Harnessing Electric Fields for Next-Generation Enzyme Design: From Electrostatic Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article explores the critical role of optimizing intrinsic electric fields for the design of efficient artificial enzymes.

Harnessing Electric Fields for Next-Generation Enzyme Design: From Electrostatic Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article explores the critical role of optimizing intrinsic electric fields for the design of efficient artificial enzymes. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it provides a comprehensive examination of how electrostatic preorganization, a key strategy used by natural enzymes, can be leveraged to overcome the catalytic limitations of current designed enzymes. We cover the foundational theory, advanced computational and experimental methodologies for field analysis and design, troubleshooting of common pitfalls, and validation through case studies and comparative performance metrics. The synthesis of these areas highlights a paradigm shift from random exploration to rational design, offering a roadmap to create highly active and specific biocatalysts with significant potential for biomedical innovation.

The Principles of Electrostatic Preorganization: How Natural Enzymes Harness Electric Fields for Catalysis

FAQ: Core Principles of Electrostatic Preorganization

What is electrostatic preorganization and why is it crucial for enzyme catalysis?

Electrostatic preorganization is a fundamental concept explaining enzymes' immense catalytic power. Pioneered by Warshel, it proposes that enzyme active sites are preorganized with an optimal electric field that permanently favors the reaction's transition state over the reactants [1]. Unlike in solution, where solvent molecules must reorganize at a significant energetic cost to stabilize charge redistribution during reactions, the enzyme's scaffold—with its precisely oriented permanent dipoles and charges—is already preorganized to provide this stabilization without major rearrangement [1] [2]. This preorganization lowers both the enthalpy and entropy components of the free energy barrier, leading to dramatic rate accelerations [1] [3].

Is catalysis due to stronger enzyme-transition state interactions or preorganization?

A common misunderstanding is that enzymes catalyze reactions solely through stronger interaction energy with the transition state. The preorganization concept clarifies that the interaction energy between the environment and the transition state can be similar in enzymes and in solution [2]. The key difference is the reorganization energy. In water, solvent molecules pay a large reorganization free energy to reorient and stabilize the transition state. In the preorganized enzyme active site, the catalytic groups are already optimally oriented, minimizing this reorganization penalty [2]. Thus, catalysis arises not from stronger interactions per se, but from the enzyme's preorganized architecture that provides those interactions without the energetic cost of reorganization.

How does electrostatic preorganization differ from "substrate preorganization" or strain concepts?

Electrostatic preorganization is a distinct concept from traditional ideas like substrate strain or substrate preorganization into a "near-attack conformation." Electrostatic preorganization specifically refers to the preorganization of the enzyme's own electric field, created by its polar groups and dipoles throughout the protein scaffold, to stabilize the charge redistribution occurring during the chemical reaction step [1] [2]. Proposals that attribute catalytic power primarily to the preorganization of the substrate itself have been challenged by studies showing that without the preorganized protein environment, achieving significant catalysis is extremely difficult [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Computational Analysis of Electrostatic Preorganization

Problem 1: Inaccurate Electrostatic Models in Simulations

- Problem Description: Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations using standard, non-polarizable force fields (e.g., Amber ff14SB, CHARMM C36m) fail to reproduce the quantum mechanical picture of electric fields inside enzyme active sites [1]. This leads to incorrect predictions of catalytic efficiency and the effects of mutations.

- Recommended Protocols:

- Utilize Polarizable Force Fields: Employ advanced force fields like AMOEBA, which incorporate terms to account for asymmetric electronic distribution around nuclei, providing a more accurate description of electrostatics [1].

- Implement Titratable Residues: Use software that allows protonation states of residues to change during simulation, as fixed protonation states can provide an inaccurate representation of the electrostatic environment, especially for residues with pKa's near physiological pH [1].

- Proper Long-Range Electrostatics: Ensure long-range electrostatic interactions are correctly handled in simulations, for example, using Particle Mesh Ewald summation methods with appropriate cutoffs [1].

Problem 2: Difficulty Quantifying and Comparing Preorganization

- Problem Description: The electric field within an enzyme is a complex, heterogeneous 3D vector field. Simply projecting it onto a single reaction axis or analyzing it at a few discrete points may not capture its full catalytic effect, leading to an incomplete understanding [1] [4].

- Recommended Protocols:

- Analyze Electron Density Topology: Use the geometry and topology of the electron charge density in the active site as a quantitative descriptor. Features like the electrostatic potential and electron density at bond critical points converge with increasing protein model size and correlate with reaction barriers [4].

- Compare Global Field Line Distributions: Instead of comparing fields at points, compare the global topology and distribution of electric field lines around the relevant reacting bonds. Topologically similar electric fields have been shown to correspond to similar reaction barriers in studies of ketosteroid isomerase and Diels-Alder reactions [1].

Problem 3: Poor Catalytic Efficiency in Computationally Designed Enzymes

- Problem Description: De novo computationally designed enzymes often have catalytic efficiencies (

kcat/KM) orders of magnitude lower than natural enzymes. A major factor is the failure of current design protocols to adequately incorporate long-range electrostatic preorganization [1] [3]. - Recommended Protocols:

- Inverse Design of Electric Fields: Tackle the "inverse design problem" by first determining the optimal electric field for accelerating your target reaction. Subsequently, search the vast sequence space for a protein scaffold that can generate this field [1] [3].

- Incorporate Preorganization Metrics in Screening: Use ground-state charge density and electric field topology descriptors as screening tools during the design process. These continuous, information-rich descriptors can help predict the effects of mutations on reactivity without costly transition-state calculations and are suitable for machine learning approaches [1].

Experimental Data and Metrics

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters from Preorganization Studies

| System / Parameter | Value | Interpretation | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| HG3 Kemp Eliminase (Computational Design) | kcat/KM ≈ 430 M-1s-1 |

Low efficiency, missing preorganization [1] | [1] |

| HG317 (After Directed Evolution) | kcat/KM ≈ 230,000 M-1s-1 |

Evolution likely optimized preorganization [1] | [1] |

| Natural Enzyme Efficiency | kcat/KM ~ 105 M-1s-1 |

Benchmark for efficient catalysis [1] | [1] |

| UDP-glucuronic acid 4-epimerase | -TΔS‡ = 20 kJ/mol (298 K) |

Significant entropy loss, implies configurational restriction to reach reactive state [5] | [5] |

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Electrostatic Analysis

| Reagent / Tool Category | Specific Example | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Polarizable Force Fields | AMOEBA force field [1] | Provides a more accurate quantum-mechanically informed description of electrostatics in molecular dynamics simulations compared to standard fixed-charge force fields. |

| MD Software with Titration | pi-DMD software [1] | Allows protonation states of residues to change during dynamics, critical for modeling the true electrostatic environment, particularly for catalytic residues. |

| Electron Density Analysis | QM/MM Charge Density Topology [4] | Uses the geometry of the electron charge density in the active site (e.g., at bond critical points) as a rigorous metric to quantify electrostatic preorganization effects. |

| Modeling Ions & Modifications | Explicit ion/post-translational modification modeling | Accounts for the influence of solution ions and covalent protein modifications on the active site's electric field, effects often overlooked. |

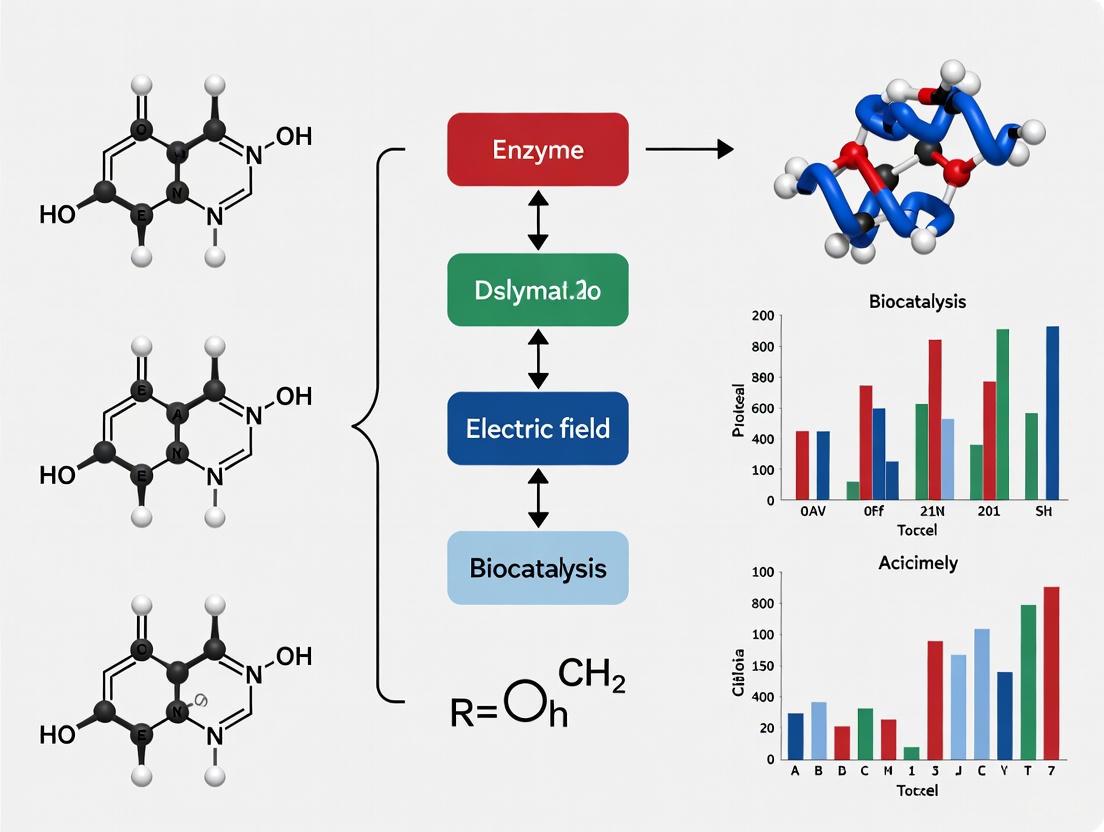

Conceptual Workflow: From Theory to Design

The following diagram outlines the logical relationship between the core theory of electrostatic preorganization and the modern approaches for its analysis and application in enzyme design.

KSI Troubleshooting FAQs

What are the common issues when studying KSI catalysis and their solutions?

Problem: Inconsistent or lower-than-expected reaction rates.

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Active site residue protonation state: The catalytic efficiency of KSI is highly dependent on the precise protonation states of Asp-38 (general base) and Tyr-14/Tyr-16 (part of the oxyanion hole). Ensure reaction buffer pH is optimized for the specific KSI homolog (typically around pH 7) [6] [7].

- Disruption of the oxyanion hole: Mutations or conditions that disrupt the hydrogen-bonding network of the oxyanion hole (e.g., Asp-99/103, Tyr-14/16) drastically reduce activity. Check enzyme construct and purity [8] [6].

- Incorrect intermediate stabilization: The reaction proceeds through a dienolate intermediate. Using analogues like 4-fluorophenol can help probe and validate the intermediate stabilization capability of your enzyme preparation [6].

Problem: Discrepancies in determining the catalytic mechanism (dienol vs. dienolate intermediate).

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Indirect measurement methods: Use direct spectroscopic methods to probe the ionization state of the intermediate. FTIR spectroscopy with specifically designed inhibitor probes (e.g., 4-fluorophenol) can report directly and quantitatively on the ionization state of the ligand bound in the active site [6].

- Interpretation of mutational data: The energetic contributions of catalytic residues can be additive rather than synergistic. Perform detailed thermodynamic cycle analysis to discriminate between concerted and stepwise proton transfer mechanisms [6].

Problem: Difficulty quantifying the contribution of electric fields to catalysis.

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Complex native system: The native enzyme's complexity makes it difficult to isolate the effect of electric fields from other catalytic strategies. Use supramolecular enzyme mimics with strategically placed charged groups to create and measure local, oriented electric fields. Stark spectroscopy can be employed to quantify these electric fields [6] [9].

How can I optimize experimental conditions for enzyme inhibition studies like those relevant to drug development?

Problem: Inaccurate or imprecise estimation of inhibition constants (Kic and Kiu).

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Inefficient experimental design: Traditional designs using multiple substrate and inhibitor concentrations can introduce bias and are inefficient. Adopt the 50-BOA (IC50-Based Optimal Approach), which requires initial velocity data obtained using a single inhibitor concentration greater than the IC50. This method incorporates the harmonic mean relationship between IC50 and the inhibition constants into the fitting process, reducing the number of experiments by over 75% while improving precision [10].

- Uncertain inhibition type: Using the mixed inhibition model (which applies to all types) without prior knowledge can lead to false reporting. The 50-BOA approach allows for precise estimation without prior knowledge of the inhibition type [10].

Problem: Inconsistencies between in vitro and predicted in vivo enzyme inhibition.

- Possible Cause & Solution:

- Non-optimized in vitro conditions: Use well-characterized experimental systems (e.g., hepatocytes or microsomes) and correct kinetic parameters for nonspecific binding. For Ki or IC50 determinations, use initial product formation rates with less than 20% substrate depletion to avoid artefacts like product inhibition [11].

- Ignoring time-dependent inhibition: Routinely screen for time-dependent (irreversible) inhibition during drug development, as this is a major clinical concern that can lead to drug withdrawal [11].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Estimating Inhibition Constants Using the 50-BOA Method

This protocol enables precise and accurate estimation of enzyme inhibition constants with a minimal experimental dataset [10].

Determine IC50:

- Perform a preliminary experiment by measuring the initial reaction velocity (V₀) over a range of inhibitor concentrations ([I]) at a single substrate concentration, typically [S] = Kₘ.

- Fit the % control activity data to a log(inhibitor) vs. response model to calculate the IC₅₀ value.

Set Up the Optimal Experiment:

- Measure initial velocities using a single inhibitor concentration [I] > IC₅₀.

- Vary the substrate concentration across at least three values (e.g., 0.2Kₘ, Kₘ, and 5Kₘ) to adequately define the enzyme kinetics.

Data Fitting and Analysis:

- Fit the collected initial velocity data to the mixed inhibition model using a software package that implements the 50-BOA (available for MATLAB and R).

- The model equation is: V₀ = (Vₘₐₓ * [S]) / ( Kₘ * (1 + [I]/Kᵢ𝒸) + [S] * (1 + [I]/Kᵢᵤ) )

- The fitting algorithm will incorporate the relationship between IC₅₀, Kᵢ𝒸, and Kᵢᵤ, providing precise estimates for both inhibition constants and identifying the inhibition type.

Protocol 2: Probing the Ionization State of an Intermediate in KSI using FTIR

This protocol uses IR spectroscopy to directly determine whether a reaction intermediate is neutral or charged, a key question in KSI catalysis [6].

Sample Preparation:

- Use a catalytically compromised mutant of KSI (e.g., Asp40Asn in the P. putida homolog) to trap the intermediate state.

- Prepare a solution of the mutant enzyme in an appropriate buffer (e.g., 50 mM phosphate, pD 7.0). Use D₂O-based buffers to avoid the strong IR absorption of H₂O.

- Titrate the enzyme with a intermediate analog, such as 4-fluorophenol (pKₐ = 10.0, matching the proposed dienol intermediate), which contains an intrinsic IR probe (C-F stretch).

FTIR Spectroscopy:

- Record IR spectra of the free enzyme, free ligand, and the enzyme-ligand complex.

- Focus on the spectral region corresponding to the C-F stretching vibration (around 1100-1300 cm⁻¹). The exact frequency is sensitive to the phenol's ionization state.

Data Analysis:

- Compare the C-F stretch frequency of the bound ligand to that of the neutral and ionized forms of the free ligand in solution.

- A frequency shift towards that of the ionized (phenolate) form indicates the ligand is deprotonated when bound to the active site.

- Quantitatively analyze the spectra to calculate the fraction of bound ligand that is ionized. This fractional ionization provides a direct measure of the free energy difference, informing the thermodynamic advantage of a concerted mechanism.

Key Data for Ketosteroid Isomerase (KSI)

Table 1: Wild-Type KSI Reaction Kinetics on 5-Androstenedione [8]

| Kinetic Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| kcat (s⁻¹) | 3.0 x 10⁴ |

| Km (μM) | 123 |

| kcat/Km (M⁻¹s⁻¹) | 2.4 x 10⁸ |

Table 2: Key Catalytic Residues in KSI Homologs [8]

| Residue Role | Comamonas testosteroni | Pseudomonas putida |

|---|---|---|

| General Acid/Base | Asp-38 | Asp-40 |

| Oxyanion H-Bond Donor | Asp-99, Tyr-14 | Asp-103, Tyr-16 |

Visualizing Mechanisms and Workflows

KSI Catalytic Mechanism and Electric Field

50-BOA Workflow for Efficient Inhibition Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for KSI and Enzyme Inhibition Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| KSI Homologs | Model enzyme for studying proton transfer & electrostatic catalysis. | Comamonas testosteroni (TI), Pseudomonas putida (PI) [8]. |

| Intermediate Analogs | Probe the ionization state and binding in the active site. | 4-Fluorophenol (pKₐ 10.0), Equilenin, 19-nortestosterone [6] [7]. |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kits | Generate catalytic mutants to dissect residue contributions. | Used to create D38N, Y14F, D99A/N mutants for mechanistic studies [6]. |

| IC50-Based Optimal Approach (50-BOA) | Software/Tool for precise inhibition constant estimation with minimal data. | User-friendly MATLAB and R packages are available [10]. |

| Methylation-Free E. coli Strains | Propagate plasmids for digestion when restriction sites are susceptible to methylation. | Use dam-/dcm- strains (e.g., E. coli GM2163) if methylation blocks cleavage [12] [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary catalytic strategies enzymes use to accelerate chemical reactions? Enzymes primarily utilize transition state stabilization (TSS) and the management of entropic advantages to achieve remarkable rate enhancements. TSS involves the preferential stabilization of the high-energy transition state structure through precise electrostatic interactions and other bonding interactions within the active site. The entropic advantage, or the "Circe effect," involves reducing the unfavorable entropy change required to reach the transition state by preorganizing substrates into reactive conformations and proximity [14].

Q2: How do electric fields contribute to transition state stabilization? The precise orientation of electric fields within an enzyme's active site creates a preorganized electrostatic environment that stabilizes the charge distribution of the transition state. This significantly lowers the activation energy required for the reaction. Recent studies using vibrational Stark effect spectroscopy have directly measured these fields, confirming their critical role in catalysis. The magnitude and direction of these fields differ considerably from those in common solvents, highlighting enzymatic optimization [14] [15].

Q3: What is the difference between ground state destabilization and transition state stabilization? Ground state destabilization (GSD) proposes that enzymes distort substrate bonds toward the transition state geometry, while TSS involves stronger binding to the transition state than to the ground state. The Circe effect is a more thermodynamically plausible form of GSD, where the enzyme selectively destabilizes the substrate's reactive region while maintaining favorable binding interactions with distal parts of the substrate [14].

Q4: Can external electric fields be used to mimic enzymatic catalysis in synthetic systems? Yes, emerging research demonstrates that oriented external electric fields (OEEFs) can catalyze chemical reactions in synthetic systems. For example, carbon nanotubes in microfluidic reactors can apply strong electric fields that influence reaction mechanisms, change rate-limiting steps, and even enable reactions that do not proceed without a field, offering a promising path for sustainable synthesis [16].

Q5: How are electric fields measured and mapped within enzyme active sites? Researchers use vibrational Stark effect (VSE) spectroscopy, which measures shifts in the vibrational frequencies of probe molecules bound to the active site. These shifts reveal the strength and orientation of the local electric field. Novel probes, like modified N-cyclohexylformamide, allow measurement of electric field magnitude and direction, providing a more complete picture of the active site electrostatic environment [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Electric Field Analysis in Enzyme Studies

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Table 1: Troubleshooting Electric Field and Catalysis Experiments

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inconclusive VSE data | Poor probe binding or orientation; inability to detect key vibrational modes [15]. | Use deuterium isotope exchange (e.g., C-H to C-D bonds) to access measurable vibrational frequencies; employ computational simulations to validate probe placement [15]. |

| Low catalytic activity in enzyme designs | Poorly preorganized electric field in the active site; suboptimal field orientation [14] [15]. | Use two-directional VSE probes to map field orientation; redesign active site residues to optimize the electrostatic environment for transition state stabilization [15]. |

| Difficulty quantifying electrostatic contributions | Overreliance on structural data; inability to separate electrostatic effects from other catalytic factors [14]. | Combine VSE experiments with Quantum Mechanical/Molecular Mechanical (QM/MM) calculations and conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT) analysis to correlate field strength with reactivity [17]. |

| External field experiments not yielding results | Incorrect field alignment with the reaction axis; insufficient field strength [16]. | Ensure the substrate is fixed and oriented relative to the field; use high-voltage sources and polarized nanotube surfaces to enhance field strength and control [16]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Mapping Electric Field Orientation with a Two-Directional Probe

This protocol is adapted from research to visualize the electric field in the active site of liver alcohol dehydrogenase [15].

1. Principle A probe molecule (N-cyclohexylformamide) is engineered with two chemical bonds approximately 120 degrees apart. The vibrational Stark effect on these bonds is measured to reconstruct both the magnitude and the orientation of the electric field within the active site.

2. Materials

- Purified enzyme (e.g., Liver Alcohol Dehydrogenase)

- N-cyclohexylformamide probe, synthesized with deuterium substitution at the critical C-H bond

- Appropriate buffer solutions

- Infrared spectrometer

- Computational resources for molecular simulations and quantum mechanical calculations

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Probe Binding. Incubate the deuterium-modified N-cyclohexylformamide probe with the enzyme, allowing it to bind tightly to the active site as an inhibitor.

- Step 2: IR Spectroscopy. Perform infrared spectroscopy on the enzyme-probe complex. Measure the vibrational frequency shifts of the carbon-deuterium (C-D) bond and another key bond (e.g., C=O) in the probe.

- Step 3: Data Analysis. The observed Stark shifts (in cm⁻¹) are proportional to the projection of the electric field onto the respective bond axes. Use the formula: Δν = -Δμ · E, where Δν is the frequency shift, Δμ is the difference in dipole moment, and E is the electric field.

- Step 4: Field Reconstruction. Using the two directional measurements, calculate the vector components of the electric field to determine its overall orientation within the active site.

- Step 5: Computational Validation. Compare experimental results with quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical (QM/MM) simulations of the enzyme-probe system to validate the findings.

Protocol 2: Analyzing Electrostatic Contributions in a Diels-Alderase

This protocol uses conceptual DFT and electric field analysis to unravel the electrostatic basis of catalysis in enzymes like AbyU [17].

1. Principle The reactivity of bound substrates is predicted by calculating atom-condensed Fukui functions, which describe regional susceptibility to electrophilic attack. This reactivity is then correlated with the electric field exerted by the enzyme on key reactive moieties.

2. Materials

- Enzyme-substrate structural data (from crystallography or docking)

- Computational software for QM/MM and conceptual DFT calculations

- Electric field analysis software

3. Procedure

- Step 1: Pose Generation. Generate multiple enzyme-substrate binding poses using molecular docking.

- Step 2: Fukui Function Calculation. For each pose, perform quantum mechanical calculations on the reactant to compute the Fukui function (ƒ⁻) for the key carbon atoms (e.g., the diene carbons in a Diels-Alder reaction).

- Step 3: Electric Field Calculation. For each pose, use QM/MM simulations to calculate the electric field vector projected along the critical reaction axis (e.g., the diene moiety).

- Step 4: Correlation Analysis. Correlate the calculated Fukui function values (reactivity descriptors) with the strength and alignment of the enzyme's electric field.

- Step 5: Mechanism Insight. Identify which poses have electric fields that best align to stabilize the transition state, explaining the enzyme's catalytic power and selectivity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Electric Field and Enzyme Catalysis Research

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Vibrational Stark Probe (e.g., N-cyclohexylformamide) | A small molecule inhibitor that binds the active site; its chemically engineered bonds serve as sensors for local electric fields via IR spectroscopy [15]. |

| Isotopically Labeled Compounds (e.g., Deuterated Bonds) | Used to modify probe molecules, making specific chemical bonds (like C-D) spectroscopically accessible for measurement in a protein environment [15]. |

| Polarized Nanotube Surfaces | Provide a platform in microfluidic reactors to apply strong, oriented external electric fields to chemical reactions, mimicking enzyme active sites [16]. |

| Conceptual DFT Descriptors (e.g., Fukui Functions) | Computational tools that predict the intrinsic reactivity of different atoms in a molecule based on electron density, helping to explain enzyme regioselectivity [17]. |

| QM/MM Software | Enables hybrid quantum mechanical and molecular mechanical simulations to model enzyme catalysis and calculate internal electric fields with atomic detail [17] [15]. |

FAQs: Understanding the Protein Scaffold and Long-Range Interactions

Q1: What is the functional role of the protein scaffold beyond providing a structural framework for the active site? The protein scaffold is not a passive structural element but plays an active role in catalysis. It facilitates the formation of conformational ensembles—numerous protein substates in rapid equilibrium—that are essential for function [18]. Through long-range interactions, the scaffold establishes thermally activated dynamical networks that connect the active site to the protein-water interface, acting as conduits for energy transfer and communication [18]. This allows the scaffold to influence the active site remotely.

Q2: How can remote mutations, far from the active site, significantly impact enzyme catalysis? Mutations in the protein scaffold can alter the distribution of conformational substates, shifting the population toward catalytically competent conformations [18]. This is often achieved through rigidification of the active site via improved packing, effectively pre-organizing the site for catalysis [18]. Furthermore, scaffold mutations can fine-tune intramolecular interactions that stabilize remote functional loops, which are critical for complex biological functions like accessing cellular targets [19].

Q3: What is the evidence that electric fields from the protein scaffold contribute to catalysis? Experimental studies using the vibrational Stark effect have provided direct measurements of the strong electric fields present within enzyme active sites [14]. These fields, generated by the precise three-dimensional arrangement of the protein scaffold, can stabilize the transition state of a reaction and are a major contributor to catalytic rate enhancement [14]. Computational designs like the AI.zymes platform successfully improve activity by iteratively selecting variants with stronger catalytic electric fields, demonstrating their importance [20].

Q4: How does the acquisition of remote loops during evolution lead to new enzyme functions? The acquisition of remote loops can grant enzymes access to new biological functions without disrupting the original catalytic activity [19]. For example, in GH19 chitinases, the acquisition of a specific remote loop (Loop II) was necessary for the emergence of antifungal activity [19]. This loop directly accesses the fungal cell wall, but its function depends on long-range interactions with the protein scaffold that restrict its mobility and stabilize a defined structure [19].

Troubleshooting Guide: Experimental Challenges in Analyzing Scaffold Function

| Problem | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or No Digestion | Catalytic activity blocked by DNA methylation. | Check the enzyme's sensitivity to Dam/Dcm/CpG methylation; propagate plasmid in a dam-/dcm- E. coli strain [21] [22]. |

| Unexpected Cleavage Patterns (Star Activity) | Altered enzyme specificity due to non-optimal conditions (e.g., high glycerol concentration, long incubation). | Ensure glycerol concentration is <5%; use the recommended reaction buffer; decrease incubation time and enzyme units; use High-Fidelity (HF) engineered enzymes [21] [22]. |

| Low Catalytic Efficiency in Designed Enzyme | Suboptimal conformational sampling; inactive substates are overly populated. | Use directed evolution to select for mutations that shift the conformational ensemble toward catalytically active populations, often by rigidifying the active site through improved packing [18]. |

| Difficulty in Resolving Small/ Flexible Protein Structures | Proteins smaller than ~40 kDa are difficult to visualize at high resolution with cryo-EM. | Utilize a double-shell protein scaffold technology that sandwiches the target protein to increase particle size and enable high-resolution structure determination [23]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction to Study Remote Loop Evolution

Objective: To identify key structural acquisitions and understand the evolutionary path by which a protein scaffold gains new functions.

Methodology:

- Sequence Collection and Phylogeny: Collect a comprehensive set of modern sequences for the enzyme family of interest. Perform multiple sequence alignment and infer a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree [19].

- Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction: Use statistical models to infer the most probable amino acid sequences at ancestral nodes of the phylogenetic tree [19].

- Gene Synthesis and Protein Expression: Synthesize genes coding for the reconstructed ancestral proteins, clone them into an expression vector, and express and purify the proteins [19].

- Functional Characterization: Measure both the core catalytic activity and the newly evolved function (e.g., antifungal activity) of the ancestral proteins and their engineered loop variants (e.g., loop insertions/deletions) [19].

- Structural and Dynamical Analysis: Solve high-resolution structures (e.g., via X-ray crystallography) and perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations to analyze structural differences and loop mobility, correlating them with the acquired function [19].

Protocol 2: Utilizing the Vibrational Stark Effect to Measure Active-Site Electric Fields

Objective: To experimentally measure the magnitude and direction of the intrinsic electric field within an enzyme's active site.

Methodology:

- Probe Incorporation: Introduce a covalent vibrational probe (e.g., a nitrile group) into the enzyme's active site, typically by chemically modifying a bound substrate or inhibitor [14].

- Infrared Spectroscopy: Obtain the infrared (IR) absorption spectrum of the vibrational probe when bound inside the enzyme.

- External Electric Field Application: Place the enzyme-probe complex in an external electric field and record the Stark spectrum, which shows the shift in the IR absorption band in response to the field [14].

- Calibration: Calibrate the vibrational probe's sensitivity to electric fields (its Stark tuning rate) in a known environment.

- Field Calculation: Use the measured Stark effect to calculate the electric field the enzyme exerts on the probe along the relevant reaction coordinate [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Tool | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Directed Evolution Platforms | A semi-rational approach to optimize enzyme properties, including those mediated by the scaffold, such as electric fields and conformational stability [20]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Used to visualize protein dynamics in real time and analyze the mobility and interactions of remote loops and dynamical networks [18] [19]. |

| Room-Temperature X-ray Crystallography | Allows for the detection of alternate protein side chain conformations and the inference of dynamical networks, providing a more dynamic view of the scaffold than traditional cryo-crystallography [18]. |

| Ancestral Sequence Reconstruction Algorithms | Computational tools to infer ancient protein sequences, enabling the experimental study of evolutionary trajectories and the functional impact of historical scaffold changes [19]. |

| Double-Shell Protein Scaffold | A technology using fusion proteins (e.g., apoferritin and MBP) to cage small, flexible proteins, enabling high-resolution structure determination via single-particle cryo-EM [23]. |

Conceptual Diagrams

Diagram 1: Enzyme Function via Scaffold Dynamics and Remote Loops

Diagram Title: Enzyme Function via Scaffold Dynamics and Remote Loops

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Evolutionary Analysis

Diagram Title: Workflow for Evolutionary Analysis of Scaffolds

Computational and Experimental Tools for Measuring and Designing Catalytic Electric Fields

Troubleshooting Guides

1. Unphysical Energies or Catastrophic Drift in QM/MM Dynamics

- Problem: During a QM/MM molecular dynamics simulation, the total energy behaves erratically or the structure drifts and becomes unphysical.

- Causes:

- Incorrect treatment of long-range electrostatics: Using a simple cutoff method for the QM-MM electrostatic interactions can introduce significant errors, as particles beyond 10-20 Å can still have non-negligible contributions to the energy and forces [24].

- Inadequate convergence of polarizable models: The shell model or Drude oscillator iterations may not have reached convergence, leading to unstable forces [25].

- Parameter mismatch: Van der Waals parameters at the QM/MM boundary, especially for custom-defined atoms, may be too repulsive or attractive [26].

- Solutions:

- Implement a long-range electrostatic correction (LREC) method. The LREC approach uses a smoothing function to scale electrostatic interactions, smoothly reducing them to zero at a finite cutoff. Studies show that energies and forces converge to within 0.2% of Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) results with a cutoff of 20–25 Å [24].

- For polarizable simulations, tighten the convergence criteria for the microiterations. In the

mm_polcosmethod, adjustpolcos_maxdx,polcos_rmsdx, andpolcos_toler_energy[25]. - Check and refine parameters for any user-defined MM atom types in the QM region using the

$force_field_paramssection, paying close attention to Lennard-Jones parameters [26].

2. Failure to Converge in Polarizable QM/MM SCF Calculations

- Problem: The self-consistent field (SCF) procedure for the QM region fails to converge when polarizable MM force fields are active.

- Causes:

- Strong electric field from polarized MM atoms: The induced dipoles or shells in the MM region create a strong, fluctuating electric field that the QM Hamiltonian cannot easily adapt to [25] [27].

- Overlapping atoms or poor initial geometry: This can cause excessively high initial forces from the MM region.

- Solutions:

- Use a two-step relaxation process: First, allow the MM polarizable sites (shells or Drude oscillators) to relax in the field of the initial QM electron density. Then, run the full mutual polarization cycle until self-consistency is achieved [25].

- Ensure the initial structure is well-minimized using a pure MM force field before starting the QM/MM calculation. Verify that no atoms are unnaturally close to each other.

3. Inaccurate Reaction Barriers in Enzyme Design

- Problem: Computed reaction barriers for a designed enzyme are inaccurate compared to experimental results, hindering the rational optimization of electric fields for catalysis [27] [28].

- Causes:

- Lack of electrostatic preorganization: The designed protein scaffold fails to generate the strong, oriented internal electric field necessary to stabilize the transition state [27].

- Neglect of long-range electrostatics: Truncating electrostatic interactions prevents an accurate description of the total electric field experienced by the substrate in the active site [24].

- Use of non-polarizable force fields: Standard mechanical embedding (e.g., ONIOM) does not allow the QM region's electron density to be polarized by the MM environment, missing a key catalytic effect [26].

- Solutions:

- Employ an electronic embedding scheme (e.g., the Janus model in Q-Chem) that includes the MM point charges directly in the QM Hamiltonian [26].

- Always use a robust long-range electrostatic treatment (like LREC or PME) in production calculations to ensure the electric field is properly modeled [24].

- Analyze the electric field in the active site using vibrational Stark effect proxies or by analyzing the QM electron density response to the protein environment [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between mechanical and electronic embedding in QM/MM?

- A: In mechanical embedding (e.g., ONIOM), the QM region is not polarized by the MM environment. The total energy is a combination of MM energies for the whole system and the QM region, and a QM energy for the QM region. Interactions between the subsystems are described only at the MM level [26]. In electronic embedding (e.g., the Janus model), the electrostatic potential from the MM point charges is included directly in the QM Hamiltonian. This allows the QM electron density to be polarized by the MM environment, providing a more physically accurate description, which is critical for modeling enzyme catalysis and optimizing electric fields [26].

Q2: When should I use a polarizable MM force field instead of a fixed-charge force field?

- A: You should consider polarizable force fields when:

- Your research focuses on accurately modeling electrostatic preorganization, a key strategy in natural enzyme catalysis [27].

- The system involves significant charge transfer or polarization effects, such as ions in channels or molecules with large dipole moments responding to a protein environment [25].

- You are studying interfaces between regions of high dielectric contrast, like a protein active site and a bulk solvent [24]. Fixed-charge force fields are computationally cheaper and may be sufficient for systems where polarization effects are less critical.

Q3: My simulation is computationally expensive. What is the most efficient way to handle long-range electrostatics in large QM/MM systems?

- A: The QM(LREC)/MM(PME) approach is an excellent compromise between simplicity, speed, and accuracy [24]. In this method:

- QM Region with LREC: The QM-MM electrostatic interactions are handled with the Long-Range Electrostatic Correction method, which converges with a cutoff of 20-25 Å and does not require modifications to the SCF routine [24].

- MM Region with PME: The much larger MM-MM interactions are treated with the highly efficient Particle Mesh Ewald method [24]. This combination avoids the computational cost of a full Ewald treatment for the QM region while maintaining accuracy.

Q4: How do I handle a covalent bond between the QM and MM regions?

- A: This is done using a "link atom" or a "capping atom." Most software offers automated solutions:

- Link Atoms: A hydrogen atom (link atom) is introduced to cap the valency of the QM atom at the boundary. The QM calculation is performed with the link atom, but its interactions are carefully handled to avoid double-counting [26].

- YinYang Atoms: In Q-Chem's Janus model, a single atom acts as a hydrogen cap in the QM calculation but retains its full MM identity for interactions within the MM subsystem. This maintains charge neutrality and improves performance [26].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Convergence Parameters for Polarizable QM/MM (polcos)

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Value | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

polcos_maxcycle |

Max outer QM/MM iterations [25] | 20 | Controls the number of mutual polarization cycles. |

polcos_inmaxcycle |

Max inner MM SCF iterations [25] | 1000 | Ensures Drude oscillators/shells converge for a fixed QM density. |

polcos_toler_energy |

QM energy change tolerance [25] | 1.0e-8 | Sets convergence based on energy change between outer cycles. |

polcos_maxdx |

Max change in massless charge position [25] | 2.0e-5 a.u. | Sets a force-based convergence criterion for the polarizable particles. |

Table 2: Comparison of Long-Range Electrostatic Methods

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simple Cutoff | Truncates interactions beyond a fixed distance. | Very fast and simple to implement. | Can introduce severe artifacts in energy and forces; not recommended for production runs [24]. |

| Ewald/PME | Sums interactions in both real and reciprocal space for periodic systems. | Highly accurate; standard for periodic MM. | Requires modifications to the SCF routine; can be complex to implement for QM/MM [24]. |

| LREC | Uses a smoothing function to scale interactions to zero at a cutoff. | Simple implementation; no SCF modifications; accurate with 20-25 Å cutoff [24]. | Less common than PME; requires parameterization of the cutoff distance. |

Detailed Protocol: Setting Up a Polarizable QM/MM Simulation in ChemShell

This protocol outlines the steps for a QM/MM calculation with a Drude polarizable force field, based on the mm_polcos method [25].

System Preparation:

- Obtain the initial protein structure (e.g., from a PDB file).

- Prepare the topology and parameter files for the CHARMM or GROMOS polarizable force field.

- Define the QM region (e.g., substrate and key active site residues) and the MM region.

Input File Configuration:

- In the ChemShell input script, specify the

theory=hybridblock. - Set

coupling=shift(or another electrostatic embedding scheme). - Activate polarizability with

mm_polcos=yesand provide a list of control arguments. - The

polcos_atom_polcosqlist must contain the atom ID, polarizability (in a.u.), and the charge (in a.u.) for each polarizable MM atom.

- In the ChemShell input script, specify the

Execution and Monitoring:

- Run the simulation and closely monitor the output log.

- Check for messages indicating convergence of both the QM SCF procedure and the

polcosmicroiterations. - Verify that the changes in energy and Drude oscillator positions (

polcos_maxdx,polcos_rmsdx) are below the specified thresholds.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Force Fields for Electrostatic-Focused QM/MM

| Item | Function in Research | Relevance to Electric Field Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| ChemShell | A QM/MM integration environment. | Supports advanced polarizable force fields (shell, Drude) and provides the mm_polcos method for mutual polarization, key for modeling environmental response [25]. |

| Q-Chem | A comprehensive quantum chemistry program. | Its stand-alone Janus model enables electronic embedding QM/MM, allowing the MM charge distribution to directly polarize the QM active site [26]. |

| LICHEM | A package for QM/MM simulations. | Implements the LREC method for accurate and efficient treatment of long-range electrostatics in multipolar/polarizable simulations [24]. |

| CHARMM Drude FF | A polarizable force field based on Drude oscillators. | Allows the MM environment to respond to the charge distribution of the QM region, creating a more realistic and responsive internal electric field [25]. |

| AMOEBA FF | A polarizable force field based on atomic multipoles. | Provides a more accurate description of the electrostatic potential around MM atoms, which is critical for calculating precise electric fields in an enzyme active site [24]. |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram Title: QM/MM Setup for Electric Field Optimization

Diagram Title: Polarizable QM/MM Self-Consistent Cycle

The Vibrational Stark Effect (VSE) describes the perturbation of a molecular vibrational frequency by an external electric field, forming the basis for Vibrational Stark Spectroscopy (VSS). This technique has become an indispensable tool for measuring and analyzing in situ electric field strength in diverse chemical environments, including the binding pockets of enzymes. The fundamental relationship is given by the Stark equation:

ν = ν₀ - Δμ⃗ · F⃗ + ½ F⃗ · Δα · F⃗

where ν and ν₀ are the vibrational frequencies with and without the electric field F⃗, respectively, Δμ⃗ is the difference dipole moment (Stark tuning rate), and Δα is the difference polarizability [29].

For the relatively weak electric fields typically encountered (below 100 MV/cm), the quadratic term can often be neglected, resulting in a linear relationship between the vibrational frequency shift and the electric field: Δν = ν - ν₀ ∝ Δμ⃗ · F⃗ [29]. This linear correlation provides the foundation for using VSE as a molecular ruler for electric fields in complex environments like proteins.

Key Assumptions and Theoretical Framework

The application of VSE rests on four critical assumptions that must be validated for reliable experimental results [29]:

- Bond Localization: The normal stretching vibration of the probe bond must be largely decoupled from the rest of the molecule.

- Electric Field Attribution: Frequency shifts from environmental changes can be fully attributed to the external electric field.

- Linearity: The difference dipole moment Δμ⃗ remains unaffected by the external electric field F⃗.

- Field Strength Extrapolation: The linear relationship observed at weak field strengths also holds for the much stronger fields present in enzyme active sites.

The most crucial of these is the first assumption regarding bond localization. Normal vibrational modes are typically delocalized due to mass coupling, meaning the target vibration can mix with other internal coordinates. If this occurs, the measured frequency shift no longer purely reports on the electric field at the target bond, compromising interpretation [29].

Evaluating Probe Bond Localization The Local Vibrational Mode Theory, specifically the Characterization of Normal Modes (CNM) procedure, quantitatively assesses how much a target normal vibration consists of pure bond stretching character. This method determines the degree to which the local stretching mode of the probe bond is decoupled from other local vibrational modes, providing a quantitative score to evaluate potential VSE probes [29].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Selecting and Validating a VSE Probe

The initial and most critical step is selecting an appropriate probe molecule. An ideal VSE probe exhibits a highly localized target bond vibration.

- Recommended Probe Molecules: Based on comprehensive local mode analysis of 68 candidates, 31 polyatomic molecules with localized target bonds are recommended as ideal VSE probes. The table below summarizes key validated probe types [29].

- Probe Validation: Before deployment in complex systems, validate the localization of your chosen probe's target vibration using computational chemistry methods. Perform a local mode analysis (e.g., using the CNM method) to calculate a localization score. Probes with low scores should be avoided as their frequency shifts will be difficult to interpret unambiguously [29].

Basic VSE Measurement Workflow

The following workflow outlines the core steps for a typical VSE experiment in a biochemical context.

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Probe Selection & Validation: Choose a probe from the recommended list (see Table 1). Confirm bond localization computationally if it is a novel candidate [29].

- Probe Incorporation: Introduce the probe into the protein system. This can be achieved by:

- Site-specific labeling of a native amino acid (e.g., using a cyanobenzothiazole probe to conjugate with a cysteine residue).

- Using a small molecule inhibitor or substrate analog that contains the probe bond (e.g., a carbonyl group).

- Incorporating a non-canonical amino acid bearing the probe bond directly into the protein sequence.

- Reference Spectrum Acquisition: Place the protein-probe system in its native environment (e.g., buffer, crystal, or membrane). Using FTIR or other IR spectroscopy methods, acquire a high-quality IR absorption spectrum of the target bond (e.g., C=O, C≡N) without any externally applied electric field. This provides the reference frequency, ν₀.

- Application of Electric Field: Apply a known, uniform external electric field to the sample. This is typically done using a custom-built electrochemical cell or a capacitor-like setup with transparent electrodes.

- Perturbed Spectrum Acquisition: Acquire a second IR spectrum under the exact same conditions but with the external electric field applied.

- Frequency Shift Measurement: Analyze the two spectra. Precisely measure the shift in the absorption peak of the target bond, Δν = ν - ν₀.

- Electric Field Calculation: Using the previously calibrated Stark tuning rate (Δμ⃗) for the probe, calculate the magnitude of the electric field projected along the bond's axis using the linear Stark equation: |F| ≈ |Δν| / |Δμ⃗|.

Calibrating the Stark Tuning Rate (Δμ⃗)

The Stark tuning rate (Δμ⃗) is a probe-specific constant that must be determined experimentally before the probe can be used as a quantitative ruler.

- Method: The probe molecule is placed in a series of inert solvents with known dielectric properties (or in a frozen glass) where it experiences different internal electric fields. The vibrational frequency of the probe bond is measured in each solvent. The slope of a plot of frequency (ν) versus the known electric field (F) yields the Stark tuning rate, Δμ⃗ [29].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ 1: My measured vibrational frequency shift is non-linear with the applied field. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause 1: Probe Delocalization. The normal mode of your target bond may not be fully localized, mixing with other vibrations.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your probe choice. Consult literature for probes with high localization scores [29]. computationally validate a new probe before use.

- Potential Cause 2: Strong Field Effects. The applied field might be too strong, making the quadratic term in the Stark equation significant.

- Solution: Reduce the applied field strength and confirm the linear response region for your specific probe.

- Potential Cause 3: Environmental Artifacts. Sample heating, electrode polarization, or molecular reorientation could be causing non-linear artifacts.

- Solution: Ensure temperature control, use short field pulses, and verify electrode stability.

FAQ 2: I observe an "anomalous" (negative) Stark shift in my system. How should I interpret this?

- Explanation: A negative Stark shift, where the frequency decreases with increasing field, was historically considered anomalous but has been observed in systems like CO on Pt(111) electrodes [30].

- Investigation Steps:

- Check for Phase Coexistence: High-resolution IR measurements may reveal that a single absorption peak is actually a doublet, indicating two slightly different molecular environments or adsorbate phases. The apparent negative shift can arise from fitting a single peak to a doublet feature where the two components have different intensities that change with potential or field [30].

- High-Resolution Scan: Perform a high-resolution spectral scan in the problematic region. Use peak-fitting software to deconvolute overlapping peaks.

- Control Experiment: If possible, run a control experiment under conditions known to produce a single, homogeneous phase.

FAQ 3: The signal-to-noise ratio for my VSE measurement is poor. How can I improve it?

- Solution A: Increase Probe Concentration. If feasible, increase the concentration of your labeled protein or probe molecule in the sample path.

- Solution B: Optimize Spectroscopy Settings. Increase the number of scans co-added during spectral acquisition. Use a higher optical aperture if signal-limited, while balancing resolution loss.

- Solution C: Check Sample Homogeneity. Ensure the sample is clear and free of precipitates or bubbles that cause light scattering.

Application in Enzyme Design and Optimization

VSE provides a direct experimental method to measure the pre-organized electric fields inside enzyme active sites, a key factor in catalytic efficiency. The measured electric fields can correlate with catalytic rates, providing a physical metric for designing artificial enzymes [31] [32].

Integrating VSE into the Enzyme Design Cycle: In enzyme design and directed evolution, VSE can be used to screen variants. By incorporating a VSE probe near the designed active site, you can measure whether a given mutation (even a distal one) creates an optimal electric field that stabilizes the reaction's transition state. This moves enzyme design beyond purely structural validation toward functional electrostatic validation [32].

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in VSE experiments.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents for VSE Experiments

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| VSE Probe Molecules | Reporter molecules containing a localized vibrational bond (e.g., C=O, C≡N, S=O) whose frequency shifts report on the electric field. | Recommended candidates from local mode analysis (e.g., 31 specific polyatomic molecules) [29]. |

| Site-Specific Labeling Kit | For covalently attaching VSE probes to specific sites in proteins (e.g., cysteine conjugation). | Commercially available kits (e.g., based on maleimide-cyanobenzothiazole chemistry). |

| IR-Transparent Windows | Windows for the sample cell that are transparent in the infrared region of interest. | CaF₂, BaF₂, or ZnSe windows, depending on spectral range and solubility. |

| Stark Cell / Electrochemical Cell | Sample holder capable of applying a uniform, known electric field across the sample. | Custom-built capacitor cells with electrode plates, or commercial electrochemical IR cells. |

| Transition-State Analogue | A stable molecule that mimics the geometry and charge distribution of a reaction's transition state. Used for pre-organizing the active site for measurement. | e.g., 6-Nitrobenzotriazole (6-NBT) for Kemp eliminases [32]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

Table 2: Summary of Common VSE Probe Bonds and Properties

| Probe Bond Type | Example Molecules | Typical Frequency Range (cm⁻¹) | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonyl (C=O) | Formaldehyde, Esters, Amides | 1650-1750 | Very common; can be incorporated into substrates or inhibitors. Potential for H-bonding complications. |

| Nitrile (C≡N) | Anisonitrile, Thiocyanates | 2200-2300 | Sharp IR band; minimally perturbing to biological systems. Stark tuning rate can be lower than C=O. |

| Sulfoxide (S=O) | Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | 1050-1100 | Strong dipole; useful for specific environments. |

| Carbon Monoxide (C≡O) | CO (as ligand in heme proteins) | 1900-2200 | Very strong Stark response; use is limited to specific metal-binding sites. |

FAQs: Computational Challenges in Inverse Design

Q1: What is the core objective of an inverse design protocol for electric field generation in enzymes?

The primary objective is to solve the inverse problem: designing a protein scaffold that produces a specific, preorganized electric field to optimally stabilize the transition state of a desired reaction. This involves computationally sampling the vast space of possible charge distributions around an active site to find the optimal arrangement that generates the electric field most beneficial for catalysis, rather than the traditional approach of designing an active site around a fixed chemical scaffold [1] [3].

Q2: Our design protocol consistently produces enzymes with catalytic efficiencies orders of magnitude lower than natural enzymes. What key factor might our computational models be missing?

Current computational design protocols often omit the optimization of long-range electrostatic interactions [1] [3]. The catalytic prowess of natural enzymes is largely derived from their electrostatic preorganization—the precise, fixed orientation of permanent dipoles within the enzyme scaffold that creates an electric field favoring the transition state. If your protocol focuses only on the immediate active site chemistry and does not explicitly optimize the electric field generated by the entire protein scaffold, the resulting designs will lack this critical catalytic driver [1].

Q3: What are the main computational bottlenecks in simulating and optimizing electric fields for enzyme design?

The main bottlenecks include:

- High Computational Cost: Modeling proteins with hundreds to thousands of atoms using high-level quantum mechanics is prohibitively expensive for the necessary sampling [1] [3].

- Force Field Accuracy: Standard molecular mechanics force fields (e.g., Amber ff14SB, Charmm C36m) can be inadequate for accurately reproducing the electric fields observed in quantum mechanical calculations. Polarizable force fields like AMOEBA show better performance but at a higher computational cost [1].

- Handling Protonation States: Fixed protonation states during simulation can misrepresent the true electrostatic environment. While methods for handling titratable residues exist, they require lengthy simulations to equilibrate [1].

Q4: How can we validate that our computationally designed enzyme actually generates the intended optimal electric field?

Validation can be performed by analyzing the electric field and its effects in the reactant state, which is more computationally tractable than simulating the full reaction pathway. Key metrics include [1]:

- Electric Field Projection: Measuring the electric field projection along the relevant reaction axis.

- Charge Density Topology: Analyzing the topology of the reactant state electron density, as features like electrostatic potential at bond critical points correlate with the applied field and reaction barrier.

- Field Line Topology: Comparing the global distribution of electric field lines around key bonds to those known to be predictive of high reactivity [1].

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Inaccurate Electric Field Calculations

Problem: Computed electric fields within the enzyme active site do not align with benchmark quantum mechanical calculations or experimental data.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large field deviations in specific regions | Use of non-polarizable force fields (e.g., ff14SB, C36m) | Switch to a polarizable force field like AMOEBA for more accurate electrostatic representation [1]. |

| Unphysical field fluctuations | Fixed protonation states of residues | Implement a titratable MD protocol (e.g., using pi-DMD software) that allows protonation states to change during simulation [1]. |

| General inaccuracy vs. QM benchmarks | Neglect of environmental ions or post-translational modifications | Explicitly include physiologically relevant ions in simulations and account for common modifications like phosphorylation [1]. |

| Field strength seems uncorrelated with catalytic activity | Focusing on a single point or vector for field analysis | Adopt a global field analysis using 3D field line distributions or charge density topology, as discrete points can be misleading [1]. |

Troubleshooting Optimization Algorithm Failure

Problem: The optimization algorithm fails to converge on a protein sequence or structure that produces the target electric field, or it converges on physically unrealistic solutions.

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Algorithm stuck in local minima | Poor balance between exploration and exploitation | Integrate Lévy flights into the optimization to enhance exploration and escape local optima [33]. |

| Premature convergence | Population-based optimizer losing diversity | Use mechanisms like the Natural Survivor Method (NSM) or adaptive mutation to maintain population diversity and prevent premature convergence [33]. |

| Slow convergence rate | Inefficient search strategy | Hybridize with Simulated Annealing (SA) to improve exploitation and refine solutions by occasionally accepting worse solutions to explore broader space [33]. |

| Solutions violate physical constraints | Lack of constraints in objective function | Introduce velocity and position bounds or other constraint-handling techniques (e.g., penalty functions, feasibility rules) to keep solutions within physically realistic parameters [34]. |

Experimental Protocol: A Generalized Workflow for Inverse Electric Field Design

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide for computationally designing enzyme variants with optimized electrostatic preorganization.

Phase 1: System Setup and Target Definition

Define the Reaction and Target Field:

- Identify the reaction coordinate and the key bond(s) undergoing electron reorganization.

- Use quantum mechanical calculations (e.g., DFT) on the reaction in solution to understand the intrinsic charge redistribution.

- Define the theoretical optimal electric field, often a vector aligned with the reaction axis or a more complex heterogeneous field, that would maximally stabilize the transition state [1] [3].

Prepare the Initial Protein Model:

- Obtain a starting protein structure (wild-type or a preliminary design).

- Use software like PDB2PQR or H++ to assign initial protonation states at the relevant pH.

- Employ a polarizable force field (AMOEBA) for more accurate electrostatics if computational resources allow [1].

Phase 2: Iterative Electric Field Optimization

Sample Charge Embeddings:

- Systematically sample mutations of residues surrounding the active site (typically within 10-15 Å) to different amino acids that alter charge or dipole (e.g., Lys, Arg, Asp, Glu, Ser, Asn).

- For each variant, run molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to obtain a thermodynamic ensemble of structures [1] [3].

Calculate and Analyze the Electric Field:

- For each MD snapshot, calculate the electric field vector at the key bond(s) of the reactant state.

- Compute the average electric field projection along the reaction axis, or use more advanced metrics like field line topology or charge density topology [1].

Run Optimization Algorithm:

- Use a metaheuristic optimization algorithm (e.g., a modified Artificial Electric Field Algorithm - AEFA-C, Genetic Algorithm) to guide the search for the best sequence.

- Objective Function: Minimize the difference between the computed electric field (from step 4) and the target optimal field (from step 1).

- Constraints: Enforce physical constraints like steric clashes, solubility, and structural stability [34] [33].

Phase 3: Validation and Downstream Analysis

Validate with Free Energy Calculations:

- For the top-ranking designs, perform more computationally expensive calculations (e.g., QM/MM, free energy perturbation) to verify that the designed field actually lowers the reaction barrier compared to the starting model [3].

Propose Mutations for Experimental Testing:

- Generate a final list of point mutations or combination mutants predicted to enhance catalysis via optimal electrostatic preorganization.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages of this protocol:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

The following table details key computational tools and conceptual "reagents" essential for working in this field.

| Item Name | Type | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Polarizable Force Fields | Software/Parameter Set | Force fields like AMOEBA that go beyond fixed partial charges to model electronic polarization, providing a more accurate representation of electric fields within a protein [1]. |

| Metaheuristic Optimizers | Algorithm | Population-based optimization algorithms like the Artificial Electric Field Algorithm (AEFA) or its modified versions (mAEFA, AEFA-C). They are used to efficiently search the vast sequence space for optimal field-generating mutations [34] [33]. |

| Electric Field Probes | Computational Metric | Defined vectors along key chemical bonds. The electric field projection along these probes in the reactant state is a strong predictor of catalytic rate acceleration and is used to guide the inverse design process [1] [3]. |

| Continuum or Explicit Solvent | Simulation Environment | The choice of how to model the solvent (e.g., Generalized Born vs. TIP3P water). This significantly impacts the calculated electrostatic properties and protonation states of residues [1]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Engine | Software | Software like GROMACS, AMBER, or NAMD used to simulate the motion of the protein over time, generating an ensemble of structures for electric field analysis [1]. |

| Protonation State Sampler | Software/Method | Tools like pi-DMD or H++ that help predict or simulate the correct protonation states of acidic and basic residues under physiological conditions, which is critical for accurate field calculations [1]. |

Core Concepts: Why Integrate Rational Design with Directed Evolution?

What are the fundamental limitations of a purely rational design approach?

Purely rational design relies on a predictive understanding of sequence-structure-function relationships, which is often incomplete. Key challenges include:

- Insufficient Structural Data: Reliable structural information is frequently unavailable for the protein of interest. While AI has improved protein structure prediction, it remains limited for larger proteins and macromolecular complexes [35].

- Difficulty Predicting Mutational Effects: The sequence-structure-function relationship is difficult to predict accurately, especially at the single residue level. Rationally designed mutations often fail to have the desired effect because computational strategies struggle with long-range electrostatic effects, dynamic correlations, and second coordination sphere interactions [27].

- Limited Exploration: Rational design typically focuses on a limited number of pre-selected positions, potentially missing beneficial mutations in unexpected regions of the protein [36].

What are the key advantages of integrating directed evolution with rational design?

Integrating these approaches creates a powerful feedback loop that leverages the strengths of both:

- Bypassing Mechanistic Knowledge Gaps: Directed evolution allows for optimization based on observed behavior rather than requiring a detailed, predictive understanding of the mechanism [27].

- Discovering Non-Intuitive Solutions: The random mutagenesis component of directed evolution can uncover highly effective, non-intuitive solutions that computational models or human intuition would not predict [36].

- Optimizing Complex Properties: The combination is exceptionally powerful for optimizing complex properties like electric field preorganization, where rational design alone often lacks the sub-angstrom precision needed [27].

- Refining Computational Models: The functional data from directed evolution experiments on designed variants provides a rich dataset to validate and refine computational models, including those for electric field prediction [27].

How does this integration specifically benefit research on electric fields in enzyme design?

Electric field preorganization is a key strategy natural enzymes use to achieve remarkable catalytic efficiency. Integrating directed evolution with rational design is crucial for optimizing this property because:

- Validating Field Predictions: Computational designs aiming to install a specific electric field can be experimentally validated and refined through directed evolution. Variants with improved activity can be analyzed to understand how mutations fine-tuned the electric field [27].

- Accessing Global Optimization: Directed evolution can introduce mutations distant from the active site that subtly modulate the enzyme's electric field through long-range effects, a level of optimization extremely difficult to achieve by rational design alone [27].

- Incorporating Dynamics: Electric fields within enzymes are not static; they fluctuate with protein dynamics. Directed evolution can select for variants where dynamics are correlated with favorable field orientations at the active site throughout the catalytic cycle [27].

Methodologies and Experimental Workflows

What does a typical integrated workflow look like?

The following diagram illustrates the synergistic, iterative cycle that combines rational and random approaches for enzyme optimization, particularly for properties like electric field engineering.

What are the key mutagenesis methods and when should I use them?

The choice of mutagenesis method is a strategic decision that defines the searchable sequence space. The table below summarizes the primary techniques.

Table 1: Mutagenesis Methods for Integrated Enzyme Engineering

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Disadvantages | Ideal Use Case in Integration |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) [36] | A modified PCR that reduces polymerase fidelity to introduce random point mutations. | Easy to perform; no prior structural knowledge needed. | Biased mutation spectrum (favors transitions); limited amino acid sampling (~5-6 of 19 alternatives per position). | Initial diversification to find beneficial mutations and unexpected hotspots. |

| DNA Shuffling [36] | Homologous recombination of gene fragments from multiple parents. | Combines beneficial mutations; mimics natural recombination. | Requires high sequence homology (>70-75%); crossovers biased to regions of high identity. | Recombining beneficial mutations identified from rational design or prior epPCR rounds. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis [36] | A targeted method to create all 19 possible amino acids at a single residue. | Comprehensive exploration of a specific position; creates high-quality, focused libraries. | Only a few positions can be mutated; libraries can become very large if multiple sites are targeted simultaneously. | Exhaustively exploring residues identified as critical for electric field modulation (e.g., second-sphere residues). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis [37] | Introduces a specific, pre-determined mutation into a gene sequence. | Precise and reliable for testing hypotheses. | Requires a clear, testable hypothesis for the mutation's effect. | Introducing single point mutations predicted by computation to directly alter the active site electric field. |

What high-throughput screening methods are most effective?

Linking genotype to phenotype is the major bottleneck in directed evolution. The power of your screening method must match your library size.

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening and Selection Methods

| Method | Principle | Throughput | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) [35] [38] | Cells or in vitro compartments displaying active enzymes are sorted based on fluorescence. | Very High ( >10⁸ cells) | The evolved property must be linked to a change in fluorescence, often via a surrogate substrate. |

| Microtiter Plate-Based Screening [35] [36] | Individual clones are cultured in 96- or 384-well plates and assayed using colorimetric or fluorometric substrates. | Medium (10³ - 10⁵ variants) | Throughput is lower but provides quantitative data; automation is key. Surrogate substrates may not replicate native activity. |

| Selection-Based Methods [35] [36] | Desired function is coupled to host survival (e.g., antibiotic resistance, essential nutrient production). | Extremely High ( >10⁹ variants) | Powerful for large libraries but can be difficult to design and may introduce artifacts; provides less quantitative data. |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

We are not finding improved variants after several rounds of evolution. What could be wrong?

This common problem often stems from issues with the library or the screening method.

Problem: Low Library Diversity or Quality.

- Cause 1: Over-reliance on a single mutagenesis method (e.g., only epPCR) leading to restricted sequence space exploration [36].

- Solution: Adopt a combined strategy. Use epPCR for broad exploration, followed by DNA shuffling to recombine hits, and finally site-saturation mutagenesis to optimize key positions [36].

- Cause 2: The screening pressure is too high, eliminating all but a few dead variants.

- Solution: Use a more gradual screening pressure. For example, when selecting for thermostability, increase the temperature incrementally over rounds rather than starting at a denaturing temperature [36].

Problem: The Screen is Not Accurately Reporting the Desired Function.

- Cause: The screening assay uses a surrogate substrate that does not correlate well with the desired activity or electric field effect [35].

- Solution: Validate your screening assay rigorously. Ensure that improvements detected with the surrogate substrate (e.g., a fluorogenic compound) translate to improvements with the native substrate. For electric field optimization, the assay should be sensitive to changes in transition state stabilization.

Our computationally designed variants consistently show poor protein expression and stability.

This is a frequent challenge when rational design focuses exclusively on active-site function.

- Problem: Neglected Global Protein Scaffold.

- Cause: Computational designs that focus solely on active-site residues (e.g., for electric field tuning) can destabilize the overall protein fold or create aggregation-prone surfaces [27].

- Solution: Use directed evolution to "rescue" the designed variant. Subject the poorly expressing but functionally sound design to mild random mutagenesis and screen directly for improved expression or solubility. This allows the evolution to find stabilizing mutations that the rational design missed [27].

How can we avoid evolutionary dead ends where improvements plateau?

- Problem: Diminishing Returns in Later Rounds.

- Cause: Accumulated mutations can begin to have epistatic (interdependent) effects that are difficult to overcome with simple point mutagenesis [36].

- Solution: Introduce "family shuffling" by recombining your best-evolved variant with homologous genes from other species. This injects a large amount of pre-functionalized diversity and can help escape local fitness maxima [36]. Additionally, return to a rational analysis of your best variant's structure to identify new regions for targeted diversification.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Kits for Directed Evolution

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Application Example in Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|

| Kapa Biosystems PCR & qPCR Reagents [38] | Provides engineered DNA polymerases with enhanced fidelity, processivity, and inhibitor resistance. | Robust amplification of gene libraries during error-prone PCR or library construction. Ideal for GC-rich or difficult templates. |

| KAPA SYBR FAST qPCR Kit [38] | A master mix for sensitive and accurate quantitative PCR. | Quantifying library size and diversity, or measuring gene expression levels of engineered enzymes in a host. |

| KAPA PROBE FORCE qPCR Kit [38] | A qPCR master mix resistant to inhibitors found in blood, tissue, and plant samples. | Enabling direct qPCR from crude lysates during high-throughput screening, bypassing the need for DNA purification. |

| Spin Column DNA Purification Kits (e.g., Monarch Kits) [39] [22] | Purification of DNA to remove contaminants like salts, EDTA, or proteins that can inhibit enzyme activity. | Essential step before setting up restriction digests for cloning or before performing high-fidelity PCR. Prevents incomplete digestion and reaction failure. |

| Dam-/Dcm- E. coli Strains (e.g., NEB #C2925) [39] [22] | Bacterial host strains that lack Dam and Dcm methylation systems. | Propagating plasmid DNA to avoid methylation that can block digestion by methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes during library construction. |

Overcoming Limitations in Current Enzyme Design Protocols