precision | Recall | F1-Score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enzyme vs. Non-enzyme | LightGBM | 0.98 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.97 |

| Main Enzyme Class (L1) | LightGBM | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.94 | 0.94 |

| Subclass (L2) | LightGBM | 0.90 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.89 |

| Sub-subclass (L3) | LightGBM | 0.86 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.84 |

| Substrate (L4) | LightGBM | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.78 |

Performance consistently decreases across all models at lower EC hierarchy levels, with substrate-level prediction (L4) presenting the most significant challenge. This pattern reflects both increasing class imbalance and the finer functional distinctions required at this level [2]. SOLVE's ensemble framework, which integrates Random Forest (RF), Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LightGBM), and Decision Tree (DT) models with an optimized weighting strategy, demonstrates how combining multiple algorithms can enhance robustness across hierarchical levels [2].

Experimental Validation Frameworks

In Vitro Validation of PTM Predictions

The ML-hybrid approach for identifying post-translational modification sites employs a rigorous experimental workflow to validate computational predictions [8]. This methodology includes:

- Peptide Array Synthesis: Chemically synthesizing a representative PTM proteome using high-density peptide arrays that incorporate known and potential modification sites.

- Enzyme Incubation: Exposing peptide arrays to active enzyme constructs (e.g., SET8_{193-352} for methylation studies) under optimized reaction conditions.

- Activity Quantification: Measuring enzymatic activity through relative densitometry of peptide spots, followed by motif generation using software such as PeSA2.0 to determine sequence preferences.

- Mass Spectrometry Confirmation: Validating dynamic modification status of predicted substrates in cellular contexts through mass spectrometry analysis, which confirmed the deacetylation of 64 unique sites for SIRT2 in the case of sirtuin deacetylases [8].

This combined approach generated a performance increase of 37-43% validation rates for proposed PTM sites compared to traditional in vitro methods across separate enzyme classes [8].

Specificity Validation for Enzyme-Substrate Pairs

For predicting direct enzyme-substrate relationships, EZSpecificity employed experimental validation with eight halogenases and 78 substrates, demonstrating its superior capability to identify single potential reactive substrates with 91.7% accuracy, significantly outperforming the state-of-the-art model which achieved only 58.3% accuracy [3]. This validation framework establishes a benchmark for assessing real-world predictive performance in identifying functional enzyme-substrate pairs.

Functional Validation of Engineered Enzymes

Beyond natural enzyme function, validation pipelines extend to engineered enzyme systems. A comprehensive framework for validating surface-displayed carbonic anhydrase constructs spans multiple organisms (E. coli, Caulobacter crescentus, Synechococcus elongatus) and connects molecular-level validation with functional outcomes [9]. This multi-phase approach includes:

- Surface Display Verification: Combining cell fractionation, trypsin accessibility assays, and immunodetection (SDS-PAGE, Western blot) to confirm proper localization and extracellular exposure.

- Enzymatic Activity Measurement: Employing both direct (Wilbur-Anderson assay measuring CO₂ hydration kinetics) and indirect (esterase-based colorimetric assay) activity measurements across temperature and pH gradients.

- Functional Outcome Assessment: Quantifying microbially induced calcium carbonate precipitation through calcium depletion assays using O-cresolphthalein complexone methods, linking enzyme activity to macroscopic functional outcomes [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Implementation of ML-guided enzyme research requires specific reagents and methodologies. The following table details essential research reagents and their applications in validation workflows.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Enzyme Validation Studies

| Reagent/Assay | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays [8] | High-throughput representation of protein segments for enzyme activity screening | Substrate specificity profiling for PTM-inducing enzymes | Allows testing of thousands of sequence variants in parallel |

| Abcam CA Activity Assay Kit (ab284550) [9] | Measures esterase activity of carbonic anhydrase via chromophore release | Standardized benchmarking of CA enzymatic performance | Colorimetric readout (405 nm); uses proprietary ester substrate |

| Wilbur-Anderson Assay [9] | Quantifies CO₂ hydration kinetics via pH change | Direct measurement of CA catalytic efficiency | pH indicator (phenol red); measures rate of proton production |

| O-Cresolphthalein Complexone (O-CPC) [9] | Detects calcium depletion through colorimetric change | Indirect measurement of calcium carbonate precipitation | Lighter color indicates greater precipitation; high-throughput compatible |

| Trypsin Accessibility Assay [9] | Confirms extracellular exposure of surface-displayed enzymes | Localization validation for engineered enzyme constructs | Proteolytic cleavage of surface-exposed domains |

| Anti-Myc Antibodies [9] | Immunodetection of recombinant fusion proteins | Verification of protein expression and localization | Used with colorimetric staining (HRP/4-Chloro-1-naphthol) |

These reagents enable researchers to move from computational predictions to experimental validation across multiple dimensions, including expression, localization, activity, and functional outcomes. The combination of standardized commercial kits and customizable in-house assays provides flexibility for different research contexts and budget constraints.

Integrated Workflow: From Prediction to Validation

Successful translation of ML predictions into experimentally validated findings requires systematic progression through computational and experimental phases. The integrated workflow below illustrates this process from initial data collection to functional validation.

This integrated workflow emphasizes the iterative nature of ML-guided enzyme research, where experimental findings can refine computational models, and predictions can guide targeted experimental validation. The ML-hybrid approach exemplifies this integration by using high-throughput in vitro peptide array experiments to generate training data for ML models specific to each PTM-inducing enzyme [8]. This creates a virtuous cycle where experimental data improves model accuracy, which in turn generates higher-quality predictions for further experimental testing.

Machine learning platforms for enzyme function prediction have demonstrated significant advances in overcoming the dual challenges of data scarcity and experimental translation. Ensemble methods like SOLVE provide robust performance across enzyme classification hierarchies using only sequence information, while specialized architectures like EZSpecificity achieve remarkable accuracy in substrate specificity prediction by incorporating structural data. The most successful approaches combine computational predictions with systematic experimental validation frameworks, including peptide arrays, activity assays, and functional outcome measurements. As these technologies mature, they promise to accelerate enzyme discovery and characterization for therapeutic development and industrial applications. Researchers should select platforms based on their specific prediction needs, considering the trade-offs between data requirements, interpretability, and specificity, while implementing rigorous validation workflows to bridge computational predictions and biological function.

In the field of enzyme research, machine learning (ML) models are powerful tools for predicting enzyme-substrate interactions, a task fundamental to drug development and synthetic biology. However, a model's theoretical performance is only the first step; true validation is achieved through a multi-faceted approach combining robust computational metrics with rigorous experimental confirmation. This guide compares the current methodologies and success metrics for validating ML predictions in enzyme activity research.

Defining Validation: From Computational Scores to Lab Bench

A validated ML prediction in enzyme research is one where a computational forecast is conclusively proven through experimental evidence. This process involves two critical phases:

- Computational Validation: Using metrics to evaluate the model's predictive performance on held-out data.

- Experimental Validation: Conducting laboratory experiments to physically verify the model's predictions on novel substrates or enzymes.

The table below summarizes the core metrics used in the computational validation phase.

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Interpretation in Enzyme Research |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | Accuracy, Precision, Recall | Measures the proportion of correct predictions overall, true positives among predicted positives, and true positives among all actual positives [10] [11]. |

| Composite Scores | F1-Score, AUC-ROC | F1 balances precision and recall. AUC-ROC evaluates the model's ability to rank positive substrates higher than negative ones [10] [11]. |

| Regression Metrics | RMSE, R-Squared | Used for predicting continuous values like catalytic efficiency (kcat/Km); RMSE measures error magnitude, while R-squared measures variance explained [11]. |

Comparative Performance of ML Tools in Enzyme Research

Several advanced ML models have been developed specifically for predicting enzyme function and substrate specificity. Their performance, when compared objectively, highlights the rapid evolution in the field.

Table: Comparison of ML Models for Enzyme-Substrate Prediction

| Model Name | Key Approach | Reported Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Hybrid (for PTM Enzymes) | Combines peptide array data with ML to predict substrates for enzymes like SET8 and SIRTs [12]. | Correctly predicted 37-43% of proposed novel PTM sites [12] [13]. | Mass spectrometry confirmed dynamic methylation status of SET8 substrates and deacetylation of 64 unique sites for SIRT2 [12]. |

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention graph neural network trained on a comprehensive enzyme-substrate database [14] [3]. | 91.7% accuracy in identifying reactive substrates for halogenases; outperformed existing model ESP (58.3%) [14] [3]. | Experimentally tested with 8 halogenase enzymes and 78 substrates, confirming top predictions [14]. |

| CataPro | Deep learning model using pre-trained protein language models and molecular fingerprints to predict kinetic parameters (kcat, Km) [4]. | Demonstrated enhanced accuracy and generalization on unbiased datasets for predicting catalytic efficiency [4]. | Identified and engineered an enzyme (SsCSO) with 19.53x increased activity, then further improved it by 3.34x [4]. |

Experimental Protocols for Validating Predictions

A model's high accuracy on a test set is promising, but its true value is demonstrated when it correctly predicts outcomes in a real laboratory setting. The following are detailed protocols for key validation experiments cited in the comparison table.

Protocol 1: Peptide Array-Based Validation for PTM Enzymes

This methodology was used to validate the "ML-Hybrid" model for enzymes that introduce or remove post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as the methyltransferase SET8 [12].

- Peptide Array Synthesis: Chemically synthesize high-density peptide arrays on cellulose membranes. The arrays represent a library of protein sequences from the proteome, centered on potential modification sites (e.g., lysine residues).

- Enzyme Incubation: Express and purify the active enzyme of interest (e.g., SET8). Incubate the peptide arrays with the enzyme and its necessary co-factors (e.g., S-adenosylmethionine for methyltransferases).

- Detection of Modification: Use enzyme-specific antibodies (e.g., anti-methyllysine) that are conjugated to a fluorescent or chemiluminescent tag. Incubate these antibodies with the peptide array.

- Signal Quantification: Scan the arrays and quantify the signal intensity for each peptide spot using densitometry. A strong signal indicates a successful enzymatic modification.

- Data Analysis: Compare the results to the model's predictions. A successfully validated prediction shows a strong modification signal on a peptide that the model scored as a high-probability substrate.

Protocol 2: In-solution Enzyme Activity Assay for Specificity

This general-purpose protocol is used to validate substrate specificity predictions, such as those made by tools like EZSpecificity [14]. It confirms whether an enzyme acts on a predicted substrate in a physiologically relevant solution.

- Reaction Setup: Prepare reaction mixtures containing the purified enzyme, the predicted substrate, and the required buffer and cofactors (e.g., NAD+ for dehydrogenases).

- Incubation and Time-Point Sampling: Allow the reaction to proceed at a controlled temperature. At specific time intervals, withdraw aliquots from the reaction mixture and quench the reaction (e.g., by adding acid or heating).

- Product Detection and Quantification:

- Chromatography: Use techniques like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) or Gas Chromatography (GC) to separate the substrate from the reaction product.

- Mass Spectrometry (MS): Couple the chromatography system to a mass spectrometer to identify and quantify the product based on its mass-to-charge ratio. This was used to validate deacetylation sites for SIRT2 [12].

- Kinetic Analysis: Measure the initial rate of product formation across a range of substrate concentrations. This data allows for the calculation of kinetic parameters like Km and kcat, which can be compared to values predicted by models like CataPro [4].

The logical relationship between computational and experimental validation can be visualized as a sequential workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

The experimental validation of ML predictions relies on a suite of essential reagents and computational resources.

Table: Essential Reagents and Resources for Experimental Validation

| Item | Function in Validation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays | High-throughput screening of potential enzyme substrates by displaying a vast library of peptide sequences [12]. | Identifying novel methylation sites for SET8 [12]. |

| Affinity-tagged Enzymes | Allows for purification of recombinantly expressed enzymes to ensure experimental results are due to the enzyme of interest. | Purifying active SET8 construct for peptide array incubation [12]. |

| Modification-Specific Antibodies | Detect the presence of specific PTMs (e.g., methylation, acetylation) on substrates after enzymatic reaction [12]. | Anti-methyllysine antibody to detect SET8 activity on arrays [12]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | The gold standard for confirming the identity and specific site of a modification on a protein or peptide substrate [12]. | Validating the deacetylation of 64 unique sites on SIRT2 [12]. |

| Public Databases (BRENDA, UniProt) | Provide curated data on enzymes and substrates for model training and benchmarking [5] [4]. | Used by CataPro to train on kcat and Km values [4]. |

Key Takeaways for Researchers

Validating an ML prediction in enzyme activity is a multi-step process that requires more than a high accuracy score. A robustly validated prediction is one that is not only precise on historical data but also holds up under rigorous laboratory testing with novel data. The most convincing studies use orthogonal experimental methods—such as peptide arrays followed by mass spectrometry—to provide conclusive evidence that a predicted enzyme-substrate interaction is genuine. As the field progresses, the integration of more diverse data, including structural information and deeper kinetic parameters, will further solidify the role of ML as an indispensable tool in enzyme research and drug development.

The integration of machine learning (ML) into enzyme research has transformed the field, offering powerful tools for predicting catalytic activity, substrate specificity, and enzyme classification. As computational methods become increasingly sophisticated, it is crucial to recognize their inherent limitations, particularly when deployed without experimental validation. This case study examines the specific constraints of purely in silico prediction methods through the lens of enzyme activity research, highlighting how computational insights must be integrated with experimental approaches to generate reliable, biologically relevant findings. We explore these limitations through concrete examples spanning enzyme classification, catalytic activity prediction, and substrate identification, providing a framework for researchers to critically evaluate computational predictions in their own work.

The appeal of purely computational approaches is understandable: they offer speed, scalability, and cost-efficiency unmatched by traditional laboratory methods. However, as this analysis demonstrates, even the most advanced algorithms face fundamental challenges in capturing the complex biophysical reality of enzymatic function, often leading to inaccurate predictions that can misdirect research efforts if not properly validated.

Key Limitations of Purely In Silico Methods

The Integration Gap Between Activity Prediction and Structural Annotation

A fundamental limitation of many computational tools is their fragmented approach to enzyme characterization. Most ML tools specialize in either predicting enzymatic activity (e.g., assigning Enzyme Commission/EC numbers) or identifying structural features like binding pockets, but fail to connect these two aspects comprehensively [15].

The CAPIM (Catalytic Activity and Site Prediction and Analysis Tool In Multimer Proteins) pipeline was developed specifically to address this fragmentation by integrating three established tools: P2Rank for binding pocket identification, GASS for catalytic residue annotation and EC number assignment, and AutoDock Vina for functional validation via substrate docking [15]. This integrated approach bridges the critical gap between high-level functional classification and residue-level mechanistic detail that plagues many purely in silico methods.

Table 1: Tools for Enzyme Function Prediction and Their Limitations

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Limitations | Experimental Validation Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAPIM | Integrates binding site identification, catalytic residue annotation, and docking | Limited to structure-based predictions; requires quality structural data | Yes, for functional confirmation |

| SOLVE | EC number prediction from sequence | Cannot differentiate enzymes from non-enzymes reliably; struggles with novel sequences | Yes, for novel sequence annotation |

| DeepEC | EC number prediction | Purely sequence-based; lacks structural context | Yes, for substrate specificity determination |

| GASS | Active site detection and EC number assignment | Template-dependent; may miss novel active site architectures | Yes, for confirmation of catalytic residues |

Overreliance on Sequence-Based Predictions Without Structural Context

Many enzyme function prediction tools, including SOLVE and DeepEC, rely heavily on sequence information alone, leveraging evolutionary conservation and sequence motifs to infer function [15] [2]. While these methods can be effective for high-throughput annotation, they fundamentally neglect the structural context essential for understanding mechanism and substrate specificity.

The SOLVE method exemplifies both the power and limitations of sequence-based approaches. While it achieves impressive accuracy in EC number prediction using only tokenized subsequences from primary protein sequences, it struggles to reliably differentiate between enzyme and non-enzyme sequences, potentially leading to misassignment of EC numbers to non-enzymatic proteins [2]. This limitation is particularly problematic when working with novel sequences that lack close homologs in training datasets.

Structural context proves critical for understanding allosteric regulation mechanisms, as demonstrated in research on Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SauCas9). Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that allosteric inhibition by AcrIIA14 protein involves complex conformational changes across multiple domains (REC, L1, L2, and PI) that would be impossible to predict from sequence alone [16]. This case highlights how purely sequence-based methods miss crucial regulatory mechanisms that operate at the structural level.

Inability to Accurately Model Multimeric and Multidomain Enzymes

Most structure-based computational tools restrict their input to single protein chains, preventing accurate modeling of multimeric enzymes and polymeric protein assemblies where catalytic function often depends on quaternary structure [15]. This represents a significant limitation given that many biologically and industrially relevant enzymes function as complexes.

CAPIM addresses this limitation by supporting analysis of any number of peptide chains in protein complexes [15]. This capability is crucial for enzymes whose functions depend on quaternary structures, including many amylases, proteases, and metabolic enzymes. Tools limited to single-chain analysis cannot capture the complex interplay between subunits that often defines enzymatic mechanism and regulation.

Challenges in Predicting Temperature-Dependent Enzyme Activity

Enzyme activity exhibits complex, nonlinear relationships with temperature, presenting a significant challenge for purely in silico methods. A three-module ML framework developed specifically for β-glucosidase highlights both the potential and limitations of computational approaches in this domain [17].

Table 2: Performance of Machine Learning Models in Predicting Enzyme Kinetic Parameters

| ML Model | Enzyme | Predicted Parameter | Performance (R²) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Three-module ML framework | β-glucosidase | kcat/Km vs temperature | ~0.38 (unseen sequences) | Requires enzyme-specific training data |

| EF-UniKP | Various | Temperature-dependent kcat | 0.31 (novel sequences/substrates) | Poor generalization to new sequences |

| EITLEM-Kinetics | Various | kcat/Km | 0.519-0.680 | Requires large datasets; transfer learning complexity |

| CataPro | Various | kcat/Km | PCC: 0.41 | Limited accuracy for practical applications |

While the three-module framework successfully predicted optimum temperature (Topt), kcat/Km at Topt (kcat/Km,max), and relative kcat/Km profiles for β-glucosidase, it achieved only moderate performance (R² ~0.38) when predicting temperature-dependent activity for sequences not encountered during training [17]. This demonstrates the fundamental challenge of creating generalizable models for catalytic function prediction, particularly when incorporating environmental variables like temperature.

Case Study: Experimental Validation Reveals Critical Gaps in Computational Predictions

Machine Learning-Driven Substrate Identification for SET8 Methyltransferase

A compelling example of the limitations of purely in silico methods comes from research on the methyltransferase SET8. Researchers developed a hybrid ML approach that combined in vitro peptide array experiments with machine learning to identify novel substrates [12].

Experimental Protocol:

- Peptide Array Generation: Synthesized an array of peptides representing permutation motifs based on the known H4-K20 substrate sequence (GGAXXXXKXXXXNIQ) with mutations ±4 amino acids around the central lysine.

- Enzyme Incubation: Exposed arrays to active SET8 construct (residues 193-352).

- Activity Quantification: Measured methylation activity through relative densitometry.

- Motif Generation: Used PeSA2.0 software to generate a substrate recognition motif.

- Proteome Screening: Applied the motif to search the known methyl-lysine proteome.

- Experimental Validation: Tested candidate substrates using peptide arrays and SET8 construct.

The results were telling: the computational motif search identified 346 candidate substrate hits, but subsequent experimental validation confirmed only 26 of these as genuine SET8 substrates—a validation rate of just 7.5% [12]. This dramatic attrition rate underscores the risk of relying solely on computational predictions without experimental confirmation.

Allosteric Inhibition Mechanism of SauCas9 Revealed Through Integrated Approaches

Research on the allosteric inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus Cas9 (SauCas9) by AcrIIA14 protein further demonstrates the necessity of combining computational and experimental methods. Initial computational analysis suggested a straightforward competitive inhibition mechanism, but integrated investigation revealed a far more complex allosteric process [16].

Experimental Protocol:

- Molecular Dynamics Simulations: Conducted all-atom MD simulations of eight SauCas9 complex systems.

- Markov State Models: Built MSMs to characterize conformational states.

- Community Network Analysis: Identified allosteric pathways and communication networks.

- Site-Directed Mutagenesis: Introduced mutations in REC, L1, L2, and PI domains.

- Enzyme Activity Assays: Measured catalytic activity of mutant proteins.

- Surface Plasmon Resonance: Quantified binding affinities and kinetics.

The integrated approach revealed that AcrIIA14 suppresses SauCas9 activity by modulating dynamic interactions among REC, L1, L2, and PI domains—a long-range allosteric mechanism that would not have been identified through purely computational or purely experimental approaches alone [16]. Mutations in key residues (K485G/K489G/R617G) disrupted domain interactions and abolished allosteric inhibition, confirming the computational predictions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Enzyme Activity Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application | Specific Use Case | Validation Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peptide Arrays | High-throughput substrate screening | SET8 methyltransferase substrate identification [12] | Confirm genuine substrates among candidates |

| AutoDock Vina | Molecular docking and binding affinity prediction | CAPIM pipeline for substrate-enzyme interaction validation [15] | Experimental affinity measurements |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Studying conformational dynamics and allostery | SauCas9-AcrIIA14 allosteric mechanism [16] | Mutagenesis and functional assays |

| P2Rank | Machine learning-based binding pocket prediction | Structural annotation in CAPIM pipeline [15] | Comparison with experimental structures |

| GASS | Active site identification and EC number assignment | Functional annotation in CAPIM [15] | Catalytic residue validation |

| Markov State Models | Characterizing conformational ensembles | Allosteric pathways in SauCas9 [16] | Experimental kinetic measurements |

| SOLVE | EC number prediction from sequence | Enzyme function annotation [2] | Distinguishing enzymes from non-enzymes |

This case study demonstrates that while purely in silico prediction methods provide valuable starting points for enzyme research, they face fundamental limitations in accuracy, context, and biological relevance. The integration gap between activity prediction and structural annotation, overreliance on sequence-based information, inability to model complex multimeric systems, and challenges in predicting environmental dependencies all contribute to the need for experimental validation.

The most robust research approaches strategically combine computational predictions with experimental validation, using each method to inform and refine the other. As machine learning continues to advance, the most successful research programs will be those that maintain this integrated perspective, leveraging computational efficiency while respecting the complex biophysical reality of enzymatic function that can only be fully captured through experimental investigation.

Researchers should view computational predictions as powerful hypotheses-generating tools rather than definitive answers, recognizing that even the most sophisticated algorithms cannot yet fully capture the intricate dance of atoms, bonds, and energies that defines enzymatic catalysis. The future of enzyme research lies not in choosing between computational and experimental approaches, but in skillfully integrating them to accelerate discovery while maintaining scientific rigor.

Hybrid Approaches: Integrating ML with High-Throughput Experimental Validation

In the field of enzymology, a central challenge remains the accurate identification of enzyme-substrate relationships, particularly for enzymes that introduce or remove post-translational modifications (PTMs). Identifying genuine PTM sites amid numerous candidates is complex and resource-intensive [12]. Traditional methods, including peptide arrays and mass spectrometry, while valuable, come with inherent limitations and biases, often making the process slow and costly [12] [18]. Machine learning (ML) offers a promising path forward, but models trained solely on existing databases can perform poorly due to limited or low-quality data [12] [19].

The "ML-Hybrid" framework represents a paradigm shift, transcending these traditional techniques by integrating high-throughput experimental data generation with machine learning modeling [12]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of this framework against other methodological approaches, underpinned by experimental data and protocols, to serve researchers and drug development professionals focused on validating machine learning predictions in enzyme activity research.

The core innovation of the ML-Hybrid framework is its cyclical workflow that connects wet-lab experiments with dry-lab computational modeling to create enzyme-specific predictors. Unlike purely in silico methods, it begins with the experimental generation of enzyme-specific training data using peptide arrays that represent a vast segment of the PTM proteome [12]. This experimental data then trains a machine learning model, whose predictions can be validated in cell models, ultimately refining our understanding of enzyme-substrate networks [12].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated, multi-stage process of the ML-Hybrid framework:

Comparative Analysis: ML-Hybrid vs. Alternative Methodologies

To objectively evaluate the ML-Hybrid framework's performance, we compare it against other established approaches using quantitative experimental data. The following table summarizes the key performance metrics across different methods.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Methods for Identifying Enzyme Substrates

| Methodology | Key Principle | Reported Validation Rate | Throughput | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-Hybrid Framework [12] | Integration of peptide array data with ensemble ML modeling | 37-43% (SET8, SIRT1-7) | High | High predictive accuracy; generates testable hypotheses; reveals disease-related networks | Requires initial experimental work; complex workflow |

| Traditional In Vitro Methods [12] | Peptide array screening without ML integration | Low (Precision not specified) | Medium | Direct experimental evidence; simple setup | Lower precision; high false discovery rate; misses complex motifs |

| Purely In Silico ML Prediction [12] [19] | ML models trained on existing databases | Varies; can be error-prone (see Section 5) | Very High | Rapid; low cost; scalable | High risk of data leakage/errors; depends on database quality |

| Three-Module ML Framework [17] | Separate ML modules for enzyme kinetic parameters (e.g., kcat/Km) | R² ~0.38 for kcat/Km prediction (β-glucosidase) | High | Predicts quantitative kinetic parameters; models temperature dependence | Specialized for kinetic parameters, not substrate identification |

The data shows that the ML-Hybrid framework marks a significant performance increase, with a reported 37-43% of its proposed PTM sites being experimentally confirmed for enzymes like the methyltransferase SET8 and the deacetylases SIRT1-7 [12]. This performance is notably higher than that of traditional in vitro methods across separate enzyme classes.

Key Differentiators of the ML-Hybrid Approach

- Performance in Cellular Models: The ensemble models unique to each enzyme demonstrate enhanced predictive accuracy when validated in cell models, successfully confirming the dynamic methylation status of SET8 substrates and the deacetylation of 64 unique sites for SIRT2 [12].

- Disease-Relevant Insights: A significant advantage is the framework's ability to reveal changes in enzyme-substrate networks under disease conditions. For instance, it identified alterations in the SET8-regulated substrate network among breast cancer missense mutations [12].

- Applicability Across Enzyme Classes: The framework's utility has been demonstrated across different enzyme classes, including lysine methyltransferases (e.g., SET8) and deacetylases (e.g., SIRT1-7), indicating its potential broad applicability [12].

Experimental Protocols & Validation

Core Experimental Protocol: Peptide Array Screening and ML Integration

The following diagram details the core experimental protocol for generating training data, a foundational step in the ML-Hybrid framework.

Detailed Protocol:

- Peptide Array Design and Synthesis: Chemically synthesize peptide arrays representing a substantial portion of the PTM proteome. For instance, one approach is to create permutation arrays based on well-characterized substrate sequences (e.g., the H4-K20 sequence for SET8: GGAXXXXKXXXXNIQ, where X is mutated ±4 amino acids around the central lysine) [12]. These arrays are typically synthesized using standard SPOT synthesis techniques.

- Enzyme Expression and Purification: Express and purify a catalytically active construct of the enzyme of interest (e.g., the SET8193-352 construct) [12]. Confirm enzymatic activity using a canonical substrate peptide in a preliminary assay.

- Array Probing and Incubation: Incubate the synthesized peptide arrays with the active enzyme in the presence of necessary cofactors (e.g., S-adenosylmethionine for methyltransferases or NAD+ for deacetylases like sirtuins) under optimized buffer and temperature conditions [12].

- Signal Detection and Quantification: Detect the introduced PTMs using specific antibodies conjugated to a fluorescent or chemiluminescent reporter, or via other methods like autoradiography if a radioactive cofactor is used. Quantify the signal intensity for each peptide spot using densitometry. The resulting data is a list of peptide sequences with associated quantitative reactivity values [12].

- Data Pre-processing for ML Training: Format the data for machine learning. The amino acid sequences are converted into feature vectors (e.g., using physicochemical properties, one-hot encoding, or more advanced embeddings), and the quantified reactivity values serve as the regression target or classification label [12] [20].

Validation Workflow: From Prediction to Biological Insight

Predictions generated by the ML model must undergo rigorous validation to confirm their biological relevance.

- In Vitro Validation: Chemically synthesize the top-scoring candidate peptide substrates predicted by the model and validate their modification by the enzyme in solution-based assays, confirming the initial array results [12].

- Cellular Validation: Transfer the validation to a cellular context. This often involves mass spectrometry analysis to confirm the dynamic modification status of the endogenous proteins harboring the predicted sites in cell models. For example, mass spectrometry confirmed the deacetylation of 64 unique sites identified for SIRT2 and the methylation of several predicted SET8 substrates within cells [12].

- Functional and Mechanistic Studies: For high-priority substrates, further investigations can include Western blot analysis to monitor pathway activation (e.g., the Nrf2/Keap-1/HO-1/NQO1 pathway in oxidative stress responses [18]) or gene knockdown/overexpression experiments to determine the functional consequences of the PTM in specific disease contexts, such as breast cancer [12].

Critical Considerations for ML in Enzyme Research

The application of machine learning in enzyme research, while powerful, requires careful consideration to avoid significant pitfalls. A case study involving a transformer model published in Nature Communications highlights critical risks. The model, trained on UniProt data to predict enzyme function, made hundreds of "novel" predictions that were later found to be erroneous upon deep domain expertise review [19].

These errors included:

- Biologically Implausible Predictions: Predicting functions, like mycothiol synthesis in E. coli, for pathways that do not exist in that organism [19].

- Ignoring Established Literature: Contradicting prior in vivo evidence, such as predicting a function for the gene yciO that had already been experimentally refuted a decade earlier [19].

- Data Leakage and Repetition: 135 predictions were not novel but already listed in the training database, and 148 others showed implausibly high repetition of the same specific function [19].

This case underscores that supervised ML models are inherently limited in predicting "true unknown" functions, as they excel at propagating existing labels but struggle with genuine discovery [19]. It emphasizes the non-negotiable need for domain expertise throughout the process, from model training and data cleaning to the final interpretation of results. The ML-Hybrid framework mitigates some of these risks by generating its own high-quality, targeted experimental data for training, rather than relying solely on potentially noisy public databases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful implementation of the ML-Hybrid framework relies on a suite of specialized reagents and computational tools. The following table details these essential components.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for the ML-Hybrid Framework

| Category | Item | Specifications / Example | Primary Function in the Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Biochemicals | Peptide Array Library | Custom-synthesized; can represent specific proteomes or permutation motifs [12]. | High-throughput experimental platform for profiling enzyme substrate specificity. |

| Active Enzyme Construct | Purified, catalytically active fragment (e.g., SET8193-352) [12]. | Driver of the PTM reaction on the peptide arrays. | |

| Cofactors | S-adenosylmethionine (for methyltransferases), NAD+ (for deacetylases) [12]. | Essential molecular cofactor for enzymatic activity. | |

| Detection Reagents | Primary Antibody | Modification-specific (e.g., anti-mono-methyl-lysine, anti-acetyl-lysine). | Binds specifically to the PTM introduced by the enzyme. |

| Detection System | Fluorescent- or HRP-conjugated secondary antibody with compatible substrate. | Generates a quantifiable signal for PTM detection. | |

| Computational Tools | ML Framework | Python with scikit-learn, PyTorch, or TensorFlow for building ensemble models [21] [22]. | Engine for creating predictive models from experimental data. |

| Feature Extraction Tools | Algorithms to convert peptide sequences into numerical features (e.g., physicochemical properties) [20]. | Prepares experimental data for ML model training. | |

| Validation Assays | Synthetic Peptides | Custom-synthesized candidate peptides (>95% purity) [18]. | Validates top model predictions in vitro. |

| Cell Culture Models | Relevant cell lines (e.g., for cancer studies). | Provides a biological context for validating predictions. | |

| Mass Spectrometry | LC-MS/MS systems [12] [18]. | Confirms the existence of predicted PTMs on endogenous proteins in cells. |

The ML-Hybrid framework establishes a powerful new standard for predicting enzyme-substrate relationships by successfully marrying high-throughput experimental biochemistry with advanced machine learning. The quantitative data shows it achieves a substantially higher validation rate (37-43%) than conventional in vitro methods [12]. Its most significant advantage lies in its ability to generate accurate, testable hypotheses about enzyme function and reveal biologically relevant substrate networks in health and disease, as demonstrated in breast cancer models [12].

While purely in silico methods offer speed and scale, they carry a high risk of propagating database errors and making biologically implausible predictions without the critical integration of domain expertise [19]. The ML-Hybrid framework, though more resource-intensive initially, mitigates these risks by building models on targeted, high-quality experimental data. For researchers and drug developers focused on rigorously validating ML predictions for enzyme activity, this integrated approach provides a robust and reliable path to uncovering novel biology with high confidence.

Cell-Free Systems for Rapid Experimental Testing of ML Predictions

The integration of machine learning (ML) and cell-free systems is revolutionizing enzyme engineering by creating a powerful pipeline for validating computational predictions. ML models can navigate the vast sequence space to propose enzyme variants with desired activities, but these in silico predictions require experimental validation in a high-throughput, controlled environment [23]. Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) platforms have emerged as the indispensable experimental workbench for this task, enabling researchers to move directly from digital sequence designs to functional testing without the constraints of living cells [24]. This synergy is accelerating the design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycle, making it possible to rapidly prototype and optimize biocatalysts for pharmaceutical development and sustainable biomanufacturing [25] [24].

The fundamental advantage of cell-free systems lies in their openness and flexibility. Freed from the requirements to maintain cell viability and growth, these systems allow for precise manipulation of reaction conditions, direct observation of reaction kinetics, and expression of proteins that might be toxic to living hosts [26] [24]. This capability is critical for obtaining high-quality, quantitative data that either validates ML predictions or provides new datasets to refine and retrain models, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement for both computational and experimental approaches to enzyme engineering [23].

Comparative Analysis of ML-Guided Cell-Free Platforms

Recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of combining ML with cell-free systems across various enzyme engineering campaigns. The table below summarizes key platforms and their performance metrics.

Table 1: Comparison of ML-Guided Cell-Free Platforms for Enzyme Engineering

| Platform / Study | Enzyme Target | ML Approach | Cell-Free System Used | Key Performance Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ML-guided DBTL Platform [25] | Amide synthetases (McbA) | Augmented ridge regression | E. coli-based CFPS | 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity for 9 pharmaceutical compounds |

| KETCHUP Tool [27] | Formate dehydrogenase (FDH), 2,3-butanediol dehydrogenase (BDH) | Kinetic parameterization with Pyomo | Purified enzyme system | Accurate simulation of binary FDH-BDH cascade dynamics |

| Three-Module ML Framework [17] | β-Glucosidase (BGL) | Modular prediction of ( k{cat}/Km ) | Not specified (in vitro assays) | Achieved R² ~0.38 for predicting ( k{cat}/Km ) across temperatures and unseen sequences |

| EZSpecificity Model [3] | Halogenases | SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network | Validation with purified enzymes | 91.7% accuracy in identifying single reactive substrate |

Key Workflow and Experimental Protocol

The experimental workflow for validating ML predictions using cell-free systems typically follows a standardized, automated protocol.

Table 2: Standardized Experimental Protocol for ML Validation in Cell-Free Systems

| Step | Protocol Description | Key Reagents & Tools | Purpose & Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Design | ML models propose enzyme variant sequences based on training data. | Pre-trained models (e.g., Protein Language Models), sequence databases | Generate a library of target variant sequences for testing. |

| 2. Build | Cell-free DNA assembly and template preparation for high-throughput expression. | Linear expression templates (LETs), Gibson assembly reagents, cell-free lysates [25] | Create the DNA templates that code for the ML-predicted variants. |

| 3. Test | Express variants in a cell-free reaction and assay for function. | CFPS kits (e.g., E. coli S30 extract), energy systems, substrates, detection assays (e.g., MS, HPLC) [24] | Quantitatively measure the enzymatic activity of each variant. |

| 4. Learn | Experimental data is used to refine and retrain the ML model. | Data analysis pipelines, regression models | Improve the predictive accuracy of the model for the next DBTL cycle. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of cell-free validation pipelines relies on a core set of reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cell-Free Testing

| Reagent / Material | Function | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Free Expression System | Provides the transcriptional and translational machinery for protein synthesis. | E. coli S30 extract [24], wheat germ extract [24], reconstituted PURE system [27] [26] |

| Energy Regeneration System | Sustains ATP/GTP levels to power prolonged protein synthesis and catalysis. | Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) [24], creatine phosphate [24], maltodextrin [24] |

| DNA Template | Encodes the gene for the ML-predicted enzyme variant. | Linear expression templates (LETs) from PCR [25], plasmid DNA [24] |

| Cofactors & Substrates | Enable specific enzymatic reactions and functional assays. | NAD+, CoA [24], specific small molecule substrates for the target reaction [25] |

| Detection Assay | Quantifies the output of the enzymatic reaction (product formation). | Mass spectrometry (MS) [25], high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) [25] |

Visualizing the Integrated Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete, iterative cycle of ML-guided enzyme engineering enabled by cell-free systems.

Integrated ML and Cell-Free Validation Workflow

A critical phase within the "Test" module is the cell-free expression and characterization process, detailed below.

Cell-Free Testing Module

The fusion of machine learning prediction and cell-free experimental validation represents a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering. This synergistic approach provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful, objective framework to rapidly assess the functional outcomes of computational designs. The standardized workflows, quantitative data output, and accelerated DBTL cycles offered by integrated platforms are not only validating ML predictions but are also generating the high-quality datasets necessary to build more accurate and generalizable models for future biocatalyst development [23] [24]. As both computational and cell-free technologies continue to advance, their combined use is poised to become the standard for rigorous, high-throughput enzyme engineering in both academic and industrial settings.

Mass Spectrometry Verification of Predicted PTM Sites

The integration of machine learning (ML) into enzyme research has produced powerful predictive models for identifying post-translational modification (PTM) sites. However, the true value of these computational predictions depends entirely on rigorous experimental validation. Mass spectrometry (MS) has emerged as the cornerstone technology for this verification process, with various MS approaches offering distinct advantages and limitations for confirming predicted PTM sites. This guide objectively compares current MS methodologies, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to select optimal verification strategies for their specific enzyme activity research.

Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Approaches for PTM Verification

The following table compares the primary mass spectrometry methods used for PTM verification, highlighting their key characteristics and applications.

Table 1: Comparison of Mass Spectrometry Methods for PTM Site Verification

| Method | Key Principle | Suitable PTM Types | Throughput | Key Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bottom-Up MS | Analysis of proteolytically digested peptides | Phosphorylation, Acetylation, Glycosylation, Ubiquitination, Methylation [28] | High | Comprehensive PTM profiling across complex mixtures [28] | Loses correlation between PTMs on different peptides [29] |

| Top-Down MS | Analysis of intact proteins and their fragments | Complex PTM patterns, multiple modifications on single proteins [29] | Low | Preserves complete PTM patterning information [29] | Limited to smaller proteins; technical complexity [29] |

| PECAN Assay | Click chemistry + fluorophilic surface + NIMS | Enzyme activity on probe substrates (e.g., P450 oxidation) [30] | Very High | No chromatography needed; works in complex matrices [30] | Requires synthetic probe analog with "clickable" handle [30] |

| Native Top-Down MS (precisION) | Analysis of intact protein complexes under native conditions [31] | Phosphorylation, Glycosylation, Lipidation [31] | Medium | Preserves native structure and modification context [31] | Specialized instrumentation and data analysis required [31] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Bottom-Up MS with High-Quality Data (DeepMVP)

The DeepMVP framework exemplifies how bottom-up MS coupled with curated datasets achieves robust PTM verification [28].

Table 2: DeepMVP Experimental Workflow for PTM Validation

| Step | Protocol Details | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Preparation | PTM-enriched samples from biological sources; protein extraction and digestion | Use multiple proteases for better coverage; implement PTM-specific enrichment [28] |

| LC-MS/MS Analysis | Liquid chromatography tandem MS with high-resolution mass analyzers | 1% FDR threshold at both PSM and PTM site levels; localization probability >0.5 [28] |

| Data Processing | Systematic reanalysis of raw MS/MS data using standardized protocols | MaxQuant analysis; cross-dataset FDR control to reduce false identifications [28] |

| Model Training | Deep learning on PTMAtlas (397,524 high-confidence PTM sites) | CNN + bidirectional GRU architecture; genetic algorithm optimization [28] |

| Validation | Prediction of PTM probabilities for reference vs. variant sequences | Delta score calculation indicating increased or decreased modification likelihood [28] |

PECAN Assay for High-Throughput Enzyme Activity

The Probing Enzymes with 'Click'-Assisted NIMS (PECAN) technology provides an innovative approach for validating enzyme activity predictions without chromatographic separation [30].

Experimental Workflow:

- Enzyme Reaction: Incubate enzyme (e.g., P450BM3 lysate) with azide-containing probe substrate (0.5 mM in 1% DMSO) for 3 hours with cofactor regeneration system [30]

- Click Chemistry: Tag reaction products with perfluorinated alkyne via copper(I)-catalyzed azide-alkyne cycloaddition [30]

- Sample Deposition: Acoustically transfer samples onto NIMS surface [30]

- Washing and Analysis: Wash surface with water, then raster on MALDI-TOF mass spectrometer [30]

Performance Metrics: This approach achieved a Z-factor of 0.93, indicating an excellent assay for high-throughput screening, and successfully identified P450BM3 mutants capable of oxidizing valencene when screening 1,208 bacterial cell lysates [30].

Native Top-Down MS with PrecisION

The precisION workflow addresses the challenge of connecting PTMs to their structural and functional contexts in native protein complexes [31].

Experimental Protocol:

- Native MS Analysis: Intact protein complexes are introduced into the mass spectrometer under non-denaturing conditions [31]

- Gas-Phase Dissociation: Selected complexes are fragmented while preserving non-covalent interactions [31]

- Spectral Deconvolution: Modified Richardson-Lucy algorithm processes low signal-to-noise spectra [31]

- Envelope Classification: Machine learning-based supervised voting classifier filters artifactual isotopic envelopes [31]

- Hierarchical Assignment: Fragments are assigned through a priority system based on native fragmentation patterns [31]

- Fragment-Level Open Search: Discovers uncharacterized modifications without database dependency [31]

Validation: When applied to therapeutic targets including PDE6, ACE2, and GAT1, precisION discovered undocumented phosphorylation, glycosylation, and lipidation sites, resolving previously uninterpretable structural data [31].

Visualization of MS Verification Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between machine learning predictions and the appropriate mass spectrometry verification methods based on research goals:

PTM Verification Method Selection guides researchers to the optimal mass spectrometry approach based on their primary experimental goals.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for MS-Based PTM Verification

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PTMAtlas Database | Curated compendium of 397,524 high-confidence PTM sites for training/validation [28] | Benchmarking ML predictions; training deep learning models [28] |

| Perfluoroalkylated Tags | Fluorous affinity tags for NIMS surface attachment [30] | PECAN assays for high-throughput enzyme screening [30] |

| Click Chemistry Reagents | Copper(I) catalysts + azide/alkyne handles for bioorthogonal tagging [30] | Labeling enzyme products for sensitive MS detection [30] |

| DeepMVP Software | Deep learning framework predicting PTM sites and variant-induced alterations [28] | Computational prediction of PTM sites for experimental validation [28] |

| precisION Software | Open-source package for fragment-level open search in native top-down MS [31] | Discovering uncharacterized modifications in native protein complexes [31] |

Mass spectrometry provides an essential experimental foundation for validating machine learning predictions of PTM sites in enzyme research. Bottom-up approaches like DeepMVP offer the most comprehensive coverage for standard PTM verification, while specialized methods like PECAN enable unprecedented throughput for enzyme activity screening. For the critical task of connecting PTMs to their structural and functional consequences, native top-down MS with tools like precisION represents the cutting edge. The continued development of integrated computational-experimental workflows will further accelerate the validation of predictive models, ultimately enhancing our understanding of enzyme function and enabling more targeted therapeutic development.

EZSpecificity and Other AI Tools for Enzyme-Substrate Pairing

The validation of machine learning (ML) predictions is paramount for advancing enzyme activity research, bridging the gap between computational models and real-world biochemical applications. Tools like EZSpecificity are demonstrating how advanced algorithms, trained on comprehensive structural and sequence data, can achieve high experimental accuracy, offering researchers powerful new methods to decipher enzyme function [32] [3].

Direct Performance Comparison of AI Tools

Experimental data is crucial for validating the performance of predictive AI models. The following table summarizes a direct, head-to-head comparison between EZSpecificity and a leading existing model, ESP.

| AI Tool | Model Architecture | Key Input Features | Reported Top Prediction Accuracy (Halogenase Validation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity | Cross-attention SE(3)-equivariant Graph Neural Network (GNN) [3] | Enzyme sequence, 3D enzyme structure, substrate data, docking simulations [32] [33] | 91.7% [32] [14] [34] |

| ESP | Not Specified in Sources | Not Specified in Sources | 58.3% [32] [35] |

This comparative data, published in Nature, stems from a rigorous validation experiment involving eight halogenase enzymes and 78 substrates [3] [35]. The results demonstrate EZSpecificity's significant advantage in accurately identifying reactive pairs, a critical capability for researching poorly characterized enzyme families.

Experimental Validation & Methodology

A core thesis in modern enzymology is that robust experimental validation is what separates promising algorithms from reliable research tools. The protocol used to validate EZSpecificity provides a template for the field.

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Model Validation

Researchers conducted a clear, multi-stage validation experiment [32] [33]:

- Enzyme and Substrate Selection: Eight halogenase enzymes were selected for validation. This class is increasingly used to create bioactive molecules but remains poorly characterized, making it an ideal test case for a generalizable model [35] [34].

- Prediction Generation: The EZSpecificity model was used to predict the most reactive substrate for each of the eight halogenases from a pool of 78 candidate substrates.

- Experimental Testing: The top enzyme-substrate pairing predictions were tested in the laboratory to confirm actual reactivity.

- Accuracy Calculation: Model performance was quantified by calculating the percentage of top predictions that were experimentally confirmed as correct, yielding the 91.7% accuracy rate.

This workflow underscores the critical "test-in-the-lab" step required to validate any "predict-on-computer" model.

How EZSpecificity Works: Architecture & Workflow

EZSpecificity's performance stems from its sophisticated architecture and the quality of its training data, which directly address the complexity of enzyme-substrate interactions.

The model is a cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network [3]. This architecture allows it to effectively process and integrate the 3D structural information of the enzyme's active site with the chemical structure of the substrate. The "induced fit" model of enzyme action—where both the enzyme and substrate adjust their conformations upon binding—makes this 3D structural understanding critical [32] [14].

The development team significantly improved the model's training data by partnering with a computational group that performed millions of docking simulations [35] [34]. These simulations zoomed in on atomic-level interactions, creating a massive database of how different enzyme classes conform around various substrates and providing the missing puzzle pieces for a highly accurate predictor [32] [33].

Building and validating tools like EZSpecificity relies on a foundation of specific data types and computational resources.

| Resource / Reagent | Function in Research / Model Development |

|---|---|

| Docking Simulations | Computational experiments that predict the atomic-level interaction and binding conformation between an enzyme and a substrate, used to generate massive training data [32] [33]. |

| Enzyme Sequence (e.g., from UniProt) | The amino acid sequence of the enzyme provides fundamental data for the model and helps link predictions to known protein databases [3] [5]. |

| 3D Structural Data (e.g., from PDB) | Information on the three-dimensional structure of the enzyme's active site is critical for the GNN to understand spatial and chemical complementarity [3] [5]. |

| Halogenase Enzymes | A class of enzymes used as a experimental test case for model validation due to their relevance in synthesizing bioactive molecules and previously incomplete characterization [35] [34]. |

| Experimental Kinetic Data | Quantitative parameters (e.g., kcat, Km) extracted from literature by tools like EnzyExtract are essential for training and benchmarking predictive models of enzyme kinetics [36]. |

Future Directions in AI-Driven Enzymology