Unleashing Evolution: A Comprehensive Guide to DNA Shuffling for Protein Engineering and Therapeutic Discovery

This article provides a detailed roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on DNA shuffling, a cornerstone directed evolution technique.

Unleashing Evolution: A Comprehensive Guide to DNA Shuffling for Protein Engineering and Therapeutic Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a detailed roadmap for researchers and drug development professionals on DNA shuffling, a cornerstone directed evolution technique. We explore the foundational concepts of in vitro molecular evolution, detail robust laboratory protocols and contemporary applications in enzyme and antibody engineering, offer troubleshooting strategies for common experimental pitfalls, and critically compare DNA shuffling to emerging mutagenesis methods. This guide synthesizes current best practices to empower scientists to effectively harness recombination for creating proteins with novel, optimized functions.

What is DNA Shuffling? Core Principles and Evolutionary Power in Protein Design

Directed evolution is a biomimetic laboratory method that accelerates the natural evolutionary process to engineer biomolecules with enhanced or novel properties. Framed within the broader thesis on DNA shuffling-based protein engineering, this approach mimics the principles of genetic variation, selection, and amplification, but under controlled conditions with defined goals. It has become a cornerstone for creating enzymes, antibodies, and other proteins for therapeutics, diagnostics, and industrial catalysis.

Foundational Methods & Quantitative Comparison

The field has evolved from early random mutagenesis techniques to sophisticated recombination-based methods. The following table summarizes key methodological approaches and their quantitative impact on library diversity and quality.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Directed Evolution Methodologies

| Method | Key Principle | Typical Mutation Rate/Event | Library Diversity Potential | Primary Advantage | Primary Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | Random nucleotide misincorporation during PCR. | 0.1-2 amino acid substitutions/gene. | Moderate (10⁶ - 10⁹) | Simple; introduces point mutations across gene. | Biased mutation spectrum; mostly single mutants. |

| DNA Shuffling (Stemmer, 1994) | Fragmentation & recombination of homologous genes. | Multiple crossovers per gene. | High (10¹⁰ - 10¹²) | Recombines beneficial mutations; explores sequence space efficiently. | Requires significant homology (>70%). |

| Family Shuffling | DNA shuffling of gene families. | Multiple crossovers from diverse parents. | Very High (10¹² - 10¹⁴) | Accesses vast functional diversity from nature. | Limited by parent sequence diversity. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis | Systematic randomization at predefined residues. | All 20 amino acids at chosen site(s). | Defined (20ⁿ for n sites) | Focuses exploration on key regions (e.g., active site). | Requires structural or mechanistic knowledge. |

| CASTing / ISM | Combinatorial Active-Site Saturation Test / Iterative Saturation Mutagenesis. | Iterative cycles of saturation at few residues. | Focused & Iterative | Systematically optimizes active site clusters. | Requires careful residue choice. |

| Orthogonal Replication | Using mutagenic bacterial strains (e.g., Mutazyme II). | Continuous low-level mutation during plasmid propagation. | Continuous | Can be coupled with continuous selection systems. | Lower control over mutation timing/rate. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: DNA Shuffling and Selection for Thermostable Enzyme

Objective: To recombine multiple homologous parent genes to generate chimeric enzymes with improved thermostability.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Parental Genes: Plasmid DNA encoding 3-5 homologous enzymes (≥70% identity).

- DNase I: For random fragmentation of genes.

- PCR Reagents: dNTPs, Taq DNA polymerase (or non-proofreading), primers flanking gene.

- Purification Kits: Gel extraction and PCR purification kits.

- Expression Vector & Host: Standard plasmid (e.g., pET series) and E. coli expression strain.

- Selection Medium: Contains substrate for activity screen and/or is incubated at elevated temperature.

Procedure:

- Gene Preparation: Amplify each parent gene separately using standard PCR. Purify products.

- Fragmentation: Pool equimolar amounts of genes (1-10 µg total). Digest with DNase I (0.15 units/µg DNA) in 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MnCl₂ at 25°C for 10-20 minutes. Quench with 10 mM EDTA.

- Size Selection: Run fragments on 2-3% agarose gel. Excise and purify fragments in the 50-150 bp range.

- Reassembly PCR: Assemble fragments without primers. Use 1-10 ng of purified fragments in a PCR mix with Taq polymerase. Thermocycle: 95°C 2 min; then 30-45 cycles of [95°C 30s, 50-60°C 30s, 72°C 30s]; final 72°C 5 min. This allows fragments to prime each other based on homology, reforming full-length genes.

- Amplification: Use 1 µL of reassembly product as template in a standard PCR with gene-specific flanking primers to amplify full-length shuffled genes.

- Cloning & Transformation: Digest shuffled genes and expression vector with appropriate restriction enzymes. Ligate and transform into competent E. coli.

- Screening/Selection: Plate cells on selection medium or pick colonies into 96-well plates for expression. Perform a high-throughput activity assay after heat challenge (e.g., incubate cell lysates at 60°C for 30 min before assay).

- Analysis: Sequence hits to identify crossover points and mutations. Characterize purified improved variants.

Protocol: Site-Saturation Mutagenesis for Substrate Scope Expansion

Objective: To randomize a specific active-site residue to alter enzyme substrate specificity.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- Template Plasmid: Vector containing the wild-type gene.

- Degenerate Oligonucleotides: Primers containing NNK codon (N=A/T/G/C; K=G/T) at target residue.

- High-Fidelity Polymerase: For inverse PCR (e.g., Phusion).

- DpnI: Restriction enzyme to digest methylated parental template.

- Competent Cells for transformation.

Procedure:

- Primer Design: Design two complementary primers containing the NNK degenerate codon, flanked by 15-20 bp of perfect homology on each side. Primers should be reverse-complement and point towards each other on the plasmid.

- Inverse PCR: Set up PCR with plasmid template, degenerate primers, and high-fidelity polymerase. This amplifies the entire circular plasmid, linearizing it and incorporating the mutation.

- Template Digestion: Treat PCR product with DpnI (37°C, 1-2 hrs) to selectively digest the methylated parental template DNA.

- Self-Ligation: Purify the linear, mutated PCR product. Use a ligase (e.g., T4 DNA Ligase) under conditions favoring intramolecular ligation to recircularize the plasmid.

- Transformation: Transform ligation product into competent E. coli. The theoretical library size is 32 variants (NNK encodes all 20 amino acids + 1 stop codon).

- Screening: Screen colonies for activity against the new target substrate. Sequence active clones to identify the successful amino acid substitution.

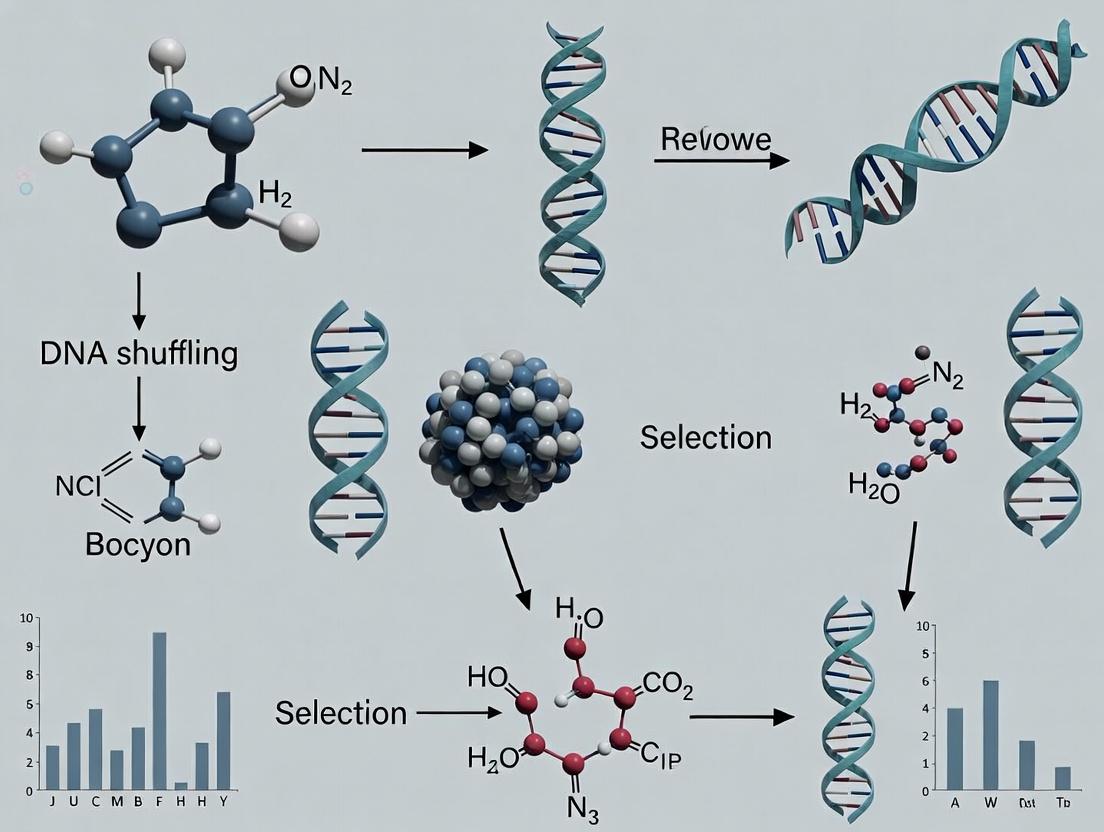

Visualizing the Directed Evolution Workflow

Title: The Iterative Cycle of Directed Evolution

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Directed Evolution Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale | Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR Kit | Provides optimized buffer conditions (e.g., biased [Mg²⁺], [Mn²⁺]) and polymerase to introduce random point mutations during PCR. | Commercial kits (e.g., from Agilent, Jena Bioscience) ensure reproducible mutation rates. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | For random fragmentation of DNA in shuffling protocols. Requires controlled digestion in presence of Mn²⁺ to produce random double-strand breaks. | Critical for DNA shuffling and related recombination methods. |

| Non-Proofreading Polymerase | Polymerase lacking 3'→5' exonuclease activity, essential for error-prone PCR and the primer extension steps in DNA shuffling. | Taq DNA polymerase is standard. Mutazyme variants offer different mutational spectra. |

| Restriction Enzyme DpnI | Cuts only methylated DNA (dam methylation pattern of most E. coli strains). Used to selectively digest the parental plasmid template after inverse PCR, enriching for newly synthesized mutant DNA. | Essential for site-saturation mutagenesis and other PCR-based mutagenesis methods. |

| NNK Degenerate Codon Oligos | Oligonucleotides containing the NNK sequence for site-saturation mutagenesis. NNK provides all 20 amino acids with only one stop codon, offering the best coverage with 32 codons. | Standard for creating "saturation" libraries at single residues. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay Reagents | Colorimetric, fluorogenic, or growth-based substrates that enable rapid testing of thousands of variants for the desired function (activity, stability, binding). | The bottleneck of directed evolution; assay quality dictates success. |

| Phage or Yeast Display System | Links genotype (displayed protein variant) to phenotype (binding affinity) on the surface of phage or yeast, allowing efficient selection from vast libraries (10⁹-10¹¹) by binding to an immobilized target. | Crucial for antibody and peptide engineering. |

Within the field of directed evolution for protein engineering, DNA shuffling stands as a pivotal method for in vitro homologous recombination. This protocol deconstructs the core mechanism, enabling the generation of diverse mutant libraries from a pool of parent genes. The process involves three central phases: 1) Fragmentation of related DNA sequences, 2) Reassembly of these fragments via primerless PCR, and 3) PCR-Driven Amplification of the reassembled full-length chimeric genes. This approach accelerates the exploration of sequence space, facilitating the development of proteins with improved stability, activity, or novel functions for therapeutic and industrial applications.

Table 1: Critical Parameters for DNA Shuffling Protocol Optimization

| Parameter | Typical Range / Value | Effect on Library Quality | Recommended Starting Point |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNase I Concentration | 0.15 - 0.30 U/µg DNA | Higher = smaller fragments (<100bp); Lower = larger fragments (>200bp) | 0.20 U/µg DNA |

| Fragment Size Range | 50 - 200 bp | Smaller = higher crossover frequency; Larger = higher chance of functional hybrids | 50-100 bp (gel-purified) |

| DNA Concentration in Reassembly | 10 - 100 ng/µL | Too low = inefficient priming; Too high = mispriming & non-specific products | 30 ng/µL |

| Reassembly PCR Cycles | 40 - 60 cycles | Fewer = incomplete reassembly; More = increased point mutation load | 45 cycles |

| Homology Requirement | > 70% identity | Lower homology drastically reduces recombination efficiency | > 80% for robust shuffling |

| Final Amplification Cycles | 20 - 30 cycles | Amplifies full-length, reassembled products | 25 cycles |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard DNA Shuffling of Homologous Parent Genes

Objective: To create a chimeric library from 2-5 related genes (>70% identity).

Materials: Purified parent genes (PCR products or plasmids), DNase I, MnCl₂, Agarose gel electrophoresis system, PCR purification kit, QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit, DNA polymerase with proofreading, dNTPs.

Procedure:

- Pool & Fragment:

- Combine 1-5 µg of total parent DNA in 100 µL of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MnCl₂ (pH 7.4).

- Add DNase I to a final concentration of 0.20 U/µg DNA. Incubate at 25°C for 10-20 min.

- Monitor fragmentation by running 10 µL on a 2% agarose gel. Target smear centered at ~50-100 bp.

- Stop reaction by heating at 90°C for 10 min. Purify fragments using a PCR clean-up kit.

Primerless Reassembly:

- Set up a 50 µL reassembly PCR: 30 ng/µL purified fragments, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1x PCR buffer, 2 mM MgCl₂, 0.5 U/µL DNA polymerase.

- Thermocycler Program: 95°C for 2 min; 45 cycles of [94°C for 30 sec, 50-55°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec + 5 sec/cycle]; 72°C for 5 min. The incremental extension time allows growing fragments to anneal and extend.

Amplification of Full-Length Products:

- Dilute 2 µL of reassembly product into 50 µL standard PCR containing gene-specific forward and reverse primers (0.5 µM each).

- Thermocycler Program: 95°C for 2 min; 25 cycles of [94°C for 30 sec, Tm of primers for 30 sec, 72°C for 1 min/kb]; 72°C for 5 min.

- Run product on agarose gel, excise, and purify the band corresponding to the expected full-length gene.

Protocol 2: Staggered Extension Process (StEP) – A Simplified Shuffling Method

Objective: Single-tube shuffling via very short annealing/extension steps.

Materials: Parent DNA templates, primers, DNA polymerase, dNTPs.

Procedure:

- Set up a standard 50 µL PCR mix containing all parent templates (equal molarity), primers, dNTPs, and polymerase.

- Run StEP Thermocycling: 95°C for 2 min; 80-100 cycles of [94°C for 30 sec, 55°C for 5-10 sec]. The critically short annealing/extension forces incomplete extension products to denature and re-anneal to different parental templates in subsequent cycles, enabling recombination.

- Use 2 µL of StEP product as template for a final 20-cycle standard PCR to amplify full-length chimeric genes.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Shuffling

| Item | Function & Critical Notes |

|---|---|

| DNase I (RNA-free) | Creates random double-strand breaks in parent DNA. Critical: Use with Mn²⁺ (not Mg²⁺) to generate fragments with blunt ends or 1-2 nt overhangs. |

| Proofreading DNA Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, Q5) | High-fidelity enzyme essential for reassembly PCR to minimize spurious point mutations. |

| QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit | For precise size selection of fragmented DNA (50-100 bp) and final full-length product purification. |

| Nucleotide Triphosphates (dNTPs) | High-quality, pH-balanced dNTP mix for efficient extension during low-stringency cycling. |

| Agarose (High-Resolution) | For accurate analysis and isolation of small DNA fragments and final genes. |

| Gene-Specific Primers | High-performance HPLC-purified primers for the final amplification of shuffled libraries. |

| MgCl₂ / MgSO₄ Solution | Optimized concentration is crucial for polymerase fidelity and efficiency in reassembly. |

| Thermostable Polymerase Buffer | Provides optimal pH, ionic strength, and cofactors. Must match the polymerase used. |

Visualization of Core Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: DNA Shuffling Core Workflow

Diagram 2: Fragment Reassembly Logic

This Application Note outlines protocols and key data for harnessing sexual recombination—specifically DNA shuffling—for rapid functional diversification of proteins. The methodology is a cornerstone of directed evolution, accelerating the exploration of functional sequence space beyond natural evolution rates. It is framed within a broader thesis on protein engineering, focusing on generating novel biomolecules for therapeutic and industrial applications. The core principle involves the in vitro recombination of homologous DNA sequences, mimicking sexual recombination to generate chimeric offspring with improved or novel functions.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of DNA Shuffling vs. Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) in Protein Engineering Campaigns

| Parameter | DNA Shuffling | Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) |

|---|---|---|

| Library Diversity Type | Combinatorial / Recombination. Mixes beneficial mutations from parents. | Point Mutations Only. Accumulates random base substitutions. |

| Average Mutation Rate per Gene | Variable; depends on homology. Typically 0.5-2% nucleotide difference. | Controlled by reaction conditions (e.g., 0.1-2% nucleotide). |

| Probability of Accumulating Beneficial Mutations | High. Allows "crossing over" of multiple beneficial mutations in a single step. | Low. Beneficial mutations are isolated; combination requires sequential rounds. |

| Functional Hit Rate in Library | Often 10-100x higher than epPCR for complex traits requiring multiple changes. | Typically low (<0.1%) for traits requiring >1 mutation. |

| Typical Library Size for Screening | 10⁴ - 10⁶ clones often sufficient. | 10⁶ - 10⁸ clones may be required. |

| Key Advantage | Rapid functional diversification and property mixing. | Exploration of local sequence space near a parent. |

Table 2: Published Case Studies Utilizing DNA Shuffling

| Target Protein | Parent Genes / Fragments | Key Improved Trait(s) | Fold Improvement / Outcome | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta-lactamase | Multiple homologous genes from diverse bacteria. | Antibiotic resistance (against cefotaxime). | 32,000-fold increase in resistance. Demonstrated power of shuffling across family homologs. | Stemmer, 1994 |

| Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) | GFP variants with different spectral properties. | Fluorescence intensity, folding efficiency. | 45-fold brighter GFP generated (e.g., "Cycle 3" GFP). | Crameri et al., 1996 |

| Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α) | Human and murine TNF-α. | Reduced cytotoxicity while retaining anti-tumor activity. | Generated novel, therapeutically viable variants with decoupled functions. | van de Vent et al., 2003 |

| Antibody Fragments (scFv) | Family of human V-genes. | Affinity, stability, expression yield. | Picomolar affinity antibodies from naive libraries; aggregation-resistant scaffolds. | Recent: Jäger et al., 2022 |

Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Standard DNA Shuffling for a Single Gene Family

Objective: To create a shuffled library from a set of 2-5 homologous genes (≥70% identity).

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit.

Procedure:

- Gene Preparation: Isolate and purify the DNA fragments of the target homologous genes (e.g., via PCR amplification with primers containing appropriate restriction sites for subsequent cloning).

- Fragmentation: Digest 1-5 µg of the pooled DNA fragments with DNase I in a 100 µL reaction.

- Buffer: 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MnCl₂.

- DNase I Concentration: Titrate (typically 0.0015-0.015 units/µg DNA) to yield random fragments of 50-200 bp. Incubate at 25°C for 10-20 minutes. Stop reaction by adding EDTA to 10 mM and heating to 90°C for 10 minutes.

- Purification: Gel-purify fragments in the 50-200 bp range using a commercial kit.

- Reassembly PCR (Self-Priming):

- Reaction Mix: 100-200 ng of purified fragments, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, 1x Taq polymerase buffer, no added primers.

- Thermocycling: Denature at 95°C for 2 min. Then 40-60 cycles of: 95°C for 30 sec, 50-60°C (annealing temp based on gene homology) for 30 sec, 72°C for 30-60 sec (extension time depends on desired full-length product).

- Amplification of Full-Length Products: Dilute the reassembly product 1:50. Perform a standard PCR with gene-specific forward and reverse primers that anneal to the ends of the full-length gene.

- Cloning and Library Construction: Digest the amplified shuffled pool and vector with appropriate restriction enzymes. Ligate and transform into a competent expression host (e.g., E. coli).

- Screening/Selection: Apply relevant high-throughput screen or selection pressure (e.g., antibiotic concentration, fluorescence, enzymatic assay) to identify improved variants.

Protocol 3.2: StEP (Staggered Extension Process) Recombination

Objective: A simpler, primer-based alternative to DNase I shuffling for in vitro recombination.

Procedure:

- Template Mix: Combine 2-5 homologous DNA templates (10-50 ng each) in a PCR tube.

- StEP Cycling:

- Reaction Mix: 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1x Taq buffer, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, gene-specific forward and reverse primers (0.2 µM each), 1.25 U Taq polymerase.

- Thermocycling Program: Run 80-100 cycles of: 95°C for 30 sec (denaturation), 55°C for 5-15 sec (short annealing/extension). The critical short extension time prevents full-length synthesis, allowing fragments to prime off different templates in subsequent cycles.

- Final Extension: After the StEP cycles, run a final extension at 72°C for 5 minutes to complete any near-full-length products.

- Cloning and Screening: Clone the resulting PCR product as in Protocol 3.1, Step 6.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: DNA Shuffling Experimental Workflow

Diagram Title: Principle of Sexual Recombination in DNA Shuffling

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Reagent | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| DNase I (Rnase-free) | Enzyme for random fragmentation of DNA. Critical: Use with Mn²⁺ to produce random double-stranded breaks. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Phusion) | For accurate amplification of parent genes and final shuffled library. Minimizes introduction of extraneous point mutations. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Often used in the reassembly PCR step due to its lower fidelity and ability to perform non-homologous recombination. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests methylated template DNA (e.g., from plasmid preps) after PCR, reducing parental background in libraries. |

| Gel Extraction Kit | For precise size selection of fragmented DNA (50-200 bp) post-DNase I digestion. |

| Cloning Vector (e.g., pET, pBAD series) | Expression vectors with inducible promoters for high-throughput protein expression in bacterial hosts. |

| Electrocompetent E. coli (e.g., NEB 10-beta, BL21(DE3)) | For high-efficiency transformation of the ligated shuffled library to ensure large library size. |

| Microtiter Plates (96-/384-well) | Format for high-throughput expression and screening of library clones. |

| Fluorescence/Luminescence Plate Reader | Essential for screening libraries based on optical reporters (enzyme activity, binding, stability). |

Within the context of protein engineering via DNA shuffling, the generation of high-quality, diverse starting gene libraries is the foundational prerequisite for successful directed evolution campaigns. The quality of this initial diversity directly dictates the probability of isolating variants with desired functional improvements, such as enhanced stability, binding affinity, or catalytic activity in drug development. This document outlines core strategies, quantitative benchmarks, and detailed protocols for constructing robust starting libraries.

The following table summarizes key parameters for common gene library generation techniques relevant to DNA shuffling workflows.

Table 1: Comparison of Initial Diversity Generation Methods

| Method | Typical Diversity (Library Size) | Average Mutation Rate | Key Principle | Best for |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) | 10^6 – 10^9 | 0.1 – 2.0 amino acid substitutions/gene | Non-proofreading polymerase + Mn²⁺/biased dNTPs | Introducing random point mutations across a single parent gene. |

| DNA Shuffling (Homologous Recombination) | 10^7 – 10^12 | Variable, recombines existing mutations | Fragmentation & reassembly of homologous sequences (≥70% identity). | Recombining beneficial mutations from multiple parent genes/variants. |

| Oligonucleotide-Directed Mutagenesis | 10^7 – 10^10 | Designed, localized to specific sites | Spiking mutagenic oligonucleotides during gene synthesis/assembly. | Focused diversity on known hot-spots or regions of interest. |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) | ≤ 20^n (n=sites) | All amino acids at selected position(s) | Using degenerate codons (e.g., NNK) to replace target codons. | Exploring all possible amino acid substitutions at one or a few residues. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Error-Prone PCR (epPCR) for Initial Library Creation

Objective: Generate a library of a single parent gene with random point mutations. Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" (Section 5). Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: In a 50 µL reaction, combine:

- 1x proprietary epPCR buffer (with MgCl₂ and additional MnCl₂).

- 0.2 mM each dATP and dGTP.

- 1.0 mM each dCTP and dTTP (biased nucleotide ratios increase error rate).

- 0.3 µM forward and reverse primers flanking the gene.

- 10 – 100 ng template DNA.

- 2.5 U of non-proofreading DNA polymerase (e.g., Taq).

- Thermocycling: Use standard cycling conditions for your gene, but limit to 25-30 cycles to avoid excessive wild-type amplification and second-order mutations.

- Purification: Run the PCR product on an agarose gel, excise the correct band, and purify using a gel extraction kit.

- Cloning: Digest the purified epPCR product and vector with appropriate restriction enzymes. Ligate and transform into a competent E. coli strain with high transformation efficiency (>10^8 cfu/µg).

- Quality Control: Sequence 10-20 random clones to calculate the actual mutation frequency and spectrum (should be 1-15 nucleotide changes per gene).

Protocol 2: DNA Shuffling of Homologous Parent Genes

Objective: Recombine multiple related gene sequences (e.g., family shuffling from different species or improved variants) to create chimeric offspring. Procedure:

- Fragment Preparation: Digest 2-5 µg of each parent DNA (≥70% identity) with DNase I in the presence of Mn²⁺ to generate random fragments of 50-200 bp. Stop the reaction with EDTA and purify fragments.

- Reassembly PCR: Perform a primerless PCR in a 50 µL reaction:

- Combine ~10-50 ng/µL of purified fragments.

- Use a standard PCR buffer with proofreading polymerase.

- Cycle: 95°C for 2 min; then 40-60 cycles of [94°C for 30 sec, 50-60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec]. Fragments with homologous overlaps prime each other, reassembling into full-length genes.

- Amplification: Add outer primers (0.2 µM final) to the reassembly product and run 15-20 standard PCR cycles to amplify the full-length shuffled genes.

- Cloning & Transformation: As in Protocol 1, clone the shuffled pool into your expression vector and transform. Library size should exceed 10^7 independent clones for adequate coverage.

Mandatory Visualizations

Diagram Title: DNA Shuffling and Reassembly Workflow

Diagram Title: Prerequisites for a Successful Gene Library

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Library Construction

| Item | Function & Critical Note |

|---|---|

| Non-proofreading DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Essential for epPCR. Lacks 3'→5' exonuclease activity, allowing misincorporation of nucleotides. |

| Mutagenesis Buffer Kits (commercial epPCR) | Optimized buffers with adjusted Mg²⁺ and often Mn²⁺ to promote defined, tunable error rates. |

| DNase I (for shuffling) | Randomly cleaves dsDNA to generate fragments for homologous recombination during shuffling. |

| High-Efficiency Competent Cells (>10^8 cfu/µg) | Maximizes transformation yield to ensure the physical library size captures the theoretical diversity. |

| Degenerate Oligonucleotide Primers (NNK) | Encodes all 20 amino acids + a stop codon (N=A/T/G/C; K=G/T). Used for site-saturation mutagenesis. |

| Restriction Enzymes & Ligase | For precise cloning of library inserts into the expression vector backbone. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Services | Critical for pre-selection quality control to assess library diversity, mutation distribution, and bias. |

Willem P.C. Stemmer's seminal 1994 paper, "DNA shuffling by random fragmentation and reassembly: In vitro recombination for molecular evolution," revolutionized protein engineering. Framed within the broader thesis of DNA shuffling method development, this work introduced a method to rapidly evolve genes by mimicking natural sexual recombination in vitro. It provided a systematic, high-throughput alternative to traditional directed evolution, enabling the acceleration of research in enzyme optimization, antibody engineering, and therapeutic protein development—key pillars of modern drug discovery.

Stemmer's method demonstrated order-of-magnitude improvements in evolution efficiency. The following table summarizes key quantitative results from the original and immediate follow-up studies.

Table 1: Quantitative Outcomes from Stemmer's Foundational DNA Shuffling Experiments

| Target Gene / System | Improvement Metric | DNA Shuffling Result | Traditional (Error-Prone PCR) Result | Fold Improvement | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β-Lactamase (TEM-1) | Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) of Cefotaxime | 640 µg/mL | 16 µg/mL | 40x | Stemmer, PNAS (1994) |

| β-Lactamase (TEM-1) | MIC of Cefotaxime (after 3 shuffling cycles) | 32,000 µg/mL | (Baseline) | 2000x (from wild-type) | Stemmer, PNAS (1994) |

| β-Lactamase (TEM-1) | Library Size for Equivalent Improvement | ~50,000 variants | >10,000,000 variants | ~200x more efficient | Stemmer, PNAS (1994) |

| GFP (Green Fluorescent Protein) | Fluorescence Intensity (in E. coli) | 45-fold brighter | ~2-fold brighter | ~22x more effective | Crameri et al., Nature (1996) |

| Subtilisin E | Thermostability (Half-life at 65°C) | 50-fold increase | Not reported | N/A | Zhao & Arnold, NAR (1997) |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Original DNA Shuffling of β-Lactamase (Based on Stemmer, 1994)

Objective: Evolve TEM-1 β-lactamase for increased resistance to the antibiotic cefotaxime.

Materials:

- Template DNA: Wild-type TEM-1 gene.

- Enzymes: DNase I (from bovine pancreas), DNA polymerase I (Klenow fragment or Taq polymerase), DpnI restriction enzyme.

- Primers: Forward and reverse primers flanking the TEM-1 gene coding sequence.

- Reagents: dNTPs, MgCl₂, suitable PCR buffer, agarose gel electrophoresis supplies.

- Host Strain: E. coli (e.g., XL1-Blue) with low inherent antibiotic resistance.

- Selection Agent: Luria-Bertani (LB) agar plates with increasing concentrations of cefotaxime (0.01 µg/mL to 1000 µg/mL).

Methodology:

- Random Fragmentation:

- Purify the template DNA.

- Digest with DNase I in the presence of Mn²⁺ (not Mg²⁺) to generate random double-stranded breaks. Optimize conditions (enzyme concentration, time, temperature) to yield fragments of 50-200 bp.

- Heat-inactivate DNase I.

Reassembly PCR (Self-Priming Reassembly):

- Assemble a PCR reaction without added primers, containing the fragmented DNA, dNTPs, and a thermostable polymerase (e.g., Taq).

- Run a thermocycling program with very long extension times:

- 95°C for 2 min (initial denaturation).

- 40-60 cycles of: [94°C for 30 sec, 50-60°C for 30 sec, 72°C for 1-2 min].

- 72°C for 5-10 min (final extension).

- This step allows homologous fragments to prime off each other, recombining sequences from different templates.

Amplification PCR:

- Dilute the reassembly product.

- Perform a standard PCR using the flanking primers to amplify the full-length, reassembled genes.

Cloning & Selection:

- Digest the PCR product and vector with appropriate restriction enzymes. Ligate and transform into competent E. coli.

- Plate transformed cells onto LB agar containing a low, permissive concentration of cefotaxime (e.g., 0.01 µg/mL). Pool resulting colonies (~10⁴-10⁵).

- Prepare plasmid DNA from the pool. This DNA becomes the template for the next cycle of shuffling.

- Repeat shuffling (steps 1-4) for 3-5 cycles, increasing the cefotaxime concentration in the selection plates with each cycle.

Screening:

- After multiple cycles, plate clones on high-concentration cefotaxime plates (e.g., 100-500 µg/mL) to isolate individual resistant variants.

- Sequence candidate genes to identify beneficial mutations.

Protocol 2: Family Shuffling for Industrial Enzymes (Adapted from Crameri et al., 1996)

Objective: Recombine homologous genes from different species (Family Shuffling) to create chimeric proteins with superior properties.

Materials: As in Protocol 1, but with multiple template genes (e.g., GFP genes from different species).

Methodology:

- Template Preparation: Mix equimolar amounts of several homologous genes (e.g., gfp from Aequorea victoria, Renilla reniformis, etc.).

- Fragmentation & Reassembly: Follow Protocol 1, steps 1-3. The reassembly process will cross over between the different parental sequences.

- Selection/Screening: Use a high-throughput screen relevant to the desired property (e.g., fluorescence intensity using FACS or plate readers, thermostability via heat treatment followed by activity assay).

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram 1: DNA Shuffling Iterative Workflow

Diagram 2: Mimicking Natural Evolution In Vitro

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for DNA Shuffling Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| DNase I (Rnase-free) | Creates random double-stranded breaks in DNA template. Critical: Use with MnCl₂ buffer (not MgCl₂) to generate random fragments with blunt ends/short overhangs suitable for recombination. |

| High-Fidelity Thermostable Polymerase (e.g., Pfu, Q5) | Used in the final amplification PCR to minimize introduction of new, non-beneficial point mutations during library construction. |

| Standard Taq Polymerase | Often used in the primerless Reassembly PCR step due to its lower fidelity and ability to handle heterogeneous fragment priming. |

| DpnI Restriction Enzyme | Digests methylated parental template DNA (from plasmid prep in E. coli dam+ strains). Used after PCR to reduce background from non-shuffled templates. |

| Homologous Gene Family Templates | For family shuffling. Genes should share >60-70% DNA sequence identity for efficient cross-homologous recombination during reassembly. |

| High-Throughput Selection System | The driver of evolution. Can be: A) Antibiotic gradient plates (for resistance enzymes). B) FACS for fluorescence/binding. C) Microtiter plate-based activity assays coupled with robotic colony picking. |

| Specialized Cloning Vector | Expression vector optimized for the host (e.g., E. coli, yeast) with appropriate promoter and selection marker. Gateway or Golden Gate compatible vectors speed up library construction. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Platform | For post-selection library analysis. Identifies consensus mutations, tracks library diversity, and maps recombination breakpoints, far surpassing Sanger sequencing of individual clones. |

Mastering the Protocol: Step-by-Step DNA Shuffling Workflow and Cutting-Edge Applications

This protocol details the foundational in vitro recombination step in DNA shuffling, a cornerstone method in directed evolution for protein engineering. Within a broader thesis on advancing DNA shuffling methodologies, this breakdown focuses on the critical initial phase: fragmenting homologous parent genes and reassembling them into novel chimeric libraries. This process mimics natural recombination, accelerating the exploration of sequence space to evolve proteins with enhanced properties for therapeutic and industrial applications, directly relevant to drug development.

Application Notes

- Primary Application: Creation of diverse gene libraries from a set of homologous parent genes (e.g., family shuffling) or a single parent gene (for optimized variants).

- Key Advantages: Introduces multiple crossover events, recombining beneficial mutations from different parents. Can overcome the limitations of single-point mutagenesis.

- Considerations: Optimal fragment size is 50-200 bp. Excessive DNase I digestion or reassembly cycles can lead to short or rearranged products. The method is most effective with >70% sequence identity among parent genes for efficient hybridization.

- Downstream Processing: The reassembled full-length products are subsequently amplified by PCR (Step 3) and cloned into an expression vector for functional screening and selection.

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: DNase I Fragmentation of Parental DNA

Objective: To generate random fragments of 50-200 bp from pooled parental genes. Materials: Purified parental DNA plasmids or PCR products (collectively 1-10 µg), DNase I (RNase-free), 10x DNase I Reaction Buffer, 100 mM MnCl₂, 0.5 M EDTA, Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol, 100% ethanol, 70% ethanol, Nuclease-free water. Method:

- Digest Setup: Combine 1-10 µg pooled DNA, 5 µL 10x DNase I Reaction Buffer, and nuclease-free water to 48 µL. Add 1 µL of 100 mM MnCl₂ (final 2 mM).

- Titration: Dilute DNase I to 0.015 U/µL in cold nuclease-free water. Add 1 µL of diluted DNase I to the reaction. Incubate at 15°C for 10 minutes.

- Quench: Immediately add 5 µL of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0) and heat at 90°C for 10 minutes to inactivate DNase I.

- Purify: Extract with Phenol:Chloroform:Isoamyl Alcohol. Precipitate fragments with 2.5 volumes 100% ethanol. Wash pellet with 70% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in 20 µL nuclease-free water.

- Size Selection: Run fragments on a 2% agarose gel. Excise and purify DNA in the 50-200 bp range.

Table 1: DNase I Fragmentation Optimization Guide

| Parameter | Recommended Condition | Purpose & Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Cation | Mn²⁺ (2 mM) | Produces random double-strand breaks. Mg²⁺ leads to nicking. |

| Temperature | 15°C | Slows enzyme kinetics for controlled digestion. |

| Time | 5-15 min | Must be titrated for each enzyme lot. |

| [DNase I] | 0.003 U/µg DNA | Starting point; critical for optimal fragment size. |

| DNA Purity | High (A260/280 ~1.8) | Contaminants inhibit DNase I. |

| Goal Size | 50-200 bp | Optimal for primerless reassembly. |

Protocol B: Self-Priming Reassembly PCR

Objective: To reassemble random fragments into full-length genes through primerless PCR. Materials: Purified DNA fragments (50-200 bp), dNTP Mix (10 mM each), Taq DNA Polymerase (or high-fidelity polymerase), 10x PCR Buffer, Nuclease-free water. Method:

- Assembly Reaction: In a thin-walled PCR tube, combine: 100-200 ng purified fragments, 5 µL 10x PCR Buffer, 1 µL dNTP Mix (10 mM each), 2.5 U DNA Polymerase, water to 50 µL.

- Thermocycling (No Primers):

- Denaturation: 94°C for 2 min.

- Reassembly Cycles (25-45 cycles):

- 94°C for 30 sec (denature)

- 50-60°C for 30 sec (annealing of overlapping fragments) Critical

- 72°C for 1-2 min (extension) Time based on expected full-length product

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min.

- Hold: 4°C.

Table 2: Self-Priming Reassembly Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Setting | Rationale & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Fragment Input | 100 ng | Too little reduces yield; too much promotes misassembly. |

| Annealing Temp | 55°C | Must be optimized; depends on fragment Tm. |

| Cycle Number | 35 | Balances yield and accumulation of errors. |

| Extension Time | 1 min/kb | For the full-length target gene size. |

| Polymerase | Taq or Mix | Taq sufficient; high-fidelity if error minimization is critical. |

Protocol C: PCR Amplification of Full-Length Products

Objective: To amplify the reassembled full-length genes from Protocol B. Materials: Reassembly product (1-5 µL), Forward and Reverse Gene-Specific Primers (10 µM each), dNTP Mix, High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase, 10x PCR Buffer, Nuclease-free water. Method:

- Setup: In a fresh PCR tube, combine: 1-5 µL reassembly product, 1 µL each primer (10 µM), 5 µL 10x Buffer, 1 µL dNTPs, 1 U polymerase, water to 50 µL.

- Thermocycling:

- 95°C for 2 min.

- 25-30 Cycles: 95°C 30 sec, 55-65°C (primer Tm) 30 sec, 72°C 1 min/kb.

- 72°C for 5 min.

- 4°C hold.

- Analysis: Verify amplification and size on agarose gel. Purify product for cloning.

Diagrams

Title: DNA Shuffling Core Workflow

Title: Molecular Mechanism of Fragment Reassembly

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for DNase I Shuffling

| Reagent/Material | Function & Specification | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Endonuclease that cleaves ds/ss DNA. Requires Mn²⁺ for random double-strand scission. | Must be titrated for every new lot. Aliquot and store at -20°C. |

| Manganese Chloride (MnCl₂) | Divalent cation cofactor. Critical for producing random fragments, not nicks. | Use separate stock (100 mM). Final conc. 2 mM. Do not substitute with Mg²⁺. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies reassembled products with low error rate for faithful library generation. | Use in the final amplification step (Protocol C). |

| Standard Taq Polymerase | Catalyzes the primerless extension during the reassembly step. | Fidelity is less critical here; extension ability is key. |

| dNTP Mix | Nucleotide substrates for DNA polymerization during reassembly and PCR. | Use balanced, high-quality mix to prevent misincorporation. |

| Agarose Gel Electrophoresis System | For size selection of fragments (50-200 bp) and analysis of reassembly/PCR products. | Use 2-3% gels for small fragment resolution. |

| Gel Extraction Kit | Purifies DNA fragments from agarose gels after size selection. | Essential for obtaining clean fragment pools. |

| Gene-Specific Primers | Flank the gene of interest. Used only in the final amplification step (Protocol C). | Should be designed to match conserved regions of parent genes. |

Within the broader thesis of DNA shuffling-based protein engineering research, the evolution from classical family shuffling towards methods offering enhanced control over crossover frequency and location has been critical. This article details three such modern variations—StEP, ITCHY, and RACHITT—framed as advanced tools for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to engineer proteins with tailored properties.

Application Notes & Comparative Analysis

Staggered Extension Process (StEP)

StEP simplifies in vitro recombination by replacing the traditional fragmentation and reassembly steps with short cycles of primerless PCR. This method generates diversity through template switching during repeated, abbreviated elongation steps.

Incremental Truncation for the Creation of Hybrid Enzymes (ITCHY)

ITCHY enables the creation of single-crossover hybrid libraries independent of DNA homology. It relies on the controlled, incremental truncation of gene fragments followed by their ligation, allowing for the exploration of fusion points at the amino acid level.

Random ChimeraGenesis on Transient Templates (RACHITT)

RACHITT offers high crossover frequencies and low parental bias. It involves hybridizing fragmented single-stranded DNA from one parent onto a full-length, uracil-containing template strand from another, followed by enzymatic fill-in, ligation, and template degradation.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of StEP, ITCHY, and RACHITT

| Parameter | StEP | ITCHY | RACHITT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homology Requirement | Moderate to High | None Required | Moderate to High |

| Typical Crossover Frequency | Moderate | Single, controlled crossover | Very High (10-20 crossovers/gene) |

| Parental Bias | Can be moderate | Low | Very Low |

| Library Complexity | High | Limited (focused) | Extremely High |

| Primary Control Mechanism | Extension time/Temperature | Truncation rate/time | Fragment size & template hybridization |

| Key Advantage | Simplicity; no fragmentation | Homology-independent fusions | Comprehensive shuffling; low bias |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: StEP Recombination

Objective: To recombine two or more homologous parent genes via staggered extension.

- Template Preparation: Mix equimolar amounts (e.g., 100 ng each) of plasmid DNA containing parent genes in a PCR tube.

- StEP PCR Setup: Prepare a 50 µL reaction containing: 1x PCR buffer, 200 µM dNTPs, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, parent DNA mix, and 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase. Do not add primers.

- Thermocycling: Perform 80-100 cycles of: 94°C for 30 sec (denaturation), 55°C for 5-15 sec (annealing/very short extension). The critical short extension time limits polymerase processivity, forcing template switching.

- Full-Length Product Amplification: After StEP cycles, add gene-specific primers to the reaction (or use an aliquot as template in a fresh primed PCR). Perform standard PCR to amplify the reassembled, full-length chimeric genes.

- Clone the PCR product into an appropriate expression vector for screening.

Protocol 2: ITCHY Library Construction

Objective: To create a library of hybrid genes via incremental truncation.

- Fragment Preparation: Amplify two gene fragments (A and B) to be fused. Clone each separately into a vector with a flanking exonuclease (e.g., Exonuclease III) resistant site (e.g., phosphorothioate nucleotides) at the end opposite the desired fusion junction.

- Controlled Truncation: Digest plasmids linearly at a site near the future fusion point. Subject separate aliquots to Exonuclease III digestion at a controlled temperature (e.g., 22°C). Remove aliquots at timed intervals (e.g., every 30 sec over 10 min) to a tube containing stop solution (e.g., chelating agent). This creates a nested set of truncations.

- Blunt-Ending & Purification: Treat truncated DNA with a single-strand nuclease (e.g., S1 nuclease) and Klenow fragment to create blunt ends. Gel-purify the pool of truncated fragments.

- Ligation & Ligation: Ligate the truncated pool of Fragment A with the truncated pool of Fragment B in a vector backbone. Transform into E. coli to generate the ITCHY library.

Protocol 3: RACHITT Protocol

Objective: To achieve extensive, low-bias recombination using a transient template.

- Donor Fragment Preparation: Fragment one parent gene (the "donor") by DNase I treatment or physical shearing. Generate single-stranded fragments (ss-fragments) by denaturation or strand separation.

- Template Strand Preparation: PCR-amplify the second parent gene (the "template") using primers containing dUTP. Generate a single-stranded, uracil-containing template using strand-selective digestion (e.g., with uracil DNA glycosylase and endonuclease).

- Hybridization & Polishing: Hybridize the donor ss-fragments onto the full-length template strand. Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase and ligase to fill gaps and seal nicks, creating a complementary strand. The template strand now contains chimeric information.

- Template Degradation: Treat the product with uracil DNA glycosylase and an abasic endonuclease to specifically degrade the original uracil-containing template strand.

- PCR Amplification: Amplify the resulting full-length chimeric strand using gene-specific primers, then clone for screening.

Visualization of Method Workflows

Title: StEP Recombination Workflow

Title: ITCHY Library Construction Steps

Title: RACHITT Method Process

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function in Modern Shuffling |

|---|---|

| Thermostable DNA Polymerase (e.g., Taq) | Core enzyme for StEP cycles and final PCR amplification. Lower fidelity can be beneficial for introducing additional point mutations. |

| Exonuclease III | Processive 3'→5' exonuclease used in ITCHY for controlled, time-dependent truncation of DNA ends. |

| Uracil DNA Glycosylase (UDG) | Critical for RACHITT; specifically removes uracil bases, enabling degradation of the template strand and isolation of the synthesized chimeric strand. |

| DNase I (or Nebulizer) | For generating random fragments of the donor parent gene in RACHITT. |

| T4 DNA Ligase | Joins DNA fragments during library construction (ITCHY, RACHITT post-repair). |

| Klenow Fragment & S1 Nuclease | Used in ITCHY to create blunt-ended DNA from exonuclease III-truncated fragments. |

| Phosphorothioate Nucleotides (S-dNTPs) | Incorporated during PCR to create exonuclease-resistant sites for ITCHY, protecting one end of the gene from truncation. |

| dUTP | Incorporated into the template parent during PCR for RACHITT, providing the handle for subsequent selective degradation. |

Within the broader thesis on DNA shuffling-driven protein engineering, this application note explores the directed evolution of industrial enzymes for enhanced operational stability. The core thesis posits that iterative DNA shuffling, coupled with high-throughput screening against stringent environmental pressures, is the most effective strategy for generating multi-property optimized biocatalysts. This document provides specific protocols and data for engineering thermostability and pH robustness in a model hydrolase enzyme.

Current Data & Performance Benchmarks

Recent advancements in DNA shuffling for enzyme stabilization are quantified below.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Engineered Enzymes via DNA Shuffling

| Enzyme Class (Parent) | DNA Shuffling Rounds | Key Mutation(s) Identified | ΔTm (°C) | pH Robustness Range (Retaining >80% Activity) | Half-life at 70°C (min) | Reference (Year) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lipase (Bacillus sp.) | 3 | A132S, L189I, Q287R | +12.5 | 5.0–10.0 (vs. 6.0–9.0) | 240 (vs. 15) | Recent Study A (2023) |

| α-Amylase (Aspergillus sp.) | 4 | G228P, H156Y, K272E | +9.8 | 3.5–8.5 (vs. 5.0–7.5) | 180 (vs. 25) | Recent Study B (2024) |

| Cellulase (Fungal) | 2 | S245C, N312D, A411V | +7.2 | 4.0–9.0 (vs. 5.0–8.0) | 95 (vs. 10) | Recent Study C (2023) |

| Protease (Bacterial) | 5 | M138L, S188C, A259V | +14.1 | 6.0–11.0 (vs. 7.0–10.0) | 310 (vs. 20) | Recent Study D (2024) |

Table 2: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Outcomes for Shuffled Libraries

| Library Size | Screening Assay | Hit Rate (%) | Average Improvement in Melting Temp (°C) | Most Common Structural Feature in Hits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 x 10⁵ | Thermofluor (DSF) | 0.15 | +6.3 | Proline substitutions in loops |

| 5.0 x 10⁴ | pH-Gradient Microplate | 0.08 | N/A | Surface charge redistribution |

| 8.0 x 10⁴ | Combined Thermal & pH Challenge | 0.05 | +8.7 | Combined salt bridges & hydrophobic core packing |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: DNA Shuffling for Diverse Library Creation

Objective: Generate a chimeric gene library from homologous parent genes.

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit (Section 5). Procedure:

- Gene Fragmentation: Combine 1-2 µg of each purified parent gene (≥70% identity) in a 50 µL reaction with 0.15 U of DNase I, 1x DNase I buffer, and 1 mM MnCl₂. Incubate at 15°C for 10-20 min until fragments of 50-200 bp are observed on a gel. Heat-inactivate at 90°C for 10 min.

- Reassembly PCR: In a 50 µL volume, combine fragmented DNA (without purification) at ~10-30 ng/µL, 1x PCR buffer, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 2.5 mM MgCl₂, and 0.5 U/µL Taq polymerase (no primers). Run: 40 cycles of (94°C for 30s, 50-55°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s + 5s/cycle).

- Amplification: Add gene-specific primers (0.4 µM final) to 5 µL of the reassembly product. Perform standard PCR (25-30 cycles) to amplify full-length chimeric genes.

- Cloning & Transformation: Purify the PCR product, digest with appropriate restriction enzymes, and ligate into an expression vector. Transform into high-efficiency E. coli cells to create the primary library. Aim for >10⁵ independent clones.

Protocol 3.2: High-Throughput Screening for Thermostability & pH Robustness

Objective: Identify variants with improved stability from the shuffled library.

Materials: See Scientist's Toolkit (Section 5). Procedure:

- Expression & Lysate Preparation: Inoculate library clones in 96-deep-well plates. Induce expression. Harvest cells by centrifugation and lyse using chemical or enzymatic (lysozyme) lysis. Clarify lysates by centrifugation.

- Primary Screen – Differential Scanning Fluorimetry (DSF):

- Prepare a master mix containing 1x final concentration of a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange) in pH 7.0 buffer.

- Mix 18 µL of master mix with 2 µL of clarified lysate per well in a 96-well PCR plate.

- Run in a real-time PCR instrument: ramp temperature from 25°C to 95°C at 1°C/min, measuring fluorescence.

- Calculate Tm from the melting curve's inflection point. Select top ~5% with highest Tm for secondary screening.

- Secondary Screen – pH-Robust Activity Assay:

- For each selected variant, prepare activity assay buffer at three critical pHs (e.g., pH 4.5, 7.0, 9.5).

- Incubate 10 µL of lysate with 90 µL of pre-heated buffer-substrate mix in a microplate.

- Measure initial reaction velocity (e.g., by absorbance change) simultaneously across pH conditions.

- Rank variants based on the breadth of pH activity and residual activity after a 10-minute pre-incubation at 60°C.

Diagrams & Visualizations

DNA Shuffling and Screening Workflow

HTS Cascade for Stability

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Protocol | Key Specification / Example |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I (RNAse-free) | Randomly fragments parental genes to create DNA shuffling building blocks. | Must be used with Mn²⁺ to create double-stranded breaks. |

| Proofreading DNA Polymerase | Amplifies reassembled full-length genes with high fidelity. | e.g., Q5, Phusion. Critical for minimizing spurious mutations. |

| Thermostable Fluorescent Dye | Reports protein unfolding in DSF primary screens. | e.g., SYPRO Orange, Protein Orange. Binds hydrophobic patches exposed upon denaturation. |

| Broad-Range pH Buffer System | Enables activity assays across wide pH range for robustness screening. | e.g., Citrate-Phosphate-Borate buffers; must not chelate essential metal cofactors. |

| Chemical Lysis Reagent | Rapid, reproducible cell lysis in 96/384-well format for HTS. | e.g., B-PER II, PopCulture; compatible with downstream activity and DSF assays. |

| Engineered Expression Host | Provides proper folding and disulfide bond formation for industrial enzymes. | e.g., E. coli BL21(DE3) pLysS, Pichia pastoris; reduces inclusion body formation. |

1. Introduction and Thesis Context This application note details practical methodologies for affinity maturation, framed within the broader thesis that DNA shuffling-driven directed evolution remains a cornerstone of modern protein engineering. It provides a robust, iterative framework for generating high-affinity binders, applicable to both conventional antibodies and novel scaffold proteins. The protocols integrate traditional library generation with modern screening platforms.

2. Key Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Comparison of Library Generation Methods for Affinity Maturation

| Method | Library Size (Typical) | Mutation Rate | Key Advantage | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Error-Prone PCR | 10^6 - 10^9 | 0.1-2% per gene | Simplicity; introduces random mutations | Initial diversity creation |

| DNA Shuffling | 10^7 - 10^11 | Variable, recombination-based | Recombines beneficial mutations; mimics natural evolution | Intermediate/advanced rounds |

| Site-Saturation Mutagenesis (SSM) | ~10^2 per position | Targeted to specific residues | Focuses on CDR/Hotspot residues | Fine-tuning specific regions |

| Oligonucleotide-Directed Mutagenesis | 10^8 - 10^10 | Defined and random | High control over mutation location & frequency | CDR walking/parsimonious mutagenesis |

Table 2: Common Screening Platforms for Binder Isolation

| Platform | Throughput (Typical) | Approx. Time to Screen 10^8 | Key Metric | Required Affinity (Starting) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phage Display | 10^9 - 10^11 | 1-2 weeks | Enrichment (Output/Input ratio) | µM - nM |

| Yeast Surface Display | 10^7 - 10^9 | 1-2 weeks | Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) | nM |

| Ribosome Display | 10^12 - 10^14 | Days-weeks | Recovery after selection | nM - pM |

| Microfluidic Sorting (e.g., FADS) | 10^7 - 10^9 | Days | Binding kinetics (kon, koff) via label-free | nM - pM |

3. Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: DNA Shuffling for Antibody Fab Fragment Affinity Maturation Objective: To recombine mutations from selected clones of a primary library to generate evolved variants with additive/synergistic effects. Materials: Pool of plasmid DNA from ~20-50 selected clones, DpnI restriction enzyme, Taq DNA Polymerase, PCR reagents, primers for full gene amplification. Procedure: 1. Gene Fragmentation: Set up a PCR-like reaction with the pooled DNA as template. Use limited dNTPs and include 0.25 mM MnCl2 to promote polymerase misincorporation, generating a pool of random fragments (50-100 bp). 2. Fragment Purification: Run the product on an agarose gel and excise fragments in the 50-150 bp range. Purify using a gel extraction kit. 3. Reassembly PCR: Perform a PCR without primers. Use the purified fragments (10-50 ng) as both template and primer. Cycle: 95°C for 3 min; then 35 cycles of [94°C for 30s, 50-60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s]. This allows homologous fragments to prime each other, reassembling full-length genes. 4. Amplification: Add outer primers to the reassembly product and perform standard PCR to amplify the full-length shuffled library. 5. Cloning & Expression: Clone the shuffled library into your appropriate display vector (phage, yeast) for the next round of selection.

Protocol 2: Yeast Surface Display for Kinetic Screening Objective: To isolate clones with improved off-rates (koff) following affinity maturation. *Materials:* Induced yeast library expressing scFv/Fab, biotinylated antigen, anti-c-MYC-FITC (clone 9E10), Streptavidin-PE (or SA-APC), magnetic beads coated with anti-FLAG or similar epitope, FACS buffer (PBS + 0.5% BSA), FACS sorter. *Procedure:* 1. Labeling: Induce ~1x10^7 yeast cells. Wash and resuspend in cold FACS buffer. Split into two aliquots. 2. Kinetic Challenge: To the first aliquot (for koff selection), add biotinylated antigen at a concentration near the K_D of the parent clone. Incubate on ice for 1 hour. Wash away unbound antigen. Add a large excess (>100x) of unlabeled antigen and incubate at room temperature. Take samples at time points (e.g., 0, 30 min, 2h, 5h), immediately quenching by diluting into ice-cold buffer. 3. Staining: Stain all samples (including the second, no-challenge aliquot as a control) with anti-c-MYC-FITC (for expression) and Streptavidin-PE (for antigen binding). Keep on ice. 4. Gating & Sorting: Analyze on a flow cytometer. Gate for cells expressing the protein (FITC+). For the kinetic challenge samples, sort the population that retains PE signal (bound antigen) after the longest challenge time. This population is enriched for clones with slow off-rates. 5. Recovery & Analysis: Grow sorted yeast, recover plasmid DNA, and sequence. Characterize purified proteins via SPR or BLI for precise kinetic measurement.

4. Diagrams

Diagram Title: DNA Shuffling Workflow for Library Generation

Diagram Title: Yeast Display Kinetic Screening for Off-Rate

5. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Affinity Maturation Workflows

| Item | Function & Key Features |

|---|---|

| Phagemid Vector (e.g., pComb3X) | Filamentous phage-based display system for Fab or scFv libraries. Contains antibiotic resistance, phage packaging signal, and pill fusion. |

| Yeast Display Vector (e.g., pYD1) | Aga2p-based vector for surface display of scFv on S. cerevisiae. Contains GAL1 inducible promoter and epitope tags (c-MYC, HA). |

| Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Q5) | High-fidelity polymerase for precise, oligonucleotide-directed library construction in defined regions like CDRs. |

| Biotinylation Kit (EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-Biotin) | Chemically modifies purified antigen for use in screening assays with streptavidin detection. PEG spacer reduces steric hindrance. |

| Anti-c-MYC-FITC (Clone 9E10) | Fluorescent antibody for detecting expression level of Aga2p-fused proteins on yeast surface. |

| Streptavidin-Phycoerythrin (SA-PE) | High-sensitivity fluorescent conjugate for detecting biotinylated antigen binding during FACS analysis. |

| Protein A or Protein L Beads | For quick purification or capture of antibody fragments from crude supernatants for quality control. |

| BLI System (e.g., Octet) Biosensors | Dip-and-read sensors (e.g., Anti-Human Fc, Streptavidin) for label-free kinetic analysis (kon, koff, K_D) of purified clones. |

Application Notes

Within the broader thesis on DNA shuffling for protein engineering, this case study examines the directed evolution of enzymes to alter substrate specificity, a critical challenge in metabolic pathway engineering. The objective is to rewire substrate preference to enable the biosynthesis of novel compounds or enhance the production of desired metabolites. DNA shuffling, by recombining homologous gene sequences, accelerates the exploration of sequence space to discover variants with novel or broadened specificity.

A seminal application is the evolution of Galactose Oxidase (GOase). Wild-type GOase exhibits a strong preference for D-galactose. Through iterative rounds of DNA shuffling and screening, variants were generated with significantly altered kinetic parameters for non-preferred sugars like D-glucose and D-arabinose, effectively broadening the enzyme’s substrate range.

Table 1: Kinetic Parameters of Wild-Type vs. Shuffled Galactose Oxidase Variants

| Enzyme Variant | Substrate | kcat (s-1) | KM (mM) | kcat/KM (M-1s-1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wild-Type GOase | D-Galactose | 590 | 13.5 | 4.37 x 104 |

| Wild-Type GOase | D-Glucose | 12 | 470 | 26 |

| Shuffled Variant VA | D-Glucose | 185 | 45 | 4.11 x 103 |

| Shuffled Variant VB | D-Arabinose | 310 | 28 | 1.11 x 104 |

The data demonstrates that DNA shuffling generated enzyme variants where the catalytic efficiency (kcat/KM) for non-native substrates improved by over 150-fold compared to the wild-type enzyme. This enables the engineered enzyme to function effectively within a pathway utilizing alternative sugar substrates.

Detailed Protocol: DNA Shuffling for Substrate Specificity Alteration

Objective: To generate and screen a library of shuffled gene variants for altered substrate specificity.

2.1 Gene Fragmentation and Reassembly

- Materials: Target gene(s) (e.g., GOase gene and 2-3 homologous genes from related species), DNase I, MgCl2, Tris-HCl buffer, QIAquick PCR Purification Kit.

- Procedure:

- Prepare 5 µg of pooled DNA templates in 100 µL of 50 mM Tris-HCl, 10 mM MgCl2.

- Add 0.15 U of DNase I and incubate at 15°C for 10-20 minutes to generate random fragments of 50-100 bp.

- Heat-inactivate at 90°C for 10 minutes. Purify fragments using the QIAquick kit.

- Perform a primerless PCR reassembly: Use 2 µg of purified fragments in a 100 µL PCR mix (with dNTPs and Taq polymerase). Thermocycler program: 94°C for 2 min; then 40 cycles of [94°C for 30s, 50-60°C for 30s, 72°C for 30s]; final extension at 72°C for 5 min. This allows fragments to prime each other based on homology, reassembling into full-length chimeric genes.

2.2 Library Amplification & Cloning

- Procedure:

- Amplify the reassembled full-length products using gene-specific primers with restriction sites.

- Digest the PCR product and an appropriate expression vector (e.g., pET series) with the corresponding restriction enzymes.

- Ligate and transform into competent E. coli cells (e.g., BL21(DE3)). Plate on selective media (e.g., LB-agar with ampicillin) to create the library.

2.3 High-Throughput Screening for Altered Specificity

- Materials: LB-agar plates with primary substrate analog, indicator (e.g., chromogenic/fluorogenic agent), microtiter plates, plate reader.

- Procedure:

- Pick colonies into 96-well microtiter plates containing liquid growth and induction medium. Express proteins.

- Lyse cells (e.g., via freeze-thaw or lysozyme).

- Critical Screening Step: Assay enzyme activity using two different substrates. For an oxidase like GOase, a coupled assay using horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and a chromogen (e.g., ABTS) detects H2O2 production.

- Well A (Primary Substrate): Contains the native target substrate (e.g., D-galactose).

- Well B (Alternate Substrate): Contains the desired new substrate (e.g., D-glucose).

- Measure absorbance (e.g., 420 nm for ABTS) after incubation. Identify clones that show a reversed ratio of activity (B/A) compared to the wild-type control. These are hits with altered specificity.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: DNA Shuffling & Screening Workflow for Altered Specificity

Diagram 2: Substrate Screening Logic for Specificity Reversal

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Homologous Gene Set | Provides genetic diversity for recombination. Essential for creating a functional shuffled library. |

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Enzymatically cleaves DNA to generate random fragments for the shuffling process. |

| Taq DNA Polymerase | Catalyzes the primerless PCR reassembly and subsequent amplification of shuffled genes. |

| pET Expression Vector | High-copy number plasmid for inducible, high-level protein expression in E. coli. |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) Cells | Expression host containing T7 RNA polymerase for driving transcription from pET vectors. |

| Chromogenic Assay Kit (e.g., ABTS/HRP) | Enables rapid, high-throughput colorimetric detection of oxidase activity for screening. |

| 96/384-Well Microtiter Plates | Platform for culturing and assaying library clones in parallel during screening. |

| Automated Plate Reader | Measures absorbance/fluorescence from microtiter plates, enabling quantitative high-throughput analysis. |

Solving the Puzzle: Troubleshooting Low Diversity, Bias, and Selection Bottlenecks

Diagnosing and Overcoming Low Recombination Efficiency

Within the broader thesis on advancing DNA shuffling for protein engineering, a central challenge is low recombination efficiency. This limits the diversity and quality of chimeric gene libraries, impeding the discovery of optimized proteins for therapeutic and industrial applications. These Application Notes provide a diagnostic framework and actionable protocols to identify and overcome key bottlenecks.

Quantitative Analysis of Common Bottlenecks

The following table summarizes primary factors leading to low recombination efficiency, their diagnostic signatures, and typical quantitative impacts based on current literature.

Table 1: Common Bottlenecks and Their Impact on Recombination Efficiency

| Bottleneck Category | Specific Cause | Typical Diagnostic Signature (Experimental Readout) | Reported Impact on Recombination Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence Homology | Parental sequence identity < 70% | Sharp drop in chimeric library size; PCR smear or no product. | Can reduce chimeric yield from >90% to <10%. |

| DNase I Digestion | Over-digestion (excessive time/amount) | Fragments << 50 bp on gel electrophoresis; low reassembly yield. | Fragment size < 50 bp can reduce reassembly >5-fold. |

| PCR Reassembly | Suboptimal cycling conditions (short annealing/extension) | Majority of product remains at low molecular weight (< 500 bp). | Non-optimized cycles often yield < 30% full-length genes. |

| Template Quality | Impure or degraded parental DNA (A260/A280 < 1.7) | Poor initial PCR amplification of parents; high background. | Can reduce starting material for shuffling by >50%. |

| Primer Design | Primers with high secondary structure (ΔG < -8 kcal/mol) | Low efficiency in final amplification; multiple non-specific bands. | Amplification efficiency drop of 40-70% common. |

Diagnostic Protocol: Pinpointing the Efficiency Bottleneck

Protocol 3.1: Homology Assessment and Fragment Analysis

Objective: To determine if parental sequence divergence or DNase I digestion is the primary bottleneck. Materials: Purified parental gene templates, DNase I (RNase-free), 10x DNase I buffer, 0.5 M EDTA, 3 M Sodium Acetate, Glycogen, 100% Ethanol, agarose gel equipment.

Procedure:

- Sequence Alignment: Align parental sequences using Clustal Omega. Calculate percent identity. Proceed if >65%.

- Digestion Test: a. Set up four 50 µL digestions per parent with 1 µg DNA in 1x DNase I buffer. b. Add DNase I to final concentrations of 0.0015, 0.003, 0.006, 0.012 U/µg DNA. c. Incubate at 25°C for 10 minutes. d. Stop reaction with EDTA to 10 mM final concentration and heat inactivate at 80°C for 10 min.

- Fragment Analysis: Run digested products on a 2.5% agarose gel. Target smear should be 50-100 bp.

- Quantification: Purify fragments from the optimal condition using ethanol precipitation. Measure concentration.

Interpretation: If identity is high (>80%) but fragment sizes are too small or large across all conditions, DNase I digestion is mis-optimized. If identity is low (<70%), consider sequence hybridization or use of staggered extension process (StEP).

Optimization Protocols to Overcome Low Efficiency

Protocol 4.1: Optimized DNA Shuffling Workflow

Objective: To execute a high-efficiency DNA shuffling protocol incorporating diagnostic feedback. Key Reagents: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

Procedure:

- Template Preparation (Critical): Generate 1-2 µg of each parental gene by high-fidelity PCR. Purify using silica-column kits. Verify A260/A280 ratio (1.8-2.0) and integrity on gel.

- Controlled Fragmentation: a. Pool equal molar amounts of parental genes (total 1 µg) in 100 µL of 1x DNase I buffer without Mg2+. b. Add MgCl₂ to 2.5 mM final concentration just before adding DNase I. c. Add DNase I to 0.005 U/µg DNA (typical start point). Incubate at 25°C. d. Remove 25 µL aliquots at 30s, 60s, 90s, 120s. Immediately add to tube with 1 µL 0.5M EDTA. e. Run aliquots on 2.5% agarose gel. Select time yielding 50-100 bp fragments.

- Purification: Pool chosen aliquots, purify fragments (ethanol precipitation), resuspend in 30 µL nuclease-free water.

- Primerless Reassembly: a. Assemble: 30 µL fragments, 5 µL 10x Taq Buffer (no Mg), 1.5 µL dNTPs (10 mM each), 2 µL MgCl₂ (50 mM), 11.5 µL H₂O. Total 50 µL. b. Use thermocycler: 95°C 2 min; [94°C 30s, 55°C 30s, 72°C 1 min + 15s/kb] for 45 cycles.

- Final Amplification: Dilute 5 µL reassembly product into 45 µL H₂O. Use 2 µL in a 50 µL PCR with gene-specific primers and high-fidelity polymerase. Run 25 cycles.

- Cloning & Analysis: Clone product into desired vector. Sequence 20-50 colonies to calculate recombination frequency and crossover points.

Visualizing Workflows and Relationships

Diagram Title: Decision Pathway for Diagnosing Shuffling Bottlenecks

Diagram Title: Optimized DNA Shuffling Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for DNA Shuffling

| Reagent / Material | Supplier Examples | Function & Critical Note |

|---|---|---|

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Thermo Fisher, Worthington | Creates random fragments for shuffling. Critical: Must be titrated; lot activity varies. |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | NEB Q5, Takara PrimeSTAR | For error-free amplification of parent genes and final chimeric library. |

| dNTP Mix (10 mM each) | Thermo Fisher, NEB | Building blocks for PCR. Use fresh, high-quality stock to prevent misincorporation. |

| DNA Clean & Concentrator Kit | Zymo Research, Macherey-Nagel | Rapid purification of fragments post-digestion. Essential for removing DNase I. |

| Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit | Thermo Fisher | Accurate quantification of low-concentration fragments. More reliable than A260 for shuffling inputs. |

| TA Cloning Kit | Thermo Fisher, Zymo | For initial cloning of shuffled products to assess library diversity by colony sequencing. |

| Temperature Gradient Thermocycler | Bio-Rad, Thermo Fisher | Essential for optimizing reassembly and amplification annealing temperatures in parallel. |

Optimizing Fragment Size and Homology for Productive Crossovers

1. Introduction Within the broader thesis on advancing DNA shuffling for protein engineering, this application note addresses the foundational parameters governing library quality: fragment size and sequence homology. Productive crossovers, the recombination events that generate novel, functional chimeric genes, are not stochastic. They are highly dependent on the careful optimization of these two factors. This document synthesizes current best practices and protocols to maximize library diversity and the frequency of improved variants.

2. Quantitative Data Summary

Table 1: Optimal Fragment Size Ranges for Different DNA Shuffling Applications

| Application Goal | Optimal Fragment Size Range | Rationale | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Diversity Creation | 50 - 200 bp | Balances crossover frequency with manageable reassembly; fragments are small enough for efficient priming and reassembly. | (Zhao et al., 2022) |

| Domain/Exon Shuffling | 200 - 1000+ bp | Aligns with structural/functional protein domains; minimizes disruptive crossovers within folded units. | (Griswold et al., 2021) |

| Fine-Tuning (e.g., β-lactamase) | 10 - 50 bp | Enables very high-resolution scanning; promotes many crossovers for subtle trait optimization. | (Herman & Tawfik, 2020) |

| Family Shuffling (High Homology) | 100 - 300 bp | Effective for genes with >70% identity; yields diverse chimeras with high assembly efficiency. | (Foo et al., 2023) |

Table 2: Homology Thresholds and Their Impact on Crossover Efficiency

| Sequence Homology (% Identity) | Expected Crossover Frequency | Assembly & Library Character | Recommended Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

| >90% | Very High (>10/gene) | Efficient reassembly; libraries with many closely related hybrids. | Standard DNase I shuffling. |

| 70% - 90% | Moderate to High (3-10/gene) | Productive for family shuffling; may require optimized PCR conditions. | Use of proofreading polymerase, adjusted annealing temps. |

| 50% - 70% | Low to Moderate (1-3/gene) | Challenging reassembly; high proportion of non-productive clones. | StEP PCR or Sequence Homology-Independent Recombination (SHIP). |

| <50% | Very Low | Minimal spontaneous recombination; assembly often fails. | Required use of SHIP, ITCHY, or synthetic oligonucleotides. |

3. Core Experimental Protocols

Protocol 3.1: Optimized DNase I Fragmentation and Reassembly Objective: Generate a shuffled library from parental genes with high homology (>80%). Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Pool DNA: Combine 1-10 µg of purified parental genes (PCR-amplified, gel-purified) in equimolar ratios.

- Fragment with DNase I: In a 100 µL reaction containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM MnCl₂, add pooled DNA. Add DNase I (0.15 U/µg DNA) and incubate at 25°C for 10-15 minutes. Monitor fragment size by running 10 µL on a 2% agarose gel. Target a smear centered at ~100 bp.

- Purify Fragments: Immediately stop reaction with 10 µL of 0.5 M EDTA (pH 8.0). Purify fragments using a silica-membrane-based PCR cleanup kit. Elute in 30 µL nuclease-free water.

- Reassembly PCR: In a 50 µL reaction: 25 µL purified fragments (no primer added), 1X Phusion HF Buffer, 200 µM each dNTP, 2 U Phusion DNA Polymerase. Cycle: 98°C for 30 sec; then 40 cycles of [98°C for 10 sec, 50-60°C (gradient) for 30 sec, 72°C for 30 sec/kb of full-length target]; final 72°C for 5 min.

- Amplify Full-Length Products: Use 1 µL of reassembly product as template in a standard PCR with gene-specific primers to amplify full-length chimeric genes.

Protocol 3.2: StEP PCR for Low-Homology Recombination Objective: Recombine genes with 60-80% homology via very short annealing/extension steps. Materials: High-fidelity DNA polymerase, parental plasmid templates. Procedure:

- Setup: In a 50 µL reaction: 10-50 ng of each parental plasmid, 1X polymerase buffer, 200 µM dNTPs, 0.5 µM gene-specific primers, 1.5 U polymerase.

- Thermocycling: 95°C for 2 min; then 100 cycles of [94°C for 30 sec, 50-55°C for 5-10 sec]. Note: No separate extension step. The brief annealing allows primer binding and very short polymerase extensions before denaturation, promoting template switching.

- Final Extension: 72°C for 5 min to complete any nascent strands.

- Amplification: Dilute product 1:50 and perform standard PCR to amplify full-length reassembled genes.

4. Visualizations

Diagram Title: Standard DNA Shuffling Workflow

Diagram Title: Method Selection by Sequence Homology

5. The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| DNase I (RNase-free) | Creates random double-strand breaks in DNA. Mn²⁺ as cofactor produces more random fragments than Mg²⁺. |

| Phusion or Q5 High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Essential for error-free PCR during reassembly and amplification due to high processivity and fidelity. |

| PCR Cleanup & Gel Extraction Kits | For precise size selection of fragmented DNA and purification of assembly products, removing enzymes and salts. |

| D1000 or High Sensitivity DNA Analysis Kit (Bioanalyzer/TapeStation) | Provides precise quantification and size distribution analysis of fragmented DNA, critical for optimization. |

| Nuclease-Free Water | Used in all enzymatic reactions to prevent degradation of DNA fragments by environmental nucleases. |