High-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Variants: From Machine Learning to Functional Validation

This comprehensive review explores the cutting-edge methodologies and applications in high-throughput screening of enzyme variants, a critical tool in modern drug discovery and protein engineering.

High-Throughput Screening of Enzyme Variants: From Machine Learning to Functional Validation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the cutting-edge methodologies and applications in high-throughput screening of enzyme variants, a critical tool in modern drug discovery and protein engineering. We examine the foundational principles of HTS as a tool for running millions of biological tests rapidly, primarily in drug discovery processes to identify biologically relevant compounds. The article delves into innovative approaches including machine-learning guided cell-free platforms for engineering enzymes, structural determinants of variant effect predictability, and computational pre-screening methods. For researchers and drug development professionals, we provide practical troubleshooting guidance for common experimental challenges and detailed frameworks for functional validation and assay development. Finally, we present comparative analyses of different screening methodologies and their applications in green chemistry and biomedical research, offering insights into future directions for the field.

Understanding High-Throughput Screening: Foundations and Evolving Paradigms

High-throughput screening (HTS) represents a fundamental methodology in modern scientific discovery, enabling the rapid execution of millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests [1]. This approach has become indispensable in drug discovery and enzyme engineering, transforming how researchers identify active compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate specific biomolecular pathways [1]. In the context of enzyme variant research, HTS provides the technological foundation for directed evolution experiments, where identifying desired mutants from vast libraries represents the primary bottleneck [2]. The core principle of HTS lies in leveraging automation, miniaturization, and parallel processing to dramatically increase testing capacity while reducing reagent consumption and time requirements. Successful evolutionary enzyme engineering depends critically on having a robust HTS method, which significantly increases the probability of obtaining variants with desired properties while substantially reducing development time and cost [2].

Fundamental Principles and Scale of HTS

Core Principles

HTS operates on several interconnected principles that enable its remarkable throughput capabilities. Miniaturization is achieved through microtiter plates containing 96, 384, 1536, 3456, or even 6144 wells, dramatically reducing reaction volumes and reagent consumption [1]. Automation integrates robotic systems for plate handling, liquid transfer, and detection, enabling continuous operation with minimal human intervention [1]. Parallel processing allows simultaneous testing of thousands of compounds against biological targets, while sensitive detection methods capture subtle biological responses even in miniaturized formats [3].

The scale of HTS is categorized by daily screening capacity. Traditional HTS typically processes 10,000-100,000 compounds per day, while ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) exceeds 100,000 compounds daily [1]. Recent advances using drop-based microfluidics have demonstrated screening capabilities of 100 million reactions in 10 hours at one-millionth the cost of conventional techniques [1].

Quantitative Scale of HTS Operations

Table 1: HTS Scale and Corresponding Parameters

| Screening Scale | Throughput (Compounds/Day) | Well Formats | Volume Range | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard HTS | 10,000-100,000 | 96, 384, 1536 | 1-100 μL | Primary screening, enzyme engineering |

| uHTS | >100,000 | 1536, 3456, 6144 | 50 nL-5 μL | Large library screening, quantitative HTS |

| Microfluidic HTS | >1,000,000 | Droplet-based | Picoliter-nanoliter | Directed evolution, single-cell analysis |

HTS Experimental Workflow for Enzyme Variant Screening

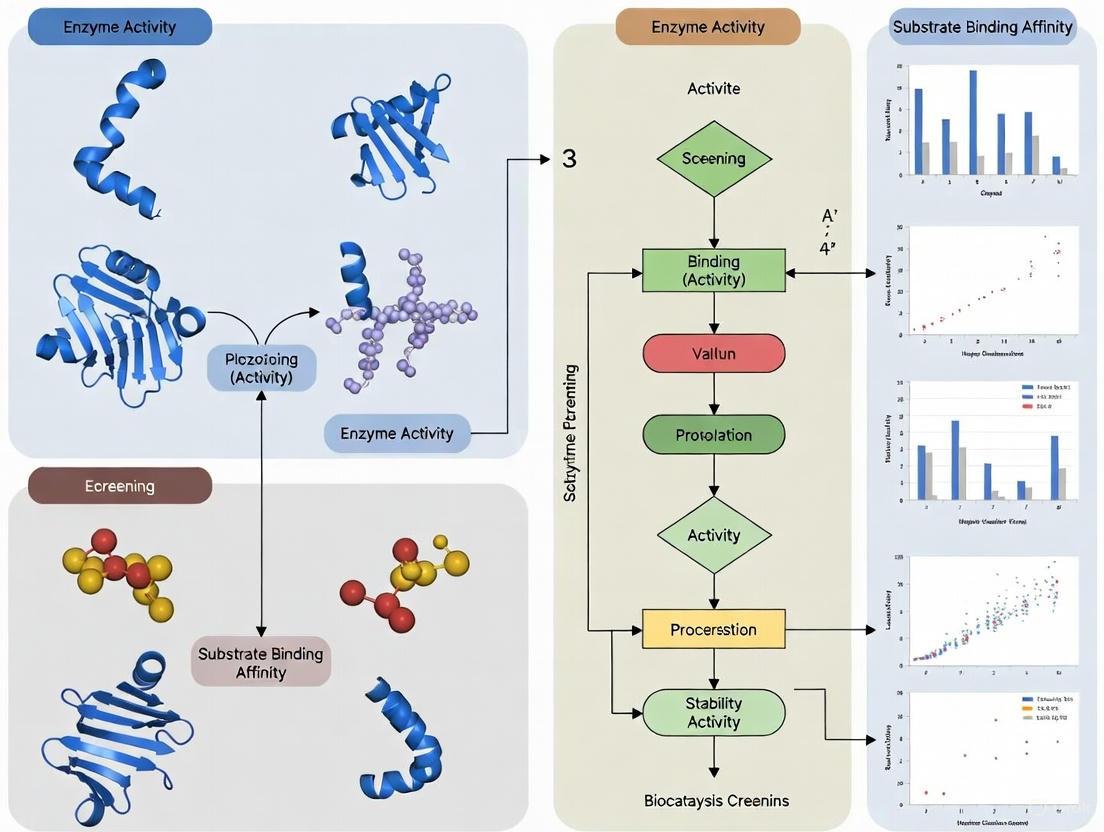

The following diagram illustrates the core HTS workflow for screening enzyme variants, integrating both computational and experimental components:

HTS Workflow for Enzyme Variant Screening

Library Generation and Computational Filtering

The process begins with creating diverse enzyme variant libraries. Recent advances integrate computational filtering to reduce experimental burden. For instance, structure-based filtering using AlphaFold-predicted models can narrow candidate sets from tens of thousands to manageable numbers [4]. In one case, structural similarity filtering reduced candidates from 15,405 to just 24 promising variants for experimental testing [4]. This computational pre-screening significantly enhances the probability of identifying functional enzymes.

Assay Preparation and Miniaturization

Assay plates are prepared by transferring nanoliter volumes from stock plates to empty microplates using automated liquid handling systems [1]. The biological entities (e.g., cells, enzymes) are then added to each well. For enzyme variant screening, this typically involves expressing target enzymes in host systems like E. coli and preparing cell extracts or purified proteins [5]. The miniaturized format allows testing thousands of conditions while conserving precious reagents.

Key HTS Methodologies for Enzyme Variant Research

Screening vs. Selection Approaches

HTS methods for enzyme engineering fall into two main categories: screening and selection. Screening involves evaluating individual variants for desired properties, while selection automatically eliminates nonfunctional variants by applying selective pressure [2]. Selection methods enable assessment of much larger libraries (exceeding 10^11 variants) but may miss subtle functional improvements [2].

Table 2: Comparison of HTS Methodologies for Enzyme Variants

| Methodology | Throughput | Key Features | Applications in Enzyme Engineering | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | 10^3-10^4 variants | Compatible with colorimetric/fluorometric assays; amenable to automation [2] | Enzyme activity assays, substrate specificity profiling [2] [3] | Limited by well number and volume requirements |

| Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) | Up to 30,000 cells/sec [2] | High-speed sorting based on fluorescent signals; compatible with surface display [2] [6] | Product entrapment assays, GFP-reporter systems, bond-forming enzymes [2] | Requires intracellular or surface-displayed signals [6] |

| In Vitro Compartmentalization (IVTC) | >10^7 variants [2] | Water-in-oil emulsion droplets as picoliter reactors; circumvents cellular regulation [2] | Oxygen-sensitive enzymes, directed evolution without transformation [2] | Compatibility challenges between transcription-translation and screening conditions [2] |

| Droplet-based Microfluidics | >1,000 variants/sec [6] | Pico-to-nanoliter droplets as microreactors; measures intra- and extracellular enzymes [6] | Hydrolases, oxidoreductases, isomerases screening [6] | Requires specialized equipment and optimization |

Detection and Signal Measurement Strategies

Detection methods vary based on the enzymatic reaction and assay design. Colorimetric or fluorometric assays are most convenient when substrates or products have distinguishable optical properties [2]. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) utilizes energy transfer between chromophores to study protein interactions and conformations [2]. Resonance energy transfer methods, including FRET, enable distance-dependent detection of enzymatic cleavage or conformational changes [2]. For example, FRET-based protease assays have achieved 5,000-fold enrichment of active clones in a single screening round [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Microtiter Plate-Based Screening for Enzyme Activity

This protocol adapts established methods for identifying active enzyme variants from directed evolution libraries [2] [3].

Materials:

- 384-well microtiter plates (clear bottom for absorbance/fluorescence readings)

- Automated liquid handling system

- Multichannel pipettes

- Plate reader capable of absorbance and fluorescence measurements

- Enzyme variants in cell lysates or purified form

- Enzyme-specific substrate solution

- Reaction buffer optimized for the target enzyme

- Positive control (wild-type enzyme)

- Negative control (heat-inactivated enzyme or empty vector lysate)

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Dispense 10-50 μL of each enzyme variant into designated wells using automated liquid handling. Include positive and negative controls in each plate.

- Reaction Initiation: Add substrate solution to each well to initiate reaction. Final reaction volumes typically range 20-100 μL.

- Incubation: Incubate plates at optimal enzyme temperature for a predetermined time (30 minutes to 2 hours).

- Signal Detection: Measure product formation using plate reader:

- For colorimetric assays: Read absorbance at appropriate wavelength

- For fluorometric assays: Read fluorescence with appropriate excitation/emission filters

- Data Collection: Export raw data for analysis, including well identifiers and signal intensities.

Quality Control:

- Calculate Z'-factor using positive and negative controls: Z' = 1 - [3×(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|]

- Accept assays with Z' > 0.5 for excellent robustness [3]

- Include replicate controls to assess intra-plate variability

Protocol 2: Computational Filtering of Enzyme Variants Prior to Experimental Screening

This protocol utilizes structural similarity filtering to reduce experimental burden, based on recently demonstrated approaches [5] [4].

Materials:

- Seed enzyme sequence in FASTA format

- Access to sequence databases (UniProt, SwissProt, TrEMBL)

- AlphaFold Protein Structure Database access

- Structural alignment software (TM-align)

- Sequence analysis tools (PSI-BLAST, CD-HIT)

Procedure:

- Sequence-Based Search:

- Perform PSI-BLAST search with seed sequence against protein databases

- Use e-value threshold of 10 and inclusion threshold of 0.001 for 4 iterations

- Cluster results with ≥99% identity using CD-HIT to generate non-redundant set

Sequence Length Filtering:

- Filter sequences based on length similarity to seed protein

- Remove sequences significantly longer or shorter than seed (e.g., ±30% length difference)

Structural Similarity Evaluation:

- Retrieve AlphaFold-predicted structures for candidate sequences

- For sequences without direct models, identify proxies with ≥95% sequence identity

- Perform pairwise structural alignment with seed using TM-align

- Calculate TM-score (0.5-1.0 indicates structural similarity) and seed coverage (≥70%)

Active Site Conservation Analysis:

- Map known active site residues from seed to candidate sequences

- Assess conservation of critical catalytic residues

- Select final candidates for experimental testing

Validation:

- This approach has demonstrated reduction from tens of thousands to dozens of candidates [4]

- Expected true positive rate: 50-150% improvement over random selection [5]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HTS of Enzyme Variants

| Reagent/Material | Function | Examples/Specifications | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Miniaturized reaction vessels | 96, 384, 1536-well formats; clear bottom for reading | Higher density formats reduce reagent costs but require more sophisticated handling [1] |

| Fluorescent Probes | Detection of enzyme activity | Fluorogenic substrates, FRET pairs, environment-sensitive dyes | Select based on excitation/emission spectra compatible with available detectors [2] [3] |

| Cell Surface Display Systems | Phenotype-genotype linkage | Yeast, bacterial, or mammalian display systems | Enables FACS-based screening of enzyme libraries [2] |

| Emulsion Reagents | Compartmentalization | Water-in-oil surfactants, oil phases | Critical for in vitro compartmentalization approaches [2] [6] |

| Universal Detection Reagents | Broad applicability | Transcreener ADP² Assay, coupled enzyme systems | Enable screening multiple enzyme targets with same detection method [3] |

| Robotic Liquid Handlers | Automation of liquid transfer | Integrated systems with plate hotels | Essential for processing thousands of compounds daily [1] |

| High-Sensitivity Detectors | Signal measurement | Plate readers, FACS instruments, microfluidic sorters | Determine lower limits of detection and dynamic range [1] [6] |

Data Analysis and Hit Selection

Quality Control Metrics

Robust data analysis begins with quality assessment. The Z'-factor is widely used: Z' = 1 - [3×(σp + σn) / |μp - μn|], where σp and σn are standard deviations of positive and negative controls, and μp and μn are their means [3]. Values of 0.5-1.0 indicate excellent assay quality [3]. Strictly standardized mean difference (SSMD) provides an alternative approach that is particularly valuable for assessing data quality in HTS assays [1].

Hit Selection Strategies

Hit selection methods depend on replication design. For screens without replicates, robust methods like z-score or SSMD are appropriate [1]. These approaches assume each compound has similar variability to negative controls. For confirmatory screens with replicates, t-statistics or SSMD with sample estimation directly quantify effect sizes while accounting for variability [1].

The following diagram illustrates the decision process for hit selection in enzyme variant screening:

Hit Selection Decision Process

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of HTS continues to evolve with several emerging trends. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being integrated with experimental HTS to improve hit rates and predict compound efficacy [3]. Quantitative HTS (qHTS) paradigms generate full concentration-response curves for entire compound libraries, providing richer pharmacological data [7] [1]. Microfluidic technologies are pushing throughput boundaries while reducing volumes to picoliter scales and costs by million-fold factors [1] [6]. 3D cell cultures and organoids are creating more physiologically relevant screening environments for enzyme targeting applications [3].

For enzyme variant research specifically, computational approaches like neural network-based sequence generation coupled with experimental validation are showing promise. Recent studies have developed computational filters that improve experimental success rates by 50-150% when screening generated enzyme sequences [5]. The integration of AlphaFold-predicted structures for candidate prioritization further enhances the efficiency of identifying functional enzyme variants from sequence space [4].

As these technologies mature, HTS capabilities will continue to expand, enabling more sophisticated screening campaigns and accelerating the discovery and engineering of novel enzyme variants for therapeutic and industrial applications.

The Role of HTS in Modern Drug Discovery and Enzyme Engineering

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) has become the cornerstone of modern drug discovery and enzyme engineering, serving as the primary force driving the transformation of these fields [7]. This paradigm enables researchers to rapidly test thousands to hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds or enzyme variants to identify candidates with desired biological activities or catalytic properties. The emergence of Quantitative HTS (qHTS) represents a significant advancement, allowing multiple-concentration experiments to be performed simultaneously, thereby generating rich concentration-response data for thousands of compounds and providing lower false-positive and false-negative rates compared to traditional single-concentration HTS approaches [7]. In enzyme engineering, the development of compatible HTS methods has become the most critical factor for success in directed evolution experiments, as these methods considerably increase the probability of obtaining desired enzyme properties while significantly reducing development time and cost [2].

Core HTS Methodologies in Enzyme Engineering

Screening vs. Selection Approaches

High-throughput strategies in enzyme engineering primarily fall into two categories: screening methods and selection methods. Screening refers to the evaluation of individual protein variants for a desired property, while selection automatically eliminates non-functional variants through applied selective pressure [2]. Although screening provides a comprehensive analysis of each variant, its throughput is inherently limited by the need to assess individual clones. Selection methods, by contrast, enable the assessment of vastly larger libraries (exceeding 10^11 variants) by directly eliminating unwanted variants, allowing only positive candidates to proceed to subsequent rounds of directed evolution [2].

Established HTS Platforms and Technologies

Several established platforms form the technological foundation of modern HTS campaigns in enzyme engineering:

2.2.1 Microtiter Plate-Based Screening The microtiter plate remains a fundamental tool for HTS, miniaturizing traditional test tubes into multiple wells (96, 384, 1536, or higher density formats) [2]. While the 96-well plate is the most widely used format, higher density plates continue to push the boundaries of throughput. Traditional enzyme activity assays can be performed in microtiter plates using colorimetric or fluorometric detection methods, with throughput dramatically improved through robotic automation systems [2]. Recent advancements include micro-bioreactor systems like the Biolector, which enables online monitoring of light scatter and NADH fluorescence signals to indicate different levels of substrate hydrolysis or NADH-coupled enzyme activity [2].

2.2.2 Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) FACS represents a powerful screening approach that sorts individual cells based on their fluorescent signals at remarkable speeds of up to 30,000 cells per second [2]. Key applications in enzyme engineering include surface display systems, in vitro compartmentalization, GFP-reporter assays, and product entrapment strategies. In product entrapment approaches, a fluorescent substrate that can traverse the cell membrane is converted to a product that becomes trapped inside the cell due to size, polarity, or chemical properties, enabling direct fluorescence-based sorting of active clones [2]. This method has identified glycosyltransferase variants with more than 400-fold enhanced activity for fluorescent selection substrates [2].

2.2.3 Cell Surface Display Technologies Cell surface display technologies fuse enzymes with anchoring motifs, enabling their expression on the outer surface of cells (including bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells) where they can directly interact with substrates [2]. This positioning makes the displayed enzymes readily accessible for screening procedures. When combined with FACS, these systems have achieved remarkable efficiencies, with one reported method enabling a 6,000-fold enrichment of active clones after a single round of screening [2].

2.2.4 In Vitro Compartmentalization (IVTC) IVTC utilizes water-in-oil emulsion droplets or double emulsion droplets to create artificial compartments that isolate individual DNA molecules, forming independent reactors for cell-free protein synthesis and enzyme reactions [2]. This approach circumvents the regulatory networks of in vivo systems and eliminates transformation bottlenecks, thereby removing limitations imposed by host cell transformation efficiency. Droplet microfluidic devices compartmentalize reactants into picoliter volumes, offering shorter processing times, higher sensitivity, and greater throughput than standard assays [2]. IVTC has successfully identified β-galactosidase mutants with 300-fold higher kcat/KM values than wild-type enzymes [2].

Table 1: Comparison of Major HTS Methodologies in Enzyme Engineering

| Method | Throughput | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microtiter Plates | Moderate (103-104 variants) | Compatibility with diverse assay types; well-established protocols | Limited by assay sensitivity and automation | Colorimetric/fluorometric enzyme assays; cell-based screening |

| FACS | High (up to 30,000 cells/sec) | Extreme speed; quantitative selection | Requires fluorescent signal generation | Product entrapment; surface display screening; GFP-reporter assays |

| Cell Surface Display | High (107-1011 variants) | Direct phenotype-genotype linkage; compatible with FACS | May not mimic native cellular environment | Bond-forming enzyme evolution; antibody engineering |

| In Vitro Compartmentalization | Very High (109 variants) | Bypasses cellular transformation; controlled reaction conditions | Optimization required for different enzymes | [FeFe] hydrogenase engineering; β-galactosidase evolution |

Integration of Machine Learning with HTS

The Machine Learning Revolution in Biocatalysis

Machine learning (ML) has emerged as a transformative technology in enzyme engineering, promising to revolutionize protein engineering for biocatalytic applications and significantly accelerate development timelines previously needed to optimize enzymes [8] [9]. ML tools help scientists navigate the complexity of functional protein sequence space by predicting sequence-function relationships, enabling more intelligent exploration of vast combinatorial possibilities. These approaches are particularly valuable for addressing the challenge of epistatic interactions, where combinations of mutations show non-additive effects that are difficult to predict through sequential screening alone [9].

ML-Guided Cell-Free Expression Platforms

Recent breakthroughs have integrated ML with cell-free gene expression systems to create powerful platforms for enzyme engineering. One such platform combines cell-free DNA assembly, cell-free gene expression, and functional assays to rapidly map fitness landscapes across protein sequence space [9]. This approach enables the evaluation of substrate preference for thousands of enzyme variants across numerous unique reactions, generating the extensive datasets needed to train predictive ML models. In a notable application, this platform engineered amide synthetases by evaluating 1,217 enzyme variants in 10,953 unique reactions, using the data to build augmented ridge regression ML models that predicted variants capable of synthesizing nine small-molecule pharmaceuticals with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme [9].

Automated Robotic Platforms for Data Generation

To support data-intensive ML approaches, researchers have developed low-cost, robot-assisted pipelines for high-throughput protein purification and characterization. These systems address the critical need for cost-effective production of purified enzymes for accurate biophysical and activity assessments, which is essential for generating high-quality training data for ML models [10]. One such platform using the Opentrons OT-2 liquid-handling robot enables the parallel transformation, inoculation, and purification of 96 enzymes in a well-plate format, processing hundreds of enzymes weekly with minimal waste and reduced operational costs [10]. This accessibility democratizes automated protein production, facilitating the large-scale data generation required for robust ML model training.

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Machine Learning-Guided Enzyme Engineering Protocol

The following workflow outlines an integrated ML-guided approach for enzyme engineering, adapted from recent literature [9]:

4.1.1 Substrate Scope Evaluation

- Begin by comprehensively evaluating the substrate promiscuity of the wild-type enzyme against an extensive array of potential substrates, including primary, secondary, alkyl, aromatic, complex pharmacophores, and challenging substrates with multiple functional groups [9].

- Identify both accessible and inaccessible products to guide engineering priorities. For example, in amide bond-forming enzymes, note that aliphatic acids are often poorly tolerated while aryl, benzoic, and cinnamic acids are more readily accepted [9].

4.1.2 Hot Spot Screening (HSS)

- Select residues for mutagenesis based on structural information (e.g., within 10Å of active site or substrate tunnels).

- Perform site-saturation mutagenesis on selected positions (64 residues × 19 amino acids = 1,216 total single mutants) [9].

- Express variants using cell-free protein synthesis systems to avoid transformation and cloning steps.

- Screen variants under industrially relevant conditions (e.g., high substrate concentration, low enzyme loading).

4.1.3 Machine Learning Model Training

- Use sequence-function data from HSS to train supervised ridge regression ML models augmented with evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictors [9].

- Ensure models can run on standard computer CPUs for accessibility.

- Focus models on predicting higher-order mutants with increased activity for specific chemical transformations.

4.1.4 Experimental Validation and Iteration

- Test ML-predicted enzyme variants for activity enhancement relative to parent enzyme.

- Incorporate validation results into subsequent training cycles for continuous model improvement.

- Apply divergent evolution strategies to convert generalist enzymes into multiple distinct specialists for different reactions [9].

Robot-Assisted High-Throughput Protein Purification Protocol

For laboratories implementing high-throughput enzyme screening, the following protocol enables parallel processing of 96 enzyme variants [10]:

4.2.1 Gene Synthesis and Cloning

- Employ plasmid constructs containing affinity tags and protease cleavage sites (e.g., pCDB179 with His-tag for Ni-affinity purification and SUMO site for proteolytic cleavage) [10].

- Perform codon optimization and commercial gene synthesis for target proteins.

- Use protease cleavage as the primary elution method to avoid high concentrations of imidazole or other elution agents that might interfere with downstream analyses.

4.2.2 Transformation and Expression

- Use chemically competent E. coli cells (e.g., Zymo Mix & Go!) transformed without heat shock [10].

- Grow transformation mix directly as starter cultures, bypassing plating and colony picking to save time and cost.

- Employ autoinduction media in 24-deep-well plates with 2mL cultures for improved aeration and higher yields.

- Incubate for approximately 40 hours at 30°C for optimal culture saturation.

4.2.3 Purification and Analysis

- Use liquid-handling robots (e.g., Opentrons OT-2) for magnetic bead-based purification.

- Implement Ni-charged magnetic beads for affinity capture.

- Perform on-bead protease cleavage using SUMO protease to release target protein without affinity tag remnants.

- Assess protein purity, yield (up to 400μg per purification), and activity for comprehensive characterization.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS in Enzyme Engineering

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Implementation Example | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid-Handling Robots | Automation of repetitive pipetting steps | Opentrons OT-2 for 96-well parallel processing | Low-cost (~$20,000-30,000 USD); open-source Python protocols [10] |

| Specialized Vectors | High-yield expression and purification | pCDB179 with His-SUMO tag | Enables tag-free purification via protease cleavage [10] |

| Cell-Free Expression Systems | Rapid protein synthesis without transformation | CFE for site-saturated libraries | Bypasses cellular transformation; 1-day variant production [9] |

| Magnetic Bead Purification | High-throughput affinity purification | Ni-charged beads for His-tagged proteins | Compatible with plate-based formats; enables parallel processing [10] |

| Fluorescent Reporters | Activity detection and sorting | GFP, CFP, YFP for FRET-based assays | Enables FACS screening when coupled with enzymatic activity [2] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation in qHTS

The Hill Equation in Quantitative HTS

The Hill equation (HEQN) remains the most widely used model for analyzing qHTS concentration-response data, offering a well-established framework for describing sigmoidal response curves with biologically interpretable parameters [7]. The logistic form of the HEQN is represented as:

[ Ri = E0 + \frac{(E{\infty} - E0)}{1 + \exp{-h[\log Ci - \log AC{50}]}} ]

Where (Ri) is the measured response at concentration (Ci), (E0) is the baseline response, (E{\infty}) is the maximal response, (AC{50}) is the concentration for half-maximal response, and (h) is the shape parameter [7]. The (AC{50}) and (E{max}) ((E{\infty} - E0)) parameters are frequently used to prioritize chemicals for further development, with (AC{50}) representing compound potency and (E_{max}) representing efficacy.

Challenges in Parameter Estimation

Despite its widespread use, HEQN parameter estimation presents significant statistical challenges in qHTS applications. Parameter estimates can be highly variable when the tested concentration range fails to include at least one of the two HEQN asymptotes, when responses are heteroscedastic, or when concentration spacing is suboptimal [7]. Simulation studies demonstrate that AC50 estimates show poor repeatability (spanning several orders of magnitude) when the lower asymptote is not established, particularly for curves with lower Emax values [7]. These limitations can lead to both false negatives (potent compounds with "flat" profiles declared inactive) and false positives (null compounds spuriously declared active due to random response variation).

Optimization Strategies for Reliable Results

To enhance the reliability of qHTS data analysis, several strategies have been developed:

- Increased Sample Size: Larger sample sizes through experimental replicates noticeably increase the precision of AC50 and Emax estimates [7].

- Optimal Study Designs: Development of optimized concentration ranges and spacing to improve nonlinear parameter estimation.

- Alternative Approaches: Utilization of methods with reliable performance characteristics across diverse response profiles, particularly for non-sigmoidal or non-monotonic relationships that cannot be adequately described by the HEQN [7].

High-Throughput Screening has evolved from a simple tool for testing compounds to a sophisticated, integrated platform that combines robotics, miniaturization, and computational intelligence. The convergence of HTS with machine learning represents a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering and drug discovery, enabling researchers to navigate vast sequence spaces with unprecedented efficiency. As these technologies become more accessible through low-cost automation and user-friendly ML implementations, their impact across biotechnology and pharmaceutical development will continue to expand. Future advancements will likely focus on increasing integration between experimental and computational approaches, enhancing predictive capabilities, and further reducing the time and cost required to engineer novel biocatalysts and discover therapeutic compounds.

In the field of enzyme engineering, the ability to predict the functional consequences of amino acid substitutions is paramount for accelerating the design of improved biocatalysts. While machine learning (ML) models have become powerful tools for computationally pre-screening enzyme variants, their performance in prospective applications remains inconsistent. A key challenge is that prediction accuracy can vary dramatically from one variant to another [11] [12]. Understanding the structural factors that contribute to this variability is crucial for developing more robust models and efficient engineering strategies. Recent research has systematically investigated how specific structural characteristics—including buriedness, proximity to the active site, number of contact residues, and presence of secondary structure elements—influence the predictability of variant effects [11]. This Application Note delineates the quantitative impact of these structural determinants and provides detailed protocols for integrating this knowledge into high-throughput screening workflows for enzyme engineering, framed within a broader thesis on optimizing variant effect prediction.

Quantitative Impact of Structural Determinants on Predictability

Recent research analyzing a combinatorial dataset of 3,706 enzyme variants revealed that all four tested structural characteristics significantly influence the accuracy of variant effect prediction (VEP) models. The study, which trained four different supervised ML models on structurally partitioned data, found that predictability strongly depended on buriedness, number of contact residues, proximity to the active site, and presence of secondary structure elements [11]. These dependencies were consistent across all tested models, indicating fundamental limitations in current algorithms' capacity to capture these structure-function relationships [11] [12].

Table 1: Structural Determinants of Variant Effect Predictability

| Structural Characteristic | Impact on Predictability | Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Buriedness | Significant impact on model accuracy; residues with low solvent accessibility show different predictability patterns [11] [13]. | Analysis of 12 deep mutational scanning datasets; side chain accessibility ≤5% defined as buried [13]. |

| Active Site Proximity | Strong correlation with prediction error; mutations near catalytic sites less predictable [11]. | Partitions of variants based on distance to active site in novel 3,706-variant dataset [11] [12]. |

| Contact Residues | Number of residue-residue contacts influences model performance [11]. | Structural partitioning by contact number in high-order combinatorial dataset [11]. |

| Secondary Structure | Presence of specific secondary structure elements affects predictability [11]. | Training of VEP models on subsets grouped by secondary structure class [11]. |

The consistency of these findings across multiple enzyme datasets suggests they represent fundamental challenges in computational protein engineering rather than algorithm-specific limitations. This underscores the necessity of incorporating structural insights into both model development and experimental design.

Protocols for Structural Determinant Analysis in Enzyme Variants

Protocol 1: Classifying Buried and Active-Site Residues from Deep Mutational Scanning Data

Purpose: To identify buried and active-site residues using deep mutational scanning data, particularly when high-resolution structural information is limited.

Background: Deep mutational scanning reveals the impact of mutations on protein function through saturation mutagenesis and phenotypic screening [13]. distinguishing between buried residues and exposed active-site residues solely from mutational sensitivity patterns remains challenging without structural data.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Tools for Residue Classification

| Reagent/Tool | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning Dataset | Provides functional scores for single-site mutations (e.g., 12 curated datasets [13]). |

| PROF or NetSurfP | Neural network-based prediction of sequence-based surface accessibility [13]. |

| NACCESS Program | Calculation of structure-based solvent accessibility from PDB files (% accessibility) [13]. |

| DEPTH Server | Computation of residue depth from protein structures [13]. |

| Rescaled Mutational Sensitivity Scores | Normalized scores (0 to -1) where -1 indicates high sensitivity and 0 indicates wild-type-like function [13]. |

Procedure:

Data Curation and Rescaling:

- Curate mutational effect scores from deep mutational scanning experiments. Ensure sufficient coverage of single-site mutations across the protein region of interest.

- Rescale the raw scores to a normalized range of 0 to -1 using the formula:

M_rescaled = (b - a) * [M - min(M)] / [max(M) - min(M)] + awhereMis the mutational effect score, andaandbare -1 and 0, respectively. This sets the most sensitive positions to approximately -1 and wild-type-like mutations to approximately 0 [13].

Accessibility Prediction:

- Calculate structure-based accessibility from available PDB structures using the NACCESS program. Define a residue as buried if its side chain accessibility is ≤5% and exposed if >5% [13].

- For proteins without resolved structures, predict sequence-based surface accessibility using computational tools like PROF or NetSurfP [13].

Residue Classification:

- Average the rescaled mutational sensitivity scores across all mutations for each position. Include only positions with mutational data for a minimum of 10 mutants.

- Classify residues using the following criteria [13]:

- Active-site residues: High mutational sensitivity (average score ≈ -1) AND predicted to be exposed.

- Buried residues: High mutational sensitivity AND predicted to be buried.

- Exposed non-active-site residues: Low mutational sensitivity (average score ≈ 0) AND predicted to be exposed.

Validation:

- Compare predictions with known catalytic sites identified through sequence conservation or structural homology.

- For proteins with available structures, validate classifications against experimental data from site-directed mutagenesis.

Protocol 2: Machine Learning-Guided Engineering with Structural Filtering

Purpose: To engineer enzyme variants with enhanced activity by integrating stability predictions and structural information into library design, thereby reducing screening burden and focusing on productive mutational paths.

Background: Traditional directed evolution screens large libraries where most mutations are neutral or deleterious. Filtering out destabilizing mutations based on structural and energy calculations enables more efficient exploration of sequence space [14] [9].

Procedure:

Target Identification:

- Based on substrate scope evaluation, select target reactions for engineering. For example, in engineering the amide synthetase McbA, target pharmaceutical compounds like moclobemide, metoclopramide, and cinchocaine [9].

- Identify residues for mutagenesis using structural analysis. Focus on residues within a defined radius (e.g., 6 Å) of the bound ligand or substrate and those lining access tunnels to the active site [14] [9].

Computational Filtering:

- Use protein modeling software (e.g., Rosetta) to calculate the change in free energy (ΔΔG) upon mutation for all possible single amino acid substitutions at targeted positions.

- Apply a stability threshold (e.g., ΔΔG ≤ -0.5 Rosetta Energy Units) to filter out mutations predicted to significantly destabilize the protein fold. This can exclude approximately 50% of possible mutations that are unlikely to be beneficial [14].

Library Construction and Screening:

- Construct the filtered library using high-throughput gene synthesis methods, such as overlap extension PCR with customized oligonucleotide pools [14] or cell-free DNA assembly [9].

- Express and screen variants using appropriate high-throughput assays. For transketolase engineering, this could involve pH-sensitive assays with colorimetric readouts or direct product detection via hydroxamate formation [15]. For amide synthetases, screen for product formation under industrially relevant conditions [9].

Machine Learning Integration:

- Use the collected sequence-function data to train supervised ML models (e.g., augmented ridge regression).

- Apply the trained models to predict higher-order combinatorial mutants with improved activity [9].

- Iterate the process through multiple rounds of design-build-test-learn (DBTL) cycles to continuously refine enzyme function.

The following diagram illustrates the integrated ML-guided engineering workflow that incorporates structural filtering:

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Category | Item | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Assays | pH-sensitive assay (Phenol red/HPTS) | Indirect, high-throughput readout of catalytic activity via CO₂ release [15]. |

| Hydroxamate assay (Iron(III) chelation) | Direct, colorimetric product detection; suitable for liquid or solid-phase screening [15]. | |

| Computational Tools | Rosetta Protein Modeling Suite | Calculates ΔΔG for mutations to filter destabilizing variants from libraries [14]. |

| PROF/NetSurfP | Predicts sequence-based solvent accessibility for residue classification [13]. | |

| NACCESS/DEPTH server | Computes structure-based solvent accessibility and residue depth from PDB files [13]. | |

| Library Construction | Cell-free gene expression (CFE) | Enables rapid synthesis and testing of protein variants without cellular cloning [9]. |

| Overlap extension PCR | Assembles complex gene libraries from customized oligo pools for full-gene synthesis [14]. |

The structural determinants of buriedness, active site proximity, contact residues, and secondary structure elements are consistently significant factors influencing the predictability of enzyme variant effects. Acknowledging and systematically accounting for these determinants, as detailed in the provided protocols, enables more effective enzyme engineering. Strategies that integrate structural filtering to remove destabilizing mutations and employ ML-guided DBTL cycles can dramatically accelerate the evolution of enzymes, as demonstrated by the development of highly efficient Kemp eliminases in only five rounds [14] and specialized amide synthetases with up to 42-fold improved activity [9]. Future improvements in VEP models will likely stem from incorporating these structural characteristics as inductive biases and leveraging multi-modal protein data, ultimately leading to more predictive computational tools and efficient biocatalyst design.

The field of enzyme engineering is undergoing a revolutionary transformation, moving from traditional labor-intensive screening methods toward integrated systems that combine automation, high-throughput experimentation, and artificial intelligence. Traditional approaches to enzyme variant screening, such as directed evolution, have long been hampered by their reliance on extensive manual experimentation, limited throughput, and the challenge of navigating vast sequence spaces [16]. These methods typically required testing hundreds of variants over months or even years, creating a significant bottleneck in protein engineering pipelines [17] [16]. The emergence of high-throughput screening technologies and machine learning (ML) has fundamentally altered this landscape, enabling researchers to evaluate thousands of variants with unprecedented speed and precision. This paradigm shift is particularly evident in pharmaceutical development and green chemistry, where efficient enzyme engineering can significantly accelerate drug discovery and sustainable manufacturing processes [17] [18]. This Application Note details the key technologies driving this evolution and provides practical protocols for their implementation in modern enzyme variant analysis.

Quantitative Comparison of Screening Methodologies

The evolution from traditional to modern screening approaches has yielded dramatic improvements in key performance metrics. The following table summarizes these advancements across critical parameters.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Enzyme Variant Screening Methodologies

| Screening Methodology | Throughput (Variants/Time) | Detection Sensitivity | Resource Consumption | Automation Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Plate-Based Assays | Hundreds per day | Moderate | High reagent costs, significant plastic waste | Low, primarily manual steps |

| Microfermentation Systems [19] | Thousands per day | High | Reduced reagent volumes (mL scale) | High, integrated robotics |

| DiBT-MS Technology [17] [20] | ~1000x traditional methods | High | Minimal solvent use, reusable slides | Medium, automated sample handling |

| AI-Powered Autonomous Platforms [21] | Hundreds to thousands per cycle | High | Optimized via ML-guided design | Full end-to-end automation |

The implementation of these advanced systems requires corresponding evolution in experimental design and data analysis approaches, as outlined in the following comparison.

Table 2: Experimental Design Requirements Across Screening Platforms

| Experimental Parameter | Traditional Methods | Integrated AI-Biofoundry Platforms |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Library Design | Random mutagenesis, limited diversity | Protein LLMs (e.g., ESM-2), epistasis models [21] |

| Fitness Evaluation | Single-parameter, endpoint measurements | Multi-parametric, real-time monitoring |

| Data Utilization | Linear analysis, limited learning | Iterative DBTL cycles with ML model refinement [21] [16] |

| Human Intervention | Extensive manual operation | Minimal intervention after initial setup |

Advanced Screening Technologies in Practice

High-Throughput Microfermentation Systems

Modern microfermentation platforms represent a significant advancement over traditional fermentation methods. Systems such as those developed by Beckman Coulter Life Sciences utilize miniaturized bioreactors (volume: few mL) operating in parallel, enabling simultaneous execution of hundreds to thousands of experiments [19]. Key technological features include:

- Integrated sensor arrays for real-time monitoring of critical parameters (temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen)

- Automated liquid handling and robotic sampling capabilities

- Data analytics platforms with visualization tools for rapid condition optimization

These systems dramatically reduce reagent consumption and labor requirements while providing rich datasets for evaluating enzyme expression and function under varied physiological conditions [19].

BioTransformation Direct Analysis Mass Spectrometry (DiBT-MS)

The recently developed DiBT-MS technology addresses fundamental limitations in traditional enzyme activity screening. By innovating upon existing Desorption Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (DESI-MS), this approach enables direct analysis of enzyme activity without sample pretreatment [17] [20]. Key advantages include:

- Radical time compression: Assays completed in ~2 hours versus several days with conventional methods

- Dramatically reduced consumable usage through optimized slide reuse technology

- Direct observation of enzyme reaction kinetics in real-time

This technology has demonstrated particular value in pharmaceutical development, where it accelerates screening of enzyme variants for drug synthesis pathways while aligning with green chemistry principles through reduced solvent waste and plastic consumption [17].

Integrated AI-Driven Enzyme Engineering Platforms

The Autonomous Engineering Workflow

Cutting-edge enzyme engineering now combines biofoundry automation with artificial intelligence in self-directed systems. The general workflow implemented on platforms like the Illinois Biological Foundry (iBioFAB) integrates several advanced technologies [21]:

- Protein Large Language Models (e.g., ESM-2): Predict variant fitness from sequence context

- Epistasis modeling: Identify residue-residue interactions affecting function

- High-fidelity DNA assembly: Enable construction of variant libraries without intermediate sequencing

- Machine learning-guided optimization: Bayesian optimization and other ML algorithms predict promising variants for subsequent cycles

This integrated approach was successfully demonstrated in engineering Arabidopsis thaliana halide methyltransferase (AtHMT), achieving a 16-fold improvement in ethyltransferase activity, and Yersinia mollaretii phytase (YmPhytase), yielding a 26-fold enhancement in neutral pH activity, both within four weeks [21].

Machine Learning for Functional Characterization

Beyond engineering, ML models are revolutionizing enzyme characterization. The AlphaCD platform exemplifies this approach, using sequence and structural features to predict multiple functional parameters for cytidine deaminases with high accuracy [22]:

- Catalytic efficiency (predictive accuracy: 0.92)

- Off-target activity (predictive accuracy: 0.84)

- Target site window (predictive accuracy: 0.73)

- Catalytic motif preferences (predictive accuracy: 0.78)

Such models enable researchers to virtually screen thousands of enzyme variants, prioritizing the most promising candidates for experimental validation [22].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: DiBT-MS for Enzyme Activity Screening

Purpose: Direct measurement of enzyme activity for variant screening without sample pretreatment.

Materials:

- DiBT-MS instrument with DESI ionization source

- Glass slides with hydrophobic patterning

- Enzyme variants in expression lysate

- Substrate solutions dissolved in appropriate buffers

- Calibration standards for quantification

Procedure:

- Sample Spotting: Array 0.5-1 μL of each enzyme variant lysate onto predefined positions on the reusable glass slide.

- Substrate Application: Apply 0.2-0.5 μL substrate solution directly onto each enzyme spot, initiating reaction.

- Incubation: Allow reaction to proceed for 5-30 minutes under controlled humidity (room temperature).

- Direct Analysis: Perform DESI-MS analysis using optimized solvent flow rates (1-5 μL/min) and gas pressures.

- Data Acquisition: Monitor reaction products in real-time using selected ion monitoring (SIM) or full scan modes.

- Quantification: Compare peak areas of products to calibration curves for enzyme activity calculation.

Notes: Slide reuse is possible after cleaning with solvent wash and verification of no carryover. This protocol reduces traditional multi-day processes to approximately 2 hours [17] [20].

Protocol: Autonomous DBTL Cycle for Enzyme Engineering

Purpose: Iterative enzyme optimization through integrated design, construction, testing, and learning cycles.

Materials:

- Biofoundry platform with liquid handling, thermal cyclers, and microfermentation capabilities

- Protein LLM access (e.g., ESM-2) and ML model implementation

- High-fidelity DNA assembly reagents

- Robotic colony picking system

- Automated assay platforms (e.g., plate readers, MS systems)

Procedure:

- Design Phase:

- Input wild-type protein sequence into ESM-2 and epistasis models [21]

- Generate initial library of 150-200 variants focusing on diverse mutations

- Select top candidates based on predicted fitness scores

Build Phase:

- Execute automated PCR-based mutagenesis using high-fidelity assembly [21]

- Perform robotic transformation into expression host

- Pick multiple colonies per variant using automated colony picking

Test Phase:

- Inoculate deep-well plates for expression using liquid handling

- Induce protein expression under standardized conditions

- Perform automated functional assays (e.g., catalytic activity, stability)

- Collect high-quality dataset for ML training

Learn Phase:

- Train ML models (e.g., Bayesian optimization) on variant sequence-activity data

- Identify sequence-function relationships and mutation interactions

- Design next variant library based on model predictions

- Initiate subsequent DBTL cycle with refined library

Notes: Each complete cycle typically requires 1-2 weeks, with progressive improvement in enzyme properties over 3-5 cycles [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms

Implementation of advanced enzyme screening requires specific reagents, instruments, and computational tools. The following table details key components of a modern enzyme engineering pipeline.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Modern Enzyme Variant Analysis

| Category | Specific Tool/Platform | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biofoundry Automation | iBioFAB Platform [21] | End-to-end automation of enzyme engineering | Modular workflow execution, robotic integration |

| Screening Instruments | DiBT-MS System [17] | High-throughput enzyme activity screening | Direct analysis, minimal sample preparation |

| Microfermentation System [19] | Parallel cultivation and screening | Miniaturized bioreactors, real-time monitoring | |

| Computational Tools | ESM-2 (Protein LLM) [21] | Variant fitness prediction | Transformer architecture trained on global protein sequences |

| Epistasis Models [21] | Identification of residue interactions | EVmutation-based analysis of homologous sequences | |

| Molecular Biology | High-Fidelity DNA Assembly [21] | Error-reduced variant construction | ~95% accuracy without intermediate sequencing |

| Machine Learning | Bayesian Optimization Models [21] | Guided library design | Predicts promising variants from limited data |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Enzyme screening evolution from traditional to AI-powered methods

Diagram 2: Autonomous enzyme engineering workflow using AI and biofoundries

Key Challenges in Conventional Enzyme Engineering Approaches and HTS Solutions

Enzyme engineering is a cornerstone of modern biocatalysis, with applications spanning pharmaceutical synthesis, biofuel production, and green chemistry. However, conventional approaches to enzyme engineering face significant limitations that hinder the rapid development of optimized biocatalysts. These challenges primarily stem from methodological constraints in creating and analyzing enzyme variant libraries. Traditional methods often rely on small functional datasets and low-throughput screening strategies, leading to incomplete exploration of sequence-function relationships and potentially missing optimal enzyme variants [23]. Furthermore, selection methods frequently focus on evolving "winning" enzymes for a single specific transformation, which limits the collection of comprehensive sequence-function data that could inform future engineering efforts for similar reactions [23]. These constraints become particularly problematic when engineering enzymes for complex industrial applications where multiple properties such as activity, stability, and substrate specificity must be optimized simultaneously.

The emergence of high-throughput screening (HTS) technologies represents a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering, enabling researchers to overcome these traditional limitations. By allowing for the rapid assessment of thousands of enzyme variants under diverse conditions, HTS platforms provide the comprehensive datasets necessary for informed enzyme optimization [23] [15] [24]. This application note examines the key challenges in conventional enzyme engineering and details the HTS solutions that are transforming the field, with particular emphasis on practical protocols and implementation strategies for researchers and drug development professionals.

Key Challenges in Conventional Enzyme Engineering

Limited Exploration of Sequence-Function Relationships

Conventional enzyme engineering approaches typically generate limited functional datasets that fail to capture the complex interactions between different amino acid residues within a protein structure. This incomplete mapping of sequence-function relationships significantly reduces the probability of identifying optimal enzyme variants. The multidimensional nature of protein fitness landscapes means that beneficial mutations often interact in non-additive ways (epistasis), creating rugged landscapes where optimal combinations of mutations can be easily overlooked with sparse sampling [25]. This challenge is compounded when engineering enzymes for multiple substrates or reaction conditions simultaneously, as the sequence requirements for each function may differ substantially.

Machine learning (ML) approaches have demonstrated that the predictive power of models for enzyme engineering is directly correlated with the size and quality of the training data [23]. Conventional methods that produce small datasets therefore not only limit immediate discovery but also hamper the development of computational tools that could accelerate future engineering campaigns. The Northwestern Engineering team highlighted this fundamental limitation, noting that small datasets lead to "missed interactions among different amino acid residues within a protein" [23].

Throughput Limitations in Screening and Selection

The low-throughput nature of conventional screening methods creates a significant bottleneck in the enzyme engineering pipeline. Typical screening strategies can only assess a limited number of variants due to technical constraints, resource requirements, and time limitations [23]. This restricted throughput is particularly problematic when employing random mutagenesis approaches, where the probability of beneficial mutations is low and large libraries must be screened to identify improvements [26].

Traditional methods often focus on evolving enzymes for a single transformation, which further limits the utility of the collected data for broader engineering applications [23]. This single-function focus fails to capture the complex relationships between enzyme sequence and multiple functional parameters, including activity under different conditions, substrate specificity, and stability. The throughput challenge extends beyond initial screening to include the upstream processes of variant generation and the downstream processes of validation and characterization, creating a system-wide bottleneck in conventional enzyme engineering workflows.

Technical and Resource Constraints

Conventional enzyme engineering faces significant technical hurdles related to assay sensitivity, detection limitations, and resource intensiveness. These constraints are particularly pronounced when engineering enzymes that produce challenging molecules such as hydrocarbons, which can be "insoluble, gaseous, and chemically inert," making their detection and quantification difficult [26]. Similarly, engineering enzymes for reactions without direct spectroscopic handles requires complex assay development with multiple coupling steps, increasing the potential for interference and false results.

The resource requirements of conventional methods also limit their accessibility and scalability. Large-scale expression and purification of enzyme variants using traditional liter-scale approaches followed by chromatographic purification is time-consuming, expensive, and impractical for processing thousands of variants [10]. This creates a significant barrier for research groups and organizations without access to substantial funding or specialized equipment, slowing the overall pace of innovation in enzyme engineering.

Table 1: Key Challenges in Conventional Enzyme Engineering and Their Implications

| Challenge | Specific Limitations | Impact on Enzyme Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Limited Sequence-Function Data | Small datasets, missed residue interactions, single transformation focus | Incomplete fitness landscape mapping, suboptimal variant selection |

| Throughput Restrictions | Low-throughput screening, limited variant assessment, resource-intensive validation | Reduced probability of identifying beneficial mutations, extended development timelines |

| Technical Constraints | Insensitive detection methods, challenging molecule detection, complex assay requirements | Difficulty engineering enzymes for specific reactions, increased false positive/negative rates |

| Resource Limitations | High costs, specialized equipment requirements, extensive personnel time | Reduced accessibility, limited scalability, slower innovation pace |

High-Throughput Screening Solutions

Advanced HTS Assay Development

The development of robust, sensitive, and reproducible HTS assays is fundamental to overcoming the limitations of conventional enzyme engineering. Modern HTS approaches employ diverse detection strategies tailored to specific reaction types and engineering goals. Two particularly innovative approaches recently documented include pH-based screening and colorimetric product detection assays.

For engineering transketolases toward non-natural substrate acceptance, researchers have developed a pH-sensitive screening method that monitors CO₂ release from keto acid donor substrates. This approach uses inexpensive pH indicators (phenol red for absorption measurements or HPTS for fluorescence) to detect changes in reaction media as an indirect readout of substrate consumption [15]. Although this method provides only an indirect signal of catalytic conversion and can be sensitive to experimental variability, its simplicity and broad applicability make it valuable for initial library screening. Complementing this approach, a hydroxamate assay enables direct colorimetric monitoring of product formation through iron(III) chelation. The resulting dark-red complex indicates successful synthesis of N-aryl hydroxamic acid products, offering improved specificity and reduced background interference compared to indirect methods [15].

For isomerase engineering, researchers have adapted classical chemical reactions into HTS formats. A recently established protocol for screening L-rhamnose isomerase variants employs Seliwanoff's reaction to detect ketoses through dehydration in hydrochloric acid followed by reaction with resorcinol to produce colored compounds [24]. This approach enables rapid, indirect measurement of isomerase activity by monitoring changes in ketose concentration during the reaction. The statistical metrics reported for this assay (Z'-factor of 0.449, signal window of 5.288, and assay variability ratio of 0.551) meet acceptance criteria for high-quality HTS assays, demonstrating the robustness achievable with properly optimized protocols [24].

Automated and Miniaturized Platforms

Automation and miniaturization represent critical advancements in HTS for enzyme engineering, dramatically increasing throughput while reducing costs and resource requirements. Recent developments have demonstrated the feasibility of establishing low-cost, robot-assisted pipelines for high-throughput enzyme discovery and engineering. These systems leverage liquid-handling robots to parallelize the most labor-intensive steps of enzyme production and characterization, enabling a single researcher to process hundreds of enzymes weekly [10].

A key innovation in this space is the development of miniaturized protein expression and purification protocols adapted to well-plate formats. Researchers have successfully translated conventional liter-scale expression and chromatography to 24-deep-well plates with 2 mL cultures, achieving protein yields up to 400 µg with sufficient purity for comprehensive functional and stability analyses [10]. This miniaturization reduces material costs and experimental waste while maintaining the quality required for meaningful biochemical characterization. The integration of automated transformation, inoculation, and purification steps creates a seamless pipeline that minimizes human error and variability while maximizing throughput.

For in vivo enzyme engineering, automated continuous evolution platforms represent another transformative approach. These systems integrate in vivo hypermutators with growth-coupled selection to enable continuous enzyme optimization without manual intervention [25]. By coupling desired enzymatic activities to microbial fitness, these platforms allow beneficial variants to automatically enrich in the population, creating a powerful Darwinian selection system for enzyme improvement.

Table 2: Comparison of HTS Platforms for Enzyme Engineering

| Platform Type | Throughput | Key Features | Applications | Implementation Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robot-assisted purification | 96+ proteins in parallel | Low-cost liquid handling, miniaturized expression, automated purification | Recombinant enzyme production, variant characterization | Requires initial equipment investment, adaptable protocols |

| Cell-free screening | 10,000+ reactions | Customizable reaction environment, direct assay compatibility, no cell barriers | Rapid mapping of sequence-function relationships, condition screening | Limited protein yields, may not reflect cellular environment |

| In vivo continuous evolution | Continuous | Growth-coupled selection, automated hypermutation, minimal intervention | Enzyme optimization when activity can be linked to fitness | Requires careful selection strain design, may exhibit background growth |

| Microfluidic droplet systems | >10^6 variants/day | Ultra-high throughput, compartmentalization, single-cell analysis | Massive library screening, directed evolution campaigns | Specialized equipment, complex setup, assay compatibility challenges |

Machine Learning-Guided HTS

The integration of machine learning with HTS represents a paradigm shift in enzyme engineering, creating powerful closed-loop systems that accelerate the design-build-test-learn cycle. ML-guided approaches use experimental data to predict beneficial mutations and optimize library design, reducing the experimental burden required to identify improved enzyme variants [23] [25]. This synergistic combination allows researchers to navigate complex fitness landscapes more efficiently by focusing screening efforts on regions with higher probabilities of success.

A notable implementation of this approach demonstrated the engineering of amide synthetase enzymes using ML-guided cell-free expression. This platform enabled the assessment of 1,217 enzyme mutants in 10,953 unique reactions, generating comprehensive data to train ML models that successfully predicted synthetase variants capable of producing nine small molecule pharmaceuticals [23]. The resulting models could explore sequence-fitness landscapes across multiple regions of chemical space simultaneously, enabling parallel engineering of specialized biocatalysts [23].

ML approaches also support HTS by enabling the design of auxotroph selection strains and predicting which gene deletions will create effective growth-coupled selection systems [25]. This application is particularly valuable for in vivo directed evolution, where coupling enzyme activity to cellular fitness provides a powerful selection mechanism that can replace or complement traditional screening approaches.

Detailed HTS Protocols

Protocol: High-Throughput Screening of Isomerase Variants Using Seliwanoff's Reaction

This protocol provides a detailed methodology for establishing a robust HTS system for isomerase engineering, specifically applied to L-rhamnose isomerase variants but adaptable to other isomerases with appropriate modifications [24].

Materials and Reagents

- Plasmid DNA encoding isomerase variants in appropriate expression vector

- Competent E. coli cells (BL21(DE3) or similar expression strains)

- LB medium with appropriate antibiotics

- Bugbuster Master Mix or similar lysis reagent

- Substrate master mix: 100 mM D-allulose, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0), 10 mM MnCl₂

- Seliwanoff's reagent: 0.1% resorcinol in 6N hydrochloric acid

- 96-well PCR plates and deep-well plates

- Plate reader capable of absorbance measurements (520-550 nm)

- Liquid handling robot (optional but recommended)

Procedure

Library Transformation and Expression

- Transform plasmid library into competent E. coli cells using high-efficiency transformation protocol

- Plate transformed cells on selective LB agar and incubate overnight at 37°C

- For high-throughput expression, inoculate single colonies into 1 mL LB medium with antibiotic in 96-deep-well plates

- Induce protein expression with 5 mM lactose and incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 18 hours

Cell Lysis and Enzyme Preparation

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at 2,000 × g for 10 minutes

- Discard supernatant and resuspend cell pellets in 200 μL Bugbuster Master Mix

- Incubate at 25°C with shaking (300 rpm) for 20 minutes for complete lysis

- Centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 20 minutes to collect supernatant containing soluble enzyme

Enzyme Reaction

- Transfer 40 μL of lysate supernatant to 96-well PCR plate

- Add 160 μL of substrate master mix to initiate reactions

- Incubate in thermal cycler at 75°C for 4 hours

- Terminate reactions by heating to 95°C for 5 minutes followed by cooling to 4°C

Seliwanoff's Detection

- Centrifuge terminated reactions at 13,000 × g for 3 minutes to pellet denatured protein

- Transfer 240 μL of supernatant to new plate containing 480 μL Seliwanoff's reagent

- Incubate at 60°C for 30 minutes in water bath

- Cool at room temperature for 1 hour to stabilize color development

- Measure absorbance at 540 nm in plate reader

Data Analysis

- Calculate residual ketose concentration from standard curve

- Determine enzyme activity based on substrate depletion

- Normalize activities to positive and negative controls

- Select top-performing variants for validation and sequencing

Quality Control and Validation

- Include positive control (wild-type enzyme) and negative control (empty vector) in each plate

- Validate assay performance using statistical metrics (Z'-factor > 0.4, signal window > 2)

- Confirm hits using alternative analytical methods (e.g., HPLC) when possible

- Perform sequence analysis to identify beneficial mutations

Protocol: Robot-Assisted Protein Purification for Enzyme Characterization

This protocol describes a automated, miniaturized protein purification workflow for high-throughput enzyme production, enabling functional characterization of hundreds of variants [10].

Materials and Reagents

- Plasmid constructs with affinity tags (e.g., His-tag, SUMO tag)

- Competent E. coli cells with appropriate genetic background

- Zymo Mix & Go! E. coli Transformation Kit or similar

- Autoinduction media with antibiotics

- Lysis buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole

- Ni-charged magnetic beads for affinity purification

- Wash buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 25 mM imidazole

- Elution buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole OR protease for tag cleavage

- 24-deep-well plates with gas-permeable seals

- Liquid handling robot (Opentrons OT-2 or similar)

- Magnetic bead separation module

Procedure

High-Throughput Transformation

- Aliquot 50 μL competent cells per well in 96-well PCR plate kept on cooling block

- Add 1 μL plasmid DNA (50-100 ng) to each well using liquid handler

- Incubate on ice for 30 minutes

- Add 150 μL SOC media and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour

- Transfer transformation mix to 24-deep-well plates containing 2 mL autoinduction media with antibiotic

- Incubate at 30°C with shaking (200 rpm) for 40 hours

Cell Harvest and Lysis

- Harvest cells by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 20 minutes

- Discard supernatant and resuspend pellets in 400 μL lysis buffer

- Lyse cells by repeated pipetting or enzymatic lysis

- Centrifuge at 4,000 × g for 30 minutes to remove cell debris

- Transfer supernatant to new plate for purification

Automated Affinity Purification

- Aliquot 50 μL Ni-charged magnetic beads to each well

- Add clarified lysate and incubate with mixing for 45 minutes

- Capture beads using magnetic separation and discard supernatant

- Wash beads twice with 500 μL wash buffer

- For elution, either:

- Add 100 μL elution buffer and incubate 15 minutes, OR

- Add protease for tag cleavage and incubate according to enzyme specifications

- Collect eluate containing purified protein

Quality Assessment and Normalization

- Determine protein concentration using Bradford or similar assay

- Analyze purity by SDS-PAGE with representative samples

- Normalize protein concentrations for downstream assays

- Aliquot and store at -80°C if not used immediately

Implementation Notes

- This protocol enables processing of 96 enzymes in parallel with minimal manual intervention

- Typical yields range from 50-400 μg purified protein per sample

- Purity is sufficient for most enzymatic and biophysical assays

- The platform is highly scalable and can process hundreds of variants weekly

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for HTS in Enzyme Engineering

| Category | Specific Reagents/Materials | Function and Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Construction | Error-prone PCR kits, DNA shuffling reagents, Restriction enzymes (EcoRI, DpnI), Taq DNA polymerase | Generation of diverse mutant libraries for directed evolution | Mutation rate control, library diversity, representation bias |

| Expression Systems | Competent E. coli cells (BL21(DE3), DH5α), Expression vectors with affinity tags, Autoinduction media, Antibiotics | Recombinant production of enzyme variants | Expression level, solubility, folding efficiency |

| Cell Lysis & Purification | Bugbuster Master Mix, Ni-charged magnetic beads, Lysis buffers, Imidazole solutions, Proteases for tag cleavage | Extraction and purification of enzyme variants from expression hosts | Yield, purity, activity retention, compatibility with downstream assays |

| HTS Assay Reagents | pH indicators (phenol red, HPTS), Chromogenic substrates, Seliwanoff's reagent (resorcinol + HCl), Iron(III) chloride | Detection of enzymatic activity in high-throughput format | Sensitivity, dynamic range, interference, stability |

| Automation & Detection | 96-well plates (PCR, deep-well), Liquid handling robots, Plate readers, Microfluidic droplet generators | Automation of workflows and signal detection | Throughput, cost, reproducibility, data quality |

| Analytical Standards | Substrate and product standards, Reference enzymes, Calibration standards for instrumentation | Quality control and quantification | Purity, stability, appropriate concentration ranges |

Integrated Workflow for HTS in Enzyme Engineering

The most effective implementation of HTS in enzyme engineering involves the integration of multiple advanced approaches into a cohesive workflow. This integration maximizes the strengths of individual methods while mitigating their limitations. A proposed integrated workflow combines computational design, automated experimentation, and machine learning to create a powerful engine for enzyme optimization [25].

This integrated workflow begins with clearly defined engineering goals, which guide the computational design of mutant libraries. These libraries are then experimentally constructed and characterized using automated platforms, generating high-quality data that refines the computational models for subsequent design cycles. The continuous feedback between computation and experimentation creates a virtuous cycle of improvement that dramatically accelerates the enzyme engineering process compared to conventional approaches [23] [25].

The limitations of conventional enzyme engineering approaches—including restricted exploration of sequence space, low-throughput screening, and resource constraints—are being systematically addressed through advanced HTS solutions. The integration of sophisticated assay designs, automated platforms, and machine learning guidance has created a new paradigm in enzyme engineering that enables comprehensive exploration of fitness landscapes and rapid identification of optimized biocatalysts. The protocols and methodologies detailed in this application note provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing these advanced HTS approaches in their own enzyme engineering campaigns, potentially accelerating the development of novel biocatalysts for pharmaceutical, industrial, and sustainable chemistry applications. As these technologies continue to evolve and become more accessible, they promise to further democratize high-throughput enzyme engineering, enabling more researchers to contribute to the advancement of biocatalysis and the development of innovative bio-based solutions to complex challenges.

Advanced Methodologies: ML-Guided Platforms and Screening Applications

Machine-Learning Guided Cell-Free Expression Systems for Parallel Biocatalyst Development