Harnessing Light and Enzymes: New Frontiers in Asymmetric Synthesis

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis, a powerful strategy that merges the energy of visible light with the precise stereocontrol of enzymes.

Harnessing Light and Enzymes: New Frontiers in Asymmetric Synthesis

Abstract

This article explores the rapidly evolving field of photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis, a powerful strategy that merges the energy of visible light with the precise stereocontrol of enzymes. We delve into the foundational principles of flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductases and other photoenzymes, detailing their mechanism in generating and steering reactive radicals for asymmetric bond formation. The review covers methodological advances in synthesizing valuable chiral building blocks, including fluorinated amides, amines, and diamines, which are pivotal in pharmaceutical and agrochemical development. Practical guidance on troubleshooting reaction parameters and optimizing systems through enzyme engineering is provided. Finally, we present a comparative analysis validating this biocatalytic approach against traditional chemical methods, highlighting its superior sustainability, selectivity, and potential to access novel chemical space for drug discovery.

The Principles of Photoenzymatic Catalysis: Merging Light with Biocatalysis

Defining Photoenzymatic Enantioselective Synthesis

Photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis represents a cutting-edge interdisciplinary approach that merges the principles of photocatalysis with the precision of enzymatic catalysis to create chiral molecules with high optical purity. This methodology leverages visible light to generate highly reactive radical intermediates through photoexcitation of biological cofactors or integrated photocatalysts, while enzymes provide the chiral environment necessary to control the stereochemical outcome of the reaction. The result is a powerful synthetic platform that achieves exceptional enantioselectivity in transformations that are challenging or impossible to accomplish using traditional chemical or biological methods alone [1].

This hybrid catalytic strategy addresses a fundamental challenge in synthetic chemistry: controlling the stereochemistry of highly reactive, short-lived radical intermediates. By confining these radicals within enzyme active sites, researchers can direct reactions toward single enantiomers with precision that often surpasses what can be achieved with small-molecule chiral catalysts. The field has expanded rapidly in recent years, enabling previously inaccessible asymmetric transformations through the repurposing of natural enzymes for "new-to-nature" reactivities [2]. This approach is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical and agrochemical applications where chiral molecules with defined stereochemistry are essential for biological activity and regulatory approval.

Fundamental Principles and Mechanisms

Photoenzymatic catalysis operates through several distinct mechanistic paradigms, each combining light energy with enzymatic stereocontrol in different configurations:

Net-Reduction Photoenzymatic Catalysis

This common mechanism involves photoinduced electron transfer from reduced enzyme cofactors to substrate molecules, generating radical intermediates that undergo subsequent transformations before being quenched through hydrogen atom transfer. The flavin hydroquinone (FMNH-) in its photoexcited state serves as a potent reductant, capable of directly reducing substrates without requiring external photocatalysts [3]. The enzyme active site then controls the stereochemistry of the radical addition and subsequent hydrogen atom transfer steps.

Redox-Neutral Photoenzymatic Catalysis

Some systems operate without net redox change, utilizing direct visible-light excitation of enzyme-substrate complexes or electron donor-acceptor complexes formed within the enzyme active site. These transformations often involve energy transfer mechanisms or radical pairs generated through homolytic bond cleavage [2].

Synergistic Dual Photo-/Enzymatic Catalysis

In this approach, external photocatalysts (such as transition metal complexes or organic dyes) work cooperatively with enzymes to achieve stereocontrol. The photocatalyst handles the radical generation steps, while the enzyme controls the stereoselectivity of the transformation. This division of labor expands the range of compatible radical precursors beyond those that can be directly activated by biological cofactors [4].

Table 1: Key Photoenzymatic Mechanisms and Their Characteristics

| Mechanistic Type | Radical Generation Method | Stereocontrol Source | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Net-Reduction | Photoexcited flavin hydroquinone (FMNH-) | Enzyme-mediated HAT | Ene-reductase catalyzed hydroalkylation [5] |

| Redox-Neutral | Direct substrate excitation or EDA complexes | Enzyme-controlled radical addition | PLP-dependent radical α-alkylation [6] |

| Dual Catalysis | External photocatalyst (e.g., RhB) | Enzyme active site confinement | ERED-RhB catalyzed hydroamination [4] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Photoenzymatic Synthesis of Fluorinated Amides via Ene-Reductase Catalysis

This protocol describes the enantioselective hydroalkylation of alkenes with fluorinated bromoamide radicals using engineered ene-reductases, adapted from published procedures with yields up to 91% and 97% enantiomeric excess (ee) [5].

Reagents and Materials

- Enzyme: OYE1 ene-reductase (wild-type or Y375F mutant)

- Cofactor Regeneration System: Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH, 2 mg/mL), NADP+ (0.5 mM), D-(+)-glucose (50 mM)

- Radical Precursor: Fluorine-containing bromoamide substrate (F-1, 10 mM)

- Alkene Substrate: Electron-rich alkene (15 mM)

- Buffer: Tris-HCl (50 mM, pH 8.5)

- Light Source: Blue LEDs (465 nm, 45 W)

Procedure

- Reaction Setup: In a 5 mL glass vial, combine Tris-HCl buffer (2 mL), fluorinated bromoamide F-1 (0.02 mmol), alkene substrate (0.03 mmol), NADP+ (0.001 mmol), and glucose (0.1 mmol).

- Enzyme Addition: Add OYE1 enzyme (2 mol%) and GDH (2 mg/mL) to the reaction mixture.

- Light Exposure: Seal the vial and irradiate with blue LEDs (465 nm, 45 W) while stirring at 25°C for 24 hours. Maintain constant temperature using a circulating water bath.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by regular sampling and GC-MS analysis.

- Product Isolation: After completion, extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL). Combine organic layers, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel using hexane/ethyl acetate gradient elution.

Analytical Data

Characterize the purified fluorinated amide by ( ^1H ) NMR, ( ^{13}C ) NMR, ( ^{19}F ) NMR, and HRMS. Determine enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC or GC analysis.

Protocol 2: Intermolecular Radical Hydroamination for Chiral Amine Synthesis

This protocol describes the photoenzymatic generation of nitrogen-centered radicals and their enantioselective addition to olefins using evolved XenB ene-reductase, achieving up to 88% yield and 97% ee [3].

Reagents and Materials

- Enzyme: XenB ene-reductase variant (E2 mutant: XenB-A232L)

- Cofactor Regeneration: GDH (2 mg/mL), NADP+ (0.5 mM), D-glucose (50 mM)

- Nitrogen Radical Precursor: Carbamate with 4-cyanophenolate leaving group (10 mM)

- Olefin Substrate: Styrene derivative (15 mM)

- Buffer: Imidazole-HCl (50 mM, pH 6.5)

- Light Source: Blue LEDs (420-430 nm)

Procedure

- Reaction Setup: In a 5 mL glass vial, combine imidazole-HCl buffer (2 mL), carbamate substrate (0.02 mmol), olefin (0.03 mmol), NADP+ (0.001 mmol), and glucose (0.1 mmol).

- Enzyme Addition: Add XenB variant (2 mol%) and GDH (2 mg/mL) to the reaction mixture.

- Photoreaction: Irradiate with blue LEDs (420-430 nm) while stirring at 25°C for 24-48 hours.

- Reaction Quenching: Extract the reaction mixture with dichloromethane (3 × 5 mL).

- Purification: Combine organic extracts, dry over Na₂SO₄, concentrate, and purify by preparative TLC or flash chromatography.

Analytical Data

Characterize the chiral amine product by ( ^1H ) NMR, ( ^{13}C ) NMR, and HRMS. Determine enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC after derivatization.

Table 2: Key Reaction Optimization Parameters for Photoenzymatic Systems

| Parameter | Optimal Conditions (Fluorinated Amides) | Optimal Conditions (Hydroamination) | Impact on Yield/Selectivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | 465 nm, 45 W blue LEDs | 420-430 nm blue LEDs | Wavelength affects cofactor excitation; power influences radical generation rate |

| Buffer/pH | Tris-HCl, pH 8.5 | Imidazole-HCl, pH 6.5 | pH affects cofactor redox potential and substrate binding |

| Enzyme Loading | 2 mol% OYE1 | 2 mol% XenB variant | Higher loading increases reaction rate but may cause scattering |

| Cofactor System | GDH/glucose/NADP+ | GDH/glucose/NADP+ | Maintains reduced flavin pool for continuous radical generation |

| Reaction Time | 24 hours | 24-48 hours | Longer times needed for electron-deficient substrates |

Visualization of Experimental Workflows

General Photoenzymatic Catalysis Workflow

Ene-Reductase Catalyzed Fluorinated Amide Synthesis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Photoenzymatic Enantioselective Synthesis

| Reagent/Enzyme | Function/Role | Application Examples | Optimization Tips |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ene-Reductases (OYE1, XenB) | Flavin-dependent enzymes for radical generation & stereocontrol | Hydroalkylation, hydroamination, lactonization | Enzyme engineering improves activity & selectivity [5] [3] |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Cofactor regeneration system | Maintains NADPH pool for continuous flavin reduction | Use excess GDH/glucose to ensure cofactor turnover |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | Native photoactive cofactor | Electron transfer, radical generation | Ensure sufficient FMN loading (0.5-1 mol%) |

| Naphthyl-Substituted Amides | Fluorinated radical precursors | Synthesis of chiral fluorinated pharmaceuticals | Amide group enhances enzyme binding vs. esters [5] |

| Katritzky Pyridinium Salts | Electrophilic radical precursors | α-Alkylation of amino acids | Enable redox-neutral transformations [6] |

| Rhodamine B | External organic photocatalyst | Synergistic catalysis with EREDs | Enables green light excitation (530-540 nm) [4] |

| N-Amido Pyridinium Salts | Nitrogen-centered radical precursors | Vicinal diamine synthesis | N-N bond cleavage under mild conditions [4] |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Synthesis

Photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis has enabled efficient routes to valuable pharmaceutical intermediates and active ingredients:

Fluorinated Pharmaceutical Compounds

The incorporation of fluorine atoms into drug molecules enhances metabolic stability, membrane permeability, and binding affinity. The photoenzymatic synthesis of fluorinated amides with distal chirality provides access to structural motifs found in numerous pharmaceuticals [5]. This method addresses the challenge of stereoselective fluorination, which is difficult to achieve using conventional synthetic approaches.

Chiral Amine Synthesis

Chiral amines constitute key structural elements in approximately 40% of small-molecule pharmaceuticals. The photoenzymatic hydroamination platform enables direct enantioselective incorporation of amine groups into olefin scaffolds, providing streamlined access to these valuable building blocks [3]. This approach is particularly valuable for creating amine-containing stereocenters remote from functional groups that would typically anchor substrates to traditional catalysts.

Non-Canonical Amino Acids

Photoenzymatic methods have enabled the synthesis of challenging α-tri- and tetrasubstituted non-canonical amino acids (ncAAs) using PLP-dependent threonine aldolases [6]. These unnatural amino acids serve as essential building blocks for peptide therapeutics and bioactive natural products, with applications in drug development and chemical biology.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Successful implementation of photoenzymatic reactions requires careful attention to several critical parameters:

Light Source Optimization

- Wavelength Selection: Match light wavelength to the absorption maxima of the photoredox cofactor (typically 440-470 nm for flavins).

- Intensity Control: Optimize light intensity to balance radical generation rate with potential enzyme photodamage.

- Uniform Illumination: Ensure reaction vessels are positioned to receive even light distribution for consistent results.

Enzyme Engineering Strategies

- Active Site Mutagenesis: Target residues surrounding the substrate binding pocket to improve activity and selectivity.

- Directed Evolution: Employ iterative rounds of mutagenesis and screening to optimize enzyme performance for non-natural reactions.

- Cofactor Engineering: Modify cofactor binding pockets to alter redox properties or accommodate synthetic photocatalysts.

Reaction Condition Optimization

- Buffer Composition: Screen different buffer systems and pH values, as these significantly impact both enzyme activity and radical stability.

- Cofactor Regeneration: Ensure robust NADPH regeneration systems to maintain reduced flavin pools throughout the reaction.

- Substrate Engineering: Design radical precursors with appropriate redox potentials and leaving groups for efficient activation by photoexcited cofactors.

The protocols and guidelines presented here provide a foundation for implementing photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis in research settings. As the field continues to evolve, these methodologies are expected to expand the toolbox available for asymmetric synthesis, particularly for challenging transformations involving radical intermediates.

Ene-reductases (EREDs) from the Old Yellow Enzyme (OYE) family are flavin-dependent biocatalysts that have become indispensable tools for asymmetric organic synthesis. These enzymes traditionally catalyze the stereoselective hydrogenation of activated alkenes, a pivotal transformation for generating chiral synthons with up to two stereogenic centers [7]. The versatility of these enzymes is profoundly expanded when combined with light, enabling novel radical reactions that are challenging to achieve with traditional small-molecule catalysts. This application note details the core components of these systems—the ene-reductase protein scaffolds and their flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactors—framed within contemporary research on photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis. It provides a structured overview of their catalytic capabilities, quantitative performance data, and detailed protocols for implementing both traditional and photochemical enantioselective reactions.

Core Components and Mechanisms

The Ene-Reductase Enzyme Scaffold

Ene-reductases are flavoproteins that belong to the Old Yellow Enzyme family, first discovered over 80 years ago [7]. They are ubiquitous in nature, found in yeasts, bacteria, plants, and parasitic eukaryotes [8]. While their physiological roles are not fully elucidated, they are suggested to participate in detoxification processes, response to oxidative stress, and specialized metabolic pathways such as jasmonic acid biosynthesis in plants and prostaglandin biosynthesis in trypanosomes [8].

The discovery and characterization of new EREDs continue to expand the biocatalytic toolbox. For instance, the thermophilic ene-reductase CaOYE from Chloroflexus aggregans demonstrates the potential of exploring extremophile microorganisms. CaOYE exhibits high thermostability, good solvent tolerance, and a wide pH optimum, making it a robust biocatalyst for potentially harsh industrial conditions [8]. Structurally, EREDs are known to assemble as dimers, though CaOYE behaves as a monomer in solution, highlighting the diversity within this enzyme family [8].

The Flavin Cofactor: A Versatile Redox Agent

The catalytic prowess of EREDs is derived from their non-covalently bound flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor. The flavin ring system is a versatile redox-active chromophore that can exist in three stable states: oxidized (FMNox), semiquinone (FMNsq, a radical species), and hydroquinone (FMNhq) [9] [10].

The traditional catalytic cycle for alkene reduction involves a hydride transfer from FMNhq to the β-carbon of an activated alkene substrate, followed by protonation of the resulting enolate by a conserved active-site tyrosine residue [9]. This concerted mechanism yields the saturated product and returns the flavin to its oxidized state (FMNox). Regeneration of FMNhq is typically achieved using NAD(P)H as a stoichiometric hydride donor [7].

Beyond this ground-state chemistry, the flavin cofactor can undergo photoexcitation with visible light. The excited state of the reduced flavin hydroquinone (FMNhq*) is an exceptionally potent single-electron reductant, with a reduction potential estimated at -2.26 V vs. SCE, enabling the activation of challenging radical precursors such as chlorinated amides [9]. This photochemical mechanism mirrors processes in natural photoenzymes like DNA photolyase and forms the basis for non-natural radical reactions catalyzed by engineered EREDs [9].

Table 1: Key States of the Flavin Cofactor and Their Roles

| Flavin State | Redox Potential (vs. SCE) | Primary Role in Catalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Oxidized (FMNox) | — | Electron acceptor in reductive cycles |

| Hydroquinone (FMNhq) | -215 mV | Hydride donor in ground-state alkene reduction |

| Excited Hydroquinone (FMNhq*) | -2.26 V | Potent single-electron reductant for radical initiation |

| Semiquinone (FMNsq) | — | Hydrogen atom donor for radical termination |

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of ene-reductases is quantified through metrics such as turnover number, enantioselectivity, and stability. Engineered photoenzymes demonstrate remarkable efficiency in novel transformations.

Table 2: Quantitative Performance of Selected Ene-Reductase Catalyzed Reactions

| Enzyme / System | Reaction Type | Typical Yield | Stereoselectivity | Turnover Number (kcat)/Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| VEnT1.3 Photoenzyme [11] | Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition | Quantitative (>99%) | >99% e.e. | ( k_{cat} = 13.0 \text{ s}^{-1} ); >1,300 total turnovers |

| NCR-C9 ERED [9] | Radical Hydrodehalogenation & Cyclization | Up to 92% | Up to 97:3 e.r. | — |

| GluER-T36A ERED [9] | Photochemical Radical Cyclization | Up to 92% | 94:6 e.r. | — |

| CaOYE [8] | Traditional Alkene Reduction | Variable, substrate-dependent | — | High thermostability & solvent tolerance |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Photoenzymatic Intramolecular [2+2] Cycloaddition

This protocol describes a semipreparative-scale enantioselective cycloaddition using the engineered photoenzyme VEnT1.3, which contains a genetically encoded thioxanthone sensitizer [11].

Reagents:

- Photoenzyme: Purified VEnT1.3 (0.5 mol%) [11].

- Substrate: Carbon-linked quinolone derivative

1. - Buffer: Aerobic phosphate or Tris buffer (50-100 mM, pH 7.5-8.0).

- Light Source: High-power LED lamp (λ = 405 nm).

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a glass vial, dissolve substrate

1(e.g., 0.1 mmol) in the appropriate buffer to a final concentration of 5-10 mM. Add the VEnT1.3 photoenzyme to a final loading of 0.5 mol%. - Irradiation: Seal the vial and place it under the 405 nm LED light source with constant stirring. Maintain the reaction temperature at 25-30°C using a water bath or cooling fan.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by analytical HPLC or TLC. The reaction typically reaches >99% conversion within minutes, depending on light intensity [11].

- Work-up: Upon completion, extract the reaction mixture with an organic solvent (e.g., ethyl acetate). Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous MgSO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Product Purification: Purify the crude product (

(+)-1a) using flash chromatography on silica gel. Product identity and enantiopurity can be confirmed by ( ^1\text{H} ) NMR and chiral HPLC, respectively [11].

- Reaction Setup: In a glass vial, dissolve substrate

Protocol 2: ERED-Catalyzed Asymmetric Radical Cyclization

This protocol outlines the setup for an enantioselective radical cyclization using an engineered ERED (e.g., NCR-C9 or GluER-T36A) under photochemical conditions [9].

Reagents:

- Enzyme: Purified ERED variant (e.g., NCR-C9 for bromoketones, GluER-T36A for chloroamides).

- Cofactor Recycling System: NADP⁺ (catalytic amount), engineered glucose dehydrogenase (GDH-105), and D-glucose.

- Substrate: Radical precursor (e.g., α-bromoketone

5or α-chloroamide10). - Buffer: Phosphate buffer (50-100 mM, pH 7.0-8.0).

- Light Source: Violet or cyan LED lamp (λ = 400-500 nm, selected based on the substrate-enzyme pair).

Procedure:

- Cofactor System Preparation: In a reaction vial, combine the buffer, NADP⁺ (0.1-1 mol%), GDH-105 (1-5 mg), and an excess of D-glucose (e.g., 5-10 equiv).

- Reaction Initiation: Add the ERED catalyst and the radical precursor substrate. Seal the vial.

- Irradiation and Mixing: Place the vial under the appropriate LED light source with vigorous stirring to ensure oxygenation for FMN reduction. Irradiate for the specified duration (typically several hours).

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor consumption of the starting material by TLC or GC-MS.

- Work-up and Analysis: Extract the product with an organic solvent, concentrate the organic phase, and purify the product via flash chromatography. Determine enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) by chiral HPLC or GC [9].

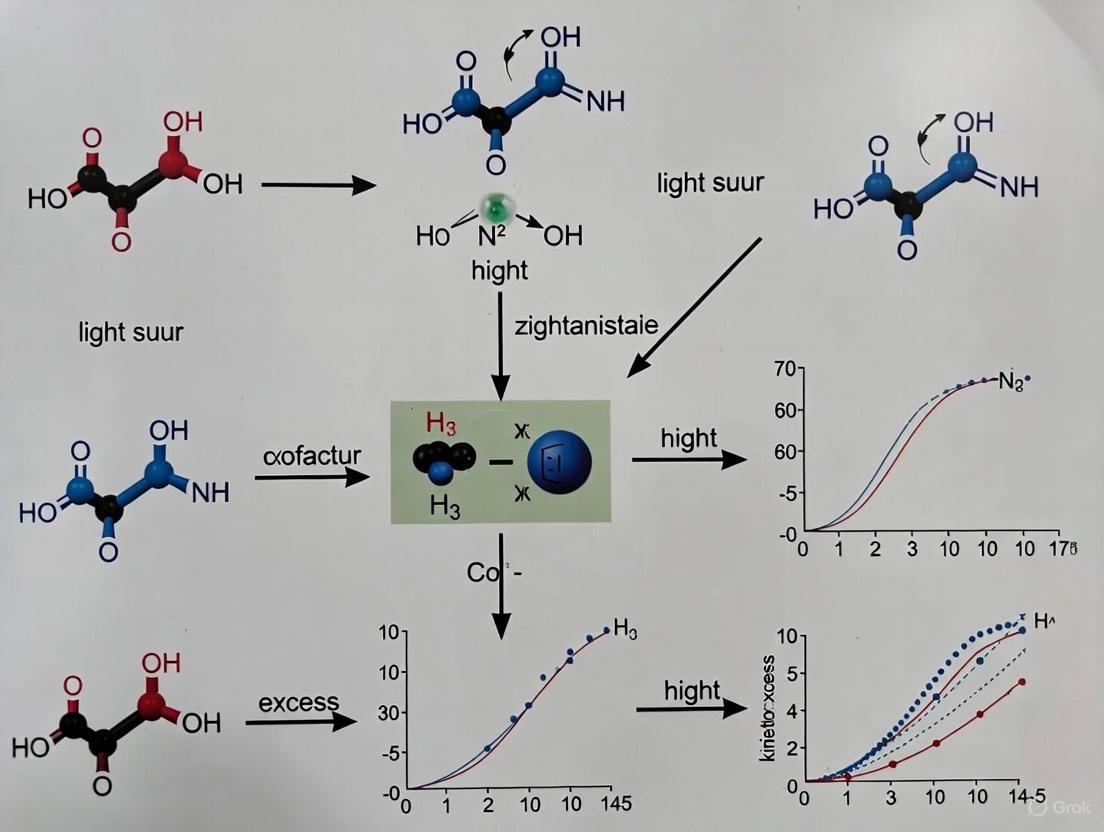

Diagram 1: Photochemical Radical Cyclization Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ene-reductase catalysis, especially for non-natural photochemical reactions, relies on key reagents and materials.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Ene-Reductase Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered EREDs (NCR-C9, GluER) | Chiral scaffold for enantioselective radical termination and substrate binding. | Asymmetric radical cyclization & hydrodehalogenation [9]. |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH-105) | Cofactor recycling enzyme; regenerates NADPH from NADP+ using glucose. | Sustained catalytic cycles in radical reactions [9]. |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | Redox-active cofactor; core photocatalyst in electron transfer reactions. | Required for in vitro reconstitution of ERED activity. |

| NADP⁺ | Oxidized nicotinamide coenzyme; electron acceptor in GDH-catalyzed recycling. | Catalytic NADPH regeneration in photobiocatalytic systems [9]. |

| Visible Light LEDs (400-500 nm) | Energy source for flavin photoexcitation to access potent redox states. | Enabling radical reactions with low reduction potential substrates [9]. |

| Thioxanthone Photoenzyme (VEnT1.3) | Genetically encoded triplet sensitizer for visible light-driven energy transfer. | Enantioselective [2+2] cycloadditions under visible light [11]. |

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Visualization

The catalytic mechanisms of ene-reductases, both traditional and photochemical, can be visualized as interconnected pathways. The diagram below integrates the hydride transfer, ground-state electron transfer, and photoinduced electron transfer pathways, highlighting the central role of the flavin cofactor.

Diagram 2: Ene-Reductase Catalytic Pathways.

The merger of photocatalysis with enzymatic catalysis represents a paradigm shift in synthetic chemistry, opening avenues for enantioselective transformations that are challenging to achieve through conventional methods. This field leverages light to generate high-energy radical intermediates via photoinduced electron transfer (PET), while enzymes exert exquisite stereochemical control over these reactive species. The integration of these two powerful strategies enables access to new-to-nature enzymatic functions and provides sustainable routes for synthesizing complex chiral molecules, including pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. This article delves into the mechanistic principles underpinning radical generation through PET and provides detailed protocols for implementing these reactions within photoenzymatic frameworks.

Core Mechanistic Pathways and Quantitative Data

Photoenzymatic catalysis utilizes light energy to initiate single-electron transfer events, generating radical intermediates that are subsequently managed within enzyme active sites. The following table summarizes key catalytic systems and their performance characteristics.

Table 1: Representative Photoenzymatic Systems for Enantioselective Synthesis

| Catalytic System | Reaction Type | Key Radical Intermediate | Performance (Yield / e.e.) | Primary Light Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ene-Reductase (ERED) + Photocatalyst [12] | Intermolecular Hydroalkylation of Alkenes | Prochiral Carbon-centered Radical | Up to 99% yield, 99% e.e. [12] | Visible Light |

| Ene-Reductase (Direct Flavin Excitation) [13] | Redox-Neutral Hydroarylation | Carbon-centered Radical from Alkene | Excellent enantioselectivity reported [13] | Visible Light |

| Synergistic ERED & Rhodamine B [14] | Hydroamination of Enamides | Nitrogen-Centered Radical (NCR) | >99% e.e. [14] | Green Light (530-540 nm) |

| Flavin-dependent 'Ene'-Reductase [15] | Hydrocyanoalkylation of Alkenes | Cyanoalkyl Radical | High enantioselectivity [15] | Visible Light |

The mechanism of action across different systems hinges on the precise initiation of radical species. Two primary pathways have been established:

- Enzyme-Photocatalyst Synergy: An external photoredox catalyst absorbs light to initiate the radical reaction, while a separate enzyme controls stereoselectivity. For example, in the hydrocyanoalkylation of alkenes, the flavin hydroquinone (FMNhq) within ene-reductases can singly reduce a cyanoalkyl radical precursor. This leads to the formation of a cyanoalkyl radical, which adds across an alkene. The enzyme's active site then stereoselectively controls the radical-terminating hydrogen atom transfer (HAT). [15]

- Direct Flavin Excitation: In systems without an external photocatalyst, the enzyme's native flavin cofactor (FMN or FAD) serves a dual role. Upon photoexcitation, the flavin can directly participate in single-electron transfer to or from a substrate, generating a radical pair. This mechanism is exemplified in the redox-neutral hydroarylation of alkenes, where photoexcited flavin semiquinone (FMNsq) acts as a single-electron oxidant. [13]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Intermolecular Radical Hydroalkylation via Photoenzymatic Catalysis

This protocol describes the enantioselective intermolecular hydroalkylation of terminal alkenes with α-halo carbonyl compounds, catalyzed by a flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductase, adapted from published procedures. [12]

Principle: Visible light irradiation triggers an electron transfer that generates a radical from an α-halo carbonyl compound. This radical adds to a terminal alkene, and the resulting prochiral radical intermediate is stereoselectively reduced within the enzyme's active site.

Materials:

- Enzyme: Flavoprotein 'ene'-reductase (e.g., GluER variant [14]).

- Cofactor: NADP+ (1.5 mol%).

- Substrates: Terminal alkene (e.g., α-methylstyrene), α-halo carbonyl compound (e.g., α-bromoamide).

- Cofactor Regeneration System: Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH, 4 U), D-Glucose.

- Solvent: Phosphate buffer (KPi, 100 mM, pH 6.0) with 20% v/v DMSO.

- Light Source: Blue LEDs (e.g., 390-400 nm or 450-455 nm) or Green LEDs (530-540 nm [14]).

- Reaction Vessel: Schlenk tube or vial suitable for irradiation under inert atmosphere.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 2.0 mL reaction vial, sequentially add:

- KPi buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0) containing 20% v/v DMSO.

- Terminal alkene (0.008 mmol).

- α-Halo carbonyl compound (0.032 mmol, 4.0 equiv).

- 'Ene'-reductase (2 mol%).

- NADP+ (1.5 mol%).

- Glucose dehydrogenase (4 U).

- D-Glucose (0.024 mmol).

- Degassing: Purge the reaction mixture with nitrogen (N₂) for 10-15 minutes to create an anaerobic environment.

- Irradiation: Place the sealed reaction vessel approximately 5 cm from the LED light source and stir at room temperature for 16 hours.

- Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS.

- Work-up: After completion, extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 2 mL). Combine the organic layers, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography on silica gel to obtain the desired chiral γ-stereogenic carbonyl compound.

- Analysis: Determine enantiomeric excess (e.e.) by chiral HPLC or SFC analysis.

Troubleshooting Tips:

- Low Conversion: Ensure the light source is of sufficient intensity and that the reaction vessel is transparent to the relevant wavelengths. Check enzyme activity and the integrity of the cofactor regeneration system.

- Poor Enantioselectivity: Screen different 'ene'-reductase homologues or mutants, as the active site architecture is critical for stereocontrol. [12] [14]

Protocol: Hydroamination via Synergive Photo/Biocatalysis

This protocol outlines the enantioselective synthesis of vicinal diamines via hydroamination of enamides, using a dual system of an ene-reductase and an organophotocatalyst. [14]

Principle: Green light excites the organophotocatalyst Rhodamine B (RhB), which engages in single-electron transfer with an N-amidopyridinium salt. This triggers N–N bond cleavage to generate a nitrogen-centered radical (NCR). The NCR adds to the enamide, and the resulting radical intermediate is stereoselectively reduced by the flavin hydroquinone within the ene-reductase.

Materials:

- Biocatalyst: Ene-reductase mutant (e.g., GluER-M5 or GluER-Y177F-F269V). [14]

- Photocatalyst: Rhodamine B (RhB).

- Substrates: Enamide, N-amidopyridinium salt.

- Cofactor System: NADP+, Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH), D-Glucose.

- Solvent: KPi buffer (100 mM, pH 6.0) with 20% v/v DMSO.

- Light Source: Green LEDs (530-540 nm).

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 2.0 mL vial, combine:

- Enamide 1 (0.008 mmol).

- N-amidopyridinium salt 2 (0.032 mmol, 4.0 equiv).

- GluER mutant (2 mol%).

- GDH (4 U).

- NADP+ (1.5 mol%).

- Glucose (0.024 mmol).

- Rhodamine B (catalytic amount).

- KPi buffer with 20% v/v DMSO to a total volume of 2.0 mL.

- Degassing: Sparge the mixture with N₂ for 10 minutes.

- Irradiation: Stir the reaction under irradiation with green LEDs for 16 hours at room temperature.

- Work-up and Purification: Extract with ethyl acetate, dry the organic phase, and concentrate. Purify the residue by preparative TLC or column chromatography.

- Analysis: Determine yield and enantiomeric excess as previously described.

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the general catalytic cycle for a synergistic photoenzyme system, integrating the key steps of photoinduced radical generation and enzymatic stereocontrol.

Diagram 1: Synergistic Photoenzyme Catalytic Cycle. This workflow shows the integration of photochemical radical generation with enzymatic stereocontrol, typical for hydroalkylation and hydroamination reactions. HAT: Hydrogen Atom Transfer.

The mechanistic pathway for direct flavin excitation, an alternative to synergistic systems, is shown below.

Diagram 2: Direct Flavin Excitation Pathway. This mechanism involves direct photoexcitation of the enzyme-bound flavin cofactor, which acts as an internal photoredox catalyst for single-electron oxidation. SET: Single-Electron Transfer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of photoenzymatic radical reactions requires careful selection of components. The following table lists essential reagents and their functions.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Photoenzymatic Radical Generation and Control

| Reagent / Component | Function / Role | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Flavin-Dependent 'Ene'-Reductases | Biocatalyst for stereocontrol; provides flavin cofactor (FMN) as inherent photoredox center. | GluER variants (e.g., GluER-M5, GluER-Y177F-F269V) [14] [15] |

| Organophotoredox Catalysts | External photosensitizer to absorb light and drive electron transfer reactions. | Rhodamine B (RhB) [14] |

| Radical Precursors | Stable molecules that, upon single-electron reduction or oxidation, fragment to yield reactive radicals. | α-Halo carbonyl compounds [12], N-Amidopyridinium salts [14] |

| Cofactor Regeneration System | Maintains the required redox state of enzymatic cofactors (e.g., NADPH for FMN reduction) sustainably. | Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) / Glucose [14] |

| Electron Shuttles (in bio-hybrid systems) | Mediate electron transfer from microbial metabolism to chemical reactants under light excitation. | Endogenously secreted Flavins (Riboflavin, FMN) [16] |

Understanding Electron Donor-Acceptor (EDA) Complex Formation

Electron Donor-Acceptor (EDA) complexes, also referred to as charge-transfer complexes, represent a pivotal class of supramolecular assemblies formed through the association of electron-rich (donor) and electron-deficient (acceptor) molecules [17]. These complexes are characterized by ground-state electronic interactions that enable new absorption bands in the visible light spectrum. Upon photoexcitation, this interaction facilitates a single electron transfer (SET) from the donor to the acceptor, generating highly reactive radical pairs capable of initiating unique transformations under mild conditions [18].

Within the rapidly evolving field of photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis, EDA complex photochemistry has emerged as a powerful strategy to complement and enhance biocatalytic reactivity. This approach enables the generation of non-natural radical intermediates, including challenging nitrogen-centered radicals (NCRs) and carbon-centered radicals, which are then precisely orchestrated within the enzyme's chiral active site to produce enantioenriched molecules [19] [4]. The integration of EDA complexes with enzymes addresses long-standing challenges in controlling the reactivity and selectivity of high-energy radical species, opening new synthetic pathways for pharmaceutical and bioactive molecule development.

Fundamental Principles and Quantitative Characterization

Mechanistic Workflow of EDA Complex Photoactivation

The following diagram illustrates the generalized mechanism of EDA complex formation, photoexcitation, and subsequent radical generation that can be coupled with enzymatic stereocontrol.

Quantitative Characterization of EDA Complexes

The formation and stability of EDA complexes can be quantitatively monitored using spectroscopic techniques, particularly UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. The following table summarizes key characterization parameters for a representative EDA complex formed between 1,2-dinitrobenzene (acceptor) and tri-n-butylamine (donor) [20].

Table 1: Quantitative Characterization of a Model EDA Complex

| Parameter | Experimental Value | Experimental Conditions | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Charge-Transfer Band (λ_max) | 490 nm | Acetonitrile, equimolar donor/acceptor | Confirms visible light absorption enabling photoexcitation |

| Optimal Binding Stoichiometry | 4:1 (Acceptor:Donor) | Job's Plot method | Deviates from common 1:1 ratio, informs reaction stoichiometry |

| Solvent Effect | Significant absorption reduction | Addition of 600 μL water to acetonitrile solution | Hydrogen-bonding solvents can disrupt EDA complex formation |

| Molar Absorptivity | Concentration-dependent increase | Constant acceptor, increasing donor | Validates complex formation and allows determination of association constant |

Experimental Protocols for EDA Complex Studies

Protocol 1: Spectroscopic Identification and Characterization

This protocol describes the procedure for identifying EDA complex formation between an electron acceptor and donor using UV-Vis spectroscopy [20].

Objective: To confirm and characterize EDA complex formation between 1,2-dinitrobenzene (acceptor) and tri-n-butylamine (donor) in acetonitrile.

Materials:

- Acceptor Solution: 1,2-Dinitrobenzene (0.01 M in acetonitrile). Note: Purify via column chromatography for pale-yellow pure reagent.

- Donor Solution: Tri-n-butylamine (0.01 M in acetonitrile).

- Solvent Control: HPLC-grade acetonitrile.

- Equipment: UV-Vis spectrophotometer, 1 cm quartz cuvettes, adjustable-volume micropipettes.

Procedure:

- Baseline Correction: Place acetonitrile in both sample and reference cuvettes and record a baseline spectrum from 800 nm to 350 nm.

- Individual Component Scans:

- Scan the acceptor solution (1,2-dinitrobenzene) against acetonitrile reference.

- Scan the donor solution (tri-n-butylamine) against acetonitrile reference.

- EDA Complex Formation:

- Prepare a solution containing equimolar amounts (e.g., 1 mL each) of donor and acceptor solutions in a clean vial.

- Incubate for 1 minute at room temperature.

- Transfer the mixture to a cuvette and scan against acetonitrile reference.

- Stoichiometry Determination (Job's Plot):

- Prepare a series of solutions with varying donor:acceptor ratios while keeping the total concentration constant.

- Measure absorbance at 490 nm for each ratio.

- Plot absorbance versus mole fraction of acceptor to determine optimal binding stoichiometry.

- Solvent Interference Test:

- Add 600 μL of water to the EDA complex solution, mix thoroughly, and record the spectrum.

Expected Outcomes: A successful experiment will show a significant bathochromic shift (red shift) and increased absorption in the visible region (400-500 nm) for the mixture compared to individual components, confirming EDA complex formation. Water addition should substantially decrease absorption intensity.

Protocol 2: Photoenzymatic Hydroamination via EDA Complex

This protocol describes a specific application of EDA complexes in photoenzymatic synthesis for the enantioselective synthesis of vicinal diamines, adapted from recent literature [4].

Objective: To achieve enantioselective hydroamination of enamides using a dual bio-/photo-catalytic system that generates N-centered radicals via EDA complex photoactivation.

Materials:

- Enzyme: GluER-T36A-Y177F-F269V-K277M-Y343F mutant (ER-M5, 1 mol%)

- Cofactor System: Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), NADP+, D-glucose

- Photocatalyst: Rhodamine B (RhB)

- Substrates: N-(1-phenylvinyl)acetamide (1a), N-amidopyridinium salt (2a)

- Solvent: Phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5)/acetonitrile (4:1)

- Light Source: Green LEDs (530-540 nm)

- Equipment: Schlenk tube, LED photoreactor, inert atmosphere capability

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- In a dried Schlenk tube, add N-(1-phenylvinyl)acetamide (0.1 mmol) and N-amidopyridinium salt (0.15 mmol).

- Add Rhodamine B (2 mol%) and the ER-M5 enzyme (1 mol%).

- Add the cofactor system: NADP+ (0.5 mM), GDH (2 mg), D-glucose (10 equiv).

- Add phosphate buffer/acetonitrile solvent mixture (2 mL total volume).

- Degassing:

- Freeze the reaction mixture using liquid N₂.

- Evacuate the Schlenk tube under high vacuum.

- Backfill with argon.

- Repeat freeze-pump-thaw cycle three times.

- Photoreaction:

- Place the Schlenk tube in a green LED photoreactor (530-540 nm).

- Stir vigorously at 25°C for 24-48 hours.

- Reaction Monitoring:

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS.

- Determine enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC or SFC after purification.

- Work-up and Purification:

- Extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL).

- Combine organic layers, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate.

- Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography.

- Reaction Setup:

Expected Outcomes: The reaction should provide enantioenriched vicinal diamine products with excellent enantioselectivity (up to >99% ee) and good yields (up to 82%). Control experiments should confirm the essential role of light, enzyme, and the EDA complex in the transformation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for experimental work with EDA complexes in photoenzymatic synthesis.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for EDA Complex Photoenzymatic Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Electron Acceptors | Forms EDA complex with electron donors; generates radical anions upon SET | Aryl halides [18], Katritzky salts [18], 1,2-dinitrobenzene [20], nitroaromatics [20] |

| Electron Donors | Provides electrons in EDA complex; generates radical cations upon SET | Thiophenols [18], tertiary amines [20], enolates [19], dithiocarbamate anions [18] |

| Enzyme Biocatalysts | Provides chiral environment for enantioselective radical transformation | Ene-reductases (EREDs) [19] [4], flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductases [19], GluER mutants [4] |

| Cofactor Systems | Regenerates reduced enzyme form for catalytic turnover | Glucose/GDH/NADP+ [4], flavin mononucleotide (FMN) [19] |

| Photoredox Catalysts | Enhances radical generation in synergistic systems; absorbs specific wavelengths | Rhodamine B (green light) [4], organic dyes [4] |

| Spectroscopic Probes | Detects reactive species generated from EDA complexes | Dihydroethidium (DHE, superoxide detection) [20], DCFH (ROS detection) [20] |

Advanced Applications in Synthesis

Workflow for Dual Bio-/Photo-Catalytic System

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow of a synergistic photo-/biocatalytic system where an EDA complex and an enzyme operate concurrently to achieve enantioselective transformations.

Key Applications and Performance Metrics

Recent research has demonstrated several innovative applications of EDA complexes in synthetic chemistry, particularly in challenging transformations.

Table 3: Advanced Synthetic Applications of EDA Complex Photochemistry

| Application | Reaction System | Key Performance Metrics | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aerobic Oxygenation | 1,2-Dinitrobenzene/tertiary amine EDA complex [20] | Converts boronic acids to phenols using O₂; 5 mol% acceptor loading; functional group tolerance | Overcomes traditional oxygen sensitivity of EDA complexes; enables superoxide generation |

| C–S Bond Formation | Thiophenol/aryl halide EDA complex [18] | Metal-free thioether synthesis; mild conditions; no catalyst required | Sustainable methodology for pharmacologically relevant C–S bonds |

| Enantioselective Hydroamination | ERED/Rhodamine B dual system [4] | Up to >99% ee; 82% yield; broad substrate scope | Demonstrates simultaneous control of chemo-, enantio-, and substrate selectivity |

| Triple Selectivity Control | Flavoprotein GkOYE-G7 [19] | >90% enantiomeric excess; predictable substrate scope | Reveals reaction-level rather than binding-based control mechanisms |

Radicals are highly reactive, short-lived chemical species that typically react indiscriminately with biological materials, posing a significant challenge for their use in selective synthesis. Despite this inherent reactivity, nature has evolved thousands of enzymes that employ radicals to catalyze thermodynamically challenging reactions essential to life. The fundamental challenge in harnessing these reactive intermediates lies in controlling their reactivity to achieve specific synthetic outcomes, particularly stereoselective transformations. Traditional chemical approaches often struggle with this control, leading to racemic mixtures or unwanted side reactions. Photoenzymatic catalysis has emerged as a powerful strategy to address this challenge, integrating the reactivity of photogenerated radicals with the exquisite stereocontrol of enzymatic environments to achieve unprecedented selectivity in asymmetric synthesis.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Enzymatic Radical Control

Electronic Control through SOMO-HOMO Inversion

Enzymes employ sophisticated quantum mechanical effects to modulate radical reactivity. Research on B12-dependent radical enzymes (glutamate mutase and methylmolonyl-Co-A mutase) has revealed a novel control mechanism involving non-Aufbau electronic structures. In these systems, the 5'-deoxyadenosyl (Ado•) radical exhibits SOMO-HOMO inversion (SHI), where the singly occupied molecular orbital (SOMO) is lower in energy than the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) [21].

This electronic phenomenon is not merely a curiosity but serves a critical regulatory function. The magnitude of SHI is modulated through Coulombic interactions between the radical and a conserved glutamate residue (Glu-) within the active site. When the Ado• radical is first formed, hydrogen bonding with Glu- is minimal, resulting in more pronounced SHI and consequently lower reactivity. As the radical migrates toward the substrate (up to 8 Å), stronger hydrogen bonding with Glu- occurs, leading to less pronounced SHI and increased reactivity by 1-3 orders of magnitude [21]. This precise electronic tuning allows the enzyme to maintain control over the highly reactive radical intermediate throughout its catalytic journey.

Steric Control through Active Site Engineering

Beyond electronic effects, enzymes utilize precisely engineered binding pockets to enforce stereocontrol through spatial constraints. In photo-enzymatic cascade reactions for synthesizing α-functionalized phenylpyrrolidines, the binding pocket of engineered VHbCH carbene transferase provides a stable reaction environment that enhances enantioselectivity. Computational studies have confirmed that active pocket repositioning plays a critical role in stereoselective regulation, with the engineered enzyme achieving exceptional stereoselectivity (up to 99% ee) [22].

Similarly, in the asymmetric synthesis of hydroxysulfone compounds, engineering the substrate binding region of ketoreductase from Lactobacillus kefir (LkKRED) involved mutating residues within 5 Å of the substrate binding pocket. Residues S96, L153, and Y190 were identified as critical for stereocontrol, with the Y190S/S96T double variant achieving 99% yield and 99% ee by reducing steric hindrance and optimizing substrate orientation within the binding pocket [23].

Table 1: Performance of Engineered Enzymes in Stereoselective Radical Reactions

| Enzyme | Reaction Type | Modification | Yield (%) | Enantiomeric Excess (ee%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Engineered SD-VHbCH carbene transferase | Photo-enzymatic C–H functionalization | Active pocket repositioning | N/R | 99% |

| LkKRED (Y190S/S96T variant) | Ketosulfone reduction | Semi-rational design of binding pocket | 99% | 99% |

| Wild-type LkKRED | Ketosulfone reduction | None | 7% | 71% |

N/R: Not reported in the sourced context

Experimental Protocols for Photo-Enzymatic Radical Reactions

Protocol 1: One-Pot Photo-Enzymatic Cascade for α-Functionalized Phenylpyrrolidine Synthesis

Principle: This protocol integrates a light-driven C–N cross-coupling reaction with biocatalytic carbene transfer to achieve enantioselective C(sp³)–H functionalization of saturated N-heterocyclic scaffolds [22].

Materials:

- Aryl bromides (various derivatives)

- Cyclic secondary amines

- Dual nickel/photoredox catalyst (Ni/PC)

- Engineered SD-VHbCH carbene transferase (whole-cell system)

- DMSO solvent

- Blue LED light source

- Inert atmosphere (argon or nitrogen)

Procedure:

- Photocatalytic Cross-Coupling:

- Charge a dried reaction vessel with aryl bromide (1.0 equiv), cyclic secondary amine (1.2 equiv), and Ni/PC catalyst (5 mol% each).

- Add anhydrous DMSO (0.1 M concentration relative to aryl bromide) under inert atmosphere.

- Irradiate with blue LEDs (450 nm) at room temperature for 12-24 hours with vigorous stirring.

- Monitor reaction completion by TLC or LC-MS.

Biocatalytic Carbene Transfer:

- Without intermediate purification, add the engineered SD-VHbCH whole-cell biocatalyst (20 mg/mL final concentration) directly to the reaction mixture.

- Add additional cofactors as required (specific composition may vary based on enzyme engineering).

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking at 200 rpm for 6-12 hours.

- Monitor enantioselectivity by chiral HPLC or SFC.

Workup and Purification:

- Extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 50 mL).

- Combine organic layers, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

- Purify the crude product by flash chromatography on silica gel.

- Analyze enantiomeric excess by chiral stationary phase HPLC.

Critical Notes:

- Maintain strict anaerobic conditions during the photocatalytic step to prevent catalyst deactivation.

- The one-pot nature avoids purification of reactive intermediates, minimizing decomposition pathways.

- Enzyme performance may vary with batch; preliminary activity assays are recommended.

Protocol 2: Photo-Biocatalytic Asymmetric Hydroamination

Principle: This protocol employs flavin-dependent ene-reductases to generate and control aminium radical cations for asymmetric intermolecular hydroamination, addressing a long-standing challenge in chemical synthesis [24].

Materials:

- Hydroxylamine precursor (alkyl-derived)

- Olefin substrate

- Flavin-dependent ene-reductase

- NAD(P)H cofactor (regeneration system optional)

- Phosphate buffer (pH 7.0)

- Visible light source (blue or green LEDs)

- Photoreactor with temperature control

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup:

- Prepare a solution of hydroxylamine precursor (1.0 equiv) and olefin substrate (1.5 equiv) in potassium phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.0).

- Add purified ene-reductase or whole-cell biocatalyst (10 mg/mL final concentration).

- Include NADPH (0.5 mM) or NADH with regeneration system as required.

Photoirradiation:

- Transfer the reaction mixture to a photochemical reactor with temperature control.

- Irradiate with visible light (appropriate wavelength for enzyme photochemistry) at 25°C with stirring.

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC, GC, or LC-MS.

Enantioselective Hydroamination:

- The enzyme catalyzes both photogeneration of the aminium radical cation and enantioselective hydrogen atom transfer.

- Continue irradiation until complete consumption of starting material (typically 8-24 hours).

Product Isolation:

- Extract reaction mixture with ethyl acetate or dichloromethane (3 × volume).

- Dry combined organic layers over anhydrous MgSO₄.

- Concentrate under reduced pressure and purify by flash chromatography.

- Determine enantiomeric purity by chiral HPLC or GC.

Critical Notes:

- Enzyme selection is critical; different ene-reductases may yield opposite stereoselectivities.

- Light intensity should be optimized to balance radical generation with enzyme stability.

- Control experiments without light or enzyme confirm the photo-biocatalytic nature.

Visualization of Enzymatic Radical Control Mechanisms

SOMO-HOMO Inversion in Radical Enzyme Control

Diagram 1: Radical migration and reactivity modulation via SHI in B12 enzymes. SHI: SOMO-HOMO inversion [21].

Integrated Photo-Biocatalytic Cascade Workflow

Diagram 2: Integrated workflow for photo-biocatalytic radical taming [22] [23] [24].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents for Photo-Enzymatic Radical Reactions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Engineered Carbene Transferases (e.g., SD-VHbCH) | Stereoselective functionalization of C-H bonds | α-Functionalized phenylpyrrolidine synthesis [22] |

| Flavin-Dependent Ene-Reductases | Photogeneration and control of aminium radical cations | Asymmetric hydroamination [24] |

| Engineered Ketoreductases (e.g., LkKRED variants) | Stereoselective reduction of prochiral ketones | Hydroxysulfone synthesis [23] |

| Dual Nickel/Photoredox Catalyst (Ni/PC) | Light-driven C–N cross-coupling | In situ generation of N-heterocyclic scaffolds [22] |

| Ru(II) Photocages | Light-triggered enzyme inhibition with spatial control | Precise modulation of CYP enzyme activity [25] |

| NAD(P)H Cofactors | Redox equivalents for enzymatic catalysis | Ketoreductase-mediated asymmetric reductions [23] |

| Blue/Green LED Systems | Energy source for photochemical steps | Radical generation in photocatalytic steps [22] [23] |

The integration of photochemistry with enzymatic catalysis represents a paradigm shift in asymmetric synthesis, particularly for controlling highly reactive radical intermediates. Through sophisticated mechanisms like SOMO-HOMO inversion and precisely engineered active sites, enzymes can tame these fleeting species to achieve exceptional stereocontrol. The experimental protocols and tools outlined herein provide researchers with practical approaches to implement these strategies for synthesizing valuable chiral building blocks. As protein engineering capabilities advance and our understanding of radical enzymology deepens, this synergistic approach will undoubtedly expand to encompass an even broader range of transformations, further solidifying its role in sustainable pharmaceutical synthesis and green manufacturing.

Synthetic Applications: Building Complex Chiral Molecules

Synthesis of Fluorinated Amides with Remote Stereocenters

The incorporation of fluorine atoms into organic molecules, particularly amides, is a powerful strategy in modern medicinal chemistry and drug development. Fluorinated amides serve as prevalent structural motifs in pharmaceuticals and bioactive molecules, with over 50% of modern pharmaceuticals containing fluorine by 2023 [5]. The introduction of fluorine can significantly alter a compound's physical properties, metabolic stability, and biological activity due to fluorine's high electronegativity and favorable biocompatibility [5]. However, the enantioselective synthesis of these compounds, especially those bearing challenging remote stereocenters, remains a significant challenge for synthetic chemists [5] [26].

This Application Note focuses specifically on photoenzymatic strategies for synthesizing fluorinated amides with remote stereocenters, highlighting recent breakthroughs in enzyme catalysis that overcome previous limitations in stereocontrol. These methodologies provide sustainable and efficient approaches to access valuable fluorinated building blocks for drug development programs.

Photoenzymatic Enantioselective Synthesis

Ene-Reductase Catalyzed Hydroalkylation

A groundbreaking visible-light-driven ene-reductase system has been developed for the enantioselective synthesis of α-fluorinated amides with distal chirality. This system utilizes flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductases (ERs) to generate carbon-centered radicals from fluorine-containing brominated amides under blue light irradiation, enabling their enantioselective hydroalkylation with alkenes [5].

Key Reaction Components:

- Catalyst: Ene-reductases (OYE1, OYE2, OYE3, XenA, XenB)

- Cofactor System: Flavin mononucleotide (FMN), glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), D-(+)-glucose, NADP+

- Light Source: Blue LED (455-465 nm)

- Radical Precursor: Fluorine-containing brominated amides (e.g., F-1)

- Coupling Partners: Electron-deficient alkenes

Table 1: Optimization of Reaction Parameters for Photoenzymatic Hydroalkylation

| Parameter | Initial Condition | Optimized Condition | Impact on Yield/ee |

|---|---|---|---|

| Light Source | 12 W, 455 nm | 45 W, 465 nm | Yield increased from 15% to 21% |

| Buffer System | Sodium phosphate (NaPi) | Tris-HCl (pH 8.5) | Yield increased ~1.7 times |

| Enzyme Loading | Baseline | 2 mol% OYE1 | Yield increased to 51% |

| Enzyme Variant | Wild-type OYE1 | Y375F mutant | Yield >90% with maintained ee >90% |

The reaction optimization demonstrated that alkaline conditions (Tris-HCl, pH 8.5) and increased enzyme loading significantly improved reaction efficiency. Through systematic enzyme engineering, the Y375F mutation was identified as crucial for enhancing yield while maintaining excellent enantioselectivity [5].

Experimental Protocol

Procedure for Photoenzymatic Hydroalkylation of Fluorinated Amides:

Reaction Setup: In a 5 mL reaction vial, add the following components:

- Fluorinated bromoamide substrate F-1 (0.1 mmol, 1.0 equiv)

- Alkene coupling partner (0.12 mmol, 1.2 equiv)

- Selected ene-reductase (2 mol%)

- FMN (0.5 mol%)

- NADP+ (0.5 mol%)

- GDH (2 mg)

- D-(+)-glucose (5.0 equiv)

- Tris-HCl buffer (2.0 mL, 50 mM, pH 8.5)

Photoreaction: Seal the vial and irradiate with blue LEDs (45 W, 465 nm) with continuous stirring for 24-48 hours at 25°C.

Reaction Monitoring: Monitor reaction progress by TLC or GC-MS until complete consumption of the starting material is observed.

Workup: Extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL), combine organic layers, dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄, and concentrate under reduced pressure.

Purification: Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography on silica gel to obtain the desired fluorinated amide with remote stereocenter.

Analysis: Determine enantiomeric excess by chiral HPLC or SFC analysis.

This protocol has been successfully applied to synthesize diversified α-fluorinated amides with high yields (up to 91%) and excellent distal chirality (up to 97% enantiomeric excess) [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Photoenzymatic Fluorinated Amide Synthesis

| Reagent/Enzyme | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ene-reductases (OYE1) | Catalyzes enantioselective radical addition | Y375F mutant shows enhanced activity |

| Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN) | Photosensitizer and redox cofactor | Enables radical generation under light |

| Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH) | Cofactor regeneration system | Maintains NADPH levels for sustained catalysis |

| α-Fluorinated Bromoamides | Radical precursors | Amide group crucial for enzyme binding and reactivity |

| Tris-HCl Buffer (pH 8.5) | Reaction medium | Alkaline conditions enhance reaction efficiency |

| Blue LED Light Source | Radical initiation | 45W, 465nm optimal for excitation |

Reaction Mechanism and Workflow

The photoenzymatic mechanism involves a sophisticated interplay between light absorption, radical generation, and enantioselective bond formation within the enzyme active site.

Diagram 1: Photoenzymatic Reaction Mechanism

The catalytic cycle begins with blue light absorption by the flavin cofactor, generating an excited state that initiates single electron transfer to the fluorinated bromoamide substrate. This process generates a carbon-centered radical that adds to the alkene coupling partner. The resulting radical intermediate undergoes enantioselective hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) within the enzyme active site, where precisely positioned amino acid residues control the stereochemical outcome at the remote center [5].

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow

Comparative Analysis and Applications

The photoenzymatic approach represents a significant advancement over traditional methods for synthesizing fluorinated amides with remote stereocenters. Conventional strategies often relied on stoichiometric chiral auxiliaries or faced limitations in controlling remote stereochemistry [27]. The enzyme-based system provides exceptional control over stereoselectivity while operating under mild, environmentally friendly conditions.

Key Advantages:

- High Enantioselectivity: Up to 97% ee for γ-stereocenters relative to fluorine

- Broad Substrate Scope: Accommodates various fluorinated amides and alkene coupling partners

- Sustainability: Utilizes visible light as energy source and operates at ambient temperature

- Tunability: Enzyme engineering enables optimization for specific substrates

This methodology has significant implications for drug discovery, particularly in accessing chiral fluorinated 3D molecules that exhibit enhanced biological activity, metabolic stability, and membrane permeability – critical properties for pharmaceutical development [26]. The ability to precisely install fluorine atoms at internal positions with controlled stereochemistry enables medicinal chemists to fine-tune molecular properties while maintaining three-dimensional complexity.

Intermolecular Radical Hydroamination for Chiral Amine Synthesis

The synthesis of chiral amines, which are pivotal structural motifs in pharmaceuticals, agrochemicals, and natural products, represents a central challenge in modern organic chemistry. Intermolecular radical hydroamination offers a powerful, atom-economical route to construct these valuable scaffolds directly from simple alkenes and amine precursors. However, controlling the reactivity of transient radical intermediates and achieving high levels of enantioselectivity has been a long-standing obstacle. Traditional catalytic systems struggle to suppress deleterious side reactions, such as α-deprotonation and hydrogen atom abstraction, which compete with the desired pathway [28].

Photoenzymatic catalysis has emerged as a transformative platform to address these challenges. By repurposing natural enzymes, particularly flavin-dependent 'ene'-reductases (EREDs), chemists can now generate and harness highly reactive nitrogen-centered radicals under mild conditions. This approach leverages the enzyme's innate chiral environment to enforce enantioselectivity, enabling asymmetric intermolecular hydroamination reactions that were previously inaccessible. This Application Note details the experimental protocols and mechanistic insights for implementing this cutting-edge methodology, contextualized within the broader thesis of advancing photoenzymatic enantioselective synthesis.

Core Principles and Mechanistic Insights

The Catalytic Cycle

The photoenzymatic hydroamination mechanism involves a carefully orchestrated sequence of steps within the enzyme's active site, centered on the flavin mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor.

The mechanism initiates with photoexcitation of the reduced flavin mononucleotide (FMNH⁻) to FMNH⁻*, a potent reductant. This excited species transfers an electron to a nitrogen-containing precursor, typically featuring a labile N–O bond (e.g., a hydroxylamine derivative with a phenolate leaving group). This transfer triggers homolytic cleavage to generate an aminium radical cation (ARC). This electrophilic radical adds across the alkene substrate, forming a new C–N bond and a carbon-centered radical. Finally, the enzyme mediates an enantioselective hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) from the flavin semiquinone (FMNH•) to this nascent radical, furnishing the enantioenriched amine product and regenerating the oxidized FMN cofactor, which is subsequently reduced by the NADPH/glucose dehydrogenase (GDH) regeneration system [3].

Advantages of the Photoenzymatic System

- > Unprecedented Enantiocontrol: The confined chiral pocket of the ene-reductase exerts exquisite control over the hydrogen atom transfer step, leading to high enantiomeric excess (ee), often exceeding 90% and reaching up to 99% in optimized systems [3] [22].

- > External Photocatalyst-Free: Unlike many radical hydroamination methods, the flavin cofactor acts as the internal photocatalyst, simplifying the reaction mixture and purifying the product [3].

- > Mild Reaction Conditions: Reactions proceed efficiently at room temperature under visible light irradiation in aqueous or mixed aqueous-organic buffers, compatible with a range of functional groups [5] [3].

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues the essential reagents and materials critical for setting up a photoenzymatic hydroamination reaction.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents for Photoenzymatic Hydroamination

| Reagent/Material | Function/Role | Key Details & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ene-Reductase (ERED) | Biocatalyst; Provides chiral environment & flavin cofactor. | XenB from Pseudomonas putida; OYE1; Engineered variants (e.g., XenB-W100L, XenB-A232F) for improved performance [3]. |

| Flavin Cofactor (FMN) | Internal photosensitizer & redox mediator. | Flavin Mononucleotide (FMN); recycled in situ by NADPH [3]. |

| Cofactor Regeneration System | Sustains catalytic cycle by reducing FMN. | NADP⁺/Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH)/D-Glucose; maintains supply of FMNH⁻ [5] [3]. |

| Nitrogen Radical Precursor | Source of the aminium radical cation (ARC). | Hydroxylamines with phenolate leaving groups (e.g., 4-cyanophenolate). Carbamates for protected primary amines [3]. |

| Alkene Substrate | Radical acceptor for C–N bond formation. | Electron-rich alkenes (e.g., ɑ-methyl styrene derivatives); regioselectivity is anti-Markovnikov due to electrophilic ARC [3] [29]. |

| Reaction Buffer | Aqueous reaction medium with controlled pH. | Tris-HCl (pH ~8.5) or Imidazole (pH ~6.5); optimal pH is enzyme and substrate-dependent [5] [3]. |

Quantitative Performance Data

The performance of photoenzymatic hydroamination has been quantitatively demonstrated across a broad range of substrates. The data below summarizes key metrics for yield and enantioselectivity.

Table 2: Performance Summary of Photoenzymatic Hydroamination [28] [5] [3]

| Substrate Class | Example Structure | Representative Yield (%) | Representative ee (%) | Optimal Enzyme |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protected Aliphatic Amines | N-Carbamyl pyrrolidines & piperidines | 25 – 88 | 93 – 97 | XenB-A232L (E2) [3] |

| Aromatic Alkenes | para-Substituted styrenes | 50 – 96 | 88 – 97 | XenB-A232L (E2) [3] |

| Fluorinated Amides | α-Difluoroamides | Up to 91 | Up to 97 | OYE1-Y375F [5] |

| Heteroaryl Amines | Aminopyrimidines & Aminopyridines | 57 – 89* | N/A* | [Ir-B]OTf (Chemical PC) [29] |

| Sulfonamides | Aryl & Alkyl Sulfonamides | Up to 97* | N/A* | [Ir-A]OTf/[Ir-B]OTf (Chemical PC) [30] |

Note: Reactions for Heteroaryl Amines and Sulfonamides typically employ synthetic iridium photocatalysts ([Ir-A]OTf, [Ir-B]OTf) and proceed with excellent anti-Markovnikov selectivity, but enantioselectivity is not reported for the racemic versions shown here. Yields are high, demonstrating the robustness of the radical mechanism [29] [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Photoenzymatic Hydroamination Using Evolved Ene-Reductase

This protocol describes the intermolecular hydroamination between carbamate 1a and ɑ-methyl styrene using an evolved XenB variant (E2, XenB-A232L) to produce chiral amine 3a in high yield and enantioselectivity [3].

Materials:

- Enzyme: Purified XenB-A232L mutant (E2) lyophilized powder [3].

- Cofactors: NADP⁺ (disodium salt), FMN (disodium salt).

- Regeneration System: Glucose Dehydrogenase (GDH, from Pseudomonas sp.), D-(+)-Glucose.

- Substrates: Hydroxylamine precursor 1a (e.g., with 4-cyanophenolate leaving group), ɑ-methyl styrene.

- Solvents & Buffers: Imidazole buffer (1.0 M, pH 6.5), deionized water.

Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 4 mL clear glass vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar, combine the following:

- Imidazole Buffer (1.0 M, pH 6.5): 200 µL (Final conc. 100 mM)

- NADP⁺ (10 mM stock in H₂O): 50 µL (Final 0.1 mM)

- FMN (5 mM stock in H₂O): 20 µL (Final 0.02 mM)

- D-Glucose (1.0 M stock in H₂O): 50 µL (Final 100 mM)

- GDH (5 mg/mL stock in buffer): 20 µL (∼2.5 U)

- Substrate 1a (0.1 M stock in DMSO): 50 µL (0.005 mmol, 1.0 equiv)

- ɑ-Methyl styrene (0.1 M stock in DMSO): 150 µL (0.015 mmol, 3.0 equiv)

- Deionized H₂O: 450 µL

- Enzyme XenB-A232L (E2, from 10 µM stock in buffer): 50 µL (2 mol%)

Initiation and Irradiation:

- Cap the vial and place it on a magnetic stirrer.

- Irradiate the reaction mixture with a blue LED strip (∼465 nm, 45 W) positioned approximately 5 cm from the vial.

- Stir the reaction vigorously at room temperature (25 °C) for 16-24 hours.

Work-up:

- Quench the reaction by adding saturated aqueous NaCl solution (1 mL).

- Extract the aqueous mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 2 mL).

- Combine the organic extracts and dry over anhydrous MgSO₄.

- Filter and concentrate the organic layer under reduced pressure.

Purification and Analysis:

- Purify the crude residue by flash column chromatography on silica gel.

- Analyze the enantiomeric purity of the product 3a by chiral HPLC or GC.

- Expected Outcome: The product 3a can be obtained in 88% yield and 93% ee [3].

Application Notes for Drug Development

- Handling Sensitive Intermediates: Nitrogen radical precursors, especially those with N–O bonds, can be sensitive to heat and light. Store stock solutions in the dark at -20 °C and prepare them fresh weekly. Reactions should be set up in low-actinic glassware if available.

- Optimization and Scale-up: For new substrate combinations, a brief optimization of pH (testing buffers from pH 6.0-9.0) and enzyme loading (1-5 mol%) is recommended. The reaction has been successfully demonstrated on gram-scale, showing robust performance for potential industrial application [3].

- Analytical Techniques: Monitor reaction progress by TLC or LC-MS. Determine enantiomeric excess (ee) using Chiral Stationary Phase HPLC or GC. Absolute configuration can be assigned by comparing optical rotation with literature values or via X-ray crystallography of derivative compounds.

Biosynthesis of Chiral Vicinal Diamines via Dual Catalysis

Chiral vicinal diamines are fundamental structural motifs found in numerous natural products, pharmaceuticals, and chiral ligands or auxiliaries for asymmetric catalysis [4]. Despite their importance, the catalytic enantioselective synthesis of these molecules, particularly via direct hydroamination of enamines, remains a significant challenge [4]. Traditional chemical methods often rely on transition metal complexes or chiral phosphoric acids via two-electron electrophilic pathways [4]. In recent years, photoenzymatic catalysis has emerged as a powerful strategy to address enantioselectivity challenges associated with photoinduced radical reactions, combining the remarkable stereocontrol of enzymes with the versatile reactivity of photocatalysts [4] [31]. This application note details a novel dual bio-/photo-catalytic system for achieving enantioselective hydroamination of enamines, providing researchers with robust protocols for synthesizing valuable chiral vicinal diamines with exceptional stereochemical control.

Experimental Protocols

Dual Photo-/Bio-Catalytic System for Enantioselective Hydroamination

This protocol describes the synergistic use of an ene-reductase (ERED) and an organic photocatalyst for the enantioselective synthesis of vicinal diamines via nitrogen-centered radical (NCR) hydroamination [4].

Reagents and Materials

- Enzyme: GluER-T36A-Y177F-F269V-K277M-Y343F (ER-M5) mutant [4]

- Photocatalyst: Rhodamine B (RhB) [4]

- NCR Precursor: N-amidopyridinium salt (e.g., 2a) [4]

- Radical Acceptor: N-(1-phenylvinyl)acetamide (e.g., 1a) [4]

- Cofactor Regeneration System: Glucose dehydrogenase (GDH), NADP+, D-glucose [4]

- Solvent: Phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5) or other appropriate aqueous buffer [4]

- Light Source: Green LEDs (530-540 nm) [4]

Procedure

Reaction Setup: In a 4 mL glass vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar, combine the following components sequentially:

- Phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5, final volume 1 mL)

- N-(1-phenylvinyl)acetamide 1a (0.05 mmol, 1.0 equiv)

- N-amidopyridinium salt 2a (0.075 mmol, 1.5 equiv)

- Rhodamine B (2 mol%)

- ER-M5 enzyme (1 mol%)

- GDH (5 mg/mL), NADP+ (0.5 mM), and D-glucose (10 mM)

Reaction Conditions:

- Seal the vial with a septum and place it 5 cm from a green LED array (530-540 nm)

- Stir the reaction mixture at 25°C for 24-48 hours

- Monitor reaction progress by TLC, HPLC, or LC-MS

Workup and Purification:

- After completion, extract the reaction mixture with ethyl acetate (3 × 5 mL)

- Combine the organic layers and dry over anhydrous Na₂SO₄

- Concentrate under reduced pressure

- Purify the crude product by flash column chromatography (silica gel, hexane/ethyl acetate) to afford the desired vicinal diamine product (S)-3a

Analysis

- Yield: 72% isolated yield [4]

- Enantiomeric Excess: 98% ee (determined by chiral HPLC) [4]

- Absolute Configuration: (S) (assigned by single-crystal X-ray diffraction) [4]

Key Optimization Strategies

The development of this protocol involved critical optimization of several parameters to achieve high yield and enantioselectivity:

- Enzyme Engineering: Site-directed mutagenesis of native GluER created the quintuple mutant ER-M5 (T36A-Y177F-F269V-K277M-Y343F) with enhanced activity and selectivity [4]

- Photocatalyst Screening: Rhodamine B was identified as the optimal photocatalyst for generating NCRs under green light excitation [4]

- Wavelength Optimization: Green light (530-540 nm) provided better compatibility with the biological system and reduced side reactions compared to blue or UV light [4]

- Cofactor Regeneration: The GDH/glucose/NADP+ system maintained efficient flavin reduction throughout the reaction [4]

Data Presentation

Substrate Scope and Performance

Table 1: Substrate scope for the enantioselective hydroamination of enamides with N-amidopyridinium salts under optimized dual catalytic conditions [4]

| Product | R₁ Substituent | R₂ Substituent | Yield (%) | ee (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3a | H | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 72 | 98 |

| 3b | 2-OMe | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 78 | >99 |

| 3c | 3-OMe | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 82 | 98 |

| 3d | 4-F | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 65 | 97 |

| 3e | 4-Cl | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 68 | 97 |

| 3f | 4-Br | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 63 | 98 |

| 3g | 4-CF₃ | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 58 | 96 |

| 3h | 2-Naphthyl | 4-OMe-C₆H₄ | 45 | 90 |

| 3i | H | 4-Cl-C₆H₄ | 70 | 98 |

| 3j | H | 4-CN-C₆H₄ | 65 | 97 |

| 3k | H | 2-Thienyl | 62 | 96 |

Table 2: Key research reagent solutions for photoenzymatic diamine synthesis

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ERED Enzymes (GluER mutants, OYE1) [4] [5] | Enantioselective radical hydroamination and hydrogen atom transfer | Site-directed mutagenesis enhances activity and selectivity; FMN cofactor required |

| Organic Photocatalysts (Rhodamine B) [4] | Green light absorption and NCR generation from N-amidopyridinium salts | Enables radical initiation under biologically compatible conditions |

| N-Amidopyridinium Salts [4] | Nitrogen-centered radical (NCR) precursors | N-N bond cleavage under photochemical conditions generates amidyl radicals |

| Flavin Cofactors (FMN) [5] [4] | Natural photoenzyme cofactor | Participates in single-electron transfer processes and hydrogen atom transfer |

| Cofactor Regeneration System (GDH/Glucose/NADP+) [4] [5] | Sustained enzymatic activity by maintaining reduced flavin state | Essential for prolonged reaction efficiency and conversion |

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

Dual Catalytic Cycle Mechanism

Dual Catalytic Cycle: This diagram illustrates the synergistic mechanism between the photocatalyst (RhB) and the ene-reductase (ERED). The photocatalyst generates nitrogen-centered radicals under green light, which add to enamides. The ERED then controls the enantioselective hydrogen atom transfer to form the chiral diamine product, with the flavin cofactor (FMN) being continuously regenerated by the enzymatic reduction system [4].

Experimental Workflow for Photoenzymatic Diamine Synthesis

Experimental Workflow: This flowchart outlines the key steps in the photoenzymatic synthesis of chiral vicinal diamines, from reaction setup through irradiation, radical generation, enantioselective bond formation, and final product isolation and analysis. The dashed line indicates the simultaneous cofactor regeneration essential for maintaining enzymatic activity [4].

Discussion

The dual photo-/bio-catalytic system represents a significant advancement in asymmetric synthesis, addressing longstanding challenges in controlling highly reactive nitrogen-centered radicals for enantioselective bond formation [4]. The combination of ene-reductases with organic photocatalysts creates a synergistic platform that merges the exceptional stereocontrol of enzymes with the versatile radical generation capability of photoredox catalysis.

Key advantages of this methodology include:

- Exceptional Enantiocontrol: The enzyme active pocket provides a highly chiral environment for radical taming, achieving >99% ee in many cases [4]

- Mild Reaction Conditions: Green light irradiation and ambient temperature minimize substrate decomposition and enzyme denaturation [4]