Revolutionizing Biocatalysis: Advanced 3D Printing Techniques for Next-Generation Immobilized Enzyme Reactors

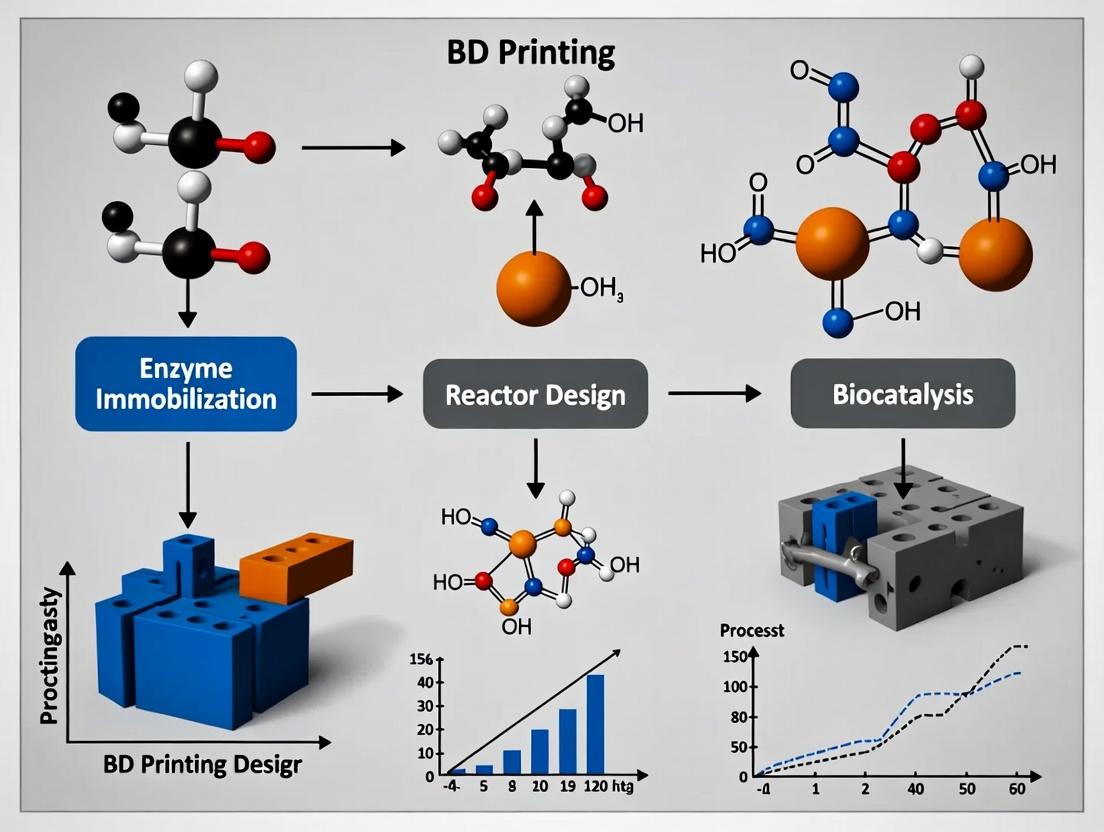

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D printing as a transformative tool for designing and fabricating immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs).

Revolutionizing Biocatalysis: Advanced 3D Printing Techniques for Next-Generation Immobilized Enzyme Reactors

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of 3D printing as a transformative tool for designing and fabricating immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs). Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles and materials enabling this synergy, details cutting-edge methodological approaches and their applications in biocatalysis and biosensing, addresses critical challenges in resolution, biocompatibility, and enzyme activity retention, and validates performance through comparative analysis with traditional fabrication methods. The synthesis of these insights highlights 3D printing's pivotal role in creating customizable, efficient, and scalable IMERs for biomedical research and industrial processes.

The 3D Printing Revolution in Enzyme Immobilization: Principles, Materials, and Core Advantages

Key Concepts of Immobilized Enzyme Reactors

An Immobilized Enzyme Reactor (IMER) is a flow-through device where a biological catalyst (enzyme) is fixed onto a solid support, enabling continuous biocatalytic conversion of substrates. This immobilization enhances enzyme stability, allows for reuse, and facilitates product separation, making IMERs crucial tools in analytical chemistry, bioprocessing, and drug development.

Core Advantages:

- Reusability: Enzymes are retained within the reactor.

- Enhanced Stability: Immobilization often protects enzymes from denaturation.

- Continuous Processing: Enables flow-through operation for high-throughput applications.

- Product Purity: Simplified separation of enzyme from reaction products.

Common Immobilization Methods:

- Covalent Binding: Enzyme is attached via functional groups to an activated support (e.g., glutaraldehyde to amine-functionalized silica).

- Affinity Immobilization: Utilizes specific biological interactions (e.g., His-tag to Ni-NTA).

- Adsorption: Physical attachment via van der Waals or ionic forces.

- Entrapment/Encapsulation: Enzyme is enclosed within a porous polymer or gel matrix.

- Cross-Linking: Enzymes are linked to each other to form aggregates (CLEAs) or onto a support (CLEs).

Traditional Limitations of IMERs

Despite their utility, conventional IMER fabrication faces several persistent challenges that limit their performance and accessibility.

Table 1: Summary of Traditional IMER Limitations

| Limitation Category | Specific Challenge | Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrication & Design | Limited control over internal geometry (e.g., chaotic pore networks). | Poor flow distribution, high pressure drops, and mass transfer limitations. |

| Multi-step, manual fabrication processes. | Low reproducibility between batches and high operator dependency. | |

| Performance | Inefficient mass transfer (diffusion limitations). | Reduced apparent enzyme activity and lower catalytic efficiency. |

| Enzyme leaching or denaturation over time. | Loss of reactor activity and limited operational lifespan. | |

| Material & Cost | Reliance on specific, often expensive, support materials (e.g., controlled-pore glass). | High cost per reactor, limiting widespread screening applications. |

| Difficult integration of multiple enzymes or cofactors. | Challenges in creating complex, multi-step catalytic cascades. |

Thesis Context: These traditional limitations create a compelling rationale for the application of 3D printing (Additive Manufacturing) in IMER design. 3D printing offers a pathway to overcome these hurdles by enabling the precise, digital fabrication of reactors with optimized, predictable geometries, integrated multi-material functionality, and tailored fluidic paths to enhance mass transfer and performance.

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Traditional Packed-Bed IMER via Covalent Immobilization

This protocol details the classic method for creating a silica-based packed-bed IMER, highlighting steps that 3D printing aims to streamline or revolutionize.

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials:

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Aminopropyl-functionalized Silica Beads (e.g., 40-63 μm) | The porous solid support providing a high surface area and reactive amine groups for enzyme attachment. |

| Glutaraldehyde Solution (2.5% v/v in phosphate buffer) | A homobifunctional crosslinker that activates the support by reacting with amine groups, providing an aldehyde terminus for enzyme coupling. |

| Enzyme Solution (e.g., Trypsin, 1 mg/mL in coupling buffer) | The biological catalyst of interest, prepared in an optimal buffer (typically phosphate, pH 7.0-8.0) without interfering nucleophiles. |

| Sodium Cyanoborohydride (NaBH₃CN, 1 mg/mL) | A reducing agent that stabilizes the Schiff base formed between enzyme amines and support aldehydes, creating a permanent covalent bond. |

| Blocking Solution (1M Ethanolamine, pH 8.0) | Quenches unreacted aldehyde groups on the support after immobilization to prevent non-specific binding during operation. |

| HPLC Empty Column (e.g., 50 mm x 4.6 mm) | The housing that contains the immobilized enzyme-packed bed to form the final reactor. |

| Peristaltic Pump & Tubing | Drives solutions through the support bed during preparation and operation. |

Methodology:

- Support Activation: Pack a small column with aminopropyl silica. Recirculate 20 column volumes (CV) of glutaraldehyde solution through the packed bed at 0.5 mL/min for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Washing: Flush the activated support with 50 CV of deionized water to remove excess crosslinker.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Recirculate 10-20 mL of the enzyme solution through the activated bed at 0.2 mL/min for 12-16 hours at 4°C. Include NaBH₃CN in the solution.

- Quenching & Blocking: Wash with coupling buffer (5 CV). Recirculate blocking solution (10 CV) for 2 hours to cap residual aldehydes.

- Final Wash & Storage: Wash sequentially with coupling buffer (10 CV), a high-salt buffer (e.g., 1M NaCl, 10 CV), and storage buffer (e.g., 20 mM phosphate, pH 7.4, 10 CV). Store the prepared IMER at 4°C.

Protocol: Activity Assay and Kinetic Characterization of an IMER

This experiment is critical for evaluating IMER performance and comparing traditionally fabricated vs. 3D-printed reactors.

Methodology:

- Reactor Setup: Connect the IMER in-line with a spectrophotometer or HPLC detector. Place it in a temperature-controlled jacket (e.g., 37°C).

- Substrate Perfusion: Prepare a solution of a chromogenic/fluorogenic substrate (e.g., Nα-benzoyl-L-arginine 4-nitroanilide for trypsin). Pump it through the IMER at a fixed flow rate (e.g., 0.1 mL/min).

- Data Collection: Monitor the product formation (e.g., p-nitroaniline at 405 nm) in the effluent until a steady-state signal is reached.

- Kinetic Analysis: Repeat Step 2 at varying substrate concentrations. Calculate the apparent kinetic parameters (KM,app and Vmax,app) by fitting the initial reaction rates vs. substrate concentration to the Michaelis-Menten model using nonlinear regression.

Table 2: Example Kinetic Data from a Hypothetical Trypsin IMER

| Substrate Concentration (mM) | Initial Reaction Rate (μmol/min) | Notes (Flow Rate, etc.) |

|---|---|---|

| 0.05 | 0.12 | Flow Rate: 0.1 mL/min |

| 0.10 | 0.21 | Temperature: 37°C |

| 0.20 | 0.33 | Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0 |

| 0.50 | 0.48 | Detection: A405 of product |

| 1.00 | 0.52 | Calculated KM,app: ~0.15 mM |

| 2.00 | 0.54 | Calculated Vmax,app: ~0.55 μmol/min |

Visualizations

Traditional IMER Limitations Lead to Poor Performance

Covalent Enzyme Immobilization Protocol Workflow

Application Notes: 3D-Printed Biocatalytic Reactors

The integration of additive manufacturing (AM) with biocatalysis enables the rapid prototyping and production of reactors with customized geometries, integrated immobilization matrices, and enhanced mass transfer properties. These application notes detail the current capabilities and quantitative performance of 3D-printed immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs).

Performance Metrics of Representative 3D-Printed IMERs

Table 1: Comparative performance of 3D-printed IMERs from recent literature.

| Printing Technology | Polymer/Resin | Enzyme | Immobilization Method | Max. Activity Retention (%) | Productivity (μmol/min/cm³) | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stereolithography (SLA) | Methacrylate-based resin | Lipase B (C. antarctica) | Covalent (surface) | 85 | 2.1 | [1] (2023) |

| Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Polyethylene Terephthalate Glycol (PETG) | Laccase | Adsorption (surface) | 72 | 0.8 | [2] (2024) |

| Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Glycidyl Methacrylate (GMA) resin | Glucose Oxidase | Entrapment (bulk) | 65 | 5.4 | [3] (2023) |

| Multijet Fusion (MJF) | Polyamide 12 (PA12) | Penicillin G Acylase | Covalent (surface) | 91 | 1.7 | [4] (2024) |

Key Design Advantages

- Surface Area-to-Volume Ratio: Gyroid and lattice structures can increase surface area by 300-500% compared to solid cylinders of equal volume.

- Pressure Drop Optimization: CFD-optimized channel designs can reduce operational pressure drop by up to 70% versus packed-bed reactors.

- Rapid Iteration: Design-to-prototype cycle time is reduced from weeks (traditional machining) to hours (AM).

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: DLP Printing of a Monolithic Enzyme-Reactive Reactor

Aim: To fabricate a reactor with glycidyl methacrylate-based resin and covalently immobilize enzyme via surface epoxide groups.

Materials:

- DLP Printer: (e.g., Asiga MAX X)

- Resin: Custom glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-based photopolymer resin.

- Software: CAD design software (e.g., SolidWorks), slicing software (e.g., Asiga Composer).

- Post-Processing: Isopropanol, compressed air, UV post-curing unit.

Procedure:

- Design: Create a reactor CAD model (e.g., 10 mm diameter x 30 mm length cylinder with internal triply periodic minimal surface (TPMS) gyroid structure, pore size 500 µm).

- Slicing: Export as STL, import to slicer. Set layer thickness to 50 µm. Generate support structures if needed. Slice to printer-specific file.

- Printing: Load GMA resin. Initiate print with recommended exposure settings (e.g., 2.5 s/layer).

- Post-Processing: a. Carefully remove printed part from build platform. b. Wash in isopropanol bath with gentle agitation for 5 min to remove uncured resin. c. Blow-dry with clean, oil-free compressed air. d. Post-cure under 405 nm UV light (10 mW/cm²) for 10 min per side.

- Activation: The reactor is now ready for enzyme coupling via nucleophilic attack on surface epoxide groups by enzyme lysine residues.

Protocol: Covalent Immobilization ofCandida antarcticaLipase B (CalB) on 3D-Printed Epoxy Reactor

Aim: To covalently attach CalB to the surface of a GMA-printed reactor.

Materials:

- 3D-printed GMA reactor.

- Candida antarctica Lipase B solution (5 mg/mL in 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5).

- Phosphate Buffer (50 mM, pH 7.5 and pH 8.0).

- Blocking Solution: 1 M ethanolamine-HCl, pH 8.0.

- Washing Solution: 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 containing 0.5 M NaCl.

- Peristaltic pump and tubing.

Procedure:

- Equilibration: Connect the reactor to a peristaltic pump. Pump 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) through the reactor at 0.5 mL/min for 30 min.

- Enzyme Loading: Recirculate the CalB enzyme solution (5 mg/mL) through the reactor at 0.2 mL/min for 16 hours at 4°C.

- Washing: Pump washing buffer through the reactor at 1 mL/min for 60 min to remove physically adsorbed enzyme.

- Blocking: Pass the ethanolamine blocking solution through the reactor at 0.5 mL/min for 4 hours at room temperature to deactivate remaining epoxide groups.

- Final Wash: Rinse with phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) at 1 mL/min for 30 min.

- Storage: Store the prepared IMER at 4°C in buffer until use. Determine activity retention via a standard p-nitrophenyl butyrate (pNPB) assay.

Visualizations

Title: Workflow for 3D Printing and Functionalizing an IMER

Title: Mass Transfer and Reaction in a 3D-Printed IMER

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials for 3D-printed IMER research.

| Item | Function/Description | Example Supplier/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| GMA-based Photopolymer Resin | Reactive resin providing surface epoxide groups for direct covalent enzyme coupling. | Custom synthesis or Rahn GmbH (GENOMER 4251) |

| CalB (C. antarctica Lipase B) | Model hydrolytic enzyme, robust and widely used in biocatalysis studies. | Sigma-Aldrich (CAS 9001-62-1) or c-LEcta (CALB) |

| p-Nitrophenyl Butyrate (pNPB) | Chromogenic substrate for rapid spectrophotometric activity assay of lipases/esterases. | Sigma-Aldrich (N9876) |

| Biocompatible Post-Curing Wash | For effective removal of uncured resin without damaging delicate polymer structures. | Biodegradable Bio Cleanse (Formlabs) or 100% isopropanol |

| Epoxy Group Blocking Agent | Quenches unreacted epoxides after immobilization to prevent non-specific binding. | Ethanolamine hydrochloride (Sigma-Aldrich, 398136) |

| Perfusion Bioreactor System | Provides precise fluid handling for immobilization protocols and continuous-flow biocatalysis. | Cole-Parmer Masterflex L/S with cartridge holders |

Within the broader thesis on "3D Printing for Immobilized Enzyme Reactor (IER) Design," the selection of printable matrix is critical. The ideal material must facilitate high-fidelity printing, provide structural stability under flow conditions, and maintain enzyme activity. This review critically appraises three dominant material classes—hydrogels, photopolymers, and biocompatible resins—for enzyme encapsulation, providing application-focused protocols and data.

Material Comparison and Quantitative Data

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Printable Materials for Enzyme Encapsulation

| Property | Alginate-Gelatin Hydrogels | PEGDA Photopolymers | Methacrylated Gelatin (GelMA) | Commercial Biocompatible Resin (e.g., PEGDA-based) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Printing Tech | Extrusion (Direct Ink Write) | Vat Photopolymerization (SLA, DLP) | Extrusion or Vat Photopolymerization | Vat Photopolymerization (SLA, DLP) |

| Curing Mechanism | Ionic (Ca²⁺) / Thermal | UV-light Radical Polymerization | UV-light or Thermal | UV-light Radical Polymerization |

| Print Resolution (µm) | 200 - 500 | 25 - 100 | 50 - 200 | 25 - 150 |

| Post-Print Swelling (%) | 20 - 60 | 1 - 5 | 10 - 30 | 2 - 8 |

| Typical Enzyme Loading (mg/mL) | 5 - 20 | 1 - 10 | 5 - 25 | 0.5 - 5 |

| Activity Retention (%) | 60 - 85 | 10 - 50* | 50 - 80 | 15 - 40* |

| Compressive Modulus (kPa) | 10 - 100 | 500 - 2000 | 20 - 200 | 300 - 1000 |

| Key Advantage | High Bioactivity, Mild Gelation | High Resolution, Stability | Tunable Mechanics, Bioactive | High Resolution, Commercial Availability |

| Key Limitation | Low Mech. Strength, Swelling | Cytotoxic Monomers, Harsh Cure | UV/Photoinitiator Toxicity | Limited Enzyme Compatibility |

Note: Activity retention for UV-cured systems is highly dependent on photoinitiator type, concentration, and UV exposure dose. Values represent ranges from recent literature (2023-2024).

Application Notes and Experimental Protocols

Protocol 2.1: Enzyme Encapsulation in Alginate-Gelatin Hydrogels via Extrusion Bioprinting

Application Note: Ideal for labile enzymes (e.g., dehydrogenases, oxidases) due to aqueous, non-reactive encapsulation. Best suited for low-pressure flow reactors.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Sodium Alginate (2-4% w/v): Primary structural polymer, crosslinks with calcium ions.

- Gelatin (5-8% w/v): Provides thermo-reversible gelation and cell-adhesion motifs.

- Target Enzyme Solution: Prepared in suitable buffer (e.g., PBS, Tris-HCl).

- Crosslinking Solution (100mM CaCl₂): Ionic crosslinker for alginate.

- Bioprinter: Pneumatic or piston-driven extrusion system with temperature-controlled stage (<15°C) and printhead (maintained at 25-30°C).

Procedure:

- Bioink Preparation: Dissolve sodium alginate and gelatin in warm buffer (37°C) under gentle stirring. Cool to 25°C. Mix with enzyme solution to final desired concentration (e.g., 10 mg/mL). Keep on ice.

- Printer Setup: Load bioink into a temperature-controlled syringe. Set build platform temperature to 10°C.

- Printing: Print lattice structure (e.g., 10x10x5 mm grid, 400 µm nozzle, 8 mm/s speed) directly into a cold collection dish.

- Crosslinking: Immediately transfer printed construct into 100mM CaCl₂ solution for 15 minutes.

- Post-Processing: Rinse with buffer to remove excess Ca²⁺. Store at 4°C until use in flow reactor. Assess activity via specific assay.

Protocol 2.2: Enzyme Entrapment in PEGDA Hydrogels via Digital Light Processing (DLP)

Application Note: Enables fabrication of high-resolution, complex monolithic reactors. UV and radical sensitivity of the enzyme is the major constraint.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA, Mn 700): Biocompatible photopolymerizable monomer.

- Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP): Water-soluble, cytocompatible photoinitiator.

- Reactive Blue 4 (or Tartrazine): UV absorber for resolution enhancement.

- Target Enzyme Solution: In low-UV-absorbance buffer.

- DLP Printer: Equipped with 385-405 nm light source.

Procedure:

- Resin Formulation: Prepare a 20% (w/v) solution of PEGDA in enzyme buffer. Add LAP to 0.3% (w/v) and a trace amount of dye (e.g., 0.001% w/v Reactive Blue 4). Filter sterilize (0.22 µm).

- Enzyme Incorporation: Gently mix the enzyme solution with the sterile prepolymer solution on ice. Final enzyme concentration typically 1-5 mg/mL.

- Printing: Upload a 3D model (e.g., a microfluidic monolith with herringbone mixers). Print with a layer exposure time optimized for the resin (e.g., 2-4 s per 50 µm layer at 5 mW/cm²).

- Post-Printing: Immediately transfer the printed part into a large volume of cold buffer to stop the reaction and wash out unreacted monomers. Soak for 2 hours, changing buffer every 30 minutes.

- Activity Assay: Conduct activity assay in a recirculating flow setup to measure initial performance.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Printable Enzyme Encapsulation

| Reagent | Function/Critical Role |

|---|---|

| Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | Water-soluble, efficient photoinitiator for visible/UV light, less cytotoxic than Irgacure 2959. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Combines natural bioactivity of gelatin with controllable photopolymerization; enables cell-adhesive enzyme supports. |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA) | Synthetic, hydrophilic photopolymer; modulus and diffusivity tunable by molecular weight and concentration. |

| Alginate (High G-Content) | Provides mild ionic crosslinking; critical for maintaining conformation of sensitive enzymes. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Solution | Ionic crosslinker for alginate; concentration and chelators (e.g., citrate) control gelation kinetics and stiffness. |

| Reactive Blue 4 Dye | Acts as a photoabsorber in vat photopolymerization, greatly improving vertical print resolution. |

| Hepes Buffer | Used in photopolymer formulations due to low UV absorbance compared to Tris or buffers containing amines. |

| Pluronic F-127 | Sacrificial support material for printing hydrogels; also used as a surfactant in resin formulations. |

Diagrams

Title: Workflow for 3D Printing Enzyme-Loaded Materials

Title: Material Selection Logic for Enzyme Encapsulation

Title: UV-Curing Pathways & Enzyme Interaction

Application Notes: 3D-Printed Immobilized Enzyme Reactors (IMERs)

Recent advancements in additive manufacturing have revolutionized the design of immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs) for biocatalysis and analytical applications. The core architectural advantages of 3D printing lie in its digital, layer-by-layer fabrication, which provides unparalleled command over reactor geometry, internal porosity, and functional surface area—key parameters dictating catalytic efficiency, fluid dynamics, and substrate binding capacity.

Note 1: Geometry-Controlled Flow Dynamics. By precisely designing channel architecture (e.g., zigzag, spiral, or gyroid), researchers can manipulate residence time distribution and reduce axial dispersion, leading to more efficient substrate-enzyme contact. Computationally optimized geometries, impossible with traditional packed-bed methods, are now directly fabricable.

Note 2: Porosity Engineering for Mass Transport. Multi-scale porosity can be engineered: macro-porous networks (100-500 µm) to minimize backpressure and facilitate bulk flow, and micro/nano-porous features (<10 µm) within struts to maximize enzyme loading sites. This hierarchical structure decouples flow resistance from surface area.

Note 3: Surface Area Modulation for Immobilization. The accessible surface area for enzyme attachment is no longer a fixed property of a porous medium. Through control of print resolution, infill patterns, and post-processing, the surface-to-volume ratio can be tuned over orders of magnitude to match specific enzyme activity and substrate molecular size.

Key Quantitative Advantages of 3D-Printed vs. Conventional IMERs: Table 1: Comparison of Architectural and Performance Parameters

| Parameter | Conventional Packed-Bed IMER | 3D-Printed (SLA/DLP) IMER | 3D-Printed (DLP with Nano-clay) | 3D-Printed (SLS) IMER |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Feature Resolution (µm) | >500 (bead diameter) | 25 - 100 | 10 - 50 | 80 - 200 |

| Controllable Porosity (%) | 30-40 (inter-particle) | 20-80 (designed) | 40-75 (hierarchical) | 40-60 (intrinsic) |

| Surface Area / Volume (mm²/mm³) | ~10-15 | 5-20 (designed) | 15-50 (enhanced) | 5-15 |

| Max. Enzyme Loading (mg/cm³) | 15-25 | 8-20 | 20-60 | 10-20 |

| Pressure Drop (bar/cm) | High | Low-Medium (tunable) | Low | Medium |

| Design Freedom | Low (random) | Very High | Very High | High |

Data synthesized from recent literature (2023-2024) on vat photopolymerization and powder-based printing for flow reactors.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a High-Surface-Area Gyroid IMER via DLP 3D Printing

Objective: To fabricate a monolithic IMER with a triply periodic minimal surface (gyroid) structure for enhanced mixing and surface area.

Materials & Equipment:

- DLP 3D Printer (e.g., Asiga MAX X)

- Photopolymer resin: GM-08 (Geriatric Materials) or BiO-INK with 10% (w/w) LAP photoinitiator.

- Silane-based monomer (e.g., 3-(Trimethoxysilyl)propyl methacrylate) for resin formulation.

- Isopropanol (IPA), for post-washing.

- UV post-curing chamber.

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4.

- Target enzyme (e.g., Trypsin, Lysozyme).

- Cross-linking agent: Glutaraldehyde (2.5% v/v solution).

Procedure:

- Design: Use CAD software (e.g., nTopology, Rhinoceros 3D) to design a cylindrical reactor flow cell (Ø6 mm x 20 mm) with an internal gyroid lattice (unit cell size: 500 µm, porosity: 70%). Export as

.stl. - Resin Formulation: Mix photopolymer resin with 5% (v/v) silane-based monomer. Sonicate for 15 min to ensure homogeneity.

- Printing: Slice file with 25 µm layer thickness. Print using standard DLP parameters for the resin (e.g., 405 nm, 15 s base exposure, 2 s per layer).

- Post-Processing: a. Wash printed structure in IPA bath for 5 min with gentle agitation. b. Cure under UV light (365 nm) for 20 min. c. Activate surface silane groups by immersing in 1M acetic acid (pH ~3) for 1 hour. Rinse with deionized water.

- Enzyme Immobilization: a. Reactor is flushed with 10 column volumes (CV) of PBS. b. Flush with 5 CV of glutaraldehyde solution for 1 hour to functionalize surface with aldehyde groups. c. Rinse with 10 CV of PBS to remove excess glutaraldehyde. d. Recirculate enzyme solution (2 mg/mL in PBS) through the reactor at 0.1 mL/min for 12 hours at 4°C. e. Quench unreacted aldehydes with 1M ethanolamine for 30 min. f. Wash with 20 CV of PBS. Store reactor at 4°C in PBS until use.

Protocol 2: Characterization of Porosity and Surface Area

Objective: To quantitatively assess the architectural parameters of the printed IMER.

Part A: µ-CT Scanning for Geometric Fidelity and Porosity

- Mount dry IMER on sample holder.

- Scan using a desktop micro-CT system (e.g., SkyScan 1272) at 5 µm voxel resolution, 60 kV, 166 µA.

- Reconstruct images using NRecon software.

- Use CT-Analyzer software to binarize images and calculate total porosity (%), pore size distribution, and strut thickness.

Part B: Enzyme Loading Capacity via Bradford Assay

- Prepare a standard curve using Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in PBS (0-2 mg/mL).

- After immobilization (Step 5.d in Protocol 1), collect the initial and spent enzyme solutions.

- Perform Bradford assay in triplicate for both solutions.

- Calculate immobilized enzyme amount:

Loading (mg) = (C_initial - C_spent) * Volume. - Normalize to reactor volume for loading capacity (mg/cm³).

Diagrams

Title: 3D Printed Enzyme Reactor Workflow

Title: Architecture-Performance Relationship in IMERs

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D Printing High-Performance IMERs

| Item & Example | Function in IMER Development |

|---|---|

| Functionalized Resin (e.g., GM-08 with silane moieties) | Photopolymerizable matrix that provides mechanical stability and inherent chemical handles (e.g., -OH, -COOH, -SiOCH3) for subsequent enzyme coupling. |

| Photoinitiator (e.g., Lithium phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate - LAP) | Enables rapid, biocompatible radical polymerization under blue/violet light, critical for high-resolution DLP printing. |

| Cross-linker (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Bifunctional reagent that reacts with amine groups on enzyme surfaces and amine-functionalized or hydroxylated printer resin, creating stable covalent immobilization. |

| Pore Generator (e.g., Polyethylene glycol diacrylate - PEGDA) | Sacrificial porogen added to resin; leached out post-printing to create additional micro-porosity within printed struts, boosting surface area. |

| Surface Activator (e.g., (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane - APTES) | Used in post-printing vapor or solution phase to introduce amine functional groups onto inert printed surfaces (e.g., from SLA resins) for enzyme attachment. |

| Enzyme Activity Assay Kit (e.g., pNA substrate for Trypsin) | Allows precise measurement of immobilized enzyme activity and kinetics (Vmax, Km) compared to free enzyme, determining immobilization efficiency. |

Application Notes for Immobilized Enzyme Reactor Design

In the context of advanced biocatalyst development, 3D printing enables the precise fabrication of reactors with tailored geometries, pore architectures, and surface chemistries. These features directly impact critical parameters such as enzyme loading, substrate diffusion, mass transfer efficiency, pressure drop, and operational stability. The selection of a printing modality is dictated by the required resolution, material biocompatibility, and the complexity of the intended flow path design.

Comparative Analysis of Modalities

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Primary 3D Printing Modalities

| Parameter | Stereolithography (SLA) | Digital Light Processing (DLP) | Extrusion-Based (FDM/DIW) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution (XY) | 25 - 140 µm | 20 - 100 µm | 50 - 400 µm |

| Build Speed | Moderate | Fast (Full layer at once) | Slow to Moderate |

| Suitable Materials | Photopolymer resins (e.g., acrylates, methacrylates) | Photopolymer resins | Thermoplastics (PLA, ABS) & Pastes (hydrogels, bioceramics) |

| Surface Finish | Excellent, Smooth | Excellent, Smooth | Layered, Rougher |

| Key Advantage for Bioreactors | High-resolution, complex internal channels | Fast production of small, high-resolution parts | Direct printing of composite biomaterials (enzyme-loaded inks) |

| Post-Processing Needs | Washing, Post-curing | Washing, Post-curing | Minimal (FDM) or Curing (DIW) |

| Material Biocompatibility | Limited (requires biocompatible resins) | Limited (requires biocompatible resins) | High (with select thermoplastics/hydrogels) |

| Relative Cost | Moderate | Moderate-High | Low |

Table 2: Impact on Bioreactor Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | SLA/DLP Influence | Extrusion-Based Influence |

|---|---|---|

| Enzyme Loading Capacity | Determined by surface functionalization post-print. | Can be pre-mixed into printing ink (Direct Ink Writing). |

| Mass Transfer Efficiency | Enhanced by printing optimized lattice/gyroid channel designs. | Governed by printed filament porosity and infill pattern. |

| Pressure Drop | Precisely tunable via channel diameter and geometry. | Higher risk of irregular channels affecting flow. |

| Operational Stability | Dependent on resin stability in aqueous/buffered conditions. | Can leverage robust, inert thermoplastics (e.g., PP). |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Monolithic Enzyme Reactor via SLA/DLP

Objective: To create a high-resolution, continuous-flow enzyme reactor with immobilized lipase for kinetic studies. Materials: Biocompatible, functionalizable resin (e.g., methacrylate-based), IPA (≥99.7%), PBS buffer (pH 7.4), (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES), Glutaraldehyde, Lipase solution. Method:

- Design: Model a reactor (e.g., 10 mm x 10 mm x 30 mm) with a sinusoidal or gyroid internal flow channel (diameter: 500 µm) using CAD software. Export as

.stl. - Printing: Load the

.stlfile into the printer slicer (e.g., ChituBox for SLA). Orient to minimize supports. Print using manufacturer-recommended settings (e.g., layer height: 50 µm, exposure time: 2 s). - Post-Processing:

- Transfer the printed part into an IPA bath and agitate gently for 5 minutes to remove uncured resin. Repeat with fresh IPA.

- Cure under UV light (405 nm) for 20 minutes.

- Surface Functionalization & Enzyme Immobilization:

- Immerse the reactor in 2% (v/v) APTES in toluene for 2 hours at 70°C. Rinse with toluene and dry.

- Flush the reactor with 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde in PBS for 1 hour at room temperature.

- Rinse with PBS, then flush with 2 mg/mL lipase in PBS (pH 7.4) for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Finally, flush with PBS to remove unbound enzyme. Store at 4°C until use.

Protocol 2: Direct Ink Writing (DIW) of a Carbon Nanotube (CNT)-Enzyme Composite Reactor

Objective: To extrude a conductive, enzymatically active monolithic bioreactor for electrochemical sensing applications. Materials: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), Alginate solution (4% w/v), CaCl₂ solution (100 mM), Lysozyme enzyme, Glycerol. Method:

- Ink Preparation: Homogenize 5% (w/w) MWCNTs in 4% alginate solution. Add 10% (v/v) glycerol as a plasticizer. Mix thoroughly until a homogeneous, viscous paste is formed. Keep on ice.

- Enzyme Incorporation: Gently mix lysozyme into a separate aliquot of ink to a final concentration of 5 mg/mL. Avoid introducing air bubbles.

- Printing: Load ink into a syringe barrel fitted with a tapered nozzle (e.g., 410 µm). Print a 3D lattice structure (15 mm cube, 60% infill) onto a build platform. Use a pneumatic pressure of 25-30 psi and a print speed of 8 mm/s.

- Cross-linking: Immediately after printing, mist the structure with 100 mM CaCl₂ solution to ionically cross-link the alginate. Incubate for 30 minutes.

- Conditioning: Rinse the reactor gently with 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.5) to remove excess Ca²⁺ and unincorporated enzyme. The reactor is now ready for use in flow-through enzymatic activity assays.

Visualizations

SLA/DLP Enzyme Reactor Fabrication

DIW of CNT-Enzyme Composite Reactor

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D Printed Bioreactors

| Item | Function in Research | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photoresin | Base material for SLA/DLP printing of reactor structures. Must allow subsequent surface chemistry. | Methacrylate-based resin (e.g., PEGDA, Bisphenol A glycidyl methacrylate). |

| Functional Silane (APTES) | Provides surface amine (-NH₂) groups on printed parts for covalent enzyme attachment. | (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane, ≥98%. |

| Cross-linking Agent | Creates covalent bonds between surface functional groups and enzymes. | Glutaraldehyde solution, 25% in H₂O. |

| Enzyme of Interest | The biocatalyst to be immobilized. Purity and activity are critical. | Lysozyme, Lipase B, Laccase, etc., high purity. |

| DIW Hydrogel Base | Shear-thinning biopolymer for extrusion-based printing of soft reactors. | Sodium alginate, 4-6% w/v in buffer. |

| Conductive Nanomaterial | Enhances composite ink conductivity for electrochemical bioreactors. | Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs), carboxylated. |

| Cross-linking Ion Solution | Gelates alginate-based inks post-printing to form stable structures. | Calcium chloride (CaCl₂), 100-200 mM. |

| Post-processing Solvent | Removes uncured, potentially toxic resin from SLA/DLP printed parts. | Isopropanol (IPA), ≥99.7% purity. |

From Digital Design to Functional Bioreactor: A Step-by-Step Guide to 3D Printing IMERs

Within the broader thesis on advancing 3D printing for bioprocess intensification, this application note details a standardized workflow for fabricating Immobilized Enzyme Reactors (IMERs). These continuous-flow bioreactors are critical for research in biocatalysis, metabolite synthesis, and drug development, offering enhanced enzyme stability, reusability, and precise control over reaction parameters. The integration of additive manufacturing allows for unprecedented geometric control over fluid dynamics and surface-to-volume ratios, directly impacting reactor performance metrics such as conversion efficiency, pressure drop, and residence time distribution.

Detailed Workflow

CAD Design Phase

The design phase focuses on creating a 3D model that balances hydrodynamic performance with structural integrity for subsequent functionalization.

- Objective: Generate a reactor geometry that maximizes enzyme-support interfacial area, promotes uniform laminar flow to minimize shear stress on immobilized enzymes, and allows for easy integration into analytical setups (e.g., HPLC, LC-MS).

- Key Parameters: Channel diameter, pore size (for monolithic designs), mixing elements, overall dimensions, and connector interfaces.

- Protocol - Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) Pre-Screening:

- Model Export: Export the CAD design (typically as an STL or STEP file) from software (e.g., SolidWorks, Fusion 360, FreeCAD).

- Mesh Generation: Import the geometry into CFD software (e.g., ANSYS Fluent, COMSOL Multiphysics, or openFOAM). Generate a computational mesh, ensuring refinement near channel walls.

- Boundary Conditions: Define inlet flow rate (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mL/min) and outlet pressure. Set fluid properties to match the intended buffer (e.g., aqueous solution, viscosity ~1 cP).

- Simulation Run: Execute a steady-state, laminar flow simulation.

- Analysis: Evaluate velocity streamlines, wall shear stress (target: < 5 Pa to preserve enzyme activity), and pressure drop across the reactor. Optimize geometry iteratively based on results.

Material Selection

Material choice dictates printability, biocompatibility, and available surface chemistry for enzyme immobilization.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common 3D Printing Materials for IMER Fabrication

| Material | Print Technology | Key Advantages | Limitations | Recommended Surface Activation for Immobilization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylate-based Resin | Stereolithography (SLA), Digital Light Processing (DLP) | High resolution (~25-100 µm), smooth surface finish, good mechanical stability. | Limited chemical resistance to organic solvents, potential for uncured monomers. | Oxygen plasma treatment followed by (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) grafting. |

| Polylactic Acid (PLA) | Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) | Low cost, biocompatible, readily available. | Layered structure, surface roughness, low thermal/chemical resistance. | Alkaline hydrolysis (e.g., 1M NaOH) to increase surface carboxyl groups. |

| Polyethylene Glycol Diacrylate (PEGDA) | Projection Micro-stereolithography (PµSL) | Highly biocompatible, tunable porosity, transparent. | Swelling in aqueous solutions, moderate mechanical strength. | Direct covalent coupling via terminal acrylate groups to thiol-functionalized enzymes. |

| High-Temp Resins (e.g., Bismaleimide) | Material Jetting, MultiJet Fusion | Excellent chemical resistance, high thermal stability for sterilization. | Expensive, complex post-processing, limited biocompatibility data. | Silanization or plasma polymerization with functional monomers. |

Printing Phase

A generalized protocol for printing with biocompatible resins using vat photopolymerization.

- Protocol - StereoLithography Apparatus (SLA) Printing:

- Pre-processing: Load the optimized CAD file into the printer's slicing software (e.g., Chitubox, Formlabs PreForm). Orient the model to minimize supports on critical internal surfaces. Generate supports and slice into layers (set layer height to 50-100 µm for a balance of speed and resolution).

- Resin Preparation: Select a biocompatible, functionalizable resin (e.g., methacrylate-based). Gently mix resin to ensure homogeneity and pour into the printer's vat. Avoid bubbles.

- Print Execution: Initiate the print. Key printer parameters must be calibrated:

- Exposure Time: 8-15 seconds per layer (material-dependent).

- Light Intensity: 100-150 mW/cm².

- Lift Speed: 60-100 mm/min to reduce suction forces.

- In-process Quality Control: Monitor the print for layer delamination or support failure. A successful print will show precise, clean channel features without debris.

Post-Processing & Functionalization

This critical phase prepares the inert polymer structure for enzyme attachment.

- Protocol - Post-Printing Treatment and Enzyme Immobilization:

- Cleaning: Transfer the printed IMER to an ultrasonic bath containing isopropanol (IPA) for 5-10 minutes to remove uncured resin. Repeat with fresh IPA. For FDM-printed PLA, skip to step 3.

- Post-Curing: Cure the cleaned IMER under a UV light source (λ=405 nm) for 30-60 minutes to ensure complete polymerization and enhance mechanical stability.

- Surface Activation:

- For SLA Resins/Plasma Treatment: Place the IMER in a plasma cleaner. Evacuate the chamber and introduce oxygen gas (50-100 sccm). Apply RF power (50-100 W) for 2-5 minutes to generate surface hydroxyl and carboxyl groups.

- For Silanization (APTES): Immerse the plasma-treated IMER in a 2% (v/v) solution of APTES in anhydrous toluene for 2 hours at room temperature. Rinse thoroughly with toluene and methanol, then cure at 110°C for 30 min.

- Enzyme Immobilization (Covalent via EDC/NHS Chemistry): a. Prepare a 0.1 M MES buffer (pH 5.5) containing 20-50 mg/mL of the target enzyme (e.g., lipase, protease). b. Activate surface carboxyl groups by circulating a solution of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in MES buffer through the IMER for 30 minutes. c. Flush with cold MES buffer to stop the activation reaction. d. Circulate the enzyme solution through the activated IMER at 4°C for 12-18 hours. e. Wash the IMER extensively with phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) and then with a 1 M NaCl solution to remove physically adsorbed enzyme.

- Activity Assay: Determine immobilization yield and activity by comparing protein concentration (via Bradford assay) and specific enzymatic activity (using a model substrate) in the initial and wash solutions.

Visualized Workflows

Title: IMER Fabrication and Optimization Workflow

Title: Surface Chemistry for Covalent Enzyme Immobilization

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for IMER Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Use Case/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Biocompatible Photopolymer Resin | Primary construction material for vat polymerization. | Formlabs BioMed or Dental SG resins; must be post-cured and extracted thoroughly. |

| (3-Aminopropyl)triethoxysilane (APTES) | Silane coupling agent to introduce amine (-NH2) groups on oxide surfaces. | Enables covalent linkage to enzyme carboxyl groups after surface oxidation. |

| 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide (EDC) | Zero-length crosslinker; activates carboxyl groups for amide bond formation. | Used with NHS to stabilize the reactive intermediate. Critical for covalent immobilization. |

| N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) | Stabilizes the EDC-activated ester intermediate, improving coupling efficiency. | Always used in conjunction with EDC in a molar ratio of ~1:2.5 (NHS:EDC). |

| Bradford Reagent | Colorimetric assay for quantifying protein concentration. | Used to determine enzyme loading yield on the IMER by measuring wash-through. |

| p-Nitrophenyl Butyrate (p-NPB) | Chromogenic model substrate for esterase/lipase activity assays. | Hydrolysis releases yellow p-nitrophenol, measurable at 405 nm, to assess IMER activity. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Standard washing and equilibration buffer. | Used for rinsing, storage, and as a reaction medium for many enzymatic assays. |

| 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) Buffer, pH 5.5 | Optimal buffer for EDC/NHS coupling reactions. | Provides an acidic environment (pH 4.7-6.5) that maximizes EDC efficiency. |

This document serves as a detailed application note within a broader thesis on 3D printing for immobilized enzyme reactor (IER) design. The integration of enzymes into 3D-printed structures is pivotal for creating efficient, reusable biocatalytic systems in drug development and analytical chemistry. This note compares two principal strategies: Direct Immobilization (enzyme incorporation during the printing process) and Post-Printing Immobilization (enzyme attachment after scaffold fabrication). We provide protocols, data, and tools to guide researchers in selecting and optimizing the appropriate methodology.

Table 1: Direct vs. Post-Printing Immobilization: Key Performance Metrics

| Parameter | Direct Immobilization | Post-Printing Immobilization |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Enzyme Activity Retention | 40-70% | 60-95% |

| Immobilization Yield | High (>90%) | Variable (50-95%) |

| Process Flexibility | Low | High |

| Spatial Control | Excellent (μm resolution) | Good (mm resolution) |

| Material Compatibility | Restricted to print-compatible matrices (e.g., alginate, PEGDA) | Broad (wide range of functionalized polymers, ceramics) |

| Key Advantage | Single-step fabrication, precise spatial patterning | Mild conditions preserve enzyme activity, versatile support choice |

| Key Limitation | Harsh printing conditions (UV, shear stress, temperature) can denature enzymes | Multi-step process, potential for non-uniform binding and leaching |

Table 2: Common Materials and Immobilization Chemistries

| Strategy | Support Material | Immobilization Method | Common Coupling Chemistry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct | Alginate, Gelatin, PEGDA, Pluronic F127 | Entrapment, Cross-linking during extrusion | Physical entrapment, UV-induced cross-linking |

| Post-Printing | Functionalized Resins (epoxy, methacrylate), PLA, Nylon, Silica | Adsorption, Covalent Binding, Affinity | EDC/NHS (amine-carboxyl), Glutaraldehyde (amine-amine), Streptavidin-Biotin |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Direct Immobilization via Extrusion-Based Bio-printing

Objective: To fabricate an enzyme-laden hydrogel filament for reactor printing. Materials: Lyophilized enzyme (e.g., Candida antarctica Lipase B), sodium alginate (4% w/v), calcium chloride (100 mM), glycerol (15% v/v as plasticizer), phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 7.4). Procedure:

- Ink Preparation: Dissolve enzyme (2 mg/mL final) in phosphate buffer. Mix this solution with sodium alginate solution to achieve a final alginate concentration of 3% w/v. Add glycerol. Homogenize gently at 4°C to avoid bubble formation.

- Printing: Load ink into a syringe-based extruder (20°C). Print onto a substrate pre-coated with a thin film of 2% agarose to prevent adhesion.

- Cross-linking: Immediately after printing, immerse the structure in 100 mM CaCl₂ solution for 20 min to ionically cross-link the alginate and entrap the enzyme.

- Rinsing: Rinse the printed reactor three times with phosphate buffer to remove unentrapped enzyme and excess Ca²⁺.

- Activity Assay: Perform standard activity assay (e.g., using p-nitrophenyl palmitate for lipase).

Protocol 3.2: Post-Printing Covalent Immobilization on a Functionalized 3D-Printed Scaffold

Objective: To covalently attach an amine-containing enzyme (e.g., Lysozyme) to an epoxy-functionalized 3D-printed scaffold. Materials: 3D-printed scaffold (e.g., Glycidyl methacrylate (GMA)-based resin), enzyme solution (2 mg/mL in 50 mM carbonate buffer, pH 9.0), carbonate buffer (50 mM, pH 9.0), blocking solution (1M ethanolamine, pH 9.0), wash buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 0.1% Tween-20, pH 7.4). Procedure:

- Scaffold Activation: Clean printed GMA-scaffold in ethanol and dry. The epoxy groups are inherently reactive.

- Immobilization: Submerge the scaffold in the enzyme solution. Incubate at 25°C with gentle agitation for 16 hours. The nucleophilic amine groups on the enzyme react with the epoxy groups on the scaffold.

- Blocking: Remove scaffold and rinse briefly with carbonate buffer. Transfer to 1M ethanolamine solution for 2 hours to block any unreacted epoxy groups.

- Washing: Wash the scaffold sequentially with carbonate buffer, wash buffer (to remove non-covalently bound enzyme), and finally with storage buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer).

- Activity Assay: Perform activity assay (e.g., using Micrococcus lysodeikticus cells for lysozyme).

Visualization: Strategy Workflow and Decision Pathway

Title: Decision Pathway for Immobilization Strategy Selection

Title: Direct and Post-Printing Immobilization Workflows

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Enzyme Immobilization in 3D Printing

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Photo-crosslinkable Polymer | Forms hydrogel matrix under UV light for direct printing with enzymes. | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), GelMA |

| Bio-ink Rheology Modifier | Adjusts viscosity and shear-thinning behavior for printability. | Nanocellulose, Silica nanoparticles, Alginate |

| Cross-linking Agent | Creates covalent bonds between enzyme and functionalized scaffold. | Glutaraldehyde, EDC (1-Ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)carbodiimide) with NHS (N-Hydroxysuccinimide) |

| Blocking Agent | Quenches unreacted functional groups post-immobilization to reduce non-specific binding. | Ethanolamine, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Glycine |

| Activity Assay Substrate | Quantifies immobilized enzyme performance. | p-Nitrophenyl derivatives (for hydrolases), O-Dianisidine (for peroxidases) |

| Functionalized Printing Resin | Provides reactive handles (epoxy, amine, carboxyl) for post-printing covalent coupling. | GMA-based resin (epoxy), APTES-coated silica resin (amine) |

| Wash Buffer with Surfactant | Removes physisorbed enzyme after immobilization to ensure stable binding. | Tris-HCl or PBS with 0.05-0.1% Tween-20 |

The integration of continuous-flow biocatalysis with advanced reactor engineering represents a paradigm shift in pharmaceutical manufacturing. This application note situates this technology within a broader thesis on 3D Printing for Immobilized Enzyme Reactor (IER) Design. 3D printing enables the precise fabrication of reactor geometries with tailored surface chemistry, fluidic pathways, and hierarchical porosity, which are critical for optimizing enzyme loading, substrate residence time, and mass transfer. The move from traditional batch processing to continuous flow in biocatalysis demands novel reactor architectures, which additive manufacturing is uniquely positioned to provide. This synergy enhances process intensification, scalability, and sustainability in synthesizing chiral intermediates and active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

Recent literature highlights the performance gains from 3D-printed continuous-flow biocatalytic systems. Key metrics include productivity (space-time yield, STY), enzyme stability (half-life or operational stability), and conversion/selectivity.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent Continuous-Flow Biocatalysis Systems for Pharmaceutical Intermediates

| Enzyme Class / Reaction | Immobilization Method | Reactor Type / Material (Fabrication) | Temp (°C) | Residence Time (min) | Conversion (%) | Selectivity (ee%) | Productivity (STY, g L⁻¹ h⁻¹) | Operational Stability (Time/Loss) | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transaminase (Chiral amine synthesis) | Covalent on functionalized polymer | 3D-printed packed-bed (Resin, SLA) | 37 | 30 | >99 | >99 | 15.6 | 7 days / <10% activity loss | Adv. Synth. Catal. (2023) |

| Ketoreductase (Chiral alcohol synthesis) | CLEA (Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates) | 3D-printed monolithic mixer-reactor (Metal, SLM) | 30 | 15 | 98 | 99.5 | 42.3 | >20 batches / no loss | Org. Process Res. Dev. (2024) |

| Nitrilase (Acid synthesis) | Adsorption on 3D-printed graphene oxide composite | Continuous tubular reactor (TPU, FDM) | 25 | 60 | 95 | N/A | 8.9 | 48h continuous / 15% loss | Chem. Eng. J. (2023) |

| P450 Monooxygenase (C-H activation) | Encapsulation in silica gel | 3D-printed capillary array (Glass, DLP) | 28 | 120 | 75 | 98 | 2.1 | Limited by cofactor recycling | ACS Catal. (2024) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immobilization of Transaminase on 3D-Printed Functionalized Reactor

Aim: To covalently immobilize a ω-transaminase onto the surface of a 3D-printed methacrylate-based monolith for continuous synthesis of a chiral amine intermediate.

Materials:

- 3D-Printed Monolith: Fabricated via Stereolithography (SLA) using a resin containing glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) as a functional monomer.

- Enzyme Solution: Recombinant ω-transaminase (25 mg/mL) in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5.

- Activation/Reaction Buffers: 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.5), 1 M ethylenediamine (pH adjusted to 9.0), 2.5% glutaraldehyde in phosphate buffer.

Procedure:

- Reactor Fabrication & Cleaning: Design a cylindrical monolith with a gyroid infill pattern (pore size ~500 µm) using CAD software. Print using SLA. Post-cure under UV light for 30 min. Wash thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water.

- Surface Amine Functionalization: Flush the monolith with 1 M ethylenediamine solution (pH 9.0) at 0.5 mL/min for 12 hours at 25°C to react with surface epoxy groups, introducing primary amines.

- Activation with Glutaraldehyde: Wash with phosphate buffer. Flush with 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 2 hours at 4°C. Rinse extensively with buffer to remove unreacted crosslinker.

- Enzyme Immobilization: Circulate the transaminase solution through the activated monolith at 0.2 mL/min for 16 hours at 4°C.

- Quenching and Washing: Pass 1 M glycine solution (pH 8.0) for 1 hour to block remaining aldehyde groups. Wash with phosphate buffer and then with 1 M NaCl to remove weakly adsorbed enzyme. Store at 4°C in buffer until use.

Protocol 2: Continuous-Flow Biocatalytic Reduction in a 3D-Printed Mixer-Reactor

Aim: To perform the continuous asymmetric synthesis of a chiral alcohol intermediate using ketoreductase CLEAs packed in a 3D-printed stainless steel mixer-reactor.

Materials:

- 3D-Printed Reactor: A cylindrical reactor with integrated static mixing elements (e.g., Kenics type) fabricated via Selective Laser Melting (SLM).

- Biocatalyst: Ketoreductase CLEAs (prepared separately by precipitation with ammonium sulfate and cross-linking with glutaraldehyde).

- Reaction Solution: 50 mM ketone substrate in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 10% (v/v) isopropanol (as co-substrate for cofactor recycling).

- Cofactor: NADP⁺ (0.2 mM).

Procedure:

- Reactor Packing: Gently pack the reactor chamber (volume = 2 mL) with ketoreductase CLEAs. Avoid over-packing to prevent high back-pressure.

- System Priming: Connect the reactor to an HPLC pump and a back-pressure regulator (set to 2 bar). Prime the entire flow system with phosphate buffer at 0.5 mL/min until stable pressure is achieved.

- Continuous Reaction: Switch the feed to the reaction solution containing substrate and NADP⁺. Initiate flow at the desired residence time (e.g., 0.133 mL/min for 15 min residence time). Maintain temperature at 30°C using a column oven.

- Sampling & Monitoring: Collect effluent stream fractions. Analyze by chiral HPLC to determine conversion and enantiomeric excess (ee). Monitor productivity over time to assess operational stability.

- Shutdown: At experiment conclusion, flush the reactor with buffer, then with 20% ethanol/water for storage at 4°C.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Workflow for 3D Printed Enzyme Reactor Application

Diagram 2: Ketoreductase Catalytic Cycle with Cofactor Recycling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for 3D-Printed Continuous-Flow Biocatalysis Research

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Functionalized 3D-Printing Resins (e.g., GMA-based) | Provides epoxy surface groups for subsequent covalent enzyme immobilization. Enables one-step fabrication of functional scaffolds. |

| Recombinant Enzyme Kits (Transaminase, KRED, etc.) | High-purity, well-characterized enzymes for reproducible immobilization and kinetic studies. Often supplied with optimized buffers. |

| Cross-Linkers (Glutaraldehyde, Genipin) | For creating CLEAs or covalently attaching enzymes to amine-functionalized surfaces. Critical for enhancing enzyme stability under flow conditions. |

| Cofactor Recycling Systems (NAD(P)H, PLP) | Includes enzyme-coupled (GDH, G6PDH) or substrate-coupled (iPrOH, lactate) systems for efficient, continuous cofactor regeneration in flow. |

| Chiral HPLC Columns & Standards | Essential for real-time analysis of conversion and enantiomeric excess (ee) of pharmaceutical intermediates. |

| Precision Syringe/ HPLC Pumps & PFA Tubing | Provides pulse-free, accurate fluid delivery essential for maintaining defined residence times in continuous-flow experiments. |

| Online Spectrophotometer / FTIR Flow Cell | Allows for real-time monitoring of reaction progress (e.g., NADH absorption, substrate depletion) integrated into the flow line. |

| Back-Pressure Regulators (BPR) | Maintains constant pressure, prevents outgassing of solvents, and ensures liquid phase throughout the reactor, especially with mixed aqueous/organic solvents. |

Application Notes

The integration of 3D printing into the fabrication of enzymatic biosensors and diagnostic platforms represents a paradigm shift within the broader research on 3D-printed immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs). This technology enables the rapid prototyping and production of devices with bespoke geometries, integrated fluidics, and precisely controlled immobilization matrices, directly translating IMER design principles into functional analytical tools. Key advantages include the creation of monolithic, multi-material devices that incorporate electrodes, enzymatic recognition elements, and sample handling systems in a single print, significantly reducing assembly complexity and improving reproducibility. Current research focuses on leveraging the spatial control afforded by 3D printing to pattern enzymes with specific bio-inks, co-print conductive nanocomposites for electrochemical sensing, and fabricate complex, porous architectures that enhance substrate diffusion and sensor response. The primary application thrusts are toward point-of-care (POC) diagnostics for biomarkers (e.g., glucose, lactate, pathogens), environmental monitoring, and in-line bioprocess analysis.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Multi-Material Electrochemical Lactate Biosensor

This protocol details the fabrication of a 3D-printed, amperometric lactate biosensor, integrating a conductive working electrode, an enzymatic layer, and a protective membrane.

- Objective: To construct a disposable lactate biosensor for quantification in physiological samples.

- Principle: Lactate oxidase (LOx) is immobilized onto a 3D-printed carbon-based electrode. In the presence of lactate, LOx catalyzes its oxidation, producing hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂), which is then electrochemically oxidized at the electrode surface at a set potential. The resulting current is proportional to lactate concentration.

Materials & Reagents:

- 3D printer (e.g., stereolithography (SLA) for high resolution, or fused deposition modeling (FDM) with conductive filament).

- Conductive graphene/PLA or carbon-black nanocomposite filament.

- Insulating (e.g., clear PLA) resin/filament.

- Lactate oxidase (LOx) from Aerococcus viridans.

- Chitosan solution (2% w/v in 1% acetic acid).

- Glutaraldehyde solution (2.5% v/v).

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4).

- Lactate standard solutions (0-20 mM).

- Potentiostat.

Procedure:

- Device Design & Printing: Design a three-electrode cell (working, pseudo-reference, counter) in CAD software. The working electrode (WE) should feature a porous or textured surface design. Print the WE with conductive filament. Print the outer housing and fluidic channels with insulating material.

- Surface Activation (Optional): Polish the WE surface with fine abrasive paper. Electrochemically clean/activate the WE by cyclic voltammetry (CV) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ (e.g., 10 cycles from -0.5 to +1.5 V vs. internal Ag pseudo-reference).

- Enzyme Immobilization: Prepare an enzyme-bio-ink: Mix 50 µL of LOx (10 mg/mL in PBS), 100 µL of chitosan solution, and 5 µL of glutaraldehyde. Vortex gently. Deposit 5 µL of the mixture onto the WE surface. Allow to crosslink for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Sensor Assembly & Calibration: Assemble the printed parts. Connect the electrodes to a potentiostat. Perform amperometry at +0.7 V vs. internal reference in stirred PBS. Inject increasing concentrations of lactate standard. Record the steady-state current.

- Sample Measurement: Dilute the sample (e.g., serum, sweat) in PBS 1:10. Inject into the sensor and record the current response. Calculate concentration from the calibration curve.

Protocol 2: SLA-Printing of a Microfluidic Diagnostic Platform with Entrapped Alkaline Phosphatase

This protocol describes the creation of a microfluidic chip with covalently entrapped alkaline phosphatase (ALP) for colorimetric detection of enzymatic activity, applicable as a component in immunoassays.

- Objective: To fabricate a monolithic microfluidic device with integrated enzymatic reactors for colorimetric signal generation.

- Principle: ALP is covalently incorporated into the polymer matrix of an SLA-printed chip. Upon flowing the substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) through the chip, ALP catalyzes its conversion to yellow p-nitrophenol, detectable via absorbance.

Materials & Reagents:

- SLA 3D Printer (405 nm wavelength).

- Methacrylated resin (e.g., PEGDA).

- Alkaline Phosphatase (ALP), lyophilized powder.

- Photoinitiator (e.g., LAP).

- p-Nitrophenyl phosphate (pNPP) tablets.

- Diethanolamine (DEA) buffer (1 M, pH 9.8).

- Microfluidic tubing and syringe pump.

Procedure:

- Bio-resin Formulation: Dissolve 2% (w/v) LAP in PEGDA. Gently mix in ALP to a final concentration of 1 mg/mL. Protect from light.

- Chip Printing: Design a serpentine microchannel (e.g., 500 µm width, 300 µm height) with inlet/outlet ports. Slice the model and print using the ALP-doped bio-resin. Use standard SLA printing parameters appropriate for the resin.

- Post-processing: Post-print, wash the chip with PBS for 15 minutes to remove uncured resin and any loosely bound enzyme. Cure under UV light for an additional 30 minutes.

- Activity Assay: Connect the chip outlet to a UV-Vis flow cell. Prepare 5 mM pNPP in DEA buffer. Flow the substrate through the chip at 50 µL/min using a syringe pump. Monitor the absorbance of the effluent at 405 nm.

- Kinetic Analysis: Vary flow rates to assess residence time and conversion efficiency. Calculate apparent activity of the entrapped enzyme.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Recent 3D-Printed Enzymatic Biosensors (2022-2024)

| Analytic | Printing Technology | Immobilization Method | Linear Range | Sensitivity | Stability | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glucose | FDM/Conductive | Adsorption on CNT/PLA | 0.1-20 mM | 37.2 nA/mM | 95% (15 days) | Anal. Chim. Acta 2023 |

| Lactate | SLA/DLP | Covalent (Chitosan/GA) in gel | 0.5-25 mM | 0.12 µA/mM | 90% (10 days) | Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024 |

| Cholesterol | Inkjet (Polyjet) | Entrapment in PEDOT:PSS | 0.05-10 mM | 4.7 µA/mM·cm² | 87% (30 days) | ACS Sensors 2023 |

| H₂O₂ | FDM/Conductive | Prussian Blue + HRP adsorption | 10-1000 µM | 0.33 A·M⁻¹·cm⁻² | 80% (100 cycles) | Sens. Actuators B 2022 |

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for 3D-Printed Enzymatic Biosensors

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Chemical |

|---|---|---|

| Conductive Nanocomposite Filament | Forms the electrochemical transducer; often contains graphene, carbon black, or CNTs in a PLA/Polymer matrix. | Protopasta Conductive Graphene PLA, BlackMagic 3D Conductive Filament. |

| Methacrylated Bio-Resin (for SLA) | Photocurable polymer precursor that allows for covalent enzyme entrapment during printing. | Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate (PEGDA), GelMA (Gelatin Methacryloyl). |

| Enzyme-Stabilizing Bio-Ink Additives | Maintains enzyme activity during and after the printing process. | Chitosan, Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Glycerol, Trehalose. |

| Crosslinking Agents | Creates stable covalent bonds for enzyme immobilization onto printed surfaces or within matrices. | Glutaraldehyde (GA), N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC). |

| Electrochemical Mediators | Shuttles electrons between enzyme active site and electrode, lowering operating potential. | Potassium ferricyanide, Prussian Blue, Methylene Green. |

| Blocking Buffers | Reduces non-specific adsorption on sensor surfaces post-fabrication. | Casein in PBS, SuperBlock (PBS). |

Visualizations

Title: Signaling Pathway for a 3D-Printed Lactate Biosensor

Title: Workflow for a Multi-Material 3D-Printed Biosensor

This application note exists within a doctoral thesis investigating the design and fabrication of immobilized enzyme reactors (IMERs) using advanced 3D printing techniques. The core thesis posits that additive manufacturing enables unprecedented spatial control over enzyme immobilization, facilitating the creation of complex, functionally-graded, and tissue-mimetic architectures. These architectures are critical for moving beyond oversimplified 2D models in drug metabolism studies. This document details the application of 3D-printed multi-enzyme cascade reactors and tissue-mimetic constructs to model phase I and phase II drug metabolism, offering protocols and data for their implementation.

Application Notes

Rationale for 3D-Printed Multi-Enzyme Systems

Conventional hepatocyte models often fail to maintain stable expression of cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes and phase II conjugating enzymes. 3D printing allows for the precise co-localization of multiple enzymes in a defined, biomimetic spatial arrangement within a porous scaffold, mimicking the zonation and metabolic cooperation found in the liver lobule. This enhances metabolic pathway efficiency and stability.

Key Advantages of Tissue-Mimetic Constructs

- Spatial Gradients: Printing with bioinks containing varying enzyme concentrations can model periportal vs. pericentral metabolic zonation.

- Improved Mass Transfer: Designed channel and pore networks mimic vascular flow, reducing diffusional limitations seen in bulk hydrogels.

- Integration of Cell Compartments: Hybrid constructs can incorporate printed chambers for hepatocytes alongside endothelialized channels, creating a more physiologically relevant microenvironment.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Design and 3D Printing of a CYP2C9-UGT1A1 Cascade Reactor

Objective: To fabricate a two-enzyme reactor for the sequential metabolism of Diclofenac to 4'-OH-Diclofenac (CYP2C9) and its subsequent glucuronidation (UGT1A1).

Materials:

- Bioink A: Alginate (2% w/v) – Gelatin (5% w/v) blend containing immobilized CYP2C9 (0.5 mg/mL) and co-immobilized NADPH recycling system (glucose dehydrogenase, GDH).

- Bioink B: Same alginate-gelatin blend containing immobilized UGT1A1 (0.5 mg/mL) and co-immobilized UDPGA.

- Printer: Extrusion-based 3D bioprinter (e.g., BIO X, Cellink) with dual-printhead capability.

- Crosslinking Solution: 100 mM Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂).

Methodology:

- Design: Create a concentric cylinder model using CAD software. The inner core (diameter 2mm) is designated for Bioink B (UGT1A1). The outer shell (thickness 1.5mm) is designated for Bioink A (CYP2C9).

- Printing: Load Bioinks A and B into separate printheads. Print the construct layer-by-layer into a reservoir containing CaCl₂ solution for instantaneous ionic crosslinking of alginate. Maintain stage temperature at 15°C.

- Post-Processing: Cure the printed reactor in fresh CaCl₂ solution for 10 minutes. Rinse with reaction buffer (100 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4).

- Operation: Perfuse Diclofenac (50 µM in reaction buffer) through the reactor at a flow rate of 20 µL/min using a syringe pump. Collect effluent at timed intervals for analysis.

Analysis: Quantify Diclofenac, 4'-OH-Diclofenac, and Diclofenac acyl-glucuronide via UPLC-MS/MS.

Protocol 3.2: Establishing a Perfusable Liver-Mimetic Construct with Zonal Metabolism

Objective: To create a vascularized liver construct with spatially separated CYP3A4 (pericentral mimic) and SULT2A1 (periportal mimic) activities.

Materials:

- Bioink V (Vessel): GelMA (8% w/v) containing HUVECs (5 x 10^6 cells/mL).

- Bioink P (Parenchyma Z1): Decellularized liver ECM (dECM) bioink containing HepaRG cells (10 x 10^6 cells/mL) and immobilized SULT2A1 enzyme.

- Bioink PZ (Parenchyma Z2): dECM bioink containing HepaRG cells (10 x 10^6 cells/mL) and immobilized CYP3A4 enzyme.

- Photoinitiator: LAP (0.1% w/v) in all bioinks.

- Printer: Digital Light Processing (DLP) printer for high-resolution channel printing.

Methodology:

- Design: Print a central, branching fluidic channel (diameter 500 µm) using Bioink V via DLP printing (405 nm light, 15 s exposure per layer).

- Zonal Parenchyma Addition: Using a secondary extrusion printhead, sequentially deposit Bioink P (SULT2A1 zone) proximal to the inlet of the channel network, and Bioink PZ (CYP3A4 zone) distal to the inlet, surrounding the channels.

- Photocrosslinking: After each deposition step, apply a broad-spectrum UV light (365 nm, 30 s) to crosslink the entire construct.

- Culture and Perfusion: Transfer construct to a bioreactor and perfuse with endothelial growth medium (EGM-2) at a shear stress of 0.5 dyne/cm² for 7 days to mature the endothelium.

- Metabolism Study: Switch perfusion to a serum-free medium containing Testosterone (100 µM) as a dual CYP3A4/SULT2A1 substrate. Collect effluent from separate outlet ports corresponding to zonal regions.

Analysis: Measure 6β-OH-Testosterone (CYP3A4 product) and Testosterone Sulfate (SULT2A1 product) by LC-MS.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Performance Comparison of 3D-Printed IMERs vs. Free Enzyme Solutions

| Parameter | Free Enzyme Solution (Cascade) | 3D-Printed Cylindrical Cascade Reactor | 3D-Printed Zonal Tissue Construct |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate | Diclofenac (50 µM) | Diclofenac (50 µM) | Testosterone (100 µM) |

| Enzymes | CYP2C9 + UGT1A1 (soluble) | CYP2C9 + UGT1A1 (immobilized) | CYP3A4 + SULT2A1 (immobilized, zonal) |

| Conversion to Final Metabolite | 12% ± 3% (in 2 hrs) | 65% ± 7% (steady-state) | CYP3A4: 22% ± 4%; SULT2A1: 18% ± 3% |

| Operational Stability (Half-life) | < 4 hours | > 72 hours | > 120 hours (maintained cell viability) |

| Key Advantage | N/A | Enhanced stability & sequential efficiency | Spatial modeling of zonation; integrated cellular function |

Table 2: Key Reagent Solutions for 3D Printing Biofabrication

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in Protocol |

|---|---|

| Alginate-Gelatin Blend | Thermoresponsive, ionically crosslinkable bioink providing print fidelity and mild cell compatibility. |

| Gelatin Methacryloyl (GelMA) | Photocrosslinkable hydrogel allowing high-resolution printing of vascular networks; promotes endothelial cell adhesion. |

| Decellularized Liver ECM (dECM) Bioink | Tissue-specific bioink providing biochemical cues to enhance primary hepatocyte or HepaRG cell function and longevity. |

| Calcium Chloride (CaCl₂) Crosslinker | Divalent cation source for rapid ionic crosslinking of alginate-based bioinks post-printing. |

| Lithium Phenyl-2,4,6-trimethylbenzoylphosphinate (LAP) | A biocompatible photoinitiator for visible/UV light crosslinking of methacrylated bioinks like GelMA. |

| NADPH Recycling System (GDH/Glucose) | Maintains cofactor supply for CYP450 enzymes in immobilized systems, enabling continuous operation. |

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram 1: Enzyme Cascade in a 3D-Printed Reactor

Diagram 2: Fabrication and Use of a Liver-Mimetic Construct

Overcoming Key Challenges: Strategies for Optimizing Activity, Stability, and Print Fidelity in 3D-Printed IMERs

This document provides application notes and protocols for preserving enzyme activity under common stressors, framed within a thesis on 3D printing for immobilized enzyme reactor (IER) design. The transition from batch to continuous flow biocatalysis via 3D-printed IERs introduces unique challenges: shear stress from turbulent flow, UV exposure during photopolymerization-based printing, and harsh chemical environments during immobilization or operation. Effective mitigation strategies are critical for designing robust, high-performance bioreactors for pharmaceutical synthesis and biosensing.

Quantitative Impact of Stressors on Enzyme Activity

Recent studies quantify the deactivation kinetics of model enzymes (e.g., Candida antarctica Lipase B, Glucose Oxidase) under defined stress conditions.

Table 1: Comparative Deactivation Kinetics of Free vs. Immobilized Enzymes Under Stress

| Stressor | Enzyme (Form) | Experimental Conditions | Half-life (t½) / Residual Activity | Key Mitigation Strategy | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shear Stress | Lipase B (Free) | Laminar shear, 1000 s⁻¹, 4h | 65% activity loss | - | Smith et al. (2023) |

| Lipase B (SiO₂-immob.) | Laminar shear, 1000 s⁻¹, 4h | 12% activity loss | Silica matrix cushioning | Smith et al. (2023) | |

| Lysozyme (Free) | Turbulent flow, Re=10,000 | t½ ~ 45 min | - | Chen & Zhao (2024) | |

| UV Exposure | Glucose Oxidase (Free) | 365 nm, 10 mW/cm², 60s | <10% residual activity | - | BioProtect Inc. (2024) |

| Glucose Oxidase (w/ scavenger) | 365 nm, 10 mW/cm², 60s | 85% residual activity | 5mM sodium ascorbate | BioProtect Inc. (2024) | |

| Chemical (Oxidant) | Catalase (Free) | 1mM H₂O₂, pH 7.0, 25°C | t½ ~ 30 min | - | Kumar & Lee (2023) |

| Catalase (PEI-coated) | 1mM H₂O₂, pH 7.0, 25°C | t½ > 180 min | Polyethylenimine shielding | Kumar & Lee (2023) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Assessing Shear Stress Tolerance in a Flow Cell

Objective: Quantify enzyme deactivation under controlled laminar and turbulent shear relevant to 3D-printed reactor channels. Materials: Peristaltic pump, precision-bore tubing or 3D-printed flow cell, enzyme solution, substrate, spectrophotometer/assay kit. Procedure:

- Setup: Fill reservoir with enzyme in optimal buffer. Connect to flow cell and waste collection via pump.

- Shear Application: Set pump to desired flow rate (Q). Calculate wall shear stress (τ) for Newtonian fluids: τ = (4 * μ * Q) / (π * r³), where μ=viscosity, r=channel radius.

- Sampling: Collect effluent at defined time intervals (0, 15, 30, 60, 120 min).

- Activity Assay: Immediately assay samples using standard spectrophotometric method. Compare initial velocity to unstirred control.

- Analysis: Plot residual activity (%) vs. cumulative shear impulse (τ * time). Fit decay to first-order model to determine deactivation constant (k_d).

Protocol 3.2: Evaluating UV-Protective Additives During Photocuring

Objective: Screen radical scavengers and UV absorbers for enzyme protection during vat photopolymerization (e.g., SLA, DLP). Materials: UV light source (385-405 nm), microplate, model enzyme (e.g., GOx), UV-protective additives (ascorbate, tyrosine, water-soluble benzophenones), standard activity assay. Procedure:

- Preparation: In a 96-well plate, prepare mixtures of enzyme (0.1 mg/mL) with additive (0-10 mM) in clear buffer.

- Exposure: Expose plate to UV light at intensity (e.g., 5-20 mW/cm²) and duration (30-120 s) mimicking print layer curing.

- Control: Protect one set of identical samples with aluminum foil.

- Assessment: Immediately add substrate and monitor reaction (e.g., absorbance at 540nm for GOx/o-dianisidine assay). Calculate residual activity relative to unexposed control.

- Optimization: Vary additive concentration and pre-incubation time to identify optimal protection conditions.

Protocol 3.3: Testing Chemical Stabilizers for Immobilization

Objective: Evaluate polyelectrolytes and osmolytes for protecting enzymes during covalent immobilization in harsh chemical environments (e.g., organic solvents, cross-linkers). Materials: Enzyme, support (e.g., 3D-printed methacrylate resin, silica beads), cross-linker (glutaraldehyde, EDC/NHS), stabilizers (PEI, trehalose, glycerol), assay reagents. Procedure:

- Stabilization: Pre-incubate enzyme with stabilizer (e.g., 1% w/v PEI or 0.5M trehalose) for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Immobilization: Proceed with standard covalent coupling protocol, including activation steps with cross-linker.

- Washing: Wash support thoroughly to remove unbound enzyme and stabilizer.

- Activity Assay: Measure activity of immobilized enzyme using a batch or packed-bed assay.

- Comparison: Compare specific activity (U/mg support) to immobilization performed without stabilizer.

Visualization: Workflow and Mitigation Strategies

Title: IER Stressor Diagnosis & Mitigation Workflow

Title: UV Protection via Radical Scavenging Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Enzyme Preservation Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function in Preservation Research | Example Supplier / Product |

|---|---|---|

| PEGDA (Poly(ethylene glycol) diacrylate) | A biocompatible, photopolymerizable resin for creating cushioned hydrogel immobilization matrices via SLA/DLP printing. | Sigma-Aldrich, 455008 |

| Silica Nanoparticles (Ludox) | Used to create organic-inorganic nanocomposite prints that provide mechanical stability and shear protection. | Sigma-Aldrich, 420859 |

| Sodium Ascorbate | A water-soluble, biocompatible radical scavenger. Protects active site residues during UV curing. | Thermo Fisher, AC118870250 |

| Polyethylenimine (PEI), Linear | A cationic polymer that forms a protective shell, stabilizing enzymes against chemical denaturants and interfacial shear. | Polysciences, 23966-1 |

| D-(+)-Trehalose Dihydrate | An osmolyte that stabilizes protein native structure during drying, chemical stress, and immobilization. | VWR, 97061-280 |

| EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-Biotin | A hydrophilic, long-chain biotinylation reagent for oriented, stable immobilization on avidin surfaces, reducing random denaturation. | Thermo Fisher, A39259 |

| Candida antarctica Lipase B (CalB) | A widely used, robust model enzyme for benchmarking stability under flow and solvent stress. | Codexis, Chirazyme L-2 |

| Glucose Oxidase from Aspergillus niger | A model oxidase sensitive to UV and shear, used for stability assay development. | Sigma-Aldrich, G7141 |

Application Notes