Machine Learning to Navigate Protein Fitness Landscapes: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the navigation of protein fitness landscapes to accelerate protein engineering.

Machine Learning to Navigate Protein Fitness Landscapes: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of how machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing the navigation of protein fitness landscapes to accelerate protein engineering. It covers the foundational concepts of sequence-function landscapes and the challenge of epistasis, explores key ML methodologies from supervised learning to generative models, addresses critical troubleshooting for rugged landscapes and data scarcity, and offers a comparative analysis of model validation and performance. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current best practices and emerging trends to empower the efficient design of novel proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Understanding Protein Fitness Landscapes and the Role of Epistasis

Defining the Protein Sequence-Function Fitness Landscape

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers applying machine learning to navigate and characterize protein fitness landscapes.

### Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How complex are protein sequence-function relationships? Are high-order epistatic interactions common? Recent evidence suggests that sequence-function relationships are often simpler than previously thought. A 2024 study using a reference-free analysis method found that for 20 experimental datasets, context-independent amino acid effects and pairwise interactions explained a median of 96% of the phenotypic variance, and over 92% in every case. Only a tiny fraction of genotypes were strongly affected by higher-order epistasis. The genetic architecture was also found to be sparse, meaning a very small fraction of possible amino acids and their interactions account for the majority of the functional output [1]. However, the importance of higher-order epistasis can vary and may be critical for generalizing predictions from local data to distant regions of sequence space [2].

Q2: My ML model performs well on validation data but generates non-functional protein designs. What is happening? This is a classic sign of failed extrapolation. Model architecture heavily influences design performance. A 2024 study experimentally testing thousands of designs found that simpler models like Fully Connected Networks (FCNs) excelled at designing high-fitness proteins in local sequence space. In contrast, more sophisticated Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) could venture deep into sequence space to design proteins that were folded but non-functional, indicating they might capture general biophysical rules for folding but not specific function. Implementing a simple ensemble of CNNs was shown to make protein engineering more robust by aggregating predictions and reducing model-specific idiosyncrasies [3].

Q3: What machine learning strategies can I use when I have very limited functional data for my protein of interest? Two primary strategies address small data regimes:

- Leverage unsupervised learning representations: Using low-dimensional protein sequence representations learned from vast, unlabeled protein databases (e.g., via VAEs, LSTMs, or transformers) as input for your supervised model. For instance, the eUniRep representation, trained on 24 million sequences, enabled successful design of improved GFP variants with fewer than 100 labeled examples [4].

- Employ active learning cycles: Instead of a one-shot design, use an iterative design-test-learn cycle with methods like Bayesian Optimization. This allows you to strategically select which sequences to test to refine the model with maximal efficiency. One application engineered improved enzymes with less than 100 experimental measurements over ten cycles [4].

Q4: What is the difference between "global" (nonspecific) and "specific" epistasis, and why does it matter for modeling? Understanding this distinction is crucial for building accurate models.

- Specific Epistasis: Refers to interactions between specific amino acids at specific positions in the sequence (e.g., a pairwise interaction between residue 5 and residue 20).

- Global (Nonspecific) Epistasis: Refers to a nonlinear transformation that affects all mutations universally, often due to the limited dynamic range of the experimental assay. For example, a saturation effect where fitness scores cannot exceed a certain upper limit [1] [2]. Failing to account for global epistasis can make the genetic architecture appear unnecessarily complex. A model that jointly infers specific interactions and a global nonlinearity can provide a much simpler and more accurate explanation of the data [1].

### Troubleshooting Experimental Workflows

Problem: ML-guided directed evolution gets stuck in a local fitness peak. Solution: Integrate diversification strategies and model-based exploration.

- Recommended Protocol (ML-Assisted Directed Evolution):

- Start with a combinatorial site-saturation mutagenesis library.

- Screen a small subset of variants to generate initial sequence-function data.

- Train a supervised ML model (e.g., CNN, FCN) on this data.

- Use the model to predict the fitness of all unscreened variants in the combinatorial space.

- Fix the top-performing mutations to create a new parent for the next round.

- To avoid local optima, select multiple high-fitness variants from distinct clusters in sequence space for the next round, rather than just the single top predictor [4]. Using an ensemble model can also help identify more robustly beneficial mutations [3].

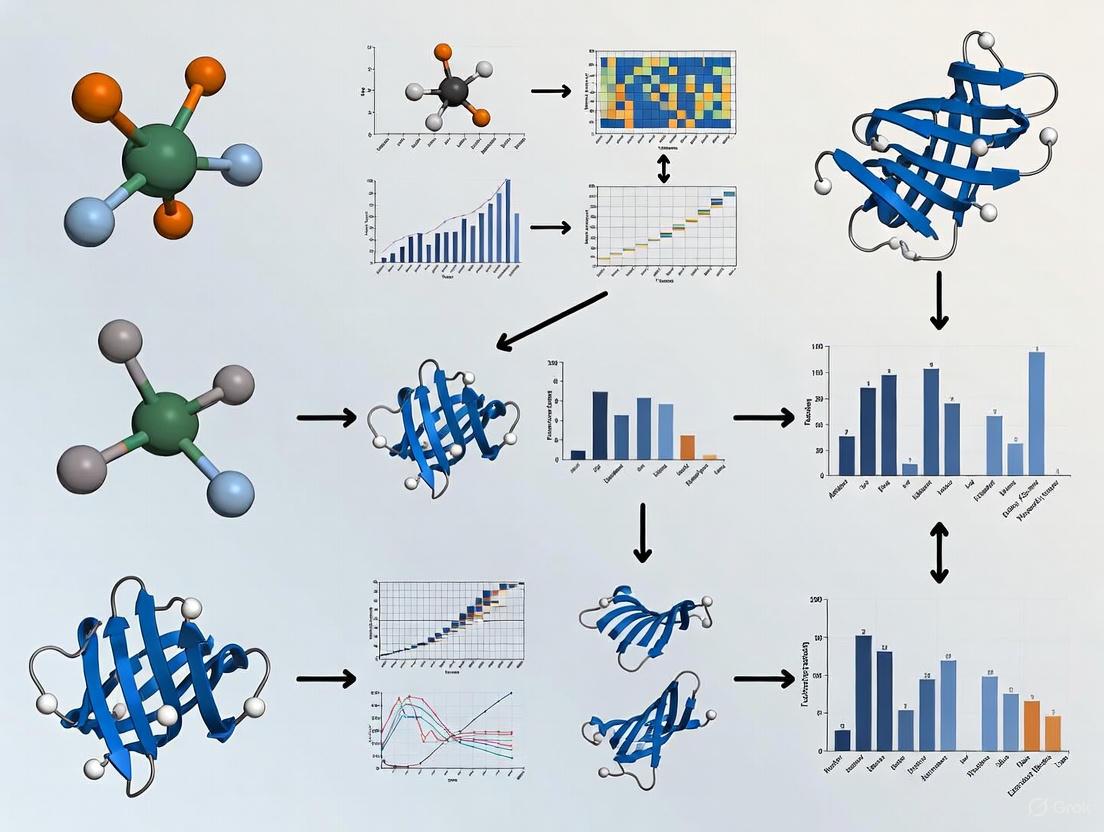

The workflow below illustrates this iterative cycle:

Problem: Poor model generalization when predicting the effect of multiple mutations. Solution: Carefully select your model architecture based on the extrapolation task. The table below summarizes the experimental performance of different architectures from a systematic study on the GB1 protein [3].

| Model Architecture | Key Inductive Bias | Best Use-Case for Design | Performance Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Model (LR) | Assumes additive effects; no epistasis. | Local optimization where epistasis is minimal. | Notably lower performance due to inability to model epistasis [3]. |

| Fully Connected Network (FCN) | Can capture nonlinearity and epistasis. | Local extrapolation for designing high-fitness proteins [3]. | Infers a smoother landscape with a prominent peak [3]. |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Parameter sharing across sequence; captures local patterns. | Designing folded proteins; requires ensemble for robust functional design [3]. | Can design folded but non-functional proteins in distant sequence space [3]. |

| Graph CNN (GCN) | Incorporates protein structural context. | Identifying high-fitness variants from a ranked list [3]. | Showed high recall for identifying top 4-mutants in a combinatorial library [3]. |

| Transformer-based | Models long-range and higher-order interactions. | Scenarios where higher-order epistasis is critical [2]. | Can isolate interactions involving 3+ positions; importance varies by protein [2]. |

### The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational and experimental resources for mapping fitness landscapes.

| Resource / Solution | Function in Fitness Landscape Research |

|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) | High-throughput experimental method to assess the functional impact of thousands to millions of protein variants in parallel [2] [5]. |

| T7 Phage Display | A display technology that can be coupled with high-throughput sequencing to quantitatively track the binding fitness of hundreds of thousands of protein variants [5]. |

| Reference-Free Analysis (RFA) | A computational method that dissects genetic architecture relative to the global average of all variants, providing a robust, simple, and interpretable model of sequence-function relationships [1]. |

| eUniRep / Learned Representations | Low-dimensional vector representations of protein sequences learned from unlabeled data, enabling supervised learning with very limited functional data [4]. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) | An active learning framework for iteratively proposing new protein sequences to test, balancing exploration (model uncertainty) and exploitation (predicted fitness) [4]. |

| Epistatic Transformer | A specialized neural network designed to explicitly model and quantify the contribution of higher-order epistatic interactions (e.g., 3-way, 4-way) to protein function [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why does my machine learning model perform poorly when predicting the effect of new, multiple mutations? This is a classic symptom of model extrapolation failure. When a model trained on single and double mutants is used to predict variants with three or more mutations, it operates outside its training domain. Performance can drop sharply in this extrapolated regime, as the model may not have learned the underlying higher-order epistatic interactions from the limited training data [3].

Q2: My experimental fitness measurements are noisy. How does this impact the study of landscape ruggedness? Fitness estimation error directly and significantly biases the inferred ruggedness of your landscape upward. Noise can create false local peaks and make epistasis appear more prevalent than it is. Without correction, all standard ruggedness measures (e.g., number of peaks, fraction of sign epistasis) will be overestimated. It is advised to use at least three biological replicates to enable unbiased inference of landscape ruggedness [6].

Q3: What is the single most important landscape characteristic that determines ML prediction accuracy? Research indicates that landscape ruggedness, which is primarily driven by epistasis, is a key determinant of model performance. Ruggedness impacts a model's ability to interpolate within the training domain and, most critically, to extrapolate beyond it [7].

Q4: Are some ML model architectures better at handling epistasis than others? Yes, architectural inductive biases prime models to learn different aspects of the fitness landscape. For instance:

- Linear Models: Assume additivity and cannot capture epistasis, leading to poor performance on rugged landscapes [3].

- Fully Connected Networks (FCN): Can capture nonlinearity and epistasis, often excelling at local extrapolation to design high-fitness variants near the training data [3].

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN): Can capture long-range interactions and have been shown to venture deep into sequence space, sometimes designing folded but non-functional proteins, suggesting they learn fundamental biophysical rules [3].

Q5: What is "fluid" epistasis? Fluid epistasis describes a phenomenon where the type of interaction (e.g., positive, negative, or sign epistasis) between a pair of mutations changes drastically depending on the genetic background. This is caused by higher-order epistatic interactions and contributes to the challenge of predicting mutational effects [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Model Performance on Combinatorial Mutants

Symptoms:

- High prediction accuracy on single/double mutants (interpolation) but low accuracy on triple+ mutants (extrapolation).

- The model fails to identify high-fitness combinations of beneficial mutations.

Solutions:

- Architecture Selection: Use model architectures capable of capturing epistasis, such as Fully Connected Networks (FCN), Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN), or Graph Convolutional Networks (GCN). Avoid purely additive models for highly epistatic landscapes [9] [3].

- Employ Ensembles: Implement a neural network ensemble, which averages predictions from multiple models trained with different random initializations. This has been shown to make protein engineering more robust and mitigate the risk of poor extrapolation from any single model [3].

- Active Learning: Instead of a single round of training and prediction, use an Active Learning-guided Directed Evolution (ALDE) strategy. Iteratively train the model with new experimental data from each round, allowing the model to gradually learn the complex landscape structure [9].

- Focused Training (ftMLDE): Use zero-shot predictors (e.g., based on evolutionary data or protein stability) to create an enriched, focused training set. This biases the training data toward more functional regions of sequence space, providing a better starting point for the model [9].

Problem: Overestimation of Landscape Ruggedness

Symptoms:

- An unexpectedly high number of local fitness peaks are inferred from the data.

- Evolutionary pathways appear heavily constrained or blocked.

Solutions:

- Increase Replication: Incorporate a minimum of three biological replicates for fitness measurements [6].

- Error-Aware Analysis: Use a statistical framework that incorporates fitness estimation error and replicate data to correct the bias in ruggedness measures. The table below summarizes common ruggedness measures and the impact of error on them [6].

Table 1: Common Measures of Fitness Landscape Ruggedness and Impact of Estimation Error

| Measure | Description | Effect of Fitness Estimation Error |

|---|---|---|

| Number of Maxima (Nₘₐₓ) | Count of fitness peaks (genotypes with no fitter neighbors). | Strong overestimation |

| Fraction of Reciprocal Sign Epistasis (Fᵣₛₑ) | Proportion of mutation pairs that show strong, constraining epistasis. | Strong overestimation |

| Roughness/Slope Ratio (r/s) | Standard deviation of fitness residuals after additive fit, divided by mean selection coefficient. | Overestimation |

| Fraction of Blocked Pathways (Fᵦₚ) | Proportion of evolutionary paths where any step decreases fitness. | Overestimation |

Problem: Navigating a Rugged Landscape with Many Local Peaks

Symptoms:

- Directed evolution experiments get stuck at suboptimal fitness peaks.

- Different evolutionary replicates converge to different final genotypes.

Solutions:

- ML-guided Design: Replace greedy hill-climbing with model-guided search. Use ML models to predict high-fitness sequences across the entire landscape, enabling jumps across fitness valleys that would be inaccessible to traditional methods [9].

- Broad Sampling: For model training, ensure the initial library samples a diverse set of genotypes rather than just single mutants. This gives the model a broader view of the landscape and its epistatic structure from the outset [7] [3].

- Landscape Topography Analysis: Before embarking on large-scale engineering, characterize the landscape's topography. Landscapes that are rugged but have broad basins of attraction around high peaks are more "navigable" and better suited for ML-guided search [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Evaluating ML Model Extrapolation Capacity

Purpose: To systematically test a model's ability to make accurate predictions far from its training data, a critical requirement for protein design.

Procedure:

- Data Partitioning: Start with a deep mutational scan dataset (e.g., all single and double mutants within a protein domain). Use all single and double mutants as the training set.

- Create Extrapolation Test Sets: Construct separate test sets containing all combinatorial triple mutants, quadruple mutants, etc., from the same set of positions.

- Model Training: Train your ML model(s) exclusively on the single and double mutant training set.

- Hierarchical Validation: Evaluate model performance (e.g., using Spearman's correlation or recall of top variants) separately on the single/double test set (interpolation) and on the triple+, quadruple+ test sets (extrapolation).

- Analysis: Compare performance degradation as a function of mutational distance from the wild-type sequence. This reveals the effective "range" of the model [3].

Protocol 2: Bias-Corrected Inference of Landscape Ruggedness

Purpose: To accurately measure the ruggedness of a fitness landscape from experimental data while accounting for and correcting the bias introduced by fitness estimation error.

Procedure:

- Data Collection with Replicates: Measure the fitness of all genotypes in the landscape of interest with a minimum of three biological replicates.

- Calculate True Fitness: For each genotype, compute the mean fitness across replicates.

- Generate Noisy Landscapes: Create a large number (e.g., 1000) of "observed" landscapes by resampling fitness values for each genotype from a normal distribution defined by the mean and standard deviation of its replicates.

- Measure Ruggedness: Calculate your chosen ruggedness measure (e.g., Nₘₐₓ, r/s) for both the "true" landscape (using mean fitness) and for each of the noisy "observed" landscapes.

- Estimate and Correct Bias: Calculate the mean ruggedness value across all the noisy landscapes. The difference between this mean and the "true" value estimates the bias. Use this to correct the initial measurement [6].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Combinatorial Landscape Datasets (e.g., GB1, ParD-ParE, DHFR) | Experimental data mapping sequence to fitness for many variants; essential for training and benchmarking ML models [9]. |

| Zero-Shot (ZS) Predictors | Computational models (e.g., based on evolutionary coupling, stability, or structure) that predict fitness without experimental data; used to create enriched training sets for ftMLDE [9]. |

| Model Ensembles (e.g., EnsM, EnsC) | A set of neural networks with different initializations; using their median (EnsM) or lower percentile (EnsC) prediction makes design more robust than relying on a single model [3]. |

| Fitness Landscape Analysis Software (e.g., MAGELLAN) | A graphical tool that implements various measures of epistasis and ruggedness, including the correlation of fitness effects (γ), for analyzing small fitness landscapes [10]. |

| High-Throughput Phenotyping Assay | An experimental method (e.g., yeast display, mRNA display, growth selection) to reliably measure the fitness/function of thousands of protein variants in parallel [3] [8]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Model-Guided Protein Design Workflow

How Epistasis Influences ML-Guided Protein Design

Why Traditional Directed Evolution Reaches Local Optima

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a "local optimum" in the context of my protein engineering experiment?

- A: A local optimum is a protein variant that is the best in its immediate "neighborhood" of sequences (e.g., all sequences one or two mutations away), but is not the best possible variant in the entire sequence space. It's like being on the top of a small hill in a mountain range; you can't go higher by taking a single small step, even though a much taller peak exists elsewhere. Traditional directed evolution often gets stuck on these small hills because it only tests variants that are very similar to the current best one [11] [12].

Q2: The main screening round identified a great hit. Why does recombining its mutations with other good hits sometimes fail to improve the protein further?

- A: This failure is often due to epistasis—a non-additive, synergistic interaction between mutations [13] [11]. A mutation that is beneficial in one genetic background (e.g., your parent sequence) may be neutral or even detrimental when combined with other beneficial mutations. If mutations interact negatively, recombining them can lead to a less stable or less active protein, causing your experiment to stall at a local optimum [11]. As highlighted in one study, recombining the best single-site mutants sometimes yields variants with poorer performance than the parent [11].

Q3: My directed evolution campaign has plateaued after several rounds. Have I found the best possible variant?

- A: Not necessarily. You have likely exhausted the supply of beneficial mutations accessible via single steps from your current sequence. The global optimum may require a combination of mutations that individually appear neutral or slightly deleterious but are highly beneficial when present together. These combinations are invisible to traditional "greedy" directed evolution, which only accumulates obviously beneficial mutations [14] [12].

Q4: Are there specific protein properties that make an experiment more prone to getting stuck in local optima?

- A: Yes. Experiments are more prone to getting stuck when optimizing complex functions involving trade-offs (e.g., activity vs. stability) or when engineering entirely new-to-nature functions. These scenarios often create "rugged" fitness landscapes with many peaks and valleys, making it easy for a traditional search to get trapped [11] [12].

Troubleshooting Guide: Overcoming Local Optima

| Symptom | Likely Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fitness plateaus after 2-3 rounds of mutagenesis and screening. | Exhaustion of accessible beneficial single mutations; rugged fitness landscape. | Switch to a machine learning-assisted approach like MLDE or Active Learning (ALDE) to model epistasis and propose high-fitness combinations [4] [11]. |

| Recombined "best hit" mutations result in inactive or poorly performing variants. | Negative epistasis between mutations. | Use neutral drifts to increase protein stability and mutational robustness before selecting for function, creating a more permissive landscape [13] [12]. |

| Need to optimize multiple properties simultaneously (e.g., yield and selectivity). | Conflicting evolutionary paths; multi-objective optimization creates a complex landscape. | Implement Bayesian Optimization (BO) with an acquisition function that balances the multiple objectives [4] [15]. |

Quantitative Comparison of Directed Evolution Strategies

The following table summarizes the key characteristics of different protein engineering strategies, highlighting how modern methods address the limitations of traditional directed evolution.

| Method | Key Principle | Data & Screening Requirements | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Directed Evolution | Iterative "greedy" hill-climbing via random mutagenesis and screening [12]. | Requires high-throughput screening for each round. | Conceptually simple; requires no model. | Prone to local optima; ignores epistasis; screening-intensive [11]. |

| Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (MLDE) | Train a model on initial screening data to predict fitness and propose best recombinations [4]. | Requires a medium-throughput initial dataset (e.g., from a combinatorial library). | Accounts for some epistasis; more efficient than random recombination [4]. | Limited to the defined combinatorial space; performance depends on initial data quality. |

| Active Learning (e.g., ALDE) | Iterative Design-Test-Learn cycle using a model that quantifies uncertainty to guide the next experiments [11]. | Lower screening burden per round; total screening is drastically reduced. | Highly efficient; actively explores rugged landscapes; excellent at handling epistasis [11]. | Requires iterative wet-lab/computational cycles; more complex setup. |

Experimental Protocol: Implementing an Active Learning Workflow (ALDE)

The ALDE protocol is designed to efficiently navigate epistatic landscapes and escape local optima [11].

Define the Combinatorial Space:

- Select

kresidues hypothesized to influence function (e.g., active site residues). This defines a search space of 20k possible sequences [11].

- Select

Generate and Screen an Initial Library:

- Synthesize a library where the

kresidues are randomized, for example, using NNK codons. - Screen a random subset (e.g., hundreds) of variants from this library to collect initial sequence-fitness data [11].

- Synthesize a library where the

Computational Model Training and Proposal:

- Train a machine learning model (e.g., a neural network with uncertainty quantification) on the collected sequence-fitness data.

- Use the trained model to predict the fitness of all sequences in the defined 20k space.

- Apply an acquisition function (e.g., favoring sequences with high predicted fitness and high uncertainty) to select the next batch of variants to test experimentally [11].

Iterative Refinement:

- Synthesize and screen the top

Nvariants proposed by the model. - Add the new data to the training set and repeat steps 3 and 4 until a fitness goal is reached or performance plateaus [11].

- Synthesize and screen the top

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| NNK Degenerate Codon | A primer encoding strategy that randomizes a single amino acid position to all 20 possibilities (encodes 32 possible codons). Used in site-saturation mutagenesis to explore a specific residue [11]. |

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) Kit | A standard method for introducing random mutations throughout a gene. It mimics imperfect DNA replication to create diversity in early rounds of directed evolution [13]. |

| Combinatorial Library Synthesis | A service (or in-house method) to simultaneously randomize multiple predetermined amino acid positions. This is crucial for generating the initial dataset for MLDE or ALDE [14]. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay | An assay (e.g., based on fluorescence, absorbance, or growth coupling) that allows you to rapidly test the function of thousands of protein variants. The quality and throughput of this assay are critical for generating reliable data [12]. |

| Gaussian Process Model / Bayesian Optimization | A class of machine learning models that not only predict fitness but also estimate the uncertainty of their predictions. This is particularly valuable for balancing exploration and exploitation in active learning [4] [11]. |

Technical Support Center

This support center provides troubleshooting guides and frequently asked questions (FAQs) for researchers employing machine learning (ML) to navigate protein fitness landscapes. The content is designed to help you identify and resolve common issues in your experimental workflows.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Poor Model Generalization and Extrapolation

Problem: Your trained model performs well on validation data but fails to guide the design of novel, high-fitness protein variants, especially those with many mutations distant from the training set.

Explanation: This is a classic problem of model extrapolation. The model has learned the local fitness landscape around your training sequences but cannot accurately predict the fitness of sequences in unexplored regions of the vast sequence space [3].

Solutions:

- Implement Model Ensembles: Instead of relying on a single model, use an ensemble of models (e.g., 100 convolutional neural networks with different random initializations). Using the median (EnsM) or a conservative percentile (EnsC) of the ensemble's predictions can lead to more robust and reliable designs, making the engineering process more robust [3].

- Choose an Appropriate Architecture: Model architecture significantly influences extrapolation capability. Evidence from GB1 binding experiments shows that simpler models like Fully Connected Networks (FCNs) can excel at designing improved variants in local sequence space, while Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) may venture deeper but sometimes produce folded, non-functional proteins. Consider your goal—local optimization versus distant exploration [3].

- Utilize Informative Sequence Representations: Reduce data requirements and improve model generalization by using low-dimensional protein representations. These can be learned from large, unlabeled protein sequence databases (e.g., via UniRep) and capture key evolutionary or biophysical features, helping to guide predictions away from non-functional sequence space [4].

Table 1: Model Performance in Extrapolation Tasks

| Model Architecture | Strength in Local Search | Strength in Distant Exploration | Note on Design Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear Model (LR) | Low | Low | Cannot capture epistasis [3] |

| Fully Connected Network (FCN) | High | Medium | Excels at designing high-fitness variants near training data [3] |

| Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) | Medium | High | Can design folded but non-functional proteins in distant sequence space [3] |

| Graph CNN (GCN) | Medium | High | High recall for identifying top fitness variants in combinatorial spaces [3] |

| CNN Ensemble (EnsM) | High | High | Most robust approach for designing high-performing variants [3] |

Guide 2: Managing Small or Sparse Sequence-Function Datasets

Problem: You have limited functional data (tens to hundreds of variants) for a protein of interest, which is insufficient for training a powerful supervised ML model.

Explanation: Many proteins lack high-throughput functional assays, resulting in small labeled datasets. Deep learning models typically require large amounts of data to avoid overfitting and to learn complex sequence-function relationships [4].

Solutions:

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Use pre-trained models that have learned general protein sequence representations from massive datasets (e.g., 24 million sequences for UniRep). These representations can then be fine-tuned for your specific protein using your small labeled dataset, enabling effective learning with fewer than 100 examples [4].

- Incorporate Biophysical and Evolutionary Features: Instead of using only raw amino acid sequences, engineer feature vectors that include information like total charge, site conservation, and solvent accessibility. These features can distill essential aspects of protein function and enable learning with less data [4].

- Adopt Active Learning Cycles: Move from a one-shot training approach to an iterative "design-test-learn" cycle using methods like Bayesian Optimization (BO). BO proposes sequences that are both informative for the model and predicted to be high-fitness, maximizing the value of each experimental measurement. This approach has successfully engineered enzymes with less than 100 experimental measurements [4].

Guide 3: Software and Dependency Conflicts

Problem: Errors occur when running automated ML pipelines or loading pre-trained models, often manifesting as ModuleNotFoundError, ImportError, or AttributeError.

Explanation: These issues are frequently caused by dependency version conflicts. Automated ML tools and pre-trained models often rely on specific versions of packages like pandas and scikit-learn. Using an incompatible version can break the code [16].

Solutions:

- Create a Dedicated Conda Environment: Isolate your project dependencies to prevent conflicts with other projects. You can use scripts like

automl_setupto facilitate this process [16]. - Pin Package Versions: Determine the version of your AutoML SDK and install the corresponding compatible packages [16]:

- For AutoML SDK > 1.13.0, use:

- For AutoML SDK <= 1.12.0, use:

- Reinstall for Major Updates: When upgrading from an old SDK version (pre-1.0.76) to a newer one, uninstall the previous packages completely before installing the new ones [16]:

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the difference between in silico optimization and active learning for protein engineering?

A1: In silico optimization is a one-step process where a model is trained on an existing dataset and then used to propose improved protein designs, for example, by using hill climbing or genetic algorithms to find sequences with the highest predicted fitness [4]. In contrast, active learning (e.g., Bayesian Optimization) or Machine Learning-assisted Directed Evolution (MLDE) implements an iterative "design-test-learn" cycle. A model is used to propose new variants, which are then experimentally tested, and the new data is used to refine the model for the next round. This cycle drastically reduces the total experimental screening burden compared to traditional directed evolution or one-shot in silico design [4].

Q2: My model predictions are becoming extreme and unrealistic when exploring distant sequences. Is this normal?

A2: Yes, this is a recognized challenge. Neural network models have millions of parameters that are not fully constrained by the training data. When predicting far from the training regime, these unconstrained parameters can lead to significant divergence and extreme, often invalid, fitness predictions [3]. This phenomenon underscores the importance of using ensembles and experimental validation instead of blindly trusting single-model predictions in distant sequence space.

Q3: How can I decide between using a simple linear model versus a more complex deep neural network for my project?

A3: The choice involves a trade-off. Linear models assume additive effects of mutations and are unable to capture epistasis (non-linear interactions between mutations). They are simpler and require less data but can have lower predictive performance, especially for complex landscapes [3]. Deep neural networks (CNNs, FCNs, GCNs) can learn complex, non-linear relationships and epistasis, leading to better performance, but they require more data and computational resources. The best choice depends on the known complexity of your protein's fitness landscape and the size of your dataset [4] [3].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates a robust, iterative workflow for machine learning-guided protein engineering, integrating the troubleshooting solutions outlined above.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ML-Guided Protein Engineering

| Reagent / Material | Function in Workflow |

|---|---|

| High-Throughput Assay System (e.g., yeast display, mRNA display) | Essential for generating the large-scale sequence-function data required for training and validating ML models. Measures protein properties like binding affinity or enzymatic activity for thousands of variants [4] [3]. |

| Gene Synthesis Library | Allows for the physical construction of the protein sequences proposed by the ML model, enabling experimental testing [3]. |

| Model Protein System (e.g., GB1, GFP, Acyl-ACP Reductase) | A well-characterized protein domain used as a testbed for developing and benchmarking ML-guided design methods. GB1, for instance, has a comprehensively mapped fitness landscape [4] [3]. |

| Pre-trained Protein Language Model (e.g., UniRep, ESM) | Provides a low-dimensional, informative representation of protein sequences that can be used as input to supervised models, drastically reducing the amount of labeled data needed for effective learning [4]. |

| ML Framework with Ensemble & BO Tools (e.g., TensorFlow, PyTorch, Ax) | Software libraries that provide the algorithms for building model ensembles, performing Bayesian optimization, and executing other active learning strategies critical for robust and data-efficient protein design [4] [3]. |

Key Machine Learning Strategies for Protein Engineering

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "modeling sequence-function relationships" mean in the context of protein engineering? This refers to the use of supervised machine learning to learn the mapping between a protein's amino acid sequence (the input) and a specific functional property, such as catalytic activity or binding affinity (the output). The resulting model can predict the function of unseen sequences, guiding the search for improved proteins. [4]

Q2: My model achieves high accuracy on the training data but fails to predict the function of new, unseen sequences. What is the cause? This is a classic sign of overfitting. Your model has likely learned noise and specific patterns from your limited training data rather than the underlying generalizable sequence-function rules. This is especially common with complex models like deep neural networks trained on small datasets. [17]

Q3: How can I prevent overfitting when my experimental dataset is small (e.g., only 100s of sequences)? Several strategies can help:

- Use Informative Sequence Representations: Instead of using raw amino acid sequences, leverage low-dimensional representations learned from millions of unlabeled sequences by unsupervised models (e.g., LSTMs, VAEs, Transformers). These representations, such as those from UniRep, distill biophysically relevant features and make learning more data-efficient. [4]

- Apply Regularization: Use techniques like dropout or L1/L2 regularization during model training to prevent the network from becoming overly complex and relying on spurious correlations. [17]

- Simplify the Model: Start with a simpler model (like a linear model) as a baseline. A well-tuned simpler model can often outperform an overly complex one on small datasets. [17]

Q4: What is the difference between MLDE and active learning for directed evolution?

- Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (MLDE) typically uses a model trained on a single, initial dataset (e.g., from a combinatorial library) to predict and select the top-performing sequences for a single round of testing. [4] [9]

- Active Learning (or Active Learning-Directed Evolution, ALDE) employs an iterative "design-test-learn" cycle. A model is trained and then used to propose a small, informative batch of sequences to test experimentally. The new data is used to refine the model, and the process repeats, often requiring far fewer total measurements than traditional methods. [4] [9]

Q5: What is epistasis and why does it challenge protein engineering? Epistasis occurs when the effect of one mutation depends on the presence of other mutations in the sequence. This creates a "rugged" fitness landscape with multiple peaks and valleys, making it difficult for traditional directed evolution to combine beneficial mutations, as they may not be beneficial in all genetic backgrounds. [9]

Q6: How do supervised learning models handle epistatic interactions? Different model architectures have different capacities to capture epistasis:

- Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) can learn local, non-linear interactions between nearby residues in the sequence. [4]

- Recurrent Neural Networks (RNNs), like LSTMs, process sequences step-by-step and can capture long-range dependencies. [4]

- Transformers use attention mechanisms to explicitly learn the specific long-range interactions between any residues in the sequence, making them particularly powerful for modeling complex epistasis. [4] [18]

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Possible Causes | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Poor Model Generalization | • Insufficient or non-representative training data.• Overfitting due to high model complexity.• Ignoring key feature engineering or domain knowledge. [17] | • Use low-dimensional protein representations (e.g., from UniRep). [4]• Apply regularization (dropout, L1/L2) and cross-validation. [17]• Incorporate biophysical features (charge, conservation). [4] |

| Inability to Find High-Fitness Sequences | • Model cannot extrapolate beyond training data distribution.• Rugged, epistatic fitness landscape. [9] | • Switch to an active learning framework for iterative refinement. [4]• Use models that capture epistasis (Transformers, CNNs). [4] [18]• Employ landscape-aware search algorithms (e.g., μSearch). [18] |

| High Variance in Model Performance | • Small dataset size.• Improper model evaluation or data leakage. [17] | • Use k-fold cross-validation to ensure performance consistency. [17]• Ensure no test set information is used in training/feature selection. [17] |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Standard MLDE Workflow

This protocol outlines the steps for a standard Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution campaign. [9]

- Library Design & Data Generation: Create a combinatorial site-saturation mutagenesis library targeting key residues.

- High-Throughput Screening: Screen a subset of the library to generate a dataset of sequences and their corresponding fitness measurements.

- Model Training: Train one or more supervised learning models (e.g., CNN, RNN, Transformer) on the sequence-function data.

- In Silico Prediction: Use the trained model to predict the fitness of all possible variants in the combinatorial space.

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize and experimentally characterize the top in silico predicted sequences.

The following diagram illustrates this workflow and the key decision points:

Protocol 2: The μProtein Framework for Advanced Optimization

This protocol describes a more advanced framework that combines a deep learning model with reinforcement learning for efficient landscape navigation. [18]

- Base Data Collection: Generate a deep mutational scanning dataset, ideally containing single-mutation effects.

- Train μFormer Model: Train a Transformer-based model on the mutational data. This model learns to predict fitness and, crucially, captures epistatic interactions between mutations.

- Setup μSearch: Use the trained μFormer model as an "oracle" for the μSearch reinforcement learning algorithm.

- Multi-Step Search: μSearch performs a multi-step, guided exploration of the sequence space, proposing multi-point mutants that are likely to have high fitness.

- Wet-Lab Validation: Test the proposed high-gain-of-function mutants in the laboratory.

Performance of MLDE Strategies Across Diverse Landscapes

A comprehensive study evaluated different ML-assisted strategies across 16 combinatorial protein landscapes. The table below summarizes key findings on how these strategies compare to traditional Directed Evolution (DE). [9]

Table 1: Comparative performance of machine learning-assisted strategies against traditional directed evolution. [9]

| Strategy | Description | Advantage over DE | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| MLDE | Single-round model training and prediction on a random sample. | Matches or exceeds DE performance; more pronounced advantage on rugged landscapes with many local optima. [9] | Standard landscapes where initial library coverage is good. |

| focused training MLDE (ftMLDE) | Model training on a library pre-filtered using zero-shot (ZS) predictors (e.g., based on evolution or structure). | Further improves performance by enriching training sets with more informative, higher-fitness variants. [9] | Landscapes with fewer active variants; leveraging prior knowledge. |

| Active Learning DE (ALDE) | Iterative rounds of model-based proposal and experimental testing. | Drastically reduces total screening burden by guiding the search with sequential model refinement. [4] [9] | Settings with low throughput assays and complex, epistatic landscapes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential computational tools and resources for modeling protein sequence-function relationships.

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Relevance to Research |

|---|---|---|

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data | High-throughput experimental method to measure the functional effects of thousands of protein variants. [18] | Provides the essential labeled dataset (sequences & fitness) for training supervised models. |

| Zero-Shot (ZS) Predictors | Computational models (e.g., EVmutation, SIFT) that predict fitness effects without experimental data, using evolutionary or structural information. [9] | Used in ftMLDE to pre-filter libraries and create enriched training sets, improving model performance. [9] |

| Representation Learning Models (e.g., UniRep, ESM) | Unsupervised models trained on millions of protein sequences to learn low-dimensional, biophysically meaningful vector representations of sequences. [4] | Enables supervised learning in remarkably small data regimes (<100 examples) by providing powerful feature inputs. [4] |

| Benchmark Datasets (e.g., FLIP, ProteinGym) | Standardized public datasets and tasks for evaluating and comparing fitness prediction models. [18] | Critical for fair model comparison, benchmarking performance, and advancing the field. [4] |

| μProtein Framework | A combination of the μFormer (Transformer model) and μSearch (RL algorithm) for navigating fitness landscapes. [18] | Demonstrates the ability to find high-gain-of-function multi-mutants from single-mutant data alone. [18] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental difference between Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization in the context of protein engineering?

While both are iterative optimization strategies, their core objectives differ [19]:

- Active Learning aims to build the most accurate model possible of the entire protein fitness landscape while minimizing the number of expensive experimental measurements (labels). It does this by querying the points of highest uncertainty [20] [21].

- Bayesian Optimization (BO) aims to find the global optimum of a function—the single best protein sequence or variant—as efficiently as possible. It uses an acquisition function to balance exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known promising areas [22] [23] [19].

In short, Active Learning seeks to understand the entire map, while Bayesian Optimization is focused on finding the highest peak in the most direct way.

FAQ 2: My Bayesian Optimization algorithm is converging to a local optimum, not the global one. What could be wrong?

This is a common problem often linked to three key issues [23]:

- Incorrect Prior Width: An improperly specified prior for your surrogate model (e.g., a Gaussian Process) can hinder its ability to model the true complexity of the fitness landscape.

- Over-smoothing: A kernel with too large a lengthscale can oversmooth the model, causing it to miss narrow, high-value peaks in the fitness landscape.

- Inadequate Acquisition Maximization: If the process of finding the maximum of your acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) is not thorough, it may miss the most promising points to evaluate next.

FAQ 3: How do I choose the right query strategy for my Active Learning experiment on protein sequences?

The choice depends on your data and goals [20] [21]:

- Uncertainty Sampling: Best when you have a large pool of unlabeled data and want to improve overall model accuracy. It selects points where the model's prediction is least confident.

- Query by Committee: Useful when you can train multiple models. It selects points where a "committee" of models disagrees the most, indicating high uncertainty.

- Expected Model Change: Focuses on points that would cause the greatest change to the current model if their labels were known.

For protein landscapes with complex epistatic interactions, Query by Committee can be particularly effective as it naturally captures model disagreement arising from complex, non-linear relationships between mutations.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor Optimization Performance in Bayesian Optimization

Symptoms: The algorithm fails to find high-fitness protein variants, gets stuck in local optima, or shows slow improvement over iterations.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Check Surrogate Model | The Gaussian Process (GP) prior or kernel is mis-specified, leading to a poor fit of the protein fitness landscape [23]. | Tune the GP hyperparameters, especially the lengthscale and amplitude. Use a prior that reflects the expected smoothness and variability of your fitness function. |

| 2. Analyze Acquisition Function | The acquisition function (e.g., EI, UCB) is not effectively balancing exploration and exploitation [19]. | Adjust the exploration-exploitation trade-off. For UCB, increase the β parameter to encourage more exploration. For PI, adjust the ε parameter [19]. |

| 3. Verify Optimization | The internal maximization of the acquisition function is incomplete or gets stuck itself [23]. | Use a robust global optimizer (e.g., multi-start L-BFGS-B) to find the true maximum of the acquisition function in each iteration. |

Problem: Selecting an Ineffective Query Strategy in Active Learning

Symptoms: The model's performance does not improve significantly despite adding new data points, or the selected data points are not informative for the task.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Define Goal | The query strategy is misaligned with the ultimate goal of the experiment [21]. | If the goal is accurate landscape estimation, use uncertainty sampling. If the goal is finding high-performance variants, use a strategy that combines uncertainty with potential for high fitness, similar to BO. |

| 2. Assess Data Pool | The unlabeled data pool is not representative or lacks diversity. | Ensure your initial sequence library is diverse. Consider density-weighted strategies to select uncertain points that are also representative of the overall data distribution. |

| 3. Evaluate Model Uncertainty | The model's uncertainty estimates are unreliable. | Calibrate your model's confidence scores. For complex protein landscapes, use models that provide better uncertainty quantification, such as ensembles or Bayesian neural networks. |

Problem: High Experimental Cost and Labeling Bottleneck

Symptoms: The iterative cycle is prohibitively slow or expensive because the physical experiments (e.g., measuring protein activity) are a major bottleneck.

Diagnosis and Solution:

| Step | Diagnosis | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Analyze Batch Selection | The algorithm queries labels for points one-by-one, leading to many slow experimental cycles. | Implement batch active learning or batch BO. Select a diverse batch of points to query in parallel in each cycle, dramatically reducing the total number of experimental rounds [24]. |

| 2. Review Labeling Cost | Each experimental measurement is inherently expensive and time-consuming. | This is a fundamental constraint. The solution is to maximize the value of each experiment by using the strategies above to ensure every data point collected is highly informative [20] [24]. |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Standard Iterative Design-Test-Learn Cycle for Protein Engineering

This protocol outlines a generalized workflow for using Active Learning and Bayesian Optimization to navigate protein fitness landscapes.

1. Design Phase: * Input: A starting set of labeled protein sequences (initial training data). * Action: Train a surrogate model (e.g., Gaussian Process, Bayesian Neural Network) on the labeled data. The model learns to predict protein fitness from sequence. * Query: Using the trained model, evaluate a large pool of unlabeled candidate sequences. Apply an acquisition function (for BO) or query strategy (for AL) to select the most promising sequence(s) to test experimentally.

2. Test Phase: * Synthesis & Measurement: Physically create the selected protein variant(s) (e.g., via site-directed mutagenesis or gene synthesis) and measure their fitness/functions in a high-throughput assay [25].

3. Learn Phase: * Labeling: The measured fitness value becomes the label for the new sequence. * Update: Add the newly labeled sequence to the training dataset.

4. Iterate: * Repeat the Design-Test-Learn cycle until a performance target is met, the experimental budget is exhausted, or no further improvement is observed.

The following diagram illustrates this iterative cycle and its integration within a larger research infrastructure, as seen in production-grade MLOps systems [26].

Protocol 2: Inferring Fitness Landscapes from Laboratory Evolution Data

This protocol is based on a specific study that used a statistical learning framework to infer the DHFR fitness landscape from directed evolution data [25].

1. Laboratory Evolution Experiment: * Perform multiple rounds (e.g., 15 rounds) of mutagenesis and selection on the target protein (e.g., Dihydrofolate Reductase, DHFR). * In each round, apply random mutagenesis (e.g., error-prone PCR) and select functional variants under a specific selective pressure (e.g., antibiotic trimethoprim resistance) [25]. * Track the population size and diversity over generations.

2. Sequence Sampling: * At multiple generational timepoints, extract samples from the evolving population. * Perform high-throughput DNA sequencing to obtain a collection of protein sequences from rounds 1, 5, 10, 15, etc.

3. Model Building and Inference: * Model Assumptions: Assume the evolutionary process can be modeled as a Markov chain, where sequence transitions depend on mutational accessibility and relative fitness. Assume a time-homogeneous process [25]. * Landscape Parameterization: Parameterize the fitness landscape using a generalized Potts model, which captures the effects of individual residues and pairwise interactions on fitness. * Likelihood Maximization: Estimate the Potts model parameters by maximizing the likelihood of observing the sequenced evolutionary trajectories under the assumed Markov model.

4. Model Application: * Landscape Analysis: Use the learned model to identify key interacting residues, detect epistasis, and understand the global structure of the fitness landscape. * In Silico Extrapolation: Run evolutionary simulations in silico starting from a given sequence to predict future evolutionary paths or design new functional proteins.

The workflow below details the specific steps of this data-driven inference approach.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational and experimental resources essential for implementing the iterative cycles described in this guide.

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | Serves as the probabilistic model of the protein fitness landscape, providing predictions and uncertainty estimates for Bayesian Optimization [23] [19]. | Kernel: RBF (Radial Basis Function) with tunable lengthscale and amplitude. Implemented in libraries like GPyTorch or scikit-learn. |

| Acquisition Function | Guides the selection of the next sequence to test by balancing exploration and exploitation in BO [23] [19]. | Expected Improvement (EI), Upper Confidence Bound (UCB), or Probability of Improvement (PI). |

| Query Strategy (AL) | The algorithm that selects the most informative data points from the unlabeled pool in Active Learning [20] [21]. | Uncertainty Sampling, Query by Committee, or Expected Model Change. |

| Directed Evolution Platform | The experimental system for generating and selecting diverse protein variants [25]. | Error-prone PCR for mutagenesis, a selection assay (e.g., growth in antibiotic like trimethoprim for DHFR), and E. coli as a host organism. |

| High-Throughput Sequencer | Enables the sampling of sequence populations from multiple rounds of laboratory evolution for fitness landscape inference [25]. | Illumina MiSeq or NovaSeq systems. |

| Potts Model / Statistical Framework | A parameterized model used to infer the fitness landscape from evolutionary trajectories, capturing epistatic interactions [25]. | A generalized Potts model with parameters estimated via maximum likelihood. |

Leveraging Zero-Shot Predictors for Cold-Start Problems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core challenge of the "cold-start problem" in machine learning, particularly for protein engineering? The cold-start problem refers to the challenge where a machine learning system struggles to make accurate predictions for new users, items, or scenarios for which it has little to no historical data. In the context of protein fitness landscapes, this occurs when you need to predict the functional impact of mutations in a novel protein or a protein region without any prior experimental measurements. This data scarcity makes it difficult for models reliant on collaborative or supervised learning to generalize effectively [27] [28].

Q2: How does zero-shot learning specifically address this data scarcity? Zero-shot learning (ZSL) is a paradigm where a model can make predictions for tasks or classes it has never seen during training. It avoids dependence on labeled data for the specific new task by transferring knowledge from previously learned, related tasks, often using auxiliary information [29]. For protein fitness prediction, a zero-shot model pre-trained on a large corpus of protein sequences and structures can be applied to predict the fitness of novel protein variants without requiring any new labeled fitness data for that specific protein [30] [31].

Q3: My zero-shot model performs poorly on intrinsically disordered protein regions. Why? This is a recognized limitation. Zero-shot fitness prediction models often struggle with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) because these regions lack a fixed 3-dimensional structure. The model's performance is tied to the quality of the input structural data. Using predicted structures for these disordered regions can be misleading, as the prediction algorithms may generate inaccurate or overly rigid conformations that do not represent the protein's true biological state, ultimately harming predictive performance [30] [31].

Q4: What is a simple yet effective strategy to boost the performance of my zero-shot predictor? Implementing simple multi-modal ensembles is a strong and straightforward baseline. Instead of relying on a single type of data (e.g., only sequence or only structure), you can combine predictions from multiple models that leverage different data modalities. For instance, ensembling a structure-based zero-shot model with a sequence-based model can lead to more robust and accurate fitness predictions by capturing complementary information [30] [31].

Q5: How can I validate a zero-shot model's prediction for a novel protein variant in the wet-lab? A foundational experimental protocol is a deep mutational scan. This involves creating a library that encompasses many (or all) possible single-point mutations of your protein of interest and using high-throughput sequencing to quantitatively measure the fitness or function of each variant in a relevant assay. The experimentally measured fitness scores can then be directly compared to the model's zero-shot predictions for validation [30] [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Predictive Performance on Novel Protein Targets

Problem: Your zero-shot model shows low accuracy when predicting fitness for a protein family not well-represented in its training data.

Solution:

- Action 1: Employ Multi-Source Domain Adaptation. Techniques like the Multi-branch Multi-Source Domain Adaptation (MSDA) plug-in can be integrated with standard models. This approach learns invariant features from the prior response data of similar drugs or proteins, enhancing real-time predictions for novel, unlabeled compounds [33].

- Action 2: Build a Multi-Modal Ensemble. Combine the strengths of different model architectures.

- Procedure:

- Obtain predictions from at least two different pre-trained zero-shot models (e.g., a structure-based predictor and an language model-based sequence predictor).

- Aggregate the predictions using a simple method like averaging or a weighted average based on the models' past performance on a held-out benchmark.

- Expected Outcome: This ensemble approach can smooth out individual model biases and leverage complementary information, leading to a general performance improvement of 5-10% in challenging cold-start scenarios [30] [33].

- Procedure:

Issue 2: Handling Intrinsically Disordered Regions (IDRs)

Problem: Predictions are unreliable for proteins or regions that are intrinsically disordered.

Solution:

- Action 1: Prioritize Experimental Structures. Whenever possible, use experimental structural data (e.g., from NMR that captures conformational ensembles) for disordered regions instead of relying solely on computationally predicted structures [30] [31].

- Action 2: Match Structural Input to Fitness Assay. Ensure the structural context used for prediction (e.g., a protein's bound vs. unbound state) matches the functional context being measured in the fitness assay. A mismatch can significantly degrade performance [30].

- Action 3: Leverage Ensemble Methods. A multi-modal ensemble that includes predictions from models not solely dependent on 3D structure can help mitigate the limitations of structure-based predictors in disordered regions [31].

Issue 3: Model Hallucination and Unstable Recommendations

Problem: The model generates confident but incorrect predictions or provides inconsistent outputs for similar queries.

Solution:

- Action: Implement a Knowledge-Guided RAG Framework. Use a framework like ColdRAG, which combines Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) with a dynamically built knowledge graph.

- Procedure:

- Item Profiling: Transform available protein data (e.g., sequence, known domains, functional annotations) into a rich natural-language profile.

- Knowledge Graph Construction: Extract entities (e.g., protein names, domains, functions) and relations from these profiles to build a domain-specific knowledge graph that captures semantic connections.

- Reasoning-Based Retrieval: Given a user's query (e.g., "find proteins with similar fitness landscapes"), traverse the knowledge graph using LLM-guided edge scoring to retrieve candidate items with supporting evidence.

- Evidence-Grounded Ranking: Prompt the LLM to rank the final candidates based on the retrieved, verifiable evidence [28].

- Expected Outcome: This grounds the model's predictions in explicit evidence, substantially reducing hallucinations and improving the stability and explainability of recommendations in cold-start settings [28].

- Procedure:

Experimental Protocols & Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Cold-Start Strategies

This table summarizes quantitative improvements from different approaches to mitigating the cold-start problem, as reported in the literature.

| Strategy / Model | Dataset / Context | Key Metric | Performance Improvement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSDA (Zero-Shot DRP) | GDSCv2, CellMiner (Drug Response) | General Performance | 5-10% improvement | [33] |

| TxGNN (Zero-Shot Drug Repurposing) | Medical Knowledge Graph (17k diseases) | Treatment Prediction Accuracy | Up to 19% improvement | [34] |

| ColdFusion (Machine Vision) | Anomaly Detection Benchmark | AUROC Score | ~21 percentage point increase (from ~61% to ~82%) | [35] |

| ColdRAG (LLM Recommendation) | Multiple Public Benchmarks | Recall & NDCG | Outperformed state-of-the-art zero-shot baselines | [28] |

| Transfer Learning (Inventory Mgmt) | Simulated New Products | Average Daily Cost | 23.7% cost reduction | [35] |

Protocol 1: Benchmarking a Zero-Shot Protein Fitness Predictor

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the performance of a zero-shot structure-based fitness prediction model on a set of protein variants with known experimental fitness measurements.

Materials:

- A curated benchmark dataset like ProteinGym, which contains deep mutational scanning data for numerous proteins [30] [31].

- Pre-trained zero-shot fitness prediction model(s).

- Protein structures (experimental or predicted via tools like AlphaFold2) corresponding to the wild-type sequences in your benchmark.

Methodology:

- Input Preparation: For each protein variant in the benchmark (e.g., a single-point mutation), generate the input features required by your model. For structure-based models, this typically involves the 3D coordinates of the wild-type and/or mutant structure [30].

- Zero-Shot Inference: Run the pre-trained model on each variant without any training or fine-tuning on the target protein's data. Collect the model's predicted fitness score for each variant.

- Performance Calculation: Compare the model's predictions against the ground-truth experimental fitness values. Common metrics include:

- Spearman's Rank Correlation: Measures the monotonic relationship between predicted and true scores, assessing if the model can correctly rank variants by fitness.

- Pearson's Correlation: Measures the linear correlation between predicted and true scores.

- AUC-ROC: Useful if fitness is binarized (e.g., functional vs. non-functional) [30] [31].

Protocol 2: Conducting a Deep Mutational Scan (DMS) for Validation

Objective: To experimentally generate a ground-truth fitness landscape for a protein, against which computational predictions can be validated.

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Synthesize a gene library encoding the wild-type protein and all single-amino-acid mutants (or a targeted subset) you wish to test.

- Functional Selection: Clone this library into an expression system and subject the population to a functional assay that links protein fitness (e.g., enzymatic activity, binding affinity, growth rate) to cell survival or a selectable marker.

- Sequencing and Quantification: Use high-throughput DNA sequencing (e.g., Illumina) to count the frequency of each variant in the population both before and after selection.

- Fitness Score Calculation: For each variant, calculate an enrichment score based on its change in frequency during selection. This enrichment score serves as the experimental measure of fitness [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Item | Function in Research | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| ProteinGym Benchmark | A standardized benchmark suite for assessing protein fitness prediction models on deep mutational scanning data. | Critical for fair comparison of zero-shot and other prediction methods [30] [31]. |

| Predicted Protein Structures | Serve as input features for structure-based zero-shot predictors when experimental structures are unavailable. | Resources like AlphaFold Protein Structure Database provide pre-computed predictions [30]. |

| Deep Mutational Scanning (DMS) Data | Provides ground-truth experimental fitness measurements for thousands of protein variants, used for model training and validation. | Available for specific proteins in repositories like the ProteinGym dataset [30] [32]. |

| Knowledge Graph | A structured representation of biological knowledge (entities and relations) that enables reasoning and evidence retrieval for frameworks like ColdRAG. | Can be dynamically built from protein databases and literature [28]. |

| Multi-modal Ensemble Framework | A software approach to combine predictions from diverse models (sequence-based, structure-based) to improve accuracy and robustness. | Simple averaging is a strong baseline; more complex weighting can be explored [30] [31]. |

Workflow and Strategy Visualizations

Diagram 1: Zero-Shot Protein Fitness Prediction Workflow

Diagram 2: Knowledge-Guided RAG for Cold-Start

Diagram 3: Multi-Modal Ensemble Strategy

Generative Models and Reinforcement Learning for Novel Sequence Design

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Common Experimental Problems and Solutions

Problem 1: Poor Fitness of Generated Protein Sequences

- Question: "My generative model produces sequences that score well on the likelihood metric but show low fitness in experimental assays. What could be wrong?"

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause A: Distributional Mismatch. The generative prior (e.g., a protein language model) is biased towards its training data (like natural sequences from the PDB) and may not cover high-fitness regions for your specific function [36].

- Solution: Implement a steering strategy. Use plug-and-play guidance with a fitness predictor to condition the generative model on your property of interest without retraining the base model [37] [38]. For example, apply ProteinGuide to bias models like ESM3 or ProteinMPNN towards sequences with higher stability or activity [38].

- Cause B: Inadequate Exploration. The optimization is stuck in a local optimum.

- Solution: Integrate uncertainty-aware exploration. Ensemble multiple fitness predictors and use their predictive uncertainty to guide the search, similar to principles in Bayesian optimization [37]. Alternatively, use reinforcement learning (RL) algorithms like GRPO or wDPO which are designed to escape local optima [36].

Problem 2: Handling Small Labeled Datasets

- Question: "I only have a few hundred labeled sequence-fitness pairs. Which method is most effective for leveraging this data?"

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Solution A: Steered Generative Protein Optimization (SGPO). Frameworks like SGPO are specifically designed to work with small amounts (hundreds) of labeled data. They combine a generative prior with a fitness predictor for conditional generation, which is more data-efficient than training a supervised model from scratch [37].

- Solution B: Posterior Sampling. Techniques like decoupled annealing posterior sampling have shown strong performance in SGPO contexts with limited labels [37]. Plug-and-play guidance methods also reduce training costs compared to fine-tuning large models [37] [38].

Problem 3: Model Generates Unrealistic or Poorly-Structured Sequences

- Question: "The sequences my optimized model generates are not protein-like and are predicted to have poor structure. How can I maintain structural integrity?"

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Lack of Structural Priors. The optimization process has drifted away from the manifold of foldable sequences.

- Solution: Use a generative model with a strong structural prior. Integrate a confidence metric like pLDDT from a structure prediction model (e.g., ESMFold) as a reward signal during RL-based alignment [36]. Alternatively, use an inverse folding model like ProteinMPNN, which is inherently conditioned on backbone structure, and guide it with your fitness function [38].

Problem 4: Choosing Between Reinforcement Learning and Guidance

- Question: "When should I use reinforcement learning versus plug-and-play guidance for my protein optimization project?"

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Solution: The choice depends on your goals and resources. The table below summarizes key considerations based on recent research:

Table: RL vs. Guidance for Protein Design

| Feature | Reinforcement Learning (e.g., ProtRL, PPO) | Plug-and-Play Guidance (e.g., ProteinGuide, SGPO) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Use Case | Permanently aligning a model's distribution to a new reward function [36]. | On-the-fly conditioning of a pre-trained model on a new property [38]. |

| Computational Cost | Higher (requires fine-tuning model parameters) [37]. | Lower (leaves model weights unchanged) [37] [38]. |

| Steerability | Can dramatically shift output distribution (e.g., change protein fold) [36]. | Effective at property enhancement while maintaining core sequence features [38]. |

| Best for | Long-term, dedicated projects aiming for a specialized model. | Rapid prototyping, iterative design-test cycles, and applying multiple different constraints. |

FAQ: Strategic Experimental Design

Q1: My fitness landscape is known to be rugged and epistatic. What ML strategy should I prioritize? A1: For rugged landscapes, Machine Learning-Assisted Directed Evolution (MLDE) and active learning (ALDE) strategies have been shown to outperform traditional directed evolution. Focused training (ftMLDE) that enriches your training set with high-fitness variants, selected using zero-shot predictors, can be particularly effective in navigating such complex terrains [9].

Q2: How can I integrate wet-lab experimental data back into the computational design cycle? A2: This is a core strength of iterative steered generation frameworks.

- Design: Use a generative model (e.g., a diffusion model or a protein language model) to create an initial library of sequences.

- Build & Test: Synthesize and assay these sequences in the lab for your target fitness property.

- Learn: Train a regression or classification model on the newly acquired experimental data.

- Guide: Use this newly trained predictor to guide the same generative model in the next design round, creating sequences predicted to have even higher fitness [37] [38]. This creates a closed-loop, adaptive optimization system.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Iterative Steered Generation for Protein Optimization (SGPO)

This protocol is adapted from studies on optimizing proteins like TrpB and CreiLOV using small labeled datasets [37].

1. Initial Library Generation

- Input: A pre-trained generative prior model (e.g., a discrete diffusion model or a protein language model like ESM3).

- Procedure: Generate an initial set of candidate protein sequences. This can be unconditional or conditioned on a starting scaffold.

- Output: A library of sequences (e.g., 2,000 variants) for the first round of testing.

2. Wet-Lab Fitness Assay

- Procedure: Clone, express, and purify the generated protein variants. Measure the desired quantitative property (e.g., enzymatic activity, fluorescence, binding affinity) using a low-throughput assay.

- Output: A dataset of several hundred labeled sequence-fitness pairs.

3. Fitness Predictor Training

- Input: The collected sequence-fitness data.

- Procedure: Train a supervised model (e.g., a regression model for continuous fitness or a classifier for high/low activity) to predict fitness from sequence.

- Output: A trained fitness predictor.

4. Guided Generation for Subsequent Rounds

- Input: The generative prior from Step 1 and the fitness predictor from Step 3.

- Procedure: Use a steering strategy to guide the generative model. For diffusion models, apply classifier guidance or posterior sampling. For other models, use a framework like ProteinGuide [38].

- Optional - Adaptive Sampling: Ensemble multiple fitness predictors to also estimate predictive uncertainty. Use a strategy akin to Thompson sampling to balance exploration (trying uncertain sequences) and exploitation (trying high-predicted-fitness sequences) [37].

- Output: A new, optimized library of sequences for the next round of testing.

5. Iteration

- Repeat steps 2-4 for multiple rounds, using the experimental data from each round to refine the fitness predictor and guide subsequent designs.

Protocol 2: Aligning Protein Language Models with Reinforcement Learning

This protocol is based on the ProtRL framework for shifting a model's distribution towards a desired property [36].

1. Base Model and Reward Definition

- Base Model: Select a pre-trained autoregressive protein language model (e.g., ZymCTRL).

- Reward Function: Define a reward function that quantifies the desired property. This can be an oracle (e.g., TM-score for structural similarity to a target fold) or a predictor (e.g., a classifier for a specific enzyme class).

2. Sequence Generation and Evaluation

- Procedure: The base model generates a batch of sequences.

- Evaluation: Each generated sequence is scored by the reward function.

3. Policy Optimization

- Algorithm Selection: Choose an RL algorithm such as:

- GRPO (Group Relative Policy Optimization): Draws multiple samples and computes advantage for each token based on the group's reward distribution [36].

- wDPO (Weighted Direct Preference Optimization): Learns directly from a dataset of preferred and non-preferred sequences without explicitly training a reward model [36].

- Procedure: Use the rewards and the chosen algorithm to compute a policy gradient and update the weights of the base language model.

4. Iteration

- Repeat steps 2 and 3 over multiple rounds. The model's policy (its sequence generation behavior) will progressively align with the reward function, increasing the likelihood of generating high-reward sequences.

Experimental Workflow Visualizations

Diagram 1: SGPO Adaptive Optimization Cycle

Diagram 2: RL for Protein Language Models

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Tools and Models for Generative Protein Design

| Research Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| ESM3 [38] [39] | Generative Protein Language Model | A foundational model for generating protein sequences and structures. Can be guided or fine-tuned for specific tasks. |

| ProteinMPNN [38] | Inverse Folding Model | Generates sequences that are likely to fold into a given protein backbone structure. |

| ProteinGuide [38] | Guidance Framework | A general method for plug-and-play conditioning of various generative models (ESM3, ProteinMPNN) on auxiliary properties. |

| ProtRL [36] | Reinforcement Learning Framework | Implements RL algorithms (GRPO, wDPO) to align autoregressive protein language models with custom reward functions. |

| Discrete Diffusion Models (e.g., EvoDiff, DPLM) [37] [39] | Generative Model | Models for generating protein sequences; offer advantages for plug-and-play guidance strategies like classifier guidance. |

| Fitness Predictor | Supervised Model | A regression or classification model (trained on experimental data) that predicts protein fitness from sequence. Serves as the guide or reward signal. |