Machine Learning in Biocatalysis: AI-Driven Discovery and Optimization of Enzymes for Biomedical Applications

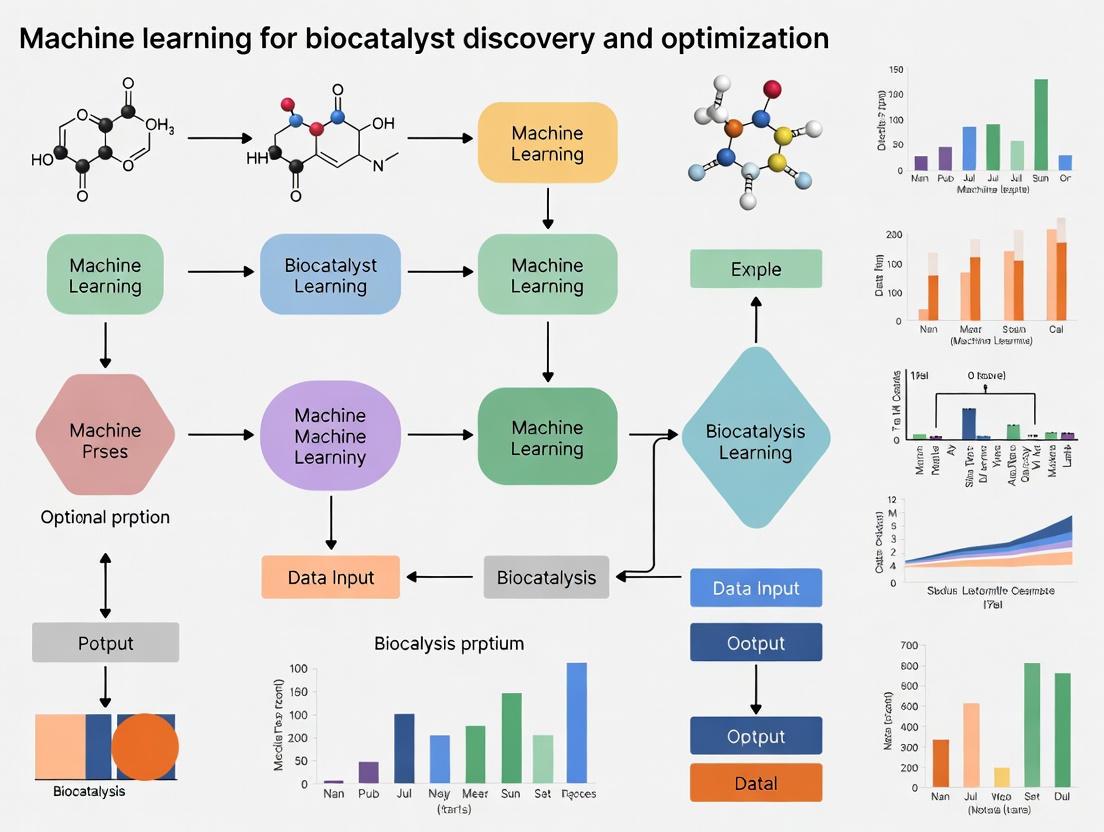

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in biocatalyst discovery and optimization for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Machine Learning in Biocatalysis: AI-Driven Discovery and Optimization of Enzymes for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the transformative role of machine learning (ML) in biocatalyst discovery and optimization for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of applying ML to enzyme engineering, detailing specific methodologies like protein language models and self-driving labs for predicting function and guiding directed evolution. The content addresses key challenges such as data scarcity and model generalization, compares the performance of various ML approaches, and validates their impact through real-world case studies in pharmaceutical synthesis. By synthesizing insights from recent 2025 research and expert perspectives, this article serves as a strategic guide for integrating computational intelligence into biocatalytic process development.

The New Frontier: How Machine Learning is Revolutionizing Biocatalyst Discovery

The exponential growth of protein sequence databases, with over 200 million entries in UniProt, has dramatically outpaced the capacity for experimental function annotation, a process that remains time-consuming and costly [1] [2]. Consequently, less than 1% of known protein sequences have experimentally verified functional annotations, creating a critical bottleneck in fields like biocatalyst discovery and drug development [3]. Computational methods, particularly those powered by machine learning, have emerged as essential tools for bridging this sequence-function gap. These methods leverage the information within vast sequence databases to predict protein function, often defined by the Gene Ontology (GO) framework which includes Molecular Function (MF), Biological Process (BP), and Cellular Component (CC) terms [4] [5]. However, a significant challenge persists in the "long-tail" distribution of available annotations, where a small number of GO terms are associated with many proteins, while a great many terms have very few annotated examples, leading to biased and incomplete predictions [6] [2]. This application note details state-of-the-art protocols and tools designed to overcome these hurdles, providing researchers with robust methodologies for accurate, large-scale protein function prediction.

Current State of Machine Learning Tools for Function Prediction

Recent advances in deep learning have produced a new generation of protein function prediction tools. These methods vary in their input data (e.g., sequence, structure, or literature) and their underlying architectures, leading to differences in their performance and applicability. The following table summarizes key tools and their benchmark performance as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of State-of-the-Art Protein Function Prediction Tools

| Tool Name | Core Methodology | Input Data | Reported Fmax (BP/CC/MF) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AnnoPRO [2] | Multi-scale representation (ProMAP & ProSIM) with dual-path CNN-DNN encoding | Protein Sequence | 0.650 / 0.681 / 0.681 (Overall best performer) | Effectively addresses the long-tail problem |

| DPFunc [3] | Graph Neural Network with domain-guided attention | Protein Structure & Sequence | 0.627 / 0.672 / 0.648 (After post-processing) | High interpretability; detects key functional residues |

| NetGO3 [2] | Not Specified | Protein Sequence | 0.633 / 0.681 / 0.668 (Best prior to AnnoPRO) | Previously top-performing tool on CAFA benchmarks |

| DeepGOPlus [2] | Deep Learning | Protein Sequence | 0.650 / 0.651 / 0.634 (Strong on BP) | Established baseline for sequence-based deep learning |

| PFmulDL [2] | Deep Learning | Protein Sequence | 0.619 / 0.682 / 0.667 (Strong on CC) | Good performance on Cellular Component terms |

| MSRep [6] | Neural Collapse-inspired representation learning | Protein Sequence | Superior on under-represented classes | Specifically designed for imbalanced data |

Detailed Protocols for Protein Function Annotation

Protocol 1: Sequence-Based Function Annotation Using AnnoPRO

AnnoPRO provides a high-performance, sequence-based annotation pipeline that is particularly effective for predicting functions in the long tail of under-represented GO terms [2].

Materials:

- Input: Protein amino acid sequence(s) in FASTA format.

- Software: AnnoPRO (https://github.com/idrblab/AnnoPRO).

- Dependencies: Python 3.8+, PyTorch, PROFEAT feature calculator, UMAP.

- Hardware: Recommended GPU (e.g., NVIDIA CUDA-compatible) for accelerated deep learning inference.

Procedure:

- Feature Extraction: For each input protein sequence, compute a comprehensive set of 1,484 sequence-derived features (e.g., amino acid composition, physicochemical properties, transition probabilities) using the PROFEAT tool integrated within the AnnoPRO pipeline.

- Multi-Scale Representation:

- Generate ProMAP (Feature Similarity-based Image):

- Calculate the pairwise cosine similarity between all 1,484 features to create a feature similarity matrix.

- Use UMAP (Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection) to reduce this matrix to a 2D coordinate layout, optimizing the placement of features to preserve their intrinsic correlations.

- Map the original feature intensities onto this 2D template to create an image-like representation (ProMAP) that captures local, non-linear relationships between features.

- Generate ProSIM (Protein Similarity-based Vector):

- Compute the pairwise cosine similarity between the feature vector of the target protein and feature vectors of all 92,120 proteins in the CAFA4 training set.

- Use the resulting 92,120-dimensional vector as the ProSIM representation, which embeds the target protein in a global context relative to known proteins.

- Generate ProMAP (Feature Similarity-based Image):

- Dual-Path Encoding:

- Feed the ProMAP image into a Seven-Channel Convolutional Neural Network (7C-CNN) to extract spatial patterns.

- Feed the ProSIM vector into a Deep Neural Network with five fully-connected layers (5FC-DNN) to extract global relational patterns.

- Concatenate the feature embeddings from both paths to form a unified protein representation.

- Function Prediction: Pass the unified representation through a Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) network, which is trained for multi-label classification across 6,109 GO terms.

- Output: The model outputs a list of predicted GO terms (BP, CC, and MF) along with their associated confidence scores.

Visualization of Workflow:

Protocol 2: Structure-Informed Function Annotation Using DPFunc

DPFunc leverages predicted or experimental protein structures to achieve high-accuracy, interpretable function predictions by focusing on functionally important domains and residues [3].

Materials:

- Input: Protein amino acid sequence(s). Optionally, an experimental structure (PDB format) or a predicted structure (e.g., from AlphaFold2/3 or ESMFold).

- Software: DPFunc, InterProScan, AlphaFold2/3 or ESMFold (if structure not available).

- Dependencies: Python, PyTorch, PyTorch Geometric (for GNNs).

- Hardware: GPU strongly recommended for structure prediction and GNN inference.

Procedure:

- Structure Acquisition:

- If an experimental structure is unavailable, use a structure prediction tool like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to generate a 3D atomic coordinate file from the target sequence.

- Construct a protein contact map from the 3D coordinates, typically based on Cβ atom distances (Cα for glycine).

- Residue-Level Feature Learning:

- Generate initial residue-level feature embeddings for the target sequence using a pre-trained protein language model (e.g., ESM-1b).

- Input the contact map (as a graph) and the residue embeddings (as node features) into a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) with a residual learning framework. The GCN propagates and updates features between neighboring residues in the 3D structure.

- Domain-Guided Attention:

- Use InterProScan to scan the target sequence against domain databases (e.g., Pfam, SMART) to identify functional domains present in the protein.

- Convert the identified domain entries into dense numerical vectors via an embedding layer.

- Apply an attention mechanism, inspired by transformer architectures, where the aggregated domain information acts as a guide (or "query") to weight the importance of each residue. Residues within or near key domains receive higher attention scores.

- Protein-Level Representation & Prediction:

- Create a final protein-level feature vector by performing a weighted sum of the GCN-refined residue features, using the attention scores from the previous step.

- Pass this feature vector through fully connected layers to predict GO terms.

- Post-Processing: Apply a rule-based post-processing step to ensure predicted GO terms comply with the hierarchical structure of the Gene Ontology (e.g., if a child term is predicted, its parent terms are also added).

- Output: A list of predicted GO terms. The model also provides interpretable outputs highlighting the residues and structural regions that most influenced the prediction.

Visualization of Workflow:

Successful implementation of the protocols above relies on a suite of key databases, software tools, and benchmarks.

Table 2: Essential Resources for Protein Function Prediction Research

| Resource Name | Type | Description | Primary Use in Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| UniProt Knowledgebase [4] [7] | Database | Comprehensive repository of protein sequence and functional annotation data. | Source of training sequences and benchmark annotations. |

| Gene Ontology (GO) [4] [5] | Ontology/Vocabulary | Standardized, hierarchical framework of functional terms (MF, BP, CC). | Universal vocabulary for describing and predicting protein functions. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [1] [3] | Database | Primary repository for experimentally determined 3D protein structures. | Source of structural data for structure-informed methods like DPFunc. |

| ProteinNet [8] [9] | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized dataset integrating sequences, structures, MSAs, and time-split training/validation/test sets. | Benchmarking and training machine learning models for structure and function prediction. |

| CAFA (Critical Assessment of Functional Annotation) [2] [3] | Community Challenge | A biennial blind assessment of protein function prediction methods. | Gold standard for evaluating and comparing the performance of new prediction tools. |

| InterProScan [3] | Software Tool | Integrates multiple databases to identify protein domains, families, and functional sites. | Detecting domain information to guide structure-based models (e.g., DPFunc). |

| AlphaFold/ESMFold [3] | Software Tool | Deep learning systems for highly accurate protein structure prediction from sequence. | Generating reliable 3D structural inputs when experimental structures are unavailable. |

Protein Language Models (PLMs) represent a transformative advancement in the field of machine learning for biocatalyst discovery and optimization. By treating amino acid sequences as sentences in a biological language, these models decode the complex relationships between protein sequence, structure, and function that govern enzyme fitness and stability. The integration of artificial intelligence into enzyme engineering has evolved through distinct phases: from classical machine learning approaches to deep neural networks, and now to sophisticated PLMs and emerging multimodal architectures [10]. This evolution is redefining the landscape of AI-driven enzyme design by replacing handcrafted features with unified token-level embeddings and shifting from single-modal models toward multimodal, multitask systems [10].

Within pharmaceutical and industrial applications, protein engineering faces persistent challenges in enhancing both stability and activity—two critical properties for engineered proteins [11]. Traditional methods like directed evolution and rational design typically demand extensive experimental screening or deep mechanistic insights into protein structures and functions [11]. PLMs offer a powerful alternative by learning the statistical patterns and biophysical principles embedded in millions of natural protein sequences, enabling researchers to predict the effects of sequence variations on enzyme properties without exhaustive experimental testing. This approach is particularly valuable for biocatalyst optimization, where small improvements in thermostability or catalytic efficiency can yield significant benefits in industrial processes and therapeutic development.

Core Architectural Frameworks

Protein Language Models primarily utilize transformer-based architectures, which have demonstrated remarkable capability in capturing long-range dependencies and contextual relationships within protein sequences. The foundational architecture consists of an encoder-decoder framework with multi-head self-attention mechanisms that process amino acid sequences as tokens. Unlike traditional natural language processing models, PLMs incorporate specialized adaptations for biological sequences, including structure-aware vocabulary and biophysically-informed positional embeddings [12] [11]. Two prominent architectural variations have emerged: bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT)-style models that use masked language modeling to learn context-aware representations, and autoregressive models that predict subsequent tokens in a sequence.

Recent innovations in PLM architecture include the integration of temperature-guided learning, where models are trained on sequences annotated with their host organism's optimal growth temperatures (OGTs) [11]. This approach enables the model to capture fundamental relationships between sequences and temperature-related attributes crucial for protein stability and function. Additionally, structure-aware models incorporate three-dimensional distance information between residues through relative positional embeddings, creating a more biophysically-grounded representation of protein space [12]. The continuous refinement of these architectural components is enhancing PLMs' ability to generalize across diverse protein families and predict nuanced functional characteristics.

Comparative Analysis of Leading PLMs

Table 1: Comparison of Key Protein Language Models for Enzyme Engineering

| Model Name | Architecture | Training Data | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| METL [12] | Transformer encoder with relative positional embedding | Biophysical simulation data via Rosetta (55 attributes across 30M variants) | Integrates molecular simulations; METL-Local (protein-specific) and METL-Global (general) variants | Excellent for small training sets (e.g., functional GFP variants with only 64 examples); position extrapolation |

| PRIME [11] | Transformer with MLM and OGT prediction modules | 96 million protein sequences with bacterial OGT annotations | Temperature-guided learning; zero-shot mutation prediction | Simultaneously improves stability and activity; outperforms on ProteinGym benchmark (score: 0.486) |

| ESM-2 [12] | Transformer-based masked language model | Evolutionary-scale natural protein sequences | Captures evolutionary constraints and patterns | General protein representation; gains advantage with larger training sets |

| SaProt [11] | Structure-aware transformer | Protein sequences and structural data | Incorporates structural vocabulary and constraints | Structure-function relationship prediction; scored 0.457 on ProteinGym benchmark |

| EVE [12] | Generative model (VAE) | Multiple sequence alignments | Evolutionary model of variant effect | Zero-shot variant effect prediction; often used as feature in ensemble models |

Experimental Validation and Performance Metrics

Quantitative Assessment Across Diverse Protein Families

Rigorous evaluation of PLM performance has been conducted across multiple experimental datasets representing proteins of varying sizes, folds, and functions. These assessments include green fluorescent protein (GFP), DLG4-Abundance, DLG4-Binding, GB1, GRB2-Abundance, GRB2-Binding, Pab1, PTEN-Abundance, PTEN-Activity, TEM-1, and Ube4b [12]. Such diverse benchmarking provides comprehensive insights into model generalizability and domain-specific performance. The ProteinGym benchmark, which encompasses diverse protein properties including catalytic activity, binding affinity, stability, and fluorescence intensity, has emerged as a standard for comparative evaluation [11]. In this benchmark, PRIME achieved a score of 0.486, significantly surpassing the second-best model, SaProt, which scored 0.457 (P = 1 × 10⁻⁴, Wilcoxon test) [11].

Performance evaluation often focuses on models' ability to learn from limited data, a critical consideration in protein engineering where experimental data is scarce and expensive to generate. Studies systematically evaluate performance as a function of training set size, revealing that protein-specific models like METL-Local consistently outperform general protein representation models on small training sets [12]. METL demonstrated remarkable efficiency by designing functional GFP variants when trained on only 64 sequence-function examples [12]. This data-efficient learning capability is particularly valuable for engineering novel enzymes with limited homologous sequences available for training.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of PLMs in Experimental Validation Studies

| Model | Test System | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| PRIME [11] | LbCas12a (1228 aa) | Melting temperature (T_m) improvement | 8-site mutant achieved T_m of 48.15°C (+6.25°C vs wild-type); 100% of 30 multisite mutants showed higher T_m |

| PRIME [11] | T7 RNA polymerase | Thermostability enhancement | 12-site mutant with T_m +12.8°C higher than wild-type |

| PRIME [11] | 5 distinct proteins | Success rate of single-site mutants | >30% of AI-selected mutations improved target properties (thermostability, activity, binding affinity) |

| METL [12] | 11 diverse protein datasets | Generalization from small training sets | Excelled with limited data; designed functional GFP variants from 64 examples |

| METL [12] | Multiple proteins | Position extrapolation capability | Strong performance in mutation, position, regime, and score extrapolation tasks |

Case Study: METL Framework Implementation

The METL (mutational effect transfer learning) framework operates through three methodical steps: synthetic data generation, synthetic data pretraining, and experimental data fine-tuning [12]. In the initial phase, researchers generate synthetic pretraining data via molecular modeling with Rosetta to model structures of millions of protein sequence variants. For each modeled structure, 55 biophysical attributes are extracted, including molecular surface areas, solvation energies, van der Waals interactions, and hydrogen bonding [12]. This comprehensive biophysical profiling creates a rich training dataset that captures fundamental physicochemical principles governing protein folding and function.

The subsequent pretraining phase involves training a transformer encoder to learn relationships between amino acid sequences and these biophysical attributes, forming an internal representation of protein sequences based on underlying biophysics. The transformer employs a protein structure-based relative positional embedding that considers three-dimensional distances between residues, incorporating spatial relationships often missing in sequence-only models [12]. The final fine-tuning phase adapts the pretrained transformer on experimental sequence-function data to produce a model that integrates prior biophysical knowledge with empirical observations. This staged approach enables the model to generalize effectively even with limited experimental data, as it begins with a strong biophysical foundation rather than learning solely from sparse experimental measurements.

Case Study: PRIME Validation Protocol

PRIME's validation exemplifies rigorous AI-guided protein engineering, employing a comprehensive workflow spanning computational prediction to experimental verification. The process begins with zero-shot mutation selection, where the model identifies promising single-site mutations without any experimental data from the target protein [11]. For LbCas12a engineering, researchers conducted an iterative optimization process through three rounds of mutagenesis and experimental validation [11]. This iterative approach allowed for the exploration of epistatic interactions, where certain individually negative single-site mutations could be combined into positive multi-site mutants—insights typically elusive in conventional protein engineering.

Experimental validation of PRIME-designed variants included detailed biophysical characterization, particularly measuring thermal stability through melting temperature (T_m) determinations. For the complex multidomain protein LbCas12a (1228 amino acids), the final round of optimization produced 30 multisite mutants, all exhibiting higher T_m values than the wild type [11]. The best-performing eight-site mutant achieved a T_m of 48.15°C, representing a significant 6.25°C improvement over the wild type [11]. Similarly, for T7 RNA polymerase, PRIME guided the design and validation of 95 mutants, ultimately yielding a 12-site mutant with a melting temperature 12.8°C higher than wild type [11]. These substantial improvements demonstrate PRIME's capacity to address real-world protein engineering challenges with exceptional efficiency.

Practical Implementation Guide

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for PLM Applications

| Resource/Tool | Type | Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta [12] | Molecular modeling suite | Generate synthetic training data; compute biophysical attributes (surface areas, solvation energies, van der Waals interactions) | Downloadable |

| UniProtKB [13] | Protein sequence database | Source of canonical sequences and feature information (isoforms, variants, cleavage sites) | Public database |

| ProtGraph [13] | Python package | Convert protein entries to graph structures; analyze feature-induced peptides | PyPI/GitHub |

| plotnineSeqSuite [14] | Python visualization package | Create sequence logos, alignment diagrams, and sequence histograms | PyPI/GitHub |

| ProteinGym [11] | Benchmarking dataset | Comprehensive assessment of variant effects across diverse protein properties | Public benchmark |

Protocol for Zero-Shot Mutation Prediction Using PRIME

Purpose: To identify stability-enhancing mutations for a target enzyme without experimental training data.

Procedure:

- Input Sequence Preparation: Obtain the wild-type amino acid sequence of the target enzyme in FASTA format. Ensure sequence accuracy through verification against reference databases.

- Model Configuration: Access PRIME through its available implementation. The model requires no specialized configuration for zero-shot prediction, as it leverages its pretrained knowledge from 96 million bacterial protein sequences with OGT annotations [11].

- Mutation Scanning: For each position in the enzyme sequence, generate all 19 possible amino acid substitutions. PRIME will compute a predictive score for each mutation, reflecting its anticipated impact on stability and activity.

- Variant Prioritization: Rank mutations based on the model's output scores. Select top-ranking single-site mutants for experimental validation, typically focusing on the highest 1-2% of predictions.

- Experimental Validation: Clone, express, and purify the selected variants. Assess thermostability through thermal shift assays or differential scanning calorimetry to determine melting temperature (T_m) changes.

- Iterative Optimization: Combine promising mutations from the first round into multi-site variants for subsequent rounds of prediction and validation, leveraging potential epistatic interactions [11].

Technical Notes: The zero-shot capability of PRIME stems from its temperature-guided training, which establishes correlations between sequence patterns and thermal adaptation [11]. This protocol typically identifies beneficial mutations with a success rate exceeding 30% [11].

Protocol for Limited-Data Engineering Using METL

Purpose: To optimize enzyme properties when only small experimental datasets (<100 variants) are available.

Procedure:

- Base Model Selection: Choose between METL-Local (for protein-specific optimization) or METL-Global (for broader applicability) based on project needs. METL-Local typically outperforms on small training sets for a specific protein [12].

- Synthetic Data Generation (METL-Local only): If using METL-Local, generate sequence variants of the target protein with up to five random amino acid substitutions. Use Rosetta to model structures and compute 55 biophysical attributes for approximately 20 million variants [12].

- Model Pretraining: Pretrain the transformer encoder on the synthetic data to learn sequence-biophysical relationships. This establishes a biophysical foundation for the specific protein landscape.

- Experimental Data Preparation: Assemble available experimental measurements of the target property (e.g., activity, stability) for known variants. Even dozens of examples can suffice for effective fine-tuning [12].

- Model Fine-tuning: Adapt the pretrained model on the experimental data using transfer learning. This process integrates biophysical principles with empirical observations.

- Prediction and Design: Use the fine-tuned model to screen in silico variant libraries or generate novel sequences with optimized properties.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize and test top-predicted variants to confirm model predictions and iteratively refine the model.

Technical Notes: METL's structure-based relative positional embedding incorporates 3D distances between residues, enhancing its biophysical accuracy [12]. The framework has successfully engineered functional GFP variants with as few as 64 training examples [12].

Visualization of PLM Workflows

METL Framework Architecture

METL Framework: This diagram illustrates the three-stage METL architecture that integrates biophysical simulation with experimental data through transfer learning [12].

PRIME Model Architecture

PRIME Model Architecture: This visualization shows the dual-objective training of PRIME, combining masked language modeling with temperature prediction to capture stability-function relationships [11].

The field of protein language models is rapidly evolving toward multimodal architectures that integrate sequence, structure, and biophysical information [10]. Future developments will likely include dynamic simulations of enzyme function, moving beyond static structure prediction to model conformational changes and catalytic mechanisms [10]. The emergence of intelligent agents capable of reasoning represents another frontier, where PLMs could autonomously design experimental strategies and interpret complex results [10]. Additionally, the integration of more sophisticated biophysical simulations and experimental data types will enhance model accuracy and biological relevance.

Protein language models have fundamentally transformed our approach to decoding the hidden grammar of enzyme fitness and stability. By leveraging the statistical patterns in evolutionary data and integrating biophysical principles, PLMs like METL and PRIME enable efficient protein engineering with limited experimental data. Their demonstrated success in enhancing thermostability, catalytic activity, and other key enzyme properties underscores their value for biocatalyst discovery and optimization. As these models continue to evolve, they will play an increasingly central role in bridging computational insights with practical enzyme engineering efforts, accelerating applications in synthetic biology, metabolic engineering, and pharmaceutical development.

The engineering of robust and efficient biocatalysts is a central goal in industrial biotechnology and drug development. For decades, directed evolution has served as a primary method for enzyme improvement, yet it often requires extensive experimental screening and can be hampered by complex, non-additive mutational interactions, known as epistasis [15]. The ability to accurately predict the functional consequences of mutations—on stability, activity, and selectivity—before embarking on laborious lab work would dramatically accelerate enzyme design. Machine Learning (ML) is now making this possible by learning the complex sequence-structure-function relationships from vast biological datasets, allowing researchers to navigate the protein fitness landscape more intelligently [15].

This Application Note details how ML models, particularly those leveraging multimodal deep learning, are being used to predict mutation effects. We place special emphasis on providing actionable protocols and resources, framed within the broader thesis that ML is becoming an indispensable tool for the discovery and optimization of biocatalysts.

Core ML Approaches and Performance Benchmarks

Various ML architectures have been developed to tackle the challenge of predicting mutation effects. Their performance, applicability, and data requirements differ significantly, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Models for Predicting Mutation Effects

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Input Features | Performance Highlights | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ProMEP [16] | Multimodal deep representation learning; MSA-free | Sequence & atomic-level structure context | Spearman's correlation: 0.53 on protein G dataset (multiple mutations); ~0.523 average on ProteinGym benchmark [16] | + State-of-the-art (SOTA) performance; + MSA-free, 2-3 orders of magnitude faster than MSA-based methods; + Zero-shot prediction [16] |

| AlphaMissense [16] | Structure-aware model using AlphaFold principles; MSA-based | Sequence, MSA-derived evolutionary data, & structure | Spearman's correlation: ~0.523 average on ProteinGym benchmark [16] | + SOTA performance; - Relies on MSA, which is computationally slow [16] |

| ESM Models (e.g., ESM-1v, ESM-2) [16] | Protein Language Models (pLMs); MSA-free | Protein sequence only | Performance generally lower than multimodal approaches like ProMEP [16] | + Unsupervised, MSA-free, and fast; - Lacks explicit structure context, limiting accuracy [16] |

| CLEAN [17] | Contrastive learning for enzyme function | Enzyme sequence | High accuracy in predicting Enzyme Commission (EC) numbers and promiscuous activity [17] | + Effective for functional annotation and discovery; - Focused on function prediction, not direct mutational effect |

| RFdiffusion [17] | Generative model based on RoseTTAFold | Protein backbone structure | Designed 41/41 scaffolds around active sites in a benchmark (vs. 16/41 for earlier version) [17] | + Powerful for de novo enzyme design and scaffold generation; - Not a direct mutational effect predictor |

The field is moving toward models that integrate multiple data types. For instance, ProMEP uses a multimodal architecture that processes both sequence and atomic-level structure information from point cloud data, leading to superior performance on benchmarks involving single and multiple mutations [16]. A critical development is the emergence of zero-shot predictors, which can make accurate predictions without needing experimental data for the specific protein, thereby overcoming a major bottleneck of data scarcity [15] [16].

Experimental Protocols for ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step protocol for a typical ML-guided enzyme engineering campaign, from data generation to model-assisted design. The workflow is also visualized in Figure 1.

Protocol: ML-Assisted Directed Evolution of a Biocatalyst

Objective: Enhance a specific enzymatic property (e.g., activity at neutral pH) using machine learning to prioritize variants for experimental testing.

Pre-requisites:

- A gene encoding the wild-type enzyme of interest.

- A robust high-throughput assay for the desired function (e.g., colorimetric, fluorescence-based).

- Access to a next-generation sequencer for deep mutational scanning (DMS) library sequencing.

Figure 1: Workflow for ML-guided enzyme engineering. The iterative 'learn-predict-test' cycle (Steps 3-6) efficiently navigates the fitness landscape.

Procedure:

Generate Initial Training Data

- Create a diverse library of enzyme variants. This can be achieved through site-saturation mutagenesis at suspected hotspot residues, random mutagenesis, or by constructing a combinatorial library based on rational design.

- Use a high-throughput method (e.g., microtiter plates) to screen the library, measuring the target property (e.g., activity at different pH levels) [18].

- For each variant, ensure you have both the sequence (determined via NGS) and the corresponding functional readout (e.g., specific activity). This creates the labeled dataset for ML training.

Train and Validate the ML Model

- Feature Engineering: Represent each variant using features such as one-hot encoding of mutations, physicochemical properties, or embeddings from a pre-trained protein Language Model (pLM) like ESM-2 [15] [16].

- Model Selection: For smaller datasets (< 10,000 variants), start with simpler models like Gaussian Process Regression or Random Forests, which are less prone to overfitting. For larger, more complex datasets, neural networks can be explored.

- Training & Validation: Split your data into training and test sets (e.g., 80/20). Train the model to predict the functional score from the variant features. Validate its predictive power on the held-out test set.

In Silico Prediction and Variant Prioritization

- Use the trained model to score a vast number of in silico generated variants, including single and multiple mutants that were not in the original library. This allows you to explore the fitness landscape beyond experimentally sampled points [15].

- The model will predict the fitness (e.g., activity score) for each virtual variant. Rank them based on the predicted score.

- Select the top 50-100 predicted variants for synthesis and testing. This step dramatically narrows the experimental search space.

Experimental Validation and Model Iteration

- Synthesize the genes for the top-predicted variants and express the proteins.

- Characterize these variants using the same functional assay from Step 1. This provides a new set of ground-truth data.

- Compare the model's predictions with the experimental results. If performance is unsatisfactory, or to further optimize, the new data can be added to the training set, and the model can be retrained for another round of prediction (a process known as active learning or the design-build-test-learn cycle) [15].

Troubleshooting:

- Poor Model Generalization: If the model performs well on training data but poorly on new variants, the initial dataset might be too small or lack diversity. Expand the training library or incorporate transfer learning from a pre-trained pLM.

- Data Quality: Ensure high consistency in the experimental screening data, as noise can severely degrade model performance [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of ML-guided protein engineering relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. Table 2 lists essential resources as a starting point for building a pipeline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Protein Engineering

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow | Reference/Link |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProMEP | Computational Model | Zero-shot prediction of mutation effects on protein function; guides engineering without initial experimental data. | [16] |

| ESM-2 & ProtTrans | Protein Language Model (pLM) | Generates meaningful numerical representations (embeddings) of protein sequences for use as features in ML models. | [15] [19] |

| AlphaFold DB | Database | Provides access to millions of predicted protein structures, serving as input for structure-aware ML models like ProMEP. | [17] [16] |

| ProteinMPNN | Computational Algorithm | Solves the inverse folding problem: designs amino acid sequences that will fold into a desired protein backbone structure. | [17] |

| RFdiffusion | Generative AI Model | De novo design of novel protein backbone structures that can be conditioned to contain specific functional motifs (e.g., active sites). | [17] |

| EnzymeMiner | Web Tool / Database | Automated mining of protein databases to discover and select soluble enzyme candidates for a target reaction. | [15] |

| FireProtDB & SoluProtMutDB | Database | Curated databases of mutational effects on protein stability and solubility; useful for training or validating stability predictors. | [15] |

| ProteinGym | Benchmarking Suite | A comprehensive benchmark for evaluating the performance of mutation effect predictors across a wide range of proteins and assays. | [19] [16] |

Case Study: ML-Guided Optimization of a Transaminase at Neutral pH

A recent study exemplifies the practical application of these protocols. The goal was to improve the catalytic activity of a transaminase from Ruegeria sp. under neutral pH conditions, where its performance was suboptimal [18].

Methodology:

- Data Generation: The researchers created a library of transaminase variants and measured their activity under a range of pH conditions.

- Model Training: This high-quality experimental data was used to train a machine learning model to predict catalytic activity as a function of pH and sequence variation.

- Prediction & Validation: The trained model was used to predict highly active variants at pH 7.5. The top candidates were synthesized and tested.

Results: The ML-guided approach successfully identified variants with up to a 3.7-fold increase in activity at the target pH of 7.5 compared to the starting template [18]. This demonstrates the power of ML to co-optimize enzyme activity and complex properties like pH dependence, a task that is challenging for traditional methods.

The integration of machine learning into biocatalyst engineering represents a paradigm shift. By using ML models to predict the impact of mutations on activity, selectivity, and stability, researchers can now navigate the protein fitness landscape with unprecedented efficiency. As summarized in this document, the combination of multimodal zero-shot predictors, structured experimental protocols, and an evolving toolkit of computational resources provides a robust framework for accelerating the development of industrial enzymes and therapeutics. The future of the field lies in improving data quality and quantity, developing more generalizable models, and further tightening the iterative loop between computational prediction and experimental validation [15].

The field of biocatalysis is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving beyond the constraints of natural evolutionary history to access entirely novel regions of the protein functional universe. The known diversity of natural proteins represents merely a fraction of what is theoretically possible; the sequence space for a modest 100-residue protein encompasses ~20100 possibilities, vastly exceeding the number of atoms in the observable universe [20]. Conventional protein engineering strategies, particularly directed evolution, have proven powerful for optimizing existing scaffolds but remain fundamentally tethered to nature's blueprint, performing local searches in the vastness of the protein functional landscape [20]. This approach is inherently limited in its ability to access genuinely novel catalytic functions or structural topologies not explored by natural evolution.

Generative artificial intelligence (AI) models are transcending these limitations by enabling the de novo design of enzymes with customized functions. These models learn the complex mappings between protein sequence, structure, and function from vast biological datasets, allowing researchers to computationally create stable protein scaffolds and functional active sites that have no natural counterparts [20]. This Application Note examines the latest generative AI methodologies, provides detailed protocols for their implementation, and presents quantitative performance data, framing these advances within the broader context of machine learning-driven biocatalyst discovery and optimization.

Foundational Methodologies in AI-Driven Enzyme Design

Key Computational Architectures and Tools

Several complementary AI architectures form the backbone of modern de novo enzyme design. The table below summarizes the primary model types, their applications, and representative tools.

Table 1: Key Generative Model Architectures for De Novo Enzyme Design

| Model Type | Primary Function | Key Tools/Examples | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Language Models (e.g., Evo) | Generate novel protein sequences conditioned on functional context or prompts. | Evo Model [21] | Captures functional relationships from genomic context; high experimental success rates for multi-component systems. | Limited to prokaryotic design contexts; requires careful prompt engineering. |

| Protein Structure Prediction Networks | Predict 3D protein structure from amino acid sequences. | AlphaFold 2 & 3 [22] [23] [24] | Rapid, accurate structure prediction; essential for validating de novo designs. | Does not generate novel sequences; predictive accuracy for designed proteins requires further validation. |

| Protein Language Models (pLMs) | Learn evolutionary constraints from sequence databases to generate plausible novel sequences. | ESM-2 [15] | Zero-shot prediction of protein fitness; no experimental data required for initial designs. | May be biased towards natural sequence space; limited explicit structural awareness. |

| Diffusion Models & Inverse Folding | Generate sequences for a given protein backbone structure. | RFdiffusion [20] | Creates sequences for novel backbone architectures; enables precise scaffolding of active sites. | High computational cost; success depends on the quality of the input structure. |

The Semantic Design Workflow with Genomic Language Models

The "semantic design" approach, exemplified by the Evo model, leverages the natural colocalization of functionally related genes in prokaryotic genomes [21]. By learning the distributional semantics of genes—"you shall know a gene by the company it keeps"—Evo can perform a genomic "autocomplete," generating novel DNA sequences enriched for a target function when prompted with the genomic context of a known function. The following diagram illustrates this core logical workflow.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Case Study: Designing an Artificial Metathase for Cytoplasmic Olefin Metathesis

A recent landmark study demonstrated the integration of a tailored abiotic cofactor (a Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst derivative, Ru1) into a hyper-stable, de novo-designed protein scaffold (dnTRP) to create an artificial metathase functional within E. coli cytoplasm [25]. The quantitative performance metrics before and after optimization are summarized below.

Table 2: Performance Metrics for the De Novo Designed Artificial Metathase [25]

| Parameter | Initial Design (dnTRP_18) | After Affinity Optimization (dnTRP_R0) | After Directed Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cofactor Binding Affinity (KD) | 1.95 ± 0.31 μM | ≤ 0.2 μM (e.g., 0.16 ± 0.04 μM for F116W) | Not explicitly reported (improved activity implied) |

| Turnover Number (TON) | ~194 ± 6 | Not explicitly reported | ≥ 1,000 |

| Thermal Stability (T50) | > 98°C | Maintained > 98°C | Maintained |

| Performance Enhancement | ~4.8x over free Ru1 cofactor | ~10x improved affinity over initial design | ≥ 12x over initial design |

Protocol: Computational Design and Directed Evolution of the Artificial Metathase

Step 1: De Novo Scaffold Design

- Objective: Design a hyper-stable protein scaffold (dnTRP) with a pre-organized hydrophobic pocket to accommodate the Ru1 cofactor and facilitate catalysis.

- Methods:

- Use the RifGen/RifDock suite to enumerate interacting amino acid rotamers and dock the Ru1 cofactor into cavities of de novo-designed closed alpha-helical toroidal repeat proteins [25].

- Subject docked structures to protein sequence optimization using Rosetta FastDesign to refine hydrophobic contacts and stabilize key hydrogen-bonding residues.

- Select top designs based on computational metrics describing the protein-cofactor interface and binding pocket pre-organization.

- Output: A set of 21 initial dnTRP designs for experimental testing.

Step 2: Protein Expression and Primary Screening

- Objective: Identify the most promising scaffold from the computational designs.

- Methods:

- Express the 21 dnTRPs in E. coli with an N-terminal hexa-histidine tag. Analyze expression levels via SDS-PAGE.

- Purify soluble proteins using nickel-affinity chromatography.

- Assay RCM activity by incubating purified dnTRPs (with 0.05 equiv. of Ru1 cofactor) in the presence of diallylsulfonamide substrate (5,000 equiv. vs. Ru1) for 18 hours at pH 4.2.

- Quantify turnover numbers (TONs) to select the lead scaffold (e.g., dnTRP_18 with TON 194 ± 6) [25].

Step 3: Binding Affinity Optimization

- Objective: Improve cofactor binding affinity to ensure near-quantitative binding at low micromolar concentrations.

- Methods:

- Identify residues near the binding site (e.g., F43, F116) for mutagenesis to increase hydrophobicity and π-stacking potential.

- Generate and purify point mutants (e.g., F43W, F116W).

- Determine binding affinity (KD) using a tryptophan fluorescence-quenching assay. Mutant dnTRP_R0 (F116W) achieved a KD of 0.16 ± 0.04 μM [25].

Step 4: Directed Evolution in a Cell-Free Extract (CFE) System

- Objective: Further enhance catalytic performance under biologically relevant conditions.

- Methods:

- Prepare E. coli CFE at pH 4.2 (optimal for Ru1 binding affinity).

- Supplement the reaction mixture with 5 mM bis(glycinato)copper(II) [Cu(Gly)2] to partially oxidize and inactivate glutathione, which can deactivate the cofactor [25].

- Use the CFE system to screen Ru1·dnTRP_R0 libraries generated via directed evolution.

- Identify evolved variants exhibiting a ≥12-fold increase in TON (TON ≥ 1,000) compared to the initial design while maintaining excellent biocompatibility [25].

Case Study: Semantic Design of Functional De Novo Genes with Evo

The Evo genomic language model enables function-guided design by learning from the statistical patterns in prokaryotic genomes, where functionally related genes are often clustered [21]. The following workflow details the protocol for generating novel toxin-antitoxin systems.

Protocol: Semantic Design of Type II Toxin-Antitoxin (T2TA) Systems

Step 1: Prompt Curation and Sequence Generation

- Objective: Generate novel, functionally diversified T2TA pairs.

- Methods:

- Prompt Engineering: Curate a set of eight different prompt types, including known toxin or antitoxin sequences, their reverse complements, and the upstream or downstream genomic contexts of known T2TA loci [21].

- Sequence Generation: Use Evo 1.5 to sample novel DNA sequences conditioned on these prompts.

Step 2: In Silico Filtering and Selection

- Objective: Filter generated sequences to identify the most promising candidates for experimental testing.

- Methods:

- Filter generations for sequences encoding protein pairs that exhibit in silico predicted complex formation.

- Apply a novelty filter, requiring at least one component to have limited sequence identity (<70% identity) to known T2TA proteins [21].

- Select candidate sequences for synthesis.

Step 3: Experimental Validation of Toxin-Antitoxin Pairs

- Objective: Confirm the function of generated T2TA pairs.

- Methods:

- Toxin Activity Assay: Express the generated toxin gene in E. coli and measure growth inhibition using a relative survival assay. A successful example, EvoRelE1, showed ~70% reduction in relative survival [21].

- Conjugate Antitoxin Design and Validation: Prompt Evo 1.5 with the sequence of the active, generated toxin (EvoRelE1) to generate conjugate antitoxins. Filter outputs as in Step 2.

- Neutralization Assay: Co-express the generated toxin and antitoxin. A functional pair will show restored bacterial growth, confirming the antitoxin's neutralizing activity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Databases

Successful de novo enzyme design relies on a suite of computational and experimental resources. The following table catalogues key tools and their applications.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Resources for AI-Driven De Novo Enzyme Design

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in De Novo Design | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evo Model | Generative Genomic Language Model | Function-guided generation of novel protein sequences via "semantic design" using genomic context prompts. | Available for research [21] |

| AlphaFold Protein Structure Database | Database | Provides over 200 million predicted protein structures for natural proteins; useful for homology analysis and model validation. | Open access (CC-BY 4.0) [24] |

| AlphaFold Server (AlphaFold 3) | Prediction Tool | Predicts the 3D structure of proteins and their complexes with ligands, DNA, and RNA; vital for assessing designed proteins. | Free for non-commercial research [22] |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | Physics-based protein modeling and design; used for energy minimization and refining AI-generated designs. | Academic license available [20] |

| SynGenome | AI-Generated Database | Database of over 120 billion base pairs of AI-generated genomic sequences; enables semantic design across diverse functions. | Openly available [21] |

| Ru1 Cofactor | Synthetic Organometallic Cofactor | A tailored Hoveyda-Grubbs catalyst derivative with a polar sulfamide group for supramolecular anchoring in designed scaffolds. | Synthesized in-lab [25] |

| De Novo-Designed Protein Scaffold (dnTRP) | Hyper-stable Protein Scaffold | A hyper-stable, computationally designed scaffold providing a hospitable environment for abiotic cofactors in cellular environments. | Designed and expressed in-lab [25] |

The integration of generative AI into enzyme design marks a profound transition from exploring nature's existing repertoire to actively writing new sequences and functions into the protein universe. Methodologies like semantic design with Evo and the integration of de novo scaffolds with abiotic cofactors, as demonstrated by the artificial metathase, are providing researchers with an unprecedented capacity to create bespoke biocatalysts. These AI-driven tools are poised to dramatically accelerate the discovery and optimization of enzymes for applications in therapeutic development, sustainable chemistry, and synthetic biology, fundamentally expanding the functional potential of proteins beyond the constraints of natural evolution.

From Code to Catalyst: Practical ML Methods and Real-World Applications

The field of biocatalysis, which utilizes enzymes and living systems to mediate chemical reactions, is being transformed by machine learning (ML). ML techniques are accelerating the discovery, optimization, and engineering of biocatalysts, offering innovative approaches to navigate the complex relationship between enzyme sequence, structure, and function [15]. The exponential growth in biological data, including protein sequences and structures, has created a critical need for advanced computational tools capable of extracting meaningful patterns to guide research [26] [15]. This document provides application notes and detailed protocols for three pivotal ML architectures—Transformer models, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), and Graph-Based Networks—within the context of biocatalyst discovery and optimization research for scientists and drug development professionals.

Core ML Architectures: Principles and Biocatalytic Applications

Transformer Models

Principles: Transformer models leverage a self-attention mechanism to weigh the significance of different parts of the input data, enabling them to capture long-range dependencies and complex contextual relationships. Originally developed for natural language processing (NLP), their architecture is particularly suited for biological sequences and structures, which can be treated as "texts" written in the "languages" of nucleotides or amino acids [15] [27]. Protein Language Models (PLMs) like ProtT5, Ankh, and ESM2 are transformer-based models pre-trained on vast corpora of protein sequences, learning fundamental principles of protein folding and function [15].

Biocatalytic Applications: In biocatalysis, transformers are primarily used for functional annotation and enzyme engineering. They can predict enzyme function from sequence, even for poorly characterized proteins, by transferring knowledge from well-annotated families [15]. Furthermore, they serve as powerful zero-shot predictors, capable of suggesting functional protein sequences without the need for labeled experimental data on the specific target, thereby accelerating the initial design phase [15]. A novel application involves converting gene regulatory network structures into text-like sequences using random walks, which are then processed by a BERT model (a type of transformer) to generate global gene embeddings, integrating structural knowledge for enhanced inference [28].

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs)

Principles: CNNs are a class of deep neural networks that use convolutional layers to extract hierarchical features from data with grid-like topology. Their defining characteristics are local connectivity and weight sharing, which allow them to efficiently detect local patterns—such as motifs in a protein sequence—while reducing the number of parameters compared to fully connected networks [29]. A standard CNN architecture comprises convolutional layers, activation functions (e.g., ReLU), pooling layers for dimensionality reduction, and fully connected layers for final prediction [29].

Biocatalytic Applications: CNNs are highly versatile in processing various one-dimensional biological data. They are used for predicting single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and regulatory regions in DNA, identifying DNA/RNA binding sites in proteins, and forecasting drug-target interactions [29]. A significant advantage of CNNs is their ability to analyze high-dimensional datasets with minimal pre-processing. By transforming non-image data (e.g., sequence or assay data) into pseudo-images, CNNs can detect subtle variations and patterns often dismissed as noise, providing a more nuanced view of the enzyme fitness landscape [27].

Graph-Based Networks (Graph Neural Networks - GNNs)

Principles: GNNs operate directly on graph-structured data, making them ideal for representing molecules and proteins. In a graph, nodes represent entities (e.g., atoms, amino acids), and edges represent relationships or bonds (e.g., chemical bonds, spatial proximity). GNNs learn node embeddings by iteratively aggregating information from a node's neighbors, effectively capturing the topological structure and physicochemical properties of the molecular system [30]. Advanced variants like SE(3)-equivariant GNNs are designed to be invariant to rotations and translations in 3D space, a critical property for correctly modeling molecular structures and interactions [31].

Biocatalytic Applications: GNNs excel at predicting enzyme-substrate interactions and substrate specificity by modeling the precise spatial and chemical environment of enzyme active sites. For instance, the EZSpecificity model, a cross-attention-empowered SE(3)-equivariant GNN, was trained on a comprehensive database of enzyme-substrate interactions and demonstrated a 91.7% accuracy in identifying reactive substrates, significantly outperforming previous state-of-the-art models [31]. Furthermore, frameworks like BioStructNet use GNNs to integrate protein and ligand structural data, employing transfer learning to achieve high predictive accuracy even with small, function-specific datasets, such as those for Candida antarctica lipase B (CalB) [30].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Key ML Architectures in Biocatalysis

| Architecture | Core Strength | Typical Input Data | Primary Biocatalysis Applications | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transformer Models | Capturing long-range, contextual dependencies | Protein/DNA sequences, Text-based representations | Function annotation, De novo enzyme design, Zero-shot fitness prediction | Exceptional generalization from pre-training on large unlabeled datasets [15] |

| Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) | Detecting local patterns and motifs | 1D sequences, 2D pseudo-images, SMILES strings | SNP & binding site prediction, Drug-target interaction, Promiscuity pattern analysis | Robustness to noise; can analyze full, high-dimensional data without aggressive filtering [29] [27] |

| Graph-Based Networks (GNNs) | Modeling relational and topological structure | Molecular graphs, Protein structures (contact maps) | Substrate specificity prediction, Enzyme-ligand binding affinity, Kinetic parameter prediction | Directly incorporates 3D structural information for mechanistic insights [31] [30] |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Predicting Substrate Specificity with a Graph-Based Network (EZSpecificity)

Objective: To accurately predict the substrate specificity of an enzyme using a structure-based graph neural network.

Materials:

- Hardware: Computer with a high-performance GPU (e.g., NVIDIA A100 or equivalent).

- Software: Python 3.8+, PyTorch or TensorFlow, Deep Graph Library (DGL) or PyTorch Geometric.

- Data:

- Enzyme 3D structure (from PDB or predicted via AlphaFold2).

- Candidate substrate structures (in SDF or SMILES format).

- A curated database of enzyme-substrate interactions for model training/fine-tuning.

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Enzyme Graph Construction: Represent the enzyme structure as a graph. Each amino acid residue is a node. Node features can include physicochemical properties (e.g., charge, hydrophobicity). Edges are formed between α-carbons within a defined spatial cutoff (e.g., 10 Å), with edge weights potentially representing distances [30].

- Substrate Graph Construction: Represent the candidate substrate as a graph. Atoms are nodes (featurized by atom type, hybridization), and bonds are edges (featurized by bond type).

- Complex Representation: Form a joint graph or use a cross-attention mechanism to model interactions between the enzyme and substrate graphs [31].

Model Setup:

- Employ an SE(3)-equivariant graph neural network architecture. This ensures predictions are invariant to the rotation and translation of the input structures, a crucial property for meaningful biological predictions [31].

- Integrate a cross-attention module between the enzyme and substrate graphs. This allows the model to dynamically focus on specific parts of the enzyme in the context of a given substrate and vice versa.

Training:

- If using a pre-trained model (recommended), fine-tune it on your specific enzyme family dataset.

- Use a binary cross-entropy loss function for specificity classification (reactive/non-reactive).

- Optimize using the Adam optimizer with a learning rate scheduler (e.g., reduce on plateau).

Validation:

- Perform rigorous k-fold cross-validation (e.g., 5-fold) on the labeled data.

- Validate model predictions experimentally using a high-throughput activity assay with the top predicted substrates. Compare the experimentally confirmed hits against the model's predictions to calculate accuracy, as demonstrated in the EZSpecificity study which achieved 91.7% experimental accuracy [31].

Protocol: Optimizing Enzymes with Transformer-Based Fitness Prediction

Objective: To guide directed evolution campaigns by predicting the fitness of enzyme variants using a protein language model.

Materials:

- Hardware: Computer with a modern GPU.

- Software: Hugging Face Transformers library, PyTorch/TensorFlow.

- Data:

- A multiple sequence alignment (MSA) for the protein family of interest.

- A labeled dataset of enzyme variants and their corresponding functional scores (e.g., activity, thermostability) from a preliminary screen.

Procedure:

- Model Selection:

- Select a pre-trained transformer-based PLM, such as ESM-2 or ProtT5, from the Hugging Face model hub [15].

Feature Extraction:

- Pass your library of wild-type and variant enzyme sequences through the pre-trained PLM to extract sequence embeddings. These embeddings are dense numerical vectors that encode structural and functional information.

Fine-Tuning (Transfer Learning):

- Add a regression or classification head on top of the base PLM, depending on whether you are predicting a continuous fitness score or a categorical label.

- Fine-tune the entire model or just the final layers on your smaller, task-specific dataset of variant fitness scores. This process transfers the general knowledge of the PLM to your specific enzyme engineering problem [15] [30].

- Techniques like Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA) can be used for parameter-efficient fine-tuning, reducing computational cost and the risk of overfitting on small datasets [30].

Prediction and Library Design:

- Use the fine-tuned model to score a virtual library of enzyme variants.

- Select the top-predicted variants for synthesis and experimental testing, focusing the experimental effort on the most promising regions of the sequence space.

Iterative Learning:

- Incorporate the new experimental data from the tested variants back into the training set.

- Re-train or further fine-tune the model in an iterative "design-build-test-learn" cycle to continuously improve its predictive power and guide the optimization process.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for ML-Guided Biocatalysis

| Reagent / Resource | Function / Description | Example Sources / Formats |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-trained Protein Language Models (PLMs) | Provide foundational knowledge of protein sequences for transfer learning and zero-shot prediction. | ESM-2, ProtT5, Ankh (Hugging Face) [15] |

| Protein Structure Prediction Tools | Generate 3D protein structures from amino acid sequences for structure-based ML models. | AlphaFold2, RosettaCM, ESMFold [15] [30] |

| Curated Enzyme Activity Databases | Serve as labeled training data for supervised learning of enzyme function and substrate scope. | BRENDA, UniProt, function-specific literature compilations [31] |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulation Software | Validate ML predictions by simulating enzyme-ligand complexes and analyzing key interactions. | GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD [30] |

| High-Throughput Screening Assays | Generate high-quality experimental data for training and validating ML models on enzyme variants. | Fluorescence, absorbance, or mass spectrometry-based activity assays [15] |

Performance Comparison and Implementation Challenges

Quantitative Performance Benchmarks

Table 3: Benchmarking Performance of Different ML Architectures on Biocatalysis Tasks

| Model / Architecture | Task | Dataset | Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EZSpecificity (GNN) | Substrate Specificity Prediction | 8 Halogenases, 78 Substrates | Experimental Accuracy | 91.7% | [31] |

| State-of-the-Art Model (Pre-GNN) | Substrate Specificity Prediction | Same as above | Experimental Accuracy | 58.3% | [31] |

| BioStructNet (GNN + Transfer Learning) | Catalytic Efficiency (Kcat) Prediction | EC 3 Hydrolase Dataset | R² (Coefficient of Determination) | Outperformed RF, KNN, etc. (Exact R² N/A) | [30] |

| Random Forest (Baseline) | Catalytic Efficiency (Kcat) Prediction | EC 3 Hydrolase Dataset | R² | 0.37 | [30] |

| CNN (DeepMapper) | Pattern Recognition in High-Dim Data | Synthetic high-dimensional data | Accuracy & Speed vs. Transformers | Superior speed, on-par accuracy | [27] |

Critical Challenges and Mitigation Strategies

Despite their promise, applying ML in biocatalysis faces several hurdles:

Data Scarcity and Quality: The primary bottleneck is the lack of large, consistent, high-quality experimental datasets for specific enzyme functions [15]. Solution: Employ transfer learning, where a model pre-trained on a large, general dataset (e.g., entire proteomes) is fine-tuned on a small, task-specific dataset. This has been successfully demonstrated in frameworks like BioStructNet [30]. Developing robust, high-throughput assays is also critical for data generation.

Model Generalization: Models trained on data from one protein family or under specific reaction conditions often fail to generalize to others [15]. Solution: Utilize multi-task learning and ensure training data encompasses a diverse range of protein families and conditions. Leveraging foundation models that have learned general principles of biology can also enhance generalization.

Interpretability: The "black box" nature of complex ML models can hinder scientific insight and trust. Solution: Use attribution methods like saliency maps, attention heatmaps, and SHAP values to interpret model predictions [27]. For example, the attention weights from a GNN can be mapped back to residues in the enzyme's active site, and these predictions can be cross-validated with molecular dynamics simulations to ensure they align with known catalytic mechanisms [30].

Integrated Workflow for Biocatalyst Development

A holistic ML-driven biocatalyst development pipeline integrates the strengths of all three architectures.

This workflow illustrates a cyclic process:

- Discovery: Transformers (PLMs) annotate metagenomic data or generate novel sequences, while GNNs screen for promising biocatalysts with the desired substrate specificity.

- Experimental Characterization: Selected candidates are tested experimentally using high-throughput screens.

- Optimization: CNNs analyze the resulting variant activity data to identify patterns and map fitness landscapes. This data is used to fine-tune a transformer model, which predicts the next set of optimal variants to test.

- Learning: Experimental results are fed back to update and refine all models, creating a continuous learning loop that rapidly converges on an optimized biocatalyst.

The integration of Transformer models, CNNs, and Graph-Based Networks is fundamentally advancing biocatalysis research. Transformers provide a powerful foundation for understanding sequence-function relationships, CNNs offer robust pattern recognition in complex datasets, and GNNs deliver unparalleled accuracy in modeling structural interactions. As these tools mature and address challenges related to data quality and interpretability, their role in enabling sustainable biomanufacturing and accelerating drug development will only grow. The future lies in integrated workflows that combine the strengths of these architectures within automated, iterative cycles of computational prediction and experimental validation, ultimately leading to the rapid discovery and optimization of novel biocatalysts.

The integration of machine learning (ML) with directed evolution is revolutionizing enzyme engineering, offering a powerful strategy to navigate the vast complexity of protein sequence space. Traditional directed evolution, while successful, is often limited by its reliance on extensive high-throughput screening and its tendency to explore only local regions of the fitness landscape. The core challenge in enzyme engineering is that the number of possible protein variants is astronomically large, making exhaustive experimental screening impractical. ML-guided library design addresses this fundamental issue by using computational models to predict which sequence variants are most likely to exhibit improved functions, thereby focusing experimental efforts on a much smaller, high-probability subset of mutants. This approach is particularly valuable for engineering new-to-nature enzyme functions, where fitness data is scarce and the risk of sampling non-functional variants is high. By leveraging both experimental data and evolutionary information, ML models can co-optimize for predicted fitness and sequence diversity, enabling more efficient exploration of the fitness landscape and accelerating the development of specialized biocatalysts for applications in pharmaceutical synthesis and sustainable biomanufacturing [32] [33].

Machine Learning Approaches for Predictive Library Design

Core ML Strategies

Several machine learning strategies have been developed to guide the design of focused mutant libraries in directed evolution campaigns. These approaches vary in their data requirements and underlying methodologies, offering complementary strengths for different enzyme engineering scenarios.

Supervised ML with Ridge Regression: This approach involves training models on experimentally determined sequence-function relationships to predict the fitness of unsampled variants. In one application, researchers used augmented ridge regression ML models trained on data from 1,217 enzyme variants to successfully predict amide synthetase mutants with 1.6- to 42-fold improved activity relative to the parent enzyme [34]. This method is particularly effective when sufficient experimental data is available for training.

Focused Training with Zero-Shot Predictors (ftMLDE): This strategy addresses the data scarcity problem by enriching training sets with variants pre-selected using zero-shot predictors, which estimate protein fitness without experimental data by leveraging evolutionary information, protein stability metrics, or structural insights [35]. These predictors serve as valuable priors to guide the initial exploration of sequence space before any experimental data is collected.

Ensemble Methods for Zero-Shot Prediction: Advanced frameworks like MODIFY (Machine learning-Optimized library Design with Improved Fitness and diversitY) integrate multiple unsupervised models, including protein language models and sequence density models, to create ensemble predictors for zero-shot fitness estimation [32]. This approach has demonstrated superior performance across diverse protein families, achieving robust predictions even for proteins with limited homologous sequences available.

Active Learning-Driven Directed Evolution (ALDE): This iterative approach combines machine learning with continuous experimental feedback. ML models are initially trained on a subset of variants, then used to predict promising candidates for the next round of experimentation. The newly acquired experimental data is subsequently used to refine the model, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement that efficiently navigates complex fitness landscapes [35].

The MODIFY Framework for Cold-Start Library Design

The MODIFY algorithm represents a significant advancement for engineering enzyme functions with little to no experimental fitness data available. This approach specifically addresses the cold-start challenge in enzyme engineering by leveraging pre-trained unsupervised models to make zero-shot fitness predictions [32].

MODIFY employs a Pareto optimization scheme to balance two critical objectives in library design: maximizing expected fitness and maintaining sequence diversity. The algorithm solves the optimization problem max(fitness + λ·diversity), where λ is a parameter that controls the trade-off between exploiting high-fitness regions and exploring diverse sequence space [32]. This results in libraries that sample combinatorial sequence space with variants likely to be functional while covering a broad range of sequences to access multiple fitness peaks.

When benchmarked on 87 deep mutational scanning datasets, MODIFY demonstrated robust and accurate zero-shot fitness prediction, outperforming state-of-the-art individual unsupervised methods including ESM-1v, ESM-2, EVmutation, and EVE [32]. This performance generalizes well to higher-order mutants, making it particularly valuable for designing combinatorial libraries targeting multiple residue positions simultaneously.

Table 1: Key Machine Learning Frameworks for Library Design

| ML Framework | Primary Approach | Data Requirements | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supervised Ridge Regression | Regression models trained on experimental sequence-function data | Large experimental datasets | High accuracy within sampled regions; Effective for interpolation |

| ftMLDE | Focused training using zero-shot predictors | Limited initial data | Reduces screening burden; Leverages evolutionary information |

| MODIFY | Ensemble zero-shot prediction with Pareto optimization | No experimental fitness data required | Co-optimizes fitness and diversity; Effective for cold-start problems |

| Active Learning (ALDE) | Iterative model refinement with experimental feedback | Initial training set with ongoing data collection | Continuously improves predictions; Efficiently navigates rugged landscapes |

Experimental Protocols for ML-Guided Directed Evolution

Integrated Workflow for Cell-Free ML-Guided Enzyme Engineering

The following protocol outlines an integrated ML-guided approach for enzyme engineering using cell-free expression systems, adapted from recently published methodologies [34]. This workflow is particularly effective for mapping fitness landscapes and optimizing enzymes for multiple distinct chemical reactions.

Step 1: Initial Substrate Scope Evaluation

- Evaluate the substrate promiscuity of the wild-type enzyme against an extensive array of potential substrates, including primary, secondary, alkyl, aromatic, and complex pharmacophore substrates.

- Identify specific challenging chemical transformations for optimization campaigns. For example, in the case of amide synthetase engineering, evaluate substrate preference for 1,217 enzyme variants across 10,953 unique reactions [34].

Step 2: Hot Spot Identification via Site-Saturation Mutagenesis

- Select residues for mutagenesis based on structural information (within 10Å of active site or substrate tunnels).

- Generate site-saturated, sequence-defined protein libraries using cell-free DNA assembly and cell-free gene expression (CFE) with the following sub-steps [34]:

- Use DNA primers containing nucleotide mismatches to introduce desired mutations via PCR.

- Digest parent plasmid with DpnI.

- Perform intramolecular Gibson assembly to form mutated plasmids.

- Amplify linear DNA expression templates (LETs) via a second PCR.

- Express mutated proteins through CFE systems.

Step 3: Data Generation for ML Training

- Perform functional assays under relevant reaction conditions (e.g., high substrate concentration, low enzyme loading).

- Collect sequence-function data for all screened variants, ensuring accurate genotype-phenotype linkage.

- For the amide synthetase case study, this involved evaluating 1,216 single-order mutants (64 residues × 19 amino acids) for each target molecule [34].

Step 4: Machine Learning Model Training

- Train supervised ML models (e.g., augmented ridge regression) on the collected sequence-function data.

- Incorporate evolutionary zero-shot fitness predictors to enhance model performance, particularly for regions with sparse experimental data.

- Use the trained models to extrapolate higher-order mutants with predicted increased activity [34].

Step 5: Experimental Validation and Iteration

- Synthesize and test ML-predicted enzyme variants.

- Compare experimental results with predictions to validate model accuracy.

- Iterate the process by incorporating new data to refine the model and identify further improvements.

MODIFY Protocol for Cold-Start Library Design

For engineering new-to-nature enzyme functions where prior fitness data is unavailable, the MODIFY framework provides a robust protocol for initial library design [32]:

Step 1: Residue Selection for Engineering

- Identify target residues based on structural information, evolutionary conservation, or previous engineering studies.

- For cytochrome P450 engineering, focus on active site residues and regions influencing substrate access and cofactor binding.

Step 2: Zero-Shot Fitness Prediction

- Generate an ensemble fitness prediction using protein language models (ESM-1v, ESM-2) and sequence density models (EVmutation, EVE).

- Calculate fitness scores for all possible combinatorial variants within the targeted residue set.

Step 3: Pareto Optimization for Library Design

- Implement the MODIFY algorithm to identify variants that balance high predicted fitness with sequence diversity.

- Solve the optimization problem: max(fitness + λ·diversity) to trace the Pareto frontier.